Commission, August 28, 2019, No M.9369

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

PAI PARTNERS / WESSANEN

Subject: Case M.9369 – PAI Partners/Wessanen

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 23 July 2019, the European Commission received notification of a concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation which would result from a proposed transaction by which PAI Partners SAS (“PAI Partners”, France) intends to acquire sole control, within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of that regulation, over the whole of Koninklijke Wessanen N.V. (“Wessanen”, Netherlands) (the “Transaction”). In this Decision PAI Partners is also referred to as ‘the Notifying Party’. PAI Partners and Wessanen are collectively referred to as the “Parties”.

1. THE PARTIES AND THE TRANSACTION

(2) PAI Partners is a European private equity firm headquartered in Paris. It is an independent company, owned by its partners, which manages and/or advises dedicated private equity funds with a value of more than EUR 12.3 billion.

(3) PAI Partners’ current buyout funds include PAI Europe IV, PAI Europe V, PAI Europe VI and PAI Europe VII, as well as several co-investment funds. PAI Partners seeks to acquire Wessanen through PAI Europe VII.

(4) PAI Partners’ portfolio includes Labeyrie Fine Foods SAS (“Labeyrie”, France) and Refresco Group N.V. (“Refresco”, the Netherlands), which are managed by PAI Europe VI. Labeyrie is active globally in the supply of fine and gourmet foods including pâtés, foie gras, crustaceans, fish, olives and other foods, and owns seven different brands: Labeyrie, Delpierre, Blini, L’Atelier Blini, Père Olive, Comptoir Sushi and Ovive. Refresco is active in the bottling of different types of drinks (both non-alcoholic beverages and alcoholic beverages, and both carbonated soft drinks and non-carbonated soft drinks) in different types of packaging (e.g. in carton, aseptic PET (“APET”), cans and glass).

(5) Wessanen is a publicly listed company active in the supply of food products (notably in Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom). Since 2015, Wessanen focuses exclusively on healthy and sustainable food.

(6) The Transaction will take place through a recommended public takeover offer under Dutch law. [Details on the creation of a bidding vehicle ("Bidco") between PAI Partners and a "Co-Investor"]3

(7) On 10 April 2019, Bidco and Wessanen entered into a merger agreement pursuant to which Bidco agreed to make a recommended full public offer for all issued and outstanding ordinary shares in the capital of Wessanen.

(8) Upon closing of the public offer, PAI Partners and the Co-Investor will enter into a shareholders’ agreement further describing the rights attached to their shares (the “SHA”). The SHA grants PAI Partners the possibility of exercising decisive influence over Wessanen for the following reasons: […]456.

(9) […].78 91011

(10) It follows that PAI Partners will solely and indirectly control Wessanen upon completion of the Transaction. Therefore, the Transaction would result in a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

2. UNION DIMENSION

(11) The Parties have a combined aggregate worldwide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (PAI Partners: EUR 12 183.9 million; Wessanen: EUR 628.4 million).12 Each of them has a Union-wide turnover in excess of EUR […] (PAI Partners: EUR […]; Wessanen: EUR […]), but neither of the Parties achieves more than two-thirds of their aggregate Union-wide turnover within one and the same Member State. The concentration therefore has a Union dimension within the meaning of Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

3. MARKET DEFINITION

3.1. Introduction

(12) Both parties are active in the supply of various food products to retailers in different European countries (Section 3.2). The Parties are also active in the market for bottling and supply of non-alcoholic beverages, which gives rise to horizontal overlaps and vertical relationships (Section 3.3).

3.2.Supply of food products

(13) The Parties activities, leading to putatively affected markets, overlap in the supply of food products in France. This section discusses, first, possible market segmentations that can be made across all or most types of food and, second, the specific types of food that give rise to affected markets. The following market segmentations are considered cumulatively when assessing the likely competitive effects of the Transaction:· Section 3.2.1 assesses the possible market segmentation between the supply to retailers of branded products, on the one hand, and private label products, on the other.· Section 3.2.2 assesses the possible segmentation between the supply of traditional food and the supply of organic and healthy food; within the supply of organic and healthy food, it will also assess the possible distinction between the specific retail channels, i.e. the supply to health food stores and to conventional retail outlets such as supermarkets and hypermarkets.· Sections 3.2.3 to 3.2.8 will assess the markets by type of food, where the Transaction gives rise to affected market under the narrowest possible definition. All affected markets would be in France. In particular, the following markets regarding the supply to retailers will be discussed: smoked salmon (Section 3.2.3), secondary processed herring (Section 3.2.4), secondary processed mackerel (Section 3.2.4), savoury bread toppings (Section 3.2.5), pre-packaged consumable olives (Section3.2.6), bite-size savoury snacks (Section 3.2.7), and bread substitutes (Section 3.2.8).13

3.2.1. Possible segmentation of private label and branded products

(14) PAI Partners supplies both private label and branded food products, while, for the considered product markets, Wessanen exclusively supplies branded food products.

(15) The Parties submit that, for all reportable markets, the relevant branded products are competitively constrained by private label products and that, as such, they both form part of the same product market.14

(16) In this regard, the Parties first submit that private label products and branded products are produced on the same production lines and do not require significant investments in order to switch between the production of the two types of products.15 Second, the Parties argue that private label represents an important share of each of the reportable markets16, which significantly increases the countervailing buying power of retailers during contract negotiations with suppliers, such as the Parties.17 Third, the Parties submit that their branded products compete for shelf space with private label products and that they take private label into account when making strategic pricing and/or marketing decisions.18 Fourth, private label products carry different quality ranges in their assortment that are benchmarked against the quality standard of branded products.19

(17) Some of the Parties’ internal documents show that they regard branded products and private label products as belonging to the same product market.20 The Parties also submit that a number of third party market reports (IRI, Nielsen, ILEC and Kantar) take into account private label products for the calculation of the market share of branded products for the relevant markets.21

(18) In a previous decision concerning frozen snacks, the Commission considered that private label frozen snacks and branded frozen snacks belong to a single differentiated product market where they exert on each other some degree of competitive pressure.22 In another decision concerning the markets for mustard, mayonnaise, salad sauces and olive oil, the Commission considered branded products and private label products as part of a single market despite the existing price gap between the two and noted that market shares gained by private labels were to the expense of branded products.23 In other decisions, the Commission took account of the market share represented by private label products on the total market.24

(19) The market investigation provided some indications suggesting that branded products and private label products may belong to separate product markets. A majority of customers responding to the market investigation indicated that they organise separate selection procedures for purchasing branded products and private label products.25 Namely, branded products tend to be sourced through bilateral negotiations while private label products tend to be sourced through tenders or even in-house production.26 Some of these customers also stated that they have different internal teams in charge of negotiating the purchase of branded products and private label products.27 One customer explained that it chooses branded products based on relevance of offer and brand notoriety.28 Further, there is likely also a different price positioning for private label and branded products.29

(20) Some competitors who responded to the market investigation also indicated that their customers organise separate selection procedures between branded and private label products for some specific products.30

(21) At the same time, the market investigation provided indications that branded and private label products can belong to the same market. A majority of customers responding to the market investigation indicated that final consumers, who drive the retailers’ demand for specific type of food products, do not perceive a difference in quality between branded products and private label products,31 with possible variations depending on the specific product.32

(22) In this regard, the Parties have expressed that it is uncommon for manufacturers to focus exclusively on private label products and that they are not aware of any manufacturer that exclusively produces private label products33, which would indicate that suppliers may switch from supplying branded to private label products and the other way around.

(23) In light of the above considerations and taking account of the results of the market investigation, and given that the concentration would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market even under the narrowest plausible product market definition, the Commission will leave open the question whether branded and private label products belong to the same or separate markets.

