Commission, November 17, 2017, No M.8522

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

AVANTOR / VWR

Subject: Case M.8522 - Avantor / VWR

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/2004 (1) and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (2)

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 11 October 2017 (3), the Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 by which Avantor, Inc. ("Avantor", USA), controlled by New Mountain Capital, LLC ("New Mountain", USA), acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation control of the whole of VWR Corporation ("VWR", USA), by way of a purchase of shares. Avantor is designated hereinafter as the Notifying Party and Avantor and VWR together as the Parties.

1. THE PARTIES

(2) Avantor, a corporation organised under the laws of the State of Delaware (USA), is a global supplier of ultra-high purity materials for the life sciences and advanced technology sectors, including laboratory chemicals. It supplies products for use in production and research, to customers in a range of sectors including biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, diagnostics, aerospace and defence, and semiconductors. Avantor is controlled by New Mountain (4), an investment firm that manages private equity, public equity and credit funds. Its portfolio companies are active in a range of sectors including healthcare and healthcare services, pharmaceuticals, technology services, clothing, logistics and shipping.

(3) VWR, a publicly traded company listed on the Nasdaq Stock Market, is a global distributor of laboratory products and services. It distributes chemicals, reagents, consumables, durable products and scientific equipment and instruments, and offers both branded and private label products. VWR is also active in the manufacture of bioscience products and laboratory chemicals, both for its own private label and for other suppliers.

2. THE OPERATION

(4) On 4 May 2017 Avantor and VWR entered into an agreement under which Avantor will acquire the whole of VWR for USD 33.25 in cash per share of VWR common stock, reflecting an enterprise value of approximately $6.4 billion (the "Transaction"). Because Avantor is indirectly solely controlled by New Mountain, following the Transaction, New Mountain will indirectly control VWR.

(5) As a result of the Transaction, VWR will become a wholly-owned subsidiary of Avantor. The Board of VWR will consist of a Chief Executive Officer and ten other board members. New Mountain will be entitled to appoint the Chief Executive Officer and seven (or at least five) (5) of the other board members, thus allowing it to exercise sole control of VWR.

(6) In view of the above, New Mountain will acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control over VWR as a result of the Transaction.

3. EU DIMENSION

(7) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (6) (EUR […]). Each of them has EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (New Mountain: EUR […] million; VWR: EUR […] million), but neither achieves more than two-thirds of its aggregate EU-wide turnover within one and the same Member State. The notified operation therefore has an EU dimension pursuant to Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. MARKET DEFINITIONS

4.1. Introduction

(8) Avantor is a supplier of ultra-high purity materials for the life sciences and advanced technology sectors. It is active globally and across the EEA and has a particularly strong presence in the US, where it is based.

(9) VWR is both a manufacturer and a distributor of laboratory and bioscience products and also provides various laboratory services. Similarly to Avantor, VWR is active globally and across the EEA. It is a particularly strong player in the western European markets.

(10) The Parties' activities overlap in relation to the production of three main types of life science product: bioscience products, raw materials for (bio)pharmaceutical production, and laboratory chemicals. The Transaction, however, only creates horizontally affected markets in one of these areas: laboratory chemicals.

(11) The Transaction also creates a vertical relationship, due to the link between VWR's activities as a distributor of laboratory chemicals and both Parties' presence on the upstream (production) market(s) for laboratory chemicals. VWR is currently a distributor for Avantor, meaning that the Transaction internalises an existing vertical relationship.

(12) For the purposes of this decision, any references made to life sciences products, laboratory chemicals and laboratory products are to be understood as follows: i) "life sciences products" denotes products used in bioscience (such as genomics, proteomics, and molecular biology) as well as cell culture products and other raw materials for (bio)pharmaceutical production (both biopharma and small molecule), and including laboratory chemicals; ii) "laboratory chemicals" denotes chemicals that are used for research, analytical testing and quality control purposes in a laboratory setting; iii) "laboratory products" denotes laboratory instruments, consumables and equipment in addition to laboratory chemicals.

4.2. Production of laboratory chemicals

(13) The Commission most recently assessed the market for laboratory chemicals in case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich. Laboratory chemicals were defined as chemicals used for research, testing and quality control purposes. In that case, the Commission considered six main categories of laboratory chemicals ((i) solvents, (ii) inorganics, (iii) organics, (iv) standards and reference materials, (v) analytical chromatography, and (vi) industrial microbiology), and considered the various possible market definitions within each of these categories.

(14) In the present case, the two categories of laboratory chemicals where horizontally affected markets arise are solvents and inorganics. These will each be discussed in more detail below.

4.2.1. Product market definition

(15) The relevant product market for the production of laboratory chemicals is to be defined based on product characteristics that determine demand- and supply side substitutability as well as potential competition. (7) A complainant suggested that a separate market exists that comprises only sales of specific laboratory chemicals to distributors. (8) However, such a limitation would artificially reduce the actual market size because producers of laboratory chemicals can and do sell at the same time directly to final customers as well as via distributors. (9) For the purpose of this case, the Commission does therefore not consider a segmentation of the relevant market by type of customer on the production level. The relevant downstream distribution market is considered separately below. (10)

4.2.1.1. Solvents

(16) In case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, the Commission defined solvents as laboratory chemicals used to dissolve a target substance (a chemically different liquid, solid, or gas). The Commission also observed that solvents can be used either for classical laboratory analysis or for instrumental analysis, and found that separate product markets could therefore be considered for each of these areas, and for sub-segments within these areas.

(17) Within solvents for classical laboratory analysis, narrower classes of products can be identified on the basis of purity: technical grade solvents have lower purity levels than regulated industry grade solvents, which are certified according to published standards. Dried and anhydrous solvents have even higher purity levels and are used in specific processes where very low water content is needed.

(18) Within solvents for instrumental analysis, a distinction can be made according to the technique used. The most common techniques include spectroscopy, electrochemistry, chromatography polymer analysis, capillary gel electrophoresis, gas chromatography, liquid chromatography, and mass spectroscopy.

(19) In case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, the Commission found that the different types of solvents mentioned above are generally not substitutable from a demand-side perspective, due to individual product's specification, level of purity and suitability for use in certain techniques. From a supply-side perspective, however, the Commission found that there was generally a high level of substitutability, as suppliers are generally able to produce a comprehensive range of solvents for both classical and instrumental analysis. The Commission ultimately left the precise product market definition open with respect to solvents and all possible sub-segments thereof.

(20) The Notifying Party agrees with the Commission's findings as to supply-side substitutability in the Commission decision in case M.7435 but submits no further views on the appropriate product market definition for solvents in this case.

Results of the market investigation: demand-side substitutability

(21) The results of the market investigation in the present case generally confirmed the Commission's findings in M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, with the vast majority of customers stating that there is little if any substitutability between the different grades and specific types of solvent. (11) The market investigation explored, in particular, the distinctions between: i) solvents for classical analysis and solvents for instrumental analysis; ii) within solvents for classical analysis: the difference between technical grade, regulated industry grade, and dried and anhydrous solvents; and iii) within solvents for instrumental analysis: the difference between solvents for use in each specific technique (in particular spectroscopy, gas chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis).

Solvents for classical analysis v solvents for instrumental analysis

(22) Solvents can be distinguished by the purpose for which they are used. Solvents that can be used for multi-purpose analyses are typically referred to as "classical analysis" solvents as opposed to specialised solvents for "instrumental analysis" that are designed to be used with certain instruments and techniques such as gas chromatography, liquid chromatography or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy.

(23) Almost all customers confirmed that solvents for classical analysis and solvents for instrumental analysis are used for entirely distinct purposes. One respondent stated, for example: "they are bought for different purposes, we need better quality for instrumental analysis" (12). Other respondents also confirmed that the main difference between the two grades is their purity. A number of customers also mentioned the price difference between solvents for instrumental analysis and solvents for classical analysis, explaining that it would therefore be illogical to use a solvent that is designed for instrumental analysis in classical analysis (even if this would be technically possible). (13)

(24) Customers emphasised that using a solvent of a lower grade in a procedure where the purity is important could jeopardise the results. One stated, for example: "we do not choose to [change between solvents for instrumental analysis and solvents for classical analysis] as the quality of solvents influence the results we provide to customers, mixing grades means for us less reliability". (14)

(25) Furthermore, almost all customers responding to the market investigation stated that they would not switch from solvents for instrumental analysis to solvents for classical analysis if the price of solvents for instrumental analysis were to increase by 5-10%. (15) A small minority would consider switching if there was a very significant increase in price of certain types of solvent, but often mentioned that this would be dependent on the particular product. One customer stated, for example, that the company would only switch "if it is necessary for the company, if it is beneficial and technically compatible". (16) The responses generally confirmed, however, that customers could envisage very few circumstances in which such a switch would be possible.

