Commission, October 2, 2017, No 39813

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

Baltic rail

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union1,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty2, and in particular Article 7 and Article 23(2) thereof,

Having regard to Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 of 7 April 2004 relating to the conduct of proceedings by the Commission pursuant to Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty,3

Having regard to the complaint lodged by AB ORLEN Lietuva on 14 July 2010, alleging infringements of Article 102 of the Treaty by AB Lietuvos geležinkeliai and requesting the Commission to put an end to that infringement,

Having regard to the Commission Decision of 6 March 2013 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given AB Lietuvos geležinkeliai the opportunity to make known its views on the objections raised by the Commission pursuant to Article 27(1) of Regulation No 1/2003 and Article 12 of Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004,

After consulting the Advisory Committee on Restrictive Practices and Dominant Positions, Having regard to the final report of the Hearing Officer in this case,

Whereas:

1. INTRODUCTION

(1) On 2 September 2008, the Lithuanian railway undertaking and infrastructure manager, AB Lietuvos geležinkeliai ("LG"), allegedly detected a deformation on a 40 metre long segment ("Deformation") of a railway track running from Mažeikiai in Lithuania to the border with Latvia ("the Track") used for the transport of refined oil products from the refinery of AB ORLEN Lietuva ("OL") in Bugeniai, Lithuania ("the Refinery") to Latvia. All rail freight traffic on the Track was immediately suspended and in the following month LG removed the entire 19 kilometres of the Track.

(2) The Commission considers that LG has abused its dominant position on the Lithuanian market for the management of railway infrastructure by removing the entire 19 kilometres of the Track in the legal and factual circumstances described below, thereby making the shortest and most direct route from the Refinery to the Latvian border unavailable to its competitors in the downstream market for the provision of rail transport services for oil products to the seaports of Klaipėda, Riga and Ventspils. This gave rise to potential anti-competitive effects of foreclosing competition on that market by raising entry barriers without an objective justification. The abuse started with the removal of the Track and it is on-going.

2. PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS

2.1. The addressee of the decision

(3) The undertaking addressed by this Decision is LG, a state-owned and vertically- integrated railway company that operates both as the railway infrastructure manager and as a provider of rail transport services in Lithuania. The shareholders' rights in LG are exercised by the Ministry of Transport. The Lithuanian state owns the railway infrastructure in Lithuania and LG has the legal monopoly to manage it (see recital (127)). LG is also the sole provider of rail transport services in Lithuania.

(4) LG has three divisions within the same legal entity, namely: freight, passenger and infrastructure divisions. LG also has seven subsidiary companies, whose core activities include rolling stock repairs/manufacturing, security/cleaning services, track repairs and construction, railway design and research work, waste and protective greenery management, rail turnout manufacturing and shareholding.4 As the manager of the railway infrastructure, LG performs all necessary repairs and construction works to the railway infrastructure and is responsible for the safety of that infrastructure.

(5) In 2016, LG's total revenues were EUR 409.5 million with the complainant's rail transport business accounting for EUR [40-80] million, approximately [10-20]% of LG's turnover in that year.5

2.2. The complainant

(6) The complaint was submitted by OL, a company registered in the Republic of Lithuania, having its office at Juodeikiai village in the Mažeikiai district. Up to September 2009 the name of the company was AB Mažeikių nafta. OL is engaged in the refining of crude oil, as well as in the wholesale and, to a much lesser extent, the retail sale of oil products, predominantly in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Poland.

(7) OL owns and runs several facilities in Lithuania, with significant assets including the Refinery (the only refinery in the three Baltic states located near the state border with Latvia), the marine terminal in Būtingė and a pipeline system for transhipment of crude oil. OL's refined oil products, which comprise mainly gasoline, diesel and heavy fuel are sold in a number of countries, including, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Poland, the United States of America, Canada and Western Europe.

(8) OL is wholly owned by Polski Koncern Naftowy Orlen S.A. (“PKN”). PKN is a Polish company, operating seven oil refineries within Poland, the Czech Republic and Lithuania. It is active in the wholesale and retail of oil products in Central and Eastern Europe.

3. PROCEDURE

(9) On 14 July 2010, the Commission received a complaint ("the Complaint") pursuant to Article 7 of Regulation 1/2003 lodged by OL against LG.6

(10) In its Complaint OL explained that the Refinery is dependent on LG's rail transport services in order to transport its oil products to customers in Lithuania and Latvia, but principally to the Lithuanian seaport of Klaipėda for export by sea ("seaborne export"). According to the Complaint, in September 2008, after allegedly discovering the Deformation, LG immediately suspended traffic on the Track and in October 2008 LG removed the Track entirely. The Track was on the route from OL's refinery to the Latvian border and was used exclusively to transport OL's products to Latvia. OL argued that the actions of LG, in removing the Track, were not objectively justified and their purpose was to prevent OL from switching its seaborne exports to the Latvian seaports using the rail transport services of the Latvian railway company Latvijas dzelzceļš ("LDZ").

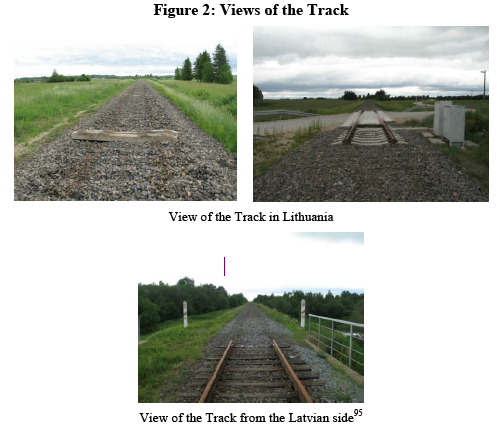

(11) Between 8 and 10 March 2011, the Commission, assisted by the national competition authorities in Lithuania and Latvia, carried out inspections under Article 20 of Regulation 1/2003 at the premises of LG in Vilnius, Lithuania and of LDZ in Riga, Latvia.

(12) On 6 March 2013, the Commission decided to initiate proceedings in the present case against LG pursuant to Article 2(1) of Commission Regulation No 773/2004. On the same day the Commission informed LDZ that it would not pursue any further the investigation against LDZ or its subsidiaries.7

(13) On 5 January 2015, the Commission adopted a Statement of Objections addressed to LG ("SO") presenting its preliminary conclusion that some of LG's actions constituted an infringement of Article 102 of the Treaty. LG responded in writing to the SO on 8 April 2015. OL submitted observations on a non-confidential version of the SO on 25 March 2015. LG provided comments on OL's observations on 8 April 2015.

(14) On 27 May 2015, an oral hearing took place during which LG made known its views. OL was also afforded the opportunity to express its views at the oral hearing pursuant to Article 6(2) of Regulation No 773/2004.

