Commission, June 11, 2019, No M.8713

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

TATA STEEL / THYSSENKRUPP / JV

COMMISSION DECISION of 11.6.2019

declaring a concentration to be incompatible with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement

(Case M.8713 – TATA STEEL / THYSSENKRUPP / JV)

(Text with EEA relevance)

(Only the English text is authentic)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area, and in particular Article 57 thereof,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20.1.2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings1, and in particular Article 8(3) thereof,

Having regard to the Commission's decision of 30.10.2018 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given the undertakings concerned the opportunity to make known their views on the objections raised by the Commission,

Having regard to the opinion of the Advisory Committee on Concentrations, Having regard to the final report of the Hearing Officer in this case,

1. INTRODUCTION

(1) On 25 September 2018, the Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (the ‘Merger Regulation’) by which Tata Steel Limited (‘Tata’) and thyssenkrupp AG (‘ThyssenKrupp’) would acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) and 3(4) of the Merger Regulation joint control of a newly created joint venture (the ‘JV’).2 Tata and ThyssenKrupp are designated hereinafter as the ‘Notifying Parties’ or the ‘Parties’, and each separately as a ‘Party’.

(2) Tata, incorporated in India, is a diversified company active in the mining of coal and iron ore, manufacturing of steel products, and selling those steel products globally. Tata further produces ferro-alloys and related minerals and manufactures certain other products such as agricultural equipment and bearings.

(3) ThyssenKrupp, incorporated in Germany, is a diversified industrial group active in the production of flat carbon steel products, material services, elevator technology, industrial solution and components technology.

2. THE OPERATION AND THE CONCENTRATION

(4) Tata and ThyssenKrupp intend to establish the JV, a new joint venture, which would be active in the production of flat carbon steel and electrical steel products. In accordance with the Contribution Agreement and the Shareholders’ Agreement signed on 30 June 2018, each of the Notifying Parties would bring into the JV their European flat carbon steel and electrical steel production assets and businesses. The steel mill services of ThyssenKrupp would also be transferred to the JV. The operation is hereinafter also referred to as the ‘Transaction’.

(5) Pursuant to the Contribution Agreement and the Shareholders’ Agreement, Tata and ThyssenKrupp would each hold 50% of the shares in the newly created JV. Neither of the Parties would be granted relevant veto rights the other would not have, and the Parties would thus jointly control the JV. The JV would perform all the functions of an autonomous economic entity on a lasting basis. The JV would have sufficient own staff, financial resources and dedicated management for its operation and for the management of its portfolio and business interests. Furthermore, the JV would consist of pre-existing businesses and it would not be limited to exercising a specific function for its parents. It would have its independent market presence both upstream and downstream. It would also not have significant sale or purchase relationships with its parents. Finally, the JV would be set up for an indefinite period and thus intended to operate on a lasting basis. Therefore, the JV would be a full-functional joint venture.

(6) The operation thus constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Articles 3(1)(b) and 3(4) of the Merger Regulation.

3. UNION DIMENSION

(7) The combined aggregate worldwide turnover of the Parties is more than EUR 5 000 million (Tata: EUR 16 014 million; ThyssenKrupp: EUR 41 124 million) and the aggregate Union-wide turnover of each of the Parties is more than EUR 250 million (Tata: EUR […]; ThyssenKrupp: EUR […]). Tata and ThyssenKrupp do not both achieve more than two-thirds of their Union-wide turnover within one and the same Union Member State.

(8) The notified operation therefore has a Union dimension pursuant to Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. THE PROCEDURE

(9) During the Phase I investigation, beside requests for information to the Parties pursuant to Article 11 of the Merger Regulation, the Commission contacted a number of market participants (including customers and competitors of the Parties) and requested information from such third parties both through four questionnaires3 pursuant to Article 11 of the Merger Regulation and telephone calls.

(10) On 20 October 2018, the Commission informed the Parties of the concerns resulting from the preliminary assessment of the Transaction during a 'State of Play' meeting.

(11) Based on the results of the Phase I market investigation, the Commission found that the Transaction raised serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market and adopted a decision to initiate proceedings pursuant to Article 6(1)(c) of the Merger Regulation on 30 October 2018 (the ‘Article 6(1)(c) decision’).

(12) On 31 October 2018, the Commission provided a number of key documents to the Notifying Parties.

(13) Upon a request of the Notifying Parties of 8 November 2018, pursuant to Article 10(3) second sub-paragraph, first sentence, of the Merger Regulation, on 13 November 2018, the Phase II review period was extended by five (5) working days.

(14) On 19 November 2018, the Notifying Parties submitted their written comments on the Article 6(1)(c) decision (‘Comments on the Article 6 (1)(c) decision’).

(15) On 20 November 2018, at a state of play meeting, the Commission provided the Parties with the opportunity to discuss orally the main issues raised in the Comments on the Article 6(1)(c) decision, and indicated the matters on which it planned to focus its further investigative efforts.

(16) On 5 December 2018, given the failure of the Notifying Parties to provide certain requested information, the Commission adopted two decisions, addressed to Tata and ThyssenKrupp respectively, pursuant to Article 11(3) of the Merger Regulation, requesting them to supply certain documents as soon as possible and no later than 21 December 2018 and suspending the merger review time limit until receipt of the complete and correct information. The suspension lasted until 9 January 2019, at which date the requested documents were provided.

(17) During the Phase II market investigation, the Commission sent several requests for information to the Notifying Parties, as well as to third parties. The Commission held several calls with market participants, and it sent requests for information in the form of eleven questionnaires,4 in addition to those sent out before the initiation of the proceedings.

(18) On 5 February 2019 and following the results of the Phase II market investigation, a state of play meeting was held in order to inform the Notifying Parties of the preliminary results of the Phase II market investigation and the scope of the preliminary concerns regarding which the Commission planned to issue a Statement of Objections.

(19) On 13 February 2019, the Commission adopted a Statement of Objections (‘SO’), which was sent to the Notifying Parties on the same day. According to the SO, the Commission came to the preliminary view that the Transaction would likely significantly impede effective competition in the internal market within the meaning of Article 2 of the Merger Regulation due to (i) horizontal non-coordinated effects by eliminating an important competitive constraint in the market for the production and supply of automotive HDG in the EEA; (ii) the creation of a dominant position, or at least due to horizontal non-coordinated effects resulting from the elimination of an important competitive constraint, in the markets for the production and supply of metallic coated and laminated steel products for packaging in the EEA; and (iii) horizontal non-coordinated effects by eliminating an important competitive constraint in the market for the production and supply of grain oriented electrical steel in the EEA.5 The Commission’s preliminary conclusion was therefore that the notified concentration would be incompatible with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement.

(20) The Notifying Parties were granted access to the file on 14 February 2019. A data room was organised from 14 February to 21 February 2019 allowing the economic advisors of the Notifying Parties to verify confidential information of a quantitative nature, which formed part of the Commission’s file. A non-confidential report of the data room (First Data Room Report) was provided to the Parties on 21 February 2019. A revised version of this report was provided to the Parties on 22 February 2019. Subsequent access to the file was granted on 1 March, 21 March,

17 April and 3 May 2019. Another data room was organised from 21 to 25 March 2019. The Second Data Room Report was provided to the Parties on 26 March 2019.

(21) The Notifying Parties submitted their reply to the SO on 27 February 2019 (the ‘Reply to the SO’). They confirmed not to request a hearing.

(22) ArcelorMittal, industriAll (umbrella organisation of trade unions active in the mining, energy and manufacturing industries, including the steel sector), Salzgitter AG, Ardagh Group and IG Metall made applications to the Hearing Officer to be admitted as interested third persons in the proceedings and have been recognised as interested third parties by the Hearing Officer.

(23) All interested third persons were provided with a non-confidential version of the SO and Ardagh Group and Salzgitter AG submitted written comments to the SO, pursuant to Article 16(2) of the Commission Regulation (EC) 802/2004.6

(24) On 8 March 2019, a state of play meeting was held, during which the Commission provided the Notifying Parties with preliminary feedback following their Reply to the SO.

(25) On 12 March 2019, the Notifying Parties submitted draft commitments in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO.