Solvents for classical analysis: technical grade, regulated industry grade, dried and anhydrous grade solvents

(26) Within solvents for classical analysis, customers also perceived there to be an important distinction between the different grades, namely technical grade (a lower purity product), regulated industry grade (a higher purity product) and dried and anhydrous solvents (a high purity grade for specific uses). (17) The vast majority of responding customers confirmed that technical grade and regulated industry grade solvents are bought for different purposes, according to their specifications. A number of respondents mentioned, for example, that they use technical grade solvents mainly for cleaning, as the purity is not high enough for them to be suitable for use in other areas. One customer explained: "We buy technical grade acetone for washing while analysis grade is used for reactions […] the stabiliser in dichloromethane is different in technical and analysis grade and that can matter in addition to impurities". (18)

(27) Only a very small proportion of customers would consider switching between regulated industry grade and technical grade solvents as a result of a change in price of 5-10%, and of those who would switch, most would only be able to change a limited proportion of their purchases. (19) One respondent explained that "analysis procedures are designed for defined levels of variability, a change in the purity of the solvent could negate this work". (20) Another customer also stressed the impossibility of switching to lower grade solvents: "if our work requires an anhydrous solvent then it would not be possible to swap to a technical grade because the work would not be successful". (21)

Solvents for instrumental analysis: spectroscopy, gas chromatography and HPLC analysis

(28) Considering the different types of solvents for instrumental analysis, responding customers were, again, mainly of the opinion that there was very limited substitutability between their uses. (22) One customer stated, for example "each product is qualified for its intended use. We cannot change without extra qualification". (23) A number of customers did, however, identify examples of circumstances where a solvent sold as being for use in one technique could be used in another. This type of 'crossover' in usage included, for example, using solvents designed for spectroscopy in HPLC and using solvents designed for HPLC in gas chromatography. Views on this varied, however, with some respondents also stating that they would not use spectroscopy or HPLC grades for gas chromatography. (24) Moreover, respondents emphasised that such cases were rather the exception than the rule. One stated, for example "[it would] need to be checked for each individual analysis [...] some types of analysis have specific requirements that are not present in all instrumental grade solvents". (25)

(29) In addition, as was mentioned in relation to the distinction between solvents for classical analysis and solvents for instrumental analysis, price also appears to play a role. It would often be theoretically possible to use a higher quality solvent in a process where a lower grade solvent would be adequate, but customers are unlikely to have any interest in doing this. One customer explained: "spectroscopic grade solvents could often be used for other uses (e.g. HPLC) but this would not be cost effective because it would cost many times more". (26)

Results of the market investigation: supply-side substitutability

(30) From a supply-side perspective, the results of the market investigation were also generally in line with the findings in case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich. The majority of competitors offer a wide range of solvents and the major international manufacturers typically produce solvents of all of the types discussed above (i.e. solvents for both classical and instrumental analysis, and all of the subtypes within each of these two categories). Smaller producers sometimes do not have such an extensive range, but confirm that they could easily start producing those types of solvents which they do not currently offer. (27) Competitors are not aware of any particular type of solvents which would require particular expertise or equipment beyond that necessary for the production of solvents in general. (28) The results of the market investigation therefore appear to confirm that there is a high level of supply-side substitutability between different types of solvent.

High Purity Acetonitrile

(31) The Commission has not previously concluded on possible markets for any specific, individual types of solvent. It considered that HPLC solvents may form a separate product market but left the precise delineation of the market open. (29) During the market investigation for this case, a small number of market participants suggested and expressed concern that the merged entity could have a significant market share in a market for one specific type of HPLC solvent, high purity acetonitrile. (30) VWR (through its subsidiary PTI) is active in the production of bulk size high purity acetonitrile by purifying crude acetonitrile and selling it to competitors of the Parties in the downstream market which down-pack the high purity acetonitrile and resell it under their own respective brands. Avantor is also active in the upstream market by producing catalogue sized high purity acetonitrile on an OEM basis. (31) It produces, packs and labels high purity acetonitrile for competitors downstream. In addition, both VWR and Avantor are also active on the downstream market, selling catalogue sized high purity acetonitrile to distributors and end customers (laboratory customers, (bio)pharmaceutical producers and agricultural chemical manufacturers) under their own respective brands. In order to assess the Parties' activities in this area, the Commission therefore discusses the possible scope of a hypothetical product market for high purity acetonitrile.

(32) The Notifying Party estimates that sales of high purity acetonitrile account for around 50% of all sales of HPLC solvents in the EEA. The Notifying Party submits high purity acetonitrile should be distinguished from standard-grade acetonitrile. The Notifying Party explains that standard-grade acetonitrile is sold in much larger quantities, for use in various types of industrial application, whereas high purity acetonitrile is used by (bio)pharmaceutical and laboratory customers. The acetonitrile captured within the wider product market for HPLC solvents would therefore concern only high purity acetonitrile and not the standard-grade product. Furthermore, the distinction between bulk and catalogue sizes (discussed below in Section 4.2.1.3 for all solvents and inorganics) would apply equally to high purity acetonitrile.

(33) The Notifying Party submits that the three main customer groups purchasing high purity acetonitrile are: i) users of laboratory chemicals, ii) (bio)pharmaceutical manufacturers, and iii) agricultural chemical manufacturers. It further explains that, as a laboratory chemical, high purity acetonitrile is used in various types of instrumental analysis, such as HPLC and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry.

(34) The Notifying Party explains that there are two different processes for purifying acetonitrile: distillation and purification. It submits that purification may provide certain efficiencies as compared to distillation, but that the end product is the same irrespective of which method is used. The Notifying Party further submits that the equipment required and the process followed for distilling acetonitrile is the same as for any other solvent. The Notifying Party claims that any company currently distilling solvents can distil acetonitrile without any special equipment, technology or expertise beyond that required for any other type of HPLC solvent.

(35) The Notifying Party submits that high purity acetonitrile should not be considered to constitute a separate market of its own, but that it should be considered as part of the market for HPLC solvents (or as part of a wider market for solvents, including HPLC solvents).

(36) In their responses to the market investigation, competitors active in the production of crude acetonitrile as a raw material explained that acetonitrile is produced as a co-product of acrylonitrile. (32) The volumes of acetonitrile produced are therefore dependent on decisions regarding acrylonitrile production. (33) Some manufacturers have spare capacity at their current acrylonitrile production plants, (34) but would not necessarily make use of this as a result of any changes on the acetonitrile market, and constructing a new acrylonitrile plant would represent a very significant investment (at least EUR 500 million). (35) The Parties are not active in the production of crude acrylonitrile but both are active purifying crude acetonitrile to higher purity grades.

(37) Competitors’ responses also generally confirmed the distinction made by the Notifying Party between the high purity acetonitrile produced for use in laboratories, and a lower, standard-grade acetonitrile. One manufacturer also explained that it sells crude acetonitrile, which then has to be further purified, and is thus not typically bought by laboratory chemicals suppliers, for whom it is more cost efficient to buy acetonitrile that is already of a sufficiently high purity level to sell to their customers. (36)

(38) Suppliers of high purity acetonitrile to end customers (i.e. competitors to VWR and Avantor on the downstream market) typically source high purity acetonitrile in one of two ways: either they purchase high purity acetonitrile in bulk and repackage it into catalogue sizes, or they purchase the product already in catalogue sizes (and usually already packaged with their brand name), i.e. they contract out the production entirely. (37) Some suppliers use both these options simultaneously, and all respondents confirmed that no specific technology is needed for repackaging acetonitrile different to that used for other laboratory chemicals. (38) Nevertheless, the largest players in the market such as Merck, Honeywell or Thermo Fischer also buy crude acetonitrile and further purify it. (39)

(39) Competitors on the downstream market also confirm that it would not be feasible for them to start producing acetonitrile as a raw material. Most have never considered the idea and do not regard it as realistic for their type of business. The level of investment needed and the time taken to start production is also seen as prohibitive. One supplier mentions that it would be difficult to be competitive in the production of acetonitrile, given that other suppliers produce it as a by-product. (40)

(40) In view of the above, there would seem to be very little supply-side substitutability for the production of crude acetonitrile, as a production plant producing acrylonitrile, of which acetonitrile happens to be a by-product, could not easily switch to producing other solvents, and a producer of other solvents would appear to have to make a significant investment to set up an acrylonitrile production plant.

(41) Nonetheless, there would appear to be supply-side substitutability at the level of production of high purity acetonitrile level. Suppliers that manufacture high purity acetonitrile by further purifying crude acetonitrile confirmed that the process of purification of the crude acetonitrile is not materially different from other solvents.

(42) Moreover, suppliers that do not distil or purify but simply purchase high purity acetonitrile in bulk size to downpack it also confirmed that no specific technology is needed for repackaging high purity acetonitrile as opposed to any other laboratory chemical.

(43) From a demand-side perspective, the same arguments as presented above in the sections on the various types of solvents would strongly suggest that there would only be very limited, if any, substitutability between high purity acetonitrile and other solvents, even other HPLC solvents. At least where a customer has already established a protocol or started a research study using high purity acetonitrile, it would be very difficult to switch to another HPLC (or other) solvent.

(44) For the purposes of this case, the question as to whether high purity acetonitrile constitute a separate product market can be left open, as the Transaction does not lead to competition concerns under any plausible market definition.

