Commission, October 1, 2019, No M.9706

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

NOVELIS / ALERIS

COMMISSION DECISION of 1.10.2019

declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the EEA agreement

(Case M.9076 - NOVELIS / ALERIS)

(Text with EEA relevance) (Only the English text is authentic)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area, and in particular Article 57 thereof,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings1, and in particular Article 8(2) thereof,

Having regard to the Commission's decision of 25 March 2019 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given the undertakings concerned the opportunity to make known their views on the objections raised by the Commission,

Having regard to the opinion of the Advisory Committee on Concentrations, Having regard to the final report of the Hearing Officer in this case, Whereas:

1. INTRODUCTION

(1) On 18 February 2019, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (the ‘Merger Regulation’) by which Novelis Inc. (‘Novelis’, USA), a fully owned subsidiary of Hindalco Industries Limited (‘Hindalco’, India), acquires, within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation, sole control of the whole of Aleris Corporation (‘Aleris’, USA) by way of purchase of shares2 (hereinafter the ‘Transaction’). Novelis is designated hereinafter as the ‘Notifying Party’.3 Novelis and Aleris are designated hereinafter as the ‘Parties’. The entity resulting from the Transaction is designated hereinafter as the ‘Merged Entity’.

(2) Novelis is a global manufacturer of flat rolled aluminium4 products and a recycler of aluminium. The company operates 24 manufacturing facilities across North America, South America, Europe and Asia. Novelis’ parent company, Hindalco, is an India- based supplier of aluminium and copper.

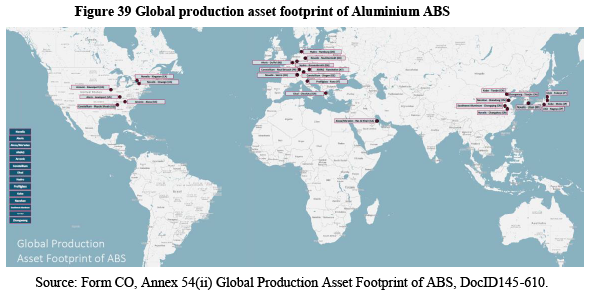

(3) Aleris is a global manufacturer of flat rolled aluminium products. Aleris operates 13 production facilities in North America, Europe and Asia.

2. THE OPERATION AND THE CONCENTRATION

(4) Pursuant to an agreement signed on 26 July 2018, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Novelis will merge into Aleris, with Aleris surviving the merger as a wholly-owned indirect subsidiary of Novelis.

(5) The operation thus constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

3. UNION DIMENSION

(6) The combined aggregate worldwide turnover of the Parties is more than EUR 5 000 million (Novelis […]5; Aleris […]) and the aggregate Union-wide turnover of each of the Parties is more than EUR 250 million (Novelis EUR […]6; Aleris EUR […]).7 Neither of the Parties achieve more than two-thirds of their Union-wide turnover within one and the same Union Member State.

(7) The Transaction therefore has a Union dimension pursuant to Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. THE PROCEDURE

(8) On 18 February 2019, the Notifying Party notified the Transaction to the Commission.

(9) During its initial (Phase I) investigation, the Commission reached out to a large number of market participants (mainly customers and competitors of the Parties), by requesting information through telephone calls and written requests for information pursuant to Article 11 of the Merger Regulation, including in the form of questionnaires.8

(10) In addition, the Commission sent several written requests for information to the Parties and reviewed internal documents of the Parties submitted at that stage.

(11) On 25 March 2019, based on its initial investigation, the Commission raised serious doubts as to the compatibility of the Transaction with the internal market and adopted a decision to initiate proceedings pursuant to Article 6(1)(c) of the Merger Regulation (the ‘Article 6(1)(c) Decision’).

(12) On 26 March 2019, the Commission provided non-confidential versions of certain key submissions of third parties collected during the Phase I investigation to the Notifying Party. On 28 March 2019, following a request from the Notifying Party, the Commission provided two further non-confidential versions of such submissions to the Notifying Party.

(13) On 4 April 2019, the Notifying Party submitted its written comments on the Article 6(1)(c) Decision (‘Reply to the Article 6(1)(c) Decision’).

(14) On 9 April 2019, following the Notifying Party's comments on the Article 6(1)(c) Decision, a State of Play meeting took place between the Commission and the Parties.

(15) On 11 April 2019, following a request from the Notifying Party, the time period set for the adoption of a final decision in relation to the Transaction pursuant to Article 10(3), first paragraph, of the Merger Regulation was extended by 20 working days pursuant to Article 10(3), second paragraph, of the same regulation.

(16) During its in-depth (Phase II) investigation, the Commission sent several requests for information to the Parties regarding various matters such as commercial strategy, capacity expansion plans and market data.

(17) In addition to collecting and analysing a substantial amount of information from the Parties (including internal documents and submissions), the Commission contacted a number of market participants (including customers and competitors of the Parties) and requested information from such third parties both through questionnaires9 pursuant to Article 11 of the Merger Regulation and telephone calls.

(18) On 13 May 2019, following the failure of the Parties to provide certain information it had requested pursuant to Art 11(2) of the Merger Regulation, the Commission adopted two decisions pursuant to Article 11(3) of the Merger Regulation, one addressed to the Notifying Party and another one to Aleris. The decisions requested the Parties to provide certain information as soon as possible and no later than 23 May 2019. Consequently, pursuant to Article 10(4) of the Merger Regulation and Article 9 of Commission Regulation No 802/200410 (‘Implementing Regulation’), the merger review time limit referred to in Article 10(3) of the Merger Regulation was suspended as from 7 May 2019, the working day following the date on which the Parties should have submitted complete responses to the relevant Art 11(2) requests for information. The referred time limit was suspended until 15 May 2019.

(19) On 20 June 2019 and following the results of the Phase II market investigation, a state of play meeting was held in order to inform the Notifying Party of the preliminary results of the Phase II market investigation and the scope of the preliminary concerns regarding which the Commission planned to issue a Statement of Objections.

(20) On 1 July 2019, the Commission adopted a Statement of Objections (‘SO’), which was sent to the Notifying Party on the same day. In the SO, the Commission set out the preliminary view that the Transaction would likely significantly impede effective competition in the internal market, within the meaning of Article 2 of the Merger Regulation, in relation to the production and supply of Aluminium ABS in the EEA due to (i) the creation or strengthening of a dominant market position in the relevant market; and (ii) horizontal non-coordinated effects resulting from the elimination of an important competitive constraint. The Commission’s preliminary conclusion was therefore that the notified concentration would be incompatible with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement.

(21) On 2 July 2019, the Notifying Party was granted access to the file. A data room was organised from 3 July to 9 July 2019 allowing the economic advisors of the Notifying Party to verify confidential information of a quantitative nature, which formed part of the Commission’s file. A non-confidential data room report (‘First Data Room Report’) was provided to the Notifying Party on 10 July 2019.11 The confidential report was taken to the Commission’s file on the same date.

(22) On 9 July 2019, the Notifying Party submitted an excel table identifying 286 passages from the file for which they requested less redacted versions. The Notifying Party was provided with replies of the Commission’s review of this request on 11 July 2019 (addressing 208 passages), 12 July (addressing further 26 passages), and 16 July 2019 (addressing further 39 passages). The reply concluding the Commission’s review and addressing the last 13 passages was provided to the Notifying Party on 17 July 2019. In the course of this review, 65 of the passages were completely or partially un-redacted.

(23) On 17 July 2019, the Notifying Party submitted their reply to the SO (the ‘Reply to the SO’).

(24) IG Metall and ABVV Metaal made an application to the Hearing Officer to be admitted as interested third persons in the proceedings, and they both were recognised as such by the Hearing Officer. They were provided with a non- confidential version of the SO. They both presented their views on the proposed Transaction at the oral hearing.

(25) On 23 July 2019, an oral hearing was held, upon request by the Notifying Party.

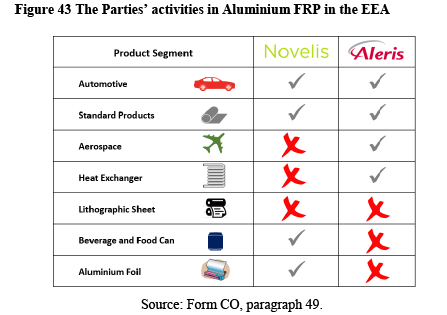

(26) On 26 July 2019, a state of play meeting was held, during which the Commission provided the Notifying Party with preliminary feedback following their Reply to the SO.

(27) The Notifying Party was granted subsequent access to the file on the same day.

(28) On 6 August 2019, a Letter of Facts setting forth evidence corroborating the objections set out in the SO – was sent to the Notifying Party. The Notifying Party submitted its comments on the Letter of Facts on 19 August 2019 (‘Reply to the Letter of Facts’).

(29) On 7 August 2019, the Notifying Party was granted subsequent access to the file. Another data room was organised from 8 August to 9 August 2019. A non- confidential data room report (Second Data Room Report) was provided to the Notifying Party on 12 August 2019.12 The confidential report was taken to the Commission’s file on the same date.

(30) On 9 August 2019, the Notifying Party submitted commitments pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO (the ‘Commitments of 9 August 2019’).

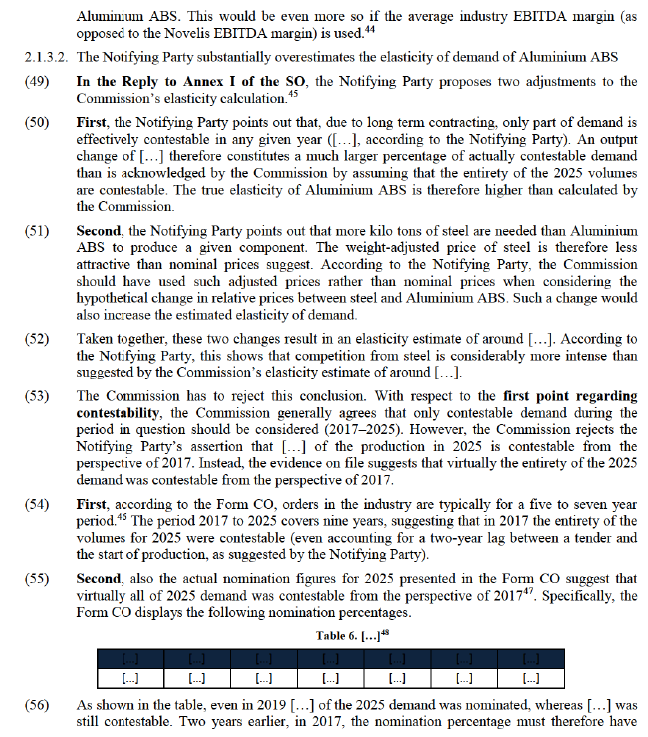

(31) On 13 August 2019, the Parties submitted revised commitments pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO (the ‘Commitments of 13 August 2019’).

(32) On 13 August 2019, the Commission launched a market test of the Commitments of 13 August 2019.

(33) On 2 September 2019, the Notifying Party was granted further access to file.

(34) On 3 September 2019, the Parties submitted revised commitments pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO (the ‘Final Commitments’).

(35) On 4 September 2019, the Commission sent a draft Article 8(2) decision to the Advisory Committee with the view of seeking the Committee’s opinion on it.

(36) The meeting of the Advisory Committee took place on 18 September 2019.

5. INTRODUCTION TO THE INDUSTRY AND PRODUCTS - ALUMINIUM FRPS

5.1. Production of metallic aluminium

(37) Aluminium is one of the most abundant elements in the Earth’s crust, and it is one of the most commonly used non-ferrous metals. Metallic aluminium13 can be produced either from aluminium-containing minerals (primary aluminium) or through recycling metallic aluminium (secondary aluminium).

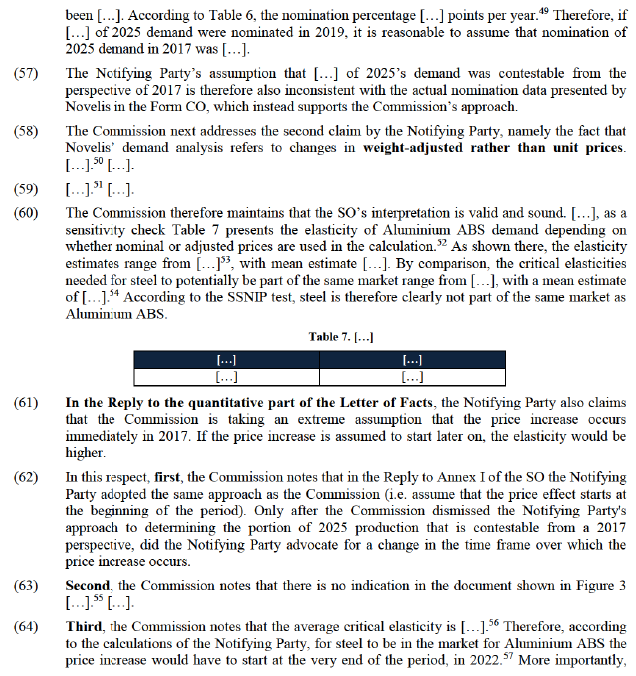

(38) Most primary aluminium is produced from an ore called bauxite. Bauxite is an ore rich in aluminium minerals. It is obtained through mining at various locations across the world. To produce primary aluminium, bauxite is first refined into alumina (aluminium oxide) using a multi-stage process. Subsequently, alumina is further processed in reduction plants forming pure aluminium through an electrolytic process called smelting.14

(39) Secondary aluminium is produced by re-melting and re-converting used aluminium products or scraps generated during the manufacturing process of aluminium products.

