Commission, October 7, 2016, No M.7930

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Judgment

ABP GROUP / FANE VALLEY GROUP / SLANEY FOODS

Dear Sir/Madam,

Subject: Case M.7930 - ABP Group/Fane Valley Group/Slaney Foods Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/2004 (1) and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (2)

(1) On 2 September 2016, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (3) by which ABP Food Group ("ABP", Ireland), through a series of interrelated transactions, acquires joint control – within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation – over Slaney Foods Joint Venture (“Slaney JV”, Ireland) and Slaney Proteins, together with Fane Valley Co-operative Society Limited (“Fane Valley”, UK) (the “Transaction”). (4) ABP and Fane Valley are hereafter collectively referred to as the “Notifying Parties”. The Notifying Parties and the Slaney JV are collectively referred to as the “Parties”.

1. THE PARTIES

(2) Fane Valley is a farmer-owned co-operative active in a variety of agribusiness sectors. Its activities include the slaughter and processing of beef and lamb in Northern Ireland and the UK via Linden Foods Limited (“Linden Foods”), over which it exercises sole control. (5) On the Island of Ireland ("IoI", comprising Northern Ireland ("NI") and Republic of Ireland ("the RoI"), Fane Valley has one plant located in NI processing beef and lamb.

(3) ABP is an agribusiness company. Its subsidiaries are active in meat processing, supplying a range of chilled, frozen and other meat products to retail, wholesale and foodservices markets worldwide. ABP is also active in pet food, renewable energy and proteins. On the IoI, ABP operates eight meat processing plants.

(4) The Slaney JV is currently a 50:50 JV between Fane Valley and Lanber Group (a non-affiliated, third party company). The Slaney JV comprises Slaney Foods International ("SFI", its cattle slaughter and beef meat business, located in the RoI) and Irish Country Meats ("ICM", the sheep and lamb slaughter and mutton and lamb meat business, with operating sites located in the RoI and Liège in Belgium). Slaney operates three meat processing plants on the IoI, one of which slaughters beef and two of which slaughter sheep and lamb. ICM also purchases lamb carcasses for further processing.

(5) Slaney Proteins is currently 100% owned and controlled by Lanber Group. Slaney Proteins operates a small Category 3 rendering facility which primarily processes Category 3 material generated by the Slaney JV.

2. THE OPERATION

(6) On 22 January 2016, ABP, Fane Valley, the Allen Family (which controls the Lanber Group) and Slaney JV entered into several agreements, whereby ABP acquires a 50% controlling interest in the Slaney JV through a series of interrelated and simultaneous transactions and whereby the Allen Family exits the JV. To this end, ABP will subscribe to as many new shares issued by the holding company of the Slaney JV – Slabridge Holdings Limited ("Slabridge") – as currently held by each of the Allen Family and Fane Valley so that each of ABP, Fane Valley and the Allen Family will temporarily hold a third of the then total shares. On the same day, Slabridge will redeem all shares of the Allen Family which will result in Fane Valley and ABP each holding a 50% interest in the Slaney JV.

(7) The transactions described in the paragraph above are linked de jure, would not take place one without the other, and will be carried out at the same time with the aim of achieving a single unitary outcome in accordance with the ultimate economic aim of the Parties, that is, the acquisition of joint control of the Slaney JV by ABP and Fane Valley. Given the unitary nature of these transactions, their inter-conditionality and the fact that they will be carried simultaneously, these transactions, resulting in the acquisition of a joint controlling interest of ABP in the Slaney JV, are interrelated and interdependent thus constituting a single concentration in accordance with paragraph 38 of the Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice.

(8) In addition, at the same time and conditioned upon the acquisition of joint control of the Slaney JV by ABP, the Slaney JV will acquire via Slaney Foods indirect control over 100% of Slaney Proteins so that as a result of the Transaction Slaney Proteins will be jointly controlled by Fane Valley and ABP.

(9) Therefore, as a result of the Transaction, ABP will replace the Lanber Group as a shareholder in the Slaney JV and will, thereby, acquire joint control over the Slaney JV together with Fane Valley. Moreover, ABP and Fane Valley will, via the Slaney JV, also acquire joint control over Slaney Proteins.

(10) […].

(11) The Slaney JV is, and will continue to be, a full-function joint venture. The Slaney JV has sufficient resources to operate independently on the market. Both businesses of the Slaney JV, SFI and ICM, have their own day-to-day management, own assets, own capital and employ their own employees. The Slaney JV has not/will not take over specific functions for its parents but is rather an established business with its own market presence, operating on a lasting basis. Therefore, the Slaney JV is full-function.

3. EU DIMENSION

(12) The combined aggregate worldwide turnover of ABP, Fane Valley and Slaney JV exceeds EUR 2 500 million. The combined aggregate turnover of all these undertakings is more than EUR 100 million in France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK. In these Member States, the aggregate turnover of each of at least two of these undertakings exceeds EUR 25 million in France, Ireland, the Netherlands and the UK. Overall, the aggregate EU-wide turnover of the Parties exceeds EUR 100 million. Slaney JV achieves less than two-thirds of its turnover in the UK.

(13) The notified operation therefore has an EU dimension according to Article 1(3) of the Merger Regulation.

4. RELEVANT MARKETS

4.1. Introduction – The activities of the parties and general characteristics of the markets to which the Transaction relates

4.1.1. The activities of the Notifying Parties

(14) Fane Valley is a farmer-owned co-operative active in a variety of agribusiness sectors. Its activities include the slaughter and processing of beef and lamb in NI and the UK via Linden Foods Limited (“Linden Foods”), over which it exercises sole control. On the IoI, Fane Valley has one plant located in NI processing beef and lamb. Linden, which is controlled by Fane Valley, slaughters and processes beef and lamb from two primal processing locations, one in Dungannon, NI and the second in Burradon, England.

(15) ABP has 37 manufacturing plants in Ireland, UK, Denmark, Poland, Austria, Holland and Spain. It sells its products throughout the EU and further afield. ABP is a beef processor in Ireland, Poland and the UK. ABP Ireland specialises in beef processing, de-boning and retail packing. It operates factories supplying quality beef to European and worldwide retail and wholesale markets. ABP UK is a supplier of fresh and frozen meat and meat-free products. ABP Poland exports beef throughout Europe. In the IoI, ABP operates eight meat processing plants, six of which are located in the RoI and two in NI. In addition, ABP operates two rendering plants in the the IoI.

(16) The Slaney JV has two divisions. SFI is the beef division which is a beef processor, with a plant in Co. Wexford, RoI. Irish Country Meats is the sheep division, which operates two plants, one in Navan, Co. Meath, RoI and the other in Camolin, Co. Wexford, RoI. ICM’s Lonhienne business in Liege Belgium purchases lamb carcasses and lamb primals for further processing. The end products are marketed across a range of wholesale and retail customers, predominantly in Belgium. The Slaney JV operates three meat processing plants in the above-mentioned locations on the IoI.

(17) Slaney Proteins is currently 100% owned and controlled by Lanber Group. Slaney Proteins operates a small Category 3 rendering facility which primarily processes Category 3 material generated by the Slaney JV.

4.1.2. The beef, lamb and sheep meat production process

(18) The activities of Parties overlap in the slaughtering of live animals (cattle, lamb and sheep), and the processing (“de-boning”) of carcasses to produce fresh beef, fresh lamb and processed meat for sale to retail (supermarkets and butchers), caterers and industrial processors. (The competitive analysis of the impact of the Transaction on these markets is outlined in Section 5 below). The Parties' activities also overlap in the supply of Category 3 fats and Category 3 processed animal proteins. This overlap is not discussed at length in this Decision for the reasons explained in paragraph (192) below. Finally, vertically, ABP and the Slaney JV overlap in the collection and processing of Category 1, Category 2 and Category 3 animal by- products. (6) (The competitive analysis of the impact of the Transaction in these markets is in Section 6 below).

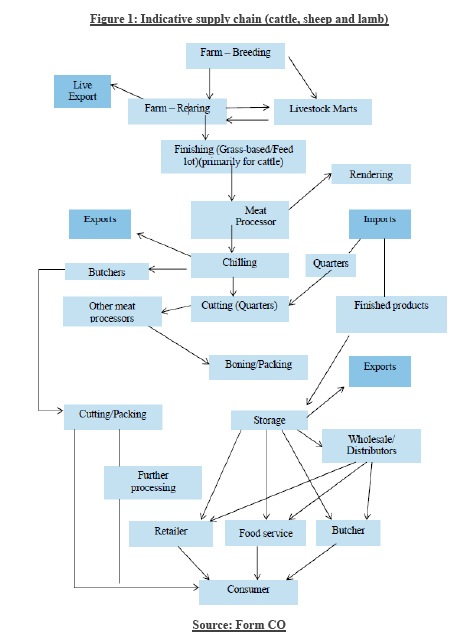

(19) Figure 1 below, as submitted by the Notifying Parties, portrays the supply chain process for beef, sheep and lamb.

(20) Approximately 85-90% of the total cattle produced (i.e. born and reared) in the RoI are slaughtered in the RoI (i.e., approximately 1.5m heads of cattle). The remaining approximately 10-15% of cattle produced (i.e. born and reared) in the RoI are exported live.

(21) The Notifying Parties explain that the typical chain for production of beef meat and cattle by-products in the RoI is as follows.

