Commission, June 21, 2019, No M.9234

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

HARRIS CORPORATION / L3 TECHNOLOGIES

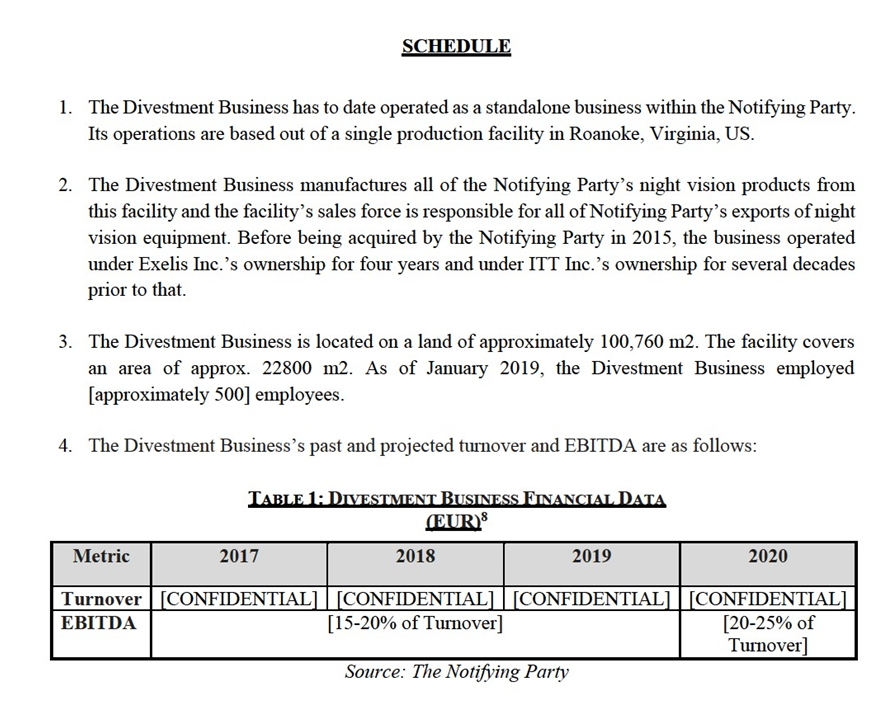

Subject: Case M.9234 — Harris Corporation/L3 Technologies

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) in conjunction with Article 6(2) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 26 April 2019, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which Harris Corporation (‘Harris’, United States) acquires sole control of the whole of L3 Technologies, Inc. (‘L3’, United States) within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation (the ‘Transaction’).3 Harris is designated hereinafter as the 'Notifying Party', while Harris and L3 are together referred to as the ‘Parties’.

1. THE PARTIES

(2) Harris is an international aerospace and defence technology company that supplies products, systems and services for defence, civil government and commercial applications. Harris is headquartered in Florida, United States and it is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

(3) Harris’ business is structured into three main areas of activity as follows:4i. The communication systems segment includes Harris’ night vision products, tactical radio communications equipment, including hand held video data links, for military and commercial customers as well as portable radios and other products for police forces.ii. The electronic systems segment includes the supply of electronic warfare equipment (radars, radar deception devices and electronic attack systems that disrupt adversary signals), avionics (equipment and software used in military aircraft), mission networks and other systems.iii. The space and intelligence systems segment includes products such as remote sensing antennas, position and navigation solutions (new generation GPS), systems supporting missile warning systems, tracking software, earth observation solutions, optic solutions for the aerospace industry and environmental solutions (thermometers, barometers etc.).

(4) L3 is an international aerospace and defence systems company that supplies intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, communications and electronic systems for military, homeland security and commercial aviation customers. L3 is based in New York, United States and is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

(5) L3 is structured into three business segments as follows:5i. The communication and networked systems segment includes network and communication systems, secure communications products, radio frequency components, satellite communication (“SATCOM”) terminals and space, microwave and telemetry products.ii. The intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance segment includes aircraft missionization and sustainment, as well as a broad range of sensor systems for airborne, war fighter, space and ground platforms.iii. The electronic systems segment includes products and services that serve niche markets such as aircraft simulation and training, cockpit avionics, airport security and precision engagement weapons and systems.

2. THE CONCENTRATION

(6) The Transaction will take place pursuant to the Agreement and Plan of Merger dated 12 October 2018, which provides that a wholly-owned subsidiary of Harris, Leopard Merger Sub Inc., merges with L3 as a result of which L3 becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of Harris.6

(7) Upon completion of the Transaction, L3 will be a wholly-owned subsidiary of Harris.

(8) While this suggests that Harris will have sole control of L3, the question of sole or joint control usually depends on the veto rights afforded to the minority shareholder or, potentially, to the target of the acquisition. According to the Commission’s Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice under Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (‘Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice’) veto rights that confer joint control to the minority shareholders typically involve veto over the budget, business plan and the appointment of the senior management.7

(9) In the case at hand, prior to becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of Harris, L3 will get to appoint six members of the combined entity’s board, the other six being appointed by Harris.8 Given that the merged entity’s business plan and budget will be decided on by its board, with this possibility to appoint board members, the pre-Transaction L3 will have influence over the merged entity9 for the period of the mandate of the merged entity’s first board. .

(10) As all members of the combined entity’s board are elected at each annual meeting for terms expiring at the following annual meeting,10 this influence will not last for more than a year. After the first year, sharholders will control the combined entity and L3 will be under the control of the combined entity as the latter’s subsidiary. Thus the current L3 will not influence the merged entity on a lasting basis as required by Article 3 (1) of the Merger Regulation.

(11) Furthermore, as from the first annual meeting following the completion of the Transaction the shareholders that will control the combined entity will be the current Harris shareholders. This is because the pre-completion Harris’s shareholders will own approximately 54% of the combined entity11 and will thus be able to decide on all matters falling within the responsibilities of the shareholders’ meeting. This includes electing the board members of the combined entity, as the latter are elected with a simple majority of shareholder votes.12 Given that, as discussed above, control of the board implies the ability to decide on the business plan, budget and the business policy of the combined entity, the current Harris shareholders will control the combined entity as from the first annual meeting following the completion of the Transaction.

(12) In addition, the current Harris CEO will serve as the chief executive officer of the combined entity as well as the executive chairman of the board for period of two and three years after closing respectively.13 He can only be removed with a supermajority vote of the board members (75% majority).14 This also implies that, in the first year following completion (when half of the board members are appointed by the current L3) the current CEO of Harris cannot be removed from the position of CEO of the merged entity without the consent of the board members appointed by Harris.

(13) Thus, it appears that beyond the first year after the completion of the Transaction, Harris will have sole control over L3 and the current Harris shareholders will have control over the combined entity.

(14) The Commission notes that the current L3 CEO will serve as the vice chairman of the combined entity’s board for a period of three years, subject to a veto by the board taken by a supermajority (75%) vote.15 However, this rule does not affect the control of L3 by Harris as the situation remains that, as discussed above, beyond the first year following the completion of the Transaction, L3 will be a subsidiary of Harris with no control over the board (it will appoint only one member, the vice chairman, out of the twelve) and thus the combined entity. It also does not affect the fact that, as discussed above, the current Harris shareholders will control the combined entity’s board and thus the combined entity as from the first shareholder meeting after completion, which will take place one year after completion.

(15) Finally, a supermajority (75%) of board member votes is necessary for the appointment of the president and the COO of the combined entity in the first three years following the closing of the merger.16 These rules also do not change the fact that, following the first year after completion, Harris will control L3 and the current Harris shareholders will control the combined entity.