(40) Once primary or secondary aluminium (or a mixture of them) is molten, certain alloying elements can be added to obtain the desired characteristics. The liquid aluminium can thereafter be cast into various forms, such as: (i) ingots/T-bars, for re- melting purposes; (ii) extrusion billets, supplied to extruders to produce aluminium extrusions; (iii) slabs, which are typically used by rolling mills to produce aluminium flat rolled products (‘Aluminium FRPs’); (iv) wire rod, used to make aluminium wire for applications such as electricity transmission or in the steel industry as a deoxidising material; and (v) foundry alloys, supplied to foundries for use in the machinery, tool and automobile industries.

(41) The Transaction concerns the manufacture and supply of Aluminium FRPs. Aluminium FRPs are produced in rolling mills, typically from slabs of aluminium alloys. Other types of aluminium products, such as extrusions, are thus not discussed further in this Decision.

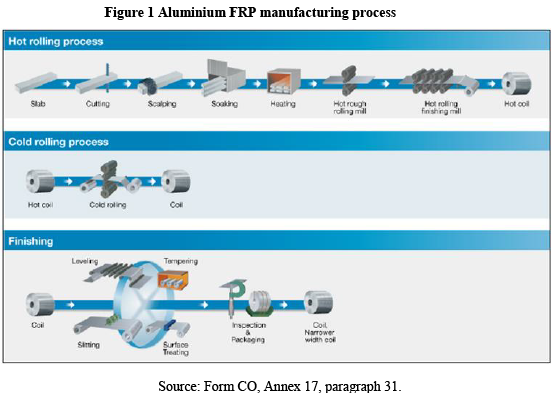

5.2. Aluminium FRPs

(42) The manufacturing of an Aluminium FRP starts with an aluminium slab, which is processed mainly in three steps (Figure 1): (i) hot rolling, which involves the heating of the slab in a furnace before it is rolled and that reduces the slab’s thickness to a certain desired thickness depending on the type of Aluminium FRP being produced; (ii) cold rolling, which further reduces the thickness; and (iii) finishing, which can include a number of treatments (heat treatments, surface treatments, etc.). Rolled aluminium coils can be sold as such by the producer, or they can be cut to desired length and width.

(43) Aluminium FRPs can be used for various different end-uses, such as beverage cans, food cans, aluminium foil, construction applications and automotive applications.

(44) The activities of the Parties overlap in the production and supply of (i) Aluminium FRPs used to produce vehicle bodies in the automotive industry, also known as Aluminium Automotive Body Sheets (‘Aluminium ABS’), and (ii) Aluminium FRPs used for certain other applications (so-called ‘Standard FRPs’), including in its potential sub-segments for aluminium anodising sheet and aluminium sheet for compound tubes (also known as multi-layer tubes).

(45) More details regarding the various types of Aluminium FRPs, including Aluminium ABS and Standard FRPs are provided in Section 6.1.

5.3. Aluminium ABS

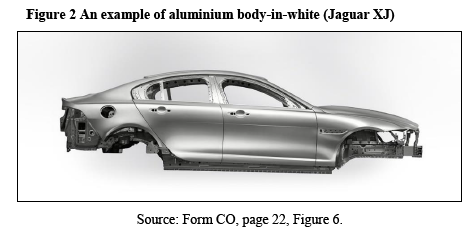

(46) Aluminium ABS are used in so-called body closures and in vehicles’ body structures. Body closures can be external or internal and include, for example, the bonnet (also called ‘hood’), doors, window frames, roof and boot of a car. The body structure is the core element of a car’s body. The car body connects all the different components; it houses the drivetrain as well as carries and protects the passengers.

(47) The so-called ‘body-in-white’ (‘BiW’) refers to the stage in automobile manufacturing in which the car body sheet material (including body closures and the body structure) has been assembled but before the components (such as engine, chassis, exterior and interior trim, seats and electronics) have been added to the body structure.

(48) Aluminium ABS (or ABS) is an expression commonly used in the automotive industry when referring to Aluminium FRP used for manufacturing the body-in- white.

(49) As explained in Section 5.1, certain alloying elements can be added to aluminium to achieve the desired characteristics of the final product. Depending on the main alloying element(s), certain alloy series can be distinguished. According to the Notifying Party, Aluminium ABS are almost exclusively made of the aluminium alloys series 5xxx and 6xxx.15

(50) 5xxx series (Al-Mg) are alloys in which magnesium is the principal alloying element. The 5xxx series are non-heat-treatable alloys. Alloys in this series possess moderate to high strength characteristics, as well as good weldablility and resistance to corrosion. 5xxx alloys are used for internal body closures (predominantly for the inner doors and inner bonnet) and for body structure applications.

(51) 6xxx series (Al-Mg-Si) are alloys in which magnesium and silicon are the principal alloying elements. The 6xxx series are versatile, heat treatable, highly formable, weldable and have moderately high strength coupled with excellent corrosion resistance. Due to heat-treatment by way of continuous annealing, the 6xxx series is stronger than the 5xxx series. 6xxx alloys are thus used for internal and external body closures (frequently for the bonnet, body side panels, wings and roof of a car) and for body structure applications.

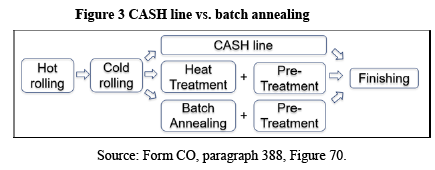

(52) There are two production steps for Aluminium ABS that are additional to the production steps required for all Aluminium FRPs (such as casting, rolling and finishing, as described in recitals (40) and (42) of this Decision): (i) continuous annealing or batch annealing and (ii) pre-treatment.

(53) Aluminium FRP suppliers wishing to produce Aluminium ABS at an existing FRP production line need to include either batch annealing or continuous annealing capabilities. Annealing is typically carried out after rolling and before finishing to adjust the material properties, in particular to increase the strength of the material.

(54) In the production of Aluminium ABS, the annealing typically takes place on a continuous annealing line, also known as Continuous Annealing Solution Heat Treating ('CASH') (the finishing line is also referred to as Continuous Annealing Line with Pre-Treatment (‘CALP’).

(55) Annealing in a CASH line (see Figure 3) is a continuous process during which coils are joined to enable a continuous ribbon of aluminium sheet to run through the finishing process. CASH is the main production method used in Aluminium ABS production and is required for the production of 6xxx series. A CASH line is an asset configured to combine the heat treatment and pre-treatment processes. It is nonetheless possible for these processes to exist in a disaggregated system too (see Figure 3).

(56) The production of 5xxx series is at least to a certain extent possible using batch annealing. During the batch annealing process, the aluminium coils remain separate while they are heated, in batches, in specific furnaces to strengthen the material before passing through a pre-treatment line (see Figure 3).16 However, the production of 5xxx series through batch annealing is an option much less pursued in the industry as customers of Aluminium ABS typically prefer or even require continuous annealing treatment, due to possible quality issues.17 Further, the Parties in their internal considerations of market capacity regularly consider CASH line capacity as the relevant metric. Quality issues and the Parties’ internal consideration of capacity is further discussed in recitals (580) to (584) .

(57) A CASH line can interchangeably produce both 5xxx and 6xxx series. Nonetheless, there are certain differences between the production of 5xxx and 6xxx series in CASH lines. 6xxx series need to undergo additional procedures during production, and may therefore need to run through a CASH line more than one time, which leads to slower production compared to 5xxx series. 6xxx series also exhibit higher scrap rates during production.

(58) Conversely, there are certain similarities in the production of 6xxx alloys used for the exterior (‘6xxx-skin’) and 6xxx alloys used for the interior (‘6xxx structure’). Both 6xxx series run through the production line at a similar speed. One difference is that 6xxx-skin series have a higher scrap rate than 6xxx structure series during the production process. The production of 6xxx-skin series must ensure that all surface defects are removed. 6xxx–skin’s surface quality is also rougher, which requires more lubrication during production compared to 6xxx structure series. Despite these differences, 6xxx-skin and 6xxx structure series are produced with the same equipment. 5xxx alloys are only used for manufacturing non-visible vehicle components.

5.4. Procurement of Aluminium ABS

(59) The procurement of Aluminium ABS usually takes place through requests for quotations (‘RFQs’) and bidding procedures organised by automotive original equipment manufacturers (‘OEMs’). Sales of Aluminium ABS are also made to tier components suppliers that process Aluminium ABS for OEMs (‘Tier suppliers’) and to a smaller extent to distributors.

(60) Tier suppliers are those customers of Aluminium ABS manufacturers that apply further manufacturing steps on Aluminium ABS and sell the resulting products to OEMs.18

(61) The development and production of a vehicle by an OEM includes a number of subsequent steps from designing to actual production.19

(62) An OEM typically decides on the use of Aluminium ABS in a vehicle platform during the so-called design stage, which can start about five years before the start of production. At this stage, the OEM designs the vehicle according to various commercial, legislative, technical and industrial requirements.

(63) After the design stage, an OEM typically organises a bidding process and issues formal RFQs specifying the parts, alloys, and volumes desired and asking its qualified Aluminium ABS suppliers to quote.

(64) The Notifying Party has explained that whilst each OEM has a different purchasing strategy, OEMs usually organise separate tenders for each vehicle model. OEMs tend to split different components among suppliers after a tendering process. However, in some cases, OEMs may group parts together. This would for example take the form of grouping more attractive higher volume parts together with less attractive lower volume parts to ensure balance. Depending on their preferences, some OEMs may prefer to source certain components from the same supplier, whereas others may prefer to have more than one supplier for a given component.20

(65) In response to an RFQ, suppliers prepare and submit their offers. They typically offer a separate price quote for each component of the tender unless the OEM groups parts together.21

(66) European OEMs typically qualify several Aluminium ABS suppliers22 for each part or group of parts of the vehicle and issue RFQs to qualified suppliers only.23 A competitor explains that ‘[e]xclusive suppliers do still exist but to a limited extent as OEM[s] want to secure supply chain by qualifying multiple ABS producers’.24 Similarly, a customer explains that ‘the Company tries to avoid being too dependent from one supplier, and tries to balance the sources’.25

(67) Qualification or homologation of an Aluminium ABS supplier and of its products is a process that aims at ensuring that each Aluminium ABS product offered by a supplier in a tender meets certain desired technical characteristics.26 The qualification process of a certain product is valid only for a specific process route in a plant (specific hot rolling line, cold rolling line and CASH line)27 and may take up to 2 years, or, in some cases, longer. The qualification of the suppliers, which is additional to product qualifications, ensures that certain criteria in terms of, for example, financial stability and supply reliability are met by each supplier.

(68) However, the qualification of a supplier and of its products does not guarantee that a certain manufacturer will be chosen as a supplier. An OEM28 explained that, in selecting the supplier, ‘in addition to the price, the Company also considers other important factors related to the potential suppliers, including: their financial health, their strategy, their manufacturing capabilities and capacities’. And that ‘the Company considers the suppliers’ future available capacities, i.e. the capacities available when the aluminium FRP are expected to be manufactured and needed for the production of the respective vehicle’. Supply capacity, which in the present case is closely linked and can be approximated to CASH capacity,29 is a key requirement for Aluminium ABS suppliers to be able to compete for a customer. There is no point in competing in a given tender if an Aluminium ABS supplier has no capacity available to supply the customer.

(69) The tender process can involve a number of rounds of bidding and take some months to conclude. During a tender process, customers may provide feedback to Aluminium ABS suppliers on the price level they expect. Suppliers may then decide to discount their offer accordingly.30 The final decision is normally made no later than two years before the start of vehicle production. After the final round of offers, the OEM evaluates the bids received and nominates the selected supplier(s).