(22) The process begins with farmers who maintain a breeding herd of cows that nurture calves every year. Cattle are bred and brought to an abattoir/slaughterhouse for slaughter. The carcass is then "de-boned" to produce cuts of beef as well as other material such as offal (so called "by-products").

(23) De-boning may take place at the same processing plant where cattle are slaughtered, if the plant is vertically integrated, or at another processor's plant or at a separate boning hall which does not slaughter cattle.

(24) Cuts of beef are sent to manufacturers of beef products for further processing, or are further processed into smaller cuts appropriate for catering or retail sale. Retail cuts may be prepared in-store at downstream levels (for example in a butcher's shop) or by the primary processor, or by an intermediary on behalf of a retailer. The final step in beef production is when beef is shipped and sold in the RoI and abroad.

(25) Cattle by-product materials are the remains of an animal after meat has been removed for human consumption. Some cattle by-products can be used for non- human food uses, such as for pet food and leather, the remainder would then need to be disposed of. "Rendering" refers to the rendering of animal by-product materials through a process of heat and pressure treatment to produce fats as well as proteins (i.e. protein products resulting from the extraction of fat and moisture from the raw material) and tallow.

(26) Some animal by-product material is classed as high risk, and this material is rendered through approved processes and/or destroyed through incineration. Accordingly, cattle by-products are defined as Categories 1, 2 and 3 materials, according to their risk, and the different categories are required to be treated differently at all stages.

(27) The typical chain of production of lamb and sheep meat in the RoI is similar to that of beef meat. Lamb and sheep production begins with farmers who maintain a breeding flock.

(28) Sheep are kept on farm for breeding and production of lambs in the following season. They generally live for 6 or 7 years before slaughter at the end of their reproductive or economic life. Approximately 20% of the breeding ewes are slaughtered each season. Each ewe produces on average 1.7 lambs per season.

(29) Lamb and sheep are brought from the farm to a slaughter house, their carcass is de- boned, and cuts of lamb and sheep, such as legs, shoulders, chops, racks etc. are sent to manufacturers of lamb and sheep products for further processing, as is the case with cattle. The final step in meat production is when lamb and sheep meat is shipped and sold in the RoI and abroad.

(30) The parts of a sheep/lamb carcass that can be used for by-products are usually segregated during slaughter and include offal (liver, kidney, heart), intestines (castings), stomach, lungs, heads, hooves, manure, fats and skins. While some lamb and sheep by-products can be used for non-human food uses, those that remain need to be disposed of. As with cattle, Categories 1, 2 and 3, according to their risk, require to be treated differently at all stages (e.g. Category 1 materials such as spleen and ileum (part of the small intestine) of all animals; and the skull (including the brain and eyes), spinal cord and tonsils of animals aged over 12 months.

4.1.3. Procurement of live animals (cattle, lamb and sheep)

4.1.3.1. Source of supply of live animals

(31) As the Notifying Parties explain, farmers are the source of the vast majority (90- 95%) of all cattle purchased by slaughterhouses in the RoI. ABP, the Slaney JV and Linden purchased 98% of lamb and sheep from independent farmers. Slaughterhouses purchase live animals directly from farmers, sometimes with an agent facilitating the transaction. Slaughterhouses typically have procurement teams which buy cattle directly from farmers who seek price quotes. The Notifying Parties submit that there are no written contracts between farmers and slaughterhouses. The purchase and sale of live animals is a spot business and prices can change daily.

(32) Producer groups are also active in the RoI. A producer group is a collection of individual farmers who sell live animals individually but have collectively agreed a bonus with a slaughterhouse. The individual supplier forecasts the amount of cattle, for instance, that he intends to supply per month for the coming year and in return the slaughterhouse agrees to pay a bonus for the cattle supplied […]. The individual farmers within a producer group are not contractually bound to sell to the slaughterhouse on the terms and conditions agreed, and negotiations are largely the same as with individual farmers.

(33) Agents act as the middle men in the supply chain. Agents are paid a fee by the slaughterhouse, usually on a per head basis. They perform the same function as procurement staff within slaughterhouses but on a self-employed basis. They assist farmers and slaughterhouses to reach an agreed price. Agents do not take ownership of /are not suppliers of live animals. (7) Agents may also arrange the transport between the farm and slaughterhouse. Some agents work exclusively for one slaughterhouse while others work for multiple slaughterhouses. No training is required for agents, according to the Notifying Parties. (8)

(34) The Notifying Parties submit that all cattle supplied to ABP and the Slaney JV are supplied by independent farmers. (9) ABP deals with one producer group in relation to cattle […] which supplied […] cattle in 2015 or [0-5]% of ABP's total supply. The Slaney JV does not deal with any producer groups in relation to cattle. In relation to lamb and sheep, ABP deals with no producer groups.

(35) In relation to agents, the Slaney JV has a total of […] agents, […] of which serve the Slaney JV's plant on an exclusive basis and […] of those […] supply […] cattle per week. (10) ABP has a total of […] agents, […] of which are exclusive. According to the Parties, the number of agents for ABP and Slaney JV has been largely consistent over the last 3 years and it is expected to remain the same post Transaction. There are no plans to reduce or rationalise the number of agents. (11) ABP does not use agents when purchasing sheep or lamb. Slaney JV via ICM uses the services of agents for procurement of lamb and sheep. Payments to agents are based on a per head basis for numbers supplied. (12)

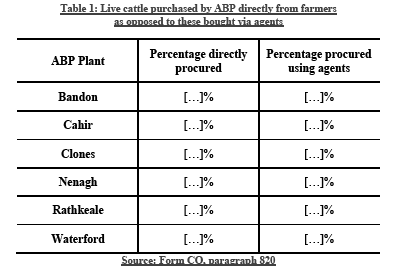

(36) The Notifying Parties submit that […]% of ABP’s cattle are procured with the assistance of cattle agents. The remaining […]% are purchased and negotiated directly with individual suppliers. Approximately […]% of cattle purchased by the Slaney JV are purchased directly from individual farmers with the assistance of these self-employed cattle agents. The remaining […]% are purchased by the Slaney JV directly from farmers by procurement staff (buyers) who are full time employees in the Slaney JV. (13) In relation to ABP, the percentages per plant are set out in Table 1 below.

4.1.3.2. Negotiation on prices and price transparency

(37) The negotiation process between the supplier and the slaughterhouse is typically initiated by the farmer. A slaughterhouse would rarely turn away cattle, lamb or sheep once price can be agreed. Negotiations typically take place over the phone.

(38) Farmers will routinely call the slaughterhouse and enquire about the base price. Based on this information the farmer may decide to feed the cattle for another week or send them to slaughter. As regards the time window in which lamb and sheep have to be sold to slaughterhouses, these can be slaughtered every day of the year and there is no short time window within which they must be slaughtered. Farmers can negotiate prices with a number of plants for each sale. A farmer may reference a nearby competitor factory that is offering a higher price and negotiate on that basis. Farmers would also check prices being offered to their neighbouring farmers with those farmers to ensure that the Slaney JV's prices are competitive. The process usually takes a few hours where a decision is made by the slaughterhouse to procure or not at the price and the farmer to supply or not.

(39) There is a significant level of price transparency within the market and this is used by farmers to strike the best bargain with the processors for their live animals. As outlined in the Form CO, slaughterhouses are obliged to report their volumes and prices to the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine ("DAFM") on a weekly basis, which in turn is reported to the European Commission. This information is published and is publicly available. Bord Bia (14) also publishes live animal prices on its website on a weekly basis. The agri-press publishes quotes by factory for the current week (e.g. the Farmer’s Journal and the farming section of the Irish Independent and a web site called Agriland) and these may be updated more regularly on their websites. In addition, farmer representative organisations, such as the Irish Farmers' Association (IFA), publish the up to date quotes every other day on their website and these are also available through social media, the iFarm Information app and a number of other apps. (15)

4.1.3.3. Pricing of live animals for slaughter

(40) According to the Parties, ABP sets its base price and will negotiate bonuses with suppliers depending on supply and demand. [ABP Pricing Description]. (16)

(41) [ABP Pricing Description]. Other determining and influencing factors for the price and supply of cattle will be discussed:

(42) [ABP Pricing Description].

(43) [Slaney JV Pricing Description]. (17)

(44) [Slaney JV Pricing Description].

(45) This base price is applied by the Slaney JV (and all RoI beef processors) to grades representing the average animal within the EUROP grid (a standard obligatory classification system). (18) In addition to the EUROP grid, other bonuses may be applied by the Slaney JV, such as the Bord Bia Farm Quality Assured ("BBFQA") bonus and bonuses based on the weight (per kg) and age of the animal and various other commercial conditions.

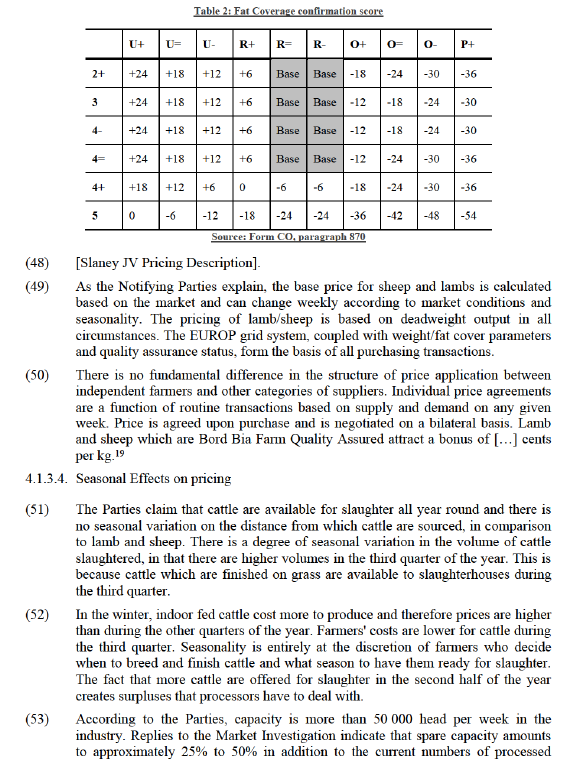

(46) As described above, ABP establishes a base price on demand for meat, supply of live animals, inventory of meat available (stock in hand) and other conditions. The base price is then adjusted based on the confirmation grade (an indicator of red meat yield and flesh coverage of the carcass) and fat score of the animal. Fat Coverage is also scored by the automated system ranging from 1 (being the lowest) to 5 (highest).