(16) It follows from the above that the Transaction will lead to a lasting change of control through the acquisition by Harris of sole control over L3 within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

3. EU DIMENSION

(17) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million.17 (Harris: EUR 5 185 million; L3: EUR 8 491 million.)18 Each of them has an EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Harris: EUR […] million; L3: EUR […] million),19 but neither of them achieve more than two-thirds of its aggregate EU-wide turnover within one and the same Member State.20 The notified operation therefore has an EU dimension.

(18) In the turnover calculation, Harris’ sales to EU customers through the Foreign Military Sales (‘FMS’) program of the US government have been allocated to Harris’ EEA turnover.

(19) By way of background, the FMS program is the US government’s program for exporting defence articles and services to foreign countries and international organizations.21 Eligible partners, which are designated by the US President and currently include approximately 179 foreign countries and international organizations, either purchase in-stock surplus defence articles directly from the US government or mandate the US Defense Security Cooperation Agency (‘DSCA’) to procure supplies on a non-profit basis on their behalf.

(20) The purchases by the US Government through the FMS program (on behalf of the eligible partners) are generally subject to competitive tender procedures. Specifically the purchases are governed by the governed by the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) and the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS).22 These regulations bind the bind the US government to “promote and provide for full and open competition in soliciting offers and awarding Government contracts”23 Competitive procedures include sealed bids, competitive proposals, combinations of competitive procedures like two-step bidding, and others.

(21) There are two exceptions to this general rule. The first exception allows the US government to exclude one or more suppliers from the competitive process in the interest of increasing or maintaining competition, national defence, or security of supply. The second exception allows the US government to negotiate (i.e. without a tender) with a single supplier specified at the outset by the foreign country or international organization. The latter is known as the sole source exception.

(22) [Proportion] of Harris’s FMS sales to the EEA take place under the sole-source exception.24 In such cases the non-US, i.e. in this case EU, customer selects Harris (mostly, though not always, through a tender) and then mandates the US government, more precisely the DCSA, to procure the goods on its behalf.

(23) According to the Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice, the main rule of geographic revenue allocation is that revenue should be allocated to the country where the customer is located, the underlying principle being that turnover should be allocated to the country where competition with alternative suppliers takes place. This location is normally also the place where the characteristic action under the contract in question is to be performed, i.e. where the service is actually provided and the product is actually delivered.25

(24) It is clear from the above description that especially in the case of sales to EU customers under the sole source exemption the customer is located in the EU, the goods are delivered to the EU and the competition with other suppliers takes place in the context of a tender run by an EU customer, typically a government or a defence contractor. Thus Harris’s sales under the sole source exemption should properly be allocated to the EU, even if the ultimate direct purchaser is the US government that acts on behalf on the EU customer. Allocating turnover this way results in a turnover in excess of EUR 250 million for Harris.

(25) The Commission notes that L3’s sales in the EU exceed EUR 250 million even outside the context of the FMS program.

4. OTHER MERGER REVIEW PROCEDURES AND THE SALE OF HARRIS’ NIGHT VISION BUSINESS

(26) The Transaction is subject to mandatory merger control notifications in Canada, Turkey and the US.26 In the context of the US procedure, Harris has offered the sale of its night vision devices business as a remedy to address competition concerns identified by the US Department of Justice (‘DoJ’).

(27) At the time of the notification to the Commission, the Notifying Party had already noted in the Form CO that Harris’ night vision devices business will be divested.27 Moreover, on 4 April 2019, that is several weeks before the formal notification to the Commission, Harris signed an asset purchase agreement with Elbit Systems of America, LLC, the US subsidiary of Elbit Systems Ltd. (“Elbit”)28 pursuant to which Elbit will acquire the divested business. The acquisition of Harris’ night vision devices business by Elbit has not been implemented. Headquartered in Haifa, Israel, Elbit Systems is a global technology and defence company that also has operations in the EU. In 2018, Elbit generated EUR 2.9 billion in revenues, and employed approximately 12,800 people worldwide.29

(28) The DoJ’s assessment is without prejudice to the Commission’s assessment. As the divestment of Harris’s night vision business has not yet been implemented, the Commission has to carry out its assessment on the basis that it is part of Harris. Further, even if the same concerns are identified by the Commission and the same commitments (i.e. the divestment of Harris’s night vision business) fully address these concerns, the Commission has to assess independently whether or not Elbit will be a suitable purchaser. That is to say, should the Commission deem the divestment both necessary and sufficient to address a competition concern pursuant to its own assessment of the Transaction, the sale to Elbit would be conditional on the acceptance of Elbit by the Commission.

5. RELEVANT MARKETS AND COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

(29) The Parties’ activities in the EEA overlap in the following business segments: i) night vision devices (‘NVDs’), ii) image intensification tubes (‘I2Ts’) and iii) hand held video data links (‘HH-VDLs’).

(30) As regards NVDs sales, all but two of Harris’s night vision device product series are solely based on Generation III image intensification technology. The remaining two are fusion NVDs which Harris previously offered in partnership with [partner company] and today offers in partnership with [partner company]. Harris is not active in the supply of thermal NVDs.30 L3 designs, produces, and supplies a range of NVDs based on Generation III image intensification technology, thermal imaging technology, and fusion technology.31

(31) Both Harris and L3 produce and sell Generation III I2Ts. In addition, Harris is currently working on [description of R&D efforts].32

(32) Finally, as regards sales of HH-VDLs, Harris’s EEA portfolio consists of one device (RF-7800T).33 L3 supplies a number of HH-VDLs devices under its Rover brand.34

(33) The Commission will assess whether the Transaction could potentially give rise to horizontal non-coordinated effects in these segments. The Commission will also analyse whether the Transaction could lead to horizontal coordinated effects in any of the overlap areas.

(34) Given that I2Ts and certain NVDs are in an upstream-downstream relationship, and due to the complementarity of the product portfolios in the broader military communications space, the Commission will also assess whether the Transaction would raise vertical or conglomerate concerns.

5.1.Night vision devices (NVDs)

5.1.1. Market definition

5.1.1.1. Product market definition

A) Introduction

(35) NVDs are opto-electric devices that provide users with improved vision in low- light environments and total darkness. The most common application is night vision goggles used by military personne in night missions, but a rifle’s telescopic sight can also be augmented with a night vision device (weapon mounted NVDs).

(36) NVDs can be categorised in several ways:35i. Underlying technology. NVDs can use image intensification technology (image intensification NVDs), thermal technology (thermal NVDs), or a mixture of both technologies (fusion NVDs). In addition, an emerging technology in night vision is digital low light sensor technology.i. Within image intensification NVDs, a further potential distinction can be based on technology generations, which correspond to technological improvements. Devices currently produced and sold fall into Generations I-III, with Generation IV being in advanced stages of development.ii. Within fusion NVDs a further potential distinction is whether the device uses optical or digital image integration.ii. Device type. Regardless of the underlying technology, NVDs can be weapon sight (used on weapons) or goggles (used by troops as eyewear). In addition, there are other types of devices, which include thermal NVDs in the form of portable cameras that work as target detectors and locators; NVDs for tank and armoured vehicle periscopes and vehicle mounted cameras. Goggles can be further classified as follows:i. Mount type: goggles can be hand held, helmet mounted, head-strap mounted and even weapon mountedii. Device shape: goggles can be monoculars, bi-ocular monoculars, binoculars and panoramic.

(37) A brief description of the main NVD technologies (i.e. image intensification, thermal and fusion as well as the different technology generations within image intensification NVDs) is provided in the following paragraphs.