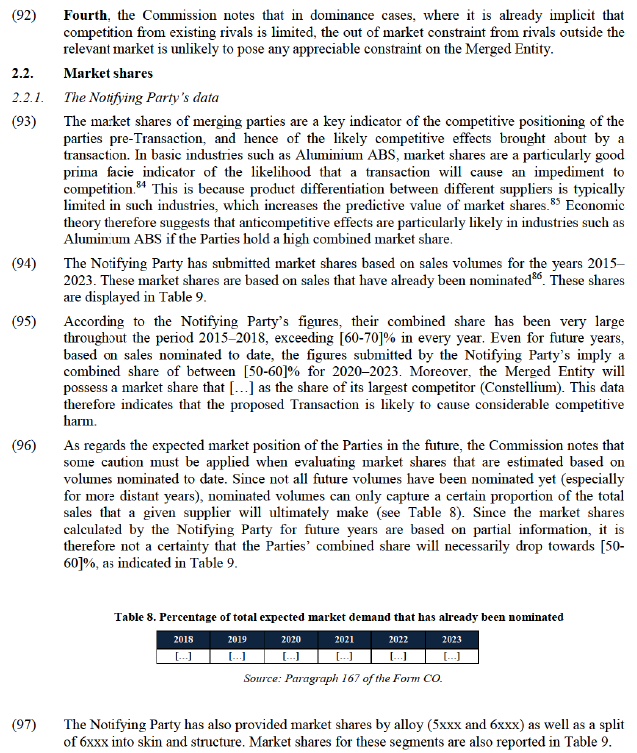

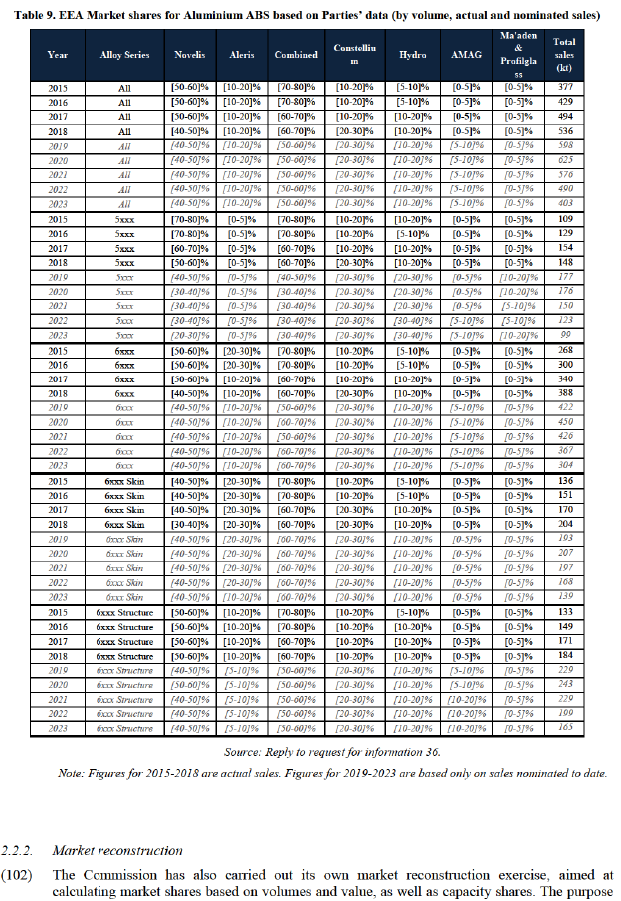

(70) Once the vehicle model is fully designed and prepared, it can be launched and put to series production. The total duration of the production run can vary but can typically be 5 to 7 years.

(71) The commercial relationship between the OEM and the winning Aluminium ABS supplier can be governed either by a specific supply agreement signed post tender or by the terms and conditions set out by both parties during the tender procedure. For example, […].31

(72) Typically, following an agreement, the Aluminium ABS supplier would deliver based on periodical purchase orders sent by the OEM.32 […].33

(73) Quantity deviations from the long-term strategic planning are possible. […].34

(74) Prices are typically composed by the London Metal Exchange (LME) price for primary aluminium,35 conversion revenues36 and other price components (related to, for example, metal freight to the supplier’s casting plant, transport to the OEM’s or the Tier supplier’s press shop, etc).

(75) The agreement between the OEM and the winning supplier typically specifies the conversion prices for the lifetime of a vehicle program, but further adjustments are not excluded.

(76) Supply agreements typically run for the estimated production run of the vehicle model. The termination of an agreement before the end of the agreed term or before the end of the renewal period can be possible in certain circumstances. However, if one of the parties terminates an agreement before it lapses, it can be obliged to compensate the other party. In the event of termination of a purchase order, OEMs can be liable for costs related to work in progress and raw materials acquired.37

(77) Agreements often include so called […] .38 […].39

(78) Supplies to Tier suppliers can take place on terms negotiated between an OEM and the Aluminium ABS supplier. However, Aluminium ABS suppliers and Tier suppliers also negotiate agreements independently from OEMs.40 According to the Parties, […].41 According to a competitor, ‘[t]o deliver ABS to Tier-suppliers the material also has to be qualified by the OEM’, therefore, ‘the Tier-supplier can purchase ABS only from a list of suppliers approved by the OEM’.42 Several Tier suppliers have confirmed that they receive Aluminium ABS only from suppliers that have been previously qualified by the OEM.43

(79) Agreements between Aluminium ABS and Tier suppliers are usually signed for a period of one to two years.44

(80) Aluminium ABS suppliers can also sell their Aluminium ABS to distributors. According to a competitor, ‘[t]oday some distributors also focus on automotive and are able to distribute all kind of automotive parts whereas skin and closures are the most demanding ones’ and ‘[a]n OEM typically decides to use distributors and purchase from them if the purchased quantity is below a certain amount’.45

5.5. Trends and industry requirements in Aluminium ABS

(81) Aluminium use in passenger cars has been growing over the past years. The amount of aluminium in an average car has increased from 50 kg in 1990 to about 150 kg today.46 Despite this, steel remains by far the most prevalent material in passenger cars.

(82) As explained by the Notifying Party, the increased use of aluminium has primarily been driven by more demanding carbon dioxide (CO2) emission standards worldwide. To meet these emission targets, OEMs are required to develop vehicles that are more fuel-efficient. The use of lighter materials, such as aluminium, plays an important role in this effort because it helps reduce the weight of the vehicle and thereby fuel consumption and CO2 emissions.47 This is generally referred to as ‘light weighting’ in the automotive industry.

(83) Therefore, as acknowledged by the Notifying Party, price is only one of many dimensions of competition between Aluminium ABS and steel. Aluminium has certain technical advantages over steel, such as its strength-to-weight ratio. Nevertheless, using steel has other advantages, including lower cost.48

(84) A customer explained that ‘[r]easons for the choice of aluminium are mainly light- weighting and, consequently, reduction of CO2-emissions as well as fuel consumption’.49 Another customer50 explained that ‘[u]sing aluminium ABS results in costs that are 2 to 3 times higher than by using steel ABS’ and that ‘[t]he choice of aluminium ABS is therefore not driven by costs, but by weight reduction requirements’. The same company considers ‘the reduction in the weight of cars as a means to comply with stricter CO2 emissions regulation’.

(85) The Notifying Party itself expects the overall aluminium content per vehicle to grow in the future.51

Figure 4 […]

[…]

(86) In the EEA, the growth of aluminium content in vehicles is driven by new CO2 emissions performance requirements for new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles in order to contribute to achieving the EU’s target of reducing its greenhouse gas emissions and the objectives of the Paris Agreement.52

(87) Union legislation sets mandatory emission reduction targets for new cars since 2009.53

(88) The 2009 Regulation on CO2 emissions standards establishes a target of 130 g CO2/km that applies since 2015 for the EU fleet-wide average emission of new passenger cars. In 2017, the average emissions level of the new cars registered in the EU was 118.5 g CO2/km. Since 2010, average emissions have decreased by 22 g CO2/km (15.5%).54

(89) From 1 January 2020, Union standards set an EU fleet-wide target of 95 g CO2/km for the average emissions of new passenger cars and an EU fleet-wide target of 147 g CO2/km for the average emissions of new light commercial vehicles registered in the EU. Stricter EU fleet-wide targets will apply from 1 January 2025.55 Therefore, the new EU standards set an EU fleet-wide target from 1 January 2020 that will be 35 g lower than the one that applies currently. As the Notifying Party explained,56 these CO2 emission targets are adjusted to the average weight of each OEM’s fleet. In particular, the heavier the fleet of an OEM, the less stringent the target. Nevertheless, although different targets apply to different OEMs, all of them have to comply with stricter and stricter CO2 emission limits.

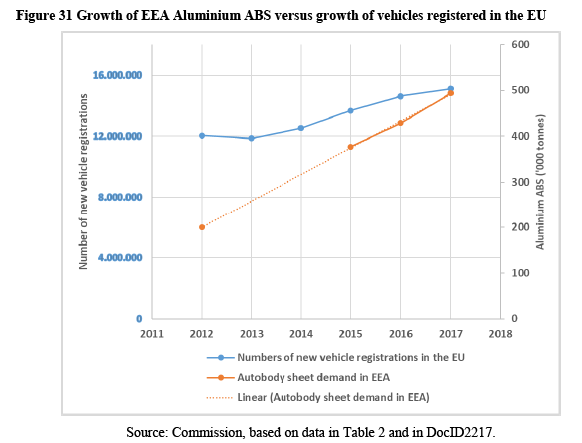

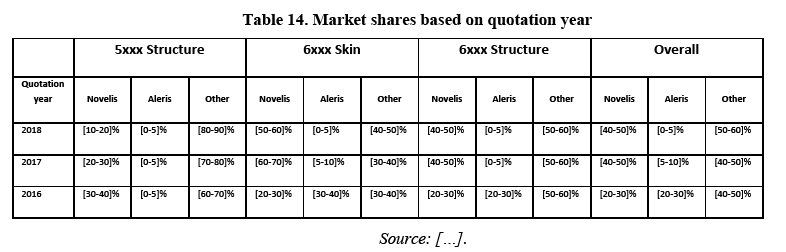

(90) OEMs and competitors also expect Aluminium ABS demand to grow in the future because of stringent emission policies that incentivise the production of lighter cars.57 In this regard, one customer said that ‘[a]luminium is the material to choose in order to comply with the European policies to reduce fuel consumption, CO2 emissions’.58 Another customer explained that ‘the demand for aluminium ABS is forecasted to increase because the Company and most (if not all) of its OEM competitors are expected to increase aluminium ABS demand in the years to come, due to CO2 emission regulations’.59 A competitor said that demand for Aluminium ABS ‘is increasing by up to two-digit figure annually’ and that ‘[t]he growth is expected to continue in the short to medium term, due to the need to light-weight cars and lower their fuel consumption.’60 The same competitor explained that the increase in the demand of Aluminium ABS ‘is not driven by increasing total car production but rather driven by switching to aluminium from steel in car production especially by hang on parts (which are more stiffness driven than strength driven) for which there is – due to stiffness requirements - a physical thickness limit on steel’.

(91) In addition to the EEA, other jurisdictions such as the US and China are increasingly tightening fuel efficiency standards in response to increasing environmental problems. In the case of China, current standards are less strict than, for example, in the EEA, but future stricter standards respond, among other factors, to a heavy reliance on overseas energy and urban traffic congestion.61

Figure 5 […]

[…]

6. RELEVANT PRODUCT MARKETS

6.1. Categories of Aluminium FRPs

(92) Aluminium FRPs are a group of flat aluminium products that are used for a multitude of different applications. In previous decisions, the Commission has concluded that not all Aluminium FRPs belong to the same relevant product market due to supply- and demand-side considerations. In particular, the Commission has concluded that Aluminium FRPs used for certain applications constitute distinct product markets. These include: (i) beverage can bodies; (ii) beverage can ends; (iii) food cans; (iv) lithographic sheet; (v) aluminium foil; and (vi) automotive sheet62,63 In addition, the Commission has considered that Aluminium FRPs used for a number of other applications, such as for aerospace, may constitute distinct product markets but has left the question ultimately open.64

(93) Further, the Commission has concluded in previous decisions that a distinct product market exists for Standard FRPs. That market has been considered to include all Aluminium FRPs that do not constitute separate products markets (see recital (92)).65

(94) The present Decision concerns Aluminium ABS, which are used in the automotive industry to produce the BiW (see Section 5.3) and Standard FRPs, including its potential sub-segments aluminium anodising sheet and aluminium sheet for compound tubes.

6.2. Aluminium ABS

6.2.1. Aluminium ABS belongs to a market separate from other Aluminium FRPs

6.2.1.1. The Notifying Party’s view

(95) The Notifying Party submits that Aluminium ABS belongs to a relevant product market separate from other Aluminium FRPs.66

6.2.1.2. The Commission’s assessment

(96) The results of the market investigation do not call into question the previous practice discussed in Section 6.1 and the Notifying Party’s submission that Aluminium ABS belongs to a market separate from other Aluminium FRPs. Supply- and demand-side substitutability between Aluminium ABS and other types of Aluminium FRPs appear limited.