(15) On 23 October 2015 the Commission sent a letter of facts to LG ("Letter of Facts") to which it responded on 2 December 2015. On 29 February 2016, LG made a further submission to the Commission.8

4. DESCRIPTION OF LG'S PRACTICES WHICH ARE THE SUBJECT OF THIS DECISION

4.1. OL railway freight business

(16) OL produces approximately 8 million tonnes of refined oil products annually. It exports approximately 6 million tonnes of its production and was the single largest Lithuanian exporter.9 Between 4.5 and 5.5 million tonnes are exported annually by means of the Lithuanian seaport of Klaipėda to countries in Western Europe and beyond. Between 1 and 1.5 million tonnes are sold annually to customers in Estonia and Latvia. OL transports most of its products by rail10 and is a significant customer of LG, representing approximately [10]% to [20]% of the tonnage transported annually by LG and between [10]% to [20]% of its revenue. OL's traffic to Klaipėda alone accounts for between [5] to [10]% of LG's business.11 According to LG's statement, OL is "a significant source of funds for the activities of the Lithuanian railway sector".12

(17) OL transports between 1 and 1.5 million tonnes of its oil products to or through Latvia.13 Until September 2008 OL's main route for that purpose serving about 60% of the cargo, was the Bugeniai-Mažeikiai-Rengė route ("Short Route to Latvia"),14 a 34 kilometre route running from the Refinery through the railway junction in Mažeikiai to Rengė in Latvia. The Track that was removed as of 3 October 2008 and which is the subject of this Decision is a 19 kilometres long segment of the Short Route to Latvia located between Mažeikiai and the Latvian border. The Track was used exclusively for the transport of OL's products.15

(18) In order to transport its products on the Short Route to Latvia, OL had contracted LG services for the Lithuanian leg of the journey, that is, from the Refinery to the Latvian border. LG then had entered into a sub-contract with LDZ to transport OL's products from the Refinery.16 At the time LDZ did not have the regulatory authorisation to operate independently in the territory of Lithuania but operated as a sub-contractor of LG.17 After crossing the Latvian border, LDZ continued to transport the cargo within the territory of Latvia under various contractual arrangements.18

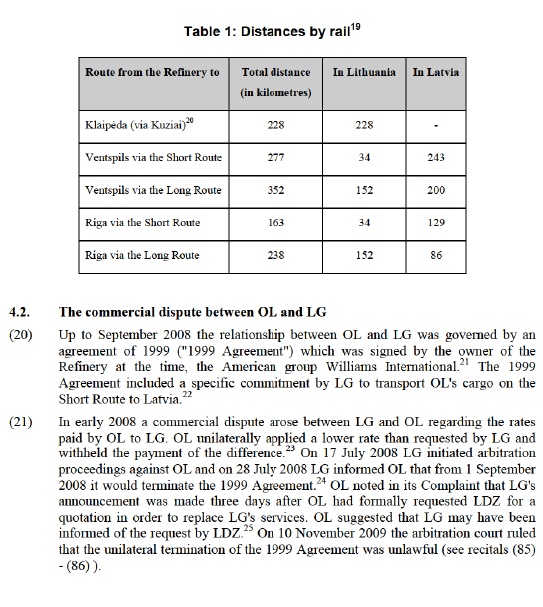

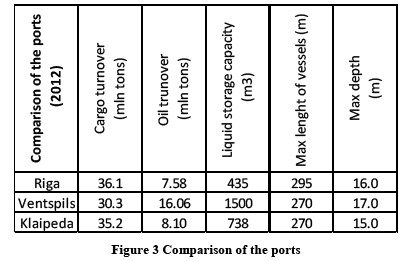

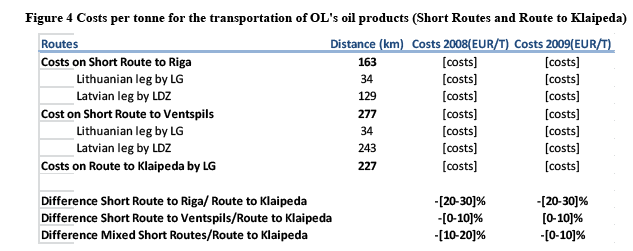

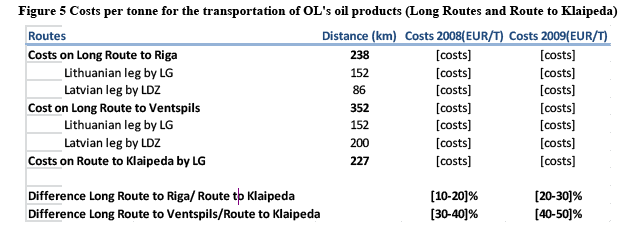

(19) Some of OL's products were transported to Latvia also on the Bugeniai-Joniškis- Meitene route ("Long Route to Latvia"). Since the suspension of traffic on the Track on 2 September 2008, all of the cargo previously transported on the Short Route to Latvia is being transported on this route. Figure and Table 1 describe the distances of the routes in Lithuania and Latvia that are relevant for this Decision:

4.3. OL sought to switch to LDZ and the Latvian seaports

(22) According to the Complaint, OL explored the possibility of contracting LDZ directly for rail transport services on the Short Route to Latvia because of its commercial dispute with LG. OL also argued that it was considering, in parallel, switching its seaborne export business from the Lithuanian seaport of Klaipėda to the Latvian seaports of Riga and/or Ventspils,26 transporting its cargo with LDZ.27

(23) On 4 April 2008 OL wrote to the Latvian Ministry of Transport and Communications stating that it was considering switching its seaborne export business to the Latvian seaport of Ventspils using LDZ's rail transport services and suggested organising a meeting to discuss the matter with the Ministry. Specifically, OL sought information about the rates and discounts it could expect for LDZ's rail transport services.28 In its response of 7 May 2008 the Ministry informed OL that it does not interfere with the commercial decisions of LDZ. Nevertheless, the Ministry wrote that it "has great interest in development of freight transportation in Latvia", noted that a meeting between OL and LDZ had been scheduled for later that month and promised to follow the results of that meeting.29

(24) Documents found at the premises of LG show that LG was aware of and was concerned by a possible switch by OL to the Latvian seaports and LDZ. Seized document MST4 (ID0601) is an email correspondence dated 19 March 2008, between LG's Deputy Head of the Technical Development Department, the Deputy Director for Commerce and the Head of Tariff Department30 It states:

"As regards Mažeikių nafta [that is OL] – question 3.

There the rates were still being compared with the rates proposed by the Latvians for carriage to Ventspils. [business secret]"31

(25) On 12 June 2008, a meeting was held between LG and OL where the matter seems to have been discussed further. According to LG's minutes, the parties were discussing the Bugeniai-Skuodas-Klaipėda track (see map in recital (19)) which had been closed since 1995. LG explained its position not to invest in the renovation of that track and, in that context, asked OL whether it was planning to transport oil products to the Latvian ports. OL responded that it was examining the possibility and that LDZ was willing to make the necessary investment. LG responded that in view of this situation, no economic grounds existed for the renovation of the Bugeniai-Skuodas-Klaipėda route.32

(26) Seized document VJ18 (ID0665) may add to the picture of LG's concerns. The document entitled "The main changes which are proposed to the agreement with AB Mažeikių nafta"33 [that is OL] was found on the laptop of the Director of LG's Commerce Department in the Freight Transportation Directorate.34 It is not dated but it still refers to the 1999 Agreement as "the current agreement" which means that the document must have been drafted before 1 September 2008 when the 1999 Agreement was terminated.35 In paragraph 2 of that document it is suggested to "implement an obligation to transport to Klaipėda not less than 6 million tonnes of cargo annually (maximum volumes, this amount may be adjusted in negotiations)"36 and in paragraph 7 it is suggested "to revoke the condition that MN [that is Mažeikių nafta -OL] is entitled to use [business secret] the Bugeniai-Rengė route"37. This document suggests that the possible loss of OL's rail traffic to Klaipėda was a matter of concern to LG before 1 September 2008 and that it may have been already anticipating circumstances in which it would not serve OL on the Short Route to Latvia.

