Commission, February 27, 2020, No M.9408

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

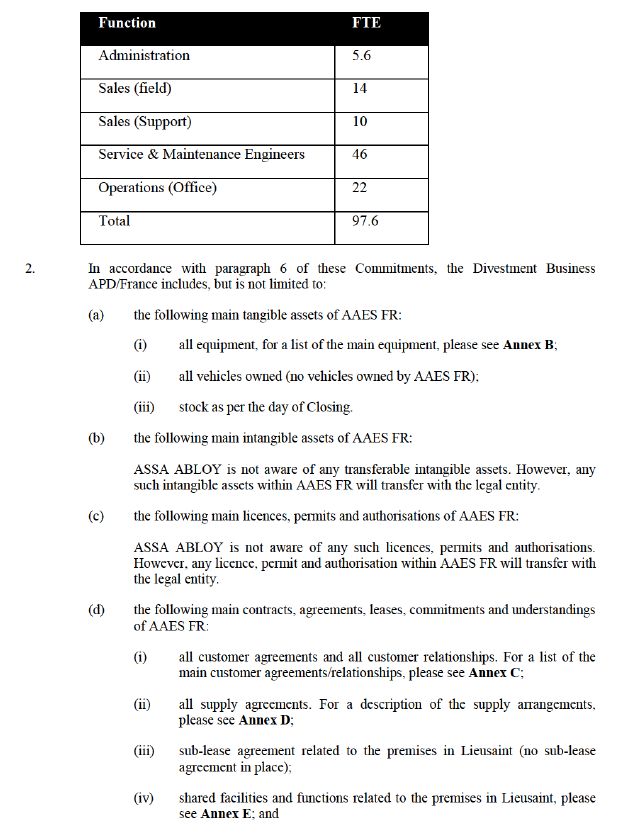

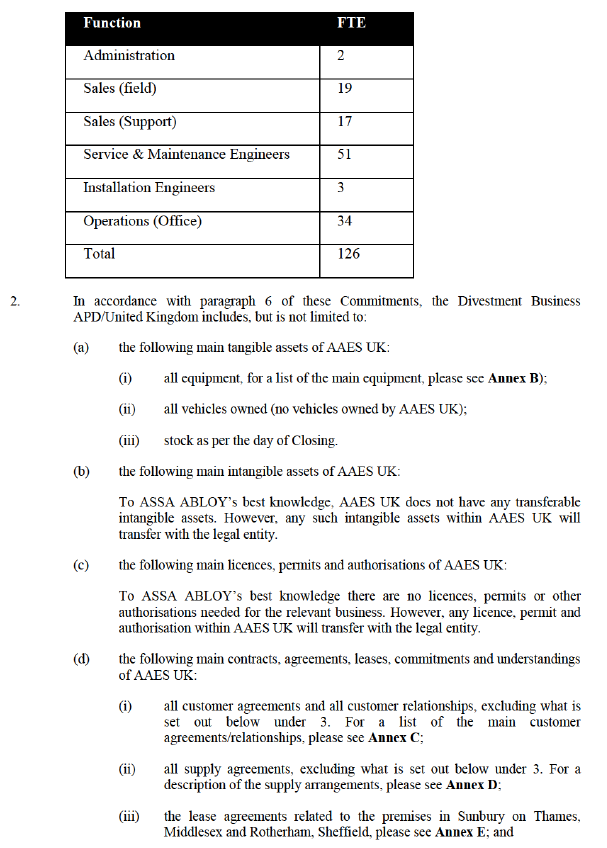

Decision

ASSA ABLOY / AGTA RECORD

Dear Sir/Madam,

Subject: Case M.9408 – Assa Abloy/Agta Record

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) in conjunction with Article 6(2) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2

(1) On 9 January 2020, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (the ‘Merger Regulation’) by which Assa Abloy AB (publ) (Sweden, ‘Assa Abloy’), acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of the whole of agta record ag (Switzerland, ‘Agta Record’). The concentration is accomplished by way of purchase of shares (the ‘Transaction’).3 Assa Abloy is hereinafter designated as the ‘Notifying Party’. Assa Abloy and Agta Record are hereinafter collectively referred to as the ‘Parties’.

1. THE PARTIES AND THE OPERATION

(2) Assa Abloy is a group headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden, active across a broad range of access solutions, including automatic pedestrian doors, automatic industrial doors, locks, sensors, as well as access control systems and related components.

(3) Agta Record is a group headquartered in Fehraltorf, Switzerland, focusing on the manufacture, supply and servicing of automatic pedestrian doors, with limited activities in industrial doors.

(4) Assa Abloy currently owns a non-controlling 38.75% interest in Agta Record.4

2. THE TRANSACTION

(5) The Transaction involves the acquisition of sole control by Assa Abloy over Agta Record. On 6 March 2019, the Parties entered into a share purchase agreement for the sale and transfer of the controlling 53.75% interest in Agta Record currently owned by Agta Record Finance SAS. After closing, Assa Abloy will own approximately 92.5% of Agta Record’s share capital and voting rights.5 Upon completion of the Transaction, Assa Abloy is committed to launch a public tender offer for the remaining outstanding shares in Agta Record.

(6) The Transaction therefore constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

3. UNION DIMENSION

(7) Assa Abloy and Agta Record have a combined aggregate worldwide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (Assa Abloy: EUR 8 412.7 million, Agta Record: EUR 375.4 million). Each of them has a Union-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Assa Abloy: [Assa Abloy’s Union-wide turnover] million, Agta Record: EUR [Agta Record’s Union-wide turnover] million), but they do not achieve more than two-thirds of their aggregate Union-wide turnover within one and the same Member State. The Transaction therefore has a Union dimension pursuant to Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. INTRODUCTION TO THE ENTRANCE AUTOMATION INDUSTRY

(8) As a matter of general introduction, this section summarises the basic features of the entrance automation industry and introduces terms and concepts used in the remainder of this decision.

(9) Entrance automation systems are motorised products used in and around entrances, which allow the opening and closing of, e.g., doors and gates. These systems equip commercial, industrial and residential buildings, as well as other types of public spaces.

4.1. Relevant entrance automation systems

(10) For the purpose of assessing the Transaction, two types of automation systems are relevant, namely automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors, as well as after-sales services and spare parts for each of these door types.6

4.1.1. Automatic pedestrian doors

(11) Automatic pedestrian doors are doors used by pedestrians that open and close automatically after being triggered by a motion sensor, a push plate or an access control device. Automatic pedestrian doors may be used for both interior and exterior applications.

(12) Automatic pedestrian door solutions may involve the sale of (i) standalone operators; or (ii) complete door sets.

(13) An operator is a mounted device that performs the function of opening and closing an automatic pedestrian door. Operators usually consist of: (i) operating control components (e.g. control boards and sensors); (ii) opening and closing hardware (e.g. power supply and gear boxes); (iii) a motor; (iv) safety devices and actuators (e.g. safety switches and push buttons); and (v) software.

(14) Original equipment manufacturers (‘OEMs’) assemble separate parts into operators and fit them into aluminium casings. While this assembly process is generally manual, cutting aluminium for the casings and the painting and coating requires machinery.

(15) A complete automatic pedestrian door set generally consists of (i) an operator; (ii) one or several door leaves; and (iii) a door frame, tracks, carriage wheels, belts (for sliding doors) or an arm (for swing doors). Automatic pedestrian doors may come with variations in, e.g., the size, colour and thickness of the glass.

(16) Automatic pedestrian doors include several door types, mainly swing, sliding and revolving doors, but also folding and other types of specialty doors:

(a) Automatic swing doors (‘swing doors’) open by rotating around an axis. Swing doors are more space efficient than sliding or revolving doors in terms of the size of wall/frame space needed, but less energy-efficient. Swing doors are more often used as interior doors. Most non-automated doors may be converted into an automatic swing door with the installation of an operator and an arm. Therefore, many sales of swing doors consist in the sale of the operator and arm only. There is also an existing overall trend towards greater adoption of low-energy swing door operators as opposed to full-energy operators.7 Low-energy swing operators allow the door to open at lower speeds than full-energy operators and remain open for at least five seconds.

(b) Automatic sliding doors (‘sliding doors’) open laterally by sliding. They can consist of single or bi-parting openings. Sliding doors typically include glass leaves and are primarily used for the entrance of buildings. Globally, the sliding door segment is forecast to grow the fastest between 2016 and 2021, as these are the most popular product type and account for the biggest proportion of all automatic doors installed.8

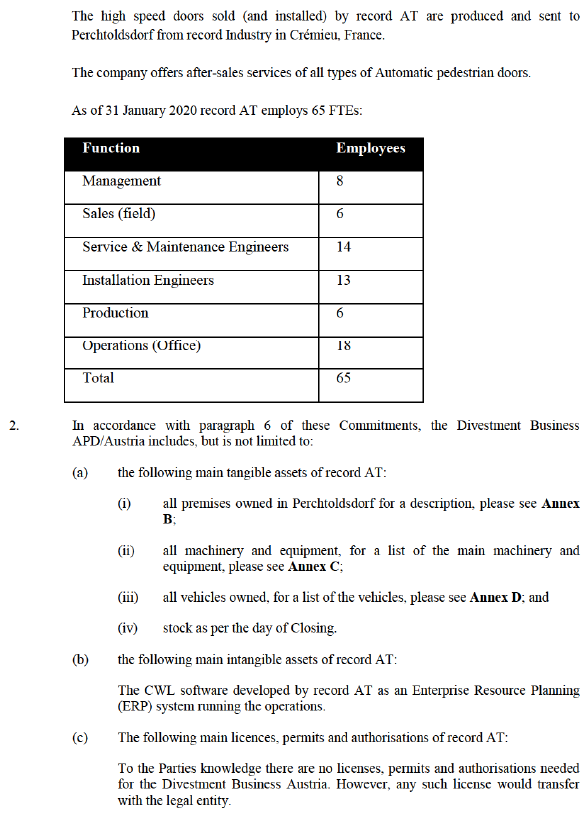

(c) Automatic revolving doors (‘revolving doors’) rotate to let pedestrians in and out. Revolving doors usually have two, three or four leaves. These doors are the most expensive and complex option, but also the most energy-efficient. They are almost exclusively found at the entrance of buildings.

(d) Automatic folding doors (‘folding doors’) move horizontally and are intended for premises with limited space around the door opening.

(e) Additionally, there is a heterogeneous group comprising different types of specialty automatic doors displaying certain special properties, such as sealing capabilities (hermetic doors), fire resistance (fire doors) or bullet or blast resistance (security doors).

(17) Even though many of these products may be similar throughout the EEA, there are country-specific requirements in terms of national safety norms and regulation that result in certain product differences across countries. For instance, some countries may impose specific requirements on doors used in escape routes9 or additional certificates or declarations.10 While the most important standard in the EU applicable to automatic doors is EN 16005, some countries have defined their own national standards.11

(18) Figure 1 below illustrates automatic swing, sliding, revolving and hermetic doors.

4.1.2. Industrial doors

(19) Automatic industrial doors (‘industrial doors’) are generally designed to facilitate the flow of goods or vehicles in industrial or commercial buildings. They may be used for either interior or exterior applications.

(20) Industrial doors include different types of automatic doors, such as (i) high-speed doors; (ii) overhead sectional doors; (iii) industrial folding doors; and (iv) docking doors and stations.

(a) High-speed doors have a roll-up system with high opening speed and allow people and goods to pass through without disrupting the flow.

(b) Overhead sectional doors are made of sections that slide up and disappear up under the roof when opened in order to save as much space as possible around the door opening.

(c) Industrial folding doors move horizontally and are intended for premises with limited space around the door opening and where the roof space is not sufficient to allow for a sectional door.

(d) Docking doors and stations are designed for locations with intense traffic flow of heavy vehicles. Docking stations enable loading and unloading from trucks and allow for adjusting the loading bay to facilitate loading from truck beds of different levels.

(21) Figure 2 below illustrates these different types of industrial doors.

4.1.3. After-sales services

(22) After-sales services include the maintenance, repair, servicing, overhaul and upgrades of automatic doors in operation. After-sales services involve both regular maintenance (typically performed on the basis of maintenance contracts12), ad-hoc repairs (also known as one-off transactions, call-outs or service calls) and retro-fits or overhaul (whereby the provider supplies additional features to an existing installation and/or upgrade it to higher or later specification).13

(23) After-sales services can be provided both by the supplier of the door (either the OEM or the non-integrated supplier) or by a third party. They are undertaken with the assistance of service tools and may require spare parts. Service tools are software-based solutions that can facilitate configuration and troubleshooting. Spare parts can be generic or brand specific. Brand specific spare parts typically need to be sourced directly or indirectly from the OEM of the door to be repaired or maintained. This is particularly true for some parts such as the drive motor and the electronic control of the operator.

4.1.4. Spare parts

(24) Spare parts include components used when assembling automatic doors or even sub-assemblies of such components.

(25) The majority of the supply of spare parts occurs within the context of the provision of after-sales services to replace faulty or depleted parts, although spare parts may also be sold to non-integrated suppliers for them to assemble automatic doors.

(26) There are two types of spare parts: generic spare parts and brand-specific spare parts.

(a) Generic spare parts can be replaced by any sub-component with the same function, regardless of brand or certification. These include, e.g., springs, rollers, hydraulics, wheels, plastics, belts, cables and metal plates/bends.

(b) Brand-specific spare parts are specific to products of a specific brand, which must be sourced from the OEM or its dealer network (or from entities that resell brand-specific spare parts). These include, e.g., the motor, the drive unit or the control board of the door in question, but also mechanical spare parts such as carriages, casings, frames and profiles, as well as certain pieces of electronics such as batteries.14

4.2. Value and supply chain of automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors

(27) The value chain of automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors typically consists in the design of sub-systems, manufacture/procurement of components, assembly, sale/wholesale and installation of operators or complete door sets, and after-sales services.

(28) This value chain may be more or less centralised depending on the company. Some companies manufacture, assemble and ship automatic pedestrian doors in/from the same premises, whereas others manufacture in certain premises and ship the manufactured products to a different plant for the final assembly and distribution.

(29) The supply chain in the entrance automation systems industry mainly comprises two types of suppliers: OEMs (or ‘integrated suppliers’) and independent distributors/installers (or ‘non-integrated suppliers’).

(30) OEMs manufacture and supply operators and complete door sets to both end- customers and non-integrated suppliers. OEMs also install themselves operators and complete door sets at the premises of end-customers and provide after-sales services.

(31) Non-integrated suppliers do not have their own proprietary designs and supply chain. They source door parts (e.g. operators, door frames and glass leaves), which they then assemble, sell and install as a complete door set at the premises of end- customers. Operators sold to non-integrated suppliers generally carry the brand of the manufacturing OEM.15

(32) On the demand side, there are several types of end-customers of entrance automation systems, such as small and medium-sized business owners, key account customers, building contractors, façade companies or facility management companies.

(33) End-customers may belong to different end-user groups, such as healthcare (e.g. hospitals and elderly care), retail (e.g., clothes stores, pharmacies or supermarkets), private sector (e.g., office buildings and banks), public sector (e.g., universities, libraries and governmental buildings), hospitality (e.g., hotels) or transport (e.g., airports).

(34) OEMs and non-integrated suppliers also sell operators and complete door sets to customers who are not the end-users (intermediary customers). These intermediary customers tend to be responsible for the construction or refurbishment of a building on behalf of an end-user (e.g., contractors or façade companies).

4.3. Procurement process

(35) The procurement process might vary depending on whether the end-customer is a public or a private entity. Public entities often organise tenders according to public procurement rules, whereas private entities may organise regular tenders or simply request quotes from different suppliers. Certain large/key customers also enter into framework agreements with suppliers, whereas smaller customers rather resort to one-off sales to source a single (or a few) door(s).16

(36) Architects are not customers but have an important role in the competitive process, particularly in sales to contractors and façade companies. Architects may influence the choice of automatic doors used in a particular building project by, e.g., specifying certain dimensions for a door opening that suits a certain supplier better than other potential suppliers.17 For this reason, many OEMs market their products to architects with the objective of inducing them to include, in the specifications of a building, technical requirements or references to a particular supplier’s product, or to mention a particular brand or simply dimension door openings in a way that suits them better than other potential OEMs.

