Commission, March 13, 2020, No M.9434

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

UTC / RAYTHEON

Subject: Case M.9434 – UTC/Raytheon

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) in conjunction with Article 6(2) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 24 January 2020, the European Commission received notification of a concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation resulting from a proposed transaction whereby United Technologies Corporation (“UTC”, USA) intends to acquire control, within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation, of the whole of Raytheon Company (“Raytheon”, USA).3 UTC is referred to hereinafter as the “Notifying Party” and together with Raytheon as the “Parties”. The undertaking that would result from the proposed transaction is referred to as “the merged entity”.

1. THE PARTIES

(2) UTC supplies products and services for the building systems and aerospace industries. In the aerospace industry, via its subsidiary Collins Aerospace Systems (USA), UTC supplies aerospace products and aftermarket service solutions for aircraft manufacturers and operators mainly in the commercial sector but also for integration into military aircraft. Furthermore, via its subsidiary Pratt & Whitney (USA), UTC supplies aircraft engines for the commercial, military, business jet, and general aviation industries, as well as fleet management services and aftermarket maintenance, repair, and overhaul services. UTC also produces, sells, and services auxiliary power units for military and commercial aircraft.

(3) By way of context, UTC currently comprises Otis Elevator Company, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and Collins Aerospace Systems. Before closing the proposed acquisition of Raytheon, UTC has announced its intention to spin off its Otis and Carrier business units into standalone, publicly traded companies. It will then combine the remainder of UTC (consisting of UTC’s aerospace businesses Pratt & Whitney and Collins Aerospace Systems) with Raytheon.

(4) Raytheon is a defence contractor that supplies defence, civil government and cybersecurity solutions with a core focus on missiles and air defence systems, radars and electronic warfare.

2. THE CONCENTRATION

(5) On 9 June 2019, the Parties entered into a binding agreement setting out the terms of the acquisition by UTC of sole control over Raytheon (hereinafter the “Transaction” or the “Concentration”). The Transaction is structured as a merger of a subsidiary of UTC with Raytheon. In consideration for their existing shareholdings, Raytheon shareholders will receive 2.3348 shares in the merged entity for each Raytheon share they hold. Consequently, following the Transaction, UTC shareowners will own approximately 57% of the merged entity, while Raytheon shareowners will own approximately 43%.

(6) Prior to the Transaction, no shareholder holds an interest in any of the Parties’ issued share capital that is sufficient to confer control within the meaning of Article 3 of the Merger Regulation.

(7) It follows that the Transaction would result in a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

3. UNION DIMENSION

(8) The Parties have a combined aggregate worldwide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (UTC: EUR 53 377.1 million, Raytheon: EUR 22 951 million).4 Each of them has a Union-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (UTC: EUR […] million, Raytheon: EUR […] million), but each of them does not achieve more than two-thirds of its aggregate Union-wide turnover within one and the same Member State. The Concentration therefore has a Union dimension pursuant to Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. INTRODUCTION TO THE MILITARY AEROSPACE INDUSTRY

(9) The Transaction brings together UTC’s and Raytheon’s production and supply of systems and components for military airborne platforms, in particular for military aircrafts and precision-guided munities (“PGMs”). Military aircrafts comprise aircrafts designed for military activities, be it combat aircrafts or non-combat aircrafts – i.e. designed for search and rescue, reconnaissance, transport, observation and training. For the purpose of the merger control assessment of the Transaction, this section introduces the Commission's understanding of the basic features of the military aerospace industry.

4.1. Supply chain in the military aerospace industry

(10) The supply chain in the aerospace industry mainly comprises tier suppliers: Tier-1 suppliers, Tier-2 suppliers (and Tier-3 suppliers as the case may be) and aircraft and helicopter manufacturers (referred to as original equipment manufacturers or “OEMs”). Tier-1 suppliers generally have integration capabilities and provide whole systems and equipment. Tier-2 suppliers tend to be active at an upstream stage, supplying components and sub-components for integration into the systems/equipment by either the Tier-1 supplier or the OEM.

(11) Systems and equipment for military aircrafts are purchased by the OEMs or by armed forces and ministries of defence depending on the equipment or system in question. Helicopter/military aircraft OEMs carry out the integration of main systems and equipment in both cases.

4.2. Procurement of US military aerospace equipment

(12) Due to the lower volumes of military aircraft (compared to commercial aircraft) and the complexity of their integrated systems, the procurement process for equipment and systems for military aircraft requires close cooperation between the relevant OEM, system suppliers and the national procurement authorities acting on behalf of the end-users.

(13) The Parties produce military equipment in the US that is ultimately acquired by the US Department of Defence (“US DoD”) and armed forces of EEA countries and other allied countries.

(14) The production of military systems and components in the US is driven by the requirements of the US government and its annual defence budget. The US DoD plans the development of new platforms, defines product specifications, funds development, and manages suppliers. Manufacturers then compete to persuade the US DoD and OEMs that they should select them to develop and supply products for these opportunities.

(15) After developing their defence products in the US, suppliers also market them in US allied countries, including in the EEA. These sales to countries in the EEA largely take place through the US Foreign Military Sales (“FMS”) program and to a limited extent through direct commercial sales (“DCS”).5

(16) The US FMS program is a program administered by the US Defence Security Cooperation Agency (“DSCA”)6 for transferring defence articles, services, and training to US allied countries and international organizations. The US FMS program is funded by administrative charges levied on foreign purchasers.

(17) Under the FMS program, the DSCA serves as an intermediary (usually handling procurement, logistics, and delivery and providing product support and training) between foreign customers and US defence contractors. This framework provides several advantages to foreign customers in US allied countries, such as, inter alia, the US DoD’s procurement infrastructure and purchasing practices and greater economies of scale (although it includes administrative charges). The US FMS program uses a total package approach for its contracts, which means that they include training, spare parts, and other support needed to sustain a system through its first few years.7

(18) Besides administrative charges, purchases via the US FMS program may include nonrecurring costs, which are those one-time costs incurred by the US government in support of research, development, or production of certain major defence equipment. The US DoD may waive nonrecurring costs to allied countries if (i) the sale would significantly advance US government’s interests in standardization with allied armed forces, (ii) the imposition of the charge likely would result in the loss of the sale; or (iii) the increase in quantity resulting from the sale would result in a reduced unit cost for the same item being procured by the US government.

(19) US allied countries, including in the EEA, can also acquire military equipment from US defence manufacturers via DCS.

(20) Cost comparisons between FMS and DCS are often not possible as, if a purchaser requests US FMS data after soliciting bids from contractors, the purchaser must demonstrate that commercial acquisition efforts have ceased before any US FMS data is provided. If the purchaser obtains FMS data and later determines to request a commercial price quote, the FMS offer may be withdrawn. DCS purchasing agreements may or may not include training, spare parts, and general support.

(21) Military equipment produced in the US is subject to International Traffic in Arms Regulations (“ITAR”) and Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”) and can only be exported to the EEA subject to relevant US legislation and/or authorization.

5. PRODUCT MARKET DEFINITION

(22) The Transaction brings together UTC’s aerospace businesses, which include commercial and military aero engines and aircraft systems, and Raytheon’s defence business, which focuses on missiles and missile systems, electronic warfare, and other defence systems.

(23) Both Parties are active in the production and supply of systems and components for military aircraft platforms. Although their respective product portfolio is largely complementary, there are some horizontal overlaps between the Parties’ activities. Those horizontal overlaps lie in the supply of military global navigation satellite systems (“GNSS”) receivers, military airborne communications systems (voice and data) and electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) sensors for military aircraft platforms.

(24) The Transaction also gives rise to some vertical links because of UTC’s supply of components for PGMs manufactured by Raytheon and rival suppliers. Those vertical links involve primarily the supply of GNSS receivers, actuation systems, inertial measurement units (“IMUs”) and propulsion systems for PGMs.

(25) According to the Notifying Party, there are no overlaps between UTC’s commercial aerospace products and Raytheon’s activities.

(26) The present section examines product market definition for all products in relation to which the Parties’ activities overlap horizontally, are vertically related or could potentially be regarded as complementary to one another.

5.1. GNSS receivers

5.1.1. Introduction

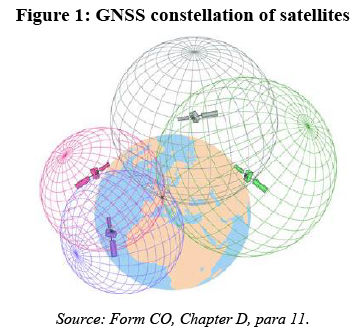

(27) GNSS serve to determine position and follow a route. GNSS have three components: (1) constellations of satellites orbiting the earth, (2) ground control systems managing the satellites and (3) equipment that receives and processes GNSS signals (GNSS receivers). All GNSS receivers calculate their location by measuring the distance between their position and four or more satellites.

