Commission, March 20, 2017, No M.8283

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Judgment

GENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANY / LM WIND POWER HOLDING

Subject: Case M.8283 – GENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANY / LM WIND POWER HOLDING

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/2004 (1) and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (2)

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 13 February 2017, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which General Electric Company ("GE", USA) acquires sole control over LM Wind Power Holding A/S ("LM", Denmark) within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation, by means of purchase of shares (hereafter the "Transaction"). (3) GE is referred to as the "Notifying Party" and collectively with LM as the "Parties".

(2) The same Transaction was already notified to the Commission on 12.01.2017, but subsequently withdrawn on 02.02.2017.

1. THE PARTIES AND THE CONCENTRATION

(1) GE is a global manufacturing, technology and services company that is made up of a number of business units, each with its own divisions. GE is a diversified company and GE Renewable Energy is the business unit that produces and supplies wind turbines for onshore and offshore use on a global basis. It also services wind turbines, primarily for its own installed fleet.

(2) LM is active in the design, testing, manufacturing and supply of wind turbine blades, both in the EEA and worldwide.

(3) Pursuant to the Share Purchase Agreement ("SPA") of 11 October 2016, GE has agreed to acquire 98.23% of the issued ordinary share capital of LM and 99.87% of the issued preference share capital of LM. Following the Transaction GE will acquire sole control over LM, within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

2. EU DIMENSION

(4) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million. (4) Each of them has an EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million, but they do not achieve more than two-thirds of their aggregate EU-wide turnover within one and the same Member State. The notified operation therefore has an EU dimension within the meaning of Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

3. RELEVANT MARKETS

(5) LM designs, manufactures and supplies blades to wind turbine original equipment manufacturers ("OEMs") such as GE. GE develops, designs and manufactures wind turbines. Contrary to most major wind turbine OEMs, GE does not manufacture blades in-house for its wind turbines but rather sources them from third party manufacturers such as LM. (5)

(6) The Parties' activities do not overlap horizontally. However, the Transaction gives rise to vertically affected markets with regard to the integration of the upstream activities (blade manufacturing) by a downstream player (wind turbine OEM).

3.1. Product market definition

3.1.1. Manufacturing of blades (upstream)

(7) Blades are important components of wind turbines. They capture the energy from wind and transfer it to the turbine, impacting turbine performance. On average, blades account for 20-25% of the total wind turbine cost. Blade production consists of the design and engineering of the blade (including the choice of materials), and the tooling, construction, prototyping and certification of the blades.

3.1.1.1. Distinction between onshore and offshore blades

View of the Notifying Party

(8) The Notifying Party submits that offshore blades differ from onshore blades mainly in size and weight. Offshore blades are longer, heavier and generally built to be more robust and more resistant to stronger winds. However, with respect to technology, the blades are not materially different from onshore blades. To address the difference in size and weight, the Notifying Party argues that an onshore blade manufacturer willing to enter the offshore market would only need to extend the size of its manufacturing plant, which requires limited cost and time.

Commission's assessment

(9) The market investigation confirmed that the difference between onshore and offshore blades is mainly in the size of the blade and the mould required to manufacture it, rather than in the technology.

(10) From a demand-side point of view, customers of blades have pointed out some differences between onshore and offshore blades in terms of price, performance, properties and design that are relative to the technical characteristics of onshore turbines as compared to offshore turbines, as the latter are bigger and have a higher power output. (6) However, as explained above, the main difference lies in the size; (7) otherwise, "the blades are in principle the same". (8)

(11) From a supply-side point of view, blade manufacturers consider that either they are already able to manufacture both onshore and offshore blades, or they could expand their plants to accommodate a larger blade and its mould. Indeed, while the length of the blade is the most important parameter to distinguish onshore and offshore blades, the production process can be adapted to a wide range of lengths. (9) The wind turbine OEMs that produce blades in-house have also emphasized that the main difference between onshore and offshore blades is the length. (10) All major wind turbine OEMs with in-house production that responded to the questionnaire have declared that they are able to produce both onshore and offshore blades. (11) The fact that blades for offshore wind turbines are larger does not prevent a manufacturer of onshore blades from producing offshore blades. Such substitutability from the supply-side is therefore considered sufficient not to differentiate between distinct blade markets in terms of size.

(12) It can therefore be concluded from the market investigation that the manufacturing of onshore and offshore blades does not appear to differ to such extent as to constitute separate markets. This is especially true given that, from a supply-side point of view, blade manufacturers can produce offshore blades without significant hurdles.

(13) However, the Commission considers that the question of whether there is a segmentation between the manufacturing of blades onshore and offshore can be left open, since the Transaction will not give rise to serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of the market definition retained.

3.1.1.2. Distinction between the blade materials used

(a) Distinction between polyester and epoxy resin laminated blades

View of the Notifying Party

(14) The Notifying Party submits that further segmentation of the market based on the choice of resin, namely between epoxy and polyester, is not justified. While there are differences in the capital expenditure, environment, health and safety considerations between the two resin types, there are no performance or competitive distinctions between blades made of the two materials. LM produces only polyester blades.

Commission's assessment

(15) The market investigation confirmed that a further sub-segmentation of the market according to the blades' resin type does not appear to be warranted.

(16) From a demand-side point of view, the market investigation shows that differences between types of resins are perceived mostly in terms of price and design. (12) However, the material used for the blade is not systematically specified when a wind turbine OEM requests a design from an external blade designer. (13) Furthermore, some of the major wind turbine OEMs use both epoxy and polyester blades. By way of example, for offshore applications, Gamesa manufactures epoxy blades for its 5MW turbine in-house, while it outsources polyester blades for its 8MW turbine (AD8-180). (14) For onshore applications, Gamesa works with dual-designs for the same turbine, where it manufactures epoxy blades in-house and outsources polyester blades to fit the same turbine model. (15) Other wind turbine OEMs use both polyester and epoxy depending on the blades, or sometimes use both for a given blade design.

(17) In any case, end customers that will acquire the turbine (utilities, wind farm owners, etc.) do not specify the blade material in the tender they issue. This demonstrates that the choice of material does not constitute a competitive distinction in itself. Therefore, a sub-segmentation by resin type does not appear appropriate from a demand-side perspective.

(18) From a supply-side point of view, blade manufacturers pointed to differences in the production process between polyester and epoxy blades. However, switching from one to the other is not considered a "major obstacle". (16) A competitor mentioned that most blade manufacturers have "enough flexibility to use different materials." (17) Similarly, another competitor considers these two technologies are "used interchangeably by the blade manufacturers". (18) A wind turbine OEM manufacturing blades in-house also explained that although it is not a straight forward process, starting to manufacture blades with different materials is possible. (19) The choice of resin type can be attributed to the fact that each blade manufacturer has its own production strategy and process. (20)

(19) In light of the above, the Commission considers for the purpose of the present case that the resin type of the blades does not appear to be a differentiating element in defining the relevant market for blades.

(b) Distinction between glass and carbon fibre blades

View of the Notifying Party

(20) The Notifying Party submits that further segmentation of the market based on the choice of fibre, namely between glass and carbon, is not justified. While there are differences in price and weight between the two fibre types, there are no competitive distinctions between blades of the two materials. LM produces both carbon and glass fibre blades.

Commission's assessment

(21) The market investigation confirmed that a further sub-segmentation of the market according to fibre type of the blades does not seem appropriate.

(22) From a demand-side point of view, the market investigation shows differences in price, performance, properties and design between carbon and glass. (21) Nevertheless, most wind turbine OEMs, such as MHI Vestas, Nordex and Gamesa, use both glass and carbon fibre. (22) From a demand-side perspective, the two fibres can thus be considered as substitutable.

(23) In any case, end-customers that will acquire and install the turbine (utilities, wind farm owners, etc.) do not specify the material of the blade in the tender they issue. This demonstrates the material of the blade does not constitute a competitive distinction in itself. Therefore, a sub-segmentation by fibre type does not appear appropriate from a demand-side perspective.

