Commission, September 21, 2020, No M.9495

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

FORTENOVA GRUPA / POSLOVNI SISTEMI MERCATOR

Subject: Case M.9495 – FORTENOVA GRUPA / POSLOVNI SISTEMI MERCATOR

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 17 August 2020, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which Fortenova grupa d.d. (‘Fortenova’, Croatia) acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control over Poslovni Sistemi Mercator (‘Mercator’, Slovenia), by way of purchase of shares (the ‘Proposed Transaction’).3 Fortenova is referred to hereinafter as the ‘Notifying Party’ and Fortenova and Mercator are referred to together as ‘Parties’.

1. THE PARTIES

(2) Fortenova is a Croatian based entity established for the purposes of the restructuring of Agrokor d.d. (‘Agrokor’, Croatia). On 1st April 2019, as part of a debt-for-equity restructuring, the business and all the assets of Agrokor with the exception of Mercator were transferred to Fortenova. At the same time, the business and assets of Agrokor’s subsidiaries were transferred to Fortenova’s subsidiaries.

(3) According to the Notifying Party, Mercator was not transferred to Fortenova with the rest of Agrokor’s business and assets on 1st April 2019 because of potential mandatory takeover implications that required further consideration and thus more time to prepare the business for transfer.4 As a result, Mercator remained with Agrokor.

(4) Fortenova’s core business is the production and supply of food and beverages and the retail supply of groceries/daily consumer goods (and related products). It operates through three core business segments: (a) the retail and wholesale segment, which encompasses the retail supply of groceries/daily consumer goods; (b) the food production and supply segment, which includes the production and supply of mineral water, ice cream, oil, margarine and mayonnaise; and (c) the agriculture segment, which encompasses activities in the production of cereal, oils crops, cheese, fresh fruit and vegetables, as well as the operation of livestock farms.

(5) Mercator is headquartered in Slovenia. Together with its subsidiaries, it is primarily active in the retail supply of daily consumer goods to end consumers via a network of retail stores, notably in Slovenia.

2. THE OPERATION AND THE CONCENTRATION

(6) The Proposed Transaction forms part of the broader restructuring of Agrokor , the scope and objective of which is to maintain the operational business of the Agrokor group by substantially reducing its debt burden to a sustainable level so as to ensure that the restructured group (i.e., Fortenova) has the capacity to fulfil its liabilities in the long term on the basis of a lasting strengthened equity capital basis.

(7) On 6th April 2017, the Croatian Parliament passed the Law on the Procedure of Extraordinary Administration in Companies of Systemic Importance for the Republic of Croatia (the “CSI Extraordinary Administration Law”). The CSI Extraordinary Administration Law came into force on 7th April 2017 and on the same day Agrokor filed a petition to commence extraordinary administration proceedings (the “Extraordinary Administration”).

(8) The Extraordinary Administration procedure is overseen by the Extraordinary Administrator in charge of restructuring Agrokor and negotiating the terms set out in the Settlement Plan of Agrokor Creditors (the “Settlement Plan” 5). With a view to implementing the Settlement Plan, the Extraordinary Administrator created several entities consisting of an ultimate holding company in the form of a Dutch Stichting, Fortenova STAK, and various subsidiaries including Fortenova.

(9) The Proposed Transaction is carried out in accordance with the terms of the Settlement Plan and a letter of intent entered into by Agrokor and Fortenova on 15 July 2019. The Proposed Transaction will result in Fortenova exercising sole control over Mercator after acquiring the controlling 69.57% equity stake in Mercator held by Agrokor.

(10) The Proposed Transaction therefore constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

(11) In contrast, the operation whereby, on 1st April 2019, Agrokor’s equity holders exchanged their existing debt in Agrokor for shares/depositary receipts in Fortenova STAK and, concomitantly, the businesses and assets of Agrokor (except for Mercator) were transferred to Fortenova, was not notifiable under the Merger Regulation. In effect, as Fortenova could not be considered an undertaking when it acquired control over Agrokor’s assets and businesses, control over the latter was not acquired by “one or more undertakings” or by “one or more persons already controlling at least one undertaking”, within the meaning of Articles 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

(12) Likewise, the operation whereby Agrokor originally acquired a controlling stake in Mercator was not notifiable under the Merger Regulation because the relevant sale and purchase agreement was entered into prior to Croatia’s accession to the EU on 1st July 2013, at a time when Agrokor’s EU turnover was below the turnover thresholds provided for in Articles 1(2)(b) and 1(3)(d) of the Merger Regulation.

3. EU DIMENSION

(13) In 2019, Fortenova and Mercator achieved a combined aggregate worldwide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million6 (Fortenova: EUR 3 167 million, Mercator: EUR 2 167 million). Each of them also achieved an EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Fortenova: EUR […] million, Mercator: EUR […] million), yet they do not achieve more than two-thirds of their aggregate EU-wide turnover within one and the same Member State.

(14) The notified operation therefore has an EU dimension within the meaning of Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. RELEVANT MARKETS

(15) Fortenova and Mercator are both active throughout the supply chain of daily consumer goods, namely in the production and supply, procurement, wholesale supply and retail supply of daily consumer goods. Within the EEA, Fortenova has a large presence in Croatia and some activities in Slovenia, though not at retail level. In contrast, Mercator has a large presence in Slovenia, notably at retail level, and some de minimis wholesale activities and adjacent procurement activities in Croatia.

(16) The Parties’ activities overlap horizontally to a limited extent with regard to the procurement and wholesale supply of daily consumer goods. In addition, vertical overlaps between the Parties’ activities arise primarily in Slovenia between Fortenova’s activities upstream in the production and supply of daily consumer goods and Mercator’s activities downstream in the retail supply of daily consumer goods.

4.1. Relevant product markets

4.1.1. The production and supply of daily consumer goods

(17) The Proposed Transaction concerns the production and supply of daily consumer goods and agricultural products, the procurement of daily consumer goods, the wholesal supply of daily consumer goods and the retail sale of daily consumer goods.

4.1.1.1. Previous cases

(18) The Commission has segmented the production and supply of daily consumer goods market based on narrow product categories, thus as those discussed in further detail below in Sections 4.1.1.1 (A) to (G).

(19) In the past the Commission also indicated7, that private label and branded products may within each category belong to the same market as there is a tendency for the customers to switch from one group of the products to another; but left the question ultimately open.

(20) In so far as food products are concerned, in past decisions the Commission has consistently distinguished between the production and supply of food products dedicated to the retail sector and the production and supply of food products to the food service sector (i.e. the supply to out-of-home eating, institutional catering and the quick service restaurants sectors).8

(A) Production and supply of frozen foods including ice cream

(21) The Commission’s decisional practice concerning the frozen food sector distinguishes between ice cream products and other frozen food products.9

(22) The Commission has previously distinguished between industrial ice cream (which is usually manufactured in specialised facilities and its consumption site is independent of the production site and comprises a broad range of sweetened frozen desserts consisting of a number of major components, all of which are mixed according to different recipes, packaged and stored before delivery to downstream customers) and artisanal ice cream (which is produced by street vendors or bakers who produce themselves their ice cream, as well as ice cream parlours and small companies generally with less than 10 employees, which offer their ice cream products at a local level).10

(23) Within the market for industrial ice cream the Commission has previously11 identified distinct product markets for each of: (i) take-home ice cream, potentially further segmented by branded vs. private label (although the results of market investigations have been inconclusive regarding such a further segmentation); (ii) impulse ice-cream; (iii) catering ice cream (i.e. ice cream sold to restaurants, hotels etc., and which is mainly sold and delivered in bulk to be consumed at the catering location). The Commission has not previously considered it appropriate to further segment the market for artisanal ice cream.12

(B) Production and supply of edible oils

(24) In previous decisions, the Commission has segmented the broader edible oils sector into the following sub-segments: (i) crude seed oil; (ii) refined seed oil which can be sold in bulk (“BRSO”); and (iii) refined seed oil which is packaged for sale to end- users (“PRSO”).13

(25) The Commission has also considered that olive oils are distinct from seed oils, and treated the former as forming a distinct product market. As the Proposed Transaction will only potentially give rise to affected markets with respect to the production and supply of PRSO and olive oil, the correct market definition to adopt with respect to the supply of other oils has not been discussed further.

