Commission, May 7, 2018, No M.8444

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

ArcelorMittal/Ilva

COMMISSION DECISION of 7.5.2018

declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the EEA agreement

(Case M.8444 – ArcelorMittal/Ilva)

(Text with EEA relevance) (Only the English text is authentic)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area, and in particular Article 57 thereof,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (1), and in particular Article 8(2) thereof,

Having regard to the Commission's decision of 8 November 2017 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given the undertakings concerned the opportunity to make known their views on the objections raised by the Commission,

Having regard to the opinion of the Advisory Committee on Concentrations (2), Having regard to the final report of the Hearing Officer in this case (3), Whereas:

(1) On 21 September 2017 the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (the ‘Merger Regulation’) by which ArcelorMittal S.A. (‘ArcelorMittal’, ‘AM’, or the ‘Notifying Party’) acquires sole control of certain assets of the Ilva Group: namely the business of Ilva S.p.A and a number of its subsidiaries, namely Ilva S.p.A, Taranto Energia S.r.l, Ilva Servizi Marittimi S.p.A, Tillet S.a.s and Socova S.a.s. (‘the Transaction’). (4)

1. THE PARTIES

(2) ArcelorMittal S.A (‘ArcelorMittal’) is based in Luxembourg and is the largest steel producer in the world. It is a multinational steel manufacturing and mining company, whose principal business is the production, distribution, marketing and sale of steel products for various applications, including automotive, construction, household appliances and packaging.

(3) The Ilva Group, which includes Ilva S.p.A. (‘Ilva’), is based in Italy. One of Europe's largest steelmakers, it is active in the production, processing and distribution of carbon steel. Ilva operates steel plants in Italy (including plants in Taranto, Genoa, and Novi Ligure) and various steel service centres (‘SSCs’) for product distribution.

1.1. The Ilva assets

(4) The Transaction does not involve the acquisition of the entire Ilva Group, but is limited to certain business units which belong to the following entities of the Ilva Group: (1) Ilva S.p.A. and a number of its subsidiaries, which are all in extraordinary administration (Amministrazione Straordinaria), namely – (2) Ilvaform S.p.A;

(3) Taranto energia S.r.l; (4) Ilva Servizi Marittimi S.p.A; (5) Tillet S.a.S.; and

(6) Socova S.a.S. Those business units consist most notably of Ilva's plants in Taranto, Genova and Novi Ligure, its steel service centres in Salerno (Italy) and Sénas (France), Ilva's maritime fleet, the power station operating the Taranto plant and certain distribution outlets in Italy and France.

(5) According to the information provided by the Notifying Party, the Transaction covers only the assets of those companies and there would be no legal succession of those entities. The assets of the Ilva Group that are subject to the Transaction are hereinafter referred to as ‘the Ilva assets’, while the Ilva Group as a competitor of ArcelorMittal prior to the transaction will be referred to as ‘Ilva’.

(6) Figure 1 shows the structure of the Ilva Group which is currently under extraordinary administration and the Ilva assets within the perimeter of the Transaction.

Figure 1 – [Internal document] (5)

[…]

(7) For the purpose of this Decision, ArcelorMittal and the Ilva are hereinafter jointly referred to as ‘the Parties’ while ArcelorMittal is referred to as ‘the Notifying Party’.

2. THE OPERATION AND THE CONCENTRATION

(8) Ilva Group has been owned by the Riva Group since 1996 and was previously controlled by the Italian State through IRI – Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale. It entered into insolvency proceedings (Amministrazione Straordinaria) in March 2015. Since then, Ilva has been run by three government-appointed extraordinary commissioners.

(9) In January 2016, the Italian Government, as part of the special insolvency proceedings, launched a competitive tender for the sale of the Ilva assets. ArcelorMittal submitted a binding offer to acquire the Ilva assets on 6 March 2017 through AM InvestCo Italy S.r.l. (‘AM Consortium’), a solely-controlled subsidiary of ArcelorMittal, of which ArcelorMittal currently owns […]%. (6) The remaining […]% is held by Marcegaglia Carbon Steel S.p.A (‘Marcegaglia’), an Italian steel company which is both a competitor of and one of the largest customers of Ilva. […], at the closing of the Transaction, ArcelorMittal would own approximately […]% of AM Consortium, while Marcegaglia and Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. (an Italian bank and one of Ilva Group’s creditors) would each own small shareholdings of circa […]%, neither of which will confer joint control over the Ilva assets. (7)

(10) As a result of the Transaction, ArcelorMittal would have sole control of the Ilva assets.

(11) The Transaction constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

3. UNION DIMENSION

(12) The Transaction has a Union dimension as the turnover thresholds set out in Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation are met. The combined aggregate worldwide turnover of the Parties is more than EUR 5 000 million (ArcelorMittal EUR 51 306 million, the Ilva assets EUR […] million) (8) and the aggregate Union-wide turnover of each of the Parties is more than EUR 250 million (ArcelorMittal EUR […] million, the Ilva assets EUR […] million). Neither ArcelorMittal nor the Ilva assets achieve more than two-thirds of their Union-wide turnover within one and the same Union Member State.

(13) The notified operation therefore has a Union dimension.

4. THE PROCEDURE

4.1. The administrative procedure

(14) During the Phase I investigation, the Commission contacted a number of market participants (including customers and competitors of the Parties) and requested information both through seven electronic questionnaires pursuant to Article 11 of the Merger Regulation and telephone calls.

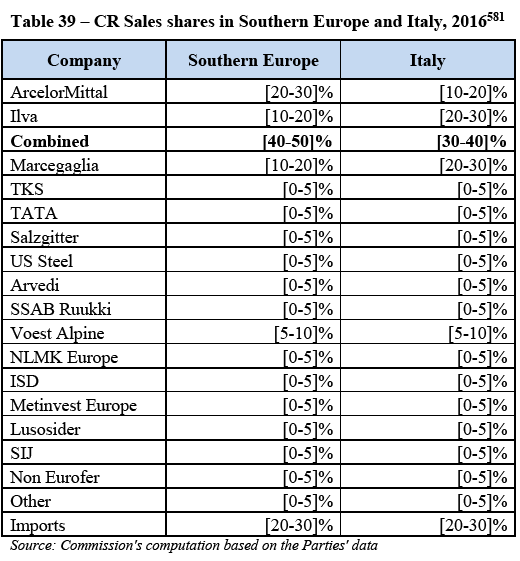

(15) On 12 October 2016, the Commission informed the Parties of the concerns resulting from the preliminary assessment of the Transaction during a 'State of Play' meeting.

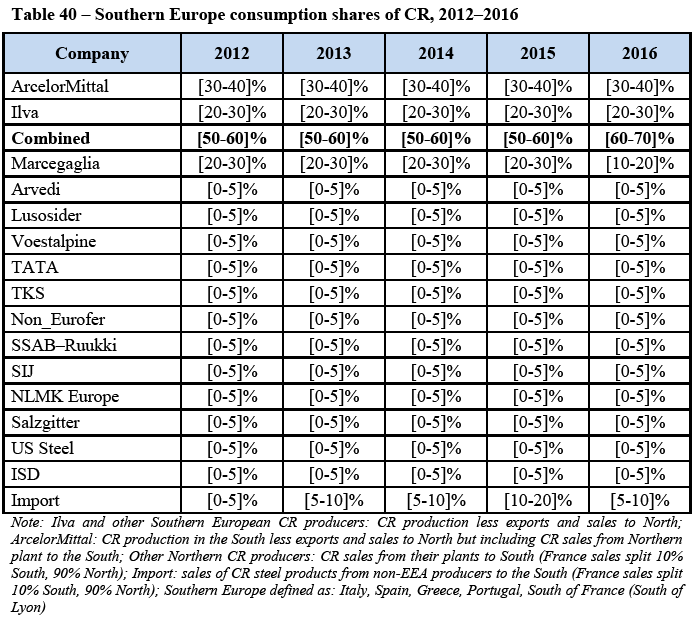

(16) On 19 October 2017, the Parties submitted commitments that included the divestment of [Parties' submissions]. Those commitments were not market tested.

(17) Based on the results of the Phase I market investigation, the Commission found that the Transaction raised serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market and adopted a decision to initiate proceedings pursuant to Article 6(1)(c) of the Merger Regulation on 8 November 2017 (the 'Article 6(1)(c) decision').

(18) On 10 November 2017, the Commission provided a number of key documents illustrating the nature of the case to the Notifying Party.

(19) On 18 November 2017 ArcelorMittal submitted to the Commission its comments in response to the Article 6(1)(c) decision, a revised version of which was submitted on 19 November 2017.

(20) On 22 November 2017, at a state of play meeting, the Commission provided the Parties with the opportunity to discuss orally the main issues raised in the response to the Article 6(1)(c) decision and indicated the matters on which it planned to focus its further investigative efforts.

(21) During the Phase II market investigation, the Commission sent several requests for information to the Parties, as well as to third parties. The Commission held several calls with market participants, and also sent requests for information in the form of three questionnaires, in addition to the seven questionnaires sent out before the initiation of the proceedings, to a total of more than 1800 addressees. Furthermore, the Commission analysed internal documents of the Parties.

(22) On 15 December 2017, in agreement with the Notifying Party, the Commission decided to extend the time period set out in the first subparagraphs of Article 10(3) of the Merger Regulation by a total of five working days in accordance with the third sentence of the second subparagraph of Article 10(3) of the Merger Regulation.

(23) Following the results of the Phase II market investigation, a state of play meeting was held on 16 January 2017, in order to inform the Notifying Party of the preliminary results of the Phase II market investigation and the scope of the preliminary concerns on which the Commission planned to issue a Statement of Objections.

(24) On 18 January 2018, the Commission adopted a Statement of Objections (‘SO’), which was sent to the Notifying Party on the same day. According to the SO, the Commission came to the preliminary view that the Transaction would significantly impede effective competition in a substantial part of the internal market within the meaning of Article 2 of the Merger Regulation due to (i) horizontal non-coordinated effects in the markets for the production and supply of hot rolled flat carbon steel, cold rolled steel, hot dip galvanised steel and electro galvanised steel products in the EEA; and (ii) horizontal coordinated effects in a number of markets for flat carbon steel in the EEA. The Commission's preliminary conclusion was therefore that the notified concentration would be incompatible with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement.

(25) The Notifying Party was granted access to the file on 19 January 2018 via CD-ROM. A data room was organised from 19 January to 29 January 2018 allowing the economic advisors of ArcelorMittal to verify confidential information of a quantitative nature, which formed part of the Commission's file. Further documents were sent on 24 January, 1 February, 2 March, 26 March, 28 March and 26 April 2018. A second data room was organised from 1 March to 2 March 2018.

(26) The Ilva Group submitted its observations to the SO on 1 February 2018.

(27) ArcelorMittal was given until 2 February 2018 to reply to the SO and eventually submitted its reply on the morning of 3 February 2018 (the 'Reply to the SO').

(28) Both ArcelorMittal and the Ilva Group requested to be heard orally.

(29) ThyssenKrupp AG, Tata Steel Limited and Marcegaglia made applications to the Hearing Officer to be admitted as interested third persons in the proceedings.

(30) All interested third persons were provided with a non-confidential version of the SO and given a time-limit within which to submit their responses. Given the urgency of the proceedings, ThyssenKrupp AG, Tata Steel Limited and Marcegaglia were allowed to make known their views at the oral hearing prior to the submission of their written comments pursuant to Article 16(2) of Commission Regulation (EC) 802/2004 (9).

(31) An oral hearing was held on 8 February 2018.

(32) On 22 February 2018, in accordance with the third sentence of the second subparagraph of Article 10(3) of the Merger Regulation and in agreement with the Notifying Party, the Commission decided to extend the time period set out in the first subparagraph of Article 10(3) of the Merger Regulation by a total of 11 working days. This decision was taken to allow the Commission and the Parties to have sufficient time to discuss and thoroughly assess any remedy proposal that may be submitted by the Notifying Party. Accordingly, the deadline for a Commission decision in this proceeding was extended until 19 April 2018.

(33) A Letter of Facts – evidence corroborating the objections set out in the SO – was sent to the Notifying Party on 28 February 2018. The Notifying Party submitted its comments on the Letter of Facts on 9 March 2018 ('Reply to the Letter of Facts').

(34) The Notifying Party was then granted further access to the file on 2 March 2018 via CD-ROM. A data room was organised from 1 March to 2 March 2018.

(35) On 5 March and 11 March 2018, the Notifying Party submitted draft commitments in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO. Consequently, on 12 March 2018, the period for the adoption of a final Decision was extended by 4 working days pursuant to Article 10(3) second subparagraph, third sentence of the Merger Regulation to allow for the Commission and the Parties to have sufficient time to discuss and thoroughly assess any formal remedy proposal that may be submitted by the Notifying Party. Accordingly on 12 March 2018, the deadline for a Commission decision in this proceeding was extended until 25 April 2018.

(36) On 15 March 2018, the Notifying Party submitted commitments pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO (the 'Commitments of 15 March 2018').

(37) On 15 March 2018, the Commission launched a market test of the Commitments of 15 March 2018.

(38) The Notifying Party was then granted further access to the file on 28 March 2018 via email.

(39) On 11 April 2018, the Notifying Party submitted a final set of commitments (the 'Final Commitments').

(40) The meeting of the Advisory Committee took place on 2 May 2018.

(41) The Hearing Officer issued his final report on 3 May 2018.

4.2. Considerations regarding the reliability of the replies to the Commission's market investigation

4.2.1.Introduction

(42) As outlined in Section 4.2.3, in the course of its investigation, the Commission found evidence that the Notifying Party had reached out to certain customers of Ilva to discuss their responses to the Commission's investigation. The Commission set out this evidence in the SO and noted that while it may further investigate the issue, it would take account of the fact that such interactions between the Notifying Party and its customers may affect the reliability of the customers' replies to the questionnaires.

4.2.2. The Notifying Party's views

(43) According to the Notifying Party, the SO points to a limited set of documents that describe ArcelorMittal's outreach to inform key customers about the Transaction, answer questions that customers might have about the implications of the Transaction for their business and explain the benefits ArcelorMittal considers the Transaction would bring to their customers. In this regard, the Notifying Party submits that the following points bear mention:

(1) According to the Notifying Party, customer outreach is a normal and legitimate business practice during significant M&A activity.

(2) According to the Notifying Party, there is no evidence that ArcelorMittal sought to influence responses to the Commission’s market investigation. Rather, according to the Notifying Party, the documents cited show a legitimate and normal customer communications plan, and a ‘very limited’ exercise in canvassing feedback from a small number of Italian customers where three topics were discussed: [internal document]. According to the Notifying Party that limited exercise was informative in nature and there is no evidence of any attempt to influence those customers future replies (either explicit or implicit).

(3) Further, according to the Notifying Party, the responses to the Commission’s market investigation confirm that ArcelorMittal did not seek to influence responses.

(4) Finally, the Notifying Party submits that there is no basis in statute or precedent to warrant further ‘investigation’ on this issue, as the SO suggests and none of the issues summarised above justify a departure from the Commission's obligation to take all relevant evidence into account, including customer support for the Transaction when reaching a decision under the Merger Regulation. In this regard, the Notifying Party submits that the results of the Commission's market investigation were markedly more supportive of the Transaction than the SO suggests and that it is incumbent on the Commission to take into account all relevant evidence in an even handed fashion.(10)

4.2.3. The Commission's assessment

(44) The Commission takes due note of the arguments of the Notifying Party (see Section 4.2.2) and the case law quoted by the Notifying Party in its response to the SO. In this regard, the Commission notes that in ABB Asea Brown Boveri v Commission, (11) the Court held that ‘[t]he guarantees conferred by the Community legal order in administrative proceedings include, in particular, the duty of the competent institution to examine carefully and impartially all the relevant aspects of the individual case.’ In this regard, the Commission also notes that in that case the Court rejected the plea alleging infringement of the principle of sound administration given, inter alia, that the allegations in question were in fact supported by the evidence gathered by the Commission.

