Commission, April 5, 2013, No M.6789

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Judgment

BERTELSMANN/ PEARSON/ PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE

Dear Sir/Madam,

Subject: Case No COMP/M.6789 - BERTELSMANN/ PEARSON/ PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/2004

1. On 26 February 2013, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which the undertakings Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA ("Bertelsmann") of Germany and Pearson Plc ("Pearson") of the UK acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation joint control of the newly created joint venture Penguin Random House (the "JV") by way of purchase of shares.2 Bertelsmann and Pearson are designated hereinafter as the "parties".

I. THE PARTIES AND THE JV

2. Bertelsmann is an international media company whose core divisions encompass television and television production (RTL Group), trade publishing (Random House), magazine publishing (Gruner + Jahr), music rights management (BMG) and services (Arvato) in some 50 countries.

3. Pearson is active in publishing educational materials (Pearson), business information (Financial Times) and trade publishing (Penguin; which includes Dorling Kindersley Books and Rough Guides).

4. Penguin Random House will contain all of the English language trade publishing divisions of Bertelsmann's Random House division in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, India and South Africa as well as the Spanish language trade publishing divisions of Bertelsmann's Random House division in Spain and Latin America, but will exclude Bertelsmann's German language trade publishing division Verlagsgruppe Random House. It will also contain all of Penguin's business and assets including its US, European, Australasian and Indian trade publishing divisions, its trade publishing company in China and its 45% share in a Brazilian Portuguese language publishing house. According to the initial strategic business plan for the years 2013-2016, the joint venture is expected to have a turnover (net external sales) of USD […] in 2014.

II. THE CONCENTRATION

5. Joint control. The JV will comprise a Delaware entity ("USCO") that will operate directly and through subsidiaries in the United States, and an existing UK corporation or such other entity as will be agreed by Bertelsmann and Pearson ("ROWCO") (together "the Ventures"). The ROWCO will operate directly and through subsidiaries in the EU and other countries outside the United States.

6. The USCO and ROWCO will each:

a) have a board of representatives ("Board"), Chief Executive Officer ("CEO"), Chief Operating Officer ("COO"), Chief Financial Officer ("CFO"), and senior management; and

b) be owned, directly or indirectly, by Bertelsmann and Pearson, with shareholdings of respectively 53% and 47%.

7. According to the "Framework Agreement" between Bertelsmann and Pearson, which sets out the governance and voting arrangements for the Ventures, Bertelsmann will have the power to appoint the majority of the members of the Board with voting rights. While most decisions relating to the Ventures require only a simple majority vote of the Board, certain "Reserved Matters" require the approval of Pearson as minority shareholder.

8. The Framework Agreement confers a veto right upon Pearson for decisions regarding:

a) […]; and b) […]

9. Pearson will also have the right, […].

10. Finally, the Framework Agreement affords Pearson […]: a) […];

b) […];

c) […];

d) […];

e) […];

f) […];

11. According to the Commission's Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice, a minority shareholder will be deemed to enjoy joint control over a JV if it is able to block the adoption of strategic decisions by the JV without having the power, on its own, to impose such decisions.3 Veto rights which confer joint control typically include decisions on issues such as the budget, the business plan, major investments or the appointment of senior management.4 By contrast, veto rights that are normally accorded to minority shareholders in order to protect their financial interests as investors are insufficient to establish joint control.5

12. On the one hand, the following rights afforded to Pearson under the Framework Agreement are in themselves insufficient to lead to Pearson acquiring joint control over the JV:

a) Pearson's veto rights in relation to […]. During the period between 2009 and 2012, Bertelsmann […]. During that same period, Pearson […]. It therefore seems unlikely that these thresholds will be attained for many strategic decisions concerning the JV and that they are rather designed to protect Pearson's financial interests as a minority shareholder

b) Pearson's right […].

c) Pearson's rights in relation to […].

13. In addition, while in the Bertelsmann/KKR/JV,6 the minority shareholder, Bertelsmann, was an industrial shareholder that contributed its business to a joint venture with a majority shareholder, KKR, that was a mere financial investor, in this case, both Bertelsmann and Pearson will be industrial shareholders.

14. On the other hand, when assessing Pearson's rights in the JV as a whole, and in particular in view of […], Pearson's influence over the JV will, on balance, lead to Pearson acquiring joint control over the JV:

a) […];

b) […]; and

c) […].

15. Consequently, it can be concluded that Bertelsmann and Pearson will exercise joint control over the newly created entity.

16. Full function joint venture. The JV qualifies as a full-function joint venture as it will operate on the market autonomously from its parent companies, performing all the functions of undertakings normally active on the same market. In more detail:

a) The JV will sell trade books on the market and not depend on sales to its parent companies.7

b) The JV will have its own management.8

c) The JV will have a dedicated team of employees.9

d) The JV will have adequate funding to perform its activities.10

e) The JV will have access to sufficient assets and infrastructure to allow it to operate on a lasting basis.11

f) The JV will be formed for an indefinite period.12

17. For the above reasons, the proposed transaction leads to the creation of a joint venture performing on a lasting basis all the functions of an autonomous economic entity within the meaning of Article 3(4) of the Merger Regulation.

18. The transaction constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

III. UNION DIMENSION

19. The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate worldwide turnover for the year 2011 of more than EUR 5 000 million13 (Bertelsmann: EUR 15 253 million,Pearson: EUR 6 754 million). In the same year, the parties each achieved more than EUR 250 million EU-wide turnover (Bertelsmann: […], Pearson: EUR […]), and did not achieve two thirds of their EU turnover in one and the same single EU Member State.

20. The notified operation therefore has a Union dimension within the meaning of Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

IV. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

1. Introduction

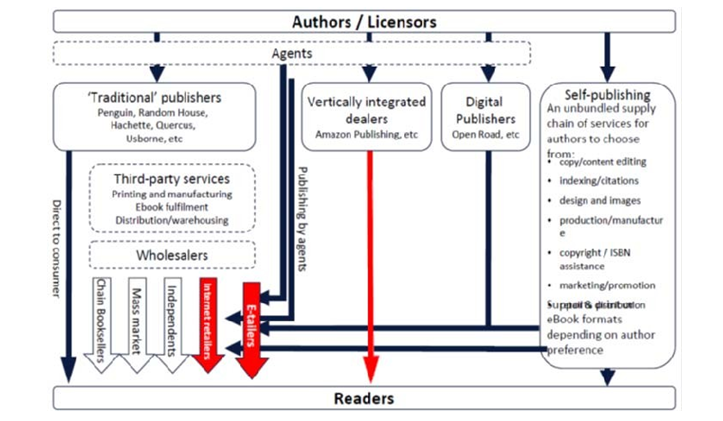

21. The trade book publishing value chain for any given title comprises the acquisition of publishing rights, editorial input and design, production of the print and/or e-book version of the title and its sale to dealers and/or consumers as well as marketing and promotion activities. Some publishers also engage in book production and distribution activities for third party publishers.

22. In the past, publishers acquired, edited and marketed authors' works almost exclusively. More recently, to a large extent due to technical development, vertical integration can be observed on several levels of the value chain: authors started to engage in self- publishing while both literary agents and retailers such as Amazon started to provide publishing services and thereby compete with traditional publishers.

