Commission, December 15, 2014, No M.7387

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

BP/ STATOIL FUEL AND RETAIL AVIATION

Dear Madam(s) and/or Sir(s),

Subject: Case M.7387 - BP/ Statoil Fuel and Retail Aviation

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) in conjunction with Article 6(2) of Council Regulation No 139/2004 (1)

(1) On 27 October 2014, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (2) by which BP p.l.c ("BP", UK) acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of the whole of the undertaking Statoil Fuel & Retail Aviation AS ("SFRA", Norway) by way of purchase of shares. BP is designated hereinafter as the "Notifying Party" and both BP and SFRA are designated hereinafter as "the Parties".

I. THE PARTIES

(2) BP is active across the value chain of oil and gas from the exploration and production over the refining to the distribution of fuel products. BP's activities include the refining of aviation fuel and the into-plane supply of aviation fuel on a global level.

(3) SFRA is active in the into-plane supply of aviation fuel at 80 airports in the EEA with a focus on Scandinavian airports.

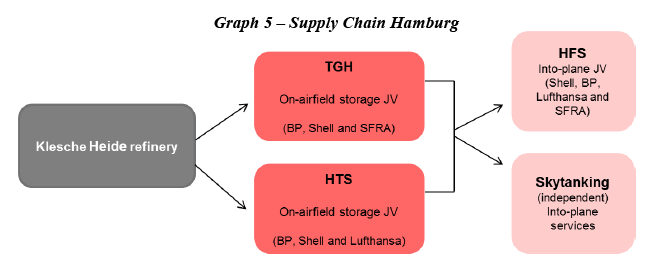

II. THE OPERATION AND THE CONCENTRATION

(4) The transaction consists of SFRA's parent, Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc. ("Alimentation Couche-Tard", Canada), transferring 100% of the shares in SFRA to BP. The operation therefore constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

III. EU DIMENSION

(5) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (3) [BP: EUR 285 471 million; SFRA: EUR […]]. Each of them has an EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million [BP: EUR […]; SFRA: EUR […]] but they do not achieve more than two-thirds of their aggregate EU-wide turnover within one and the same Member State.

(6) The notified operation has therefore an EU dimension within the meaning of Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

IV. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

1. Background

(7) Aviation fuel is a product of the crude oil refining process, with kerosene (the base ingredient of aviation fuel) being extracted as crude oil is distilled.

(8) Refineries typically produce either gasoline (petrol) or middle distillates, such as diesel and kerosene for aviation fuel. Whether a refinery chooses to produce diesel or aviation fuel will largely be driven by the demand and value of the product in the market at a particular time.

(9) As EU refineries produce insufficient middle distillates to meet EU demand, the demand for aviation fuel in the EU is met by refineries within EU Member States and fuel imported from outside the EU. A considerable volume of aviation fuel is therefore transported internationally (by ships) to be used at EU airports which lack immediate access to refineries or where the local refineries cannot match the local demand.

(10) Into-plane suppliers typically purchase fuel ex-refinery (or ex-storage tank or ex- ship at an import terminal) and transport it by pipeline or vessel to an off-airfield storage terminal near the individual airport. From there, the aviation fuel is transported to an on-airfield storage site at the airport and distributed via hydrants or fuel trucks (bowsers) into the air planes. At the airports into-plane suppliers rely on access to the distribution infrastructure (i.e. on-airfield storage and hydrants), which is controlled by joint-ventures in which the into-plane suppliers are shareholders.

(11) The supply chain is illustrated in Graph 1 below

(12) As an alternative to investment in infrastructure, into-plane suppliers may supply aviation fuel without investment in the on-airfield infrastructure or service companies. One example is the throughputter model, where the supplier has an agreement to use the on-airfield storage capacity and into-plane supply services owned and operated by the service company at the relevant airports. There is also the reseller model, where the reseller only acquires title to the aviation fuel at wingtip once it has passed through the infrastructure at the airport, and then, as the fuel is delivered to the aircraft, pursuant to the contract between the reseller and the airline, it re-sells the fuel to the airline.

(13) Purchasers of into-plane services include commercial airlines, the military and owners of smaller aircraft such as private jets or light aircraft (so-called general aviation). Commercial airlines account for over 95 per cent of aviation fuel demand in the EU. Airlines typically purchase their aviation fuel requirements on an into- plane basis at the airports that they fly to or from. Airlines can also operate on what is known as a self-supply basis, where they purchase the fuel further up the supply chain (e.g. ex-storage at the airport, ex-storage tank at an import terminal, ex-ship, or ex-refinery), and then arrange on their own for the fuel to be supplied into their aircraft, either on a throughput basis or by acquiring an interest in the relevant service companies operating at the airport.

(14) The companies' into-plane supply activities overlap at six airports: Copenhagen, Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmö, Hamburg and to a more limited extent in Amsterdam.

2. Product Market Definition

(15) BP is active in ex-refinery sales of aviation fuel on a worldwide basis. The Target is not active in this area. Both BP and the Target are active in the into-plane supply of aviation fuel at some airports in the EU.

(16) The Commission has in the past considered that aviation fuel constitutes a distinct product market, which is separate from other motor fuels. (4)

(17) The Notifying Party supports the above mentioned product market definition.

(18) The large majority of respondents to the market investigation submitted that aviation fuel constitutes a separate product market from other motor fuel (5) given logistical, equipment and product differences. (6) The Commission considers, based on the results of the market investigation, that aviation fuel constitutes a separate product market from other motor fuels.

(19) In addition, from a demand side perspective, it is noted that aviation fuel could be further segmented into two different types of aviation fuel depending on what it is intended to be used for: (i) jet fuel, which is a kerosene-based fuel used in turbo-fan, turbo-jet and turbo prop engine aircrafts, typically used by the larger commercial airlines, and (ii) avgas which is a gasoline-based product, typically used to supply smaller aircrafts with a piston or reciprocating engine.

(20) The Notifying Party claims that no further segmentation should be made between jet fuel and avgas. The Notifying Party further claims that the only airport where the Parties overlap in the sale of avgas is at Malmö airport, since the Parties do not sell avgas at any of the other affected markets. The volumes at Malmö airport are de minimis.

(21) The Commission has previously considered that ex-refinery sales of aviation fuel should not be further segmented into these two potential submarkets. (7) As regards a possible segmentation of aviation fuel between avgas and jet fuel at the airport level, the Commission notes that there are indications that they are not substitutable from a demand side perspective. In any case, the market definition can be left open in this regard as it does not change the competitive assessment in the present case.

(22) Therefore, taking into account the results of the market investigation and for the purpose of the present case, the Commission considers that aviation fuel constitutes a separate product market from other motor fuels. As regards the potential distinction of aviation fuel between avgas and jet fuel, the precise market definition can be left open in this specific case as the proposed transaction raises serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market regardless of the product market definition (8). In Stockholm, Copenhagen and Gothenburg, the Parties only supply jet fuel. In Malmö, where both Parties supply avgas, the Commission analyses the competitive situation for jet fuel and avgas separately.

Ex-refinery sales of aviation fuel

(23) According to previous Commission decisions, ex-refinery sales of aviation fuels constitute a distinct product market. (9) Ex-refinery sales are sales of large quantities by refineries to wholesalers, resellers or airlines with access to the required transport and storage infrastructure. These sales also include sales to into-plane suppliers. (10)

(24) The Notifying Party agrees that ex-refinery sales of aviation fuels constitute a distinct product market.

(25) The large majority of respondents to the market investigation submitted that, in line with the Commission's previous decisions, ex-refinery sales of aviation fuel consist of sales made in large volumes on a spot basis or term basis by refiners to wholesalers, other oil companies, traders, resellers and large industrial customers, including sales to into-plane suppliers. (11)

(26) The majority of respondents to the market investigation also submitted that there is no need to distinguish between avgas and jet fuel within the market for ex-refinery sales. (12) This is in line with previous decision making practice of the Commission. (13)

(27) Taking into account the results of the market investigation and for the purposes of the present case, the Commission considers that ex-refinery sales constitute a separate market which includes avgas and jet fuel.

