Commission, April 7, 2017, No M.8257

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Judgment

NN GROUP / DELTA LLOYD

Subject: Case M.8257 - NN Group / Delta Lloyd

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/2004 (1) and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (2)

Dear Sir or Madam,

1. On 22 February 2017, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (3) by which NN Group N.V. (‘NN’) of the Netherlands acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation control of the whole of Delta Lloyd N.V. (‘Delta Lloyd’), also of the Netherlands by way of a public bid announced on 2 February 2017 (‘the Transaction’). NN is referred to as ‘the Notifying Party’ and NN and Delta Lloyd are collectively referred to as ‘the Parties’.

I. THE PARTIES AND THE OPERATION

2. NN is a Netherlands-based financial services provider active in the provision of life and non-life insurance policies, pension products, banking and asset management to both individuals and corporations. It is active in 18 countries worldwide, including a number of European markets.

3. Delta Lloyd is a Netherlands-based financial services provider active in the provision and distribution of life and non-life insurance policies, pension products, banking services and asset management to both individuals and corporations. It is active in the Netherlands and Belgium.

4. The Transaction involves the acquisition within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) by NN of the whole of Delta Lloyd by way of a public bid announced on 2 February 2017. This formal offer marked the start of a nine-week offer period (ending 7 April) during which Delta Lloyd shareholders can choose to sell to NN on the terms set out in the bid.

II. EU DIMENSION

5. The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (4) (NN EUR [10 000 - 15 000] million, Delta Lloyd EUR [0 - 5 000] million). Each of them has EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (NN EUR [5 000 - 1 0000] million, Delta Lloyd EUR [0 - 5000] million). Delta Lloyd achieves more than two thirds of its aggregate EU-wide turnover within one and the same Member State (the Netherlands) but NN does not. The notified operation therefore has an EU dimension.

III. MARKET DEFINITIONS

III.1. Introduction

6. NN and Delta Lloyd are both Netherlands-based financial services providers, whose principal activity is in the area of insurance. They both offer pension products, life and non-life insurance policies, alongside various banking services. The Transaction leads to horizontal and vertical links in the Netherlands and in Belgium.

7. In the Netherlands, the Transaction creates a number of horizontally affected markets within the following broad markets: pension products and pension fund buy-outs, individual life insurance, non-life insurance and insurance services to pension funds. In addition, it also creates vertically affected markets between the production of insurance and: the downstream market for insurance distribution, the upstream market for asset management, the upstream market for pensions administration services and the upstream market for reinsurance.

8. In Belgium, the Transaction leads to several horizontal overlaps and vertical links between various markets in the area of insurance, insurance distribution, reinsurance and asset management. None of them is, however, an affected market.

9. The following assessment therefore focuses on the specific characteristics of the relevant product and geographic markets in the Netherlands.

III.2. Relevant markets

10. In previous decisions relating to the insurance sector, the Commission has distinguished between a product market for insurance provision and a product market for insurance distribution.

11. Within the upstream market for insurance provision, three broad categories of insurance products can be further distinguished: life insurance, non-life insurance and re-insurance. (5) The Commission has considered the possibility that both life and non-life insurance could be divided into as many different product markets as there are types of risks to insure. This possible distinction is based on the fact that the characteristics and purpose of the different types of insurance are distinct, and that there is typically no substitutability between different types of insurance from a customer’s perspective. (6) The Commission has, however, also noted a previous case that there were indications of potential degree of supply-side substitutability between some insurance products. (7) Within the downstream market for insurance distribution, the Commission considered that a distinction could be made between the distribution of non-life and life insurance products and left the question of further segmentation open. (8) In its past practice, the Commission has also left open the possibility of whether the market for insurance distribution comprises exclusively third-party outward insurance distribution channels (such as brokers, agents and banks) or whether direct sales forces should also fall within the market for insurance distribution. (9)

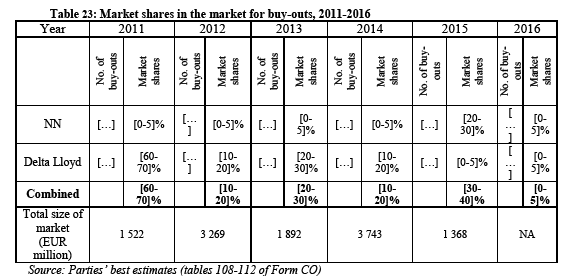

III.2.A. Life insurance

12. The Commission has further considered segmenting the life insurance market according to the purpose served by the product, distinguishing between: (i) pure risk protection products; (ii) savings and investment products; and (iii) pension products. (10) In addition, the Commission has considered a possible segmentation of these product markets between group and individual products. (11)

13. The Notifying party agrees with the definition of a possible market for pension products, but argues that a segmentation between pure risk protection and savings and investment products is not appropriate in the Netherlands. Likewise, the Notifying Party notes that in the Netherlands pension products are offered only to group customers (employers acting on behalf of their employees), whilst pure risk protection products and savings and investment products are both only offered on an individual basis.

14. The respondents to the market investigation confirmed the Notifying Party’s claim that there is a strong distinction in the Netherlands between pension products, on the one hand, and individual life insurance (including both pure protection and savings and investment products) on the other. Indeed, in the Netherlands, the former are purchased by employers for the sake of their employees (group products) while the latter are only purchased by individuals (individual products). Furthermore, pension products can only be distributed by professional intermediaries holding a specific regulatory license and, thus, insurers are not allowed to sell their pension products directly to customers. Conversely, individual insurance products are purchased by and at the initiative of interested individuals directly from insurers or via any distribution channel.

15. In view of the above, the Commission considers that the segmentation of life insurance into pension products, pure risk protection products and savings and investment products makes any further segmentation into group and individual products redundant in this case since, in the Netherlands, pension products are group products while pure risk protection and savings and investments are necessarily individual products. The product markets to be analysed are: (i) pension products for group customers; (ii) pure risk protection products for individuals; and (iii) savings and investment products for individuals.

16. The Commission previously considered the geographic market for life insurance and its respective segments to be national in scope, as a result of national distribution channels, established market structures, fiscal constraints and specific regulatory systems among Member States; however the exact geographic market definition has been left open. (12) The market investigation in the present case has not provided any evidence that would indicate that the market for life insurance in the Netherlands should not be considered national in scope.

III.2.A.1 Pension products

17. Within pension products, the Commission has considered several distinctions which can be made, in particular between defined benefit (DB) and defined contribution (DC) pension types, and has also identified the existence of distinct accumulation and decumulation products. (13)

18. The Notifying Party contends that there is no need to consider narrower hypothetical markets, such as those described above (DB/DC schemes, accumulation/decumulation products), and submits that in the Netherlands there is one broad market for group pension products, which should not be further segmented.

Distinction between DB and DC schemes

19. Under a DB scheme, each employee is guaranteed a pension equivalent to a fixed percentage of their final or average salary earnings (depending on the terms of the scheme). Under a DC scheme, meanwhile, the employer and the employee each pay a fixed contribution (a percentage of the employee’s salary), and this is then invested for the employee. The return achieved on the investment determines the value of the individual’s pension at retirement age, and he/she can then purchase an annuity with this capital sum.

20. The distinction between DB and DC is blurred in the Netherlands, due to the variety of different pension arrangements present on the market (see section IV.8): DB schemes offered by insurers include a guaranteed level of pension benefit but most of the industry pension funds, for example, are structured as DB pension schemes but with pension benefits that can be reduced or no longer indexed if the scheme is underfunded. Similarly, a further distinction can also be made within DC schemes between unit-linked and non-unit-linked policies: unit-linked DC policies could be described as ‘pure DC’ policies, as they do not offer any form of guarantees, whereas non-unit-linked DC policies incorporate aspects of DB policies, in that they include certain guarantees in respect of the value of the capital accumulated over the period up to retirement, and the risk is therefore not entirely with the members.

21. As set out below, the market investigation revealed that the most natural segmentation of the market for pension products would be between defined benefit (DB) and defined contribution (DC) products, as recognised in past Commission decisions. (14)

22. From a demand-side perspective, customers of group pension products are employers acting on behalf of their employees. The employers who responded to the market investigation appeared to be well aware of the fundamental difference between the two types of pension scheme insofar as, under a DB arrangement, the risk is borne by the employer (meaning they are liable for a pension shortfall), whereas under a DC arrangement, the risk is borne by the employee. A large majority of respondents (customers, distributors and competitors) also acknowledged that DB has largely become unaffordable for new customers in the Netherlands. This means that DB and DC schemes are only competing in cases where a customer (employer) has the choice of renewing a DB policy or moving to DC. An employer that already has a DC arrangement is highly unlikely ever to wish to move back to DB (due to the risks for the employer mentioned above). To conclude, from a demand side perspective, DB and DC pension products seem to constitute separate markets as they tend to address different needs, in particular related to risk appetite and/or the ability to incur significant costs for future benefits.