(45) As regards the Commission's investigation in this case, as outlined in the SO, the Commission found documentary evidence that the Notifying Party initiated contacts and held discussions with certain customers of the Ilva Group concerning their responses to the Commission's investigation, as further detailed in the following paragraphs.

(46) As acknowledged by the Notifying Party, ArcelorMittal pursued a customer communication plan to discuss the Transaction, which included customer events, personal visits, and letters. (12) In this framework, […]. (13)

(47) In a summary document, […]. (14)

(48) This behaviour is also demonstrated by […]: […] (15)

(49) On the basis of the evidence quoted in this Section, the Commission considers that the intention of such exchanges went beyond ArcelorMittal's ‘interest in communicating and explaining to individual customers what it considers to be the benefits of the Transaction for customers, to answer questions, and dispel possible misunderstandings.’ (16) Rather, as indicated more particularly in the email cited in recital (48), there was clearly an intention to influence the outcome of the market investigation in favour of the Transaction. The exchanges with customers concerned [internal document]. Considering its obligation ‘to examine carefully and impartially all the relevant aspects of the individual case’ (17), the Commission finds that these interactions likely affect the reliability of replies to questionnaires in the second phase of the investigation, particularly where they concern opinions about the Transaction as opposed to the transmission of factual information. The Commission has taken this into account when assessing individual replies to the market investigation.

5. INTRODUCTION TO THE FLAT CARBON STEEL INDUSTRY

5.1. Value chain and production process of flat carbon steel

5.1.1. Production process of flat carbon steel

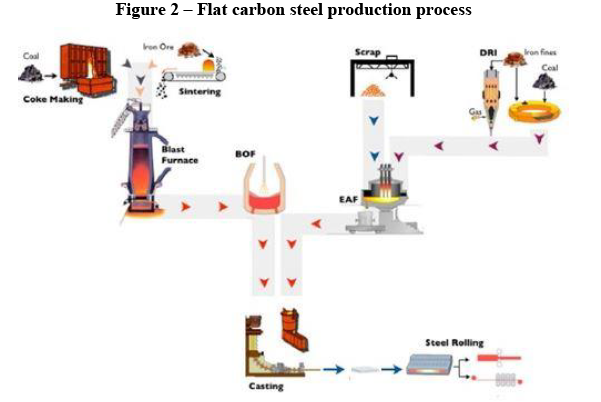

(50) Carbon steel is based on iron and carbon and it contains little or no alloying elements. (18) Carbon steel production consists of two main stages: (i) the production of crude steel and semi-finished products, and (ii) the production of final products.

(51) There are two principal processes for the production of crude steel and semi-finished products: (i) the so-called integrated or blast furnace (‘BF’)/basic oxygen furnace (‘BOF’) route and (ii) the electric arc furnace (‘EAF’) route. Both methods involve the production or use of an iron-containing material – liquid hot metal (liquid carbon-saturated iron), pig iron (solid carbon-saturated iron), direct reduced iron (‘DRI’) or scrap.

(52) The integrated route involves the production of liquid hot metal from a mixture of iron ore, coke and limestone in a blast furnace. The liquid hot metal, which has a high carbon content and would thus be brittle in its solid state (pig iron) is refined into steel in a basic oxygen furnace (‘BOF’) where also scrap may be added. (19) In the BOF process, the carbon content of the liquid metal is reduced by blowing oxygen into it; the oxygen combines with carbon to form gaseous compounds that leave the liquid thereby reducing its carbon content. During the BOF process, or in a separate secondary steelmaking, the composition of the steel is adjusted to give it the desired qualities. The adjustment may include the use of appropriate quantities of various alloying elements.

(53) The EAF route involves melting of scrap into liquid steel in a special furnace, sometimes together with pig iron or DRI. During this process, or in a separate secondary steelmaking, the composition of the steel is adjusted to give it the desired qualities. The adjustment may include the use of appropriate quantities of various alloying elements.

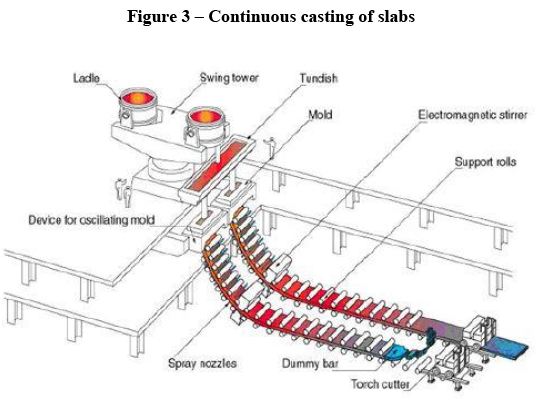

(54) Once the liquid steel has been produced – be it through the integrated or EAF route, it is cast and cooled in continuous casting machines to produce semi-finished carbon steel products. There are three main types of semi-finished carbon steel: slabs, blooms and billets. Slabs are used in the production of finished flat products while blooms and billets are used in the production of finished long products. As the Transaction only concerns flat products, the production process of long products is not discussed further in this Decision.

(55) To produce finished flat carbon steel products, the slabs are cooled and transported to a hot rolling mill either on-site or at another location for further processing into thinner, usable plates or strips. In the hot rolling mill the slabs are reheated to a desired temperature in a reheat furnace and subsequently rolled into different thicknesses through a series of stands. There are two main types of hot rolling mills: plate mills that produce quarto plates in a special four stand mill and strip mills that produce hot rolled strips that are thinner than quarto plates and that can be coiled after rolling.

(56) If required, hot rolled coils can be further rolled down to thinner gauges (and better surface quality) in cold rolling mills. Finally, the cold rolled (and sometimes hot rolled) coils can also be coated with thin layers of metals or organic materials, resulting for instance in galvanised or organic coated products, among others.

(57) The production process for flat carbon steel products is illustrated in Figure 2.

5.1.2. Description of flat carbon steel products and their distribution

5.1.2.1. Semi-finished products

(58) The semi-finished carbon steel products used as input in the finished flat product production are slabs. Slabs are typically produced from the hot liquid steel at the steel shop through continuous casting. Continuous casting starts as the molten metal is transported from the basic oxygen furnace or an electric arc furnace in a ladle and poured into a tundish which provides for a reservoir of liquid steel for the casting process. In the casting, the liquid steel is continuously cast through a mould to form the desired width and thickness of the slab, which is eventually cut into usable lengths at the end of the process. The continuous casting process is illustrated in Figure 3.

5.1.2.2. Quarto plates

(59) Quarto plates (‘QP’) are non-coiled hot rolled flat carbon steel products that are produced in dedicated plate mills after reheating the slabs to the desired temperature in reheat furnaces. QP differ from other hot rolled flat carbon steel products in their dimensions, being in particular thicker than strip products. They are used in applications that call for thick steel, such as at shipyards, boiler-making, nuclear and the oil & gas industry.

5.1.2.3. Hot rolled products (excluding QP)

(60) Hot rolled flat carbon steel products other than quarto plates (‘HR’) are strip products that are produced from slabs through hot rolling in a strip mill after reheating the slabs to the desired temperature in reheat furnaces. HR products differ from QP in that they are thinner and are typically coiled at the end of the hot rolling process. HR is also the input for downstream products discussed in this Decision, including cold rolled, hot dip galvanised, electro-galvanised, organic coated and metallic coated steel for packaging.

(61) Figure 4 shows a slab exiting a reheat furnace, ready to enter the rolling phase in a hot strip mill.

(62) Figure 5 shows a finished HR strip being coiled at the end of the hot rolling mill.

5.1.2.4. Cold rolled products

(63) Cold rolled flat carbon steel products (‘CR’) are the result of the further rolling of HR in cold rolling mills. Cold rolling affects the basic properties of the product by reducing thickness, improving dimensional consistency and providing a smoother surface.

(64) CR is commonly used as an input in the production of coated steel products but may also be sold without further treatment into various applications, including construction, furniture manufacturing, welded tube making as well as packaging and machinery production.

(65) A CR coil is shown in Figure 6.

5.1.2.5. Galvanised products

(66) Galvanised steel products (‘GS’) are flat carbon steel products that have been galvanised to improve their resistance to corrosion. Galvanisation involves coating the flat carbon steel strip with zinc, or a combination of elements with zinc being the primary one. GS is used in applications such as the automotive industry, construction and various engineering industry applications where superior corrosion resistance is required. Both HR and CR can be used as inputs for the production of galvanised products but the clear majority of GS produced by the Parties is made from CR (ArcelorMittal […]%; Ilva […]%).

(67) GS may be obtained via two main production processes: (i) hot dip galvanisation and (ii) electro galvanisation. Hot dip galvanised products (‘HDG’) are produced through uncoiling and reheating the steel strip and feeding it through a bath of molten metal composed of zinc or zinc and other elements at an appropriate temperature. Electro galvanised products (‘EG’) are produced through the application of an electrolytic coating process which results in a zinc-containing coating on one or both sides of the strip.

(68) GS coils are shown in Figure 7.

5.1.2.6. Organic coated products

(69) Organic coated flat carbon steel products (‘OC’) are obtained by adding a thin organic coating, often paint, on GS (or sometimes CR). Organic coating provides for a protective layer and an attractive physical appearance. OC is used in applications such as in construction or the production of furniture and white goods.

5.1.2.7. Metallic coated steel for packaging

(70) Metallic coated steel for packaging consists of thin CR coils or sheets that have been coated with a fine layer of another metal, primarily tin or chromium, resulting in either tinplate (‘TP’) or electrolytic chromium coated steel (‘ECCS’). TP and ECCS are primarily used in the food and beverage industry to produce protective packages (such as food cans).

(71) TP coils are shown in Figure 8.

5.1.2.8. Welded carbon steel tubes

(72) Carbon steel tubes can be produced from flat and long steel products. The production of seamless carbon steel tubes requires input of long steel products, whereas welded carbon steel tubes are manufactured through further processing of flat steel products. Flat carbon steel products such as HR, CR and GS are the main input in the downstream production of welded carbon steel tubes. HR accounts for approximately […]% of input for the production of welded carbon steel tubes, while CR and GS account for the remainder.

(73) Large diameter tubes can be distinguished from tubes with a smaller diameter, due to the differences in their production processes and fields of application. Large tubes have a diameter of more than 20 inches (508mm) for welded tubes and 24 inches (610 mm) for seamless tubes.

5.1.2.9. Distribution of flat carbon steel products

(74) While steel mills tend to supply large orders of standard dimensions with longer lead times, distribution centres typically supply smaller lot sizes and have shorter lead times. In addition to ex-mill sales, flat carbon steel products are sold in the EEA through three types of distribution channels.

(75) The three types of distribution channels are the following: (i) stockholding centres ('SCs'); (ii) steel service centres ('SSCs'); and (iii) oxy-cutting centres. They each perform slightly different functions.

(76) SCs perform a conventional wholesaling function of buying steel in bulk from steel producers and reselling it in smaller quantities. As their main activity, SCs supply products in standard dimensions without further processing.

(77) SSCs purchase strip mill products from steel producers and cut the material based on their customers' requirements. Most SSCs process flat carbon steel products, but not QP or TP. TP is usually processed in dedicated SSCs.

(78) Oxy-cutting centres process and distribute primarily QP.

5.1.3. Primary steelmaking as the driver for the entire flat carbon steel value chain

5.1.3.1. Dynamics of the steel value chain

(79) The market position of flat carbon steel producers in the EEA is by and large determined by their primary steelmaking capacity (that is the capacity to produce liquid steel and slabs). As explained in more detail below, primary steelmaking is characterised on the one hand by high barriers to entry and expansion and, on the other hand, by limited flexibility to efficiently reduce production levels. Likewise, the overall hot rolled capacity typically reflects the primary steelmaking capacity and, in the EEA, is the closest proxy for the upstream market position determining a producer's strength on the markets for finished flat carbon steel products.

(80) First, flat carbon steel production in the EEA is primarily based on the integrated route, that is to say the production of liquid steel through a combination of a blast furnace and a basic oxygen furnace. The EAF-route is relatively insignificant for the production of flat carbon steel products in the EEA in capacity terms and most producers have no EEA flat carbon steel EAF capacity at all. This has been acknowledged by the Notifying Party, which has submitted that approximately […]% of flat carbon steel in the EEA originates in the integrated route while the remaining […]% is of scrap-based EAFs. (20) This applies to the Parties as well: ArcelorMittal produces predominantly through the integrated route with very limited EAF capacity for flat carbon steel products, and Ilva only produces through the integrated route.

(81) Second, the supply-side dynamics of primary steelmaking in the EEA is driven by the characteristics of the integrated route, which requires significant capital investments and which to a great extent relies on the simultaneous and constant operation of a blast furnace and a basic oxygen furnace, and often also a coking and a sintering plant.

(82) In the first place, high capital expenditure and environmental regulation act as an effective barrier to entry or expansion. The Notifying Party estimates that the cost of greenfield investment into an integrated steel plant amounts […]. The Commission understands that the rolling mills account for only a portion of this cost, and the bulk of investment is associated with primary steelmaking capacity. This, compounded with modest demand growth in the EEA, is in line with the finding that, in recent years, the EEA saw no creation of new capacity for the integrated route technology.

(83) In the second place, the integrated route has limited flexibility when it comes to adapting production volumes to demand fluctuations: for technical and economic reasons blast furnaces need to be run at, or close to, maximum capacity. The Notifying Party submits in this respect that production in a blast furnace can be decreased at best down to around […]% of full capacity. Restarting a blast furnace that has been blown down (that is where steel production has stopped) can take several days or weeks, entails high one off costs, and becomes increasingly difficult the longer the blast furnace has been idled. Where a blast furnace is long term idled, or mothballed, the cost of restarting production is estimated by the Notifying Party to around […] of capacity. (21)

(84) Therefore, a steel manufacturer that bases its production on the integrated route is faced with limitations in its ability to alter the production volumes of liquid crude steel and – since casting typically takes place immediately following the production of hot liquid steel – semi-finished products, notably slabs. To allow for a viable operation, the producer needs to produce a certain volume with a blast furnace over extended periods of time, or not to produce with that blast furnace at all. Where supply outstrips demand, the supplier has thus few options to limit the output of blast furnaces in operation. The supplier can only decide to idle one or more blast furnaces altogether in order to align production and demand. On the other hand, the production process for finished products (strips) is not subject to similarly strict limitations from a technical point of view and can be adjusted more flexibly. For example, the cost of restarting a mothballed strip mill / finishing asset is estimated by the Notifying Party to be EUR […] (22), which represents […]% or less of the costs for restarting a mothballed blast furnace.

(85) Third, as a consequence of barriers to entry and expansion, as well as of inflexibility in scaling down production volumes, primary steelmaking capacity typically determines the overall available capacity for the entire flat carbon steel value chain. That said, hot strip mills are not necessarily integrated with primary steelmaking facilities, and they can process slabs sourced from another site of the steel producer or sourced from third parties. This production model is occasionally observed in practice – for instance, […]. Compared to vertically integrated steel mills or intra- company slab supply, production based on slabs procured on the merchant market appears to be of much more limited scope and potentially less efficient. It may be employed as a temporary measure to bridge the imbalances between upstream primary steelmaking output and the requirements for the production of downstream strip products. (23) The vast majority of the hot strip mill capacity (‘HR capacity’) in the EEA mimics the primary steelmaking capacity (‘capacity for crude steel slabs’) located at the same or nearby site.

