Commission, July 5, 2019, No M.9287

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

CONNECT AIRWAYS / FLYBE

Subject: Case M.9287 – Connect Airways/Flybe

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) in conjunction with Article 6(2) of Council Regulation No 139/2004 (1) and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (2)

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 14 May 2019, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which Virgin Atlantic Limited (“Virgin Atlantic”), Cyrus Capital Partners, L.P. (“Cyrus”) and Stobart Group Limited (“Stobart Group”) acquire, through Connect Airways, within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation joint control of Flybe Group plc (“Flybe Group”) and its trading subsidiaries, Flybe Limited, which owns Flybe Aviation Services Limited, and Flybe.com Limited (Flybe Limited, Flybe Aviation Services Limited and Flybe.com are together referred to as “Flybe”).

(2) Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Group also acquire, through Connect Airways, within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) and 3(4) of the Merger Regulation joint control of Propius Holdings Ltd (“Propius”), Stobart Aviation Limited’s aircraft leasing business, as well as of Stobart Aviation’s operating airline business, Stobart Air Unlimited Company (“Stobart Air”). (3) Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Group are together referred to as “the Notifying Parties”. Flybe Group, Flybe, Propius and Stobart Air are together referred to as the “Target companies”. The operations which bring about the above mentioned concentrations are jointly referred to as the “Transaction”.

1. THE PARTIES

(3) Virgin Atlantic is the holding company of Virgin Atlantic Airways Limited (“VAA”), and Virgin Holidays Limited, a tour operator in the United Kingdom.

(4) VAA is an airline registered in the United Kingdom, which flies to 34 destinations worldwide, including locations across the United States, Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean, and certain destinations in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. VAA primarily provides passenger air transport services but also cargo air transport services as well as maintenance, repair, and overhaul (“MRO”) services.

(5) Virgin Atlantic is currently jointly controlled by Virgin Group Holdings Limited (“Virgin Group”) and Delta Air Lines, Inc. (“Delta”). (4) On 8 January 2019, before the notification of the Transaction, Air France-KLM S.A. (“AFKL”, France), Delta and Virgin Group notified the Commission of their intention to acquire joint control over Virgin Atlantic within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) and 3(4) of the Merger Regulation. That concentration was cleared unconditionally by the Commission on 12 February 2019 .(5)

(6) Consistent with its previous practice, the Commission undertakes to review notified concentrations affecting identical or overlapping markets in the order in which they are notified to it on a “first come, first served” basis, based on the date of notification. (6)

(7) The Commission notes in that regard that, in assessing the competition effects of a proposed transaction under the Merger Regulation, it needs to compare the competitive conditions that would result from the notified concentration with those that would have prevailed in the absence of the concentration. As a general rule, the competitive conditions prevailing at the time of notification constitute the relevant framework for evaluating the effects of a concentration. In some circumstances, however, the Commission may take into account future changes to the market that can be reasonably predicted.

(8) Therefore, the Transaction should be assessed taking into account the acquisition of joint control by AFKL over Virgin Atlantic, together with its current parents Delta and Virgin Group, notified on 8 January 2019 and cleared unconditionally on 12 February 2019.

(9) The starting point for the Commission’s assessment of the Transaction is therefore a market structure in which Virgin Atlantic is jointly controlled by AFKL, Delta and Virgin Group. For the purpose of this Decision, Virgin Atlantic (and its current and future parents, i.e. Virgin Group, Delta and AFKL), Cyrus, Stobart Group are together referred to as the “Parties”.

(10) AFKL and Delta provide passenger air transport services, cargo air transport services, and MRO services. Each of AFKL and Delta flies to more than 300 destinations worldwide. Virgin Group is the holding company of a group of companies active in a wide range of products and services worldwide. In particular, Virgin Group jointly controls West Coast Trains Limited (“Virgin Trains”) together with Stagecoach. Virgin Trains operates the Inter City West Coast rail franchise in the United Kingdom. In addition, Virgin Group is controlling Virgin Holiday, a long-haul scheduled UK tour operator.

(11) Cyrus is an investment adviser managing over USD [4] billion in securities and loans. Its client base is predominantly endowments, foundations and family offices. [confidential information about Cyrus’s investment strategy]

(12) Stobart Group is active in aviation and infrastructure. Stobart Aviation forms one of the three core operating divisions of Stobart Group. Stobart Aviation invests in, develops and operates a number of aviation-related businesses. It controls London Southend Airport, Carlisle Lake District Airport, the Stobart Jet Centre, Stobart Aviation Services, Stobart Air and Propius, its aircraft leasing business.

(13) Flybe Group is the parent company of Flybe. Flybe is a British regional airline with a focus on short-haul, point-to-point flights. It currently operates 190 routes serving 12 countries from 73 departure points in the United Kingdom (29 routes) and other European countries (44 routes). Flybe operates a fleet of 76 aircraft (most of which are small turboprop aircraft with 78 or fewer seats).

(14) In addition to its scheduled passenger regional airline services, charter and cargo transport services and white-label flying for third party airlines, Flybe’s training academy provides pilot, crew, engineering and other training services in-house and to third parties. Flybe also owns a MRO facility servicing both internal and third party customers.

2. CONCENTRATION

2.1Overview

(15) The Transaction comprises the following two transactions, which in turn comprise three acquisitions by Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation.

(16) On 11 January 2019, Connect Airways Limited (“Connect Airways”), a mere acquisition vehicle jointly owned by Virgin Atlantic, through its wholly-owned subsidiary Virgin Travel Group Limited (30%), Cyrus, through its wholly-owned subsidiary DLP Holdings S.à r.l. (40%), and Stobart Group, through its wholly- owned subsidiary Stobart Aviation (30%), announced a recommended cash offer to acquire the entire issued and to be issued share capital of Flybe Group, by way of a scheme of arrangement under Part 26 of the UK Companies Act 2006 (the “first transaction”). (7)

(17) Due to Flybe’s degrading financial position and in order to lessen the risk exposure of Flybe’s commercial counterparties (notably its credit card acquirers), the Parties had to arrange for a quicker change of control over Flybe. On 15 January 2019, Flybe Group and Connect Airways thus entered into a share purchase agreement, pursuant to which Connect Airways acquires the entire issued share capital of Flybe (Flybe Group’s trading subsidiaries) (the “second transaction”). (8)

(18) As part of the second transaction, Stobart Aviation offered to sell to Connect Airways as consideration for its shareholding in Connect Airways (and resultantly Flybe) the entire issued share capital of Propius and 40% of the ordinary share capital of Stobart Air (through Everdeal 2019 Limited). (9)

2.2 Acquisition of joint control over Flybe Group, Flybe, Propius and Stobart Air

(19) The binding terms of the joint bid agreement between Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation dated 11 January 2019 provide for the governance rights of each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation over Connect Airways, defined as a limited company established for the purpose of pursuing the first transaction. (10)

(20) In particular, pursuant to the joint bid agreement with regard to Flybe Group, including its trading subsidiaries and the Shareholders’ Agreement in relation to Connect Airways Limited: (11)

a. [details of governance structure of Connect Airways, giving rise to joint control by each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation];

b. [details of governance structure of Connect Airways, giving rise to joint control by each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation];

c. [details of governance structure of Connect Airways, giving rise to joint control by each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation] (12)

(21) [details of the corporate governance of Connect Airways] (13) [details of the corporate governance of Connect Airways]

(22) In light of the above considerations, each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation has the possibility to exercise decisive influence over Connect Airways, which is used as a mere vehicle for the acquisition of Flybe Group, including its trading subsidiaries, by Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation. (14)

(23) Therefore, as a result of the first transaction, each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation acquires joint control over Flybe Group and its trading subsidiaries.

(24) As part of the second transaction, Connect Airways acquires the entire issued share capital of Propius. Therefore, each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation acquires joint control over Propius.

(25) As part of the second transaction, Connect Airways also acquires 40% of the ordinary share capital of Everdeal 2019 Limited, which indirectly holds 100% of the ordinary share capital of Stobart Air. It has been agreed that, as a result of the shareholders’ agreement and articles of association for Everdeal 2019 Limited: (15)

a. [details of the corporate governance structure of Everdeal, giving control to Connect Airways] (16) [details of the corporate governance structure of Everdeal, giving control to Connect Airways];

b. [details of the corporate governance structure of Everdeal, giving control to Connect Airways]

(26) Therefore, as a result of the second transaction, each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation (through Connect Airways) and Everdeal Employees 2019 Limited acquires joint control over Stobart Air.

2.3 The first and second transaction constitute a single concentration

(27) As indicated in sections 2.1 and 2.2 above, the Transaction comprises the first and second transactions, which in turn comprise the acquisition of joint control by Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation (through Connect Airways), by way of purchase of shares, over (i) Flybe Group, (ii) Flybe, and (iii) Propius and, together with Everdeal Employees 2019 Limited, over Stobart Air.

(28) Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation submit that, although these three acquisitions are not contractually inter-conditional, they are clearly unitary and interdependent and thus constitute a single concentration within the meaning of Article 3 of the Merger Regulation.- (17)

(29) According to paragraph 38 of the Commission Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice, “[t]wo or more transactions constitute a single concentration for the purposes of Article 3 if they are unitary in nature. (…) For the assessment, the economic reality underlying the transactions is to be identified and thus the economic aim pursued by the parties. In other words, in order to determine the unitary nature of the transactions in question, it is necessary, in each individual case, to ascertain whether those transactions are interdependent, in such a way that one transaction would not have been carried out without the other.” In addition, according to paragraph 45 of the Commission Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice, “[a] single concentration may therefore exist if the same purchaser(s) acquire control of a single business, i.e. a single economic entity, via several legal transactions if those are inter-conditional.”

(30) The Commission considers that the three acquisitions by Connect Airways are de facto inter-conditional.

(31) First, the acquisition of Flybe Group (the first transaction) was intended to result in the acquisition of its trading subsidiaries (Flybe) as well. As acknowledged by Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation, the acquisition of Flybe by way of a separate transaction (the second transaction) is only a “technical matter” entailed by the “severe financial distress of Flybe.” (18) After completion of the second transaction, which would precede the first transaction, Flybe Group will have no assets or market presence. However, Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation will remain committed legally to implement the first transaction, subject to shareholder approval. (19)

(32) Second, the acquisition of a 100% shareholding in Propius and a 40% shareholding in Stobart Air forms part of the consideration to be paid by Stobart Aviation for its acquisition of joint control over Flybe via the second transaction. (20) In addition, completion of the two operations (the acquisition of Flybe and the acquisition of the shareholding in Propius and Stobart Air) is to occur simultaneously. (21) Therefore, since neither of the acquisition of Flybe and of the acquisition of Propius and a 40% shareholding in Stobart Air would take place without the other, the two operations are interdependent.