(24) From a supply-side point of view, blade manufacturers and wind turbine OEMs that manufacture blades in-house are capable of producing, or consider it is possible to produce, both types of fibre blades. In that respect, a competitor mentioned that most blade manufacturers have "enough flexibility to use different materials." (23) Enercon produces in-house both glass and carbon fibre blades in parallel (E-82 glass and E-82 carbon). (24) Another major blade manufacturer also produces both. (25)

(25) In light of the above, the Commission considers for the purpose of the present case that the fibre type of the blades does not appear to be a differentiating element in defining the relevant market for blades.

3.1.2. Manufacturing of wind turbines (downstream)

(26) Wind turbines can be installed onshore and offshore to convert wind energy into electricity, for the supply of electricity to the electrical grid.

(27) GE is supplying wind turbines for onshore applications ranging from 1.6MW to 3.8MW. GE also entered the offshore segment through the acquisition of Alstom and it currently offers the 6MW Haliade wind turbine. (26) In the onshore segment, Vestas, Enercon, Siemens, Senvion, Nordex/Acciona, Gamesa, Envision and other smaller players are active in the EEA. In the offshore segment, MHI/Vestas, Siemens, Senvion and Gamesa, through its subsidiary Adwen, are active in the EEA.

3.1.2.1. Distinction between onshore and offshore wind turbines

View of the Notifying Party

(28) The Notifying Party submits that onshore and offshore wind turbines are distinct product markets because of their different specifications. Offshore wind turbines have higher power outputs and, in the EEA, all offshore turbines are certified for wind class I, which corresponds to high winds sites, whereas onshore turbines are generally in wind class II or III. The size and weight of turbines are also of greater importance offshore. Overall, offshore turbines are more robust and expensive than onshore.

Commission decision making practice

(29) In GE Wind Turbines/Enron, while the exact market definition was ultimately left open, the Commission considered that wind turbines can be distinguished from other forms of power generation. (27) In GE Energy/Converteam, the Commission found a potential segmentation between onshore and offshore wind turbines in view of the differences in power output, installation, operation and maintenance resulting from the harsher environmental conditions and difficulties to access offshore wind farms. However, the exact market definition was left open. (28)

(30) In Siemens/Gamesa, (29) the Commission's market investigation indicated that the different conditions of the offshore environment affect the planning and construction of offshore projects and result in differences in design, performance and costs of the turbines to be installed. The dynamics of these two markets are different and result in different wind turbines required. Therefore, the Commission found that separate markets exist for the manufacturing and supply of onshore and of offshore wind turbines.

Commission's assessment

(31) The market investigation confirmed that the manufacturing and supply of onshore and of offshore wind turbines constitute separate markets.

(32) From a demand-side point of view, onshore and offshore turbines are not substitutable in view of their differences in size, which result in differences in output. Customers of wind turbines (e.g., utilities or project developers) have confirmed that "onshore and offshore turbines markets have to be distinguished as the technologies differ and the products cannot be considered substitutable." (30) Furthermore, demand for offshore wind turbines generally is for a full project, whereas onshore turbine demand is usually on a per unit basis. (31) Moreover, offshore sites in the EEA are high wind sites and larger turbines are better able to take advantage of strong offshore winds. Therefore, competitiveness of offshore turbines is mainly driven by the size. (32)

(33) Overall, the conditions of offshore projects translate into different requirements for the turbines to be installed in those projects. They respond to different technical and economic considerations and therefore are not substitutable with onshore turbines.

(34) From a supply-side point of view, "onshore and offshore markets should be distinguished based on the significant differences in product's design and project execution." (33) Scale is very important for offshore projects and smaller wind turbine OEMs cannot cope with the required development of projects, which are significantly larger in size, cost intensive and more complex than onshore projects. (34) Offshore projects are much more costly as the bigger weight of the turbine and the challenges of offshore installation have a larger impact on other costs, such as foundations and transportation.

(35) More generally, offshore projects are technically more challenging due to harsher environmental conditions and limited accessibility, which adds to the time, risks and costs of installation. (35) In addition, turbine transportation onshore is more complicated than offshore, while maintenance of offshore turbines is more complicated and expensive than onshore, because more resources need to be allocated to allow for regular intervention. (36)

(36) As a result, more robust technology is used in offshore products in order to minimize or avoid to the extent possible the need for intervention and repair, which requires specific infrastructure and entails very high costs. This is reflected in additional backup systems and remote monitoring systems; onshore design concepts for wind turbines are substantially different. (37) Also, wind turbines for the offshore environment feature different power ratings and sizes than onshore turbines. While onshore turbines are in the range of 2 to 4MW with a rotor diameter up to 140m, offshore wind turbines currently participating in tenders have power outputs between 6 and 9MW and a rotor diameter of up to 180m.

(37) In light of the above, and in line with its past approach, the Commission considers that the manufacturing and supply of onshore and of offshore wind turbines constitute distinct product markets.

3.1.2.2. Other segmentations

View of the Notifying Party

(38) The Notifying Party submits that no further segmentation should be made by wind class, power rating or frequency standard.

Commission's assessment

(39) The Commission has investigated potential further sub-segmentations by wind class, power rating or frequency standard but has not found them to be appropriate.

Wind class

(40) Wind classes refer to standards set by the International Electrotechnical Commission ("IEC"). Offshore sites in the EEA, as in most of the world, are characterised by higher wind speed and thus will require turbines certified for the highest wind class, namely IEC I. Onshore turbines are generally designed for wind classes IEC II or III. (38) However, as specified by a utility, a wind class II offshore turbine could be installed onshore if the conditions correspond to a class II site. Conversely, class I turbines can be installed onshore in windy regions. (39) Another utility explained that, overall, it had projects covering all wind classes. (40) From a demand side point of view, it therefore appears that a further sub- segmentation according to wind classes in not appropriate.

(41) Finally, if such segmentation were found, it would ultimately equate to the segmentation between the onshore and offshore wind turbine markets and is therefore not necessary.

Power rating

(42) As explained in paragraph 36 above, in the EEA, turbines of various power ratings are competing against one another in each of the onshore and the offshore markets.

(43) Boundaries between different power outputs are blurred. Even if project characteristics may favour one turbine size over others, in general there is substitution between the wind turbines in nearby power ratings. (41) In addition, each wind turbine OEM offers wind turbines of different outputs for onshore projects. However, offshore competitive dynamics result in the continuous development of bigger turbines. Therefore, a clear-cut segmentation by power rating cannot be found.

(44) Finally, if such segmentation were found, it would ultimately equate to the segmentation between the onshore and offshore wind turbine markets and is therefore not necessary.

Frequency standard

(45) Wind turbine design is not materially different depending on whether a turbine is installed in a 50 Hz or 60 Hz country. The blades and all major components are the same for a 50 Hz and a 60 Hz turbine. (42)

(46) It can therefore be concluded from the market investigation that the two downstream product markets are the markets for the manufacturing and supply of onshore and of offshore wind turbines.

3.2. Geographic market definition

3.2.1. Manufacturing of blades (upstream)

View of the Notifying Party

(47) The Notifying Party submits that the market for blades is at least EEA-wide, with significant imports from Turkey and Asia. Customer preferences and technical and environmental requirements relating to different blades are similar worldwide and across the EEA, with the exception of certain local requirements in Brazil, Russia, Canada and Iran.

Commission's assessment

(48) While a majority of wind turbine OEMs do not exclude sourcing blades for the turbines they install in the EEA from production locations outside the EEA, (43) the market investigation demonstrated that distance is an important factor for the wind turbine OEMs to decide from where to source blades. Wind turbine OEMs balance labour costs, transportation costs and local content requirements and, in general, this results in a preference for EEA-based blade producers. (44) Overall, wind turbine OEMs only source a limited number of blades outside the EEA. (45) In such cases, those blades usually originate from plants located in Turkey or China. (46) Such imports from outside the EEA are usually made from manufacturing plants owned by EEA-based blade manufacturers. Certain wind turbine OEMs have qualified, are in the process of qualifying or already tried to source blades from Chinese blade manufacturers, but the experience is limited at this stage.