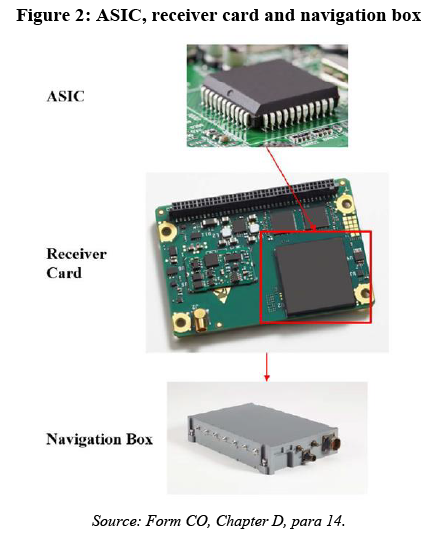

(28) GNSS receivers interact with satellites and calculate their position through an Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (“ASIC”), which is a semiconductor chip that receives, digitizes, and processes GNSS signals and shares the data with other systems (e.g., avionics). ASICs used in military GNSS receivers also incorporate cryptographic processing capabilities to decode encrypted signals.

(29) The ASIC is incorporated into a receiver card, which includes ancillary hardware and software (e.g., storage, memory, and a basic operating system). GNSS receiver cards can be sold as standalone products or incorporated into other systems (e.g., missile guidance) or in boxes, which are then mounted on a platform like an airframe. These boxes house the receiver card and related components (e.g., an inertial measurement unit).

(30) GNSS can operate signals that are openly available to anyone (typically used for civil purposes) and encrypted signals that can only be accessed with governmental consent (typically used for military or security-related purposes). Armed forces use military GNSS receivers to decrypt secured GNSS signals. Anti-jamming, which counters interference with GNSS signals, is not a component of GNSS receivers but is an ancillary capability typically included alongside a military GNSS receiver.

(31) The first GNSS system was the Global Positioning System (“GPS”), which was developed by the US government in the 1970s. Other countries have since developed similar systems, including the EU Galileo system.8 Both the US GPS and EU Galileo systems operate both signals openly available to anyone and encrypted signals.

(32) GPS receivers can use different ranging signals. These include (i) C/A-code, an unencrypted civil signal used by the vast majority of civilian GPS applications (e.g., mobile phones and passenger vehicles); (ii) P(Y)-code, an encrypted signal used for government applications, e.g., missile and aircraft guidance, ground vehicles, handheld devices, and as a source of precision timing information for a variety of applications; and (iii) military code (“M-code”), an encrypted GPS signal for military use that is currently under development.

(33) The US DoD has awarded funding to UTC, L3Harris, Raytheon and Trimble to develop M-code GPS receivers. According to the Notifying Party,9 all GPS equipment purchased by the US DoD after 2017 must be M-code compatible by law. However, as this would not yet be feasible, the US DoD has issued individual waivers permitting continued use of P(Y)-code GPS receivers. The Notifying Party expects that an exhaustive transition to M-code will take approximately 10-15 years.10

(34) The authorization of the US DoD is required to manufacture, sell, and use P(Y)-code or M-code receivers. Such authorization covers the entire receiver, not just the ASIC.

(35) The EU Galileo system is a GNSS developed by the European Union and operated by the European GNSS Agency and European Space Agency. Although it already enjoys widespread adoption in the mobile, automotive, marine, search-and-rescue, and industrial sectors, it is only scheduled to reach full operational capacity in 2020 with 30 satellites.11

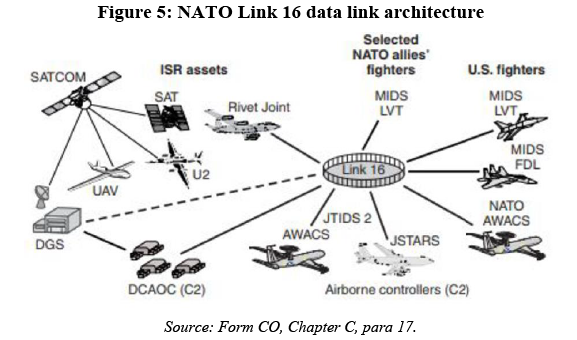

(36) Member States and the Commission, Council, and European External Action Service may authorize companies established in the EU to manufacture Galileo PRS receivers. Non-EU countries may also be authorized to produce Galileo PRS receivers under bilateral agreements. The Parties understand that EU companies with access to the Galileo PRS signal currently include, at a minimum, GMV (Spain), Leonardo (Italy), QinetiQ (UK), Siemens (Germany), and Thales (France).12

5.1.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(37) The Notifying Party submits that civilian and military GNSS receivers likely constitute distinct markets and that it is appropriate to define a relevant product market for the supply of military GNSS receivers without further segmentation.13

(38) First, according to the Notifying Party, while civilian GNSS receivers are manufactured by a wide range of suppliers for applications available to the public (e.g., handheld devices, sports watches, and passenger vehicles), both the manufacture and purchase of military GNSS receivers require authorization from national authorities (e.g., the U.S. DoD for GPS and EU Member States and institutions for Galileo). Once that authorization is granted, it would generally be possible for a civilian GNSS receiver supplier to start producing military receivers. Nevertheless, the Notifying Party submits that the additional needs of military users and the need for manufacturers to obtain governmental authorization likely provide sufficient supply- and demand-side differentiation to warrant a distinction for purposes of product market definition.14

(39) Second, the Notifying Party argues that there is no need to segment the supply of GNSS receivers based by military application.15 From a demand-side perspective, UTC argues that the same GNSS receiver card can typically be used in a variety of platforms. On the supply side, UTC submits that suppliers of military GNSS receivers for one platform could start producing receivers for another, provided they have the necessary US DoD authorization.

(40) Finally, according to the Notifying Party, the GPS and the EU Galileo systems (once it is fully operational) are substitutes.16

5.1.3. The Commission’s precedents

(41) In the past, the Commission has identified an overall market for GPS receivers but has ultimately left open the question of whether the market should be further segmented by product type (type of mission and class of reliability) or by final customer (military, commercial or institutional).17

5.1.4.The Commission’s assessment

(42) From a demand side perspective, according to the results of the market investigation, most market participants consider that civilian and military GNSS receivers constitute separate product markets due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices.18 One respondent to the market investigation indicated that ‘[m]ilitary receivers utilize a different signal and have technical features that ordinary, civilian receivers do not include, such as enhanced security to prevent disruption of signals’.19

(43) From the point of view of suppliers, the results of the market investigation have revealed that the production of civilian and military GNSS receivers entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs.20 This is irrespective of the fact that the manufacture and supply of military GNSS receivers requires authorisation from relevant national authorities. One market participant indicated that ‘in terms of technical features, the military receivers are more complex and require much more expertise and costs’.21 In line with this, another respondent to the market investigation indicated that ‘the product complexity is far higher for a military GNSS receiver, due to cyber constraints and cyber certification’.22

(44) Respondents to the market investigation indicated that, for assessing the relevant competitive dynamics, it may be appropriate to consider further segmentations of military GNSS receivers by military application (i.e. by platform).23 In particular, the results of the market investigation suggest that the strengths and market position of the different suppliers of GPS receivers may vary for ground equipment, aviation, maritime equipment, PGMs and handheld applications, respectively.24

(45) In turn, the results of the market investigation are not conclusive on the demand and supply-side substitutability between Galileo PRS receivers and P(Y)-code and M- code GPS receivers. Some respondents indicated that with the introduction of the Galileo PRS receivers, the situation has shifted from single mode receivers to dual mode receivers integrating multi-constellation capabilities. Accordingly, Galileo PRS receivers appear to be perceived as a complementary constellation to GPS receivers rather than a substitute.25 However, although the Galileo PRS signal should be operational as of 2020, the final operational capabilities (e.g., the infrastructure dedicated to maintenance the signal) will be delayed.26 Furthermore, military Galileo PRS receivers have not yet been fielded.

(46) Based on the assessment laid down in paragraphs (42) to (45), the Commission considers it appropriate to define a separate product market for military GPS receivers. The Commission will in addition factor into its assessment a possible differentiation in the production and supply of military GPS receivers by type of application/platform.

5.2. Military communication systems

5.2.1. Introduction

(47) Communication systems are devices used for the transmission of information for military or civil purposes. While civil and military communication systems share some basics features, military communication systems require specific features necessary to ensure reliability in the demanding environments of battlespace. These include anti-jamming, anti-spoofing, multi-band, multi-channel, encryption capabilities and resilience under arduous climate and transport conditions. Military communication systems include military (air and ground) radios, data links and satellite communication systems (SATCOMs).

(48) Military airborne radios provide secure air-to-air and air-to-ground connectivity to support voice and data communications, therefore enabling an aircraft to communicate with other (air or ground) platforms. Depending on the operational requirements of an aircraft, military airborne radios will operate in the high frequency (HF), very high frequency (VHF) or ultra-high frequency band (UHF).

(49) HF radios enable single-channel communication at frequencies up to 30 MHz and provide beyond line-of-sight communications (they are typically used by armed forces for communications over great distances, such as cross-continental communication). VHF/UHF radios enable single-channel communication at frequencies between 30 MHz and 1000 MHz and can only support line-of-sight communication (they are typically used at distances up to hundreds of kilometres). VHF/UHF radios can incorporate narrowband SATCOM functionality, which allows for beyond line-of-sight communications.

(50) Military ground radios enable secure ground-to-ground and ground-to-air communications. Since they usually need to communicate with airborne radios, ground radios generally operate at the same frequency bands as airborne radios (HF or VHF/UHF) and may as well feature narrowband SATCOM capabilities. Depending on the frequency band and other technical characteristics, ground radios allow data, image, voice and video communication. They can be fixed (typically at a military or government building) or deployable. Deployable ground radios can be used in land vehicles or carried by a soldier (in the hand or in the back).

