Commission, July 30, 2018, No M.8829

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

TOTAL PRODUCE / DOLE FOOD COMPANY

Subject: Case M.8829 – Total Produce/Dole Food Company

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) in conjunction with Article 6(2) of Council Regulation No 139/2004 (1)

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 11 June 2018, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation, by which Total Produce PLC ("Total Produce") will acquire, within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) and 3(4) of the Merger Regulation, joint control over DFC Holdings LLC, and thus indirectly over its wholly-owned subsidiary, Dole Food Company, Inc. (together referred to as "Dole") together with its current sole owner, Mr. David H. Murdock by way of purchase of shares (the "Transaction") (2). Total Produce and Dole are referred to as the "Parties".

1. THE PARTIES

(2) Total Produce is a leading fresh produce distributor, with approximately 70% of its annual turnover being generated in Europe. Total Produce also operates banana ripening centres which are mainly used for its own ripening needs but occasionally for banana ripening services to third parties. Total Produce was formed in 2006 following a separation of the general produce and distribution arm of Fyffes Plc ("Fyffes"). It is now an independent and separately quoted company with no residual shareholding relationship with Fyffes.

(3) Mr. David H. Murdock is currently the ultimate sole owner of Dole through The David H. Murdock Living Trust. DFC Holdings LLC (and therefore ultimately Dole Food Company, Inc.) is held by The David H. Murdock Living Trust, of which Mr. David H. Murdock is the trustee and the ultimate beneficiary. In addition to Dole, Mr. David H. Murdock also holds controlling interests in businesses primarily involved in real estate development and ownership, transport equipment leasing, building materials manufacturing, aviation services, as well as mortgage, hotel, and oil and gas operations.

(4) Dole is a producer, marketer and distributor of fresh fruit and vegetables, operating in many locations worldwide but with a principal geographic focus on North America. In 2016, Europe represented only 24% of Dole's worldwide turnover.

2. THE OPERATION AND CONCENTRATION

(5) Pursuant to a binding Securities Purchase Agreement ("SPA") signed on 1 February 2018, Total Produce intends to acquire a 45% shareholding in DFC Holdings LLC, and thus indirectly in its wholly-owned subsidiary, Dole Food Company, Inc. from the current sole owner, Mr. David H. Murdock via The David H. Murdock Living Trust. Total Produce will also obtain the right to nominate half of the members of the board and acquire veto rights over the key strategic and commercial decisions of Dole. This transaction is valued at USD 300 million in cash.

(6) As a result of the Transaction, Total Produce will obtain joint control over Dole together with Mr. Murdock.

(7) Dole will be a joint venture performing on a lasting basis all the functions of an autonomous economic entity. First, Dole already has and will continue to have significant capital to fund its operations as well as the staff and a dedicated management team necessary to operate independently of its shareholders. Second, Dole will continue to have access to and presence on the market, where it will continue to service its customers. Third, Dole is intended to operate on a lasting basis, with plans to expand its business in the years ahead.

(8) The Transaction therefore constitutes a concentration pursuant to Article 3(1)(b) and Article 3(4) of the Merger Regulation.

3. EU DIMENSION

(9) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (3). Each Total Produce and Dole have an EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Total Produce EUR […] million in 2017, Dole EUR […] million in 2017), but each does not achieve more than two-thirds of its aggregate EU-wide turnover within one and the same Member State. The notified operation therefore has an EU dimension pursuant to Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. APPLICABILITY OF THE EEA AGREEMENT

(10) Fresh produce falls outside the scope of the Agreement on the European Economic Area ("EEA Agreement") pursuant to Article 8(3)(a) of the EEA Agreement. The assessment of the impact of the Transaction in the EFTA States hence falls outside the jurisdiction of the Commission. (4)

5. BANANAS

(11) The Parties' activities in the EU overlap in bananas (assessed in Section 5), bagged salad (assessed in Section 6), pineapples (assessed in Section 7) and other fruit and vegetables (assessed in Section 8).

(12) Dole is a vertically integrated business for bananas; it owns farmland in Central and South America and South Africa, manufacturing plants, pack houses and grows its own bananas, and also purchases them from third parties. It also has its own refrigerated ships, containers and port facilities, and operates a limited number of banana ripening centres.

(13) Total Produce is a wholesale distribution business with only limited assets at other levels of the supply chain. In contrast to Dole, which is focused on a more limited range of products (with bananas and pineapples accounting for 43% and 8% of Dole’s worldwide sales), Total Produce deals in a broad portfolio of products across both vegetables and fruits, with bananas accounting for just 10% of its worldwide sales.

5.1. The import and supply of bananas

(14) The majority of bananas marketed in the EU are imported, with approximately 70% coming from Central and South America (so-called 'dollar' bananas) and approximately 20% coming from a variety of African, Caribbean and Pacific countries (so-called 'ACP bananas'), although there is some production within the EU (the remainder). (5)

(15) Bananas grown on farms are harvested green at the appropriate maturity, and packaged on or near the farm where it is grown. Once quality inspections have been passed, these bananas are prepared for transportation to the EU. Bananas must be stored at low temperatures of around 14°C, and for this reason, specialised refrigerated cargo ships (or 'conventional reefers') or refrigerated containers on general container shipping lines, may be used. (6)

(16) Once in the EU, green bananas must be ripened in temperature-controlled ripening chambers for 4 – 6 days, which may be owned by either the importer, the retailer, or a third party provider. Finally, these bananas, now yellow, may travel much shorter distances and must arrive at customer distribution centres for sale to retailers, wholesalers or the food service sector. (7)

5.1.1. Relevant product market

5.1.1.1. Distinction between bananas and other fresh produce Parties' arguments

(17) The Parties submit that bananas form part of the whole market for fresh fruit and produce, on the basis that (i) there are considerable similarities between the supply chains for bananas and other fresh fruit, especially given that bananas no longer need to be shipped on dedicated refrigerator ships, and (ii) banana suppliers also supply other fruit. Nevertheless, the Parties also acknowledge that the import and supply of bananas has consistently been analysed separately by the Commission in the past.

Previous decisional practice

(18) In the Commission's most recent precedent, in merger case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission chose to define the market for bananas as distinct from the market for fresh fruit, from the perspective of both competitors and customers. (8)

(19) The Commission's market investigation in case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes found a number of specificities associated with bananas on the supply-side. In particular, the competitors noted the following specificities that distinguish the supply of bananas from the supply of other fruit: (i) a lower degree of price variability, (ii) the distance travelled from origin to destination, (iii) the use of plastic packaging, (iv) the presence of import duties, (v) the perishability and need for regular supply of bananas, (vi) the need for ripening services, (vii) the existence of yearly contracts with growers and (viii) the transport and storing in chilled conditions. (9)

(20) On the demand-side, the investigation found that customer demand for bananas was inelastic, with very limited substitutability with other fruits, and relatively constant throughout the year (whilst other fresh produce is typically seasonal). Furthermore, it was found that retailers tend to organise separate tenders for bananas and that bananas are the lowest cost fruit. (10)

Commission assessment

(21) The Commission's market investigation in the present case confirmed that the arguments outlined above are all broadly still relevant. In particular, the majority of competitors stated that there were specificities in supplying bananas as opposed to supplying other fresh fruit. (11) The specificities most often cited include: (i) year-round sourcing of bananas, (ii) the need to ripen bananas prior to sale; (iii) yearly price negotiations, and (iv) special conditions for transportation. (12) Responses by customers also show that ripening is more important for bananas than for other fruit and that yearly contracts and pricing set bananas apart from other fruit. (13)

(22) On the basis of the replies received during the Commission's market investigation, the Commission considers that the definition of the bananas market as a distinct product market from other fresh fruit should be maintained.