(37) The importance of architects in the procurement process was echoed by respondents to the market investigation and also mentioned by Assa Abloy in recent earning calls with investors, as follows: ‘[f]or new projects, bigger projects, we have a large specification team working together with architects, working together with contractors, making sure that the spec in the right solution, an ASSA ABLOY solution in their projects. Once it’s spec-ed in, then it’s also much easier afterwards to sell your products and your solutions’.18 The market feedback is consistent on this point. A majority of respondents who expressed an opinion consider that architects play either an ‘important’ or a ‘very important’ role.19 A competing OEM expressed that planners and architects usually specify a brand and that their influence is very high.20

4.4. Other products vertically or closely related to entrance automation systems

(38) Access control systems and components, locking devices and sensors are products that are closely related to entrance automation systems.

4.4.1. Access control systems

(39) Access control systems manage the access credentials into and/or within buildings and enable communication between access control components (e.g., cards and card readers).

4.4.2. Locks

(40) Locks secure access to doors of, e.g., buildings, vehicles, furniture or cabinets. A traditional lock may be either mechanical (where all parts of the system are mechanical) or electromechanical (where are least one part is electronic).

(41) Mechanical locks typically consist of cylinders, lock cases and a strike plate. Mechanical locks are either single-point locks or multi-point locks (which have more than one locking point typically activated by a cylinder). The cylinder is fitted into a lock case (a metal case around the actual lock cylinder) which is placed in the door or on the side of the door with the strike plate.

(42) Electromechanical locks operate by means of electric current.

4.4.3. Electric strikes

(43) Electric strikes are electromechanical locking devices, activated by an electric current and releasing the latch bolt of the lock case by electrically retracting a small ramped surface (‘strike’). This allows for opening of the door with a lock in a closed position (without operating the lock itself). The strike subsequently returns to its original position, relocking the door when closed.

4.4.4. Sensors

(44) Sensors are devices that detect the presence of pedestrians and vehicles and consequently order the door to open automatically. Sensors can work for one or multiple types of automatic doors. Sensors can also be used for elevators and escalators.

4.5. Introduction to the Parties’ activities

4.5.1. Overlapping activities of the Parties

(45) The Parties are both OEMs of automatic doors, including automatic pedestrian doors (swing, sliding and revolving) and industrial doors (including high-speed doors). The Parties have a fully integrated supply chain ranging from the design of operators to the on-site installation of complete door sets (including operators, door leaves and other components), and the provision of after-sales services.

(46) Both companies sell directly to end-customers (e.g., building contractors, façade companies, retail chains or hospitals), but also to non-integrated suppliers.

(47) In the EEA, Assa Abloy sells automatic pedestrian doors to end-customers under the Assa Abloy (formerly, until 2018, Besam) brand and to non-integrated suppliers under the Entrematic and Ditec brands.21 Agta Record sells swing and sliding doors under the record brand, and revolving doors under the BLASI brand.22 In addition, it sells hermetic doors under the KOS brand. In the supply of industrial doors, Assa Abloy uses the brand Assa Abloy, as well as various local brands, for sales to end-customers and brands such as Dynaco, Ditec, Nergeco and Normstahl, combined with Entrematic, for sales to non-integrated suppliers.23 Agta Record supplies limited volumes of industrial doors under the record brand.24

(48) Both Assa Abloy and Agta Record provide after-sales services (which may comprise the maintenance, repair or upgrade of automatic doors), an activity that contributes a sizeable share of their overall revenues and profits ([Assa Abloy’s sales]).25 In addition to offering after-sales services themselves, the Parties also supply spare parts required to provide after-sales services on their doors to third- party service providers.26

4.5.2. Non-overlapping activities of the Parties

(49) In addition to its activities related to automatic doors, Assa Abloy provides access control systems, locking devices and sensors.

(50) With regard to access control systems,27 Assa Abloy manufactures and sells both access control systems (software) and access control components (hardware). The Notifying Party submits that ‘[t]hrough its Global Technologies division, Assa Abloy manufactures and sells components to identity solutions and electronic access control systems (such as electronic systems to open doors and gates with identity cards, pin codes and card readers)’28, while ‘ASSA ABLOY Opening Solutions EMEA provides both electronic access control systems (via Aptus, Accentra, Abloy OS, Scala, SMARTair and Seawing) and electronic access control system components (via e.g. its wholesaler business)’.29 Agta Record does not manufacture access control systems or components; at customers’ requests, it occasionally sources from third parties electronic access control components to operate its automatic doors.30

(51) With regard to locking devices, Assa Abloy manufactures and sells locks via its division ASSA ABLOY Opening Solutions.31 Assa Abloy’s lock brands include ABLOY, ASSA ABLOY, IKON, Mul-T-Lock, TESA, UNION, Yale and Vachette. Agta Record is not active in the manufacturing of locks.32 At customers’ requests, it occasionally sources from third parties and resells locks as integrated part of its automatic doors.

(52) Assa Abloy manufactures electric strikes through ASSA ABLOY Sicherheitstechnik GmbH (Germany) and ASSA ABLOY Czech & Slovakia s.r.o. (Czechia).33 These electric strikes are sold in the EEA through the Opening Solutions EMEA division, predominantly under effeff and FAB brands. Agta Record is not active in the manufacturing of electric strikes.34 In rare cases an electric strike is delivered as part of a door system, Agta Record sources it from a third party.

(53) Finally, with regard to sensors, Assa Abloy’s subsidiary Cedes manufactures and supplies sensors to, amongst others, OEMs of automatic doors (including Agta Record).35 In contrast, Agta Record does not sell sensors to third parties; it manufactures sensors based on a closed interface for exclusive use in some of its own automatic door models.

4.6. Entrance automation systems OEMs and non-integrated suppliers in the EEA

(54) Entrance automation systems OEMs active in the EEA have different geographical footprints. Some OEMs are present EEA-wide, whereas others have activities only in certain Member States. The Parties offer the products and services described in Section 4.5 above across the EEA, while their competitors may only offer a range of products or be active only in parts of the EEA. Non-integrated suppliers are for the most part active only at national or local level.36

(55) In addition to the Parties, some of the main industry players are listed below:

(a) For automatic pedestrian doors, the main OEM suppliers include Dormakaba International Holding GmbH (‘Dormakaba’), Geze GmbH (‘Geze’), Gretsch- Unitas GmbH (‘GU Automatic’), Landert Group AG (‘Tormax’), FAAC S.p.A. (‘FAAC’), Gilgen Door Systems AG (‘Gilgen’), Royal Boon Edam International B.V. (‘Boon Edam’), Portalp SAS (‘Portalp’), Label S.p.A. (‘Label’) and Manusa Gest, S.L. (‘Manusa’).

(b) For industrial doors, the main OEM suppliers include Hörmann KG Verkaufsgesellschaft (‘Hörmann’), EFAFLEX Tor- und Sicherheitssysteme GmbH & Co. KG (‘Efaflex’), Ba2i Technologies SAS (‘Ba2i’), Manurégion SARL (‘Manurégion’), Safir SAS (‘Safir’), Portalp and Novoferm GmbH (‘Novoferm’).

(c) For after-sales services, important providers include Dormakaba, Geze, GU Automatic, Gilgen, Kone, Boon Edam, Tormax, Portalp, Thyssenkrupp, FAAC, as well as facility management companies.

(d) For access control systems and components, the main suppliers include Allegion, Dormakaba, Ikor, Hana, Season, Cominfo, Digitalist Finland, Westcomp, Victorsson Industrier and OEM Electronics.

(e) For locks, suppliers include Bricard, Dormakaba, Marques, Carl Fuhr, DOM- MCM, Ezcurra, Mottura Serrature di Sicurezza, jasa, Abson Industry or Carlisle Brass/Eurospec.

(f) For sensors, suppliers include BEA, Bircher Reglomat, Carlo Gavazzi, FRABA, Witt, Optex, Pepperl + Fuchs, SICK, Telco and Horton.

5. MARKET DEFINITION

(56) The main products relevant to the merger control assessment of the Transaction are automatic pedestrian doors, industrial doors, after-sales services, spare parts, access control systems and components, locking devices, and sensors.

(57) The supply of automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors is characterized by similar features, which are described in Section 5.1 below. In turn, Sections 5.2 and 5.3 include a specific analysis of the supply of automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors, respectively. The subsequent sections discuss after-sales services, spare parts, access control systems and components, locking devices and sensors.

5.1. General considerations on the market definition of automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors

5.1.1. Sales channels

5.1.1.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

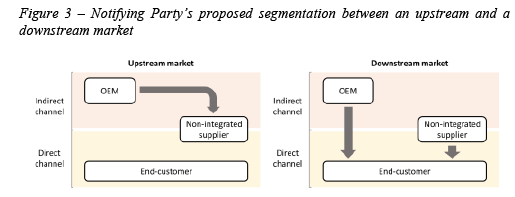

(58) The Notifying Party submits that two separate and vertically related product markets should be defined within automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors, depending on whether the supplier installs the door at the premises of the end- customer, namely (i) an upstream market for automatic door components sold by OEMs to non-integrated suppliers (only), which is referred to as the ‘indirect channel’ and where installation is not included; and (ii) a downstream market for automatic door solutions sold to end-customers (only) by OEMs and non-integrated suppliers, which is referred to as the ‘direct channel’ and where installation is included.37 Figure 3 below provides an overview of the Notifying Party’s proposed segmentation.

(59) In this regard, the Notifying Party submits that the upstream market (also referred to as the ‘indirect channel’) would consist in the supply of operators (and of complete door sets to a limited extent) by OEMs to non-integrated suppliers for resale and installation. In turn, the downstream market (also referred to as the ‘direct channel’) would comprise the supply to end-customers of complete automatic door sets and operators for the automation of existing doors, by both OEMs and non-integrated suppliers. According to the Notifying Party, downstream sales would usually include the installation and configuration of the automatic doors, as well as other on-site services.38

(60) The Notifying Party explains that indirect sales eventually translate into direct sales, as non-integrated suppliers supply end-customers with operators combined with door leaves and frames, in competition with the OEMs from which they procured the operators in the first place.

(61) The Notifying Party considers that the proposed segmentation is justified by differences in customer demand: in the direct channel a number of on-site services are supplied together with the automatic doors (e.g. taking exact measurements, discussing the specifications of the door), whereas in the indirect channel customers allegedly buy the products in bulk and order them for stocking purposes and eventually resale. In addition, the Notifying Party considers that supply side substitutability is limited across the two segments, as OEMs supplying end- customers downstream need a local presence, whereas non-integrated suppliers would need to develop their own automatic door operators (i.e., become OEMs) in order to enter the upstream segment.39

5.1.1.2. Commission’s assessment

(62) In Assa Abloy/Cardo, which related to a concentration between two OEM suppliers of industrial doors and related after-sales services,40 the Commission did not retain a distinction between an upstream and a downstream market, and the parties did not submit that it would be appropriate to do so at the time. In this precedent dating from 2011, while leaving the precise market definition open, the Commission based instead its competitive assessment on an overall market for industrial doors (and each of the different industrial doors types).

(63) When it cleared Assa Abloy’s acquisition of a non-controlling minority interest in Agta Record back in 2010, the United Kingdom’s Office of Fair Trading (‘OFT’) distinguished between the sale of operators, on the one hand, and the sale of complete automatic pedestrian door sets, on the other hand.41 The OFT did not distinguish between an upstream and a downstream market, but merely indicated that operators (i.e, ‘automatic door automation systems’) and complete door sets (i.e., ‘complete automatic pedestrian door sets’) ‘are sold in the UK through different sales channels to end users’.42

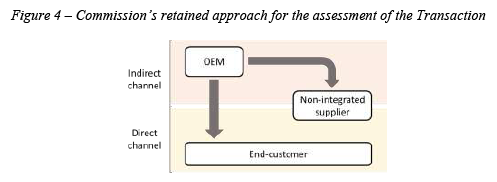

(64) In the present case, contrary to the Notifying Party’s arguments, the Commission takes the view that examining competition at OEM-level (i.e., sales by OEMs-only to both end-customers and non-integrated suppliers, thus combining OEM sales in the direct and indirect channels) is a more appropriate analytical framework to assess the impact of the Transaction on competition, for a number of reasons spelled out below. Figure 4 below provides an overview of the Commission’s approach for the assessment of the Transaction.

(65) At the outset, the Commission notes that the Transaction involves the combination of, and the resulting loss in competition between, two fully integrated OEMs supplying both end-customers and non-integrated suppliers with the same products by means of a dual distribution structure. However, the Notifying Party’s approach does not capture accurately the extent of the loss of competition between the Parties as two of the main OEMs active EEA-wide in the supply of automatic doors. In particular, the proposed definition of a downstream market encompassing sales to end-customers by both OEMs and non-integrated suppliers has the consequence of artificially diluting the extent of the Parties’ actual market position, which cannot be reflected either by assessing the proposed upstream market in isolation. The results of the market investigation support the appropriateness of the Commission’s assessment framework.

(66) First of all, a vast majority of competing OEMs and non-integrated suppliers who expressed an opinion on this point do not consider that there are material technical differences between the automatic doors, including operators or complete door sets, supplied to end-customers, on the one hand, and to non-integrated suppliers, on the other hand.43 Hence, there is a very high degree of substitutability between the products marketed to end-customers and to non-integrated suppliers.

(67) Secondly, a vast majority of respondents to the market investigation have indicated that non-integrated suppliers also source door leaves and complete door sets from OEMs, i.e., not only standalone operators.44 Moreover, a significant number of respondents submitted that, contrary to the Notifying Party’s argument, non- integrated suppliers also source products from OEMs on a project/on-demand basis, like end-customers do, and not only or even primarily for stocking and resale purposes.45 In this regard, a competitor submitted that ‘[t]he automatic door business is mainly project driven and specifications are strictly related to all the different openings present in each project (dimensions, type of flow, etc.)’.46 Conversely, as the Parties acknowledge, end-customers also procure operators only, such as swing operators to automate existing doors.47 Moreover, revolving doors are generally sold as complete door sets irrespective of the sales channel,48 and then primarily in the direct channel. These elements further reinforce the substitutability across sale channels, which extends to procurement patterns.

(68) Thirdly, non-integrated suppliers are inherently dependent on OEMs for the core – if not the whole – of the automatic door products that they supply. Moreover, according to a vast majority of competing OEMs and non-integrated suppliers, the brand of originating OEMs is generally affixed on the operators and the complete door sets procured by non-integrated suppliers for resale and installation.49 As a result, from the end-customer perspective, the products supplied by non-integrated suppliers clearly originate from and remain affiliated with OEMs, with potential consequences in terms of customer loyalty and cross-selling/sourcing, notably for after-sales services.50

(69) Fourthly, the market investigation has revealed that vertical integration gives OEMs a significant cost advantage compared to non-integrated suppliers. This is particularly apparent from the outcome of an analysis of the realised prices of Agta Record’s best-selling products to non-integrated suppliers in each of the United Kingdom, Germany and France, compared to the internal prices charged within Agta Record for the same products for supply in the same countries.51 That analysis revealed differences of up to [information about Agta Record’s margins and cost structure] to the benefit of Agta Record’s own local operations. Hence, this constitutes strong evidence that non-integrated suppliers are not able to exercise the same level of competitive constraints on OEMs than OEMs among themselves, notably as basic local operational costs (e.g., labour, operating assets) are largely equivalent irrespective of the supplier category.

