Commission, June 27, 2016, No M.7902

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

MARRIOTT INTERNATIONAL / STARWOOD HOTELS & RESORTS WORLDWIDE

Dear Sir/Madam,

Subject:Case M.7902 Marriott/Starwood

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2

(1) On 23 May 2016, the European Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 by which the undertaking Marriott International, Inc. ("Marriott") acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of the undertaking Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, Inc. ("Starwood"). Marriott and Starwood will hereinafter collectively be referred to as "the Parties".3

1 THE PARTIES

(2) Marriott is a diversified hospitality company which acts as a manager and franchisor (and on rare occasions, owner)4 of hotels and timeshare properties in 85 countries and territories. Marriott owns 19 hotel brands internationally, including: The Ritz- Carlton, EDITION, JW Marriott, Autograph Collection Hotels, Renaissance Hotels, Marriott Hotels, Delta Hotels and Resorts, Marriott Executive Apartments, Marriott Vacation Club, Gaylord Hotels, AC Hotels by Marriott, Courtyard, Residence Inn, SpringHill Suites, Fairfield Inn & Suites, TownePlace Suites, Protea Hotels and Moxy Hotels. In addition, it has a license agreement to utilize the Bulgari brand for hotels. As of 30 June 2016, there will be 275 hotels in the EEA operating under Mar- riott brands, with […] rooms.5

(3) Marriott has a loyalty program marketed under two brands, Marriott Rewards and Ritz-Carlton Rewards.

(4) Starwood is also a manager and franchisor (and on rare occasions, owner or lease- holder)6 of hotels and resorts worldwide, with nearly 1 300 properties in some 100 countries.7 Starwood owns the following hotel brands: St. Regis, The Luxury Collec- tion, W, Westin, Le Méridien, Sheraton, Four Points by Sheraton, Aloft, Element, and the recently introduced Tribute Portfolio. As of 30 June 2016, there will be 145 hotels in the EEA operating under Starwood brands, with […] rooms.8 Starwood owns and operates […] of these hotels […], with […] rooms […]. Starwood manag- es […] of these hotels […], with […] rooms […], under management agreements for third-party owners. […] of these hotels […], with […] rooms […], are franchised ho- tels, for which Starwood is neither the owner nor the operator of the hotel.9

(5) Starwood’s loyalty program is Starwood Preferred Guest.

2 THE OPERATION

(6) Pursuant to an agreement and plan of merger dated 15 November 2015 and amended on 20 March 2016, Marriott will acquire sole control over Starwood. The Transac- tion is a result of a series of internal preparatory steps, following which Starwood will be absorbed by a wholly-owned subsidiary of Marriott. As a result, Marriott will be the sole “parent” company of the Starwood group and therefore through the Transaction, Marriott would acquire sole control of Starwood. Marriott's Charter and Bylaws will govern the merged entity post-Transaction. All fourteen board members of the merged entity will be appointed by Marriott and have a fiduciary duty to Mar- riott's shareholders.10

(7) Therefore, the Transaction constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

3 EU DIMENSION

(8) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate worldwide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million11 (Marriott: EUR 22.6 billion, Starwood: EUR 11.8 billion). Each of them has a Union-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Marriott: EUR […], Starwood: EUR […]), but they do not achieve more than two-thirds of their aggregate Union-wide turnover within one and the same Member State.

(9) The concentration therefore has a Union dimension under Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4 MARKET DEFINITION

4.1 Introduction

(10) The Parties are both active in the hotel industry. More concretely, 275 hotels operate under Marriott brands in the EEA, with a total of […] rooms. […] hotels are operat- ed under Starwood brands in the EEA, with a total of […] rooms.

(11) The operation of a hotel may involve up to three different parties:(a) the entity that owns or leases (as the tenant) the hotel;12 (b) the entity that manages the hotel; and (c) the entity that owns the brand under which the hotel operates.

(12) As a result, hotels may be operated under one of the three following main business models:13 (a) Under the first model, hotels are owned and managed by the same company under its own name or brand, which has sole control over them. Hotels oper- ated under this model will be referenced as "owned or leased hotels" in this Decision.(b) Under the second model, hotels are managed by a company − hotel chain or specialised management company ("white label management companies") − on behalf of their owner for a management fee. These hotels are operated un- der the name or brand of the manager, notably if the latter is a hotel chain, or the owner, if the manager is a white label management company. Hotels op- erated under this model will be referenced as "managed hotels" in this Deci- sion.(c) Under the third model, hotel chains franchise one of their brands to hotel owners, who either manage their hotels themselves or use a third manage- ment company. Hotels operated under this model will be referenced as "fran- chised hotels" in this Decision.

(13) Marriott submits that hotels operating under the Marriott and the Starwood brands belong to all three categories. More concretely, as of 30 June 2016, Marriott owns […] and leases […] hotels with a total of […] rooms in the EEA, manages […] ho- tels with a total of […] rooms on behalf of their owners and franchises its brands to another […] hotels with a total of […] rooms.14 Starwood owns […] hotels with […] rooms in the EEA, manages […] on behalf of their owners with a total of […] and franchises […] with […] rooms.15

(14) According to Marriott, companies active in the sector may choose to operate under different models, some owning or leasing a greater proportion of hotels operating under their brands, whereas others may prefer managed or franchised hotels.16 Both Parties have over time adopted an asset-light business model, under which they sepa- rate ownership of the real estate from the hotel management business and the hotel franchising business and increasingly focus their activity on the latter two.17

(15) This variety of business models and ways of operating a hotel has been confirmed by the Parties' competitors and other market participants. Indeed, several hotel chains, such as Hilton, Accor, IHG and others, indicate in the context of the market investi- gation that hotels operating under their brands may be owned/leased, managed or franchised and that, in addition to the operation of owned or leased hotels, they also engage in the provision of hotel management and hotel franchising services.18

(16) In light of the above, in the EEA, the Parties' activities overlap on markets for the provision of hotel accommodation services, markets for the provision of hotel man- agement services and markets for the provision of hotel franchising services.

4.2 Relevant product markets

4.2.1 Hotel accommodation services

(17) The Commission has in its prior decision practice considered a separate market for the provision of hotel accommodation services, leaving however the exact product market definition open.

(18) Marriott submits that there is a spectrum of differentiated offerings in the hotel in- dustry and that the market is heterogeneous from both the demand and the supply side. While the main service provided is accommodation, the sleeping areas vary in terms of size, quality and range of furnishing, location of the room within the hotel etc. Similarly, the range and quality of ancillary services may differ, as some hotels offer 24-hour front desk services, operate restaurants and bars, spa facilities, gift shops, offer meeting spaces, etc. Given the many different services that may or may not be provided in addition to hotel accommodation and the different levels of quali- ty in the provided services, hotels can be differentiated in a multitude of ways. Any hypothetical means of segmentation however, will, according to Marriott, necessari- ly be highly imperfect as the boundaries between any sub-segments of the total mar- ket for hotel accommodation will be blurred. Finally, Marriott believes that the exact market definition can ultimately be left open.19

(19) The majority of respondents to the market investigation having expressed an opinion also indicate that a further segmentation of the market for hotel accommodation ser- vices is not warranted.20

(20) Whether the market for hotel accommodation services should be further segmented will be analysed below. More concretely, it will be assessed whether the overall market should be sub-segmented by ownership type (Section 4.2.1.1) and/or by com- fort/price level (Section 4.2.1.2). Moreover, it will be assessed whether a distinct product market should be considered for accommodation services in short-stay residences (Section 4.2.1.3), or for the provision of specific services, such as confer- ences and events services, hotel loyalty programs, etc. (Section 4.2.1.4).