(97) From a supply-side perspective, the production of Aluminium ABS requires special equipment and knowhow compared to other types of Aluminium FRPs, as already explained in Section 5.3. In particular, the production of Aluminium ABS requires (i) (continuous) annealing and (ii) pre-treatment of the coil, which are additional steps to the other production steps (such as casting and rolling) needed for the production of all Aluminium FRPs.67

(98) Furthermore, the pattern of supply is different between Aluminium ABS and other Aluminium FRPs. In this respect, the Commission observes that only certain Aluminium FRP manufacturers also supply Aluminium ABS. For example, there are a number of manufacturers that compete with the Parties for more common types of Aluminium FRPs,68 but only few of them, namely Constellium, Hydro, AMAG, and, to some extent Profilglass and Alcoa/Ma’aden69 also manufacture Aluminium ABS (see Section 8.3.5).

(99) From a demand-side perspective, the results of the market investigation indicate that automotive OEMs and their Tier suppliers, which are also customers of the Parties, cannot substitute Aluminium ABS with other Aluminium FRP developed for other purposes. The specific requirements of automotive OEMs relate to, for example, the strength, formability as well as surface quality and finishing of the product. All these properties are typically specified by each OEM, and Aluminium ABS manufacturers need to develop specific products or customise their previously developed products for addressing these technical specifications.70 Both OEMs and Aluminium ABS manufacturers will have to undergo a lengthy series of tests (the so-called ‘homologation’ or ‘qualification’ process of a product and production chain), where OEMs ensure that the products conform to their specifications.71

(100) Finally, the Commission observes that Aluminium ABS suppliers such as the Parties are able to identify automotive customers and separate them from customer groups requiring other Aluminium FRPs, such as for example those active in aerospace, in construction and in other industrial segments.

(101) The manifest differences between these various customer groups are also reflected in the organisational structure of Aluminium ABS manufacturers. In the case of Novelis and Aleris, for example, each of them have dedicated business divisions within their industrial groups, which are dedicated exclusively to serving automotive customers with Aluminium ABS. […].72 None of these business divisions appear to be serving any other customer groups.

(102) The Commission further notes that trade between customer groups (that is, for example, between customers active in aerospace, or in automotive) and arbitrage by third parties is likely hampered by the customers’ specific requirements. Specific requirements exist for the products they source, as well as for the suppliers they source them from, and a strict qualification process is associated to the products supply chains, as well as to the suppliers (see recital (99)). This supports the Aluminium ABS suppliers’ ability to treat automotive customers as a distinct customer group.

6.2.1.3. Conclusion

(103) For the reasons set out in this Section 6.2 and considering all evidence available to it, the Commission concludes that Aluminium ABS belong to a relevant product market separate from other types of Aluminium FRPs.

6.2.2. Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies belong to different markets

6.2.2.1. The Notifying Party’s view

(104) The Notifying Party submits that Aluminium ABS and steel products for similar automotive applications are substitutable and compete with each other and, hence, together constitute a single product market.73

(105) The Notifying Party argues that the definition of one single product market for both Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies would be consistent with a Commission’s precedent, and would be justified by the competition that takes place during the design stage of a vehicle between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies. In particular, the Notifying Party disagrees with the Commission’s findings that CO2 emission regulations are the main drivers for OEMs to choose Aluminium ABS, and considers that such a choice is also the result of price competition between Aluminium ABS and steel products.74 According to the Notifying Party, the price difference between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies does not preclude price competition, because Aluminium ABS compete with steel products based on the ‘cost per kg- saved’.75

(106) The Notifying Party also submits that employing Aluminium ABS is only one of the alternatives that OEMs may pursue for reducing CO2 emissions. According to the Notifying Party, OEMs can reach their CO2 emission targets by using measures that are alternative to light-weighting in a vehicle body, and, in case they decide to lightweight the BiWs of their vehicles, weight reduction can also be achieved by using modern steel products76 or other aluminium products, such as extruded or cast products.77 In support of this argument, the Notifying Party provides two examples showing that comparable vehicle weights can be achieved with different levels of Aluminium ABS contents.78

(107) The Notifying Party also submits that the Commission’s SSNIP test is flawed and that on proper construction, it does not support the finding that Aluminium ABS belongs to a different product market than steel products for the same applications.79

(108) As regards the argument that there would be customer groups different from automotive OEMs which may not be able to switch to steel products, the Notifying Party submits that Tier suppliers and distributors do not generate demand for Aluminium ABS because OEMs negotiate with Aluminium ABS suppliers on their behalf, and therefore any potential demand-side substitutability related to these customers is not relevant.

(109) In support of its argument that Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies belong to the same product market, the Notifying Party provides examples of vehicle parts that were previously manufactured using Aluminium ABS, and in more recent versions of the same vehicles are manufactured using steel products instead,80 as well as examples of benchmark exercises that Aluminium ABS manufacturers make versus steel products and vice-versa.81

6.2.2.2. The Commission’s precedents

(110) In the early Alcan/Pechiney (II) case, which is from 2003, the Commission noted that Aluminium ABS was ‘a new, nascent application’. While the Commission considered that Aluminium ABS and respective flat steel products seemed to – ‘for the time being’ – belong to the same relevant product market, 82 it nonetheless left the question open and assessed the effects of the remedy in that case on a pure Aluminium ABS market excluding steel products.83

(111) For completeness, in the recent Tata Steel/ThyssenKrupp/JV case, the Commission concluded that aluminium products do not belong to the same relevant product market with automotive hot-dip galvanised steel, the type of steel predominantly used in the construction of vehicle bodies.84

6.2.2.3. The Commission’s assessment

(112) For the following reasons, the Commission considers that, contrary to the Notifying Party's submission, Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies are not in the same relevant product market. Overall, steel and aluminium have different physical and commercial characteristics. There is no supply-side substitutability and demand-side substitutability is limited at most.

(6.2.2.3.1) The definition of separate product markets for Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies is not inconsistent with the Commission’s precedent

(113) In Alcan/Pechiney (II) the Commission stated that ‘for the time being’ – that is in 2003 – aluminium and steel ABS ‘seem[ed] to’ belong to the same relevant product market, but it did not reach a definitive conclusion on this, and ultimately left the product market definition open.

(114) In Alcan/Pechiney (II), the Commission concluded that ‘[…] even if automotive aluminium sheet were to constitute a separate product market, any competition problems would be solved by the remedies offered by Alcan in relation to other FRPs product markets’.85 Therefore, in that specific context, the Commission did not initiate proceedings pursuant to Article 6(1)(c) of the Merger Regulation and therefore did not have the opportunity to conduct an in-depth (Phase II) investigation of the market for Aluminium FRP.

(115) Moreover, as explained in Section 5.5, since 2003 substantial changes in the market conditions occurred, in terms of, for example, CO2 emission regulations and the related drivers for OEMs to employ Aluminium ABS. Therefore, the Commission’s findings in the present case are not inconsistent with the findings in Alcan/Pechiney (II), if the different market conditions are taken into account.

(116) With respect to the recent Tata Steel/ThyssenKrupp/JV decision, the Notifying Party points out that it has no insight into the arguments and evidence proffered in that decision.86 The Commission notes in this respect that the findings in the present case are not based on evidence obtained in case M.8713 – TataSteel/ThyssenKrupp/JV. The Commission merely notes, for completeness, that, as indicated in the public press release, the Commission deemed that a market for automotive hot-dip galvanised steel was a distinct one, and that the press release makes no reference to an overall automotive body sheet market that would consist of both steel and aluminium. To that effect, the Commission recalls that the press release titled ‘Mergers: Commission prohibits proposed merger between Tata Steel and ThyssenKrupp’ states that ‘[t]he Commission had serious concerns that the transaction as notified would have resulted in a reduced choice in suppliers and higher prices for European customers of […] automotive hot dip galvanised steel products, where the proposed merger would have eliminated an important competitor in a market where only a few suppliers can offer significant volumes of this steel’.87

(6.2.2.3.2) Aluminium ABS and the respective steel products are characterised by different conditions of supply and by a lack of supply-side substitutability

(117) The Commission observes that there is no supply-side substitutability between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies, and that the patterns of supply and conditions of competition are in general different.

(118) First, steel and aluminium are different metals, they have different physical characteristics and they require different equipment to manufacture at all stages of the production chain. Equipment used to produce either Aluminium ABS or flat steel products used in automotive bodies cannot thus be used to produce the other product.

(119) Second, patterns of supply between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies are different. In this respect, the Commission notes that, for example, the Parties manufacture and supply Aluminium ABS in the EEA, but neither of them manufactures or supplies flat steel products used in automotive bodies. The same is true for the main competitors of the Parties, namely Constellium, AMAG,88 and Hydro,89 as well as for recent entrants Alcoa/Ma’den90 and Profilglass.91

(120) As to steel, the type of steel predominantly used in the production of vehicles is (hot- dip galvanised) flat carbon steel. The main manufacturers and suppliers of that type of steel in the EEA include for example ArcelorMittal, ThyssenKrupp, Tata Steel, Voestalpine, Salzgitter and SSAB.92 None of these companies manufactures Aluminium ABS. […].

(121) Third, the Commission observes that the Parties' […] regularly benchmark themselves in particular against other Aluminium ABS suppliers. […].93 […].94 […],95 […].

(122) […];96 […].97

(123) […].

Figure 6 […]

[…]

(124) Fourth, Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies are subject to very different trade defence instruments (‘TDIs’) affecting imports.98

(125) Currently, safeguard measures99 apply to 28 categories of steel products, including flat steel products for automotive applications, to limit the increase of imports to a level that is unlikely to cause serious injury to the European Union industry while ensuring that traditional trade flows are maintained and existing user and importing industry sufficiently supported.100 As also stressed in the recitals to the relevant safeguard measures regulation,101 these safeguard measures have been adopted due to the adoption of safeguard measures by other countries outside the EEA.

(126) Furthermore, definitive anti-dumping measures102 are imposed amongst others on certain corrosion resistant steel products originating from China, including hot-dip galvanised flat carbon steel used for automotive applications.103

(127) With regard to aluminium, definitive anti-dumping measures are currently imposed on certain aluminium foils104 and certain aluminium road wheels.105 However, there are no safeguard or anti-dumping measures currently affecting Aluminium ABS in particular. Although safeguard measures have been adopted by some countries outside the EEA with regard to certain aluminium products (as for certain steel products), the Commission has not currently imposed any safeguard measures on Aluminium ABS.

(128) Contrarily to the Notifying Party’s argument that TDIs are not relevant in terms of supply-side substitution because the relevant geographic market for the production and supply of Aluminium ABS is the EEA,106 the fact that imports of Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies are subject to different TDIs suggests that the supply conditions in the EEA are also different. In particular, this confirms that also when assessing demand and supply conditions in view of potential reactions to external shocks in the supply of these products from outside the EEA, TDIs are targeted specifically at each of these product groups and no knock-on effects are expected.

(6.2.2.3.3) Demand-side: distinction between design- and production phase of a vehicle model

(129) While the Notifying Party mainly alleges demand-side substitutability on automotive applications for steel and aluminium, it is apparent that the alleged possibility of technically replacing parts made from two different materials does not result in finding that those two materials belong to the same relevant product market.

(130) In this respect, the Commission observes that two different situations need to be distinguished: (i) switching materials during the production phase of a vehicle model and (ii) switching materials during the design phase of a vehicle model.

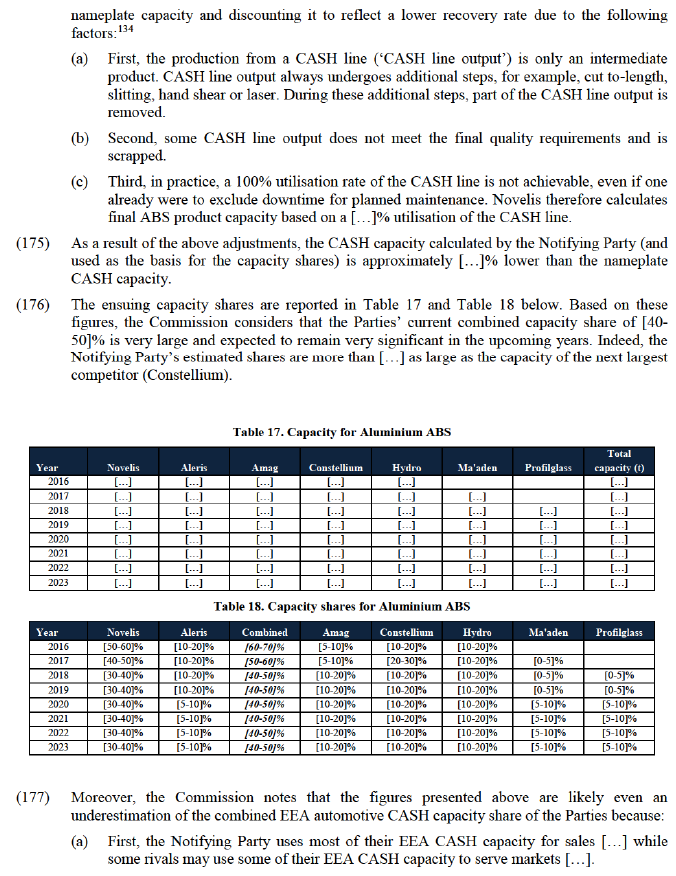

(6.2.2.3.4) Demand-side: No substitutability during production phase

(131) As to switching materials during the production phase of a vehicle model, the results of the market investigation show that switching is in practice usually not possible or at least very difficult and costly. In practice, car manufacturers cannot substitute aluminium and steel during a car model’s production cycle (typically approximately 5–7 years).107 This relates to the fact that a vehicle model is designed with a particular material in mind and switching the material would often require both the re-design and re-testing of the vehicle, including crash tests depending on the component in question, as well as reworking vehicle production.