(26) In its previous decisions, the Commission did not consider it necessary to further segment the market for the production and supply of olive oil.

(27) As regards PRSO, the Commission previous market investigations have indicated that it may not be necessary to define separate markets based on different types of seeds.14

(C) Production and supply of vegetable (plant-based) fats

(28) The Commission has previously concluded that vegetable fats (namely, margarine) are not in the same market as packet butter, given the extent to which prices would need to increase before inducing customers to switch from margarine to butter.15

(29) In its previous decisions, the Commission did not consider further segmentations of the market for the production and supply of margarine.

(D) Production and supply of cheese/dairy spreads

(30) In previous decisions, the Commission has considered dividing the cheese market according to category of cheese, that is, spreadable, fresh, soft, semi-hard and hard cheese.

(31) The Commission has also considered further segmentations based on type of presentation (e.g. slice, fixed weight and variable weight), type of milk used and protected geographic status.16

(32) As noted above, the Commission has previously treated spreadable cheese (cream cheese and soft processed) as forming a distinct product market, and has undertaken a competitive assessment on this basis in a number of cases.17

(33) In its previous decisions, the Commission did not consider a further segmentation of the market for the production and supply of cheese/dairy spread.

(E) Production and supply of cold sauces

(34) The Commission’s past decisional practice18 has defined a separate market for cold sauces (which are typically used to add flavour to cooked food) from hot sauces (which are employed during the cooking process).

(35) As regards cold sauces, the Commission has consistently further segmented the market by type of cold sauce due to differences in characteristics and use of the products. As such, the Commission has defined separate markets for the supply of each of ketchup, mayonnaise, mustard, salad dressing and other cold sauces.19

(F) Supply of meat products

(36) In its previous cases, the Commission has drawn a distinction between the supply of fresh meat (i.e. fresh, frozen or minced meat that has not undergone any further processing, that is, no other ingredients or spices have been added, nor has the meat been cooked, smoked or dried) and processed meat (i.e. meat products containing external ingredients such as salt, spices, being raw, dried smoked or cooked).20

(37) The Commission has previously concluded that the supply of fresh meat for further processing and the supply of fresh meat for direct human consumption constitute two separate markets. The Commission has also segmented this market based on type of fresh meat.21

(38) The Commission’s decisional practice with respect to processed meat has been to segment the market by narrow product categories. Whilst leaving the precise market definition open, the Commission has grouped processed meat products into the following categories:22· Raw cured products – that is, products that will be cooked by the consumer prior to eating. Some of the products may have already received some heat treatment (i.e. by smoking) but will still be viewed by consumers as being raw. This group consists of bacon, larger pieces of ham and loin cured or smoked.· Processed meat for cold consumption (cold cuts or charcuterie) – that is, products that will not be cooked by the consumer before eating, but will be consumed as is (typically in slices or dices). This category includes dried ham, cooked ham and salami for sandwiches, which can also be used in salads and cold starters.· Canned meat – that is, fully preserved meats in selected metal cans or glasses, which have a prolonged shelf life at ambient temperatures. This product group includes canned ham, luncheon meat, cocktail sausages and semi-prepared meats with gravy and other ingredients.· Cooked sausages – that is, sausages which are cooked and consumed directly as sausages, typically after heating in water, frying or grilling (including sausages for hotdog stands).· Pates and pies – that is, pies, which are commuted and heat-treated products (baked or boiled) often including ingredients such as liver.· Ready prepared dishes and components (convenience products) – that is, those products which typically requires a higher degree of preparation for consumption, either being the complete meal itself or being a significant component of this (e.g. meatballs, burgers etc.). Such products are often sold in frozen state but can also be sold as chilled products.

(39) The Commission has also left open further sub-segmentations within the above categories (e.g. by type of raw product, such as, raw sausages, bacon etc.) and whether such product types should be further sub-divided according to the meat type (i.e. pork, beef etc.). 23

(G) Production and supply of non-alcoholic beverages

(40) The Commission has consistently defined a separate market for the supply of alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages (“NABs”). As regards the latter, the Commission has further distinguished between the supply of carbonated soft drinks (“CSDs”) and non-carbonated soft drinks (“NCSDs”).

(41) As regards NCSDs, the Commission indicated in past cases24 that it may be appropriate to further segment NCSDs into mineral waters, fruit juices, iced/ready- to-drink (“RTD”) teas and energy and sports drinks, although it ultimately left the question on such segmentation open, apart from distinguishing bottled water (comprising different types of still and carbonated waters, such as mineral water, spring water and treated water) from other NABs25, and from RTD teas.26

(42) The Commission has to date left open the question whether bottled water should be further segmented (including into still and carbonated water).27

4.1.1.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(43) The Parties consider that most of the food products they produce and supply (including edible oils, margarine, cold sauces, cheese, meats and NABs) are relatively homogeneous. Therefore, customers will focus more on price and volume than on the brand itself when purchasing such food products.28 More specifically, the Notifying Party considers that in particular the following food products are characterised by homogeneity: take-home ice cream and fresh meat. 29

(44) In addition, the Notifying Party also considers that the edible oil and margarine markets display a certain level of homogeneity, but that increasingly at least a certain segment of customer (i.e. those that place a premium on perceived health benefits) are placing a greater emphasis on product characteristics (e.g. margarine with added omega-3 fatty acids due to the perceived cardiovascular benefits).30

(45) However, Fortenova also points out that there are other food products - most notably impulse ice cream, iced tea, bottled water, carbonated soft drinks and cold sauces (mayonnaise and ketchup) – in relation to which customers place great importance on the brand. According to the Notifying Party these food products are typically (although not always) associated with lower private label penetration.31

(46) The Notifying Party did not take a view on other aspects of the product market definition in relation to the production and supply of daily consumer goods.

4.1.1.3. The Commission’s assessment

(47) In the Commission’s market investigation, a clear majority of market participants who took a view agreed that the production and supply of food products dedicated to the retail distribution sector, on the one hand, and the production and supply of food products dedicated to the food service sector (i.e. the supply to out-of-home eating, institutional catering and the quick service restaurants sectors), on the other hand, constitute separate product markets with different supply-demand dynamics.32

(48) In light of the above, in line with previous cases and for the purposes of this decision the Commission considers that the production and supply of food products dedicated to the retail distribution sector and the production and supply of food products dedicated to the food service sector constitute separate product markets.