4.2.1.1 Distinction by ownership type

4.2.1.1.1 Commission's practice

(21) In its prior decision practice, the Commission has considered a sub-segmentation of the overall market for hotel accommodation by ownership type. More concretely, the Commission distinguished between three types of hotels, namely (i) economically and legally independent hotels; (ii) voluntary chains consisting of groups of inde- pendent hotels which carry out their marketing, promotion, purchasing etc. under one and the same hotel brand; and (iii) integrated chains which operate hotels direct- ly through subsidiaries or indirectly by a franchise or management contract.21

(22) The Commission identified the following elements as distinguishing the offer of ho- tel chains from that of independent hotels. From the supply side, hotel chains are or- ganised on the basis of a network concept which meets service requirements that go beyond the purely local framework, are much more uniform from one hotel to anoth- er and more extensive (e.g. extended opening hours, central reservation system, res- taurants, etc.). Moreover, hotel chains operate under a common hotel name and trade mark and have a common marketing strategy for all hotels of the chain, which ena- bles them to raise awareness of their brand much more effectively and at a lower cost than independent hotels would. They also use own centralised reservation systems or have access to international reservation systems, such as Amadeus, Galileo, etc. Last, hotel chains pursue a policy of actively seeking customers, by approaching travel agents, tour operators, corporate customers etc. and offering them differentiat- ed rates, promotions and additional services in order to increase their total sales across the chain. Also from the demand side, large customers such as travel agents, tour operators, corporate customers etc. prioritise hotel chains, with which they can enter into framework contracts setting out negotiated conditions for prices, terms of payment, commissions and discounts.22

(23) The Commission further acknowledged that independent hotels increasingly organ- ise themselves in voluntary chains. In doing so, they become substitutable to hotel chains and increase the offer available to corporate customers, tour operators and travel agencies.23

(24) Ultimately however, the Commission has always left open whether the market for the provision of hotel accommodation services should be further segmented on the basis of ownership type.

4.2.1.1.2 Marriott's views

(25) Marriott submits that independent and chain hotels are substitutable and in competi- tion with each other and that the elements on the basis of which the Commission dif- ferentiated between the two in its prior practice do not apply to the industry today.

(26) More concretely, independent and chain hotels are in the position of offering similar types of services and amenities. Moreover, not all hotel chains offer uniform services among their hotels. The increased operation of hotels under management and fran- chise contracts allows for a more independent operation of hotels belonging to the same chain. The proliferation of information technology, internet travel websites and reservation platforms have changed the industry and placed chain and independent hotels on an equal footing, as they both have immediate access to millions of cus- tomers. Similarly, customers are also empowered to shift their bookings quickly and efficiently away from any hotel operator that fails to meet their expectations on price or quality/facilities. Last, both chain and independent hotels actively compete for corporate customers and cooperate with travel agents and tour operators, as both chain and independent hotels offer promotional packages and special prices.

(27) Marriott further points out that operators of independent hotels have a particularly strong presence in the EEA, corresponding to approximately 70% of all hotels. Also, chain hotels are in competition with independent hotels, as evidenced by the fact that they benchmark themselves against both chain and independent hotels. Excluding independent hotels from the relevant market and from the competitive assessment, would therefore in Marriott's view fail to reflect market reality.24

4.2.1.1.3 Commission's assessment Membership to a chain

(28) Hotel operators consider themselves in competition with both independent and chain hotels. Indeed, the Parties' hotels' competitive sets, i.e. the list of hotels against which Marriott and Starwood hotels benchmark themselves and the performance of which they monitor, consist of both chain and independent hotels. For instance, [ex- amples of independent hotels included in the Parties' competitive sets in Milan] are included in the Parties' competitor sets in Milan, [examples of independent hotels in- cluded in the Parties' competitive sets in Barcelona] in Barcelona etc.25

(29) Furthermore, the Parties' competitors having expressed an opinion in the Commis- sion's market investigation indicate that whether a hotel belongs to a chain or is in- dependent is not among the main drivers of customers' choice between hotels. In- stead, features such as price, comfort level and customers' ratings are more important for the selection of a hotel within a given location.26 Similarly, customers, as well as travel agents and tour operators, also explain that they select hotels taking into ac- count first elements such as price and comfort level, as well as corporate policy, in the case of corporate customers, and users' ratings for end consumers in general. Features such as the affiliation with a chain, the brand and the offering of loyalty programs on the other hand are not among customers' main selection criteria.27

Technological development and industry evolution

(30) The EEA travel industry has evolved significantly in the last decades, most notably through technological developments, such as the broader use of information technol- ogy and online tools and sources, and through the increasing number of hotel chains.

(31) First, the widespread use of internet travel websites has created an environment of instant transparency, enabling every hotel in the marketplace to reach consumers everywhere and communicate their quality, service, and prices to consumers without incurring high costs. In particular through online travel agents ("OTAs"), customers can quickly and easily compare without material costs not only the offerings of all chain and independent hotels, but also their performance through users' reviews. In addition, metasearch engines such as TripAdvisor, Google and Amazon are further streamlining the hotel booking process by creating travel meta-search platforms such as Google Hotel Finder and by leveraging tools such as Google Maps. Furthermore, OTAs and metasearch engines also operate as quasi-international reservation sys- tems, giving independent hotels a reach over a global customer base that is compara- ble to that of chain hotels.28

(32) Second, a number of companies offer technology solutions to hotels that facilitate the distribution of their services, enable direct bookings by customers, help hotel op- erators to establish access to travel agents’ and tour operators’ platforms and metasearch engines. Further services supporting the operation of a hotel, such as business intelligence media, distribution strategy support, revenue management tools and other services are also available on the market and may be used by chain and in- dependent hotels alike. Therefore, independent hotels have nowadays access to tech- nology solutions that give them the possibility to provide easy customer interface and improve their overall performance.29

(33) The majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation submit that chain and independent hotels are rather interchangeable regarding their presence on different distribution channels, but not regarding their access to central- ised reservation systems.30 Against the background of the overall development of the sector however, even in the case of independent hotels that do not have access to centralised reservations systems, customers usually can make online reservations ei- ther directly on the hotel's website or through OTAs. Hence, the significance of ac- cess to centralised reservation systems appears to have diminished in comparison to past years.

(34) Third, the overall evolution of the industry has further facilitated the organisation of independent hotels in either voluntary or integrated chains in recent years.

(35) In the case of voluntary chains, independent hotels set up or enter into affiliations that operate under a common brand, enabling them to promote each other's services. Members of voluntary chains share centralised resources and a wide spectrum of tools and services, such as marketing and advertising support, sales and distribution services, access to global distribution and internet reservation systems, revenue man- agement tools, interconnectivity with OTA platforms, training services, quality sys- tems, loyalty programs, etc. Some of these voluntary chains have a large geograph- ical footprint and account for several hundreds of members, as for example Leading Hotels of the World, Worldhotels, Preferred Hotels, etc.31

(36) Membership to an integrated chain has also evolved in recent years, as business models based on hotel franchising are more broadly used, whereas in the past chain hotels were typically owned and operated by the chain owner. Conversely, today, the number of hotel chains operating in the EEA under an "asset light" model, whereby they focus on the provision of management and franchising services to hotel owners rather than the ownership of their hotels has significantly increased.32 The more widespread use of a hotel operation model based on franchising has thus provided owners and operators of independent hotels with the option to join a hotel chain, while retaining a significant degree of independence. This way, they have the possi- bility to profit from the hotel chain's brand awareness, systems and tools and know- how, while maintaining control over the management of their hotel. The degree of independence of franchised hotels will be further analysed in Section 5.2.1.2 below.

Price rates, services and amenities

(37) Overall, with regard to the price rates and the services and amenities offered, no par- ticular differences are identified between chain and independent hotels. The majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation submit that chain and independent hotels are interchangeable in terms of price.33

(38) Among hotels of similar comfort/price level, offerings such as 24h front desk cover- age, gym and pool facilities, restaurants and bars are provided by both chain and independent hotels.34 The majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation also consider that the range of services and amenities offered by chain hotels is interchangeable with that offered by independent hotels.35

(39) As to the uniformity of the services offered from one hotel to another, the majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation submit that chain hotels offer more uniform products and services from one hotel to another than independent hotels do. Several other respondents, however, indicate that the level of uniformity depends on the specific chains and brands and that, in particular in the case of voluntary chains or chains of franchised hotels, the services offered may vary significantly between hotels belonging to the same chain.36 Indeed, in a number of hotel chains, a significant degree of differentiation in the appearance, style and ser- vice offerings of member hotels is maintained. In the case of high end integrated chains, such as Marriott's Autograph Collection hotels, this may be a strategic choice to appeal more to customers that value individuality.37 In voluntary chains, it is a re- sult of the business model that provides for cooperation in some aspects of member hotels' activity, but not for the standardisation of their offerings. In addition, offer- ings' uniformity has overtime become significantly less relevant as the increased use of OTAs and metasearch engines enables customers not only to acquire immediate information as to the various hotels' service offerings, but in most cases to also see pictures and read users' reviews about the quality and availability of the various ser- vices.