(47) An animal which has a confirmation score of R= or R- and a fat score of 2+ or 3- or 3= or 3+ or 4- or 4= receives the base price. An animal one grade better i.e. a R+ will receive an extra 6 cents per kg and an animal one grade below an R-, i.e. an O+, is penalized 12 cents per kg (depending on fat score). The increments thereafter are 6 cents per kg.

animals.20 It therefore appears that there is ample capacity to deal with any seasonal peaks. (21)

(54) According to the Notifying Parties, animal availability in the sheep and lamb meat sector is highly seasonal in nature and in order to manage production output and market demand, meat processors must follow the pattern of production. For example weekly supplies to slaughterhouses in 2015 ranged from a low of […] sheep/lambs in January to a high of […] sheep/lambs in September representing a 100% production variance. Slaughterhouses may operate at maximum capacity during these seasonal highs and have significant spare capacity during the lows. Animal availability can be influenced by a number of different factors including the season, the lambing conditions, grass growth, etc. In general, new season "spring" lamb will attract the highest price.

(55) Slaughterhouses typically price the lambs/sheep on a weekly or daily basis. The price offered is based on the current level of demand in the downstream market and the current level of supply, both of which are equally important factors. This results in a degree of price variation based on season. Established ethnic and festive demand spikes are key factors in influencing price over the calendar year. (22)

4.1.3.5. Bonuses to farmers

(56) According to the Parties, slaughterhouses provide certain rebates, bonuses, or other price incentives (collectively referred to as "bonuses") as listed below. (23)

(a) BBFQA animals - a bonus (currently […] cents per kg) is paid to all BBFQA animals depending on the following criteria:

– Animal must be under 30 months at slaughter;

– Cattle must be from a Bord Bia quality assured farm (and satisfy the 70 day requirement on last farm); and

– Cattle must not have moved more than 3 times in lifetime (4 farm residencies).

These additional specifications operate in parallel with Quality Payment System ("QPS") (24), to reward farmers for offering cattle complying with supermarket specifications. These additional specifications apply to all RoI (and UK) cattle for these customers. They are not set unilaterally by the RoI processors.

(b) Bonuses for breeds - a bonus for certain breeds (e.g. Angus and Hereford) may be paid by factories (i.e. […] cents per kg). In general, whether and what amounts of bonuses are paid depends on the time of year the animal will be slaughtered and marketing requirements at the time.

(c) Scheduling bonuses - scheduling bonuses of […] cents per kg may be paid if a supplier supplies cattle at a particular time of year in agreement with the processor.

(d) Haulage - from time to time a bonus of […] cents per kg may be paid to suppliers to attract cattle from further distances.

(e) Discretionary bonuses - a discretionary bonus up to […] cents per kg may be paid as part of bi-lateral negotiations to procure the cattle.

(f) Age penalty - a […] cent per kg penalty is levied on all animals over 36 months.

(g) A weight penalty may be levied on animals over 400 kg - specifications in relation to carcase weight limits are also outside the EUROP grid/QPS and arise as a result of downstream demand. These weight caps reflect the limited downstream customers these animals are suitable for. Price is typically reduced for animals over 400 kg. With heavier cattle, the individual cuts are too large to fit within a price range determined by retailers. For example a whole steak muscle may be too large in width dimension when sliced to fit within an individual steak pack. The width of the muscle determines the thickness to which it can be cut and if the muscle is too wide, the steak is not thick enough for retail sale. This may or may not lead to a different price per kg for carcasses over a given weight depending on the downstream demand for such carcasses on a plant by plant basis.

(57) Bonuses at (a) and (b) above are currently awarded if the animal fulfils certain criteria as outlined above. Marketing requirements as well as supply and demand dynamics within the market will determine bonuses (c)-(g). The Parties submit that in relation to the purchase of cattle in the last three years, […] of all prices are altered versus the base price. (25)

4.1.3.6. Capacity of slaughterhouses

(58) Capacity appears to be closely related to the extent of the slaughterhouses' chilling facilities as well as to customer specifications with regard to chilling. Capacity is calculated on the basis of chilling for 48 hours although it could be as short as 24 hours (increasing capacity) or as long as 72 hours (decreasing capacity). The Parties believe that 48 hours is the industry average. (26)

(59) Chilling the carcass post-slaughter is a key part of the slaughtering process, as a carcass must be below a specific temperature before it can be de-boned. The chilling facilities are the same for all animals within each species. Bovine and ovine animals can share the same facilities (i.e. "chills"), however ovine animals typically require less time (6/10 hours v 24 hrs minimum for bovine) and as they are smaller, larger numbers of ovine carcasses can chill at the same time. The chilling facilities are the same for both lamb and sheep.

(60) The Parties are of the view that there is spare capacity in all slaughterhouses in the RoI. (27) This is based on a DAFM report from 2009 stating that "It is estimated that national capacity utilisation is about 60% and drops to below 50% during periods of short supply. A particularly important characteristic in Ireland is that virtually no factory operates on a full 5-day week, with most operating between 3 and 4 days for every week of the year. The beef industry has a capacity to slaughter 3 to 3.5 million animals annually, while slaughterings range from only 1.5 to 2 million". ABP works […] shift per plant for between […] and […] days with the typical chilling being […] hours. (28)

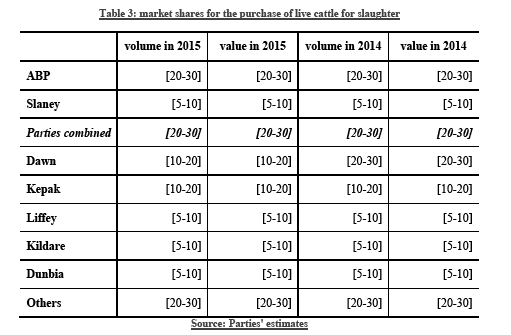

(61) ABP slaughtered […] cattle in 2015 and has capacity for […]. If the dairy herd in the RoI does eventually increase by 300 000 and ABP retain their market share of approximately [20-30]%, the additional […] animals (corresponding to its [20- 30]% share) are within ABP’s capacity. (29)

(62) The Slaney JV slaughtered […] cattle in 2015 and has capacity for […]. If the dairy herd does eventually increase by […] and the Slaney JV retain their market share of the kill of approximately [5-10]%, the additional […] animals are within the Slaney JV’s capacity. (30)

(63) The Parties submit that they do not have any plans in regard to plant closures; partial closures/mothballing of equipment; or other reduction of production, and this applies in particular also to the Slaney JV. (31)

(64) Similarly, post-transaction, none of the Parties have any plans (either standalone or for the JV post-transaction) to increase processing capacity. (32)

(65) As already indicated in paragraph (54), above availability of lambs and sheep is highly seasonal in nature and slaughterhouses follow the pattern of production (seasonal lows in January and highs respectively in September) operating at maximum capacity during seasonal highs and have significant spare capacity during the lows.

4.1.4. Sale of fresh meat (beef, lamb and mutton)

(66) According to the information submitted by the Notifying Parties, downstream customers set out their own specifications regarding the type of meat, shape, size, uniformity and how it is to be prepared and matured, which allows the customer to sell the product at a certain price point.

(67) Indicatively, retailers have demands in terms of quality, consistency, bio-security, and price. A typical customer specification would include requests in relation to country of origin; age/breed (e.g. certain products must come from animals under 30 or 36 months of age, anything labelled by breed must be meat from that breed); approval/eligibility (e.g. almost all customers require BBFQA animals); butchery information (e.g. size of cuts and fat cover ); finished weight range; packaging (e.g. type of packaging, amount of cuts per tray); shelf life dates on delivery; and label information (e.g. what is required to be indicated on the label).

(68) Meat processors then assess the level of demand including current orders from downstream customers, expected changes to orders, estimated future orders and planned or forecasted promotions, and will calculate the amount of animals required. A meat processor may also buy cattle, slaughter it and put the meat in stock expecting the same or higher prices when the meat is sold out of stock.

(69) However, if one or more customer decides to promote a particular product at retail level, requirement for that product may change (e.g. increase substantially) during any such promotion period. In addition, there may be specific additional requirements of meat processors by customers in terms of quantity, quality, type of beef and the other factors listed above. The dynamic and changing demand outlined above needs to be mirrored or matched on the supply side.

(70) Beef produced in the RoI is homogenous in terms of quality. Customers demand that the product they purchase is of a certain specification. The ability for a meat processor to fulfil customer orders on time, within specification and in full is the key driver in maintaining relationships. Retailers and other customers (caterers/international processors) frequently tender for supply (some as often as every three weeks, others less frequently). Retailers and customers have demands in terms of quality, consistency, bio-security and price. Benchmarking may be used to assess value.