Table 1: Schematic overview of the trade publishing industry today

Source: Parties

23. Random House and Penguin are both active in the upstream acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles, as well as on the downstream sale of English books to dealers. The Commission therefore assessed the likelihood of horizontal non-coordinated and coordinated effects on these markets taking also into account the vertical link between acquisition of publishing rights for English language books and sale of those books to dealers (sections 2 and 3). In addition, the Commission assessed the proposed transaction's impact on third party book distribution, in which both Random House and Penguin are present (section 4). Finally, the Commission assessed the proposed transaction's impact given the vertical relationship between Bertelsmann's activities in book production (through its Arvato division and BePrinters) and the JV's activities in the sale of English language books to dealers (section 5).

2. Acquisition of Publishing Rights and Supply of Services to Authors

2.1. Product market definition

24. The JV will be active upstream in the acquisition of authors' rights and offer of services, such as the editing of manuscripts, to authors.

2.1.1. View of the parties

25. The parties submit that the relevant upstream market encompasses the acquisition of authors' rights for the publishing of English language books without further differentiation based on different categories of books (for example general literature, children's books, and guides and manual); the formats (hardback versus paperback) or the original language of the work (whether the title was originally written in English or a foreign language).

26. According to the parties, there is no reason to segment the upstream market by book categories, since the vast majority of works involve the licensing of authors' rights in a similar manner. Furthermore, from a supply perspective it would be easy for publishers to expand into the various book categories if they are not yet present in those.

27. The parties further argue that publishers typically acquire rights to publish a title in all formats including as a hardback and a paperback and that unlike in the French publishing market, English language paperback publishing rights are not sold on to other publishers for exploitation, but exploited by the same publisher who publishes the hardback.

28. As regards the publishing rights for a title originally written in a foreign language, the parties explain that these are generally the same as publishing rights for an original English title and that they are acquired in the same way as publishing rights for titles written in English language.

29. Moreover, according to the parties, the acquisition of publishing rights for English language print books, e-books and audiobooks all belong to the same product market, since publishers typically acquire them together.

30. In addition, the parties explain that the acquisition of publishing rights in bestsellers does not constitute a separate product market, as publishers cannot predict with certainty whether a title will develop in a bestseller or not, when they acquire the respective rights. Moreover, there would not be an industry-wide definition of a bestseller in any event.

31. They further submit that on the upstream market, book publishers would provide a number of services to authors such as the payment of advances, editing, pre- publication legal advice, proofreading and design. For this reason, the parties consider the acquisition of publishing rights from authors to be closely analogous to its equivalent market in the context of music publishing, which the Commission has previously defined as a market for the provision of publishing services to authors.14

2.1.2. Commission's assessment

32. In its decision in the Lagardère/Natexis/VUP case ("Lagardère") concerning the French language publishing sector,15 the Commission defined separate product markets for the acquisition of publishing rights according to the original language of the work, that is to say (i) French-language publishing rights for an original work in French, and (ii) French-language publishing rights for an original work in a foreign language. In that case, the Commission further found that the categories of books that were affected by publishing rights were all individual works, since it rarely happened that rights were acquired for collective works. Instead, in the case of collective works, typically, a fee would be paid for the individual contributions to the overall work. The Commission therefore considered that only general literature titles, children's books, strip cartoon albums and academic and professional works constituted individual works for which publishing rights were acquired. It found that the markets for French-language publishing rights had to be subdivided according to the categories of books in question. In addition, the Commission defined separate secondary markets for French-language publishing rights for publication in (i) pocket format and (ii) book clubs.

33. While the market investigation validated several of the arguments of the parties, it also showed that several of the Commission's findings in Lagardère are also applicable to the English language publishing sector.

Services typically provided by publishers

34. The market investigation conducted for the purpose of the present transaction confirmed that publishers typically offer the following services to authors: editorial service, physical book production, e-book production (digitisation), audio-book production, sales, design (jacket and book interior), rights sales, and distribution.16 These services are provided by using the publishers' own capacities, or smaller publishers would source some of these services (for example distribution) from third parties.

Distinction between publishing rights based on the original language of the work

35. The results of the market investigation were mixed as regards a distinction between the acquisition of publishing rights for a title in English language and a title in another language to be translated into, and published in English language. While several publishers and literary agents indicated that the respective contracts do not differ, others indicated that there are differences with respect to (i) the person/entity from whom these rights are acquired (author/another publishing house/etc.), (ii) the scope of publishing rights (coverage of print version, e-book version, hardback, paperback), (iii) the contractual duration of publishing rights, and (iv) the level of author advances and royalties.17 In this context, it was pointed out that translation rights are often acquired from other publishers and not directly from the author.Advances and royalties would tend to be lower for a work that firstly needs to be translated into English language, among other reasons due to the cost of translation. Furthermore, the respective rights might be acquired for a limited period in time only.

Distinction between publishing rights for English language titles according to the category of books

36.The market investigation provided mixed results as to whether the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles varies for the different categories of books, as defined in Lagardère. The majority of publishers who replied in the market investigation indicated that the typical publishing contracts do not vary significantly for (i) general literature, (ii) children's books, (iii); guides and manuals, (iv) strip cartoon albums, (v) art books and (vi) academic and professional books.18 However, the majority of literary agents who participated in the market investigation explained that publishing contracts in the above-mentioned categories differ from each other, for example as regards the level of royalties.19

Distinction of separate secondary markets for English language publishing rights for the publication of a title as paperback or via a book club

37. The market investigation confirmed that publishers typically acquire the rights to publish an English language title as hardback and paperback.20 Furthermore, the vast majority of respondents confirmed that the same publishers publish the hardback and paperback versions of a title.21

38. Moreover it was confirmed that the sale of a title via a book club does not require any specific publishing rights in the UK and Ireland.22

Distinction between the acquisition of publishing rights for print books, for e-books and audiobooks

39. In its market investigation, the Commission further tested whether the acquisition publishing rights for print books, e-books and audiobooks belongs to the same relevant product market. In this context, it found that today the vast majority of publishers acquire publishing rights for the e-book version of a title together with the publishing rights for the print version in over 90% of the cases.23 However, several respondents indicated that contracts that were concluded prior to the market launch of e-books may not necessarily cover publishing rights for e-books.

40. As regards publishing rights for audiobooks, the results of the market investigation revealed that these are less frequently acquired together with the publishing rights for the print title than publishing rights for e-books. Answers varied from 25% to 80% of the cases.24

Publishing rights for English language potentially bestselling titles

41. The Commission found that the level of advances paid to authors vary to an outstanding degree. While a […] number of authors do not receive any advances at all for their works, a small fraction of top selling authors may receive advances which are higher than GBP one million. In the period from 2009 to 2011, Penguin and Random House paid advances of GBP 500,000 or more only for respectively [0- 5]% and [0-5]% of the titles for which they acquired publishing rights.

42. Taking into account the difference in the level of advances paid for a title as described above, the Commission considered whether the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles written by well-reputed authors (which are more likely to be paid higher advances) could constitute a separate product market or a specific market segment with particular competitive dynamics. For this purpose the Commission defined an author as well-reputed if the author has written a title that was recorded in the weekly top 100 bestselling titles according to the Nielsen weekly 5000 database in any of the five years preceding the contract for new title(s), and/or if the author can be characterized as a celebrity in an area different from book publishing.