3.2.2.Retail of organic food products

(24) Wessanen is active in the organic and health food products through its main brands in France Bjorg and Bonneterre.34 PAI Partners, through Labeyrie, is mainly active in the supply of conventional food products, but also offers organic quality for some of its products.

(25) The Parties submit that organic products compared to non-organic (or conventional) products are priced higher and have higher production costs because they need to comply with the standards for organic food.35 Second, consumers consider organic products healthier and better for environment or animal welfare.36 Third, organic products are typically sold in different stores or on different shelves in the same retail outlet.37 However, the Parties consider that while competition between different organic brands is higher than between organic and non-organic, both types of products compete.38

(26) The Parties also submit that they focus on different customers and sell their products to different outlets within the retail channel.39 Labeyrie mainly sells to hyper- and supermarkets (conventional retail outlets). By contrast, Wessanen’s products are sold on the dedicated organic shelves in the conventional retail outlets and in health food stores (“HFS”).40 The Parties submit that Bonneterre branded products are sold only in HFS, while Bjorg branded products are sold in the organic shelves of the conventional retail outlets.41

(27) In its previous decisions related to certain food products, the Commission considered whether organic and conventional products belong to the same market. In Total Produce/Dole Food Company, the Commission established that it was justified to define separate markets for organic bananas and conventional products42, while in other cases it left the market definition open43 or did not consider it necessary to define a separate product market for organic produce.44

(28) As highlighted in the internal documents of the Parties, the organic food market has been constantly growing: […].45 However, it is still small compared to the conventional food retail.46 Although the results of the market investigation in the present case suggest that organic and non-organic products are largely considered as alternatives,47 there are also indications that organic food products may belong to a separate market. First, organic products are generally sold at a premium price compared to conventional products.48 Second, in light of the growing demand for organic products and the increasing offer of organic versions of conventional products49, organic and conventional products could be seen more as complements50, rather than substitutes, for retailers supplying both product categories. Third, the presence of special retail outlets dedicated to organic food (health food stores) indicates that from a demand side perspective, conventional and organic products are at least for some retailers not interchangeable. However, the Commission also considers that the degree of substitutability may differ depending on product category and change in time.

(29) The main retail channels in France for retail of organic food products are conventional supermarkets and specialised health food stores. Based on the internal documents of the Parties, conventional retail stores have a share of approximately [40-50]% of all organic food retail, while [30-40]% of organic food sales go to health food stores.51 Organic food in conventional retail chains can be found either on the dedicated organic shelves, where most of the organic products are placed, or in a shelf together with conventional non-organic products, but clearly labelled as organic.52

(30) Health food stores compared to conventional retailers have a wider range of organic products offered at a premium price.53 Health food stores seek to differentiate from conventional retailers also by supplying different organic brands54 and developing their own organic private labels.55 For example, Wessanen has brands dedicated to conventional retail outlets (e.g. Bjorg) and other for health food stores (e.g. Bonneterre). A competitor explained that health food stores focus on different customers: conscious buyers of organic products tend to shop in specialised stores, while occasional consumers of organic products tend to choose products in the organic shelves of the conventional retail stores.56 Competitors responding to the Commission’s market investigation indicated that it is not possible to compete effectively with the same brand in health food stores and conventional retail outlets.57 While not necessarily applicable in all cases, to all products and brands, the results of the market investigation suggest that different brands tend to be offered in HFS and conventional retail stores.58 As one customer explained: “No, brands are generally different (even if the supplier is the same) because consumer perceives organic shops as specialised organic outlets and does not expect to find the same brands as in conventional retail outlets”59. A competitor also submitted: “Health food stores want dedicated brands and products in order to avoid competition based on prices from supermarkets”60. Accordingly, Wessanen has developed two different brands and different marketing strategy for the supply to the two retail channels, which constitute different set of customers.

(31) As a response to the growing demand for organic food products61, French retail chains are developing private label products to cover a broad range of product categories and acquire existing or open new health food stores.62 It is expected that conventional retail chains will keep gaining market share,63 while health food store growth will slow down due to stronger competition.64 It is also considered that conventional retailers by enlarging their offer want to appeal to health food stores consumers and that this business model will blur the lines between the two retail channels and increase competition.65 While it is expected that organic food products will play a larger role for conventional retailers, there is no indication that this will blur the distinction between the supply of organic and conventional food products.

(32) Along these lines, Wessanen’s internal strategy documents explain: […].66 […].67

(33) In light of the above considerations and taking account of the results of the market investigation, and given that the concentration would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market even under the narrowest plausible product market definition, the Commission will leave open the question whether organic and conventional food products belong to the same market. The Commission does not find that there are separate markets for the supply of organic products to conventional retail stores and health food stores.

3.2.3.Secondary processed salmon

(34) Secondary processed salmon includes the transformation of primary processed salmon into processed products, such as salmon portions, ready-made meals and smoked salmon.68 In relation to secondary processed salmon, the Parties’ activities, which give rise to a potentially affected market, overlap in the supply of smoked salmon in France.69

3.2.3.1. Commission’s precedents

(35) The Commission considered in Marine Harvest/Morpol that the market for salmon farming and primary processing of salmon can be distinguished from the market for secondary processing of salmon.70

(36) Moreover, the Commission suggested that organic salmon and non-organic salmon may belong to separate product markets, due notably to the substantial differences in price, even if the exact market definition was left open.71

(37) As regards the possible distinction between the different types of secondary processed salmon, the market investigation in Marine Harvest / Morpol suggested that smoked salmon is often used as a festive product and is not consumed on the same occasion as fresh and frozen salmon.72 However, the Commission ultimately left the relevant product market definition open.73

(38) As regards the relevant geographic market, the Commission considered in Marine Harvest/Morpol that it could not be excluded that the market for smoked salmon was national in scope.74 The Commission took into account the different preferences and different roles played by brands at Member State level. However, the Commission left the exact geographic definition open as it would not have changed the outcome of the competitive assessment in that case.

3.2.3.2. The Parties’ view

(39) The Parties argue that there is a single relevant market for the sale of secondary processed salmon products and that the market should not be further segmented by processing type or between organic and non-organic secondary processed salmon products.75

(40) The Parties also submit that branded secondary processed salmon and private label products belong to the same market because private label products carry different quality ranges in their assortments and therefore exert competitive pressure on all types of branded products.76 Accordingly, suppliers of branded products need to take competitive pressure from private labels into account when they determine strategy, pricing and marketing campaigns and vice versa.77

(41) As regards geographic market definition, the Parties do not express their view but submit market data on the national market basis.78

3.2.3.3. The Commission’s assessment and conclusion

(42) On the one hand, the results of the market investigation do not support the Parties’ view that there is one single relevant market for secondary processed salmon. All respondents to the Commission’s market investigation have indicated that smoked salmon belongs to a different market than other secondary processed salmon products.79 A customer responding to the Commission’s request for information submitted: “Smoked salmon is considered as a festive product and not as an everyday product such as prepared meal or fresh salmon”.80

(43) On the other hand, the market investigation in the present case suggests that organic smoked salmon and non-organic smoked salmon are largely considered by the Parties’ customers as alternatives.81

(44) In light of the above considerations and taking account of the results of the market investigation, and given that the concentration would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market even under the narrowest plausible product market definition, the Commission will leave open the question whether smoked salmon belongs to a separate market, and whether the distinction between organic and non-organic secondary processed salmon would be justified.