(70) Fifthly, as explained in section 5.1.2, the outcome of the market investigation reveals that a core segment of demand, namely large end-customers and large projects, tend to favour direct procurement from OEMs rather than from non- integrated suppliers.52 A majority of end-customers that expressed an opinion in response to the market investigation also indicated that they source predominantly from OEMs.53 Generally, end-customers associate OEMs with specific preferences, including prices and technical expertise, which differ from the features associated with sourcing from non-integrated suppliers.54

(71) At the end, the direct and indirect channels constitute two alternative ways for OEMs such as the Parties to satisfy the demand of end-customers, and to maximise sales and output. The service component of direct sales is also inherent to dealings with end-customers, as in many industries. Hence, in the present case and in light of all available evidence, the Commission considers that it is not appropriate to consider separately hypothetical upstream and downstream markets within the supply of automatic pedestrian doors and of industrial doors, as advocated by the Notifying Party. The Commission will therefore conduct its competitive assessment based on an OEM-level approach, which includes sales by OEMs-only to both end-customers and non-integrated suppliers. In turn, the Commission will factor in its assessment the existence of different sale channels and the level of competitive constraints that non-integrated suppliers may still exercise on OEMs for sales to end-customers.

5.1.2.Segmentation by types of supplier and customer group

5.1.2.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(72) The Notifying Party submits that it would not be appropriate to further segment the market according to the type of supplier (between OEMs and non-integrated suppliers) or customer group (between smaller and larger customers).55

5.1.2.2. Commission’s assessment

(73) Section 5.1.1. explained that it was appropriate in the present case to define relevant markets at OEM level, i.e., as encompassing OEM sales to both non- integrated suppliers and end-customers. A different, though related, question pertains to whether it is appropriate to segment relevant product markets according to certain customer groups.

(74) In Assa Abloy/Agta Record, the OFT noted that ‘large customers’ requirements (such as nationwide coverage) may preclude local independents from supplying them because large national buyers prefer […] complete automatic door sets from established manufacturers’ and that ‘[b]id data [had] revealed that larger customers had switched mostly to competing integrated manufacturers’.56 The OFT did not ultimately retain a segmentation by customer group in view of bid data supplied by Assa Abloy, which would have showed that it had bid for a significant number of smaller contracts.57

(75) In the present case, a majority of competitors and non-integrated suppliers submitted that certain final customers (such as large customers operating multiple sites) are more likely to procure automatic doors from OEMs rather than from non- integrated suppliers.58 A number of respondents indicated that this would be in particular the case for categories of customers such as, among others, supermarkets, large distribution and Horeca chains, airports, hospitals, facility management companies or key account customers.59

(76) Moreover, a majority of competitors and non-integrated suppliers submitted that for large projects, final customers are more likely to source automatic doors from OEMs rather than from non-integrated suppliers.60 While responses on this point were mixed among customers, some indicated that ‘for large projects it is important to source via OEMs in order to have one responsible supplier for the whole project. If doors are installed at various sites within a certain period of time based on one sourcing project it is a large project’.61

(77) A number of competitors also submitted that final customers typically ascribe value to procuring automatic pedestrian doors from OEMs rather than from non- integrated suppliers given their ‘direct contact […] on technical problems and warranty’, their ‘better price and service’ or them being a ‘[s]ingle source of supply, consistency of product, reduction in future maintenance/service requirements’.62

(78) The Parties’ internal documents further reflect the importance that they ascribe to large customers and large projects. Some of the Parties’ ordinary course of business documents indicate that Agta Record ‘[Agta Record’s sales policy and strategy]’63, while Assa Abloy has ‘[Assa Abloy’s sales policy and strategy]’64.

(79) However, for the purpose of carrying out a meaningful competitive assessment in the present case, it appears neither feasible nor warranted to define separate markets for ‘large customers’ and/or ‘large projects’ given the inherent heterogeneity of these categories. Moreover, the Parties have submitted anecdotal evidence that OEMs do also compete for ‘small’ customers and ‘small’ projects.65 Thus, the Commission considers appropriate in this case to exclude the definition of separate markets per customer group and to take customer preferences into account, inasmuch as they can be reasonably approximated based on the outcome of the market investigation, in the competitive assessment, notably to assess competitive constraints.

(80) At the end, the above findings confirm that non-integrated suppliers do not exercise competitive constraints on OEMs to the same extent as other OEMs, especially for the sizeable share of demand accounted for by large customers and large projects. This strongly indicates that there is closer competition amongst OEMs even for sales to end-customers, as further developed in Section 7.2.2.3 below.

(81) For the purpose of the decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission therefore considers that while a segmentation by end-customer type is neither feasible nor warranted, the sale of automatic doors to end-customers is differentiated inasmuch OEMs appear better placed to address a significant segment of demand than non-integrated suppliers. Hence, since the Parties are both OEMs and while the differentiation is by nature not absolute, the competitive assessment will consider sales by OEMs to end-customers, as a relevant metrics. OEM sales to non-integrated suppliers, separately from sales to end-customers, constitute assuredly another relevant metric for the competitive assessment in view of the common and identifiable characteristics of that other segment of demand.

5.1.3.Segmentation by end-user segment

5.1.3.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(82) The Notifying Party submits that it would not be appropriate to further segment the market according to end-customer segments (into, e.g., the healthcare, hospitality, private sector, public sector, retail and transport segments), given that (i) operators are the same and are not better suited for some end-user segments; (ii) the same company may supply projects irrespective of the end-user segment; (iii) the Parties do not have separate sales and installation processes per end-user segment; and (iv) the Parties often do not sell directly to end-user segments, but to intermediate customers (such as building contractors or façade companies).66

5.1.3.2. Commission’s assessment

(83) A majority of respondents expressing an opinion on this point in the market investigation submitted that it is not necessary to consider further segmentations based on the specific requirements of different user groups (e.g., residential, corporate, retail, hospitals, hotels and restaurants).67 However, some respondents indicated that the healthcare sector may have different technical needs for some applications, such as ‘e.g. doors for operating rooms’.68

(84) In light of the Notifying Party’s arguments and the results of the market investigation, the Commission takes the view that the Parties’ automatic doors do not generally appear to address the needs of distinct end-user segments. As regards the need of automatic doors for operating rooms by the healthcare sector, the Commission notes that this distinct demand is captured by defining a separate product market for hermetic and semi-hermetic doors in Section 5.2.1 below.

(85) For the purpose of the decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers that it is not necessary to further segment the product markets for automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors according to end- customer segments.

5.2. Automatic pedestrian doors

5.2.1. Product market definition

5.2.1.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(86) The Notifying Party submits that there are separate relevant markets for each of swing, sliding and revolving doors.69 This is because substitutability on the demand and supply side is limited in practice by the design of the doorway, applications, energy efficiency requirements and price levels.70

(87) The Notifying Party submits that each of the three automatic pedestrian door segments (i.e. swing, sliding and revolving) should not be further segmented between (i) variants of doors (e.g. differing in colour, size, type of glass, power of the motor, etc.)71; (ii) fire doors72; or (iii) hermetic doors73.

(88) The Notifying Party proposes to leave open the exact product market definition of automatic pedestrian folding doors, given the small size of the segment and the lack of a substantial horizontal overlap between the Parties.74

5.2.1.2. Commission’s assessment

(89) The Commission has not previously assessed the product market definition of automatic pedestrian doors. In its Assa Abloy/Agta Record decision, the OFT took account of indications that there would be separate markets for each of swing, sliding and revolving doors.75 In Assa Abloy/Cardo, the Commission noted that the market investigation had largely confirmed a distinction between automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors.76

(90) A majority of respondents having expressed an opinion on this point in the market investigation submitted that automatic pedestrian doors constitute a product market separate from industrial doors due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics and prices.77

(91) Moreover, a majority of competitors and end-customers submitted that, from a demand-side perspective, each of swing, sliding and revolving doors constitute separate product markets due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of product characteristics and prices.78 In this regard, a competitor pointed out that the choice between these types of doors ‘is basically due to the lateral space that you have to accom[m]odate the leaf when the automatic door opens’.79 While a majority of non-integrated suppliers submitted that there could be some substitutability between swing, sliding and revolving doors from a demand-side perspective80, a vast majority of them – together with a majority of competitors – submitted that the assembly of the various types of automatic pedestrian doors entail significantly different technical features and costs.81 In this regard, some competitors and non-integrated suppliers indicated that, from a supply-side perspective, these three types of automatic pedestrian doors rely on ‘[d]ifferent operators, different mechanism [and] different motors’.82

(92) A majority of competitors and non-integrated suppliers submitted that it is not appropriate to further segment the swing, sliding and revolving door markets based on different product variants, such as the number of leaves, materials or size.83 Similarly, a majority of respondents submitted that it is not appropriate to further segment the swing, sliding and revolving door markets based on whether they are equipped with low- or full-energy operators.84

(93) The Commission moreover notes that hermetic and semi-hermetic doors offer sealing capabilities and are typically used in operating theatres and other areas requiring an air-tight environment without bacteria and dust flow (such as in the pharmaceutical and the food industry). Hermetic doors are certified under one of the air permeability standards EN12207 and, more exceptionally, ANSI/UL 1784, whereas semi-hermetic doors offer some sealing capabilities without being certified. From a demand-side perspective, a majority of respondents to the market investigation submitted that (i) hermetic and semi-hermetic doors would constitute a market separate from other types of automatic pedestrian doors due to limited substitutability for customers in terms of, e.g., product characteristics and prices;85 and (ii) hermetic and semi-hermetic automatic doors would not be mutually interchangeable for the same or comparable situations.86 From a supply-side perspective, a majority of competitors and non-integrated suppliers submitted that the production or assembly of hermetic and semi-hermetic doors entail significantly different technical features and costs.87 Similarly, a vast majority of respondents submitted that automatic fire doors constitute a separate product market due to a limited demand-side substitutability.88

(94) For the purposes of this decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers that, due to limited demand and supply-side substitutability, (i) automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors do not belong to the same product market; (ii) each of swing, sliding and revolving automatic pedestrian doors constitute separate markets; and (iii) each of hermetic and semi-hermetic automatic doors constitute separate markets. The Commission does not consider appropriate to further segment these markets according to (i) different product variants (such as leaves, materials or size); or (ii) whether the automatic pedestrian doors are equipped with low- or full-energy operators. Since the Transaction does not give rise to any affected market for automatic fire doors, it can be left open whether the supply of automatic fire doors constitutes a separate product market from other types of automatic pedestrian doors.89

5.2.2. Geographic market definition

5.2.2.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(95) In relation to the geographic market definition, the Parties submit that (i) the indirect channel is EEA-wide in scope because customers across the EEA purchase the same products and OEMs do not need a local presence90; and (ii) the direct channel is national in scope because suppliers require a local sales force with local language proficiency and knowledge to operate in a given country, as well as technicians to provide installation and after-sales services.91

5.2.2.2. Commission’s assessment

(96) The Commission has not previously assessed the geographic market definition of automatic pedestrian doors specifically.92 In its Assa Abloy/Agta Record decision, the OFT assessed the transaction at a national level (both for the supply of operators and of complete door sets), as the Parties’ shares in the market on a national level (for the United Kingdom, in this case) were materially higher than their EEA-wide shares.93

(97) The outcome of the market investigation supports defining national markets for automatic pedestrian doors. Respondents having expressed an opinion on this point in the market investigation submitted that the supply of each of swing, sliding and revolving (including those with hermetic or fire-resistant features) automatic pedestrian doors to both end-customers and non-integrated suppliers is national in

scope.94 This is consistent with a number of industry features pointing to national markets, including different safety requirements across Member States affecting the technical features of (certain) automatic pedestrian doors,95 varying preferences across countries between notably swing and sliding doors,96 and significant price differences observable across countries.97

(98) With respect to sales in the indirect channel, in particular, a majority of non- integrated suppliers submitted that the technical specificities and the price of operators and complete door sets procured from OEMs vary to a material extent depending on the country of distribution.98 Moreover, a vast majority of non- integrated suppliers are purely national players.99

(99) Moreover, the Parties monitor closely in their ordinary course of business internal documents the national competitive dynamics of the indirect channel. In this regard, the Parties’ performance in the indirect channel appear to vary greatly across Member States. Assa Abloy considered the Nordics [information about Assa Abloy’s business strategy] of the Entrematic brand and Ditec to be ‘[information about Assa Abloy’s business strategy] [i]n France’.100

(100) Having a local presence at the level of each national market for the indirect channel also appears to be important in the industry. By way of example, an internal document from Assa Abloy considered that, while the Entrematic sales performance was [information about Assa Abloy’s business strategy] in the Nordics, it was [information about Assa Abloy’s business strategy] in the United Kingdom, given that ‘the market demands [information about Assa Abloy’s business strategy]’.101

(101) For the purpose of the decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers that the markets for each of (i) swing; (ii) sliding; and (iii) revolving automatic pedestrian doors (including for those with hermetic or fire- resistant features) are national in scope.

5.3. Industrial doors

5.3.1. Product market definition

5.3.1.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(102) The Notifying Party submits that, in line with the decisional practice of the Commission102 and the OFT103, automatic pedestrian doors should be distinguished from industrial doors.104

(103) In this regard, the Notifying Party submits that automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors address different customer needs and that manufacturers are not able to switch production easily across these door types for reasons of time, cost and expertise.105

(104) Within industrial doors, the Notifying Party submits that there is some degree of substitutability between high-speed doors, overhead sectional doors, industrial folding doors and docking doors and stations, since two or more of these types may fulfil the same or similar needs.106 Moreover, the Notifying Party submits that, while high-speed doors and overhead sectional doors are not always substitutable, there are situations where they may be interchangeable from a demand-side perspective.107

(105) Within high-speed doors, the Notifying Party submits that it is not necessary to consider further segmentations according to (i) whether they are used for interior or exterior applications; (ii) the specific application for which they are used; and (iii) whether they are made of rigid or fabric materials.108

5.3.1.2. Commission’s assessment

(106) In Assa Abloy/Cardo, the Commission noted that the market investigation had largely confirmed a distinction between automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors.109 Moreover, the Commission also noted that customers had indicated that ‘different industrial doors fulfil different functionalities’.110 The Commission ultimately left open the exact product market definition, given the absence of competition concerns in that decision.111

(107) As mentioned in paragraph (90) above, the results of the market investigation have confirmed that industrial doors and automatic pedestrian doors do not belong to the same product market.

(108) Regarding a further segmentation by types of industrial doors, a majority of end- customers and non-integrated suppliers having expressed an opinion in the market investigation submitted that customers do not use high-speed doors, overhead sectional doors, industrial folding doors and docking doors and stations for the same purposes.112 Conversely, a majority of OEMs having expressed an opinion in the market investigation submitted that customers may use these four types of industrial doors interchangeably.113

(109) Regarding a possible segmentation between interior and exterior applications, a vast majority of end-customers and non-integrated suppliers having expressed an opinion in the market investigation submitted that customers cannot use high-speed doors for interior and exterior applications for the same needs.114 While OEMs expressed mixed opinions in this regard, they unanimously submitted that the production of high-speed doors for internal and external applications is characterised by significant differences in technical characteristics and costs.115 Some respondents submitted that wind resistance is the main distinction between doors for interior and exterior use.116

(110) Regarding a possible segmentation by fabric and rigid versions of high-speed doors, a significant number of OEMs and end-customers submitted that high-speed doors in fabric and rigid versions are not substitutable for the same needs.117 Moreover, OEMs unanimously submitted that the production of high-speed doors in fabric and rigid versions is characterised by significant differences in technical characteristics and cost.118 Conversely, a majority of non-integrated suppliers considered that these two types of high-speed doors may be substitutable from a customer demand perspective.119

(111) A distinction between high-speed doors used for interior and exterior applications appears consistent with a distinction between high-speed doors in fabric and rigid version. Some OEMs, end-customers and non-integrated suppliers indicated that a distinction between high-speed doors in fabric and rigid version is only applicable to doors used for exterior applications.120

(112) A majority of respondents having expressed an opinion in the market investigation submitted that customers do not generally use (i) machine protection; (ii) food processing; (iii) clean rooms; (iv) cold storage; (v) material handling; and (vi) heavy industry high-speed doors for the same applications.121 In this regard, an OEM stated that each type of high-speed door has very specific uses and that a high-speed door used in the pharmaceutical industry is different to cold storage.122 Moreover, a vast majority of OEMs submitted that the production of each of these types of high-speed doors is characterised by significant differences in technical characteristics and cost.123

(113) For the purposes of this decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers appropriate to leave the exact product market definition open within the supply of industrial doors, since the competitive assessment would not differ irrespective of the segmentation. As a result, the Commission will specifically assess the impact of the Transaction on the supply of each relevant type of industrial doors, with a focus on high-speed doors where the overlap between the Parties’ activities is the most significant. Conversely, the Parties’ position remains similar irrespective of any sub-segmentation within high-speed doors based on (i) whether they are used for interior or exterior applications; (ii) the specific application for which they are used; or (iii) whether they are made of rigid or fabric materials.