(71) In relation to lamb and sheep, retail multiples, in order to meet the demands of the final consumer, require product that meets a certain price point requirement. Some retailers tender every two to three months, while other use open book pricing or ongoing index pricing. Benchmarking may be used to assess value. Butchers tend to order in small volumes and some collect from the meat processing plant directly, while others have their orders delivered.

(72) Caterers have different requirements in terms of the cuts of meat required and the size and specification of those cuts (e.g., for supplying canteens, restaurants etc.) for lamb and sheep meat. The food service sector has very specific requirements which may vary from customer to customer and for each type of meat. Industrial processors have different requirements as the lamb/mutton which they buy is likely going to be an ingredient or component of their final product.

(73) A slaughterhouse's demand for live lambs/sheep is driven primarily by demand in the downstream retail market. The downstream markets in turn is heavily dependent on the export market as domestic consumption represents on average about 30% of production. Lamb and sheep are exported from the IoI to more than 30 international markets and count most major EU retail and foodservice groups as customers for lamb from the IoI.

(74) In relation to Irish cattle, the Parties submit that they attract some of the highest prices in Europe. Given the ongoing efforts in stimulating greater demand for Irish beef in new and existing markets, and in view of security and consistency of supply, this is expected to continue. (33)

(75) According to the information submitted by the Notifying Parties, the vast majority of beef produced in the RoI is exported to other EU Member States (521,000 tonnes or 84% of all production in 2014), within which the UK is the single largest export market, with 272,000 tonnes or 52% of all EU exports for the same year. Non-EU countries accounted for a very small proportion of Irish beef production in 2014 (9,000 tonnes or 1% of the total) and exports to non-EU countries appears to have declined over the years.

4.1.5. The Commission's investigation

(76) During pre-notification as well as the first phase investigation, the Commission reviewed the Notifying Parties' submissions, sent several requests for information to the Notifying Parties and held several meetings and telephone interviews with the Notifying Parties.

(77) The Commission also sent several requests for information to third parties. More specifically, the Commission reached out to suppliers of live animals, competing slaughterhouses, industrial processors, renderers of animal by-products, supermarkets and caterers, both at EEA, as well as at national level.

(78) In particular, the Commission reached out to a number of associations of farmers in order to seek their views on market definition and potential impact of the transaction, namely: the Irish Farmers Association ("IFA") which has 75 000 farmer members, the Irish Creamery and Milk Suppliers Association which has 16 000 farmer members, the Irish Cattle & Sheep Farmers Association which has 10 000 farmer members, the Angus Society which has 8 864 farmer members, and the Irish Hereford Prime which has 3 233 farmer members. The Commission also addressed questionnaires to Bord Bia, Ireland's trade development & promotion body of Irish food, drink & horticulture, mostly known for its certification of Irish food products. Finally, the Commission obtained the views of the Department of Agriculture Food & Marine.

4.2. Purchase of live cattle for slaughter

4.2.1. Product market definition

(79) Cows are mature female bovines that have given birth to a calf. A heifer is a female bovine that has not yet had a calf or developed the mature characteristics of a cow. A steer is a male bovine that has been castrated. A bull is a male bovine used for breeding purposes. A calf is a male or female bovine animal under 12 months.

(80) Various cattle breeds exist (approximately 142 breed variants in total in Ireland) such as among others Angus and Hereford in Ireland and Shorthorn and Dexter in the UK. (34)

4.2.1.1. Previous Commission decisions and the Notifying Parties' views

(81) In the past, the Commission considered (on the basis of the absence of supply-side substitutability) the market for the purchase of live cattle for slaughter as constituting a separate market from the purchase of other live animals for slaughter and from the purchase of live calves for slaughter. (35) The Commission has not considered in the past further segmentation of the market for the purchase of live cattle for slaughter by type or by characteristics of cattle or by breed.

(82) Similarly, whilst not excluding the possibility of assessing market segments by type, age and grade of cattle, the Irish Competition Authority has in the past ultimately assessed a merger between beef processors on the basis of an overall market for the procurement of cattle for beef processing. (36)

(83) The Notifying Parties submit that the relevant product market is the market for the purchase of live cattle for slaughter and that segmentation of the market into calves and other cattle is not warranted as calves represent only 0.5% of all cattle purchased for slaughter in the RoI. (37) The Notifying Parties further submit that slaughterhouses active in the slaughter of cattle in the RoI slaughter all cattle types (cows, steers, heifers and young bulls) and that even from a downstream (beef meat) demand-side perspective, the identification of prime or premium cattle markets is not warranted. (38)

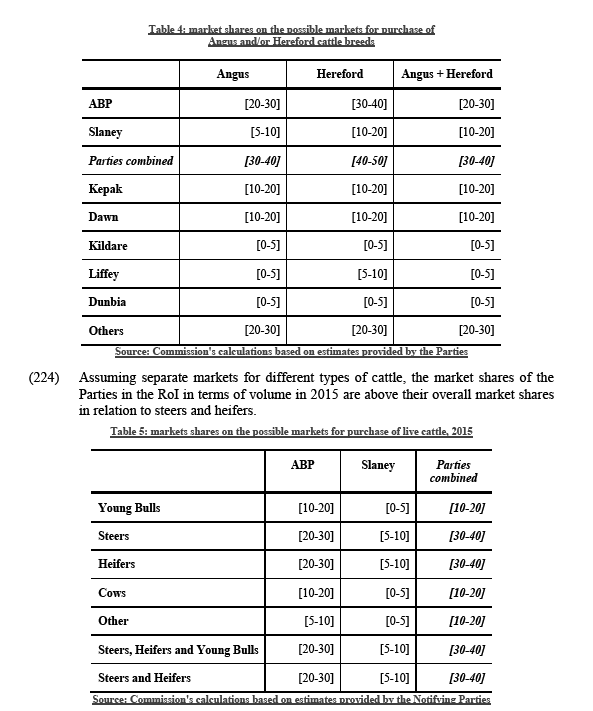

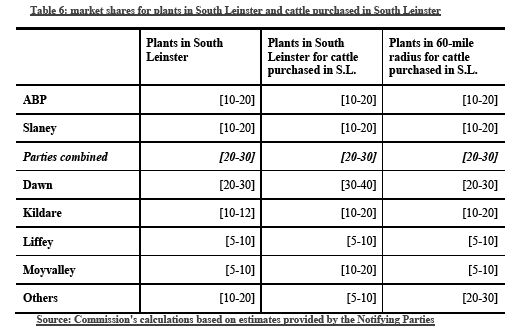

4.2.1.2. Results of the market investigation and the Commission's assessment

(84) From the supply-side perspective, the market investigation conducted in the present case indicated that the majority of farmers' associations in the RoI are of the opinion that it would take time and/or it would be costly for farmers to switch production from one breed of cattle to another. According to the Department of Agriculture Food & Marine "Due to the prevalence of cross breeding in Ireland, production of cattle in Ireland in terms of breed type is determined by sire breed. The length of time to switch production as outlined would involve switching the sire breed used in a herd and then allowing for the natural cycle of production to remove all other cattle breeds from a holding to be sold in accordance with the prevailing system of production which could range from 9 months to 30 months or over depending on the system of production (the length of time to sale of weanlings or slaughter). The cost of this would vary from farm to farm depending on the costs of production on a farm". Irish Cattle & Sheep Farmers Association as well as Irish Creamery and Milk Suppliers Association believe that it would take up to three years to switch breeds. (39) On the other hand, the majority of the farmers' associations who responded to the market investigation acknowledge that most farmers in the RoI tend to produce different breeds of cattle. (40)

(85) In relation to the different types of cattle (such as steers, heifers, young bulls), some farmers appear to be able to produce all types of cattle, where others specialise in one particular type, while still breeding cattle of other types. The Irish Farmers Association claims that "The small scale family farm structure of Irish livestock farms coupled with the grass based production systems do not allow for the multiple management of different groups of animals. The majority of Irish farmers run one management group usually of similar type. Some farmers run steers and heifers or more specialised producers run bulls". (41)

(86) The IFA has submitted a substantiated price correlation analysis regarding market definition in relation to cattle procurement markets. On the basis of this price correlation analysis which the IFA has commissioned to its economic consultant, (42) the IFA has submitted that the Transaction should not only be assessed on the basis of an overall market for the purchase of live cattle for slaughter but also on the basis of possible narrower market definitions, including markets for: (i) prime cattle comprising young bulls, steers and heifers; (ii) premium cattle comprising steers and heifers; (iii) premium cattle comprising steers and heifers meeting the grades of the Meat Industry Ireland ("MII"); (iv) premium cattle comprising steers and heifers meeting the MII grade and weight specifications. The IFA also claims that a potential market for specialty cattle breeds, like Angus and Hereford, may also warrant assessment, but do not provide any price correlation analysis or other evidence supporting this claim.

(87) In particular, the analysis submitted by the IFA shows price correlations above 0.87 for all pairs of cattle types and grades in Ireland included in the analysis. While correlation in price trends is therefore remarkable in all cases, the IFA shows some differences across pairs. On the basis of these differences, the IFA considers that "there is likely to be a market for premium cattle (all the correlation coefficients among steers and heifers are above the benchmark). There is also likely to be a market for prime cattle consisting of young bulls, steers and heifers – although the correlation coefficients among the lower grades of young bull (O2 and O3) and each of steers and heifers are below the reference value of 0.95. It is also observed that the lower grades of cows (O2, O3, O4, P2 and P3) are less highly correlated with steers and heifers (prime cattle) than the higher grades of cows (R3 and R4)."