(45) As regards the relevant geographic market, the market investigation in the present case suggests that the markets for smoked salmon and organic smoked salmon are national in scope.82

3.2.4. Secondary processed pelagic fish, in particular herring and mackerel

(46) Mackerel, herring and sardines are pelagic fish.83 In relation to secondary processed pelagic fish, the Parties’ activities, which give rise to a potentially affected market, overlap in the supply of secondary processed herring and secondary processed mackerel in France.84

(47) As regards secondary processed herring, PAI Partners sell marinated and smoked herring sold in the chilled department of the retail store, while Wessanen only sells smoked herring sold in the chilled department of the retail store.85

(48) As regards secondary processed mackerel, PAI Partners is active only in the supply of smoked mackerel sold in the chilled department of the retail store, while Wessanen sells smoked mackerel and one canned mackerel product in France.86

3.2.4.1. Commission’s precedents

(49) The Commission considered that secondary processing of pelagic fish is a distinct market from primary processing and includes the transformation of primary processed pelagic fish into processed products, such as smoked fish and marinated fish.

(50) Further, the Commission considered that the secondary processing of pelagic fish could be segmented into separate markets according to pelagic fish species (i.e. mackerel, herring, sardines), since different species are processed with different production technology (smoking, marinating or canning) and because competitive conditions may differ for each species because of different supply quotas in the EEA.87

(51) As regards the geographic dimension of the relevant market, the Commission considered the national and the EEA dimension for the market of secondary processed pelagic fish.88

3.2.4.2. The Parties’ view

(52) The Parties consider the relevant markets to be the market for (i) the sale of secondary processed herring products, and (ii) the sale of secondary processed mackerel products.89 The Notifying Party submits that the relevant market defined by the specific species of pelagic fish does not need to be further segmented by processing type, because pelagic fish such as herring and mackerel can be prepared in different styles (e.g. cooked, marinated, and smoked), and can be sold in different packaging (i.e. cans, plastic packaging, glass jars, etc.).90 For example, smoked herring packaged in cans exerts a competitive constraint on herring packaged in plastic containers and sold in the daily fresh department of retail stores. Since both products are similar in terms of taste, texture and consumption occasion, they are substitutable from a consumer perspective.91

(53) Further, the Notifying Party submits that private label have a strong position on the market and referring to the same reasons as argued in relation to smoked salmon products consider that private label and branded products belong to the same market.92

(54) By referring to the Commission’s decisional practice regarding secondary processed salmon, the Parties submit that the geographic market for secondary processed herring and mackerel products are national in scope or EEA wide.93

3.2.4.3. The Commission’s assessment and conclusion

(55) The results of the market investigation suggest that the distinction between the pelagic fish species is relevant. In particular, the Parties’ customers responding to the Commission’s request for information considered that secondary processed herring is different from secondary processed mackerel.94 For example, a customer submitted: “Herring is often consumed prepared or in brine, while mackerel is more often consumed in canned”.95

(56) As regards the potential distinction by type of processing, the majority of customers and competitors who responded to the Commission’s request for information have submitted that canned herring or canned mackerel cannot be considered as alternatives for [fresh]96 smoked or marinated herring or mackerel respectively.97 As one customer explained: “Consumers do not consider these products as potential alternatives, as they meet different needs. Canned products are intended to be kept longer”.98 Moreover, as another customer submitted, there are differences in taste and positioning.99

(57) In light of the above, the Commission will assess the likely effects of the concentration in relation to potentially relevant markets for secondary processed mackerel and secondary processed herring sold in the chilled department of a retail store, which would be the narrowest plausible market definition, rather than on the broader market for secondary processed pelagic fish. However, for the purpose of this case, the exact product market definition can be left open as this would not change the outcome of the competitive assessment.

(58) The market investigation in the present case suggest that the markets for secondary processed herring products and secondary processed mackerel products are national in scope.100

3.2.5. Savoury bread toppings, in particular vegetable-based savoury bread toppings and taramasalata

(59) Both Parties are active in the sale of savoury bread toppings to retailers. Savoury bread toppings can include various vegetable spreads, seafood-based spreads and meat-based spreads.101

(60) Wessanen, via its brands Bonneterre, Bjorg and Tartex102, sells fresh and ambient vegetable-based bread toppings (e.g. guacamole ) and one type of fish-based bread topping (i.e. taramasalata based on cod eggs).103 PAI Partners, via its brands Atelier Blini, Blini, Père Olive, and King Cuisine sells fresh vegetable-based (e.g. guacamole) and fish-based (e.g. taramasalata) bread toppings but does not sell any ambient savoury bread toppings.104 While Wessanen only offers branded products, PAI Partners supplies branded as well as private label savoury bread toppings.

3.2.5.1. Commission’s precedents

(61) In its previous decision, the Commission considered that sweet spreadable products can be distinguished from savoury spreadable products, but left the market definition open.105 In Orkla/Rieber & Son106, the Commission mentioned seafood-based savoury bread toppings among the nationally affected markets.

(62) As regards the geographic market, the Commission has not previously considered the geographic dimension of the relevant market for savoury bread toppings. However, as regards the manufacturing and sale of sweet spreadable products, the Commission considered that the market is at least national in scope, but ultimately left the exact geographic definition open.107 The Commission took into account differences in customers’ preferences and taste, and the conducting of negotiations on a national basis.

3.2.5.2 The Parties’ view

(63) The Parties consider that the relevant market for bread toppings can be segmented into two distinct markets: the sale of sweet bread toppings and savoury bread toppings. The Parties also submit that the market for savoury bread toppings could potentially be further segmented into (i) seafood-based bread toppings; (ii) meat- based bread toppings; and (iii) vegetable-based bread toppings.

(64) As regards the vegetable-based spreads, the Parties submit that vegetable-based bread toppings include all different types of products such as hummus, tapenades, vegetable spreads, guacamole.108 From a demand side perspective, customers that are looking for vegetable-based spreads to use as either appetisers, cocktail snacks or as part of a main course, will typically consider the whole range of vegetable-based spreads largely substitutable.109 Similarly, from the supply-side perspective, the Parties submit that suppliers of vegetable-based bread toppings supply different types of vegetable spreads ranging from guacamole and hummus to vegetable mixes.110 The Parties submit that for the same reasons the further segmentation of seafood-food based bread toppings would be inappropriate.

(65) Similarly, the Parties have provided market data for taramasalatas, which is the only seafood-based product on which they overlap, while arguing that these should be part of a wider market for savoury seafood-based bread toppings such as fish spreads.111

(66) In line with the Commission’s decisional practice, the Parties submit that the geographic markets for vegetable-based savoury bread toppings and taramasalatas are national in scope.112

3.2.5.3. Commission’s assessment and conclusion

(67) First, amongst savoury bread topping, the Commission investigated whether vegetables-, seafood- and meat-based savoury bread toppings should be distinguished.113 The results of the market investigation suggest that vegetables- based savoury bread toppings may be considered to be a distinct market from seafood- or meat-based savoury bread toppings.114 For example, a customer submitted: “They do not meet the same needs and consumers have different requirements depending on the products (vegetarian consumers, religious faiths, etc”.115 The majority of customers who responded to the market investigation considered that different types of vegetable-based savoury bread toppings, such as guacamole, baba ganoush, tapenade, hummus, are all substitutes in terms of customers’ preference and the occasion of the consumption.116

(68) Second, as regards vegetables-based savoury bread toppings, the Commission considered whether they could be further segmented into organic and non-organic products, on the one hand, and fresh and ambient products, on the other hand.

(69) The majority of customers who responded to the Commission’s request for information indicated that fresh and ambient savoury vegetables-based bread toppings cannot be considered substitutes because of different demand in terms of consumption occasion: “Ambient spreads are for storage, they are used as a pantry item”.117 Another customer submitted that the two products are substitutes, however it also highlighted that ambient products are most often less expensive than fresh bread toppings.118 A competitor also explained that fresh bread toppings are produced differently from ambient products (“undergo different treatments”), are generally more expensive and respond to different consumer needs.119

(70) As regards the potential segmentation into organic and non-organic vegetables-based savoury bread toppings, the market investigation results are not conclusive. While a majority of respondents to the Commission’s request for information suggested that the two types of products can be considered as alternatives, some customers and competitors indicated the contrary.120 One customer explained: “These products are still mainly considered as alternatives but are becoming more and more different with the development of new ways of consumption (vegetarian consumers, religious faiths, etc.)”.121

(71) In light of the above considerations and taking account of the results of the market investigation, and given that the concentration would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market even under the narrowest plausible product market definition, the Commission will leave open the question whether savoury vegetables-based bread toppings belong to a separate market. Similarly, the Commission leaves the question open whether it would be justified to distinguish between organic and non-organic vegetables-based bread toppings, on the one hand, and fresh and ambient, on the other.