(33) Furthermore, the Commission considers that the three acquisitions are required to transfer to Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation a single business, i.e. a single economic entity managed for a common commercial purpose to which all the assets contribute. The Commission notes in particular that, according to Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation, “the acquisition of Stobart Air and Propius by Connect Airways is therefore an integral part of the formation of the Connect Airways business” and “combining Flybe and Stobart Air in a more integrated commercial co-operation with Virgin Atlantic’s long-haul operations will create a fully-fledged UK network carrier under the Virgin Atlantic brand.” (22)

(34) In light of the above considerations, the first and second transactions, which comprise the acquisition of joint control over Flybe Group, Flybe, Propius and Stobart Air, are interdependent and lead to the acquisition of joint control by Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation over a single business. This jointly controlled single business, consisting of Flybe Group, Flybe, Propius and Stobart Air, will be a full-function joint venture, since it will have sufficient own staff, financial resources and dedicated management for its operations, it will consist of pre- existing businesses, will not be limited to exercising a specific function for its parents thus having its independent market presence, it will not have significant sale or purchase relationships with its parent and will operate on a lasting basis. (23)

(35) Therefore, the first and second transactions constitute a single concentration within the meaning of Article 3 of the Merger Regulation.

2.4 Conclusion

(36) The Transaction, by which Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation acquire joint control over the business made of Flybe Group, Flybe, Propius and Stobart Air constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) and Article 3(4) of the Merger Regulation.

(37) The notification of the Transaction follows the adoption by the Commission of a decision under Article 7(3) of the Merger Regulation. Flybe has experienced negative operational results in three of the last four financial years and its financial position worsened as of spring 2018 leading to Flybe facing the imminent risk of insolvency in mid-January 2019. Virgin Atlantic, Stobart Group and Cyrus requested a derogation from the standstill obligation in mid-February 2019. The Commission granted a derogation decision pursuant to Article 7 (3) EUMR on 21 February 2019 despite prima facie competition concerns considering that the request was justified by the severe financial distress affecting Flybe and the risk that it would stop trading if a change of control would not occur by that date (the “Derogation Decision”). The derogation was granted subject to conditions aiming at preserving effective competition until the Commission completes its merger review process. These conditions included, amongst others, the following: that no voting rights are exercised by Connect Airways in the Target companies and that the acquired business is held separate from Connect Airways. (24)

(38) Pursuant to the Derogation Decision, the acquisition of shares in Flybe, Propius and Stobart Air was completed on 21 February 2019. (25) The first transaction, the recommended cash offer to acquire the entire issued and to be issued share capital of Flybe Group, by way of a scheme of arrangement under Part 26 of the UK Companies Act 2006, became effective on 11 March 2019. (26)

3. EU DIMENSION

(39) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (27) (Virgin Atlantic: c. EUR […]; Cyrus: c. EUR […] million; Stobart Group: c. EUR […] million; Flybe Group: c. EUR […]). Each of them has an EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Virgin Atlantic: c. EUR […]; Cyrus: c. EUR […]; Stobart Group: c. EUR […]; Flybe Group: c. EUR […]), (28) and not each of them achieves more than two-thirds of their aggregate EU- wide turnover within one and the same Member State. (29) The notified operation therefore has an EU dimension.

4. ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK AND MARKET DEFINITION

(40) The activities of the Connect Airways (also through Virgin Atlantic’s parent companies AFKL, Delta and Virgin Group) and the Target companies overlap with regard to (i) passenger air transport (under both the route-by-route and the airport- by-airport approaches), (ii) cargo air transport and, (iii) maintenance, repair and overhaul (“MRO”) services for aircraft. In addition, the Transaction gives rise to vertical relationships in relation to the provision of (i) access to flights of another carrier for connecting passengers (“feeder traffic”), (ii) MRO services, (iii) franchise services, (iv) aircraft leasing services, (v) ground-handling services and (vi) airport infrastructure services.

(41) While the Parties accept that post-Transaction there will be an unbroken chain of control of AFKL (and Delta) over Flybe, they nevertheless claim that AFKL and Flybe would continue to operate as independent undertakings, as AFKL would only have a small indirect interest in Flybe (as the result of its future minority shareholding in Virgin Atlantic), (30) AFKL would only be a minority shareholder in Virgin Atlantic and would not have the ability to unilaterally pass decisions relating to Virgin Atlantic or Connect Airways. [confidential information about the transaction structure and governance] (31)

(42) The Commission acknowledges that AFKL will have only indirect control over Flybe on the basis of the Commission’s clearance decision of 12 February 2019 of the acquisition of joint control over Virgin Atlantic by AFKL, Delta and Virgin Group. However, as concluded in that decision, AFKL acquires joint control over Virgin Atlantic together with Delta and Virgin Group.

(43) With the Transaction assessed in the present decision, each of Virgin Atlantic, Cyrus and Stobart Aviation acquires joint control over Flybe within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

(44) Consequently, AFKL post-Transaction exercises joint control over Flybe through an unbroken chain of control. Even if, as the Parties claim, AFKL would, under the current governance structure, not have the ability to determine business decisions on Flybe in its favour, any such decisions, should they nevertheless pass, would be covered by the Commission’s clearance decision under the Merger Regulation. In line with its decisional practice in cases involving joint control, the Commission will therefore take AFKL’s market position into account for the competitive assessment of the Transaction at hand.

(45) Proper examination of the competitive effects of a transaction under the Merger Regulation rests in particular on a sound understanding of (i) the competitive constraints under which the merged entity will operate, and (ii) the specific causal effects of the transaction on the development of competition in the market.

(46) Along those lines, and taking account of the forward-looking nature of merger control, the Commission will first define the markets that may be relevant for the purpose of the competitive assessment of the Transaction (Sections 4.1-4.8). The Commission will then determine the circumstances likely to prevail on the relevant markets absent the Transaction, including whether the failing firm defence applies (Section 4.9-4.10) and discuss how it will assess the competitive situation of air/rail overlaps for the purpose of this Decision (Section 4.10).

4.1 Air transport of passengers - O&D approach

4.1.1 Relevance of the O&D approach

(47) In respect of air transport services of passengers, the Commission has, in its prior decision practice related to air transport, defined the relevant markets for scheduled passenger air transport services on the basis of two approaches: (i) the “point of origin/point of destination” (“O&D”) city-pair approach, where the target was an active air carrier; (32) and (ii) the “airport-by-airport” approach, when the target held an important slot portfolio. (33)

(48) Under the O&D approach, every combination of an airport or city of origin to an airport or city of destination is defined as a distinct market. Such a market definition reflects the demand-side perspective whereby passengers consider all possible alternatives of travelling from a city of origin to a city of destination, which they do not consider substitutable for a different city pair. The effects of a transaction on competition are thus assessed for each O&D separately.

(49) As a result, every combination of a point of origin and a point of destination is considered a separate market. (34), (35)

4.1.2 Distinction between groups of passengers

(50) The Parties submit that the Commission can leave open the question as to whether a distinction should be made between time sensitive (“TS”) and non-time-sensitive (“NTS”) passengers on short-haul routes and submitted data not distinguishing between categories groups of passengers. (36)

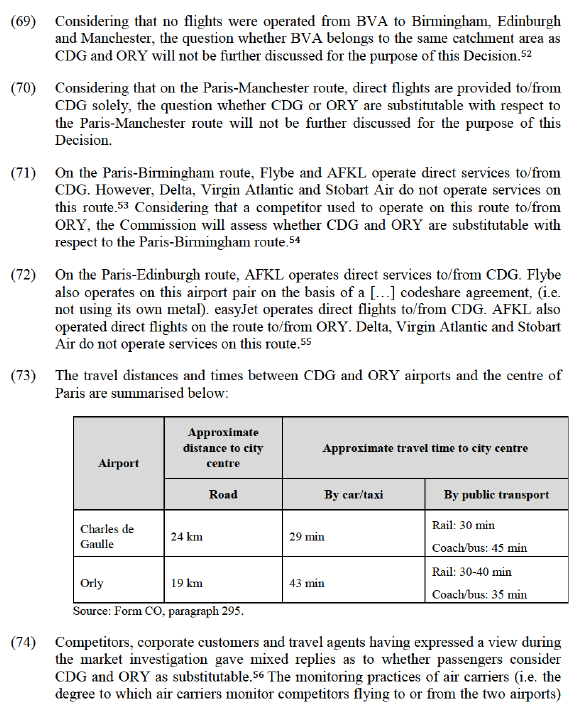

(51) The Commission has in its decisional practice (mostly concerning network carriers) considered distinguishing, for a given O&D route, between (i) TS or premium passengers who tend to travel for business purposes, require significant flexibility for their tickets and are willing to pay higher prices for this flexibility, and (ii) NTS or non-premium passengers who travel predominantly for leisure purposes, do not require flexibility with their booking and are more price-sensitive than the first category. (37)

(52) However, in recent decisions, the Commission has considered that the distinction between TS and NTS passengers has become blurred. Passengers are becoming increasingly price-sensitive and more and more corporate customers apply lowest fare policies. Moreover, on short-haul flights, the distinction between TS and NTS has become somewhat artificial, as the offerings for TS and NTS passengers on these routes have become very similar. The transportation of both categories of passengers usually takes place in the same cabin and further product differentiation (e.g. included meals, newspapers and magazines) are mostly also available to NTS passengers for an upgrade fee. The Commission found that it was not appropriate on short-haul routes to define separate markets for TS and NTS and instead considered a market comprising all passengers.(38)

(53) In this context, the Commission notes that the relevant routes for the purpose of the competitive assessment of the Transaction are all short-haul routes, with Flybe operating only a single cabin. (39)

(54) Moreover, the market investigation has not produced evidence indicating that the Commission should depart from the approach it has recently taken in respect of short-haul routes. In particular, respondents have not submitted material comments suggesting that there is any need to define separate markets for the different categories of passengers for the purpose of analysing the Transaction. (40)

(55) In the light of the above, the Commission concludes that, for the purposes of the Transaction, it is not appropriate to define separate markets for different categories of passengers, whether according to the distinction between TS and NTS passengers.

4.1.3 Distinction between direct and indirect flights

(56) On a given O&D pair, passengers can travel by way of a direct flight between the point of origin and the point of destination or by way of an “indirect” flight on the same O&D pair via an intermediate destination. (41)

(57) In previous cases, the Commission considered that the substitutability between direct and indirect flights on a route-by-route basis depends on various factors, including notably the flight duration, but also price considerations or the inconvenience associated with the indirect flight. In particular, with regard to short- haul routes (generally below 6 hours flight duration) it was considered that indirect flights do not generally provide a competitive constraint to direct flights absent exceptional circumstances, for example, the direct connection does not allow for a one-day return trip or the share of indirect flights in the overall market is significant. (42)

(58) The Parties submit that, should direct and indirect flights be considered substitutable, the Transaction gives rise to 22 affected direct/indirect overlap routes. (43) The Parties consider that the indirect services do not provide a competitive constraint on the direct service on the direct/indirect overlap routes. (44)

(59) However, on 10 routes, also the share of indirect flights in both seasons is significant, i.e. higher than [10-20]%. (45) On 20 of the 22 direct/indirect overlap routes, the direct flight does not allow for a one-day return trip. Therefore, the criterion of exceptional circumstances would in principle be fulfilled.