43. The level of advances that the parties paid in 2011 for titles written by well-reputed authors was […] higher than the level of advances paid for titles written by any type of author. While the median advance paid by Random House and Penguin in the years 2009 to 2011 was GBP […] and GBP […] respectively,25 in 2011, the median advance for titles by well-reputed authors amounted to GBP […] in the case of Random House and GBP […] in the case of Penguin.26 This difference in median advances suggests that titles written by well-reputed authors could belong to a possible separate segment of the market.

44. However, the results of the market investigation did not allow the Commission to define the acquisition of publishing rights by well-reputed authors as a separate market.27

45. Nevertheless, taking into account that the competitive dynamics in the segment of the acquisition of authors' rights for a consideration of more than GBP 500,000 may be different from the overall market for the acquisition of publishing rights, the Commission treats the acquisition of authors' rights for a consideration above GBP 500,000 as a possible separate market segment for the purpose of the competitive assessment.

Conclusion

46. The results of the market investigation were mixed as to the question whether the acquisition of English-language publishing rights for titles originally written in English and those originally written in a foreign language belong to the same product market. Furthermore, the results of the market investigation were mixed as to the question whether the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles needs to be further divided according to the category of titles concerned ((i) general literature; (ii) children's books; (iii); guides and manuals; (iv) strip comics, (v) art books and (vi) academic and professional books. While the market investigation revealed strong indications that publishing rights for English language print books and e-books belong to the same product market, its results were mixed as to the question whether the acquisition of publishing rights for audiobooks belong as well to that product market. Furthermore, the market investigation revealed strong indications that the acquisition of authors' rights to publish an English language title as paperback or via a book club does not constitute separate secondary rights markets. Finally, the market investigation did not allow the Commission to conclude that the acquisition of publishing rights for titles written by well-reputed authors constitutes a separate product market.

47. For the purpose of the present decision, the Commission considers that the acquisition of authors' rights to publish an English language title as paperback or via a book club does not constitute separate secondary rights markets. Apart from this, the exact product market definition as regards the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles can be left open, given that the proposed transaction does not raise competition concerns under any possible market delineation.

2.2. Geographic market definition

2.2.1. View of the parties

48. The parties submit that the relevant geographic market for the acquisition of primary publishing rights is at least EEA wide and possibly worldwide. They add that the Commission can leave the definition open as, regardless of the geographic scope of the market, the transaction will not lead to a significant impediment to effective competition.

49. The parties explain that publishers active in the UK and Ireland will typically acquire exclusive English language publishing rights for the UK and Ireland, as well as, to the extent possible, the EEA and the Commonwealth.28 They underline that publishers in the UK and Ireland will invariably seek to obtain exclusive rights for the EEA, which are particularly important because of the implications of the exhaustion principle.29 However, in instances where exclusive rights for the EEA may not be made available, publishers would opt to acquire non-exclusive rights. The parties further submit that publishers in the UK and Ireland sometimes try to acquire "World English Language" rights, including US and Canadian rights, if they believe that they will be able to exploit these either directly or through sub-licensing arrangements with local publishers.

50. In addition, the parties submit that they face essentially the same competitive dynamics in all countries where they are active. They face competition for the acquisition of publishing rights from at least four other large international publishers, Hachette, Harper Collins, Pan MacMillan and Simon & Schuster – as well as a large number of medium sized and smaller publishers. This similarity of competitive conditions globally would be reflected in the fact that compared to the EEA, Penguin and Random House's market share is not […] higher in other major English language countries in which they operate outside the EEA. To substantiate this statement the parties provide their market shares on the respective downstream markets for the sale of English language books to dealers as a proxy for their position on the upstream markets for the acquisition of publishing rights in those countries, as illustrated by table 2 below.

Table 2: Combined market share of physical books by value in major English language countries – 2012

Jurisdiction | Combined market share |

EEA | [20-30]% |

Australia | [20-30]% |

Canada | [30-40]% |

New Zealand | [20-30]% |

South Africa | [20-30]% |

United States | [10-20]% |

2.2.2. Commission's assessment

51. In Lagardère, the Commission found the relevant geographic market for the acquisition of French-language publishing rights to be worldwide.30

52. The market investigation conducted for the purpose of the present transaction confirmed that likewise the relevant geographic market for the acquisition of English-language publishing rights is at least EEA wide, if not worldwide. Furthermore, the geographic scope of publishing rights does not vary for whether for print books, e-books or audiobooks or according to the categories of books in question.

53. The majority of publishers who participated in the Commission's market investigation indicated that they aim at acquiring publishing rights for English language print books which are worldwide in scope. A smaller number of publishers indicated that they aim at acquiring publishing rights for English language titles for a territory that covers the EEA and the rest of the world without the United States and Canada. In addition, several publishers explained that they do not always succeed in obtaining the geographic scope of the publishing rights that they aim for, but sometimes have to settle for a narrower geographic scope, for example exclusive rights for the UK and Ireland and non-exclusive rights for the rest of the EEA or world.31 This is true for publishers of (i) general literature, (ii) children's books, (iii) guides and manuals, and (iv) reference works.32

54. As regards publishing rights for e-books, the majority of publishers who participated in the Commission's market investigation confirmed that they aim at acquiring publishing rights which are either worldwide in scope or cover at least a territory comprising the EEA and the rest of the world without the United States and Canada.33 This is true for publishers of e-book titles falling into the following categories: (i) general literature, (ii) children's books, (iii) guides and manuals, and (iv) reference works, (v) strip cartoon albums, (vi) art books, and (vii) academic and professional books.

55. As regards publishing rights for audiobooks, all publishers who participated in the Commission's market investigation indicated that they aim at acquiring publishing rights which are either worldwide in scope or cover at least a territory comprising the EEA and the rest of the world without the United States and Canada.34 Overall, the responses by publishers do not vary between general literature audiobooks and children's audiobooks.

Conclusion

56. For the purposes of the present decision, the exact geographic market definition as regards the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles can be left open since the proposed transaction will not raise competition concerns under any possible geographic market delineation.

2.3. Competitive assessment

2.3.1. Non-coordinated effects

Introduction

57. In this section, the Commission assesses whether the proposed transaction will cause horizontal non-coordinated effects on the upstream market for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language books and its various segments, which possibly constitute separate product markets. The Commission considered the following possible separate markets for (i) the various book categories (that is to say general literature, children's books, guides and manuals, strip cartoon albums, art books and academic and professional books), (ii) the different book formats (that is to say print book, e-book and audio-book), and (iii) works originally written in English and works to be translated into English. Furthermore, within the competitive assessment, the Commission analyzed whether the proposed transaction will lead to particularly pronounced effects as regards the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles in a high price segment of the market. The Commission carries out the competitive assessment of non-coordinated effects at EEA-wide and at worldwide levels.

58. In particular, the Commission assessed whether the merged entity would have market power such as to be able to unilaterally raise the level of remuneration (advances and royalties) paid to authors on the upstream market(s) or specific segments of the upstream market(s) and thereby foreclose competitors from accessing publishing rights for specific categories of titles as essential input for their downstream sales. If in the long run such foreclosure leads to the exit of other publishers from the downstream market and thereby reduces competition on this market, this might lead to consumer harm in the form of increased prices or reduced choice and innovation.