(40) A service feature, typical of chain hotels that are organised in a network, is the set-up of loyalty programs, rewarding customers' multiple stays in hotels of the chain. In recent years, certain loyalty programs are also available to customers of independent hotels. This is primarily facilitated through the participation of independent hotels into loyalty programs offered by aggregators, such as OTAs, metasearch engines, etc.38 Customers of independent hotels that have opted to participate in such OTA loyalty programs, receive rewards related to car rental companies, hospitality pro- viders, etc. if they use the respective OTA for their bookings.39 The majority of re- spondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation however submit that, with regard to loyalty programs, the offer of chain hotels is not substitutable for that of independent hotels.40

Access to the customer base

(41) Independent and chain hotels alike have access to the same customer base. The tech- nological developments and overall evolution of the sector not only helped inde- pendent hotels to raise awareness of their brands among a larger part of the customer base through more distribution channels and OTAs. These developments and evolu- tion further enabled them to compete for corporate customers, tour operators and travel agents, which in the past appeared to prioritise chain hotels for their book- ings.41 Indeed, even though the majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation indicate that chain hotels have more recognition and can more easily reach or be reached by customers than independent hotels,42 they also submit that customers, including corporate customers, purchase hotel accommoda- tion services from both chain and independent hotels.43

(42) First, corporate customers explain that location is one of the main criteria for select- ing a hotel accommodation, as they are interested in ensuring the proximity of their staff to the working premises. The requests for proposals they solicit are therefore addressed to hotel operators in the particular area of their interest, irrespective of whether these belong to a chain or not. Ultimately, corporate customers select a number of hotels, with which they enter into a contractual relationship, on the basis of the proposals submitted by the hotel operators.44 Even though the majority of cor- porate customers having expressed an opinion in the market investigation indicate that chain hotels have an easier access to corporate customers than independent ho- tels, notably due to their dedicated sales departments and ability to centralise purchases for a greater number of locations, they unanimously submit that they purchase hotel accommodation services from chain and independent hotels.45

(43) Second, large OTAs submit that not only they include both independent and chain hotels in their inventory, but that the majority of their inventory corresponds to inde- pendent hotels. Moreover, OTA users do not seem to limit their search of hotel ac- commodation provider to chain hotels, as Booking.com submits that users do not usually filter based on specific brands and Expedia that it does not offer their users any filter function allowing them to distinguish between chain and independent ho- tels.46 The majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market inves- tigation further indicate that OTAs prioritise offerings irrespective of whether the ho- tels belong to chains or are independent.47

(44) The majority of travel agents and tour operators having expressed an opinion in the market investigation also indicate that they propose to their customers hotel accom- modation services from both chain and independent hotels alike and that they give the same visibility and priority in their offerings to chain and independent hotels.48 Moreover, independent hotels may also offer promotional packages to tour operators and travel agents, following the practice of chain hotels. The Parties submit and trav- el agents and tour operators having expressed an opinion in to the Commission's market investigation also indicate that in most chain hotels, the pricing strategy is decided at the level of the hotel and not centrally by the headquarters for the entire chain.49 Therefore, the position of independent hotels is not significantly different from that of chain hotels, when it comes to their ability to make promotions and of- fer rebates to tour operators and travel agents. The majority of travel agents and tour operators having expressed an opinion in the market investigation also indicate that whether a hotel operator offers special prices, discounts, promotional packages, re- lated services such as car rental etc. usually depends on each operator and its con- tractual relationship with the travel intermediary, rather than on its membership to a chain.50

(45) Third, independent hotels may also pursue a policy of actively seeking customers, as they have access to a number of distribution channels and tools that may further in- crease their reputation. Illustratively, some OTAs use priority listings systems, giv- ing greater visibility to hotels that are prepared to pay for this service.51 The fact that independent hotels are in some instances displayed among the first results of search-es in OTA's websites, indicates that they are not only able, but actually making use of this opportunity to increase their customer base.52 Some travel agents and tour op- erators having expressed an opinion in the market investigation state that they offer some form of priority listing for hotel operators willing to pay for such service. Among these travel intermediaries, the majority indicates that whether a hotel opera- tor will choose to make use of such priority listing is unrelated to it being a chain or an independent hotel.53

4.2.1.1.4 Conclusion

(46) In light of the above considerations, the consumers' need to rely on brand as a signal of quality and likely performance has reduced in recent years. Chain and independ- ent hotels offer a similar range of services and amenities at similar prices and have access to broad distribution networks and tools alike enabling them to reach the larg- est part of the customer base, raise awareness of their service offerings and provide user-friendly reservation systems.

(47) Therefore, the Commission concludes that, for the purposes of this Decision, the market for hotel accommodation services should not be further segmented on the ba- sis of ownership type, but rather comprise hotel accommodation services supplied by both chain and independent hotels.

(48) However, because of, inter alia, their more limited access to centralised reservation platforms and loyalty schemes, independent hotels may exert a somewhat lower competitive pressure on chain hotels than chain hotels do on each other. This ele- ment will be taken into account in the competitive assessment (Section 5.2), in par- ticular when assessing if the Parties compete closely with each other on the markets for hotel accommodation services.

4.2.1.2 Distinction by comfort/price level

4.2.1.2.1 Commission's practice

(49) The Commission has in its prior decision practice considered a possible segmenta- tion of the market for hotel accommodation by comfort/price level. This segmenta- tion was notably based on the star-rating of each particular hotel, the star rating be- ing indicative of the standard and facilities the customer may expect when selecting a specific hotel.54

(50) In past cases, the Commission has considered narrower sub-segments for hotels hav- ing the same star rating, for instance 4-star hotels only, 5-star hotels only, etc., as well as broader sub-segments of the total market including hotels with successive star ratings, such as 4- and 5-star hotels combined, 3- and 4-star hotels combined, 2-,3- and 4-star combined, etc.55 Broader categories were taken into account, as even though the star rating reflects the standard and facilities customers may expect from a specific hotel, hotels belonging to successive star categories may in many instances be substitutable from a consumer point of view in terms of price, location and ser- vices.56

(51) Ultimately, however, the Commission has always left open whether and in which way the overall market for hotel accommodation services should be sub-segmented by comfort/price level.

4.2.1.2.2 Marriott's views

(52) Marriott submits that the high degree of differentiation among hotels does not lend to a clear segmentation of the market by comfort or price level. Rather, the provision of hotel accommodation services comprises a spectrum, in which hotels offering di- verse service and quality levels compete with hotels both up and down the spectrum. According to Marriott, there is a high degree of substitutability among portions of the spectrum and this substitutability often spans multiple star categories. Although a consumer may be unlikely to view a 5-star hotel and a 1-star hotel as substitutes for one another, customers can and do consider hotels with different star-ratings as po- tential substitutes, particularly those with adjacent star ratings, for instance 5-star and 4-star hotels; 4-star and 3-star; etc.

(53) Marriott further submits that the segmentation by category used in the industry does not constitute a reliable proxy for market definition purposes, as hotels with similar locations, amenities and price points that clearly compete with each other are classi- fied into different categories.57

4.2.1.2.3 Commission's assessment

(54) Hotel classification systems by comfort/price level exist in most Member States at national and regional level. A great number of hotel associations have contributed to the development of such systems, either on their own initiative or in collaboration with public authorities. As a result of the differences in culture and geographical sit- uations, there are also significant differences between the criteria and methodology followed by the systems used in the various EEA countries.58

(55) The most well-known of these classification systems appear to be the star-rating sys- tem, which is widely used and most visible to consumers, and the classsegmentation, which is widely used by hotel operators in industry reports, market monitoring, etc.