(51) Military data links provide secure air-to-air, air-to-ground and ground-to-ground communications. While radios are primarily used for voice communications, the main purpose of data links is to transfer data, even though they can also transfer voice. Moreover, while radios allow only for point-to-point communications, data links devices enable communications between multiple points simultaneously. Finally, data links have higher bandwidth than radios. There are two types of data links: situational awareness (“SA”) data links, which use radio waves to create a “picture” of where assets and targets are in the battlespace; and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (“ISR”) data links, which provide connectivity to offload large amounts of intelligence information from platforms such as aircraft carrying cameras.

(52) Different data links communicate using different protocols generally designed and implemented by governments. The main military data links protocols are Link 11, Link 22, Link 16, Situational Awareness Data Link (“SADL”) and Enhanced Position Location Reporting System (“EPLRS”). To enable interoperability between armed forces, protocols are sometimes defined at a military alliance level. NATO countries, for example, use the Link 16 data link network.

(53) Military platforms may also use commercial data link products and related network services when operating in commercial airspace or other. The main commercial data links networks are ARINC27 and SITA. Both networks use the traditional, low- bandwidth Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (“ACARS”) protocol, first deployed in 1978.

(54) Military SATCOMs relay their radio signals via satellite, enabling secure communications between two locations at significant distances, including beyond line-of-sight communications. They can be narrowband, wideband or protected. narrowband SATCOMs operate in the UHF frequency. Wideband SATCOMs operate in frequencies higher than UHF and are used to transfer large amounts of data. Protected SATCOMs offer additional levels of resistance to interference.

5.2.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(55) First, the Notifying Party submits that civilian and military communication systems are not substitutable and likely constitute distinct markets. According to the Notifying Party, military customers require distinct features (e.g., anti-jamming, anti-spoofing, multi-band, multi-channel, encryption capabilities, and resilience under arduous climate or transport conditions) which requires manufacturers to make significant investments in engineering, which applies equally across radios and data links.28

(56) Second, with regard to military airborne radios in particular, the Notifying Party argues that military airborne and ground radios may be distinct markets, although there is significant supply-side substitutability. In this regard, according to the Notifying Party, there are significant demand-side differences between airborne and ground radios, given the conditions in which they operate (e.g., vibration and temperature ranges). That said, the Notifying Party argues that companies that currently manufacture military ground radios can switch production to manufacture military airborne radios, given the similarity of the fundamental radio technology and design, and vice versa.29

(57) Third, according to the Notifying Party, there is no need to segment radios by frequency (i.e. HF, VHF/UHF) because although HF and VHF/UHF radios are not perfect substitutes from the demand-side due to their different operational functionalities, the addition of narrowband SATCOM functionality to VHF/UHF radios enables beyond line-of-sight communications similar to that of HF radios. In addition, the Notifying Party argues that HF and VHF/UHF radios are highly substitutable from a supply-side perspective as current manufacturers of HF radios would able to produce VHF/UHF radio without any significant increase in cost or change of expertise, and vice versa.30

(58) Lastly, the Notifying Party submits that data links (i.e., SA and ISR data links) may comprise a distinct market, though data link functionality is increasingly incorporated into airborne radios – and there is increasing technological convergence between radios and data links.31

5.2.3.The Commission’s precedents

(59) In M.3735 – Finmeccanica/AMS, the Commission identified different segments within military communication systems depending on the functionality, the platform (ground, air, sea) and the force for which they are intended.32 In that case, the Commission distinguished between (i) military ground communications systems and (ii) military naval information and communication systems, while leaving open the exact market definition and the potential need for further segmentation.

5.2.4.The Commission’s assessment

(60) From a demand-side perspective, according to the results of the market investigation, most market participants consider that military airborne radios and military ground radios constitute separate product markets due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices.33 As a market participant explained, ‘[m]ilitary airborne radios and military ground radios have different requirements to suit different environmental conditions (e.g. vibration, temperature and atmospheric pressure etc.) and differ in size, and weight’.34 Another market participant indicated that ‘requirements of airborne and ground radios are different enough that there is almost no overlap in utilization’.35

(61) From a supply-side perspective, the market investigation has revealed that most market participants consider that the production of military airborne radios and the production of military ground radios entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs.36 One market participant explained that ‘[a]lthough the basic technology (i.e. software defined radios) can be the same for both airborne and ground radios, that notwithstanding the main steps for the development, production and, even more, certification are different, with direct consequences on the required expertize and the final cost of the equipment’.37 Another market participant indicated that ‘[i]t is often very difficult to use systems that were designed for ground use in an airborne environment’ and ‘[t]his is because the control, integration with other avionic systems, environmental, size, weight and power of the systems for the different environments can differ significantly and are not easy to adapt’.38

(62) Respondents to the market investigation indicated that, for assessing the relevant competitive dynamics, it may be appropriate to consider further segmentations of military airborne radios by frequency band between HF and VHF/UHF.39 In turn, the market investigation has revealed that military HF and VHF/UHF radios have different characteristics and applications, irrespective of whether VHF/UHF radios include narrowband SATCOM capabilities.40 The results of the market investigation are however not conclusive as to whether, from the point of view of the suppliers, the production of military radios of different frequency bands (e.g. HF, VHF/UHF) entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs. However, at least one market participant indicated that ‘[t]he production of every new airborne radio requires major investments in terms of production and test equipment on modul- and radio level, e.g. coating procedures, soldering and quality adjustments’ and ‘[s]ame for new ground based radios’.41

(63) With regard to military ground radios, the results of the market investigation show that most market participants consider that fixed and deployable ground radios constitute separate product markets due to limited substitutability for customers.42 The results of the market investigation are however not conclusive as to whether, from the point of view of suppliers, the production of fixed and deployable military ground radios entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs. The results of the market investigation are similarly not conclusive as to whether further segmentations within deployable ground radios should be considered.

(64) With regard to military data links, the market investigation has revealed that most market participants consider that, from both demand and supply side perspectives, it is appropriate to consider that military radios and data links constitute separate product markets.43 One market participant has explained that, ‘[r]adios are largely narrow band and low data rate, whereas data links can be very wide band, high bandwidth, and specialized to handle advanced network topologies and data routing’ and ‘[d]ata links are therefore different products and are not substitutable with radios’.44 Within data links, the results of the market investigation are however not conclusive as to whether further segmentations of the market between SA and ISR data links are appropriate.

(65) As to SATCOMs, most respondents to the market investigation indicated that it is appropriate to consider that SATCOMs constitute a separate product market from other military airborne communications systems (i.e. military radios and data links) due to limited substitutability for customers and suppliers.45 Within SATCOMs, most respondents consider that, from a demand side perspective, further segmentations between (i) narrowband SATCOMs, (ii) wideband SATCOMs and (iii) protected SATCOMs are should be considered due to limited substitutability for customers.46 However, the results of the market investigation are not conclusive as to whether, from the supply side perspective, the market for the supply of SATCOMs should be further segmented.

(66) Based on the assessment laid down in paragraphs (60) to (65), the Commission considers it appropriate to define separate product markets for the production and supply of, respectively, military airborne radios, military ground radios, military data links and SATCOMs. The Commission concludes that, for the purposes of the present Decision, no further segmentation of said markets is necessary, as the conclusion would remain the same, though a possible differentiation of military airborne radios by frequency band will be taken into account in the competitive assessment.

5.3. EO/IR sensors

5.3.1. Introduction

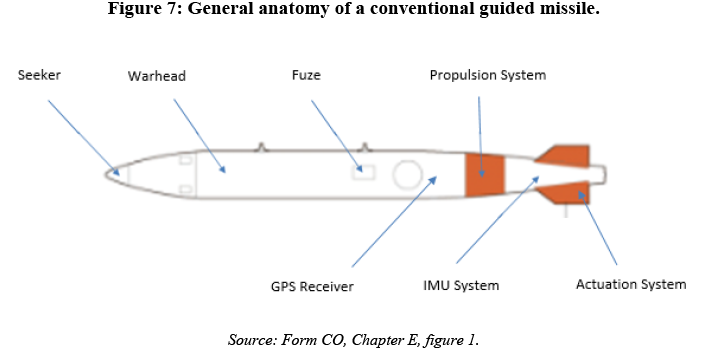

(67) Electro-optical and infra-red sensors (“EO/IR sensors”) are devices that convert light, changes thereof, or changes of its infrared radiation, into an electrical signal. These devices are installed on certain equipment used by military forces, law enforcement personnel, and other government and industry operators and allow users to identify and track objects, conduct threat assessments, assess intent, and, in some cases, provide laser targeting for guided precision munitions.

(68) EO/IR sensors working principle is based on measuring the light that is reflected by an object or, in the absence of light, on measuring the infrared radiation emitted by a heated object (such as a building, an engines, a person, or an animal).

(69) EO/IR sensors can be classified according to different criteria. The most common ways to classify them is according to their technical characteristics and to the intended use.

(70) From a technical characteristic point of view, EO/IR sensors can be classified according to their range of use, i.e. according to the distance within which an object can be detected by the sensor. In this respect, EO/IR sensors can be classified as low-, mid- and long-range.