(60) It can however be left open if direct and indirect flights are substitutable in this case as the Transaction would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible market definition as assessed in Section

5.1.1.6 below.

4.1.4 Airport substitutability

4.1.4.1 Analytical framework

(61) When defining the relevant O&D markets for passenger air transport services, the Commission has previously found that flights to or from airports with sufficiently overlapping catchment areas can be considered as substitutes in the eyes of passengers (particularly if the airports serve the same main city). In order to correctly capture the competitive constraint that flights to or from two different airports exert on each other, a detailed analysis taking into consideration the specific characteristics of the relevant airports is necessary. (46)

(62) The evidence used to characterise airport substitutability includes inter alia a comparison of actual distances and travelling times to the indicative benchmark of 100 km/1 hour driving time, (47) the outcome of the market investigation (views of the competitors and other market participants), and the competitors’ practices in terms of monitoring of competition.

(63) In the present case, taking account of the relevant routes where the Parties’ activities overlap, the question of airport substitutability arises for the routes to or from the following cities: Paris, Birmingham, London and Manchester.

(64) Conversely, for the purpose of this Decision, the question of airport substitutability is not relevant for Berlin, Duesseldorf and Milan. (48)

4.1.4.2 Assessment of airport substitutability

4.1.4.2.1 Paris

(65) Paris has two main airports, namely Paris Charles de Gaulle (CDG) and Paris Orly (ORY). Paris is also served by Beauvais airport (BVA).

(66) In its prior decision practice, the Commission has considered ORY and CDG as substitutable airports, but ultimately left the question open. (49) The Commission has also considered whether CDG and BVA were substitutable. (50)

(67) The Notifying Parties do not contest the Commission’s approach and have provided a competitive assessment for each plausible airport pair. (51)

(68) For the purposes of the O&D assessment of the Transaction, the question of airport substitutability is relevant for the following direct/direct overlap routes: Paris- Manchester, Paris-Birmingham and Paris-Edinburgh.

diverge, making it difficult to draw conclusions. (57) While the majority of travel agents offer flights to and from the two airports to their customers, corporate customers’ replies as to whether they choose flights to/from either CDG and ORY airports are diverging. (58)

(75) The outcome of the market investigation is therefore inconclusive with respect to the substitutability of CDG and ORY on the routes Paris-Birmingham and Paris- Edinburgh.

(76) In any event, for the purpose of the assessment of the effects of the Transaction under the O&D approach, the question whether flights to and from Paris Charles de Gaulle airport and Paris Orly airport belong to the same market can be left open, as the competitive assessment would remain unchanged, under any plausible market definition.

4.1.4.2.2 Birmingham

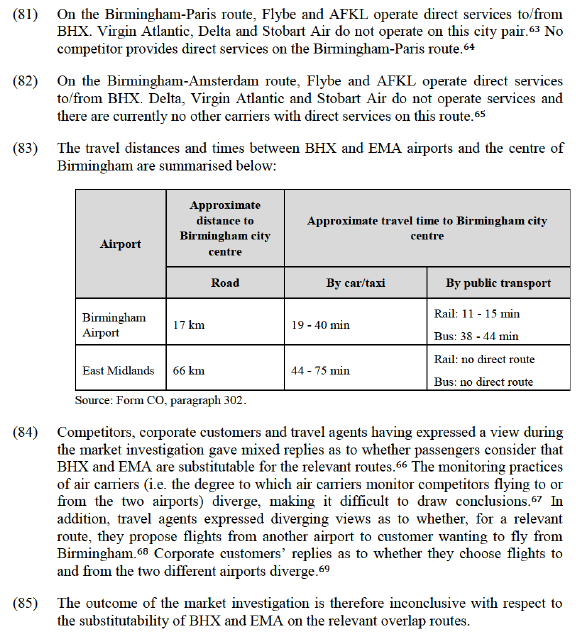

(77) The city of Birmingham is served by two main airports, namely Birmingham airport (BHX) and East Midlands Airport (EMA).

(78) In its prior decisional practice, the Commission has considered whether passenger air transport services to and from Birmingham comprised flights from and to BHX and EMA. While the Commission considered that BHX and EMA were substitutable with respect to the Birmingham-Knock route, the Commission left open whether BHX and EMA were substitutable with respect to the Birmingham-Dublin route. (59)

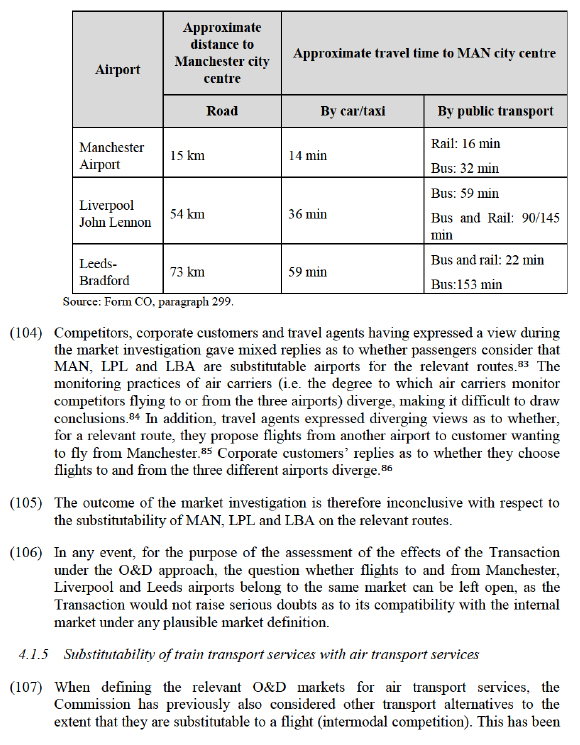

(79) The Notifying Parties do not contest the Commission’s approach and have provided a competitive assessment for each plausible airport pair. (60)

(80) For the purposes of the O&D assessment of the Transaction, the question of airport substitutability is relevant for the following direct/direct overlap routes: Birmingham-Amsterdam and Birmingham-Paris. The question of airport substitutability is also relevant for direct/indirect overlap routes (61) and air/rail overlaps. (62)

(86) In any event, for the purpose of the assessment of the effects of the Transaction under the O&D approach, the question whether flights to and from Birmingham airport and East Midlands airport belong to the same market can be left open as the competitive assessment would remain unchanged, under any plausible market definition.

4.1.4.2.3 London

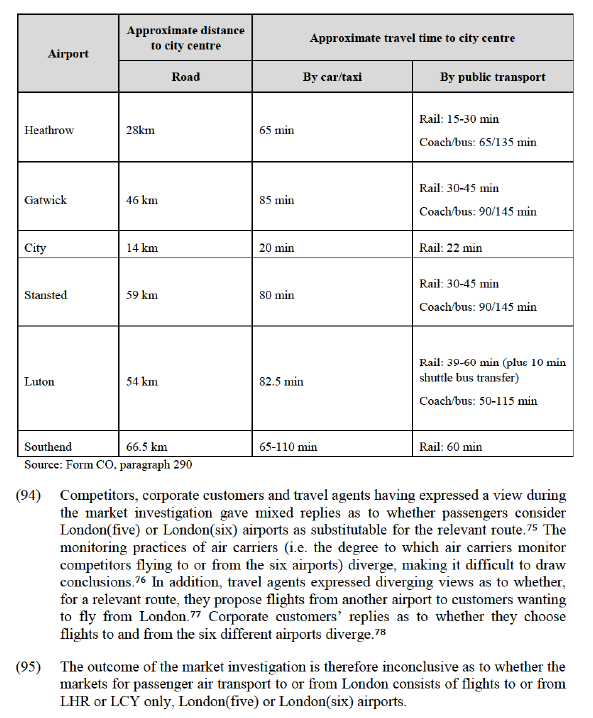

(87) London has six main airports, namely Heathrow (LHR), Gatwick (LGW), City (LCY), Stansted (STN), Luton (LTN) and Southend (SEN).

(88) In previous decisions, the Commission has considered whether short-haul flights to and from London would comprise flights to and from (i) each airport individually, (ii) LHR, LGW, LCY, LTN and STN (“London(five)”) airports, or (iii) LHR, LGW, LCY, LTN, STN and SEN (“London(six)”) airports. With respect to London(five), the Commission left the question open whether they are substitutable in case M.6447 – IAG/bmi. (70) With respect to London(six), the Commission considered that the six airports were substitutable with respect to routes to/from Dublin and Belfast. (71)

(89) The Notifying Parties do not contest the Commission’s approach and have provided a competitive assessment for each plausible airport pair. (72)

(90) For the purposes of the O&D assessment of the Transaction, the question of airport substitutability is relevant for the one direct/direct overlap route, namely London- Amsterdam. The question of airport substitutability is also relevant for one air/rail overlap route, namely London-Edinburgh.

(91) On the London-Amsterdam route, Flybe and AFKL operate direct services to/from LCY. AFKL also operates direct services to/from LHR. None of Virgin Atlantic, Delta or Stobart Air operated on this route. (73)

(92) On the London-Edinburgh route, Flybe operates an air service from LHR and LCY while Virgin Trains operates a rail service from London Euston Station. (74)

(93) The travel distances and times between Heathrow, Gatwick, City, Stansted, Luton and Southend airports and the centre of London are summarised below:

(96) In any event, for the purpose of the assessment of the effects of the Transaction under the O&D approach, the question whether flights to and from London(five) or London(six) airports belong to the same market can be left open because the Transaction would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market, under any plausible market definition.

4.1.4.2.4 Manchester

(97) The city of Manchester is served by three airports, namely Manchester (MAN), Liverpool John Lennon (LPL), and Leeds-Bradford (LBA) airports.

(98) In its prior decisional practice relating to short-haul services to or from Manchester, the Commission examined the effects of the notified transaction on markets comprising flights to and from MAN, LPL and LBA, but left the exact market definition open. (79)

(99) The Notifying Parties do not contest the Commission’s approach and have provided a competitive assessment for each plausible airport pair. (80)

(100) For the purpose of the O&D assessment of the Transaction, the question of airport substitutability is relevant for the following direct/direct overlap routes: Manchester-Amsterdam and Manchester-Paris. This question is also relevant for direct/indirect overlaps, indirect/indirect overlaps and air/rail overlap routes.