(A) Production and supply of frozen foods including ice cream

(49) In the Commission’s market investigation, a majority of market participants who took a position agreed with the finding in previous cases that the production and supply of ice cream products, on the one hand, and other frozen food products, on the other hand, constitute different product markets with different supply-demand dynamics.33

(50) Further, a majority of market participants who took a view agreed in the market investigation that the production and supply of industrial ice cream, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the production and supply of artisanal ice cream constitute different product markets with different supply demand dynamics.34

(51) Moreover, a majority of market participants who took a view in the market investigation agreed that the production and supply of (i) take-home ice cream, (ii) impulse ice cream, and (iii) catering ice cream constitute different product markets with different supply demand dynamics.35 One market participant commented in this regard: “Yes the packaging is completely different, the basic composition of the products is different and also the expiration dates themselves.”36

(52) In light of the above and for the purposes of this decision the Commission considers that the production and supply of ice creams constitutes a separate product market from the production and supply of other frozen food. The Commission further considers that the production and supply of industrial ice cream constitute a separate market from artisanal ice cream. Further, there are strong indications that the production and supply of (i) take-home ice cream; (ii) impulse ice cream and (iii) catering ice cream constitute separate product markets. The exact market definition can, however, be left open. The Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of this market definition.

(B) Production and supply of edible oils

(53) In the Commission’s market investigation, a clear majority of market participants who took a view agreed with the finding in previous cases that the production and supply of (i) crude seed oil; (ii) BRSO; and (iii) PRSO constitute separate product markets with different supply-demand dynamics. Similarly, a clear majority of market participants who took a position in the market investigation agreed that olive oils, on the one hand, and seed oils, on the other hand, constitute separate product markets with different supply-demand dynamics.37

(54) As regards a potential further segmentation by seed type within the production and supply of PRSO, the market investigation is inconclusive. A slight majority of market participants who took a view in the market investigation agreed that a further segmentation by different seed type within the production and supply of PRSO is not necessary.38 One producer/supplier explained in this regard that demand-side substitutability was high. However, another producer/supplier brought forward that supply-side substitutability was limited “(…) due to different sources of purchase, prices and availability of seeds to obtain PRSO.”39

(55) In light of the above, in line with previous cases and for the purposes of this decision the Commission considers cases that the production and supply of (i) crude seed oil;(ii) BRSO; and (iii) PRSO constitute separate product markets. Similarly, the Commission considers that the production and supply of seed oil is separate from the production and supply of olive oil. A further segmentation of the three identified markets for the production and supply of seed oil by seed type cannot be excluded. The exact market definition can, however, be left open. The Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of this market definition.

(C) Production and supply of vegetable (plant-based) fats

(56) In the Commission’s market investigation, a majority of market participants who took a view agreed with the previous Commission finding that the production and supply of margarine constitutes a separate product market with its own supply- demand dynamics.40 Further, all market participants who expressed a view further explained that they did not consider a further market segmentation with respect to the production and supply of margarine as appropriate.41

(57) In light of the above and for the purposes of this decision the Commission finds that the production and supply of margarine constitutes a separate product market.

(D) Production and supply of cheese/dairy spreads

(58) In the Commission’s market investigation, a clear majority of market participants who took a clear position agreed that the production and supply of (i) spreadable, (ii) fresh, (iii) soft, (iv) semi-hard and (iv) hard cheese each constitute separate product markets with different supply-demand dynamics.42 One producer and supplier explained in this regard, that the preservation production and marketing policies were different.43

(59) As regards a potential further segmentation based, for instance on type of presentation (e.g. slice, fixed weight and variable weight), type of milk used and protected geographic status, responses from market participants were inconclusive. Some said they agreed with a further segmentation, while some said that they disagreed with a further segmentation.44

(60) In relation to the production and supply of spreadable cheese, all of the market participants who took a view in the market investigation agreed with the finding in previous cases, that the production and supply of spreadable cheese constitutes a distinct product market with different supply-demand dynamics from other dairy products and that no further segmentation is appropriate.45

(61) In light of the above and for the purposes of this decision the Commission considers that the production and supply of (i) spreadable, (ii) fresh, (iii) soft, (iv) semi-hard and (iv) hard cheese each constitute separate product markets. A further segmentation by type of presentation, type of milk used and/or protected geographic market can be excluded, with the exception of spreadable cheese, where the market investigation suggests that no further segmentation is appropriate.

(E) Production and supply of cold sauces

(62) A vast majority of market participants who took a view in the market investigation agreed with previous Commission findings (see Section 4.1.1.1 (E)) that ketchup46 and mayonnaise47 each constitute distinct product markets with specific supply- demand dynamics. One wholesale supplier stated in this regard: “„Ketchup“ has a special status within the other cold sauces. The production lines are normally separated from other products (e.g. from the production of natural cold sauces) also the production quantities are normally much higher.”48

(63) The Commission therefore finds that, as in previous cases, for the purposes of this decision, the production and supply of ketchup and the production and supply of mayonnaise each form distinct product markets.

(F) Supply of meat products

(64) In the Commission’s market investigation, all of the market participants who expressed a view agreed with the finding in previous cases that the supply of fresh meat and the supply of processed meat constitute distinct product markets with different supply-demand dynamics.49 Similarly, all of the market participants who took a clear position responded that the supply of fresh meat for further processing and the supply of fresh meat for direct human consumption constitute two separate markets.

(65) In light of the above and for the purposes of this decision the Commission considers that the supply of fresh meat for human consumption is a separate market from the production and supply of processed meat for human consumption. Further segmentations cannot be excluded. However, irrespective of a further segmentation, the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as regards its compatibility with the internal market.

(G) Production and supply of non-alcoholic beverages

(66) In the Commission’s market investigation, a majority of market participants who took a view responded that the production and supply of carbonated water, still water and flavoured water each constitute distinct product markets with different supply- demand dynamics, with one supplier and producer expressly mentioning different consumer habits, pricing and packaging strategies, as well as different growth rates.50

(67) In light of its past decisions and for the purposes of this case, the Commission considers that within the broader market for the production and supply of non- alcoholic drinks, there are separate product markets each for the production and supply of CSDs and for the production and supply of NCSDs. The Commission further considers in line with precedents that bottled water constitutes a separate product market. While the market investigation indicates that the production and supply of carbonated water, still water and flavoured watermight constitute separate product markets, in absence of serious doubts as to the compatibility of the transaction with the internal market under any alternative market definition, the precise product market definition can be left open in the present case.

(H) Branded vs private label products.

(68) With regard to a possible distinction between the production and supply of branded products and the production and supply of private label products, like in previous market investigations (see Section 4.1.1.1 above), there are strong indications that the production and supply of branded and the production and supply of private-label products are part of the same product markets.

(69) A clear majority of suppliers and producers do consider that both production and supply categories belong to the same product markets across the above mentioned plausible product markets for daily consumer goods.51 Some producers/suppliers explained that, on the supply-side, the same manufacturing plants were producing the same branded and non-branded products, while on the demand-side consumers were less and less distinguishing between the two categories.52 One producer/supplier noted: “In particular, there is a strong competitive relationship between branded and non-branded/private label products, with the latter exerting significant competitive pressure on the former. It is increasingly difficult for consumers to distinguish whether products were manufactured by a manufacturer of branded goods or whether they are being sold as a private label product, (…).”53

(70) However, the Commission notes that a clear majority of both wholesale suppliers and retail suppliers responded that the two categories belong to different product markets,54 with one retail supplier explaining that private label products usually target customers with lower income and another retail supplier referring to the supply-side stating that production facilities could be specialised and separated for private label products.55

(71) In light of the above and for the purposes of this decision, the Commission notes that although there are strong indications that branded and private label products belong to the same production and supply markets across product categories, the results of the market investigation are mixed. However, the exact market definition can be left open. The Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of this product market definition.