(71) From an end-use point of view, EO/IR sensors can be classified according to the intended mission of the aircraft where they are installed. In this respect, EO/IR sensors can be classified as for targeting, for reconnaissance and for surveillance missions. While the objective of a targeting mission is to detect, identify, and track a certain target in sufficient detail in order to, for example, permit the effective delivery of a guided munition, a surveillance mission involves the persistent and systematic observation of an already known and usually static point of interest for an extended period of time. Compared to a surveillance mission, a reconnaissance mission involves broader intelligence gathering, covering multiple points of interest in a limited period of time.47

(72) In terms of integration into an aircraft, EO/IR sensors can be podded on or embedded in the aircraft. For illustration purposes, Figure 6 shows two different EO/IR sensors podded in the Dassault’s jet fighter named Rafale.

5.3.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(73) According to the Notifying Party, EO/IR sensors of long-, mid-, and short-range should be considered as separate product markets, due to limited demand- and supply-side substitutability.48

(74) From a demand-side view point, the Notifying Party argues that customers cannot substitute sensors of different ranges because: (i) EO/IR sensors of different ranges are not substitutable for the same application; (ii) EO/IR sensors of different ranges generally are not mounted on the same types of platform; (iii) EO/IR sensors of different ranges are procured by distinct customer groups because long-range EO/IR sensors tend to be purchased by the final customer, whereas short- and mid-range EO/IR sensors are typically purchased by OEMs. The Notifying Party also claims that the strong price difference between short-, medium- and long-range EO/IR sensors is an indication of the lack of demand-side substitutability.

(75) From a supply-side view point, the Notifying Party considers that no substitutability between long-, mid-, and short-range sensors exist because: (i) EO/IR sensors of different ranges require different production processes and technologies and are typically manufactured in different production lines; (ii) suppliers active in one category of EO/IR sensors cannot easily enter other segments because they would require to develop new technologies, to procure different materials, to establish new production facilities and to develop commercial relationships with different customer groups. According to the Notifying Party, the lack of supply-side substitutability is confirmed by the fact that most manufacturers of short-range EO/IR sensors are not active in mid- or long-range EO/IR sensors.

(76) The Notifying Party considers that a market segmentation by applications, as for example, by targeting, reconnaissance and surveillance missions, would not be appropriate because it would include entirely different products in the same category (without reflecting differences in size, weight, range, coverage, and, ultimately, their prices).49

(77) With respect to a possible distinction between podded and integrated EO/IR sensors, the Notifying Party considers that these two types of EO/IR sensors do not belong to separate product markets because they have the same capabilities and applications and often compete with each other.50

5.3.3. The Commission’s precedents

(78) In a previous decision,51 the Commission considered electro-optic systems as “active or passive systems used in military applications such as targeting, fire control or surveillance”. Due to limited supply-side substitutability, and a lack of demand-side substitutability, the Commission considered electro-optic systems as distinct markets “as they are conceived, designed and manufactured according to the very specific requirements of the applications they serve”.

(79) With respect to possible segmentations of EO/IR sensors, in a more recent decision,52 the Commission considered that the supply and demand landscapes are not necessarily the same for all EO/IR products, and therefore the segment of “sights” where a vertical relationship arose from that transaction, may constitute a distinct relevant market separate from other optronics equipment. Ultimately, the Commission left the market definition open because no competition concerns arose irrespective of the exact product market definition.

5.3.4. The Commission’s assessment

(80) The market investigation indicates that the Notifying Party’s proposed product market segmentation by range of EO/IR sensors, that is to say EO/IR sensors with short-, mid-, and long-range, reflects market conditions in terms of, for example, product characteristics, applications and prices. However, alternative market segmentations have also been suggested by respondents to the market investigation. In any event, as explained below, the exact product market definition can ultimately be left open because no competition concern would arise as a result of the Transaction, irrespectively of the exact product market definition.

(81) First, with respect to demand-side substitutability, the market investigation confirms the Notifying Party’s claim that customers have limited possibilities of substitution among EO/IR sensors with short-, mid-, and long-range.

(82) In particular, a large majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree with the Notifying Party’s view that short-, mid-, and long-range EO/IR sensors should be considered to constitute separate product markets due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices.53

(83) However, the market investigation does not seem to confirm the Notifying Party’s claim that long-, mid- and short-range EO/IR sensors are typically mounted on different types of aircrafts.54

(84) Second, with respect to supply-side substitutability, a large majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree with the Notifying Party’s view that the production of long-, mid- and short-range sensors entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs, therefore suggesting limited supply-side substitutability among these three types of EO/IR sensors.

(85) One supplier manufacturer also explained that ‘[a] supplier of sensors in one of these ranges cannot begin producing sensors in another range without making significant investments and engaging in substantial design efforts’.55 While another manufacturer explained that ‘[t]he production of long-range sensors requires telephoto optics, high spatial stability, high sensitivity, and high resolution, which require very specialized skills and trigger much higher costs of production. On the other hand, short-range sensors require much lower technology and expertise. The costs of production are also much lower compared to long-range sensors’.56

(86) Third, notwithstanding the lack of demand- and supply-side substitutability for short-, mid-, and long-range EO/IR sensors, a majority of the suppliers of military equipment that expressed a view in the market investigation considers that for assessing the relevant competitive dynamics, it may also be appropriate to consider an alternative segmentation based for example on the type of mission they serve (e.g., surveillance, reconnaissance, targeting).57 In that respect, however, the Notifying Party has explained that there was a significant overlap between the segmentation by ranges and by mission types.58

(87) Further, some of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation suggested other possible market segmentations. For example, a prominent EEA-based defence contractor indicated that ‘the relevant airborne product segmentation within EO/IR sensors is the destination in terms of missions: - Targeting pods (delivering a laser guided ammunition from a fighter type aircraft);- Reconnaissance pod; - Surveillance products (for UAVs and mission aircraft)’.59 Similarly, an OEM indicated that it ‘[…] segments EO/IR sensors differently due to their functionalities, but not on the ranges particularly’.60 Another supplier of military equipment further explained that ‘[a]ll these applications [i.e. surveillance, reconnaissance, targeting] require different technical approaches. Target tracking systems need much more accuracy, resolution, sightline spin rate than surveillance systems’.61

(88) With respect to a possible distinction between integrated and podded EO/IR sensors, a large majority of suppliers of military equipment, including OEMs, confirmed the Notifying Party’s claim that embedded and podded EO/IR sensors can have the same capabilities and applications.62 However, a number of respondents also highlighted several differences between these two types of sensors, in terms of, e.g., performance, effects on aerodynamic and observability, and space requirements, thus highlighting that the two types of sensors are not completely interchangeable.63

(89) In conclusion, the market investigation appears to confirm the Notifying Party’s claim that long-, mid-, and short-range EO/IR sensors constitute three distinct product markets due to limited demand-side and supply-side substitutability. However, the market investigation also suggests that an alternative way of defining product markets for EO/IR sensors would be based on their final use, i.e. that the markets for EO/IR sensors for surveillance, for reconnaissance, and for targeting would constitute three distinct product markets. At the end though, while there might be some overlaps between a segmentation by ranges and by mission types, the exact product market definition can be left open because, as explained in Section 7.1.3 and for the purposes of this Decision, no competition concern would arise as a result of the Transaction, irrespective of whether product markets are defined based on sensors range or based on final application.

5.4. Precision guided munitions (‘PGMs’)

5.4.1. Introduction

(90) Innovation in the field of military weapons and munitions increased exponentially during the 20th century driven by advances in technology. Basic projectiles and unguided missiles (known as rockets) developed into sophisticated guided systems, which are now commonplace today.

(91) Modern day PGMs rely on sophisticated subsystems and components to strike their intended target. As a result, the number of aircrews and equipment in high-risk environments, in particular, is considerably reduced. The advent of PGMs resulted in the renaming of older unguided bombs as “dumb” or “gravity” bombs.

(92) PGMs contain a number of subsystems and components. Each subsystem performs a particular function that allows the PGM to perform specific actions; e.g., propulsion, flight, target identification, and detonation. The same subsystems and components are used to provide the guidance capabilities to guided projectiles, guided bombs and guided missiles. Additional subsystems and components are required for a guided missile to function i.e., propulsion systems. The precise specifications of those subsystems and components may vary and be tailored to the specific mission purpose.

(93) The exact combination of systems and components will vary depending on the type of PGM, and the mission-specific purpose it is intended for (e.g., a guided bomb or guided projectile would not contain a propulsion system). However, PGMs will generally include some or all of the following subsystems, as described by the Parties.64

(a) Seeker: Acquires and tracks the target. The seeker is mounted at the head of the weapon and allows the weapon to detect energy; e.g., infrared or radar to help direct the weapon to its target. A GPS guided weapon may contain an infrared or radar seeker (referred to as multi-mode) but GPS guidance itself does not require a seeker and uses the GPS satellite constellation to provide position and velocity information to enable the weapon to strike its target.

(b) Warhead: The energetic, explosive part of the weapon. There are a range of conventional warheads (blast, fragmentation, continues-rod, etc.) or alternatively a nuclear or chemical/biological warhead could be used.

(c) Fuze: Detects that the weapon is in the vicinity of the target and detonates a weapon’s warhead. The triggering functionality is normally based on engaging in contact with or close proximity to the target but can also be based on time, laser functionality, etc. A safety and arming mechanism is built into the fuse to prevent premature detonation.

(d) GPS Receiver: The receiver uses the GPS satellite constellation to provide position and velocity information to enable the weapon to strike its target.