(101) On the Manchester-Amsterdam route, Flybe and AFKL operate direct services to and from MAN. easyJet also offers a direct flight on this airport pair. In addition, AFKL operates direct services to and from LBA. Virgin Atlantic, Delta and Stobart Air do not operate on this city pair. (81)

(102) On the Manchester-Paris route, Flybe and AFKL operate direct services to and from MAN. easyJet operates on this route to and from (i) MAN and (ii) LPL.Virgin Atlantic, Delta and Stobart Air do not operate on this city pair. (82)

(103) The travel distances and times between MAN, LPL and LBA and the centre of Manchester are summarised below.

considered in cases where alternative modes of transport on the respective O&D route can be considered comparable in terms of price, quality and (global) travel time and can therefore be considered valuable alternatives by customers. (87)

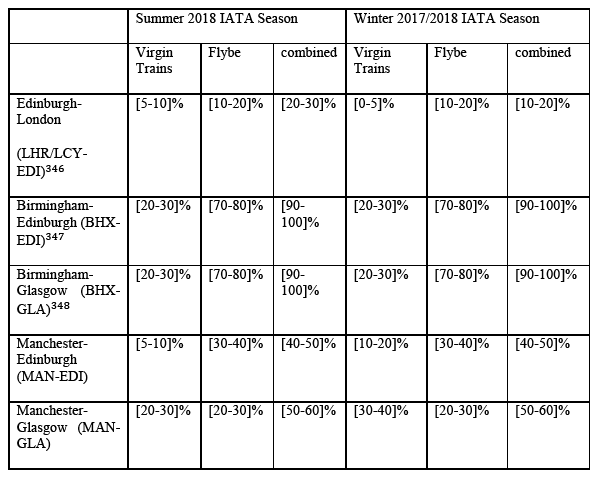

(108) The question of substitutability of train transport services with air transport services is relevant in this case for the London-Edinburgh, Birmingham-Glasgow, Birmingham-Edinburgh, Edinburgh-Manchester and Glasgow-Manchester routes. On those routes, Flybe operates an air passenger transport service. Virgin Trains is operating the West Coast Rail Franchise, which includes train services between London Euston, the West Midlands, North Wales, Manchester, Liverpool,Edinburgh and Glasgow. (88)

(109) The Parties submit that the market definition can be left open as no competition concerns would arise. (89)

(110) The UK Competition and Markets Authority (“CMA”), when assessing rail franchises, takes rail travel as a starting point and considers which other modes of transport to include in its market definition. In this regard, the CMA takes into account (a) the cost of the journey; (b) journey time; (c) time spent travelling to and from the starting point of the journey (for public transport); and (d) frequency and waiting time. (90)à In previous cases, the CMA concluded for the London-Edinburgh and London-Glasgow that air services exert a competitive constraint on the rail services on this flow whereas it was considered that air services did not sufficiently constrain train services on the London-Exeter flow. (91)

(111) The Parties have explained that on Birmingham-Glasgow, Birmingham-Edinburgh, Edinburgh-Manchester and Glasgow-Manchester routes [strategic information on Flybe’s price monitoring]. (92)

(112) From a supply-side perspective, the majority of airlines operating intra-UK routes and expressing their views, explained that they do not monitor rail services. (93)

(113) From a demand-side perspective, the travel agents having expressed their view gave mixed replies as to whether passengers consider rail services as an alternative to air transport within the UK and only around half of those travel agents explained that they also offer train tickets to their customers. (94) When asked if they consider train services as an alternative to air transport with regard to the five air/rail overlaps, only a minority of corporate customers having expressed their views answered in the negative. (95) When asked if they purchase train tickets for the five air/rail overlaps, the majority of corporate customers having expressed a view explained that they purchase train tickets. (96) One customer explained that “Rail travel between London to Edinburgh is utilised due to the availability of an overnight sleeper service. The other routes are three to four hours each way so in terms of overall journey time, taking into account clearing airport security etc., there is no significant time difference. Rail journeys account for approximately 25% of the London to Edinburgh route and 50% of the other routes (versus air travel).” (97)

(114) When asked which criteria would make customers choose rail services over air transport, respondents to the Commission’s market investigation identified most frequently price difference and total travel duration, followed by schedules, but also mentioned other criteria. For example, one customer explained that “[…] travellers can be more productive during train versus air travel due to the improved travel conditions. Encouraging rail travel helps with environmental targets.” (98)

(115) In any event, for the purposes of this Decision, the Commission considers that the question whether air and rail transport services are substitutable on the London- Edinburgh, Birmingham-Glasgow, Birmingham-Edinburgh, Edinburgh-Manchester and Glasgow-Manchester routes can be left open, as the Transaction would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible market definition.

4.1.6 Relevance of the market for air transport services to tour operators

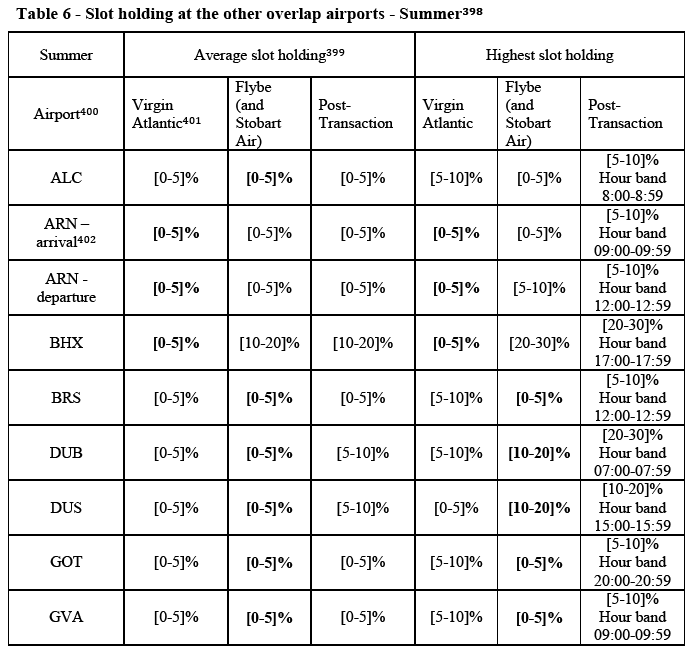

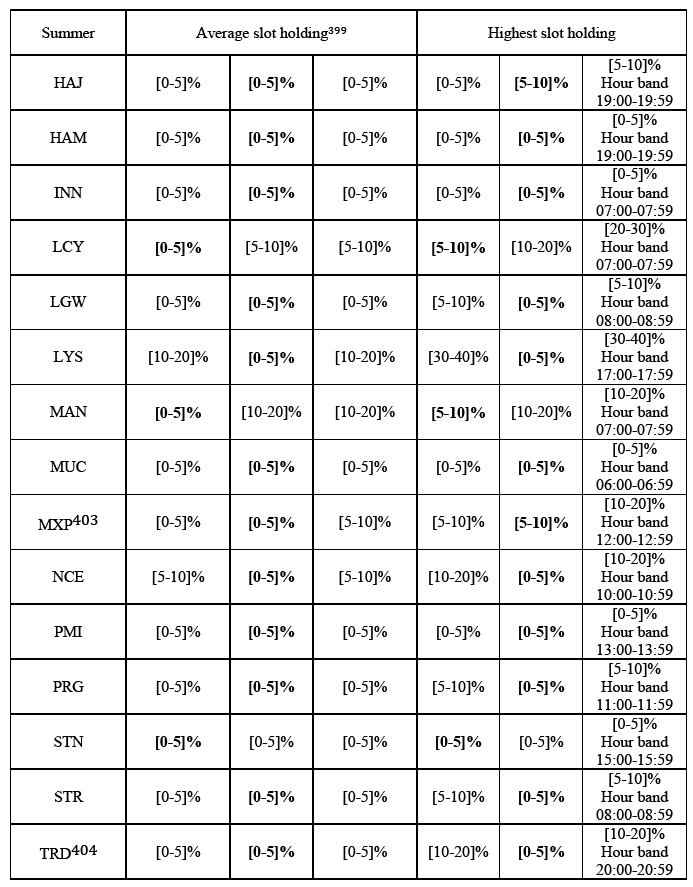

(116) Carriers, both charter and scheduled airlines, may sell seats (or entire flights) to tour operators, which then integrate the flights into package holidays or resell only seats to end customers.

(117) In prior decisions, the Commission has regarded the wholesale supply of airline seats to tour operators as a distinct market from the supply of scheduled air transport services to end customers. (99) From a demand-side perspective, tour operators have different requirements from those of individual passengers (for example, purchase of large seat packages in advance from the start of the season or negotiation of rebates). (100)

4.1.6.1 Parties’ views

(118) The Parties consider that Flybe is only […] in the wholesale supply of seats to tour operators, and, therefore, it is not necessary to consider this market any further. (101)

4.1.6.2 Commission’s assessment

(119) The Commission considers that, for the purpose of assessing the horizontal effects of the Transaction, the supply of airline seats to tour operators only constitutes a meaningful market on routes where either Flybe or Virgin Atlantic (or its parents, in particular AFKL) are active to a significant extent. (102) Indeed, in the absence of any (material) overlap, the market for the supply of airline seats to tour operators cannot be considered as meaningful for the purpose of the Transaction. Therefore, this market is not considered as a relevant market and will not be further assessed in this decision.

4.2 Air transport of passengers – Airport-by-airport approach

4.2.1 Relevance of the airport-by-airport approach

(120) Under the airport-by-airport approach, every airport (or substitutable airports) is defined as a distinct market. Such a market definition has notably been adopted to assess the risks of foreclosure entailed by the concentration of slots at certain airports in the hands of a single undertaking. (103) Under this approach, the effects of a transaction on competition are thus assessed for all O&Ds taken together to or from an airport (or substitutable airports).

4.2.1.1 Introduction

4.2.1.1.1 Slots as an input for air transport services

(121) By virtue of the Slot Regulation, (104) slots, i.e. the permission to land and take-off at a specific date and time at congested airports, are essential for airlines’ operations. Indeed, only air carriers holding slots are entitled to get access to the airport infrastructure services delivered by airport managers and, consequently, to operate routes to or from those airports.

(122) The Commission has, in its prior decision practice, highlighted that the lack of access to slots constitutes a significant barrier to entry or expansion at Europe’s busiest airports, such as London Heathrow airport. (105)

(123) The Commission has also insisted, in the framework of its airport policy, that “slots are a rare resource” and “access to such resources is of crucial importance for the provision of air transport services and for the maintenance of effective competition.” (106)

(124) In addition, the Slot Regulation recalls that, with the increase of air traffic, there is a continuously growing demand for capacity at congested airports. (107) Therefore, the lack of available slots has become a prominent feature of the EU airline industry and is expected to become an even more critical issue for air carriers in the near future.

4.2.1.1.2 Rules for the allocation of slots

(125) In the context of the imbalance between demand and supply of airport capacity, the Slot Regulation defines the rules for the allocation of slots at EU airports. It aims to ensure that, where airport capacity is scarce, the latter is used in the fullest and most efficient way and slots are distributed in an equitable, non-discriminatory and transparent way.

(126) Under the Slot Regulation, the general principle regarding slot allocation is that an air carrier having operated its particular slots for at least 80% during the summer or winter scheduling period is entitled to the same slots in the equivalent scheduling period of the following year (the “grandfather rights”). (108) Conversely, slots which are not sufficiently used by air carriers (below 80%) are reallocated to other air carriers (the “use it or lose it” rule).