23. From a supply-side perspective, offering DB products requires an insurer to hold much higher capital levels than they have to for DC products (under solvency regulations), reflecting the higher level of risk involved. Setting aside industry and company pension funds (which are, to some extent, a closed market and which are further described in section IV.2 129 and IV.4 below), providers of pensions in the Netherlands are not necessarily present in both DC and DB. All the main six insurers have clients for both types of pension arrangements, but some only offer DB to existing DB clients (i.e. renewals) and others are thought not to be offering DB anymore at all. At the same time, the new pension vehicles that have recently been introduced on the Dutch market are very much oriented towards either DB or DC. Premiepensioeninstellingen (PPIs) are only licensed to offer DC pension schemes whilst algemeen pensioenfonds (APFs) were designed as a solution for company pension funds, whose schemes are almost always structured as DB (although without absolute guarantees). Although there are currently two APFs which also offer DC pension arrangements, the general expectation, in particular expressed by distributors of pension products (15) seems to be that APFs will be much stronger in DB since they constitute an attractive alternative to liquidating company pension funds (OPF) most of which currently operate DB schemes. (16) From both the demand and the supply side, there therefore seems to be a strong suggestion that DB and DC pension products constitute separate markets, with different (although not mutually exclusive) sets of providers, and significantly different product characteristics.

24. For the purpose of this case, the question as to whether DB and DC pension products form separate product markets can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition on the market for pension products under any plausible market definitions based on the potential distinction between DB and DC pension schemes and the further segmentation of DC schemes into unit-linked and non-unit-linked products.

Distinction between accumulation and decumulation products

25. Pension products are comprised of two distinct phases: accumulation and decumulation, the accumulation phase being the period during which an active scheme member pays contributions into his/her pension and the decumulation phase being the payment out of the pension after retirement age, via an annuity. The distinction between accumulation and decumulation does not, however, have the same relevance in DC and DB policies.

26. DB policies do not allow an individual to move to a different provider for the decumulation phase. Accumulation and decumulation are provided as part of one DB product, i.e. neither could exist independently.

27. A member of a DC pension scheme, meanwhile, can change the provider for the decumulation phase: on reaching retirement age, each individual has the opportunity to shop around for an annuity product, which will provide a retirement income during the decumulation phase. The market investigation provided some evidence to suggest that a distinction could be made between accumulation and decumulation products within the market for DC pension products. From a demand-side perspective, the products are clearly in no way substitutable as they serve customers in distinct phases of their pension – saving for the pension, and payment out of the pension, respectively. In addition, the customer is also different, with DC accumulation schemes being purchased by employers, whilst annuities are chosen by the individual members.

28. From a supply side point of view, the two products could, in very general terms, be seen as requiring the same resources and expertise, as both are insurance products. They also require the same type of communication with pension scheme members. Insurers who provide DC schemes to employers typically also offer annuities for the members to buy on retirement. The market investigation provided an example of an insurer that had become active on the DC market recently, and therefore had not immediately offered annuities, but had subsequently introduced this product. There was no other evidence, however, of insurers choosing to only offer accumulation or decumulation products respectively. In addition, the very high percentage of customers thought to purchase an annuity from the provider of their DC accumulation scheme (usually for convenience) suggests that it would be very difficult to operate successfully in the decumulation market alone, i.e. as a provider of annuities, without also offering DC schemes. To conclude it appears that as regards the supply side a distinction between accumulation and decumulation products seems less relevant, since both categories of products require the same resources and most providers offer both of them.

29. It should, however, also be noted that a certain category of providers of DC pension products in the Netherlands (PPIs, see section IV.6 below) had not until very recently been licensed to sell any decumulation products. PPIs are not required to meet the same solvency requirements as insurers and therefore cannot take on the risks that these products involve. The recent introduction of variable annuities in the Netherlands (described in more detail in the following section) means that PPIs can now offer decumulation products, but only in the form of variable annuities. Since these products have been introduced only recently it is yet too soon to be able to predict with any certainty how popular variable annuities will become. Some respondents to the market investigation expected variable annuities to remain very much a minor product on the market, with only a small minority of customers potentially being interested. In any event, PPIs are not allowed to offer fixed annuities, which at least for the moment remain the most popular decumulation products. The fact that certain (important) category of providers of pension accumulation products, are not allowed to provide the most popular pension decumulation products, would suggest that the supply side substitutability of accumulation and decumulation products is at least limited to certain categories of providers.

30. For the purpose of this case, the question as to whether accumulation and decumulation products form separate product markets within the pensions market can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition on the market for pension products under any plausible market definitions based on the potential distinction between accumulation and decumulation products.

Fixed annuities versus variable annuities

31. The introduction of variable annuities also raises the question as to whether fixed and variable annuities are part of the same product market for DC decumulation products, or whether they each form separate product markets.

32. A customer who buys a fixed annuity is guaranteed a certain regular pension for the rest of their life. The most commonly purchased type of product in the Netherlands is an immediately effective life annuity (direct ingaande pensioen, DIP).

33. As of 2016, members of DC schemes can also use their capital to purchase a variable annuity product, doorbeleggen. Unlike a fixed annuity, a variable annuity offers no guaranteed level of benefits, but the product is converted into a fixed annuity, usually when the policyholder reaches the age of 85. A number of providers have already introduced such products and others are in the process of doing so, meaning that customers will now be able to choose between fixed and variable annuities.

34. From a customer’s perspective, the choice between a fixed and a variable annuity is largely a question of propensity for risk-taking. Depending on how markets develop, customers may be better off with a variable annuity, but could equally be worse off. Some customers may therefore prefer to purchase a fixed annuity to have the certainty of a guaranteed level of income for the duration of their retirement.

35. The Notifying Party contends that fixed and variable annuities form part of the same market. It argues that they are substitutable from a demand-side point of view, as they both provide an income stream during retirement, and it could not be said that one will perform consistently better than the other.

36. The Notifying Party further points out that the expertise required to offer a variable annuity is generally very similar to that needed for fixed annuities. The main exception is investment expertise, which is more important for variable annuities. In the Notifying Party’s view, any provider, such as a PPI, which did not have such expertise in-house, could in any case make use of external consultants or investment managers.

37. Nonetheless, the difference in risk level between variable and fixed annuities suggests that they may not be entirely substitutable for all consumers. Furthermore, even if a provider of fixed annuities could easily start offering variable annuities, this does not necessarily indicate that the reverse is true. The possible range of providers of fixed annuities is more limited than that of variable annuities, due to the requirement to hold certain levels of capital and to be licensed to insure the implicit risk in a fixed annuity.

38. The results of the market investigation were not conclusive as to whether fixed and variable annuities should be considered as part of the same or as separate product markets. Variable annuities have only been sold since very recently and many market participants felt it was too early to express a definite opinion on the extent to which they will represent a genuine alternative for customers. From a supply side point of view, the competitors in response to the market investigation suggested that most major insurers have or will soon introduce variable annuities (17). The competitors also suggested that all pension providers will be capable of offering variable annuities should they choose to do so.(18) In terms of the product characteristics, however, competitors confirmed that fixed and variable annuities have quite different features: whilst fixed annuities offer certainty, variable annuities offer the chance of a higher return, but with an element of risk.(19) Competitors’ views on the extent to which variable annuities constitute an alternative to fixed annuities were mixed, but in general they seemed to think that variable annuities could be attractive to customers, but only if the variable annuity is an additional pension (i.e. on top of a DB pension) or if the customer can choose an annuity which combines a fixed and a variable element. (20) This suggests that, in some circumstances, customers may not see variable annuities as a real alternative to fixed annuities, but rather a complementary product. The responses of some competitors and pension product distributors also suggested that variable annuities may only ever be popular amongst a small group of customers, typically the higher educated employees who understand variable annuities and can afford to take this type of risk. (21)

39. Competitors’ responses further suggested that the current low interest rates are likely to make variable annuities more attractive to customers, because there is a chance that the value of the annuity will increase if interest rates rise in the future. Conversely, a customer choosing a fixed annuity would be locked in to a low rate.

40. For the purpose of present assessment, the question as to whether fixed and variable annuities form separate product markets within a hypothetical decumulation market can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition on the market for pension products under any plausible market definitions based on the potential distinction between fixed and variable annuities.

III.2.A.2 Individual life insurance

41. In previous cases the Commission has considered the existence of a hypothetical market for pure protection products. (22) These are products where, in return for a regular premium, the insurer agrees to pay a lump sum on a certain specified event such as death or serious illness. These products do not include any investment element. Pure protection policies may include mortgage protection policies, term- life insurance (i.e. protection for a defined period, where the policyholder chooses the cash sum they wish to save for to cover their families in the event of death or the expiration of the policy), whole life policies (which pay on death of the insured) and critical illness cover. (23)

42. Within the category of pure protection products, there are several different types of products that are not substitutable from a demand side perspective. In the past, the Commission has, however, also noted that there were indications of a degree of supply-side substitutability between certain pure risk protection products. Therefore, in a recent case the Commission has left it open whether pure protection products constitute one product market, or whether this market should be segmented according to various risks covered. (24)

43. In previous cases the Commission has also considered the existence of a hypothetical market for savings and investment products. (25) This market encompasses life insurance products with an investment element, which therefore serve the purpose of wealth accumulation. Any protection product that would have an investment element was not considered a “pure” protection product and would thus be part of “savings and investments” products. These include: tracker funds (where the investment return over a specified period is based on the performance of one or more stock market indexes), guaranteed funds (which provide a guaranteed return over a specified period), managed funds (pooled funds investing in a mix of assets such as equities, securities and property), personal investment plans and personal equity plans. In general, the products within this category differ in relation to the mechanism used to generate returns.