(49) The market investigation suggests that, for the purposes of this case, the geographic market for the manufacturing of blades is likely not broader than the EEA. This reflects the fact that, for a wind turbine OEM, sourcing blades from outside the EEA is generally an inferior alternative to an EEA based blade supplier.

(50) The Commission considers that the exact geographic market definition can be left open, since the Transaction will not give rise to serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of the geographic market definition retained.

3.2.2. Manufacturing of wind turbines (downstream)

View of the Notifying Party

(51) The Notifying Party submits that both the onshore and offshore markets for the supply and manufacturing of wind turbines are at least EEA-wide. Technical requirements, customer preferences, prices and environmental requirements relating to different types of wind turbines are similar across the EEA and worldwide, and wind farm construction or operation firms source wind turbines from across Europe and even from outside Europe.

Commission decision making practice

(52) In GE Energy/Converteam, (47) the market investigation broadly confirmed competition for the supply of wind turbines was found to be at least EEA-wide, but left the exact market definition open. More recently, in Siemens/Gamesa, (48) the Commission considered the geographic market for the manufacturing and supply of onshore and of offshore wind turbines to be no wider than the EEA.

Commission's assessment

(53) The market investigation suggests that the geographic market for wind turbine manufacturing is likely no broader than the EEA.

(54) From a demand-side point of view, a customer explained that transportation "is also a cost and a risk factor. Having the turbines assembled close to the project reduces such a risk." (49) Furthermore, customers of wind turbines also require suppliers to be located in the vicinity of the project for servicing purposes. (50) Closeness to the site is essential, as was indicated by a wind turbine OEM: "[l]ocal presence in a country gives a supplier a competitive advantage as well as for the execution of the wind farm projects and the estimation of the related costs as for the provision of service for the wind farm within the operation phase." (51) As a result, developers of wind farms in the EEA invite to tenders wind turbine suppliers that are located within the EEA.

(55) From a supply-side point of view, all suppliers of wind turbines have a base in the EEA from which they serve EEA projects. Although they may source different components of the turbines, including blades, towers and nacelles, from manufacturing sites located worldwide, assembly is carried out in the EEA as close as possible to the wind farm in order to avoid logistical challenges and to lower the transportation costs. A distinction has "to be made between manufacturing and assembly of wind turbines. While sourcing turbines' components can be done globally, the assembly factories are not global, but at most regional. Many of them are located in Germany or in Denmark. It is not absolutely necessary to win a tender to have a local site of assembly for a supplier. However, it is definitely preferred to be able to assemble the turbines in the EEA, for European projects […]." (52)

(56) In Siemens/Gamesa, the Commission found that all EEA wind turbine suppliers effectively competed and were awarded tenders everywhere in the EEA regardless of where exactly their facilities were located. All suppliers have the capabilities to deploy servicing teams close to the sites from their bases within the EEA.

(57) In light of the above, the market investigation suggests that the geographic scope for the markets for the manufacturing and supply of onshore and of offshore wind turbines are likely EEA-wide. Transportation costs are more crucial for onshore turbines given the complexities of transporting large turbines by road instead of shipping them by sea to the offshore site. As explained by a customer: "there are no differences between onshore and offshore requirements – it is clearly advantageous to produce the large components close to the site." (53) On the other hand, offshore sites require a nearby team for servicing the installed turbines than for onshore sites, due to the difficulty of access.

(58) The Commission considers that it can be left open whether the scope of the market should be wider than the EEA, since the Transaction will not give rise to serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of the market definition retained.

3.2.3. Conclusion

(59) The Commission considers the narrowest relevant markets are the supply of blades in the EEA (upstream), the EEA-wide market for the manufacturing and supply of onshore wind turbines and the EEA-wide market for the manufacturing and supply of offshore wind turbines (downstream).

3.3. Servicing of blades and wind turbines

3.3.1. Servicing of blades

View of the Notifying Party

(60) The Notifying Party submits that GE and LM do not overlap with respect to servicing blades. GE only provides servicing with respect to wind turbines and subcontracts any blade servicing that may fall within the scope of servicing its turbines. LM provides blade servicing only for its own blades, and does not compete on the merchant market for blade servicing. (54)

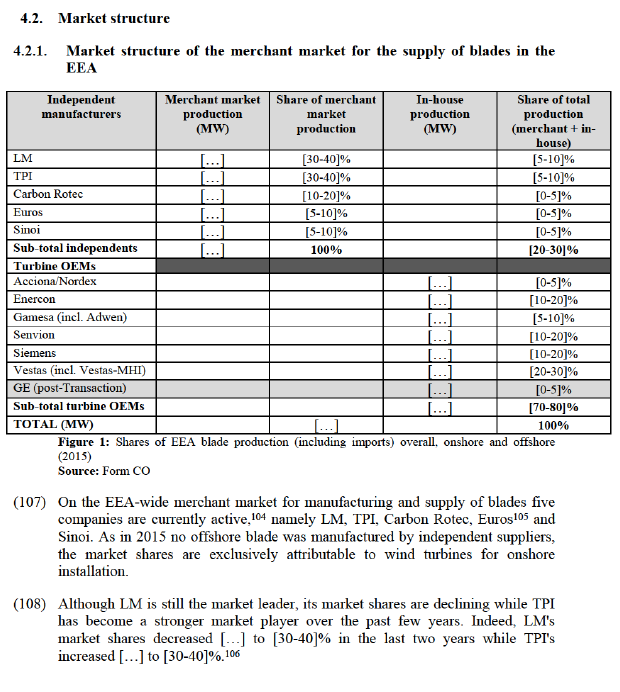

(61) The Notifying Party argues that, while the replacement of blades could constitute a distinct market from the repairing of blades, this aspect of market definition can be left open because it does not in any case affect the outcome of the competition analysis.

(62) The Notifying Party argues that the geographic scope of the market for blade servicing can be at an EEA level, or even a global level. (55)

(63) Finally, the Notifying Party submits that, due to the lack of overlap and, in any case, LM's low market share, the Transaction does not give rise to an affected market with respect to blade servicing.

Commission's assessment

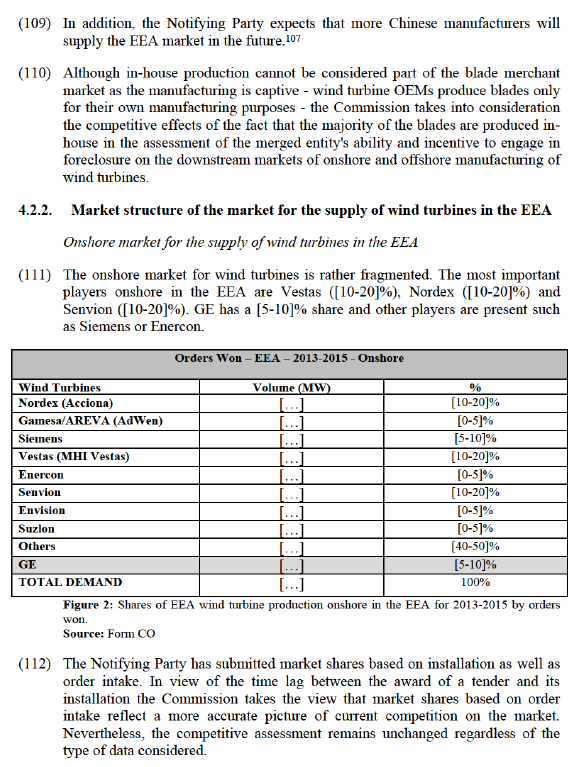

(64) Wind turbine blades are typically designed for a lifetime of approximately 20 years. Normally, during that time, minimal maintenance and repairs are requested for blades. (56) Replacement of blades may also occur, although very rarely (usually due to components failure or accidents).

(65) The market investigation suggested that independent service providers ("ISPs") can provide maintenance services for blades, but that blade replacement is more complicated. (57) In addition, the market investigation has confirmed that replacement of blades is far rarer than servicing, and may not ever take place during the lifetime of a wind turbine. (58)

(66) LM provides servicing and eventual replacement for its own blades but does not compete for after-sales service contracts for blades. (59) In 2015, LM's annual revenues from O&M services for blades amounted to less than […]% of its turnover. (60) Accordingly, its estimated market share is [0-5]%. (61) LM is contractually bound to supply these services with regard to its own blades.