(72) Third, in relation to the seafood-based savoury bread toppings, the results of the market investigation are not conclusive. Several customers considered that a specific product taramasalata is not an alternative to other seafood- or vegetables-based savoury bread spreadable products.122 However, as one of these customers explained: “We consider that products of vegetable origin, regardless of the vegetable, are alternatives”.123 Other customer explained that as long as the products are seafood-based they can be considered substitutes “when it regards fish- based products”124, while another customer even indicated that taramasalata, other seafood- and vegetables-based products belong to the same group of products because they serve the same need in terms of consumption occasion of the same consumption.125

(73) In light of the above, the Commission will assess the likely effects of the concentration in relation to a putative market for taramasalatas, which would be the narrowest plausible market definition, rather than on the broader market for savoury bread toppings or seafood-based bread toppings. However, for the purpose of this case, the exact product market definition can be left open as this would not change the outcome of the competitive assessment.

(74) As regards the geographic market definition, the results of the market investigation in the present case suggest that the markets for vegetables-based savoury bread toppings and taramasalatas are national in scope.126

3.2.6. Consumable olives

(75) Consumable olives refer to the olives that can be consumed as an appetiser or used in cooking, but that cannot be used for the production of olive oil. These olives comprise different species and origins and may be stoned or destoned.

(76) Both Wessanen and PAI Partners sell pre-packaged consumable olives in the retail channel. PAI Partners sells fresh private label and branded pre-packaged olives through a number of Labeyrie Group brands, including Père Olive and King Cuisine, which are mainly sold to the conventional retail channel. Wessanen only sells ambient branded olives packaged in cans and glass containers, through its brands Bonneterre and Merza, which are exclusively sold to health food stores.127 The Parties’ activities, which give rise to a potentially affected market, overlap in the supply of pre-packaged consumable olives in France.128

3.2.6.1. Commission’s precedents

(77) The Commission has not assessed in the past a market for consumable olives.

3.2.6.2. The Parties’ view

(78) The Parties consider that the relevant product market comprises the sale of consumable olives in the retail channel, which is distinct from olives intended for the food services channel or the production of olive oil.129 They submit that it is not appropriate to retain any further segmentation based on the olives’ species, colour, taste, use or whether they are stoned or destoned.130 The Parties do not exclude that pre-packaged consumable olives (i.e. sold in plastic or glass containers) may compete and be substitutable with olives sold in bulk packaging in fresh counters of retail stores.131

(79) The Parties propose to leave the exact market definition open and have provided market data for a narrower potential segment for pre-packaged consumable olives.132 As regards its geographic dimension, the Parties submit that consumable olives are at least national in scope but potentially broader, given in particular that the level of perishability of consumable olives is lower than other fresh products.133

3.2.6.3. Commission’s assessment and conclusion

(80) A majority of market participants who responded to the market investigation indicated that pre-packed consumable olives are considered as distinct from other savoury food products such as savoury bread toppings and bite-size savoury food products.134 Moreover, while two competitors indicated that pre-packaged consumable olives and consumable olives sold in bulk packaging for sale in fresh counters are distinct products, customers unanimously indicated they both types are interchangeable.135 While competitors’ views were mixed, a majority of customers indicated that different types of olives based on varieties, colours, tastes or stoned vs destoned are substitutable.136 While two competitors indicated that fresh and ambient pre-packaged consumable olives are distinct, a majority of customers considered them as substitutable.137

(81) As regards the geographic market definition, a vast majority of customers who responded to the market investigation indicated that the market for consumable olives is national in scope.138

(82) In light of the above considerations and taking account of the results of the market investigation, and given that the concentration would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market even under the narrowest product market definition, the Commission will leave open the question whether consumable olives belong to a separate market, whether it includes consumable olives sold in bulk packaging for sale in fresh counters and whether the distinction between organic and non-organic, fresh and ambient would be justified

3.2.7. Bite-size savoury food products

3.2.7.1. Commission’s precedents

(83) Both PAI Partners and Wessanen sell bite-size savoury food. PAI Partners – through its brands Blini, L’Atelier Blini and Père Olive – sells mixed anti-pasti, stuffed peppers, involtini, chilled falafel bites, accras, böreks, samosas and rikakats, keftedes and cheese bites. Wessanen sells through its brand Bjorg ambient falafel bites, vegetable bouchées, peppers, roasted and marinated bell peppers and sundried tomatoes. The Parties’ activities, which give rise to a potentially affected market, overlap in the supply of bite-size savoury food products in France.139

(84) The Commission has not assessed in the past a market specifically concerning the bite-size savoury food products sold by the Parties.

(85) However, the Commission has previously considered a market for savoury snacks that includes chips/crisps, extruded and corn-based products, nuts, salty biscuits and other salty snacks.140 In that precedent, the Commission found strong indications that the relevant product market was at least as wide as all nut snacks and some indications that it may be as wide as all savoury snacks and left open the exact product market definition.141

(86) As regards the geographic dimension, the Commission previously considered that the market for savoury snacks could be national in scope, but ultimately left the exact geographic definition open.142 The Commission took into account differences in price and in taste’s preferences, and the fact that the snack foods business is organised, operates, and is directed at a national level.

3.2.7.2. The Parties’ view

(87) The Parties consider that no sub-segmentation should be made between different bite-size savoury snacks.143 In this regard, the Parties submit that this market is heterogeneous and characterised by a wide variety of food products (for instance, falafel bites, kefta, involtini, stuffed peppers or other snacks) that can serve the same consumption occasions.144

3.2.7.3. Commission’s assessment and conclusion

(88) A majority of the market participants who responded to the market investigation indicated that bite-size savoury food products represent a product market separate from other food products, where the following products are considered as mutually substitutable: falafel bites, accras, keftedes, böreks, samosas, rikakats, arancini, sundried tomatoes, cheese bites, fish balls, bahajis, pakoras, cocktail sausages, mini burgers, cheese balls, vegetable bouchées, mini quiches.145

(89) Moreover, a majority of these customers also considered that organic and non- organic, as well as fresh and ambient bite-size savoury food products are substitutable.146 Competitors, on the other hand, mainly indicated that these categories lead to different products responding to different needs.147

(90) As regards the geographic market definition, a vast majority of customers who responded to the market investigation indicated that the market for bite-size savoury snacks is national in scope.148

(91) In light of the above considerations and taking account of the results of the market investigation, and given that the concentration would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market even under the narrowest plausible product market definition, the Commission will leave open the question whether bite-size savoury food products belong to a separate market. Similarly, the Commission leaves the question open whether it would be justified to distinguish between organic and non-organic bite-size savoury food products, on the one hand, and chilled and ambient, on the other.