Into-plane supply of aviation fuel

(28) According to previous Commission decisions, into-plane supply (also known as retail supply) consists of the supply of aviation fuel at individual airports under contracts between into-plane suppliers and airlines, with the fuel supplied pursuant to the arrangements with servicing companies (of which the company may or may not be a member/owner) that operate the airport fuelling infrastructure (storage, hydrant pipelines) and perform actual into-plane fuelling services with dispenser vehicles or fuelling trucks to the aircraft for a fee paid by the airlines. (14)

(29) The Commission has in the past considered that into-plane supply of aviation fuel constitutes a separate product market. (15)

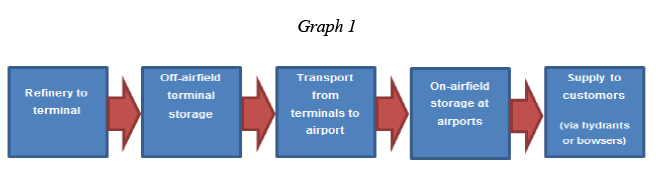

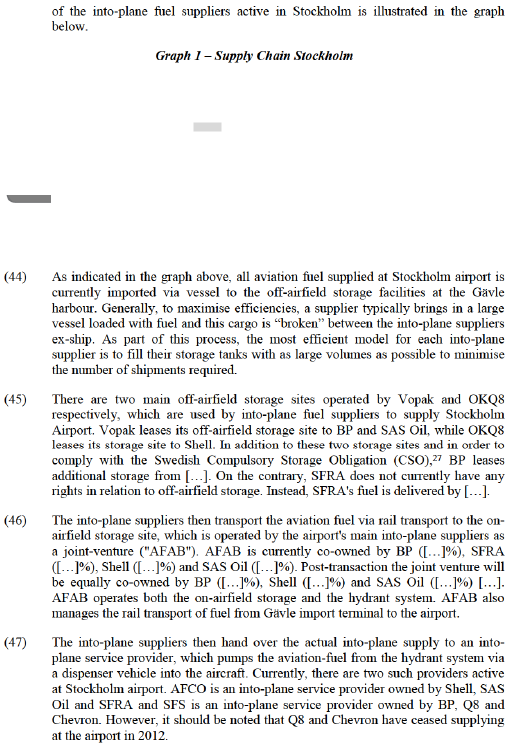

(30) The Notifying Party agrees with this market definition.

(31) The majority of the respondents to the market investigation submitted that, in line with previous Commission's precedents, into-plane supply of aviation fuel constitutes a separate product market. (16)

(32) Taking into account the results of the market investigation and for the purposes of the present case, the Commission considers that into-plane supply of aviation fuel constitutes a separate product market. As regards the potential distinction of aviation fuel between avgas and jet fuel, the precise market definition can be left open, as better explained above.

3. Geographic Market Definition

Ex-refinery sales of aviation fuel

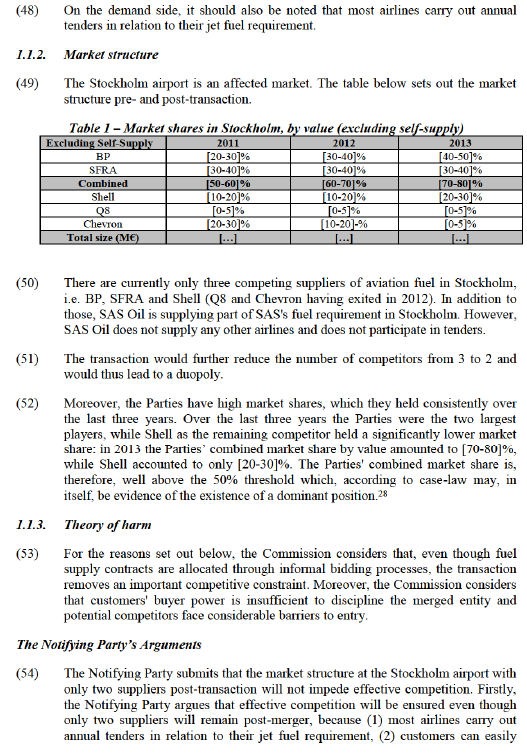

(33) The Commission has in the past considered the geographic scope of the market for ex-refinery sales of aviation fuels to be EU or Western-Europe wide. (17) However, the Commission has also considered a smaller Northern European market consisting of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. (18)

(34) The Notifying Party submits that the market should be at least EU-wide given that: (i) there is significant trade of aviation fuel across the EU and indeed a significant volume of aviation fuel is imported from outside the EU (approximately 20 per cent of aviation fuel consumed in the EU is imported, mainly from the Middle and Far East); (ii) aviation fuel may be transported with relative ease and at low cost over vast distances by ship; and (iii) 80 per cent of aviation fuel supplied at airports in Denmark and Sweden is provided from imported sources.

(35) The Notifying Party further notes that even if a narrower market definition is adopted (e.g. Scandinavian or national markets where SFRA is active downstream), BP does not own or have an interest in any refineries in Scandinavia and only owns or has an interest in five refineries in Germany. All of BP's refineries are inland and none of them supply aviation fuel to Hamburg airport, or export it to Scandinavia. Similarly, the Notifying Party argues that if a broader market definition was used (e.g. an EU- wide market for ex-refinery sales, or wider), BP's ex-refinery sales would remain significantly below the thresholds for a vertically affected market.

(36) The Commission considers that the exact scope of the geographic market can be left open as the transaction does not give rise to serious doubts with regard to the ex-refinery sales of aviation fuel under any plausible market definition.

Into-plane supply of aviation fuel

(37) The Commission has in the past considered that the geographic scope of into-plane supply of aviation fuel is limited to each specific airport. (19)

(38) The determining factors in finding individual airports to constitute local markets include the following: (i) airlines tend to select the supplier that submits the best bid, airport by airport, according to the relative advantages of the suppliers at that location; (20) (ii) suppliers tend to require access to into-plane infrastructure and must have access to the distribution and fuelling infrastructure specific to each airport in order to supply aviation fuel to airlines; (21) (iii) on the demand side, if the price of aviation fuel increases to an unsatisfactory level at one airport, an airline is unable to turn to another airport in order to obtain the same fuel at a lower price, given the constraints connected with the availability of time slots. (22)

(39) The Notifying Party does not dispute the above mentioned geographic market definition but it claims that whereas there may be barriers that make it difficult for an airline, in the short term, to switch airports in response to an increase in the aviation fuel price, airlines are able to tanker fuel in particular in short-haul flights, allowing airlines to avoid or minimise the need to refuel at airports with higher fuel prices. (23)

(40) The large majority of the respondents to the market investigation submitted that the supply of into-plane aviation fuel is limited to each airport, as prices and other conditions regarding the contracts to supply into-plane aviation fuel are negotiated per individual airports. (24) In addition, respondents to the market investigation from the demand side submitted that they choose their into-plane fuel supplier by airport, taking into account the best offer per airport. (25)

(41) Taking into account the results of the market investigation and for the purposes of the present case, the Commission considers that the geographic scope of the market for into-plane supply of aviation fuel is limited to each specific airport.

V. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

1. Non-Coordinated Horizontal Effects

(42) The Parties' activities overlap horizontally at 6 of the 80 airports with regard to this transaction, namely (1) Stockholm-Arlanda (Stockholm), (2) Malmö, (3) Gothenburg-Landvetter (Gothenburg), (4) Copenhagen-Kastrup (Copenhagen), (5) Hamburg and (6) Amsterdam. (26) The transaction will lead to a reduction in the number of actual suppliers at Stockholm (from 3 to 2), Gothenburg (from 3 to 2), Malmö (from 3 to 2), Copenhagen (from 4 to 3), Hamburg (from 6 to 5) and Amsterdam (from 5 to 4).

1.1. Stockholm

1.1.1. Overview

(43) Stockholm airport (Arlanda) is the largest airport in Sweden and the third largest airport in Scandinavia. It handles 20.7 million passengers annually and has an annual volume of demand for aviation fuel of around […] cbm. The supply chain

switch between the two remaining suppliers and (3) there are no capacity constraints that would hinder either of the remaining two suppliers to expand production. As a result, the Notifying Party submits that market shares "tend to be relatively short-lived and not symptomatic of sustained market power". (29) Secondly, the Notifying Party submits that airlines are sophisticated customers with significant buyer power. Thirdly, the Notifying Party argues that new players can easily enter the market.

(55) In addition, the Notifying Party claims that there is no economic evidence of a relationship between the number of suppliers active at an airport and margins earned at that airport. The Notifying Party therefore argues that as long as there remain at least two strong competitors, the loss of a supplier will have no impact on prices. To reach this conclusion, the Notifying Party relies on two types of regression analyses, (1) a cross-sectional regression analysis, i.e. comparing margins across airports and assessing whether and to what extent the number of active suppliers at an airport affects the level of margins earned at that airport, and (2) a fixed effects regression analysis, i.e. comparing margins at different moments within each airport and assessing whether entries and exits of suppliers within an airport affect the level of margins earned. According to the Notifying Party, both sets of analyses found no evidence of a relationship between the number of suppliers active at an airport and margins earned at that airport. (30)

Removal of an Important Competitive Constraint

(56) The Commission took into account the Notifying Party's arguments and concedes that most airlines carry out annual tenders and that in principle there are no significant barriers to switching suppliers once a supply contract comes to an end and a new tender is organised. However, the Commission considers that these conditions are not sufficient to reach the conclusion that effective competition will be ensured even though only two suppliers will remain post-merger. In particular, the Commission considers that the presence of Shell as the only remaining competitor at Stockholm airport is not sufficient to ensure effective competition for the reasons set out below.

(57) Firstly, all suppliers do not operate with the same supply chain. As a result suppliers face different cost structures (including marginal costs), which affect their ability and incentive to offer a low price and also means that they are unlikely to be able to exert the same competitive constraint on each other. These differences may be found at any level of the supply chain, i.e. sourcing of fuel, off-airfield storage, on-airfield storage and into-plane service. In this respect, the Notifying Party's internal documents indicate […]. (31) […]. Post-transaction this constraint will disappear and Shell is unlikely to be able to compensate for this loss, given its higher marginal costs.