Views of the parties

59. According to the parties, the transaction will not significantly impede effective competition in respect of the acquisition of publishing rights, for the following reasons:

60. First, they submit that as demonstrated in table 3 below, the merged entity's market shares in the upstream market for the acquisition of publishing rights would be modest. They propose to use the market shares in the downstream market for the sale of English language print books as a proxy for assessing their position in the acquisition of publishing rights. The parties submit that the method used in Lagardère to calculate market shares in the upstream market for the acquisition of publishing rights by using advances paid to authors for bestsellers35 is not appropriate.

Table 3: Publishing rights for English language works (based on sales of print books to dealers as a proxy – UK and Ireland, by value, 2009-2012)

| 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | ||||

Companies | Value (in Mio EUR) | Market Share | Value (in Mio EUR) | Market Share | Value (in Mio EUR) | Market Share | Value (in Mio EUR) | Market Share |

Random House | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [10-20]% |

Penguin | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [5-10]% |

Combined | […] | [20-30]% | […] | [20-30]% | […] | [20-30]% | […] | [20-30]% |

[Pearson]* | […] | [0-5]% | […] | [0-5]% | […] | [0-5]% | […] | [0-5]% |

Hachette | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [10-20]% | […] | [10-20]% |

HarperCollins | […] | [5-10]% | […] | [5-10]% | […] | [5-10]% | […] | [5-10]% |

Pan Macmillan | […] | [0-5]% | […] | [0-5]% | […] | [5-10]% | […] | [0-5]% |

Others | […] | [40-50]% | […] | [40-50]% | […] | [40-50]% | […] | [40-50]% |

TOTAL | […] | 100% | […] | 100% | […] | 100% | […] | 100% |

Sources: Nielsen bookscan data;

*As parent of Penguin Random House, Pearson will continue its educational business, including very limited trade book publishing.

61. Post-transaction, Penguin Random House will have a share of [20-30]% by value in the market for the acquisition of all English language publishing rights. Even if this were further sub-divided by category into general literature and children’s books, Penguin Random House would have a share of only [30-40]% and [20-30]% respectively for English language publishing rights in 2011.

62. Second, the parties submit that Random House and Penguin are not each other’s closest competitors in relation to the acquisition of publishing rights. According to them, it follows from the use of the same market shares that publishers have in relation to the sale of books that there is no segment of the market where they do not face strong competition from the four other large international publishers, Hachette, HarperCollins, Pan MacMillan and Simon & Schuster, as well as from medium-sized and smaller publishers.

63. Third, according to the parties, authors choose a publisher based on a range of considerations, not just advances. Key factors would include the identity of particular editors, the marketing plan, the publisher’s perceived experience with similar titles, the culture of the publisher and other intangibles. They explain that the acquisition of publishing rights from both debut authors and established authors is generally conducted through a bidding process - managed by literary agents on behalf of authors, whether through a formal auction or one or more bilateral negotiations.

64.In this context the parties submit that in 2011, more than [80-90]% of publishing rights were purchased for less than GBP 50,000, an affordable amount even for smaller publishers. They explain that a significant proportion of the market is accounted for by medium-sized competitors such as Bloomsbury, Quercus, Canongate, Faber and Faber, Profile, Usborne, Walker, Egmont and Scholastic who will also continue to exert a competitive constraint in the market because they are frequent competitors on all bids, and are often willing to bid up to GBP 500,000 (EUR 616,622) for an advance manuscript. Medium-sized publishers may also bid in excess of GBP 500,000 for instance, where they place a higher value on a book matching their expertise or if they believe in a book more than other publishers and are therefore willing to pay a higher advance. Smaller publishers are also prepared to bid in excess of GBP 100,000 (EUR 123,000).

65. In addition, the parties submit that even if the scale of the advance were to be the prime motivator behind an author selecting a particular publisher, there are many publishers that could easily afford the necessary expenditure. For example, all of Hachette, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster and Pan Macmillan, and AudioGo in the context of audiobooks, will continue to have similar financial capacity as Penguin Random House post-transaction. All of these suppliers secured rights to established brand authors in fiction, as well as more expensive celebrity autobiography titles.

66. Fourth, the parties explain that bidding dynamics will be unchanged by the transaction. According to them, there are several powerful agents active in the English language trade publishing industry which represents important players in the publishing value chain. These agents are well resourced, in many cases active across several industries in addition to books (for example film, theatre), represent a number of established authors, and their reputations, built-up over many years, mean that the titles they offer to publishing houses are likely to be seriously considered for publication.

67. According to the parties, the transaction will not affect the negotiating position of the literary agents vis-à-vis the parties especially as there will remain several other competitors that would have similar financial capacity to Penguin Random House (in particular, larger international competitors such as Hachette, Harper Collins, Pan Macmillan and Simon & Schuster).

68. Fifth, the growth of self-publishing would have allowed authors to bypass the market and increased authors’ bargaining position, therefore placing additional constraint on publishers.

69. According to the parties, the market for the acquisition of publishing rights would be currently undergoing significant change as a result of the explosion in popularity of e- books and the corresponding emergence of self-publishing companies that offer authors an alternative route to market. Self-publishing providers generally offer core publishing services (for example distribution via online sales platforms) for free. In addition, many also offer add-on services that approximate the packages offered by the traditional publishing houses for a fee (for example editing, cover design, promotional materials etc.). Furthermore, the option of print-on-demand books, where physical books are only manufactured when they are ordered, would have considerably reduced the cost and risk involved in self-publishing and has opened up a low cost and low risk route to consumers for authors.

70. Finally, according to the parties, barriers to entry would be low and there would be significant potential for new market entry (for example as a provider of self-publishing services, or by non-English language publishers).

71. This would be demonstrated by the growing number of self-publishers and Amazon’s own recent vertical move into publishing.

72. Also, the growth of Internet retailers would have leveled the playing field and provided easy access to consumers; and the growth in the self-publishing industry more generally would have led to the increasing commoditisation of publishing services, which may now be purchased separately from a range of suppliers. There would also be a large freelance marketplace in which the skills and expertise associated with publishing services may be purchased as needed.

73. The parties submit that it would therefore be relatively easy for companies with no previous publishing activities (for example retailers - as demonstrated by the example of Amazon - or Internet companies) to quickly enter the market as self-publishing service providers. Similarly overseas publishers with a focus in non-English language books could expand into English language countries with relative ease by purchasing the English language specific services they might lack (for example copy-editing and UK retailer distribution networks).

74. For all the above reasons, the parties submit that the transaction is unlikely to significantly impede effective competition in the market for the acquisition of publishing rights in the UK and Ireland.