(38) Image intensification technology works by amplifying visible ambient light like starlight and near-infrared light with the help of I2Ts. I2Ts convert ambient photons that hit a light-sensitive photocathode into electrons, then multiply these electrons as they travel through a microchannel plate. The latter is a thin glass disc with millions of small channels each of which releases several electrons for every electron that strikes its inner wall. The multiplied electrons are converted back into photons to render an intensified image on a phosphor screen. Image intensification NVDs thus work with visible and near-infrared light.36

(39) By contrast, thermal NVDs work with invisible mid-infrared and far-infrared waves. Thermal NVDs use the temperature of objects to render visible the infrared waves they emit. Infrared detectors capture infrared waves and pass them on to processors that produce and digitally display detailed temperature patterns known as thermograms.37

(40) Both technologies have their advantages and disadvantages.38 The advantages of Thermal NVDs compared to image intensification NVDs are as follows: they work in complete absence of light solely based on the heat signature of persons and animals; they are able to highlight persons through camouflage and light foliage, fog, or smoke; and they are more suited to certain covert operations because they need not send any signal towards their target. On the other hand thermal NVDs have several drawbacks compared to image intensification NVDs: as they pick up only heat, they are less suited to identify details in the image; they cannot look through glass; they do not work with illumination tools like beacons, strobes and lasers; they are larger and heavier; they consume more power; they are more difficult to maintain; and their use requires more training.

(41) Fusion devices combine image intensification technology and thermal imaging technology.39 By merging the outputs from I2Ts and the thermal images they provide the user with a single integrated image. The integration can happen through optical and digital means, as discussed above. Fusion NVDs take advantage of the strengths of each type of technology: the I2Ts provide an image of the surrounding environment under low-light conditions, while the thermal imaging sensors allow for the detection of objects and targets of interest by superimposing thermal signatures of the objects in the environment. Although fusion devices unite the advantages of both technologies, this comes at the cost of being larger and heavier than non-fusion devices. Naturally, combining two different technologies increases the cost of the device.

(42) As discussed above within image intensification NVDs, a further potential segmentation based on technology generations is based on the technology generation of the most critical component, i.e. the I2T. The US military classifies commercially available I2Ts into three different generations, i.e. Generations I- III40 Generation IV is not yet available on the market and there are ongoing R&D efforts to create it. Broadly speaking, each generation marks a significant development step in tube technology and each generation corresponds to minimum performance criteria relating to range of vision, resolution, signal-to- noise ratio, useful life, or the amount of light it the device requires to function (the lower the better as a new generation device is expected to provide vision in circumstances approaching total darkness). For example, a generation III device has a range of 270 meters, provides clean and bright images, works in near- absolute darkness and has a useful life of at least 10 000 hours.

B) Notifying Party’s view

(43) The Notifying Party considers that the relevant product market should comprise NVDs as a whole and should not be further segmented according to the any of the above criteria.

(44) The Notifying Party submits that customers view all NVDs as interchangeable since they all have the same basic function, i.e., providing improved vision.41Thus the Notifying Party considers that all NVDs are substitutable from a demand perspective regardless of technology, technology generation, device type, mount type or device shape. Further, when it comes to mounting options, the Notifying Party notes that most NVDs allow for different mounting options.42

(45) The Notifying Party further submits that the technologies to manufacture different NVDs are similar, which results in supply-side substitutability.43 More specifically, the Notifying Party submits that switching production from one device type to another (e.g. from weapon sight to goggles or vice-versa) or from one technology to another (e.g. from image intensification to thermal technology or vice versa) is possible in the ordinary course of business.44 Moreover, if a supplier does not have a specific technology type (e.g. has image intensification technology but does not have thermal technology) it can still compete for fusion opportunities by sourcing the missing technology from thurd party providers. For example, Harris sources thermal technology from [supply sources] when it competes for fusion opportunities.45 With regard to NVDs of different shapes, the Notifying Party argues that supply-side substitutability is supported by the fact that most device manufacturers can and do supply all different NVD shapes and that the chassis and optical setup of NVDs account for a fraction of device cost, which is rather driven by the technology (image intensification, thermal or both).46 In relation to different mounting options, the Notifying Party points out that most suppliers offer multiple mounting options for their NVDs, which makes a supply-side distinction unnecessary.47

C) Commission’s decisional practice

(46) In past cases involving NVDs, the Commission has so far left open the precise product market definition.

(47) In Safran/Zodiac and Daimler Benz/Carl Zeiss, the Commission considered that NVDs fall within the category of defence optronics.48 Defense optronics includes(i) thermal imaging units, (ii) residual light amplification units, (iii) visors mounted on land vehicles, ships, aircraft, or submarines, (iv) laser range finders,(v) units for missile guidance systems, (vi) optronic sensors for reconnaissance,(vii) navigation and weapon guidance, and (viii) optronic warning sensors.49 In this classification “thermal imaging units” correspond to thermal NVDs, and “residual light amplification units” correspond to image intensification NVDs.

(48) With regard to further possible segmentation of the category of defence optronics, the Commission noted that technologies used to manufacture various types of optronics equipment are similar but that the supply and demand landscapes are not necessarily the same for all products.50 Ultimately, the Commission left the question of finding separate markets within defence optronics open.

D) Commission’s assessment

(49) The Commission will assess demand-side substitution first, followed by supply- side substitution.

(a) Demand substitution

(50) As a preliminary remark, the responses received in reply to the Commission’s market investigation show a consistent view regarding possible market segmantations. Namely, it appears that there is no demand-side substitution across the distinctions mentioned in Section 7.1.1.1, except for mounting type within goggles (as many goggles are sold with helmet or head-strap mounting options and can also be used in hand) and possibly for digital and optical integration within fusion devices. This is because different NVDs have different characteristics or performance parameters, which result in different intended uses and different prices. Further, customers always appear to specify in detail the NVDs they require (e.g. NVD of a certain technology, of a certain technology generation or equivalent performance metrics, of a certain type, shape), which implies that only NVDs complying with those specifications are compliant offers and thus NVDs with different specifications are not substitutable from a demand perspective. In other words, as is typical in bidding markets for specialized goods, the tenders (i.e. the demand side) are highly specific, i.e. often different from one tender to another and not broad enough to include different versions of the same basic product. As a result, from a demand perspective tenders often result in separate markets and the market definition tends to turn on supply-side substitution: if suppliers can easily adjust their production to meet the tender specifications, the types of devices corresponding to such specifications will belong to the same market; if they cannot, the devices will belong to separate markets.

(51) The detailed evidence relating to demand-substitution across different distinctions is presented below in respect of each distinction.a.i) Distinction based on technology – main technologies

(52) The Commission will discuss first the demand substitutability of the main night vision technologies (image intensification, thermal and fusion).