Pure protection products

44. The Notifying Party argues that the types of insurance policies available in the Netherlands do not fit naturally into a segmentation between pure protection and savings and investment, as the same products can be bought for different purposes by different customers.

45. However, contrary to the Notifying Party’s suggestions, the replies to the market investigation did not provide any evidence which would suggest that in the present case the Commission should depart from the past practice and include pure protection products and savings and investment products in one product market. The Commission notes that the types of products that make up the vast majority of sales of pure protection products in the Netherlands – funeral insurance and term-life insurance – are sold to protect against very specific risks (term-life insurance being used to cover the cost of, most often, repaying a mortgage, or sometimes rental payments or the cost of living of the family after the death of the insured party) and these products do not include investment elements. Conversely, savings and investment products sold in the Netherlands are fiscally incentivised products through which the policyholder saves up to purchase an annuity on retirement. This annuity then provides an additional retirement income. It is thus clear that in general pure protection and savings and investment products serve different needs.

46. Furthermore, within pure protection products, one could distinguish separate markets based on the distinct risks they cover, namely for term-life insurance and for funeral insurance. For the purpose of this case, only the market for term-life insurance needs to be considered, as both Parties have ceased offering funeral insurance.

47. In view of the above, as regards pure protection products, for the purpose of this case, the Commission will assess the impact of the Transaction, on plausible relevant product markets comprising either all pure protection products or specifically term-life and funeral insurance products. The question as to whether term-life products do form a separate market within pure protection products can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition under either approach.

Savings and investment products

48. The savings and investment products available in the Netherlands are all designed as a way of saving for extra retirement income (in addition to an individual’s pillar 2 pension). Some include the savings phase and the payment out of retirement benefits in one product, whilst others only comprise the savings phase, but include an obligation to purchase an annuity at the end of a fixed period. Some savings and investment products also include a term-life component, i.e. a benefit which is fixed.These policies are therefore usually non-unit-linked, whereas all other savings and investment products are unit-linked.

49. Savings and investment life insurance products have declined sharply in popularity in the Netherlands in recent years, in particular due to misselling of unit-linked policies during the period 1990 to 2008. (26). The negative connotations since associated with these products have led most insurance companies to cease offering them to new customers. Business for unit-linked savings and investment products is therefore largely limited to servicing of existing policies.

50. The market investigation revealed that traditionally savings and investment products are increasingly being replaced by a new type of savings product, banksparen, which were introduced in 2008 and are provided under a banking licence. Similarly to traditional savings and investment products, banksparen also benefit from favourable tax treatment as pillar 3 products (27) and are purchased in order to save up for buying an annuity on retirement, which then supplements the individual’s pillar 2 pension income. (28)

51. The question therefore also arises as to whether traditional savings and investment products provided within life insurance and banksparen do form part of the same market. (29)

52. The range of traditional life insurance products includes both products for saving to provide income in retirement, (e.g. deferred annuities, lijfrente uitgesteld) and annuities (most often an immediately effective annuity, direct ingaande lijfrente) which are purchased on retirement. Banksparen is based on the same concept, with products being available for the savings phase and for payment out during retirement in the form of annuities. Banksparen could therefore be considered to mirror traditional savings and investment products in terms of the structure of the product range.

53. On the other hand, banksparen differ from traditional life insurance policies in a number of ways, most importantly: i) the annuity part of banksparen is of a fixed duration (usually up to a maximum of 30 years after retirement age), meaning that the insurer does not bear longevity risk, ii) should the provider go bankrupt, capital is only covered up to EUR 100 000 for banksparen (whereas the full amount is recoverable under an insured policy), and iii) should the policyholder die before the end of the policy, the policy will be paid out to his/her inheritors, which is not the case for life insurance.

54. Sales of banksparen have grown rapidly since their introduction in 2008, and if considered as part of the individual life insurance market, currently represent over 75% of new business. Both NN and Delta Lloyd offer banksparen through their banking subsidiaries, as do most of the other main insurers. NN stopped offering its single premium immediate annuity product in January 2017, and the Notifying Party explains that this is in part due to the fact that this product had been marginalised by banksparen. It would appear that insurers in general are accepting that the traditional life insurance market is shrinking (at least insofar as concerns savings and investment products and annuities) and they are therefore devoting their efforts to winning market share in banksparen, to compensate for the lost revenue in individual life insurance. (30) It could thus be argued that business is simply shifting from individual life insurance to banksparen, with the two types of product fulfilling the same customer need.

55. In view of the above, the Commission considers that there are strong arguments to consider that banksparen form part of the market for savings and investment individual life insurance products.

56. The Notifying Party argues that any hypothetical market combining traditional life insurance products and banksparen is not a meaningful product market. The basis for this claim seems, however, to be more based on internal record-keeping (i.e. the fact that revenue for the two classes of products is recorded and assessed differently) than on any consideration of supply- or demand-side substitutability.

57. The results of the market investigation generally confirmed that market participants see banksparen as a direct substitute for some life insurance products. One competitor stated that banksparen accounted for 70% of its sales of pillar 3 savings in 2013, and are now estimated to make up almost all sales. (31) The way in which competitors describe the changes in the overall size of the market show that they automatically view banksparen as being within the same market. (32)

58. Responses to the market investigation confirmed that sales of traditional annuities have declined rapidly due to the introduction of banksparen, which are generally preferred by customers as they are seen as more transparent and easier to understand. (33) One distributor commented that traditional annuities are only sold to customers for which banksparen for regulatory reasons are either not available or unattractive (i.e. for customers who purchased products under the ‘old regime‘ (34)). (35)

59. Other comments on the introduction of banksparen also show that competitors consider them as an almost exact equivalent. One competitor stated for example that “since 2008 banks have been allowed to offer deferred and immediately effective annuities and annuity insurance. Before that this business was exclusively reserved for insurance companies”. (36)

60. When discussing the needs served by the products, a number of competitors also refer to banksparen and life insurance products (in particular annuities and deferred pensions) as being equivalent. (37) The vast majority of competitors confirmed that they consider banksparen to be competing with traditional life insurance policies. A number of respondents also commented that banksparen are preferred by customers as the products are perceived to be safe and transparent. (38)

61. Competitors also point out that, in addition to serving the same fundamental customer need, banksparen also benefit from the same tax treatment as life insurance products. Furthermore, the savings accumulated in a banksparen product are not available for the customer to use at any point they choose, but instead they have to wait until the maturity date of the product. This again is a parallel with insurance products. (39)

62. In conclusion therefore, the Commission notes that banksparen seem to share the same fundamental characteristics and serve the same purpose as savings and investment products provided within individual life insurance, even if there are also some differences in the products.

63. Irrespective of whether banksparen should be considered to form one product market together with traditional insurer’s savings and investment products or not, taking into account the purpose for which the different products are bought, it would appear logical to distinguish within the savings and investment products accumulation products and decumulation products. The reasons for that distinction would be similar to those described above in the context of group pension products.

64. In any event for the purpose of this case, the questions as to whether banksparen forms part of the savings and investment products life insurance market and whether the market should be segmented into accumulation and decumulation products can be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition on these markets under any plausible market definitions resulting from these distinctions.

Annuities (pillar 2 and pillar 3)

65. One area in which there may be a more blurred division between product markets than was previously identified by the Commission is in annuities. Insurers sell annuities both for the decumulation phase of DC pension schemes (i.e. as part of the pillar 2 pension system) and to individuals who have saved up through individual savings and investment products. As with the savings products themselves, the annuity purchased can either be in the traditional life insurance product range, or from the new bank savings products (banksparen), the main difference being that the latter are always time limited (to a maximum of 30 years), whereas the former pay out for the insured party’s full lifetime.

66. From a demand-side perspective, there is no substitutability between pillar 2 and pillar 3 annuities, as regulations prevent customers from using capital saved in one pillar to buy an annuity in the other.

67. From a supply-side perspective, however, the products are very similar, as both annuities purchased within DC pension schemes and those purchased within individual life insurance involve the provider taking on interest rate and longevity risk. This is less the case for bank annuities, as these are for a fixed term and therefore do not imply any longevity risk. Furthermore, bank annuities are provided under a banking licence, meaning that, even if insurers provide these, this would be through their banking subsidiaries.

68. The Notifying Party acknowledges that any insurance company offering pillar 2 decumulation products could easily offer pillar 3 decumulation products, and most, in practice, already do. It argues, however, on the grounds of the lack of demand- side substitutability, that there should not be considered to be one market comprising pillar 2 and pillar 3 decumulation products.

69. The results of the market investigation were inconclusive as to whether pillar 2 and pillar 3 annuities could form part of the same market due to supply-side substitutability. As mentioned above, the market investigation did, however, confirm that an increasingly large proportion of pillar 3 savings and investment products sold in the Netherlands are banking products, which would limit the supply-side substitutability.

70. For the purpose of this case, the question as to whether pillar 2 and pillar 3 annuities form separate product markets within a hypothetical decumulation market can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition in the area of annuities, irrespective of whether annuities under pillar 2 and pillar 3 are considered to form separate product markets, or to be part of one distinct product market.