5.1.1.2. Distinction based on stage of ripening process: green vs. yellow bananas

(23) Bananas are generally imported green from overseas and ripened into yellow bananas by undergoing a ripening process, usually in geographic proximity of the customer. Bananas can be imported green and sold green to ripening service providers or customers with ripening facilities, or ripened by the importers themselves and sold yellow.

Parties' arguments

(24) The Parties argue that it is not necessary to define separate markets for green and yellow bananas as both suppliers and customers can readily switch between supplying and purchasing green and yellow bananas.

(25) According to the Parties, there is plenty of ripening capacity across the EU, should suppliers or customers wish to switch between green and yellow bananas. Furthermore, if required, new ripening capacity may be easily and promptly created by suppliers. The Parties refer to Total Produce budgeting a cost of around EUR […] for the construction of […] ripening rooms in a new facility in Denmark and a cost of around EUR […] for […] new rooms in Sweden. According to the Parties, retailers can also easily and promptly vertically integrate into ripening or procure ripening services from independent third parties. Finally, the Parties argue that with the increasing flexibility of ripening and trucking arrangements, bananas can be ripened in one EEA country and quickly, easily and cheaply transported across the border to other countries. (14)

Previous decisional practice

(26) In case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission did not consider it necessary to distinguish separate markets for green and yellow bananas, deeming it sufficient to look at the overall volumes of bananas sold to customers independently of their ripening stage.

Commission assessment

(27) The Commission's market investigation revealed that suppliers, wholesalers and retailers can and do purchase both green and yellow bananas. For green bananas, a variety of ripening options are available: (i) suppliers of green bananas with ripening facilities can provide ripening services for the bananas they supply; (ii) suppliers of green bananas with ripening facilities can provide ripening services for their customers' bananas (supplied by other suppliers); (iii) ripening services are provided by independent third party ripeners; and (iv) wholesalers and, to a lesser extent, retailers can operate own ripening facilities. (15)

(28) The majority of competitors who responded indicated that they own ripening facilities (16) and a number of them have indicated that they have opened new ripening facilities in the last 5 years. (17) The majority of wholesalers and retailers who responded consider that there is currently sufficient ripening capacity to meet their needs. (18) Some retailers have also indicated that ripening facility providers can and would, on request, expand their ripening capacity. (19)

(29) On the basis of the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers, for the purposes of the present Transaction, that the relevant product market for the import and supply of bananas comprises of both green and yellow bananas.

5.1.1.3. Distinction based on certification: Fairtrade, organic and conventional

(30) Bananas certified as 'Fairtrade' are those which meet certain ethical, social and environmental standards upheld by the Fairtrade Foundation. Bananas certified as 'organic' are those that meet the criteria specified in the Council Regulation (EC) No. 834/2007 on the organic production and labelling of organic products. Some bananas may bear the double label 'Fairtrade' and 'organic'. Conventional bananas are those which meet neither Fairtrade nor organic requirements.

Parties' arguments

(31) The Parties submit that a distinction should not be made between Fairtrade and organic bananas, due to the wide prevalence of double-label bananas. The Parties further contend that conventional bananas should also be treated within the same frame of reference, arguing that there is a high degree of supply-side substitutability between the categories. The Parties suggest that importers, wholesalers and retailers purchase a broad mix of all such bananas, depending on the prevailing tastes in the destination territory. (20)

(32) Furthermore, although there are certain differences in the way bananas are produced, once bananas enter the supply chain, there is no material difference in terms of packing, shipping, ripening, distributing and retailing the products. Both products are ultimately sold on the same supermarket shelves at similar price points. (21)

Previous decisional practice

(33) In case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission considered that it would be justified to define separate markets for (i) conventional bananas and (ii) organic and Fairtrade bananas. Any further distinction between organic and Fairtrade bananas was considered unnecessary as the presence of double-label bananas (both organic and Fairtrade) blurred the difference between the two. (22)

Commission assessment

(34) The large majority of competitors, retailers and wholesalers that responded to the Commission's questionnaire do not consider non-conventional (i.e. Fairtrade and organic) bananas to be substitutable with conventional bananas. (23) The market investigation indicates that customers that specify their need for Fairtrade or organic bananas would not consider substituting these for conventional bananas. Moreover, Fairtrade and organic bananas command a premium price, which on average was quoted as being around 30-40% higher than conventional bananas (and up to 100% in certain markets). (24)

(35) Overall, the market for Fairtrade and organic bananas appears to be growing, with sales of these non-conventional bananas steadily growing over the last few years. (25)

(36) As regards the substitutability of Fairtrade and organic bananas, the replies to the market investigation are less conclusive than for the substitutability of conventional and non-conventional bananas. Whilst a large number of competitors, retailers and wholesalers that responded to the Commission's questionnaire regard Fairtrade and organic bananas as not substitutable, a number of them pointed out that the majority of organic bananas are already Fairtrade certified and that as long as Fairtrade and organic bananas are priced similarly, they could be seen as substitutable. (26) Moreover, whilst some of the respondents to the Commission's questionnaire noted a price difference between Fairtrade and organic bananas, this price difference appears to be a lot more modest than the price difference between conventional and non-conventional bananas. (27)

(37) On the basis of the results of the market investigation and having regard to its previous decisional practice, the Commission considers that it is justified to define separate markets for (i) conventional bananas and (ii) Fairtrade and/or organic bananas. The Commission does not find that there are separate markets for Fairtrade and organic bananas.

5.1.1.4. Distinction based on branding

(38) Bananas may be sold unbranded or under a range of brands, including from the producer, importer or wholesaler. Private label bananas are characterised as being branded with a retailer's label rather than a supplier's label.

Parties' arguments

(39) The Parties consider that distinguishing separate markets on the basis of brand is not justified, and argue that consumer choice is driven by price and perceived quality rather than the brand. They add that retailers increasingly carry both branded and private label bananas, which is to a large extent due to the competitive pressure from discount retailers, such as Aldi and Lidl, fuelling the growth of private label bananas and therefore also constraining prices for branded bananas. The Parties consider that the price premium for branded bananas has been decreasing, currently estimated at 15%. (28)

Previous decisional practice

(40) In case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission did not consider it necessary to distinguish the market between branded and non-branded bananas.

Commission assessment

(41) The vast majority of competitors, wholesalers and retailers that responded to the Commission's questionnaires regard branded and non-branded bananas as substitutable. (29) Whilst some respondents indicated that brands are important to some customers, that some customers may be brand loyal and that certain branded bananas (e.g. Chiquita) can command a premium price, (30) others have noted that customers mostly do not distinguish between branded and non-branded bananas, that price, quality and presentation at point of sale are more important for consumers and that the price premium for branded bananas is relatively modest. (31)

(42) On the basis of the results of the investigation, and with regard to its previous decisional practice, the Commission considers that, for the purposes of the present Transaction, the relevant product market for the import and supply of bananas comprises of both branded and non-branded bananas.

5.1.1.5. Import and supply of bananas to retailers and wholesalers

(43) Importers can sell bananas either directly to retailers in the EU, mainly to the modern retail channel (supermarkets), or to wholesalers who further distribute the bananas to retailers and other customers, including to channels other than the modern retail channel (i.e. cash & carry shops, open markets, food services, institutional catering etc.).