(88) The IFA uses a benchmark of 0.95 to distinguish between pairs of cattle types and grades belonging to the same or to distinct product markets. Although differences in the level of price correlation can indeed be indicative of some degree of product segmentation, it is difficult to establish a benchmark that could be mechanically interpreted as delineating product markets. As the IFA's submission acknowledges, "there is no threshold or critical value above which the correlation coefficient can be said to indicate that products or regions lie in the same relevant market but benchmarks are sometimes applied in practice". In this case, for instance, correlation coefficients remain remarkably high for all pairs of cattle and vary around the proposed 0.95 benchmark. The somewhat lower price correlations observed between the more distant pairs of cattle in terms of quality rating (e.g. cows and steers, cows and heifers) might be consistent with some degree of vertical differentiation and segmentation. However, this is hardly conclusive regarding the absence of competitive constraints between those cattle types and grades, especially taking into account the moderate variation in the coefficients. As the IFA's economic consultant explains regarding price correlation analysis, "it alone does not provide definitive evidence of relevant market definition." Overall, therefore, the Commission considers that the price correlation analysis is inconclusive and the Commission has considered other factors to be able to conclude on product market definition.

(89) From the demand-side perspective, the market investigation has indicated that all slaughterhouses which slaughter cattle are able to process and market all the different types (cows, young bulls, steers, heifers) and all breeds of cattle (Angus, Hereford, etc.). Furthermore, in practice, all such slaughterhouses purchase cattle of all types, breeds and specifications, such as cattle having different weight, quality of carcasses, fat, grade/MII grade. (43) The market investigation indicated that slaughterhouses do not need special equipment for the finishing and processing of different types of cattle or for the finishing and processing of different breeds of cattle. The market investigation also indicated that slaughterhouses switch from finishing and processing of one type/breed to another very often, without significant cost or delays. (44)

(90) The results of the market investigation were inconclusive as regards the possible switching of a substantial part of slaughterhouses' production to another type or breed of cattle in the event of a 5% to 10% price increase of a given type or breed of live cattle. (45)

(91) Moreover, as explained in paragraph (143) below, beef meat quality appears to be a function of a number of interlinked factors and is not just determined by the type and grade of cattle. Consequently, as will be explained further in paragraphs (146) and (148), no separate market has been defined for the sale of certain quality segments of fresh beef meat. This suggests that different types and grades of live cattle are, to a significant extent, substitutable inputs from the slaughterhouses' perspective, regarding the production of fresh beef meat for sale in downstream markets.

(92) As discussed in paragraph (89) above, slaughterhouses do not differentiate between types, breeds and specifications of cattle, such as cattle having different weight, quality of carcasses, fat, grade/MII grade. Based on the above, the Commission considers that segmentation of an overall product market for the purchase of live cattle for slaughter on the basis of weight is not appropriate.

(93) The Commission considers, in light of the above that the results of the market investigation appear to support the same delineation of the market as in precedent cases, that is, a relevant market comprising all types and breeds of cattle. (46) In any event, the Commission will also assess, for the purposes of this Decision, potential segmentation of an overall cattle market by type and by breed as the Commission considers that the outcome of the competitive assessment would remain the same even in relation to such segmentation.

4.2.2. Geographic market definition

4.2.2.1. Previous Commission decisions and the Notifying Parties' views

(94) Slaney JV has only one slaughtering plant for bovine animals located in Bunclody, Wexford. ABP's six plants are located in Bandon (Cork), Cahir (Tipperary), Clones (Monaghan), Nenagh (Tipperary), Waterford (Waterford) and Rathkeale (Limerick).

(95) In the past, the Commission left the potential geographic scope of markets for the purchase of live cattle for slaughter open, assessing the transactions on a regional (on the basis of catchment areas for the delivery of cattle / cattle transportation radii of 300-450 km) and national level and, in one instance, even on an EU-wide level. (47)

(96) In a past case relating to the merger of two slaughterhouses active in the procurement and processing of cattle, whilst referring to the potential local nature of the market/catchment areas of processing plants' procurement on the basis of 30 and 60 mile radii, the Irish Competition Authority acknowledged that the market/catchment area of a particular plant may be national in light of potential chain of supply effects resulting from overlapping catchment areas and the lack of systematic differential in cattle prices across localities. (48)

(97) Whilst submitting that the market may be wider, the Notifying Parties consider that the narrowest relevant geographic scope of the market for the purchase of live cattle for slaughter is the RoI. The Notifying Parties submit that cattle prices in NI are higher than in the RoI and whilst transport of cattle across the border between the RoI and NI is feasible, it is limited as a result of labelling requirements in terms of origin and national customer preferences. Moreover, the Notifying Parties indicate that imports of cattle into the RoI amounts to less than 1%. (49)

4.2.2.2. Results of the market investigation and the Commission's assessment

(98) The majority of farmers' associations responding to the market investigation indicated that their members do not sell cattle outside the RoI. This appears to be due mainly to veterinary restrictions and labelling requirements and also appears to be the case for imports of live cattle into the RoI. If prices of cattle for slaughter outside the RoI increased by 5-10%, while prices in the RoI remained stable, farmers' associations consider that no farmer would switch to selling cattle for slaughter outside the RoI. (50)

(99) In light of this, the Commission does not consider that the relevant market is wider than the RoI and accordingly will not, for the purposes of this decision, consider a market wider than the RoI.

(100) Within the RoI, according to all farmers' associations responding to the market investigation, prices for the purchase of live cattle do not differ more than 5% from one locality to another. (51) The majority of farmers' associations indicated that their member farmers in the RoI would be prepared to switch to selling to slaughterhouses located within another locality within the RoI, if prices for cattle offered by the slaughterhouse(s) that their member farmers normally sell to would drop by 5-10%. (52)

(101) All farmers' associations, including IFA, also indicate that cattle typically travel from 30 to 60 miles to be sold to slaughterhouses. (53) Indeed, according to all the farmers' associations, farmers in practice sell the majority of their cattle within a 30-60 miles radius. (54)

(102) This is also confirmed by slaughterhouses active in the slaughter of cattle. These have indicated that they purchase cattle with a radius of 30 and 60 miles from their plants, the maximum distance within which plants tend to purchase live cattle being 150-200 miles. (55)

(103) The market investigation indicated that a 60 miles radius is not contradicted by the cost of transport (borne generally by the farmers; transportation is arranged by the farmers or their agents) which is up to 1.5% of the price of the live animal or 25- 35c/km, according to most farmers' associations and the slaughterhouses. (56)

(104) The IFA in its submission argues for an assessment based on a 60-mile (approximately 100 km) radius from the Slaney JV’s plant at Bunclody on the basis of a past Irish NCA merger review decision. (57)

(105) If one were to consider 60 mile radii, various catchment areas in the RoI would appear to be overlapping. This fact together with the indication resulting from the market investigation that prices across localities in the RoI do not appear to differ significantly, appear to point towards a market definition which may be national (the RoI) in scope.

(106) However, based on the results of the market investigation, for the purposes of this decision and particularly in light of the fact that Slaney only has one plant in the RoI (located in the South East region of the RoI), the Commission will assess the transaction applying a 60 miles radius from cattle processing plants in the RoI.

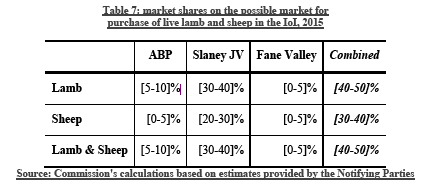

4.3. Purchase of live lambs and live sheep for slaughter

4.3.1. Product market definition

4.3.1.1. Previous Commission decisions and the Notifying Parties' views

(107) The Commission has not, to date, assessed the potential market/s for the purchase of live lambs and/or sheep for slaughter.

(108) The Notifying Parties submit that separate markets exist for the purchase of live lambs for slaughter and for the purchase of live sheep (including both ewes and rams) for slaughter, on the basis of age. The Notifying Parties state that it is generally accepted that lamb meat comes from ovine animals of 1 year or less (lambs) and mutton meat from ovine animals over one year (sheep).

(109) From a supply perspective, the Notifying Parties submit that a separate market exists for the purchase of live lambs for slaughter, on the basis of a significant price difference of 30-40% between the purchase of lamb and sheep for slaughter, with lamb attracting higher prices. The Notifying Parties also state that while the same supplier can sell both lamb and sheep this is influenced by both seasonality and the nature of the supplier. There is a degree of specialisation at the supply stage with some suppliers (including farmers and traders) specialising in the production or trading of lambs.

(110) From the demand side, the Notifying Parties claim that there is very limited demand-side substitutability, in that consumers typically view lamb as a separate and distinct product from sheep (mutton).