(26) Upon request by the Notifying Parties on 18 March 2019, the period for the adoption of a final Decision was extended on 19 March 2019 by eight (8) working days pursuant to Article 10(3) second subparagraph, third sentence of the Merger Regulation, to allow for the Commission and the Parties to have sufficient time to discuss and thoroughly assess any formal remedy proposal that might be submitted by the Notifying Parties. Accordingly, the deadline for a Commission decision in this proceeding was extended until 13 May 2019.

(27) A Letter of Facts – evidence corroborating the objections set out in the SO – was sent to the Notifying Parties on 20 March 2019. The Notifying Parties submitted their comments on the Letter of Facts on 25 March 2019 (‘Reply to the Letter of Facts’).

(28) On 1 April 2019, the Notifying Parties submitted commitments pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO (the ‘Commitments of 1 April 2019’).

(29) On 2 April 2019, the Commission launched a market test of the Commitments of 1 April 2019.

(30) On 12 April 2019, a state of play meeting was held, during which the Commission provided the Notifying Parties with feedback following the market test of the Commitments of 1 April 2019.

(31) On 17 April 2019, the Notifying Parties were granted further access to file. Also on 17 April 2019, a meeting with the Notifying Parties was held, during which the Commission provided the Notifying Parties with preliminary feedback on their envisaged submission of revised commitments.

(32) On 23 April 2019, the Notifying Parties submitted revised commitments (the ‘Revised Commitments of 23 April 2019’).

(33) On 25 April 2019, the Commission launched a market test of the Revised Commitments of 23 April 2019.

(34) On 2 May 2019, a state of play meeting was held, during which the Commission provided the Notifying Parties with feedback following the market test of the Revised Commitments of 23 April 2019.

(35) The Notifying Parties were granted further access to the file on 3 May 2019 and 17 May 2019.

(36) On 8 May 2019, the Commission sent a draft Article 8(3) decision to the Advisory Committee with the view of seeking the Committee’s opinion on it.

(37) The meeting of the Advisory Committee took place on 27 May 2019.

5. INTRODUCTION TO THE STEEL INDUSTRY

5.1. Production process of flat carbon steel

(38) The Transaction primarily involves flat carbon steel products.

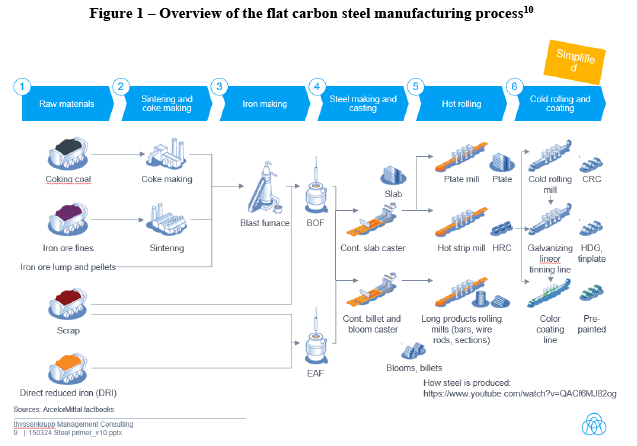

(39) The production of carbon steel typically consists of two main stages: (i) the production of crude steel and semi-finished products and (ii) the processing of semi- finished products into finished products. Each of the stages usually consists of several production steps.

(40) There are two principal processes for the production of crude steel and semi-finished products: (i) the so-called integrated or basic oxygen furnace route and (ii) the electric arc furnace (‘EAF’) route. In Europe, by far the most common method of producing crude steel for the production of finished flat carbon steel products is the integrated route.

(41) The integrated route involves the production of liquid iron from a mixture of iron ore, coke and limestone in a blast furnace. The liquid ore-based hot metal is subsequently refined into steel in a basic oxygen converter (‘BOF’) where scrap may also be added.7 During the BOF process, or in a separate secondary steelmaking in a steel ladle, the composition of the steel is adjusted to give it the desired qualities. That adjustment may include the use of appropriate quantities of various alloying elements. Finally, the liquid steel is cast and cooled in continuous casting machines to produce semi-finished carbon steel products known as slabs.8

(42) Finished flat carbon steel products are typically obtained from slabs through rolling9 and other further processing. There are three main stages in the production process of finished products: (i) hot-rolling, (ii) cold-rolling and (iii) coating. The finished products may typically be sold at the end of each of these stages. However, it is typical of the steel industry that significant volumes of the upstream products are used captively by major steel companies, such as the Notifying Parties, to produce downstream products.

(43) A schematic overview of the flat carbon steel production from the main raw materials to finished products is show in Figure 1.

5.2. Description of flat carbon steel products

(44) The semi-finished carbon steel products used as inputs in the finished flat product production are slabs. Slabs are typically produced from the hot liquid steel at the steel shop through continuous casting. Continuous casting starts when the molten metal is transported from the basic oxygen furnace or an electric arc furnace in a ladle and poured into a tundish that provides for a reservoir of liquid steel for the casting process. In the casting, the liquid steel is continuously cast through a mould to form the desired width and thickness of the slab, which is eventually cut into usable lengths at the end of the process.

(45) Quarto plates (‘QP’) are non-coiled hot rolled flat carbon steel products that are produced in dedicated plate mills after reheating the slabs to the desired temperature in reheat furnaces. QP differ from other hot rolled flat carbon steel products in their dimensions, being in particular thicker than strip products. They are used in applications that call for thick steel, such as at shipyards, boiler-making, nuclear and the oil & gas industry.

(46) Hot-rolled flat carbon steel products other than quarto plates (‘HR’) are strip products that are produced from slabs through hot-rolling in a strip mill after reheating the slabs to the desired temperature in reheat furnaces. HR products differ from QP in that they are thinner and are typically coiled at the end of the hot-rolling process. HR is also the input for downstream products such cold-rolled, hot-dip galvanised, electrogalvanised, organic coated and metallic-coated steel for packaging.

(47) Cold-rolled flat carbon steel products (‘CR’) are the result of the further rolling of HR in cold-rolling mills. Cold-rolling affects the basic properties of the product by reducing thickness, improving dimensional consistency and providing a smoother surface.

(48) CR is commonly used as an input in the production of coated steel products but may also be sold without further treatment into various applications, including construction, furniture manufacturing, welded tube making as well as packaging and machinery production.

(49) Galvanised flat carbon steel products (‘GS’) are flat carbon steel products that have been galvanised to improve their resistance to corrosion. Galvanisation involves coating the flat carbon steel strip with zinc, or a combination of zinc and other elements (for instance magnesium or aluminium).

(50) GS may be obtained through two main production processes: (i) hot-dip galvanisation and (ii) electrogalvanisation. Hot-dip galvanised products (‘HDG’) are produced through uncoiling and reheating a strip of CR (or sometimes HR), and feeding it through a bath of molten metal composed of zinc or a combination of zinc and other elements at an appropriate temperature. The dipping process results in a metallic coating on the steel substrate. Electrogalvanised products (‘EG’) are produced through the application of an electrolytic coating process which results in a zinc-containing coating on one or both sides of the strip.

(51) Metallic coated steel for packaging consists of thin CR coils or sheets that have been coated with a fine layer of another metal, primarily tin or chromium, resulting in either tinplate (‘TP’) or electrolytic chromium coated steel (‘ECCS’). TP and ECCS are primarily used in the food industry to produce protective packages (such as food cans) but can also be used in certain other packaging applications.

Laminated steel for packaging consists of metallic coated steel for packaging that has been further coated. Laminated steel is produced by applying layers of plastic film to the steel substrate.

5.3. Dynamics of the steel value chain

(52) The market position of flat carbon steel producers in the EEA is by and large determined by their primary steelmaking capacity (that is the capacity to produce liquid steel and slabs), characterised on the one hand by high barriers to entry and expansion and, on the other hand, by limited flexibility to efficiently reduce production levels. Likewise, the overall hot rolled capacity typically reflects the primary steelmaking capacity and, in the EEA, is the closest proxy for the producer’s position on the markets for finished flat carbon steel products.