3.2.8. Bread substitutes

(92) Bread substitutes include a variety of differentiated products, such as extruded bread, crisp rolls, bread sticks, crackers and rusks. Wessanen, through brands Bjorg, Bonneterre, and Krisproll149, supplies bread substitutes such as rice waffles, breadsticks, toasted bread, and crackers to conventional retail stores and health food stores. PAI Partners, through Labeyrie Group, and its brands Labeyrie and L’atelier Blini, supplies breadsticks, crackers and toasts, grissini. However, the main product in this category supplied by PAI Partners is blini.150 In relation to bread substitutes, the Parties’ activities give rise to a potentially affected market in France.151

3.2.8.1. Commission’s precedents

(93) The Commission has previously considered the market for bakery products and its further segmentations in (i) fresh bread, (ii) industrial and pre-packaged bread, (iii) bread substitutes, (iv) cakes, and (v) morning goods.152 The Commission considered that these products, including bread substitutes, may constitute separate product markets, but ultimately left the market definition open.153

(94) As regards bread substitutes, the Commission considered that this market could be further subdivided into as many markets as product types belonging to this category. In particular, the Commission considered a separate product market for crisp bread, but ultimately left the market definition open.154

(95) The Commission has previously noted that industrial bakery sector has different distribution structures depending whether customers are active in the retail sector or in the food service sector (hotels, restaurants, fast-food outlets, sandwich shops, canteens hospitals, schools, etc.). The Commission ultimately left open the exact product market definition.155

(96) In previous cases, the Commission has considered that the relevant geographic market for bakery products was national in scope.156

3.2.8.2. The Parties’ view

(97) The Parties submit that there is one single relevant market for bakery products, which can be further segmented into the markets for (i) fresh bread; (ii) bread substitutes; and (iii) bake-off products.157

(98) The Parties suggest that blini could be included in the category of bread substitutes because they serve a similar purpose to crackers, toaster or other appetitive bread substitutes.158 As regards crepes, the Parties note that although crepes and blinis may appear to have similar characteristics, they differ in terms of ingredients, texture, size, taste and the serving/consumption occasions.159 As regards plausible market segmentation by product type, the Parties submit that toasts and crackers should be considered together.160

(99) The Parties agree that for bakery products geographic market is national in scope.161

3.2.8.3. Commission’s assessment and conclusion

(100) The Commission does not have evidence to depart from its previous precedents. Therefore, for the purposes of this case, the Commission will consider the market for the sale of bread substitutes to the retail channel162 in France, as well as plausible segment by specific product group, such as galettes, toasts and crackers.

(101) However, the exact market definition can be left open as the notified Transaction would not raise doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible market definition.163

3.3.Supply of beverages

(102) The Transaction gives rise to a vertical link between Refresco’s upstream activities in the production and bottling of non-alcoholic beverages (“NABs”) and Wessanen’s downstream sales of different types of NABs.164

3.3.1. Upstream production and bottling of NABs

3.3.1.1. Commission’s precedents

(103) The production and bottling of NABs for either private label or branded products comprises the making and packaging of a drink for a retailer or brand owner.

(104) The Commission has previously considered that the production and bottling of carbonated soft drinks (“CSDs”) and non-carbonated soft drinks (“NCSDs”) constitute two separate product markets.165 The Commission has not addressed in the past further potential segmentations within CSDs.

(105) Within NCSDs, the Commission has considered that water and ready-to-drink (“RTD”) teas belong to separate product markets.166 The Commission has considered further potential segmentations within NCSDs (namely fruit juices, energy and sport drinks), but ultimately left this question open.167 Moreover, the Commission has distinguished in the past separate product markets according to (i) the type of packaging (between carton and aseptic PET); and (ii) the production process (between aseptic and non-aseptic, as well as between ambient and chilled). The Commission considered that it is not relevant to different between sizes of packaging.168

(106) The Commission has previously considered that the production and bottling of private label NCSDs for retailers and the contract manufacturing of branded NCSDs for brand-owners belong to separate product markets.169

(107) As regards the geographic dimension, the Commission previously considered that the bottling of NCSDs is national in scope, with imports exerting a competitive constraint.170

3.3.1.2. The Parties’ view

(108) The Parties propose a number of deviations from the Commission’s previous practice. First, the Parties argue that it is not appropriate to segment the market into NCSDs and CSDs.171 Second, the Parties submit that it is not appropriate to distinguish between the bottling of organic and non-organic NABs.172 Third, the Parties argue that a distinction between chilled and ambient drinks – which was retained by the Commission in the past when assessing NCSDs – is not relevant for CSDs.173 Fourth, the Parties argue that it is not appropriate to distinguish between private label bottling and contract manufacturing bottling.174 A competitor of the Parties has largely supported these views.175

(109) The Parties submit that the geographic market for the upstream production and bottling of NABs is broader than national in scope, and at least EEA-wide.176

3.3.1.3. Commission’s assessment and conclusion

(110) In addition to the potential market segmentations considered in previous cases, the Commission inquired in the present case whether a segmentation between the production and bottling of organic and non-organic NABs is appropriate. The Parties have contested this view and argued that bottlers can use the same production line for the bottling of organic and non-organic drinks without considerable investments, costs or interruptions of their production processes.177 A competitor of the Parties has supported this view in pre-notification.178

(111) Responses to the market investigation were mixed as to whether most companies active in the production and bottling of beverages are able to and actively supply organic NABs.179 While a customer expressed that it “is aware of producers/bottlers that offer both organic and non-organic [NABs] as part of their product portfolio”, another customer noted that, in their opinion, “producers of private label products are not able to accommodate for both production of organic and non-organic products”.180 A large number of market participants indicated that the main difference between the production and bottling of organic and non-organic NABs relates to the fact that the manufacturers are required to obtain a specific certification for organic production.181

(112) In relation to private label and contract manufacturing of NABs, a majority of competitors indicated that suppliers active exclusively in the bottling of private label NABs to retailers are able to start contract manufacturing for brand owners swiftly and without significant costs.182 The opposite is also true according to these competitors: suppliers active exclusively in the contract manufacturing of NABs are able to start contract manufacturing private labels for brand owners swiftly and without significant costs.183

(113) The market investigation suggests that the market for the production and bottling of NABs is national in scope. A majority of competitors responding to the market investigation indicated that brand owners’ tenders for the procurement of NABs are mostly national and that, when they participate in these, they mainly sell the product in the same country as the plant where they manufacture it.184 Moreover, a majority of competitors also indicated that prices differ significantly among EEA countries for contract manufacturing of branded NABs and that transport costs represent a significant part of the final price of the NABs they contract manufacture.185

(114) For the purposes of this case, the precise product market definition can be left open as even under the narrowest possible market definition for the production and bottling of NABs no serious concerns arise as to the compatibility of the concentration with the internal market as regards the vertical relationship between the upstream production and bottling of NABs and the downstream sale of NABs.

(115) Moreover, it can be left open whether the market for the production and bottling of NABs is national in scope or broader, as even under the narrowest possible market definition no serious concerns arise as to the compatibility of the concentration with the internal market as regards the vertical relationship between the upstream production and bottling of NABs and the downstream sale of NABs.

3.3.2. Sale of NABs

3.3.2.1. Commission’s precedents

(116) The sale of NABs includes a large variety of drinks, juices, waters, teas and other non-alcoholic beverages.

(117) The Commission previously considered that CSDs and NCSDs constitute two separate product markets. Within NCSDs, the Commission considered segmentations into packaged water, fruit juices, RTD teas and energy and sports drinks, but ultimately left the segmentation open.186 Regarding fruit juices, the Commission considered that orange juice is a separate product market from other fruit juices187 and – while it ultimately left this question open – that orange juice could be segmented into not-from-concentrate (“NFC”) orange juice and from- concentrate (“FC”) orange juice.188 Within CSDs, the Commission previously established a distinction between cola-flavoured and non-cola-flavoured CSDs.189 Moreover, the Commission considered, but ultimately left open, further segmentations between the sale of private label and branded products and between the on-trade and off-trade channels.190

(118) As regards the geographic dimension of the relevant market, the Commission previously considered that the relevant geographic markets for NABs were national in scope.191 The Commission took into account differences in consumption patterns, logistics and distribution networks, as well as marketing strategies.