5.3.2. Geographic market definition

5.3.2.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(114) The Notifying Party submits that the indirect channel for the sale of industrial door components is EEA-wide in scope given that OEMs sell industrial door components to non-integrated suppliers on an EEA-wide basis.124 In this regard, the Notifying Party submits that: (i) OEMs generally source components on a worldwide basis and supply products to non-integrated suppliers across the EEA from one or a few factories; (ii) shipping costs are low (between [1-10]%); (iii) industrial doors are certified according to European EN-standards; and (iv) it is not necessary to have local sales offices to be active on this market.125

(115) The Notifying Party submits that the direct channel for the sale of industrial door solutions is national in scope, while also pointing towards some indicators for the market being EEA-wide in scope.126 In this regard, the Notifying Party notes that sales to end users require a local service representative that is able to perform site visits to take measurements and advice the customer, as well as knowledge of the local language and business culture.127

5.3.2.2. Commission’s assessment

(116) In Assa Abloy/Cardo, the Commission noted that the ‘sourcing of industrial doors is not necessarily done on an EEA-wide level’.128 A Danish precedent concluded that the market for the sale of industrial doors is at least national and possibly wider.129

(117) The outcome of the market investigation supports defining national markets for the supply of industrial doors. In this regard, a majority of respondents having expressed an opinion on this point in the market investigation submitted that the technical specificities and the price of the industrial doors procured from OEMs vary to a material extent depending on the country of distribution.130 Suppliers of industrial doors also have sales forces dedicated to specific countries.131 Moreover, a majority of OEMs submitted that they do not supply industrial doors to end- customers situated in other countries where they do have local operations, while a majority of end-customers indicated that they do not source industrial doors from other countries.132

(118) For the purposes of this decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers the markets for high-speed doors is national in scope.

5.4. After-sales services

5.4.1. Product market definition

5.4.1.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(119) The Notifying Party submits that, in line with the decision practice of the Commission133 and of the OFT,134 after-sales services for automatic pedestrian doors should be distinguished from after-sales services for industrial doors.135 In this regard, the Notifying Party submits that services for the two door types have different features and are distinct in terms of service demands and requirements.

(120) The Notifying Party considers that there is insufficient demand- and supply-side substitutability between after-sales services for automatic pedestrian and industrial doors, because of two main reasons:136

(a) The provision of after-sales services for industrial doors requires more complex expertise from technical staff as well as specific tools due to mechanical characteristics and functionalities of industrial doors (such as height and complexity).

(b) In practice, service providers tend to focus their services on either industrial or automatic pedestrian doors. The Notifying Party submits that, if a technician for either pedestrian or industrial doors underwent training to provide after-sales services for the other, that technician could service both door types. However, the vast majority of service technicians have not received training for both industrial and automatic pedestrian doors.

(121) The Notifying Party submits that it would not be appropriate to further segment after-sales services according to (i) door type (e.g. within automatic pedestrian doors, for swing, sliding and revolving, and within industrial doors, for high-speed, overhead sectional, etc.);137 (ii) type of after-sales providers (e.g. OEMs, specialised service providers, non-integrated suppliers, elevator companies, facility management companies, or in-house service technicians);138 or (iii) customer groups.139

5.4.1.2. Commission’s assessment

(122) In Assa Abloy/Cardo, the Commission explained that the results of the market investigation broadly confirmed that after-sales services for industrial and automatic pedestrian doors were different. However, it ultimately left the market definition open.140

(123) The Commission inquired about a possible segmentation between the supply of after-sales services for automatic pedestrian doors, on the one hand, and for industrial doors, on the other hand. Further, the Commission inquired whether non- OEMs provided after-sales services on equal footing with OEMs, and whether different types of customer groups had different requirements and/or preferences regarding after-sales services for automatic pedestrian doors that may influence their choice of supplier (e.g. whether larger customers would prefer OEMs).

(124) Regarding the distinction between after-sales services for automatic pedestrian and industrial doors, the majority of respondents to the Commission’s market investigation that expressed an opinion on this point indicated that these constitute separate product markets. Respondents consider that there is a lack of supply-side substitutability for servicing between these doors. A respondent indicated that industrial doors ‘[i]s a product that needs more specialized technici[a]ns’.141 An end-customer expressed that ‘[m]echanisms and build are fundamentally different. On that basis, we would expect different technicians and service requirements’.142

(125) Regarding a potential further segmentation per door type, the outcome of the market investigation indicates that neither after-sales services for automatic pedestrian doors nor for industrial doors should be further segmented per door type (e.g. for automatic pedestrian doors, swing, sliding, revolving, and for industrial doors, high-speed, overhead sectional, folding etc.). The outcome of the market investigation shows that technicians carry out after-sales services for all types of automatic pedestrian doors.143

(126) Regarding a potential further segmentation per type of after-sales service provider, the outcome of the market investigation reveals that, even though third-party providers do service automatic doors, they are not technically in a position to provide the same range and level of services as the original OEM.144 This is mostly due to higher costs of spare parts, less availability of spare parts and specific tools and documentation and less experience on the doors than the original OEM.145 Further, several respondents explained that it was particularly problematic to source spare parts and specific tools and documentation from the Parties at a reasonable cost and lead-time.146 A competing OEM expressed that: ‘[a]ccess to third-party spare parts is not easy, both in terms of sourcing and of pricing. Certain companies are not helpful or friendly when asked to provide their spare parts. Assa Abloy is known to be the most defensive competitor, whose spare parts are most difficult to access.’147 This finding further confirms the inherent connection between the supply of doors and the provision of after-sales services and the differentiated nature of the latter.

(127) However, even though different types of service providers may be in a different position when it comes to offering the same after-sales services, the Commission considers that there is a continuum of after-sales services for which demand- and supply-side substitutability varies, thereby justifying the definition of a single overall market for the supply of after-sales services (for each of, respectively, automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors), thus excluding a segmentation per type of provider. However, the respondents’ views about the differentiated nature of the provision of after-sales services will be taken into account in the competitive assessment, notably to assess competitive constraints (for each of, respectively, automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors).

(128) Regarding a potential further segmentation of after-sales services per type of customer groups, the majority of respondents who expressed an opinion on this point consider that the relevant market may be further segmented according to specific customer groups. In particular, the market investigation reveals that larger customers and larger projects tend to prefer OEMs for their after-sales services needs.148

(129) Even though specific customer groups for after-sales services may have a preference for OEMs over independent after-sales services providers, the Commission considers that there is an inherent heterogeneity in these customer group categories, thereby justifying the definition of a single overall market for the supply of after-sales services (for each of, respectively, automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors), excluding a segmentation per customer group. However, customer preferences will be taken into account in the competitive assessment, notably to assess effective competitive constraint, with reference to after-sales services for larger clients and projects.

(130) For the purposes of this decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers that the markets for after-sales services for automatic pedestrian doors, on the one hand, and industrial doors, on the other hand, constitute separate relevant product markets. Conversely, no further segmentation by type of door, type of after-sales services providers, or customer group is warranted for the purpose of assessing the present Transaction.

5.4.2. Geographic market definition

5.4.2.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(131) Regarding after-sales services for both automatic pedestrian and industrial doors, the Notifying Party submits that, in line with the Commission’s precedents and those of the Danish Competition and Consumer Authority (for after-sales for industrial doors)149 and the OFT,150 the relevant geographic market is national.151 This is because suppliers of after-sales services need a local sales force and a local service network, and the conditions of competition are generally similar across the whole of individual countries.152 The Notifying Party submits that it would not be appropriate to further segment after-sales services according to geographical spread of the customer.153

5.4.2.2. Commission’s assessment

(132) In Assa Abloy/Cardo, the Commission explained that the results of the market investigation broadly confirmed that the scope of the market for after-sales services was national. However, it ultimately left the definition open.154

(133) The market investigation has confirmed the Commission practice in Assa Abloy/Cardo endorsed by the Parties that the scope for after-sales services for automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors is national in scope. The vast majority of respondents who expressed an opinion on this point consider that the markets for after-sales services for each of, respectively, automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors have a national scope. 155

(134) Several end-customers expressly stated that ‘we want a company to have national coverage’ and ‘national coverage is a key factor in [the] decision-making process’.156

(135) The outcome of the market investigation indicates that there is no need to further segment after-sales services per geographical spread of the customer, as the market is national in scope.157 This also means that, as was assessed in the product market definition for after-sales services, it is not necessary to make a distinction between large customers with national operations versus small customers with local operations.

(136) For the purposes of this decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers that the relevant geographic market for after-sales services is national in scope.

5.5.Spare parts

5.5.1. Product market definition

5.5.1.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(137) The Notifying Party submits that generic spare parts should be distinguished from brand-specific spare parts. The Notifying Party submits that the manufacture and supply of brand-specific spare parts should be considered as multiple markets with a distinct market for each manufacturer of automatic pedestrian doors or industrial doors. The Notifying Party considers that, in principle, sales of brand-specific spare parts are captive sales, for which other manufacturers than the OEMs cannot compete.158

(138) Further, the Notifying Party submits that spare parts for automatic pedestrian doors and industrial doors should be distinguished (both for generic and brand-specific spare parts).159

5.5.1.2. Commission’s assessment

(139) The Commission has analysed the relevant product market definition for spare parts in other industries, such as in the automotive industry, the aircraft industry and the agricultural machinery industry. Regarding the automotive industry, in VW- Audi/VW-Audi Sales Centres and Volkswagen/Hahn + Lang the Commission identified automotive spare parts as a separate relevant product market, and carried out its competitive assessment under this premise.160 In the aircraft industry, the Commission has considered a relevant product market for spare parts that was separate from the provision of Maintenance Repair and Overhaul (‘MRO’),161 although in other cases it also considered that the provision of MRO services may also include the provision of spare parts.162 Regarding the agricultural machinery industry, in DA Agravis Machinery / Konekesko Eesti/ Konekesko Latvija / Konekesko Lietuva / Konekesko Finnish Agrimachinery Trade Business, the parties to the case presented spare parts and after-sales services as separate product markets. The Commission did not contest this submission, and ultimately left the question open.163

(140) In the present case, in view of the industry structure, including the variety of independent after-sales services providers, and the concerns raised over the course the market investigation about access to spare parts in order to supply after-sales services,164 the Commission considers appropriate to distinguish separate product markets for spare parts (including technical information and servicing tools) and after-sales services, spare parts being an input for the provision of a range of after- sales services.

(141) In its investigation, the Commission inquired into a possible segmentation between brand-specific spare parts on the one hand, and generic spare parts on the other.

(142) The vast majority of competitors and non-integrated suppliers consider that automatic pedestrian doors, in particular operators, are composed of brand-specific parts subject to a proprietary design on the one hand, and generic parts on the other.165 All the competitors that expressed a view in this point and the vast majority of non-integrated suppliers consider that brand-specific parts are not substitutable with parts originating from a third party supplier, whereas generic parts can be sourced from third-party suppliers.166

(143) For the sake of clarity, in this Decision, the Commission will only address the market of brand-specific spare parts, and will name these as ‘spare parts’ (instead of ‘brand-specific spare parts’) This is because, as mentioned in footnote the Parties do not manufacture generic spare parts for automatic pedestrian doors and are only involved to a limited extent in the supply of generic spare parts.26

(144) For the purposes of this decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers that spare parts (including technical information and servicing tools) constitute a relevant product market separate from after-sales services, and that brand-specific spare parts and generic spare parts constitute separate relevant product markets.

5.5.2. Geographic market definition

5.5.2.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(145) The Notifying Party considers the markets for the manufacture and supply of brand-specific and generic spare parts for automatic pedestrian doors is at least EEA-wide and possibly global. The Notifying Party argues that spare parts are interchangeable, and therefore spare parts sold in one country could be used or resold again in a different country without difficulties.167

(146) Regarding both brand-specific and generic spare parts for industrial doors, the Notifying Party submits that these markets should be considered as global. The Notifying Party argues that the same spare parts are manufactured and supplied on a global basis, and that EU or national approval requirements, safety regulations and certifications do not generally affect the individual components/spare parts.168

5.5.2.2. Commission’s assessment

(147) In Assa Abloy/Cardo, the Commission (where, as mentioned, the Commission did not contest the Parties’ submission that considered spare parts to be included within after-sales services), explained that the results of the market investigation broadly confirmed the national scope of the markets for after-sales services for industrial and automatic pedestrian doors. However, it ultimately left the definition open.169

(148) The Danish Competition and Consumers Authority, in its Assa Abloy/Nassau decision, considered that the geographic market for the wholesale supply of components and spare parts could be limited to Denmark, and possibly be broader, but ultimately left the definition open.170

(149) Respondents to the market investigation have explained that it is difficult to source spare parts from other countries as a workaround if having difficulties sourcing spare parts. In particular, a competing OEM expressed that: ‘[w]orkarounds for spare part sourcing are difficult (e.g. sourcing spare parts from […] different Member States and then shipping them internally), and they are hampered by differences in part numbers: the part number of a given spare part differs from country to country. [The competing OEM] tried in the past to ship spare parts to the United Kingdom from Switzerland, but was unsuccessful.’171

(150) Therefore, as there seem to be difficulties in sourcing spare parts from other Member States, and as the demand for spare parts is national, it would be appropriate to consider the market for spare parts for automatic doors (both pedestrian and industrial) to be national in scope.

(151) For the purposes of this decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers that the geographic market definition of spare parts for the purpose of providing after-sales services for both automatic pedestrian and industrial doors is national in scope.

5.6. Access control systems and components

5.6.1. Product market definition

5.6.1.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(152) The Notifying Party refers to the decisional practice of the Commission which, in UTC/GE Security, assessed electronic access control systems in the broader context of electronic security systems (‘ESS’), i.e. products designed for the protection of people, assets and property by electronic means.172 It also mentions the decision B5-25/08 ASSA ABLOY/SimonsVoss AG of the German Federal Cartel Office (‘FCO’) in which the manufacturing and wholesale supply of access control systems was considered a separate product market.173 A possible further sub- segmentation into an electronic access control systems segment is also mentioned.174 Overall, the Notifying Party submits that for the assessment of the present Transaction, it is not necessary to conclude whether electronic access control systems belong to a separate relevant product market or not.175

5.6.1.2. Commission’s assessment

(153) As put forward by the Notifying Party, in UTC/GE Security, the European Commission considered a market for ESS comprising access control systems.176 It however left open the precise market definition and did not conclude on the delineation of separate markets for the supply of EES products and the installation and maintenance of ESS.

(154) The results of the market investigation conducted by the Commission in the present case reveal that the majority of competitors and direct customers consider that access control systems and other types of ESS are not used interchangeably by customers for the same applications.177 However, the majority of non-integrated suppliers are of the opposite view.178

(155) In addition, the majority of competing OEMs of automatic pedestrian doors and end-customers state that access control systems (software) and access control components (hardware) are generally sourced by customers as a package/complete solution.179

(156) For the purposes of this decision and in light of all information available to it, the Commission considers appropriate to leave the exact product market definition open since the competitive assessment would not differ irrespective of the segmentation.