Parties' arguments

(44) The Parties submit that the relevant product market for the import and supply of bananas should not be distinguished between supplies to retailers and wholesalers. The Parties argue that there is no material overlap between them in relation to the non-modern retail channel and suggest therefore that there is no need to decide in the present case on whether and to what extent it should form a distinct product market. (32)

Previous decisional practice

(45) In case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission defined the relevant market as the import and supply of bananas to retailers and wholesalers, having found that major wholesalers not only sell directly to the large retailers (in addition to smaller retailers and food service channel customers), but that they also directly sourced bananas and traded them with other wholesalers at European ports. (33)

Commission assessment

(46) According to the responses to the market investigation, competitors do not appear to distinguish between supplying customers along the retail or the wholesale channels. (34)

(47) Competitors do point to some specificities, as one respondent puts it: "retailers tend to prefer a vertically integrated supplier that can consistently deliver quality products throughout the year" (35) and some explain that contracts with the retail sales channel tend to be renewed on a yearly basis while wholesalers buy more on the spot market. Further, they add that small customers, such as food services, require in general more individual attention (36), whereas cash and carry outlets are less sophisticated clients with simpler portfolios. Notwithstanding these differences, respondents noted that in general there were no specific barriers to the supply bananas to the respective sales channels. (37)

(48) On the basis of the responses to the market investigation, and with regard to its decisional practice, the Commission considers that for the purposes of the assessment of the present Transaction, the relevant market for the import and supply of bananas comprises the supply to both retailers in the modern retail channel (i.e. supermarkets) and wholesalers who may sell the bananas to channels other than the modern retail channel (i.e. cash & carry shops, open markets, food services, institutional catering etc.).

5.1.1.6. Distinction based on banana origin and class of banana

(49) The Parties submit that it is not appropriate to distinguish the relevant market by origin of bananas or by class of banana. (38)

(50) In case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, distinguishing separate markets based on origin was not considered relevant (39) and in the same case, the Commission concluded that it was not appropriate to define separate relevant markets according to the class of banana. (40)

(51) In the present case, on the basis of the Commission's previous precedent, the Commission considers that the relevant product market for the import and supply of bananas should not be further distinguished according to the different classes of banana or for the different origin of the banana.

5.1.2. Relevant geographic market

5.1.2.1. Parties' arguments

(52) The Parties submit that the appropriate geographic frame of reference for the import and supply of bananas is at least regional if not EEA-wide for the reasons outlined below. In the alternative, and for the same reasons, the Parties submit that at the very least, it is important to take into account the evidence for assessing the Proposed Transaction on the basis of regional clusters (41).

(53) The Parties put forward that the market is wider than national for the following reasons: (1) bananas are sold very widely across the entire EEA, arriving at various European ports for onward supply to all parts of the EEA; (2) there is an increasing flexibility of shipping arrangements and trucking operators willing to make frequent intra-EEA deliveries of fresh produce are readily available; (3) customers active in multiple Member States coordinate their banana procurement across different territories, sometimes sourcing the entirety of their European banana requirements under single multi-territory contracts; (4) many retailers procure bananas and other fresh produce across several EEA Member States; (5) wholesalers of any reasonable size procure fruit across borders, in order to obtain supplies on the most cost-effective basis and to ensure the procurement of the full range of produce, which is unlikely to be available domestically; (6) wholesale prices move in a similar way in EEA regions as a result of strong common cost and demand factors; (7) banana ripening centres with spare capacity are widely available across all of the EEA, meaning that green bananas can be transported across borders before being ripened in the destination country. (42)

5.1.2.2. Previous decisional practice

(54) In case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission found that the market for the supply of bananas is national in scope. (43) The market investigation in that case revealed that there were a number of differences in the preferences of banana consumers among the different Member States, including as to quality, size, origin, brands, certification and packaging of bananas. (44) Moreover, it was found that: (i) the nature of customers (retailer or wholesaler) varied significantly across countries, (ii) there were considerable differences in prices among countries, despite the fact that bananas were often imported through the same ports, (iii) retailers tended to negotiate prices at a national level, (iv) competitors tended to have different pricing strategies per country, and (v) expansion or entry would not be a timely reaction to a 5-10% permanent increase in price of bananas in a given country. (45)

5.1.2.3. Commission assessment

(55) The results of the market investigation do not support the view that customers purchase bananas on a regional basis, with a vast majority of competitors, wholesalers and retailers stating that this is not the case. (46)

(56) The vast majority of competitors, wholesalers and retailers that have responded to the Commission's questionnaire observe differences in prices for bananas between various EU countries. (47) A difference in prices of bananas between various EU countries was found to exist irrespective of whether the sales in question were through the modern retail channel (supermarkets, retailers) or not (cash & carry, wholesalers, food service channel etc.). (48)

(57) Whilst many competitors and the majority of wholesalers and retailers that responded to the Commission's questionnaires stated that there were no barriers to trade flows between different EU countries for banana sales to the modern retail and wholesale channels, (49) some respondents noted that there were different requirements depending on each country or even retailer. For example, one competitor stated that Spain prefers bananas of EU origin (Canaries), Denmark prefers "small fingers per box" and Eastern Europe does not require certified bananas. (50) Another respondent said that "the retail markets in europe are not the same", noting "different retailers, different concepts, different price strategy" between different EU countries. (51) Some retailers have also noted that they cannot purchase yellow bananas from other countries due to limited shelf life and that longer deliveries are more complicated as ripening needs to be controlled, but that it is possible to buy green bananas and ripen them closer to their warehousing facilities. (52) Indeed, the results of the market investigation reveal that where the retailers are purchasing yellow bananas from other countries, they tend to do so from the immediately bordering countries, whereas green bananas are sometimes purchased from further afield, including from growers directly. (53)

(58) Whilst some of the competitors that responded to the Commission's questionnaire stated that they have faced difficulties entering a particular country in the EU, owing to existing competition, presence of multinationals with cheaper logistics costs and local differences, some others stated that they have not faced such difficulties. (54)

(59) On the basis of the evidence before it, and having regard to its decisional practice, the Commission considers that the relevant geographic market for the import and supply of bananas is at least national, although the exact geographic market definition can be left open as no serious doubts arise under any plausible market definition.

5.1.3. Conclusion on the market definition for the import and supply of bananas

(60) For the purposes of its assessment of the present Transaction, the Commission analyses the markets for the import and supply of bananas, which includes (i) both green and yellow bananas; (ii) supplies both to retailers in the modern retail channel (i.e. supermarkets) and to wholesalers. The Commission also analyses a separate product market for the import and supply of Fairtrade and organic bananas (as opposed to conventional bananas). The geographic market is at least national, although the geographic market definition can be left open as no serious doubts arise under any plausible market definition.

5.2. Banana ripening services

(61) Green bananas need to be ripened prior to their sale to customers and end- consumers. The process consists in placing the boxes of green bananas into a sealed ripening chamber where ethylene gas is circulated for 4 to 6 days depending on the degree of ripeness required, in order to gradually ripen the bananas. Once the bananas are ripened, they become more fragile. Therefore, transporting yellow bananas faces more limitations.

(62) Ripening services can be carried out by the importer itself, in its own ripening facility, or by third party independent ripeners. Alternatively, some retailers also operate their own ripening facilities.

5.2.1. Relevant product market

(63) The Parties note that in M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission concluded that the supply of banana ripening services constituted a separate product market. However, the Parties submit that their activities do not overlap in the provision of ripening services as Dole has not been providing any third party ripening in the EEA.

(64) In case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission considered a relevant market for banana ripening services, based on the fact that many independent providers of ripening services exist next to the vertically integrated suppliers and many importers owning ripening facilities sell banana ripening services to third parties. (55)

(65) The results of the market investigation in the present case confirmed the presence of a distinct market for the provision of banana ripening services with independent supplier and third party ripening by importers (56).

(66) On the basis of the evidence before it, and having regard to its decisional practice, the Commission considers that there is a distinct market for the provision of banana ripening services.