(53) With regard to the question whether NVDs of different technology types (thermal, image intensification, fusion) can be used interchangeably, a majority of customers51 considered that this is not the case.52. For example, Promoteq AB submitted that “the Technologies provide different capabilities and functionality."53 A large majority of customers confirmed that they or, as the case may be, the final customer (i.e. defence departments) specify in the tender the type of technology requested.54

(54) Customers unanimously agreed that there are significant advantages or disadvantages associated with each technology such that the different technologies are used for different missions or by different users (e.g. special forces, standard infantry, helicopter pilots, non-military users etc.).55 Respondents pointed out that pilots can use only image intensification NVDs as thermal devices do not look through cockpits or windshields; that thermal technology has low battery life (2-3 hours) compared to image intensification NVDs; that fusion devices bring the most advantages but they are bigger, heavier and need more power than non-fusion devices; that thermal NVDs are not limited by the amount of light available whereas image intensification NVDs are; and that, contrary to thermal NVDs, image intensification NVDs allow for the identification of people, the reading of maps due to the better quality image they provide.56 The explanations also highlight that the different technologies are used for different purposes. For example, Australia’s Department of Defence considered that “Some NVD technologies are reliant on large power and ancillary systems which are not suitable for dismounted (non-vehicular) operations. Similarly, equipment in some vehicles (notably aircraft) requires higher levels of technical performance. Hence, different technologies may be used depending on the role or nature of use.”57 Tecnex OY submitted that “Use cases and costs differ currently.”58

(55) Competitors’ responses were fully in line with those of customers. All competitors confirmed that the customers do not consider image intensification, thermal and fusion NVDs interchangeable.59 Thales observed in this regard that “Those devices integrate different types of technologies, and each technology corresponds to different mission-system scenarios. Each of these technologies therefore implies different performances, and different prices”.”60 and that “Customers are knowledgeable to select the technology matching best their key criteria for the operational mission and express explicitly their technology requirements in their RFI/RFQ”61. Elbit submitted that “No, the technologies are very different and therefore also the uses. Each technology has it own pros and cons. The customer will choose the product according to the mission he needs to complete”62, while United Technologies Corporation stated that “products have different tasks and purposes and are not interchangeable....For example, you would use different products depending on the environment, mission, time of day,etc.”63 The large majority of competitors confirmed that customers specify in their tenders the technology requested.64 Competitors also unanimously agreed with the statement that there are significant advantages or disadvantages associated with each technology such that the different technologies are used for different missions or by different users.65 For example, PCO submitted that “there are significant advantages and disadvantages associated with each technology, depending on the situation and mission to be accomplished”66

(56) In summary, the market investigation confirmed that the different technologies cannot be used interchangeably; that customers specify in their tender the technology they request, and that each technology presents advantages and disadvantages and that, as a result, NVDs of different technologies are used for different missions and tasks.

(57) These results exclude the possibility of demand side substitution across different technologies. Already the fact that customers specify in their tenders the technology requested rules out the possibility that NVDs of different technologies are demand-substitutable. If the tenders specify the type of technology (e.g. image intensification NVD), then there is distinct customer demand for a specific technology and suppliers cannot successfully offer an NVD based on a different technology as such a bid would be non-compliant. Likewise, the confirmed advantages and disadvantages of the different technologies are also incompatible with demand-side substitution. If the customer seeks NVDs for missions where there could be no external light or where it is important to see targets behind objects, image intensification NVDs are not an option. Likewise, thermal NVDs are not an option for drivers and pilots or for missions where a long battery time is needed or where the small size of the device is essential. While fusion devices can, in principle, be used instead of both thermal and image intensification NVDs, they are heavier, consume more power and more expensive than image intensification NVDs and thus will not be used in missions where long usage time and small size is essential or requested in tenders with budget constraints.

A.ii) Distinction based on technology – digital low light sensor technology

(58) A significant number of customers and competitors indicated that currently NVDs using digital technology do not match the performance of image intensification NVDs and thus cannot be considered as substitutes.67 For example, L.F.E. SAS stated that “The digital hasn't reached the level of resolution”68 while Safran considered that “We do not believe it is likely that I2T technology will be replaced in the near term.”69 Thales submitted that “Low light sensor technology is not able to meet today I2T performance in low dark, therefore it cannot be a substitute to I2T technology.”70 Similarly, Italy’s Land Armament Directorate considered that “NVDs based on digital low-light sensor technology are suitable just for moonlight condition”71 i.e. they are not suitable for lower light environments, such as starlight, in which image intensification NVDs have been known to operate. Elbit noted that “The low light technology at the present can't compete with the I2T.”72

(59) It follows that digital low light sensor technology is not demand-substitutable with image intensification (and thus fusion) technology. As the main shortcoming of digital low light technology relative to image intensification technology is that it does not perform well in lower light environments, the same problem would be even more present relative thermal technology, as one important characteristic of the latter is that it operates in conditions of total darkness. Thus digital low light technology is not substitutable with thermal technology either.

a.iii) Distinction based on technology generations (only image intensification NVDs)

(60) The majority of customers and competitors confirmed that within image intensification NVDs, NVDs of different technology generations are not perceived by customers as interchangeable.73 For example, Safran noted that “The varying generations of I2Ts offer increasing levels of performance. Moreover, customers usually have specific requirements in terms of technology regarding I2Ts. Therefore they are not « interchangeable » amongst different generations.”74 The technology generations are based on specific technical criteria, like range, battery lifetime, figure of merit (FOM, i.e. Resolution x signal-to-noise ratio) etc. Indeed, NVDs of substantially different performance levels cannot be used interchangeably: if the mission requires high or the highest available performance level, the newest generation device will be sought. Conversely, if for a given mission lower performance level is acceptable or there are budget constraints (older generation products are priced lower than newer generation products) an earlier generation NVD will be requested. An NVD not meeting the performance criteria, or a costlier NVD with much higher performance metrics than requested will not be accepted.

(61) In line with this, both customers and competitors confirm that customers specify the relevant technology generation in their tenders or, failing that, the required performance levels that the device has to comply with, which leads to the same result.75 As discussed before this in itself rules out demand-substitution across generations: if a certain generation or the equivalent performance level is defined in a tender, only devices of the relevant generation will be accepted as older generation devices will not meet the criteria, while newer generation (more performant) devices will be disqualified on price or at least will not be price competitive.

(62) Thus the Commission considers that there is no demand substitutability between image intensification NVDs of different generations

a.iv) Distinction based on integration technology within fusion devices

(63) A fusion NVD integrates the image from an I2T (as in an image intensification NVD) and thermal sensors (as in thermal devices) into one composite, or fused, image. The method to integrate the images can be digital or optical, which raises the question of two distinct product markets within fusion devices based on integration technology.

(64) Market feedback in this respect was mixed. While a slight majority of customers considered that fusion devices with different integration technologies cannot be used interchangeably, competitors had the opposite view. 76

(65) Certain respondents pointed out that fusion NVDs with digital integration perform better but are more expensive, consume more power and heavier (as it needs larger batteries) than fusion NVDs using optical integration. By contrast fusion NVDs using optical integration are less performant but are lighter, more easily portable and less expensive.77 The Night Vision Technologies Handbook of the US Department of Homeland Security mentions the same trade-off between the two devices.78 However, it is unclear whether such differences result in the lack of substitutability from a demand perspective.

(66) A majority of respondents (majority of customers and half of competitors) considered that customers do not specify the integration technology when procuring fusion NVDs suggesting that there is no separate demand for fusion devices with a particular integration technology.79 Instead, separate demand can potentially manifest itself indirectly, through the performance parameters that customers specify in their tenders. However, there is no clear indication in the market investigation whether the required parameters for fusion devices are such that only devices with one type of integration technology can comply with them.