3.3.2.2. The Parties’ view

(119) The Parties consider, contrary to the Commission’s previous practice, that all NABs constitute a single product market with no further segmentations.192

(120) In line with the Commission’s decisional practice, the Parties submit that the geographic market for the sale of NABs is national in scope.193

3.3.2.3. Commission’s assessment and conclusion

(121) As explained in recital (110) above, in addition to the potential market segmentations considered in previous cases, the Commission inquired in the present case whether a segmentation between organic and non-organic NABs is appropriate. In this regard, a majority of customers responding to the market investigation indicated that organic and non-organic NABs are significantly different in terms of demand, prices or brands from the perspective of their customers.194

(122) For the purposes of this case, the precise market definition can be left open as even under the narrowest possible market definition for the sale of NABs no serious concerns arise as to the compatibility of the concentration with the internal market as regards the vertical relationship between the upstream production and bottling of NABs and the downstream sale of NABs.

4. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

4.1.Legal framework

(123) Article 2 of the Merger Regulation requires the Commission to examine whether notified concentrations are compatible with the internal market, by assessing whether they would significantly impede effective competition in the internal market or in a substantial part of it.

(124) The Commission Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Merger Regulation (the "Horizontal Merger Guidelines") distinguish two main ways in which mergers between actual or potential competitors on the same relevant market may significantly impede effective competition, namely non-coordinated effects and coordinated effects.195

(125) Non-coordinated effects may significantly impede effective competition by eliminating the competitive constraint imposed by one merging party on the other, as a result of which the merged entity would have increased market power without resorting to coordinated behaviour. According to recital (25) of the preamble of the Merger Regulation, a significant impediment to effective competition can result from the anticompetitive effects of a concentration even if the merged entity would not have a dominant position on the market concerned. In this regard, the Horizontal Merger Guidelines consider not only the direct loss of competition between the merging firms, but also the reduction in competitive pressure on non-merging firms in the same market that could be brought about by the merger.196

(126) Indeed, the Horizontal Merger Guidelines list a number of factors which may influence whether or not significant non-coordinated effects are likely to result from a merger, such as the large market shares of the merging firms, the fact that the merging firms are close competitors, the limited possibilities for customers to switch suppliers, or the fact that the merger would eliminate an important competitive force. Not all of these factors need to be present for significant non-coordinated effects to be likely. The list of factors, each of which is not necessarily decisive in its own right, is also not an exhaustive list.197

(127) In addition, the Commission Guidelines on the assessment of non-horizontal mergers under the Merger Regulation (the "Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines") distinguish between two main ways in which vertical mergers may significantly impede effective competition, namely input foreclosure and customer foreclosure.198

(128) For a transaction to raise input foreclosure competition concerns, the merged entity must have a significant degree of market power upstream.199 In assessing the likelihood of an anticompetitive input foreclosure strategy, the Commission has to examine whether (i) the merged entity would have the ability to substantially foreclose access to inputs; (ii) whether it would have the incentive to do so; and (iii) whether a foreclosure strategy would have a significant detrimental effect on competition downstream.200

(129) For a transaction to raise customer foreclosure competition concerns, the merged entity must be an important customer with a significant degree of market power in the downstream market.201 In assessing the likelihood of an anticompetitive customer foreclosure strategy, the Commission has to examine whether (i) the merged entity would have the ability to foreclose access to downstream markets by reducing its purchases from upstream rivals; (ii) whether it would have the incentive to do so; and (iii) whether a foreclosure strategy would have a significant detrimental effect on consumers in the downstream market.202

4.2.Horizontal non-coordinated effects

(130) Based on the market share data submitted by the Parties, the Transaction would give rise to the following relevant horizontally affected markets in France: secondary processed smoked salmon (Section 4.2.2), secondary processed herring (Section 4.2.3), secondary processed mackerel (Section 4.2.4), pre-packaged consumable olives (Section 4.2.5), savoury bread toppings (vegetables- and seafood based) (Section 4.2.5), bite-size savoury snacks (Section 4.2.9) and bread substitutes (Section 4.2.10).

4.2.1. Overview of market shares in the affected product markets in France

(131) Table 1 below shows the market shares of the Parties and their main competitors in all affected product markets (or segments) in France.

Table 1 – Value market shares in 2018 in France

Product | PAI Partners | Wessanen | Combined | Main competitor203 |

| Branded: [20-30]% |

|

|

|

Smoked salmon | Private label: [5- 10]% | [0-5]% | [30-40[% | Delpeyrat: [5-10]% Private labels: [50-60]%204 |

| Total: [30-40]% |

|

|

|

| Branded: [20-30]% |

|

|

|

Secondary processed herring | Private label: [30- 40]% | [0-5]% | [60-70]% | Baltic: [0-5]% Private labels: [40-50]%205 |

| Total: [60-70]% |

|

|

|

| Branded: [30-40]% |

|

|

|

Secondary processed mackerel | Private label: [10- 20]% | [0-5]% | [40-50]% | Nordland: [10-20]% Private labels: [10-20]%206 |

| Total: [40-50]% |

|

|

|

| Branded: [50-60]% |

|

|

|

Savoury vegetable bread toppings | Private label: [20- 30]% | [0-5]% | [70-80]% | Cruscana: [0-5]% Private labels: [30-40]%207 |

| Total: [70-80]% |

|

|

|

Taramasalata | Branded and private label: [70-80]% | [0-5]% | [70-80]% | N/A |

| Branded: [10-20]% |

|

|

|

Pre-packaged consumable olives | Private label: : [10- 20]% | [0-5]% | [20-30]% | Croc’Frais: [40-50]% Private labels: [10-20]%208 |

| Total: [20-30]% |

|

|

|

Bite-size savoury snacks | Branded and private label: [20-30]% |

[0-5]% |

[30-40]% |

N/A |

Bread substitutes (branded only) |

[5-10]% |

[10-20]% |

[20-30]% | Mondelez: [30-40]%209 |

Source: Form CO, Annex 23 (revised 21 August 2019) and Parties’ response to RFI 10

(132) As regards the potentially relevant markets for smoked salmon, secondary processed herring, secondary processed mackerel, fresh savoury vegetables-based bread toppings, taramasalata and olives, the Parties submit that Wessanen’s market shares are overestimated because of the methodology applied for calculation of the total market size.210 The Parties explain that for this purpose they used the IRI211 estimates, which are based on sales to consumers at the retail level, include the retail margin and value added tax (VAT)..212 Notably, the IRI estimates include only the sales to conventional retail stores (hyper- and supermarkets, including proxy stores) and exclude sales to health food stores.213 While Wessanen supplies above specified products exclusively to health food stores, the total market size provided by the IRI estimates does not reflect this (i.e. the sales by competitors in health food stores are not reflected in the total market size). The Parties also submit that Wessanen’s sales provided for each of the product markets considered include sales of all relevant brands to all retail sales channels based on net invoice data.214

(133) This means that the total market size including both conventional and health food stores is larger than the market size reported in the IRI estimates. Given that for each relevant product category Wessanen’s market shares have been estimated by taking into account all its sales at net invoice level and adding a comparable retail margin and the VAT215 and the fact that PAI Partners do not have sales into HFS, consequently, the Parties combined market shares are overestimated. As considered in recital (29), the internal documents of the Parties estimate that, overall, [40-50]% of organic food sales are made in conventional retail stores and [30-40]% in the health food stores. However, these proportions are likely to vary from product to product, and the Parties have been unable to estimate in a reliable manner the total size of organic food sales to HFS on a product basis.216 Therefore, only sales to conventional retail stores, where the IRI estimates are more precise, were considered to calculate the total market size, with the result that the market shares of Wessanen are overestimated. As it has not been possible to obtain figures that are more precise during the market investigation, the Commission will base its assessment on the figures in Table 1, noting however that they correspond to a worst-case scenario.