4.1.2.The procurement of daily consumer goods

4.1.2.1. Previous cases

(72) In previous decisions, the Commission has considered a distinct market for the procurement of daily consumer goods, comprising the purchase of daily consumer goods by customers such as wholesalers, retailers and other firms from upstream producers and suppliers.56

(73) In its decisional practice57, the Commission, considered a segmentation of that market into 19 relevant product markets corresponding to different types of goods, namely: (i) meat and sausages; (ii) poultry and eggs; (iii) bread and pastries; (iv) dairy products; (v) fresh fruits and vegetables; (vi) beer; (vii) wine and spirits; (viii) non-alcoholic beverages; (ix) hot beverages; (x) confectionery; (xi) basic food products (xii) preserved food; (xiii) frozen foods; (xiv) baby foods; (xv) pet foods;(xvi) body care articles (e.g. creams, lotions) and cosmetics (make-up and perfumes); (xvii) detergents, polishes and cleaning products; (xviii) other drugstore products; and (xix) other non-food products usually found in supermarkets (e.g. newspapers, magazines, entertainment).58 In one precedent59, the Commission also considered a different segmentation of the procurement market for daily consumer goods into 2360 product categories. However, this precedent, which related to Romania, included products typically sold in hypermarkets but not in supermarkets (e.g., large domestic electrical appliances, hifi/ audio, TV/video). According to the Form CO, Fortenova and Mercator operate supermarkets and discounters. Thus, the sub-segmentation into 19 product categories is more appropriate for the purposes of this decision.

(74) The Commission also previously considered, but ultimately left open, whether a further distinction should be made between different sales channels, such as food- retailing, specialised trade, delicatessen, cash and carry stores and other wholesalers, drugstores and export trade.61

4.1.2.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(75) The Notifying Party took no view on the product market definition as regards the procurement of daily consumer goods.

4.1.2.3. The Commission’s assessment

(76) The Commission’s market investigation showed that the findings of past cases in relation to the procurement of daily consumer goods are still appropriate.

(77) A vast majority of market participants who expressed a view responded that there is a specific market for the procurement of daily consumer goods including food products to customers such as wholesalers, retailers and other firms from upstream producers and suppliers.62

(78) Likewise, the market investigation showed that an overwhelming number of market participants agree with the segmentation into 19 different procurement markets according to different product groups with different supply-demand dynamics found in previous cases, namely: (i) meat and sausages; (ii) poultry and eggs; (iii) bread and pastries; (iv) dairy products; (v) fresh fruits and vegetables; (vi) beer; (vii) wine and spirits; (viii) non-alcoholic beverages; (ix) hot beverages; (x) confectionery; (xi) basic food products (xii) preserved food; (xiii) frozen foods; (xiv) baby foods; (xv) pet foods; (xvi) body care articles (e.g. creams, lotions) and cosmetics (make-up and perfumes); (xvii) detergents, polishes and cleaning products; (xviii) other drugstore products; and (xix) other non-food products usually found in supermarkets (e.g. newspapers, magazines, entertainment).63

(79) Further, a clear majority of market participants who took a view expressed that different sales channels such as food-retailing, specialised trade, delicatessen, cash and carry stores and other wholesalers, drugstores and export trade constituted distinct procurement markets with different supply-demand dynamics.64 One producer/supplier explained that on the demand side, the customers were different for each sales channels, and they bought different quantities, different assortments of products and required different customer service i.e. the way the order is placed, the way it is made up and the way that delivery is made.65

(80) In light of the above and for the purposes of this case, the Commission considers that there are strong indications for a segmentation of the procurement markets by the nineteen product categories mentioned above. Similarly, there are strong indications for a segmentation by sales channel. The exact market definition can, however, be left open. The Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of this market definition.

4.1.3. The wholesale supply of daily consumer goods

4.1.3.1. Previous cases

(81) Within the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods market a number of further potential segmentations have previously been considered by the Commission (but ultimately left open), that is: (i) segmentation into food and related non-food products; (ii) segmentation by mode of supply (e.g. delivered wholesale, contract distribution and cash & carry); (iii) segmentation by temperature range (i.e. frozen, chilled/fresh and ambient); (iv) segmentation by geographic scope of customer (i.e. national or independent); (v) segmentation by end-customer type (i.e. quick service, full service, pubs/coffee shops, hotels/accommodation, business & industry, other commercial, health, education, other institutional); and (vi) segmentation by product category (e.g. fruit & vegetables, poultry, savoury bakery, sweet bakery, dairy, fish, confectionary, desserts, meat, all other).66 However, for reasons of full supply-side substitutability, the Commission concluded in Sysco/Brakes that further segmentation by temperature range and end-customer type is not appropriate (at least in the context of that transaction).67

4.1.3.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(82) The Notifying Party took no view on the product market definition as regards the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods.

4.1.3.3. The Commission’s assessment

(83) A clear majority of market participants who expressed a view68 confirmed the finding of previous Commission decisions, that the market or markets for the wholesale supply of non-food products and the market or markets for the wholesale supply of food products are each distinct markets with their on supply-demand dynamics.

(84) A clear majority of market participants who took a clear position69 further responded that they considered a segmentation by product category (e.g. fruit & vegetables, poultry, savoury bakery, sweet bakery, dairy, fish, confectionary, desserts, meat, all other) as appropriate. A market participant explained in this regard: “Purchasing is influenced by the specifics of each category (different logistics routes, other sales channels, other methods storage, hygiene requirements, temperature regimes).”70

(85) The market investigation is not wholly conclusive as to a further segmentation by mode of supply (e.g. delivered wholesale, contract distribution and cash&carry). There are some indications that this distinction might be appropriate. A majority of market participants who took a view said that they considered the different modes of supply to be distinct markets with different supply-demand dynamics. However, a notable number of respondents also said they did not agree with this distinction. 71

(86) In light of the above and in line with previous Commission decisions, the Commission considers for the purposes of this decision, that there are indications that there are separate product markets for different product categories of wholesale supply of daily consumer goods (e.g. fruit & vegetables, poultry, savoury bakery, sweet bakery, dairy, fish, confectionary, desserts, meat, all other). A segmentation by mode of supply cannot also not be excluded. The exact market definition can, however, be left open since the Transaction would not give rise to serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under the narrowest possible product market definition.

4.1.4. The retail supply of daily consumer goods

4.1.4.1. Previous cases

(87) In its previous decisional practice the Commission has consistently held that within the retail segment a separate product market exists for the sale of daily consumer goods mainly carried out by retail outlets such as hypermarkets, supermarkets and discount chains (so called “modern distribution channels”).72 These retail outlets offer consumers a basket of fresh and dry foodstuffs and non-food household consumables sold in a supermarket environment.