(27) On 25 July 2008, OL formally requested from LDZ a quotation for the transportation of between 4.5 and 5 million tonnes of refined oil products per year from the Refinery, via the Short Route to Latvia, to "ports and terminals located in the territory of Latvia" commencing from the 4th quarter of 2008.38 LDZ made an offer on 29 September 2008 following an additional meeting with OL on 22 September 2008 (i.e. soon after the suspension of traffic on the Track, but before its removal).39 According to OL the offer made by LDZ was "concrete and attractive".40 On 17 October 2008 OL sent a letter to LDZ confirming its intention to transport approximately 4.5 million tonnes of oil products from the Refinery to the Latvian seaports;41 OL and LDZ met on 20 February 2009.42 Further discussions took place between them into spring 2009.43 According to information provided by LG in its response to the SO, negotiations between OL and LDZ continued until at least June 2009 when LDZ made an application for a licence to operate on the Track (see recital (111)).44 LDZ's perception at the time was that a switch to the Latvian seaports was a competitive constraint on LG.45 According to OL "the discussions with LDZ were not completely broken off until the middle of 2010, when OL finally recognized that LG had absolutely no intention to restore the Rengė track in the short term".46 Consequently LDZ withdrew its application for a licence to operate on the Track (see recital (111)).

4.4. The condition of the Track prior to 2 September 2008

(28) The Mažeikiai-Rengė track, running between Lithuania and Latvia, was built in 1873 when both countries were part of the Russian Empire.47 The last major maintenance works were carried out in 1972 on the Lithuanian side48 and 1973 on the Latvian side49 when both countries were part of the Soviet Union. Following the restoration of independence in 1990 the two legs of the Mažeikiai-Rengė track were maintained separately50 and neither LG nor LDZ can explain the difference in the condition of these two legs.51 It is therefore not clear why the condition of the Lithuanian leg had deteriorated to a point where traffic had to be suspended, as argued by LG, while the Latvian leg was in September 2008 and is still today, in good repair, according to LDZ.52

(29) A railway track can essentially be divided into the superstructure and the bed of the track. The superstructure is composed mainly of the rails and wooden or cement sleepers on which the rails lie. Other elements such as screws, braces, washers and gaskets are used to attach and fasten the rails and sleepers to each other and onto the bed of the track. The superstructure is then laid on the bed of the track. The upper part of the bed is a layer of ballast (crushed stone) that is used to stabilise the superstructure, to allow rain water to drain and suppress the growth of vegetation. The ballast is laid on an elevated structure of earth.

(30) On 3 September 2004, after an inspection of the Track, LG prepared a report on its condition ("Report of 3 September 2004") as a result of which the speed limit was lowered to 40 km/h. During the inspection, five segments of the Track were inspected. Defects in the superstructure were detected on all five segments, including 400 metres behind the 18th kilometre mark, the segment on which the Deformation was detected approximately four years later on 2 September 2008. Nearby at 500 metres behind the 18th kilometre mark, further defects in the superstructure and ballast were found. The Report of 3 September 2004 concluded that if the Track was not repaired immediately it should be inspected the following winter and, if longitudinal movements of the rails were detected, the speed limit should be reduced to 15/25 km/h.53

(31) The speed limit was reduced to 25km/h in February 2007 on four segments of the Track.54 On 13 May 2008, a new inspection of the Track took place ("May 2008 Inspection") and based on its findings on 29 May 2008, the speed on the segment 400-1000 metres behind the 18th kilometre mark was further lowered to 25 km/h.55 This segment of the track included the segment on which the Deformation was detected on 2 September 2008. During 2008 repair works were performed on the superstructure of the Track and five rails were replaced.56 According to LG, it did not consider suspending traffic on the Track after the May 2008 Inspection because "the speed limit still allowed for the rail traffic to continue and also because of the lack of sufficient funds for the repair works".57

4.5. September 2008: events leading to the removal of the Track

4.5.1.The detection of the Deformation

(32) On 2 September 2008, one day after the unilateral termination of the 1999 Agreement by LG, a monthly inspection of the Track identified the Deformation,58 400 metres behind the 18th kilometre mark (that is, within the segment on which speed had been limited to 25 km/h three months previously). Consequently, the traffic controller issued an order suspending traffic on the Track.59 A special inspection performed that day measured the Deformation; it found that the Deformation had occurred on a 40 metres section of the Track and concluded that it exceeded the allowed parameters.60

(33) The Deformation was detected during a regular monthly inspection. Prior to the inspection trains were running daily on the Track.61 The last train passed shortly before the Deformation was detected62 and no accident or serious problems were reported prior to that monthly inspection.

(34) OL later argued in the arbitration proceedings with LG that the latter infringed the 1999 Agreement by suspending traffic on the Track (see section 4.10). LG's position was that traffic was suspended only after the termination of the 1999 Agreement on 1 September 2008 and therefore LG was not under a contractual obligation to provide services to OL on the Track. This position was also expressed in a note found in the office of LG's Deputy CEO stating that the Deformation –

"occurred and the traffic on the track was suspended already after LG informed OL regarding the termination of the 1999 Agreement. (LG notified OL in a timely manner that if OL till September does not settle LG's invoices for the services, in this case LG unilaterally will terminate the validity of 1999 Agreement.)"63

(35) The same point was made in a document addressed to the Lithuanian government,64 where LG noted that-

"For the last two years, OL has been publically accusing LG and simultaneously its shareholder the Government of the Republic of Lithuania, of the alleged intentional dismantling of the Rengė section in breach of the obligation stipulated in the [1999] agreement and passiveness in reconstructing it, even disregarding the fact that the actions of dismantling the Rengė section were in fact started on 3 October 2008, that is when the 1999 Agreement between LG and OL was no longer in force."65

4.5.2. The reports of 5 September 2008

(36) On 3 September 2008 LG instigated an Inspection Commission composed of senior employees of its local branch66 to investigate the reasons for the Deformation. The Inspection Commission visited and inspected only the site of the Deformation67 and its findings regarding the condition of the Track referred only to that location.68 The Inspection Commission submitted two reports namely the "Report on the Investigation of 5 September 2008"69 and the "Technical Report of 5 September 2008".70 The Report on the Investigation of 5 September 2008, concluded that-

"the traffic incident 400m behind the 18th km of the Mažeikiai-Rengė section [that is the Track] was caused because of the physical deterioration of elements of the track superstructure: on the track about 70% of the braces deteriorated and approximately 80% of rail gaskets deteriorated."71

In the section on "remedial measures"72 the report stated that-

"The consequences of the incident will be remedied upon receipt of the materials needed for the track superstructure and the required funding for the repair works."73

(37) The Report on the Investigation of 5 September 2008 concluded that renovation works would only involve repair of the superstructure and no comment was made on the state of the bed of the Track or the quality of the ballast.