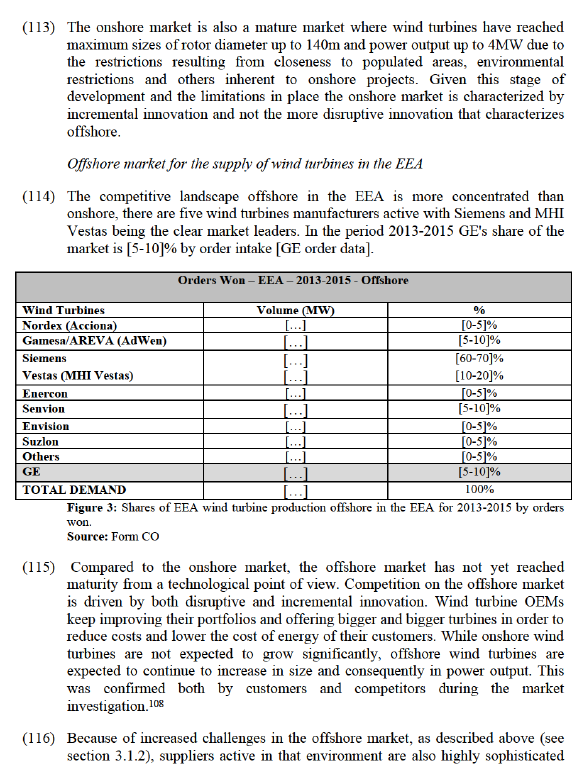

(67) With respect to the geographic market for blade servicing, the Commission has not in the past analysed wind turbine blade servicing. The market investigation demonstrated that various manufacturers and customers use a number of different models with respect to blade servicing (e.g., provided by blade manufacturer, provided by an independent service provider, provided in-house, etc.) (62) As noted in section 3.2.1 above, blade manufacturers located outside of the EEA may be a less attractive alternative to customers in the EEA. In addition, in the case of replacement, the same transportation considerations noted in section 3.2.1 for new blades would likely apply to replacement blades. As a result, the geographic scope of the market for blade servicing is likely not broader than the EEA.

(68) Having regard to the foregoing, the Commission leaves open the question of whether or not the replacement of blades and the provision of O&M services for blades constitute distinct markets, because the Commission's conclusions remain unchanged irrespective of the product market definition retained. In addition, the Commission leaves open the geographic scope of blade servicing because the Commission's conclusions remain unchanged irrespective of the geographic market definition retained. In any case, the Commission considers that the Parties do not overlap with respect to the replacement of blades and to the provision of O&M services for blades. Accordingly, the Commission considers that the Transaction does not result in one or more affected markets in this area and will not be analysed further.

3.3.2. Servicing of wind turbines

View of the Notifying Party

(69) The Notifying Party submits that GE and LM do not overlap with respect to the servicing of wind turbines. The Notifying Party does not provide a view with respect to the geographic scope of the market.

Commission's assessment

(70) Wind turbine OEMs typically provide operation and maintenance ("O&M") services for a turbine while it is under warranty, including blade servicing (63) which can be provided directly by the wind turbine OEM or subcontracted. (64) A turbine warranty generally ranges from two to five years, depending on the onshore or offshore market. (65) As noted in the previous section, GE does not provide blade servicing.

(71) Once a turbine is off warranty, the customer may then (i) choose to retain the OEM as the service provider, (ii) perform servicing in-house, or (iii) contract with an ISP such as Availon, Deutsch Windtechnik Service GmBH and Global Energy Service. (66)

(72) GE provides servicing of its own wind turbines but does not compete on the merchant market for servicing of wind turbines. LM does not provide wind turbine servicing.

(73) With respect to the geographic scope of servicing for onshore and offshore wind turbines, the market investigation demonstrated that at least part of the servicing aspect involves visual inspections, (67) which would therefore have to be done on site. In addition, as noted in section 3.2.1 above, it is important for offshore servicing to be done from a base close to the wind farm. Accordingly, the geographic scope of the market is likely no broader than the EEA.

(74) Having regard to the foregoing, the Commission considers that the Parties do not overlap with respect to the servicing of wind turbines. Accordingly, the Commission leaves open the product market definition and geographic scope of the market, and considers that the Transaction does not result in an affected market in this area and will not be analysed further.

4. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

4.1. Introduction: the wind industry

(75) The Transaction concerns the vertical integration of a wind turbine manufacturer, GE, with an upstream supplier of blades for wind turbines, LM.

(76) The wind turbine industry presents certain distinctive features that affect its competitive dynamics and therefore must be taken into account in the assessment of the effects of the proposed Transaction. The distinctive features relevant to this case concern in particular (i) the design, production process and sourcing possibilities; (ii) the certification requirements; and (iii) switching possibilities between blade suppliers.

4.1.1. Design, production process and sourcing possibilities

4.1.1.1. Design, production process and sourcing possibilities for blades

Design and manufacture of blades

(77) Blade production includes several stages, which can be summarised as follows: design and engineering, choice of materials, tooling and construction, prototyping and certification.

(78) Once a complete design is available, building a blade is a relatively straight- forward process that is nonetheless labour intensive and requires significant factory floor space.

(79) Blade construction typically follows a four stage process. First, the manufacturer builds or sources all prefabricated sub-components of the blade. Second, blade shells are created, by inserting the glass or carbon fibre blade material into the mould, installing the prefabricated components manufactured during stage one, infusing the resin into the fibre, and curing the resin in the fibre. Third, the internal structure of the blade is attached to the blade shell and the two blade shells are bonded together. Following a curing process, the blade is removed from the mould. Finally, the manufacturer trims, sands, and potentially paints the blade.

(80) After this process, mechanical components are further assembled and the blade is then weighted and balanced before being delivered to the customer. The cycle time for this four-step process is approximately one to two weeks.

Different types of blades

(81) The ownership of the intellectual property ("IP") rights attached to the design, build-to-print, build-to-spec and standard blades can be distinguished based on whether or not a blade is designed for a specific turbine.

(82) For the "build-to-print" model, the blade is typically custom-made to a design supplied by the OEM (the OEM either generates the design in-house or procures it from an independent design and engineering supplier). With the approval of the OEM, the blade manufacturer sources and installs the mould at a manufacturing location, produces a prototype and conducts testing in order to obtain blade component certification. The blade then goes into serial manufacturing. Under this model, the blade manufacturers develop and own the production process, but not the IP or the design for the blade itself or the tooling used, which are owned by the wind turbine OEM. The OEM hence can use the same design blueprint to manufacture blades with different blade manufacturers. (68)

(83) For the "build-to-spec" model, the OEM outsources the production to a manufacturer that also has design and engineering capabilities, and requests the manufacturer to design the blade according to specifications provided by the OEM (e.g. weight, length, power performance, geometry, load envelope). The manufacturer writes specifications and manufacturing work instructions, performs an internal qualification process and tests the blade as part of qualification and certification before proceeding with serial manufacturing of the blade. The OEM shares the turbine background IP rights with the blade manufacturer as the design process remains with the OEM, but any IP rights connected to the blade will usually remain with the blade manufacturer. An OEM wishing to source the same blade from a second manufacturer will therefore typically either need a license or need to procure a different design blueprint. (69)

(84) Another model is for the turbine manufacturer to use standard blades that are not designed specifically for its turbine model. (70) Standard blades are available to a large extent from various blade manufacturers. (71) LM estimates that around […]% of its blade sales are based on standard blades. (72)

In-house production vs outsourcing of blades

(85) The market investigation confirmed the Notifying Party's claim (73) that the majority of wind turbine manufacturers have in-house blade manufacturing capabilities. (74) In 2015, approximately [70-80]% of total blade production for the EEA was attributable to vertically integrated wind turbine OEMs: 100% of offshore blades and [70-80]% of onshore blades were produced in-house. (75) Indeed some wind turbine manufacturers produce all or almost all of their blades in-house. (76) GE is practically the last major turbine manufacturer without in-house blade production.