(88) In addition, in past decisions the Commission has also considered that modern distribution channel outlets belong to a different product market to other retailers, such as specialised outlets (e.g. butchers, bakers, etc.) and service stations. These other retailers fulfil a specialist or convenience function and the variety and range of products in these more traditional store types would be narrower than in hypermarkets and supermarkets, which means that they belong to a different product market.73

4.1.4.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(89) The Notifying Party took no view on the product market definition as regards the procurement of daily consumer goods.

4.1.4.3. The Commission’s assessment

(90) A clear majority of market participants who expressed a view in the market investigation responded that within retail supply a separate product market exists for the sale of daily consumer goods mainly by retail outlets such as hypermarkets, supermarkets and discount chains (so-called “modern distribution channels”) distinct from other specialised retailers74.

(91) In light of this and in line with previous Commission decisions, the Commission finds for the purposes of this decision that the market for the retail supply of daily consumer goods through hypermarkets, supermarkets and discount chains constitutes a separate product market.

4.2 Relevant geographic markets

(92) Within the EEA, Fortenova is mainly active in Croatia, where it has significant activities in the retail supply of daily consumer goods (via Konzum) and in the production and supply of food products (via Ledo, Jamnica, Zvijezda, Belje and PIK Vrbovec).

(93) Mercator in contrast has a limited presence in Croatia (total revenue in the financial year 2018: EUR […] and in the financial year 2019 of EUR […]) in the wholesale of raw and intermediate daily consumer goods, procurement of daily consumer goods and the production and supply of food products. Mercator, however, has a strong presence in Slovenia where Fortenova is not active in the retail supply of daily consumer goods but has some activities upstream in the production and supply of daily consumer goods. Outside of Croatia and Slovenia, the Parties’ activities in the EU are limited.

4.2.1. The production and supply of daily consumer goods

4.2.1.1. Previous cases

(A) Production and supply of ice cream

(94) From a geographic perspective, the Commission has consistently considered that the relevant geographic markets for all ice cream products are national in scope due to legislative differences, national and sub-national trends in sales and distribution, and differences in consumers’ habits, products recipes and packaging.75

(B) Production and supply of edible oils

(95) As noted above (See Section 4.1.1.1(B) above), the Commission has segmented the edible oils sector into the three sub-segments, namely crude seed oil, BRSO and PRSO. In addition, the Commission has also considered that olive oils are distinct from seed oils and treated the former as forming a distinct product market.

(96) The Commission in previous decisions left open the precise definition of the geographic scope of the PRSO markets.76 However, the market investigation in previous cases revealed elements indicating that supply of PRSO to the retail channel can be regarded as national in scope with possible cross-border effects, encompass neighbouring regions, as well as other areas likely to supply without significant cost differences.77

(C) Production and supply of vegetable (plant-based) fats

(97) The Commission has not assessed the geographic market definition for the supply of margarine in its previous decisions.

(D) Production and supply of cheese/dairy spreads

(98) The Commission has defined, in its previous decisions, the market for the production and supply of cheese as being national in scope.78

(E) Production and supply of cold sauces

(99) In previous decisions, the Commission has defined the relevant cold sauces markets as being national in scope, due to significant differences in sales channels, retailers, logistics, brands, and eating habits between the various EEA countries.79

(F) Supply of meat products

(100) As noted above (See Section 4.1.1.1(F) above), in its decisional practice the Commission has drawn a distinction between the supply of fresh meat and processed meat.

(101) From a geographic perspective, the Commission has in past cases indicated that fresh meat for direct human consumption is likely to be national in scope, whereas the supply of fresh meat for further processing is national or wider than national, although this was ultimately left open.80

(102) As regards processed meat, the Commission has previously concluded that the market for processed meat is national in scope. Such delimitation would be justified on the basis that suppliers are able to price discriminate between different Member States. 81 The national scope of the market is also supported by the fact that the markets are still to a large extent characterised by national consumer preferences and recipes for national “specialties” (e.g. “Kasseler” in Germany, “Chorizo” in Spain etc.),82 as well as due to differences in terms of consumption habits and preferred national brands.83 However, the possibility that the market may be broader than national in scope for individual product groups of processed meat under specific circumstances has not been excluded.84

(G) Production and supply of non-alcoholic beverages

(103) From a geographic perspective, the Commission has consistently defined the geographic market for NABs as being national in scope, particularly in light of differentiated consumer preference between countries, the importance of national brands, significance of marketing and advertising expenses, and the significance of transport costs in relative terms to the final value of the product.85

4.2.1.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(104) The Notifying Party took no view on the definition of the geographic market as regards the production and supply of daily consumer goods.

4.2.1.3. The Commission’s assessment

(A) Production and supply of frozen foods

(105) As regards the geographic scope of the market for the production and supply of all ice cream, a majority of market participants who took a position indicated that the market(s) are national in scope.86 One producer/supplier of ice cream explained that there were differences in consumer habits and preferences between countries.87

(106) Consequently, and in line with its findings in previous decisions, the Commission concludes that for the purposes of this decision the geographic market or markets for the production and supply of all ice cream is/are national in scope.

(B) Production and supply of edible oils

(107) As regards the geographic scope of the market for the production and supply of edible oils, responses from market participants were not wholly conclusive. There are indications that the market or markets for the production and supply of edible oils might be wider than national. While a notable number of market participants said that the markets were national in scope, a majority of market participants did not agree that each country constitutes a separate market for the production and supply of edible oils with different supply-demand dynamics, with several explaining that the market was broader than national, EEA-wide or even global. 88

(108) Furthermore, the market investigation was not conclusive as to whether the production and supply of PRSO is national in scope or wider than that. Half of the respondents who expressed a view said it was national while the other half said that the geographic market was wider than national.89

(109) For the purposes of this decision, the Commission leaves open whether the market or markets for the production and supply of edible oils are national or wider than national. Irrespective of the geographic market definition for the market or markets for the production and supply of edible oils, the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market.

(C) Production and supply of margarine

(110) With regard to the geographic scope of the market for the production and supply of margarine, responses from market participants were not fully conclusive. All market participants who expressed a view indicated that the market or markets for the production and supply of margarine are at least national in scope. Market participants, however, did not take a clear view on whether the geographic scope of the market for production and supply of margarine is national or wider than national. There are indications that the market or markets might be wider than national as a slight majority of a limited number of responses considered the market or markets for the production and supply of margarine to be wider than national.90

(111) For the purposes of this decision, Commission concludes that the market or markets for the production and supply of margarine are at least national in scope. As, irrespective of this geographic market definition, the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market, the Commission leaves open whether the market or markets for the production and supply of margarine might be wider than national in scope.

(D) Production and supply of cheese/dairy spreads

(112) As regards the geographic scope of the market for the production and supply of cheese, responses from market participants were inconclusive. While half of the market participants who expressed a view said that each country constituted a separate market for the production and supply of cheese due to different supply- demand dynamics, the other half of market participants who took a clear position disagreed, with one stating they were at least regional and two others stating they were EEA-wide.91

(113) As, irrespective of this geographic market definition, the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market, the Commission leaves open the geographic market definition for the markets for the production and supply of cheese.

(E) Production and supply of cold sauces

(114) As regards the geographic scope of the market for the production and supply of cold sauces, responses from market participants were not wholly conclusive. A slight majority of respondents who took a clear position did not agree that each country constitutes a separate geographic market for cold sauces, with several of them indicating, that the markets might be wider than national.92

(115) In light of the above, the Commission concludes that for the purposes of this decision, the markets for cold sauces are at least national in scope. The Commission leaves open whether the markets might be wider than national, as the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of this market definition.