(38) These observations are supported by the Technical Report of 5 September 2008, which stated-

"During the investigation the following reasons for the deformation of the track were established:

(1) Stand screws are corroded, insulating axle-box are worn out. Due to worn-out clamps and used single coil spring washers the required threads could not be ensured so that could be duly fastened.

(2) The track has approx. 70 per cent of defective braces. The braces are physically worn-out therefore there is no enough stability on the track;

(3) The track has approx. 80 per cent of the rail gaskets which are worn out. Due to it the proper fastening of the long rails cannot be ensured.

(4) Due to the fact that the trains with cargo go only to one direction and because of the defective braces, there are some shifts of the position of the long rails.

The Commission has determined: the traffic accident which occurred as a deformation on 18 km 4 pk of the Mažeikiai-Rengė track should be qualified as a buckling, which happened due to physically worn out elements of the upper track construction."74

These findings were similar to those of the Report of 3 September 2004 (see recital (30) and the comparison in recital (46)).

(39) As with the Report on the Investigation of 5 September 2008, the findings of the Technical Report of 5 September 2008 refer only to the site of the Deformation. It identified various problems with the superstructure of the Track which were the causes to the Deformation. The report makes no reference to the bed of the Track or to the ballast.

(40) The "Protocol of the Operative Hearing",75 also dated 5 September 2008, repeats the findings of the Technical Report of 5 September 2008 and concluded again that the Deformation had occurred because of the physical deterioration of elements of the Track's superstructure. It did not contain any conclusion as to the necessary repair works.

4.5.3. The letters from the director of LG's local branch of 4 and 5 September 2008

(41) On 4 September 2008, a day before the Inspection Commission submitted the Report on the Investigation of 5 September 2008 and the Technical Report of 5 September 2008, the director of LG's local branch (the "Local Director") sent a letter to the company's Railways Infrastructure Directorate (the "Letter from the Local Director of 4 September 2008"). In that letter the Local Director noted the same findings as the Report of the Investigation of 5 September 2008 and the Technical Report of 5 September 2008, but concluded that "partial track repair will not solve the problem"76 and requested permission and financing to implement a project to repair the entire Track.77 The Local Director repeated his conclusions in a second letter on 5 September 2008 (the "Letter from the Local Director of 5 September 2008") and estimated the costs of the works at LTL 38 million78 (EUR 11 Million79). On the same day LG's Railways Infrastructure Directorate issued a telegram ordering the suspension of traffic on the Track until repair works were completed.80

(42) The Commission asked LG to clarify the basis on which the Local Director reached his conclusion that a comprehensive renovation of the Track was needed considering that the reports of 5 September 2008 referred only to the site of the Deformation and recommended only local repair of the superstructure. LG responded that-

"The conclusion that repair works were needed on the entire 19 km of the track was based on the technical revision report of the commission for extraordinary inspection, established on 10 September 2008 [see section 4.5.4]".81

However, the Letter from the Local Director of 4 September 2008 had already been sent six days earlier hence the response of LG is implausible.

(43) In its Response to the SO, LG explained that compared to the Reports of 5 September 2008, the Local Director identified a new element in the analysis, namely "a link between the wear of the rail gaskets and the impossibility to fasten long rail"82 which explains the different conclusion. LG stated also that "the conclusion of the Local Director was based on bad experiences with the Track since 2004",83 specifically the failure of the speed reduction to prevent the Deformation.84

(44) The Commission notes that the letters from the director of LG's local branch of 4 and 5 September 2008 do not mention the failure of the speed reduction to prevent the Deformation. Moreover, the members of the Inspection Commission that prepared the Report of the Investigation of 5 September 2008 and the Technical Report of 5 September 2008 were senior employees of the same branch (see recital (36)) who must have been also familiar with the history of the Track. LG did not contest this conclusion.85 Moreover, the Local Director did not set out in his letters findings that were different than those made by the Inspection Commission. The differences between their conclusions remain therefore unexplained.

4.5.4. The Extraordinary Inspection Report of 12 September 2008

(45) On 10 September 2008 LG appointed another commission for an "extraordinary inspection" of the Track, composed of LG's employees86 who inspected the entire 19 kilometres of the Track.87 In its report of 12 September 2008 (the "Extraordinary Inspection Report of 12 September 2008") the commission noted:

(1) Various defects in the superstructure at various locations along the Track that were specifically identified (e.g. 900 metres behind the 18th kilometre mark). These defects were not limited to the site of the Deformation.

(2) The general unsatisfactory condition of the ballast and the upper width of the Track.

(3) Gullies (carving in the bed of a track created by running water) in four locations on the Track: 8km 7pk, 10km 4pk, 11km 2pk, 18km 9pk.

(4) The signalling and overhead lines were physically worn out and in a critical condition.

The report concluded that these defects "pose a real threat to train traffic safety".88

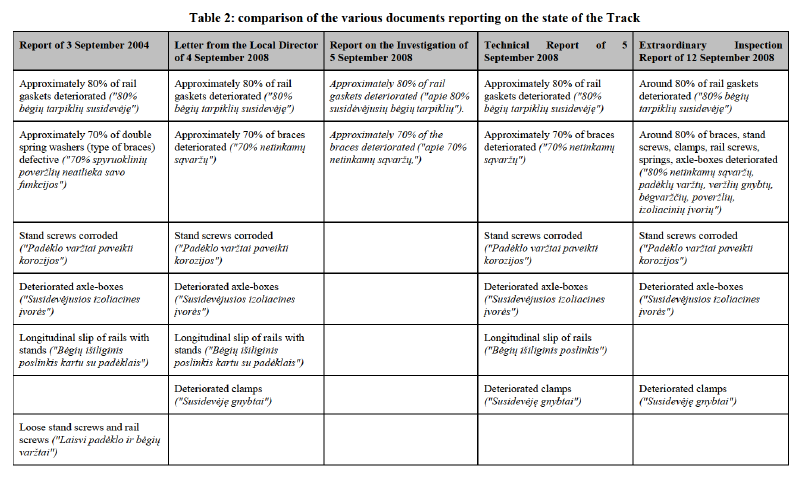

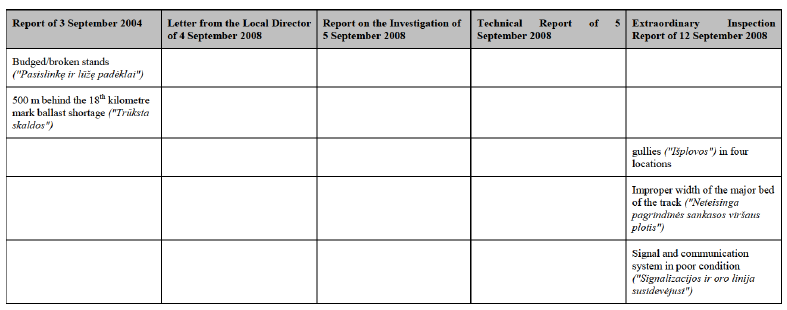

(46) Table 2 compares the documents reporting on the state of the Track:

(47) It can be seen that the findings of the various documents are almost identical. The Extraordinary Inspection Report of 12 September 2008 however found that Approximately 80% of the braces were defective although the Report on the Investigation of 5 September 2008 and the Technical Report of 5 September 2008, drafted only a week previously, found that approximately 70% of the braces were defective, which is the same level as in 2004. The Extraordinary Inspection Report of 12 September 2008 also identified problems with the width of the bed of the Track and the signal communication systems, problems that were not identified previously.