5.2.2. Relevant geographic market

(67) In case M.7220 Chiquita Brands International/Fyffes, the Commission considered that the geographic market for ripening services was at least national, based on the limited geographic range where ripened bananas can be transported. (57)

(68) The majority of the competitors that responded to the Commission's questionnaire in the present case stated that the location of their banana ripening facilities limit the geographic scope of their banana sales in the EU, with 200-300 km being on average the radius of deliveries from a ripening facility. (58)

(69) This is consistent with the view expressed by a large number of retailers and wholesalers, who prefer to have ripening facilities as near as possible and to deliver yellow bananas from ripening facilities located in the same country or, depending on distance, some neighbouring countries. Respondents in this case indicated an even larger, up to 500 km radius where ripened bananas could be transported without deterioration of quality and in sufficient quantities. (59)

(70) On the basis of the evidence before it, and having regard to its decisional practice, the Commission considers that the relevant geographic market for the provision of banana ripening services is at least national, although the exact geographic market definition can be left open as no serious doubts arise under any plausible market definition.

5.2.3. Conclusion on the market definition for banana ripening services

(71) For the purposes of its assessment of the present Transaction, the Commission analyses the markets for the provision of banana ripening services, for which the geographic market is at least national, although the market definition can be left open as no serious doubts arise under any plausible market definition.

5.3. Assessment of potential horizontal non-coordinated effects for the import and supply of bananas and horizontal non-coordinated and vertical effects for banana ripening

5.3.1. Import and supply of bananas

(72) The main areas of horizontal overlap between the Parties' import and supply of bananas in the EU are in Denmark and Sweden. Furthermore, affected markets arise in the Czech Republic, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal and Romania.

(73) Since the arguments with respect to the import and supply of Fairtrade/organic bananas are essentially the same as with respect to the import and supply of conventional bananas, for the purposes of this decision, these are dealt with together, highlighting the evidence specific to Fairtrade/organic bananas where relevant.

5.3.1.1. Parties' arguments

(74) The Parties argue that they are not close competitors. While Dole is a traditional banana importer who ships green bananas into Europe and has an established banana brand, Total Produce is a fresh produce distributor and procures bananas from a variety of importers and supplies bananas to its customers together with many other different fruits and vegetables. (60)

(75) The Parties argue that there are numerous other competitors who are able to supply customers in Denmark and Sweden with green bananas, which are easily transportable. With regard to Sweden and Denmark, the Parties identify large competitors, such as Fyffes, Del Monte, Chiquita and Greenyard (Ewerman in Sweden) that are able to supply any national market, in addition to local competitors, such as Poulsen & Finsen with H&P Frugtimport (61) and Eurofrugt in Denmark, and Lundbladh and Biodynamiska in Sweden, as well as potential entrants such as Bama and Agroban. (62)

(76) The Parties also argue that retail markets are concentrated, with four large retail chains (ICA, Coop, Axfood and Bergendahls) controlling 94% of the Swedish retail market, and three (Coop, Dansk Supermarked Group and Rema) accounting for approximately 80% of the banana market in Denmark. In addition, a number of retail chains operate their own wholesale and logistics arm in competition with the Parties. Therefore, according to the Parties, retailers in these countries exercise buyer power and would be able to resist any price increases. (63)

5.3.1.2. Commission assessment

Denmark

(77) With respect to the import and supply of conventional bananas, the Parties have significant combined market shares in Denmark ([70-80]%), with Total Produce's market share of [50-60]% and Dole's [20-30]%. (64) With respect to the import and supply of Fairtrade/organic bananas, the Parties were unable to provide an estimate of the market size of the Danish Fairtrade/organic market. (65) However, they note that Dole's sales are very limited (c. EUR […]) and any market share increment is likely to be very small. In Denmark, approximately 10% to 20% of all bananas sold are Fairtrade/organic. (66)

(78) Whilst some competitors have noted that the supply of bananas market is highly concentrated in Denmark (67) and market participants considered that Total Produce and Dole compete closely in Denmark, (68) the evidence collected during the market investigation reveals that the market for the supply of bananas in Denmark is competitive and is likely to remain so after the Transaction for the reasons set out in recitals (79) to (85).

(79) First, the majority of competitors stated that they could supply yellow bananas to Denmark from another country at a competitive price for regular deliveries on a not insignificant scale, for example from Northern Germany (Hamburg area) or Southern Sweden. (69)

(80) Second, most of the retailers identified a number of potential suppliers of yellow bananas in Denmark. Thus, in addition to the Parties, retailers could potentially source yellow bananas from suppliers such as Chiquita, Citromex, Fyffes, H&P Frugtimport, Max Havelaar, Poulsen & Finsen, Trio Fruit and Uncle Tuca. (70) Most of the respondents concurred that these suppliers would be able to supply them with yellow bananas of quantity and quality sufficient for their needs. (71) Chiquita and Fyffes in particular were identified as strong competitors. In addition to Total Produce and Dole, the majority of competitors ranked Fyffes and Chiquita as the other two important competitors among their top three most important competitors. (72)

(81) The same was found to be true for Fairtrade/organic bananas specifically, with most retailers identifying a number of potential suppliers of Fairtrade/organic bananas of quantity and quality sufficient for their needs, such as Chiquita, Citromex, Don Mario, H&P Frugt, Max Havelaar and Poulsen & Finsen. (73)

(82) Third, many respondent competitors also stated that they could supply green bananas to Denmark, which could then be ripened either at their own or at third party ripening facilities. (74) This is consistent with the view of most of the respondent retailers, who identified a number of potential suppliers of green bananas in Denmark (in addition to the Parties), from whom they could potentially source green bananas of sufficient quantity and quality, such as Chiquita, Citromex, Compagnie Fruitière, Continental, Don Mario, Euro Frugt, Favorita, Max Havelaar, Poulsen & Finsen, Trio Fruit and Uncle Tuca. (75) The majority of respondents have stated that they could also purchase bananas directly from a banana grower. Indeed, a number of them already do so today. (76)

(83) Fourth, there is evidence of countervailing buyer power. The market investigation confirmed the Parties' assertion that the Danish retail market is highly concentrated and that retailers exercise buyer power. (77) A number of competitors provided instances of customers successfully using various strategies (or threats) in their dealings with them, including: (i) switching to an alternative suppliers, (ii) transferring additional costs to the suppliers, (iii) delisting the supplier, (iv) reducing the prominence of the supplier's goods on the shelves, and (v) demanding reverse payments (e.g. discounts, contributions to promotions, stocking fees etc.). (78) This was confirmed by the customer responses to the Commission's questionnaire, the majority of whom confirmed using strategies such as switching or delisting suppliers and demanding reverse payments, as well as, to a lesser extent, transferring costs to suppliers, reducing the prominence of their goods on the shelves and paying in arrears. (79) As one supplier explained: "All customers use the threat of switching to alternative suppliers and/or delisting as part of normal contract negotiations. In some cases the entire contract is lost and in others some part of the supply base may be lost. Support of promotional activities is also a normal part of business with large retail customers and may be agreed as part of an annual contract or on an ad hoc basis during the year." (80) The use of the above-mentioned strategies applies especially to retailers such as supermarket chains, but also to wholesalers (depending on size, as larger wholesalers were noted to behave, and exercise buyer power, in a way similar to larger retailers). (81)

(84) Fifth, a number of competitors have provided examples of instances of customers switching banana suppliers within the last five years. (82) This was confirmed by responses from the customers in Denmark with respect to both yellow and green bananas. (83) As one supplier in Denmark observed, "[a]ll of our customers can switch to alternate suppliers if we don't deliver right quality or price. Especially supermarkets use [the strategy of switching to alternative suppliers] to demand contributions to their campaigns/sales". (84)

(85) Sixth, whilst a very small number of competitors and retailers considered that the Transaction would strengthen the Parties' position in Denmark and that as a result of the Transaction prices may increase, the majority of the competitors and retailers that responded to the Commission's market investigation considered that the Transaction will not have any significant impact for the supply of bananas in Denmark, since the market is likely to remain competitive, with a number of alternative suppliers and with strong retailers exercising significant buyer power. (85) As one respondent noted, "it is the retailers that control the price setting in the market, as bananas are a very important product for retailers" and for this reason they do not consider that the merged Parties "would be able to push through significant price rises". (86)

Sweden

(86) With respect to the import and supply of conventional bananas to retailers and wholesalers, the Parties have combined market shares in Sweden of [50-60]%, with Total Produce having a market share of [20-30]% and Dole [20-30]%. (87)

(87) With respect to the import and supply of Fairtrade/organic bananas in Sweden, the Parties have combined market shares of [50-60]%, with Total Produce having a market share of [30-40]% and Dole [20-30]%. (88) In Sweden, Fairtrade/organic bananas account for a significant share of all banana sales (approximately 55% - 65% of all bananas sold in Sweden are Fairtrade/organic (89)).