(53) First, flat carbon steel production in the EEA is primarily based on the integrated route, that is to say the production of liquid steel through a combination of a blast furnace and a basic oxygen furnace. The EAF-route is relatively insignificant for the production of flat carbon steel products in the EEA and most producers have no EAF capacity for flat carbon steel in the EEA at all. This also applies to the Notifying Parties that produce flat carbon steel products solely through the integrated route.

(54) Second, the supply-side dynamics of primary steelmaking in the EEA is driven by the characteristics of the integrated route, which requires significant capital investments and which to a great extent relies on the simultaneous and constant operation of a blast furnace and a basic oxygen furnace, and often also a coking and a sintering plant.

(55) In the first place, high capital expenditure and environmental regulation act as an effective barrier to entry or expansion. The bulk of the costs of setting up greenfield steel capacity lie with the primary steel-making capacity, that is crude steel-making (coking and sintering of raw materials, blast furnace, basic oxygen furnace and steel ladles). This, compounded with modest demand growth in the EEA, is in line with the finding that, in recent years, the EEA saw no creation of new capacity for the integrated route technology.

(56) In the second place, the integrated route has limited flexibility when it comes to adapting production volumes to demand fluctuations: for technical and economic reasons blast furnaces need to be run at, or close to, maximum capacity. Restarting a blast furnace that has been blown down (that is where steel production has stopped) can also take several days or weeks, entails high one off costs, and becomes increasingly difficult the longer the blast furnace has been idled.

(57) Therefore, a steel manufacturer that bases its production on the integrated route is faced with limitations in its possibility to alter the production volumes of liquid crude steel and – since casting typically takes place immediately following the production of hot liquid steel – semi-finished products, notably slabs. To allow for viable operation, the producer needs to produce a certain volume with a blast furnace over extended periods of time, or not produce with that blast furnace at all. Where supply outstrips demand, the supplier has thus limited possibility to limit the output of blast furnaces in operation but can only decide to idle one or more blast furnaces altogether in order to align production and demand. On the other hand, the production process for finished products (strips) is not subject to as strict limitations from a technical point of view and can be altered more flexibly.

(58) Third, as a consequence of barriers to entry and expansion, as well as of inflexibility in scaling down production volumes, primary steelmaking capacity typically determines the overall available capacity for the entire flat carbon steel value chain. This said, downstream hot strip mills are not necessarily integrated with primary steelmaking facilities, as they can process slabs sourced from another site of the steel producer or sourced from third parties. This production model is occasionally observed in practice. However, compared to vertically integrated steel mills, production based on slabs produced off-site or by a third party appear to be of much more limited scope and potentially less efficient, and may be employed as a temporary measure to bridge the imbalances between upstream primary steelmaking output and the requirements for the production of downstream strip products. The vast majority of the hot strip mill capacity (‘HR capacity’) in the EEA mimics the primary steelmaking capacity (‘capacity for crude steel slabs’) located at the same or nearby site.

(59) Fourth, given the interdependence of primary steelmaking and hot strip mills, the competitive position of integrated flat carbon steel producers (that is other than non- integrated re-rollers11) is driven by their HR capacity. From the upstream perspective of primary steelmaking, HR is the direct output of processing slabs. From the perspective of supply of flat carbon steel, HR is both a final product that is sold to the market, and the input for all other finished flat products products (including CR, HDG, EG, organic coated (‘OC’) and steel for packaging). Thus, the competitiveness and the capacity for HR is on the one hand determined by primary steelmaking, and, on the other hands, also determines the conditions for the supply of downstream products.

(60) Fifth, HR can either be sold on the merchant market or further processed into downstream finished products by the integrated producer. An integrated producer active on the various levels of the flat carbon steel value chain is thus faced with a choice as to at which level of the production chain it sells its steel. Typically, the value of steel increases the further it is processed and, moreover, a producer that has installed capacity for the downstream products and needs to pay for the fixed costs so incurred may, in general, be incentivised to employ the existing capacity to produce products on the downstream market. Therefore, an integrated steel manufacturer may be incentivised – to the extent possible in the prevalent market conditions – to direct its HR products into further processing internally. The steel kept by the integrated steel producer for further processing in its own processing facilities is part of the so- called ‘captive market’ of steel, as opposed to the ‘merchant market’, where the steel is sold by the integrated producer to other steel manufacturers (notably re-rollers), distributors and industrial customers.

(61) However, steel producers do not reserve a given primary/HR capacity solely to the production destined for the merchant market, or for captive use, but use their plants to feed both channels. Given the aforementioned lack of flexibility in adapting the output to demand fluctuations, conditions on the merchant market will not only influence the volume to be sold to third parties, but also HR for captive use. The producer may at least partly reallocate capacity to the channel that provides a more attractive return. For example, if the prices on the merchant market for HR drop, the supplier may reallocate more capacity to captive production for downstream products with a higher added value. The same may occur where there is a shortage on a downstream market, for example for HDG. In other words, the suppliers may leverage their production available to the merchant market in order to react to developments affecting the downstream markets, and vice versa. Moreover, suppliers may align their pricing policy for merchant sales of HR and for the sales of downstream products based on HR (for example, by virtue of the ‘base price plus extras’ pricing model).

(62) Consequently, the higher its overall HR production, the stronger the supplier’s pricing power both directly in the market for HR and in the related downstream markets. Therefore, the competitive assessment should not isolate the suppliers’ position in the merchant channel from the remainder of their HR production and capacity.

(63) Finally, non-integrated producers (‘re-rollers’) that source HR coils and then further process them into downstream products such as CR and GS also play a role in the downstream CR and GS markets in addition to the integrated producers. Re-rollers are typical customers of HR coils on the merchant market and they thus depend on the supply of the input HR coils on the merchant market by the EEA-based integrated producers (and/or imports). Hence, their market position is affected by the availability and conditions of the supply of HR on the merchant market. The most prominent re-roller in the EEA is Marcegaglia in Italy.

5.4. Trade defence measures against steel imports

5.4.1. Legal framework

(64) Despite the reduction of custom tariffs on steel preogressively achieved within the WTO, at present, a wide number of carbon steel products entering the EU also are subject to trade defence measures (‘TDIs’).

(65) In line with public international law and trade agreements, including in particular the GATT/WTO agreements, trade defence measures can take the form of anti- dumping,12 anti-subsidy13 or safeguard measures14.

(66) Anti-dumping measures are imposed on imports that are found to be dumped and cause injury to a Union industry. Dumping is defined as selling a good for export at less than its normal value. The normal value is either the product's price as sold on the home market of the non-EU company, or a price based on the cost of production and profit.

(67) Safeguard measures can be applied if, as a result of unforeseen developments, a product is being imported into the EU in such increased quantities and/or on such terms and conditions as to cause, or threaten to cause, serious injury to EU producers of like or directly competitive products. Safeguard measures may only be imposed to the extent and for such time as may be necessary to prevent or remedy the injury.

(68) Anti-dumping measures are always adopted in relation to imports from specific countries, safeguard measures in principle on imports from all countries (this is called erga omnes).

(69) Section 5.4.2 aims to provide a brief overview of the trade defence measures currently in place. The effect of these measures on the competitive environment in the specific product markets is assessed in more detail in Sections 8.3.3 and 8.3.4.

5.4.2. Safeguard measures targeting imports of steel products

(70) As concerns the steel sector, in 2003 the Commission imposed definitive safeguard measures in relation to seven steel products.15 These safeguard measures were terminated shortly thereafter still in 2003,16 in view of the fact that the tariff rate quotas were significantly underutilised for six of the seven products and that imports only marginally exceeded the quota for hot-rolled coils, as well as the repeal of the United States’ steel safeguard measure.

(71) On 26 March 2018, the Commission initiated ex-officio an investigation into 26 different steel product categories17. On 28 June 2018, the Commission extended the product scope to two additional product categories.18 Provisional safeguard measures were imposed on 18 July 201819 and became definitive with certain modification on 2 February 2019.20 The definitive safeguard measures apply to 26 categories of steel products including flat products, long products and tubes.

(72) The measures took the form of a tariff-rate quota (‘TRQ’) calculated as the average imports in the period 2015-2017 plus 5%21 with an out-of-quota duty of 25% which would apply only once the TRQ in a certain product category is exhausted. The Commission considered that this design was appropriate to limit the increase of imports to a level that is unlikely to cause serious injury to the Union industry while ensuring that traditional trade flows are maintained and that existing user and importing industries are sufficiently supported.