(58) Secondly, the customers who responded to the Commission's questionnaire confirm that SFRA and BP are close competitors and that they are exerting an important competitive constraint on each other. In particular, a large majority of customers considers SFRA to be the closest competitor to BP and a majority of them consider BP to be the closest competitor to SFRA. (32) Moreover, a large majority of customers consider SFRA as the most aggressive competitor in terms of credit terms and also (but to a lesser extent) in terms of prices. (33) The Notifying Party itself submitted a diversion ratio analysis based on the 10 largest lost contracts of BP over the last three years. This analysis shows that […] of them were won by SFRA, representing [70-80]% of BP's lost volume. This again illustrates how strong a competitive constraint SFRA is. Post-transaction this competitive constraint on BP will disappear.

(59) Thirdly, the market investigation has shown that not all fuel suppliers present in Stockholm participated in all tender procedures. (34) In particular, there are tenders in which only BP and SFRA submitted a quote. Post-merger, it is therefore likely that there will be tenders in which the merged entity will not face any competition.

(60) Fourth, some customers at Stockholm airport engage in multi-sourcing. Although the majority of airlines active in Stockholm source from a single supplier, those that multi-source are typically larger customers who account for a significant share of the overall volume supplied in Stockholm. In 2013, the Notifying Party identified […] multi-sourcing customers, […], representing [60-70]% of the overall demand in Stockholm. (35) Post-merger, if these airlines still want to multi-source (e.g. for reasons of security of supply) between two suppliers, both suppliers would face no competition on the part of the demand that they are covering. Moreover, to the extent that absent the merger they would have relied on three suppliers (Shell, BP and SFRA) for their supply of fuel, post-transaction the two remaining suppliers would have to provide a larger proportion of these customers' demand. This would imply a higher exposure to the credit risk of these airlines, which, as explained by the Notifying Party, may be contrary to the suppliers' policy. As the willingness to take a higher credit risk exposure to this airline may be limited, the two remaining suppliers would likely shorten their credit terms.

(61) Finally, the Commission considers that the econometric analysis submitted by the Notifying Party does not provide convincing evidence that no relationship exists between margins and the number of suppliers. The analysis has shortcomings with regard to the methodology, the data, the interpretation and the robustness of the results which imply that the analysis cannot be considered conclusive. (36)

(62) First, both the number of bidders for a given contract and the profitability of the contract are likely to depend on unobserved supply and demand factors. The margin-concentration analysis submitted by the Notifying Party is therefore likely to suffer from a problem of endogeneity which leads to biased and therefore unreliable results.

(63) Second, the cross-sectional analysis (i.e. comparing margins across airports) does not adequately account for unobserved differences between airports, which may affect the margins earned, such as differences in the supply chain of BP and of its competitors, differences in the level of barriers to entry and differences in the customer mix.

(64) Third, in the fixed effect analysis (i.e. focusing on the effects of entries and exits of firms within an airport), the Notifying Party only assumed a linear relationship between the number of suppliers and margins. In other words, this approach assumes that the effect on the margin of reducing the number of competitors from three to two is identical to the effect of reducing this number from eight to seven, etc. The Commission does not consider this assumption to be theoretically sound.

(65) Fourth, the data set submitted by the Notifying Party contains only few changes in the number of suppliers that are relevant to the proposed transaction. (37)

(66) Fifth, both the cross-sectional and the fixed effect analyses suffer from measurement errors. For instance, the main variable of interest (i.e. the number of suppliers) does not adequately measure the number of suppliers participating in tenders as not all suppliers participate in each tender.

(67) Moreover, it should be mentioned that the Commission replicated the Notifying Party's analysis modifying only few parameters and found preliminary indications of a negative relationship between the margins and the number of firms. (38) The Commission therefore takes the view that the results of the Notifying Party's analysis are not robust.

Insufficient Buyer Power

(68) The Notifying Party argues that airlines exercise significant countervailing buyer power by threatening to (1) leverage their demand, (2) to tanker or (3) to self- supply. However, contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that customers do not exercise significant buyer power.

Leveraging Demand across Airports

(69) Contrary to the Notifying Party’s position, the Commission does not consider that airlines exercise significant buyer power by leveraging their demand across airports. Leveraging of demand is a strategy by which airlines, when they negotiate prices for the supply at a particular airport, threaten to divert their business at other airports to other into-plane suppliers or even to divert traffic from the particular airport to other airports in order to negotiate lower prices.

(70) The information provided by the Notifying Party itself suggests that mostly larger airlines with a strong presence at several airports could envisage such a strategy. (39) Smaller airlines or airlines with a strong presence at only few airports would find it more difficult to leverage their demand.

(71) In any case, the market investigation has shown that the majority of customers have never threatened to divert business to competing suppliers also present at other airports. Similarly, from a competitor perspective, the market investigation has shown that the large majority of into-plane suppliers have never been threatened with such a strategy.

Tankering

(72) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider that airlines are able to exercise significant buyer power through the threat of tankering.

(73) Tankering is a refuelling strategy by which an airline takes on more fuel than needed at lower cost airports to cover the flight to the destination airport in order to reduce the amount of fuel they take on at the higher price destination airport.

(74) The Notifying Party submitted anecdotal evidence of tankering. (40) However, the Notifying Party itself concedes that tankering is only a viable strategy where the price difference exceeds the additional cost of carrying excess fuel (i.e. weight). (41)

(75) The market investigation suggests that tankering is usually not a viable strategy for medium or long-haul flights, since the extra weight of the additional fuel increases the overall fuel consumption of the tankering airplane and the advantage of the price difference is lost. For example, one airline noted that the "flight time from […] prevents economic tankering”.

(76) As regards Stockholm, the market investigation has shown that a majority of customers at Stockholm airport tankers never or only occasionally. Moreover, the majority of airlines tanker less than 10% of their fuel requirements. Furthermore, if the price differential for aviation fuel would increase by 5%-10% compared to other airports, the majority of customers at Stockholm airport would not significantly increase the volumes which they tanker at other cheaper airports.

(77) From a competitor perspective, the market investigation has shown that the majority of into-plane suppliers stated that airlines had never threatened them with such a strategy. Moreover, these into-plane suppliers stated that those airlines, which had threatened with such a strategy, had not succeeded in obtaining lower prices.

Self-Supply

(78) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider that airlines are able to exercise significant buyer power through the threat of self- supply.

(79) The Notifying Party itself concedes that self-supplying airlines usually have higher costs than traditional into-plane suppliers, because they have higher credit costs since their business model is perceived more risky than that of traditional into- plane suppliers and because they usually have lower volumes. (42) Self-supply is therefore typically an option only for large airlines with significant volumes of demand at the respective airport. These airlines primarily engage in self-supply to use it as a bargaining tool or to increase their insight into the supply chain costs. Based on the information provided by the Notifying Party, only SAS self-supplies at Stockholm airport.

(80) Indeed, the market investigation has shown that only very few large customers self- supply and that the extent of self-supply is usually limited to only a portion of the airline's demand. Also, almost no customer has threatened to self-supply in past negotiations.

(81) As regards Stockholm airport, the market investigation has shown that almost all customers either consider it difficult to start self-supply at Stockholm airport or have not even considered the matter. Consequently, almost no customer expressed an interest in starting to self-supply in the next 3 years.

Barriers to Entry

(82) The Notifying Party argues that (1) the Groundhandling Directive ensures non- discriminatory third party access, (2) self-supplying airlines can start supplying to other airlines, (3) new entrants can enter as shareholders in the existing infrastructure joint-ventures, (4) as throughputters as well (5) as resellers and that (6) airlines can sponsor new entry. However, contrary to the Notifying Party’s position, the Commission considers that new entrants face significant barriers to entry at Stockholm airport.

The Groundhandling Directive

(83) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that the Groundhandling Directive does not in itself ensure easy entry for new players at Stockholm airport. In that regard the Commission notes that it has conducted an impact assessment on the Groundhandling Directive. This impact assessment suggests that the current legal framework for the management of centralised infrastructure such as fuel infrastructure is inappropriate. (43)

Entry of a self-supplier in the non-self-supply business

(84) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that self-suppliers would start supplying other airlines. The Notifying Party itself concedes that self-supplying airlines frequently have higher costs of upstream supply of aviation fuel, partly due to higher credit costs. (44) The Notifying Party rightly concludes that airlines are often able to obtain better terms from traditional into-plane suppliers, especially in terms of credit. (45) It follows that self-supplying airlines are unlikely to compete with traditional into-plane suppliers in the supply of other airlines.

(85) The market investigation has shown that SAS as the only self-supplying airline at Stockholm airport has not supplied fuel to other airlines in the last 5 years.

Entry as shareholders

(86) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that it is unlikely that potential competitors, which would enter the Stockholm airport by purchasing shares in the on-airfield joint venture (AFAB) and in one of the two into-plane joint ventures (AFCO and SFS), constitute a significant competitive constraint. The Commission considers that potential entrants face significant barriers when attempting to become a member of the relevant infrastructure joint- ventures.

(87) As regards the on-airfield storage joint venture (AFAB), the Commission notes that the joint-venture agreement allows for the entry of new participants. However, the joint-venture agreement foresees that the existing shareholders have to unanimously approve the necessary increase in share capital. Also, if an existing shareholder intends to sell shares, the joint-venture agreement does not allow a new entrant to purchase those shares, but foresees that the remaining shareholders purchase the exiting shareholders' shares in equal portions.