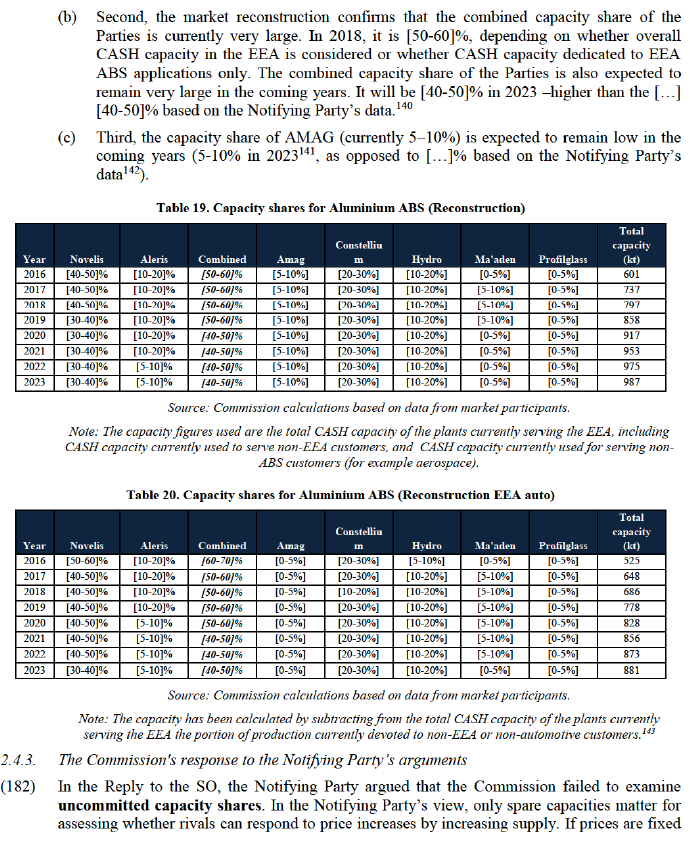

(132) To this effect, the clear majority of automotive customers responding to the market investigations stated that their ability to substitute Aluminium ABS for other materials during the production phase is at best ‘very limited’.108

(133) A major OEM explains: ‘A switch from a material to another (i.e. switching from aluminium to steel) has to be made before certification of the carline (e.g. crash, WLTP…) - - Switch between materials can happen during facelifts for design purpose mainly because a material offers more shaping flexibility. Any switch in material would also be hampered by the fact that the crash certification would have to be retaken’.109 That same OEM further clarifies that it ‘does not intend to switch back to steel after a price increase for aluminium ABS’. Another OEM further explains that during the production phase, a ‘change from aluminium to steel would mean major investment in the press shop (new dies), body shop (joining technology) and others. In addition it would not be possible anymore to implement closed-loop activities for aluminium which means an negative impact on product sustainability’.110 A major automotive OEM concurs: ‘Switching materials becomes very costly after the stamping tools have been manufactured and is only undertaken in exceptional circumstances.’111

(134) In practice, switching from Aluminium ABS to flat steel products used in automotive bodies and vice versa is a long-term decision that is taken at the design stage way before a tender procedure to source the material is launched. An OEM explains that a ‘change of the chosen material is easier during the engineering phase. Nevertheless, there is still some flexibility for switching before the start of production'.112

(135) For automotive manufacturers who are planning upcoming tenders that would be nominated in the next few years, the engineering has already been done and even if the production cycle has not started yet, it is thus unlikely that they can seamlessly switch from Aluminium ABS to flat steel products used in automotive bodies.

(136) The Notifying Party claims that the lack of demand-side substitutability at production phase is not relevant because prices for Aluminium ABS are defined before the production phase, and are fixed through a price formula that remains unchanged during the entire production phase.113 However, although Aluminium ABS prices cannot be increased during production phase, in principle, they could be reduced (see Sections 5.4, recital ). Therefore, contrarily to the Notifying Party’s claim, the lack of demand-side substitutability between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies at production phase is relevant for the purpose of defining a relevant product market for the production and supply of Aluminium ABS.

(6.2.2.3.5) Demand-side: Potential substitutability during design phase does not warrant finding of a combined market for Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies

(137) Based on the results of the market investigation and the submissions of the Notifying Party, switching between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies is in principle possible during the design-phase of a vehicle. However, the Commission finds that such a possibility is not sufficient to substantiate a finding of a single product market for these materials, and that also in the design phase customers’ ability to switch is limited, even in the event of a price increase of aluminium ABS compared to steel products used in automotive bodies.

(138) First, the choice of employing Aluminium ABS instead of flat steel products used in automotive bodies is mainly driven by the need to comply with CO2 regulations, rather than their relative prices.

(139) An OEM typically chooses to employ Aluminium ABS for reducing the overall weight of its vehicles, and, ultimately to comply with CO2 emission regulations.114 As explained in Section 5.5, reducing the weight of a vehicle has the benefit of reducing its fuel consumption, and, consequently, the benefit of reducing its CO2 emissions. When aggregated for all the vehicles sold by a given OEM in the EEA, the reduction in average CO2 emissions allows that OEM to comply with CO2 emission regulations. […].115

(140) OEM respondents to the market investigation provided extensive evidence that the choice of employing Aluminium ABS is driven primarily by CO2 regulations. An OEM states that ‘[a]luminium is definitely lighter than steel, this supports the CO2 lightweight strategy’116. Elaborating further, the OEM says that ‘[t]he choice of aluminium ABS is […] not driven by costs, but by weight reduction requirements. The Company considers the reduction in the weight of cars as a means to comply with stricter emissions regulation'.117 Another OEM mentions that ‘[a]luminium is more and more used in our vehicles to shave off kilograms (light weighting), necessary to meet upcoming regulations’118 and further that ‘most of the time the choice of aluminium is highly related to CO2 concern’.119 Another major Aluminium ABS customer explains why Aluminium ABS is a material of choice with it being a ‘[w]eight saving driven decision’.120 Putting it straight forward, another OEM states that ‘aluminium is needed to meet CO2 emission targets’121 and that ‘[t]he demand of aluminium ABS is driven by the move in the industry to reduce emission by reducing car weight’.122 Another OEM also states that the ‘growth in aluminium FRP usage can be attributed to the light weighting need as well as increasing electrification, both in order to comply with the regulatory emissions limits’.123 A further OEM explains that ‘[l]ightweight is important because [the company] has to fulfil legislative requirements with regard to CO2-emissions and fuel consumption, and reducing the weight of a vehicle is major way for achieving these targets’.124 Phrasing it in clear terms, another OEM says that ‘[a]luminium is the material to choose in order to comply with the European policies to reduce fuel consumption, CO2 emissions'.125

(141) The Parties’ competitors seem to share the same view regarding the motivation of an OEM to choose Aluminium ABS over flat steel products used in automotive bodies. One of the Parties’ competitors, for example, in one of its earning calls stated that ‘[…] the increased aluminium usage is a secular trend for these markets. Aluminium’s favourable strength to weight ratio in comparison to steel, enable’s OEMs to lightweight vehicles, thereby increasing fuel efficiency and reducing CO2 and other emissions. Aluminium, also a superior energy absorption properties as compared to steel […]’.126 Another competitor to the Parties further states that ‘[t]he demand for aluminium ABS will further increase also because of the goal to reduce CO2 emissions and to further lightweight cars’ and further that ‘[i]n Europe, regulation drives the increased use of aluminium in the automotive sector to reduce weight and lower emissions’.127

(142) A Novelis’ internal document […],128 […].

Figure 7 […]

[…]

(143) Furthermore, the Notifying Party itself has publicly highlighted the importance of CO2 regulation for the adoption of Aluminium ABS. To this effect, the Vice President Automotive of Novelis Europe, Michael Hahne, explains in an industry publication Automotive World (May 2018) that ‘with CO2 emission standards set to tighten worldwide, it’s safe to say the main driver [for the increased use of aluminium] today is regulation’. He also highlights Europe as the region with the most stringent rules, as it ‘has set a target of 95 grams CO2 per kilometre by 2020’.129

(144) […].

Figure 8 […]

[…]

Source: Reply to request for information 18, ‘NOV-EU00292913.docx’, DocID1022-35912.

(145) In line with CO2 emission regulations being the main factor behind the choice of Aluminium ABS over flat steel products used in automotive bodies, OEMs seem to be adapting the quantity of Aluminium ABS (as opposed to cheaper steel) in the vehicle models they supply according to the CO2 emission regulations in place in the regions where the vehicles are to be sold.

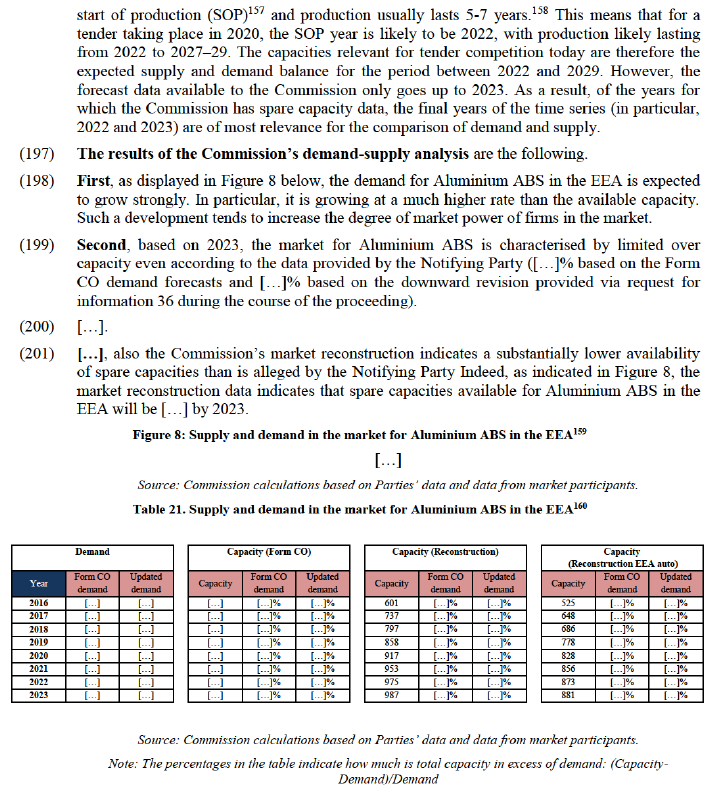

(146) […].

Figure 9 […]

[…]

(147) […].

Figure 10 […]

[…]

(148) […]130 […]131 […].

(149) […].132 […].

(150) Another example of the influence of regulation on the adoption of Aluminium ABS is provided by […] releasing in 2014 its […] vehicle in the EU market and in the United States market with wings,133 doors, bonnet,134 roof and boot135 lid made of aluminium.136 The same car model does not have these components made of aluminium when produced for the Chinese market,137 where CO2 regulation is less stringent than in the EEA and in the United States.138

(151) In the Reply to the SO, the Notifying Party questions the correlation between CO2 emission regulations and Aluminium ABS demand. This is because, according to the Notifying Party, CO2 emission regulations apply equally to all OEMs, but some OEMs use in their fleets a much larger share of Aluminium ABS, compared to others.139 In support of its argument, the Notifying Party provided a graph representing, for each OEM active in the EEA, its Aluminium ABS purchasing share as well as the number of vehicles that each OEM produces every year.140

(152) However, the Commission finds that the evidence offered in rebuttal, on a proper construction, is instead consistent with its own arguments, as it demonstrates that OEMs which are more important customers of aluminium ABS are the ones more exposed to regulatory requirements (as they produce and sell heavier and therefore more CO2-emitting vehicles). Moreover, evidence from the files indicates that, in view of ever more tightening regulatory requirements, also the other OEMs expect that their consumption of Aluminium ABS will have to substantially increase in the near future in order to be able to comply with such requirements.