(86) Fourth, given the interdependence of primary steelmaking and hot strip mills, the competitive position of integrated flat carbon steel producers (that is other than non- integrated re-rollers (24)) is driven by their HR capacity. From the upstream perspective of primary steelmaking, HR is the direct output of processing slabs. From the perspective of the production and supply of flat carbon steel, HR is both a final product and the input for all other finished flat products (including CR, HDG, EG, OC and steel for packaging). Thus, the competitiveness and the capacity for HR is on the one hand determined by primary steelmaking, and, on the other hand, also determines the conditions for the production and supply of downstream products.

(87) Fifth, HR can either be sold on the merchant market or further processed into downstream finished products by the integrated producer. An integrated producer active on the various levels of the flat carbon steel value chain is thus faced with a choice as to at which level of the production chain it sells its steel. Typically the value of steel increases the further it is processed and, moreover, a producer that has installed capacity for the downstream products and needs to pay for the fixed costs so incurred may, in general, be incentivised to employ the existing capacity to produce products on the downstream market. Therefore, an integrated steel manufacturer may be incentivised – to the extent possible in the prevalent market conditions – to direct its HR products into further processing internally. The steel kept by the integrated steel producer for further processing in its own processing facilities is part of the so- called ‘captive market’ of steel, as opposed to the 'merchant market', where the steel is sold by the integrated producers to other steel manufacturers (notably re-rollers), distributors and industrial customers.

(88) However, steel producers do not reserve a given primary/HR capacity solely to the production destined for the merchant market, or for captive use, but use their plants to feed both channels. Given the aforementioned lack of flexibility in adapting the output to demand fluctuations, conditions on the merchant market will not only influence the volume to be sold to third parties, but also HR for captive use. The producer may at least partly reallocate capacity to the channel that provides a more attractive return. For example, if the prices on the merchant market for HR drop, the supplier may reallocate more capacity to captive production for downstream products with a higher added value. The same may occur where there is a shortage on a downstream market, for example for HDG. In other words, the suppliers may leverage their production available to the merchant market in order to react to developments affecting the downstream products, and vice versa. Moreover, suppliers may align their pricing policy for merchant sales of HR and for the sales of downstream products based on HR (for example, by virtue of the base price plus extras pricing model (25)).

(89) Consequently, the higher the overall HR production, the stronger the supplier’s pricing power both directly in the market for HR and in the related downstream markets. Therefore, the competitive assessment should not isolate suppliers’ position in the merchant channel from the remainder of their HR production and capacity.

(90) Finally, non-integrated producers (‘re-rollers’) that source HR coils and then further process them into downstream products such as CR and GS are typical customers of HR coils on the merchant market, and they compete in the downstream CR and GS markets with the integrated producers. Nonetheless, re-rollers depend on the supply of the input HR coils on the merchant market by the EEA integrated producers (and/or imports) and, hence, their market position is affected by the availability and conditions of the supply of HR on the merchant market by the integrated suppliers (and/or imports). The most prominent re-roller in the EEA is Marcegaglia in Italy, […].

(91) The feedback received from market participants during the Commission's market investigation indicates that the competitiveness of re-rollers may be negatively affected by their dependence on sourcing HR coils from EEA integrated producers and/or imports:

'Not controlling the primary steel production increases the risk profile of the business.' (26)

'An integrated supplier can design the steel almost tailor made for the energy industry since specifications are to some extent unique for each customer and application of energy pipes. So it would be almost impossible for a non-integrated steel producer to achieve these qualities.' (27)

'Manufacturers who do not have the entire production process often acquire the basic products for the processing of their products from very different sources and sometimes they bring discontinuous qualitative results on the finished product. So in principle a supplier is preferable which has the entire production process.' (28)

'Marcegaglia (the most important re-roller / re-roller) has quality generally lower than steel mills; range of products generally lower than steel mills; containing of products over time much lower than steel mills. [Our company] does not know the reinsurers' business strategies but believes that re-rollers generally buy HR coils where these have favourable economic conditions. Therefore the HR suppliers change and therefore the characteristics of the materials also change downstream (CR and GS) that are produced from the HR. However, this aspect does not occur with integrated steel mills: these have their own "recipes" of production and tend to keep them stable in the time.' (29)

(92) The potential exposure of re-rollers to shocks, and particularly measures on imports, is illustrated in […]: (30)

[…].

5.1.3.2. Example: Development of the Ilva Group’s production

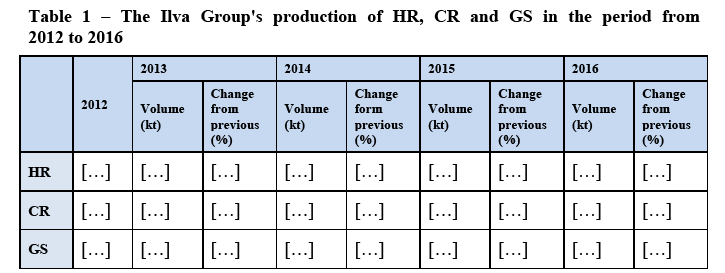

(93) Preference for the captive use of HR may be observed, for instance in the development of the Ilva Group’s production following reductions in its hot metal and HR production. While the Ilva Group’s production of HR decreased from […] in 2012 to […] in 2016, that is by […]%, its CR production only decreased from […] to […] ([…]%) and its GS production actually increased from […] to […]. This shows that Ilva Group favoured captive use of its HR production and consequently reduced its sales on the merchant market. The development of the Ilva Group’s production during 2012–2016 is shown in Table 1.

5.2. Introduction to the Parties' activities

5.2.1. ArcelorMittal

(94) ArcelorMittal, (31) based in Luxembourg, is the leading flat carbon steelmaker in the EEA. It was formed in 2006 through the takeover and merger of West European steel maker Arcelor (Spain, France and Luxembourg) by Indian-owned Mittal Steel. ArcelorMittal produces approximately 10% of the world's steel. It is listed on the stock exchanges (32) of New York (MT), Amsterdam (MT), Paris (MT), Luxembourg (MT) and on the Spanish stock exchanges of Barcelona, Bilbao, Madrid and Valencia (MTS), and is a member of more than 120 indices. In 2016 ArcelorMittal had total revenue of EUR 53 951 million and reached EUR 3 952 million EBITDA result.

(95) ArcelorMittal is the only EEA manufacturer with an EEA-wide production network, with production facilities throughout the continent, including primary steel making facilities in Spain (Sestao and Aviles), France (Fos-sur-Mer, Atlantique and Florange), Belgium (Ghent), Germany (Bremen and Eisenhüttenstadt), Poland (Katowice Steelworks and Tadeusz Sendzimir Steelworks), the Czech Republic (Ostrava) and Romania (Hunedoara Steel Works and Galati Steel Works).

(96) On top of its direct business, ArcelorMittal jointly controls with other partners a number of other manufacturing, trading and distribution activities, and holds minority shareholdings in a number of other companies active in the steel manufacturing and supply chain.

(97) In particular, with particular relevance to the EEA, ArcelorMittal has a 50% stake in a joint venture with Macsteel (steel trading and distribution) in the Netherlands; a 50% stake in a joint venture with Tamec (energy production and supply) in Poland and 45.33% stake in a joint venture with Borcelik (manufacturing and sale of steel), Turkey (33). Furthermore, ArcelorMittal has 33.43% ownership and voting rights in DHS Groups, Germany (steel manufacturing), 35% ownership in Gonvarri Steel Industries, Spain (steel manufacturing), 35% ownership and voting rights in Gestamp, Spain (manufacturing of metal components); 28.47% ownership and voting rights in Stalprodukt S.A., Poland (production and distribution of steel products). ArcelorMittal also holds shares in the Turkish crude steel producer, 'Erdemir' (34) (Ereğli Demir ve Çelik Fabrikaları, Ereğli Iron and Steel Factories,), which has, according to the Notifying Party, around […] of crude steel capacity.

(98) ArcelorMittal also has a wide distribution network. For instance, in Italy it has a 49% controlling interest in ArcelorMittal CLN Distribuzione Italia. In France, ArcelorMittal operates several SSCs through its subsidiary ArcelorMittal Distribution Solutions France.

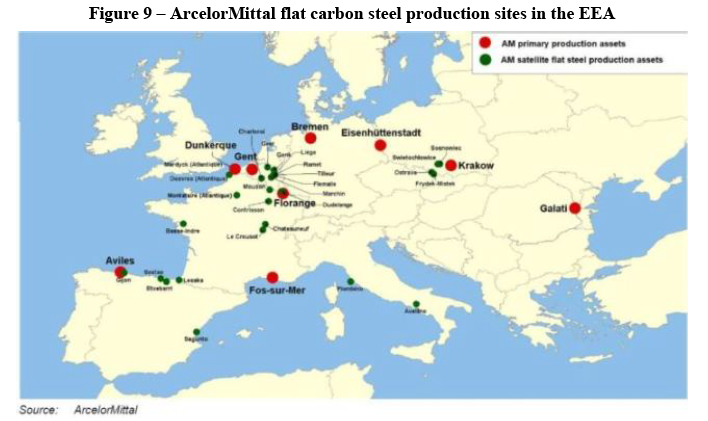

(99) Figure 9 shows the flat carbon steel production plants of ArcelorMittal in the EEA. ArcelorMittal's primary production assets are in Northern Continental Europe, in Eastern Europe and in Spain and South of France.

(100) ArcelorMittal's primary steel making production site closest to Ilva is located in Southern France (Fos-sur-mer), producing both crude steel slabs and HR, but ArcelorMittal also operates further crude steel and HR production sites in Southern Europe, namely in Aviles in Northern Spain (and an EAF facility in Sestao, also in Northern Spain). In the South of Europe, ArcelorMittal also has three satellite plants in Italy (Avellino, Canossa and Piombino), and five downstream plants in Spain (Sagunto, Extebarri, Lesaka, Sestao, Gijon), which are active in the production of downstream flat carbon steel products, such as CR and HDG in Italy and CR, HDG, EG and metallic coated steel for packaging in Spain.

5.2.2. Ilva

5.2.2.1. The Ilva assets subject to the Transaction

(101) With its Taranto plant, Ilva is the EEA's largest single-site integrated steel production facility (35). Ilva's history dates back to 1911 when six independent steel companies established the Ilva Consortium for the management of their plants, which covered the whole Italian national production of pig iron. Ilva S.p.A and other Ilva Group companies were acquired by the Riva family in 1996 from the Italian State, which previously controlled these companies through the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (‘IRI’).

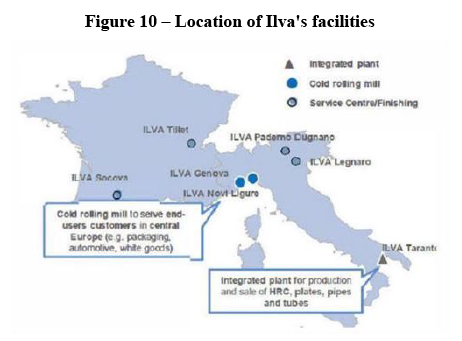

(102) Ilva’s main production site in Taranto, opened in 1964, is located in the South of Italy next to the deep sea port of Taranto. Ilva has two other production plants in the North of Italy, in Genoa and Novi Ligure, as well as six steel service centres (three in the plants, plus Marghera, Paderno and Legnaro). These other facilities do not have internal HR production capability but process HR provided by the plant in Taranto. In France, Ilva Group also has a steel service centre (Tillet), and a welded tube production site (Socova) (36). Figure 10 shows the location of Ilva's facilities. (37) Those facilities are all part of the Transaction and constitute part of the Ilva assets.

(103) The Ilva assets have a technical blast furnace capacity of […] and slabs capacity of almost […]. However, due to the restrictions to which it is currently subject, this capacity is temporarily limited to […]. The HR coil production capacity of the Ilva assets amounts to […] but it is currently effectively limited at […] due to the capacity restriction upstream. At its current level of capacity, the Taranto plant accounts for circa […]% of the total EEA production capacity for HR. (38) The Taranto plant is capable of producing not only crude steel but also a number of downstream products, including QP, HR, CR and GS. The steelworks also has the capability to produce welded tubes.

(104) The plant in Taranto has favourable production conditions due to its economies of scale, its close location to a seaport and relatively modern facilities. This is illustrated in Figure 11 (39), which places the EEA production plants in relation to the age and size of their blast furnace.

Figure 11 – Age and size of the blast furnaces of flat carbon steel plants in EEA

[…]

(105) The Ilva assets can produce and supply a wide range of flat carbon steel products. Figure 12 shows the wide product range of the Ilva assets in the flat steel market with the percentage of production share and the industries using those products.

Figure 12 – Ilva's products and production share (40)

[…]

5.2.2.2. Events leading to the sale of the Ilva assets

(106) In the past years, Ilva has faced events leading to a reduction in its production volumes. In particular, the HR production area in the Genoa plant was closed in 2005. In 2008, the Puglia region, where the Taranto plant is located, enacted a Regional Law against dioxins, which imposed limits for industrial emissions starting from 2009. In 2009, Ilva closed certain production facilities. (41)

(107) The blast furnaces (42) of Taranto have been running at around […]% of their nominal capacity (three blast furnaces working out of five) since 2013 due to environmental constraints imposed on Ilva. In July 2012 the public prosecutor of Taranto subjected Ilva's local HR production lines to temporary seizure due to environmental issues. The Italian Government issued Law Decree no. 207/2012, (43) laying down conditions to issue an Integrated Environmental Authorisation (Autorizzazione Integrata Ambientale – ‘A.I.A’), to restart production activity. Under such authorisation, a production cap has been imposed to reduce emissions.

(108) The former management of Ilva Group, namely the Riva family, had to step aside and was replaced by a government-appointed Extraordinary Commissioner in June 2013. (44) The Extraordinary Commissioner had a mandate to ensure the continued industrial activity of Ilva. The Extraordinary Commissioner of 2013 designed an environmental plan to prevent further pollution and upgrade the Taranto plant in compliance with the environmental permit (the ‘2014 Environmental Plan’) (45) , which was approved on 14 March 2014 by the Council of Ministers. According to the 2014 Environmental Plan, the investment needed to bring the Taranto plant in line with the requirements of the environmental permit amounts to EUR 1.75 billion.

(109) The 2014 Environmental Plan further constrained the production levels of Ilva, which has started suffering losses at EBITDA level in 2012 after many positive years (excluding 2009 when certain production plants were closed).

(110) Table 2 shows the total shipments of Ilva S.p.A. (reduced due to the production caps imposed and plant closures in 2009) for the years 2004–2017, including ArcelorMittal's plan for 2018, and selected financial figures of Ilva S.p.A in those years.

Table 2 – Ilva S.p.A's shipments and selected financial figures 2004 -2017 (46)

[…]

(111) As described in recital (107), Ilva S.p.A has operated at around […]% of its nominal capacity since 2013, […] (47). For instance, according to a competitor of Ilva:‘Steel production involves significant sunk and fixed costs. Not producing is usually more expensive than producing. That is because the steel assets require significant capex [capital expenditure] to build and their maintenance, even if standing idle, is expensive. There are thus significant economies of scale that push to producing at high utilisation levels, particularly at the liquid and hot stages of the production.’ (48)

(112) At the same time, the lower production level could not support the necessary environmental investments and the fixed costs. Besides operational inefficiencies, it appears that the main drivers of the operational loss have been the unproportioned fixed costs and the loss in spread on steel sales. The fixed costs have remained mostly unchanged. Labour costs represented […]% of fixed cost in 2014 and 2015, as calculated based on available data for 2014 and 2015. (49)

(113) The operating result of Ilva S.p.A. (50) further suffered due to the decreased spread on steel sales, which decreased from around EUR […] from 2004 onwards to around EUR […] in 2013. Figure 13 from Ilva Group's business plan in May 2014 shows the historical development of the HR coil spread (the difference between average HR coil selling price and raw material basket cost) for the period of 2000-2013, and the expected development of such spread from 2013 onwards. The decreased spread coupled with the production cut significantly affected Ilva S.p.A's performance, as it incurred substantial losses.