4.3.1.2. Results of the market investigation and the Commission's assessment

(111) The two farmers' associations whose members produce lamb for slaughter are the Irish Cattle & Sheep Farmers Association and Irish Creamery and Milk Suppliers Association. The responses of the Irish Farmers Association, Bord Bia and the Department of Agriculture Food & Marine are also relevant since the latter represent all Irish farmers. According to the Irish Cattle & Sheep Farmers Association, half (50%) of its members sell live lamb for slaughter. In relation to Irish Creamery and Milk Suppliers Association, this percentage is 10%. (58)

(112) The large majority of slaughterhouses state that they are able to process and market effectively all different types of live sheep (ewes and ram) and live lambs, without adjusting significantly their assets, making additional investment or strategic decisions, or incurring in significant time delays. (59) All slaughterhouses also indicated that the production line and equipment to process lambs are the same and that they switch production between lambs and sheep very often, or extremely often. All slaughterhouses confirmed that such switching does not take long, and in a scale of 1 to 4 with 1 being not costly, and 4 being extremely costly, slaughterhouses stated that switching between the two is "not costly" (1) or "somewhat costly" (2). (60) Should prices rise by 5-10% on a permanent basis in either live sheep or live lamb, with the price of the other remaining constant, the majority of slaughterhouses would switch their production. (61) Only one slaughterhouse considered that the two animals may belong to different markets: "sheep and lambs must both be processed to service the producer and they are 2 distinctly different markets". (62)

(113) The IFA refers in its submission to both an overall (sheep and lamb) and a narrower procurement market comprising only lambs.

(114) For the purposes of this Decision, the exact product market definition can be left open since the Transaction does not raise serious doubts in relation to any of the plausible alternative product market definitions relevant to this case; that is, in relation to: (i) an overall market comprising the purchase of live lamb and live sheep for slaughter; (ii) a market comprising the purchase of live lamb for slaughter only; and (ii) a market comprising the purchase of live sheep for slaughter only.

4.3.2. Geographic market definition

4.3.2.1. Previous Commission decisions and the Notifying Parties' views

(115) The Commission has not, to date, assessed the potential market/s for the purchase of live lambs and/or sheep for slaughter.

(116) The Notifying Parties consider that the geographic scope of the markets for the purchase of live lambs and the purchase of live sheep for slaughter is the IoI on the basis of commonality of prices for sheep and lamb on the IoI and trade flows between the RoI and NI. The Notifying Parties also claim that labelling requirements (63) and customer preferences, would not act as barriers to cross-border movement.

4.3.2.2. Results of the market investigation and the Commission's assessment

(117) From the supply side, while some farmers' associations suggest that farmers do not sell sheep and lamb outside the RoI, the Department of Agriculture Food & Marine and IFA state the opposite.

(118) According to the Department of Agriculture Food & Marine data, the total number of sheep slaughtered in the RoI in 2015 was 2 590 109 and the total number of sheep exported in 2015 was 30 583. (64)

(119) According to the farmers' associations, prices for the purchase of live lambs and sheep for slaughter in the South Leinster/Wexford/Waterford area (65) do not differ more than 5% when compared to other areas in the RoI. (66)

(120) Furthermore, according to the Irish Cattle & Sheep Farmers Association, farmers' sales of live lambs for slaughter are usually made within a radius greater than 60 miles. (67) It further specified that usually 60% of lambs are sold outside of a 60-mile radius. (68) The Irish Farmers Association considers that lambs are usually sold within a 30 to 60 mile radius. (69)

(121) The two farmers' associations whose members produce lamb and sheep for slaughter, as well as IFA indicated that prices for the purchase of fresh lambs for slaughter do not differ significantly between the RoI and NI. (70)

(122) From the demand point of view, half of the slaughterhouses slaughter live lamb and live sheep supplied by farmers based in the RoI, and the other half slaughter live lamb and live sheep supplied by farmers based both in the RoI and in NI. (71)

(123) Based on the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers, for the purposes of this Decision, that the geographic scope of the market(s) for the purchase of live sheep and/lamb for slaughter is the IoI.

4.4. Sale of fresh beef meat

4.4.1. Product market definition

4.4.1.1. Previous Commission decisions and the Notifying Parties' views

(124) In the past, the Commission has concluded that fresh meat includes both fresh and frozen meat (including minced meat) which is not further processed in any way, i.e. no other ingredients or spices have been added, nor has the meat been cooked, smoked or dried. (72) The Commission has, in previous decisions, defined separate product markets for the sale of various types (pork, veal, etc.) of fresh meat, including fresh beef. (73)

(125) The Commission has previously assessed the market for the sale of fresh beef meat on the basis of the following segmentation by distribution channel: (i) sales to retailers, further divided into sales to (a) supermarkets and (b) butchers (74); (ii) sales to caterers (such as restaurants, government institutions and ship and airport handlers); and (iii) sales of fresh beef to industrial processors (such as producers of sausages, hamburgers and canned food). (75)

(126) With reference to the possible further segmentations (discussed in detail below in paragraphs (135) to (140)) of the markets for fresh beef meat compared to the product market delineations defined in its previous decisions, the Commission hasn't considered in the past any such distinctions or further splitting of the relevant market/s based on origin, breed, type of cattle or premium.

(127) The Notifying Parties agree with these product definitions and segmentation.

(128) The Notifying Parties do not consider that a market for the sale of premium fresh beef meat – whether "Irish" beef/beef from Irish origin or otherwise (such as “premiumised” beef (76)) – exists.

(129) The Notifying Parties submit that whereas Irish beef is marketed as a quality product, the quality requirements of downstream customers can be satisfied by other beef products that have the same level of quality as Irish beef. With respect to industrial processors in particular, the Notifying Parties claim that industrial processors consider beef a commodity and beef from Irish origin is substitutable with domestically produced or imported beef of the same quality. As to the premiumising processes the Notifying Parties submit that such processes of improving the quality of the meat are not costly or difficult to run and other slaughterhouses are capable of replicating.

(130) The Notifying Parties also consider that the specific breed of the cattle is not of importance in relation to fresh meat (i.e. Angus breed meat or Hereford breed meat) that is further processed. The Notifying Parties claim that there is no functional difference between the different breeds and that farmers can switch without cost between breeds.

4.4.1.2. Results of the market investigation and the Commission's assessment

(131) The results of the market investigation conducted in the present case have confirmed the product market definition derived from the Commission's past decisional practice in relation to fresh meat, which as explained in paragraph (124) above, includes meat that has not undergone further processing. (77)

(132) The large majority of respondents to the market investigation also support the view that, in line with previous precedents, a market for the sale of fresh beef meat exists, which is separate from other fresh meat such as pork. Respondents consider that beef and pork come from different species and have very low demand-side substitutability due to their different characteristics such as taste and meat structure for example. (78)

(133) As regards the distinction between sale of fresh meat for direct human consumption on the one hand and sale of fresh meat for further processing, most respondents consider such distinction into separate product markets to be valid, including in relation to the sale of fresh beef meat, mainly due to the different way of use. (79)

(134) The majority of respondents to the market investigation also support the further division of the market for sale of fresh beef meat according to distribution channel: (i) sales to retailers, further split into (a) sales to supermarkets and (b) sales to butchers; (ii) sales to caterers, such as restaurants, canteens, government institutions, etc.; and (iii) sales into industrial processors. (80)

(135) As regards the possible distinction of fresh beef meat according to country of origin, most retailers consider the origin of the fresh beef meat for direct human consumption to be a relevant factor for the following reasons: different quality standards (between EEA countries and countries outside the EEA), labelling requirements (country of origin should be indicated for transparency towards the customers) and traceability. (81) In this respect however, according to most respondents (retailers, supermarkets and caterers), fresh beef for direct human consumption from Irish origin competes with beef from other countries such as UK, France, Belgium, Italy and beef coming from South America (certain respondents explain also that some countries such as UK and France have domestically-sourced beef with which Irish beef would compete). (82)

(136) The majority of industrial processors also consider the origin of the fresh beef meat for further processing to be of importance for largely similar reasons as the ones listed by retailers: difference in the European vs non-European beef quality and traceability of the meat back and forth in the supply chain. (83) As to the potential differences in the price paid to suppliers of fresh beef for further processing depending on the origin (nationally/domestically sources vs foreign origin) the majority of industrial processors are of the view that such difference exists, explaining that national/domestic origin carries some premium or is more expensive whereas imported meat tends to be cheaper (foreign origin being a bigger market with generally lower costs). However some respondents also note that when the quality of the meat is the same in general there will not be a significant price difference per country of origin. One respondent also points out that in certain cases the quality of the meat can be linked to the origin (Irish or French beef is more expensive than Dutch beef due to the fact that most Dutch cows are dairy cows). (84)

(137) The results of the market investigation were inconclusive as regards the possible switching to beef from different origin in case of a 5% to 10% price increase for the currently sourced beef meat of foreign origin as respondents explain this depends heavily on the customer's demands and requirements/specifications and the availability (in terms of volumes) as price is not the only factor of consideration. (85)

(138) The majority of the respondents to the market investigation (industrial processors and retailers – supermarkets and caterers) consider that the breed of the cattle is a distinctive characteristic for fresh beef meat for both direct human consumption as well as for further processing. Respondents state that breed and quality/taste of the meat are interlinked, explaining that dairy breeds should be differentiated from meat breeds. Quality beef meat from certain breeds would attract a price premium and according to some respondents there seems to be a certain level of customer awareness about the different breeds. Such well-known breeds or breeds attracting a higher price because of their better eating qualities that were mentioned by respondents include Angus and Hereford but also Kobe Style, Charolais, Aberdeen angos, Blonde d'Aquitaine, and Dutch breeds like Lakenvelder and MRIJ, thus suggesting that different quality breeds compete with each other. (86)