Conclusion

71. The market investigation confirmed that the market for life insurance products can be segmented into the following three categories: (i) pension products, (ii) pure protection products, and (ii) savings and investment products. Whether or not a further segmentation is made between group and individual products is ultimately inconsequential, as the first category, pension products, only exists as group products in the Netherlands, while the other two categories only exist as individual products. The market investigation strongly suggested that it would also be appropriate to make a distinction between defined benefit (DB) and defined contribution (DC) pension products, and, within DC pensions, potentially between unit-linked and non-unit-linked products or between accumulation and decumulation products. Within decumulation products, there may also be separate markets for variable and fixed annuities, whilst pillar 2 and pillar 3 annuities may form part of the same product market. As regards pure protection products the Commission will consider overall market comprising all such products and possible segmentation based on categories of risks covered such as term-life insurance or funeral insurance. As regards savings and investment products, the Commission will consider overall market comprising all these products, including banksparen or not, and potentially segmented into accumulation and decumulation products. For the purpose of this case, the market definition can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition under any of these market definitions.

III.2.B. Non-life insurance

72. In past decisions, the Commission observed that, from a demand-side perspective, the market for non-life insurance could be segmented into as many product markets as there are different types of risks insured and that, from a supply-side perspective, the conditions for insurance of the different types of risks are quite similar and most large non-life insurers are active in several types of risk coverage. (40)

73. The Commission usually considers a distinction between: (i) accident and sickness, (ii) motor vehicle, (iii) property, (iv) liability, (v) marine, aviation and transport (MAT), (vi) credit and suretyship and (vii) travel insurance (41) but has to date left the exact market definition for non-life insurance products open. The Commission has also considered several alternative hypothetical segmentations for the non-life insurance market, distinguishing for instance fire insurance (42) or legal assistance (43). In certain decisions, the Commission also considered separate product markets according to the applicable national insurance classification. (44) A further distinction could also be made between individual and group customers.

74. The Notifying Party considers the relevant market to be the overall market for non- life insurance.

75. The results of the market investigation show that insurers typically make a distinction between property and casualty insurance on the one hand, and group disability and sick leave on the other (with health insurance also potentially within the latter category, but outside the scope of this case as there is no overlap between the Parties’ activities in this area). The large insurers typically offer products across both these broad categories, but many smaller companies are more specialised, offering only, for example, property and casualty insurance, or only insurance to commercial clients (and not to individuals). In general, the market investigation did not provide any evidence to justify departing from the past Commission practice of considering separate markets for the various insurance products insuring different risks.

76. For the purpose of this case, the product market definition can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition with respect to non-life insurance, irrespective of whether products insuring different risks (e.g. travel insurance, disability insurance etc.) are considered to each form a separate product market or to together form one broader market, and irrespective of whether non-life insurance for groups and for individuals are considered to form one or separate product markets.

77. As regards the geographic market definition, in previous decisions relating to non- life insurance the Commission considered that the markets are likely to be national with the exception of certain segments, such as insurance for large commercial, industrial or environmental risks, marine, aviation and transport insurance or aerospace insurance, which are likely to be wider than national for large group customers. (45) Neither of the Parties provides insurance in these segments. For the purpose of this case, the non-life insurance market can therefore be considered to be national.

III.2.C. Pensions administration

78. In a previous case, the Commission considered that there exist separate product markets for retirement benefits consulting and pensions administration. (46) Pensions administration was defined as providing of facilities to allow scheme members to access their fund balances and to perform certain operations via, for example, websites.

79. The Commission considered that the geographic market for pensions administration could be national, as the nature of pensions administration systems is determined to a large extent by national regulatory frameworks and other national legislation, e.g. on social security and tax. The Commission considered also that the market could have some international characteristics. Ultimately the exact geographic market definition was left open. (47)

80. The Notifying Party does not contend the Commission’s past practice, nor propose any alternative segmentation. The market investigation similarly did not present any reason to depart from past practice.

81. In any event, for the purpose of this case, the market definition can be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition under any plausible market definitions mentioned above.

III.2.D. Provision of insurance to pension funds

82. A market limited to the provision of insurance to pension funds has not previously been considered by the Commission, while it would appear to be relevant in this case.

83. Dutch pension funds (48) typically source a range of services from external providers, either, as is the case for insurance, because they are not licensed to perform the activity themselves, or, because they do not have the necessary expertise in-house. The main services they require are asset management, fiduciary management, pensions administration and insurance.

84. There have historically been a number of different types of insurance scheme used for outsourcing risk from pension funds. These vary in terms of, firstly, whether the whole pension contract is insured, or only specific risks (e.g. mortality or disability risk), and, secondly, in terms of the length of the contract – whether it is for a fixed or an indefinite period. Legislation introduced in 2012 in the Netherlands means that schemes insuring mortality and disability risks for a specific period can no longer be offered, but the other types of contract are still used. (49)

85. The relevant geographic market for the provision of insurance to pension funds would appear to be national, due to the presence of national legislation related to for example eligibility of various suppliers to provide certain categories of pension products (e.g. DB or DC schemes, decumulation products), existence of mandatory industry pension schemes or even to licensing of distributors and the procedures for carrying out tenders. Furthermore, the market appears to be national in scope due to the importance of expertise in assessing risks related to pension funds, which is necessary for the correct pricing of insurance offered. In addition, national providers account for at least 95% of the market, which would appear to confirm this hypothesis. The Notifying Party, however, contends that certain types of insurance (in particular for longevity risk) can be sourced on an international market. Whilst this may be true, this particular type of insurance would appear to represent a very minimal part of the insurance sourced by Dutch pension funds.

86. For the purpose of this case, the market definition can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition, irrespective of whether the market for providing insurance to pension funds is considered to be a distinct product market, or to form part of the wider market for all insurance services and irrespective of whether the market is national or wider in scope.

III.2.E. Buy-outs

87. Buy-outs of pension schemes have traditionally been the main way for a pension fund to transfer its liabilities to an insurer. When a company or other provider of a pension fund is either no longer able or no longer wishes to bear the longevity and investment risk associated with the pension fund, it can choose to transfer the obligations to an insurer.

88. In previous cases, when considering the market for buy-outs, the Commission identified two main types of de-risking transactions which take place in relation to DB pension schemes: i) longevity swaps, whereby a pension scheme can hedge the longevity risk, and ii) bulk annuity contracts, whereby all the risk associated with the pension liabilities is transferred. (50) Within bulk annuity contracts a further distinction has been considered between buy-in and buy-out transactions. Under a buy-in transaction, the ultimate liability for the benefit payments remains with the pension scheme trustees, who hold the policy as an asset and remain responsible for paying the pensions. Under a buy-out transaction, meanwhile, the assets and liabilities of the entire scheme are transferred to the insurer.

89. The Commission concluded that longevity swaps and bulk annuity contracts should be considered to constitute distinct product markets, but left the question open as to whether there are separate markets for buy-in and buy-out transactions (within bulk annuity contracts). (51)

90. The Notifying Party submits that it is not aware of any buy-ins having taken place on the Dutch pensions market. The relevant market for the purpose of this case would therefore comprise the market for bulk annuity contracts, potentially limited to buy-out transactions.

91. In previous cases the Commission considered that the market for bulk annuity contracts is national in scope. (52) The Notifying Party does not challenge this assumption and the market investigation also did not provide any grounds to consider other possible geographic market definitions.

92. For the purpose of this case, the market definition can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition with respect to buy-outs, irrespective of whether buy-outs are considered to form a distinct market, to be part of a market for bulk annuity contracts or to be part of a wider market for de-risking transactions (including both bulk annuity transfers and longevity swaps).

III.2.F. Insurance distribution

93. In previous cases, the Commission has considered the existence of a downstream market for insurance distribution that involves the procurement of insurance cover for individuals and group customers (i.e. companies), through any one of a number of possible channels, including direct sales, tied agents and intermediaries such as brokers and banks. (53)

94. The Commission has discussed whether the market for insurance distribution comprises only outward distribution channels (i.e. non-owned and third party distributors such as brokers and agents) or whether it should also be considered to include the sales force and office networks of the insurer (i.e. direct sales). This question has, however, always been left open. (54)

95. The Commission has also considered whether a distinction could be made between the distribution of life and non-life products due to differences in the regulatory regimes and the fact that different actors are involved in the distribution of life and non-life insurance. Again, this question has always been left open.(55)

96. The information provided by the Notifying Party demonstrate that in the Netherlands the distribution channels for pension products are entirely distinct from those for (individual) life and non-life insurance, as only intermediaries holding a specific regulatory licence are able to distribute pension products to companies. These are usually actuarial or other consulting firms. No direct distribution takes place for pension products. The market for the distribution of pension products would consequently be restricted to outward channels, as 100% of pension products are distributed via intermediaries. It is, however, possible for an insurer to be present on this market via a subsidiary that has the required licence, as is the case for NN and its wholly owned subsidiary Zicht B.V. (Zicht).