(67) Consequently, the Commission leaves the question of demand substitutability open as it does not influence the competitive assessment.

a.v) Distinction based on device type

(68) As a preliminary remark, the Commission notes that the terminology with regard to device type and mounting options is not entirely consistent between the Form CO and the respondents of the market investigation. The Form CO uses the term “device type” to distinguish between weapon sights and goggles, and the term “mounting type” to distinguish between hand-held, helmet and head-strap mounted NVDs. However, when respondents discuss mounting options they often include weapon mounted NVDs, which can correspond to weapon sights. Further, respondents also mention (thermal) cameras that work as target detectors and locators, which are distinct from hand held goggle NVDs used by military personnel. In addition, some NVD goggles can be mounted on helmet, head- straps and even weapons.80

(69) The responses of the market investigation thus need to be interpreted carefully. For the purposes of this decision, the Commission will use these concepts the following way. By “device type”, the Commission refers to the following categories of devices:i. “weapon sight NVDs” – these are NVDs specifically designed for weapons. For example the L3’s AN/PVS-24 CNVD is “part of the USSOCOM SOPMOD system for M4 Carbine.81 Likewise L3’s CNVD- LR is also designed specifically as a weapon sight.82 Weapon sight NVDs in this sense excludes googles that have several mounting options one of which may include weapon mounting.ii. “Goggles” are eyewear NVDs worn by military personnel. Most often they are helmet mounted or head-strap mounted. Some models can even be weapon mounted, without having been specifically designed as a weapon sight. For example, Harris’s F6015 model can be hand held, helmet mounted, head-strap mounted but can also be weapon mounted as a night scope.83iii. There are other types of devices, which include thermal NVDs in the form of portable cameras that work as target detectors and locators; NVDs for tank and armoured vehicle periscopes; vehicle mounted cameras; NVDs mounted on aircraft and stationiary NVDs. These types are less relevant to the assessment as either one of the Parties or both Parties are inactive in these segments.

(70) By contrast, when the Commission uses the term “mounting option” it only refers to the different mounting option of NVD goggles. This excludes weapon sights, as indicated above, but includes goggles that come with multiple mounting options, one of which can be weapon mounting.

(71) The Commission follows this terminology because it is useful to distinguish the different mounting options within goggles from weapon sights, portable cameras and vehicle mounted cameras even if the terms “portable” and “vehicle mounted” could be also be viewed as mounting options in the broader sense. This is because in the case of mounting options within goggles demand substitution does not even arise as the device itself can be used in different ways, while, as discussed below, the difference appears to be substantial across goggles, weapon sights specifically designed as such, portable cameras, vehicle mounted cameras, NVDs used as periscopes etc.

(72) A majority of both customers and competitors confirmed that weapon sight NVDs and goggles cannot be used interchangeably.84 Indeed, as both types were developed so as to be optimally used on weapons or to be carried by troops, they cannot be used interchangeably, save for in an emergency situation as a makeshift solution. Elbit noted that the uses are very different, that weapon sights are more rigid and heavier than goggles that they require more energy and that the customer requests different features for weapon sights.85 United Technologies Corporation submitted that “The devices are not interchangeable and have different functions.”86 The Ministry of Defence of Lithuania considered that weapon sight and google NVDs “[serve] different purposes and different tactical capabilities”87

(73) In this case too, a majority of customers and all competitors confirmed that tenders specify the device type (weapon sight or goggle) sought,88 which, as discussed before, rules out demand-side substitution in itself.

(74) Portable cameras that work as target detectors and locators also appear to be different from weapon sights and goggles. As Thales noted “In Thales’ opinion, there are different types of NVDs according to:1. Soldier Night Vision Goggles: portable, linked to the helmet on the soldier’s head for the soldier’s mobility. 2. Hand-Held Camera: portable, more weight, for target locator. 3. Weapon sights using Night Vision for aiming. Each of these devices are different end products, with different capacities and performances according to their contribution to the mission. Inside Soldier NVG [Night Vision Goggles], we can consider the different mountings as interchangeable according to the customer’s requirements.”89 Theon also considered that portable cameras are used for long range observation purposes and they are different from night vision goggles.90 Indeed, Thales’s product “Sophie hand held thermal imagers”91 is a thermal NVD used for day/night observation and accurate target location, which is different from goggles worn by combat troops. The same applies to Theon’s DIKTIS-TL92 These devices are predominantly thermal NVDs. Unlike goggles worn by combat troops, these devices are used in more static situations (i.e. for observation). Thales’s response also confirms that the different mounting options within goggle NVDs should not be distinguished.

(75) The Commission also considers that NVDs for tank periscopes, vehicle mounted NVDs, such as Theon’s Urania,93 NVDs mounted on aircraft and stationiary NVDs are different from the NVD types discussed before as well as from each other. An NVD designed to be used on a tank periscope or to be carried by an armoured vehicle or an aircraft clearly cannot be used the same way as weapon sight or a goggle mounted on the helmet or the head-strap of a military personnel or held by the latter in his hand.

(76) Consequently, the Commission considers that there is no demand substitutability across different device types

a.vi) Distinction based on mounting options

(77) As discussed before in Section 5.1.1.1.D.av.), mounting option only refers to the different mounting possibilities within the goggle type NVDs. As such goggles usually come with multiple mounting options, demand substitutability does not even arise as the device itself can be used differently.

(78) The Commission therefore considers that within goggles it is not appropriate to distinguish mounting options from a demand perspective.

a.vii) on device shape

(79) As indicated before in Section 5.1.1.1.D.av.), the different device shapes (monoculars, bi-ocular monoculars, binoculars and panoramic) are assessed only within the goggle device type. Other device types usually have a characteristic shape (e.g. weapon sights are typically monoculars, tank periscopes have a particular design) or not produced in different shapes (portable cameras for observation or vehicle mounted NVDs).

(80) The different shapes have different advantages and disadvantages. Monoculars and bi-ocular monoculars are generally smaller and lighter than binoculars of similar optical properties and panoramic NVDs, which makes monoculars easier to carry. Binoculars and panoramic NVDs have the advantage of improved depth perception at the expense of larger size, weight, and higher power consumption from multiple I2Ts.94

(81) These trade-offs imply that the different shapes are used by different users and for different missions. As Griffity Defense Gmbh noted “For safe driving of vehicles and for flying a double-eyed night vision goggles is necessary. For safe movement in the field and possibly for shooting, a night vision goggles in which one side can be folded up.”95 Accordingly, depth perception is important for driving and flying and thus monoculars and bi-ocular monoculars will not be used for such purpose. At the same, as the quote indicated, it is not possible to fold one side of a binocular NVD up, whereas such functionality is sometimes required for safe movement and shooting. Panoramic NVDs have been developed to solve the limited field of view offered by monoculars, bi-ocular monoculars and binoculars, which creates a tunnel vision effect. While the latter have a field of view of 45 degrees, panoramic NVDs offer a 97 degree field of view, which is similar to daylight field of vision. At the same time a panoramic device uses 4 I2Ts, increasing very significantly the cost of the device and its power consumption. Having such a wide field of view is important in Closed Quarter Combat missions,96 i.e. in missions involving engagement with the enemy at very short range (up to 100 meters) in hand-to-hand combat or using short-range firearms. Thus, for such type of missions panoramic devices will be considered despite the price and battery consumption. The opposite will be the case for missions where a wide field of view is less important than reduced weight and power consumption of the device.

(82) Thus the Commission considers that there is no demand side substitution between NVD googles of different shapes.

a.viii) mand substitutability

(83) Based on the preceding analysis, with the exception of mounting options within the goggle type NVDs and possibly integration technology (digital or optical) in the case of fusion devices, none of the distinctions mentioned are demand substitutable.

(b) Supply side substitution

b.i) Distinction based on technology – main technologies

(84) Competitors were unanimous in their view that switching from the production of NVDs relying on one type of underlying technology to NVDs relying on another underlying technology (e.g. from thermal to image intensification or vice versa) would imply significant technical difficulties and/or costs.