Conclusion on market definition for solvents

(45) For the purposes of this case, the exact product market definition for solvents and any sub-segments thereof can, in any case, be left open, as the Transaction does not give rise to competition concerns on these markets under any possible market definition.

4.2.1.2. Inorganics

(46) In case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, the Commission defined inorganics as substances or compounds added to a system in order to bring about a chemical reaction or to see if a reaction occurs. The Commission noted that the primary difference between organic and inorganic compounds is that organic compounds always contain carbon, while most inorganic compounds do not. The Commission also observed that, similarly to solvents, inorganics can be used for classical laboratory analysis and for instrumental analysis. In addition, the category of inorganics also includes a third group of products, auxiliaries, which are ancillary products such as absorbents and drying agents that are used in conjunction with inorganics.

(47) In case M.7435, the Commission found inorganics for classical laboratory analysis to include a number of different types of products, namely acids, bases, buffers, salts, and metals/elements. Each of these types of inorganic is defined by its particular composition and serves a different purpose in laboratory applications, as follows:

a. acids: chemicals that, in aqueous solutions, react with bases to form salts and with most metals (such as iron) to form salts and hydrogen;

b. bases: chemicals that, in aqueous solutions, react with acids to form salts, and promote certain chemical reactions (base catalysis);

c. buffers: aqueous solutions used as a means of keeping pH at a nearly constant value in a wide variety of chemical applications;

d. salts: ionic compounds that are produced as a result of the neutralisation reaction of an acid and a base, used in both qualitative and quantitative analysis of substances and substance mixtures;

e. metals/elements: materials (whether compounds, alloys, or elements) that have high electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity and high density, and that are used for various purposes in research and production.

(48) Inorganics for instrumental analysis can be further categorised on the basis of the purpose for which they are used, e.g. for determining the concentration (volumetric titration solutions), for determining the presence of water (Karl Fischer titration), or for calibration and qualification of analytical instruments.

(49) The Commission found in its market investigation in case M.7435 that inorganics cannot normally be substituted for one another from a demand-side point of view. Each type of organic serves a specific purpose, for which other types would not be suited. There is, however, a large degree of supply-side substitutability, and many suppliers are able to offer a wide range of inorganics. Nonetheless, supply-side substitutability may also be limited in some cases by the presence of IP rights or the needs for specific knowledge to produce certain types of inorganics, most notably high purity organics and Karl Fischer titration solutions. In case M.7435 the Commission left the product market definition open for inorganics and all possible sub-segments thereof.

(50) The Notifying Party submits no views on the appropriate product market definition for the market for inorganics or any part thereof.

Results of the market investigation: demand-side substitutability

(51) The results of the market investigation in the present case also confirmed that there is very little demand-side substitutability between different types of inorganic, (41) as had been found in the Commission's previous case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich. The market investigation considered in particular the distinctions between: i) inorganics for classical analysis and inorganics for instrumental analysis; ii) within inorganics for classical analysis: the difference between specific types of inorganics (acids, bases, salts, buffers and metals); and iii) within inorganics for instrumental analysis: the difference between inorganics for use in each specific technique (in particular volumetric titration solutions, Karl Fischer products, inorganics for calibration and qualification of analytical instruments, inorganics for sample preparation, inorganics for X-ray fluorescence analysis and auxiliary products).

Inorganics for classical analysis v inorganics for instrumental analysis

(52) The findings of the market investigation in relation to this distinction were very similar to those discussed above for the distinction between solvents for classical analysis and solvents for instrumental analysis. Customers generally confirmed that inorganics for classical analysis and inorganics for instrumental analysis are considered to have different uses, as a result of their different levels of purity, and would not be bought interchangeably. (42) One stated, for example: "we would not expect to see an overlap in their usage, inorganics for instrumental analysis tend to be of a different grade to any purchased for classical analysis". (43) Whilst a number of customers did acknowledge that inorganics for instrumental analysis could theoretically be used for classical analysis, it would be too expensive to do this in practice. One respondent explained: "it is unlikely that an end user would utilise a higher grade more expensive chemical where a lower grade is fit for purpose and likewise would not use a lower grade where clearly for technical reasons a higher grade is required". (44)

(53) Only a very small proportion of customers would consider switching from inorganics for instrumental analysis to inorganics for classical analysis, and this is usually only for a relative small proportion of their total purchases of inorganics for instrumental analysis. (45) The reasons for customers reluctance to do this are very similar to those discussed above for solvents, namely that using a product with lower purity levels could jeopardise the results of the procedure. One respondent referred, for example, to the "risk of inferior results and interferences". (46) A small number of respondents also mentioned that there may be theoretical overlaps in usage, but that they would not typically investigate these. One mentioned, for example, "We purchase inorganics against a specification for the work we need to conduct. In theory inorganics could be used for multiple types of work and as a result there might be an overlap […] but specification is the important factor and not cost". (47) It would seem, therefore, that there very little overlap in usage in practice.

Inorganics for classical analysis: acids, bases, salts, buffers and metals

(54) The results of the market investigation also confirmed that there is very little demand-side substitutability within the category of inorganics for classical analysis. Respondents explained that each of the main types of inorganics for classical analysis (acids, bases, salts, buffers and metals) has a unique composition and function, and can thus not be substituted for with another inorganic. (48) One customer explained, for example: "Every substance is unique, especially in analytical matters. Bases cannot be replaced by acids. Also, sulphuric acid cannot be replaced by nitric acid and so on. Every substance has unique properties, they rarely can be swapped." (49)

(55) As explained above, customers almost without exception follow the specifications of the product, and would not set about testing whether it could be used for a different purpose. One stated, for example: "we basically follow the ISO/AOAC/AFNOR/... classifications. They clearly state which products can be used. We are not testing if we can substitute a type of product with another." (50)

(56) A very small proportion of respondents did see there being some scope for substitution between different types of inorganics for classical analysis, (51) but this was often restricted to particular procedures (such as, for example, that "a buffer can be made from acid/salt or base/salt" (52)) and was not generally stated to be the case. Furthermore, some respondents that mentioned a theoretical overlap in usage also acknowledged that this occurs only very rarely in practice. (53)

Inorganics for instrumental analysis: volumetric titration solutions, Karl Fischer products, inorganics for calibration and qualification of analytical instruments, inorganics for sample preparation, inorganics for X-ray fluorescence analysis, and auxiliary products

(57) Similarly to inorganics for classical analysis, customers also see there being little scope for substitution between the different inorganics for instrumental analysis. The vast majority of respondents confirmed that inorganics designed for a specific type of instrumental analysis are used exclusively for this designated purpose. (54) One respondent explained that they "all have a specific use within the organisation, no double use possible". (55)

(58) As is the case for inorganics for classical analysis, a small number of respondents did identify potential limited overlaps (such as using titration grade inorganics as sample preparation reagents). (56) Nonetheless, it is clear that even these limited theoretical overlaps are almost never exploited in practice. One respondent stated for example, that overlaps in usage are "theoretically present but not in practice, too time consuming". (57) Another respondent explained that the way in which the chemicals are sold would also make it even less likely that customers would use chemicals for any purpose other than that stated in the specification. "Companies […] sell a range of reagents as a calibration kit for example. Some of the kit contents could well be chemicals that would have other uses but an end user is not likely to split a kit for another use." (58)

Results of the market investigation: supply-side substitutability

(59) Responses from competitors indicated that most manufacturers are able to offer a wide range of inorganics. Competitors generally produce both inorganics for classical analysis and inorganics for instrumental analysis. Within inorganics for classical analysis, almost all manufacturers offer a full range including all (or most) of the different types of product (acids, bases, salts, buffers and metals). Those who do not offer a particular category could easily start producing it should they choose to. Within inorganics for instrumental analysis, meanwhile, there is slightly more differentiation between manufacturers. The major global players tend to offer the full range (volumetric titration solutions, Karl Fischer products, inorganics for calibration and qualification of analytical instruments, inorganics for sample preparation, inorganics for X-ray fluorescence analysis and auxiliary products). A number of smaller manufacturers, however, do not currently produce and would not be able to start producing some of these types of inorganics, in particular inorganics for x-ray fluorescence analysis, auxiliary products (such as absorbents and drying agents), some Karl Fischer products and (to a lesser extent) inorganics for sample preparation. This is due to the specific technology and expertise required to produce these products. (59)

(60) Overall, therefore, it can be concluded that there is generally a high degree of supply-side substitutability between most inorganics, but that the expertise required to produce certain types of inorganics for instrumental analysis limits this. The set of manufacturers able to offer these products is therefore more restricted and it would be difficult for other competitors to enter these areas.

High purity acids

(61) As mentioned in reference to acetonitrile (above), the Commission has not previously assessed potential product markets for individual solvents and inorganics, but has been led to do so in this case on the basis of information provided by market participants. A small number of market participants indicated that VWR's presence in the upstream market for the production of high purity acids on an OEM basis (i.e. the form in which this type of acid is then bought by Avantor and other suppliers of laboratory chemicals) could create potential for input foreclosure. VWR (through Seastar) purifies, packs in catalogue size and labels high purity acids for downstream competitors reselling the product under their own brands. As Avantor is active in such dowstream market and a customer of Seastar, the merged entity could hypothetically stop selling on an OEM basis to other downstream competitors.