(88) As regards the into-plane joint-ventures, there are two such providers active at Stockholm airport, namely AFCO and SFS.

(89) Regarding AFCO, the Commission notes that the joint-venture agreement allows for the entry of new participants. However, the joint-venture agreement foresees that the existing shareholders have to unanimously approve the necessary increase in share capital. Also, if an existing shareholder intends to sell shares, the joint- venture agreement foresees that the remaining shareholders have a pre-emption right.

(90) Regarding SFS, the joint-venture agreement foresees the transfer of shares to a new shareholder, but such a transfer requires the unanimous decision of the remaining shareholders.

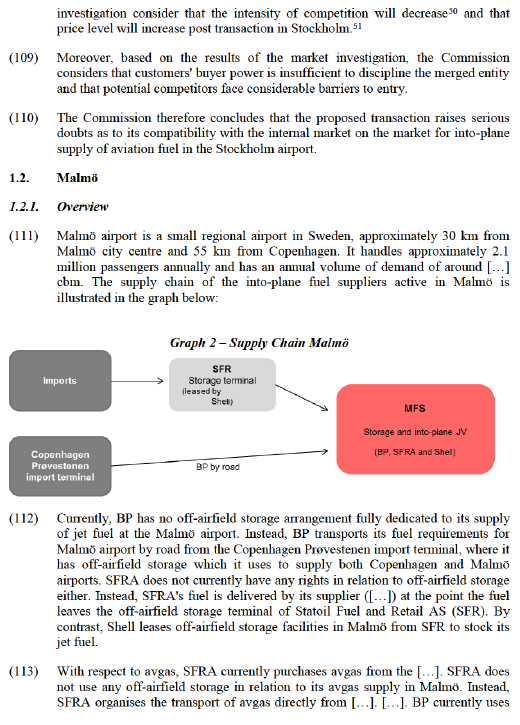

(91) As regards AFCO, two of its shareholders, Chevron and Q8, maintain dormant shareholdings in this into-plane joint-venture. However, neither of these potential competitors has shareholdings in the on-airfield storage joint-venture (AFAB). Only the third shareholder, BP, also has a share in AFAB and remains the sole active shareholder of AFCO. By contrast, Chevron and Q8 have withdrawn from the into-plane supply of aviation fuel at this airport. There are no indications that Chevron or Q8 intend to re-enter this market.

(92) The market investigation has shown that almost none of the Parties' competitors or customers expect new entry in the coming next years.

Entry as Throughputters

(93) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that throughputters constitute a significant competitive constraint at Stockholm airport.

(94) Throughputters purchase the right to use the on-airfield storage and into-plane supply infrastructure from the infrastructure joint-ventures as such or from individual shareholders without becoming a shareholder of these companies. According to the Notifying Party, throughputters profit from the fact that they do not incur large capital costs and the associated risks and liabilities. Instead, they merely pay a fee, which the owners of the infrastructure charge in proportion to their usage of the facilities.

(95) Customers generally do not consider throughputters as a significant competitive constraint at Stockholm airport, which is consistent with the fact that there are currently no throughputters active at this airport.

(96) Moreover, throughputters as potential competitors face significant barriers to entry at Stockholm airport, because they would need to agree on the terms of access with the on-airfield storage joint-venture (AFAB) and with one of the two into-plane joint-ventures (AFCO or SFS). With the exception of self-supplying shareholders (i.e. SAS) and dormant shareholders (i.e. Chevron), these joint-ventures are owned by active competitors of any potential entrant. These companies are unlikely to have an active interest in the entry of an additional competitor. Yet, as shareholders they have a significant margin of discretion in fixing the price and the terms of access for potential throughputters. In that regard, the market investigation has confirmed that no throughputter has entered Stockholm airport over the last 3 years. The Notifying Party itself concedes that, in the last five years, only […] has requested access to AFAB and SFS, but abandoned negotiations, when the joint- venture requested an up-front administration fee before starting negotiations. (46)

(97) Furthermore, even if a throughputter were to enter Stockholm airport, the market investigation has shown that many customers would prefer the offer from the traditional supplier and almost no customer would give preference to an offer at equal terms from the throughputter, mostly for reasons related to reliability and security of supply.

(98) In any case, the market investigation has shown that almost no customer or competitor expects throughputters to enter Stockholm airport in the next 3 years.

Entry as Resellers

(99) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider resellers to constitute a competitive constraint at Stockholm airport.

(100) Resellers purchase the fuel from other into-plane suppliers "at wingtip" and then sell it on to the airline. Resellers accept lower margins and offer more generous credit terms than into-plane suppliers. According to the Notifying Party, the presence of resellers has increased the competitive pressure on into-plane suppliers.

(101) Indeed, the market investigation has shown that almost no customer considers resellers as an important competitive constraint at Stockholm airport. There are currently no resellers active at Stockholm airport.

(102) The information provided by the Notifying Party suggests that resellers mainly sell to customers, which are unattractive for traditional into-plane suppliers, because they purchase relatively small volumes (e.g. general aviation) or carry a high credit risk. (47) This was confirmed by the market investigation. One customer pointed out that "[r]esellers buy the fuel from the suppliers therefore are unlikely to be more competitive". Similarly, another customer stated that their "experience is that reseller prices are always higher than traditional suppliers given that resellers purchase". Another customer concluded that "[t]heir business structure is not competitive".

Sponsor New Entry

(103) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that customers will sponsor new entry by facilitating entry of a third party supplier at Stockholm airport.

(104) The information submitted by the Notifying Party itself suggests that that an airline needs to have significant volumes of demand at a particular airport in order to sponsor entry. (48) It is therefore unlikely that airlines with average or smaller volumes would be able to generate sufficient demand to sponsor entry.

(105) Moreover, the information submitted by the Notifying Party further suggests that the airlines would need to enable the entrant's access to the infrastructure joint- ventures. (49) This is only possible for airlines which are already part of the supply chain as shareholders of the infrastructure joint ventures.

(106) As regards Stockholm airport, only one airline (SAS) is a shareholder in the on- airfield storage joint venture (AFAB) and in an into-plane joint venture (SFS). However, both joint-venture agreements would require that the remaining shareholders would approve the new entrant.

(107) The market investigation has shown that almost all customers stated that it would be difficult to sponsor such entry at Stockholm airport. Moreover, none of the customers at Stockholm airport has sponsored entry by actively facilitating entry of a third-party in this market, for example by providing them an incentive, expertise, advice or other assistance of a new into-plane supplier in the last 3 years in this airport.

Conclusion on Stockholm

(108) As explained above, the Commission considers that, even though fuel supply contracts are allocated through informal bidding processes, the transaction will remove an important competitive constraint and could result in higher prices for the into-plane supply of aviation fuel in Stockholm. This concern is confirmed by the results of the market investigation: the large majority of respondents to the market

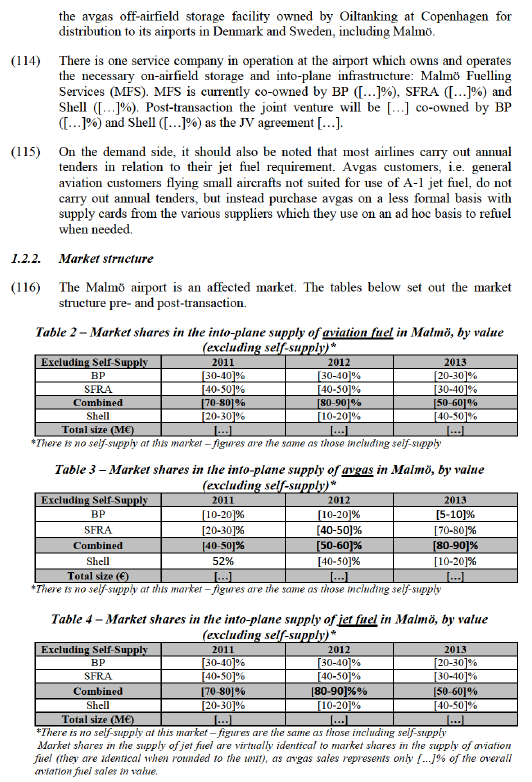

(117) Regardless of the product market definition retained, there are currently only three competing suppliers in Malmö, i.e. BP, SFRA and Shell. The transaction would further reduce the number of competitors from 3 to 2 and would thus lead to a duopoly. Moreover, the Parties combined market share remains high (i.e. above 50% in the case of aviation fuel and jet fuel and [80-90]% in the case of avgas).

1.2.3. Theory of harm

(118) Regardless of whether the Commission considers into-plane supply of avgas and of jet fuel to be one market or two separate markets, for the reasons set out below, the Commission concludes that the transaction removes an important competitive constraint. Moreover, the Commission considers that customers' buyer power is insufficient to discipline the merged entity and potential competitors face considerable barriers to entry.

The Notifying Party’s Arguments

(119) The Notifying Party submits that the market structure at the Malmö airport with only two suppliers of jet fuel and of avgas post-transaction will not impede effective competition.