(e) Actuation System: Helps control the weapon’s flight. The actuation system controls the adjustable aerodynamic surfaces of the weapon to determine its flight path. The weapon’s fins or thrust vector move in response to steering commands from the flight computer to steer the weapon.

(f) The IMU measures the weapon’s rotation, angular rate, and acceleration/force.

(g) Propulsion System: Provides the required initial thrust to enable the weapon to fly with sufficient velocity to reach the target. Various technologies can be used in the propulsion system of a weapon, e.g., solid rocket motors, ramjets, turbojets, etc.

(94) In addition to the main systems and components described above, other components may be necessary depending on the type of PGM and its mission-specific purpose.

5.4.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(95) The Parties define three criteria that drive the segmentation of the weapons market ‘There are three common ways to distinguish between military weapons: (i) the warhead; (ii) whether the weapon is self-propelled or not; and (iii) whether it uses a guidance system’65.

(96) The Parties view on the market segmentation is the following: ‘The Parties consider that it is likely appropriate to segment the weapons market between: (i) bombs; (ii) projectiles; (iii) rockets; and (iv) missiles. The Parties do not consider it necessary to segment these further.’66

(97) With regards to PGMs, more specifically, the Parties distinguish three different markets:

(a) Guided Bombs: A bomb is typically deployed by an aircraft and uses only gravity to find its target. As with projectiles, technological advances now enable bombs to include guidance systems and other components that increase the accuracy of their strike rate. These are referred to as guided bombs. Guided bombs differ from guided missiles in that they do not contain any propulsion technology.

(b) Guided Projectiles: Projectiles, also referred to as shells, are non-self- propelled airborne explosive devices fired from a separate object (gun) with force. As technology has evolved, projectiles have become more sophisticated and now commonly contain additional guidance systems or components that increase the accuracy of their strike. Guided projectiles differ from guided missiles in that they do not contain their own propulsion technology but rely on the force from the propellant platform.

(c) Guided Missiles: Guided missiles are powered by jet or rocket propulsion and rely on a guidance system, which has the ability to change course mid-air and direct the missile to a precise target. This minimizes collateral damage, increases the effectiveness of the strike and creates fewer risks for the person and/or equipment deploying the missile. Guided missiles are also referred to as precision missiles.

(98) Considering specifically guided missiles, the Parties specify that that they are designed or adapted for specific operational purposes, primarily:

(a) Surface-to-surface missiles, launched from the land (or from a ship) to strike targets located elsewhere on land or sea;

(b) Air-to-surface missiles, launched from aircraft to strike targets on land or at sea;

(c) Surface-to-air missiles, launched from land (or from a ship) to strike targets in the air;

(d) Air-to-air missiles, launched from aircraft to strike targets in the air.

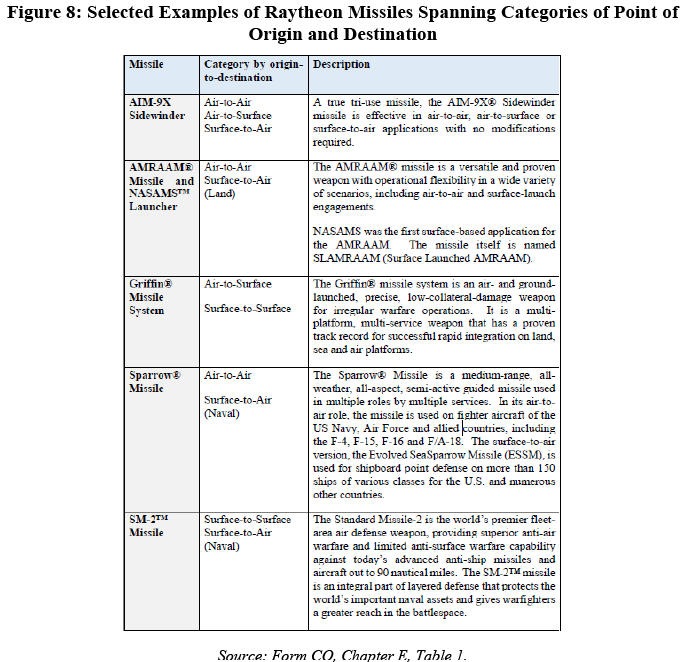

(99) The Parties do not consider the point of origin or destination as a relevant segmentation. ‘The Parties consider that all guided missiles should be considered part of the same product market irrespective of their point of origin and destination. Guided missiles are designed or adapted for specific operational purposes. The point of origin and destination of a missile are largely immaterial for the majority of missiles.’67 The Parties state that even if, at conception, a guided missile is typically designed for a specific launch platform, based on the needs of the customer it is common for guided missiles to be subsequently adapted for other launch platforms. Raytheon gives examples of guided missile product that can be used across different launch platforms. ‘For example, the AIM-9X Sidewinder may be operated as an air- to-air, air-to-surface and surface-to-air missile,14 and the AMRAAM (Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile) has also been adapted for use as a surface-to-air interceptor missile, where it is the baseline weapon on the NASAMSTM launcher.’68 There are numerous guided missiles that span categories based on point of origin and destination as described in Figure 8 below.

(100) The Parties consider that the traditional “strategic” versus “tactical” distinction is not anymore relevant with technological advancements blurring the segmentation. Strategic missiles are, historically, weapons designed to strike targets far beyond the battle area whereas tactical missiles are intended for battlefield use or shorter range and usually employ conventional warheads. Raytheon, to substantiate the irrelevance of this segmentation, gives example of guided missile product that would be qualified as “tactical” that can now be fired from much further distances with greater accuracy. ‘For example, Raytheon’s Tomahawk cruise missile is designed to be launched at long range away from the battlefield and to strike distant targets (previously considered a “strategic” capability) but with a conventional high explosive warhead (previously considered “tactical”). They are guided missiles that follow a controlled, non-ballistic profile to remain within the Earth’s atmosphere during flight but have the range of a strategic missile.’69

5.4.3. The Commission’s precedents

(101) The Commission has not previously assessed the relevant product market for projectiles and bombs. The Commission has previously assessed the relevant product market for guided weapons and guided weapons systems (herein also referred to as “guided missiles”), competition for which takes place at the prime contract level.70 In particular, the Commission has previously distinguished between “strategic” and “tactical” guided weapons.

(102) In Roxel/Protac the Commission stated ‘[t]actical missiles are used for specific, geographically limited actions, either to protect territorial property against the threat of attack (e.g., from tanks, planes or ships) or to dispose of enemy capacity in destroying or damaging its infrastructure. Tactical weapons typically carry a conventional high explosive warhead. Strategic missiles, on the other hand, are dedicated to State defense and typically have a longer range and greater destruction capabilities than tactical missiles. The decision to employ strategic missiles is generally reserved to the highest levels whereas the decision to use tactical missiles is normally made by commanders in the field.’71 In Airbus/Safran/JV, the Commission described ‘[m]issiles are guided weapons carrying either a high explosive (tactical missiles) or a nuclear (strategic missiles) warhead.’72

(103) Most recently, in Safran/Zodiac Aerospace, the Commission stated that strategic missiles are ‘dedicated to critical state defense applications. They have a long range and great destruction capabilities relying on nuclear warheads’ whereas tactical missiles have historically been used for ‘specific geographically limited actions to protect against the threat of attack or to destroy the enemy infrastructure or capacity’.73

(104) Further, the Commission previously stated that ‘tactical missiles can be classified according to functionality and products characteristics such as their point of origin and destination (e.g., air-to-air, surface-to-air/land, surface-to-air/naval, air-to- surface, anti-ships and anti-tanks) and range (very short range, short range, medium range and long range),’ but ultimately left the exact product market definition open.74

5.4.4.The Commission’s assessment

(105) The results of the market investigation reveal that the Notifying Party’s proposed product market segmentation by type of weapon, that is to say bombs, projectiles and missiles, reflects market conditions in terms of product characteristics, applications and prices. However, alternative market segmentations have also been suggested by respondents to the market investigation. In any event, as explained below, the exact product market definition can ultimately be left open because no competition concern arise as a result of the Transaction, irrespectively of the exact product market definition.

(106) First, with respect to demand-side substitutability, the market investigation confirms the Notifying Party’s claim that customers have limited possibilities of substitution among bombs, projectiles and missiles.

(107) A large majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree with the Notifying Party’s view that bombs, projectiles and missiles constitute separate product markets due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices.75 As described by a market participant: ‘The capabilities and market pricing associated with each product market would be different. Customers would look at each category independently. For example, if they wished to purchase a bomb, they would purchase one, it would not be substituted for a projectile or missile.’76

(108) Second, with respect to supply-side substitutability, a large majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree that the production of bombs, projectiles and missiles entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs.