5.6.2. Geographic market definition

5.6.2.1. Notifying Party’s arguments

(157) The Notifying Party refers to the decisional practice of the Commission which in UTC/GE Security found that the majority of the customers were able to source electronic security systems on an EEA-wide or even worldwide basis, yet it ultimately left open the geographic market definition.180

(158) The Notifying Party submits that if the definition of a distinct electronic access control systems segment is to be considered appropriate, the relevant sales are EEA-wide.181 It further submits that the relevant components, the installation methods and the expertise are the same throughout the EEA. Moreover, major suppliers are reported to be active across the EEA, with the assistance of installation often subcontracted locally.

5.6.2.2. Commission’s assessment

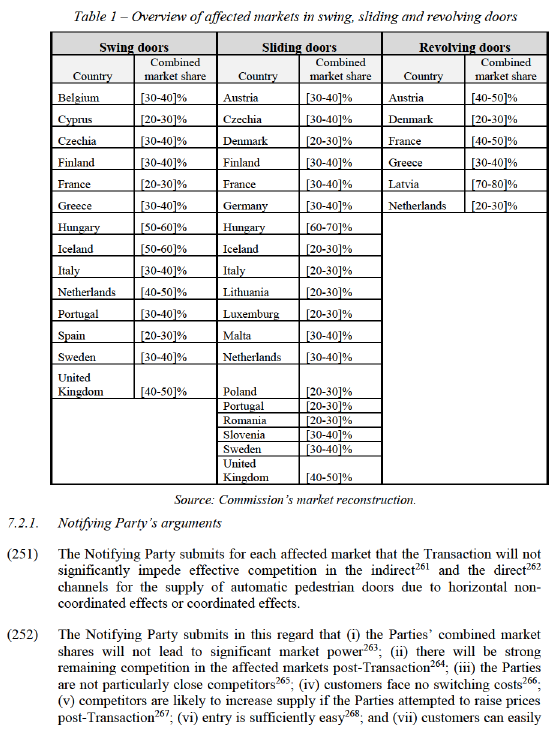

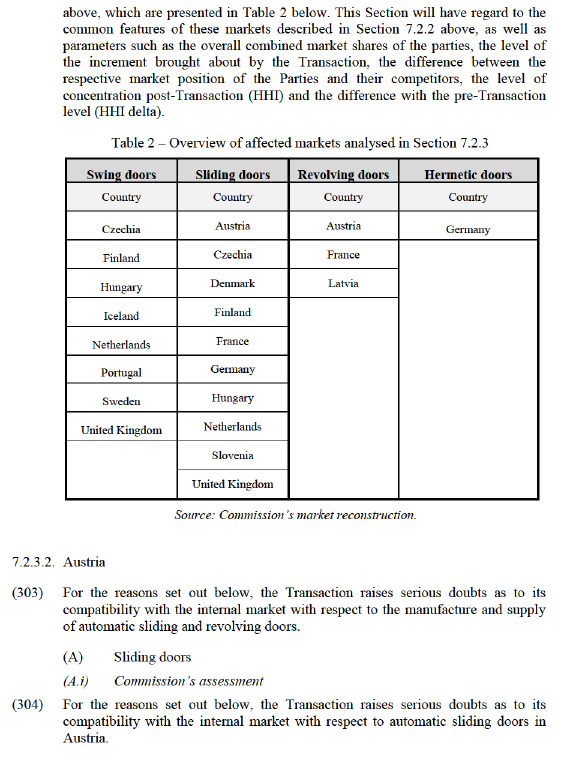

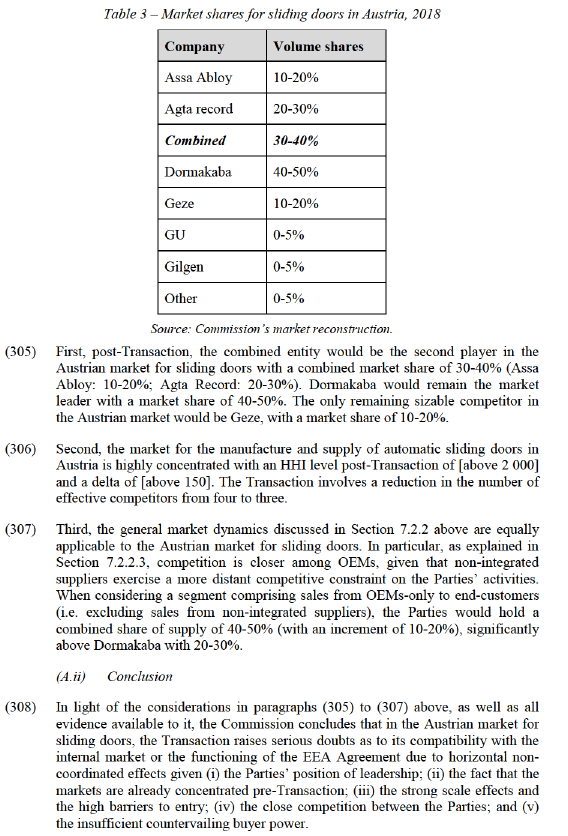

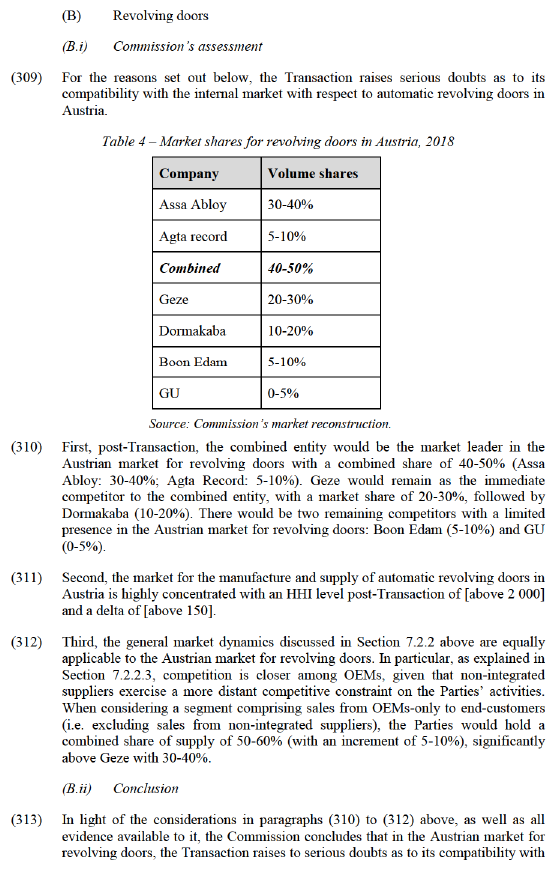

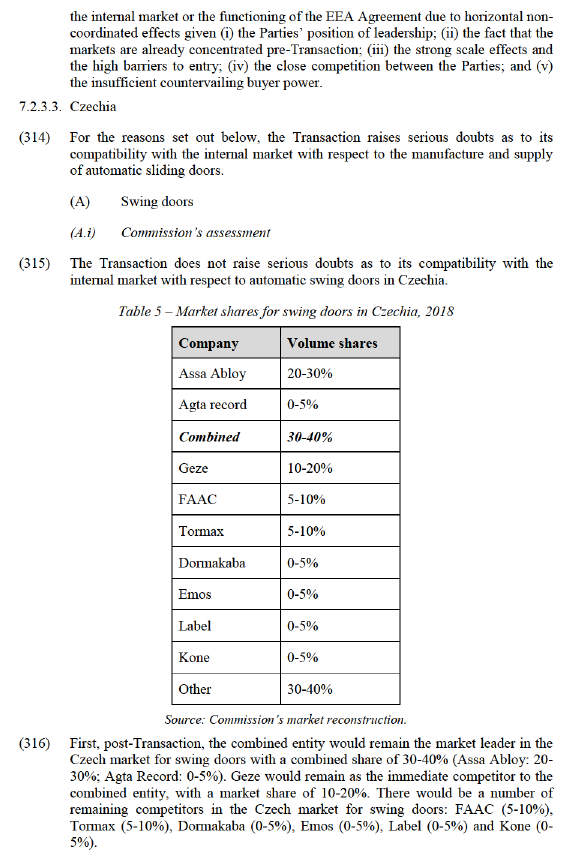

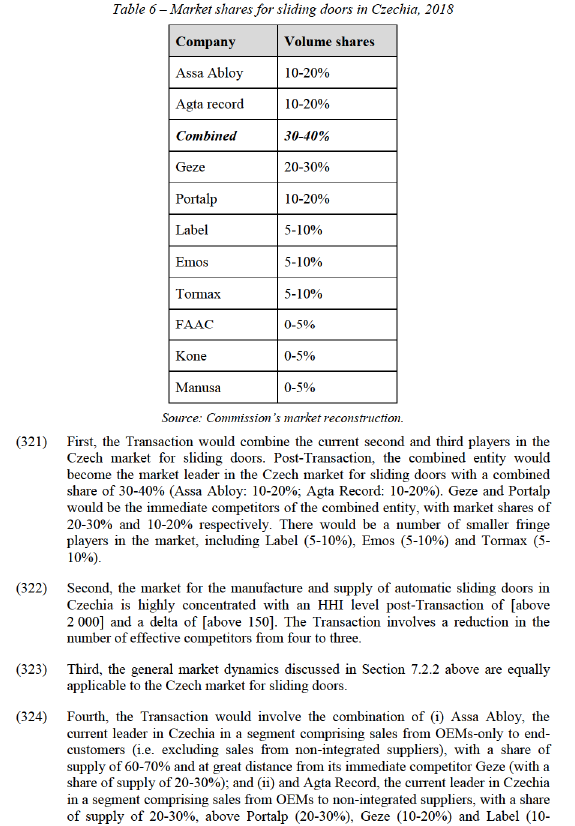

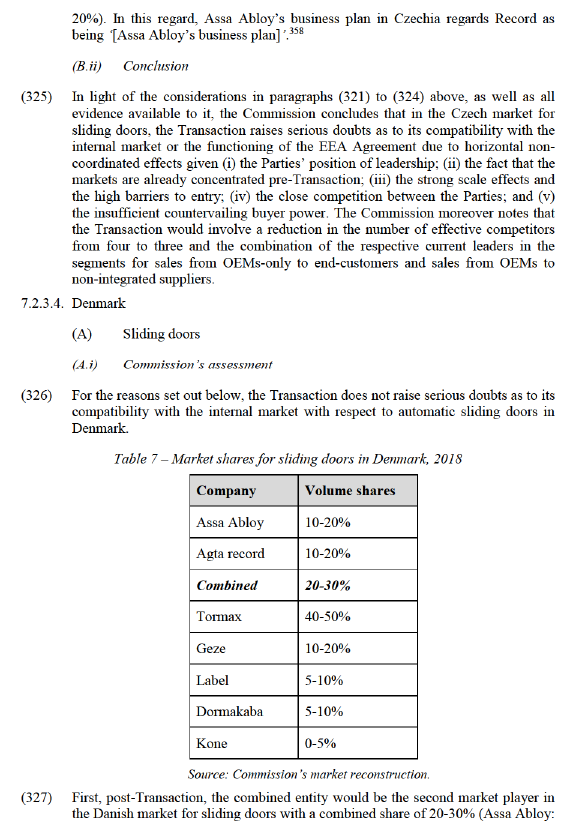

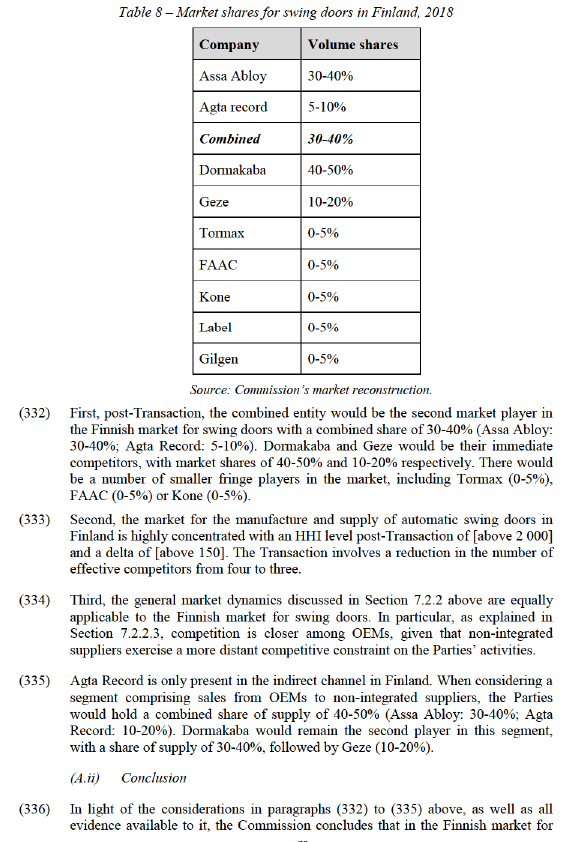

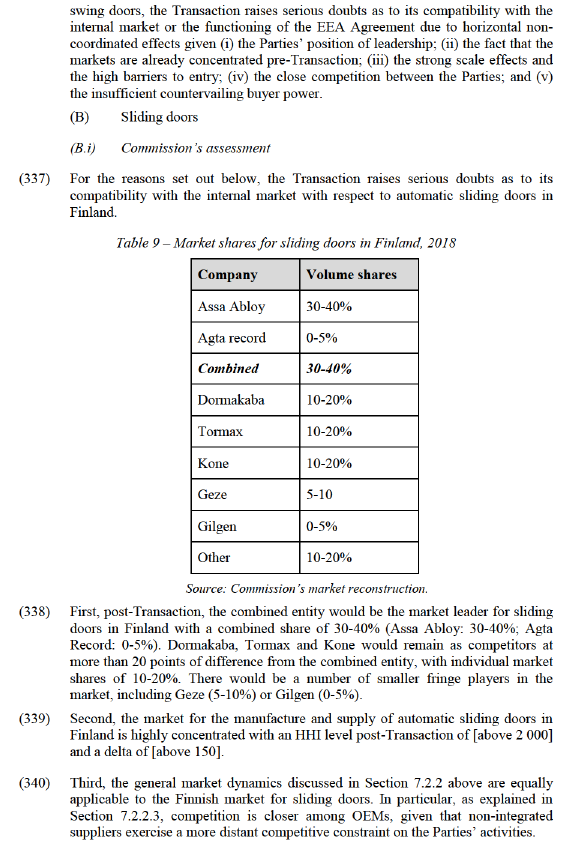

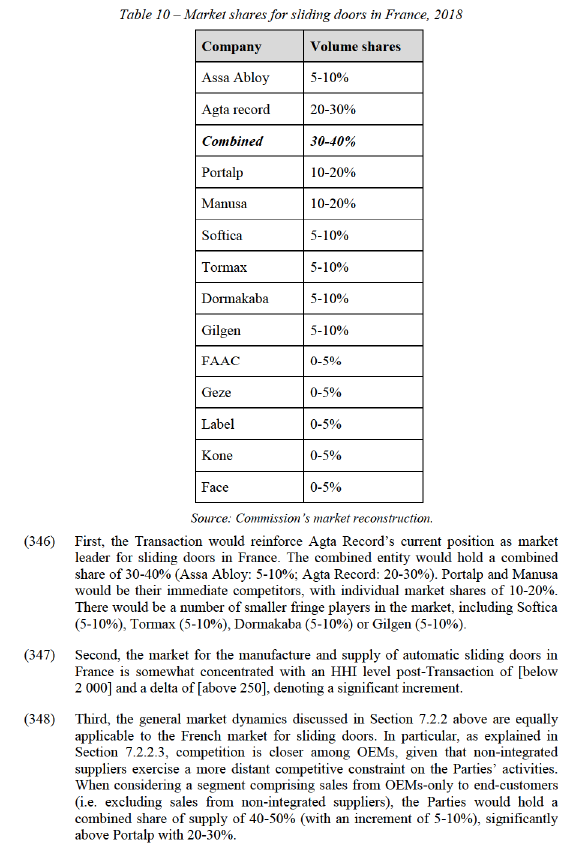

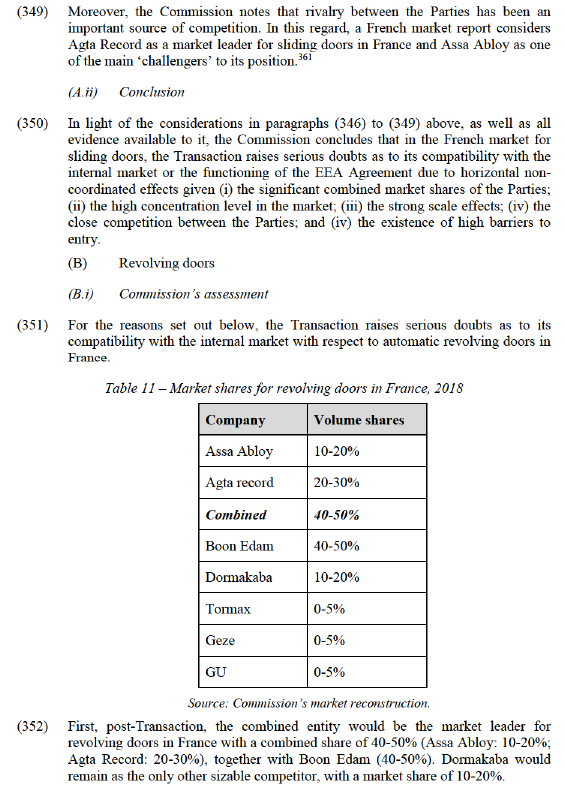

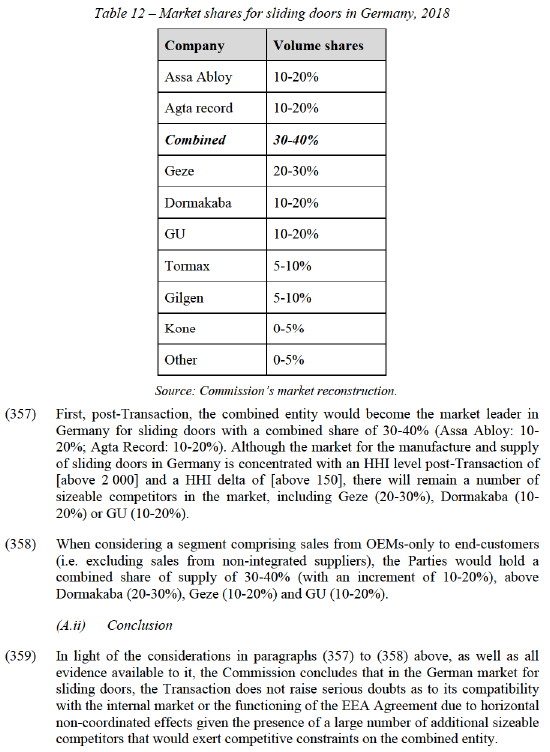