4.5.5. The decision to remove the Track

(48) On 18 September 2008 LG's Deputy Director General and Director of the LG's Railways Infrastructure Directorate sent a letter to LG's Strategic Planning Council, discussing in general terms the condition of certain regional rail tracks in Lithuania and more specifically the Track.89 That letter stated that the Extraordinary Inspection Report of 12 September 2008 concluded that the following works were necessary in order to renew traffic on the Track: 1.6 kilometres of rails had to be laid anew, fastenings had to be replaced along the entire 19 kilometres of the Track, the railway bed had to be repaired, and communication cables had to be replaced along the 19 kilometres of the Track.90 The costs of such works were estimated at LTL 21.3 million (EUR 6.17 million). However, he explained that due to the overall poor condition the Track, the Track would still have to undergo major repair works within five years in order to ensure safe train traffic. The total cost of those works was estimated at LTL 40 million (EUR 11.59 million). The letter concluded with a recommendation that the entire Track should be repaired and that LG should therefore apply to the Ministry of Transport of Lithuania for funding a feasibility study concerning the renovation of the Track and other regional tracks and, in accordance with the results of that study, apply for a supplementary state subsidy for the renovation and development of those tracks.

(49) On 19 September 2008,91 LG's Strategic Planning Council decided to approve the renovation of five railway lines including the Track, to apply to the Ministry of Transport for allocation of funding from the state’s budget and Union funds for the renovation of these lines. Moreover, LG's strategic Planning Council decided to-

"Approve the immediate commencement of renovation work on the Mažeikiai– State border (direction Rengė) line. Charge the DI with dismantling the track superstructure, using suitable materials to repair other sections of the railway line and scrapping those that are not suitable for the purpose." 92

In the following weeks, most likely starting on 3 October 2008,93 LG removed the Track at its own expense94 before obtaining the results of the proposed feasibility study and before having secured funding for renovating the Track.

(50) The Track has not been renovated to date. Since the suspension of traffic on the Track, OL’s affected cargo has been transported to Latvia on the Long Route to Latvia.

4.6. Involvement of the Lithuanian State Railways Inspectorate

(51) As described above, the investigation of the Deformation and the decision making process which led to the removal of the Track was conducted solely by LG's own personnel. LG has stated that the documents arising from the various investigations were submitted to the Lithuanian State Railways Inspectorate (Valstybinė geležinkelio inspekcija prie Susisiekimo ministerijos, "VGI").96

(52) The Commission requested LG to furnish the file that was submitted to the VGI following the Deformation and asked LG to clarify the involvement of the VGI in the investigation. It appears that LG submitted the Report of 3 September 2004, the Report on the Investigation of 5 September 2008 and the Technical Report of 5 September 2008 to the VGI. Those reports found that the Deformation could be repaired by local works on the superstructure. The VGI made no comment in relation to these reports. The documents recommending immediate and comprehensive renovation of the entire Track and the decision to commence works and remove the Track, namely the letter of 18 September 2008 of LG's Deputy Director General to Strategic Planning Council (see recital (48)) and the decision of LG's Strategic Planning Council of 19 September 2008 (see recital (49)) were not communicated to the VGI.97 The VGI also did not visit the site of the Deformation or any other part of the Track.98

(53) According to LG, it acted in accordance to Lithuanian law. The decision to suspend traffic on a rail track or perform works on a rail track was not part of the purview of the VGI at the time and LG was not obliged by law to provide more information to the VGI.99 Irrespective of the question of whether LG was under a legal obligation to provide the VGI with more information or whether the VGI should have done more in supervising LG, the VGI's silence cannot be construed as an approval of LG's actions (see also section 4.10 with regard to the second arbitration decision).

4.7. Information given to OL on LG's actions

(54) LG did not inform OL of the situation of the Track and LG's actions to remedy it. On 4 September 2008, a train loaded with OL's products was diverted to a different and longer route, without OL being consulted or informed. OL enquired by letter to LG why its cargo had been redirected to the Long Route to Latvia.100 On 5 September 2008, LG informed OL by phone about the Deformation and suspension of traffic on the Track.101

(55) OL was not informed of LG's intention to remove the Track. In response to the question whether LG notified or consulted with OL before removing the Track, LG stated that the removal was objectively necessary and LG did not have to consult with OL. OL, as a client, was informed through the railway stations about the "temporary closure" of the Track.102

4.8. The new transport agreement between LG and OL

(56) On 1 October 2008 LG and OL signed an interim transport agreement.103 In January 2009 a new general transport agreement was concluded between LG and OL ("2009 Agreement").104

(57) The 2009 Agreement used as its basis the standard pricing policy of LG in relation to rates (the "Tariff Book") which attributes a basic rate to each route in Lithuania. The 2009 Agreement applies a system of discounts to the Tariff Book rate.105 [business secret]106 [business secret]107 [business secret]

(58) [business secret]108 [business secret]109 [business secret]110

(59) With respect to the Long Route to Latvia (and only in relation to that route) a fixed rate of LTL [10-20] was applied until traffic on the Track is reinstated. This rate was substantially lower than the standard Tariff Book rate [business secret].111 This fixed rate is however still 40% higher than the rate OL used to pay for rail transport services on the Short Route to Latvia.112

(60) The 2009 Agreement was concluded for a period of 15 years, until 1 January 2024, [business secret]113

4.9. Funding the reconstruction of the Track

4.9.1. The initial request for funding

(61) LG claims that in September 2008 its intention had been to carry out the necessary works on the Track as soon as possible. LG claims that it therefore had decided on 22 September 2008 (in fact: 19 September 2008, see footnote 91) to immediately start the renovation works by removing the Track as well as applying to the Ministry of Transport for the allocation of financing. LG maintains that when the Track was removed it acted on the basis of reasonable expectation that the necessary funding would be granted for the renovation of the entire Track. However "no funds for these works were allocated in 2009".114

(62) The Commission notes that LG submitted its request for funding on 2 October 2008, a day before starting the removal of the Track, in a short letter to the Minister of Transport requesting a sum of LTL 620 million (EUR 179.71 million) for the renovation of 8 different tracks.115 No specific representations reference were made with respect to the Track. The Ministry's response of 28 October 2008 was that since these projects had not been approved in the past no provision for their financing was made. The Ministry reminded LG that Union Funds were still available and invited LG to identify projects for financing.116