(85) For example, Elbit submitted that “NVD and thermal are very different technologies; in order to develop thermal devices you need to develop advanced software and develop electronic PCB. [printed circuit board] The developing time can reach to several years depending on the credibility of the systems; for military use the required credibility is much higher.”97 PCO SA considered that “according to our best knowledge establishing any entity manufacturing each of the mentioned technologies requires investments ca EUR 100M.”98 United Technologies Corporation also confirmed that the manufacturing processes are different and estimated that switching production would require 24-36 months and millions of dollars for the base technology.99 In Safran’s view the development of any of the technologies requires significant R&D costs and “huge” investments.100

(86) It is clear from these responses that switching production between image intensification and thermal technologies cannot be done in the short term without incurring significant additional costs or risks, in line with the Commission’s Notice on the definition of the relevant market.101 The Commission therefore considers that there is no supply-side substitution across NVDs with different underlying technologies.

(87) A specific question is whether any image intensification NVD supplier or any thermal NVD supplier can swiftly create a fusion NVD by sourcing the other technology from an alternative provider. The responses in this regard were close to equally split.102 However, the explanations given do not support supply-side substitutability.

(88) Pointing to the example of Harris, Elbit submitted that it is possible to be competitive in fusion devices by sourcing thermal technology.103 While this is true, the response did not reveal whether this is possible at short notice and with relative ease, so this response does not support clearly supply-side substitution. The question essentially is whether fusion devices have their own technological challenges or they are very easily put together by combining thermal and image intensification technologies. In this regard Thales considered that “Teaming between partners of each technology will not provide the fusion capabilities. This capacity needs to be developed on top of each existing technology.”104 United Technologies Corporation noted that sourcing the missing technology could be easy but this could involve costs.105 These responses suggest that even through sourcing the missing technology, switching production to fusion technology based devices cannot be done swiftly and without overcoming significant difficulties because fusion devices have their own challenges.

(89) Indeed, as the discussion in Section 5.2.1.4.(B.iv) shows, the market test clearly shows that even changing the integration technology within fusion devices (i.e. switching to optical integration from digital or vice-versa) is not possible at short notice and without great difficulties. This strongly suggests that fusion devices have their own technological challenges as suggested by Thales. These include, but are not necessarily limited to, the integration technology and the need to create a new architecture for the device that houses two types of technology.

(90) The Commission adds that the mere fact of sourcing a technology or partnering with another technology provider can, in itself, be an obstacle to exercising competitive pressure at short notice as the partner may not be available, may not have the capacity or may not provide the requested quality at the requested price etc. Not having the technology in-house always creates such risks. This does not mean that a thermal or an image intensification NVD supplier cannot be a competitive constraint in fusion devices at all (clearly Harris can) but it does make it more difficult to become a credible competitive constraint at short notice and at little cost.

(91) Based on the above the Commission considers that it would not be correct to regard image intensification NVD suppliers and thermal suppliers as competitors in fusion NVDs (which would be the case if supply-side substitution is admitted). The competitive reality rather appears to be that these suppliers are well positioned to enter the fusion NVD market if they so decide, i.e. they would be potential rather than actual competitors if they have the intention to compete.

(92) Given the lack of both demand and supply-side substitutability, the Commission considers that NVDs using image intensification, thermal, and fusion technologies belong to separate markets.

b.ii) Distinction based on technology – digital low light sensor technology

(93) Similar to the distinction between the main technologies, a large majority of competitors considered that switching production between digital low light sensor technology and the main technologies implies significant difficulties and costs due to different manufacturing processes and know-how.106 Thus, the Commission considers that supply side substitution does not apply across NVDs of any technology. Given the lack of demand-side and supply-side substitutability, NVDs using digital low light sensor technology belong to markets separate from thermal, image intensification and fusion NVDs.

b.iii) Distinction based on technology generations – image intensification technology

(94) A majority of competitors considered that switching production between NVDs using different image intensification technology generations would not imply significant technical difficulties or costs.107

(95) Each generation represents a significant improvement in I2T technology, which could suggest that supply-side substitution is asymmetric in that producers of the more advanced version of the same technology can constrain producers of earlier versions but this would not be true vice-versa. However, the majority of image intensification suppliers source their I2T from I2T providers and therefore upgrading their devices to a new generation involves only integrating the new I2T in their products, which can be done with relative ease. As Thales noted “Given each I2T generation implies some R&D and therefore some capacity enhancement, the integrator of the tubes will need to make sure that the rest of the NVDs components are adapted to the new generation. This is only an upgrade of the NVDs and shall not imply significant difficulties.”108

(96) In any event, all significant players in image intensification NVD providers (the Parties, Theon, Thales, PCO, Elbit) have generation III device capability and thus could, in any case, easily supply previous generation devices.109

(97) Generation IV is not yet on the market and based on the market feedback it is not possible to determine with any certainty when it will be available as a product. “Generation IV is largely a marketing description.” according to Australia’s Department of Defence110 Similarly, Griffity Defense Gmbh noted that “There is no Generation IV on the World Market. The aggressive advertisement of company Photonis with tube designation "4G" is nevertheless only an image intensifier of the II generation.”111 Thales considered that “Harris announced it was supported by the US army to develop a generation 4 of tubes for night goggles. Those new tubes may sustain a lower level of light, which is better. However, the development of this new generation of tubes may be only potential.”112 Given the uncertainty about the timing and the development of Generation IV technology, there is no reason to distinguish markets based on generation on a forward looking basis either.

(98) Overall therefore, despite the lack of demand-side substitutability, the Commission considers that there are no separate markets within image intensification technology based on technology generations.

b.iv) Distinction based on integration technology within fusion devices

(99) A large majority of competitors considered that the manufacturing process and know-how required for the manufacturing of fusion NVDs relying on different integration technology (optical or digital) are different such that switching from one to another would imply significant technical difficulties and/or costs.113 Elbit considered that switching from one technology to the other would require significant technical R&D, while Safran noted that the different technologies require different architectures for the NVD.114

(100) While there appears to be no supply-side substitution, demand-side substitution was ambiguous. As this distinction has no influence on the competitive assessment, within fusion devices the Commission leaves the market definition based on integration technology open.

b.v) Distinction by device type

(101) The market feedback was mixed on the question whether a supplier that produces a certain type of device can switch production to produce another type of device without incurring significant difficulties and costs.115 While Thales and Safran considered that the time and cost implications would be significant, PCO S.A. and WB Electronic were of the opposite view.116 Although United Technologies and Elbit agreed with the proposition that the manufacturing processes are different such that switching implies significant time and cost, their explanations gave a more nuanced view. Elbit mentioned both months and years in terms of the time necessary to switch, while United Technologies mentioned that from a sensor perspective the adjustment would be easy.117

(102) The Commission also notes that most major players have in their product portfolio weapon sights and googles, the two most common types of devices within image intensification NVDs. Likewise, most thermal suppliers produce hand held cameras for observation purposes. The distinction therefore may not make a difference with regard to such device types as all major producers would constrain one another even in the case of narrower markets.

(103) However, the question whether separate markets should be distinguished based on device type could be left open as this would not change the competitive assessment.

b.vi) Distinction by device shape

(104) Switching production from one device shape to another appears to be easier than switching production between device types and thus supply side substitution is likely to apply across device shapes. Indeed, doubling or halving the number of eyepieces or objective lenses requires less effort than switching production to create a different device type. [Description] an internal Harris presentation that discusses the competitive landscape. In this document, Harris notes that [description of fused binocular opportunities in the coming years].118 The presentation also reveals that Harris notices the express demand for this particular shaped fusion device around April 2018 and that up to that point it only had monocular fusion NVDs but not a binocular product.119 In respect of this new opportunity, Harris mentions that [internal Assessment]120 The fact that for the next tender a supplier can be competitive in a different device shape strongly suggests supply-side substitution: already in the next opportunity (i.e. in the context of a bidding market, swiftly) a device maker lacking a particular shape can be credible competitive constraint.