97. Life and non-life insurance products, meanwhile, can be distributed via banks, brokers and other intermediaries, as well as via direct sales. The specific intermediaries involved in the distribution of life and non-life insurance respectively also vary to some extent. Whilst banks and brokers operating via online platforms typically offer both life and non-life insurance, more specialised intermediaries also play an important role on the distribution market. These include intermediaries who advise individual clients on the purchase of annuities and also risk consulting firms, which typically advise businesses on non-life insurance. In terms of the actors present on the market, there is therefore some differentiation according to both the type of the policy (life or non-life) and the customer (group or individual). Nonetheless, there is not the same regulatory restriction for distribution of these products as applies for pension products.

98. In view of the above, the Commission considers that it is likely that there is a separate product market for the distribution of pension products. There may also be separate markets for the distribution of group non-life insurance (in part as this is very often sold together with pensions) and for the distribution of individual life insurance, although this is less certain. Furthermore, a hypothetical market for the distribution of pension products would be de facto restricted to outward channels, as mentioned above. (56) The hypothetical markets for the distribution of life and non-life insurance respectively could include only outward distribution channels, or could include both outward and inward channels, as contemplated in the previous decisions of the Commission.

99. The Commission has always left the geographic market definition of insurance distribution open, while recognising the national nature of insurance distribution channels. (57)

100. The Notifying Party considers the Dutch insurance industry and its further product segments to constitute national geographic markets, including for insurance distribution.

101. The presence of extensive national regulation on distribution of different types of insurance product in the Netherlands would seem to support the assumption that distribution is a national market. The market investigation did not provide any evidence to the contrary.

102. For the purpose of this case, the product market definition can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition in the area of insurance distribution, irrespective of whether the insurance distribution market is considered to constitute one broad market, or whether separate product markets are envisaged for the distribution of different types of insurance, according to the type of insurance and/or the type of customer.

III.2.G. Reinsurance

103. Reinsurance consists in providing insurance cover to another insurer for some or all of the liabilities assumed under its insurance policies, in order to transfer risk from the insurer to the reinsurer. (58)

104. In previous decisions, the Commission distinguished the market for reinsurance from those for life insurance and non-life insurance, defining reinsurance services as the provision of insurance cover to another party for part or all of the liability assumed by it under an insurance policy it has issued. (59) It left open, however, whether a further distinction should be made between reinsurance for the life and non-life segments respectively, and whether, within the non-life segment, further segmentation according to the class of risk should be considered. (60)

105. The Commission has previously considered the market for reinsurance to be global due to the need to pool risks on a worldwide basis. (61)

106. The Notifying Party does not propose any alternative product or geographic markets. The market investigation similarly did not present any reason to depart from past practice.

107. For the purpose of this case, the product market definition can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition in the area of reinsurance, irrespective of whether the reinsurance market is considered to form one product market, or whether reinsurance for life and non-life insurance or for different risks are considered to constitute separate markets.

III.2.H. Asset management

108. In past cases, the Commission has described asset management as the provision and potential implementation of investment advice. It was considered that it may also include the creation and managing of mutual funds which are then marketed on an “off-the-shelf” basis, including to retail customers, the provision of portfolio management services to institutional investors (pension funds, institutions and international organisations), and the provision of custody services related to asset management.

109. The Commission considered the possibility of there being a relevant product market for asset management, which would include the creation and management of mutual funds for retail clients and tailor-made funds for corporate and institutional customers, and portfolio management for private investors, pension funds and institutions. (62)

110. The Commission further considered the possible existence of separate relevant product markets for each of the types of products mentioned above. (63) In previous cases, the Commission has judged that asset management services for private individuals should be considered to be distinct from other asset management services (as they often form part of retail banking). (64) With regard to the other potential narrower markets within asset management (such as a market for custody services), the Commission has, however, always left the market definition open. (65)

111. The Notifying Party does not propose any alternative product markets and the market investigation did not suggest that there would be any reason to depart from past practice.

112. The relevant geographic market for asset management (or any narrower hypothetical market within asset management) has previously been considered to be either national or EEA wide. (66) The Commission has deemed it likely that at least some parts of the asset management market are wider than national, in particular as regards institutional clients. (67)

113. The Notifying Party considers the market for asset management to be at least EEA- wide, on the basis that competition between financial institutions that offer asset management takes place at a wider than national level.

114. The market investigation did not provide conclusive evidence as to whether the market for asset management should be considered to be national or EEA wide.

115. For the purpose of this case, the market definition can, in any event, be left open, as the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition on the market for asset management under any plausible market definition as previously considered by the Commission.

IV. PENSION PROVIDERS IN THE NETHERLANDS

116. Further to the above section on market definition (section III) and by way of introduction to the competitive assessment (section I), the Commission considers it useful to provide a short and general description of the various types of pension product providers in the Netherlands. This background information will help to illustrate the Parties’ position as insurance companies vis-à-vis the other types of pension providers active in the Netherlands, which the Notifying Party believes to exert competitive pressure on the Parties. The following section also highlights the recent regulatory changes introduced in the Netherlands that have allowed new types of pension providers to enter the market.

IV.1. Introduction

117. The Dutch pensions market is characterised by the presence of a wide range of providers who serve, to some extent, different parts of the market. Insurers, such as NN and Delta Lloyd, between them account for no more than 14% (68) of regular premiums paid into all Dutch pension schemes and funds. A large part of the Dutch pension market (i.e. pillar 2, the market for supplementary collective employer- based pensions) has traditionally been served by compulsory industry pension funds (bedrijfstakpensioenfonds, BPFs) and company pension funds (ondernemingspensioenfonds, OPFs), which together account for around 85% of the premiums paid on the Dutch pensions market.

118. The 14% of the pensions market occupied by insurers is in the hands of six main players (in order of market share): Aegon, NN, Delta Lloyd, ASR, Vivat and Achmea.

119. The Dutch pensions market has seen a number of significant changes in recent years, some of which are typical of the current economic environment and can be seen as part of wider international trends, and others of which are more specific to the Netherlands. As in many other countries, the Netherlands is seeing a gradual shift from defined benefit (DB) to defined contribution (DC) pension schemes. Changing demographics have made it increasingly difficult to fund DB schemes, and in recent years this has been further exacerbated by persistent low interest rates. Changes more specific to the Netherlands include in particular the introduction of two new pension vehicles: premiepensioeninstellingen (PPIs) in 2011 and more recently algemeen pensioenfondsen (APFs) in 2016. Insurers such as NN and Delta Lloyd are both active as providers of these new types of pension arrangement, via their respective PPIs and APFs they have set up. In these areas however the Parties compete also with a wider field of competitors The Parties’ PPIs, for example, are competing not only with the PPIs set up by other insurance companies but also with PPIs set up by asset managers and banks. In addition, the number of company pension funds (OPFs) has decreased dramatically in recent years and is expected to fall further, primarily due to the difficulty of maintaining these schemes in the face of new stricter regulation on solvency and administration. These changes will be discussed in more detail in the sections which follow, in particular insofar as they have implications for the competitive assessment.

120. The following sections provide a brief description of the different actors present on the Dutch pensions market, the products they offer and their typical customers.

IV.2. Bedrijfstakpensioenfondsen (BPFs)

121. BPFs are industry pension funds that serve a particular sector of the economy. The sectors covered by BPFs include, for example, construction, retail stores and health and welfare. There are currently 63 BPFs active in the Netherlands, which together account for around 64% of the Dutch pensions market.

122. BPFs were originally set up as a mandatory arrangement for certain industries, and employers for whom membership is obligatory and who still make up the vast majority of their membership (98% of premiums). Mandatory participation for an employer means that all individual employees are obliged to be members of the fund. All members of a BPF are subject to the same terms and conditions, meaning that they pay the same fixed level of contributions for the same level of benefits.

123. More recently, many BPFs have opened up their membership to other employers within their sector or in neighbouring sectors. These employers can join a BPF on the same terms and conditions as those for whom membership is mandatory.

124. There are also nine BPFs which have been set up on the basis of voluntary membership alone. These are also, however, sector specific, and include, for example, funds for the plastic and rubber industry, the dairy and related industry and public transport.

125. The vast majority of BPFs (over 99% based on 2015 regular premiums) operate defined benefit (DB) schemes. It follows that individual members of BPFs typically remain in the BPF during both the accumulation and the decumulation phase, i.e. their pension is paid out directly from the BPF, at the level set by the BPF’s terms and conditions at that point in time, and there is no possibility of shopping around for an annuity.