Commission's assessment

75. In the absence of any third party market share data for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles, in order to accurately determine the parties' market position, it would be necessary to fully reconstruct the upstream market(s) by identifying all amounts that are being paid as consideration for publishing rights, that is to say all advances and royalty rates negotiated between authors and publishers. However, for practical reasons such approach is not feasible. For this reason, the Commission first had to assess how best to approximate the parties' market position on the market(s) for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles. In a next step, the Commission applied the chosen method in order to assess the parties' market position within the overall market structure, before considering additional elements that impact upon competition in the upstream market(s).

a) Methods to measure the parties' market position in the upstream market for the acquisition of authors' rights

76. The Commission considered and market-tested two different methods in order to approximately measure the parties' position in the upstream market(s) for the acquisition of authors' rights. Firstly, based on the methodology used in Lagardère, the Commission considered using the advances paid by publishers for bestselling titles as proxy to measure the parties' market position on the upstream market(s). Secondly, as suggested by the parties, the Commission considered using their market shares on the downstream market(s) for the sale of English language books to dealers as a proxy for their position on the upstream market(s) for the acquisition of authors' rights.

77. In Lagardère, the Commission analysed the market position of the then merging parties by looking at their share in the payment of author's advances paid by publishers for the top 100 annual bestsellers. Following this approach, the Commission also investigated, for the purpose of the present transaction, whether measuring the authors' advances paid by publishers for the top 100 annual bestsellers in general or in the relevant categories (general literature, children's books, guides and manuals) may be a relevant proxy for determining the parties' competitive position in the upstream market(s) for the acquisition of authors' rights.

78. The market investigation provided mixed results on this question. On the one hand, two publishers explained that measuring the level of advances was a good measure of competitive strength since advance payments are a key priority for agents and authors, and as such, are therefore important in assessing a publisher's market power in the upstream market. However, on the other hand, a literary agent explained that the level of advances is so varied that they cannot be compared to take a view on the upstream market power of different publishers. Another publisher also explained that bestsellers do not represent the entire publishing market and that "there are many other types of copyrights that can be successfully acquired beyond the top 100".36

79. Furthermore, the Commission was not able to collect the advances being paid for all titles that figured among the 100 annual bestsellers in the above-mentioned categories. For this reason, the Commission was only able to partially reconstruct the sample. While this partial reconstruction does not allow the Commission to determine the parties' position on the upstream market(s) based on the level of advances they paid, it does however allow to confirm that in the present case the second method to measure the parties' market power, that is to say using their market shares on the downstream market(s) for the sale of English language books to dealers, constitutes a good proxy for their position upstream, as explained in greater detail below.

80. The market investigation also yielded mixed results on whether the downstream market shares for the sale of English language books to dealers constitute a relevant proxy for the calculation of the upstream market shares for the acquisition of authors' rights. On the one hand, a number of literary agents and publishers explained that the downstream market shares for the sale of English language books to dealers could be indicative to a certain extent of the market power in the upstream market for the acquisition of authors' rights, since, as one publisher summarized: "a publisher's strength in the markets for the sale of books to distributors is a factor that some authors may take into account in selecting among publishers and […] may find that success in the downstream market is indicative of a publisher's market prowess, and favour certain publishers accordingly".37

81. On the other hand, several respondents indicated that since authors take into account a variety of factors when choosing between publishers, some of which being highly subjective, a publisher's position in the author's rights acquisition market cannot be said to generally reflect its position in the market for the sale of book to dealers. In addition, one respondent suggested that an extrapolation from the market position in the downstream market to the upstream market could offer misleading conclusions as for instance, in order to gain a large market share, "a publisher would need to acquire considerably more rights than other publishers, as a good proportion of what is published will prove unsuccessful in the market place. Equally, a publisher could gain an increased market share [downstream] boosted by a particularly strong selling author, series or book", which would not necessarily reflect its position in the upstream market for the acquisition of author's rights.38

82. Based on the advances collected from the parties and several of their main competitors, given the mixed views of participants in the market investigation, the Commission carried out a comparison of the parties' scaled market share on a sample upstream market and on a sample downstream market. The Commission used the information submitted by the parties on the advances that they paid in 2011 and 2012 for top 100 bestselling titles in the categories of general literature, children's books and guides and manuals, as well as these respective amounts collected from their main competitors. The Commission then calculated the parties' advance shares in the sample upstream market, which obviously only represents a share of all advances paid by publishers to authors in 2011 and 2012. In a next step, the Commission calculated the sales values of the downstream sales of books that corresponded to the titles included in the sample upstream market. The Commission subsequently proceeded to the calculation of the shares that the parties and their competitors that were included in this exercise achieved with the sale of titles that were classified among the top 100 bestselling general literature titles, children's books or guide and manuals on the downstream market. As shown by table 4 below, the parties' scaled shares on the sample upstream and the sample downstream markets are in the same order of magnitude.

Table 4: The parties' scaled market shares for a sample markets comprising the top 100 bestselling general literature titles, children's books and guides and manuals in 2011 and 2012.

| Penguin | Random House |

Scaled upstream market share | [20-30]% | [30-40]% |

Scaled downstream market share | [20-30]% | [30-40]% |

83. For this reason, the Commission is satisfied that despite certain doubts raised by participants in the market investigation, in the present case, the parties' market shares on the downstream market(s) for the sale of books to dealers constitute a good proxy for their position on the upstream market for the acquisition of the respective publishing rights.

b) The parties' position on the upstream market(s) for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles

84. The market data available for the parties' sales on the downstream market for the sales of English language books to dealers is limited to the UK and Ireland. As explained in more detail in paragraph 184 below, the Commission considers that the parties' market share in UK and Ireland reflect accurately their position on a wider geographic market covering the entire EEA. For this reason, the Commission considers that an assessment of the parties' position on a possibly EEA-wide upstream market for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles can be based on the available market data for the downstream sale of English language books in the UK and Ireland.

85. Furthermore, the Commission considers that the parties' position on the upstream market on the level of the EEA would be the same or stronger than on the worldwide level. The parties explained that they face the same internationally active competitors on a worldwide level, and that the United States, where the majority of English language rights originate is lower than in the EEA, see table 2 above. Hence, their combined market share on the worldwide level would be roughly the same if not lower on the worldwide level. For this reason, the Commission can limit the competitive assessment of the upstream market to the EEA. Since the transaction does not raise competition concerns on the more narrow geographic level of the EEA, the Commission can also exclude competition concerns on the worldwide level.

86. Based on the market shares of the merging parties on the downstream market(s) for the sale of English language books to dealers as a proxy for their position on the upstream market(s) for the acquisition of author's rights, their combined market position post-transaction will remain limited, and there will remain a number of significant competitors with relevant market shares that will continue to compete with the merged entity, overall but also in separate categories of books such as general literature, children's books or guides and manuals, where the parties are mostly active.