Segmentation by star rating

(56) The star-rating system provides generally for a rating of 1 to 5 stars, granted to ho- tels on the basis of certain criteria linked to the type of services they offer and their quality.59

(57) Against the background of the various national or regional classification systems us- ing diverse criteria, star-ratings may not always provide equivalent comparisons be- tween hotels located in different geographic areas.60 Within a particular country or city, however, where a single star-rating system would be applied, the number of stars awarded to hotels would constitute a relevant proxy for comparing their offer- ings. Indeed, by comparing the services and amenities, as well as the price of hotels with the same star rating in the same location, greater similarities may be identified than when comparing them with hotels with a different star rating. Nevertheless, in- dividual 4-star hotels for example may at times offer a broader service range or be priced higher than 5-star hotels in the same location.61

(58) Several sophisticated customers and competitors having expressed an opinion in the market investigation indicate that in light of these discrepancies and the fact that cus- tomers nowadays rely more on users' ratings for their hotel selection, star rating sys- tems are losing in significance. The majority of competitors having expressed an opinion in the market investigation thus consider that a segmentation of the market by star rating is not required.62

(59) On the other hand, star rating appears to be a significant criterion for at least part of the customer base, as reflected in its widespread use by consumers throughout the world, notably through online travel agents. Among the customers having expressed an opinion in the market investigation that consider a segmentation of the total mar- ket by comfort/price level warranted, the majority submits that this segmentation should be done by star rating.63

(60) The majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation submit that 3-star hotels are not substitutable for 4-star hotels and similarly that 4- star hotels are not substitutable for 5-star hotels. As, however, several respondents also point out that some competitive pressure is exerted by hotels with a subsequent star rating, the existence of broader market segments encompassing both 4- and 5- star hotels is not excluded.64

Segmentation by category

(61) A different type of hotel classification by comfort/price level is widely used among hotel operators and notably by hotel chains, as it is the classification followed by leading providers of competitive benchmarking, information services and research in the hotel industry. Chain and independent hotels are distinguished into up to six dif- ferent categories (classes or scales), on the basis of their actual average room rates.65 In the case of chain hotels, the classification is done on a brand basis on a global chain-wide level, namely all hotels belonging to certain brand are classified in the same category, even if there is some degree of differentiation in the services they provide.66

(62) As the classification into the various categories is done globally for entire brands, it is not a very accurate indicator of the comfort/price level of each specific hotel. This possible inconsistency between the category in which a specific hotel is classified and its actual quality is also reflected in the comparison between the star rating of specific hotels and the category in which these same hotels are classified.67 Moreo- ver, as already indicated, even if hotel chains use this type of classification,68 cus- tomers are not familiar with it and rely instead on hotels' star-rating, which is widely communicated in all distribution channels.69

4.2.1.2.4 Conclusion

(63) In light of the above considerations, the Commission concludes that, for the purposes of this Decision, it can be left open whether the market for hotel accommodation services should be further segmented by comfort/price level on the basis of hotels' star rating. Should narrower distinctions by star rating be considered, it can be left open whether 4-star and 5-star hotels form part of the same market. A distinction by comfort/price level on the basis of comfort classes is considered by the Commission not relevant for the purposes of this Decision.

4.2.1.3 Market for accommodation services in short stay residences

(64) In addition to the provision of hotel accommodation services, both Parties have lim- ited serviced apartments offerings, corresponding to short stay residences.70 More- over, Starwood has some "residential apartment" offerings, i.e. long-term leasehold or owned apartments in some of the hotels it operates. Marriott does not have any "residential apartment" offerings.71

4.2.1.3.1 Commission's practice

(65) The Commission considered in prior decisions whether short stay residences would form part of a broader hospitality market, also including hotel accommodation ser- vices. The Commission identified some differences between the two types of ser- vices, as short stay residences are usually larger than hotel rooms and equipped with a kitchen, the services offered in addition to the accommodation are more limited, the customer base consists mainly of corporate customers and the average stay is longer than in the case of hotels. Ultimately, the Commission left the exact definition of the product market open.72

4.2.1.3.2 Marriott's views

(66) Marriott submits that serviced apartments do not belong to a separate product mar- ket, as they compete not only with conventional hotel rooms, but also with other short stay properties, such as short-term lets and new entrants like Airbnb.73 More- over, even if a separate market for short stay residences or serviced apartments were considered, the Parties' activities in such market are limited,74 as there are […] prop- erties with a total of […] serviced apartments or residential offerings under Marriott brands in the EEA,75 and […] properties with a total of […] serviced apartments op- erated under Starwood brands.76

4.2.1.3.3 Commission's assessment

(67) Given the limited scope of the Parties' activities in offering serviced apartments, the Transaction would not materially impact any plausible separate market for accom- modation services in serviced apartments. Moreover, even if these activities were considered together with hotel accommodation services, as part of a broader market encompassing both activities, the impact of the Transaction would not materially change.

(68) The inclusion of serviced apartments in or their exclusion from the market for hotel accommodation services would therefore not affect any of the conclusions about the effects of the Transaction reached in this Decision. The Parties' serviced apartments' offerings will thus not be further analysed. However, as analysed in Section 5.2.1.3, the Parties' serviced apartments' offerings will, on a conservative basis, be added to their share on markets for hotel accommodation services.77

4.2.1.3.4 Conclusion

(69) Therefore, the Commission concludes that, for the purposes of this Decision, it can be left open whether accommodation services in short stay residences and in hotels form part of the same product market.

4.2.1.4 Markets for the provision of specific services

(70) Within the framework of their overall activity as providers of hotel accommodation, the Parties also offer a number of other services. For example, some Marriott and Starwood hotels offer facilities and services for conferences, meetings and small events, fitness facilities, food and beverages through onsite restaurants and bars, gift shops, loyalty programs, etc.

(71) Such services provided on site in the various Marriott and Starwood hotels are pe- ripheral to the Parties’ primary activity and revenue stream, which is the provision of hotel accommodation services. In that sense, meeting facilities/services, restaurant facilities, spa facilities etc. are provided by the Parties as an alternative to guests us- ing non-hotel providers for the purchase of such services and aim at facilitating the hotel accommodation business.78 Moreover, asked specifically about conference and event services, the majority of the respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation indicate that it is ancillary to hotel operators' primary business and intended to increase the hotels' occupancy rates.79

(72) In light of the above, and considering all evidence available to the Commission, the Commission concludes that the provision of additional services, e.g. for conferences and events,80 fitness and spa, food & beverage, loyalty programs etc. by hotel opera- tors is ancillary to hotel accommodation services and as such will not be further ana- lysed in this Decision.

(73) As set out in Section 5.2, the Parties' activities in relation to the provision of services beyond hotel accommodation will be taken into account in view of assessing if the Parties compete closely with each other on the markets for hotel accommodation services

4.2.1.5 Conclusion

(74) In light of the above, and considering all evidence available to the Commission, the Commission concludes that, for the purposes of this Decision, the relevant product market is the market for hotel accommodation services, comprising hotel accommo- dation services provided by both chain and independent hotels.

(75) It is not necessary, for the purposes of this Decision, to conclude on a potential fur- ther segmentation of that market by comfort/price level on the basis of hotels' star rating in segments consisting of hotels with the same star rating or segments consist- ing of hotels with subsequent star ratings.

4.2.2 Hotel management services

4.2.2.1 Definition of hotel management services

4.2.2.1.1 Commission's practice

(76) The Commission has not, in its prior decision practice, defined a market for the pro- vision of hotel management services.

(77) However, it has considered a separate market for the provision of real estate man- agement services, i.e. the management and operation of real estate on behalf of its owner. Such market could be sub-segmented between the provision of management services to real estate properties for residential and for commercial use. Narrower segments based on the final destination of the properties to be managed for commercial use, such as offices, industrial properties, retail properties were also considered. Ultimately, the Commission left the exact market definition open.81

4.2.2.1.2 Marriott's views

(78) Marriott submits that hotel management services are services provided to hotel own- ers by both hotel chain operators in the context of management agreements conclud- ed with hotel owners as well as by other players such as management companies not affiliated with a particular hotel brand ("white label management companies"). Those services relate to the day-to-day operation of a hotel and include financial ac- counting, generating revenue, managing hotel-specific relations, advertising, promo- tion and marketing services, IT support, human resources management, executing and supervising repairs and maintenance of the hotel.82

4.2.2.1.3 Commission's assessment

(79) In the Commission's market investigation, a majority of respondents agrees that the supply of hotel management services can be defined as operating a hotel for an own- er typically in return for fees and/or a share of revenues (including financial account- ing, generating revenue, managing hotel specific relations, advertising, promotion and marketing, IT support, managing human resources, executing and supervising repairs and maintenance).83

(80) In addition, two respondents underlined the importance of brands in the definition or segmentation of hotel management services, although those two respondents reached relatively opposite conclusions.84

(81) The views expressed during the market investigation on the relevance of branding or franchising services as part of hotel management services confirmed that hotel own- ers deciding to use external providers of hotel management services may opt for ei- ther (i) management services that include brand franchising services by the manage- ment company, as offered by hotel chains, or (ii) management services that do not include hotel branding solutions, as offered by white label management companies.