(73) As also stressed in the recitals to the relevant regulation, the safeguard measures have been adopted against the background of the adoption of safeguard measures by other countries, the global 25% tariff that the US have imposed on steel imports (with a limited number of origin exceptions subjected to very restrictive quotas) and the 50% tariff on Turkish imports and to deal with a significant increase of steel imports into the Union, accelerated as a result of those measures.22

(74) In this context, it is also useful to recall that provisional safeguard measures on steel have been adopted by Canada. The Eurasian Economic Union23 has also initiated a procedure for the adoption of safeguard measures.

(75) For the purpose of the assessment of the Transaction, it can be mentioned that the definitive safeguard measures imposed by the Commission target also the import of flat steel products. In particular, safeguard measures will affect all products for which the Commission raises concerns, targeting imports of steel for packaging and HDG steel products including HDG for automotive applications.

(76) As concerns corrosion resistant sheets, including HDG, the safeguard measures calculate the relevant quotas distinguishing between two sub-categories, namely products subject to anti-dumping duties, see below recitals (79) and (80), and products that are not subject to anti-dumping duties (including automotive).

(77) Among other steel products, the safeguard measures concern both standard metallic coated sheets products, which are subject to anti-dumping duties as referred to below at recital (80), and non-standard metallic coated sheet products which are not subject to anti-dumping duties.24 This latter category also includes products manufactured specifically for the automotive industry, based on precise product specifications and subject to long-term contracts. For non-standard metallic coated products including specialty products purchased by the automotive industry, suppliers need first to obtain a certification necessary to supply the industry over a long time period, based on a just-in-time system.25 For this product category, the regulation acknowledges that there is a risk that some specific product types are crowded out from the free of duty quota by standard products that can be stockpiled at the beginning of the year. Furthermore, the standard types of products under this product category are currently subject to anti-dumping duties, which also have an impact on future import developments as well as quota allocation, based on what is explained above. The fact that these more specialised products were not covered in the industry's request for anti-dumping measures is also an indication that these products should be considered separately from the standard types of products.26 The safeguard measures concern also the relevant markets for metallic coated steel for packaging.

5.4.3. Anti-dumping measures on imports of steel products

(78) The Commission has also conducted a number of anti-dumping investigations with regard to different steel products in recent years.

(79) At present, definitive anti-dumping measures are imposed, amongst others, on HR products from China,27 CR products from China and Russia,28 corrosion resistant steel products, including HDG, originating from China29 and grain oriented flat- rolled products of silicon-electrical steel (‘GOES’) from China, Japan, Korea, Russia and the US.30

(80) For corrosion resistant steel products, including HDG, the anti-dumping regulation imposes anti-dumping duties, but the anti-dumping regulation on GOES establishes minimum import prices.

(81) As the trade defence measures on steel for packaging and HDG steel cover respectively all or some of the major steel producing and steel exporting countries, any assessment of the extent to which imports of these products may exert competitive pressure on EEA-based flat carbon steel producers and, in particular the merged entity post-Transaction, must be made in light of the situation as affected by the definitive safeguard measures and anti-dumping duties.

6. PARTIES’ ACTIVITIES

6.1. Tata Steel

(82) Tata produces and sells a range of carbon steel products (including HR, CR, metallic coated and laminated steel for packaging, GS and OC) as well as both grain-oriented electrical steel (‘GOES’) and non grain-oriented electrical steel (‘NGOES’). Tata further produces further downstream products such as carbon steel tubes and steel elements for construction.

(83) Tata’s plants are located predominantly in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands where it has its two integrated steelmaking plants in Port Talbot (United Kingdom) and IJmuiden (Netherlands). Further, it has also a number of downstream finishing plants elsewhere in Europe (in Belgium, France, Germany and Sweden).

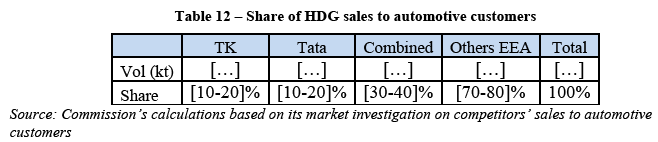

(84) Tata produces liquid steel and semi-finished products (slabs) at its integrated steelworks in IJmuiden and Port Talbot. Tata processes slabs into HR products at those integrated steelworks and at the hot strip mill in Llanwern (United Kingdom).

(85) GS, including in particular HDG, is manufactured in IJmuiden (Netherlands), Llanwern (United Kingdom), Shotton (United Kingdom) as well as in Tata’s plants in Ivoz-Ramet (the ‘Segal’ line, Belgium) and Maubeuge (France). Metallic coated and laminated steel products for packaging are produced in IJmuiden (Netherlands), Trostre (United Kingdom) and Duffel (Belgium).

6.2. ThyssenKrupp

(86) ThyssenKrupp, headquartered in Germany, is one of Europe’s major flat carbon steel producers and it is active throughout the flat carbon steel value chain from primary steel production to coated finished products.

(87) ThyssenKrupp produces and supplies a range of flat carbon steel products (including HR, CR, metallic coated and laminated steel for packaging, GS, OC, GOES and NGOES products).

(88) ThyssenKrupp’s activities are centered in Germany, and its integrated plants are all located in Duisburg (Germany). It also has a number of downstream finishing plants elsewhere in the EEA, including in France, Germany and Spain.

(89) ThyssenKrupp produces liquid steel and semi-finished products (slabs) at its integrated steelworks in Duisburg. ThyssenKrupp also has a stake in Hüttenwerke Krupp Mannesmann (‘HKM’) – a joint venture between ThyssenKrupp, Salzgitter and Vallourec – that is also located in Duisburg and that produces liquid steel and slabs. ThyssenKrupp processes slabs into HR products at its integrated steelworks in Duisburg and at the hot strip mill in Bochum (Germany).

(90) ThyssenKrupp manufactures GS, including in particular HDG, predominantly in Germany at its plants in Duisburg, Bochum, Dortmund, Finnentrop, Kreuztal (Eichen and Ferndorf) but also in its plant in Sagunto (Spain). Metallic coated and laminated steel products for packaging are produced in Adernach (Germany) at the Rasselstein plant.

7. PRODUCT MARKET DEFINITION

7.1. Introduction

(91) The present case concerns flat carbon steel products.

(92) In light of the activities of the Notifying Parties, the Transaction gives rise to overlaps with regard to the production and supply of semi-finished flat products (slabs).

(93) Further, as regards finished products, the Notifying Parties’ activities overlap for most products in the flat carbon steel value chain in the EEA, namely HR, CR, GS, metallic-coated and laminated steel products for packaging and OC. Their activities also overlap in the production and supply of fully-finished electrical steel (both GOES and NGOES) in the EEA.

(94) However, on the basis of the competitive concerns identified, the relevant products for the purpose of this Decision are (i) HDG supplied to the automotive industry and

(ii) metallic-coated and laminated steel products for packaging. The preliminary concerns raised with regard to electrical steel were not confirmed by the further investigation. Electrical steel is therefore not discussed further in this Decision.

7.2. Broad categories of steel

(95) In past decisions,31 the Commission has distinguished broad categories of steel products based, on the one hand, on the chemical composition of the steel (metallurgical characteristics) and, on the other hand, on the physical shape of the products. Based on their chemical composition, the Commission has distinguished four broad categories of steel products: (i) carbon steel, (ii) stainless steel, (iii) specialty steel and (iv) electrical steel. Based on their physical shape, the Commission has distinguished between (a) flat and (b) long products.

(96) The present case concerns only flat carbon steel products.

7.3. Production and supply of carbon steel

7.3.1. Introduction

(97) Carbon steel is iron- and carbon-based steel containing no or small amounts of alloying elements. That is in contrast to the other types of steel, which typically contain considerable amounts of alloys.

(98) Electrical steel has certain specific electromagnetic properties and, in order to achieve these properties, it needs to have a suitable chemical composition that differs from that of other types of steel. The main difference between electrical steel and (non-electrical) carbon steel in terms of chemical composition is silicon content, which is higher in electrical steel.32 In addition, the amount of certain other alloying elements, such as carbon, aluminium, nitrogen, sulphur and titanium need to be in different – often stricter – ranges in electrical steel compared to carbon steel.