(86) Outsourcing some of the production allows wind turbine manufacturers to have more flexibility. Furthermore, a market participant suggested during the market investigation that turbine OEMs turn to independent blade suppliers also for their specific know-how and technological background. (77) Some OEMs follow a multi- sourcing strategy with regard to individual blade types. (78)

Manufacturing capacity for blades

(87) The market investigation showed that the market for manufacturing and supply of blades is not capacity constrained in the EEA. Indeed, the majority of customers indicated that the market is either balanced with regard to the supply and demand or that there is overcapacity. (79)

(88) Although manufacturing plants normally run close to full capacity, (80) capacity expansion does not seem to be problematic. Some major wind turbine OEMs and an independent blade supplier recently expanded their manufacturing capacity (81) and an independent blade manufacturer stated that "there is no major hurdle in building a new plant". (82)

(89) The cost of expanding an existing plant was estimated around EUR 5-15 million by a customer with in-house capabilities. (83) The expansion takes approximately 6- 9 months. (84)

(90) The cost of building a new plant is higher; it is estimated to be around EUR 20-50 million. The construction takes approximately 12-18 months. (85)

4.1.1.2. Sourcing of wind turbines

(91) Customers of wind turbines generally organise tenders in order to select the wind turbine to be installed in their projects, onshore or offshore. While the power rating of the turbine is not typically specified in the tender, they will select the turbine taking as a reference the lowest levelised cost of energy ("LCoE"), (86) together with other parameters such as reliability, experience and sound financials.

(92) Onshore, the selection is influenced by restriction on size or output of the wind farm due to the proximity of populated areas. As a result, some projects will allow for fewer larger turbines while others will have more turbines of a lower rating.

(93) Offshore, restrictions are generally on output, where projects are developed for a certain overall energy production, therefore bigger turbines allowing for more energy production with a smaller number of turbines installed are favoured.

4.1.2. Certification requirements

(94) After the final assembly, the newly designed blade has to be certified. First, the mould is qualified by laser inspection in order to verify that its dimensions are accurate. (87) Second, the blades themselves are certified, both independently (test blades) and mounted on a turbine (prototype blades).

(95) The test blades undergo structural testing including static and fatigue testing, as well as load testing. Furthermore, some wind turbine manufacturers such as GE subject one blade to cut-up testing, examining cross-sections to check the integrity of the product and the manufacturing process. (88) The structural test can be done by the blade manufacturer, the customer or by third party test centres. (89)

(96) The prototype blade set runs on a prototype turbine for 6-9 months in order to assess its performance. (90)

(97) After these tests, a "first piece qualification" set is manufactured and shipped to the customer to demonstrate that the blade manufacturer is able to produce a complete set of blades that meet all design and manufacturing criteria. (91) The blades can then be considered qualified by the wind turbine OEM, although the pilot lot qualification set – already used on commercialised turbines – produces additional data on the new blade design. (92)

(98) In addition, the newly designed blade is usually certified by third party agencies such as Technischer Überwachungsverein ("TÜV") or DNV GL Renewables Certification. These bodies test and certify the blades according to the IEC standards to ensure safety and reliability throughout the lifetime of the blade. The certification process takes place in parallel with the OEM qualification and applies to all blades regardless of the location of the manufacturing facility. (93)

(99) The Notifying Party claims that the qualification process described above typically takes around […] months and that, if the wind turbine and blade manufacturer have never worked together, the process can take slightly longer – approximately […]months. (94) In contrast, the market investigation indicated that the certification can take longer, up to 18-24 months. (95)

(100) As for existing blade designs the certification process is shorter. The Notifying Party estimates this to be no more than […] months when moving the production to another supplier and […]months for standard blades. (96) This was confirmed by an independent certifying agency, which stated that "if there is already a component certificate for standard blades, it is only necessary to go through minor steps, as controlling the interface, but the process is fast." (97)

(101) GE estimates the cost of blade qualification at around EUR […] for the wind turbine manufacturer (including, the supply of the test blades, testing, and transportation to the test centre) and approximately EUR […]-[…] for the blade manufacturer. (98)

(102) It should be noted however that the blades will be also assessed as a part of the type certificate of the whole turbine. (99)

4.1.3. Switching

(103) The time required to switch blade suppliers depends on the type of blade in question.

(104) For build-to-print blades, the IP and the tooling of which remain with the wind turbine manufacturers, the majority of customers confirmed the Notifying Party's claim (100) that switching is possible. (101) After switching, the blade has to be re- certified. However, as an independent certifying agency explained, "the new blade produced by a different "build-to-print" manufacturer, based on the exact same design, would only need an update of the relevant certification. For this it is only required to undergo the production assessment step with at least one inspection of the new manufacturing site." (102)

(105) For build-to-spec blades, switching is more difficult, as it is the blade manufacturer that owns the related IP rights and tooling. Therefore, switching entails either licensing or a completely new design. If a new design is developed, it has to undergo the qualification and certification process described above (see section 4.1.2). A market participant indicated that "the length of the process depends on the nature and extent of changes that must be made to the turbine as a result of the blade change, if any. For example, if the gear or drivetrain designs change following the blade change, or if the profile of the rotor or the weight and the loading of the turbine change, then the recertification process will likely take longer than if the new blade is virtually identical to the old one and/or if the turbine design is substantially the same. If the new blade is virtually identical to the old one and/or if the turbine design is substantially the same, the revised type certification can be issued in few weeks." (103)

(106) As discussed in section 4.1.2, the certification of a new standard blade is a rather straight-forward procedure, therefore switching can be done in a timely manner.

and tend to have a closer control of the whole supply chain. As a result, all offshore wind turbine suppliers manufacture blades for their offshore turbines in- house, with the exception of GE. Senvion and Adwen both have manufacturing capabilities in-house and manufactured their blades in-house. However Senvion currently has a serial production agreement with LM and Adwen has developed a blade with LM although no decision on serial production (in-house – on the basis of an alternative design - or outsourced to LM) has been made.

4.3. Input foreclosure

(117) According to the Commission's Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines (the "Guidelines"), (109) a merger may result in foreclosure where actual or potential rivals' access to supplies or markets is hampered or eliminated as a result of the merger, thereby reducing these companies' ability and incentive to compete. Such foreclosure is regarded as anticompetitive where, as a result of the merger, the merging companies, and possibly also some of its competitors, are able to profitably increase the price charged to consumers. When assessing the likelihood of such an anticompetitive input foreclosure scenario, the Commission examines whether the merged entity would have the ability post-merger to foreclose access to inputs, whether it would have the incentive to do so, and moreover, whether a foreclosure strategy would have a significant detrimental effect in the downstream market.

4.3.1. Ability

(118) The Guidelines enumerate factors giving the merged entity the ability to foreclose its downstream competitors: the existence of a significant degree of market power upstream, the importance of the input and the absence of timely and effective counter-strategies.

View of the Notifying Party

(119) The Notifying Party argues that the merged entity would not have a significant position in blade manufacturing, mainly because the majority of wind turbine OEMs are already vertically integrated and produce blades in-house. (110) Accordingly, the Notifying Party's position is that the merged entity will not have upstream market power.