(88) Whilst several competitors have noted that the supply of bananas market is highly concentrated in Sweden (90) and market participants considered that Total Produce and Dole compete closely in Sweden, (91) the evidence collected during the market investigation reveals that the market for the supply of bananas in Sweden is competitive and is likely to remain so after the Transaction for the reasons set out in paragraphs (89) to (96).

(89) First, although Sweden is geographically situated further away from ripening facilities in neighbouring countries than Denmark, making the import of yellow bananas into Sweden more logistically complicated and costly, (92) most of the retailers that responded to the Commission's questionnaire identified a number of potential suppliers that would be able to supply them with yellow bananas of quantity and quality sufficient for their needs. (93) Thus, in addition to the Parties, retailers could potentially source yellow bananas from suppliers such as Chiquita, Citromex, Del Monte, Ewerman, Fyffes, KA Lundbladh, and Max Havelaar. (94) Chiquita and Fyffes in particular were identified as strong competitors, with the majority of respondent competitors ranking them (in addition to the Parties) among their top three most important competitors in Sweden (though Chiquita's offering in Fairtrade/organic bananas was noted as being less relevant). (95)

(90) Second, the market investigation revealed that there is no shortage of supply of green bananas into Sweden. The majority of respondent competitors stated that they could supply Sweden with green bananas, which could be easily ripened in ripening facilities in Sweden. Indeed, this appears to be the way that many competitors already operate today. (96) This was confirmed by responses from the retailers, who stated that they could potentially source green bananas of sufficient quantity and quality from suppliers such as Chiquita, Citromex, Del Monte, Favorita, Fyffes and Max Havelaar. (97)

(91) The same was found to be true for Fairtrade/organic bananas specifically, with most retailers identifying a number of potential suppliers of Fairtrade/organic bananas of quantity and quality sufficient for their needs, such as Chiquita, Citromex, Ewerman, Fyffes, KA Lundbladh and Max Havelaar. (98)

(92) Third, the majority of competitors and some of the customers that responded to the Commission's questionnaire have stated that they could purchase bananas directly from a banana grower. Indeed, a number of them already do so today. (99)

(93) Fourth, there is evidence of countervailing buyer power regarding the purchase of bananas. The market investigation confirmed the Parties' assertion that the Swedish retail market is highly concentrated and that retailers exercise buyer power. (100) As one supplier observed, "[t]he Swedish market is competitive and with high trade standards on quality. We believe there is a healthy competition climate on the market." (101) Another supplier in Sweden said that "[s]upermarkets are becoming very strong and they dictate the conditions on the market." (102)

(94) A number of competitors in Sweden provided instances of customers successfully using various strategies (or threats thereof) in their dealings with them, including (i) switching to alternative suppliers, (ii) transferring additional costs to the suppliers, (iii) delisting the supplier, (iv) reducing the prominence of the supplier's goods on the shelves, and (v) demanding reverse payments (e.g. discounts, contributions to promotions, stocking fees etc.). (103) This was confirmed by the customers, the majority of whom admitted to using strategies such as switching or delisting suppliers and demanding reverse payments, as well as, to a lesser extent, transferring costs to suppliers, reducing the prominence of their goods on the shelves and paying in arrears. (104) The use of the above- mentioned strategies applies especially to retailers such as supermarket chains, but also to wholesalers (depending on size, as larger wholesalers were noted to behave, and exercise buyer power, in a way similar to larger retailers). (105)

(95) Fifth, some competitors have provided examples of instances of customers switching banana suppliers in Sweden within the last 5 years. (106) This was confirmed by responses from the customers in Sweden. (107)

(96) Sixth, whilst a very small number of competitors and retailers considered that the Transaction would strengthen the Parties' position in Sweden and that as a result of the Transaction prices may increase, the majority of the competitors and retailers that responded to the Commission's questionnaire considered that the Transaction will not have any significant impact for the supply of bananas in Sweden, since the market is likely to remain competitive with strong retailers exercising significant buyer power, with some customers even expecting lower prices as a result of the Transaction. (108)

Other affected markets

(97) As regards the other affected markets, the Parties have a relatively large combined market share for the supply of conventional bananas in the Czech Republic of [30-40]%, where the Parties each have approximately the same market position (Total Produce – [10-20]%, Dole – [10-20]%), (109) whereas on the other affected markets the market share increment is limited (between 2-8%). These other affected markets are Spain ([30-40]%), Portugal ([20-30]%), Romania ([20-30]%) and the Netherlands ([30-40]%), where the Parties also have a combined market share of [20-30]% for the supply of Fairtrade/organic bananas. (110)

(98) With regard to the Czech Republic, the market investigation has revealed that the market for the import and supply of bananas in the Czech Republic is competitive and is likely to remain so after the Transaction, with retailers and wholesalers identifying a number of alternative suppliers of both yellow and green bananas in the Czech Republic. (111) There also do not seem to be any significant barriers to entry, with the majority of the competitors that responded to the Commission's questionnaire considering it easy to enter and/or gain market share for the sale of bananas in the Czech Republic. (112) Several competitors and customers also provided examples of instances where the customers have switched banana supplier in the Czech Republic. (113) Furthermore, the majority of competitors and customers that responded to the Commission's questionnaires consider that the Transaction will have no or limited effect in the Czech Republic. (114)

(99) With regard to the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania and Spain, the market investigation did not reveal any concerns: (i) entry and/or gain of market share for the sale of bananas in these countries was generally not perceived as difficult; (115) (ii) a number of alternative suppliers of bananas were identified (including for Fairtrade/organic bananas in the Netherlands) and some wholesalers and retailers have indicated that they source from growers directly (in particular in Spain), (116) and (iii) there is evidence of switching suppliers, with several competitors providing examples of instances where their customers have switched banana supplier in these countries. (117) Furthermore, the majority of competitors and several customers that responded to the Commission's questionnaire considered that the Transaction will have no or limited effect in the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Romania. (118)

5.3.1.3. Conclusion

(100) On the basis of the above, the Commission concludes that the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as regards its compatibility with the internal market due to horizontal overlaps in the markets for the import and supply of conventional bananas in Denmark, Sweden, Czech Republic, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal and Romania, and does not raise serious doubts as regards compatibility with the internal market due to horizontal overlaps in the markets for the import and supply of Fairtrade/organic bananas in Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands.

5.3.2. Provision of banana ripening services in Denmark and Sweden

5.3.2.1. Parties' arguments

(101) The Parties submit that Dole has not provided any third party ripening services in any of its facilities in the EEA and generally sells its bananas green – with the exception of Germany, Italy and Sweden, where it has some own ripening facilities. Total Produce has a very limited presence in the supply of third-party banana ripening services in the EEA, the only notable market presence in ripening being in Denmark and in Hungary. Therefore, there is no horizontal overlap between the Parties' banana ripening activities and the Parties argue that the Transaction could not be expected to give rise to any competition concerns as regards the provision of ripening services to third parties.