(99) The chemical composition of steel is primarily determined in the liquid steelmaking stage, in particular in the BOF process, or during secondary steelmaking in steel ladles.

7.3.2. The Notifying Parties’ view

(100) The Notifying Parties submit that – despite their different chemical compositions – there is a significant level of supply-side substitutability between electrical steel and carbon steel at the liquid steel / semi-finished products and hot-rolling stages. The Notifying Parties in general agree with the segmentation followed in previous cases. However, they submit that electrical steel should not be considered as a separate broad category of steel on the basis of its chemical composition. Instead, according to the Notifying Parties, electrical steel should be included in carbon steel due to, for instance, supply-side substitutability.

(101) The Notifying Parties acknowledge that the different chemical composition of electrical steel products puts somewhat different requirements on production facilities compared to the production of carbon steel. In particular, at the hot end of the production, cooling of cast electrical steel needs to be slow as the high silicon content could otherwise result in stress formation (cracking) in the steel. Consequently, the production of electrical steel requires a hot-connect facility between the casting of semi-finished products (slabs) and their further processing, unlike carbon steel. According to the Notifying Parties, the hot-connect facility can consist of a cover over the slabs in order to keep them at higher temperature and to slow down the cooling process. Alternatively, a direct-rolling method where no slabs are created but the cast steel is immediately rolled into HR can be used, […].

7.3.3. The Commission’s assessment

(102) Overall, the results of the market investigation and the evidence available to the Commission do not give reasons to depart from the finding in previous cases that electrical steel should be distinguished from other broad groups of steel on the basis of its chemical composition.

(103) Nonetheless, for the purpose of this Decision, the Commission considers that it is not necessary to conclude specifically on a possible separation between the categories of carbon and electrical steel for product market definition purposes as the outcome of the competitive assessment remains the same under all alternatives. In particular, the question of whether carbon steel and electrical steel belong to the same or separate markets is only relevant for the upstream levels of semi-finished products, hot-rolled products and cold-rolled products (both carbon steel and electrical steel products go through these production steps).

(104) Specifically, the question is not relevant for defining the downstream product market for hot-dip galvanised steel for automotive applications or those for metallic-coated and laminated steels for packaging since electrical steel is not used for the production of hot-dip galvanised or packaging steels.33

7.4. Production and supply of flat carbon steel products

7.4.1. Introduction

(105) As explained above in Section 5.1, the production of flat carbon steel in principle consists of two main phases: the production of semi-finished products (slabs) and the production of finished products (rolled products). Semi-finished products are produced at the end of the liquid steel production phase through casting in continuous casters and are eventually cut into slabs. Finished products are obtained from slabs through rolling and other further processing such as coating.

(106) The Commission notes that the Notifying Parties […].

7.4.2. The Commission’s decisional practice

(107) Within steel products, the Commission has held in previous cases that flat products give rise to distinct product markets, as opposed to long steel products.34

(108) The Commission has in previous decisions concluded that flat carbon steel products can be divided into distinct product markets based on the production steps. In line with this, the Commission has concluded that the following finished flat carbon steel products constitute distinct product markets: (i) quarto plates, which are produced in specific quarto (four-stand) mills (‘QP’);35 (ii) hot-rolled products excluding quarto plates (‘HR’); (iii) cold-rolled products (‘CR’); (iv) galvanised steel (‘GS’);

(v) metallic-coated steel for packaging; and (vi) organic coated (for instance, painted) steel (‘OC’). For some of the products, the Commission has also considered further segmentations.36

(109) The Notifying Parties largely agree with the segmentation in past Commission decisions. However, in their view, certain additional segmentations, in particular with regard to GS and metallic-coated steel for packaging, are not relevant. The Notifying Parties’ arguments and the results of the market investigation are discussed separately in relation to each of the products that are relevant for the assessment of this Transaction.

7.5. Production and supply of galvanised flat carbon steel products / automotive HDG

7.5.1. Introduction

(110) Galvanised flat carbon steel products (‘GS’) are flat carbon steel products that have been galvanised to improve their resistance to corrosion. Galvanisation involves coating the flat carbon steel strip with zinc, or a combination of zinc and other elements (for instance magnesium or aluminium).

(111) GS may be obtained through two main production processes: (i) hot-dip galvanisation and (ii) electrogalvanisation. Hot-dip galvanised products (‘HDG’) are produced by uncoiling and reheating a strip of CR (or sometimes HR) and feeding it through a bath of molten metal composed of zinc or a combination of zinc and other elements at an appropriate temperature. The dipping process results in a metallic coating on the steel substrate. Electrogalvanised products (‘EG’) are produced through the application of an electrolytic coating process which results in a zinc- containing coating on one or both sides of the strip.

(112) GS products are used in various applications where superior resistance to corrosion is needed, including in the automotive industry, construction industry and in various engineering applications. GS is also used as a substrate in the production of organic coated flat carbon steel products.

(113) According to the Parties’ estimates, the total EEA merchant market volume of GS was 28.4 million tonnes in 2017, of which 26.2 million tonnes were HDG and 2.2 million tonnes EG. A clear majority of the GS merchant market in the EEA thus consists of HDG.37

(114) The largest single user of GS in the EEA is the automotive industry, which uses almost half of all GS in the EEA.38

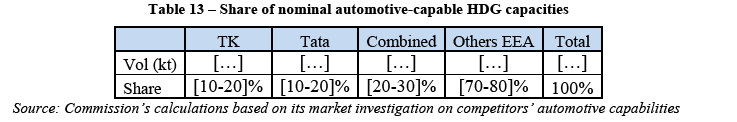

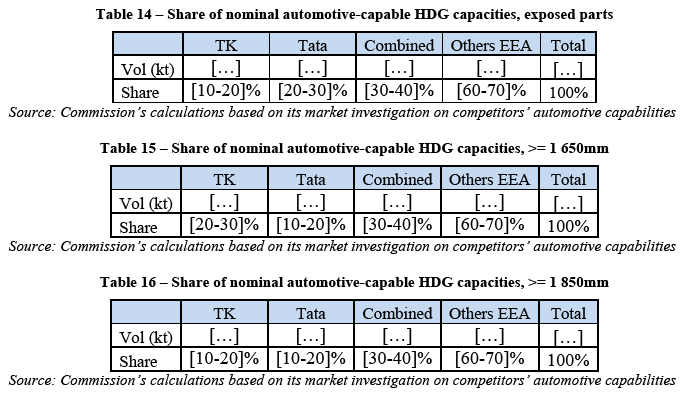

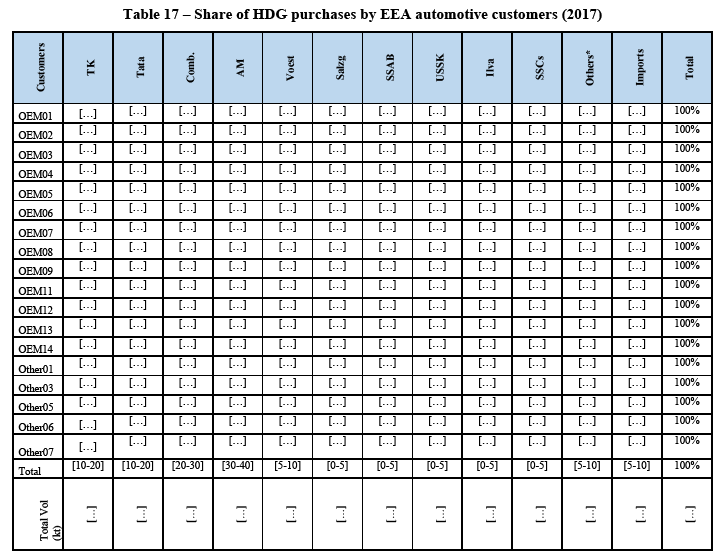

(115) The Commission further observes that the Notifying Parties appear to be more focused in supplying GS to the automotive industry, and their share of the EEA supply of GS to the automotive industry of [30-40]%39 is higher than their share of the overall GS supply in the EEA of [20-30]%.40 In line with this, and as explained in more detail in Section 9.3, the Notifying Parties estimate also having higher market shares if only considering the supply of HDG to the automotive industry ([20-30]%) compared to the overall share of the supply of HDG in the EEA ([20-30]%).41

(116) In light of the focus of the Notifying Parties, and considering the results of the market investigation, the Commission will examine whether or not the production and supply of HDG to the automotive industry constitutes a distinct product market, separate from the production and supply of HDG for other applications.