(F) Supply of meat products

(116) With regard to the markets for the supply of meat for human consumption, the market investigation confirms that the markets for the supply of fresh meat for human consumption are national in scope. All of the market participants who expressed a view agreed with this.93

(117) As regards the supply of processed meat for human consumption, the market investigation is not wholly conclusive. A majority of respondents agreed in response to one question that the markets for the supply of processed meat are wider than national. 94 One producer/supplier explained the difference was due to the different expiry dates. Because of this, processed meat could be distributed more broadly.95 However, in a response to another question with a limited response rate, market participants agreed with a national scope.96

(118) In light of the above, the Commission concludes for the purposes of this decision, that the markets for the supply of fresh meat for human consumption are national in scope and the markets for the production and supply of processed meat for human consumption are at least national in scope. The Commission leaves open whether the markets for the production and supply of processed meat might be wider than national as the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of this market definition.

(G) Production and supply of non-alcoholic beverages

(119) With regard to the geographic scope of the market for the production and supply of bottled water, all of the market participants who expressed a view said that the market or markets for the production and supply of bottled water are national in scope.97

(120) In light of the clear outcome of the market investigation and in line with its previous decisions, the Commission concludes that the market or markets for the production and supply of bottled water are national in scope.

4.2.2. The procurement of daily consumer goods

4.2.2.1.Previous cases

(121) In previous decisions, the Commission has consistently defined the procurement market as being national in scope. The main reasons underlying this approach have been that consumer preferences relate to national products and suppliers generally negotiate on a national level.98

4.2.2.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(122) The Notifying Party took no view on the definition of the geographic market as regards the procurement of daily consumer goods.

4.2.2.3. The Commission’s assessment

(123) In the Commission’s market investigation, a clear majority of market participants who took a clear position said that each country constitutes a separate market for the procurement of daily consumer goods with different supply-demand dynamics99, with some providing reasons such as different consumer preferences as well as the prominence of local brands.100

(124) The Commission notes that, despite the clear general agreement with a national scope of the procurement markets for daily consumer goods, explanations of several market participants indicate that at least some of the markets are increasingly becoming wider than national.101

(125) In light of the above, the Commission concludes that for the purposes of this decision it finds that the markets for the procurement of daily consumer goods are at least national in scope. However, a wider market definition cannot be fully excluded. The Commission ultimately leaves open whether the market is wider than national, as the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of the market definition.

4.2.3. The wholesale supply of daily consumer goods

4.2.3.1.Previous cases

(126) From a geographic perspective, the Commission has previously considered the market for the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods to be national in scope.102 The one potential exception is the cash & carry mode of supply, where the Commission has previously considered the market to be smaller than national (i.e. local) in scope.103

4.2.3.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(127) The Notifying Party took no view on the definition of the geographic market as regards the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods.

4.2.3.3. The Commission’s assessment

(128) As regards the market or markets for the wholesale of daily consumer goods, the market investigation confirms that these markets are national in scope. A clear majority of market participants who expressed a view said that each country constitutes a separate product market for the wholesale of daily consumer goods.104

(129) As regards a possible exception for the cash & carry mode of supply, which the Commission previously considered to be smaller than national in scope, a majority of market participants who responded to the market investigation said it is likewise national in scope. 105

(130) In light of the above and in line with previous decisions, the Commission finds that, for the purposes of this decision, the markets for the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods (with the possible exception of the cash & carry mode of supply) are national in scope. In light of the feedback from Slovenian market participants, the Commission further considers that the plausible Slovenian wholesale market(s) for the cash & carry mode of supply is(are) national in scope. However, for the purposes of this decision, the Commission leaves open whether the markets for the wholesale of daily consumer goods through the cash & carry mode of supply outside Slovenia may be smaller than national in scope. Irrespective of this market definition, the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market.

4.2.4. The retail supply of daily consumer goods

4.2.4.1. Previous cases

(131) The geographic market for the retail supply of daily consumer goods has generally been considered by the Commission to be local in scope, as delineated by the boundaries of a territory where the outlets can be reached easily by consumers (typically based on radii of approximately 20 to 30 minutes driving time).106

4.2.4.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(132) The Notifying Party took no view on the definition of the geographic market as regards the retail supply of daily consumer goods.

4.2.4.3. The Commission’s assessment

(133) As regards the geographic scope of the markets for the retail supply of daily consumer goods in Slovenia, the Commission’s market investigation showed that the markets are most likely local in scope as delineated by the boundaries of a territory where the outlets can be reached easily by consumers (typically based on radii of approximately 20 to 30 minutes’ driving time). A majority of market participants who expressed a view said that the Slovenian retail supply markets for daily consumer goods should be defined as local.107 A retail supplier notes in this regard: “Slovene customers are less likely to travel a long distance to buy the daily consumer goods. The density of retail stores in Slovenia is amongst highest in EU”.108

(134) However, the Commission notes that a meaningful number of respondents consider the Slovenian markets for the retail supply of daily consumer goods to be national.

(135) In light of the above, for the purposes of this decision, the Commission considers that the Slovenian markets for the retail supply of daily consumer goods are likely local in scope. However, a national scope of the Slovenian retail supply markets for daily consumer goods cannot be excluded. It can ultimately be left open whether the markets are local or national in scope as the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market irrespective of this market definition.

5. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

(136) In Croatia, due to some very limited wholesale activities of Mercator, the Proposed Transaction gives rise to plausible horizontally affected markets as regards the production and supply of bottled water dedicated to the food service sector, as regards the production and supply of ice cream dedicated to the food service sector, as regards the procurement of daily consumer goods and as regards the wholesale of daily consumer goods. Similarly, the Proposed Transaction gives rise to vertical overlaps in Croatia between Mercator’s wholesale activities vis-à-vis Fortenova’s production and supply activities upstream and vis-à-vis Fortenova’s retail supply activities in five plausible local markets downstream.

(137) However, due to the very limited size of Mercator’s activities in Croatia, the horizontal overlaps and the increments are de minimis with regard to all plausible affected markets.109 The HHI deltas are all below the 250 threshold, and almost all below 150, and are therefore unlikely to raise competition concerns according to Paragraphs 20 and 21 of the Horizontal Merger Guidelines. There are two overlaps as regards the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods in Croatia, where the pre- merger market share of Fortenova would be above 50%, namely bottled water (with […]%) and iced tea (with […]%), thereby falling outside the scope of Paragraphs 20 and 21 of the Horizontal Merger Guidelines in spite of an HHI delta below 150. However, the Commission notes that these market shares provided by the Parties relate to food product categories that are relatively narrow compared to the broader markets the Commission previously found with regard to the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods. The available market shares, therefore, are likely to overestimate the market shares on the likely broader relevant markets. Second, the wholesale supply activities of Mercator as regards both bottled water and iced tea account for less than one percent market share both on a volume and value basis (de minimis).110 As such, substantive competition concerns can be excluded due to a lack of closeness of competition and the de minimis increments that would result from the Transaction.