(62) As VWR is itself present on the downstream market for retail sales, the Transaction also creates a horizontal overlap. In order to assess both the vertical and horizontal relationships between the Parties' activities in this area, the Commission has therefore considered the existence of a possible market for high purity acids. (60)

(63) High purity acids are generally considered to be acids of a level of purity where the contaminants are measured in parts per billion (known as 'PPB acids') or parts per trillion (known as 'PPT acids'). Possible markets could be considered for all high purity acids or for PPT acids only, as the production of PPT acids requires additional steps and authorisation compared to the production of PPB acids. (61)

(64) The Commission noted in case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich that high purity acids were one of the categories of inorganics for which supply-side substitutability may be limited due to the need for particular expertise and IP rights related to their production.

(65) The main differences in the production of PPB and PPT acids compared to other acids for laboratory use are: i) the distillation equipment and piping used for the production of PPB and PPT acids must be made from high purity plastic or quartz; ii) the equipment used for distilling and packaging PPB and PPT acids must be enclosed in a clean-room environment to prevent potential environmental contamination; and iii) PPB and PPT acids are usually packaged in high purity and acid-resistant plastic bottles to prevent contamination and potential leaching from packaging material that could introduce contaminants into the product.

(66) In addition, the production of PPT acids has some additional requirements relative to the production of PPB acids. A second distillation may be required for some PPT acids and producers may have to meet higher requirements in their clean rooms in relation to air exchanges for the production of PPT acids in comparison to PPB production.

(67) The Notifying Party submits that the process of upgrading an existing lower purity acids manufacturing line to manufacture PPB and PPT acids would take approximately […] and would require investment of approximately EUR […] to EUR […], (for a manufacturer that already has the necessary expertise).

(68) The Notifying Party submits that it is not appropriate to define a separate market for high purity acids, and that they should instead be considered as part of the product market for acids that belongs to the overall market for inorganics. It argues that acid producers can and do adapt their manufacturing processes to make acids of differing purities, and that there are no barriers (such as technology or intellectual property) preventing producers of other types of acid from starting to manufacture high purity acids. The additional investment required to be able to produce PPB and even PPT grades is described as 'relatively modest'. The Notifying Party explains that suppliers may choose to purchase high purity acids from other manufacturers on an OEM basis (i.e. under contract manufacturing, to sell under their own brand name) rather than producing these acids themselves simply because this is the most economical option, but not because they would be incapable of producing high purity acids.

(69) Contrary to the statements made by the Notifying Party, the results of the market investigation confirmed that specific equipment and expertise is required to produce high purity acids that would not be needed for producing other acids (or other inorganics more generally). Competitors active in the production of high purity acids mentioned in particular, that the equipment used when manufacturing PPT and PPB acids needs to be made of specific types of material. In general, the higher purity the acid, the more tightly controlled the production process has to be, and additional technology and expertise is therefore required for producing PPT acids relative to PPB, for example, sophisticated analysis techniques to measure the impurities in PPT acids. (62)

(70) The replies received from competitors active in production also suggest that the markets for high purity acids for industrial use (mainly in the semiconductor industry) and for laboratory use are quite separate. A number of other manufacturers only produce high purity acids for industrial customers, mainly because they do not have the production lines for packaging the acids in catalogue sizes, or the general set-up for selling to other types of customer. (63) There may also be some small differences in the specifications for high purity acids for laboratory and industrial use respectively but the main difference is the pack sizes; one respondent explained that "there is no difference in high purity acids for industrial use compared to high purity acids for classical laboratory analysis". (64) Additional responses from suppliers to end customers (i.e. competitors to VWR and Avantor in the laboratory chemicals market) also confirmed this. (65)

(71) For a company that currently sells to industrial customers only, it would therefore require some investments to start selling to laboratory customers (either directly or to laboratory suppliers), and would entail a change in business strategy, given that the market for high purity acids for industrial use is much larger than that for laboratory use because customers request significantly larger amounts. (66) One competitor that currently produces high purity acids for industrial customers only explained that, starting to produce for laboratory use would involve constructing dedicated production facilities including a cleanroom for down-packing, and that it would be at least a year before it were able to commercialise high purity acids for laboratory use. (67)

(72) Given the above, it would appear that there is limited supply-side substitutability between high purity acids and other types of acid (or of inorganics more generally). Producers of other types of inorganic could not easily start producing high purity acids, and a significant investment would be required in new production lines, in addition to which not all suppliers of laboratory chemicals would have the necessary expertise. Furthermore, there are some differences between the processes for producing PPT and PPB acids, meaning that a competitor active in the production of PPB acids could not necessarily start producing PPT acids although it is likely to be easy for a producer of PPT acids to also produce PPB quality products. This is because required purity levels required for PPT acids are 1 000 times higher than for PPB acids. Distillation or purification has to be done using highly specialised equipment and piping (distillation columns, tubing, filling machines etc.) that are made of special materials like Teflon or quartz that do not contaminate the acid. Stainless steel equipment for example is not suitable for these types of materials. Filling of small sized containers is typically done manually in clean room environment with particularly high requirements.

(73) Similarly, there is very little if any demand-side substitutability between high purity acids and other acids. High purity acids are chosen for procedures where a certain level of purity is necessary, thus also determining whether a PPT or a PPB acid should be used. Whilst it would theoretically be possible to use acids of higher purity than needed (e.g. PPT when PPB would be adequate, or PPB where a normal acid could be used), this would clearly not be cost efficient and does not occur in practice.

(74) Based on the above, there would seem to be strong indications that it may be appropriate to define a separate market for high purity acids, distinct from other acids. There are also some grounds to suggest that PPT acids may constitute a market of their own. Should a market for high purity acids (or any sub-segment thereof) be considered appropriate, this may be limited to only high purity acids for laboratory use, to reflect the lack of supply-side substitutability between high purity acids for industrial and laboratory use respectively. (68)

(75) For the purposes of this case, the question as to whether high purity acids (or any sub-segment thereof) constitute a separate product market can be left open, as the Transaction does not lead to competition concerns under any plausible market definition.

Conclusion on market definition for inorganics

(76) For the purposes of this case, the exact product market definition for inorganics and any sub-segments thereof can be left open, as the Transaction does not give rise to competition concerns on these markets under any plausible market definition.

4.2.1.3. Package sizes and brands

Bulk Size v catalogue size

(77) In case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, the Commission also considered the importance of the sizes of the units in which laboratory chemicals are sold. It was concluded that it would be relevant to make a distinction between catalogue size chemicals (defined as being up to 10 kg or 10 litres per unit) and larger, ‘bulk size’ purchases. The main reasons for defining separate markets for bulk and catalogue size chemicals were that the types of customer and the pricing of the chemicals can be quite different, with laboratory customers more likely to purchase catalogue sizes and customers in the manufacturing industries tending to buy bulk sizes. Furthermore, it was found that customers purchasing catalogue sizes could not easily switch to bulk sizes, due to a lack of storage facilities and for safety reasons. From a supply-side perspective, the Commission noted that, whilst most suppliers active in catalogue size chemical also supply bulk volumes to some customers, there are also a significant number of suppliers only active in the bulk size market, as selling in catalogue sizes would require an entirely different business model. The Commission concluded that 10kg or 10 litres was the unit size that reflected a natural divide in the market between catalogue size and bulk size.

(78) The Notifying Party agrees with the Commission’s findings in M.7435 and thus with the definition of separate markets for bulk and catalogue sizes of laboratory chemicals.

(79) The results of the market investigation in the present case also suggested that a distinction between bulk and catalogue sizes of laboratory chemicals would be appropriate. (69) The customers contacted were the Parties' main customers for catalogue size chemicals and the majority of respondents stated in their responses that they did not buy bulk chemicals. Considering the different main categories of customer for laboratory chemicals (pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturers, professional laboratories, and research institutions and universities), it can be noted that a slightly higher proportion of pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturers buy in bulk compared to the other two types of customer, but even within this group, the majority only buy catalogue sizes. (70) Bulk size customers are typically industrial customers in different sectors (including electronics and semi-conductors but also a wide range of other industrial manufacturers) that need large quantities of specific chemicals for their production processes. The needs of those bulk size customers are very different from the needs of laboratory customers that require a range of laboratory chemicals for testing and research purposes in small quantities.

(80) Moreover, almost all of those customers who do not currently buy bulk chemicals stated that they would not be able to buy in bulk. The main reasons given for this were safety considerations, related to the possible risks involved in transferring chemicals between containers, and practical considerations, such as a lack of appropriate equipment and/or storage space for larger volumes and insufficient usage (meaning that the chemicals would go out of date). (71) One customer stated, for example, that "transferring [laboratory chemicals] is not desirable because of safety concerns". (72) Another mentioned that the company was "not equipped to do so properly. It would just not be efficient." (73)

(81) Some customers were of the opinion that bulk chemicals were probably cheaper, but most had little knowledge of the potential price difference having never investigated the possibility of buying in bulk. (74) Furthermore, the price difference does not appear to play any role in customers' decision as to whether to buy chemicals in bulk or catalogue sizes, as for those who only need small volumes and do not have the facilities for repacking, buying in bulk is simply not considered to be a realistic option.