(102) The Parties argue that once green bananas have been imported into these two countries, there is no difficulty in obtaining ripening services in order for retailers to be supplied with yellow bananas. The Parties state that it is ultimately the customers who determine which bananas should be ripened for them and that the provision of ripening services is in practice not bundled with the sale of green bananas.

(103) In particular, the Parties argue that they are not able to leverage control of their banana ripening facilities in order to foreclose other importers and banana suppliers from the market. Banana ripening is a simple process and does not require significant investment, such that any importer or indeed retailer could easily incur the cost of expanding, or building new, banana ripening capacity. The Parties also point out that there are alternative facilities to which customers can turn for their ripening needs.

5.3.2.2. Commission assessment

Denmark

(104) While there is no horizontal overlap between the Parties in ripening services in Denmark, the Commission has assessed whether the Transaction leads to vertical concerns regarding customer or input foreclosure.

(105) Total Produce has a share of the banana ripening capacity in Denmark of [80-90]%. (119) Dole does not provide ripening services in Denmark. An independent competitor active in third party ripening in Denmark is H&P Frugtimport together with Poulsen & Finsen, (120) with a share of banana ripening capacity in Denmark of [10-20]%.

(106) In the market investigation, the majority of wholesalers and retailers considered that there is currently sufficient ripening capacity to meet their needs. (121) Moreover, some retailers have also indicated that ripening facility providers can and would, on request, expand their ripening capacity. (122) The majority of the customers indicated that they could purchase green bananas from another country for import into Denmark for regular deliveries of not only insignificant scale and at competitive price for ripening in Denmark. (123)

(107) The Commission considers that any attempt by the Parties to foreclose other importers and banana suppliers from the Danish market by leveraging its banana ripening capacity after the Transaction is likely to be unsuccessful for the reasons set out in paragraphs (108) to (112).

(108) First, in particular, since yellow bananas can be transported for distances of between 100 and 500 kilometres (or potentially even further, depending on transport conditions), (124) suppliers and customers in Denmark could still obtain yellow bananas relatively easily from other countries, even if they could not access sufficient ripening capacity in Denmark. Indeed, the majority of competitors and customers that responded to the Commission's questionnaire stated that they could supply Denmark with yellow bananas from another country at a competitive price for regular deliveries of not only insignificant scale and that many of them already do so, notably from ripening facilities and distribution centres in Northern Germany (Hamburg area). (125)

(109) Second, those suppliers who currently have spare capacity are not likely to refuse third party banana ripening in their facilities. As one competitor observed: "For companies who own ripening facilities it is in their interests to maximise utilisation and efficiency therefore they are in general willing to offer service provision to 3rd parties if they have excess capacity". (126)

(110) Third, even though some competitors have indicated that they consider there to be entry barriers to banana ripening in Denmark, (127) the majority of customers do not deem this to be the case, with one customer remarking: "Anybody could build ripening facility". (128) According to the results of the market investigation, a new ripening facility could be constructed for EUR 1-4 million, depending on the capacity required, in as little as 6 months. (129)

(111) Fourth, banana competitors agree and assert that on customer demand they would be ready to set up ripening centres. (130) A large banana competitor remarked to "… position their ripening centres based on demand by customers", adding that "It is not a "push market"' but a "pull market" by the customers." (131) These comments support the Parties' view that customer demand is the driver for the creation of ripening capacities.

(112) Fifth, the market investigation provided evidence that competitors have indeed been opening (and also closing down) ripening centres all across the EU, which seems to be a dynamic process.

(113) As concerns a potential foreclosure of green bananas towards the only third party ripener (H&P Frugtimport) by the Parties, the market investigation provided evidence that the Parties would not have the incentive and the ability to carry it out. A retailer in Denmark confirmed (132) that it is not the ripener but the retailer who negotiates and contracts yearly supply agreements with the importers for the supply green bananas. The retailer also explained that the selection and contracting of the ripener happened independently from the green banana supply process; a separate contract is signed with much longer time horizons, potentially several years. Following these two agreements, the ripener then establishes a contractual relationship for the banana deliveries with the green banana importer.

(114) Resulting from this contractual structure, the importer of green bananas could easily lose its sales to the retailer, the latter having ample choice of alternative green banana suppliers to whom it can easily switch, while at the same time being tied to its ripener through the long-term contract.

Sweden

(115) The Parties' ripening activity in Sweden is entirely captive (133) and they have a significant share of the total banana ripening capacity in Sweden of [50-60]% ([20-30]% Total Produce, [20-30]% Dole). (134)

(116) The Commission considers that any attempt by the Parties to foreclose other importers and banana suppliers from the Swedish market by leveraging its banana ripening capacity after the Transaction is likely to be unsuccessful for the reasons set out in paragraph (117) to (121).

(117) First, the majority of competitors indicated that they would not be able to supply yellow bananas to Sweden for regular deliveries at competitive prices, mainly due to logistical issues, such as excessive lead times (135) for yellow bananas, and freight costs. However, the majority of competitors stated that they could supply green bananas and have them ripened in Sweden, holding that this was possible at competitive prices (136) and also with good logistical solutions for the rest of Sweden. (137)

(118) Second, the Parties estimate that the largest alternative ripener, Chiquita, is also active in third party ripening with ca. 33% capacity share. Smaller players present on the market are Ewerman, Lundbladh and Agroban with 9%, 6% and 3% shares respectively. Therefore, there appears to be sufficient ripening capacity in Sweden beyond the Parties. (138)

(119) Third, customers are of the view that any of the available ripeners in Sweden would ripen bananas for them in order to use up their spare capacity, irrespective of whether or not they are competing with them at the wholesale level. (139)

(120) Fourth, entry barriers onto the Swedish ripening market were considered to be low by respondents. (140) Some of the competitors that do not currently have their own ripening facilities have indicated that, given sufficient demand, they would consider making the investment to build one, (141) for the cost of EUR 1-4 million within 6 months as noted in recital (110) above. The recent entry of a new ripener in Sweden, Agroban, is also indicative of the fact that entry barriers to banana ripening in Sweden are modest.

(121) Fifth, the majority of competitors and customers that responded to the Commission's market investigation did not express any significant concerns in relation to the market for ripening services in Sweden. One customer even expressed the view that the Transaction could lead to lower prices for banana ripening in Sweden. (142)

5.3.2.3. Conclusion

(122) On the basis of the above, the Commission concludes that the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market as regards its impact on competition for banana ripening services in Denmark or Sweden, due to either horizontal overlaps or vertical effects.

6. BAGGED SALAD

(123) Bagged salad is loose or cut salad leaves mixed together or mixed with other cut vegetables, which is washed, dried, packaged and ready to eat. Bagged salad is considered to be a type of convenience product. The Parties' activities in bagged salad overlap only in Sweden and, to a lesser extent, Denmark.

6.1. Market definition

6.1.1. Relevant product market

6.1.1.1. Parties' arguments

(124) The Parties argue that bagged salad should be considered part of the same product market as fresh vegetables. This is because consumers tend to spend a fixed amount of money on vegetables as a whole, and therefore at the retail level all vegetable categories should be considered substitutable. They further argue that the delineation between vegetables and bagged salads is blurred given that bagged salads may contain vegetables such as spinach, carrots, beans, kale, peppers, sweetcorn, celery and spring onions.

(125) The Parties suggest that there is a high degree of substitutability of washed bagged salad with unwashed, and even with whole-head salad. They also reason that salad bars and ready-to-eat meals containing salad compete in the same category with bagged salad, as these are all convenience products. Acknowledging that the prices of these products significantly differ, the Parties argue that these products form part of a continuum of products: from loose salad, over unwashed, to bagged, up to salad bars, where each type of product exerts a competitive constraint on the other.

(126) From a supply-side perspective, the Parties argue that barriers to entry into bagged salad are low, since a washing and bagging facility could be easily set up and the supply chain for vegetables, loose salad and bagged salad are identical, consisting of growing, washing, packing and distributing them to retailers and wholesalers.