(153) […]. Although the emission regulation applies on the basis of the entire fleet, and not at individual vehicle level, as already explained in the SO,141 OEMs typically use more Aluminium ABS for manufacturing premium-segment vehicles, such as large saloons and SUVs mainly because i) there is a more pronounced need to reduce weight in these vehicle categories, and therefore more CO2 saving benefits; and ii) the higher prices of these vehicles allow to afford the increased cost of Aluminium, compared to steel. This is well-explained by an OEM that stated ‘in lower vehicle segments (for example, segments A, B and, to some extent, C), the share of aluminium is expected to be lower than in higher segments, as for example segments D and above. This trend is also related to the size itself of a vehicle: higher segments would lead to an excessive weight if the share of aluminium is modest, whereas smaller vehicles can be realised with less shares of aluminium’.142

(154) Concerning the Notifying Party’s argument that Figure 11 does not explain why different OEMs focusing on high-end vehicles consume different amounts of Aluminium ABS,143 the Commission refers to recitals (175)-(176), which explain why different options for reducing CO2 emissions are not equally available to all the OEMs, and therefore each of them decides to use different amounts of Aluminium ABS.

Figure 11 […]

[…]

Source: Reply to the SO, Figure 1.

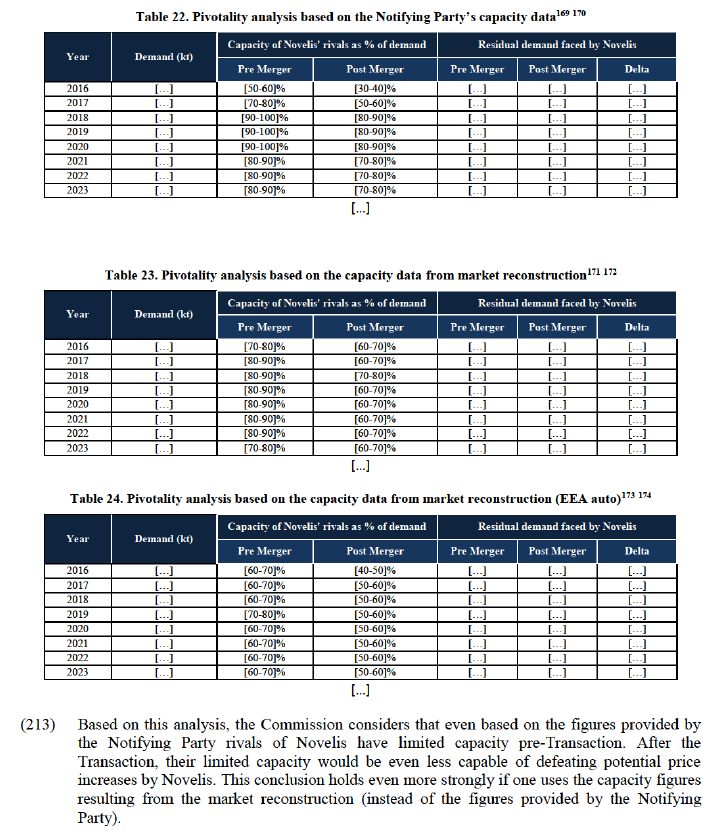

(155) A document produced by a consultant for Novelis […].

Figure 12 […]

[…]

(156) In the second place, CO2 emission regulations are expected to become even stricter in the near future. As explained in Section 5.5, as of 1 January 2020 the limit for EU fleet-wide average emission of new passenger cars will be reduced by about 27% from the current regulation (i.e. from the current 130 g CO2/km to 95 g CO2/km).

(157) In view of this, and consistent with the Commission’s analysis, also the OEMs that typically produce a higher number of smaller vehicles (that is, for example, PSA, Fiat and Renault-Nissan) and now consume a relatively smaller share of Aluminium ABS compared to flat steel products for automotive bodies, are expected to increase the share of Aluminium ABS also in vehicles of small size. An OEM that responded to the market investigation stated ‘[t]raditionally the Company has used aluminium predominantly for vehicles of large segments, however, it is now also using it for the [small segment car model] and in the near future also smaller car segments (B segment) will have hoods made from aluminium ABS’.144 Another OEM indicated that ‘at the moment [emphasis added], aluminium is mainly used in closures for premium vehicles’,145 thus alluding to the fact that in the future also non-premium vehicles will contain more aluminium. Another OEM that to a large extent produces small- and medium-size vehicles stated that ‘[t]he Company is currently using approximately 10 – 15 kg of aluminium per vehicle on average. The next generation of the Company´s “[vehicle name]” will contain approximately 100 kg of aluminium per vehicle. The increased usage of aluminium is a general trend among OEMs because aluminium is one of the best candidates for securing light weighting’.146 147

(158) An internal document of Novelis […].

Figure 13 […]

[…]

(159) In the Reply to the Letter of Facts, the Notifying Party argues that light-weighting is an inferior way for OEMs to reduce CO2 emissions, compared to other technologies. The Notifying Party observes that, according to the EU CO2 emission regulation, the CO2 emission target of each OEM is adjusted to the average weight of its fleet in a way that OEMs producing heavier vehicles have less stringent CO2 emission targets. As a consequence, if an OEM reduces the weight of its fleet as a consequence of light-weighting, also the CO2 emission target becomes more stringent, therefore it is more incentivised to find alternative technologies for reducing CO2, while maintaining the same average weight.148

(160) However the claim of the Notifying Party, in essence, does not question the need of OEMs to reduce the weight of their fleets for meeting their obligations in terms of emission limits. The Notifying Party’s claim regards only how effective weight reduction is, and does not question the fact that limited or, often no alternative solution is available to OEMs. As explained in recital (173), the availability of alternative technologies for reducing CO2 emissions is rather limited and, in most cases, require a longer time-frame and additional costs, compared to lightweighting. Consistently, the majority of OEMs that replied to the market investigation consider that alternative technologies either would not be cost-effective or would not be timely available.

(161) In addition to considerations related to CO2 emissions and light-weighting in combustion engine vehicles, regulatory pressure to reduce CO2 seems to drive the adoption of Aluminium ABS adoption in a further, indirect way.

(162) Electric vehicles (‘EVs’) are a vehicle category that avoids the CO2 emissions of traditional vehicles with internal combustion engines. Therefore, one might consider that the penetration of EVs into the automotive market might reduce the need for OEMs to reduce the emissions of their traditional combustion vehicles, and consequently reduce their need to employ Aluminium ABS. […].149 […].150 […]151 […]152,153 […].154

(163) The Notifying Party claims that the influence that EVs are expected to have on the Aluminium ABS demand is unclear because, […]155, […].156

(164) In the Reply to the SO, the Notifying Party submitted a document […].157 […].

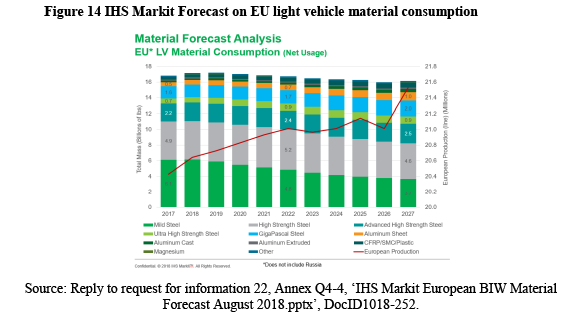

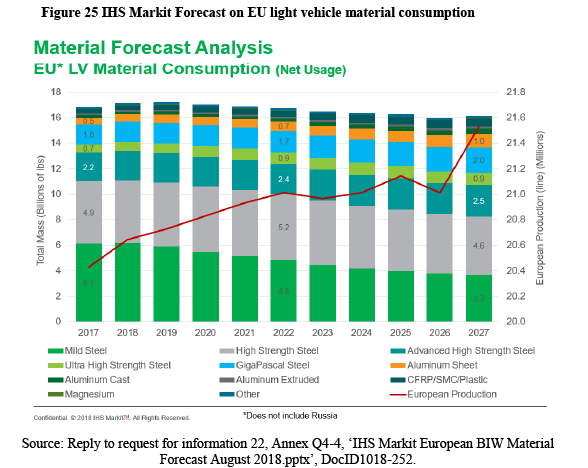

(165) Further evidence that a growing share of electric vehicles does not result in less demand for lightweight materials such as Aluminium ABS, is also included in third- party reports and studies on the matter. A McKinsey report states that ‘[w]hile share of lightweight materials could further decrease in BEVs, overall demand for lightweight could further increase until 2030’ and indicates a positive ‘[l]ightweight material demand’ trend for hybrid vehicles.158 The report also summarises that overall the trend to electrification will not reduce the demand for lightweight materials by stating that ‘[e]xpected increase of lightweight materials share and demand by 2030, driven though their use in ICEs and hybrids’, while also seeing a ‘[l]ikely decline of lightweight materials for BEVs in the next years, along with declining battery prices and increasing battery density’. In addition, and despite the foreseen electrification trend, material demand forecasts by third party providers continue to project Aluminium ABS content in cars and Aluminium ABS demand to increase. This is for example evidenced in the IHS Markit Forecast from August 2018, captioned in Figure 14 (see aluminium sheet’s growing figure), and the Notifying Party’s own projections as detailed, for example, in Figure 15.

(166) The Ducker report ‘Aluminium Content in European Cars’ from June 2019 also states that ‘Extrusions and sheet will win shares by 2025, mainly driven by Electrification components and Body Closures’ and further that ‘[e]lectrification components, Body Closures and Body Structure are expected to be the main growth areas by 2025’.159 While electrification components may be either made out of Aluminium ABS or other aluminium products (such as extruded products), this assessment shows that the aluminium content of Closures (very high share of Aluminium ABS), Structure (considerable share of Aluminium ABS) and electrification components (Aluminium ABS used for example in battery cases) are all expected to increase.

(167) Despite cost considerations, there are other reasons why OEMs are expected to continue to prefer, to some extent, Aluminium ABS in the future. […].160

(168) […],161 and this appears to be consistent with the expectations of many market participants, suggesting that EVs will contribute to the increase in demand for Aluminium ABS.

(169) An OEM explains that ‘[g]reater adoption of fully electric car platforms for example could see higher usage of aluminium ABS at the [Company’s group] generally’.162 Another major OEM ‘considers that aluminium ABS demand will increase due to more stringent emissions regulations, and to more widespread production of electric vehicles’.163 Another OEM ascribes the foreseen increase in Aluminium ABS demand to ‘the light weighting need as well as increasing electrification’.164 In anticipating potential own increased needs for Aluminium ABS, another OEM mentions ‘the proliferation of electric cars and the tendency to cleaner policies that incentive [sic] lighter cars’.165 Similarly, a competitor mentions that ‘[w]ith technology changing away from petrol-powered towards hybrid, all-electric or hydrogen powered cars, the demand of aluminium ABS from OEMs will increase.’166

(170) In addition to regulation compliance, OEMs’ decision to reduce the weight of their vehicles through Aluminium ABS leads to additional benefits, which include engine downsizing (which is translated into reduced costs and reduced fuel consumption and CO2 emissions), vehicle performance improvements, and, in some cases, specific design optimisations.167

(171) […].

Figure 15 […]

[…]

(172) Second, while the Notifying Party submits that alternative methods to light- weighting in the BiW exist for automotive OEMs to reach their emission targets, the results of the market investigation do not support a finding that such alternative methods are always easily available, or that they can immediately replace Aluminium ABS as the means of choice to reduce a vehicle’s weight.

(173) In the first place, the results of the market investigation suggest that OEMs are not able to pursue alternatives to the usage of Aluminium ABS for complying with CO2 emission regulations in a timely manner and without major additional costs. That is to say that OEMs are generally unable to ‘achieve their CO2 regulatory targets with steel’,168 by pursuing options for reducing CO2 emissions that are alternative to Aluminium ABS.

(174) The clear majority of the OEMs that expressed their view in the response to the market investigation consider that today’s benefits of Aluminium ABS in terms of fuel consumption and CO2 emissions cannot be replaced in a timely manner and without major additional costs by other alternatives, as for example, by improving the engine efficiency, by electrification, by improving aerodynamics and rolling resistance, etc.169 An OEM explains in this respect that ‘no economically viable material alternative to aluminium is available to OEMs for reducing its vehicles’ weight. Composite materials, for example, a too expensive option, while high strength steel can replace aluminium only to a limited extent’.170

(175) In the Reply to the SO, the Notifying Party compares two car models using little or no Aluminium ABS […] .171 According to the Notifying Party, this is a proof that OEMs do not require Aluminium ABS to achieve their weight saving targets, and, more in general, to comply with CO2 emission regulations. Similar claims are also made by the Notifying Party in its Reply to the Letter of Facts.172

(176) […].