(82) Furthermore, several hotel chains active on the market for the provision of hotel management services, pointed to a possible link between, on the one hand, the use and scope of management services and their potential providers, and, on the other hand, the category of the hotel to be managed.85

4.2.2.1.4 Conclusion

(83) In light of the above considerations, the Commission concludes that there is a sepa- rate market for the provision of hotel management services, defined as operating a hotel for a third-party hotel owner. Nevertheless, further assessment is needed to de- termine whether hotel owners regard the following hotel management services as in- terchangeable or substitutable: (i) services provided by hotel chains and white label management companies; and (ii) services provided for the management of hotels be- longing to different star ratings or categories / classes.

(84) The Commission will thus consider whether the market for the provision of hotel management services should be segmented based on (i) the types of providers (see Section 4.2.2.2 below) and (ii) the hotel comfort/price level (see Section 4.2.2.3 be- low).

4.2.2.2 Distinction by type of providers (hotel chains versus white label management com- panies)

4.2.2.2.1 Marriott's views

(85) Marriott states that both chain operators and white label management companies of- fer the same types of management services to hotel owners and that from a hotel owner’s perspective, management services provided by a chain operator are substi- tutable with those provided by white label management companies.86

(86) To support that statement, Marriott compares hotel chains and white label manage- ment companies on the basis of specific elements of the management services, that is to say the fees they charge, their international expertise, and the types of hotels they manage.87

4.2.2.2.2 Commission's assessment

(87) The responses to the market investigation questionnaires do not clearly show wheth- er management services provided by a hotel chain, which are bundled with a license of one of the brands it owns, and management services provided by a white label management company, which are stand-alone services that the hotel owner may de- cide to combine (or not) with a license of a brand owned by a hotel chain, are de- mand substitutes.

(88) Overall, most responding hotel owners and hotel chains explained that, at the term of a management agreement, hotel management services provided by a hotel chain can be replaced by hotel management services provided by a white label management company, possibly together with a franchising agreement with a hotel brand owner.88

(89) However, their views were split about the ease or difficulty associated with the re- placement of a managing hotel chain by a white label management company (possi- bly acting together with a hotel franchisor). Indeed, the proportion of respondents indicating that such a replacement can easily take place89 is comparable to the pro- portion of respondents declaring that such a replacement is subject to specific condi- tions, notably: (i) an appropriate level of know-how and capabilities of the white- label management company,90 and (ii) the ability to franchise the hotel under a brand with a comparable positioning.91

(90) In addition, one hotel chain that considered that hotel management services provided by a hotel chain cannot be easily replaced by hotel management services provided by a white label management company underlined the barriers and costs for a hotel owner entailed by the switch from management by a hotel chain to management by a white label management company. The described barriers do not appear to be specif- ic to the replacement of a hotel chain by a white label management company; they could rather also exist in a situation of change of the managing hotel chain.92

(91) By contrast, the additional costs described by that hotel chain would be specific to the substitution of management services provided by a hotel chain by the combina- tion of management services provided by a white label management company and of franchising services by a hotel brand owner.93

(92) Due to the specificities of the fee structure defined under each management agree- ment between a hotel chain and a hotel owner, the Commission is not in a position to relevantly compare, on the one hand, the average total fees due by a hotel owner un- der a management agreement with a hotel chain and, on the other hand, the sum due by a hotel owner of the management fees under a management agreement with a white label management company and of the franchise fees under a franchising agreement with a hotel chain. The Commission nevertheless notes that no hotel own- er mentioned the potential difference in the overall fee levels as a barrier to switch- ing to white label management companies.

4.2.2.2.3 Conclusion

(93) In light of the above considerations, the Commission concludes that, for the purposes of this Decision, it can be left open whether the market for the provision of hotel management services should be further segmented by type of providers (hotel chains versus white label management companies).

(94) In the competitive assessment, the Commission will assess the Parties' positions on the potential segment of hotel management services provided by hotel chains, con- sidering that (i) they do not operate on the other potential segment (services provided by white label management companies), and (ii) the Parties' combined market share would be diluted if hotel chains and white label management companies are consid- ered as operating on the same market for the provision of hotel management ser- vices.

4.2.2.3 Distinction by hotel comfort/price level

4.2.2.3.1 Marriott's views

(95) Marriott believes that the market for the provision of management services, if any, should not be segmented on account of specific hotel categories. It supports its opinion by providing examples of hotel chain operators, such as Accor, and white label management companies, such as Westmont and Interstate, that manage hotels across all comfort/price levels (all 5 star ratings and all STR classes).94

4.2.2.3.2 Commission's assessment

(96) Most respondents to the market investigation consider that the market for the supply of hotel management services should not be further segmented.95

(97) Two hotel chains referred specifically to management services provided in the luxu- ry and upper-upscale segments or in high quality scales. However, those references seem to aim at (i) qualifying the level of substitutability of management services provided by hotel chains, and (ii) insisting on the in-depth expertise required to op- erate high-end hotels, without implying however that such operations would consti- tute a separate market from operating lower-end hotels.96

(98) No hotel owner mentioned that the hotel management services they demand or the level of hotel management fees they owe to their providers would depend on the comfort/price level of the managed hotels.97

4.2.2.3.3 Conclusion

(99) In light of the above considerations, the Commission concludes that, for the purposes of this Decision, the market for the provision of hotel management services should not be further segmented by hotel comfort/price level.

(100) However, in assessing the competitive impact of the Transaction, the Commission will take into account the fact that Marriott and Starwood operate mainly high-end hotels (i.e. mainly 4- and 5-star hotels according to star ratings or luxury, upper up- scale and upscale hotels according to STR classes).

4.2.2.4 Conclusion

(101) In view of the above, and considering all evidence available to the Commission, the Commission considers that the relevant product market is the market for the provi- sion of hotel management services and that the question of its segmentation by type of providers (hotel chains versus white label management companies) can be left open, since no competition concerns arise on any plausible product market defini- tion.

4.2.3 Hotel franchising services

4.2.3.1Commission's practice

(102) The Commission has in its prior decision considered a market for hotel franchising services, leaving the exact market definition open.98

4.2.3.2 Marriott's views

(103) Marriott submits that franchise agreements essentially consist of licenses of industri- al or intellectual property rights relating to trademarks or systems and know-how. In the hotel industry, the hotel is operated under the franchisor's brand name and the franchisor provides services to the third-party owner / manager against payment of fees by the third-party owner to the franchisor.99

4.2.3.3 Commission's assessment

(104) In the Commission's market investigation, the Commission proposed to define hotel franchising as the issuing by a company (the "franchisor") of a contract authorising an unrelated company (the "franchisee") to use a specific name and logo, purchased for an annual fee plus "royalties" usually based on a percentage of sales. Franchisees share such benefits as brand-name identity, corporate image advertising, centralised reservation systems, corporate training programs and volume purchasing. A majority of respondents agrees with that definition.100

(105) In addition, most respondents having expressed an opinion consider that the market for the provision of hotel franchising services should not be further segmented.101

(106) Furthermore, no hotel owner mentioned that the hotel franchising services they de- mand or the level of hotel franchise fees they owe to their providers would depend on the typology or on the comfort/price level (including on the star rating or on the category / class) of the franchised hotels.102

(107) Therefore, the Commission considers that, for the purposes of this Decision, the market for the provision of hotel franchising services should not be further segment- ed by hotel comfort/price level.

4.2.3.4 Conclusion

(108) In view of the above, and considering all evidence available to the Commission, the Commission concludes that the relevant product market is the overall market for the provision of hotel franchising services.

(109) However, in assessing the competitive impact of the Transaction, the Commission will take into account the fact that Marriott and Starwood franchise mainly high-end hotel brands (i.e. mainly 4- and 5-star hotel brands according to star ratings or luxu- ry, upper upscale and upscale hotel brands according to STR classes).