Figure 13 – Historical hot rolled coil spread 2000-2013 (51)

[…]

(114) In June 2014, the Italian Government explored a potential interest of ArcelorMittal in acquiring Ilva Group. In November 2014, […], ArcelorMittal submitted a non- binding offer for certain assets of Ilva Group […], (52) but the assets were not eventually sold by the Italian government. In January 2015, Ilva Group was admitted to extraordinary administration.

(115) Under Law Decree no. 1/2015, an ad hoc insolvency procedure for Ilva Group was introduced. (53) Subsequently, Law Decree no. 191/2015 entitled ‘Disposizioni urgenti per la cessione a terzi dei complessi aziendali del Gruppo Ilva’ provided for the sale of Ilva Group's assets through a transparent and non-discriminatory public procedure.

(116) On 5 January 2016, the Extraordinary Commissioners of Ilva Group published a call for expressions of interest in relation to the transfer of businesses owned by Ilva Group. Twenty-five interested parties were admitted to the preliminary due diligence phase, following which acquisition consortia were formed for the submission of formal offers by 30 June 2016. On 30 June 2016, two bidders were admitted to the final phase of the tender process: (i) the AM Consortium (as described in recital (9)) and (ii) the AcciaItalia Consortium (‘AcciaItalia') formed, inter alia, by the Italian steelmaker Arvedi, the Indian steel company Jindal Steel and the State-owned investment bank Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (‘CDP’).

(117) On 26 May 2017, Ilva Group's Commissioners recommended to award the Ilva assets to the AM Consortium, (54) which offered a price of EUR 1.8 billion. (55) The Italian Minister of Economic Development issued the final adjudication decree in favour of the AM Consortium on 5 June 2017. (56)

5.3. Sources of supply

(118) In the EEA, flat carbon steel is supplied by (i) EEA-based integrated suppliers,

(ii) EEA-based non-integrated suppliers and (iii) non-EEA suppliers (imports).

(119) Integrated suppliers are active throughout all or most of the flat carbon steel value chain, and they are capable of producing semi-finished products (slabs) and HR internally. Integrated suppliers are thus generally not dependent on external sourcing of HR for their downstream production. Integrated EEA-based suppliers of flat carbon steel products include, for instance, ArcelorMittal, the Ilva Group, Arvedi, ThyssenKrupp, Tata Steel Europe, Salzgitter, Voestalpine and SSAB.

(120) Non-integrated suppliers (sometimes also referred to as ‘re-rollers’) are only active in the production and supply of one or more flat carbon steel products downstream of HR. These suppliers thus depend on third parties for their supply of HR, which they process to downstream products for instance by re-rolling the HR into CR. Some of the non-integrated suppliers may be integrated between the downstream products, for instance in the production of all of CR, HDG and OC. Non-integrated EEA-based producers include, for instance, Marcegaglia and Wuppermann.

(121) Non-EEA supplies consist of imports of flat carbon steel produced outside the EEA. They are considered further in Section 5.3.3.

5.3.1. EEA-based integrated suppliers other than the Parties

(122) The locations of the main integrated flat carbon steel producers are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14 – Locations of main EEA integrated suppliers

[…]

(123) Within the EEA, the majority of integrated producers are located in Central and Northern Europe, including ThyssenKrupp and Salzgitter primarily in Germany, Tata Steel in the Netherlands and in the UK, Voestalpine in Austria, US Steel Kosice in Slovakia, and SSAB in Finland and Sweden. In contrast, only Ilva Group, ArcelorMittal and Arvedi have major production assets in Southern Europe.

5.3.1.1. ThyssenKrupp

(124) ThyssenKrupp Steel Europe (‘ThyssenKrupp’) is headquartered in Germany. ThyssenKrupp is one of Europe’s major flat carbon steel producers and it is active throughout the flat carbon steel value chain from primary steel production to coated finished products.

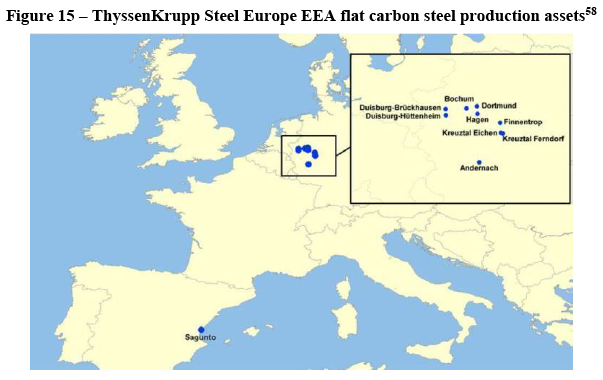

(125) ThyssenKrupp operates a number of production sites in the EEA, mostly in Germany where also all of its primary steelmaking capacity is located. According to the Notifying Party, ThyssenKrupp produces for instance: (57)

· HR in four plants in Germany (Duisburg-Bruckhausen, Duisburg-Beeckewerth, Bochum and Hagen) with a total production capacity of ca. […] and with a product portfolio that […].

· CR in five plants in Germany (Duisburg-Bruckhausen, Duisburg-Beeckewerth, Bochum, Dortmund and Andernach), including both commodity and high- value CR.

· GS in eight plants. Seven of these plants are located in Germany (Duisburg- Bruckhausen, Duisburg-Beeckewerth, Bochum, Dortmund, Finnentrop, Kreutzal Eichen, and Kreutzal Ferndorf), and one in Spain (Sagunto). ThyssenKrupp supplies a wide range of products, […].

(126) The locations of ThyssenKrupp’s production plants, as submitted by the Notifying Party, are shown in Figure 15.

5.3.1.2. Tata Steel

(127) Tata Steel (‘Tata’) is headquartered in India and has operations in 26 countries worldwide. Tata is one of the major EEA flat carbon steel producers and it is active throughout the flat carbon steel value chain from primary steelmaking to coated finished products.

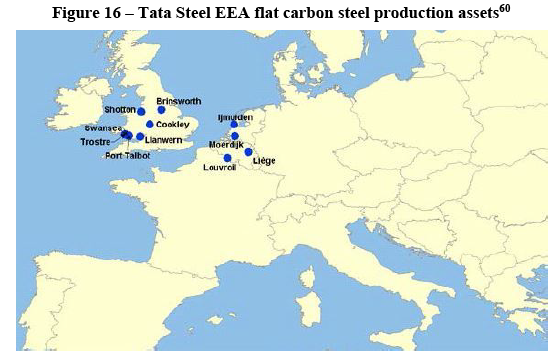

(128) In the EEA, Tata operates a number of production sites in the UK, the Netherlands, Belgium and Northern France. Its primary steelmaking sites with blast furnaces are located in the UK and in the Netherlands. According to the Notifying Party, Tata produces: (59)

· HR in four production sites, three located in the UK (Brinsworth, Port Talbot, and Llanwern) and one located in the Netherlands (Ijmuiden), with total capacity of circa […].

· CR in six plants, four located in the UK (Brinsworth, Llanwern, Port Talbot, and Trostre), one in the Netherlands (Ijmuiden) and one in France (Louvroil). Tata’s CR production range includes […].

· GS in eight plants, four located in the UK (Llanwern, Cookley, Swansea and Shotton), two in the Netherlands (Ijmuiden and Moerdijk), one in Belgium (Liège) and one in France (Louvroil). Tata’s range focuses on […].

(129) The locations of Tata’s production assets, as submitted by the Notifying Party, are shown in Figure 16.

5.3.1.3. Arvedi

(130) The Italy-based and family owned Arvedi Group, founded in 1963, is active throughout the flat carbon steel value chain from primary steelmaking to coated finished products. Arvedi employs the EAF route for its steel production.

(131) According to the Notifying Party, Arvedi operates one production site in Cremona,

Italy with a HR production capacity of ca. […]. The site also produces CR and GS. (61)

(132) The Arvedi Group was part of the AcciaItalia Consortium. According to Arvedi, the Consortium planned to increase the production output of the Ilva assets and reach 10 Mt of steel production annually. Moreover, the AcciaItalia Consortium planned to close down two of the Ilva assets' ovens and instead use the DRI technology, which use gas instead of coal, as it expected that gas prices would be lower in the future. (62)

5.3.1.4.Other integrated EEA suppliers

(133) In addition to the suppliers referred to in Sections 5.3.1.1 to 5.3.1.3, there are a number of other integrated and non-integrated suppliers of flat carbon steel with production in the EEA. These include:

(134) Salzgitter AG (‘Salzgitter’) is an integrated steel producer headquartered in Salzgitter, Germany. Salzgitter operates several steel plants in the EEA, three of which are dedicated to flat carbon steel production and are located in the neighbourhood of Salzgitter. According to the Notifying Party, Salzgitter has HR production capacity of approximately […] and it also produces CR and GS. (63) The locations of Salzgitter’s production sites, as indicated by the Notifying Party, are shown in Figure 17.

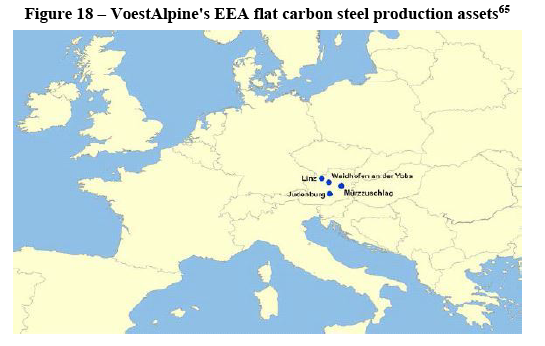

(135) VoestAlpine, is an integrated steel producer based in Austria. VoestAlpine operates five steel plants in the EEA, four of which are dedicated to flat carbon steel production, all located in Austria. According to the Notifying Party, VoestAlpine has a HR production capacity of circa […] and it also produces CR and GS, all with product portfolios […]. The locations of VoestAlpine’s production sites, as indicated by the Notifying Party, are shown in Figure 18.

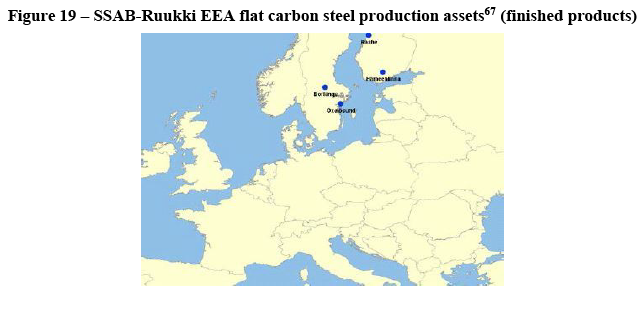

(136) SSAB-Ruukki is an integrated steel producer headquartered in Sweden and with EEA steel production plants in Sweden and Finland. According to the Notifying Party, SSAB-Ruukki has a HR production capacity circa […] with a product portfolio […]. SSAB-Ruukki also produces CR with a […]. The locations of SSAB-Ruukki’s EEA production sites for finished flat carbon steel, as indicated by the Notifying Party, are shown in Figure 19. (66)

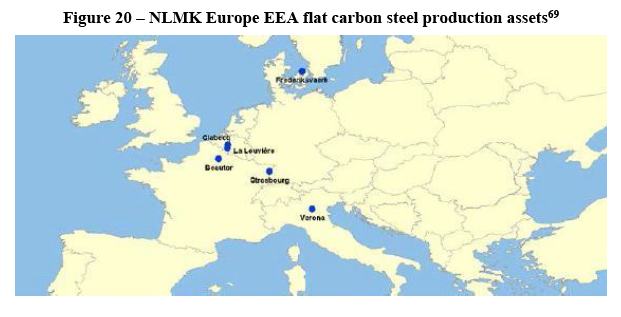

(137) NLMK Europe operates, according to the Notifying Party, six steel production sites in the EEA, located in France (Strasbourg and Beautor), Belgium (La Louvière and Clabecq), Denmark (Frederiksvaerk) and Italy (Verona) as shown in Figure 20. According to the Notifying Party, NLMK Europe’s HR production plant is located in Belgium (La Louvière), with capacity of circa […] with a […]. NLMK Europe also produces commodity CR and GS in the EEA. The locations of NLMK's EEA production sites for finished flat carbon steel, as indicated by the Notifying Party, are shown in Figure 20. (68)

(138) Further EEA suppliers of flat carbon steel include, for instance: ISD, a Ukraine- based steel producer that operates production sites in Poland (Częstochowa – QP capacity) and Hungary (in Dunaújváros, where it operates under the name Dunaferr – HR, CR and GS capacity), with total HR capacity of circa […] (70); US Steel, a US- headquartered steel producer with operations in North America and Central Europe. It operates one flat steel production plant in the EEA, located in Košice, Slovakia with HR, CR, GS, TP and OC capacity (‘USSK’); and Wuppermann, a Dutch- headquartered steel manufacturer with production facilities in Austria (Judenburg and Linz), Hungary (Győr-Gönyű) and the Netherlands (Moerdijk). Wuppermann focuses on GS products. (71)

5.3.2. EEA-based non-integrated suppliers

5.3.2.1. Marcegaglia

(139) Marcegaglia is Ilva’s largest customer, and one of the leading steelmakers in the South of Europe. It has an annual output of about 5.4 million tonnes of steel products. (72) However, different from Ilva Group and ArcelorMittal, Marcegaglia is a non-integrated re-roller and does not have its own HR (or slabs) production capacity.

(140) Marcegaglia, established in 1959, is Europe’s largest non-integrated steel supplier processing mainly carbon steel but also stainless steel in its rolling mills and SSCs. Processing steel accounts for 90% of the Marcegaglia Group’s turnover (73), the remaining 10% being generated from six other business areas: building, home products, engineering, energy, tourism and services.

(141) The Marcegaglia Group is headquartered in Gazoldo degli Ippoliti, Mantova in Northern Italy and employs 5 400 people directly (mostly in the EEA). Marcegaglia has 16 steel processing plants (including SSCs) in Italy (74), and 6 other steel plants around the world (UK, Poland, Russia, USA, Brazil and China). Marcegaglia has a minority stake in a steel mill in Bremen, Germany, which is owned by ArcelorMittal (‘AM Bremen’).

(142) Marcegaglia covers the steel value chain downstream from HR with its product offerings as Figure 21 shows.

Figure 21 – […] (75)

[…]

(143) Marcegaglia's plants dedicated to the production of flat carbon steel products are located in Italy in Albignasego (CR lines), Gazoldo – Mantova (CR lines), Ravenna (CR lines, GS lines, OC lines) and S.Giorgio Nogaro - Udine (QP lines) (76). Marcegaglia’s processing plant at Ravenna, on Italy’s northern Adriatic coast, is one of the largest steel processing site in the EEA capable of processing over […] of coil products a year. The main import port of Marcegaglia is also located in Ravenna, from where it distributes steel for further processing to other Marcegaglia plants within Italy. The port can handle ships of 40 thousand DWT (77).

5.3.2.2. Business model of Marcegaglia

(144) Apart from Marcegaglia, all the most significant rerolling facilities in the EEA are owned by the integrated steel manufacturers. While there are some other independent re-rollers active in the EEA, particularly in Italy and Germany, those companies are typically niche players focussed on a specific grade and market segment that have significantly smaller capacities than Marcegaglia (78). In this respect, and due to its size, the business model of Marcegaglia is unique in the EEA.