(120) With respect to jet fuel, the Notifying Party argues the following. Firstly, the Notifying Party argues that effective competition will be ensured even though only two suppliers will remain post-merger, because (1) most airlines carry out annual tenders in relation to their jet fuel requirement, (2) customers can easily switch between the two remaining suppliers and (3) there are no capacity constraints that would hinder either of the remaining two suppliers to expand production. As a result, the Notifying Party submits that market shares "tend to be relatively short- lived and not symptomatic of sustained market power". (52) Secondly, the Notifying Party submits that airlines are sophisticated customers with significant buyer power. Thirdly, the Notifying Party argues that new players can easily enter the market.

(121) The Notifying Party also explains that BP has recently taken a strategic decision to terminate its off-airfield storage arrangement in Malmö […]. The Notifying Party claims that, ever since BP began transporting jet fuel from Copenhagen, […]. It estimates its 2014 market share to be approximately [0-5]%.

(122) Finally, as explained in paragraph (55) above, the Notifying Party claims that there is no economic evidence of a relationship between the number of suppliers active at an airport and margins earned at that airport.

(123) With respect to avgas, the bidding markets argument does not apply. Therefore, the Notifying Party mainly puts forward countervailing arguments. First, the Notifying Party claims that customers could purchase avgas from alternative suppliers at local airports in the area. Second, the Notifying party claims that a new entrant could easily start offering avgas at Malmö.

Removal of an Important Competitive Constraint

(124) The Commission took into account the Notifying Party's arguments and concedes that most airlines carry out annual tenders and that in principle there are no significant barriers to switching suppliers once a supply contract comes to an end and a new tender is organised. However, the Commission considers that these conditions are not sufficient to reach the conclusion that effective competition will be ensured even though only two suppliers will remain post-merger. In particular, the Commission considers that the presence of Shell as the only remaining competitor at Malmö airport is not sufficient to ensure effective competition.

(125) In the case of jet fuel, even though fuel supply contracts are allocated through informal bidding processes, the Commission considers that the transaction removes an important competitive constraint for the reasons set out below.

(126) Firstly, the customers who responded to the Commission's questionnaire confirmed that SFRA and BP are close competitors and that they are exerting an important competitive constraint on each other. In particular, a large majority of customers considered SFRA to be the closest competitor to BP and half of them considered BP to be the closest competitor to SFRA. (53) Moreover, SFRA is considered as the most aggressive competitor in terms of prices by the majority of customers while half of them consider SFRA to be the most aggressive competitor in credit terms. (54) Post-transaction this competitive constraint on BP will disappear.

(127) Secondly, some customers at Malmö airport engage in multi-sourcing. Although the majority of airlines active in Malmö source from a single supplier, those that multi-source are typically larger customers who account for a significant share of the overall volume supplied in Malmö. In 2013, the Notifying Party identified […], representing [50-60]% of the overall demand in Malmö. (55) Post-merger, if […] still wants to multi-source (e.g. for reasons of security of supply) between two suppliers, both suppliers would face no competition on the part of the demand that they are covering. Moreover, to the extent that in the absence of the transaction, the multi-sourcing airlines would have relied on three suppliers (Shell, BP and SFRA) for their supply of fuel, post-transaction the two remaining suppliers would have to provide a larger proportion of these customers' demand. This would imply a higher exposure to the credit risk of these airlines, which may be contrary to the suppliers' policy. (56) As the willingness to take a higher credit risk exposure to this airline may be limited, the two remaining suppliers would likely shorten their credit terms.

(128) Thirdly, as regards the Notifying Party's argument that BP has substantially reduced its market presence in Malmö, the Commission considers that this does not imply that in the absence of the merger BP would not have offered a competitive constraint on SFRA. First, during the last three years until 2013 BP had consistently high market shares between [20-30]% and [30-40]%. In 2014 BP was also present and the Notifying Party itself concedes that market shares in a given year tend to be relatively short-lived. (57) Second, BP is one of only three competitors at Malmö airport and the Commission has no indications that BP is likely to exit the market. Third, in view of the very recent decision of BP to transport fuel directly from Copenhagen, the Commission cannot exclude that this change in strategy by BP may have been triggered by the proposed transaction. And finally, absent the merger, BP could have renegotiated the terms of the off-airfield storage agreement that it had with Nordic Storage.

(129) Finally, as explained in paragraphs (61) et seq. above, the Commission considers that the econometric analysis submitted by the Notifying Party does not provide convincing evidence that no relationship exists between margins and the number of suppliers.

(130) In the case of avgas, as explained above, customers do not carry out annual tenders. The transaction will lead to a reduction in the number of competitors from 3 to 2. BP is one of only three competitors at Malmö airport and the Commission has no indications that BP is likely to exit. Finally, contrary to the Notifying Party's argument, the Commission considers that customers are unlikely to resort to alternative suppliers located at nearby airports if the merged entity were to increase its prices. The alternative airports mentioned by the Notifying Party are located at a distance of 50 to 100 km from Malmö. Therefore they do not constitute credible alternatives, even for general aviation customers. As a result, the Commission considers that the transaction removes an important competitive constraint for the into-plane supply of avgas at Malmö airport.

Insufficient Buyer Power

(131) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that airline customers do not exercise significant buyer power in relation to the into-plane supply of jet fuel.

Leveraging Demand across Airports

(132) Contrary to the Notifying Party’s position, the Commission does not consider that airlines exercise significant buyer power by leveraging their demand across airports (see paragraphs (69) to (71) above).

Tankering

(133) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider that airlines are able to exercise significant buyer power through the threat of tankering.

(134) Firstly, the Notifying Party itself concedes that tankering is only a viable strategy where the price difference must exceed the additional cost of carrying excess fuel (i.e. weight) (see paragraph (74) above).

(135) Secondly, from a general point of view, the market investigation has shown that neither customers nor competitors consider tankering as a significant competitive constraint (see paragraph (75) above).

(136) Thirdly, the market investigation has confirmed that the majority of customers at Malmö tankers never or only occasionally. Moreover, the majority of airlines tanker less than 10% of their fuel requirements. Furthermore, if the price differential for aviation fuel would increase by 5%-10% compared to other airports, the majority would not significantly increase the volumes which they tanker at other cheaper airports.

Self-Supply

(137) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider that airlines are able to exercise significant buyer power through the threat of self- supply.

(138) Firstly, the Notifying Party itself concedes that self-supplying airlines usually have higher costs than traditional into-plane suppliers, because they have higher credit costs since their business model is perceived more risky than that of traditional into-plane suppliers and because they usually have lower volumes (see paragraph (79) above).

(139) Secondly, from a general point of view, the market investigation has shown neither customers nor competitors consider self-supply or the threat of it as a significant competitive constraint (see paragraph (80) above).

(140) Thirdly, as regards Malmö airport, there is currently no self-supply. Moreover, the market investigation has shown that almost all customers either consider it difficult to start self-supply at Malmö airport or have not considered the matter. No customer considered that it would be easy to start self-supply at Malmö airport nor expressed an interest in starting to self-supply in the next 3 years.

Barriers to entry

(141) Contrary to the Notifying Party’s position, the Commission considers that new entrants face significant barriers to entry at Malmö airport. The Commission sets out the main reasons below. These apply to both jet fuel and avgas, unless stated otherwise.

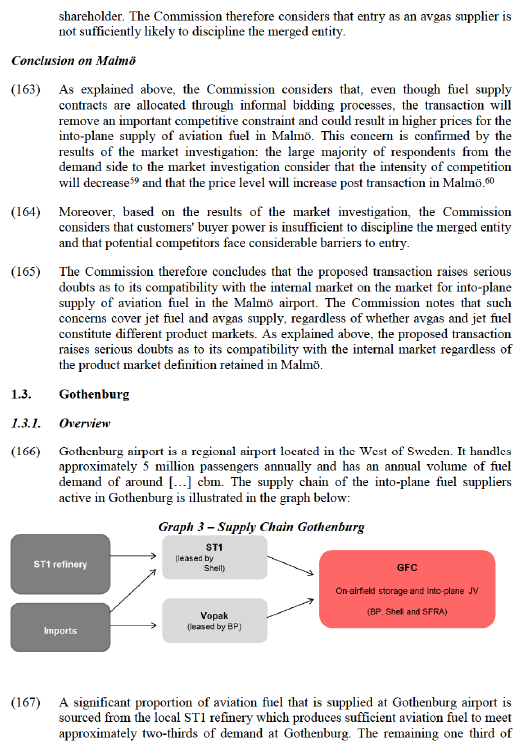

The Groundhandling Directive

(142) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that the Groundhandling Directive does not in itself ensure easy entry for new players at Malmö airport (see paragraph (83) above).

Entry of a self-supplier in the non-self-supply business

(143) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that self-suppliers would start supplying other airlines.

(144) Firstly, the Notifying Party itself concedes that self-supplying airlines usually have higher costs of upstream supply of aviation fuel, partly due to higher credit costs (see paragraph (84) above).

(145) Secondly, the market investigation has shown that there is no self-supplying airline at Malmö airport.