(138) Similarly, regarding the possible vertical overlaps in Croatia, the activities of Mercator all account for less than one percent market share (de minimis). In this respect, the Commission notes that Fortenova’s brands/products have a substantial share in Croatia in a number of product categories principally in respect of impulse ice cream ([…]%), margarine ([…]%), mayonnaise ([…]%) and bottled water ([…]%).111 However, even if Fortenova were to be deemed to possess market power in one or more of the upstream markets, input foreclosure would not be a credible strategy for Fortenova post-Transaction. Fundamentally, the Commission considers that the addition of Mercator is too small to change the ability and/or incentives of Fortenova in supplying downstream competitors, and that therefore the risk of input foreclosure is extremely limited. Mercator’s limited downstream increment in Croatia (<1% on both a volume and value basis) means that customer foreclosure concerns can be dismissed given that post-Transaction there will clearly remain sufficient economic alternatives in the downstream market for the upstream rivals to sell their competing daily consumer goods and agricultural products to.

(139) Similar considerations apply to incentives regarding input and customer foreclosure in relation to the overlap with Fortenova’s retail activities downstream. Input foreclosure concerns can be excluded on the basis that the addition of Mercator’s de minimis (<1%, on both a volume and value basis) upstream share would not alter the ability and/or the incentive of the merged entity to engage in an input foreclosure strategy at the wholesale level. As regards customer foreclosure, whilst there are five plausible local Croatian markets (counties) in which Fortenova’s retail share exceeds 30% (their shares range from […]% to […]%)112, the fact that retailers typically procure goods on a national basis (particularly those large downstream retailers that compete with Fortenova in Croatia – e.g. Lidl, Kaufland, Tommy and Spar) means that customer foreclosure strategy could not be effectively limited to these plausible local markets. Furthermore, Mercator’s transit wholesale business in Croatia typically focuses on supply of a limited range of products to food processors and downstream retailers are in any event not an important source of demand for this business.113 Finally, one of the key features of running a successful downstream retail business is to ensure that customers are provided with a wide-range of products and brands (so as to meet the diverse needs and preferences of consumers), as such, it is highly unlikely that Fortenova would cease to procure products from competing upstream wholesalers.

(140) Therefore, in conclusion, the Commission finds that the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market in relation to Croatia.114 Therefore, the Croatian markets are not assessed further in this decision.

(141) In Slovenia, the Proposed Transaction gives rise to horizontally affected markets with respect to the markets for the procurement of food products/daily consumer goods and plausible sub-markets thereof, as well as plausible sub-markets for the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods. Furthermore, the Proposed Transaction gives rise to a number of vertically affected markets in Slovenia because of Fortenova’s upstream activities in the production and supply of daily consumer goods (in particular impulse ice cream) and Mercator’s downstream wholesale supply and retail supply activities.

(142) At the outset, though, as explained in Section 2 above, the target Mercator was already part of the same corporate group together with the Agrokor assets currently controlled by acquirer Fortenova, from 2014 until 1 April 2019 when Mercator was excluded from the Agrokor assets initially transferred to Fortenova as part of the Agrokor debt-for-equity restructuring. The Notifying Party argues that the Transaction essentially re-establishes the status quo prior to 1 April 2019 and that, by construction, the Proposed Transaction cannot significantly affect competition as compared to the previously existing situation. In its view, the Proposed Transaction would merely restore the competitive conditions/status quo that existed until immediately befor 1st April 2019.115 In this respect, the Commission notes that the Commission’s market investigation confirmed that Mercator is indeed integrated already with the other Fortenova assets to a high degree. This prompted many respondents to expect “no change” in the competitive conditions on the relevant markets as a result of the Proposed Transaction. Moreover, as one retailer commented “Mercator is a selfstanding company” and its management has always been “sovereign at taking business decisions and according to our knowledge so shall remain also after its reintegration of the corporate group previously known as Agrokor and now controlled by Fortenova”.116

(143) In light of this, the Commission notes that the outcome of the market investigation tends to support the Notifying Party’s view that merger-specific effects arising from the Proposed Transaction are likely to be limited. However, for the purposes of this decision, the question of the appropriate counterfactual and the materiality of effects can be left open because the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market in any event.

5.1.Horizontal overlaps

(144) In Slovenia, the Proposed Transaction gives rise to horizontally affected markets with respect to the procurement of food products/daily consumer goods and plausible sub-markets thereof and plausible sub-markets for the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods.

5.1.1. Procurement of daily consumer goods

(145) Horizontal overlaps arise in Slovenia in the plausible overall market as well as in several plausible sub-markets for the procurement of daily consumer goods, given that both Parties procure items from upstream daily consumer goods manufacturers in Slovenia for sale in their downstream businesses.

5.1.1.1. Notifying Party’s view

(146) The Parties have based most of their market shares on data contained in reports by Nielsen, an information & measurement company providing market research. These reports discuss Fortenova’s share (and those of competitors) in the affected markets in Croatia and Slovenia for 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019.117

(147) Regarding a plausible segmentation by 19 product categories (see above Section 4.1.2.1 and 4.1.2.3) 118, the Parties were not able to provide market share estimates as they do not possess a reliable third party source of data that would allow them to provide share estimates on this basis. They have provided internal revenue data as the best available data.

(148) The Notifying Party argues that the fact that the Proposed Transaction would only result in a limited increment of less than [0-5]% (on both a volume and value basis), means that substantive competition concerns should not arise.

(149) If the procurement markets were instead to be segmented by sales channel and the sector for the procurement of daily consumer goods to be sold via cash and carry stores (or via other traditional wholesalers) were to be analysed separately, then the Parties’ combined share of approximately [5-10] % in Slovenia would not lead to affected procurement markets for daily consumer goods in Slovenia. Even a further segmentation would not give rise to any horizontally affected markets in light of the again limited increment.119

(150) In relation to narrower markets by product category, the Notifying Party notes that substantive competition concerns could be excluded even putting aside the lack of merger-specific effect stemming from the Transaction on the basis that the likely limited/de minimis increment in each category accounted for by Fortenova would mean that post-Transaction, Mercator’s purchasing position would not be significantly strengthened.120

5.1.1.2. The Commission’s assessment

(151) The Commission considers the Nielsen data credible.

(152) In the plausible overall market for the procurement of daily consumer goods, the combined market share of the Parties would, based on the data provided by the Parties, amount to [20-30] % with a very low increment of [0-5]%.121

(153) A plausible segmentation by sales channels would not lead to any affected markets based on the market share information provided by the Parties.

(154) The internal revenue data of the Parties for the individual products seem to generally support their claim that the increments would be limited/de minimis as the value of the Fortenova procurement activities is low in absolute numbers and compared to Mercator’s activities, see the Table 1 below.

(156) Second, the combined market share of the Parties of [20-30] % remains modest. In particular, the combined market share is just slightly above the threshold of 25%, which would indicate a presumption of compatibility with the internal market according to Paragraph 18 of the Horizontal Merger Guidelines.