(109) One supplier manufacturer also explained that ‘Cost – the price of bombs is significantly lower; and Technical features – the capability of each will differ. For example, a bomb could be dropped on an intended target from above. However, a missile would contain other key technical features such as an engine to ensure that it could travel to its intended target.’.77 While another manufacturer explained that ‘[v]ery specific knowhow and technical/engineering experience required for each of the niches.’78

(110) Third, some of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation suggested alternative market segmentations. For example a segmentation based on the distinction between tactical and strategic missiles. A majority of the respondents to the market investigation considered that is it appropriate to consider that tactical missiles (used for specific, geographically limited actions) and strategic missiles (dedicated to state defence with longer range and greater destruction capabilities) constitute separate product markets due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices.79 A military equipment supplier explains: ‘There is no substitution in product application between tactical and strategic systems. They perform different functions. Strategic systems also tend to be extremely expensive systems given their massive size and other attributes, such as nuclear warheads.’80

(111) With respect to supply-side substitutability, a large majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree that - bombs, projectiles and missiles entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs.81 A market participant describes the difference in facilities able to produce the tactical and strategic missiles: ‘The manufacture of strategic missiles requires different types of facilities and capabilities than the manufacture of tactical missiles. Strategic missiles are much larger weapons systems, so the equipment needed to handle and manufacture systems of that size is different in scale than that needed for manufacturing tactical missiles.’82 The market investigation further substantiate the absence of supply-side substitutability with a majority of the market participants confirming the inability for a company that produces either strategic missiles or tactical missiles, to start producing the other type of missiles without having to incur major investments and within a short timeframe (based on industry standards)83.

(112) With respect to a possible distinction based on point of origin and destination, the market investigation provides mixed results. Some market participants responded that is it necessary to consider further segmentations within tactical missiles based on their point of origin and destination (air-to-air, surface-to-air/land, surface-to- air/naval, air-to-surface). A military equipment supplier explains that ‘[t]he different mission sets lead to specific missile designs that make it difficult to be interchangeable. For example, an air-to-air missile may have a much higher end propulsion or seeker solution compared to an air-to-surface missile intended for stationary targets.’84 Other market participant claim that this further segmentation of the market is not relevant arguing that ‘[o]verall, the same class of products and technologies is currently used for the different applications.’85

(113) In conclusion, the market investigation confirms the Notifying Party’s claim that the markets for bombs, projectiles and missiles constitute distinct product markets due to limited demand-side and supply-side substitutability. However, the market investigation also suggests that a further segmentation of product markets specifically for missiles could be based on their final use, i.e. that strategic and tactical missiles would constitute distinct product markets. At the end, though, the exact product market definition can be left open because no competition concern would arise as a result of the Transaction, irrespective of whether product markets are defined based on the type of PGM, or based on their final use.

5.5. Actuation systems

5.5.1. Introduction

(114) As described in paragraph (93), PGMs contain a number of subsystems and components. Each subsystem performs a particular function that allows the PGM to perform specific actions.

(115) Actuation Systems help control the weapon’s flight. The actuation system controls the adjustable aerodynamic surfaces of the weapon to determine its flight path. The weapon’s fins or thrust vector move in response to steering commands from the flight computer to steer the weapon.

(116) There are two main types of PGM actuation systems: (i) thrust vector-based actuation systems (‘TVA’); and (ii) fin-based actuation systems. While there are limited other types of actuation systems, TVA and fin-based are used for the vast majority of PGMs.

(117) TVA typically relies on engines or thrust nozzles to change the weapon’s trajectory, and is therefore used only if the weapon is self-propelled (i.e., guided missiles). In general, the technology, components, and production costs for TVA systems are significantly higher than fin-based solutions. TVA systems are typically used on higher-end guided missile systems, and in particular, are required for systems which fly at very high altitudes where the atmosphere is too thin for a guided missile’s actuation fins to be effective. TVA is becoming more common with the increasing development of guided missiles which exit the Earth’s atmosphere.

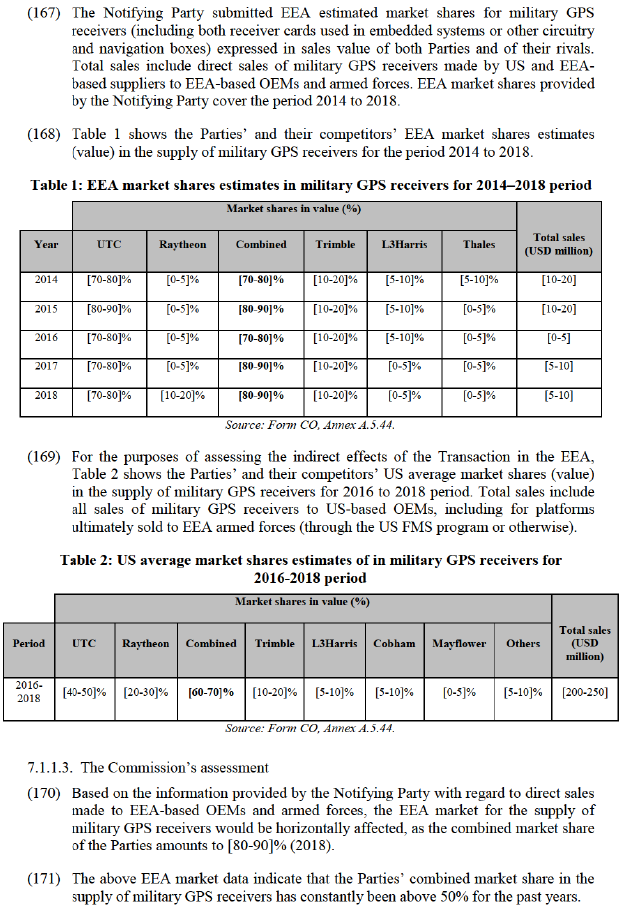

(118) Fin-based actuation systems use control surfaces (i.e., fins) to alter the flight path of a PGM, in the same way as a conventional commercial aircraft. The fins use air resistance to guide the PGM, and need only be small because tiny movements are capable of having a directional impact when the PGM is travelling at high speed. Due to the reliance on air resistance, fin-based actuation systems must have adequate air density and require airflow across the surface to maintain the necessary control authority. For this reason, they are inoperable in low air density or exoatmospheric conditions.

5.5.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(119) The Parties consider that fin-based actuation systems are suitable for a vast majority of the lower end missile systems but are not applicable to guided bombs or guided projectiles while TVA is most commonly used in strategic and high-end tactical guided missiles. Although the underlying actuation technology is consistent across multiple PGMs, each system is tailored to the specific application. In contrast to fin- based actuation systems, the Parties are not aware of TVA systems being used interchangeably across multiple PGMs.

(120) Therefore the Parties consider it may also be appropriate to segment the relevant product market for PGM actuation systems between: (i) TVA, and (ii) fin-based actuation systems.

5.5.3. The Commission’s precedents

(121) The Commission has previously decided that guided missile actuation systems constitute a separate product market.86

(122) The Commission’s market investigations into these products have previously suggested a potential delineation between fin-based actuation systems and TVA systems: ‘In fin-based missiles, the actuation system controls the position of aerodynamic fins in response to steering commands from the flight computer, while the actuation system in thrust vector control missiles steers the missile by moving the missile engine’s exhaust nozzle and thereby changing the direction of the thrust coming from the engine. Thrust vector control is used for ballistic missiles (missiles that fly outside the atmosphere) since aerodynamic control surfaces (movable fins) are ineffective for ballistic missiles that fly outside the atmosphere’.87

5.5.4. The Commission’s assessment

(123) The market investigation indicates that a market segmentation distinguishing TVA and fin-based actuation systems for PGMs reflects market conditions in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices. In any event, the exact product market definition can ultimately be left open because no competition concern would arise as a result of the Transaction, irrespectively of the exact product market definition.

(124) First, with respect to demand-side substitutability, a majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree with the view that it is appropriate to consider that thrust vector-based (TVA) and fin-based actuation systems for PGMs constitute separate product markets due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices.88

(125) As described by a market participant, ‘[a]s is the case with many other aspects of precision guided munitions, the application and environment in which a missile will operate will drive the selection of the guidance system to be used. If the operating parameters call for a TVA, then the missile provider cannot use a fin-based guidance setup, and vice versa.’89

(126) Second, with respect to supply-side substitutability, a large majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree that the production of TVA and fin-based actuation systems for PGMs entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs.90 A market participant explains that ‘[t]he materials, technology and complexity can be significantly different between these two systems.’91.

(127) The absence of substitutability and the inability to switch between TVA and fin based actuators is also explained by a market participant ‘The choice between TVA and fin-based actuation is done at the beginning of the programme. The switch from one solution to another solution is likely not to be a realistic option’92.

(128) In conclusion, the market investigation confirms that TVA and fin-based actuation systems constitute distinct product markets due to the limited demand-side and supply-side substitutability. At the end, though, the exact product market definition can be left open because no competition concern would arise as a result of the Transaction, irrespectively if product markets are defined based on the type of actuators, or not.

5.6. IMUs

5.6.1. Introduction

(129) An IMU is an electronic device that measures and reports how specific forces cause a body to change its vector. The IMU works from within a PGM’s control systems where gyroscopes and accelerometers measure the PGM’s rotation and angular rate in relation to a fixed point and to control the PGM’s velocity and flight path. The IMU system communicates these measurements to the PGM’s guidance and control systems.

5.6.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(130) The Parties submit that the relevant product market for IMUs should be segmented by grade: (i) high performance navigation grade IMUs, (ii) lower performance tactical grade IMUs, and (iii) consumer grade IMUs.93

(131) The Parties argue that IMU products across these three categories are generally not interchangeable. This is based on the fact that a customer’s product selection is based on the specific performance and cost requirements. Therefore, switching to a navigation grade IMU where this is not functionally required would be cost prohibitive. Alternatively, switching to a tactical grade IMU for an aircraft or long range guided missile application would not be possible as it would be unable to achieve the required operational performance level.