4.3 Relevant geographic markets

4.3.1 Hotel accommodation services

4.3.1.1 Commission's practice

(110) In prior decisions, the Commission has left open the exact geographic scope of the market for hotel accommodation services. It has however noted that the relevant ge- ographic market presented both national and local characteristics.103 The market was considered national because the structure of supply may vary from one market to an- other since the hotel industry is linked to national economic trends, whereas the con- ditions for competition are homogeneous at national level. In addition, the market was considered local, because a second degree of competition exists at a local level, the primary criterion for the choice of a hotel being its location.104 Cities can be con- sidered as local markets for hotels as one of the main features of the hotel sector is its individual city character: customers select hotels in the city where they stay.

4.3.1.2 Marriott's views

(111) According to Marriott, the Commission should assess the Transaction by reference to cities. Indeed, from a demand-side perspective, for the vast majority of customers, hotels located in different cities in the same country are not substitutable with each other. From a supply-side perspective, in setting their prices, hotels will consider their product and price offerings relative to their competitors within the city and with respect to city-wide demand conditions. Marriott adds that administrative boundaries represent the most accurate approach to define a city, as they reflect the scope of each individual city irrespective of its size and layout in the most objective way. Fur- ther, administrative boundaries appear to correspond to the definition of a city found on OTAs, thereby also reflecting the way in which customers look for hotel accom- modation services. Marriott is also of the view that there is no national (or wider) competition as all customer groups tend to make their choices on a local basis.105

4.3.1.3 Commission's assessment

(112) The majority of respondents to the market investigation submit that hotels primarily compete with each other at a local level for hotel accommodation services.106

(113) From the supply side, the way in which hotel operators benchmark themselves and analyse the market, for instance in view of setting prices, gathering market data etc., is also indicative of how they view the geographic scope of the market. Indeed, the competitive sets designed by Marriott and Starwood hotels include a number of competing hotels in the same location and not in different locations within the same country.107 Similarly, when asked about the way prices are set at the various hotels, the majority of respondents indicate that, even if some pricing guidelines are set cen- trally in the case of hotel chains, the final price is set at hotel level.108 Moreover, when setting prices, the majority of respondents explain that they take into account the market prices for hotels of the same comfort/service level in the same location109 and that the prices of hotels in the vicinity are a very important criterion in setting the rates for the supply of hotel accommodation services by a specific hotel.110

(114) From the demand side as well, the majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation indicate that even if corporate contracts have a broad, often worldwide scope and are negotiated at chain level, they are for the pur- pose of the tendering procedure organised on a city-by-city basis, whereby specific terms, such as the participating hotels, the pricing, etc., are dealt with at local level.111 Indeed, customers explain that in view of concluding corporate contracts, they first identify the locations in which they are interested and subsequently invite, di- rectly or through the hotel chain headquarters, hotels in these locations to submit an offer for their accommodation services.112 Moreover, a large number of respondents point out that location is among the key drivers of customers' selection.113

(115) As to the precise delineation of the local market, most respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation indicate that this could be either a city or a city district, in particular in the case of larger cities like London, Paris, etc.114 More- over, industry reports, such as the STR Global's STAR Report, analyse the market primarily on the basis of cities based on their administrative borders, as well as ac- cording to smaller districts within a city ("tracts"), notably as far as larger cities are concerned.115

(116) Such narrower segmentation, however, does not appear to adequately reflect the competitive relationship between hotels located in the same city. Indeed, by sub- segmenting on that basis, hotels falling under different tracts or belonging to differ- ent districts may be closer to each other than hotels within the same tract or dis- trict.116 In the case of London for example, if a narrower market for North Central London were considered, hotels in Camden Town and hotels in Marylebone would be considered as part of the same geographic market, even though within a distance of approximately 3 km, whereas hotels in Marylebone and Mayfair at 1 km distance would belong to separate markets.117 Hotels located in neighbouring city districts appear thus to exert competitive pressure on each other. Therefore, even if such nar- rower segments were to be considered, a chain of substitution would exist between hotels located in neighbouring districts and the total market would again amount to a broader city-wide market for hotel accommodation services.118 As set out in Section 5.2.3.1.2, however, the potential higher competitive pressure exerted between hotels located in close proximity will be taken into account when assessing whether the Parties compete closely with each other on the markets for hotel accommodation services.

(117) The case of city airports may however be somewhat different, as hotels in the airport area are located in close proximity to the airports, which in many instances are in the outskirts of their respective city.119 Moreover, the consideration of the relevant geo- graphic market on the basis of an area's administrative limits would likely not reflect the competitive conditions also in the case of non-city destinations. In the cases of resorts, islands, etc., the administrative limits of a city may not reflect the scope of the market for hotel accommodation services. Elounda, for example, in which the Parties' activities overlap, is a small fishing town in the Lasithi region in Crete. Nu- merous other similar towns exist in the same region and in Crete as a whole and ho- tels situated in those towns are in competition with those in Elounda for guests visit- ing Crete.120

4.3.1.4 Conclusion

(118) In view of the above, and considering all evidence available to the Commission, the geographic market for hotel accommodation services appear to be local.121

(119) The exact delineation of the local market may however be left open, including the possibility of city-wide markets or markets covering a broader e.g. resort area, since no competition concerns arise on any plausible geographic market definition. Simi- larly, whether cities and their respective airport areas shall be considered as part of the same geographic market may also be left open, as no competition concerns would arise, irrespective of the exact delineation of the geographic market.

(120) The Commission concludes that, for the purposes of this Decision, the market for hotel accommodation services should not be further segmented by city districts.

4.3.2 Hotel management services

4.3.2.1 Commission's practice

(121) The Commission has not in its prior decision practice defined a market for the provi- sion of hotel management services.

(122) Concerning the potential market for the provision of real estate management services and all its sub-segments, the Commission has in its prior decision practice left the geographic market definition open, notably whether it is national or local.122

4.3.2.2 Marriott's views

(123) If there were a separate market for the provision of hotel management services, Mar- riott considers that the narrowest possible scope would be EEA-wide because man- agement services are being provided across the EEA (and often globally) by the rel- evant hotel chains, as well as by white label management companies. A potential ge- ographic market which would be narrower than EEA would not reflect market reality as the majority of both chain operators and white label management companies are seeking management opportunities and provide their services at least across the EEA and most of them globally.123

(124) Indeed, Marriott considers that the most fundamental aspects of the competition conditions on a potential market for the provision of hotel management services are broadly similar at a worldwide level. Over the past two decades, Marriott has ob- served an increasingly competitive worldwide marketplace for the provision of man- agement services to hotel owners. Equally, there is a global demand for the provision of management services.

(125) In addition, the types of services offered under a management agreement are broadly similar across the globe. Likewise, the fee structure of Marriott's management agreements is broadly uniform worldwide, with the exception of the USA.124

4.3.2.3 Commission's assessment

(126) To obtain the general views of market participants on the plausible geographic mar- kets for the provision of hotel management services, the Commission asked the Par- ties' competitors as well as hotel owners and white label management companies to identify the geographic area on which hotel management companies primarily com- pete with each other for the supply of hotel management services.

(127) That general question yielded mixed results. The most frequent answer was "world- wide", but the results of the market investigation do not enable to totally exclude "locally", "nationally" or "it depends". In addition, most respondents having ex- pressed an opinion considered that hotel management companies also compete with each other in other geographic areas for the supply of hotel management services.125

(128) With regard to the plausibility of a local market, the Commission is of the view that the minority of hotel owners taking the view that hotel management companies pri- marily compete locally for the supply of hotel management services126 explain their choice by reference to a different market, i.e. the market for hotel accommodation services. They notably refer to the local competition between hotels, which may en- courage multi-property hotel owners to diversify their portfolio of management companies.127

(129) The influence of the functioning of the market for hotel accommodation services is also to be found in the explanations of hotel owners that chose "it depends" as a re- ply to the question on the geographic area on which hotel management companies primarily compete. One hotel owner notably explained that the geographic scope of the competition for the provision of hotel management services depended on the size of the local market (city).128

(130) However, no hotel owner established any correlation between the scope of the com- petition on the market for hotel accommodation services and the scope of the compe- tition on the market for the provision of hotel management services. In particular, no hotel owner mentioned that the market for the provision of hotel management ser- vices was characterised by differences in price or demand at local level (there was, for instance, no preference for a local management company or a local brand).129

(131) In light of the above considerations, the Commission concludes that, for the purposes of this Decision, the market for the provision of hotel management services is wider than local.