(127) The Parties also submit that the supply of bagged salad should not be further distinguished according to the sales channel into sales to retailers or food service, as there is complete supply-side substitutability between the two. Bagging machines can be easily switched to bag larger portions (for example 1 kg bags for food service vs. 150-400g bags for retail customers). They also argue that branding is not an issue, at least not in the Nordics, since retail sales are largely unbranded. They submit that quality standards are equally high for supply to the retailer and food service channels.

6.1.1.2. Commission assessment

(128) A previous case (143) briefly touched upon the market for bagged salad, without a market definition being specified. However, there were some indications from the market investigation that bagged and pre-cut salads could belong to the market for fresh vegetables, given the high degree of substitutability for the consumer between bulk and bagged pre-cut salads.

(129) The market investigation in the present case indicated that washed bagged salad should constitute a distinct product market.

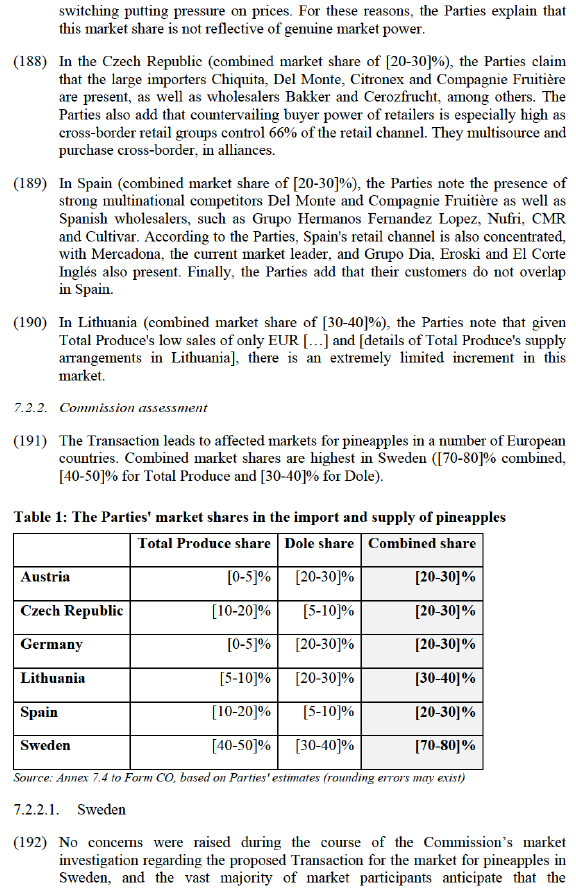

(130) First, the market investigation revealed a limited degree of supply-side substitutability between the manufacture of unwashed salad and vegetables, and bagged salad, as the latter requires the capital-intensive establishment of a washing and bagging facility. The market investigation among salad producers revealed only a few market players to be active in the bagging and washing of salads, whereas many more in the supply of unwashed and whole-head salad and vegetables. The two clusters were clearly separate. (144)

(131) Second, from the demand side, washed bagged salad is not a product that retailers would be able to remove from their shelves on the basis of demand-side substitutability with other fresh vegetable or salad products. Both, suppliers (145) and retailers, agreed that washed bagged salad was a 'must-have' product.

(132) Third, respondents to the market investigation were of the view that there was indeed some functional substitutability between unwashed bagged salad and washed bagged salad. In contrast, they considered that there was less substitutability of washed bagged salad with loose or cut salad, whole-head salad, salad bars and stir-fry vegetables. Respondents also agreed that the prices between washed bagged salad, unwashed salad and whole-head salad were significantly different. (146)

(133) Fourth, respondents explained that the distinction between washed bagged salad and unwashed and whole-head salad is mainly driven by distinct consumer preferences: some held the market was moving towards more convenience and more washed salad, some held the market was moving towards less processing with less washed salad. (147)

(134) Fifth, also, internal documents of the Parties (148) and market feedback suggest that washed bagged salad is a so-called "value-added" product, differentiating it from other loose salad or vegetables: it commands considerably higher prices and also has considerably higher ([5-10]% as opposed to [0-5]% of vegetables in general) operating margins.

(135) As concerns the distinction of sales to retail or to food service channels, these have traditionally been defined as separate markets by Commission precedents. (149) The majority of customers responding to the market investigation in the present case (150) suggested that supplying the food service channel with bagged salad made entry into the retail channel easy. However, all but one competitor suggested the opposite. Some explained that there were structural differences on the two markets (packaging, size and logistics set-up were all different) and also mentioned that entry barriers onto the retail market were high. (151)

(136) For the above reasons, the Commission considers that a distinct product market for the manufacture and sale of washed bagged salad is justified. Whether the relevant product market for washed bagged salad is to be further distinguished by sales to the retail channel and food service channel can be left open because serious doubts arise in the supply of washed bagged salad to both customer groups considered together and individually.

6.1.2. Relevant geographic market

6.1.2.1. Parties' arguments

(137) The Parties submit that the geographic market for washed bagged salad is at least regional, if not EU-wide.

(138) They argue that there are no obstacles to purchasing bagged salad from suppliers in other Member States. The Parties estimate that a typical bagged salad would lose only around one day of its shelf life if it were imported from another EU country, rather than sourced domestically and submit that there is evidence of bagged salads being supplied across borders: [example of cross-border supply by a Party]. Moreover, the largest bagged salad suppliers in the EU – such as Bonduelle, Agrial and Les Crudettes – operate across various countries.

(139) The Parties argue that the 'Made in Sweden' labelling, although mandatory from a legal compliance point of view for all bagged salad suppliers, does not bring any commercial benefit, as bagged salad does not tend to be marketed as a locally produced product.

6.1.2.2. Commission assessment

(140) On a general note, the market investigation confirmed that washed bagged salad was traded across borders and that the washing and bagging facility did not need to be necessarily located in the country of destination. (152) However, only a minority of responding salad suppliers affirmed that they could market their products Europe-wide. While many reported of existing export activities, these tended to be only to neighbouring countries, for example shipping bagged salad from Germany to Denmark, from Italy to France, from France to Belgium, form Spain to Portugal or from the UK to Ireland. Importantly, no evidence was found on any imports into Sweden specifically.

(141) The market investigation found a number of elements pointing to a national market for washed bagged salad.

(142) First, two thirds of responding competitors (153) were of the view that prices for bagged salad were significantly different among the different EU countries.

(143) Second, only a minority of customers said that they would look for bagged salad suppliers abroad if prices in Sweden increased by 10%. (154)

(144) Third, in contrast to the Parties' assessment, the vast majority of customers stated that the "Made in Sweden" label strongly drives the decision of the customer. (155)

(145) Fourth, the large majority of responding suppliers thought that national distribution assets and an established relationship with local customers were necessary to be active on the market. (156)

(146) Sixth, market respondents noted that due to the limited shelf life of the product, a one-day delivery requirement typically limited the delivery radius. (157)

(147) For the above reasons, for the purposes of this decision, the Commission considers that the geographic market for washed bagged salad is national in scope.

6.1.3. Conclusion

(148) For the purposes of its assessment of the present Transaction, the Commission analyses the markets for the supply of washed bagged salad, for which the geographic market is national.

6.2. Assessment of potential horizontal non-coordinated effects in Sweden

6.2.1. Parties’ arguments

(149) The Parties argue that the large bagged salad supplier Salico in Sweden is an effective competitive force constraining the Parties. Although Salico's business currently mainly focuses on supplying the food service channel, they argue that Salico would be able to increase its supply to the food retail channel.

(150) Further, the Parties suggest that alternative suppliers are not constrained by geography or transport and customers could at any time turn to alternative suppliers outside of Sweden, just as the Parties who are supplying customers in Denmark from their Swedish facilities.