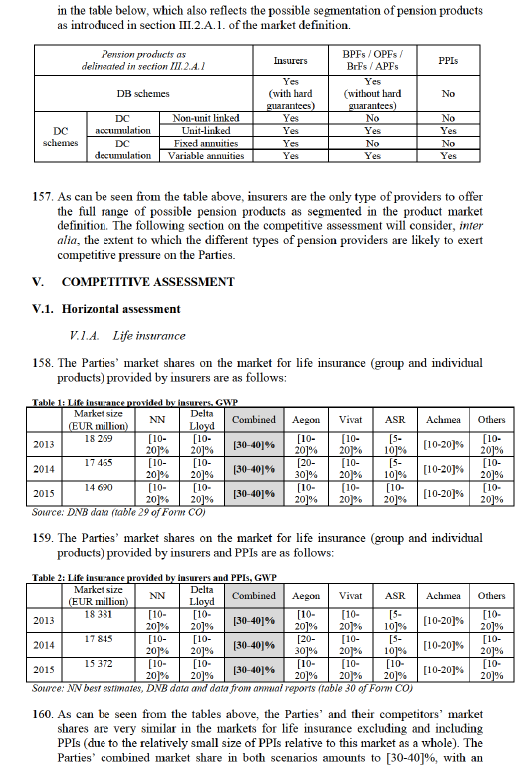

126. BPFs are regulated by the Dutch central bank (DNB), and are required to maintain certain minimum levels of coverage for their liabilities. Should a fund’s coverage ratio fall below the prescribed threshold, the board of the BPF is required to submit a recovery plan to the DNB, setting out how it will increase funding to the required level. This will normally involve increasing contributions, and, in more extreme cases, potentially also cutting pensions. Any decisions require the agreement of the representatives of the members, however, and it can therefore be difficult to obtain approval for such changes. Therefore, BPFs’ DB schemes are unlike those of insurers in that pension schemes offered by BPFs do not involve any guarantee element (other than pooling risk within the scheme and the scheme’s commitment to attempt to deliver the benefit as originally defined) whereas those offered by insurers guarantee the agreed levels of benefits (and these guarantees are backed with insurers capital, protected by solvency requirements).

127. Employers who join a BPF on a voluntary basis would typically transfer their historic assets and liabilities into the pension fund. These employers may have previously had a pension scheme with an insurer or may have had a company pension fund (OPF). As such, BPFs are one of the options open to OPFs which can no longer continue to operate independently.

128. In order to join a BPF, the historic scheme being transferred in needs to meet certain requirements, and the employer is also required to agree to the terms and conditions of the BPF as they stand. In some cases this may mean that pension funds have to make an additional payment as a way of improving the coverage ratio of the assets and liabilities being transferred into the BPF.

129. Whilst OPFs (see section IV.4) that are struggling to survive often look to join a BPF, the smaller BPFs are also facing similar problems. Stricter capital requirements and increased regulation have made it increasingly difficult for smaller BPFs to operate in a cost-effective way, in particular due to higher administrative costs. This has led to a number of smaller BPFs merging. (69)

IV.3. Beroepspensioenfondsen (BrFs)

130. Beroepspensioenfondsen (BrFs) are pension funds that serve individuals in a number of specific professions, which are generally exercised independently, e.g. veterinarians and general practitioners. Participation in the BPF for their profession is usually mandatory for registered professionals. There are 11 BrFs in the Netherlands, each for a specific profession or sector, which together represent approximately 1.5% of the Dutch pensions market (measured on the basis of gross written premium (GWP) in 2015). The vast majority (90%, on the basis of 2015 GWP)) of BrFs are DB schemes.

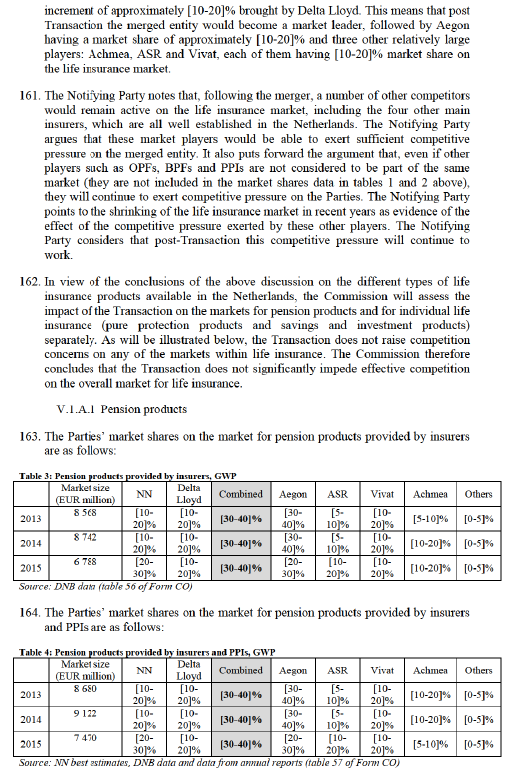

131. Contrary to insurers, pension schemes offered by BrFs cannot entail any guarantee element. For instance, DB pension benefits offered by BrFs can be reduced or no longer indexed if the scheme is underfunded and DC offered by BrFs schemes are necessarily unit-linked.

132. BrFs will not be discussed further in this decision as their activities can be considered to be totally distinct from those of other pension providers. Membership of the BrF is obligatory for the profession in question, and not open to any other firms or individuals, meaning that there can in no way be considered to be competition between BrFs and insurers, or any other pension provider.

IV.4. Ondernemingspensioenfondsen (OPFs)

133. OPFs are company pension funds set up by an individual employer for its employees. There are currently 293 OPFs (70) active in the Netherlands, and it is typically large corporations which would choose to set up an OPF. Philips, Shell and KLM, for example, all have their own pension funds. OPFs account for around 20% of the Dutch pensions market (based on GWP in 2015).

134. Similarly to BPFs, the vast majority of OPFs (97% based on GWP) operate as DB schemes. A minority of OPFs (3%) operate DC schemes. (71)

135. Contrary to insurers, products offered by OPFs do not involve any guarantee element (other than pooling risk within the scheme and the scheme’s commitment to attempt to deliver the benefit as originally defined) whereas products offered by insurers guarantee the agreed levels of benefits (and these guarantees are backed with insurers capital, protected by solvency requirements). DC schemes offered by OPFs are necessarily unit-linked.

136. In recent years, there has been significant consolidation amongst OPFs, affecting in particular the smaller funds. Stricter regulations on solvency and capital requirements, together with low interest rates on government bonds and demographic developments, have made it increasingly difficult for small OPFs to continue to operate independently, as was confirmed by OPFs contacted during the market investigation. In addition, regulation on the management of OPFs has become more onerous, requiring considerably more monitoring and reporting. For small OPFs that do not have the expertise necessary to meet these requirements in house, it has become very difficult to absorb these increased operating costs. Many OPFs have therefore either merged, or closed and transferred their historic assets and liabilities to another provider. OPFs in this situation are most often either bought out by an insurer (see sections III.2.E andV.1.F on buy-outs), with which they may then also enter into a contract for future accrual, or join a BPF, into which they also transfer their historic assets and liabilities. Since the launch of algemeen pensioenfondsen (APFs) (see section IV.7 below) in January 2016, OPFs have another alternative, as they can either join an existing APF or set up their own APF.

137. The different options available to an OPF have different implications for the scheme’s members: a buy-out by an insurer means that the members are then guaranteed a fixed level of pension benefit, whereas under an APF or a BPF, the benefits could be cut (in the same way as was the case in the OPF). A buy-out by an insurer is therefore typically more expensive for an OPF than joining an APF or a BPF. APFs and BPFs have their own requirements for entry, and an OPF may therefore have to pay an additional premium, for example, if its coverage level is below that of the other funds in the APF or in the BPF, respectively.

IV.5. Insurance companies

138. In the Netherlands, insurance companies have traditionally served employers in all industries where membership of an industry pension fund (BPF) is not obligatory. The five sectors in which NN achieves its highest revenue are vehicle repair, industry, financial institutions, advisory and research services and business services. As discussed in the section III.2.A.1, insurers usually offer DB and DC pension schemes.

139. The DB schemes offered by insurers could be regarded as DB pensions in a stricter sense than those provided by BPFs and OPFs. The insurance company is contracted to provide a guaranteed level of benefit (usually defined as a percentage of the member’s average salary, based on the number of years’ employment). The level of benefits and contributions are determined by the insurance company using actuarial calculations but if, for example, investments perform less well than expected, or interest rates move such that the present value of liabilities increases relative to the present value of assets, the insurance company effectively covers the shortfall. It cannot increase contributions or reduce benefits to cover the loss (although it can of course offer less favourable terms for future years when the contract comes up for renewal). For this reason, insurance companies are required by solvency regulation to hold a certain level of capital in respect of DB arrangements.

140. The DC schemes offered by insurers are now mainly unit-linked policies, which involve each individual member paying contributions in order to accumulate their own ‘pension pot’, which is then used to purchase an annuity. PPIs (see section IV.6 below) offer very similar DC arrangements for the accumulation phase but (as explained above in section III.2.A.1on product market definition) are much more restricted in the products they can offer members on retirement. Specifically, only insurers can offer fixed annuities as the provider of such products is taking on longevity and interest rate risk, which needs to be backed by a certain level of capital. Similarly to for DB schemes, only providers licensed as insurers and subject to solvency regulation are therefore allowed to carry out these activities.

141. In view of the above, insurers’ activities therefore differ from those of other actors, in part because they serve a different client base (72), and in part because at least some of the products they offer are different in nature than those of other providers.

IV.6. Premiepensioeninstellingen (PPIs)

142. PPIs are a relatively new type of pension institution that became active on the Dutch market in January 2011. They can serve all industries apart from those where participation in a BPF is mandatory. PPIs only offer DC pensions as they are not licensed to carry the risk involved in running a DB pension scheme. There are currently ten PPIs active on the Dutch pensions market, including Nationale- Nederlanden Premium Pension Institution B.V. set up by NN and BeFrank PPI N.V. set up by Delta Lloyd.

143. PPIs were originally only able to provide the accumulation phase of a DC arrangement, but since July 2016 they can also offer decumulation products, but only in the form of variable annuities. (They are not able to offer fixed annuities, as these would, again, involve bearing longevity and interest rate risk.) PPIs do, however, act as distributors of fixed annuities offered by other providers.