(139) Results of the market investigation as regards potential switching by caterers and retailers between specific breeds in case of a 5% to 10% price increase in a given breed were inconclusive for fresh beef meat for direct human consumption. As regards potential switching between breeds in relation to fresh beef meat for further processing most respondents (industrial processors), that provided a meaningful answer to the relevant question, consider that they will not switch in case of such price increase but explain that switching depends on the customer and the specific customer requirements which may entail certain kinds of breeds to maintain a certain quality. (87)

(140) In relation to another possible distinction of fresh beef meat by type of cattle (e.g. steers, heifers, young bulls, etc.) most respondents to the market investigation consider that differences exists between these types of cattle mainly because of the varying quality linked to the age change, tenderness and fat change. These differences according to the majority of industrial processors and retailers (supermarkets and caterers) are reflected by differences in the price paid for the fresh beef (due to difference in quality and age). (88)

(141) Most respondents (slaughterhouses and supermarkets) are of the opinion that premium or "premiumised" fresh beef meat exists, although the results of the market investigation did not provide a clear and conclusive picture as to what this possible premium/premiumised fresh beef market would exactly include: some respondents point out to premiumising techniques such as aging and/or dry aging, others to specific race/breed of the animal or cuts (such as ribs, fillets, striploins, rumps), or even specific growing farms conditions. (89) As to the percentage of sales that premium/premiumised fresh beef represents out of total beef sales respondents have diverging views having pointed to a very large range from 1% to 30%. (90)

(142) The Commission considers that while the results of the market investigation have provided certain indications that characteristics such as country of origin, certain breeds, types of the animal and premiumising techniques are of importance for the sale of fresh beef meat, these indications alone do not, for the reasons which will be explained further below, appear to be sufficiently strong to warrant further sub- segmentation of the fresh beef meat markets on that basis.

(143) Based on the results of the market investigation, it seems that all these characteristics relate to the quality of the fresh beef meat (and consequently to the price paid for a certain quality). However, as evident from the statements of the respondents to the market investigation (see paragraphs (136) to (140) above), beef meat quality appears to be a function of a number of interlinked factors: such as breed but also characteristics of the meat that are not related solely to the breed or the country of origin, for example tenderness and fat which relate also to the age and type of the animal, etc.

(144) Furthermore beef from Irish origin (including Irish breeds) appears to compete with beef from other countries. Also, even if some countries of origin would attract higher prices not all beef coming from the same country might be considered as being of equal quality due to the influence of other factors (including fat content, tenderness, application of a premiumising technique, etc.).

(145) As regards premium/premiumised beef would include a number of breeds rather than only premium Irish breeds such as Angus and Hereford and dry aged beef from Ireland would seem to compete with dry aged beef from other countries.

(146) Whereas higher beef quality would in general attract a higher or premium price in light of the above assessment, the evidence collected during the market investigation in the current case does not seem sufficient to support the possible existence of separate market/market segment based on any of these characteristics (including "premium/premiumises").

(147) In particular, as explained in more detail in paragraph (89) above the market investigation provided clear indications about the existence of supply-side substitutability on the side of slaughterhouses which process all types and breeds of cattle and can easily and at no cost switch between processing different types or breeds of bovine animals.

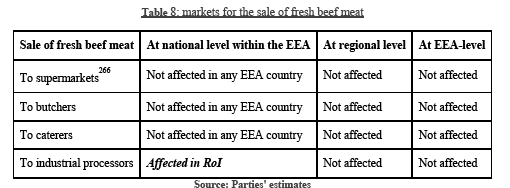

(148) In light of the above, the Commission therefore considers that, for the purposes of this Decision, the product markets that are relevant for the assessment for the present case consist of the market for sale of fresh beef meat to supermarkets, the market for sale of fresh beef meat to caterers and the market for sale of fresh beef meat to industrial processors.

4.4.2. Geographic market definition

4.4.2.1. Previous Commission decisions and the Notifying Parties' views

(149) In the past, the Commission has considered three possible alternative geographic market definitions for the sale of fresh beef to supermarkets: (i) national; (ii) cross-border regional (such as including the Benelux, Denmark, France and Germany); and (iii) EEA-wide, leaving the question about the exact geographic scope open. (91)

(150) The Notifying Parties claim that the sale of fresh beef meat to supermarkets is EEA-wide based on the following: significant imports/exports, limited transport costs (estimated to be around 2% of the average sales prices), packaging techniques allowing long shelf-life of meat products (92), international sourcing by supermarkets and uniform European quality standards.

(151) With regard to the sale of fresh beef to caterers and to industrial processors, in its previous decisions the Commission considered the relevant geographic scope of the market to be wider than national, leaving however the exact geographic market definition open. (93)

(152) The Notifying Parties submit that both the markets for sale of fresh beef to caterers and to industrial processors are EEA-wide in scope. The Parties submit that caterers and industrial processors source beef from abroad and use EU beef and beef imported from third countries interchangeably. Around 90% of beef meat produced in Ireland is exported: an estimated 560,000 tonnes (carcass weight equivalent "CWE") of Irish beef was produced in 2015, of this an estimated 524,000 tonnes CWE of beef was exported. (94) The largest market for beef exports from Ireland is the UK, which accounts for approximately 57% of total Irish beef exports (272,000 tonnes of beef). (95) The imports of beef from non-EU countries (including Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Australia, USA and New Zealand, accounting together for nearly 90% of the imports) to the EU in 2015 amount to 332 723 tonnes. (96)

4.4.2.2. Results of the market investigation and the Commission's assessment

(153) As regards the sale of fresh beef meat for direct human consumption to supermarkets, the results of the market investigation did not yield a clear picture in this respect as respondents appear to have diverging views: most slaughterhouses consider the market for sale of fresh beef to retailers/supermarkets to be EEA-wide whereas most retailers/supermarkets consider it to be of a national scope. Few respondents also state that, in their view, there are no legal, commercial, veterinary or other barriers to export fresh beef for direct human consumption to other EEA counties. (97)

(154) Similarly, the results of the market investigation in relation to the geographic scope of the market for sale of fresh beef meat to caterers were inconclusive: the views expressed by slaughterhouses, most of which consider the market to be EEA-wide, differ from the opinion expressed by most caterers that replied to the relevant question who consider the market to be national in scope. As mentioned already in paragraph (153) above, several respondents consider that there are no legal, commercial, veterinary or other barriers to the export of fresh beef for direct human consumption to other EEA counties. (98)

(155) With respect to the market for sale of fresh beef meat to industrial processors the majority of the respondents (both slaughterhouses and industrial processors) are of the view that the relevant geographic scope of the market is wider than national (cross-border regional or EEA-wide). Couple of respondents indicate that industrial processors can switch from Irish to for instance French or German beef, provided this is allowed by the customer requirements. (99) Indeed industrial processors appear to source fresh beef meat for further processing from a number of countries: Ireland, France, the Netherlands, UK, Germany, Italy, Scotland, and Poland. (100) In addition, half of the industrial processors that responded to the market investigation confirm to have switched (either rarely or occasionally) a supplier of fresh beef from one country with a supplier in another country. (101)

(156) Based on the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers that the exact geographic market definition of the relevant markets for sale of fresh beef to each of (i) retailers/supermarkets, (ii) caterers; and (iii) industrial processors can be left open since the Transaction does not raise competition concerns under any possible geographic delineation of the relevant markets.

4.5. Sale of fresh lamb meat

4.5.1. Product market definition

4.5.1.1. Previous Commission decisions and the Notifying Parties' views

(157) The Commission has not, in the past, assessed potential markets for the sale of fresh lamb or mutton meat.

(158) With regard to meat from the same animal species (bovine species), the Commission has previously defined separate markets for veal meat (from calves) and beef meat (from cattle). (102)

(159) As regards to ovine animals, male and female ovine animals under 12 months are designated as lamb whereas male and female ovine animals over 12 months are designated as sheep.

(160) The Notifying Parties submit that there is a distinct market for the sale of fresh lamb, separate from the markets for sale of fresh beef or other meat such as fresh pork meat for example. The Parties further submit that the further segmentation of the market for fresh beef meat by sales channel into (i) retailers, further divided into supermarkets and butchers; (ii) caterers and (iii) industrial processors is also representative for the sale of fresh lamb meat.

(161) The Notifying Parties consider that no distinct market for premium fresh lamb exists claiming that lamb is a premium quality product while in certain instances individual cuts may be marketed as "premium" (i.e. frenched lamb racks) but the added value is introduced purely through the butchery and trimming of the lamb meat.

(162) The Notifying Parties also submit that as the meat is further processed into a finished product before being sold to customers, the origin of the meat is likely to be of less importance to the final consumer.