(132) More specifically for PGMs, navigation grade systems for aircraft and cruise missiles operate over long periods of time, must provide highly accurate information and use much more sophisticated components. By contrast, other types of PGM have much shorter flight times and ground vehicles operate at much lower speeds so these applications are able to use lower performing tactical grade sensors

(133) For tactical IMUs, the Parties submit that the relevant product market includes all tactical grade IMUs irrespective of their application (missiles, land vehicles, UAVs, etc.). UTC estimates that its market share in the overall market of tactical grade IMUs is lower than [20-30]%.

5.6.3. The Commission’s precedents

(134) The Commission has previously considered there to be a separate product market for inertial guidance systems within guided weapons.94 In other cases, the Commission has referred to separate markets for: (i) sensor avionics, and (ii) mission avionics, itself further segmented into flight avionics and CNI avionics.95

5.6.4.The Commission’s assessment

(135) The results of the market investigation indicate that a market segmentation distinguishing lower end tactical IMUs from navigation IMUs systems for PGMs reflects market conditions in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices. In any event, though, the exact product market definition can ultimately be left open because no competition concern would arise as a result of the Transaction, irrespectively of the exact product market definition. Consumer grade IMUs are used in electronics products (smartphones use IMU sensors to determine movement). The consumer grade sensors price point is no more than USD 1 per unit and these sensors are not used for PGMs. Therefore they are not considered in this section and in the remaining of the Decision.

(136) First, with respect to demand-side substitutability, a large majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree with the view that lower performance tactical grade IMUs (used in short-range PGMs, land vehicles, sensor stabilization, and low altitude tactical UAVs) constitute a product market separate from other IMUs due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics, applications and prices.96

(137) As described by a market participant, ‘[l]ower performance tactical grade IMUs constitute a product market separate from other IMUs, due to the important difference in terms of performance. These IMUs are suited for low cost and short range PGMs.’97 Another market participant explains that ‘Performance characteristics, complexity and price vary significantly between short range and longer range applications.’98

(138) Second, with respect to supply-side substitutability, a majority of the suppliers of military equipment that replied to the market investigation agree that the production of lower performance tactical grade IMUs and other IMUs for PGMs entail significantly different technical features, expertise and costs.99 A market participant explains that ‘[t]he materials, technology and complexity can be significantly different between these two systems.’100

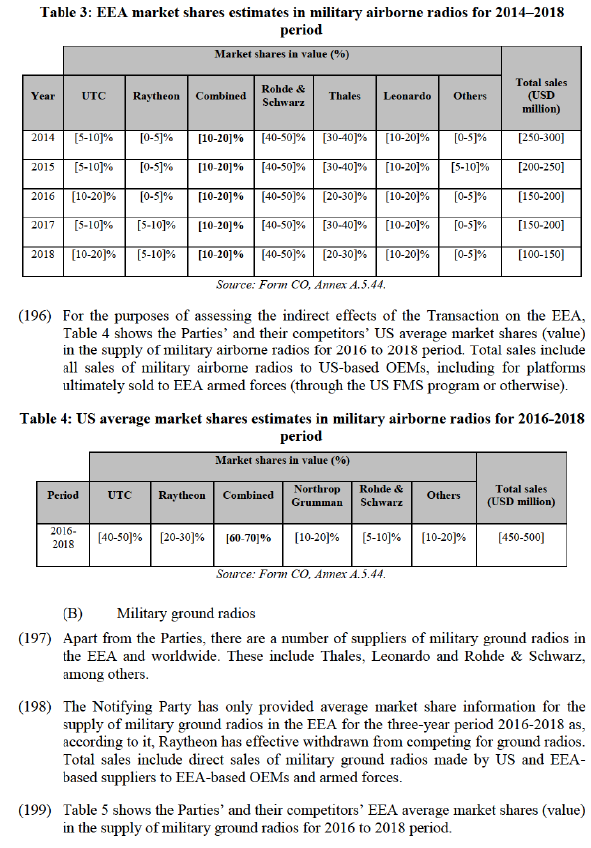

(139) The absence of substitutability is mainly explained by the fact that it would not be economically viable to substitute one with another given the prices of IMUs is strongly linked to their performance. As explained by a market participant ‘The price is a key parameter for the cost of operations and the IMU must be optimized to the use case requirement.’101 Another market participant confirms ‘Performance drives cost at IMUs!’102

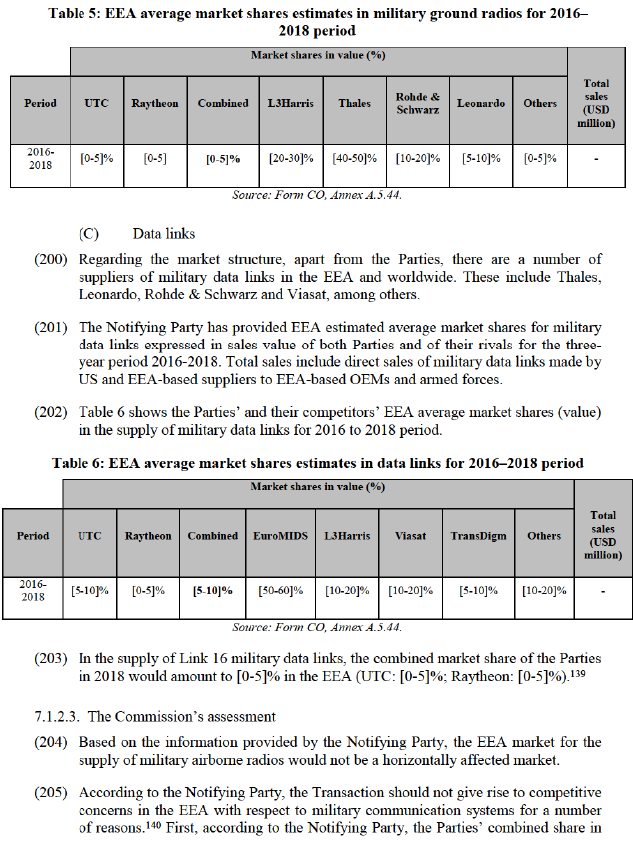

(140) In conclusion, the market investigation seems to confirm that tactical IMUs systems and other IMUs for PGMs constitute distinct product markets due to the limited demand-side and supply-side substitutability. At the end, the exact product market definition can be left open because no competition concern would arise as a result of the Transaction, irrespectively if product markets are defined based on the type of IMU, or not.

5.7. ARINC

(141) As a matter of clarity, the ARINC network should be distinguished from ARINC standards.

(142) The ARINC network is a low-bandwidth air-to-ground and ground-to-ground communications network that is owned and operated by UTC. It is used predominantly by airlines to transfer data between aircraft and counterparties on the ground (e.g., between an airline’s operation centre, air traffic control, border control, and airline partners). Military aircraft may use ARINC to communicate with air traffic control or operations centres while operating in commercial airspace, or – notably for VIP and maritime patrol aircraft – to transmit data or messages in support of their operations.

(143) ARINC standards are a set of communications standards for avionics, wiring, and other aircraft electronics. They are stewarded by SAE International, an independent industry body that is unrelated to UTC. An example of an ARINC standard is ARINC Specification 618, which defines the low-bandwidth ACARS protocol used to send short messages between aircraft and the ground.

(144) As described by the Parties: ‘The ARINC and SITA networks use the traditional, low- bandwidth Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (“ACARS”) protocol, first deployed in 1978. The ACARS protocol also allows aircraft operators to transmit low-volume snapshot information on the aircraft status (akin to text messages), typically several times per flight, or repair messages in case of a component fault in flight.’103

(145) Only the ARINC network is controlled by UTC. It shares the “ARINC” name with the ARINC standards because both the network and standards were previously under the umbrella of ARINC Incorporated, which UTC (then Rockwell Collins) acquired in 2013. As part of this acquisition, however, UTC transferred management of the ARINC standards to SAE International, precisely to preserve independence and pre- empt foreclosure.

5.7.1.The Notifying Party’s view

(146) The Notifying Party submits that there is a high degree of substitutability among datalink network services that rely on different types of connectivity, including VHF and SATCOM as provided by ARINC and SITA. The Notifying Party explains that for safety and efficiency reasons, airlines generally have access to both ARINC and SITA networks.

5.7.2. The Commission’s precedents

(147) In UTC/Rockwell Collins ‘The results of the Commission's market investigation have shown that the majority of airlines consider the datalink services offered by ARINC and SITA to be interchangeable. The geographic coverage difference has nonetheless been singled out. In fact, while Rockwell Collins is the exclusive supplier of VHF in […], SITA is the exclusive supplier of VHF in […]. Nonetheless both airlines can provide coverage using other connectivity means. The majority of OEMs therefore considered that ARINC and SITA compete’.104

5.7.3. The Commission’s assessment

(148) Market investigation shows that both ARINC and SITA are used as datalink network services and that market participant consider that they are alternative providing a similar service. A market participant explains that ‘[the company] considers that SITA is the alternative to ARINC’105 and further specifies that ‘the question refers to the role of ARINC as Communication Service Provider (CSP) for civil Datalink services. The same service is provided by SITA in Europe.'106

(149) In conclusion, the market investigation appears to confirm that ARINC and SITA are considered to offer alternative datalink network services. However, the question of whether ARINC and SITA constitute separate markets or belong to a single product market can be left open as the Transaction does not raise serious doubts regarding its compatibility with the internal market under any of those segmentations.