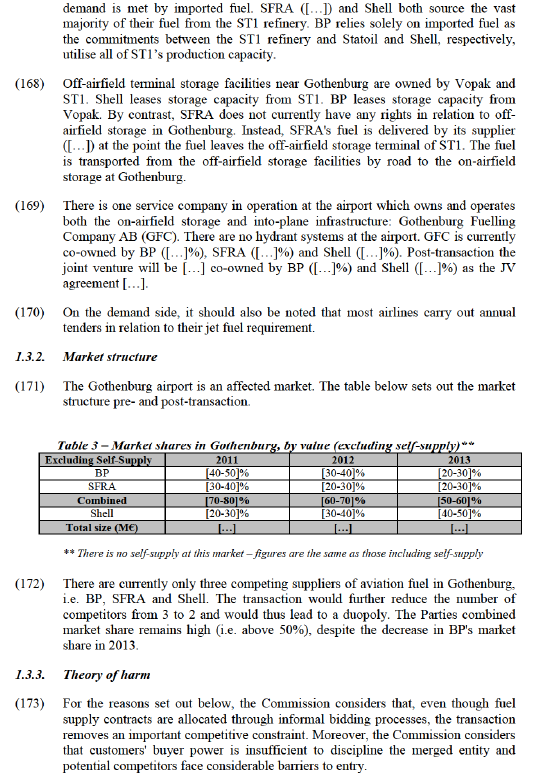

Entry as shareholders

(146) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that it is unlikely that potential competitors, which would enter the Malmö airport by purchasing shares in the only joint-venture operating both the on-airfield storage and the into-plane infrastructure (MFS), constitute a significant competitive constraint.

(147) The Commission considers that potential entrants face significant barriers when attempting to become a member of this joint-venture. The Commission notes that the joint-venture agreement allows for the entry of new participants. However, the existing shareholders' board of directors evaluates whether the applicant meets the qualifying criteria. Besides, if an additional shareholder were to enter the joint- venture through an increase in capital, the joint-venture agreement foresees that the existing shareholders have to unanimously approve the necessary increase in share capital in a general meeting. Also, if an existing shareholder intends to sell shares to a new shareholder, the joint-venture agreement foresees that the exiting shareholder first has to offer his share to the remaining shareholders in equal portions.

(148) The market investigation has shown that almost none of the market players expect new entry in the coming years.

Entry as Throughputters

(149) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that throughputters constitute a significant competitive constraint at Malmö airport.

(150) No customer considers throughputters as an important competitive constraint at Malmö airport, which is in line with the fact that there are currently no throughputters active at Malmö airport.

(151) Secondly, throughputters as potential competitors face significant barriers to entry at Malmö airport, because they would need to agree on the terms of access with the joint-venture (MFS). This joint-venture is owned by active competitors of any potential entrant that are unlikely to have an active interest in the entry of an additional competitor. Yet, as shareholders they have a significant margin of discretion in fixing the price and the terms of access for potential throughputters. In that regard, the market investigation has confirmed that no throughputter has entered Malmö airport over the last 3 years.

(152) Thirdly, even if a throughputter were to enter Malmö airport, the market investigation has shown that many customers would prefer the offer from a traditional supplier and almost no customer would give preference to an offer at equal terms from the throughputter.

(153) Lastly, the market investigation has shown that almost no customer or competitor expects throughputters to enter Malmö airport in the next 3 years.

Entry as Resellers

(154) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider resellers to constitute a competitive constraint at Malmö airport.

(155) The information provided by the Notifying Party suggests that resellers mainly sell to customers, which are unattractive for traditional into-plane suppliers, because they purchase relatively small volumes (e.g. general aviation) or carry a high credit risk. This was confirmed by the market investigation (see paragraph (102) above).

(156) The market investigation has shown that almost no customer considers resellers as an important competitive constraint at Malmö airport. This is in line with the fact that – based on the results of the market investigation - resellers are not active to any significant extent at Malmö airport.

Sponsor New Entry

(157) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that customers will sponsor new entry by facilitating entry of a third party supplier at Malmö airport.

(158) Firstly, the information submitted by the Notifying Party itself suggests that an airline needs to have significant volumes of demand at a particular airport in order to sponsor entry (see paragraph (104) above).

(159) Secondly, the information provided by the Notifying Party itself suggests that only airlines which are already part of the supply chain as shareholders of the infrastructure joint ventures would enable the entrant's access to the infrastructure joint ventures (see paragraph (105) above). However, there is currently no self- supplying airlines at Malmö airport.

(160) Thirdly, the possibility and timeliness of entry would most likely still depend on the other shareholders willingness to waive any special rights and approve the entry of a new competitor.

(161) The market investigation has shown that almost all customers stated that it would be difficult to sponsor entry at Malmö airport. Moreover, none of the customers at Malmö airport has sponsored entry by actively facilitating entry of a third-party in this market, for example by providing them an incentive, expertise, advice or other assistance of a new into-plane supplier in the last 3 years in this airport.

Entry as an avgas supplier

(162) The Notifying Party claims that a new entrant could easily start offering avgas without needing to secure access to the storage and service JV at Malmö (MFS). According to the Notifying Party, a new entrant could instead install its own small storage tank or operate on a bridger-to-bowser basis. (58) However, either of these two operation models would necessitate having access to a fuel delivery vehicle (a bowser vehicle in the case of Malmö) at the airport of Malmö. This constitutes a significant barrier to entry for two reasons. On the one hand, it would be too costly for a new entrant to acquire its own bowser vehicle and hire the necessary personnel, given the limited volumes of supply involved. On the other hand, as explained above, the Commission considers it unlikely that a new entrant would get access to the relevant infrastructure JV (MFS) either as a throughputter or a

The Notifying Party’s Arguments

(174) The Notifying Party submits that the market structure at the Gothenburg airport with only two suppliers post-transaction will not impede effective competition. Firstly, the Notifying Party argues that effective competition will be ensured even though only two suppliers will remain post-merger, because (1) most airlines carry out annual tenders in relation to their fuel requirement, (2) customers can easily switch between the two remaining suppliers and (3) there are no capacity constraints that would hinder either of the remaining two suppliers to expand production. As a result, the Notifying Party submits that market shares "tend to be relatively short-lived and not symptomatic of sustained market power". (61) Secondly, the Notifying Party submits that airlines are sophisticated customers with significant buyer power. Thirdly, the Notifying Party argues that new players can easily enter the market.

(175) The Notifying Party also explains that BP […]. As a result, BP' market share would have dropped to less than 10% in 2014.

(176) Finally, as explained in paragraph (55) above, the Notifying Party claims that there is no economic evidence of a relationship between the number of suppliers active at an airport and margins earned at that airport.

Removal of an Important Competitive Constraint

(177) The Commission took into account the Notifying Party's arguments and concedes that most airlines carry out annual tenders and that in principle there are no significant barriers to switching suppliers once a supply contract comes to an end and a new tender is organised. However, the Commission considers that these conditions are not sufficient to reach the conclusion that effective competition will be ensured even though only two suppliers will remain post-merger. In particular, the Commission considers that the presence of Shell as the only remaining competitor at Gothenburg airport is not sufficient to ensure effective competition for the reasons set out below.

(178) Firstly, the customers who responded to the Commission's questionnaire confirmed that SFRA and BP are close competitors. In particular, a large majority of customers considered SFRA to be the closest competitor to BP. (62) Moreover, a large majority of customers considered SFRA as the most aggressive competitor in terms of credit terms and also (but to a lesser extent) in terms of prices. (63) The Notifying Party itself submitted a diversion ratio analysis based on the 10 largest lost contracts of BP over the last three years. This analysis shows that […] of them were won by SFRA, representing [30-50]% of BP's lost volume. This again illustrates how strong a competitive constraint SFRA is. Post-transaction this competitive constraint on BP will disappear.

(179) Secondly, Shell's ability and incentive to compete in some tenders is likely limited by barriers to expansion. According to the Parties' internal documents, both Shell and SFRA would face increased marginal costs if they supply more than a certain volume. (64) This is because Shell and SFRA source their fuel requirement in priority from the local ST1 refinery, and this refinery has capacity constraints. Beyond a certain volume, Shell (and SFRA) would have to turn to more distant refineries, involving increased product costs. This implies that for volumes above a certain threshold, Shell will only be able to exert a milder competitive constraint on the merged entity.

(180) Thirdly, the market investigation has shown that not all fuel suppliers present in Gothenburg participated in all tender procedures. (65) In particular, there are tenders in which only BP and SFRA submitted a quote. Post-merger, it is therefore likely that there will be tenders in which the merged entity will not face any competition.

(181) Fourth, some customers at the Gothenburg airport engage in multi-sourcing. Although the majority of airlines active in Gothenburg source from a single supplier, those that multi-source are typically larger customers who account for a significant share of the overall volume supplied in Gothenburg. In 2013, the Notifying Party identified […] – representing [40-50]% of the overall demand in Gothenburg. (66) Post-merger, if these airlines still want to multi-source (e.g. for reasons of security of supply) between two suppliers, both suppliers would face no competition on the part of the demand that they are covering. Moreover, to the extent that in the absence of the transaction, the multi-sourcing airlines would have relied on three suppliers (Shell, BP and SFRA) for their supply of fuel, post- transaction the two remaining suppliers would have to provide a larger proportion of these customers' demand. This would imply a higher exposure to the credit risk of these airlines, which may be contrary to the suppliers' policy. As the willingness to take a higher credit risk exposure to this airline is likely to be limited, the two remaining suppliers will likely shorten their credit terms.