87. As outlined above in table 2, the parties combined market share on the overall market for the sale of English language books to dealers in the UK and Ireland, amounted to [20-30]% by value in 2012. Hence, their combined market share on an overall market for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles would remain in the same order. As shown by table 2, the merged entity would continue competing against several larger publishers, including Hachette with a market share of [10-20]% by value in 2012, HarperCollins with a market share of [5- 10]% by value in 2012 and Pan Macmillan with a market share of [0-5]% by value in 2012, as well as against a large number of smaller publishers, which in 2012 made up [40-50]% of the market. Furthermore, according to the majority of literary agents who participated in the market investigation, the merged entity is unlikely to unilaterally increase or decrease the level of advances paid to authors. None of the respondents esteemed that the merged entity will offer higher advances to authors and only two out of seven respondents anticipated a decrease in advances paid by the merged entity. The majority of respondents either believe that the transaction will have no impact on the level of advances or find it impossible to predict the possible effect of the transaction.39

88. Even if the upstream market for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles were to be divided by category of titles, the picture would not change significantly. As shown by table 3 below, the parties combined market share by value in the possible markets for the acquisition of publishing rights for (i) children's books; (ii) guides and manuals; (iii) strip cartoon albums, (iv) art books and (v) academic and professional books remained below 30% from 2009 to 2012. In the category of general literature, the combined market share was slightly higher in the period from 2009 to 2011, during which it ranged between [30-40]% and [30-40]%. Only in 2012, the parties' combined market share amounted to [30-40]%, which is explained with the exceptional success of a particular trilogy published by Random House in that year ("Fifty shades of grey", "Fifty shades darker", and "Fifty shades freed" by EL James, hereafter "Fifty Shades trilogy"). The Commission considers that the unprecedented success of this particular trilogy needs to be taken into account when assessing the merged entity's market position. Hence, the 2012 market shares alone do not accurately reflect the parties' market position on the downstream market for the sale of English general literature titles, which is better depicted by their market shares over the period from 2009 to 2012. By analogy, the parties' position on the upstream market for the acquisition or publishing rights for general literature titles is more accurately reflected by the level of their downstream market shares in the period from 2009 to 2012 than by their downstream share in 2012 only.

Table 5: Parties' combined share in the markets for the acquisition of publishing rights divided by book category (based on sales of physical books to dealers as a proxy – UK and Ireland, by value, 2009-2012)

Category | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 |

General literature | [30-40]% | [30-40]% | [30-40]% | [30-40]% |

Children's books | [20-30]% | [20-30]% | [20-30]% | [20-30]% |

Art books | [5-10]% | [5-10]% | [5-10]% | [10-20]% |

Guides and manuals | [20-30]% | [20-30]% | [20-30]% | [20-30]% |

Strip cartoon albums | [0-5]% | [0-5]% | [0-5]% | [0-5]% |

Academic and professional books | [0-5]% | [0-5]% | [0-5]% | [0-5]% |

Source: Nielsen Bookscan

89. On this basis, the Commission concludes that the parties' combined positions on possible separate upstream markets for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles divided by category of title are not of such magnitude that would allow the merged entity to act independently of its competitors and cause non- coordinated effects.

90. If the upstream market was to be divided into the acquisition of publishing rights for English language print books, e-books and audiobooks, the assessment would not change as shown by the respective market share levels on the downstream markets, see paragraphs 193 to 200.

91. Finally, the market investigation did not reveal any indications for a stronger position of the parties on a possible market for the acquisition of publishing rights of a foreign-language title to be translated into English and released in English language.

92. In summary, the Commission considers that based on the merged entity's combined market share on the downstream market(s) for the sale of English language books to dealers as a proxy for its position on the upstream market(s) for the acquisition of the respective publishing rights, the merged entity would not hold a sufficiently strong market position on the overall upstream market and its possible segmentation in order to cause the risk of non-coordinated effects.

93. This finding is strengthened by the following additional factors, which have a bearing on the level of competition in the upstream markets for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language titles.

c) Existence of a variety of factors on which publishers compete vis-à-vis authors

94. First, the market investigation did not fully confirm the parties' submission that it is not uncommon for a publisher that has not offered the most lucrative advance or royalties' proposal to be nonetheless the successful bidder because the author has a personal preference for that publisher due to non-price reasons. On the one hand, the Commission analysis of the 2011-2012 authors’ win and loss data provided by the parties shows that, […]. However, this analysis could not be considered as complete as the level of advances offered by competing publishers was not available in a significant number of instances to the parties. In addition, a large number of market participants confirmed that "right contracts depend on a multitude of factors" and "it is difficult to predict since negotiations with each author are treated on a case by case basis and authors have different preferences and affinities".

d) Level of advances generally affordable to medium-sized and smaller publishers

95. Taking the worst case scenario hypothesis that the level of advances was the sole or primary motivator behind an author's selection of a particular publisher, the Commission assessed the likely impact of the merger on the level of advances overall. Furthermore, as one publisher explained that "the top end of celebrity and genre fiction publishing is expensive, as the books have major appeal and are financially highly lucrative. To buy these rights and to publish them successfully requires strong financial resources"40, the Commission also assessed the impact of the merger on a possible market segment within the overall market of the acquisition of authors' rights, namely the acquisition of authors' rights for a consideration above GBP 500,000 (which corresponds to the higher advances paid to authors).

96. As regards the overall market, the Commission was able to collect partial information from a number of literary agents and publishers on the average amount of advances they received for the authors they represented in 2011 and 2012. These amounts varied greatly for different literary agents and publishers. The respective average advances ranged from around EUR 30,000 to not more than EUR 145,000.41

97. The Commission acknowledges the comments from a number of market participants that some of the high amount of advances paid to bestselling or celebrity authors may distort the picture given by the average amount of advances paid by publishers.42

98. Nevertheless, the parties also submitted figures showing that the median advances paid to authors by Random House and Penguin between 2009 and 2011 were GBP […] and GBP […] respectively. In addition, according to the parties' figures, [80- 90]% or more of their authors' rights were purchased for GBP 50,000 (EUR 57,325) or less, and for more than [90-100]% of all titles published, authors received an advance below GBP 100,000 (EUR 114,650).

99. The Commission considers that the amounts of advances paid by the parties may be taken as a proxy for the entire publishing industry in the UK and Ireland, given the relatively low level of these amounts even for the first and third largest publishers in the UK and Ireland that Random House and Penguin are. Furthermore, the Commission, also analysing the 2011-2012 authors’ win and loss data provided by the parties, confirms that in practice, competing mid-sized or smaller publishers have bid for such amounts or larger amounts of advances in the past two years. As a result, the Commission considers that amounts of up to GBP 50,000 or even GBP 100,000 must be affordable also for a number of larger and even smaller publishers competing with the merging parties in the acquisition of author's rights.

100. As regards the possible separate market segment for the acquisition of publishing rights for a consideration above GBP 500,000, the Commission, analysing the figures of the parties first recognises that a number of authors have been paid advances which ranged between GBP 500,000 to GBP 2 million. However, according to the parties' own computations, only [0-5]% for Random House and only [0-5]% for Penguin of all books titles published between 2009 and 2011 received an advance in excess of GBP 500,000 (EUR 573,250). Therefore, even if, taking the worst case scenario, the merging parties were the only publishers to be able to afford to pay such high advances post-transaction, they would only be able to foreclose a very small minority of the market (between [0-5] and [0-5]%), leaving other publishers to be able to compete for at least [80-90]% if not [90-100]% of the market for the acquisition of authors rights.

101. Furthermore, analysing the 2011-2012 authors’ win and loss data provided by the parties, competing publishers have bid during that period for authors in a large number of instances for amounts ranging over GBP 100,000 and going up to between GBP 1 million, and up to GBP 3 million in […] instances.

102. The Commission considers that this demonstrates that other publishers are currently able and do currently compete with the merging parties, also on the high bids for well reputed or bestseller/ brand authors.