(105) The Parties internal documents also indicate that they do not assess competition by device shape. For example an internal Harris SWOT analysis relating to night vision makes no mention of specific competition dynamics related to device shape.121 Likewise, an April 2018 Harris presentation that discusses, inter alia, the different segments within the night vision business makes no mention of a segment based on device shape.122

(106) Moreover, all major NVD suppliers produce the main device shapes (monocular, binocular, or bi-ocular monocular), i.e. they have capabilities to produce all these device shapes. This is true even if, as was the case with Harris in fusion devices, a given supplier’s product portfolio does not include all device shapes in every segment discussed so far (i.e. image intensification, thermal, fusion NVDs and all device types within each of these technologies). As a result the supplier base would be the same even in the case of narrower markets, i.e. it would not be the case that in certain device shapes a given supplier would not be a constraint. Further, there is no indication in the market investigation that any supplier would be particularly strong in one shape versus another or that competition would be driven by very different dynamics and parameters depending on different device shap. Thus the competitive landscape would not necessarily be different if separate markets were defined based on device shapes instead of a unified market.

(107) A potential exception is panoramic devices as not all suppliers produce such devices. However, even in that case it remains true that suppliers can adjust production relatively swiftly and without great difficulties and that suppliers do not seem to assess competition in terms of device shapes.

(108) The Commission therefore considers that supply-side substitution applies across different device shapes and that, as a result, there is no need to distinguish between different markets based on device shape.

E) Conclusion on product market definition

(109) On the basis of the above, the Commission considers that:i. NVDs based on different technologies (image intensification, thermal, fusion and digital low light sensor technology) belong to separate product markets.· Within image intensification NVDs, there are no separate markets based on technology generations.· Within fusion NVDs, the possibility whether fusion devices with optical and digital integration technology belong to separate markets can be left open.ii. The question whether different device types (goggles, weapon sights, hand held cameras for observation, target location and surveillance, vehicle mounted NVDs, tank periscope devices etc.) belong to separate markets can be left open.· Within goggles there are no separate markets based on mounting options (helmet mounted, head-strap mounted, hand held etc.).· Within goggles there are no separate markets based on device shapes (monoculars, bi-ocular monoculars, binoculars and panoramic.)

(110) This results in the following relevant product markets:i. Market for image intensification NVDs, possibly further segmented by device type;ii. Market for thermal NVDs, possibly further segmented by device type;iii. Market for fusion NVDs, possibly further segmented by integration technology (digital or optical). Within each integration technology, the market may be further segmented by device type;iv. Market for digital low light sensor NVDs, possibly further segmented by device type.

5.1.1.2. Geographic market definition

A) Notifying Party’s view

(111) The Notifying Party considers that the geographic market is EEA-wide.123 First, the Notifying Party submits that NVDs have a very low transport-cost-to-price ratio and Harris, L3, and their competitors sell NVDs across the EEA irrespective of the location of their respective production facilities. Second, the Notifying Party argues that EEA customers rarely, if ever, source their NVDs on a national basis. Third, the Notifying Party is not aware of any EEA regulatory or national security restrictions preventing suppliers present in one EEA country from being active throughout the EEA. Certain tenders de facto eliminate US suppliers such as the Parties, as they require suppliers not to be subject to the US International Traffic in Arms Regulations (“ITAR”). However, to the extent any tender within the EEA would be limited to national or European producers only, then neither L3 nor Harris would be able to participate, entailing that the Transaction is neutral with respect to any such tenders.

B) Commission’s decisional practice

(112) In the past, the Commission has left open the possibility to define markets for specific military and defence applications on an EEA-wide or national basis due to, e.g., the existence of specific government regulations (such export restrictions) or national security-related preferences for local suppliers.124

(113) The most recent case involving defence products was Safran-Zodiac case, which also concerned defence optronics (i.e. products that include NVDs). In this case the Commission followed the same approach and left the geographic market definition open (EEA or national) with respect to defence optronics.125 In general (i.e. not necessarily with regard to defence optronics) the Commission noted that the geographic market can vary for different defence products based on how critical the technology is from a strategic and national security point of view. In the case of more sensitive systems and products customers can prefer national capabilities if they are available.126

C) Commission’s assessment

(114) The market investigation broadly confirmed the views put forward by the Notifying Party

(115) A large majority of customers and competitors agreed that NVDs used in different Member States are not significantly different in terms of customer preference, technical specifications, and regulatory requirements such that NVDs intended for one Member State can be used in another Member State.127 TECNEX OY explained that “Typically the end user needs and use cases are quite similar in different countries.”128 Likewise Theon explained that “overall the requirements are the same.”129 The Land Armament Directorate of Italy held similar views: “In the EEA, the regulatory differences among countries are slight”.130 Elbit mentioned that some adjustments may be required (e.g. thermal devices need to be adjusted in countries with colder climates) but this was a minority view.131 Over all the responses suggest demand-substitutability across the EEA.

(116) Moreover, to the extent that there are some demand differences, there was little indication that suppliers could not make the necessary adjustments without incurring significant time or costs. For example, Elbit did not indicate that the adaptations it referred to (e.g. adaptation of thermal devices in countries with colder climates) would require significant time or costs. 132

(117) A large majority of customers and competitors confirmed that apart from the ITAR restriction, there are no regulatory or national security restrictions that would prevent suppliers of NVDs active in one EEA Member State from being active in another EEA Member State.133 With respect to ITAR, the Commission agrees with the Notifying Party that such restriction results in a de facto exclusion of US suppliers in EEA tenders. This would normally justify separating an ITAR market (firms active in the EEA without US suppliers) and a non-ITAR market (all suppliers active in the EEA) but in the current case this is not important as both Parties are subject to ITAR. A majority of competitors also considered that the set of competitors is similar in different EEA countries.134

(118) Thus, both from a demand and supply perspective the market appears to be at least EEA-wide.

(119) As regards a larger than EEA-market, a large majority of customers and competitors considered that there are regulatory restrictions that would prevent suppliers of NVDs from specific countries outside the EEA from being active in tenders in the EEA.135 The explanations, however, were quite vague as they referred to “suppliers that belong to black list”, “countries subjected to embargos” and “political agreements”. A clearer explanation was the already discussed ITAR. The Commission considers these responses refer to the geopolitical reality that NATO countries have some common standards and although these do not bind NATO members formally, these countries do not generally source defence systems from countries that are outside the alliance such as, for example Russia, China and India. This practice is shared not only by NATO members but also by non-NATO members that are NATO allies or closely cooperate with NATO (together: ‘NATO allies’) such as, for example, Australia, Israel, Finland, Sweden etc. For example Sweden’s armed forces actively cooperate with NATO forces and aim to develop interoperable capabilities.136 Within this block of NATO or NATO allied countries the suppliers that supply other armed forces (e.g. Chinese, Russian, Indian armed forces) cannot be considered as competitive constraints. There are some exceptions to this rule, as can be seen from the fact that a Russian supplier sold missile systems in Turkey, a NATO member. However, these exceptions are limited in number and are met with the alliance’s disapproval.137 Thus, NATO and NATO ally countries are also part of the relevant market or suppliers active in these countries need to be taken into account as competitive constraints. Of these two approaches, i.e. EEA- wide market with acknowledging constraints from suppliers in NATO and NATO ally countries or geographic market corresponding to NATO and NATO ally countries, the first approach appears more appropriate as competitive conditions could be more divergent in a large market encompassing not only the EEA but also the US, Japan, Turkey and Brazil.