4.5.1.2. Results of the market investigation and the Commission's assessment

(163) The large majority of respondents to the market investigation (slaughterhouses, retailers – supermarkets and caterers, and industrial processors) share the view that the sale of fresh (103) lamb and mutton meat constitutes a distinct market, separate from the markets for other meat such as pork or beef. Respondents consider that lamb, pork and beef are very different products with very low demand-side substitutability because the characteristics of each of these types of meat (taste, meat structure, etc.) are very different. Respondents also explain that there is price differentiation between lamb and mutton (as well as between lamb meat compared to pork meat, with lamb being up to 3 times more expensive than pork). (104)

(164) The results of the market investigation as to whether fresh lamb meat and fresh mutton meat belong to the same product market or to separate markets were not conclusive, although statements of the respondents indicate that lamb meat on the one hand and mutton meat on the other hand might belong to separate markets in view of the different seasonality of each (fresh lamb and fresh mutton primarily supplied at different times of the year), the differences in quality and taste (age difference between lamb and sheep), the indications about limited demand-side substitutability by the end-consumer, as well as the price differentiation between the two (mutton being cheaper). (105)

(165) As regards the further segmentation of the possible separate market for fresh lamb meat by analogy to beef between (i) fresh meat for direct human consumption and fresh meat for further processing; and (ii) by distribution channel: retailers (further split between supermarkets and butchers), caterers and industrial processors respectively, the results of the market investigation suggest that such segmentation appears to be appropriate for lamb meat. Indeed respondents state these distribution channels require different packaging formats, involve different clients, and the meat is treated and used in different ways. (106)

(166) Concerning a possible distinction of fresh lamb for direct human consumption by origin (between imported fresh lamb and domestically/nationally sourced lamb) most retailers and caterers consider that the country of origin is a characteristic of distinction due to the difference in quality depending on the origin, impact of the feeding regimes and breeds, the labelling requirements (origin of the meat needs to be indicated for customer transparency) and the fact that some customers have preferences for lamb sourced locally/regionally for sustainability reasons. According to one respondent all origins have their own advantage, including seasonality. (107)

(167) Most retailers that replied to the relevant question from the market investigation consider that there is a price difference for fresh lamb for human consumption from foreign origin compared to nationally/domestically sourced lamb without providing further information. (108) The market investigation results did not provide a clear picture as to the possible switching of retailers between fresh lamb meats of different origins in case of a 5% to 10% increase in price. (109) The results obtained during the market investigation suggest that supermarkets in Belgium source fresh lamb meat from a number of countries: New Zealand, Australia, England/UK, Ireland, Belgium and France. (110)

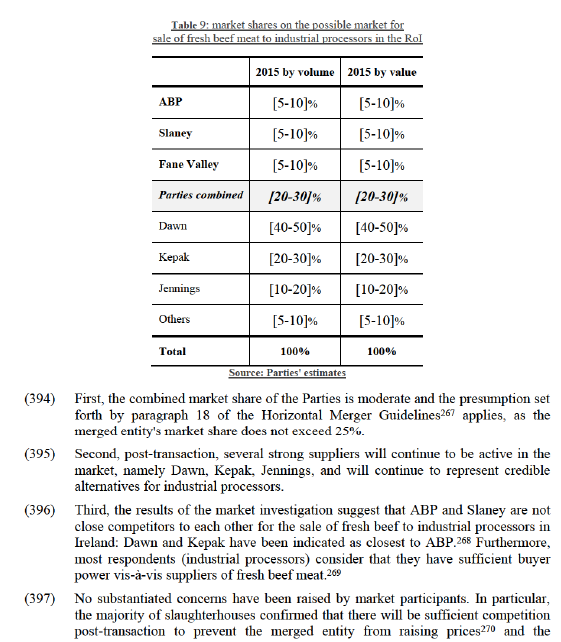

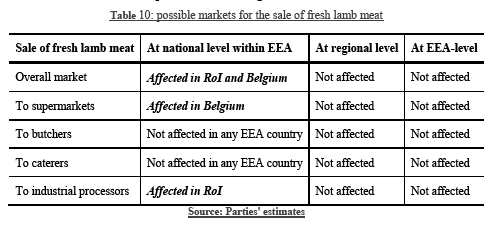

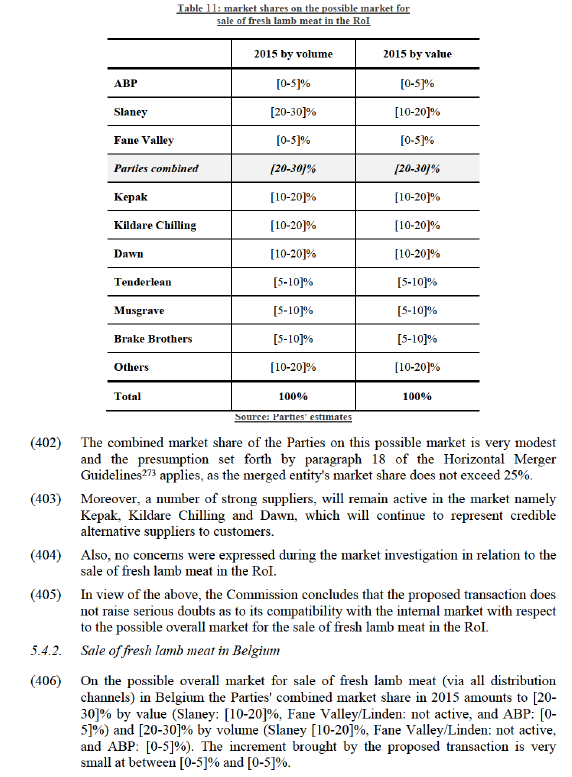

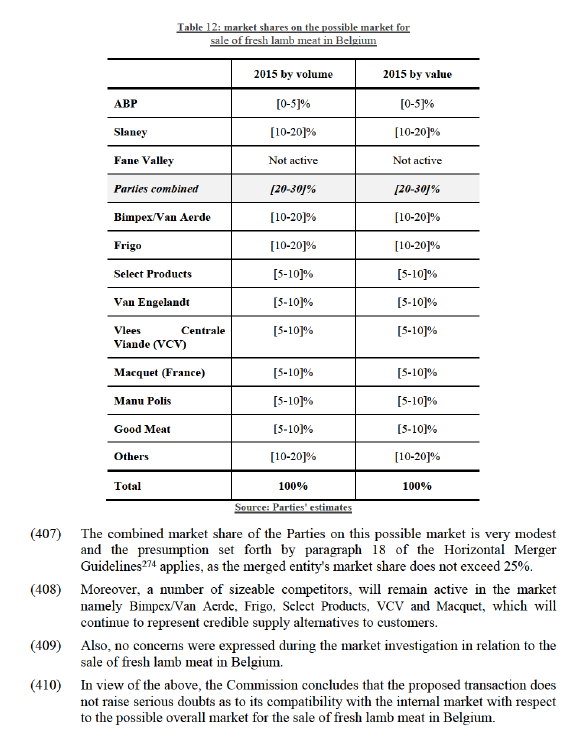

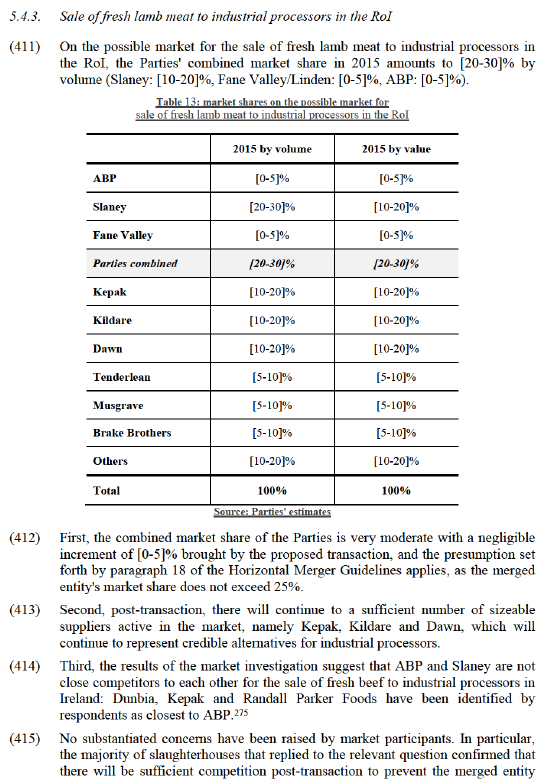

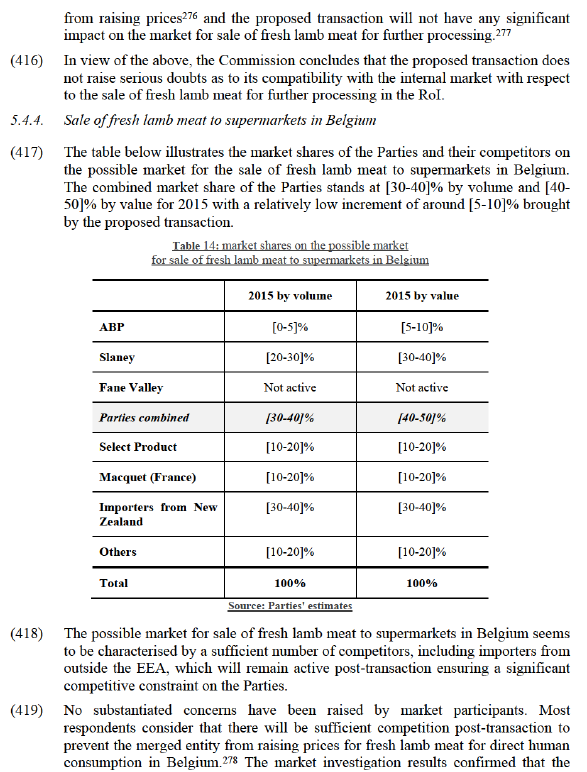

(168) As regards fresh lamb for further processing most industrial processors that provided a meaningful reply to the respective question from the market investigation, consider, similarly to retailers, that the origin of fresh lamb meat plays a role mainly for the same reasons of quality and specifications which are connected to the origin. (111) Industrial processors also consider that there is a price difference by origin for the similar reasons outlined for beef (see paragraph (136) above): one respondent explains that lamb meat from Ireland has a lower price than lamb meat from France, presumably due to lower production costs (lamb from foreign origin being a larger market compared to domestic markets with respectively lower costs in general). (112)