(82) A large proportion of customers reported that they typically buy quantities of laboratory chemicals of 2.5kg/l or 5kg/l. Some even buy in smaller quantities of 1kg or less. In terms of defining an upper limit as to what can be considered 'catalogue sizes', most respondents were of the opinion that either 10kg/l or lower would be an appropriate ceiling. (75)

(83) In light of the above, the Commission considers that, as regards relevant markets for laboratory chemicals, a distinction could be made between catalogue sizes and bulk size. However, for the purposes of this case, the question as to whether catalogue size and bulk size laboratory chemicals can be left open as the Transaction does not give rise to competition concerns under any possible market definition. In any event, the Transaction only results in affected markets for certain solvents and inorganics in catalogue size and this will be the focus of the analysis below. (76) The Transaction does not lead to affected markets for any laboratory chemicals in bulk size considered separately, nor when catalogue sizes and bulk size are considered together.

Importance of branding

(84) Branding is generally important in the industry because specific brands are associated with high and stable quality levels. At the same time, more commoditised chemicals are also available from distributors under their own private labels. The Commission found in case M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich that in order to differentiate themselves suppliers develop brands which are recognised by customers and represent quality, certain set of specifications and consistency of the product. (77) It also found that quality of the product in this context refers not only to the chemical composition or the purity of the product but also to the level of confidence in the documentation and quality of the labelling which are particularly important due to the strong safety hazard in these markets. This quality is generally perceived in the market place through brands. (78)

(85) The Notifying Party explains that some customers, such as pharmaceutical companies and other customers that place a high importance on quality, or are risk-averse generally, favour suppliers with branded products, rather than private (or "house") labelled products. On the other hand, more cost-conscious customers like academic institutions are typically more likely to purchase from suppliers with less expensive private label products. The Parties do not believe that branded products and other chemicals belong to separate markets.

(86) The Commission considers that the specification of chemicals is a scientific definition and that customers in the relevant sectors have a good understanding of the chemical composition of specific products, including purity levels. Therefore, customers can substitute branded and other products as long as they comply with the required specifications. Typically, private labelled products are cheaper alternatives to high priced branded products from the original manufacturers sold under distributor's names. From a supply side perspective, there is also no reason to believe that branded and private label products differ to a significant degree. To the contrary, companies like the Parties that produce branded products can and often do produce private label products that are sold on an OEM basis to other market participants that market them as their own private label products. In this regard, OEM manufacturing refers to a situation where a manufacturer produces chemicals and also packs and labels it for final sales using private brand names of third parties. Such OEM manufacturing also happens on behalf of producers that have strong brands themselves. An example of the latter would be Merck that purchases some of its global sales of high- purity acids from Seastar on an OEM basis without any further processing, repackaging, or labelling done by Merck itself.

(87) In light of the above and for the purpose of this decision, the Commission concludes that private label and branded products belong to one and the same product market. However, it has to be considered that differences particularly in price exist that play a role when analysing the closeness of competition between different products.

4.2.2. Geographic market definition

(88) In its most recent case in this area, M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, the Commission noted that the production market for laboratory chemicals had some features of an EEA-wide market but that there were also indications of national markets. From a supply-side perspective, the Commission found that the majority of major manufacturers sell their laboratory chemicals under the same brands across the EEA and sometimes even globally. Alongside these major suppliers, there are, however, also a number of regional and local suppliers of laboratory chemicals, such as PanReac Applichem (Germany), Carl Roth (Germany), Romil (UK), and Rathburn (UK).

(89) From a demand-side perspective, meanwhile, it was noted that many customers organise purchasing of laboratory chemicals at national or regional level, even if some very large customers have global supply contracts. Furthermore, it was found that suppliers often have sales teams operating at national or regional level. This reflects the highly fragmented nature of the customer base, with suppliers needing local sales forces and technical support to meet the needs of large numbers of small customers. It was also noted that customers in different countries often have different preferences in terms of how they purchase laboratory chemicals and that the variation in customers’ habits and in language requirements was also an important factor that suppliers had to take into account.

(90) In addition, the market investigation carried out in case M.7435 gave some indications that there could at times be significant price differences between countries, which could not be attributed to variations in transport costs or distribution margins alone. Furthermore, the Commission noted that there are both EU and national regulations on the packaging, labelling, transport and storage of laboratory chemicals.

(91) The Notifying Party submits that the geographic market for laboratory chemicals may be at least EEA-wide. It highlights that there are a number of players active on an EEA-wide and even global basis, such as the Parties, Merck, Carlo Erba, Honeywell and Thermo Fisher, and that these suppliers sell their products under the same brand names throughout the EEA and ship their products from a limited number of warehouses located in the EEA. The Notifying Party also claims that an increasing number of international customers negotiate supply contracts that cover their entire EEA or even global operations. Lastly, the Notifying Party submits that there are no intellectual property rights or regulatory barriers that would limit trade flows and that transportation costs for laboratory chemicals are low.

(92) The results of the market investigation in the present case contain a number of indications that the markets for different laboratory chemicals are likely to be national, although there are also a number of characteristics which would suggest a wider geographic scope.

(93) Firstly, a large proportion of customers purchasing laboratory chemicals are active in only one country. This is particularly true of professional laboratories and of research institutions and universities, which, by their very nature, often only have one site. Even universities and other research institutions that coordinate their purchases or organise combined tenders typically do so only on national or even smaller scale. The third group of customers, pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturers, does include more organisations with a wide geographic presence, but there are nonetheless a large proportion only present in one EEA Member State. Amongst those customers that are present in more than one country, purchasing can be organised at either national or EEA level (or wider). Where customers conclude contracts at global level (usually in order to benefit from the greater leverage they can exercise through having larger volumes), there is often also some purchasing carried out at local level, on a more ad hoc basis. (79)

(94) The majority of customers reported that transport costs do not have any influence on their purchases. Transport costs are usually included in the prices quoted by distributors, and because smaller customers are typically buying from distributors that have a local presence, transport costs are not a major consideration when choosing suppliers or distributors, at least within the EEA. (80) One customer stated, for example: "transport cost is not a limitation irrespective of whether we buy from a manufacturer or from a distributor". (81) A small minority of respondents do, however, state that transport costs may influence their purchasing decisions. Some customers mentioned that they try to source only from within the EU, with transport costs being one of the reasons why they would not source from further afield. One explained, for example, that "transport costs always influence our purchasing decisions independently of whether we buy directly from the manufacturer or from the distributor". (82)

(95) Customers' opinions varied as to whether there are significant differences in prices between EEA Member States. A fairly large proportion had no insight into this, due to the fact that they are active in only one country. Of those that did express an opinion, some noted that prices vary between countries, even within the same region (e.g. between western European countries). (83)

(96) The responses to the market investigation from manufacturers and distributors of laboratory chemicals also suggested that national markets may be relevant.

(97) Whilst the majority of the major manufacturers of laboratory chemicals are active at least across the EEA (and often globally), there are also a number of smaller local and regional manufacturers present, which often operate from only one production site and serve a much more limited geographic area. (84)

(98) The majority of competitors organise their sales forces at national level, (85) and some also tend to sell a larger proportion of their laboratory chemicals direct in the countries where they are based, whereas they prefer to use distributors for other markets, where they do not have a local presence. (86) One competitor explained, for example, that "the huge number of customers is better covered by local actors and having local players in the country allows a better level of service", (87) thus highlighting the importance of local distribution networks and personnel. A number of the smaller European producers explained that, although they do sell to customers in other EEA countries, they are generally strongest in the countries where they are based, as they have their own sales forces and can offer shorter delivery times. (88)

(99) A significant majority of customers also stated that their prices vary either between individual countries or between regions in Europe. (89) Some competitors (including the largest players) also offer separate catalogues for each country, mainly due to language requirements. (90)

(100) The barriers to trading between countries and regions most often mentioned by competitors included regulatory barriers (at regional or national level) and transport costs. One competitor explained, for example, that local regulations can change very quickly, making it difficult for manufacturers to adapt. Another also emphasised that without a commercial structure already in place in a different country, it would be difficult to extend operations due to the need for staff familiar with national regulations. Transport costs can also play a role for some products, especially if the product is of lower value (and the transport costs therefore proportionally higher) or if certain packaging or other requirements apply which make transport more expensive. One competitor also explained that the lack of brand recognition for their products outside their home market would make it very difficult to compete effectively. (91)

(101) The results of the market investigation did, however, also confirm one of the arguments put forward by the Notifying Party in favour of a wider geographic market. The majority of competitors sell their products under the same brand names at least across the EEA and often globally. (92) Manufacturers that are active across several countries or even globally (like the Parties) tend to concentrate manufacturing for the whole of the EEA in only few production sites, sell their products under the same brand names throughout the EEA and ship their products from a limited number of warehouses located in the EEA.