(127) The Slot Regulation also provides for the setting up of “slot pools” containing newly-created time slots, unused slots and slots which have been given up by a carrier or have otherwise become available (e.g. via the “use it or lose it” rule). 50% of the slots from the slot pool shall first be offered to new entrants. The other 50% of the slots from the slot pool shall be placed at the disposal of other applicant airlines (incumbent airlines). If applications by new entrants amount to less than 50% of the capacity made available through slots from the slot pool, this remaining capacity shall also be placed at the other applicants’ disposal. (109)

(128) Under the Slot Regulation, slots cannot be traded. They may however be exchanged or transferred between airlines in certain specified circumstances and subject to the explicit confirmation from the coordinator under the Slot Regulation. (110)

4.2.1.2 The Notifying Parties’ views

(129) The Notifying Parties state that the airport-by-airport approach “may have been necessary in the circumstances of these decisions where the O&D approach may have failed to capture all of the structural effects on competition brought about by the transaction. By contrast, in circumstances where the effects of the transaction can effectively be assessed by reference to relevant O&D markets, the parties do not consider that it is necessary to also consider these same effects on an airport- by-airport approach.” (111) The Parties do not consider it necessary to reach a conclusion regarding the relevance of the airport-by-airport approach because they consider that no competition concerns would arise from assessing the transaction under the airport-by-airport approach. (112)

4.2.1.3 Commission’s assessment

(130) According to the Explanatory Memorandum for the Commission Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on common rules for the allocation of slots at European Union airports, (113) “the emergence of a strong competitor at a given airport requires it to build up a sustainable slot portfolio to allow it to compete effectively with the dominant carrier (usually the “home” carrier).”

(131) In this context, in a number of prior decisions related to transactions entailing the transfer of slots at certain airports, the Commission has considered the effects of the transaction on the operation of passenger air transport services at a given airport in terms of the slot portfolio held by a carrier at the airport, without distinguishing between the specific routes served to or from that airport. (114) Under this approach, the Commission assesses how the transaction strengthens the merged entity’s position at certain airports and the potential effects thereof on the merged entity’s ability and incentive to foreclose other air carriers from accessing the relevant airport infrastructure services. Foreclosing access to airport infrastructure services may in turn foreclose those other air carriers from operating routes from/to the relevant airports. (115)

(132) In this respect, the Commission notes that the O&D approach and the airport-by- airport approach are complementary and not mutually exclusive. In cases where the transaction involves the acquisition of an active air carrier and brings about a transfer of slots, it is appropriate to conduct an analysis under both approaches for a full competitive assessment of the transaction.

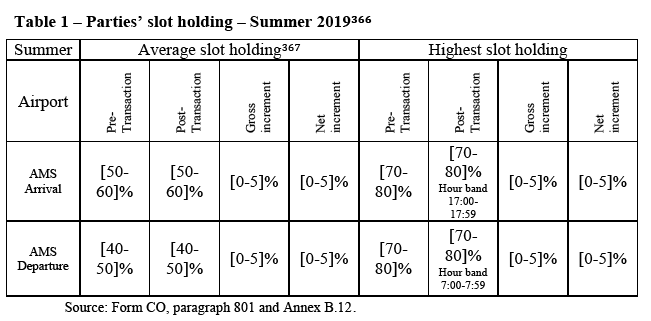

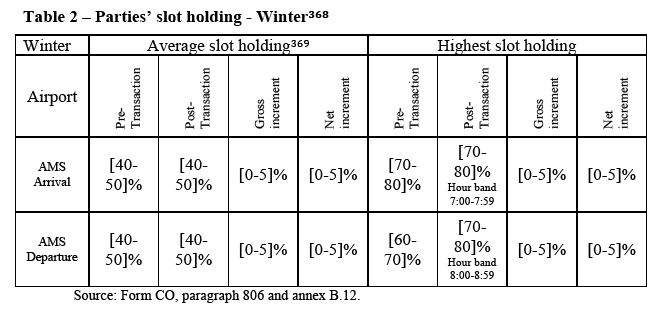

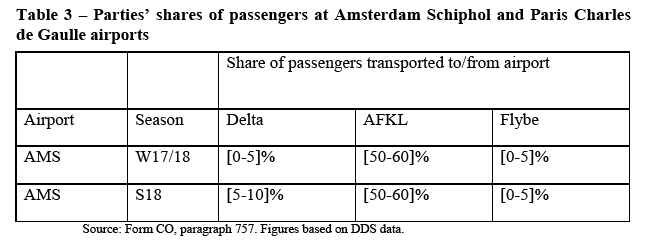

(133) In the present case, Flybe, Stobart and Virgin Atlantic (or its parents AFKL, Delta and Virgin Group) have overlapping slot portfolios at 29 coordinated (Level 3) airports, including Amsterdam Schiphol and Paris Charles de Gaulle airport. (116) The potential effects resulting from this overlap are not fully covered by the O&D approach.

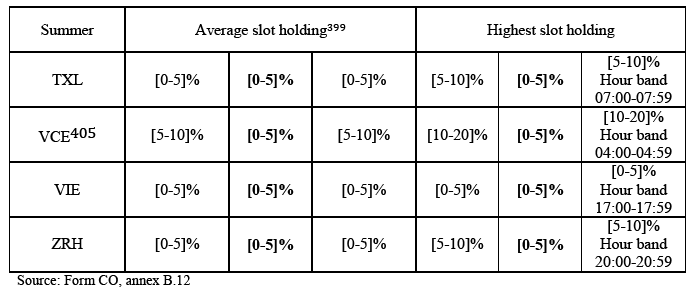

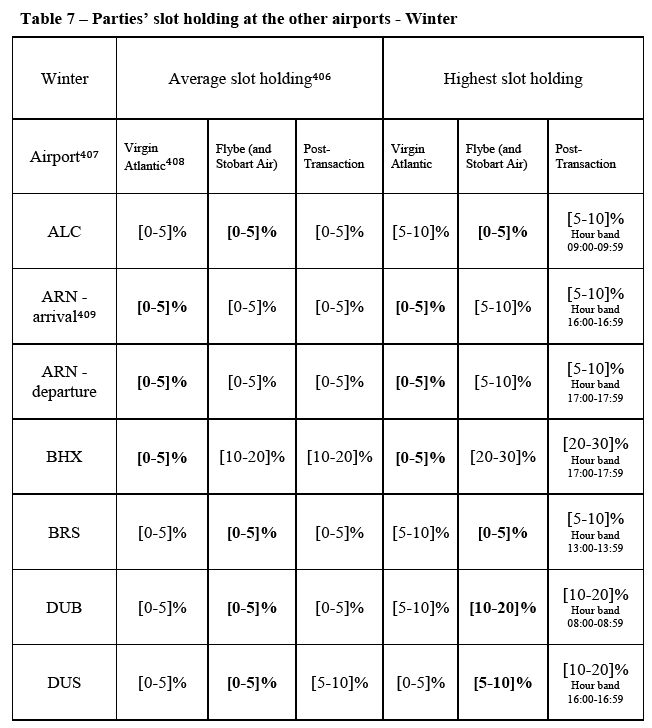

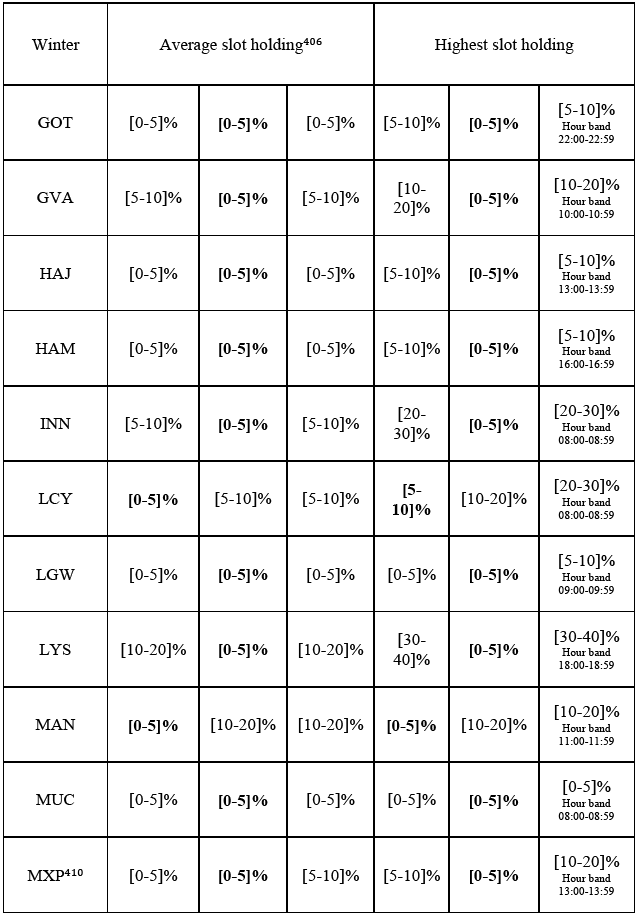

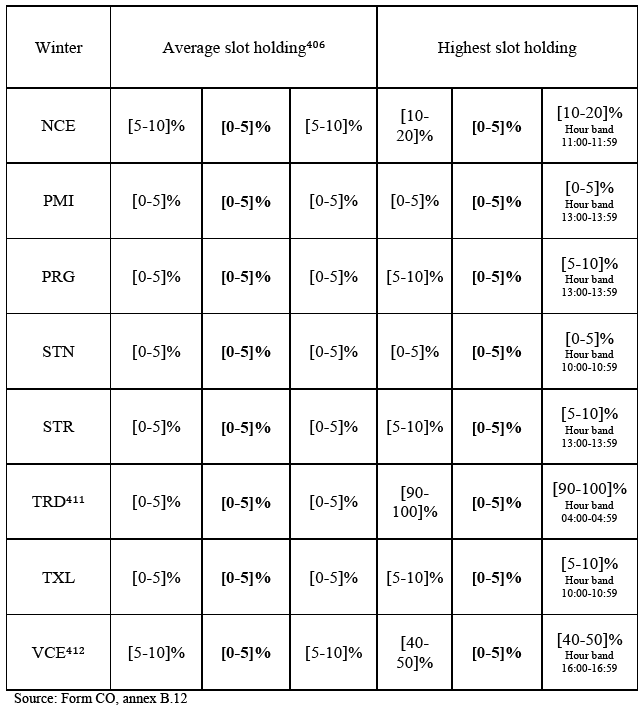

(134) Therefore, in view of the above, the Commission considers it appropriate, for the purpose of this Decision, to apply the analytical framework designed to address the risk of foreclosure from access to airport infrastructure services and air transport of passengers to and from the relevant airports, potentially resulting from the acquisition of joint control over Flybe, at airports where the slot portfolio of Virgin Atlantic (including Virgin Atlantic’s parent companies) and Stobart Group overlapped with the slot portfolio of Flybe, in Winter 2018/2019 and/or Summer 2018 IATA Seasons. (117)

(135) The Commission will consider below the various possible delineations of these two relevant markets under the airport-by-airport approach (i.e. the markets for air transport services of passengers to or from the relevant airports and the market for airport infrastructure services provided at the relevant airports).