4.9.2. The Feasibility Study

(63) Following the response of the Ministry of Transport of 28 October 2008, that is after the entire Track had already been removed, LG initiated the preparation of a feasibility study concerning the renovation and development of the eight rail tracks referred to in LG's letter to the Ministry of Transport of 2 October 2008 ("Feasibility Study"). On 11 December 2008 LG's Technical Board approved the outlines of the Feasibility Study.117

(64) It took eight months after the approval of the Technical Board to receive the approval of the Director General of LG on 29 July 2009118 and approximately three additional months to publish the call for tenders, in the second half of October 2009.119 The Interim Feasibility Study was submitted on 8 June 2010120 and the Final Feasibility Study on 8 October 2010.121

(65) The Final Feasibility Study found that the reconstruction of the Track was recommended.122 It reached this conclusion although it used a much higher cost estimate (LTL 66 million (EUR 19.13 million), excluding VAT123) than LG's estimate (LTL 41 million (EUR 11.88 million) excluding VAT, LTL 49.6 million (EUR 14.38 milion) including VAT).124

(66) LG explained that the difference in the estimated cost of the works was because of the increased price level between 2008 and 2010.125 However, in February 2010 LG asked the Ministry of Transport to grant the reconstruction of the Track priority for Union funding and the request was approved in May 2010. The cost estimate submitted and approved amounted to LTL 41 million (49.6 million including VAT) without any adjustment,126 thereby ignoring the alleged price increase.

(67) Although a request for EU funding must be supported by a feasibility study,127 LG did not wait for the results of the Feasibility Study. In February 2010, that is eight months before the Final Feasibility Study was submitted, LG requested that the Ministry of Transport grant priority for Union funding for the reconstruction of the Track (see section 4.9.6). The Commission asked LG why it identified the Track as a priority when, according to its own statements,128 the Track was of low priority and there were not enough Union funds to finance the priority rail lines. LG's response was that it implemented a decision of 30 November 2009 by the Lithuanian government (see next recital).129

(68) On 30 November 2009 the Lithuanian government held a meeting in order to address various requests made by OL and in order to consider possible solutions in view of the company's "strategic importance… to the Lithuanian economy".130 At that meeting, the Lithuanian government delegated to "the Ministry of Transport together with AB "Lietuvos geležinkeliai" and AB "ORLEN Lietuva" to adopt decisions regarding the traffic renewal on [the Track] as well as to notify the government on the adopted decisions."131 This decision of the Lithuanian government was taken at a moment when the pressure on LG regarding the Track was increasing. On 22 October 2009, OL had made an offer to assist LG finance the reconstruction of the Track (see section 4.9.4). On 10 November 2009, an arbitration court found that the unilateral termination of the 1999 Agreement was unlawful and a second arbitration procedure was looming (see recitals (85) - (87)).

(69) Soon after the meeting of 30 November 2009, LG included the reconstruction of the Track in its 2010-2015 investment plan (see recitals (75) - (78)) and asked the Ministry of Transport to grant the project priority for EU funding without waiting for the results of the Feasibility Study.

4.9.3. State funds

(70) In parallel to the Feasibility Study process for the purpose of obtaining EU funding, LG claimed that it had approached the Ministry of Transport on three separate occasions (29 April 2009; 19 May 2009 and 21 August 2009) in order to request that the reconstruction of the Track be included in the state investment programme.132 Indeed, in LG's letter of 21 August 2009, sent to the Ministry of Transport together with a draft proposal for the state investment programme, LG requested the Ministry of Transport to assign the funding for the reconstruction of the Track from the state capital investment funds allocated for the period of 2010-2012.133

(71) LG was aware of the difficulties in securing state financing. In its letter to OL of 11 December 2009, LG stated that-

"Given the country's economic finance and crisis and taking into consideration the fact that during these difficult times it would be difficult for the state to find the necessary funds for the financing of the project, AB "Lietuvos geležinkeliai" started the necessary steps in order to find alternative sources of financing for the implementation of the project, without waiting for the state budget assignations for year 2010."134

(72) Four days later, on 16 December 2009, in a letter to the Ministry of Transport LG reiterated its position that the State funding would not be granted and noted that-

"Since October 2008 LG had started the necessary steps in looking for alternative financing options for the implementation of the project without waiting for the State budget assignations for the year 2010, that is in accordance with the requirements of the EU and Lithuanian laws it started performing the necessary procedures for implementation of the project by partially financing it from the EU financial assistance."135

4.9.4. OL's funding offer

(73) On 22 October 2009, OL approached LG by letter stating that it was willing to cover the reconstruction costs of the Track and wished to discuss the possibilities of recovering its investment.136 OL never received a formal response to its offer and was only informed orally of LG's rejection at a meeting with LG's Chairperson of the Board (and at the time simultaneously Vice Minister for Transport and Communications, see also recitals (107) - (109)).137 According to LG, pursuant to the law governing the activities of the railway infrastructure manager, the creation, upgrading and development of public railway infrastructure cannot be financed by using private investment possibilities.138

(74) In its "Strategic Activity Plan for 2010-2012" from 2009, LG provided two further explanations for its rejection of the offer. Firstly, in order to take a loan LG must initiate an open tender procedure in which it cannot be guarantee the success of OL. Secondly, LG had reached its borrowing limit and could not have borrowed more without the consent of its creditors.139

4.9.5. The self-financing option

(75) On 22 December 2009, a few weeks after the decision of the Lithuanian government of 30 November 2009 (see recital (68)), LG prepared a note for the Ministry of Transport that was signed by its Deputy Managing Director for infrastructure. The note laid down a detailed timeline for the carrying out of the renovation works in case the Ministry of Transport were to order that LG finance the reconstruction of the Track from its own resources. The note promised that in view of the importance of the project the process would be accelerated and works would be completed by the end of 2011.140

(76) On the same day, 22 December 2009, a meeting was held at the Ministry of Transport which included representatives of both LG and OL. During that meeting LG presented three funding options for the reconstruction of the Track: state funds, Union funds and LG's own resources.141 As described above, LG was very sceptical that state funds would be allocated, a position it had expressed a few days earlier in its letters to OL and to the Ministry of Transport. As set out below, the option of financing the reconstruction works by means of LG's own resources would be dependent on the reimbursement of those costs by means of Union funds.