144. A PPI that has been set up by a party other than an insurer may not have all the expertise and/or resources in-house, and so is likely to outsource certain parts of the value chain, in particular asset management and pension administration. A PPI would also typically need to reinsure any additional risks that have been included in the package offered to pension customers, such as survivors’ pensions and disability insurance. The need for these different services means that a single PPI often involves the participation of a range of companies, which can each provide different expertise, e.g. an asset manager, a pensions administration company, a bank and an insurer. In this way, PPIs could be seen as having contributed to the ‘unbundling’ of pension provision.

IV.7. Algemeen pensioenfondsen (APFs)

145. The first APFs became active in 2016, and there are currently seven providers that have obtained regulatory approval from the Dutch central bank (DNB) including De Nationale APF set up by NN and the Delta Lloyd APF. There is thought to be one further APF in the process of being set up, for which a request for authorisation has not yet been submitted to DNB (according to market intelligence available at the time of writing).

146. An APF is a type of pension vehicle which operates a number of collective pension schemes. An APF is structured as a number of ‘circles’, each of which contains one or more pension funds. The pension funds within each circle all carry the risk of that circle collectively, but do not share risk with pension funds in other circles. As a result, investment of the pension fund assets is also carried out at ‘circle-level’.

147. An APF can operate both DB and DC circles (the two types of pension product would never be combined in the same circle), but to date most providers have set up DB circles. Only two providers, one of which is NN, offer DC circles. An employer or other pension fund wishing to join an APF typically has the choice between a number of different circles with different characteristics, in terms of premiums, investment strategy (i.e. the level of risk) and the coverage level. Alternatively, it could create its own circle, thus keeping more control over the style of the pension fund. This option would typically be of interest to larger pension funds or employers.

148. An APF can outsource various activities involved in the running of a pension scheme (including asset management, administration, fiduciary management and reinsurance). One of the main attractions of an APF for customers is that it allows pension funds to achieve economies of scale as they share these services with the other pension funds in their circle. Although an APF can theoretically outsource activities such as asset management and pensions' administration to any provider, in practice, almost all APFs have been set up by insurers, with the insurer providing these services. APFs could be seen as being simply a different business model for insurers, i.e. rather than providing pensions' administration and asset management directly to an employer as part of the contract for a pension scheme, the insurer gains this business via its own APF. As such, the different activities involved in providing a pension scheme have been technically unbundled, but are in most cases all still performed by the same small group of insurers.

149. Each of the circles within an APF is subject to the same solvency framework as individual pension funds. The APF itself is also required to hold 0.3% (or 0.2% when certain risks are insured) of assets under management as a buffer, with a minimum of EUR 0.5 million.