4.2.2 Relevant markets for the assessment of the effects of the Transaction on passenger air transport services under the airport-by-airport approach

4.2.2.1 Air transport services of passengers to or from the relevant airports

4.2.2.1.1 Relevant product market

(136) In prior decisions, when applying the airport-by-airport approach, the Commission has not deemed it necessary to consider the same distinctions as those considered when each O&D market is examined separately (e.g. time sensitive vs. non-time sensitive passengers, direct vs. indirect flights, charter flights vs. scheduled flights, wholesale vs. retail supply of airline seats). (118) On the basis of the information in the file, the Commission considers that there are no grounds for it to deviate from this past practice for the purposes of this Decision.

4.2.2.1.2 Relevant geographic market

(137) In prior decisions, the Commission has considered whether the relevant airports were substitutable with other airports in view of their overlapping catchment areas. (119)

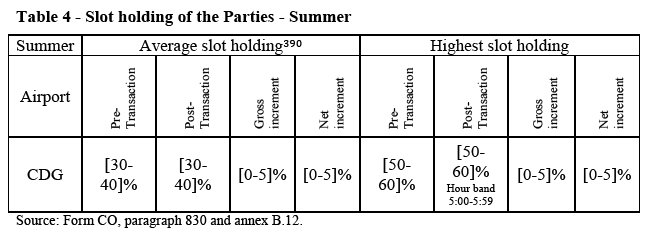

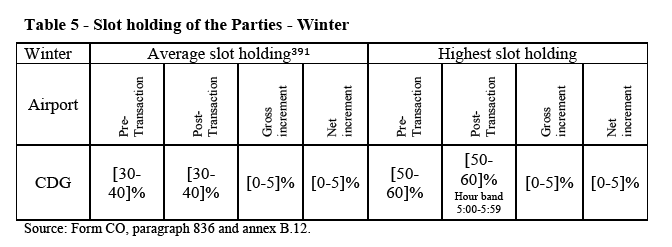

(138) With respect to the overlap airports where the question of a broader geographic scope encompassing several airports might be relevant, the Commission will focus its assessment of airport substitutability where the Parties would have a slot holding above 20% on average at a specific airport or at a combination of airports within the same catchment area, considering that a combined average slot holding below 20% is unlikely to give the Parties the ability to foreclose access to the market for the provision of passenger air transport services. As explained in section 5.1.2.3 below, the only airport where the Parties and the Target Companies would have a combined slot holding above 20% and where the question of airport substitutability would be relevant is Paris Charles de Gaulle airport. Therefore, he Commission will assess whether Paris Charles de Gaulle is substitutable with other airports within the same catchment area.

(139) In the present case, the substitutability from the point of view of passengers of Paris Charles de Gaulle, Paris Orly and Beauvais has already been considered in section 4.1.4.2 above, and the Commission considered that Paris Charles de Gaulle and Paris Orly might be considered as substitutable with respect to the relevant overlap routes but ultimately left the question open.

4.2.2.1.3 Conclusion

(140) For the purpose of its airport-by-airport assessment of the Transaction in this Decision, the Commission will assess the competitive effects of the Transaction on the markets for the provision of passenger air transport services, encompassing all routes to or from an airport, or to or from substitutable airports.

(141) For the purpose of its airport-by-airport assessment of the Transaction in this Decision, the question of whether the relevant geographic market consists of flights to/from Paris Charles de Gaulle only or Paris Charles de Gaulle and Paris Orly can be left open, as the Transaction would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under either plausible market definition (see section 5.1.2. below).

4.2.2.2 Airport infrastructure services

(142) For the purpose of providing passenger air transport services at congested airports, airlines have to source infrastructure services at those airports. As indicated in section 4.2.1.1 above, at congested airports, infrastructure capacity is managed through the allocation of slots, which enable air carriers to fly to and from the airports. A slot is therefore defined, from the point of view of airports, as “a planning tool for rationing capacity at airports where demand for air travel exceeds the available runway and terminal capacity.” (120) From the point of view of airlines, the granting of a slot at an airport means that the airline may use the entire range of infrastructure necessary for the operation of a flight at a given time (runway, taxiway, stands and, for passenger flights, terminal infrastructure). This in turn enables the airlines to provide passenger air transport services to and from that airport.

(143) As a consequence, through the Transaction and the combination of slot portfolios, the Parties together obtain a right of access to a higher share of airport infrastructure capacity. The Transaction therefore has an impact on (the demand- side of) the markets for airport infrastructure services at the relevant airports and also on the markets for passenger air transport to and from those airports.

(144) In addition, Stobart Aviation is active in the provision of airport infrastructure services. Stobart Aviation owns (i) London Southend airport (“SEN”), (ii) Carlisle Lake District airport (“Carlisle”) and (iii) a minority controlling stake in Durham Tees Valley airport (“DTVA”). (121) The Transaction could therefore give rise to vertical links between Stobart Aviation’s activities in the upstream market for airport infrastructure services and the activities of Flybe in the downstream market for the provision of passenger air transport services.

4.2.2.2.1 Relevant product market

(145) The Commission has, in its prior decisional practice, delineated a product market for the provision of airport infrastructure services to airlines, which includes the development, maintenance, use and provision of the runway facilities, taxiways and other airport infrastructure. (122)

(146) In cases where the Transaction could give rise to horizontal overlaps, the Commission has considered sub-dividing the market for airport infrastructure services on the basis of airline customers (i.e. charter operators, scheduled full service carriers and scheduled low cost carriers) and on the basis of the type of flights (i.e. short-haul and long-haul). (123)

(147) In prior decisions relating to the transfer of slots at airports, the Commission has not considered it appropriate to further distinguish within the market for airport infrastructure services, considering that slot portfolios give access to all infrastructure services necessary to operate at the airport. The Commission considers that there is no element in the file that would require deviating from the Commission’s past practice for the purposes of this Decision with respect to the assessment of the effects of the Transaction on passenger air transport under the airport-by-airport approach.

(148) In prior decisions where the transaction could give rise to vertical links, the Commission has not considered it appropriate to further distinguish within the market for airport infrastructure services, considering that slot portfolios give access to all infrastructure services necessary to operate at the airport. (124) The Commission considers that there is no element in the file that would require deviating from the Commission’s past practice for the purposes of this Decision with respect to the assessment of the vertical effects of the Transaction. (125)

4.2.2.2.2 Relevant geographic market

(149) In its prior decisional practice, the Commission has, defined the geographic scope of the market for airport infrastructure services as the catchment area of individual airports.

(150) The Commission has also considered additional criteria relevant for assessing airport substitutability in relation to the market for airport infrastructure services, while acknowledging that the airlines’ choice of airports ultimately depends on passengers’ demand. In addition to the catchment area of a particular airport, the Commission has notably analysed the capacity constraints for slots and facilities, passenger volumes or the positioning of the airport (e.g. a niche airport serving high yield time-sensitive passengers or an airport serving mainly leisure, less time- sensitive passengers). (126)

(151) The Commission has taken account of all the above-mentioned criteria when assessing the geographic scope of the airport infrastructure services markets relevant for the assessment of the effects of transfer of slots. (127)

(152) The question of the exact geographic market definition is relevant (i) for the assessment of the effects of the Transaction on passenger air transport services under the airport-by-airport approach and (ii) for the assessment of the potential vertical links between Stobart Aviation and Flybe.

Relevant geographic market for the assessment of the effects of transport of slots on the access to airport infrastructure services

(153) For the purpose of the assessment of the effects of the Transaction on the market for passenger air transport under the airport-by-airport approach, with respect to the overlap airports where the question of a broader geographic scope encompassing several airports might be relevant, the Commission will focus its assessment of airport substitutability on markets where the Parties would have a slot holding above 20% on average at a specific airport or at a combination of airports within the same catchment area. The Commission considers that a combined average slot holding below 20% is unlikely to give the Parties the ability to foreclose access to the market for airport infrastructure services. As explained in section 5.1.2 below, the only airport where Parties would have a combined slot holding above 20% and where the question of airport substitutability would be relevant is Paris Charles de Gaulle airport. Therefore the Commission will assess whether Paris Charles de Gaulle is substitutable with other airports within the same catchment area.

(154) According to the Parties, Paris Charles de Gaulle (CDG), Paris Orly (ORY) and Beauvais (BVA) airports belong to the same geographic market with respect to airport infrastructure services. (128)

(155) The city of Paris is served by three airports, namely CDG, ORY and BVA.

(156) Delta, AFKL and Flybe hold slots at CDG. AFKL also holds slot at ORY. The Transaction therefore gives rise to an overlap between AFKL/Virgin Atlantic and Flybe at CDG and on a broader geographic scope comprising at least (i) CDG and (ii) ORY and/or BVA. However, BVA is neither a Level 2 or Level 3 airport and is therefore not slot constrained. Its positioning differs from CDG and ORY. BVA focuses on short-haul and is mainly used by low-cost carriers. (129) The Commission will therefore focus its assessment on whether CDG and ORY belongs to the same geographic market with respect to airport infrastructure services. In any event, given that the Parties do not hold slots at BVA, taking account of BVA would only dilute the Parties’ combined slot holding and the increment brought about by the Transaction.

(157) The question of the catchment area of Paris airports is addressed in section 4.1.4.2 above. From the point of view of passengers, CDG and ORY might be considered as substitutable with respect to certain routes. (130)

(158) As regards capacity constraints, both CDG and ORY are coordinated (Level 3) airports in both IATA Seasons.

(159) In 2018, 72.2 million passengers used Paris Charles de Gaulle airport (131), while 33.1 million passengers used Paris Orly airport. (132)

(160) As regards positioning, CDG is the largest international airport in France in terms of passenger traffic. CDG is served by more than 60 passenger and cargo airlines, which mainly focus on international long-haul flights. (133) In Summer 2018, direct flights were offered to 318 destinations (134) and 90% of flights were to international destinations. (135) Based on data from ADP, approximately 13% of the traffic at CDG was operated by low-cost carriers. (136)

(161) ORY is the second largest airport in France in terms of passenger traffic. ORY is served by 35 airlines which operate primarily to short-haul destinations in mainland France, Europe, North Africa and the French Overseas Territories. (137) In Summer 2018, direct flights were offered to 139 destinations (138) and 59% of flights were to international destinations. (139) In 2017, approximately 38% of the traffic was operated by low-cost airlines. (140)

(162) Considering that Paris Charles de Gaulle and Paris Orly have different positioning and strategy, the Commission concludes that, for the purpose of the assessment of the effects of the Transaction on passenger air transport services under the airport-by-airport approach, the geographic scope of the market for the provision of airport infrastructure services to airlines is limited to Paris Charles de Gaulle airport. (141)

Relevant geographic market for the assessment of the vertical effects created by the Transaction

(163) Considering that Stobart Aviation is active in the market for the provision of airport infrastructure services at several airports in the United Kingdom, the Commission will assess the geographic scope of airport infrastructure services for London Southend (SEN) airport and DTVA airport. (142)

(164) The question of the catchment area of London airports is addressed in section 4.1.4.2 above. From the point of view of passengers, the relevant markets consists of flights to/from London Heathrow only, or to/from Heathrow, Gatwick and City airports (“London(three)”), or Heathrow, Gatwick, City, Luton, Stansted and Southend (“London(six)”). As regards capacity constraints, LHR, LGW, LCY, LTN and STN are coordinated (Level 3) airports while SEN is neither schedules facilitated nor coordinated. The question whether airport infrastructure services at SEN constitute a separate market or whether airport infrastructure services should be considered for London(six) airports can be left open, because the Transaction would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible geographic market definition.