7.5.2. The Commission's decisional practice

(117) In the recent ArcelorMittal/Ilva case,42 the Commission concluded that there was at least a serious possibility that the production and supply of HDG and the production and supply of EG constitute distinct product markets. The Commission nonetheless did ultimately not conclude on the question.43

(118) In the ArcelorMittal/Ilva case, the Commission did not examine whether or not a distinct market for the production and supply of HDG to the automotive industry was warranted. The parties in that case did not have a particular overlap in such supplies, and in particular Ilva was not significantly supplying steel to the automotive industry. Nonetheless, the decision in the case acknowledges and discusses both commodity and high-end HDG even if it does not define separate markets for them.44

(119) In case M.7155 – SSAB/Rautaruukki, the Commission found that it was likely that high-strength steels (‘HS’) and wear resistant steel (‘WR’) belonged to a market separate from commodity (‘standard’) flat carbon steel. The Commission nonetheless did not conclude on the exact market definition.45 ThyssenKrupp supported in SSAB/Rautaruukki the finding of a separate product market for HS and WR.46

(120) Nonetheless, the decision in SSAB/Rautaruukki does not discuss GS in detail because of the limited presence and complementarity between SSAB and Rautaruukki in those products.47

7.5.3. The Notifying Parties’ views

(121) The Notifying Parties submit that a further segmentation of GS between HDG and EG is not warranted, mentioning in this regard that products are technically interchangeable, that customers do switch and that cost and price differences are small.48 The Notifying Parties moreover submit that the Commission’s finding that the inclusion of EG would not affect the competitive position of the JV in the galvanised automotive steel market segment (or would in fact slightly increase it) is insufficient to render the question of whether (automotive) EG is considered to form part of the same market as (automotive) HDG irrelevant, since there are significant spare capacities for (automotive) EG in the EEA.49

(122) The Notifying Parties further submit that there is no distinct market for automotive HDG. In particular, the Notifying Parties submit the following general arguments:

(a) The Commission did not define a separate automotive HDG market in its precedents, including in particular the recent in-depth investigation in ArcelorMittal/Ilva;50

(b) Vertical integration is not a key characteristic or requirement for the supply of HDG to the automotive industry, and even if it were, this would be unrelated to the question of whether automotive HDG constitutes a separate product market.51 Moreover, customers mentioning the importance of ‘control over the production chain and access to high quality substrate’ should not be misinterpreted to mean vertical integration, as such control and access can also be achieved without vertical integration;52

(c) The fact that automotive customers are being supplied through long-term contracts does not demonstrate that there is a separate market for automotive steel as some other customers also prefer to be supplied through annual contracts;53 while the use of annual price agreements implies lower volatility and a lag compared to spot prices, this does not justify defining separate markets as steel supply can be redirected from the spot market to the automotive segment at the next re-contracting opportunity;54

(d) Internal documents considering automotive separately are irrelevant to product market definition and are rather a reflection of different sales personnel and ‘economic conditions’;55

(e) Different treatment of specialised products under trade defence measures does not constitute evidence for a separate automotive HDG market; the differentiation under the trade defence measures is between passivated and non-passivated HDG products, which does not correspond to the automotive vs. non-automotive distinction;56

(f) The ability to price-discriminate between automotive and non-automotive customers is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for finding a separate product market, as this would also require finding limited supply-side substitution; and in any case, the evidence presented in the SO to demonstrate the presence of price discrimination is in fact inconclusive;57

(g) Differing gross margins do not constitute evidence for separate product markets;58

(h) Similar price trends for automotive and non-automotive steel are evidence of both supply-side and demand-side substitution.59

(123) The Notifying Parties also submit the following demand-side arguments in this regard:

(a) Customers are not dependent on specific grades of steel; they can use different types of steel as well as other substitute materials such as aluminium instead;60

(b) While automotive customers may require homologation, other customers also have such requirements and ‘there are no barriers to steel producers meeting such requirements’;61

(c) Homologation is not a barrier preventing demand-side substitution, as automotive customers typically identify potential steel suppliers one or two years prior to the start of production of any given model;62

(d) Conditions of supply do not differ based on end-user industry;63 other industries also require just-in-time deliveries, tight specifications and tailored products.64

(124) The Notifying Parties also submit the following supply-side arguments in this regard:

(a) Different production lines are not required as both automotive and non- automotive customers can be supplied from the same line without adjustments65 or with minor investments of at most EUR 8 million per line;66

(b) While some automotive steel types, such as AHSS with a tensile strength exceeding 800 MPa, do require special production assets, these facilities can be and are also being used to produce other types of steel;67

(c) Many of the steel types sold to automotive customers can also be sold to non- automotive customers68 or are in fact sold to non-automotive customers;69 or, more specifically, around one-half of HDG sold to automotive customers is of a type that is also sold to non-automotive customers.70

(125) The Notifying Parties further submit that aluminium is a substitute for automotive HDG steel given that its higher cost is compensated by CO2 emission savings and mentioning its use in a range of non-luxury car models.71

7.5.4. The Commission's assessment

7.5.4.1. Framework of the assessment

(126) The Commission’s assessment of the definition of a relevant product market typically takes into account both demand- and supply-side substitution. In the field of steel, supply-side substitution has typically played a central role in the Commission’s assessment due to the specificities of the markets in question.

(127) Furthermore, a product market might be narrowed in the presence of distinct groups of customers. A distinct group of customers for the relevant product may constitute a narrower, distinct market when such a group could be subject to price discrimination. This will usually be the case when two conditions are met: (a) it is possible to identify clearly which group an individual customer belongs to at the moment of selling the relevant products to him, and (b) trade among customers or arbitrage by third parties should not be feasible.72

(128) In this section, after discussing the likely distinction between EG and HDG, the Commission will address both demand- and supply-side factors, as well as the more general arguments raised by the Notifying Parties. Finally, the Commission will assess the Notifying Parties’ argument regarding the alleged substitutability of aluminium with automotive HDG.

(129) Furthermore, the Commission notes that the definition of a relevant market is always performed in the context of a particular case. The Notifying Parties have in this respect claimed that the Commission is departing from its precedent, in particular in that it did not consider automotive HDG in its most recent flat carbon steel case, M.8444 – ArcelorMittal/Ilva. Nonetheless, the Commission recalls that the precedent did not exclude the finding of a separate market for automotive HDG and in any event primarily concerned commodity steel, whereas in the present case both of the Parties proved to have significant sales to the automotive industry. Furthermore, the market distinction in this context was also emphasised by market participants as explained in this Decision.

7.5.4.2. EG and HDG likely constitute distinct markets

(130) As noted in Section 7.5.1, there are two different types of galvanised flat carbon steel: (i) hot-dip galvanised steel (‘HDG’) and (ii) electrogalvanised steel (‘EG’).

(131) As already explained, in the recent ArcelorMittal/Ilva case73 the Commission concluded that there was at least a serious possibility that the production and supply of HDG and the production and supply of EG constitute distinct product markets, although it ultimately did not conclude on the question.74

(132) It is similarly unnecessary for the Commission to conclude in this case whether or not HDG and EG constitute distinct product markets or whether an overall GS market (HDG+EG) should be considered. This is because, on the one hand, Tata is not active in EG and, on the other hand, the outcome of the competitive assessment would be the same regardless of whether a distinct HDG market or a GS (HDG+EG) market is considered.