Figure 16 […]

[…]

(177) Further, in achieving its CO2 emission target, an OEM might have strategic decisions leading to rely on Aluminium ABS more heavily for some vehicle models, and less for other models. […].

(178) […].173 […].

Figure 17 […]

[…]

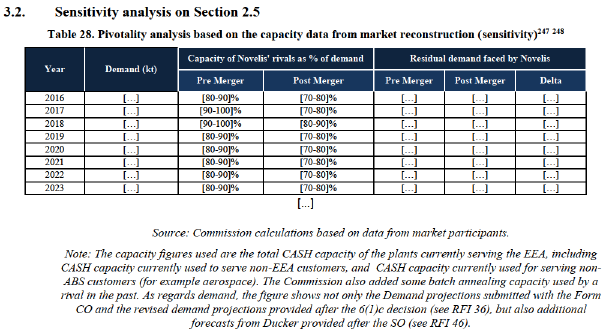

(179) The Notifying Party argued that Aluminium ABS accounts for only a fraction of the total aluminium content in a car, and therefore other aluminium products, such as extruded and casted aluminium products, represent additional alternatives to OEMs for reducing the weight of their vehicles.174 […]175 […].

(180) […].176

Figure 18 […]

[…]

(181) More generally, contrarily to the Notifying Party’s claim,177 a future stricter CO2 emission regulation is likely to increase the rigidity of demand for Aluminium ABS178 and does not necessarily make alternative ways for reducing CO2 emissions more attractive to them.

(182) Further, while certain automotive OEMs have exploited for instance diesel engine technologies in an effort to reduce CO2 emissions, such technology has recently suffered setbacks due to the discoveries related to high NOx emissions. In an internal document, Novelis considers this as an opportunity, as ‘[d]iesel scrutiny increase[s] pressure to explore other means to reduce CO2 (e.g. lightweight)’.179

(183) Third, even if other technical means to achieve reductions of CO2 emissions in vehicles existed, they would not necessarily determine that Aluminium ABS would be immediately substitutable with steel to the extent that they would belong to the same relevant product market.

(184) In the first place, as a matter of reasoning, the argument of the Notifying Party is not that of an immediate and direct substitution between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies. In particular, the Notifying Party seems to acknowledge that, even in the event of an increase of the price of Aluminium ABS, the likelihood of OEMs switching to flat steel products for automotive bodies would be dependent on their possibility to find alternative technical means to reduce CO2 emissions.180 The availability of these alternatives would have to be assessed on a case-by-case basis, and, in most cases such an availability appears to be very limited. A large majority of the OEMs that responded to the market investigation consider that ‘[…] all potential alternatives [for reducing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions] either would not be sufficient, or will require major additional investments and time’.181

(185) […].182 […].

(186) However, nothwistanding the lack of availaible technologies explained in recital (184), the claim of the Notifying Party suggests that Aluminium ABS would not be in competition with flat steel products for automotive bodies, but rather with alternative technologies that are needed to achieve CO2 emission reduction, while maintaining the vehicles’ weight. Therefore, the substitutability of Aluminium ABS for flat steel products for automotive bodies would not be a result of a change in their comparative price, other things being equal, but it would be contingent on the availability and comparative cost of other alternatives for reducing CO2 emissions.

(187) In the second place, the need to find alternatives in a vehicle design in order to offset a price increase in aluminium by sourcing steel is also, on a proper construction, evidence of a limited demand-side substitutability rather than an argument supporting the ease of switch by customers.

(188) Fourth, consistently with the considerations in recitals (129) to (187) and as documented in Annex I – which is an integral part of the Decision – Section 2.1.1, there are significant price differences between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies, with Aluminium ABS being around […] than steel based on total price according to the Commission’s calculations based on data from the Notifying Party.183

(189) The difference in prices remains very large even after adjusting for differences in densities between the two materials: after adjusting for a light-weighting factor reflecting the fact that aluminium has a lower density than steel and therefore less aluminium is needed compared to steel to produce a given component, the adjusted price of Aluminium ABS is still […]% more expensive than flat steel products for automotive bodies. 184

(190) Even so, purchasers of Aluminium ABS have in the past shown a willingness to pay such significant premium because of the significant benefits (in terms of compliance with CO2 emissions regulations) brought about by aluminium’s material properties. This is consistent with the observation that switching between flat steel products for automotive bodies and Aluminium ABS is not predominantly driven by small but significant changes in relative prices, but by more structural properties of demand (including the desire to meet CO2 emission regulations).

(191) Contrarily to the Notifying Party’s claim that Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies compete on price based on the kg-saved,185 the price difference indicates that OEMs are willing to pay a higher price for Aluminium ABS because their employment is an effective way for complying with CO2 emission regulations. Therefore, this price difference between Aluminium ABS and flat steel products used in automotive bodies does not support a finding of them belonging to the same relevant product market. While the market investigation suggests that the cost for an OEM of using Aluminium ABS instead of flat steel products used in automotive bodies (including high-strength steels) varies across different vehicle models and components, the price difference appears to be always significant.

(192) According to the Notifying Party’s own explanation,186 aluminium, as a metal, is up to about […] lighter than steel per the same volume (that is, it is […] less dense). Nonetheless, for certain applications, different amounts of material may be needed in order to achieve certain desired material properties (comparatively more aluminium may be needed in order to achieve the same strength as steel, or in order to undergo similar manufacturing processes). These factors altogether lead to weight saving by using Aluminium ABS rather than steel products that varies across different vehicle components and typically amount to about […]% weight saving for structural parts, […]% weight saving for doors, and […]% for bonnets (Figure 19).

Figure 19 […]