(165) With respect to the geographic scope of the provision of airport infrastructure services in the Tees Valley (UK), the Parties submit that the geographic scope comprises DTVA, Leeds airport (“LBA”) and Newcastle airport (“NCL”). (143) The three airports are within 100 km of Middlesbrough city, the closest city centre to DTVA. The results of the market investigation are inconclusive as to whether DTVA, LBA and NCL belongs to the same market. (144) The Commission considers that the question whether the market for the provision of airport infrastructure services consists in DTVA only or encompasses DTVA, LBA and NCL can be left open because the Transaction would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market, under any plausible geographic market definition.

4.2.2.2.3 Conclusion

(166) For the purpose of the assessment of the effects of the Transaction on passenger air transport services under the airport-by-airport approach, the Commission will assess the effects of the Transaction on the market for the provision of airport infrastructure services to airlines, without further delineation. Similarly, for the purpose of assessing the vertical links created between Stobart Aviation and Flybe, the Commission will assess the effects of the Transaction on the market for the provision of airport infrastructure services to airlines, without further delineation.

(167) For the purpose of the assessment of the effects of the Transaction on passenger air transport services under the airport-by-airport approach, the Commission considers that the geographic scope of the market for airport infrastructures services is limited to the individual airport with respect to airport infrastructure services at Paris Charles de Gaulle airport. Considering that the Transaction would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market with respect to passenger air transport under the airport-by-airport approach, the question of the exact geographic market for airport infrastructure at the overlap airports can be left open. For the purpose of assessing the vertical links created between Stobart Aviation and Flybe, the Commission will assess the vertical effects under every plausible geographic market definition given that the exact geographic market definition can be left open with respect to airport infrastructure services at SEN and DTVA.

4.3 Market for the provision of access to flights of another carrier for connecting passengers in the context of interlining arrangements

4.3.1 Relevance of feeder traffic analysis

(168) Passengers travelling on indirect flights, in particular for long-haul flights, connect from one flight to the other flight at a certain airport. These passengers do not necessarily travel each “leg” of their journey with the same airline. Traffic made up by passengers connecting at either one or both ends of the route, in particular for long haul flights, is referred to as “feeder traffic”. (145)

4.3.1.1 Parties’ views

(169) The Notifying Parties consider that, while the vast majority of Flybe’s activities focus on point-to-point flying, Flybe has entered into a number of interlining and codeshare agreements with third party carriers to enhance connectivity for its customers. (146) According to the Notifying Parties, as a result of the Transaction, the Parties will not have the ability or incentive to foreclose third party long-haul carriers’ access to feeder traffic on any specific route. On the contrary, the rationale for the Transaction is to allow enhanced connectivity for customers to travel to destinations globally. (147)

(170) According to the Notifying Parties, the acquisition will enable Flybe to benefit from committed strategic investment partners in terms of Cyrus, Stobart Aviation and Virgin Atlantic (through Connect Airways) and through linking an enhanced Flybe regional network with Virgin Atlantic’s long-haul operations, increasing feeder traffic, particularly at LHR and MAN. (148)

4.3.1.2 Commission’s assessment

(171) In its prior decision practice, the Commission has analysed if one of the merging airlines has provided competitors with feeder traffic. Such feeder traffic may constitute an essential input for a competitor, the Commission therefore analysed an input foreclosure theory of harm, assessing ability and incentive of the merging parties to engage in input foreclose post-Transaction, as well as the overall likely impact on effective competition of such potential foreclosure. (149)

(172) Flybe has interlining and codeshare agreements with several third party airlines, and provides feeder traffic to those third party airlines’ long-haul flights (including where these third party airlines compete with Virgin Atlanta, Delta or AFKL for the long-haul flights). (150)

(173) For the purpose of the competitive assessment of the Transaction, the Commission will therefore apply the analytical framework designed to address the risk of input foreclosure in relation to feeder traffic resulting from the change of control over Flybe. This theory of harm is assessed in Section 5.1.3 below.

4.3.2 Market definition

4.3.2.1 Parties’ views

(174) The Parties have considered the impact of the Transaction on the market for the provision of access to flights of another carrier for connecting passengers in the context of interlining arrangements, which is defined on an O&D and city-pair basis for each input flight (151), in line with the approach taken by the Commission in previous decisions. (152)

4.3.2.2 Commission’s assessment

(175) “Connecting” or “transfer passengers” are passengers who fly indirectly on a given city-pair (e.g. Dublin-Chicago via London Heathrow). These passengers do not necessarily travel each “leg” or “sector” of their journey on the same carrier (e.g. the carrier who sold them the ticket). In particular for long-haul flights, traffic made up by passengers connecting at either or both ends of the route is commonly referred to as “feeder traffic”.

(176) There is a variety of agreements whereby single tickets may be sold for indirect routes including two legs operated respectively by the two carriers which concluded the agreement. In the framework of such agreements, the carrier granting access to its flights to passengers connecting onto another carrier’s flight and travelling with a single ticket issued by this second carrier provides an “input” to the latter and is remunerated for it. This “input” is used to supply the downstream service, i.e. a ticket for an indirect route on a given city-pair. Two carriers that interline are thus engaged in a vertical relationship when one of them sells tickets for indirect routes including one leg operated by the other carrier. (153)

(177) The main different types of “feeder traffic” or “interlining arrangements” are the following: (154)

a) Interline agreements, which are commercial agreements between airlines to handle passengers travelling on multiple airlines on the same itinerary. These agreements allow one carrier to issue the main itinerary ticket while each carrier is marketing its own sector.

b) Codeshare agreements, which allow one carrier to sell tickets on another carrier’s flight under its own name and flight code, thereby broadening their service offering and destinations.

c) Special Prorate Agreements (“SPAs”), which support interlining and codesharing, and which specifically define the distribution of the revenues and the settlement of ticket costs between carriers.

d) Alliance memberships, which typically entail codesharing (although the actual codeshare agreements are still concluded between two airlines) but which also imply a number of mutual obligations which go beyond those required by codesharing (such as, for example, mutual Frequent Flyer Programme participation (155)).

(178) These agreements are in principle mutually beneficial as they give each party the opportunity to increase its load factors. In principle, they also benefit passengers as they increase connection opportunities, allow passengers to be compensated in case of missed connections and spare them from taking back luggage at the connection airport.

(179) There are cases where both carriers can sell tickets for indirect routes including one leg operated by the other party to the agreement. In such a situation, the vertical relationship is symmetrical: both carriers are active upstream and downstream in respect of one another. There are also cases where the ticket for the indirect route is sold by a third party (e.g. a travel agent).

(180) The carrier or distributor operating the downstream service (in casu long-haul routes) provides passenger air transport services between two cities. The downstream service is the market for the provision of air transport services between these two cities. As assessed above, this market has to be defined on an O&D basis, i.e. by reference to the two cities (or as the case may be, to the two airports) at both ends of the flight itinerary.

(181) The carrier operating the upstream service (carrying the feeder traffic) provides to the downstream carrier access to its flights to one end of the city pair (i.e. the connecting airport). For example, for routes between Manchester and Orlando operated by the downstream carrier, the upstream market concerned for the provision of access to flights for connecting passengers would comprise all routes to and providing feeder traffic at Manchester. Such an upstream market has to be defined as comprising all routes to the connecting airport where the flights carrying the feeder traffic are operated. Indeed, a carrier wanting to supply flights e.g. between Manchester and Orlando may rely on and need as an input access to flights feeding traffic to Manchester. Flights to other cities cannot, in principle, constitute a valid substitute.

4.3.2.3 Conclusion

(182) As a conclusion, the relevant markets for the provision of access to flights from a number of airports in Europe for connecting passengers in the context of interlining arrangements have to be defined on an O&D basis.

4.4 Air transport of cargo

4.4.1.1 Relevant product market

(183) In prior decisions, the Commission considered a market for air transport of cargo including all kinds of transported goods provided by all types of air cargo carriers, (156) without any further subdivision to be made according to the nature of the goods transported (for example, dangerous or perishable goods) or the type of air cargo carrier. (157)

(184) In fact, the Commission has concluded that four types of air cargo carriers, namely (i) cargo airlines with dedicated freighter planes; (ii) airlines with only belly space cargo capacity on passenger flights; (iii) combination airlines (i.e. airlines with both dedicated freighter airplanes and belly space cargo capacity); and (iv) integrators, compete with each other for business with the same kinds of customers. (158)

(185) Based on the Commission’s prior decisions, the O&D approach to market definition is not appropriate for air cargo transport services because cargo is (i) in principle less time-sensitive than passengers, and (ii) usually transported “behind” and “beyond” the points of origin and destination by trans-modal transport methods and thus can be routed via a higher number of stops than passengers. (159) Consequently, the Commission considers that a wider market for air transport of cargo exists as, unlike passengers, cargo can be transported with a higher number of stopovers and therefore any one-stop route is a substitute for any non-stop route. (160) In addition, as established in previous Commission decisions, air cargo transport markets are inherently unidirectional due to differences in demand at each end of the route and must hence be assessed on a unidirectional basis. (161)

(186) The Parties agree with the Commission’s decision-making practice. (162)

(187) In line with its prior decisional practice, the Commission will assess the effects of the Transaction on a broader market for air transport of cargo encompassing all types of air cargo carriers and including all kinds of transported goods on a unidirectional basis in Section 5.5 below.

4.4.1.2 Relevant geographic market

(188) In prior decisions, the Commission defined the market in intra-European routes of air cargo transport as European-wide. (163) As regards intercontinental routes, the Commission established that catchment areas at each end of the route broadly correspond to continents where local infrastructure is adequate to allow for onward connections (for example, by road, train, or inland waterways, etc.), such as Europe and North America. As regards continents where local infrastructure is less developed, the relevant catchment area has been considered the country of destination. (164)

(189) The Parties consider that the Commission’s previous finding of unidirectional markets defined on a continent-to-continent basis (or country basis, where connecting transport infrastructure is less developed) is still appropriate. (165)

(190) Therefore, in line with its prior decisional practice, the Commission will assess the effects of the Transaction on a continent-to-continent basis (or continent-to country basis as the case may be), in particular on an EEA-wide (intra-European) basis.

4.4.1.3 Conclusion

(191) Therefore, in line with its prior decisional practice, the Commission will assess the effects of the Transaction on an EEA-wide market for air transport of cargo encompassing all types of air cargo carriers and including all kinds of transported goods on a unidirectional basis.