(77) In the meeting of 22 December 2009 LG repeated its commitment to accelerate the process of reconstructing the Track, concluding it within two years. LG reiterated that lower tariffs for the Long Route to Latvia had already been negotiated and indicated that it was willing to consider lowering them further. It was decided that OL would present LG with its demands ("suggestions regarding business optimisation"142) for the interim period until the Track was reconstructed.143

(78) Following the meeting of 22 December 2009, on 31 December 2009, LG amended its own 2010-2015 investment plan to include the reconstruction of the Track at the expense of other projects.144 Soon afterwards, on 21 January 2010, LG wrote to the Ministry of Transport asking for its support in securing Union funds for the reconstruction of the Track and laid down a detailed request for re-prioritisation of various projects in order to allocate funds. The letter seems to suggest that LG's idea was that it would commence by financing the reconstruction of the Track by financing the project from its own resources, which had been dedicated to maintenance works and, following the completion of the project, when the Union funds would be disbursed, LG would use those funds for the financing of projects that were removed from LG's 2010-2015 maintenance plan for that purpose and were supposed to be financed by LG's own funds.145

4.9.6. Union Funds

(79) On 8 February 2010, LG submitted a "project proposal" to the State Project Planning and Selection Commission with a request to include the reconstruction of the Track in the priority list for Union funding.146 As explained above, LG stated that it did so in order to comply with the decision the Lithuanian government of 30 November 2009 (see recitals (68) and (69))

(80) For the purpose of that request, LG stated that "this regional line [that is the Track] has an unquestionable international track status and influences international communication with Latvia"147 and its reconstruction is "of an international and strategic importance, it can be concluded that it complies with the main criteria to receive the EU structural fund assistance."148 On 27 April 2010, the State Project Planning and Selection Commission recommended to the Minister of Transport that priority be granted to the project,149 which the Minister so granted on 3 May 2010.150

(81) Following the approval of the project proposal of 8 February 2010, LG completed several further steps in the procedure: the Feasibility Study was completed on 8 October 2010; the Technical Project, that is the document that details all necessary works, was approved on 5 May 2011; and a construction permit was issued by the Mažeikiai district municipality on 17 June 2011.151

4.9.7. Removal from the priority list for Union funding

(82) Subsequently, however, LG prepared a number of documents for the Lithuanian government arguing against the reconstruction of the Track. Those documents argue that rebuilding the Track would be uneconomical (although the Final Feasibility Study later recommended the project; see recital (65)), that after the reconstruction of the Track OL would switch to the Latvian seaports, that LDZ would take over OL's rail business and that the investments made on the route to Klaipėda would be lost (those documents are discussed in detail below (see recitals (92) to (96), (103)).

(83) On 29 September 2011, nine months after the favourable decision in the arbitration procedure against OL (see recital (88)), in a meeting of the State Project Planning and Selection Commission, LG recommended removing the Track’s reconstruction project from the list of priority projects for Union funding in order to finance a different project. LG explained that-

"Under the decision reached by the arbitration court… LG has the right not to reconstruct the [Track], and [OL] did not oppose LG's intention to exercise this right [...]

The [Track] was and, after reconstruction, would continue to serve the needs of only one of the company's clients, namely [OL], although those needs could be fully met by the Kužiai-Mažeikiai main railway line [that is the Long Route].

Given that the court's decision removed not only the economic but also the legal grounds for carrying out the project to reconstruct the Mažeikiai-state border section of [the] railway line, LG proposes to transfer it to the list of reserve projects."152

The State Project Planning and Selection Commission accepted LG's request and recommended to the Minister of Transport and Communications to remove the reconstruction of the Track project from the list of priority project for Union funding and to place it on the reserve list.153

(84) On 4 October 2011, the Minister of Transport and Communications ordered the removal of the reconstruction of the Track project from the priority list for Union funding and downgraded it to the reserve list.154 Consequently, LG considered that the reconstruction of the Track project would in all likelihood not be funded.155 Since then LG has not taken any further steps with view of rebuilding the Track.

4.10. Arbitration between LG and OL

(85) On 17 July 2008, LG initiated an arbitration procedure with OL in relation to their dispute regarding the calculation of transport rates (see recital (21)).

(86) On 10 November 2009, an arbitration court held that LG's unilateral termination of the 1999 Agreement was unlawful and that the 1999 Agreement had been in force until 1 October 2008 when OL and LG concluded an interim transport agreement (see recital (56); the "First Arbitration Decision").156 The First Arbitration Decision exposed LG to the claim that it breached the 1999 Agreement by making the Track unavailable to OL between 2 September 2008 and 1 October 2008 (see recital (20)).

(87) Following the First Arbitration Decision, on 22 January 2010, OL initiated a second arbitration procedure with LG raising various claims stemming from the First Arbitration Decision.157 Of relevance to this Decision is the allegation that, by suspending traffic on the Track, LG had breached its obligation under the 1999 Agreement to provide rail transport services to OL on the Track until 1 October 2008. The subsequent decision of the arbitration court was handed down on 17 December 2010 (the "Second Arbitration Decision").

(88) In the Second Arbitration Decision the arbitration court held that under the 1999 Agreement LG had a "best efforts" obligation and not an absolute obligation to provide rail transport services to OL on the Track.158 The arbitration court was of the opinion that there was an objective need to repair the Track, which was not a result of LG's actions.159 It also noted that the VGI did not issue any sanctions against LG and therefore, concluded that LG had acted in accordance with its legal requirements.160

(89) In the Second Arbitration Decision, the arbitration court examined only the period between 2 September 2008 and 1 October 2008 when OL alleged that LG had breached its obligation to provide rail transport services to OL on the Track. The removal of the Track in October 2008 therefore fell outside of the scope of the arbitration court's examination. The reasons for the removal of the Track were not discussed during the arbitration procedure. The position of OL during this arbitration procedure was that LG undertook an absolute contractual obligation to transport OL's cargo on the Short Route to Latvia and therefore had an obligation to ensure that the Track was operational. OL argued that the unavailability of the Track alone, regardless of the reasons behind the closure of the Track was a breach of the 1999 Agreement.161 OL did not advance any arguments doubting the occurrence of the Deformation occurred, the necessity for removing the Track or LG's motives in doing so.

(90) As set out above (see recital (83)), the Second Arbitration Decision removed any concerns about any contractual obligation which LG may have had towards OL with respect to the Track162 and prompted LG to recommend the removal of the reconstruction of the Track project from the priority list of projects for Union funding.

4.11. Evidence regarding LG's concerns with respect to the Track

(91) Documents seized at LG's premises indicate that LG was concerned about competition from Latvia, specifically from LDZ, and about OL switching to the Latvian seaports for its seaborne exports.

4.11.1. Seized document LK7

(92) Seized document LK7 entitled "Statement – Questions relating to AB Orlen Lietuva"163 contains an extensive description of the relationship between OL and LG (including information in relation to revenue, rates, quantities, and conditions), a detailed timeline for the reconstruction of the Track and various arguments against it. The document is neither addressed nor dated and seems to be a draft. According to LG's response to the Commission's request for information, it was prepared in July 2010 by various departments of LG for the purpose of "internal analysis"164 although in its response to the Commission's second request for information LG seems to have suggested that the document was intended to be addressed to the Lithuanian government.165 The most complete version of the document, seized document LK7, was found at the office of the LG's Deputy CEO for infrastructure; parts of the document (seized documents JI4 and JI5) were found at the office of the CEO. Elements of the document (figures, arguments, tables) were also found in other documents of LG's Deputy CEO.166 The fact that the document was drafted by several departments and found in the offices of members of the highest levels of LG's management indicates that the views presented therein were those of LG.

(93) Under the headline "Dangers related to the reconstruction of the Mažeikiai – state border (in the direction of Rengė) section"167 LG noted that-

(1) LDZ will take over OL cargo in the direction of Latvia (1-1.5 million tonnes) resulting in an annual loss of revenue to LG of LTL [10-30] million (approximately EUR [3-10] million).