(120) The Notifying Party further argues that alternative sources of supply (including in-sourcing) are available, and that wind turbine OEMs can switch to such alternatives in a timely and cost-efficient way. (111)

(121) Finally, the Notifying Party argues that wind turbine OEMs that source blades from LM have "effective and timely counter-strategies" to thwart attempted foreclosure by the merged entity post-Transaction. In particular, the Notifying Party highlights that long lead time between orders and deliveries of turbines allow wind turbine OEMs to "identify and fully develop a new source of supply before its ultimate sales [are] negatively affected". (112)

Commission's assessment

(122) LM appears to have limited market power upstream due to the prevalence of in- sourcing, relatively low market shares, and the presence of multiple competitors. Based on information provided by the Notifying Party, in 2015, [70-80]% of total blade production in the EEA for onshore use was conducted in-house by vertically integrated wind turbine OEMs. (113) The Notifying Party indicates that vertically integrated wind turbine manufacturers' in-house capacity is not used to supply competing wind turbine OEMs. (114)

(123) In 2015, LM produced [10-20]% of the blades for onshore wind turbines. (115) In terms of installed base, LM's share of the current installed base of onshore blades in the EEA is [10-20]%, excluding blades installed in GE wind turbines. In the same period, [LM's production volume] offshore blades, and […] 100% of the blades used offshore were produced in-house by vertically integrated wind turbine OEMs. (116)

(124) There are multiple competitors to LM on the upstream market for the manufacturing and supply of blades. Blade manufacturers with a manufacturing presence in the EEA include TPI, Carbon Rotec and Sinoi. Some of the major EEA blade manufacturers have confirmed that they either have additional available capacity or consider that it would not be difficult to cover additional demand for blades. (117)

(125) Nevertheless, the Commission considers that, for the purposes of this case, it is relevant to conduct an analysis for each downstream wind turbine OEM because, as described above in section 4.1.1.1, different blade sourcing processes (build-to- print, build-to-spec and standard blades) lead to different levels of control by the OEM over the rights necessary to effectively switch suppliers or to move production in-house.

(126) Post-Transaction, the merged entity's ability to foreclose competing wind turbine OEMs will depend on each OEM's in-house blade manufacturing capacity, sourcing strategy, relationship with LM and relationships with other blade manufacturers. The merged entity will have no ability to foreclose wind turbine OEMs with no blade supply relationship with LM. Wind turbine OEMs with a build-to-print or standard blade supply relationship with LM, but with a multi- sourcing strategy (either from other third party manufacturers or using in-house capacity), or a single-source, build-to-print strategy, would likely be able to counter any attempts at input foreclosure by the merged entity. Those wind turbine OEMs that single-source build-to-spec or standard blades from LM and have no in-house manufacturing capacity or other alternatives are likely dependent on LM for their blade supply, and the merged entity would likely have the ability to foreclose them post-Transaction. The competitive position of each wind turbine OEMs with regard to these elements will be analysed in turn.

4.3.1.1. Some wind turbine OEMs produce all their blades in-house or source from other suppliers than LM

Enercon

(127) Enercon indicated in the course of the market investigation that it already in- sources all of its blades and has no plans to outsource the supply of blades in the future. (118) Therefore, the Commission considers that the Transaction will not give the merged entity any ability to foreclose it on any affected market.

Vestas

(128) Vestas manufactures approximately two thirds of its blade requirements in-house. For the remaining requirements, it outsources to third party blade manufacturers. It currently has no blade sourcing relationship with LM. (119) Therefore, the Commission considers that the Transaction will not give the merged entity any ability to foreclose Vestas on any affected market.

4.3.1.2. Some wind turbine OEMs source partly, but are not dependent, from LM

Nordex

(129) Nordex sources a small part of its blade requirements from LM for use in the EEA. The blades sourced from LM are standard blades. The remaining blade requirements are met either by in-house production or by build-to-print blades from third party suppliers such as TPI, Carbon Rotec or Aeris. Nordex currently has a multi-sourcing strategy. (120)

(130) In the past, Nordex has expanded its blade manufacturing facilities multiple times to accommodate changes in blade design. In the course of the market investigation, it advised that such expansion generally takes place in parallel with the production of a new blade mould. Overall, it considers that it has sufficient capacity for its current turbine models and that expansion of facilities is "not a major issue". (121) As noted in section 4.1.3 above, switching to a standard blade from another third party blade manufacturer is not onerous based on the information obtained in the market investigation.

(131) In light of the above, the Commission considers that, because Nordex maintains a multi-sourcing strategy, and for the standard blades procured from LM it has proven alternatives such as in-house production to counter an attempt at foreclosure, the Transaction will not give the merged entity any ability to foreclose Nordex on any affected market.

Gamesa (122)

(132) Gamesa produces blades in-house, but also sources from third party blade manufacturers including LM. If LM were to stop production, Gamesa would retain ownership of the moulds, but would not own all of the IP rights to produce these blades in-house or outsource their production to another blade manufacturer. (123) Also, Gamesa indicated that it would take two to three years to switch production from LM to in-house facilities or third party suppliers. (124)

(133) However, Gamesa has a multi-sourcing strategy for each of its turbines. According to Gamesa, "[e]very Gamesa turbine has two type certificates, one with the LM blades design and another one with Gamesa's own design and then manufactured either in-house or by a third party."

(134) In light of the foregoing, the Commission considers that the Transaction will not give the merged entity the ability to foreclose Gamesa on any affected market.

Siemens

(135) Siemens manufactures the majority of its blades in-house. It has production capacity both within and outside the EEA. In the course of the market investigation, Siemens advised that it has the possibility of increasing capacity, including introducing more shifts, expanding an existing plant or building a new plant. In fact, Siemens is currently expanding a plant in China and building a new one in Morocco. It also has plans to build a plant in Egypt. (125)

(136) However, Siemens has also contracted with LM for blade supply. Siemens retains ownership of the mould, but LM owns the IP rights associated with the blade. As a result, "although Siemens owns the mould, it is not allowed to use it." (126)

(137) Siemens' contract with LM for the above-mentioned blade contains provisions that […]. (127)[…]. (128) [protect Siemens from the risk of foreclosure]. (129)

(138) In light of the foregoing, the Commission considers that the Transaction will not give the merged entity any ability to foreclose Siemens on any affected market.

4.3.1.3. Some wind turbine OEMs are dependent on LM for the supply of certain specific blades

Senvion

(139) In the course of the market investigation, Senvion indicated that it single-sources three blade models from LM for use in onshore turbines sold outside of the EEA. It further indicated that it sources 100% of its blade requirements for a fourth onshore turbine from LM, and that this blade is designed for and only used in this turbine. (130) Senvion is considering launching on the EEA market two of the three turbines for which LM supplies blades. These turbines are already certified for the EEA market. For all of the aforementioned blades, if post-Transaction the merged entity were to stop supplying Senvion, the latter would have the option to produce them in-house or to outsource their production to another supplier. In the past, Senvion has switched from outsourced supply with LM to in-house manufacturing. (131) To the extent that the designs are already certified, switching would likely be feasible in a timely and effective manner, as described in the results of the market investigation contained in section 4.1.3. Senvion also sources from LM a blade for an offshore turbine (6MW-126m). However, it has developed an in-house alternative to this blade and has also developed an in- house longer blade version for the same turbine (6MW-152m). (132) The Commission understand that this latter turbine is a more powerful version of the turbine that mounts the blades produced by LM. (133) As the market is moving towards bigger and more powerful turbines the Commission considers that this latter model would be more relevant for future serial installation. Also, the pending orders for LM blades are [details on orders]. (134)

(140) Senvion recently acquired Euros, a blade designer and manufacturer based in the EEA. It explained its rationale for the acquisition as seeking to benefit from Euros' research and development capacity and its capability to deliver moulds for blade production. (135) Therefore, while Senvion already has blade production capacity, it will increase such production capacity by acquiring Euros.

(141) The Commission considers that Senvion is currently dependent on LM for the supply of some blades for certain onshore turbine models. However, Senvion has proven its ability to switch to in-house supply in the past. In addition, Senvion has not raised a concern that attempted foreclosure by the merged entity would cause it to reconsider its product launch planning. Given that the relevant turbines are not currently sold in the EEA and that Senvion is vertically integrated with a recently-expanded in-house blade development and manufacturing capacity, (136) the Commission considers that the merged entity would have limited ability to foreclose Senvion on any affected market.

Adwen (137)

(142) Adwen, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gamesa, offers two offshore wind turbines in the EEA: the AD5-135 with power output of 5MW and rotor diameter of 135, and the AD8-180, with 8MW power output and 180m rotor diameter.