(182) Fifth, as regards the Notifying Party's argument that BP has substantially reduced its market presence in Gothenburg, the Commission considers that this does not imply that in the absence of the merger BP would not have offered any competitive constraint on SFRA. First, during the last three years until 2013 BP had consistently high market shares between [20-30]% and [40-50]%. In 2014 BP was also present and the Notifying Party itself concedes that market shares in a given year tend to be relatively short-lived. (67) Second, BP is one of only three competitors at Gothenburg airport and the Commission has no indications that BP is likely to exit the market. Third, in view of the […].

(183) Finally, as explained in paragraphs (61) et seq. above, the Commission considers that the econometric analysis submitted by the Notifying Party does not provide convincing evidence that no relationship exists between margins and the number of suppliers.

Insufficient Buyer Power

(184) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that customers do not exercise significant buyer power.

Leveraging Demand across Airports

(185) Contrary to the Notifying Party’s position, the Commission does not consider that airlines exercise significant buyer power by leveraging their demand across airports (see paragraphs (69) to (71) above).

Tankering

(186) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider that airlines are able to exercise significant buyer power through the threat of tankering.

(187) Firstly, the Notifying Party itself concedes that tankering is only a viable strategy where the price difference must exceed the additional cost of carrying excess fuel (i.e. weight) (see paragraph (74) above).

(188) Secondly, from a general point of view, the market investigation has shown that neither customers nor competitors consider tankering as a significant competitive constraint (see paragraph (75) above).

(189) Thirdly, the market investigation has confirmed that the majority of customers at Gothenburg tankers never or only occasionally. Moreover, the majority of airlines tanker less than 10% of their fuel requirements. Furthermore, if the price differential for aviation fuel would increase by 5%-10% compared to other airports, the majority would not significantly increase the volumes which they tanker at other cheaper airports.

Self-Supply

(190) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider that airlines are able to exercise significant buyer power through the threat of self- supply.

(191) Firstly, the Notifying Party itself concedes that self-supplying airlines usually have higher costs than traditional into-plane suppliers, because they have higher credit costs since their business model is perceived more risky than that of traditional into-plane suppliers and because they usually have lower volumes (see paragraph

(79) above).

(192) Secondly, from a general point of view, the market investigation has shown that neither customers nor competitors consider self-supply or the threat of it as a significant competitive constraint (see paragraph (80) above).

(193) Thirdly, as regards Gothenburg airport, there is currently no self-supply. Moreover, the market investigation has shown that almost all customers either consider it difficult to start self-supply at Gothenburg airport or have not considered the matter. No customer considered that it would be easy to start self-supply at Gothenburg airport. Consequently, almost no customer expressed an interest in starting to self-supply in the next 3 years.

Barriers to entry

(194) Contrary to the Notifying Party’s position, the Commission considers that new entrants face significant barriers to entry at Gothenburg airport.

The Groundhandling Directive

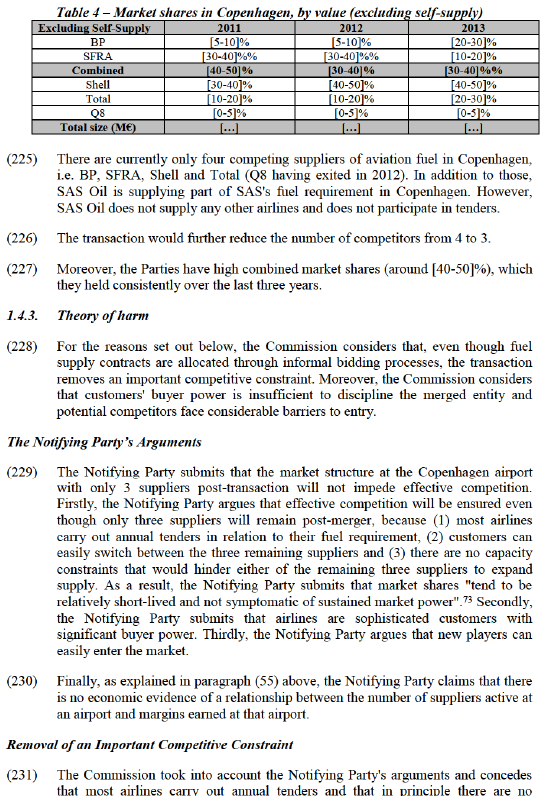

(195) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that the Groundhandling Directive does not in itself ensure easy entry for new players at Gothenburg airport (see paragraph (83) above).

Entry of a self-supplier in the non-self-supply business

(196) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that self-suppliers would start supplying other airlines.

(197) Firstly, the Notifying Party itself concedes that self-supplying airlines usually have higher costs of upstream supply of aviation fuel, partly due to higher credit costs (see paragraph (84) above).

(198) Secondly, the market investigation has shown that there is no self-supplying airline at Gothenburg airport.

Entry as shareholders

(199) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers that it is unlikely that potential competitors, which would enter the Gothenburg airport by purchasing shares in the only joint-venture operating both the on-airfield storage and the into-plane infrastructure (GFC), constitute a significant competitive constraint.

(200) The Commission considers that potential entrants face significant barriers when attempting to become a member of this joint-venture. The Commission notes that the joint-venture agreement allows for the entry of new participants. However, the existing shareholders' operating committee evaluates whether the applicant meets the qualifying criteria. Besides, if an additional shareholder were to enter the joint- venture through an increase in capital, the joint-venture agreement foresees that by default all resolutions at shareholder meetings shall be passed with the unanimous vote of all the members. Also, if an existing shareholder intends to sell shares to a new shareholder, the joint-venture agreement foresees that the exiting shareholder first has to offer his share to the remaining shareholders in equal portions.

(201) The market investigation has shown that almost none of the market players expect new entry in the coming next years.

Entry as Throughputters

(202) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that throughputters constitute a significant competitive constraint at Gothenburg airport.

(203) Firstly, the market investigation has shown that almost none of the customers consider throughputters as an important competitive constraint at Gothenburg airport. This is in line with the fact that there are currently no throughputters active at Gothenburg airport.

(204) Secondly, throughputters as potential competitors face significant barriers to entry at Gothenburg airport, because they would need to agree on the terms of access with the joint-venture (GOT). This joint-venture is owned by active competitors of any potential entrant that are unlikely to have an active interest in the entry of an additional competitor. Yet, as shareholders they have a significant margin of discretion in fixing the price and the terms of access for potential throughputters. In that regard, the market investigation has confirmed that no throughputter has entered Gothenburg airport over the last 3 years.

(205) Thirdly, even if a throughputter were to enter Gothenburg airport, the market investigation has shown that a significant number of customers would prefer the offer from a traditional supplier and almost no customer would give preference to an offer at equal terms from the throughputter.

(206) Lastly, the market investigation has shown that almost no customer or competitor expects throughputters to enter Gothenburg airport in the next 3 years.

Entry as Resellers

(207) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission does not consider resellers to constitute a competitive constraint at Gothenburg airport.

(208) The information provided by the Notifying Party suggests that resellers mainly sell to customers, which are unattractive for traditional into-plane suppliers, because they purchase relatively small volumes (e.g. general aviation) or carry a high credit risk. This was confirmed by the market investigation (see paragraph (102) above).

(209) The market investigation has shown that almost no customer considers resellers as an important competitive constraint at Gothenburg airport. This is in line with the fact that – based on the results of the market investigation - resellers are not active to any significant extent at Gothenburg airport.

Sponsor New Entry

(210) Contrary to the Notifying Party's position, the Commission considers it unlikely that customers will sponsor new entry by facilitating entry of a third party supplier at Gothenburg airport.

(211) Firstly, the information submitted by the Notifying Party itself suggests that an airline needs to have significant volumes of demand at a particular airport in order to sponsor entry (see paragraph (104) above).

(212) Secondly, the information provided by the Notifying Party itself suggests that only airlines which are already part of the supply chain as shareholders of the infrastructure joint ventures would enable the entrant's access to the infrastructure joint ventures (see paragraph (105) above). However, there are currently no self- supplying airlines at Gothenburg airport.

(213) Thirdly, the possibility and timeliness of entry would most likely still depend on the other shareholders' willingness to waive any special rights and approve the entry of a new competitor.

(214) The market investigation has shown that almost all customers stated that it would be difficult to sponsor entry at Gothenburg airport. Moreover, none of the customers at Gothenburg airport has sponsored entry by actively facilitating entry of a third-party in this market, for example by providing them an incentive, expertise, advice or other assistance of a new into-plane supplier in the last 3 years in this airport.

Conclusion on Gothenburg

(215) As explained above, the Commission considers that, even though fuel supply contracts are allocated through informal bidding processes, the transaction will remove an important competitive constraint and could result in higher prices for the into-plane supply of aviation fuel in Gothenburg. This concern is confirmed by the results of the market investigation: the majority of respondents from the demand side to the market investigation consider that the intensity of competition will decrease (68) and that price level will increase post transaction in Gothenburg. (69)

(216) Moreover, based on the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers that customers' buyer power is insufficient to discipline the merged entity and potential competitors face considerable barriers to entry.