4.2.2. Smoked salmon

(134) Based on the market share data submitted by the Parties217, the combined market shares of the Parties in value terms in 2018 were [30-40]% (PAI Partners: [30-40]%; Wessanen: [0-5]%). Other suppliers of smoked salmon in France are Delpeyrat with a share in value terms of [5-10]%, Kritsen with a share of [0-5]% and Petit Navire with a share of [0-5]%. If only the segment of branded smoked salmon was considered, the combined market shares of the Parties in value terms in 2018 would be [50-60]% (PAI Partners: [50-60]%; Wessanen: [0-5]%).218

(135) If potentially relevant segment for organic smoked salmon (branded and private labels included) in France in 2018 was considered, the combined market shares of the parties would be [30-40]% (PAI Partners: [30-40]%; Wessanen: [0-5]%), however the increment remains very low. Other suppliers of organic smoked salmon in conventional retail stores in France are Kritsen with a share in value terms of [5- 10]% and Delpeyrat with a market share of [0-5]%, among others, while the private label products share in the organic smoked salmon segment was [40-50]%. In addition, other suppliers active in HFS include, among others, Herens, Compagnie du saumon Guyader Gastronomie219, and Olsen.220

(136) Given that both Parties sell only branded organic smoked salmon,221 the Commission also considered that the combined market shares of the parties in 2018 in branded organic smoked salmon were [60-70]% (PAI Partners: [60-70]%, Wessanen: [0-5]%). The Commission also notes that private labels have a large share of the organic smoked salmon segment ([40-50]%) and that it cannot be excluded that private label products would exert competitive pressure on branded products, which could also have an effect on the capacity utilisation of the branded product supplier. For example, a PAI Partners’ internal document, though not specifically referring to organic smoked salmon, notes: “[…]”.222

(137) Given the negligible increment in market share (which is likely to be overestimated as explained in recital (116) above) brought by Wessanen under any plausible market segmentation, the Commission considers that the concentration will not substantially modify the market structure for smoked salmon in France.

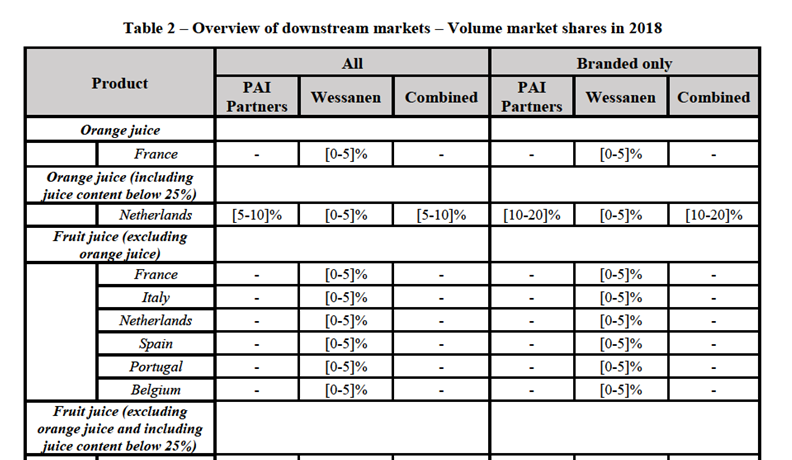

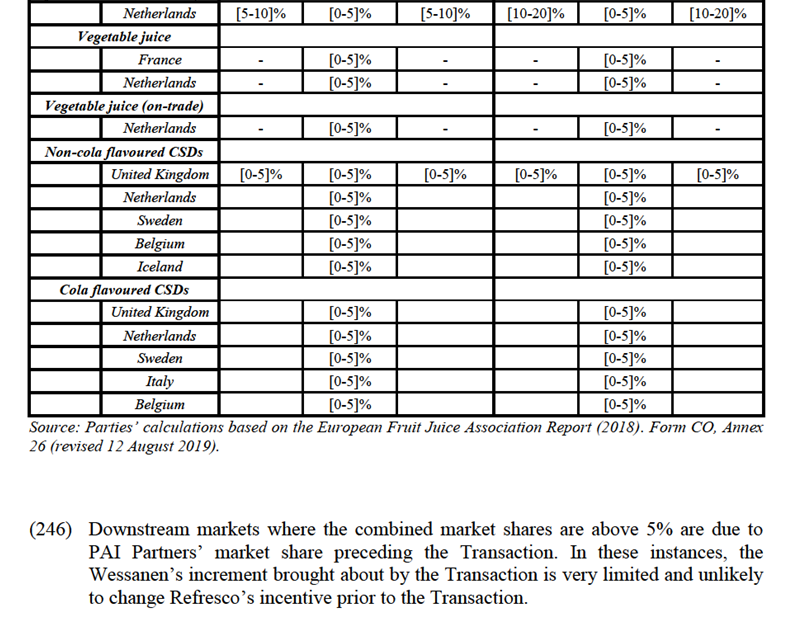

(138) Further, the Parties focus on different retail outlets for the supply of smoked salmon products, which indicates that the Parties are not the closest competitors. Wessanen does not supply the conventional retail stores223 and is only present in health food stores, whereas PAI Partners sells into conventional retail stores and is not present in health food stores.224 As mentioned in recitals (29) to (32), the different retail outlets imply that the Parties face different customers for the supply of their products and develop outlet-specific brand and pricing strategies.

(139) The results of the market investigation also indicate that the Parties are not the closest competitors. None of the customers having responded to the market investigation has identified Wessanen as the closest competitor to PAI Partners.225 When asked about the closest competitors to Wessanen, none of the customers having responded to the market investigation who operate health food stores has identified PAI Partners among competitors for organic smoked salmon.226 As regards customers operating conventional retail stores, the majority among them who responded to the market investigation claimed that they are not aware of Wessanen offering smoked salmon products in France.227

(140) Overall, during the market investigation the views on the impact of the concentration expressed by customers were mixed for each of the product markets considered.228 A majority of the customers who responded to the market investigation and expressed an opinion indicated that they do not expect the Transaction to have any effect on prices in most of the considered product markets.229 The customers mainly explained that there would be no impact because Wessanen is not present on those markets: “No impact because Wessanen is not active on this market.230 Similarly, other customers submitted: “Not the same markets, rather complementary products231 or “No change/ We are not aware about the fresh products supplied by Wessanen”.232 However, a few customers of PAI Partners submitted that the prices might increase following the Transaction across all groups of products. One of these customers explained, for example, that there are already few suppliers in France and that the Transaction will make entry by rivals more difficult.233

(141) The market investigation results discussed above in recital (140) apply to smoked salmon. Specifically, in relation to the secondary processed fish products, including the smoked salmon, one customer even suggested that prices may decrease.234

(142) The Commission considered whether absent the Transaction it would have been likely that Wessanen enters and develops its offer of smoked salmon products into the conventional retail stores or significantly expands its current activities.

(143) First, the entry into conventional stores may not be easy, as it would require significant investment in marketing and sufficient capacity to serve the conventional retail channel volumes. For example, one customer representing a conventional retail channel explained that switching suppliers for smoked salmon and organic smoked salmon would not be easy because of brand loyalty of its customers and the capacity of the supplier to provide the necessary volumes.235 While Wessanen has sales in organic smoked salmon only, it can be questioned whether it could effectively enter the conventional retail stores with a limited product range. The market shares data provided by the Parties indicate that majority of suppliers present in the overall smoked salmon market are also listed for organic smoked salmon.236 This is the case for PAI Partners, Delpeyrat and Kritsen. Notably, with the exception of PAI Partners, other competitors’ share of organic smoked salmon concerns only a small share of their total estimated sales of smoked salmon.237 Secondly, as the Parties explained, Wessanen does not consider its activities related to fish products, including smoked salmon, to be one of the core categories, […].238 Thirdly, the respondents to the market investigation also suggested that it was not likely that Wessanen would enter conventional retail stores.239 In the light of the above, the Commission considers that the entry or expansion of Wessanen in relation to supply of smoked salmon products in France is thus not likely.