103. The Commission assessed whether the proposed transaction would change this situation.

104. First, the results of the market investigation were mixed as to the question whether the merged entity would be in a position to offer more attractive publishing contracts (including a higher level of advances) to authors compared to their offerings today.

105. On one hand, two publishers believed that the marketing power of the merged entity will be "more attractive to many authors" as it will "have more distribution power due to its size and therefore [will be] able to command more power at retail and therefore probably reach a wider audience". Another publisher also believed that the merged entity would be able to pay higher advances to authors.43

106. On the other hand, a publisher explained that advances are already generous today and the proposed transaction should not change that situation, while two other publishers explained that it was difficult to predict whether the merged entity would be more attractive to authors post-transaction as "right contracts depend on a multitude of factors" and "it is difficult to predict since negotiations with each authors are treated on a case by case basis and authors have different preferences and affinities". Likewise, another publisher explained that "it does not seem likely […] that the contracts will be greatly different in ways other than industry norms." In addition, a publisher also explained that even if "the merger will generate synergies that the merged entity may be able to pass on to authors in the form of more attractive terms […] the merged entity will still face fierce competition from other publishers who may be able to offer equally attractive or more attractive terms".44

107. Furthermore, none of the literary agents which replied to the market investigation believed either that the merged entity would be in a position to offer more attractive publishing contracts to authors compared to the contracts currently offered by Random House and Penguin or by their competitors.45

108. Secondly, the market investigation did not fully confirm either that the merged entity would be in a position to successfully sign more promising, well-reputed or best- selling authors than Random House and Penguin do today. Even if one literary agent believed that "their market share and financial strength would enable them to outbid, in advance and resources terms, other publishers, more often that they do now", two explained that already prior to the transaction, the merging parties did not have difficulties to attract such authors so the situation will not change post- transaction.46

109.Thirdly, when asked whether the combined Penguin Random House would become so strong for the acquisition of publishing rights for English language print and e- books and audio books that other publishers would find it difficult to compete with the merged entity, one literary agent explained that the merged entity's "position in the upstream market will be strengthened relative to their market share of the downstream market to the extent that in a significant number of cases we would expect them to prevail over competitors". However, another literary agent explained that "there is plenty of competition – both from other publishers and because authors can also self-publish. Amazon's self-publishing service will continue to provide serious competition – and it is much larger than either Random house or Penguin".47

110. In addition, the vast majority of publishers did not consider that the combined Penguin Random House would become so strong for the acquisition of publishing rights that other publishers would find it difficult to compete with the merged entity. As one publisher explained: "book publishing is a fiercely competitive industry comprising numerous players of widely varying sizes, ages and specialties […] authors take into account a wide array of factors in deciding between publishers, and as such, while the merged entity may be more attractive to certain [authors] in certain respects, it will not be capable of making it appreciably more difficult for other publishers to compete in the rights acquisition market". Similarly, according to another publisher, "the merged business may be stronger than the separate companies, but not to a very great degree in our views. As far as marketing and editorial strengths are concerned, they won't become "so strong" through merger".48

111. In light of the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers it more likely than not that post-transaction, larger as well as medium-sized and smaller publishers will continue to compete with the merged entity on the level of advances in the overall market for publishing rights, as well as in the segment for higher priced publishing rights.

Conclusion on non-coordinated effects

112. In light of the above, the Commission concludes that the proposed transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market in the upstream market(s) for the acquisition of author's rights as regards non-coordinated effects.

2.3.2. Coordinated effects

113. The Commission assessed whether the proposed transaction may create any risk of coordinated effects in relation to the acquisition of authors rights by publishers. In particular, the Commission assessed whether the publishers (all of them or only the larger ones) may tacitly coordinate their behaviour in order to reduce the amount of advances paid or the level of royalties paid to authors.

114. To assess coordinated effects, well-established case law49 and Commission guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers50 require proof that the merger will make coordination more likely, more effective and more sustainable. The analysis needs to focus in particular on: (i) the ability to reach terms of coordination; (ii) the ability to monitor deviations; (iii) the existence of a credible deterrent mechanism if deviation is detected; and (iv) the reactions of outsiders such as potential competitors and customers.

115. The Commission first investigated whether, and if yes to what extent, the amount of the advances and the level of royalties that was agreed among the winning publisher and an author in an auction or bidding procedure were generally known in the market, so that competing publishers would be able to detect any deviation from the amount of advances or level or royalty tacitly agreed between competing publishers.

116. As regards first the amount of advances, even though a number of author's agents and publishers which replied to the market investigation explained that "on occasion, the specific amount paid becomes known [and that] more commonly there may be a range of speculation about the advance, [...]", a vast majority of author's agents and publishers confirmed that this information was not publicly available, or made known to other publishers.51

117. As regards second the level of royalties, the vast majority of literary agents and publishers confirmed that coordination on royalty rates was unlikely given that the rates are negotiated individually and are not normally disclosed publicly. As one literary agent explained: "there is not as much variability in royalty rates as there is in advances. To the extent that agreed royalty rates resulting from an auction may vary from customary industry parameters, the royalty rates may sometimes become known to other publishers participating in the auction, but it is our sense that the rates are generally not made known to other publishers".52

118. The Commission therefore considers that the market for the acquisition of authors' rights is unlikely to be sufficiently transparent to allow monitoring deviation from any hypothetical tacitly agreed amount of advance or level of royalty and that therefore, the transaction is unlikely create any risk of coordinated effects on that market.

119. The Commission also investigated whether it would be likely that only large publishers - that is to say, excluding small and medium-sized publishers - would coordinate their behaviour on the market for the acquisition of authors' rights.

120. A large majority of publishers, including smaller publishers, explained that it was unlikely, given the competitive nature of the publishing industry, the number of competing publishers, and the continual changes within the industry, that large publishers would be able to coordinate their behaviour on the market for the acquisition of author’s rights.53 Only one publisher and one literary agent raised the concern that there may be coordination between the large publishers, specifically on the level of royalty rates for e-books.

121. On this latter point, the Commission notes however that the e-book royalty rate is just one of a range of key parameters on which publishers compete for authors’ rights. These parameters include non-price parameters such as editorial skill, the reputation of publishers, and their marketing and promotional skills, as well as other price parameters such as the level of advances paid and royalty rates, not only for e- books but also for all other formats or sales.

122. Furthermore, as was confirmed in paragraph 117, e-books royalty rates negotiated with authors/authors’ agents (and the other key pricing parameters for acquiring authors’ rights such as advances and royalty rates on print books) are not generally made public and are not tracked by third party data providers such as Nielsen Bookscan.

123. Moreover, […], different royalty rates apply for other formats such as physical books; for sales in home markets and export markets; […]. Against this backdrop, the disclosure of e-book royalty rates cannot bring any meaningful transparency to the entirety of the price component of the way in which large publishers compete for authors’ rights.

124. Based on the above, the Commission takes the view that it is unlikely that there is sufficient market transparency to facilitate coordination on e-book royalty rates.

Conclusion

125. The Commission concludes that the proposed transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market in the upstream market(s) for the acquisition of author's rights arising from a risk of coordinated effects.