(143) Adwen currently in-sources the blades for its 5MW offshore turbine, which is the only model of turbine that is currently under serial production. However, it has agreed to a supply arrangement with LM for the supply of a mould and a prototype blade set for its upcoming 8MW offshore turbine. (138)

(144) While it also has an internal design for a blade for this turbine, it cannot substitute the internally designed blade for LM's blade in those current projects for which it is bidding or has won and that have installation dates that are within a short period of time, because this would cause delays to these projects. (139) In the course of the market investigation, Adwen indicated that it does not have the manufacturing capacity for this type of blade and there are no alternative independent suppliers that could manufacture it.

(145) Accordingly, the Commission considers that Adwen in the short run will be dependent on LM for the supply of blades for its 8MW turbine, and has no timely or effective counter-strategy to prevent the merged entity from engaging in foreclosure post-Transaction. As a result, the Commission considers that the merged entity will have the ability to foreclose Adwen post-Transaction with respect to the supply of blades for its 8MW offshore wind turbine.

(146) In the course of the market investigation, Adwen indicated that it is still negotiating the terms of its supply agreement with LM. As a result, it raised the concern that, post-Transaction, it may obtain less favourable commercial terms. It also raised the concern that the facility in which the blades will be produced could be subject to unfair capacity allocation practices by the merged entity, and that GE – a downstream competitor – may have access to its commercially sensitive business information. (140)

(147) The Notifying Party informed the Commission that LM [details on commercial relationship with Adwen]. (141) (142)

(148) Having regard to the foregoing, the Commission considers that the merged entity will have an incentive to [continue commercial relationship with Adwen]. Furthermore, the Commission considers that LM [has demonstrated] its continued willingness to supply blades to Adwen post-Transaction, and […] support this position. However, as to the merged entity's ability to foreclose Adwen, it is to be emphasised that [it is not entirely eliminated].

(149) In light of the above, the Commission considers that LM would have the ability to foreclose Adwen post-Transaction until […].

Smaller customers

(150) There are a number of small onshore wind turbine manufacturers that have no in- house blade manufacturing or design capacity and that rely solely on LM for blades. These customers of LM procure standard blade models. One of them indicated during the market investigation that LM owns both the mould and the IP for these blades. (143)

(151) At least one of these customers considers that it has no alternatives to blade supply from LM. It considers that "[m]anufacturing rotor blades is extremely expensive" and that it "does not have the resources to manufacture own blades." (144) In any case, it replied during the market investigation that, even if it were to consider manufacturing blades, there were a number of elements (equipment and know-how) that it would have to acquire in order to develop any in-house blade manufacturing capability. (145)

(152) One smaller turbine manufacturer considers that it would take 2 years to certify its turbines with a new blade should LM stop supplying it. (146) However, the Commission's market investigation indicated shorter timelines for switching to another standard blade from another manufacturer, as described in section 4.1.3 above.

(153) One small turbine manufacturer summarized as follows its dependence on LM: "[they] are fully depending on LM because there in-house experience and ability to make blades as a standard product based on LM designs. It is very difficult for relative small turbine EOM to compete with big players when they need to make and prodcue there own blade technology." (147)

(154) In light of the foregoing, the Commission considers that smaller turbine manufacturers that procure standard blades from LM and that have no in-house blade manufacturing capacity are currently dependent on LM for the supply of blades. As a result, the Commission considers that the merged entity likely will have the ability to foreclose these types of smaller customers post-Transaction.

Conclusion on ability

(155) Based on the reasoning above, the Commission considers that the merged entity would not have the ability to foreclose Enercon, Vestas, Nordex, Siemens and Gamesa.

(156) The merged entity would only have some ability to foreclose Senvion in relation to certain specific onshore blades and it would likely have the ability to foreclose Adwen's 8MW offshore turbine at least in the short term. In addition, the merged entity would have the ability to foreclose smaller customers that rely solely on LM for standard blades.

4.3.2. Incentives

(157) According to the Guidelines the assessment of the merged entity's incentive to foreclose its downstream competitors requires the analysis of the overall profitability of the input foreclosure strategy. This analysis considers the profits that the merged entity obtains upstream and downstream, the extent to which downstream demand can be diverted from the foreclosed competitors to the merged entity and the extent to which the merged entity might benefit from the higher downstream prices that result from the strategy to raise rivals' costs.

4.3.2.1. Onshore

View of the Notifying Party

(158) The Notifying Party submits that the merged entity would have no incentive to foreclose its downstream competitors post-merger in the onshore market.

(159) The Notifying Party argues that the documents analysing the synergies expected from the Transaction show that losing current LM customers would lead to [amount estimate] margin losses on blades. The Notifying Party further argues that it could only partly mitigate these losses by insourcing to LM [amount estimate] of GE's blades requirement currently sourced from third parties. However, this insourcing would free up capacity with the other independent blade manufacturers to the benefit of GE's downstream competitors, which would effectively undermine the attempt to foreclose them. (148)

(160) The Notifying Party also submitted an assessment on the incentive to foreclose based on the profitability analysis of a hypothetical foreclosure strategy. This analysis compares the (lost) margins realized on the upstream sales of blades to the (gained) margin realized on the downstream sales of turbine recaptured from rivals, taking into account the estimated proportion of rivals' sales the merged entity could expect to recapture. (149)

(161) The Notifying Party estimates that the downstream unitary margin obtained from the sale of a wind turbine is about [higher] the unitary margin obtained from the sale of a blade set. Since each turbine corresponds to a single blade set, this implies that, for every percentage point of upstream onshore market share forgone by the merged entity due to reduced blade supply, it would need to recapture more than […]percentage points of downstream share to offset the lost upstream margin. Hence, the foreclosure strategy would be profitable only if the merged entity could recapture more than […]% of the sales lost by its rivals. (150)

(162) According to the Notifying Party, this recapture rate likely would not be achievable given that: i) only [0-20]% of turbines sold downstream have LM blades installed (implying that [80-100]% of the EEA onshore market would not be affected by the possible foreclosure strategy); and ii) that the downstream market share of GE's onshore turbines in the EEA amounts to [10-20]% in 2016 and [5-10]% in 2015 (in terms of orders won). Hence, the Notifying Party considers that any possible foreclosure strategy would rather lead to an advantage for the EEA onshore market leaders. (151)

(163) Further, the Notifying Party also argues that the possible foreclosure strategy, even in the case of complete input foreclosure, would not have a material impact on downstream prices given the small share of affected sales. Hence, downstream prices, and consequently margins for the merged entity, are not expected to significantly differ from the current margins. Rather, prices [have declined] in the recent years (when downstream turbine prices have recently seen a year on year […]% decline). (152)

(164) Finally, the Notifying Party notes that its profitability analysis does not consider the impact of the long term contracts in place, the penalties and damages that the merged entity would incur if it failed to deliver and the minimum service revenue related to the sale of blades. All these elements, if taken into consideration, would further increase the losses of a possible foreclosure attempt. (153)

The Commission's assessment

(165) The Commission has reviewed the internal documents and the analysis submitted by the Notifying Party, the evidence collected in the market investigation and has further conducted its own analysis.

(166) On this basis, the Commission considers that the Notifying Party has sufficiently demonstrated that any losses arising from a possible strategy of input foreclosure would likely outweigh the gains that the merged entity might expect from this strategy. This holds for the current competitive scenario and for the scenario that could be expected to prevail in the following years after the Transaction. The Commission also notes that this analysis is consistent with the evidence found in the GE and LM's internal documents. (154) This evidence shows that: i) [GE analysis of potential effects]. These elements support the view that input foreclosure would not be profitable for the merged entity.

(167) Further, the Commission notes that, in the market investigation, a number of players have indicated that the merged entity might have the ability to foreclose its rivals. However, the respondents that have substantiated their claims mostly argue that the merged entity would not have the incentive to put in place such a foreclosure strategy: "we believe there is no incentive for the combined entity to stop supplies as the effect of such stoppage will be rather limited" (155); "considering the purchase price of LM known publicly, and taking into account the manufacturing capacities of LM, which go beyond the assumed need of GE, it would be commercially not recommendable". (156) In contrast, another customer argued that the merged entity would have both the ability and the incentive to foreclose rivals. (157)

(168) In light of the collected evidence, the Commission considers that the downstream onshore market is highly fragmented and that the current larger market players, Vestas, Senvion, Nordex/Acciona, Siemens/Gamesa, Enercon, are mostly larger than GE (both in terms of installed capacity and orders won) and either do not purchase from LM or purchase only a limited share of their blades requirement from LM.