4.5 Maintenance, repair and overhaul (“MRO”) services

4.5.1.1 Relevant product market

(192) In prior decisions, the Commission distinguished four separate segments within the MRO market based on the part of the aircraft to be serviced and the level of service required, namely (i) line maintenance (minor checks carried out on aircraft and performed at the different airports), (ii) heavy maintenance (comprehensive inspection and overhaul of the aircraft, for which the aircraft is taken out of service), (iii) engine maintenance, and (iv) components maintenance (inspection, repair and overhaul of specific aircraft components). (166) The Commission also considered but ultimately left the question open, whether a distinction between commercial and business aviation is appropriate. (167) It moreover noted that line maintenance and heavy maintenance can be further subdivided according to nature and frequency of the checks involved (A, B, C and D-checks). (168)

(193) The Parties submit that the precise scope of the product market definition for MRO can be left open as no serious doubts would arise under any plausible market definition. (169) However, in line with the Commission’s decisional practice, they provided data for each of the following MRO segments (i) line maintenance; (ii) heavy maintenance; (ii) engine maintenance; and (iv) components maintenance.

(194) In light of the above, the Commission concludes that the precise scope of the product market definition for MRO services can be left open since the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible product market definition, as assessed in Section 5.6 below.

4.5.1.2 Relevant geographic market

(195) In prior decisions, the Commission considered that the geographic scope of the market for heavy maintenance services might be at least EEA-wide, whereas line maintenance services could be local in scope and even limited to the airport where services are provided. (170) Indeed, line maintenance services are usually carried out at the airport of origin or destination, or at the aircraft’s operational base. (171) As regards to engine maintenance services and components maintenance services, the Commission has considered these services to be worldwide in scope. (172)

(196) The Parties submit that the precise scope of the geographic market definition for MRO can be left open as no serious doubts would arise under any plausible market definition. (173)

(197) For the assessment of the Transaction, the Commission concludes that the precise geographic market definition for MRO services can be left open, since the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible geographic market definition, as assessed in Section 5.6 below.

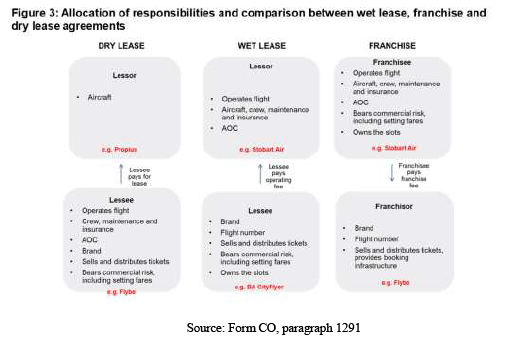

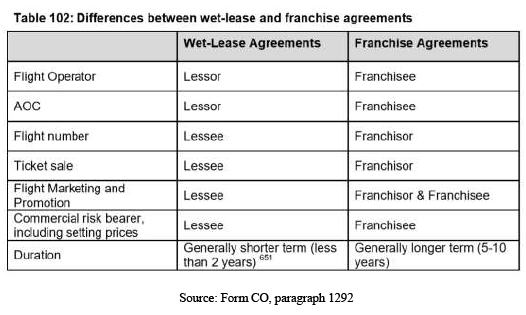

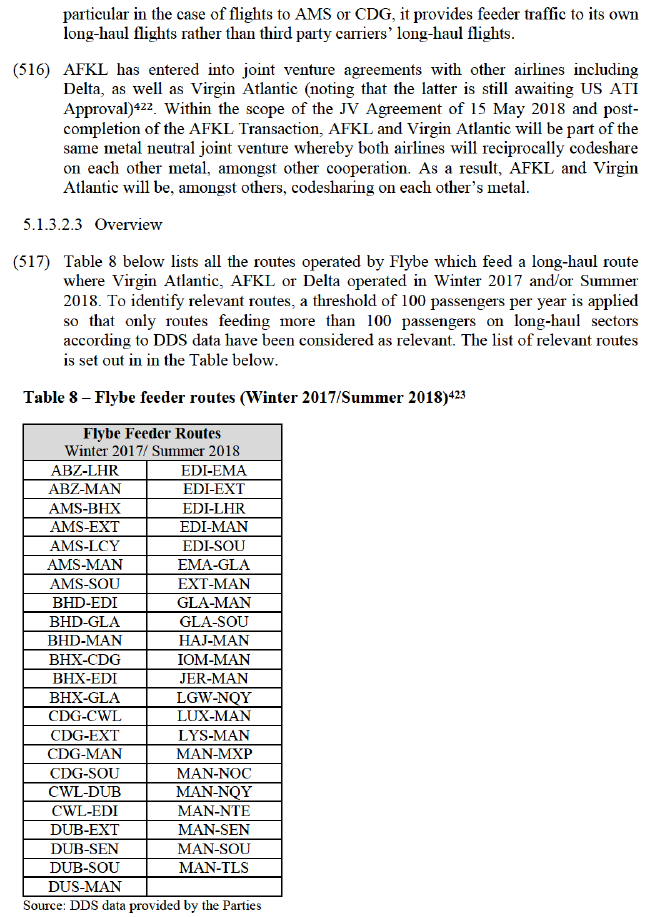

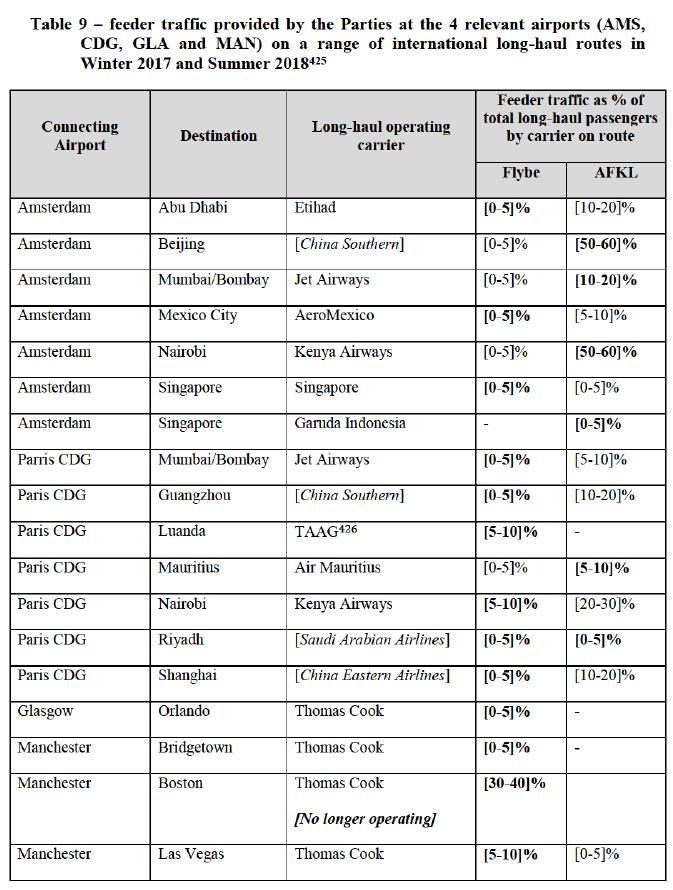

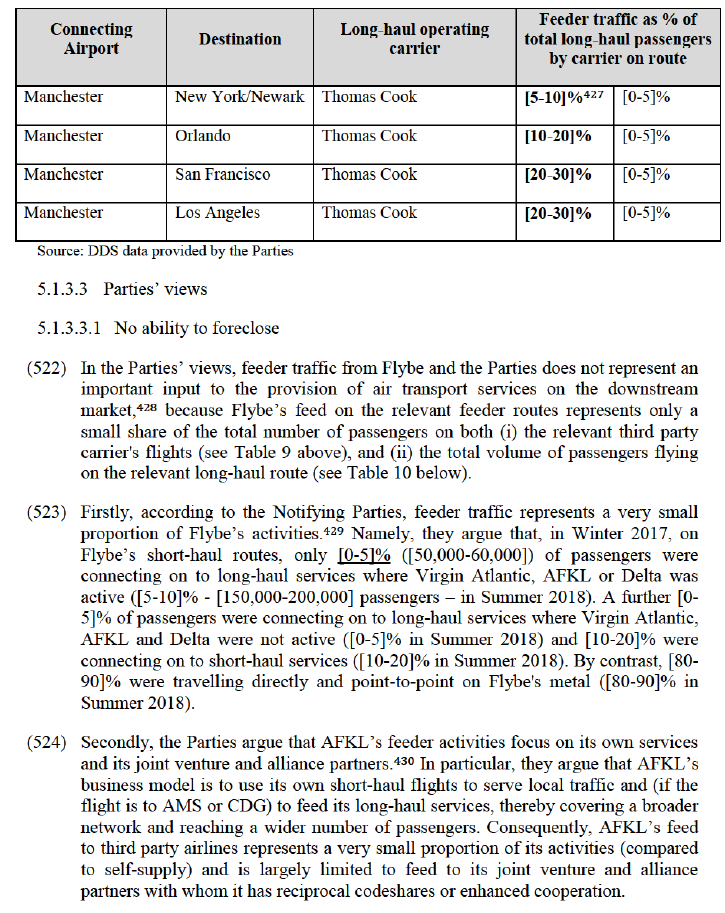

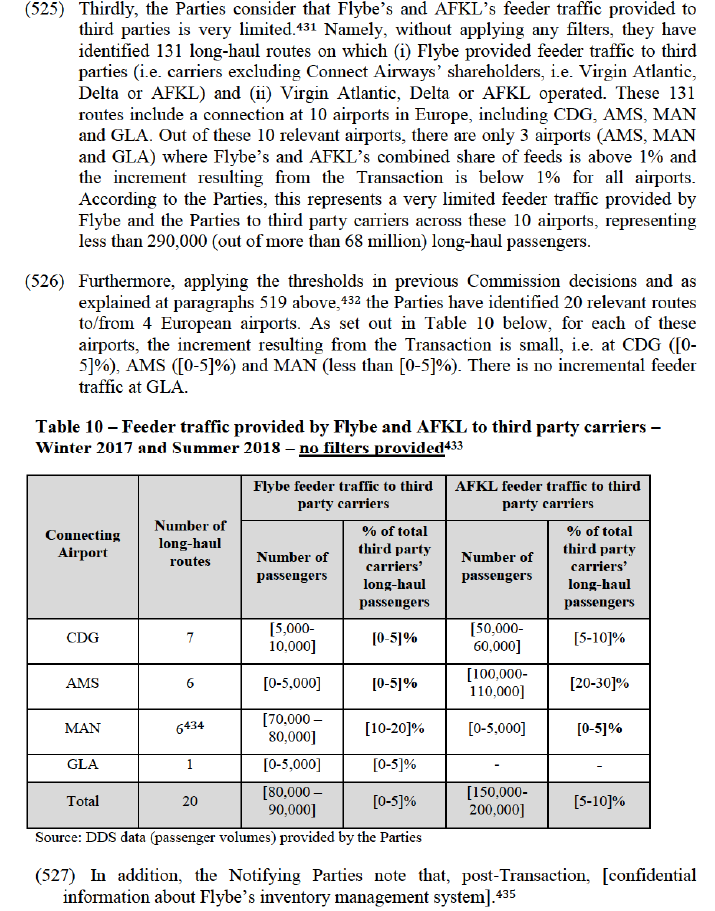

4.6 Dry-leasing, wet-leasing and franchise services to other airlines