(145) Due to its size, and its lack of primary steel production capability, Marcegaglia is the largest independent HR coil consumer in the EEA, and one of the largest in the world.

(146) Historically Marcegaglia was a SSC operator and a tube manufacturer. Marcegaglia’s entry into the production of CR, GS and OC products only took place around year 2000. Thus, Marcegaglia has already moved upwards in the integration ladder even if it has not acquired HR production capacity (79).

(147) Marcegaglia observed that in order to produce higher quality products, stability in the supply chain is necessary. In order to achieve this, and to ensure a steady supply of a certain volume of HR, Marcegaglia has decided to focus on long term structural industrial agreements instead of investing in a steel mill (80).

(148) Marcegaglia has agreements to ensure the supply of steel for processing which arrives largely in the form of HR, but also as slabs (81). Besides Ilva, ArcelorMittal is the other important EEA supplier of Marcegaglia, with annual supply of around […], mostly supplied from ArcelorMittal's Bremen plant, in which Marcegaglia also holds a minority shareholding. Apart from Ilva Group and ArcelorMittal, Marcegaglia sources some HR coil volumes from other EEA suppliers, as well as from imports. Marcegaglia's sourcing from EEA suppliers other than ArcelorMittal and Ilva Group is more limited, due to those other suppliers' more limited capacity (‘the lack of available HR volumes’), focus on other geographic regions (‘sells them[HR] in northern Europe and not in Italy’), or the large proportion of captive use (‘ThyssenKrupp, Voest Alpine and SSAB offer no real volumes limiting their feeding to the captive market’ (82).

(149) Marcegaglia is a significant importer of HR to Italy and to the EEA. It sources in the range of 40-60% of its need from EEA suppliers, while the rest is sourced from imports.

(150) Even though Marcegaglia imports substantial volumes of HR, it holds the view that ‘it is not easy to import significant quantities from other countries worldwide. Firstly, many markets are getting more regional with local producers giving priority to their domestic/regional markets. …As a matter of fact, Marcegaglia in 2016 and even more in 2017 needs to buy slabs and roll them into HRC through a hire-rolling agreement, in order to support its needs; such agreements are only temporary and volatile. They cannot represent a solid source in the long term. For many other users, smaller than Marcegaglia, it is not easy to source [import] from everywhere because of size, service requirements and financial reasons.’ (83)

5.3.2.3. […]

(151) Marcegaglia acquired its minority shareholding of […] in AM Bremen […]:

Table 3 – […] (84)

[…]

(152) […] (85).

(153) With regard to re-rolling of slabs, Marcegaglia explained (86) that the ‘indispensable factors to make it become a feasible option are: good established networks with slab providers; stability of the mill and flow required (e.g. Marcegaglia has in place very regular contract with Ilva for theoretically converting slab to HR up to […] of HR); possibility to finance a long cycle that results in higher costs; and logistic optimization (e.g. running a vessel with a capacity of at least […] tonnes).’

(154) […]. (87)

(155) […] (88).

5.3.2.4. Marcegaglia's participation in the AM Consortium

(156) Marcegaglia Carbon Steel S.p.A. is participating in the AM Consortium […]. (157) […].

(158) […].

5.3.3. Imports and anti-dumping measures

5.3.3.1. Imports of flat steel products into the EEA

(159) As mentioned above in Section 5.3, the production and supply of flat carbon steel products in the EEA is covered by integrated steel producers based in the EEA, non- integrated suppliers based in the EEA and non-EEA based suppliers (imports). This Section provides a brief overview of (i) the role imports play as a source of supply for EEA customers of flat carbon steel products; (ii) the flows of imported flat carbon steel products; and (iii) historical developments regarding imports of flat carbon steel products into the EEA.

(160) First, the Commission notes that the EEA flat carbon steel industry is to some extent affected by steel trade flows with non-EEA countries, that is imports and exports of flat carbon steel products. EEA-based steel producers export certain volumes of their production to countries outside the EEA. At the same time, non-EEA steel manufacturers from different countries export certain flat carbon steel products into the EEA. As such, EEA customers of flat carbon steel products may source these products not only from EEA-based steel producers, but also from producers based outside the EEA. The sourcing from imports differs and is to some extent limited by certain non-price related factors. Those factors will be specifically discussed in Sections 9.4.5.8 and 9.7.5.4.

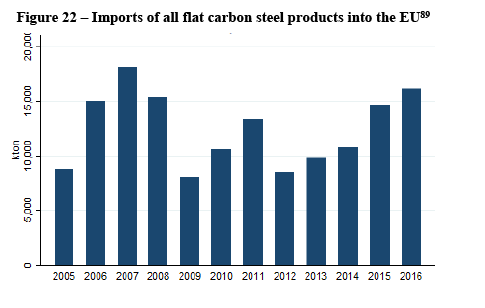

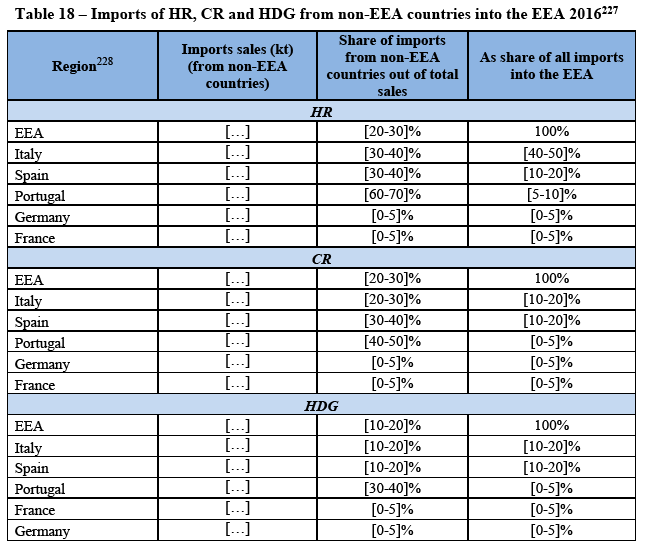

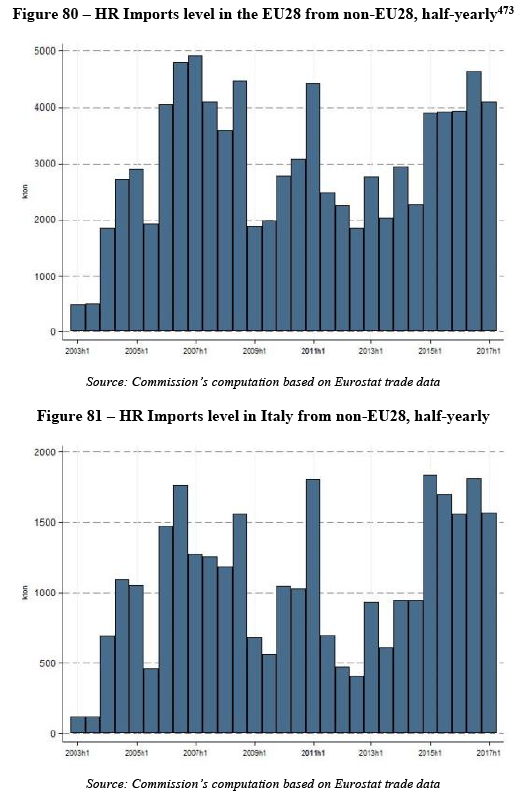

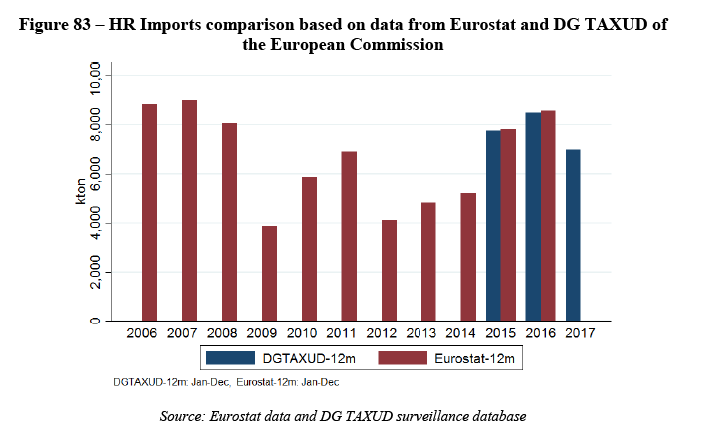

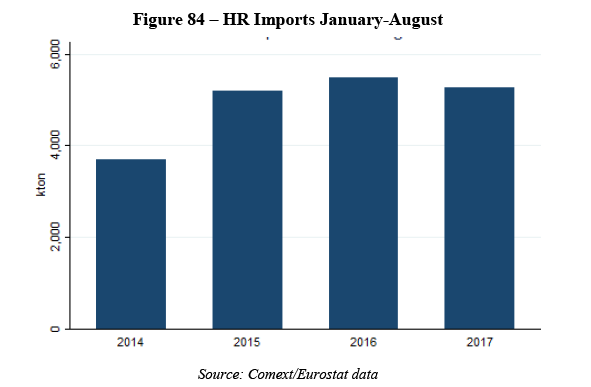

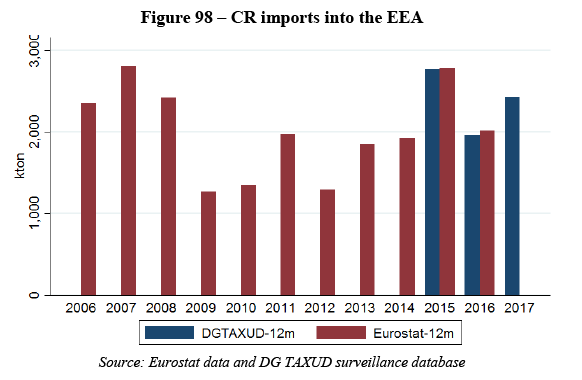

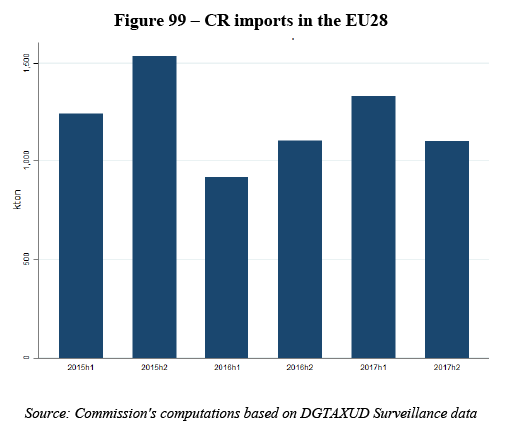

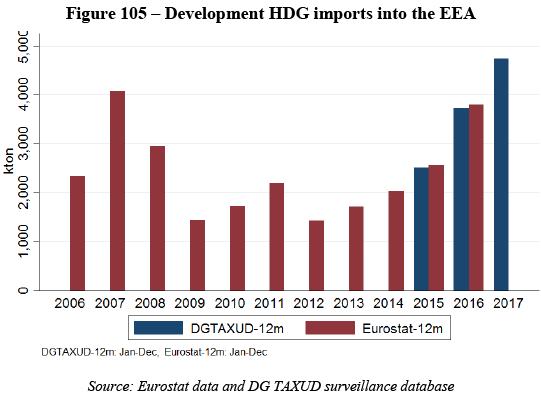

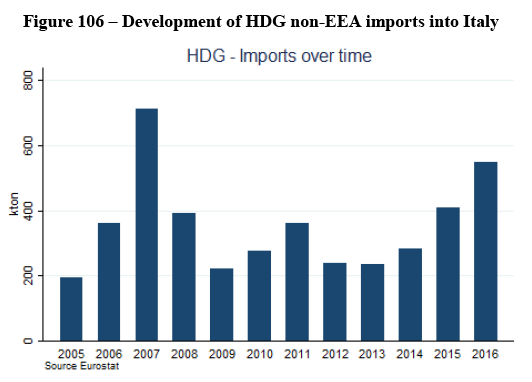

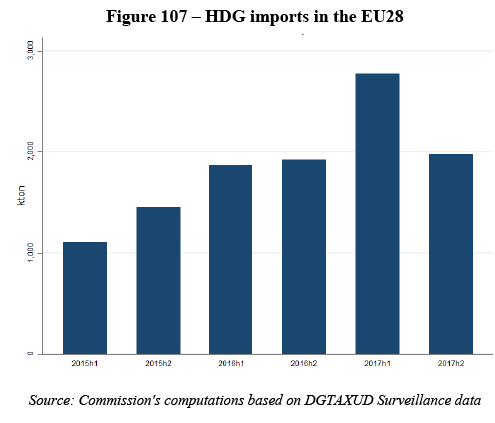

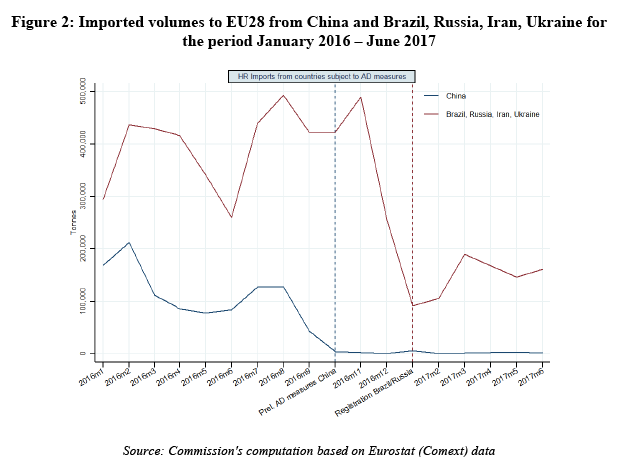

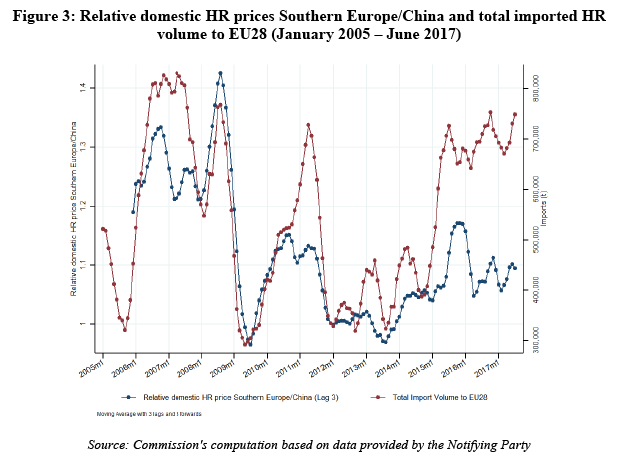

(161) Second, the flows of imported flat carbon steel products vary significantly year to year and are affected by numerous macro-economic and micro-economic factors. Historical data shows that imports of flat carbon steel products flow into the EEA in 'waves', that is periods with high levels of imports are followed by periods when the flow of imports is reduced and vice versa. Such waves are illustrated in Figure 22, which shows the imports of all flat carbon steel products for the time period 2005-2016.