High purity acids and acetonitrile

(102) Notwithstanding the above, it should also be noted that the geographic market definition may vary depending on the exact point in the supply chain that is being assessed. It is often the case that suppliers of laboratory chemicals buy the chemical in bulk from a manufacturer, and then purify it further (often via distillation) before packaging it into quantities suitable for laboratory use. Suppliers do not, therefore, always manufacture the actual raw material themselves.

(103) In the case of the market for high purity acids, VWR is active via Seastar in Canada which sells on an OEM basis to third parties globally. The geographic market for this upstream level of production may be different from the geographic market for the downstream sale of the finished product.

(104) The Notifying Party submits that the appropriate geographic market for the production of high purity acids is at least EEA wide, as manufacturers ship these products throughout the EEA.

(105) The location of manufacturers of high purity acids (as a raw material) and their customers (i.e. suppliers of high purity acids to end customers) would indeed seem to suggest that the market for the production of high purity acids is at least EEA wide, if not global, while the downstream market is likely to be national. Upstream competitors also confirmed in their responses to the market investigation that they sell high purity acids to customers across the EEA and often more widely, (93) while competitors on the downstream market (i.e. suppliers of laboratory chemicals to end customers) often sell high purity acids within only one or a small group of countries, as is the case for other laboratory chemicals. (94)

(106) The considerations discussed above in relation to high purity acids largely also hold for acetonitrile. Competitors supplying acetonitrile to end-users very often achieve all or the vast majority of their sales in one country, (95) (although the major laboratory chemicals suppliers that are active across the EEA also market acetonitrile in all the areas where they are present) while raw materials manufacturers serve customers at least across a large region, if not globally. (96)

(107) In light of this, the geographic market for the production of high purity acids and acetonitrile is likely to be at least EEA wide in scope, given the trade flows that can be observed and the standard nature of the product, i.e. the lack of differentiation according to regional preferences.

(108) When considering the downstream market for the supply of laboratory chemicals to end customers, the geographic market for high purity acids and acetonitrile is likely to be national, notwithstanding some indications of a wider geographic scope.

Conclusion on the geographic market definition for solvents and inorganics

(109) For the purposes of this case, the exact geographic market definition for laboratory chemicals and any sub-segments thereof can, in any case, be left open, as the Transaction does not give rise to competition concerns on these markets irrespective of whether they are considered to be national or EEA-wide in scope.

4.3. Distribution of laboratory products

(110) The Commission most recently assessed the market for the distribution of laboratory products, including laboratory chemicals in cases M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich and M.6944 Thermo Fisher Scientific/Life Technologies. While laboratory chemicals were defined as chemicals used for research, testing, and quality control, including thousands of chemicals belonging to different chemical groups, (97) a larger set of products was also considered as a market for laboratory products, including laboratory chemicals but also consumables like glassware and plastic products typically used by laboratory customers (such as pipettes and vials, safety-related products such as gloves, masks, etc.). (98)

(111) The market investigation in case M.7435 largely confirmed the Commission’s findings in the earlier case (M. 6944) and the same approach was taken in both those cases.

4.3.1. Product market definition

(112) In its past decisional practice (as referred to above), the Commission's market investigations indicated that distributors normally offer a wide range of products including a large number of laboratory chemicals from different manufacturers, laboratory consumables (i.e. glassware and single-use equipment such as disposable pipettes and gloves), equipment and instruments, as well life science products (99). Furthermore, one of the reasons why customers often prefer to source laboratory products from distributors was found to be the convenience of being able to buy a wide range of products from one source. In light of this, in the past, the Commission concluded that the relevant product market was likely to be the market for distribution of laboratory and life science products. (100) The distribution of clinical diagnostics equipment for use in hospitals and by pathologists was considered to constitute a separate market (101) (and thus excluded from the market for distribution of laboratory and life sciences products) due to the presence of specific regulatory requirements and differences in the way these products are purchased and in the services required by customers.

(113) The Commission has not previously considered any segmentation of the market for the distribution of laboratory and life sciences products on the basis of the channel through which the products are sold, e.g. online sales as opposed to purchases made from sales reps.

(114) The Notifying Party agrees with the Commission’s previous findings and considers the relevant product market to be the distribution of all laboratory and life science products.

(115) The results of the market investigation in the present case broadly confirm the Commission's findings in its previous cases relating to the distribution of laboratory and life science products. Many customers consider the range of products offered to be an important criterion when choosing a distributor (102) and almost all state that it is preferable if not essential for a distributor to offer a comprehensive range of products. (103) One customer explained, for example, that "[offering a wide range of products] is important / preferable as [the distributor] acts like a one stop shop model for the users". (104) One of the main advantages of buying from a distributor (rather than from the manufacturer) is also considered to be the convenience of having fewer suppliers to deal with, (105) which also stems from the range of products offered by the distributor.

(116) The responses from distributors also suggest that the market for distribution is likely to cover at least all laboratory products and likely also life sciences products, rather than to be limited to laboratory chemicals alone. The vast majority of distributors supply laboratory chemicals, equipment and consumables, and sell all these products to the same customers. (106) Most distributors are of the opinion that other distributors also offer a full range (107) and consider this to be an important part of their business model. (108) One distributor stated, for example: "the customers expect a broad range of products as they do not want to have too many different suppliers". (109) Furthermore, most distributors state that there are no laboratory or life sciences products that they could not start distributing. Only a small minority of respondents felt that there were areas where specific expertise would be needed which they did not have. (110)

(117) The responses provided by some distributors did, however, indicate that the requirements for distributing laboratory chemicals can be slightly different to those for distributing other laboratory products. Distributing chemicals is subject to stricter regulations (such as the ADR regulation) and can also be more time sensitive, as compared to distribution of consumables or equipment. (111)

(118) As regards laboratory chemicals specifically, most distributors confirmed that they are able to distribute certified products. Although some distributors mentioned specific requirements they have to adhere to for the distribution of certified products (e.g. temperature control, separate storage areas and safety measures), only a minority stated that they needed any particular accreditation. (112) In addition, the majority of distributors believe that they would be able to distribute any type of laboratory chemical. (113)

(119) There are, however, also a small number of distributors on national level that specialise in particular types of laboratory chemicals, such as solvents for spectroscopy and/or chromatography. These distributors offer a more specialised range of products and typically do not sell other laboratory chemicals or other laboratory products such as equipment and consumables. Their presence on the market overall appears, however, to be rather limited, with the majority of distributors aiming to offer a wider range so as to be able to better meet customers' needs. (114)

(120) Most distributors serve a wide range of different customer groups and a large majority state that there are no specific groups of customer they would not be able to serve. For those that do mention customers they would not be able to serve, this is mainly large customers, such as pharma companies (for which the distributor would not be able to provide the volumes required and/or which typically enter into global supply agreements and therefore do not use local distributors). (115)

(121) Given that Avantor is not active as a distributor of third party products, no overlap arises in relation to the distribution of third party products. However, the present Decision also assesses potential harm to competition which may arise from the vertical integration of Avantor's activities on the upstream laboratory chemicals markets and VWR's activities as a distributor downstream. The Commission's guidelines on non-horizontal merges specify that when intermediate customers (i.e. distributors) are actual or potential competitors of the parties to the merger, the Commission focusses on the effects of the mergers on the consumers to which the merged entity and those competitors are selling. (116) Accordingly, whilst the Commission in this case has carefully analysed potential input foreclosure of access by competing distributors to laboratory chemicals, the assessment focuses on the impact on final customers. For the purpose of this decision, the Commission therefore has considered in its assessment of the downstream market all sales to final customers, including direct sales and sales via distributors (i.e., internal and external distribution). In addition, the Commission has also assessed the potential customer foreclosure of access by competing manufacturers of laboratory chemicals to distributors by considering external distribution separately.

(122) All the foregoing elements, taken together indicate that the relevant downstream distribution market for the purposes of the assessment of the present Transaction covers at least all laboratory chemicals. The market investigation in the present case did not indicate that a narrower segmentation of that potential downstream market (for example, on the basis of specific laboratory chemicals or particular types of laboratory chemicals) would be pertinent. The elements presented above, rather, tend to indicate that the relevant downstream market is potentially broader and also includes also other laboratory products in addition to laboratory chemicals, and may, in line with the Commission's findings in past cases, also comprise life sciences products (in addition to laboratory products). The elements presented above also indicate that it is not necessary to further segment the market according to the type of customer.

Conclusion on the product market definition for the distribution of laboratory products

(123) For the purposes of this case, the exact product market definition at the distribution level can be left open as to whether it encompasses the distribution of all laboratory and life science products, all laboratory products, or only laboratory chemicals. The Transaction does not give rise to competition concerns under any potential alternative market definition, even considering the narrower potential markets for the distribution of laboratory products alone or for the distribution of laboratory chemicals alone. On that basis, in the present Decision, the Commission will carry out its assessment of the vertical link between the upstream laboratory chemical product markets and the narrower of the potential downstream distribution markets, that is, those comprising (i) only laboratory chemicals and (ii) all laboratory products.