6. GEOGRAPHIC MARKET DEFINITION

(150) As explained in its Market Definition Notice, a relevant geographic market is the geographic area in which the conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous and which can be distinguished from neighbouring areas because the conditions of competition are appreciably different in those areas.107

6.1. The Notifying Party’s view

(151) The Notifying Party submits that the relevant geographic market for military products is EEA-wide. In particular, the Notifying Party submits that, although transportation costs represent a negligible share of the overall cost of the supply of military products, conditions of competition in the EEA are differentiated from those prevailing elsewhere (including in the US) for several reasons.108

(152) First, the Notifying Party submits that some military products produced in the US are subject to ITAR or EAR restrictions and can only be exported to the EEA subject to relevant US legislation and/or authorization. Second, the Notifying Party argues that the EEA features an autonomous legal regime for the international trade of military products, which do not apply to non-EEA suppliers. Third, according to the Notifying Party, EEA governments would typically have preferred long-established relationships with local suppliers. Fourth, the leading suppliers to the EEA defence industry would be distinct from the US-based manufacturers that typically supply the US DoD.

(153) In addition, the Notifying Party submits that, although some early Commission decisions concerning the defence industry defined national markets on the basis of national preferences of the monopsonistic buyers, a national geographic market definition is not instructive for purposes of the assessment of the Transaction. This would be because these Commission decisions tended to concern concentrations involving the incumbent supplier in a Member State and the Parties are not incumbent players in any Member State. Further, according to the Notifying Party, there would be a trend towards internationalization in the defence industry (particularly among EEA Member States).

6.2. The Commission’s precedents

(154) In the past, the Commission has left open the possibility of defining markets for specific military and defence applications on an EEA-wide or national basis due to, e.g., the existence of specific government regulations (such export restrictions) or national security-related preferences for local suppliers.109

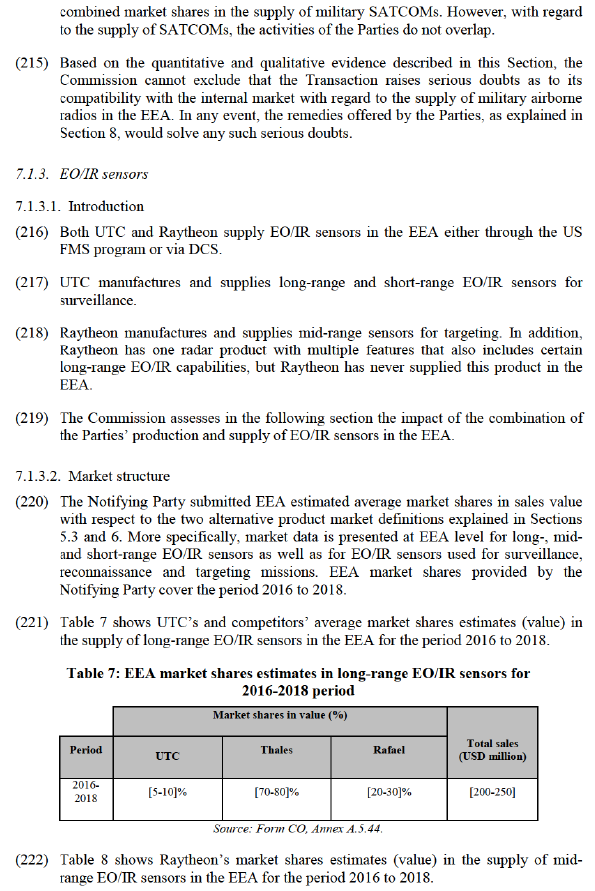

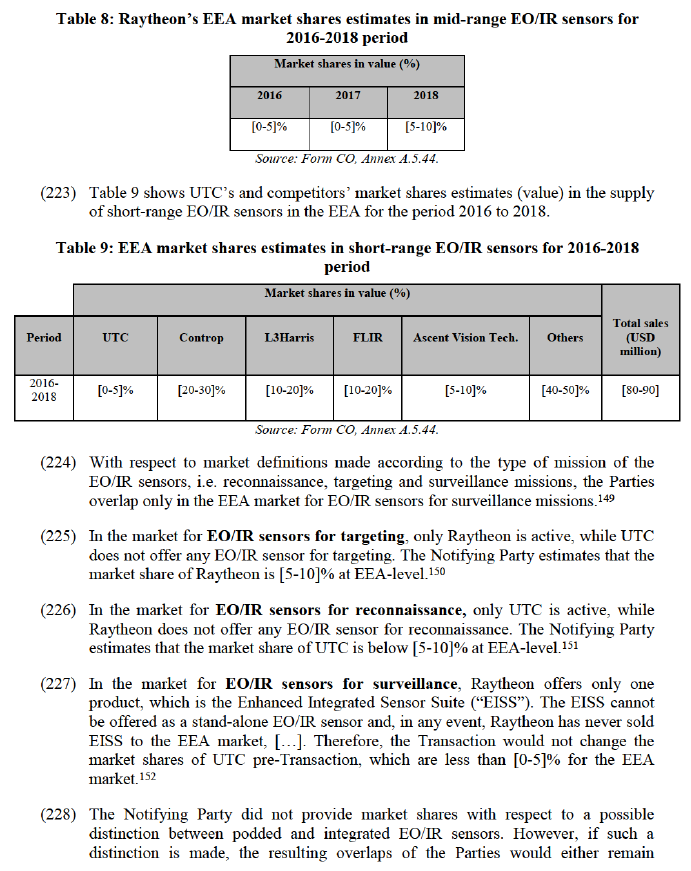

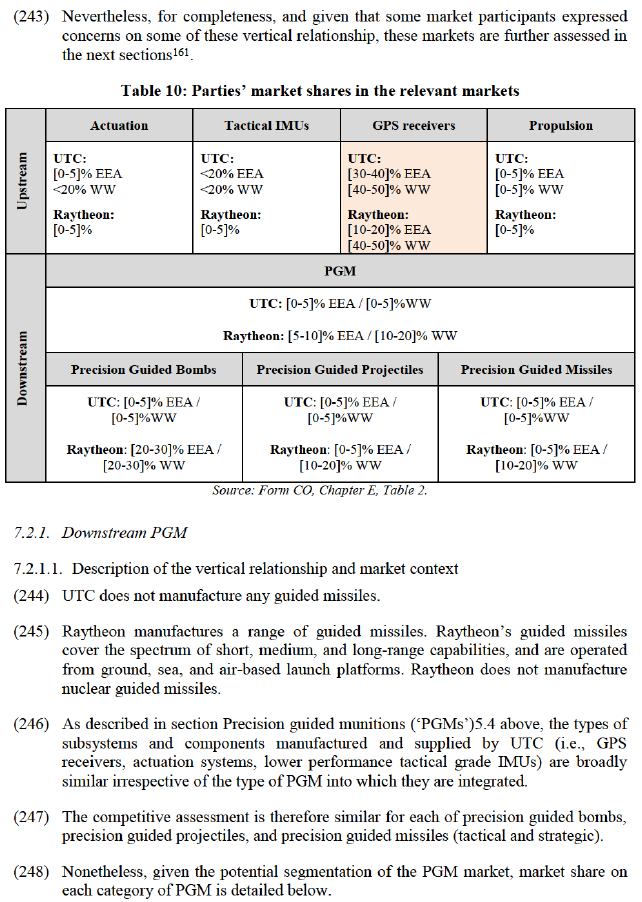

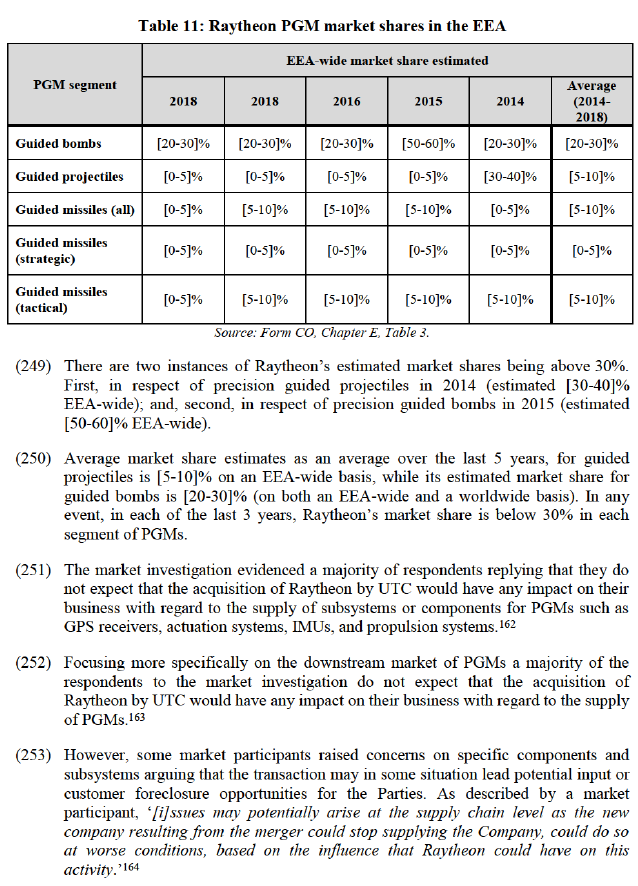

6.3. The Commission’s assessment