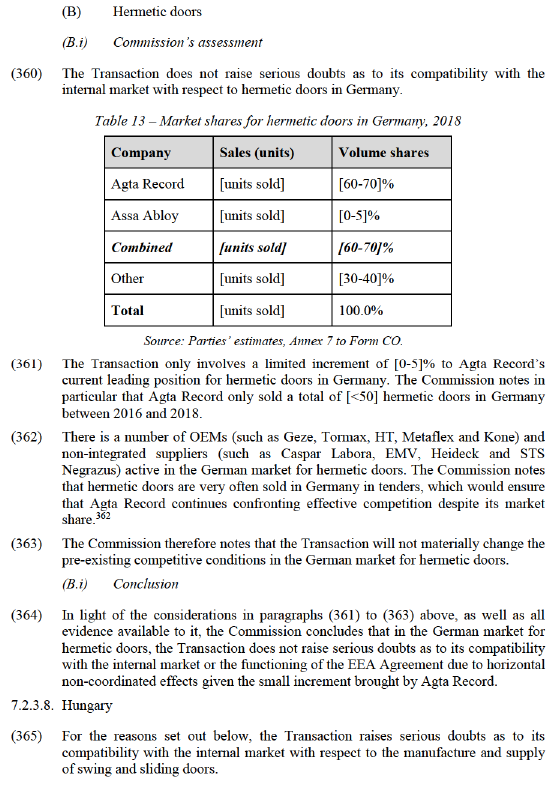

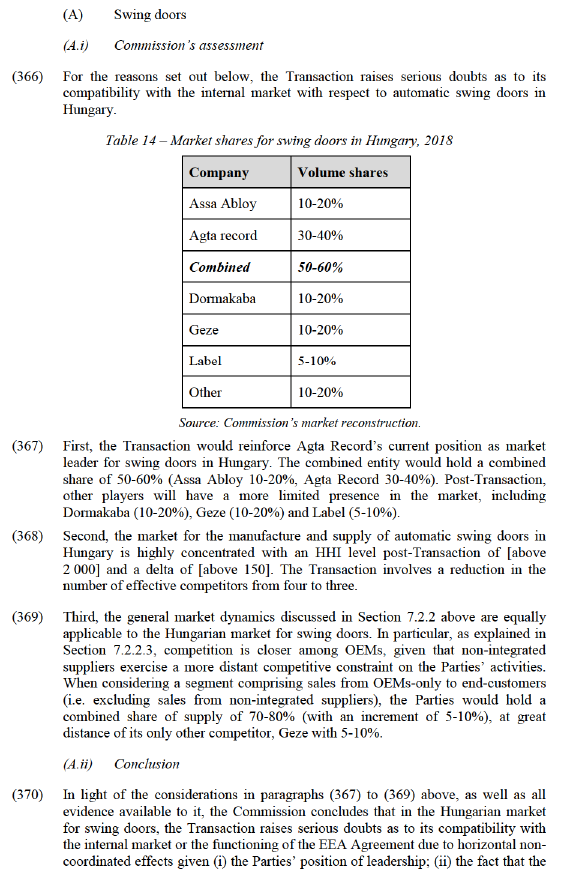

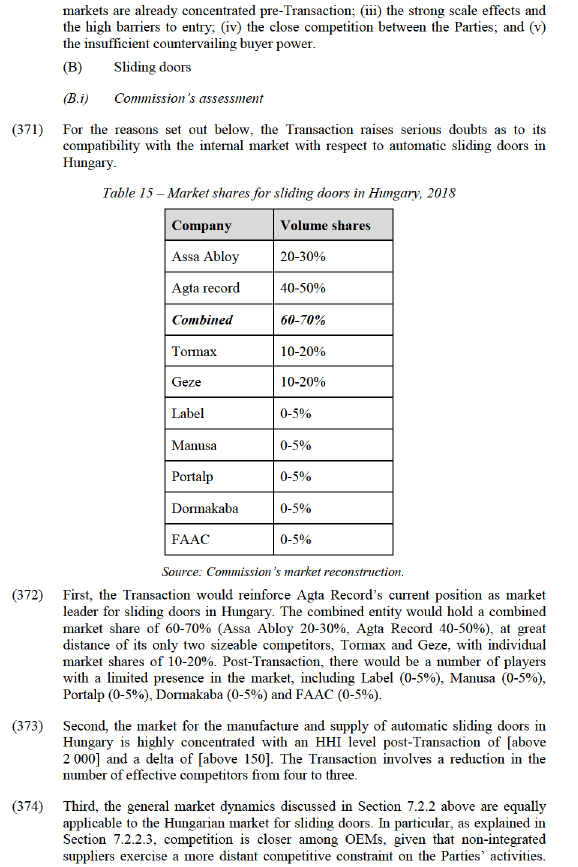

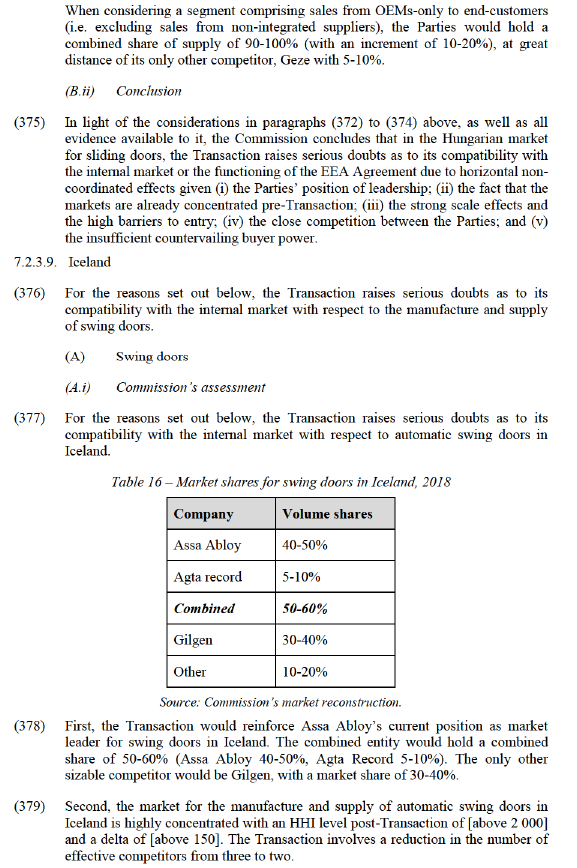

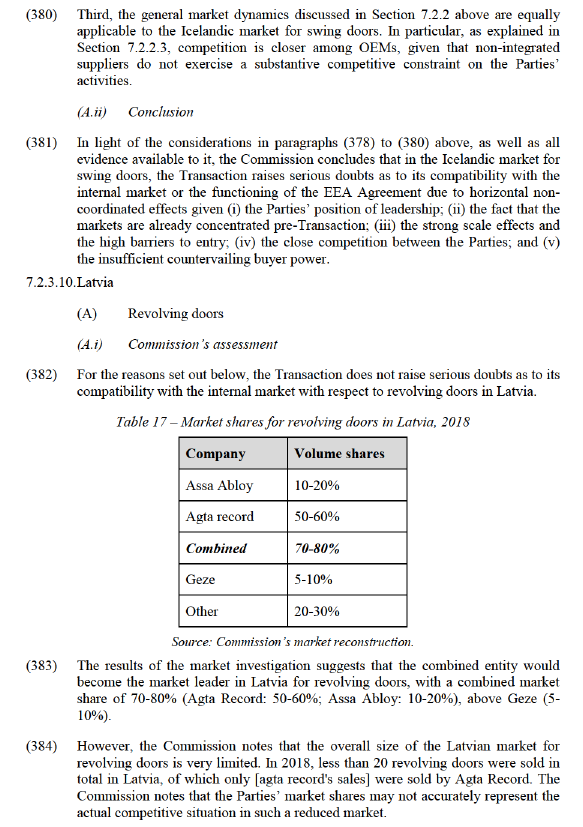

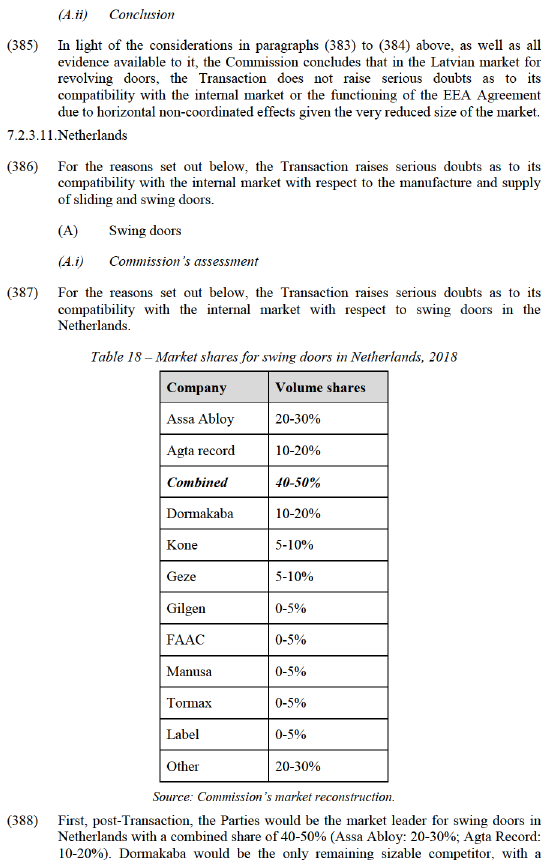

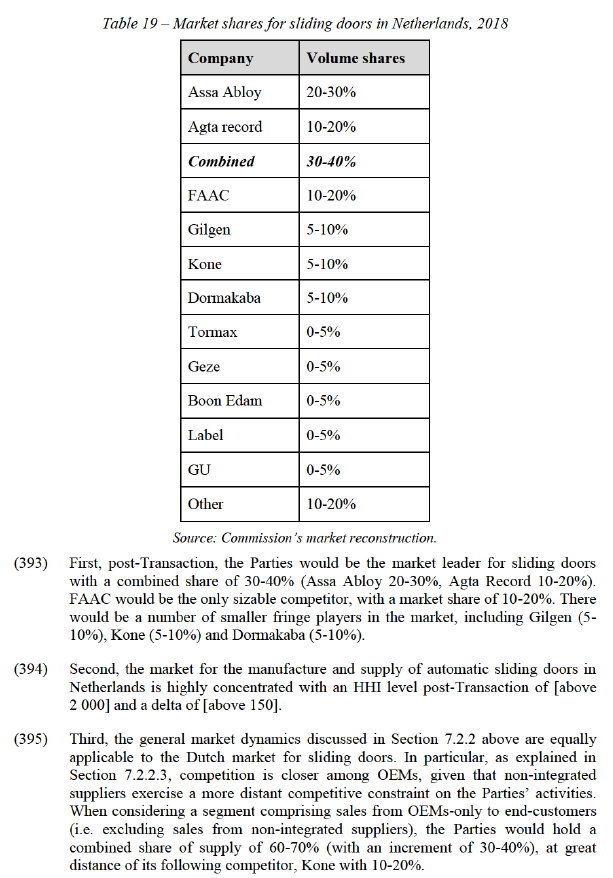

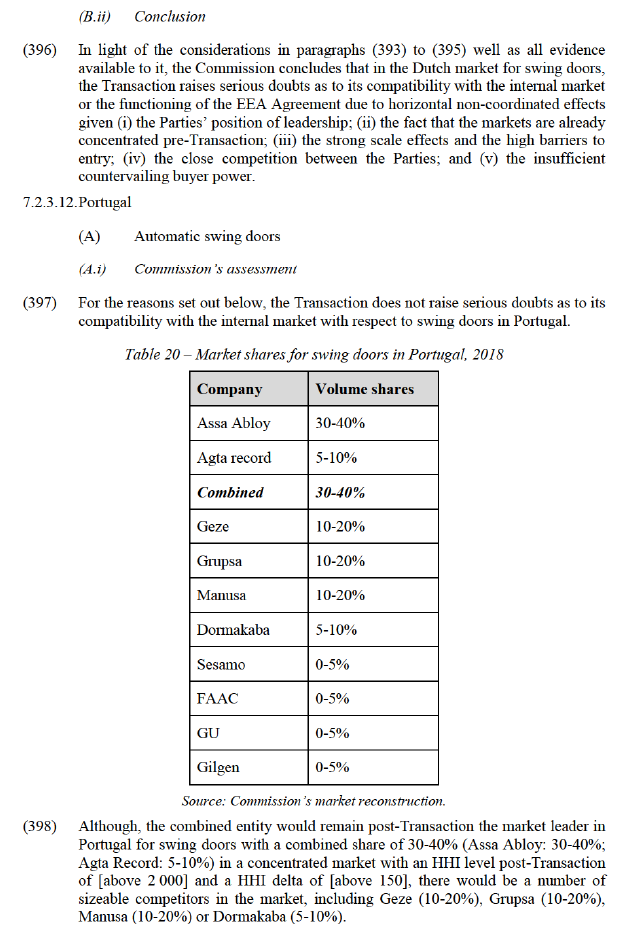

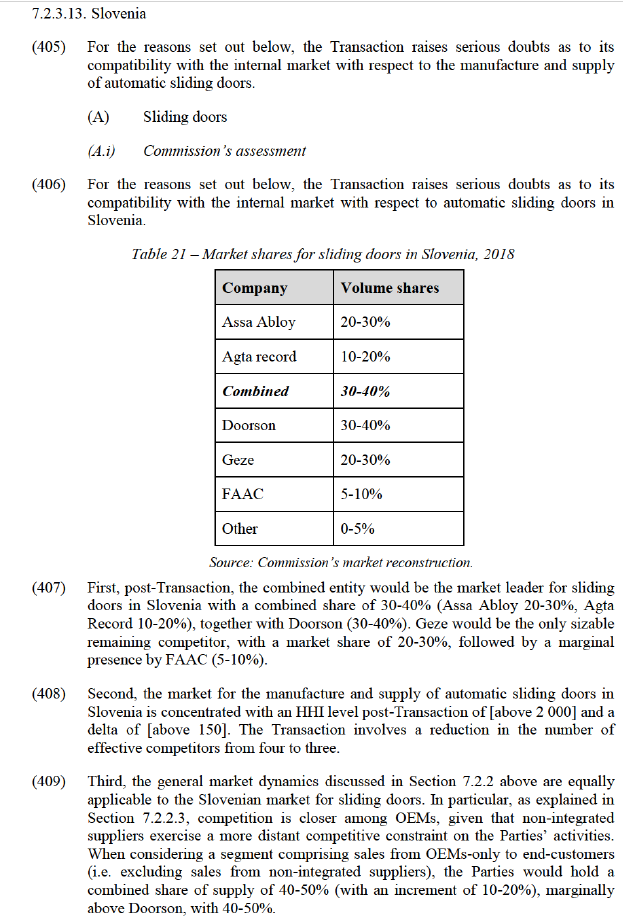

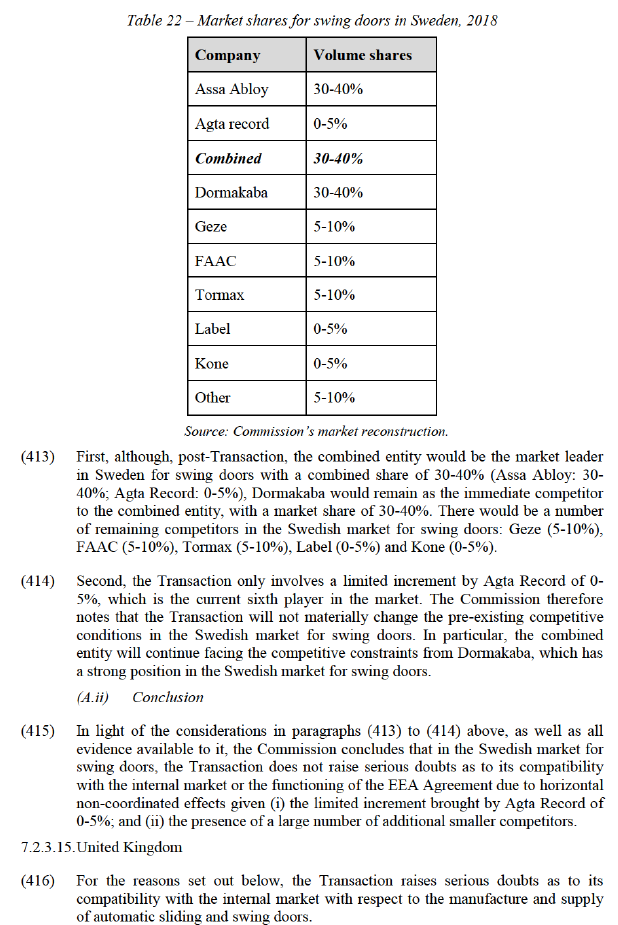

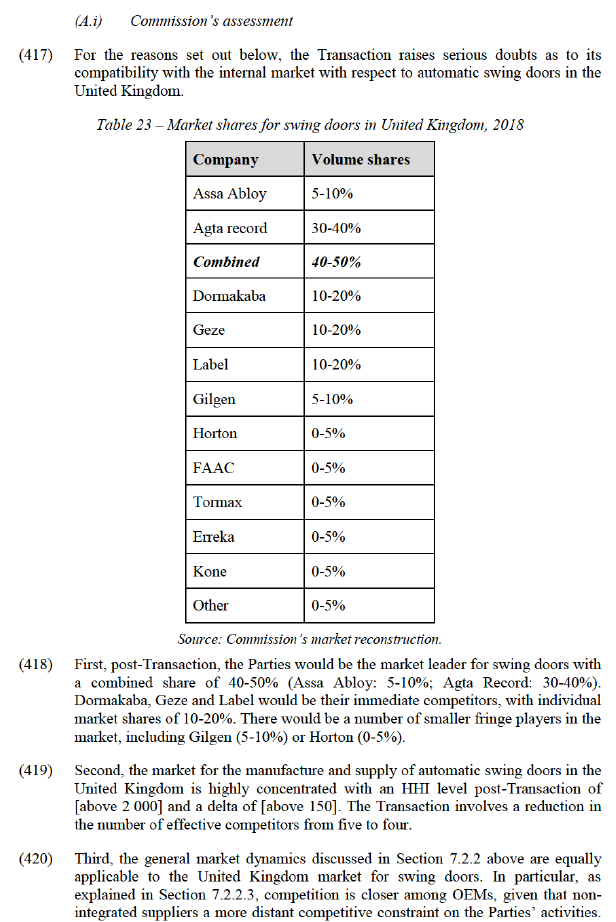

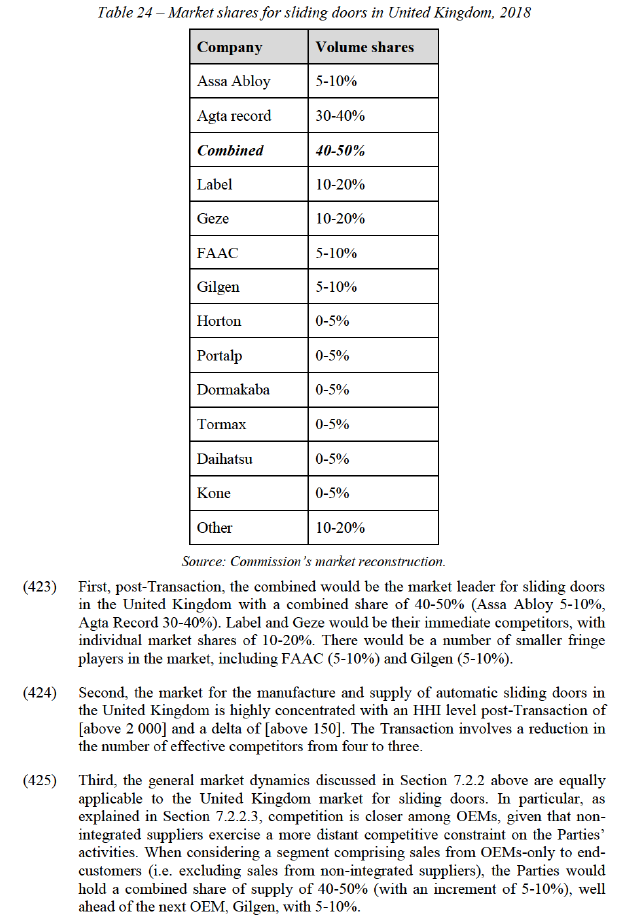

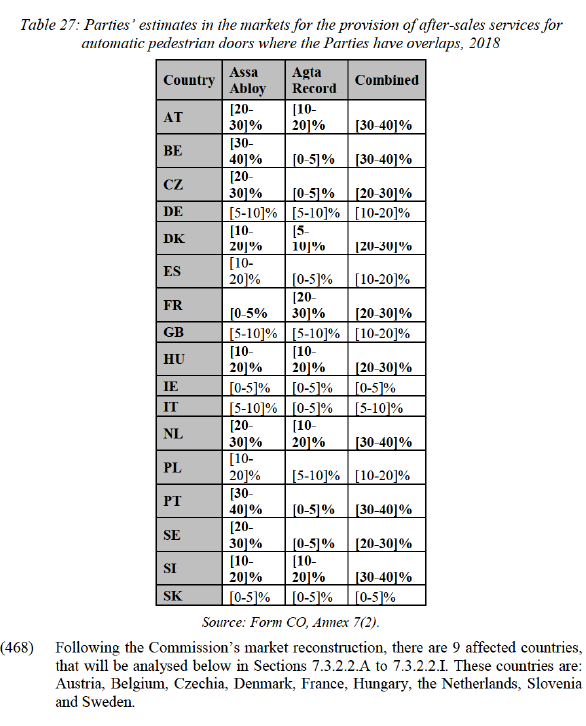

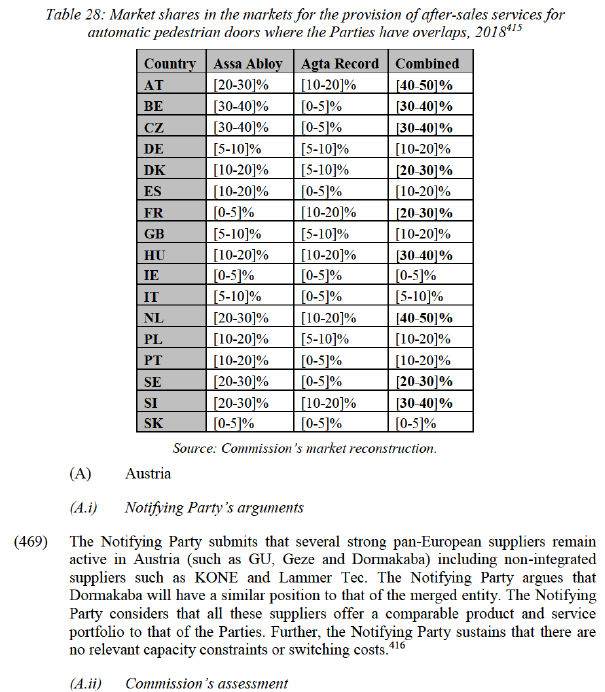

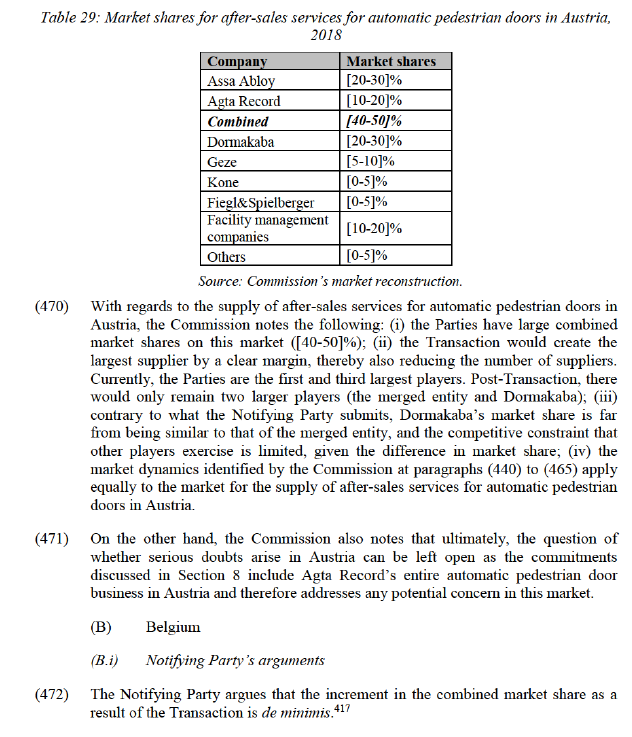