3. Sales of English Language Books to Dealers

3.1. Product market definition

3.1.1. View of the parties

126. The parties submit that the relevant market is the sale of English language consumer books to dealers in the EEA (primarily in the UK and Ireland).

127. According to the parties, print books, e-books and audio books are part of the same product market. Moreover, they do not consider it necessary to segment the market by sales channel, categories of titles (that is to say general literature, children's books, art books, guides and manuals, etc.) or, as regards print books in the general literature category, by format (that is to say hardback and paperback). However, the parties provide the relevant market data and submit that the exact product market definition can be left open as the competitive analysis remains unchanged.

128. First, as regards a possible segmentation between print books, e-books and audio books, the parties submit that all formats are part of the same relevant product market.

129. E-books are considered to be a competitive constraint on print books and vice-versa as (i) publishers are generally active across e-books and physical books; (ii) publishing rights typically are acquired jointly for physical and digital sales; (iii) the content of the title is essentially identical whether purchased in digital or physical form; (iv) the same factors will influence consumer purchases of both e-books and physical books and consumers tend to purchase a given title in only one format; (v) the e-book and hardback versions of a title are published at the same time; (vi) the decline in print sales coincides with the growth in e-book sales; and (vii) the wholesale pricing of e- books is linked to the recommended retail price ("RRP") of physical books.

130.The parties submit that it is neither necessary nor meaningful to sub-divide the supply of e-books into separate markets for the supply of e-books to dealers under a resale (wholesale) model and the supply of e-books through dealers under an agency model. The choice of distribution model is simply a commercial issue to be negotiated between the publisher and the dealer within the confines of the market for the sale of consumer books. The choice between agency and resale distribution is thus not a choice between two separate markets, but simply between the commercial terms in which the parties distribute within the market via intermediaries (that is to say dealers).

131. In relation to audio books the parties submit that there is supply- and demand side substitution between audio books and other book formats because (i) with a few exceptions54, there is no discernible difference in customer taste between physical, e- book and audio book formats; (ii) the same publishers are largely active across all three formats, although certain audio book publishers (notably the BBC) are substantially less active in print book and e-book publishing; (iii) publishers seek to and generally do obtain audio book rights together with print book and e-book rights; (iv) the content is substantially the same as for the print book and e-book format; (v) if possible, audio books are published at the same time as the e-book or the hardback print book55; (vi) marketing is directed at print, e-book and audio book format of a given title; (vii) many print book and e-book retailers also sell audio books (for example Waterstones, WH Smith, Amazon); and (viii) pricing to retail customers is determined in essentially the same way as print books/e-books; that is to say, a discount off the RRP for physical audiobooks and a further discount off that RRP for digital audiobooks. The parties do not consider a further distinction between digital and physical audio books.

132. Second, the parties do not consider it necessary to subdivide the market by sales channel. First, the conditions of competition are the same across all dealers, as the same dealers will purchase books across a large range of publishers. Second, different publishers organise their sales teams across many different lines and not necessarily along the different types of dealers.56 Finally, in relation to e-books the parties submit that any further segmentation is unnecessary as, according to their estimates, Amazon accounts for approximately [90-100]% of all e-book sales in the UK and Ireland.

133. Third, the parties do not consider there to be a need for a subdivision of the market by categories of titles. They submit that there is potential for both substantial supply side and demand side substitutability across the categories. In particular, the book acquisition, publication, and sales process are very similar across different categories and publishers will tend to be active across a large range of categories.

134.Also, due to strong supply side and demand side substitutability the parties do not consider a further subdivision within any possible categories according to genre (that is to say romance, crime thriller, science fiction, travel literature, children's fantasy etc.) to be meaningful or appropriate.

135. Fourth, as regards print books in a possible general literature category, the parties submit that hardback and paperback formats are part of the same product market. The large majority of titles will be published both as hardback and paperback title, with the edition reflecting the life cycle of a book and the price differential reflecting the cost differences in production as well as consumer preferences. From a supply- side perspective, as set out in paragraph 27, the parties do not consider it appropriate to distinguish between the acquisition of rights for both formats. From a demand- side perspective, customers are said to be generally prepared to purchase both formats. Moreover, there is competition between both formats as is evidenced by the negative effect the "Fifty shades" trilogy published by Random House in 2012 had on other book sales even though very few hardback copies of this trilogy have been sold.

136. Fifth, the parties do not consider that bestsellers constitute a separate market. They submit that there is no industry standard definition for bestsellers and no step-change in the volumes of books sold according to their chart positions thereby not supporting a market definition according to chart positions. Moreover, sales rankings vary substantially over time so that a given title may be in the top 200 titles in a given week but only in the top 1000 a few weeks later. Apart from demand, seasonal factors are also claimed to affect sales, which suggests that sales of a given title may vary depending on the date of its launch. Furthermore, consumers and dealers make their choices across the full range of bestsellers and non-bestsellers. In addition, the publishers' objective is to increase the volumes of each title sold but it is uncertain if a title is going to be a bestseller or not when the rights are acquired and when a title is launched. Finally, the parties note that high-selling generally titles tend to be discounted more and enjoy greater promotional spend than less successful titles.

3.1.2. Commission's assessment

137. The Commission concluded in Lagardère that the market for the sale of French language (print) books to dealers should be subdivided according to the types of dealer.57 The Commission also subdivided the market by categories of titles and, for some categories defined further subcategories58 but it did not further subdivide these categories by genre59. Within the general literature category, the Commission further defined separate markets according to the format (hardback vs. paperback).60

138. Preceding the assessment of the relevant product markets, the Commission notes in relation to the publishers' sales of e-books that, for the purposes of the present decision, no distinction is made as to whether e-books are sold to dealers under the wholesale model or whether they are sold through dealers under the agency model.

Possible distinction between print books, e-books and audio books

139. In Lagardère, the Commission did not consider a distinction between print books and audio books.61

140. The market investigation revealed, first, that print books and e-books may constitute separate product markets.

141. The majority of responding publishers and customers consider that print books and e-books differ in terms of (i) sales channel; (ii) pricing at wholesale level; (iii) pricing at retail level; and (iv) promotion of specific titles. Unlike the responding customers, the majority of publishers did not see any differences in terms of (i) the typical end-customer; and (ii) the mode of consumption, that is to say if a title is read at home, when travelling, etc.62

142. The results of the market investigation are more mixed as regards substitutability of the two formats. Nevertheless, the majority of responding publishers and customers do not consider that wholesalers or retailers would switch from print books to e-books and vice-versa in case of 5-10% increase in price.63 Moreover, the majority of responding customers consider that the vast majority of consumers would not switch from print books to e-books and vice-versa in case of a 5-10% increase in the retail price Only two customers consider, without providing further details, that 10-25% of end-customers would switch while a minority of customers consider that most consumers would switch in the event of a price increase of this magnitude.64

143. Second, the market investigation showed that audio books are distinct from print books.65

144.The majority of responding publishers and customers consider audio books to differ from print books in terms of (i) pricing at wholesale level; (ii) pricing at retail level (audio books tend to be more expensive both at wholesale and retail level); and (iii) promotion of specific titles. The majority of customers also see differences in terms of the typical end customer and the mode of consumption while results are mixed in this respect for the responding publishers. Overall, results are mixed as regards the sales channels through which both products are sold.