(133) In this respect, the Commission observes that, as also noted in Section 7.5.1, HDG constitutes by far the majority of the overall GS production and supply in the EEA. Based on figures provided by the Notifying Parties, the total volume of EG supplied in the EEA was approximately 2.2 Mt in 2017 while the total volume of GS supplied was 28.3 Mt. EG thus constituted less than 8% of the total GS volume, HDG making up over 92%.75

(134) Much of the EG volume is used in the automotive industry. Based on a submission by the Notifying Parties, approximately 1.3 Mt of the EG volume would be used in the automotive industry. This is nonetheless less than 10% of all GS used in the automotive industry, based on the submission by the Notifying Parties.76

(135) ThyssenKrupp is active in the production and supply of EG and it supplied [20-30]% of all EG in the EEA in 2017. As regards supplies to the EEA automotive industry, ThyssenKrupp’s share for EG was [30-40]% in 2017 ([30-40]% including all sales to SSCs as well). These compare to the Parties’ combined share of the supply of all HDG in the EEA that was [20-30]% in 2017 and their combined share of supply of HDG to the automotive industry that was [20-30]% based on the Notifying Parties’ submission.77

(136) The Commission observes that ThyssenKrupp’s market share in the supply of EG was higher than the Notifying Parties’ combined market share in the supply of HDG in the EEA in 2017 – both if considering the overall supply in the EEA or the supply to the automotive industry. Therefore, including EG in the same market with HDG would increase the Notifying Parties’ combined market share. Nonetheless, given the small volume of EG compared to HDG and the consequently small part of GS that it represents, the Commission considers that the outcome of the competitive assessment would likely be the same regardless of whether HDG is considered separately or if GS (HDG+EG) is considered.

(137) Moreover, the market investigation revealed strong evidence that EG and HDG are not substitutable and if anything, substitution occurs from EG to HDG, rather than the reverse, which is what would be required for EG to impose a constraint on HDG.

(138) For instance, a customer suggests that there is no demand-side substitutability: ‘[f]rom [its] perspective, HDG and EG are not substitutable’.78 This concurs with Tata’s internal document that explains […].79

(139) Furthermore, there is evidence that substitution, if any, occurs from EG to HDG, rather than the other way round. For instance, a news article describes Tata’s newly- developed HDG steel as allowing ‘producers of EG to switch to HDG without giving up on a high-quality coating result’.80 Similarly, a Tata press release of 18 November 2015 states: ‘In order to help car manufacturers switch from electrogalvanised steels to hot-dip galvanising, which costs around € 30 less per vehicle, Tata Steel is currently developing a special additional coating. This pulling aid is intended to provide better performance in pressing the components by minimising abrasion and zinc fouling.’81

(140) These statements are in line with a technical expert’s publication titled ‘Application of continuous galvanized steel in Europe: driving forces and game changer’, which states: ‘So the pressure on reduction of material costs is extremely high. In respect to continuous galvanizing this was and is a major driving force to switch from electrogalvanized (EG) to hot-dip galvanized (HDG) steel sheet. Many developments from the steel industry did not withstand this economic pressure. Products based on EG like Zink-Nickel coatings, in use at Opel for more than 10 years, and duplex coatings like Corrosion Protection Primer (CPP: EG coating covered by a thin organic coating with embedded Zn particles to enable spot weldability) phasing out at Daimler, had a limited life cycle mainly due to higher product costs.’; ‘For several years also electrogalvanized ZnNi-coatings and duplex coatings (weldable thin organic coatings on electrogalvanized steel sheet) were in serial production (Opel, Daimler). Due to several reasons (cost, corrosion protection, spot weldability) the application has been stopped.’82

(141) Regarding specifically switching patterns between EG and HDG, the Parties claimed that switches from HDG to EG would also occur.83 However, the evidence presented relates to Mexico and South Africa, not the EEA, the Parties only having a suspicion that this could also be the case for one production plant of one automotive customer in Spain. The Commission therefore considers this evidence to be unpersuasive, especially in view of the broadly observed switching trend from EG to HDG (and not the reverse) in the EEA.

(142) This shows that the Parties, customers and independent experts all either consider EG and HDG to be separate markets, or consider that substitution is only relevant from EG to HDG, rather than the reverse.

(143) In any event, the assessment in this Decision is conservatively based on HDG, potentially underestimating the Parties’ relevant market position. This is because the Parties’ combined market share in a potential HDG+EG market would likely be higher than that in an HDG market only due to ThyssenKrupp’s high market presence there. For the reasons set out above, namely the large share of GS that is accounted for by HDG and the Parties’ similar combined market shares in HDG and EG, the outcome of the competitive assessment would apply to both a distinct HDG market and an overall GS (HDG+EG) market.

(144) As regards the Notifying Parties’ observation that there are significant spare capacities for EG, it is clear that these do not constrain producers of automotive HDG since (i) EG is significantly more expensive than HDG;84 (ii) from the supply side, switching from HDG to EG is not sufficiently cheap and swift; and, consequently, (iii) if anything, switching occurs from EG to HDG rather than the reverse.

7.5.4.3. HDG: The automotive industry has specific technical requirements for galvanised steel

(145) HDG is used in the production of cars in various different applications, including the exterior (exposed) and interior (non-exposed) parts of the car. Depending on the part of the car, the steel used is subject to a number of different requirements. These requirements range from surface quality to specific requirements on the strength and crash behaviour of the steel.

(146) Exposed parts typically need to achieve a particularly good surface quality to contribute to an appealing and spotless look of the finished car. High formability is required of the steel input for achieving the desired design, and particularly wide coils may be needed to produce desired surfaces of the car without weld seams. At the same time, exposed parts need to be resistant against dents and the corrosive effects of the elements and road salt. ThyssenKrupp notes the heavy conditions under which exposed parts need to perform: ‘The body of a car has to endure many things: swirled up stones, rain and road salt. It must not rust – even where scratches have left their mark.’85 Tata further explains in its internal documents some of the requirements on exposed parts, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Tata internal document: Requirements on auto exposed parts86

[…]

(147) At the same time, many non-exposed but structurally critical parts have specific requirements in terms of crash behaviour (for instance energy absorption) and hardness of the steel. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, some safety-critical non- exposed parts need to absorb energy to cushion a crash, while other parts need to be able to keep their shape and fight intrusion to protect passengers.

Figure 3 – Tata internal document on requirements on non-exposed crash structures87

[…]

Figure 4 – Tata internal document on requirements on non-exposed passenger cell88

[…]

(148) In addition to safety, looks and other considerations related to the functionality of a car, car manufacturers also consider the weight of the steel structures. A significant part of a car’s weight comes from the steel components, and the weight of a car largely determines its fuel economy and environmental friendliness – as a ThyssenKrupp internal document notes, ‘[v]ehicle weight is one of the most important emission drivers’.89 High strength steels can be employed to reduce the weight of a car as they can help achieve the same strength with a reduced amount of steel and, hence, reduced weight. In line with this, a customer notes: ‘[t]he automotive industry requires steel of higher strength, lighter proportional weight and superior quality, if compared to that used in more general applications such as the construction of buildings.’ 90

(149) To achieve the required specifications, car manufacturers use different grades of steel in different applications. While conventional mild grades may find use in less critical applications, specialty steels are more commonly used in the critical components of a car. For instance, boron steel may be used in the safety shell that must not deform in a crash, dual-phase steels can be used in the crash structures that need to absorb energy in a crash and dent-resistant bake-hardened steels can be used in exposed parts, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Tata internal document on specific grades of steel used in a car91

[…]

(150) The Notifying Parties submit that many of the steel types sold to the automotive industry are also sold for other applications. In particular, the Notifying Parties submit that steel sold to automotive customers can be classified into two broad categories: (i) ‘general automotive steel’, the production of which does not require specific equipment; and (ii) ‘higher strength automotive steel’ (high strength AHSS). Further, the Notifying Parties submit that general automotive steel consists of: (i.a) steel types sold to both automotive and non-automotive customers; and (i.b) steel types sold predominantly to automotive customers.

(151) Overall, the Notifying Parties submit that […] of all HDG they sell to automotive customers is of a type that is sold to both automotive and non-automotive customers,92 though they have not provided detailed evidence to support their claim.

(152) The Commission finds the following evidence to the contrary.