(120) Although asked specifically on this point, the respondents of the market investigation did not indicate that their responses would differ depending on the product market segment. Thus the above mentioned responses apply to all the various product market segmentations retained by the Commission for the purpose of assessing the Transaction.

D) Conclusion on geographic market definition

(121) On the basis of the above, the Commission considers that the relevant geographic market for all the relevant NVD product markets listed in Section 5.1.1.1.E) comprises the EEA including competitive constraints by firms from NATO or NATO ally countries such as Elbit and the Parties. In the rest of Section 5, when the Commission uses EEA in the context of geographic market, EEA is to be understood in this way.

5.1.2. Competitive assessment – horizontal non-coordianted effects

5.1.2.1. Notifying Party’s view

(122) Although in the Notofying Party’s view there is a unified NVD market, the Notifying Party also puts forward its view on the basis of a segmentation based on technology type, i.e. image intensification NVDs, thermal NVDs and fusion NVDs.

(123) At both of these levels the Notifying Party submits that the Transaction will not lead to a significant impediment of effective competition for the following reasons:i. The combined entity will not have EEA shares indicative of market power.138 The combined entity will have a 2018 EEA value share for all NVDs of below [10-20]%. Moreover, the combined entity will have 2018 EEA value shares not exceeding [10-20]%.ii. The combined entity will face multiple viable competitors for any future night vision device opportunities.139 These include Elbit, Thales, Theon, PCO, Qioptiq and others.iii.The NVDs space is highly competitive, characterized by tender processes.140 NVDs are typically purchased through tender processes. Consequently, as with any bidding market, a small number of competitors is sufficient to maintain a competitive outcome. Moreover, barriers to switching suppliers of NVDs are typically low in the EEA. In addition, the night vision space has been experiencing significant overcapacity since 2012 and significant pricing pressures as a result.iv. The merged entity will face significant buyer power, characteristic of the defence sector in general.141v. Harris and L3 are not particularly close competitors in the EEA.142 This is because they meet in less than 20 % of the EEA tenders.

5.1.2.2. The Commission’s assessment

(124) The Parties’ activities overlap in the following relevant markets:i. Market for image intensification NVDs in the EEA;ii. Market for fusion NVDs in the EEA;iii. If the market for image intensification NVDs is further segmented by device type, the markets for various image intensification NVD types, principally image intensification goggles and weapon sights in the EEA;iv. If the market for fusion NVDs is further segmented based on integration technology, the market for optical integration fusion NVDs in the EEA;v. If the market for optical integration fusion NVDs is further segmented by device types, the markets for various optical integration fusion NVD device types, principally optical integration fusion goggles in the EEA.

(125) The Commission will first analyse the horizontal overlaps at the level of image intensification and fusion NVDs (levels i. and ii. above). This will be followed by a discussion of levels iii.-v.

A) Image intensification NVDs

(a) Relevant characteristics of bidding markets

(126) The market for image intensification NVDs is a bidding market, which implies lumpy demand, i.e. large and infrequent tenders.

(127) As the Commission explained in Case M.7278 – GE/Alstom,143 in markets characterised by tendering, the general mechanism through which a merger can influence competitive outcomes is similar to what occurs in mergers in ordinary differentiated product industries, where firms also compete on price. That is, a merger internalises the competitive pressure that two firms exercised on each other prior to the merger and can lead each of the remaining firms to bid less aggressively post-merger. The precise mechanism through which a merger can influence bids and the indicia of potential unilateral effects, depend on how the tendering process is set up and on the information available to bidders.

(128) There is no presumption in bidding markets that very few bidders (even as low as two bidders) are sufficient to generate a competitive outcome. This extreme result would theoretically only hold if suppliers sell identical products, have identical costs, have sufficient capacity to serve the entire market and have reliable information on the cost of the rival bidders. However, this result no longer holds if firms offer differentiated products, and therefore earn a margin over cost. As in the present case, bidding markets where firms offer differentiated products144 are not characterised by the stylised perfectly competitive outcome and can generate non-coordinated effects if two competing firms merge.

(129) In bidding markets, prices are individually negotiated with each customer and, therefore, suppliers can typically engage in extensive price discrimination across customers. This means that a bid submitted to a customer in a specific tender does not have to be offered on similar terms to other customers in other tenders. The existence of individualised pricing means that the price effects of a merger may be targeted at a particular subset of customers, for example those that are more likely to substitute between the merging parties absent the merger. This follows from the fact that even though a price increase across all customers may not be profitable (given that too many customers would be able to substitute away from the merging parties), a price increase for a specific subset of customers may be so.

(130) In image intensification NVD tenders, prospective suppliers form and submit bids in a context where there is uncertainty over competing bids. In such settings, the pricing incentives of competing firms resemble those at work in ordinary markets with differentiated products. If there is uncertainty on the required price level of the winning bid, each firm faces a trade-off between the probability of winning the tender and the margin earned in case of winning the tender. A higher bid would reduce the probability of winning the tender but would also increase the margin if the bid is successful. This trade-off is equivalent to the standard trade- off between quantity sold and price in an ordinary differentiated goods market, the difference being that in the case of a tender it is the probability of winning rather than actual quantities sold which enters the trade-off. Each bidder therefore chooses its optimal bid in order to optimise the trade-off between expected sales and price and thereby maximises its expected profits. Pricing incentives and the related incentives to exploit market power in bidding markets are therefore analogous to those at work in standard pricing of differentiated products.

(131) The incentives to increase the bids145 in bidding markets characterised by uncertainty over competing bids following a horizontal merger are very similar to those at work in ordinary markets with differentiated products. The primary difference is that the diversion of sales between competing firms should be understood in terms of expected sales (the probability of winning the tender) rather than actual sales. The size of the internalisation effect following a horizontal merger is thus determined by the closeness of competition between the merging firms, understood as the level of diversion between the merging firms before the Transaction (evaluated in terms of winning probabilities), and by the level of pre-merger margins.

(132) Finally, in situations characterised by uncertainty on the quality of rival offerings and on the customer evaluation for each of the products offered, the competitive constraint faced by each bidder is determined by the ex-ante probability that rival bidders may make more attractive offers and thus win the tender. When multiple bidders participate by paying a non-negligible cost, this means that, at the time of bid submissions, those bidders believed that they had a positive probability of winning. Therefore, facing more than one rival bidder typically increases the ex- ante probability that the buyer will prefer a rival offer, and therefore increases the competitive constraint on any given bidder. Therefore, it is not only the runner-up that represented a competitive constraint on the winning bidder, and a decrease in the number of remaining bidders due to the merger may result in a reduction of the competitive constraint faced by the Merged Entity.

(133) In summary, contrary to the arguments of the Notifying Party, just because the market for image intensification NVDs is organized as a bidding market, it does not follow that a low number of suppliers is sufficient to maintain a competitive outcome. In fact the effects of a merger in the market for image intensification NVDs are quite similar to the effects of mergers on ordinary (non-bidding) markets with differentiated products.

(134) This also implies that contrary to the Notifying Party’s argument, market shares are valuable in assessing the market power of a supplier, which is also recognized by the European Court's case-law. Namely, the Court held that the mere fact that a merger takes place on a bidding market, "does not mean that market shares are of virtually no value in assessing the strength of the various manufacturers […],"146