(132) Then, in order to determine whether the market for the provision of hotel manage- ment services is national or wider than national, in particular at least EEA-wide, the Commission has assessed the homogeneity of the conditions of competition across the EEA.130

(133) The general question of the market investigation questionnaires on whether the con- ditions of competition on the market for the supply of hotel management services are homogeneous in the EEA triggered divided opinions. Most hotel chains having ex- pressed a view consider that the conditions of competition are homogeneous.131 On the contrary, most hotel owners and white label managers having expressed a view consider that the conditions of competition are significantly different between EEA countries.132

(134) The Commission will therefore rely for its assessment on different factors that, in line with the Commission Notice on the definition of the relevant market, should be taken into account for the definition of the geographic scope of the market for the provision of hotel management services.

4.3.2.3.1 Distribution of market shares between the Parties and their competitors

(135) The Commission notes that the Parties' market shares vary significantly from one EEA country to another and that the competitive landscape shows certain differ- ences, notably with the presence of national players in some countries.133 The differ- ences in the Parties' and their competitors' market shares are confirmed by the mar- ket reconstruction undertaken by the Commission.134

(136) Nevertheless, the Commission considers that those national variations result mainly from the "weight of the past"135 rather than from heterogeneous conditions of com- petition. More particularly, the structure of the market for the provision of hotel management services seems to be inherited, at its early stage of development, from the structure of the market for hotel accommodation services, for the following two reasons.

(137) First, hotel chains need to have demonstrated their capacity to successfully self- manage hotels before being able to compete successfully for the provision of hotel management services to third-party owners. Therefore, strong players on the market for hotel accommodation services in a certain country are likely to capitalise on their strength and grow into strong players on the market for the provision of hotel man- agement services at national level, thus enjoying higher market shares in their do- mestic market before expanding to other markets.136

(138) Second, the market for the provision of hotel management services results, at least partly, from the development of an asset-light business model in the hotel industry and the trend towards the divestiture by hotel chains of the assets they own. Since a hotel chain that engages in the divestiture of the hotels it owns is likely to continue, at least initially, managing its divested hotels, the heterogeneous presence of a hotel chain throughout the EEA, and a strong domestic market share, may simply derive from the heterogeneous geographic distribution of its hotels.

4.3.2.3.2 Pricing and basic demand characteristics

(139) First, Marriott's pricing and contracting practices are broadly similar across the EEA.137 Starwood's pricing and contracting practices are consistent not only across the EEA States, but also across the broader Europe, Africa and Middle East region and worldwide.138

(140) Importantly, most respondents to the market investigation questionnaires having ex- pressed a view consider that the types of services requested by hotel owners under management agreements and the level of management fees do not vary significantly from one EEA country to another.139

(141) In addition, respondents mentioning hotel owners' possible national preferences acknowledge that those preferences would have an effect on (i) the level of expertise required from hotel management services rather than on their place of establishment,140 and (ii) the focus of the management services to be provided rather their na- ture.141 Therefore, any national preferences would not lead to the differentiation of the hotel management services and of the key provisions of the management agree- ments between EEA countries.

(142) The Commission therefore considers that prices and demanded services are homoge- neous throughout the EEA.

4.3.2.3.3 Possible barriers to entry or expansion in national markets

(143) Respondents to the market investigation questionnaires indicate that the following elements may impact the level of homogeneity of the conditions of competition of the market for the supply of hotel management services in the EEA: (i) the absence of a single law governing hotel management agreements;142 (ii) the degree of uptake by hotel owners of an externalised hotel management model.143

(144) However, the Commission does not consider that those elements constitute barriers isolating the different national markets in the EEA. Indeed, the different applicable legal systems may render the provision of hotel management services across the EEA more complex and costly than if a uniform EEA legal system existed.144 They may therefore have an effect on the attractiveness of entry or expansion in certain markets. However, they do not constitute regulatory barriers that could not be over- come by hotel chains, especially those that already self-manage hotels throughout the EEA and, consequently, could manage hotels for third-party owners without fac- ing any further legal or administrative requirement.

(145) As to the degree of uptake by hotel owners of externalised management services, it equates to the degree of maturity of the market for the provision of hotel manage- ment services in different countries, which may explain the variations in the propor- tion of rooms managed by hotel chains (compared to the total number of rooms owned by owners unrelated to hotel chains). This nevertheless does not delineate dif- ferent markets, since the relative size of the market for the provision of management services in a certain country has no impact on the conditions of competition for the award of the corresponding management agreements. As an example, in Germany (one of the countries with low penetration of hotel management services according to a response to the market investigation), the Commission notes that hotel chains headquartered in other EEA countries or in the USA, such as the Parties, IHG, Hil- ton, Groupe du Louvre, Accor, do provide hotel management services and hold mar- ket shares that are comparable and even higher than those headquartered in Germa- ny, such as Steigenberger and TUI.

(146) Besides, initially region-focused chains or white label management companies (e.g. Westmont Hospitality Group, Interstate Management Services or Scandinavian Hos- pitality Management) expanded their presence across the EEA or worldwide.145

(147) In view of the above, and considering all evidence available to the Commission with regard to (i) the pricing of hotel management services, (ii) the characteristics of the demand in management services, and (iii) the profile of companies competing for the management of the most attractive properties throughout the EEA, the Commission considers that the national discrepancies in the conditions of competition between EEA countries are not significant enough to question their overall homogeneity across the EEA.

(148) Moreover, most large hotel chains having responded to the market investigation questionnaires consider that they compete with each other for the provision of hotel management services at worldwide level.146

(149) There are therefore indications that the market for the provision of hotel manage- ment services is likely to be at least EEA-wide and even worldwide. However, for the purpose of this Decision, the question of whether it is EEA-wide or worldwide can be left open because the assessment of the Transaction would not lead to any competition concerns under either market definition.

4.3.2.4 Conclusion

(150) In view of the above, and considering all evidence available to the Commission, the Commission considers that, for the purpose of this Decision, the market for the pro- vision of hotel management services is at least EEA-wide.

(151) The Commission will assess the effects of the Transaction at both EEA- and world- wide levels.

4.3.3 Hotel franchising services

4.3.3.1 Commission's practice

(152) The Commission has in its prior decision considered that the market for hotel fran- chising services presents supra-national characteristics, ultimately however leaving the exact market definition open.147

4.3.3.2 Marriott's views

(153) Marriott submits that any market for the provision of hotel franchising services would be worldwide and provides examples of brands from Marriott, Starwood and competitors that are franchised on a global basis.148

(154) Marriott acknowledges that there are differences in shares by hotel brands from country to country. Nevertheless, it argues that those differences are due to the time needed to expand a hotel brand across the world in an intensely competitive market- place.149

(155) In addition, Marriott considers that the most fundamental aspects of the competition conditions on a potential market for the provision of hotel management services are broadly similar at a worldwide level. There is a global demand for the provision of hotel franchising services. The types of services offered under a franchise agreement and its main terms and conditions, including franchise fees, are broadly similar across the globe.150

4.3.3.3 Commission's assessment

(156) To obtain the general views of market participants on the plausible geographic mar- kets for the provision of hotel franchising services, the Commission asked the Par- ties' competitors as well as hotel owners and white label management companies to identify the geographic area on which hotel franchisors primarily compete with each other for hotel franchising, in terms of (i) brand awareness (i.e. area where the com- petitors' brands are known), and (ii) presence (area where competitors have a hotel already operating under their brands).