4.3.2. Geographic market definition

(124) In case M.6944 Thermo Fisher Scientific/Life Technologies, the Commission concluded that the market for the distribution of laboratory and life sciences products was national in scope and assessed the market on this basis. This finding was based on the market investigation carried out in that case which confirmed that most distributors operate in a single Member State. The results in that case further suggested that most distributors that are active in several countries organise their sales forces at national level and offer different catalogues in different Member States, as customers typically make purchases at national level. In addition, the Commission noted that prices and purchasing habits (e.g. the use of tenders) vary significantly between different EEA countries.

(125) In its more recent case in this area, M.7435 Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, the Commission confirmed these findings, noting that most distributors operate in a single Member State and that even larger distributors tend to carry out commercial negotiations with customers at national level. This is consistent with the need for a local sales force and local technical support in these markets. However, the Commission left the geographic market definition open in this case.

(126) The Notifying Party submits that the precise geographic market definition for the distribution of laboratory chemicals and life sciences products may be at least EEA-wide.

(127) The results of the market investigation in the present case are consistent with the Commission's findings in its earlier cases. Responses from distributors indicated that the majority are active only in one country (or occasionally in a small group of neighbouring countries) and that they operate from a single warehouse or storage facility. Even distributors that are active across a wider geographic area tend to have national sales forces and different catalogues for each country. As explained in the geographic market definition for the market for the production of laboratory chemicals, the majority of customers conclude contracts at national level, and even multinational companies with global purchasing agreements often also purchase at local level.