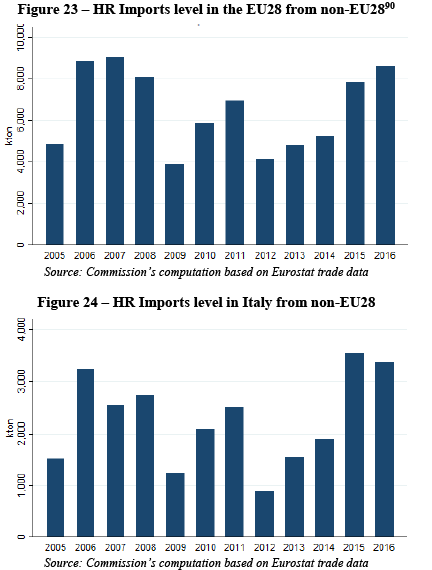

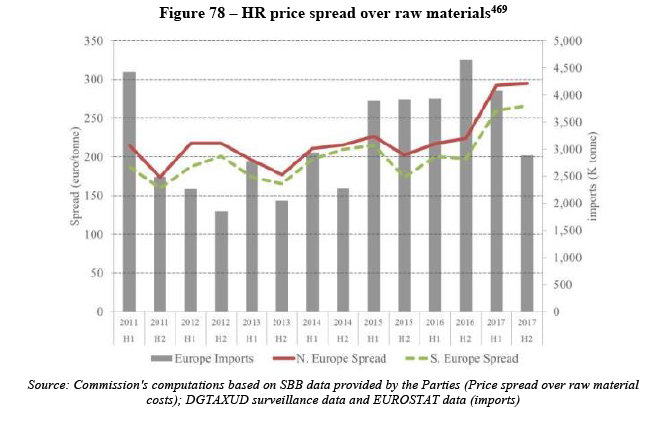

(162) Moreover, Figure 23 and Figure 24 depict such import flow 'waves' specifically with respect to HR, respectively into the EU and into Italy. It can be observed that for example the period between 2006–2008 was characterised by high levels of import flows, followed by a period of significant reduction in imported HR, and then again followed by an increase in imports in 2010–2011. Then, the period 2012–2014 is again a period of relatively low import flows followed by an increase in imports in the period 2015–2016 (for 2017 complete annual data are not available).

(163) Third, imports are also affected by anti-dumping measures as described in the next Section. In recent years, there have been several anti-dumping measures (provisional or definitive) that have been imposed by the Commission on specific non-EEA producers. The purpose of these trade defence measures is to remove injurious effects of dumped or subsidised imports on the Union industry producers that produce the like products. Such trade measures might further affect the attractiveness of imports as EEA customers might become liable to pay higher duties for their imported material, or imports may be diverted away from the EEA, when trade defence measures are imposed.

5.3.3.2. The European trade defence regime

(164) At present, certain flat carbon steel products entering the EU are subject to anti- dumping duties. The effect of the anti-dumping duties on the competitive environment in the specific product markets is assessed in more detail in Sections 9.4.5.7, 9.5.5.3 and 9.7.5 of this Decision. However, this Section aims to provide a brief overview of the EU's anti-dumping and anti-subsidy regime, while the next Section describes the trade defence measures currently imposed on specific products falling within the product markets concerned by this Decision.

(165) The Commission is responsible for investigating allegations of dumping by exporting producers from non-EU countries. The general procedural rules applicable to anti- dumping investigations as well as the substantive rules for imposing anti-dumping duties are set out in Regulation (EU) 2016/1036 of the European Parliament and of the Council.- (91) Article 1(1) of that Regulation states a general principle whereby 'an anti-dumping duty may be imposed on any dumped product whose release for free circulation in the Union causes injury.'

(166) The Commission may initiate an investigation after receiving a written complaint submitted by any natural or legal person, or any association not having legal personality, acting on behalf of the Union industry. Such complaint needs to be supported by a sufficient representation of the Union producers and sufficient evidence that dumped or subsidised imports originating in non-EU countries are causing or threatening to cause material injury to a Union industry. In special circumstances, the Commission may initiate an investigation on its own initiative. (92)

(167) Once an anti-dumping investigation is launched, the Commission has maximum 15 months to conduct its investigation and finalise its findings in anti-dumping cases and 13 months in anti-subsidy cases. (93)

(168) The scope of the Commission's anti-dumping investigation consists in determining whether (i) the product under investigation ('the product concerned') originating in the countries concerned is being dumped or subsidised; (ii) the dumped imports have caused injury to the Union industry; and (iii) it is in the wider Union interest to impose measures.

(169) Moreover, the finding of dumping and subsidisation covers a defined period (the 'investigation period') while the examination of trends relevant for the assessment of injury, causality and Union interest covers longer time periods, typically four years. In the context of the Union interest test, the Commission examines whether the interest of the Union industry in being relieved from the injury caused by the unfairly traded imports is outweighed by the burden the trade defence measures would create for the downstream market, including importers and users (for example customers). Typically, the Commission carefully examines the impact of the planned measures on the cost structure of the importer and the user industry on the basis of verified questionnaire responses from the downstream companies concerned.

(170) If the Commission finds that the required conditions for imposing trade defence measures are met, the Commission may impose measures on the product concerned. The measures may take a number of different forms, including an ad valorem duty, specific duty or minimum import price. The Commission may also accept price undertakings from specific companies.

(171) Even before an adoption of definitive anti-dumping measures, the Commission may decide to adopt provisional anti-dumping measures. Article 7 of Regulation (EU) 2016/1036 empowers the Commission to impose provisional duties if certain conditions are met, including the condition of a provisional affirmative determination having been made of dumping and consequent injury to the Union industry and of Union interest. Any such provisional duties must be imposed no earlier than 60 days and no later than nine months from the initiation of the proceedings. (94)

(172) Trade defence measures are imposed for a period of five years and may, in some circumstances, be subject to review. However, unless an expiry review is initiated, a definitive trade defence measure will expire after five years. (95)

5.3.3.3. Trade defence measures currently in place and ongoing anti-dumping investigations by the Commission

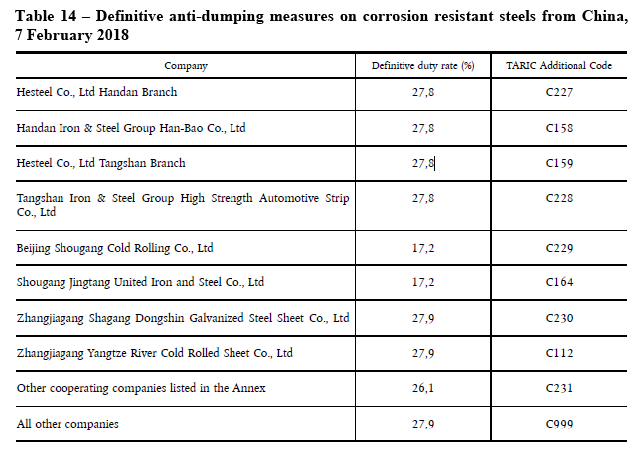

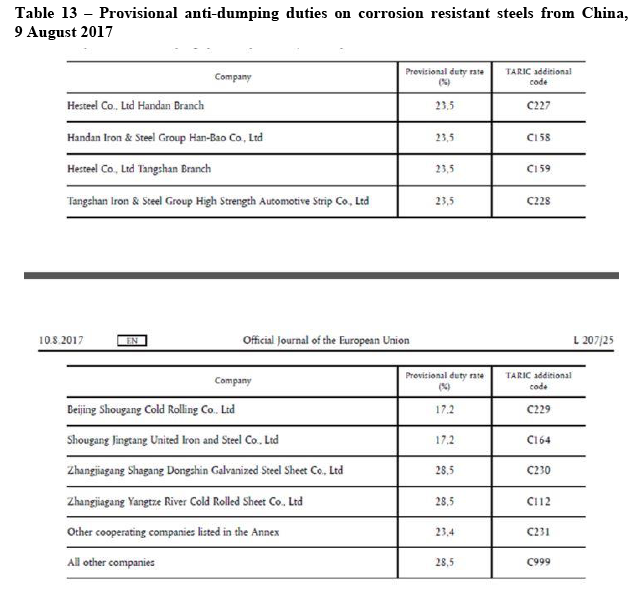

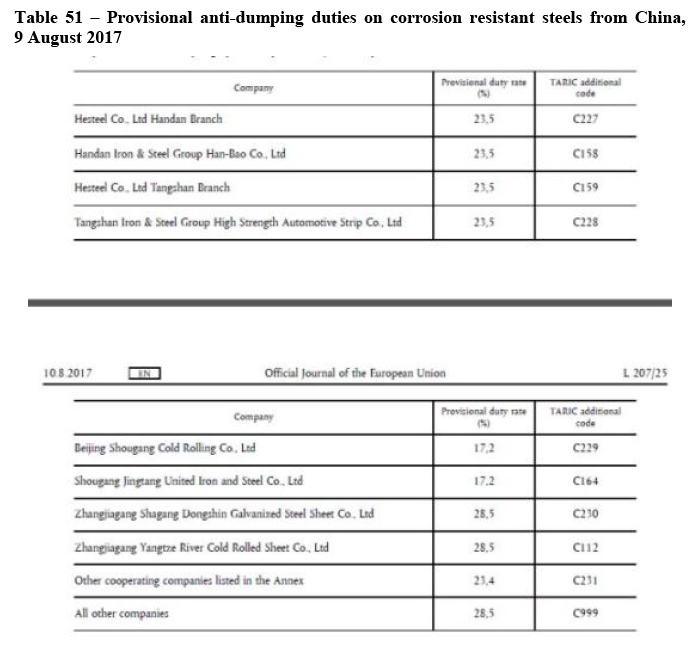

(173) The Commission has conducted a number of anti-dumping investigations with regard to different steel products in recent years. As a result of these investigations, there are currently definitive trade defence measures in place on HR products originating in China as well as Brazil, Iran, Russia and Ukraine. Moreover, definitive measures have also been imposed on CR from China and Russia. Furthermore, the Commission also recently adopted definitive anti-dumping measures for corrosion resistant steel products, which fall within the HDG product type, coming into the EU from China.

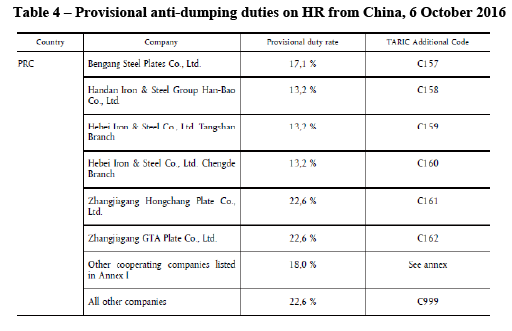

(174) First, with regard to HR products, on 13 February 2016 the Commission initiated an anti-dumping proceeding concerning imports of certain hot-rolled flat products of iron, non-alloy or other alloy steel originating in China. The Commission first imposed provisional anti-dumping measures on these products on 6 October 2016, effective from 8 October 2016. (96) The provisional measures are listed in Table 4.

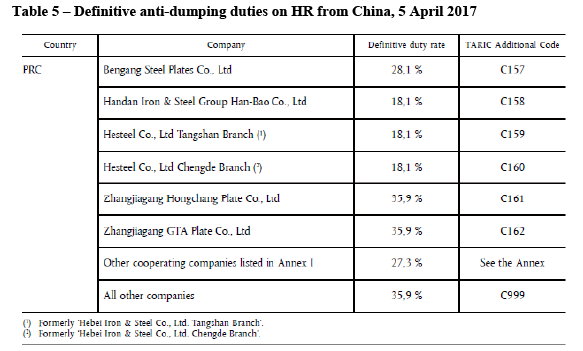

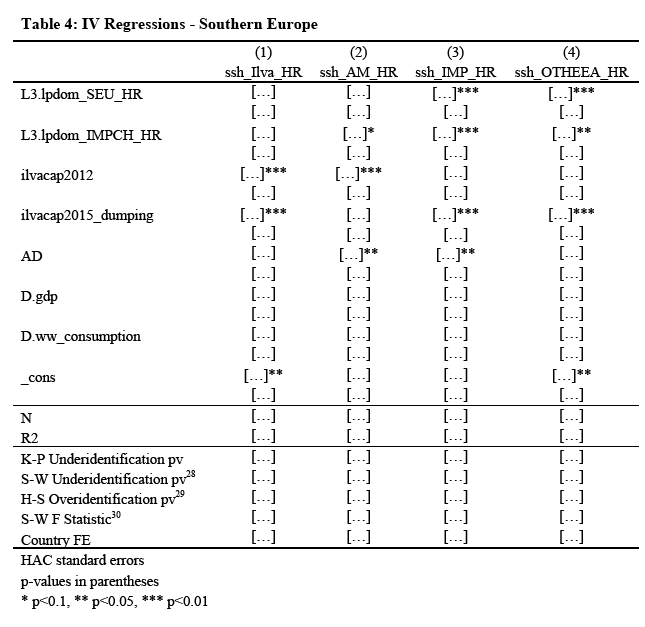

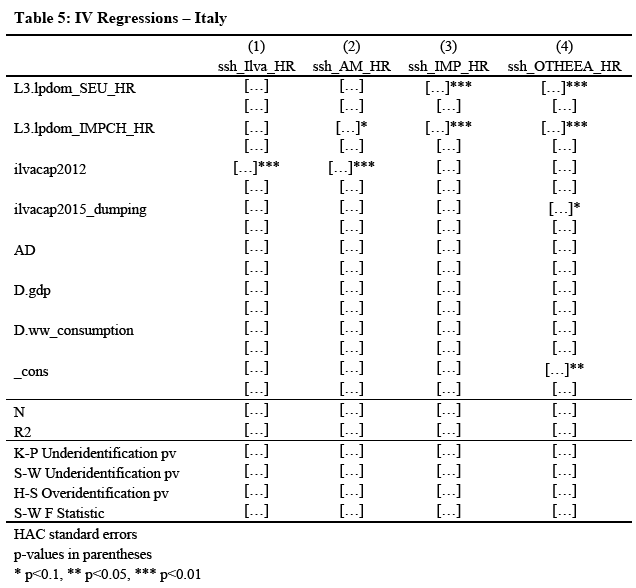

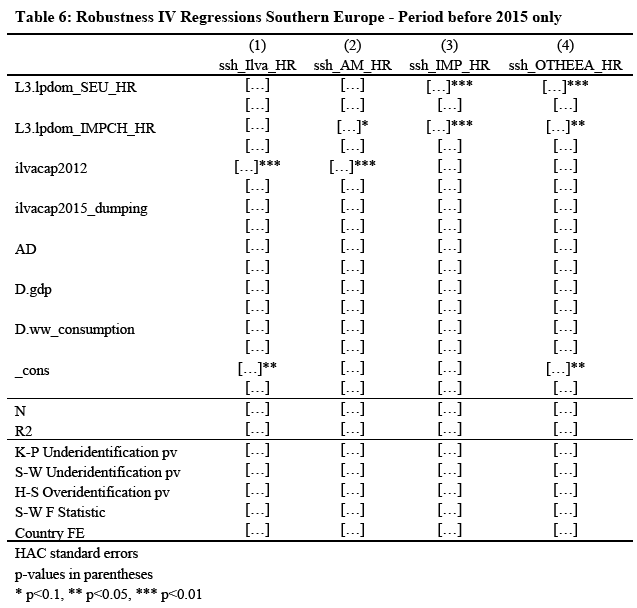

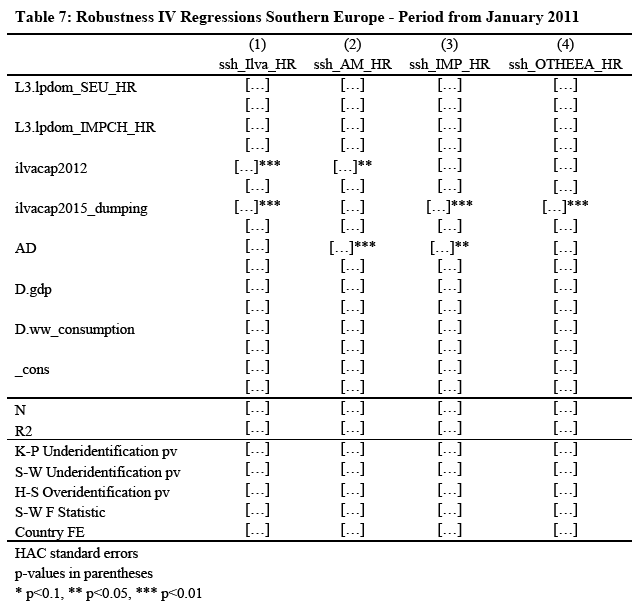

(175) Subsequently, on 5 April 2017, the Commission adopted definitive measures on the concerned HR products from China, effective from 7 April 2017. (97) The definitive measures are listed in Table 5.