(157) The majority of respondents indicate that hotel franchisors compete with other fran- chisors whose brands are known world-wide, followed by those considering that "it depends". The opinions of respondents were divided as to whether hotel franchisors also compete with each other, in terms of brand awareness, in other geographic are- as.151

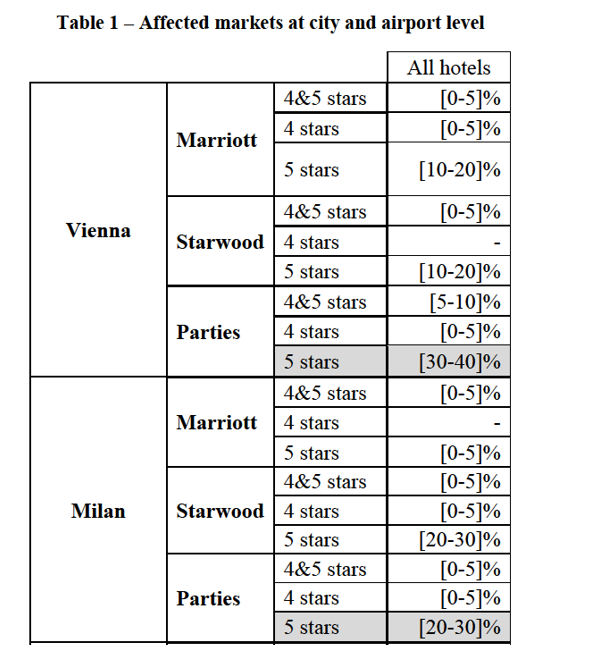

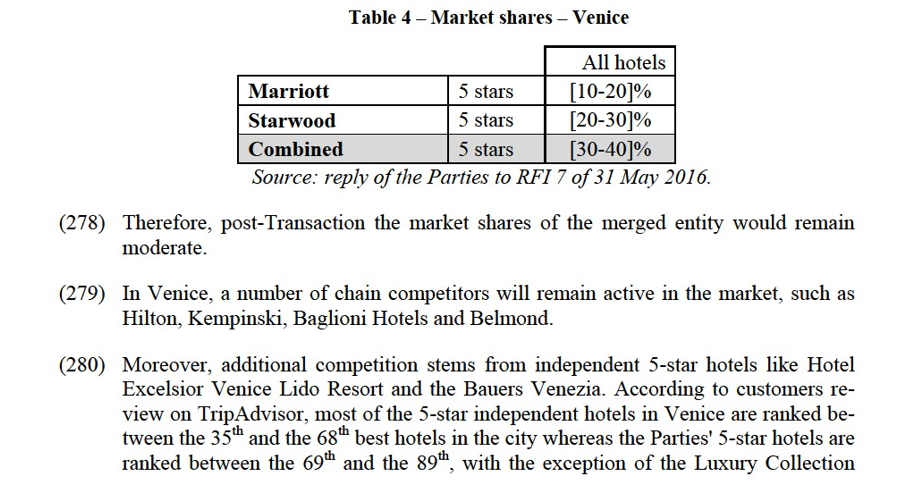

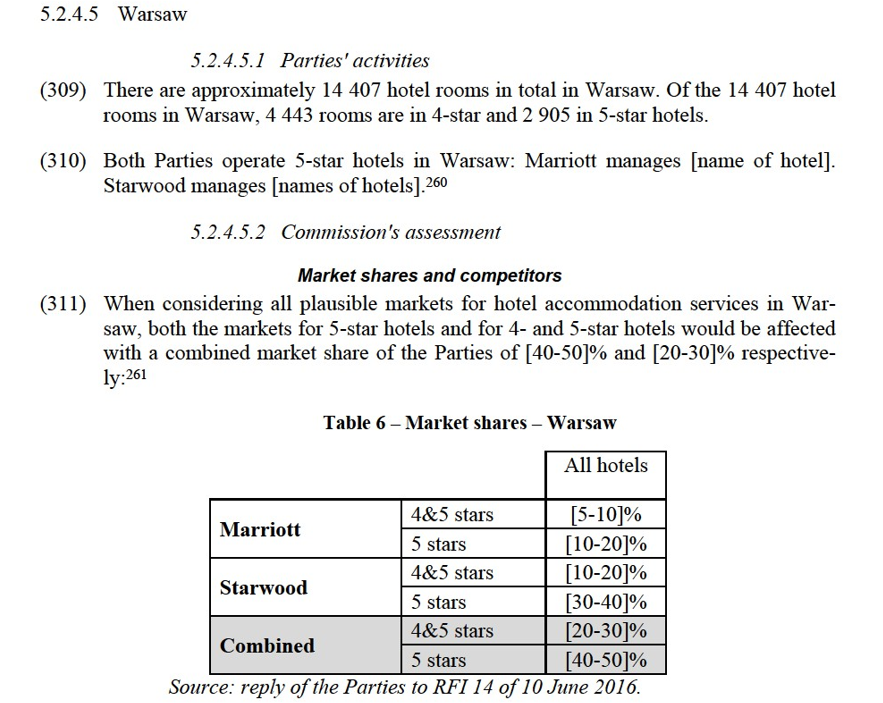

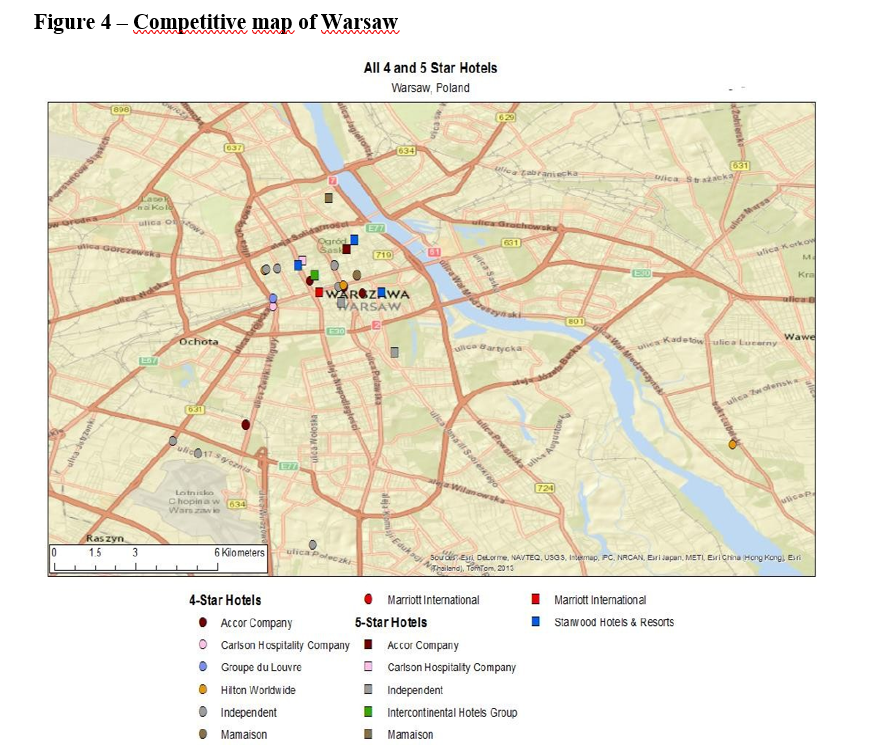

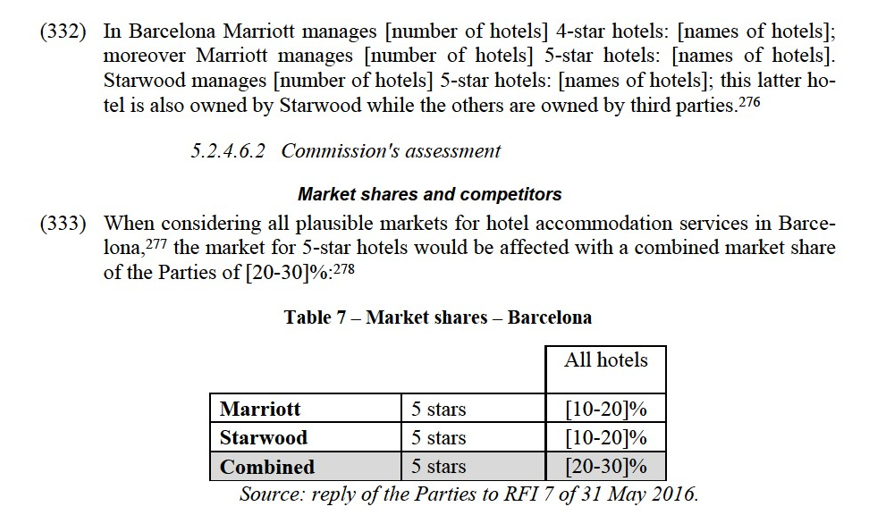

(158) There was no consensus on whether hotel franchisors compete with each other based on their presence on certain geographic area, as the majority of respondents an- swered that "it depends", followed by those – predominantly hotel chains – consider- ing that they compete with other franchisors having a world-wide network of hotels operating under their brands, and those considering that they compete with franchi- sors having a hotel operating under their brands in the specific location in which the hotel to be franchised is located. Finally, the responses are also divided as to whether hotel franchisors also compete with each other for hotel franchising, in other geo- graphic areas in terms of presence.152