(151) Accordingly, the Parties argue that actual and potential suppliers could include manufacturers of bagged salad all over the Nordics and from as far as Italy, from where fresh and whole-head salad is often sourced for the retailers' shelves and as an input for bagged salad production. The Parties argue that companies such as Bonduelle, Agrial and Les Crudettes are active and can supply bagged salad all over Europe, and that bagged salad and frozen vegetable manufacturers such as Orcla and Findus could easily enter the market for bagged salad.

(152) The Parties also argue that any of the numerous suppliers for unwashed loose salad or vegetables could easily expand into creating the production facilities for washed bagged salad, especially if sponsored by a large retailer.

(153) Finally, the Parties submit that they would be constrained by significant countervailing buyer power of the retailers, Sweden being an extremely concentrated food retail market with four large retail chains.

6.2.2. Commission assessment

(154) The Parties have significant market share in washed bagged salad in Sweden (combined [70-80]%), [20-30]% for Total Produce and [50-60]% for Dole, according to the Parties' own estimate. (158) The largest and only significant competitor remaining is Salico.

(155) The market investigation confirmed the Parties' strong position, with market participants estimating their share in Sweden at around two-thirds of the market. (159)

(156) Responding customers stated that in Sweden, Dole and Total Produce were each other's closest competitors for washed bagged salad. (160) Competitors also confirmed the Parties as the main competitors in Sweden, alongside Salico. (161) The market investigation also confirmed that Salico currently focuses on supply to the food service channel, but does also sell to the food retail channel.

(157) As regards the argument of significant bargaining power exercised by large retail chains the Commission observes that indeed the retail market in Sweden is concentrated, with the four large retailers being ICA Sweden, Axfood, Coop Sweden and Bergendahls. However, although one large competitor had experienced loss of volumes or other form of pressure from retailers, (162) there was limited additional evidence in the market investigation of buyer power exercised with respect to washed bagged salad.

(158) Very few customers confirmed having switched suppliers in the past five years; and customer relationships consequently seem to be more long term (alternatively, this could be an indication of limited suppliers to whom customers may switch). (163) Less than half of the retailers claimed having reduced purchases from a supplier in order to negotiate better prices (164) and many do not multisource. (165)

(159) In fact, many customers expressed concerns as to the impact of the Transaction on washed bagged salad in Sweden and a significant majority of the customers who replied considered that the Parties would be in a position to raise prices after the Transaction. (166)

(160) The Commission observes that there are currently limited imports of washed bagged salad into Sweden from abroad, including from Denmark. In the market investigation, while salad suppliers reported of shipping bagged salad for instance from Germany to Denmark, from Italy to France, from France to Belgium, from Spain to Portugal or from the UK to Ireland, they did not report of imports into Sweden specifically.

(161) Some respondents indicated that the limited shelf life of washed bagged salad put a limit on its transport radius. In the case of Sweden in particular, it was also noted that supplying Denmark from Sweden was logistically easier as the factories in the south of Sweden could reach the whole of Denmark with no additional logistical capabilities, whereas for Danish suppliers to supply Sweden meant completely new logistical challenges, for a country several times the size of Denmark. (167) Market participants noted that it would take an extra day to ship washed bagged salad from Denmark to Sweden and limiting the shelf life of washed bagged salad by one day would be unacceptable to retailers, in light of the relatively short shelf life of washed bagged salad. (168)

(162) Indeed, the Parties and also their largest competitor Salico achieve considerable presence on the washed bagged salad market in Denmark, whereas the presence of Danish producers could not be detected in Sweden. In the case of Sweden in particular, respondents mentioned that the higher price level of the surrounding countries made exports from Sweden attractive but did not make imports into Sweden competitive. For example, Denmark or Norway have much higher price levels and production costs.

(163) The market investigation confirmed that customers in Sweden received all of their supplies for bagged salad from Swedish-based suppliers. (169) Furthermore, the market investigation found no evidence of competitors willing to start supplying Sweden even in circumstances where the prices for bagged salad would increase. (170)

(164) As regards barriers to entry and expansion into bagged salad, the market investigation did not support the Parties' view that these were minimal. Rather, respondents considered that barriers to entry were high. In particular, the costs of establishing a new plant were estimated to be between EUR 5 and 10 million and would take on average at least 18 months to build. (171)

6.2.3. Conclusion

(165) On the basis of the above, the Commission concludes that the Transaction raises serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market as regards its impact on competition for bagged salad in Sweden, due to horizontal non-coordinated effects.

6.3. Assessment of potential horizontal non-coordinated effects in Denmark

(166) In Denmark, supplies of bagged salad from Total Produce's and Dole's Swedish plants result in a combined market share of [30-40]%, [10-20]% by Total Produce and [10-20]% by Dole. (172) This market share in Denmark has been achieved by the Parties [details of Parties' supply arrangements].

(167) In contrast to Sweden, the Commission's investigation found evidence of imports of bagged salad into Denmark, not only from Sweden but also from Germany and the Netherlands. In addition, there are a greater number of bagged suppliers present in Denmark. The number of competitors identified by customers (173) is higher than in Sweden, with Hessing, AP Grönt, Yding Grönt, Flensted or Fresh Choice all present.

(168) Respondents to the market investigation did not raise concerns regarding the impact of the Transaction on the bagged salad market in Denmark.

(169) On the basis of the above, the Commission concludes that the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market as regards its impact on competition for bagged salad in Denmark, due to horizontal non- coordinated effects. In any event, the horizontal overlap between the Parties' activities in the supply of bagged salad in Denmark is eliminated by the Final Commitments proposed by the Parties, notably the divestment of Dole's bagged salad business in Sweden.

7. PINEAPPLES

(170) Pineapples are tropical fruit that are resilient to a range of weather conditions. Over 80% of pineapples imported into Europe are of the MD2 variety, which was developed by Del Monte in the mid-1990s to have a sweet taste, high vitamin C content and longer shelf life. Other pineapples in Europe mostly comprise of the Smooth Cayenne, Sugarloaf and Victoria varieties (174).

(171) Some volumes of pineapples are sold as organic, Fairtrade or as dual-certified (i.e. both organic and Fairtrade), although this accounts for only a very limited volume of pineapples (175).

(172) Costa Rica is the leading supplier of pineapples to Europe, accounting for approximately 87% of supply in 2015, with increases in production and productivity still being seen. Brazil, the Philippines and Thailand also produce significant quantities, however Brazil and Thailand do not currently export significant quantities and the Philippines currently focus on supplying Asia and the Middle East. Significant alternative supplies are arriving from countries including Ecuador, Ivory Coast, Panama and Ghana, particularly as they diversify into the popular MD2 variety (176).

7.1. Market definition

7.1.1. Relevant product market

7.1.1.1. Parties' arguments

(173) The Parties argue in favour of a single market for all fresh fruit, with the possible exclusion of bananas. They assert that the consumption and volume of pineapples fluctuate in response to the availability of other fresh fruit, particularly seasonal and local fruit, indicating the presence of demand-side substitution. Furthermore, the Parties argue that consumers tend to spend a fixed amount of money when purchasing fresh fruit in general which are all largely substitutable with each other.

(174) As regards supply-side substitutability, the Parties argue that with the exception of the ripening stage (which is not required for pineapples), the respective supply chains for bananas and pineapples are broadly identical (177), and fruit importers may readily switch to sourcing and supplying pineapples given the similarities in their supply chain to other fresh fruit as regards packing, shipping, distributing and retailing the products. The Parties therefore submit that at least all key banana competitors are able to supply pineapples and that there are in fact also additional competitors who do not supply bananas but other fresh fruit. This large number of competitors therefore constrains the Parties' activities in the market for pineapples.

7.1.1.2. Commission assessment