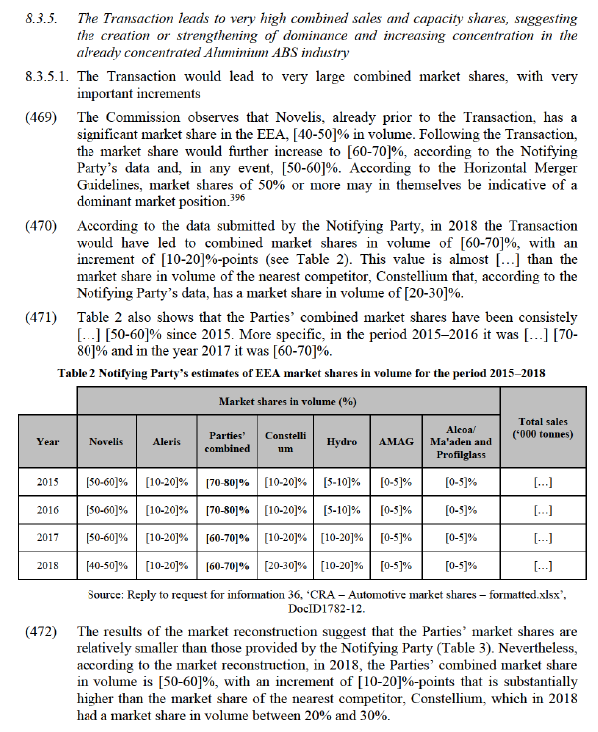

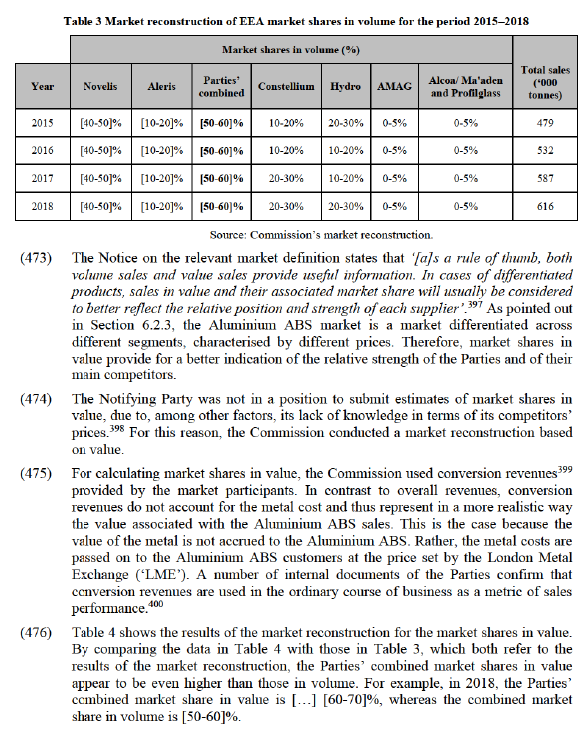

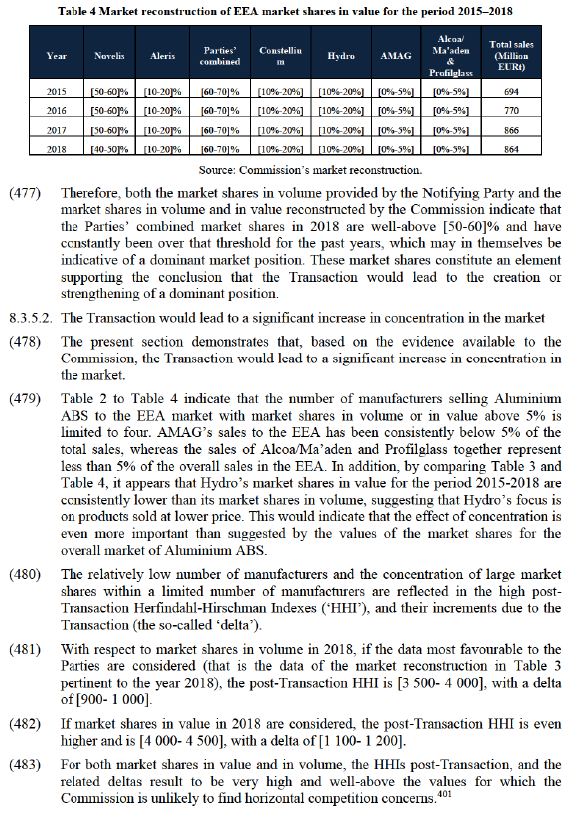

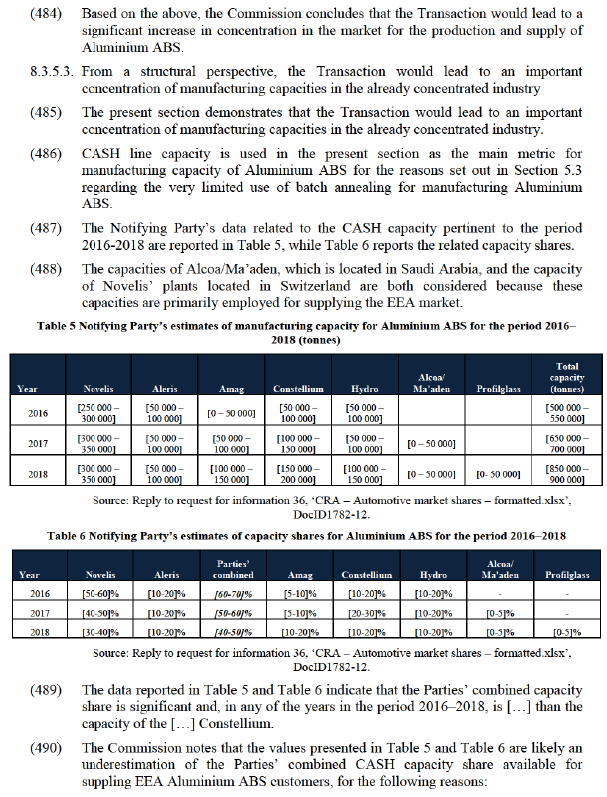

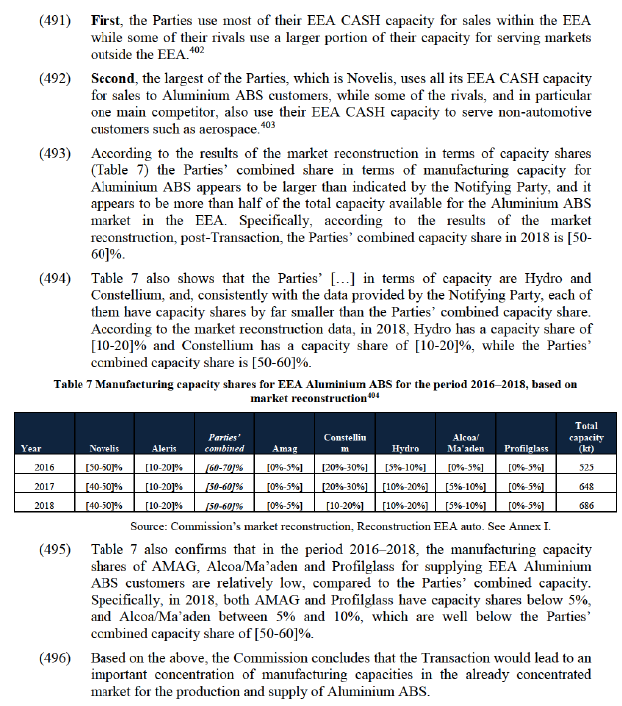

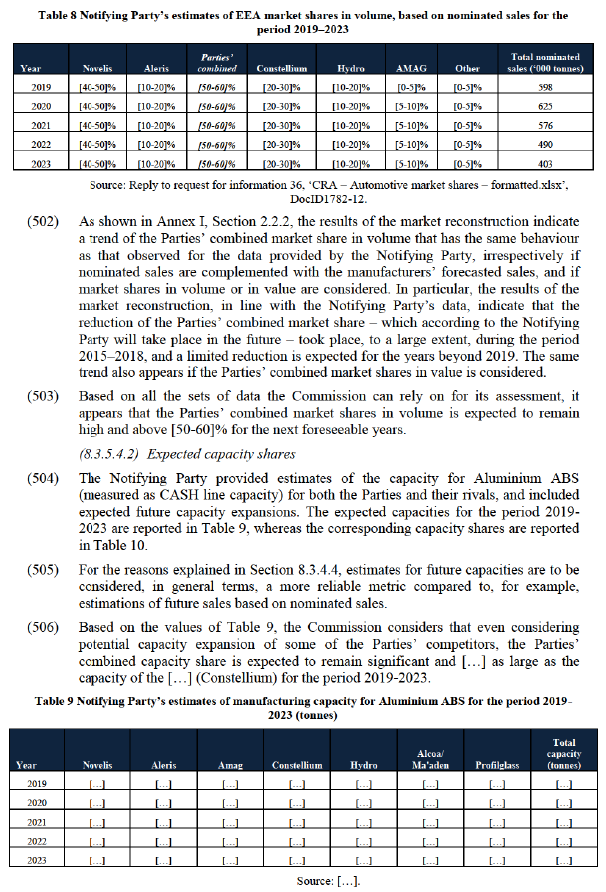

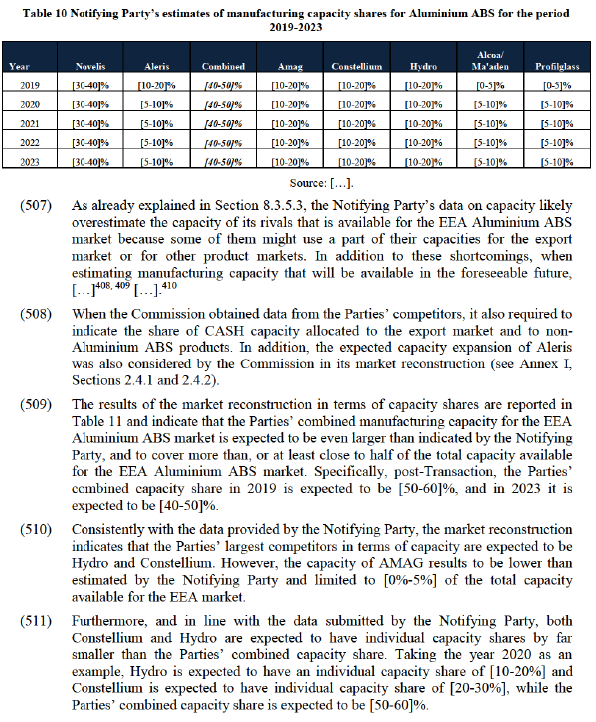

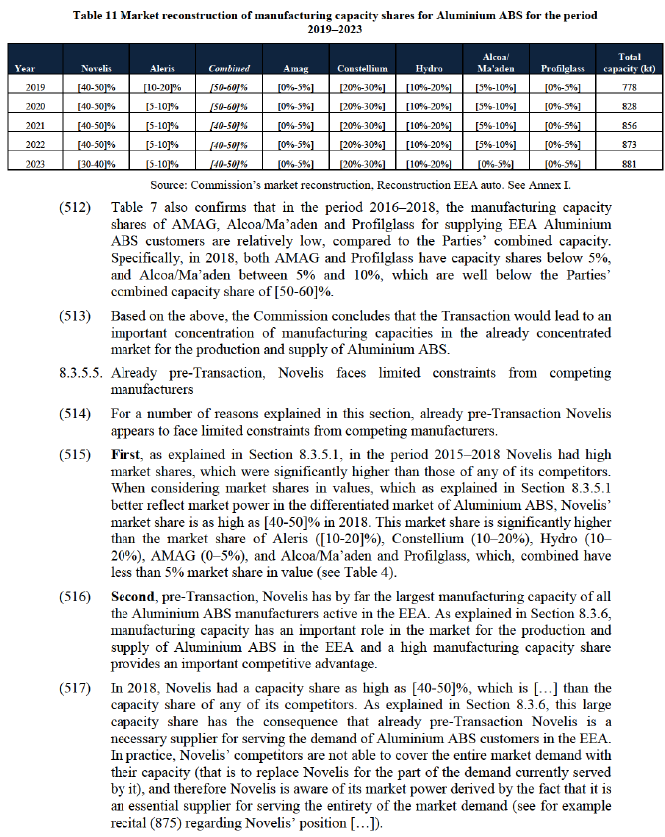

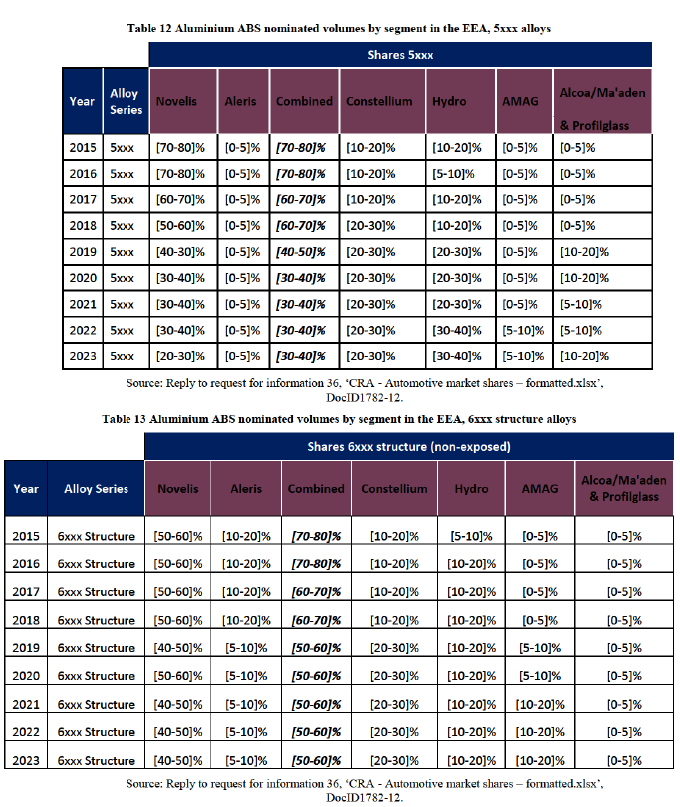

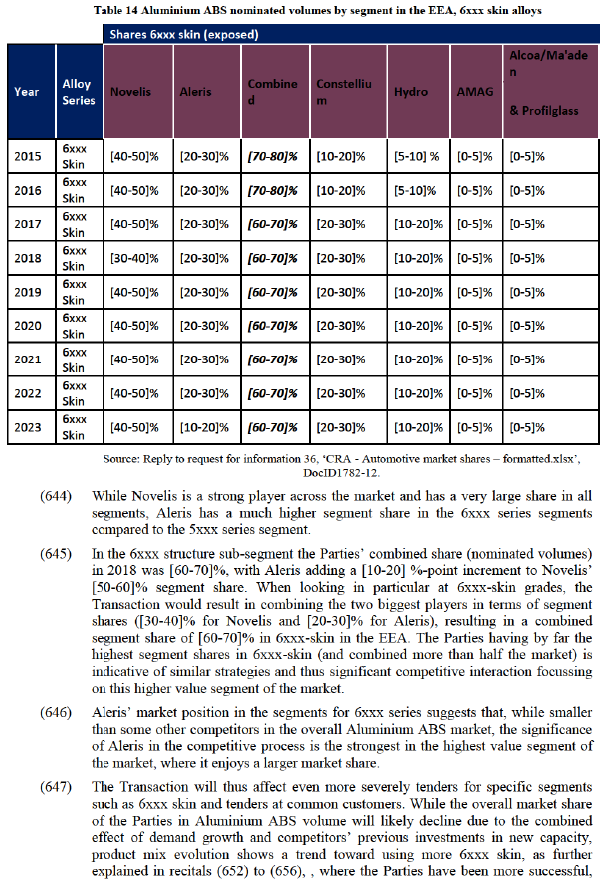

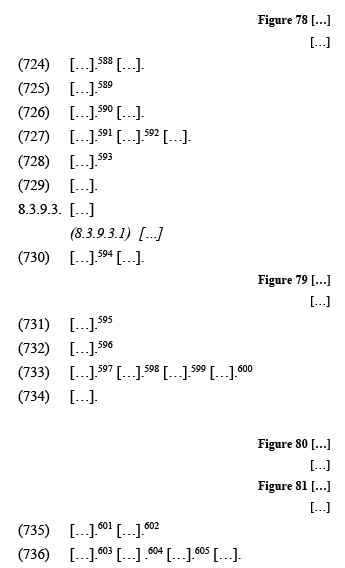

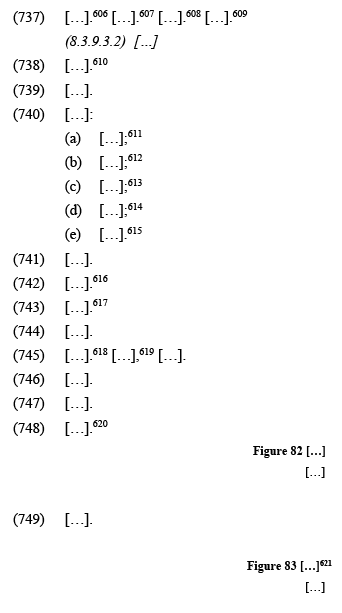

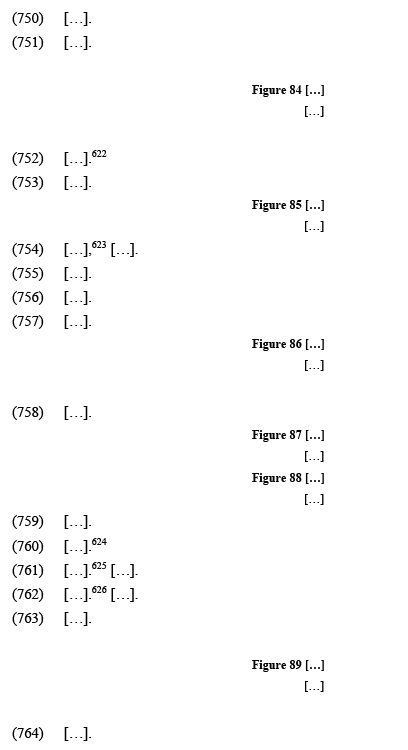

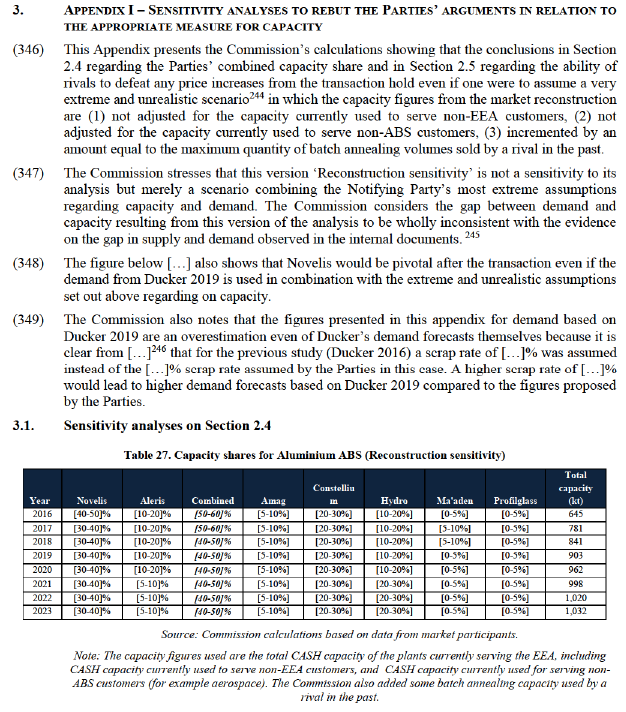

[…]