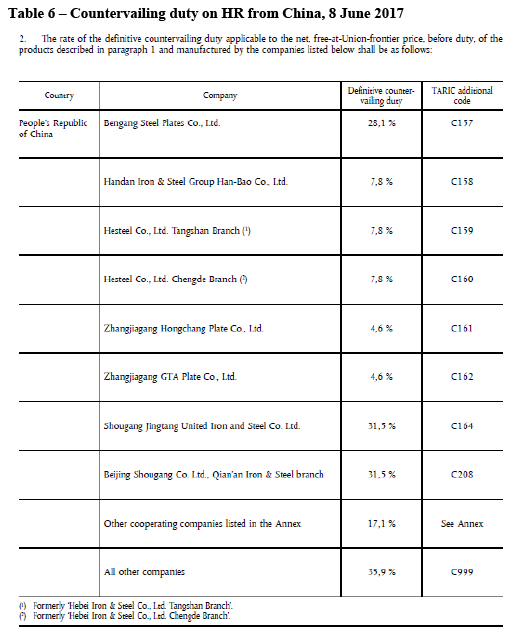

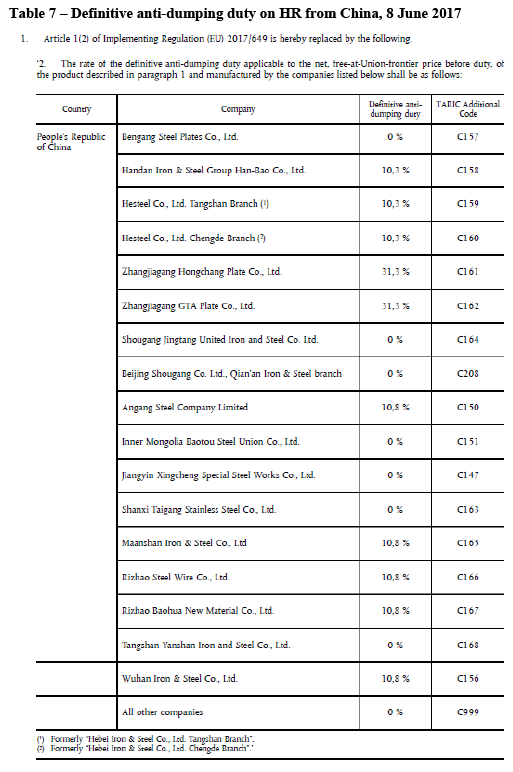

(176) The definitive duties were subsequently amended by Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/969. (98) The amended duties were supplemented by countervailing duties. Both are listed in Table 6 and Table 7.

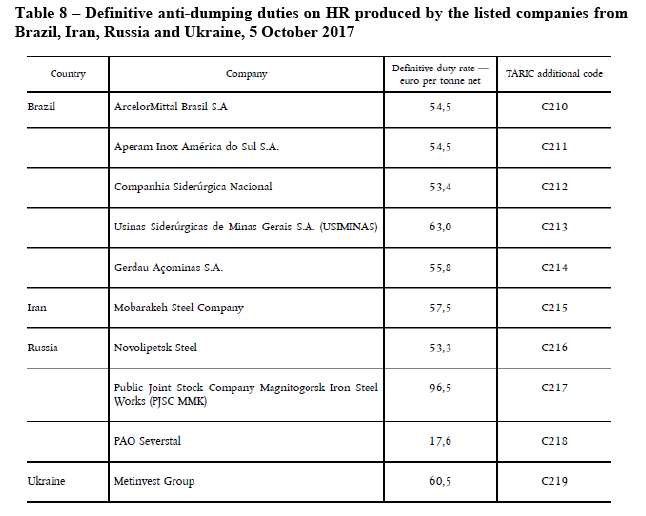

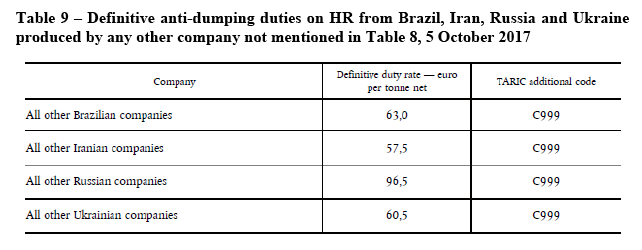

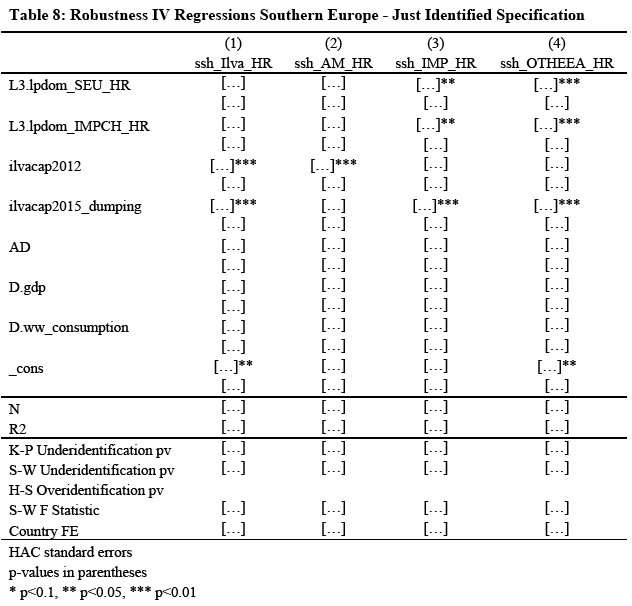

(177) In addition to the anti-dumping investigation relating to HR from China, on 7 July 2016 the Commission initiated an anti-dumping proceeding concerning imports of certain hot-rolled flat products of iron, non-alloy or other alloy steel originating in Brazil, Iran, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine. No provisional measures were imposed in this case. On 5 January 2017 imports of the concerned HR products from Russia and Brazil have been made subject to registration. (99) As a result of the Commission's investigation, on 5 October 2017 definitive anti-dumping measures were adopted with regard to HR products originating in Brazil, Iran, Russia and Ukraine, effective from 7 October 2017, whilst the investigation on imports of HR from Serbia was terminated. (100) The definitive measures on HR from Brazil, Iran, Russia and Ukraine are listed in Table 8 and Table 9.

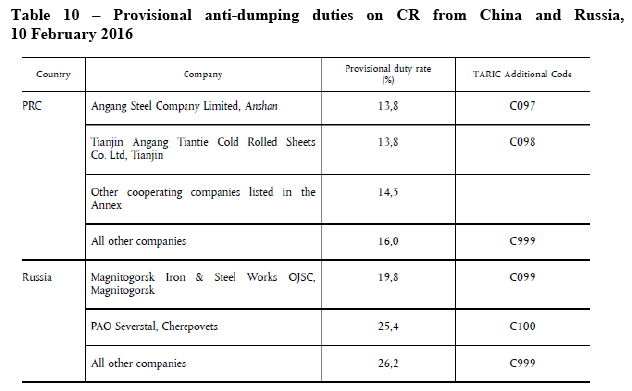

(178) Second, with regard to CR products, on 14 May 2015 the Commission initiated an anti-dumping proceeding concerning imports of certain cold-rolled flat steel products originating in China and Russia. These products were subsequently made subject to registration on 11 December 2015. (101) On 10 February 2016 the Commission imposed provisional anti-dumping duties on the CR products concerned. (102) The provisional measures, effective from 13 February 2016, are listed in Table 10.