(144) Based on the above considerations and in the light of the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers that the concentration would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market as regards the Parties’ activities in France in the putative market for the supply of smoked salmon.

4.2.3.Secondary processed herring

(145) PAI Partners supply marinated and smoked herring sold in the daily fresh department of the conventional retail stores (fresh chilled products as opposed to canned products).240 Wessanen through its brand Bonneterre sells only branded smoked herring in the daily fresh department of health food stores.241

(146) Further to the considerations in recitals (132) to (133), the Commission considers the Parties’ submitted market share data for secondary processed herring which includes branded and private label marinated and smoked herring sold in daily fresh department (chilled as opposed to canned herring or herring packaged in glass containers) of the retail stores. Based on this data, the combined market shares of the Parties in value terms in 2018 is [60-70]% (PAI Partners: [60-70]%; Wessanen: [0- 5]%). Other suppliers of secondary processed herring in France are Baltic with a share in value terms of [0-5]%, La Mere Angot with a share of [0-5]%, Est Friture with a share of [0-5]%, among others, while the share of private label products is [40-50]%.242 If only the segment of branded secondary processed chilled herring was considered, the combined market share of the Parties in value terms in 2018 would be [50-60]% (PAI Partners: [50-60]%; Wessanen: [0-5]%). Specifically for the HFS, the following companies, among others, are active in the supply of secondary processed herring: Herens, Olsen, and La Sablaise.243

(147) If potentially relevant segment of branded chilled smoked herring in France was considered, the combined market shares of the parties would be slightly higher – [70-80]% (PAI Partners: [70-80]%; Wessanen: [0-5]%), however the increment remains very low.244 There are significant competitors providing branded smoked herring in France, for example Mere Angot and JC David.245

(148) The Commission considers that given the negligible increment of below 1% (which is likely overestimated as explained in recitals (132) to (133) in market share brought by Wessanen, including under the narrowest plausible market segmentation, the Transaction will not substantially modify the market structure for secondary processed herring in France.

(149) Furthermore, the Commission considers that the Parties are not the closest competitors. First, the Parties serve different retail outlets and thus supply different customers with differentiated brands and develop outlet specific marketing strategies. As mentioned in recital (145), PAI Partners sells secondary processed herring only in the conventional retail stores and Wessanen only in HFS.

(150) Second, the Parties explained that their secondary processed herring products could be further differentiated in relation to price.246 The secondary processed herring products sold by PAI Partners, through its brand Delpierre, have a mid-range price position in the conventional retail stores, and generally have a lower price position than Wessanen’s products.247 Since pelagic fish such as herring is not farmed, the distinction between organic and non-organic is not relevant as it is for smoked salmon.248 Pelagic fish products may still carry the label for sustainable fishery.249 While it appears that secondary processed herring products of both Parties carry that label250, Wessanen’s products still have a premium price position because it is distributed through health food stores.251

(151) The Parties also provided information on private label products. It appears that the difference in price between private label products and branded products of PAI Partners is smaller than between the branded products of the Parties. The Commission considers that it further indicates the differentiation between the Parties offering and the different competitive dynamic in conventional retail stores compared to HFS.

(152) Third, the range of the Parties’ portfolios of smoked herring is also different. While Wessanen has only one product of smoked herring,252 the PAI Partners’ portfolio in this category is larger and includes several types of smoked herring.

(153) In line with the assessment in recitals (149) to (152), the results of the market investigation suggest that the Parties are not the closest competitors. None of the customers having responded to the market investigation has identified Wessanen as closest competitor to PAI Partners nor mentioned Wessanen as their potential supplier for secondary processed herring.253 In addition, several respondents to the Commission’s market investigation representing conventional retail outlets submitted not to be aware that Wessanen carries these products.254

(154) The Commission also considered whether absent the Transaction it would have been likely that Wessanen enters and develops its offer into the conventional retail stores. Similarly, as analysed in the recital (143) in relation to smoked salmon, the entry into conventional stores for secondary processed herring may not be easy, as it would require sufficient capacity to serve the conventional retail channel volumes. For example, the customer representing a conventional retail channel explained that switching suppliers for secondary processed herring, as for smoked salmon, would not be easy because of brand loyalty of its customers and the capacity of the supplier to provide the necessary volumes.255 Wessanen has only limited sales of secondary processed herring256 and), given that sales in the HFS generate higher revenues because of higher prices, suppliers active only in HFS would unlikely have an incentive to switch to conventional retail stores. As regards Wessanen’s expansion plans, the Parties explained that Wessanen does not consider its activities related to fish products, including secondary processed herring, to be one of the core categories, and, as its internal documents suggest, […].257

(155) The respondents to the market investigation also suggested that Wessanen’s entry into conventional retail stores is not likely.258 In light of the above considerations, the Commission considers that the entry or expansion of Wessanen in relation to supply of secondary processed herring products in France is thus not likely.

(156) The market investigation results discussed above in recital (140) apply to secondary processed herring. Specifically, in relation to the secondary processed fish products, including the secondary processed herring, one customer even suggested that prices may decrease.259 There were no further substantiated concerns emerging during the market investigation with regard to the supply of secondary processed herring in France.

(157) Based on the above considerations and in the light of the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers that the concentration would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market as regards the Parties’ activities in France in the putative market for the supply of secondary processed herring.

4.2.4.Secondary processed mackerel

(158) In France, PAI Partners supply branded (and to a very limited extent – private label) smoked mackerel in the daily fresh department of the retail store (fresh products as opposed to canned products).260 Wessanen sells only branded smoked mackerel in the daily fresh department of health food stores.261

(159) Further to the considerations in recitals (132) to (133), the Commission considers the market share data submitted by the Parties for secondary processed mackerel which includes branded and private label smoked mackerel sold in the fresh daily department (chilled as opposed to canned mackerel or mackerel packaged in glass containers). Based on this data, the Parties’ combined market share in terms of value in 2018 are [40-50]% (PAI Partners: [40-50]%; Wessanen: [0-5]%). Other suppliers of smoked mackerel sold in the fresh daily department in France are Nordland with a share in value terms of [10-20]%, Pecheur d’Islande [5-10]%, No brand [0-5]%, among others.262 If only the segment of branded smoked mackerel was considered, the combined market shares of the Parties in value terms in 2018 would be [40-50]% (PAI Partners: [30-40]%; Wessanen: [0-5]%).263 Specifically for the HFS, the following companies, among others, are active in the supply of secondary processed mackerel: Herens, Olsen, and Safa.264

(160) Given the low increment in market share (which is likely to be overestimated as explained in recital (132) brought by Wessanen, the Transaction will not substantially modify the market structure for secondary processed mackerel in France.

(161) Furthermore, the Commission considers that the Parties are not the closest competitors. First, the Parties serve different retail outlets and thus supply different customers with differentiated brands and develop outlet specific marketing strategies. As mentioned in recital (158), PAI Partners sells smoked mackerel only in the conventional retail stores and Wessanen only in HFS.

(162) Second, the Parties explained that secondary processed mackerel products could be differentiated in relation to price.265 Smoked mackerel sold by PAI Partners, through its brand Delpierre, have a mid-range price position in the market, and have a lower pricing position as Wessanen’s products.266 Since pelagic fish such as mackerel is not farmed, the distinction between organic and non-organic is not relevant as it is for smoked salmon. However, Wessanen’s products still have a premium price position because it has a more sustainable brand image267 and is sold in HFS.