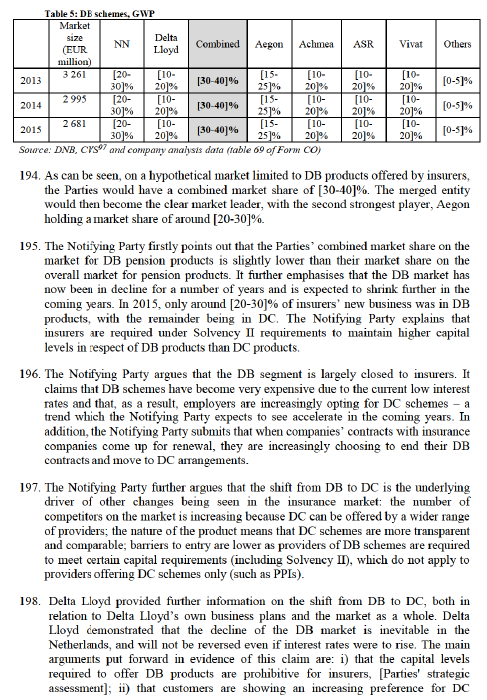

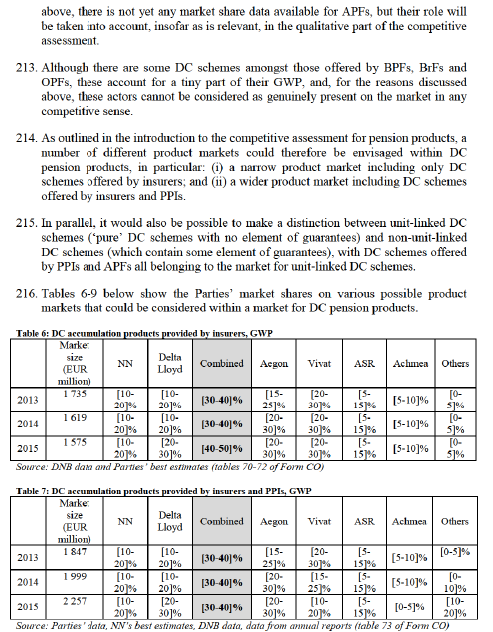

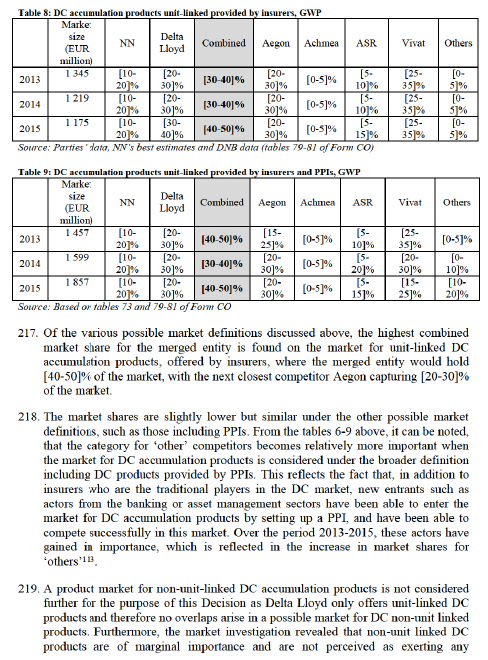

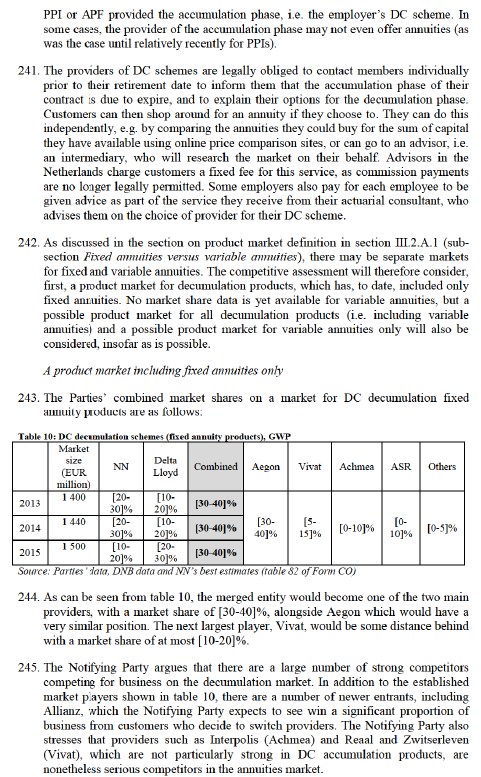

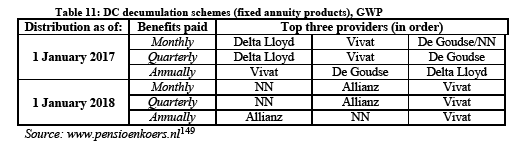

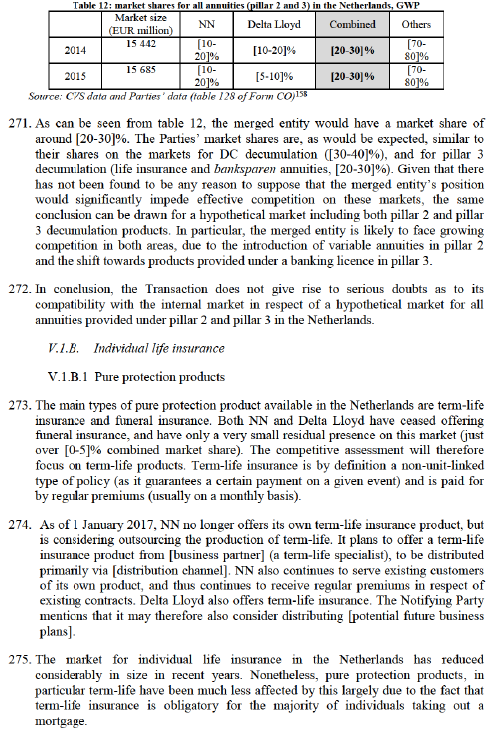

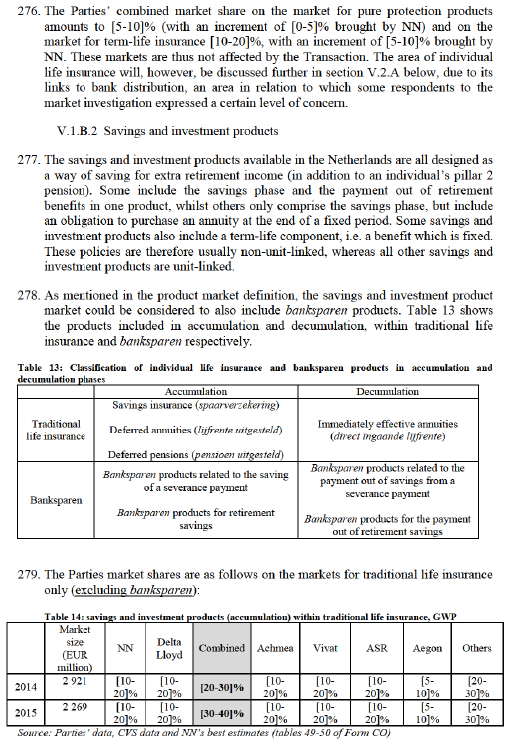

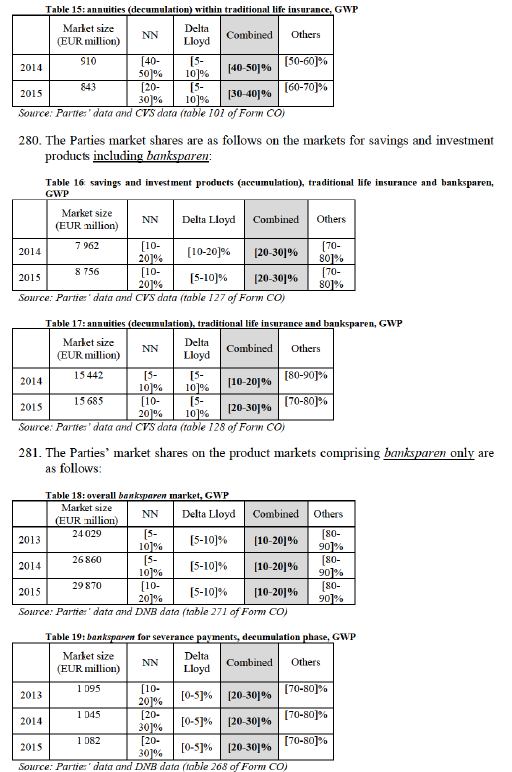

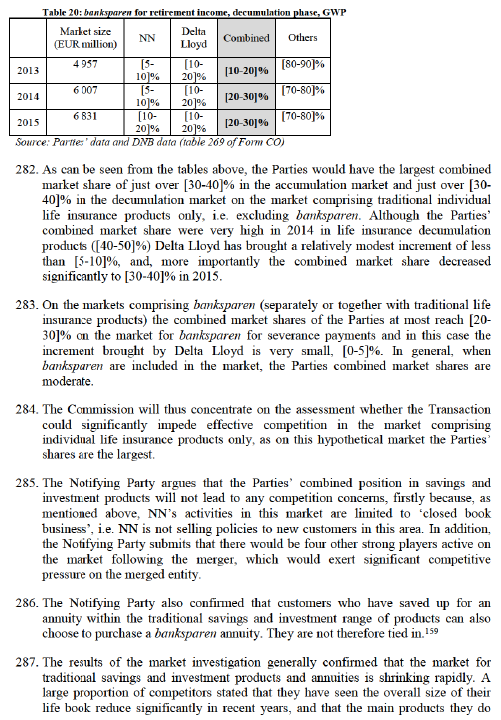

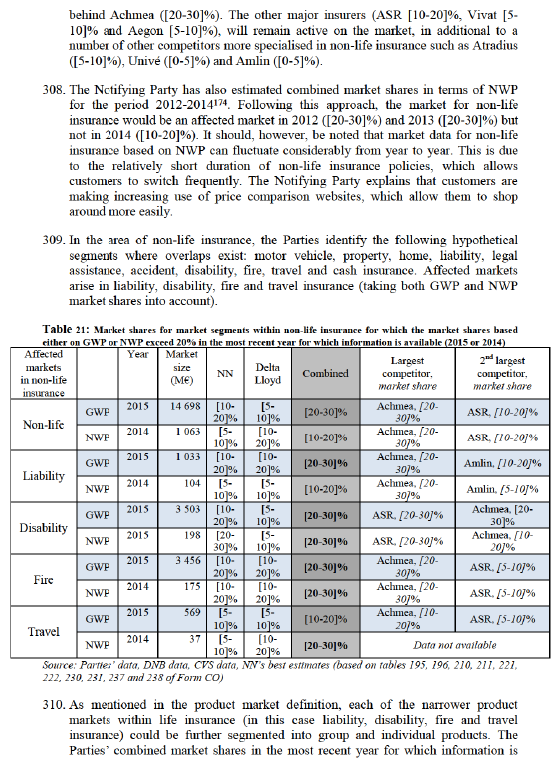

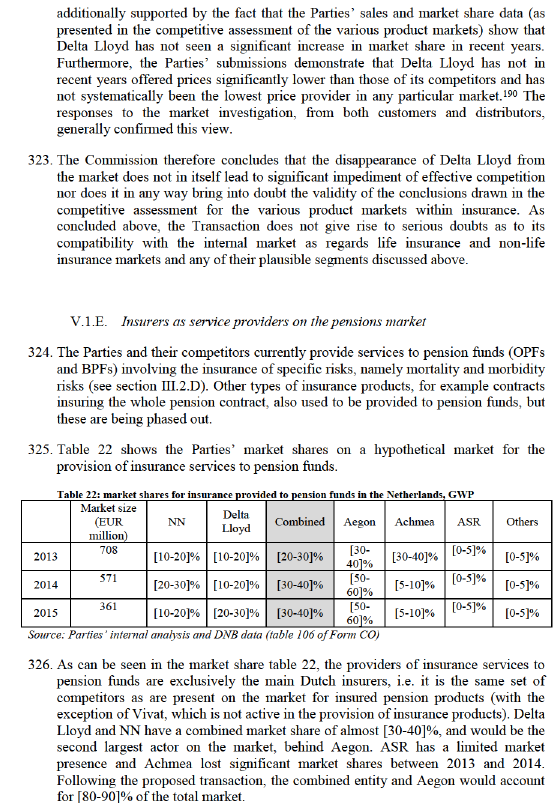

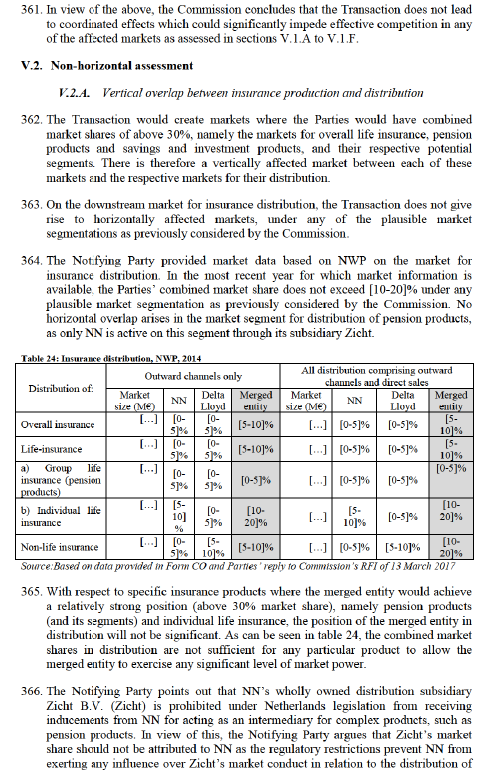

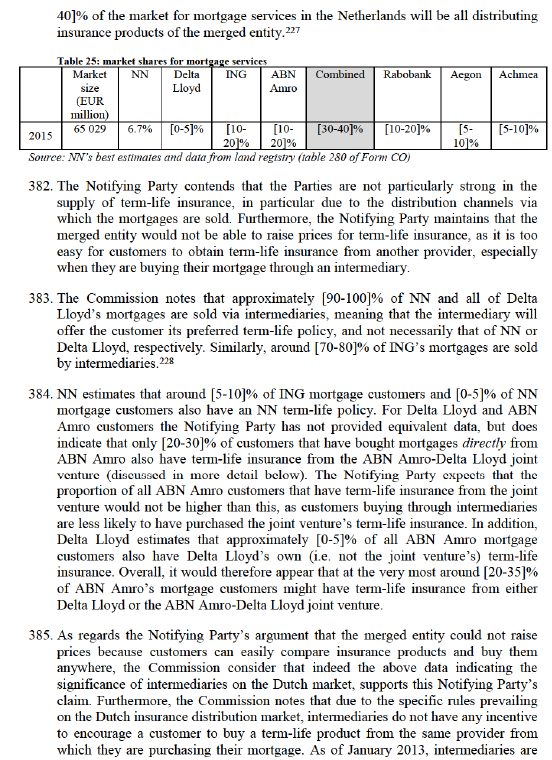

150. APFs can be set up by pension funds, insurers, pensions' administration organisations, banks and asset management companies. To date, of the seven APFs which have obtained approval from the DNB, all but one (73) have involved the participation of an insurer or (in one case) a pension provider. In addition to the Parties, the following companies have gained approval for APFs: Achmea (Centraal Beheer), TKP (74)/Aegon (Stap), PPGM (Volo), ASR (Het Nederlandse Pensioenfonds) and Unilever (Progress and Forward).