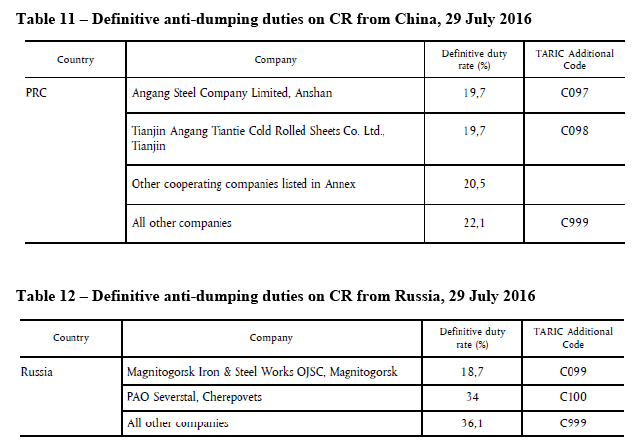

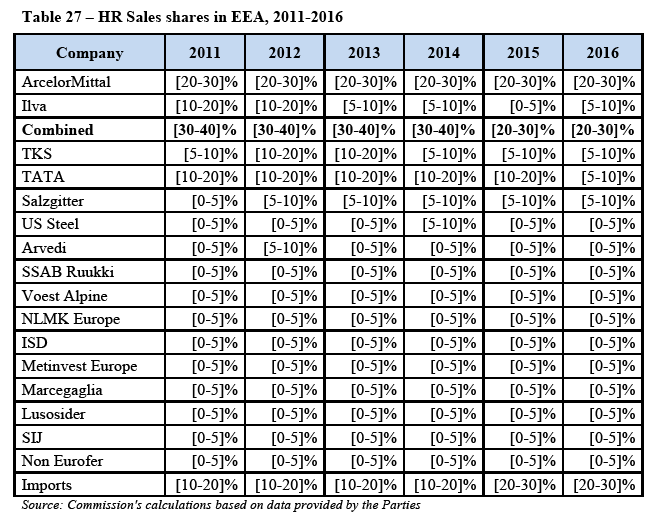

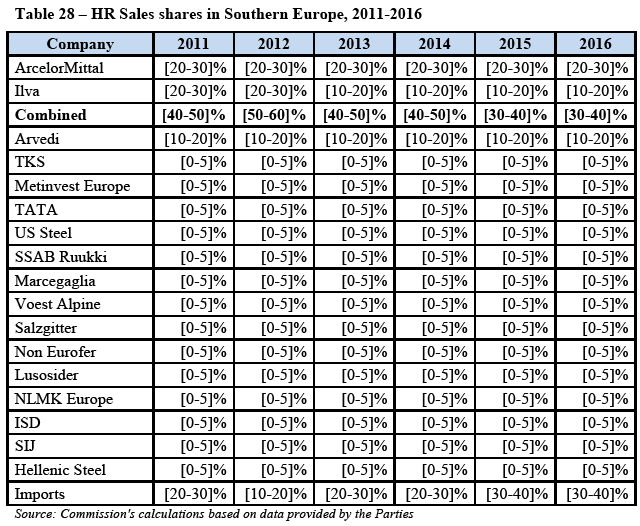

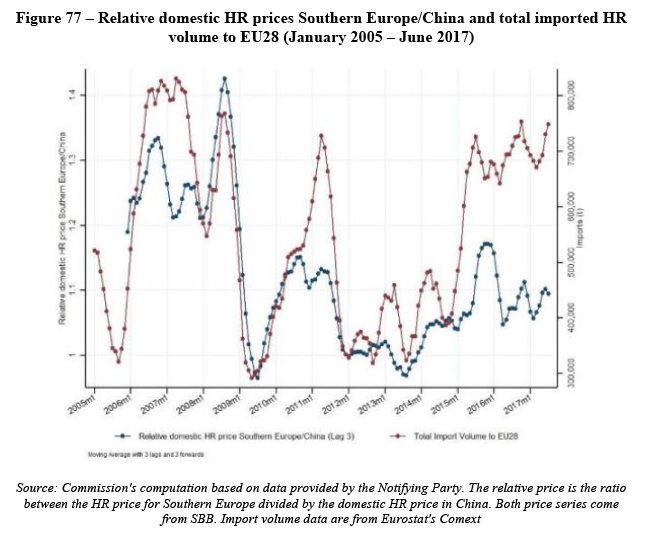

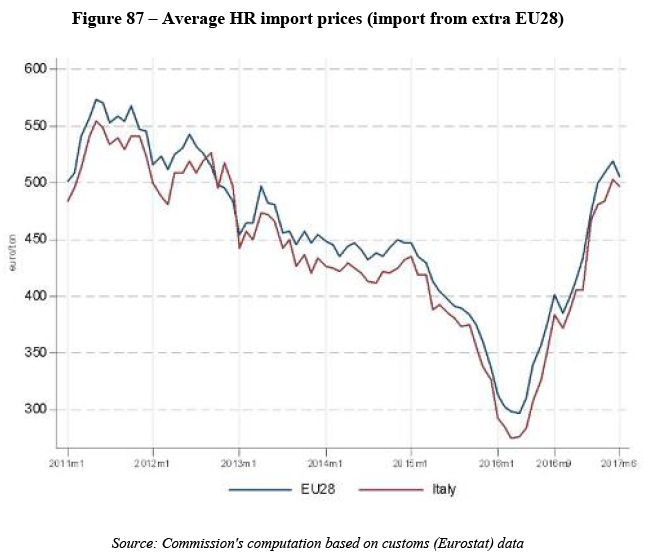

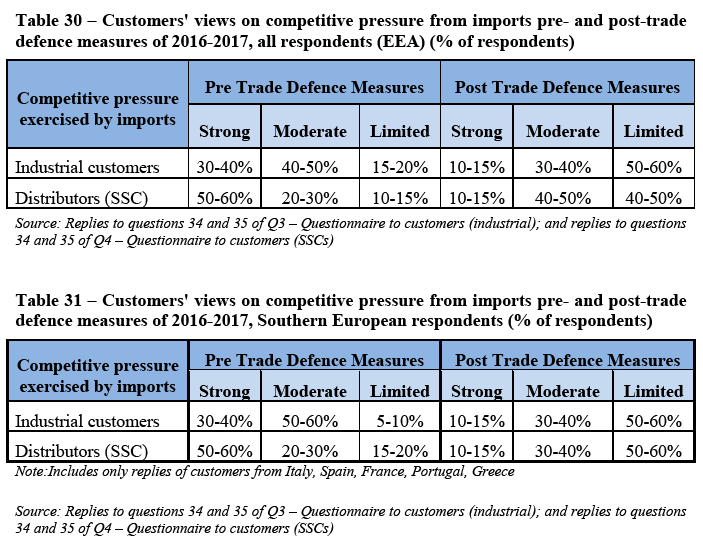

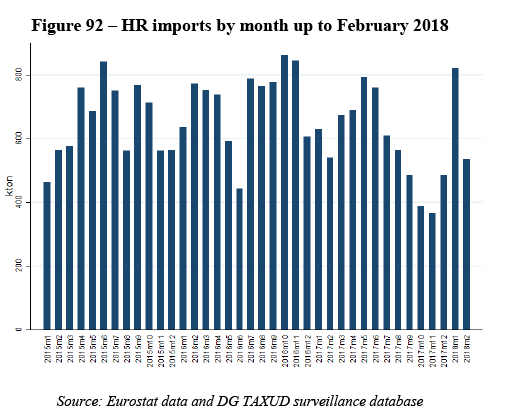

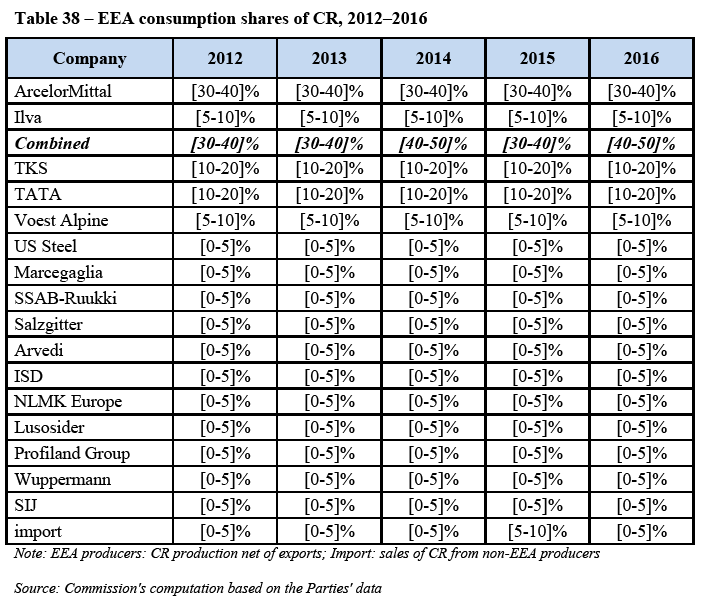

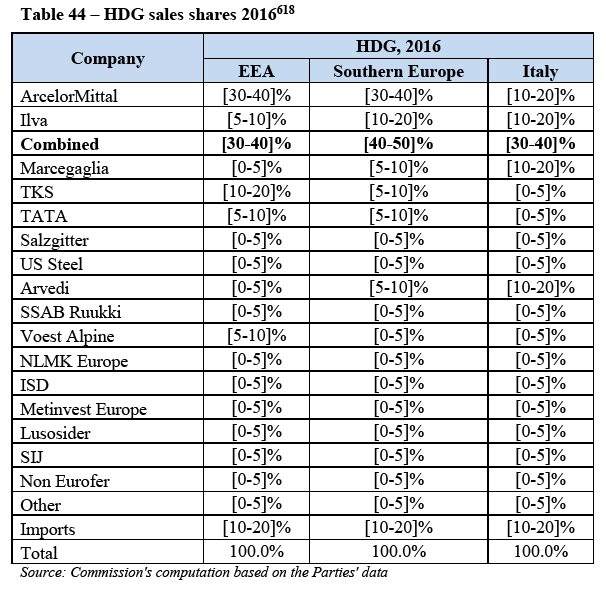

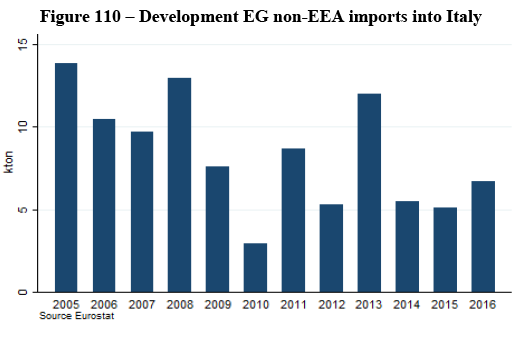

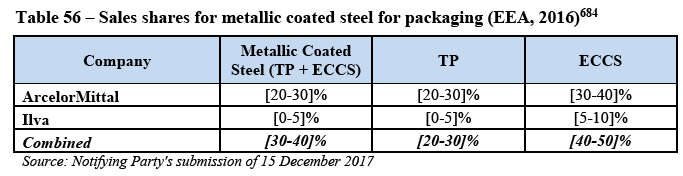

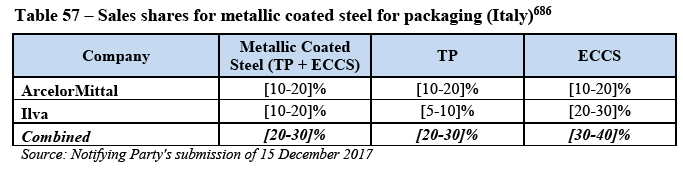

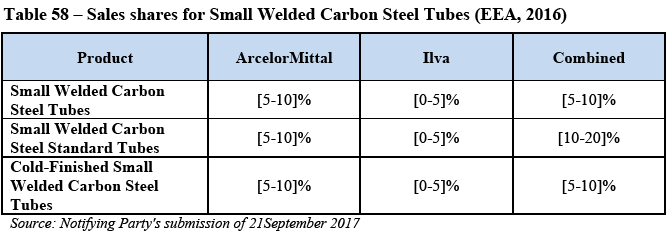

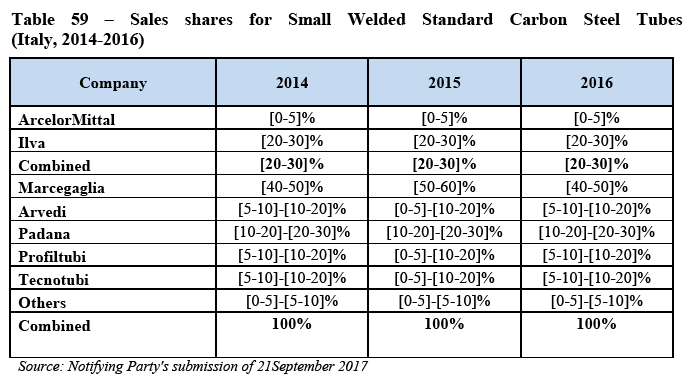

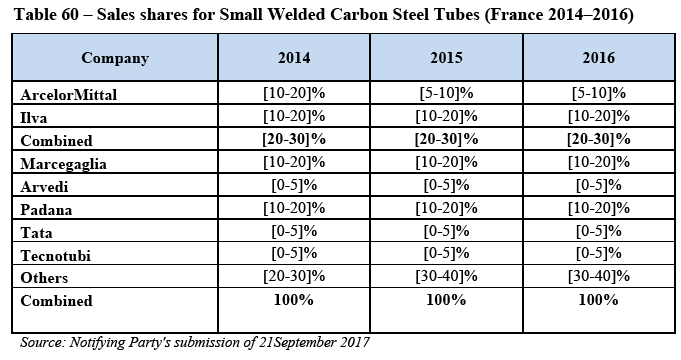

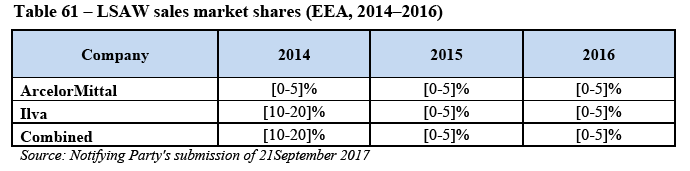

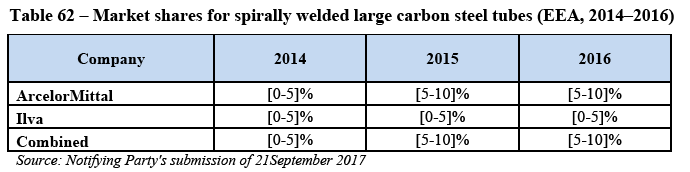

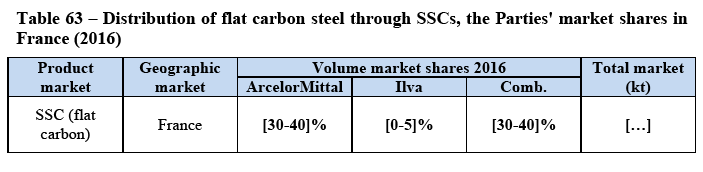

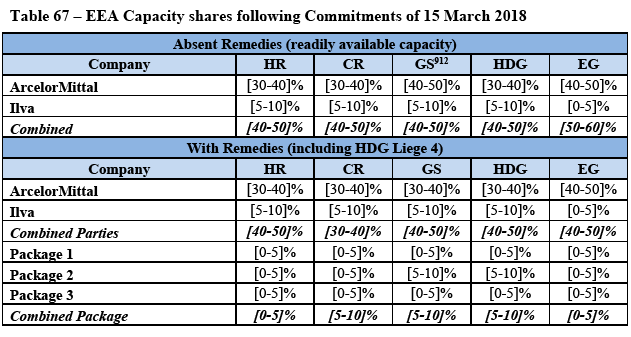

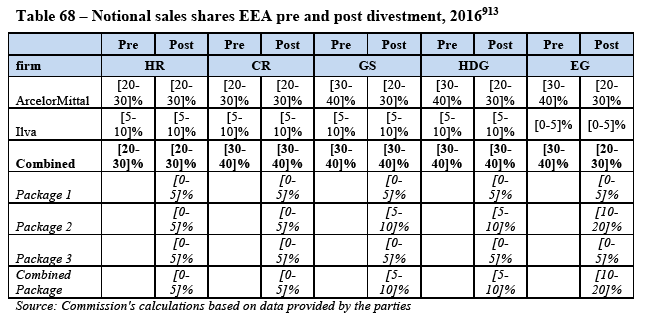

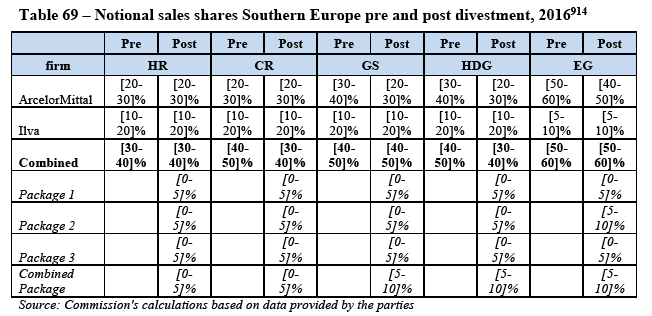

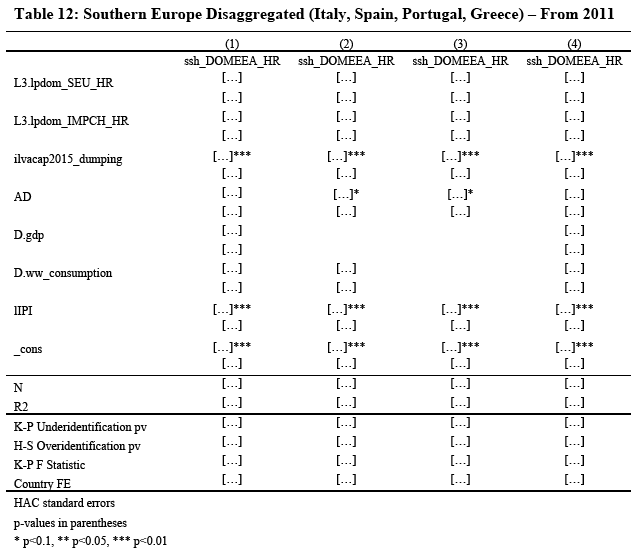

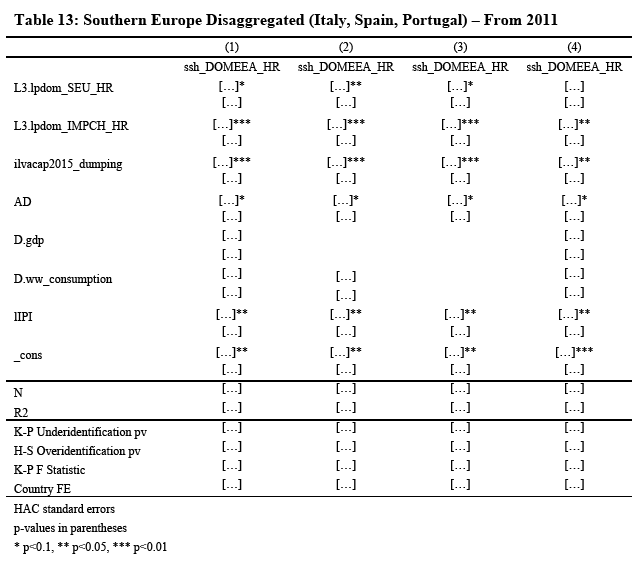

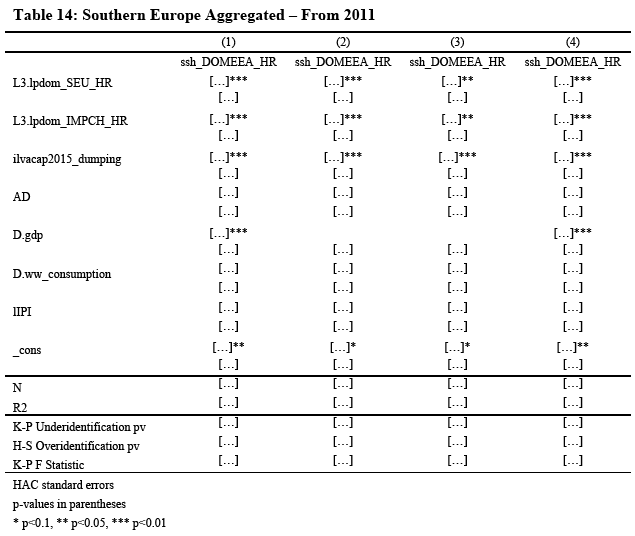

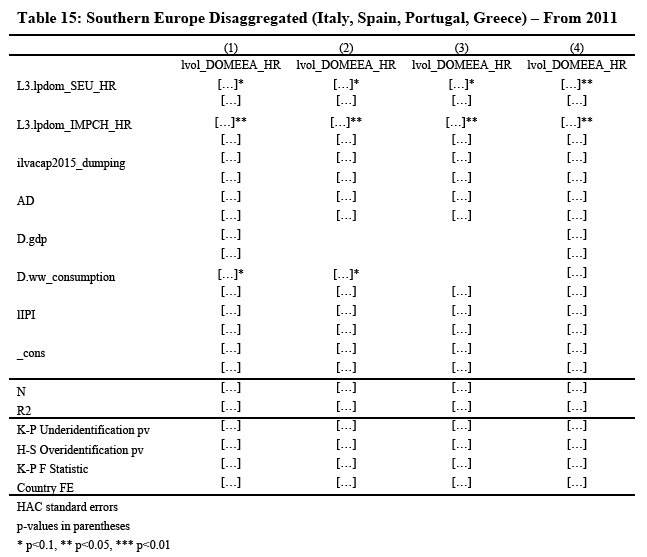

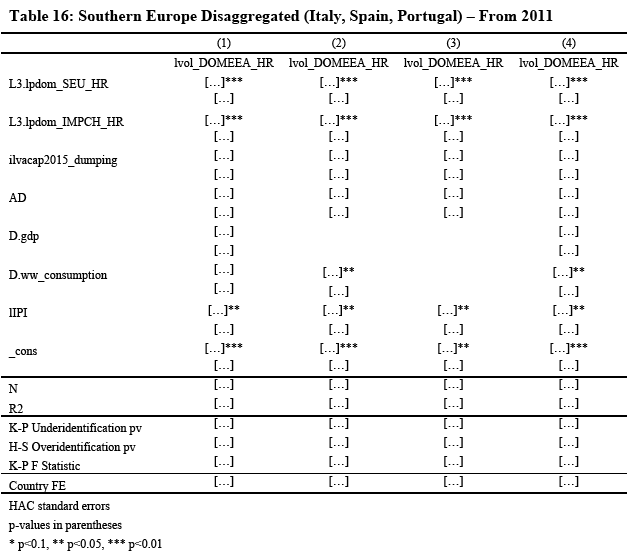

(179) Following the provisional measures and further investigation, definitive measures on CR from China and Russia were imposed on 29 July 2016. (103) The definitive duties, effective from 5 August 2016, are listed in Table 11 and Table 12.