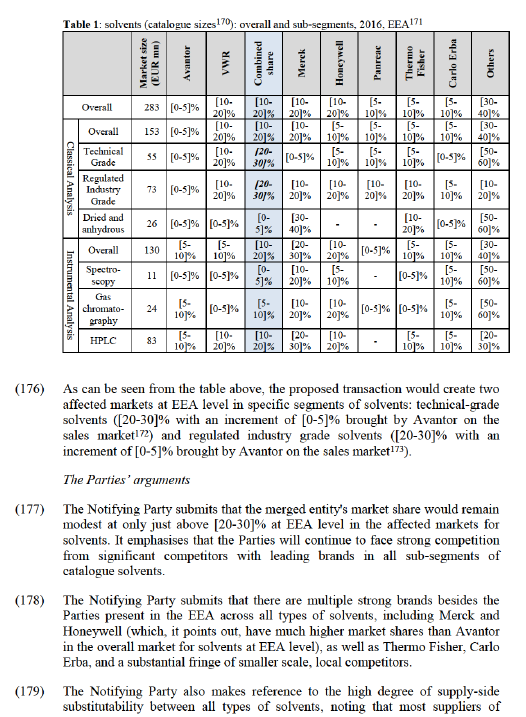

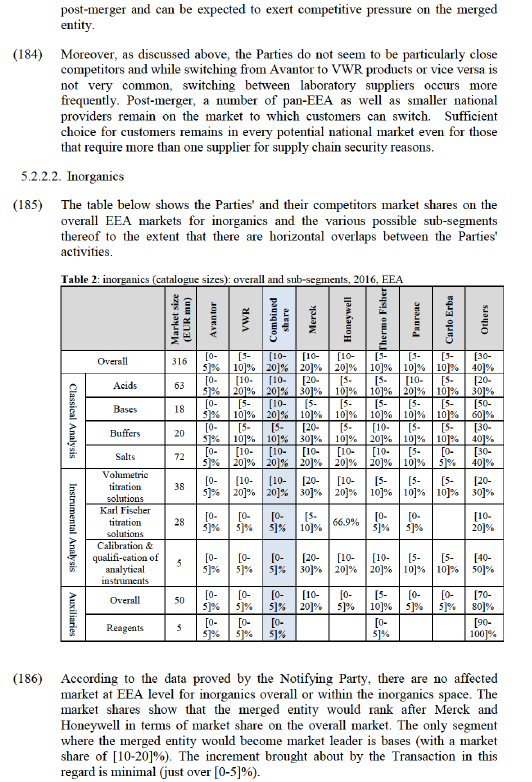

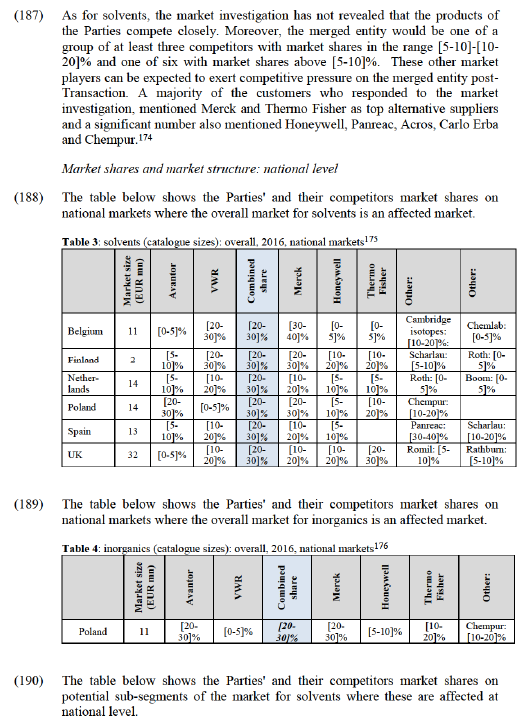

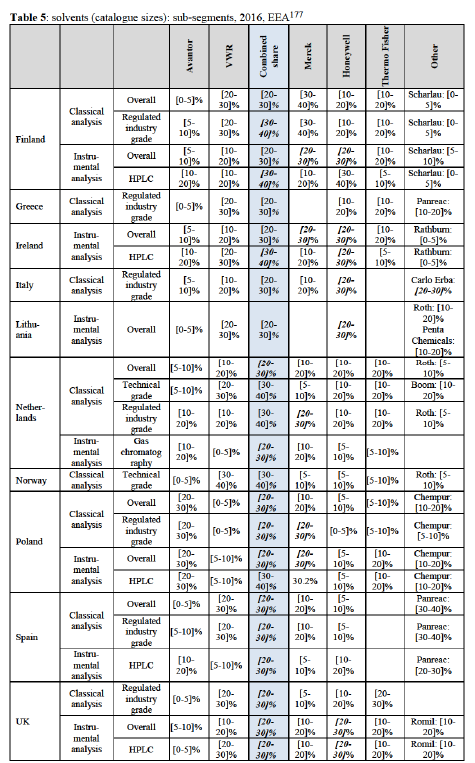

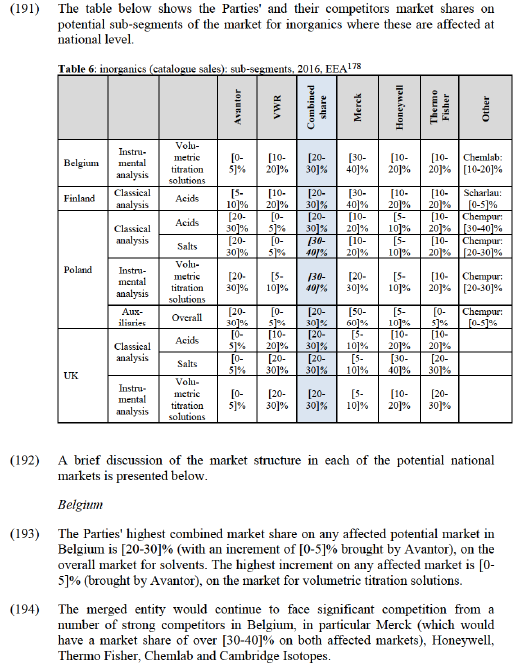

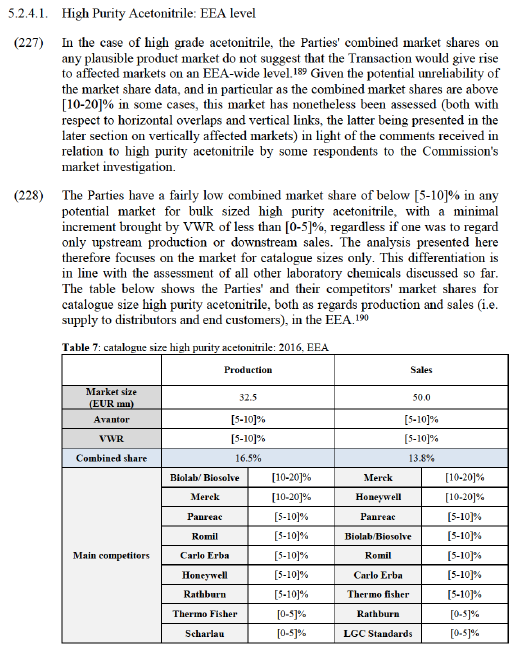

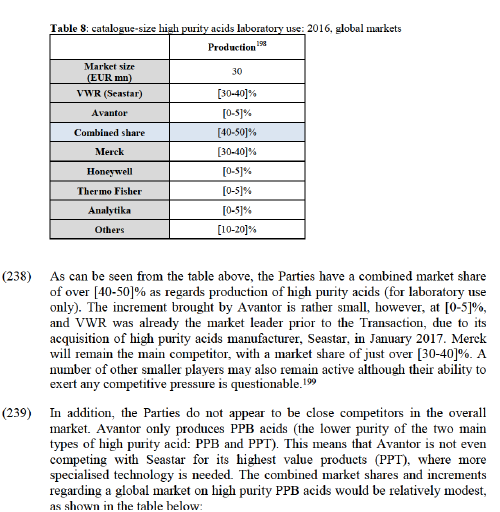

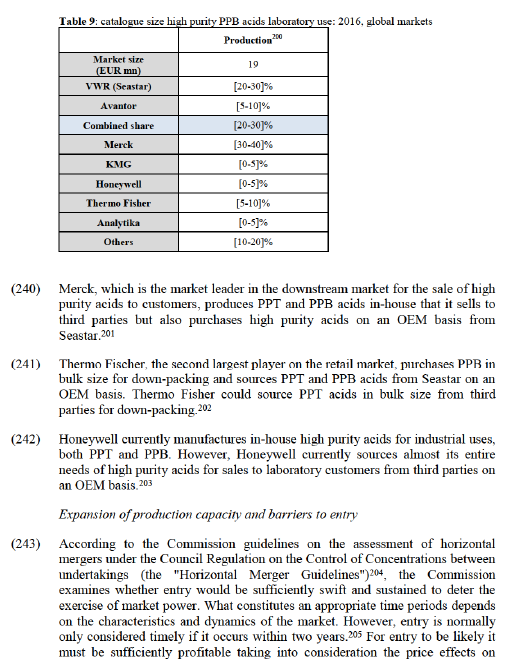

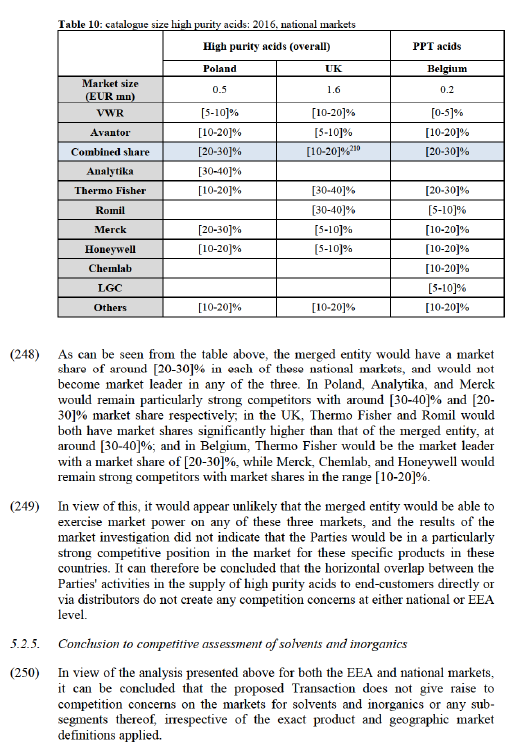

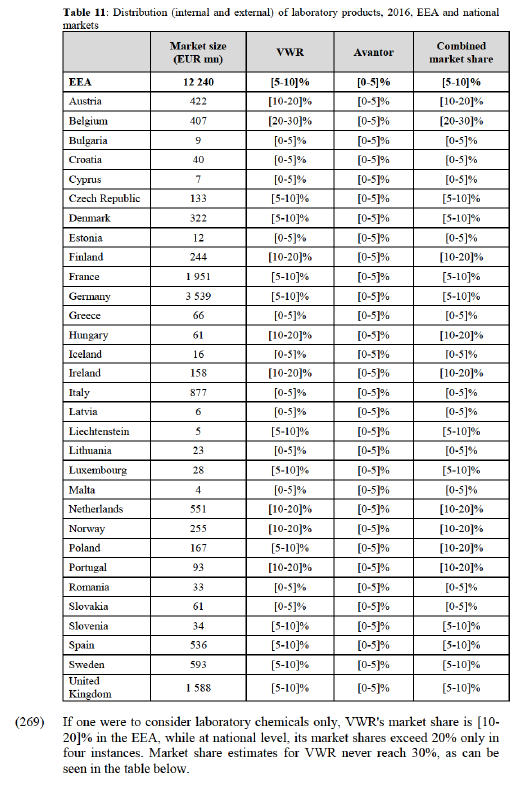

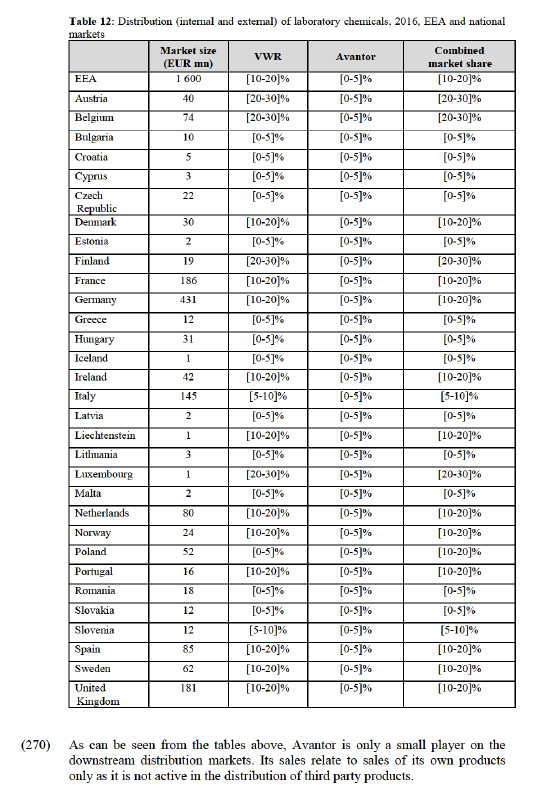

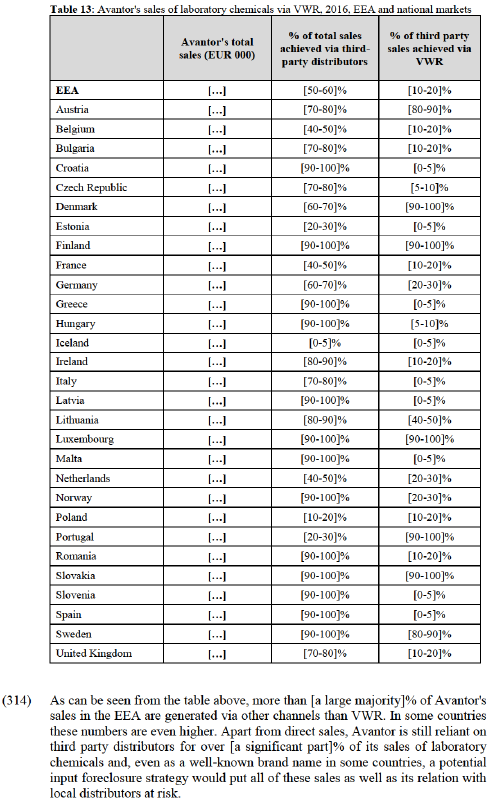

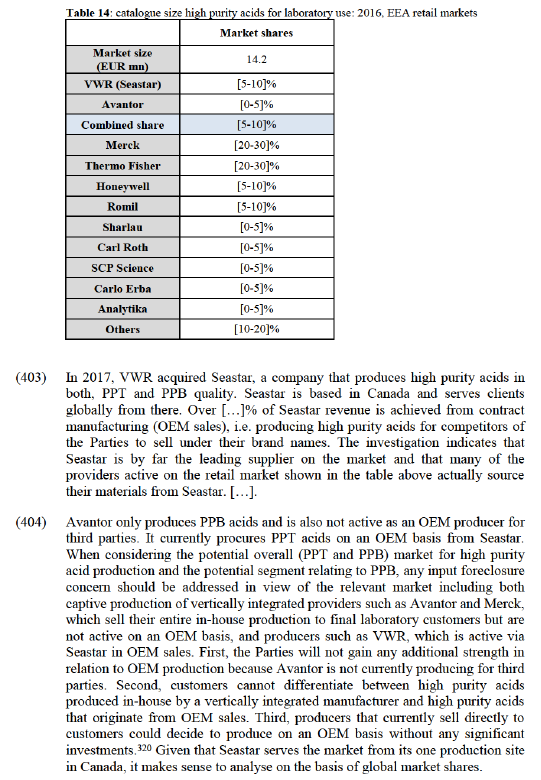

(128) A small number of distributors also reported that transport costs play an important role in competition on the market, at least for some types of product. (Although a larger proportion did not consider transport costs to be an important factor, this is in many cases a reflection of the fact that they are only active in one country.) Transport costs are most likely to be significant when the products are subject to the ADR regulation on the transport of dangerous goods by road, as this creates extra costs. A small number of distributors do therefore see transport costs as a factor limiting their ability to distribute beyond the country in which they have their storage facilities. (117)