(157) Third, in the market investigation market participants did not express concerns in relation to an increased bargaining power of the Parties resulting from the horizontal overlap in procurement activities. On the contrary, asked for the impact of the Proposed Transaction on the market or markets for the procurement of food products to customers such as wholesalers, retailers and other firms in Slovenia, the clear majority of market participants who expressed an opinion responded that there would be no change in relation to price, quality, choice and innovation.123

(158) In conclusion, the Commission finds that the horizontal overlaps in plausible Slovenian markets for the procurement of daily consumer goods do not raise serious doubts in relation to their compatibility with the internal market.124

5.1.2. Wholesale of daily consumer goods

(159) Horizontal overlaps arise in Slovenia in several plausible sub-markets for the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods. This horizontal overlap arises due to:(i) the activities of Fortenova in the direct supply of food products manufactured by upstream Fortenova entities to downstream retailers and wholesalers in Slovenia; and (ii) Mercator’s traditional wholesaling activities (i.e. via its warehousing, cash and carry, franchise and transit distribution channels), via which it distributes Mercator private label products (primarily to franchisees) and other branded products. Fortenova does not have a competing traditional wholesaling business in Slovenia.125

(160) The overall market for the wholesale supply of daily consumer goods in Slovenia is not affected, as the combined market share of the Parties is below 10%.

5.1.2.1. Notifying Party’s view

(161) In addition to the lack of merger-specific impact on competition stemming from the Proposed Transaction, the Notifying Party argues that, in any event, the merged entity would continue to be constrained by a number of producers/manufacturers, as well as suppliers of private label.126

(162) Secondly, the differing nature of the Parties’ activities in the Slovenian wholesale market means that they were unlikely to be viewed by downstream customers as being close competitors. This is because traditional grocery wholesale services, such as those offered by Mercator, are typically used by smaller grocery retailers and small wholesale customers (e.g. small businesses and tradesmen), whereas larger grocery retailers (who typically purchase greater volumes and have more

Bio Today, as well as a long tail of private label and smaller manufacturers who collectively account for in excess of c. [40-50]% of the category (on both a volume and value basis).131 (c) In relation to all industrial ice cream and impulse ice cream, Ljubljanske mlekarne will continue to pose a strong competitive constraint on the Parties post-Transaction (e.g. by value it has an approximate [20-30]% share of the total industrial ice cream category and an approximate [20-30]% share of the impulse ice cream category). Other significant players include Incom, Pro Organika, Mars, Unilever and Nestle who combined account for in excess of c. [10-20]% of both of these categories by value and by volume, approximately [10-20]% of the impulse ice cream category and approximately [5-10]% of the all industrial ice cream category).132 (d) In relation to the wholesale supply of ketchup in Slovenia, the merged entity will continue to face strong competition from number of well-established competitors, including: Felix ([20-30]% volume share and [30-40]% value share), ETA ([5-10]% volume share and [5-10]% value share), Heinz ([0-5]% volume share and [5-10]% value share) and Mutti Fratelli ([0-5]% volume share and ([0-5]% value share).133 (e) As regards the wholesale supply of mayonnaise in Slovenia, the market is dominated by Nestle (via its Thomy brand) with a share of approximately [50- 60]% (by value) and approximately [40-50]% (by volume). Other significant competitors include Unilever ([5-10]% volume share and ([5-10]% value share) and GEA ([0-5]% share by both volume and value).134 (f) Looking at the wholesale supply of dairy/cheese spread in Slovenia, where the Parties would have a combined market share of [20-30]% post-transaction, the key competitors include Ljubljanske (via the MU brand), which in 2018 had a share of [10-20]% (by volume) and [20-30]% (by value), and Mlekarna Celeia (via the Zelene Doline brand), which in 2018 had a share of [5-10]% (by volume) and [10-20]% by value. Private label suppliers accounted for a significant portion of the category, [10-20]% by volume and [10-20]% by value in 2018.135

(168) Fourthly, responses of market participants to the market investigation who said that the geographic markets are wider than national suggest that there is a certain degree of constraints from imports in particular in relation to edible oils, but also in relation to cold sauces like mayonnaise and ketchup, as well as with regard to margarine and impulse and take-home ice cream.136

(169) Fifthly, in the market investigation market participants did not express concerns in relation to the horizontal overlap in the wholesale activities. On the contrary, asked for the impact of the Proposed Transaction on the market or markets for the wholesale supply of food products in Slovenia, the clear majority of market participants who expressed an opinion responded that there would be no change in relation to price, quality, choice and innovation.137 Moreover, none of the market participants who took a view expects a price increase in relation to each of: all industrial ice cream, impulse ice cream, edible oils, mayonnaise, margarine, ketchup and dairy/cheese.138

(170) Sixthly, the difference in the Parties’ activities suggests they are not close competitiors. Mercator’s traditional grocery wholesale supply services are typically used by smaller businesses whereas larger grocery retailers are more likely to purchase groceries directly from producers. As such, given that Fortenova’s wholesale activities in Slovenia are limited to the direct supply channel and Mercator has very limited activities in this space (solely via Mercator-Emba), the Parties do not seem to compete closely.139

(171) In conclusion, the Commission finds that the potential horizontal overlaps in plausible Slovenian markets for the wholesale of daily consumer goods do not raise serious doubts in relation to their compatibility with the internal market.

5.1.3.Conclusion on horizontal overlaps

(172) In light of the above, the Commission finds that the Proposed Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market in relation to horizontal overlaps in Slovenia or on any alternative geographic market definition.

5.2.Vertical overlaps

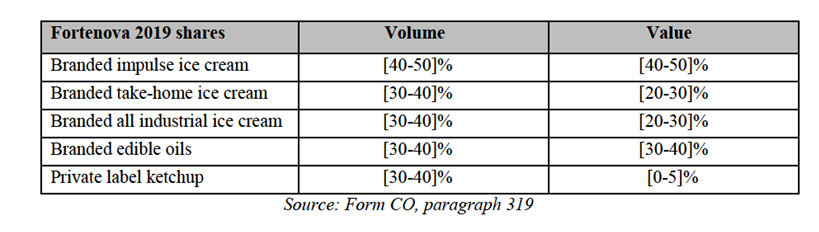

(173) The Proposed Transaction gives rise to vertically affected markets in relation to:(a) Fortenova’s upstream production and supply of impulse ice cream overall, branded impulse ice cream, branded take-home ice cream, branded all industrial ice cream, private label ketchup,branded edible oils, margarine overall, mayonnaise overall, water overall, PRSO and iced tea vis-à-vis Mercator’s wholesale (delivered, cash & carry and franchisee supply) and retail activities downstream in Slovenia; and(b) Mercator’s downstream retail supply of daily consumer goods, bottled water, fresh and processed meat, take-home ice cream, dairy/cheese products, mayonnaise,dairy/cheese spread, ice cream overall, ketchup, edible oils, impulse ice cream, fresh fruit and vegetables, and PRSO vis-à-vis Fortenova’s upstream production and supply activities in Slovenia.

products, and that there is no reason to believe that Mercator coming back under the control of Fortenova will have any meaningful impact on this strategy.144

(A.i) Ability

(183) According to the Parties:(a) It is extremely unlikely that the merged entity would be able to engage in input foreclosure as Fortenova has low market shares in Slovenia with the exception of the impulse ice cream market ([30-40]%).(b) It is highly unlikely that Slovenian retailers would view Fortenova products as being important input, or as “must-have” products.(c) A number of large upstream competitors exist with strong brands in each product market in which Fortenova is active in Slovenia (in particular Ljubljanske Mlekarne in ice cream and Tovarna Olja in oils). In each upstream product category in which Fortenova is active, post-Transaction competing retailers would still have a number of strong alternative suppliers to choose from. 145

(A.ii) Incentive