(153) Based on the updates of the transaction-level datasets responsive to RFI 2 submitted in reply to RFI 36 and focusing on 2017 sales, the Commission finds that […] of the volumes sold by Tata to automotive customers were customer-specific grades, which are not sold to any other customers. This contrasts with other customer categories that purchase no or very limited volumes of customer-specific grades. For instance, the customer category Construction purchases less than […] (by volume) as customer-specific grades. The only other customer category apart from automotive customers that purchases more than […] of its volumes as customer-specific grades is the category Trading/SSC.93 However, as this group consists of resellers, these products are likely resold mainly to automotive customers as Tata makes virtually no direct sales of customer-specific grades to customers other than automotive, as described above.

(154) Focusing on Tata’s sales of non-customer-specific grades to automotive customers, the Commission finds that, excluding internal sales and sales to Trading/SSCs, non- customer-specific grades that are predominantly sold to automotive customers (meaning that more than 90% by volume of steel of those grades are sold to automotive customers) represent approximately [90-100]% of Tata’s sales of such non-customer-specific grades to automotive customers (in terms of volume). In other words, the non-customer-specific grades that automotive customers purchase and that are also sold to a significant extent to other industries represent only [0-5]% of automotive customers’ purchases (in terms of volume) from Tata of products with defined non-customer specific grades (roughly only […]).

(155) Based on the same data and analysis for ThyssenKrupp, the Commission finds that [60-70]% of the volumes sold by ThyssenKrupp to automotive customers concern customer-specific grades. As for Tata, other customer groups do not genereally purchase customer-specific grades. The only other customer categories that purchase significant volumes of customer-specific grades are Cold-rolling ([…]), which purchase minimal volumes in absolute terms, and Trading/SSC ([…]). Neither of them is an end-user customer group and the group Trading/SSCs presumably largely resells to the automotive industry, for the same reasons as explained above for Tata. Finally, ThyssenKrupp’s customer group Other purchases almost exclusively customer-specific grades, but this also represents a minor group purchasing only […] (less than [0-5]% of ThyssenKrupp’s total HDG sales in terms of volume).

(156) Focusing on ThyssenKrupp’s sales of non-customer-specific grades to automotive customers, the Commission finds that, excluding internal sales and sales to Trading/SSCs, non-customer-specific grades that are predominantly sold to automotive customers (meaning that more than 90% by volume of steel of those grades are sold to automotive customers) represent approximately [60-70]% of ThyssenKrupp’s sales of non-customer-specific grades to automotive customers (in terms of volume). In other words, the non-customer-specific grades that automotive customers purchase and that are also sold to a significant extent to other industries only represent […] of automotive customers’ purchases (in terms of volume) from ThyssenKrupp of products with defined non-customer-specific grades (roughly only […]).

(157) The overlap between sales to automotive and non-automotive customers could appear important when considering the more aggregate steel-type breakdown suggested by the Parties in their reply to Question 9 of RFI 22 (between Mild, HSLA, BHS, DP_600-- and AHSS_780), each of which contain several different steel grades. However, when considering the more granular level of actual steel grades – which is how customers place orders – the overlaps between automotive and non-automotive customers are negligible, as described above.

(158) More generally, it is natural that if ‘types’ of HDG are defined sufficiently broadly, there will always be sales of the same type of HDG to different customer groups. The analysis above shows that if looking at the relevant category of product ‘grade’, which the Parties also use internally in the regular course of business, the vast majority of sales to the automotive industry are of grades not sold in significant volumes to non-automotive customers. In other words, the types of steel sold to automotive customers and non-automotive customers might present similarities at an aggregate level (namely of the same broad category of steel) but they are significantly different at the more granular level at which purchases are made (namely different grades).

(159) Moreover, the Commission infers from the Notifying Parties’ submission that, even on the aggregate level of analysis suggested by the Parties, […] of the types of HDG they sell to the automotive industry are only or predominantly sold to the automotive industry and not to other customers. This seems to include both AHSS and general automotive steel. In any case, the Commission finds that the fact that some broadly defined steel types are sold for multiple applications is not in contradiction to the finding that automotive customers have specific requirements for the steel they demand.

(160) The Commission thus concludes that HDG for automotive applications caters for specific technical characteristics required by automotive customers, distinguishing it from HDG supplied to other industries. The results of the market investigation also suggest that the automotive industry overall has specific requirements for the steel it demands compared to other applications and that there are at least some steel grades and types that are solely or predominantly used in the automotive industry.

(161) First, a number of customers explained in the market investigation that the automotive industry has specific requirements for the steel it purchases. An automotive customer notes in this respect that ‘there are special grades used by automotive sector, including AHSS and UHSS, PHS’94 while another submits that ‘[t]he steel used in the automotive industry is different from the steel applied in the construction industry. Indeed, car manufacturers need high strength steel grades, especially to make the stamped parts, with particular elongation properties. Moreover, surface, size and tolerance requirements are different.’95 A third customer concurs: ‘Finally, the potential overcapacity globally or in the EU for steel is not applicable to automotive grades, which are to that extent different than construction grades. [The respondent] is not able to use non-automotive grades as they are fundamentally different to the grades used in cars.’96, 97

(162) Second, competitors suggested that there are differences between automotive and non-automotive HDG in particular when it comes to HDG used in exposed car parts. In this area, automotive applications appear to require particular surface quality and wider coils than non-automotive applications. A competitor notes that ‘HDG for exposed automotive parts need some specific properties such as high strength along with high ductility and formability. That is why steels with specific compound structure are used for these applications (dual phase, multiphase grades, TRIP- and IF steels). Higher requirements for surface quality and higher width for some exposed parts.’ Another competitor makes similar observations: ‘[T]he surface quality is most demanding qualitative requirement of the Auto [sic] industry as it directly affects further paint-coating of the exposed auto - - exposed Auto [sic] parts require an extended capability in terms of steel coil width (up to 1850 mm) as exposed Auto [sic] panels are made from a single wide steel sheet (no welding) whilst manufacturers in non-Auto [sic] industries, for instance Construction [sic], purchase largely panels, profiles or flat sheets and slit strips made from standard coils 1250/1500 mm’.98

(163) Third, when it comes to HDG for non-exposed applications, some competitors suggest that there is interchangeability with non-automotive application HDG but that some grades are automotive-specific even in this area. A competitor notes in this respect that ‘HDG suitable for non-exposed automotive parts can also be used as for non-automotive uses and vice versa, even if some grades are specific to automotive applications’.99

(164) Fourth, another competitor explains that some grades sold for other applications cannot be used for automotive applications: ‘[s]ome HDG steel products EN 10346 (DX51D-DX54D can be used for non-exposed automotive parts as well as for construction applications - - [s]tructural grades by this standard (S220GD-S550GD) are not suitable for automotive elements production because of their low ductility and formability’.100

(165) Fifth, the results of the market investigation suggest that the automotive industry in general has tighter quality and tolerance requirements compared to other customers.101 In line with this, a clear majority of flat carbon steel manufacturers responding indicated that automotive customers require stricter tolerances compared to other customers, including both when they purchase high-end and more conventional grades.102 For example, one automotive customer explains that ‘[e]ven commodity steel grades like a CR240LA GI50/50 or a mild, deep drawing grade CR3 have to fulfill tighter specifications than for industrial use, e.g. surface roughness is higher, low oil distribution. The grade decision depends on the functional requirements of the part itself.’103 Similarly, a customer submits that ‘automotive tolerance requirements are the highest’104 while another customer explains that ‘[t]he automotive industry requires steel of - - superior quality, if compared to that used in more general applications such as the construction of buildings’.105 Another customer explains in more detail that ‘all steel used in the car is considered being high end steel . This in terms of formability, high strength mechanical properties, surface finish , corrosion protection and thickness tolerances.’ 106

(166) Moreover, a clear majority of respondents agreed that ‘Commodity steel could not be used instead of high-end steel for any applications’ and most of the remaining respondents found that ‘Commodity steel could be used instead of high-end steel only for very few applications’.107

(167) Sixth, as recognised in the internal documents of the Notifying Parties, the product mix demanded by the automotive industry is changing, largely due to stricter environmental requirements on emissions and by extension on the total weight of a car. Based on the Parties’ internal documents, this results in advanced high-strength steels and ultra high-strength steels displacing conventional mild steels and high- strength steels, further emphasising the difference between HDG steel used in the automotive industry compared to that used in other industries.108