(217) The Commission therefore concludes that the proposed transaction raises serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market on the market for into-plane supply of aviation fuel in the Gothenburg airport.

1.4. Copenhagen

1.4.1. Overview

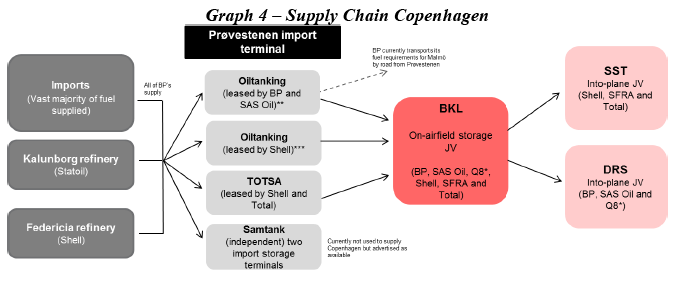

(218) Copenhagen airport is the largest airport in Denmark and Scandinavia. It handles 24.1 million passengers annually and has an annual volume of demand for aviation fuel of around […] cbm. The supply chain of the into-plane fuel suppliers active in Copenhagen is illustrated in the graph below.

(219) The vast majority of the aviation fuel supplied at Copenhagen airport is imported. However, SFRA and Shell source part of their fuel requirement respectively from Statoil’s Kalundborg refinery and Shell's refinery in Fredericia. By contrast, BP currently imports all of its fuel requirements. As regards imports, to maximise efficiencies, a supplier typically brings in a large vessel loaded with fuel – this cargo is “broken” between the into-plane suppliers ex-ship. As part of this process, the most efficient model for each into-plane supplier is to fill their storage tanks with as large volumes as possible to minimise the number of shipments required.

(220) There are three off-airfield storage sites owned respectively by Oiltanking, TOTSA (the trading and shipping arm of Total) and Samtank owns two storage tanks which are currently not used to supply Copenhagen but which are being advertised as available. Oiltanking leases storage capacity to BP, SAS Oil and Shell while TOTSA leases storage capacity to Shell and Total. SFRA's fuel is delivered by its supplier ([…]) at the point the fuel leaves the off-airfield storage terminal.

(221) Fuel is then transferred from the off-airfield terminal storage facilities via pipeline to the on-airfield storage site at Copenhagen, which is operated by the airport's main into-plane suppliers as a joint-venture ("BKL"). (70) BKL is currently co-owned by BP ([…]%), SFRA ([…]%), Shell ([…]%), Total ([…]%), SAS Oil ([…]%) and Q8 ([…]%). (71) Post-transaction the joint venture will be equally co-owned by BP ([…]%), Shell ([…]%), Total ([…]%), SAS Oil ([…]%) and Q8 ([…]%) as the JV agreement […]. BKL operates both the on-airfield storage and the hydrant system. BKL also owns and operates the pipeline from Copenhagen’s Prøvestenen import terminal to the airport.

(222) The into-plane suppliers then hand over the actual into-plane supply to an into- plane service provider, which pumps the aviation-fuel from the hydrant system via a dispenser vehicle into the aircraft. Currently, there are two such providers active at Copenhagen airport. DRS is an into-plane service provider co-owned by BP ([…]%), SAS Oil ([…]%) and Q8 ([…]%) (72); and SST is an into-plane service provider owned by Shell ([…]%), SFRA ([…]%) and Total ([…]%).

(223) On the demand side, it should also be noted that most airlines carry out annual tenders in relation to their jet fuel requirement.

1.4.2. Market Structure

(224) The Copenhagen airport is an affected market. The table below sets out the market structure pre- and post-transaction.

significant barriers to switching suppliers once a supply contract comes to an end and a new tender is organised. However, the Commission considers that these conditions are not sufficient to reach the conclusion that effective competition will be ensured even though only three suppliers will remain post-merger. In particular, the Commission considers that the presence of Shell and Total as the two only remaining competitors to the merged entity at Copenhagen airport is not sufficient to ensure effective competition for the reasons set out below.

(232) Firstly, the customers who responded to the Commission's questionnaire confirmed that SFRA and BP are close competitors. In particular, almost half of the customers consider SFRA to be the closest competitor to BP. (74) Moreover, a large majority of customers considered SFRA as the most aggressive competitor in terms of credit terms. (75) Post-transaction this competitive constraint will disappear.

(233) Secondly, the market investigation indicated that there are likely significant barriers to expansion in relation to Copenhagen. More specifically, where a supplier is operating at close to 100% of its capacity, any significant volume increase would either require additional investment (e.g. long term lease of additional off-airfield capacity) or involve operating at higher variable costs. It is unclear whether suppliers would be willing to incur additional fixed costs, not knowing exactly how much additional volume of supply they could expect and for how long. Therefore, it is unclear whether such supplier would exert any significant competitive constraint on the merged entity in at least part of the tenders.

(234) Thirdly, the Notifying Party's internal documents indicate that Shell is less competitive beyond a certain volume. This is because Shell relies on two sources of fuel for its supply in Copenhagen airport: a local refinery (Federicia refinery) and imports. Beyond a certain volume, Shell has to rely on more expensive imports, as the volume which can be sourced from the local refinery is exhausted. (76) This implies that for tenders beyond this volume threshold, Shell will only be able to exert a milder competitive constraint on the merged entity.

(235) Fourthly, the merger is likely to trigger a unit cost increase for the two remaining competitors (Shell and Total). This is because currently, Statoil and Air BP are shareholders of the two competing into-plane services companies, respectively SST (Shell/SFRA/Total) and DRS (BP/SAS). Post-merger it is likely that the merged entity will want to transfer all of the Statoil customers from SST to the other into- plane company DRS. This would significantly reduce the volume of fuel handled by SST and instead increase the volume of fuel handled by DRS. As a result, SST will likely have over-capacity (i.e. too many trucks and personnel) and will therefore experience higher unit costs. Consequently, Shell and Total are likely to operate at a cost disadvantage compared to BP/SFRA, and the competitive constraint they are currently able to exert on the Parties is likely to be reduced as a result of the transaction. The Notifying Party itself voiced a similar concern […]. (77)

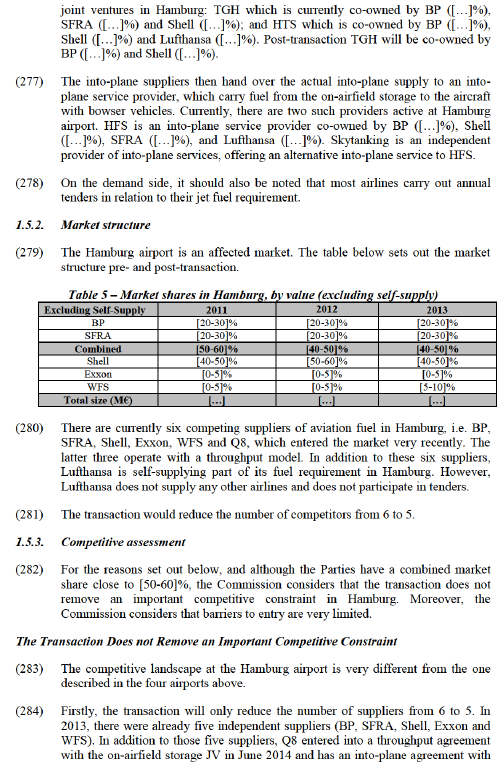

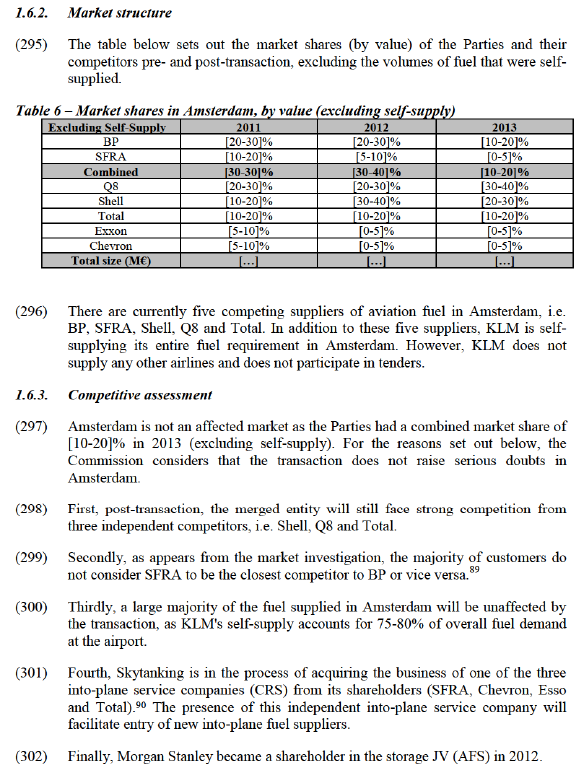

(236) Fifth, the market investigation has shown that not all fuel suppliers present in Copenhagen participated in all tender procedures. (78) There were even cases where only BP and SFRA submitted a quote. Post-merger, it is therefore likely that there will be tenders in which the merged entity will face no competition at all.