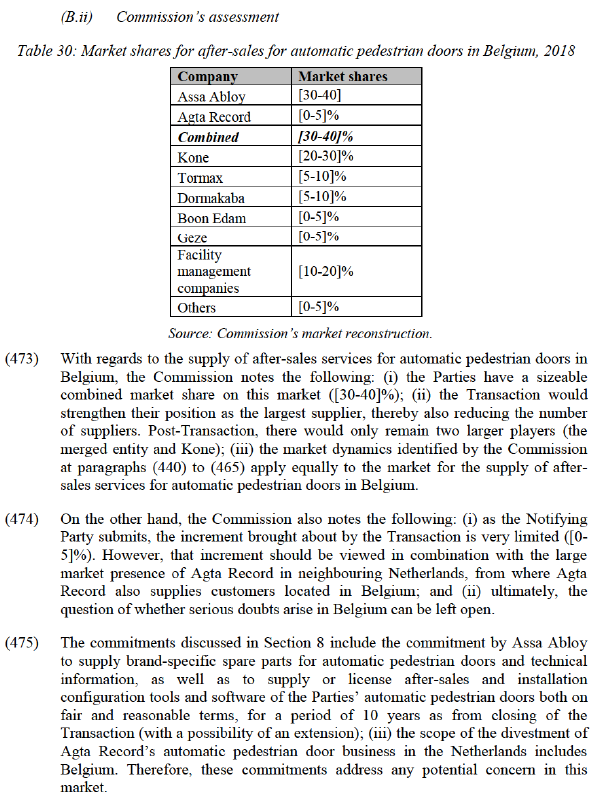

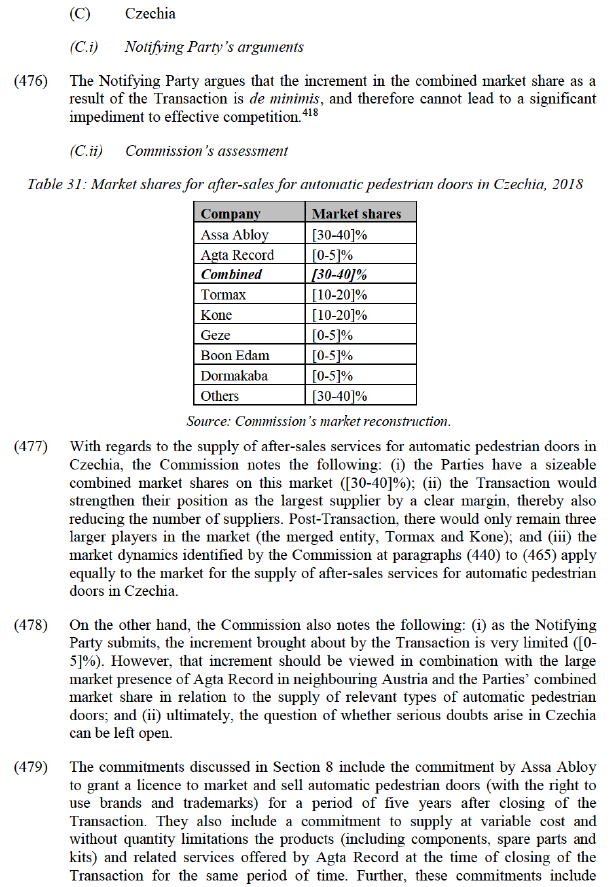

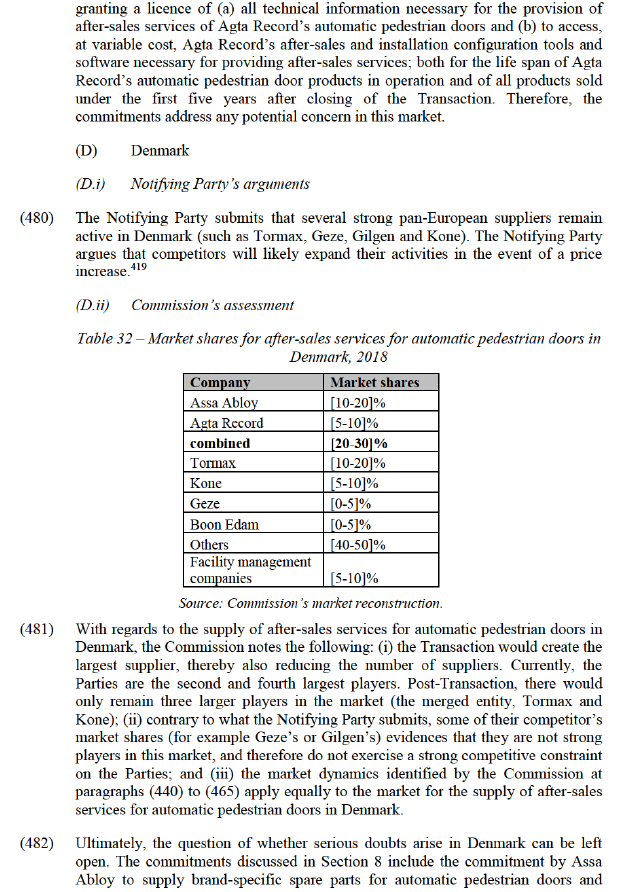

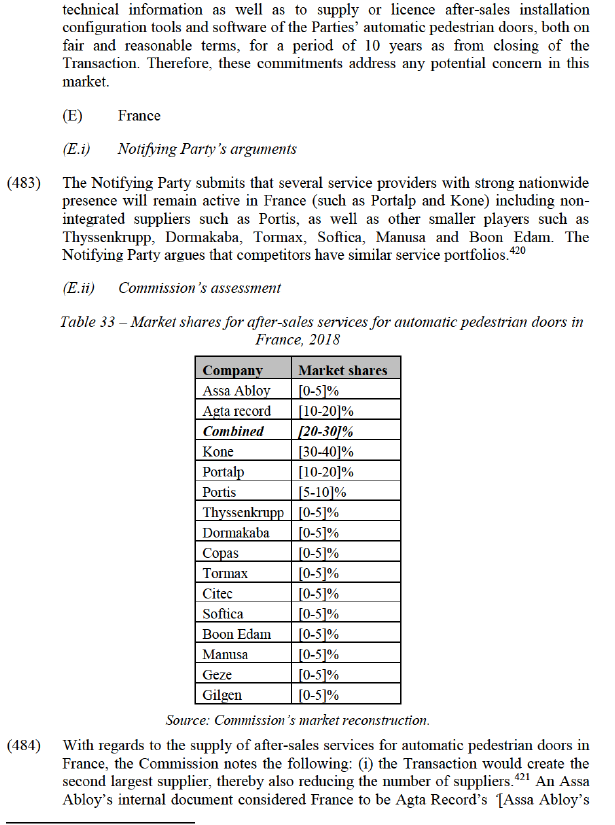

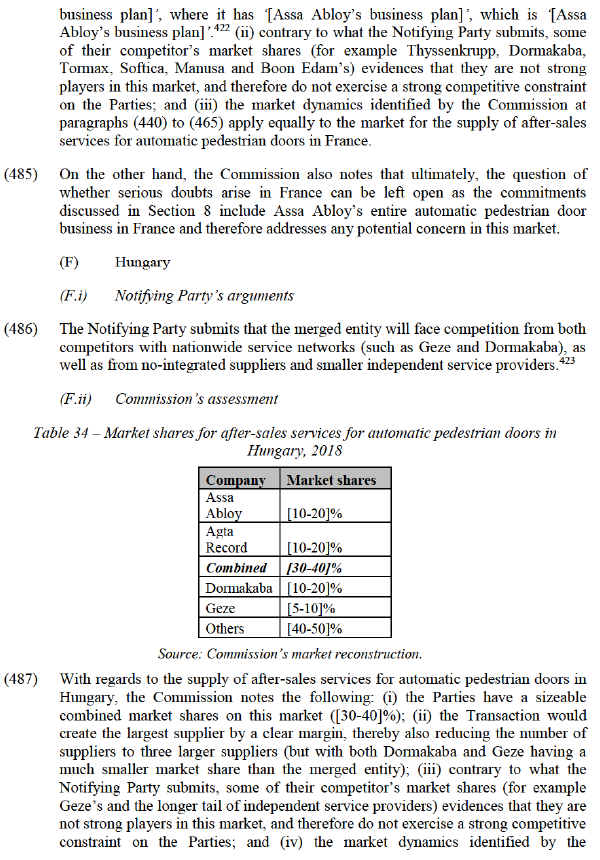

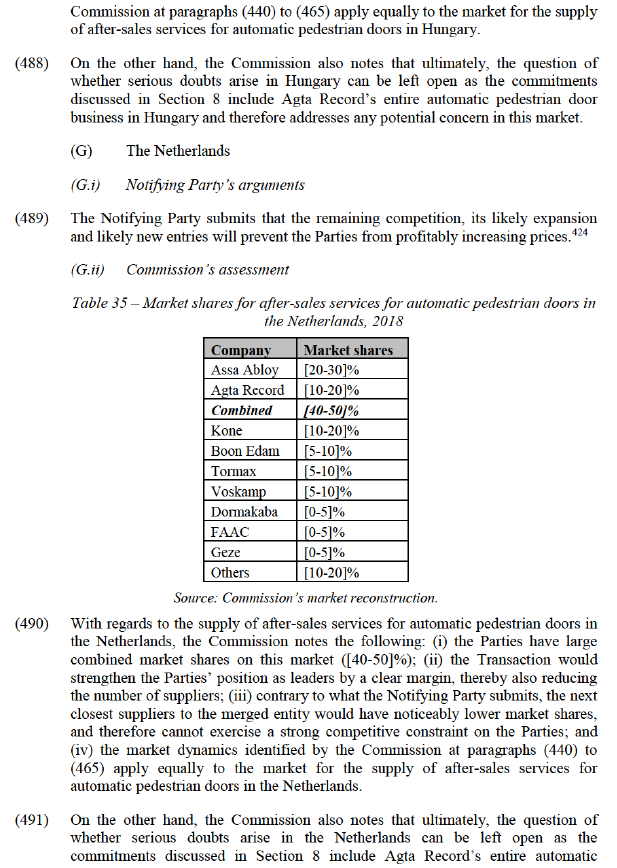

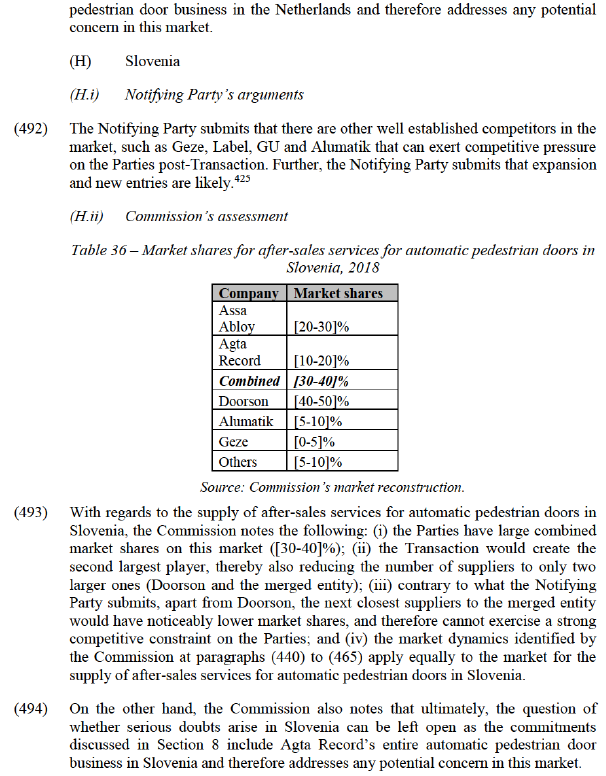

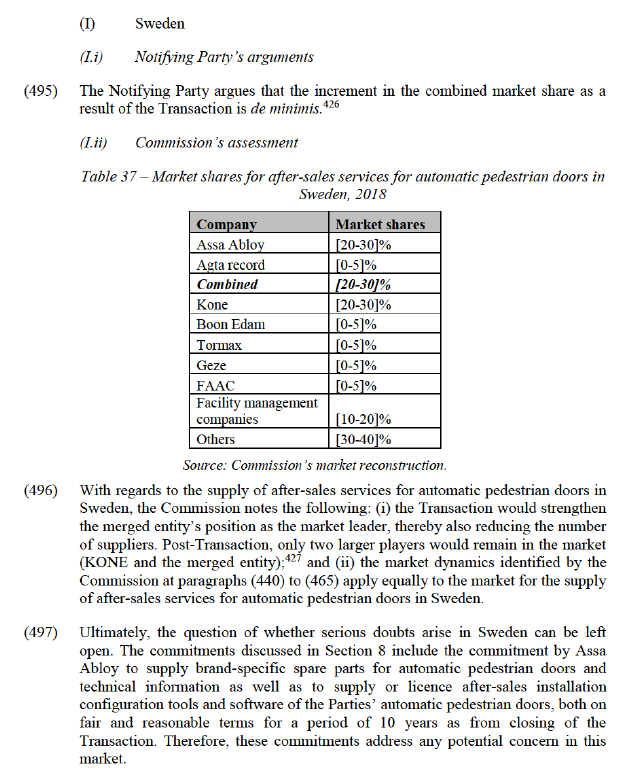

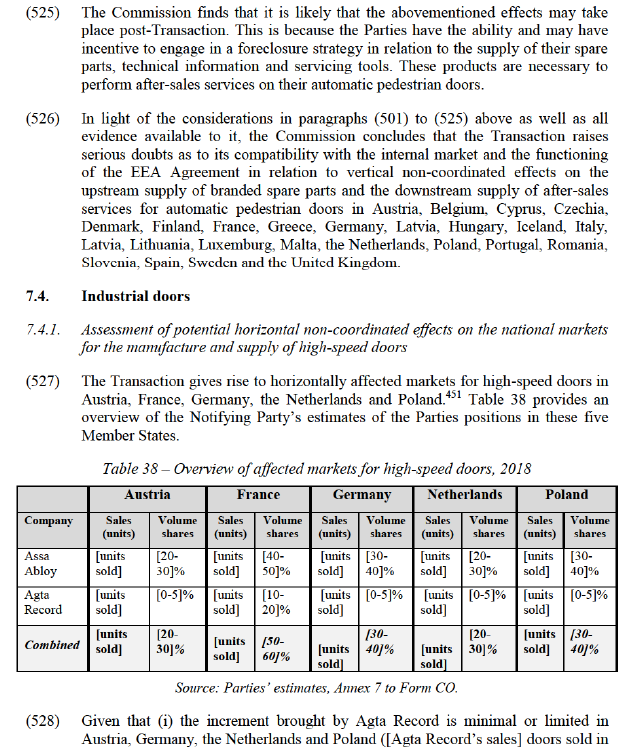

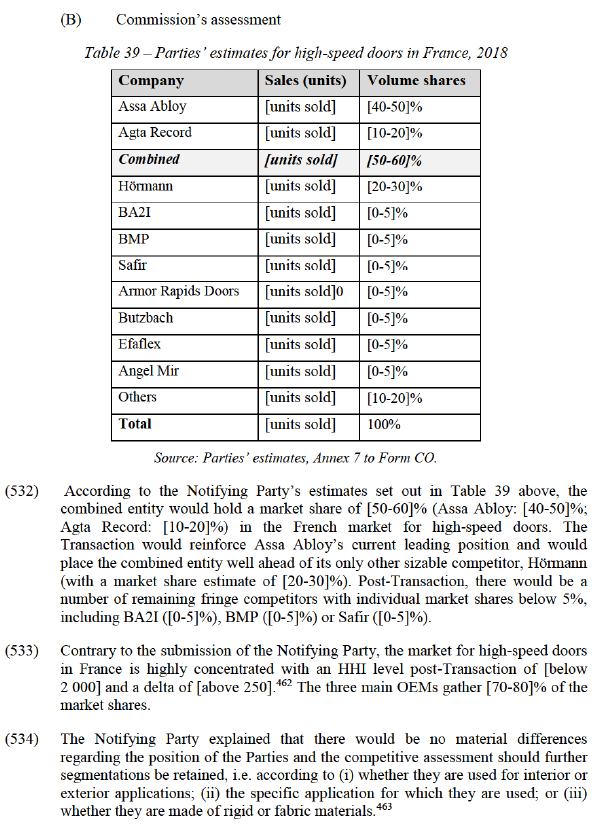

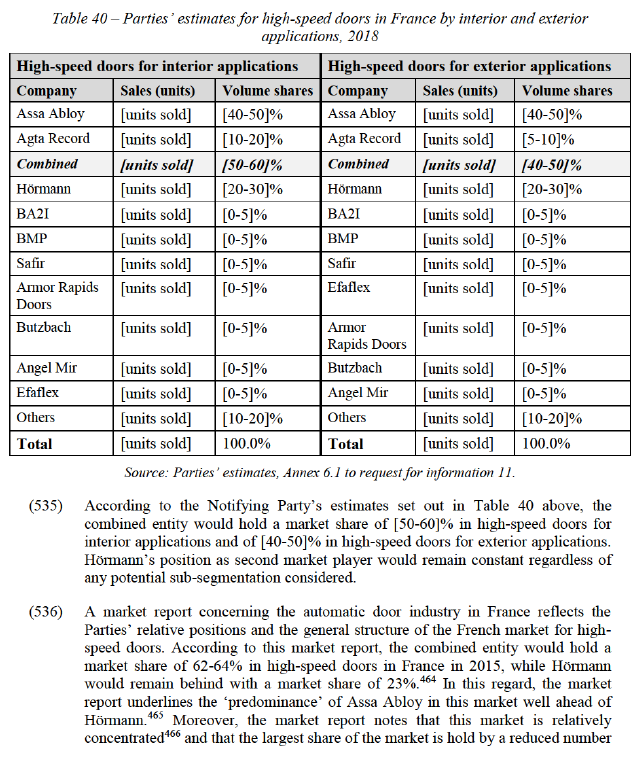

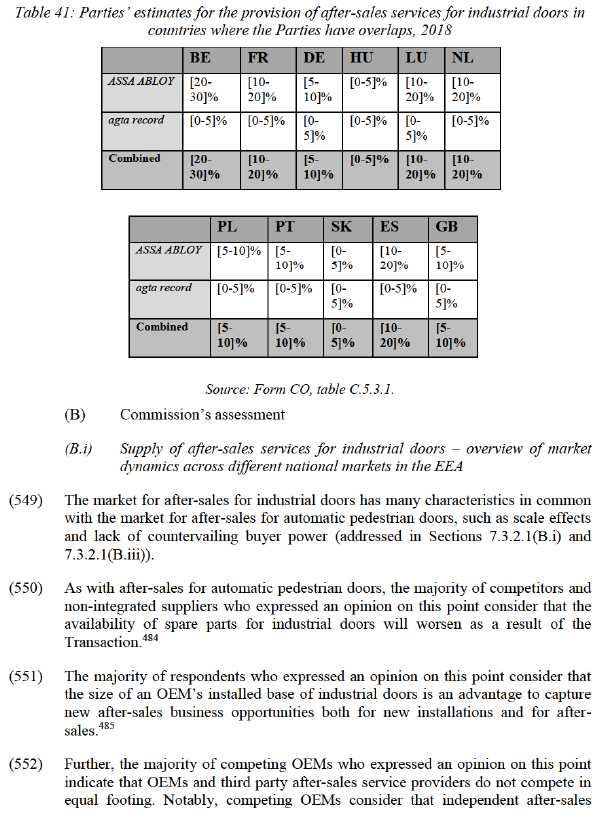

(159) As put forward by the Notifying Party, in UTC/GE Security the Commission analysed the geographic market for ESS, yet it ultimately left open the exact market definition.182