(169) The Commission’s analysis shows that the merged entity could have the ability to foreclose only Senvion (partly) and some other smaller players in the offshore market (section 4.3.1.3). These sales would represent less than [0-5]% of the onshore market. (158) The merged entity could theoretically stop supplying its downstream competitors that are partially or totally dependent or raise their costs for blades. However, the Commission considers that the upstream losses associated to this strategy would likely outweigh any benefits that the merged entity would obtain downstream by increasing its sales of onshore wind turbine. This is because GE would still face the strong competition of the many rivals that are not dependent on LM and the merged entity could expect to recapture only a fraction of its foreclosed sales such that the expected gain downstream would likely be lower than the expected upstream losses.

(170) In its assessment, the Commission concludes that, given the relative weak position of GE in the downstream market (and hence only a limited likelihood to recapture the foreclosed sales), the size of the affected sales and the upstream and downstream margins, even if the merged entity would have the ability to foreclose some of its customers in the onshore market, as described in section 4.3.1.3, it is unlikely that the merged entity will have the incentive to pursue a complete or partial foreclose strategy.

4.3.2.2. Offshore

View of the Notifying Party

(171) The Notifying Party submits that the merged entity would have no incentive to foreclose its downstream competitors post-merger in the offshore market. (159)

(172) Other than sales to GE, LM has limited activities in the supply of offshore blades: it currently supplies a number of blades to Senvion ([details on customer relationship]), and is engaged in a blade development program for Adwen’s new 8MW turbine, [details on customer relationship].

(173) The Notifying Party submitted an assessment on the incentive to foreclose based on the profitability analysis of a hypothetical foreclosure strategy in the offshore market. This analysis applied the same approach to the offshore market as the one described in section 4.3.2.1 above. (160)

(174) The Notifying Party estimates that the downstream unitary margin obtained from the sale of an offshore wind turbine is about [higher] the unitary margin obtained from the sale of an offshore blade set. Since each turbine corresponds to a single blade set, this implies that, for every percentage point of upstream offshore market share forgone by the merged entity due to reduced blade supply, it would need to recapture more than […]percentage points of downstream share to offset the lost upstream margin. Hence, the foreclosure strategy would be profitable only if the merged entity could recapture more than […]% of the offshore sales lost by its rivals. (161)

(175) According to the Notifying Party, this recapture rate likely would not be achievable given the limited role played by GE in the offshore sector, where it has yet to make its first installation and where, in the past few years, it won [details on projects]. This [details on projects] gave GE a 2015 market share of […]% in terms of orders won, but the Notifying Party argues that the position of GE has […]. (162)

(176) […]. (163)

(177) […]. (164) […]. (165) […]. (166) […]. (167)

Commission's assessment

(178) To assess the incentive for the merged entity to engage in input foreclosure, the Commission has reviewed the analysis and documents submitted by the Notifying Party and the evidence collected in the market investigation, and has further conducted its own analysis.

(179) On the basis of its assessment, the Commission considers that any losses arising from a possible strategy of input foreclosure would likely outweigh the gains that the merged entity might expect from this strategy.

(180) At the outset, the Commission notes that any possible foreclosure concerns arising in the offshore market might be related only to Adwen with respect to its 8MW turbine. As discussed in the assessment of the ability to foreclose (section 4.3.1), Adwen is […]currently developing a blade with LM for future installation. Senvion also purchases a blade for offshore installations from LM; however, Senvion can also produce in-house a longer version of this blade for installation in the same turbine, (168) hence the Commission considers that Senvion has a viable alternative to the blades sourced by LM.

(181) The Commission also notes that Adwen is the only wind turbine OEM involved in the offshore market that has expressed foreclosure concerns with respect to the Transaction. In particular, Adwen claims, in general, that the merged entity will have the incentive to limit the access of its competitors to LM. In addition, Adwen claims that the merged entity would have the "incentive to stop providing blades for its 8MW turbine in order to prevent Adwen from offering a competitive product." Also Adwen claims that "there would be an incentive for GE not to supply Adwen, as that will imply a delay of at least 2 years in the introduction of its turbine. Such a delay in the development of the 8MW turbine will eliminate Adwen’s product as a potential competitor in the offshore market." (169)

(182) In consideration of the above, the Commission considers that the assessment of the incentive to foreclose should be focused on Adwen - the only offshore supplier for which the merged entity has the ability to foreclose.

(183) In this respect, the Commission notes that the profitability assessment submitted by the Parties to demonstrate that there is no incentive to foreclose in the offshore market is irrelevant for the required assessment. The analysis submitted by the Notifying Party is indeed based only on a limited set of data. In particular, the upstream margin computed for the sales of LM are based [details on method of calculation of margin]. The Commission considers that this margin is not representative of the margin that LM would forego from foreclosing Adwen.

(184) To assess the incentives of the merged entity to foreclose Adwen, the Commission considers the profitability of a possible foreclosure strategy targeted on Adwen.

(185) In terms of the profitability of the upstream sales, the Commission notes that Adwen has secured a significant pipeline of about 1.5 GW that will be installed in France starting in 2021. (170) The Commission considers that, although these projects have not yet reached the notice to proceed stage, they are not contestable and GE could not recapture these sales if it were to foreclose Adwen. According to the estimates submitted, LM expects to obtain a total margin of EUR […] (171) by delivering blades to Adwen for these projects. On this basis, the Commission is of the view that if the merged entity were to implement a foreclosure strategy targeting Adwen, it would lose a significant amount of profits in relation to the Adwen French pipeline and would obtain no or very limited possible gains from this strategy.

(186) With respect to the possible incentive to foreclose Adwen on the open tenders (the tenders in which the turbine supplier has not yet been selected), the Commission, in the following, assesses GE's expected recapture rate for the foreclosed sales. This assessment considers the competitive interaction between GE's and Adwen's offshore products.

(187) With respect to the product offering, the Commission notes that GE's and Adwen's products overlap only to a limited extent. GE has been offering in the market its 6MW turbine for which it was able to secure [details on projects]. Adwen, beyond its 5MW platform that is considered outdated, (172) only has an 8MW platform with which it currently bids. The Commission observes that these two products have been competing in the past and that GE was able to win business against Adwen. However, Adwen reported only a single instance when it was asked to comment on the tenders in which it faced GE: "GE Alstom has won against Adwen’s 8MW turbine in the Merkur project. This shows that GE Alstom 6MW turbine, which has been already tested, is competitive against a mere untested project of Adwen’s 8MW". (173)

(188) Despite this limited overlap, the Commission considers that [competitive outlook]. The customers (as explained in section 4.1.1.2) are demanding platforms that can deliver increasingly lower LCoE and currently there are three suppliers marketing 8-9MW platforms, namely MHI Vestas, Siemens and Adwen. This is [bidding strategy]. (174) Also, with respect to […], the Commission considers that Adwen is not participating in the bidding, hence no foreclosure concerns can arise in relation to […]. (175)

(189) In light of the above, the Commission considers that the merged entity will have no incentive to foreclose Adwen with respect to GE's 6MW platform.

(190) Beyond its 6MW platform, GE has no platform in the 8-9MW space […]. This was also confirmed by the review of the internal documents submitted by the Notifying Party, where […]. (176) As discussed in paragraph […]. (177)

(191) […] The Notifying Party argues that [some of its competitors] are currently working on larger turbines. (178) [Adwen] expresses its concerns about the installation window available for its 8MW turbine: "The market opportunity window for 8MW turbines is short. Adwen is aware that some of its competitors are already working on 10MW platforms. Once these platforms will be on the market the 8MW turbines will no longer be competitive." (179)

(192) […].(180) […].