(2) OL freight transported to the Lithuanian seaport of Klaipėda would be redirected to the Latvian seaport of Ventspils since the latter would be better placed to accept larger capacity tankers than the first and because LDZ could offer rates that are [percentage] lower than those charged by LG for rail transport services to Klaipėda. LG's annual loss was estimated at LTL [100- 150] million (approximately EUR [30-50] million) and it was noted that the seaport of Klaipėda would lose its main client.

The document also contains a map of the relevant routes in Lithuania and Latvia and a table comparing the length of these routes and the respective rates that LDZ and LG could offer.

(94) Annex 3 of the document is entitled "Advantages of the Latvian railways operator (LDZ Cargo) against LG in transporting the freight of AB 'ORLEN Lietuva' in the direction of Rengė".168 LG noted that-

(1) There were neither technological nor organisational barriers for LDZ to operate on the Short Route to Latvia and in fact LDZ was already cooperating with LG in transporting OL's cargo (see recital (18)). Transportation by LDZ would be even more attractive since LDZ could transport OL's cargo to Latvia without changing locomotive and crew and without any additional investment.

(2) It would be more difficult for LG than for LDZ to transport OL's cargo to seaports in Latvia. LG would have to establish a certain infrastructure in order to operate in Latvia. LG could use LDZ's services and not establish its own infrastructure in Latvia however in this case LDZ as a competitor would dictate its conditions.

(3) LDZ is in a position to pursue an aggressive rate policy and could undercut LG.

(95) The document also endeavours to show that the reconstruction of the Track would not be economical since the cost of reconstruction and maintenance could not be recouped from infrastructure charges. However, this is contrary to the conclusion of the final Feasibility Report of October 2010 recommended the reconstruction of the Track (see recital (65)).169

4.11.2. Seized document VJ16170

(96) Pages 1-12/20 of seized document VJ16, were prepared by LG's Deputy CEO and dated 28 December 2010, soon after the Second Arbitration Decision was handed down. It seems that the document was intended for the Lithuanian government.171 Under the heading "significance of the Rengė section"172 the document states that-

"LG draws the attention that upon reconstruction of the Rengė section, Lithuania may face a threat that OL freight transported to Klaipėda port may be directed to Ventspilis port."173 (Emphasis in the original document)

The document reproduced the figures and the map presented in seized document LK7 and also added that-

"Following the reconstruction of the Rengė section, OL - reasoning by Ventspilis alternative - will have a possibility to request reduction of the tariffs in the direction of Klaipėda and reduction of the tariffs for services in Klaipėda port. The reconstruction of the Rengė section is urgent to OL not because of the transportation of the existing products in the direction of Latvia, as OL had obtained the respective compensations in the agreement, but because of the strategic interests to gain a possibility to “exert pressure” on Lithuania in respect of tariffs or direct export of all or part of the products via Ventspilis port."174

These arguments were also reiterated in the concluding part of the document.175

4.11.3. Seized documents VJ9

(97) Seized document VJ9 is an undated handwritten note of LG's Deputy CEO. It expresses very similar concerns to those expressed in seized documents LK7 and VJ16. It discusses the possibility of competition from Latvia and an independent Latvian operator, Baltijas Tranzīta Serviss, is referred to as a possible threat.176 Under the heading "takes over cargo from LG" it is noted "8 million tonnes – MN" which is a reference to "Mažeikių nafta", OL's name until September 2009, and to its annual 8 million tonnes of cargo transported by LG.177 The note discusses the possible threats to the interests of the seaport Klaipėda and under the heading "measures"178 it states-

"2. Technical barrier

3. Creation of the integrated logistics chain LG-port-stevedoring companies by providing the general tariff of the service (actually, a logistics monopoly)

3. Synchronisation of the capacities of the logistics chain."179

(98) Under the heading "defence from Latvia"180 the document notes181-

"1) UIC (rolling stock)

2) permission to LG not to provide additional services (that is by applying adequate prices)

3) not to provide assistance to the Latvians in the seaport (including stevedoring companies)

To prepare a general tariff and no other + additional services by stevedoring companies.

To establish one chain “port company, port and LG”

Stevedoring companies could set very high tariffs for Latvia."182

(99) In a number of places the document discusses the "law reform" namely the transposition of the EU rail legislation into domestic law and the possible lobbying activities to influence it. The issue of separating infrastructure management and transport operation (see section 5) is specifically noted.183

4.11.4. Seized documents VJ20

(100) Seized documents VJ20 is an email dated 23 June 2009 sent by LG's then Deputy Director for Commerce to the Head of Marketing Service in the Tariff Department. this document expresses LG's concern that LDZ would obtain a permit to operate in Lithuania and consequently would gain OL's business. The email discusses possible contractual arrangements between LG and LDZ and notes that the suggested model- "would allow us avoiding the risk of interception by LDZ of a part of our transportation (in particular MN [that is OL] transportations ) after obtaining a safety certificate in Lithuania."184

(101) LG argued in its response to the SO that- "documents VJ9 and VJ20 never mention the Track Bugeniai – Rengė explicitly and such a link cannot be simply implied from the content of documents VJ9 and VJ20. As a result, these documents are not relevant to prove LG's concerns regarding the Track and they correspond to a simple expression of LG's commercial thinking, which is necessary in each company."185

(102) Although documents VJ9 and VJ20 do not refer to the Track explicitly they reflect LG's deep concern of losing OL's seaborne export traffic to a Latvian competitor. Section 7.4 demonstrates that this competitive constraint was dependent on the Track.

4.11.5. Seized document ES9/VJ6

(103) This document was found in two copies identified as ES9 (ID0816) and VJ6 (ID0651) in the office of LG's Deputy CEO.186 Although undated it appears to have been drafted in 2009.187 It is entitled "Statement – on the strategic interests of AB Orlen"188. The arguments made in the document refer also to the interests of the state of Lithuania and the seaport of Klaipėda, suggesting that it was intended for the Lithuanian government. The document makes the following points:

(1) It is in the interest of Lithuania to keep all economic activities of OL within its territory including transport and storage.189

(2) Latvia is interested in OL switching to its seaports and has made "all kinds of efforts"190 in that respect including applying for a permit for LDZ to operate in Lithuania.191

(3) It compares the distances and transport rates to Klaipėda and to the Latvian seaport of Ventspils on the Long and Short Routes to Latvia concluding that on the latter LDZ could make a very competitive offer.192

(4) A switch by OL to the Latvian seaports on the reconstructed Track would mean a significant financial loss to LG and to the Lithuanian State.193

(5) Under the heading "proposed solution"194 it is argued that the current transport via the Long Route to Latvia satisfies OL's needs and that the issue of renewal of traffic on the Short Route to Latvia "is no longer a Government-level issue".195

4.11.6. Seized document LK13

(104) Seized document LK13 was found in the office of the Chief Specialist in LG's General Division of the Internal Administration and Safety Department.196 The document contains shorthand minutes of a meeting of LG's Board197 held on 7 March

2011.198 This was the day before the Commission conducted unannounced inspections at LG's premises. LG later provided the Commission with the official minutes of the meeting to which LK13 refers.199

(105) While the shorthand minutes do not set out precisely the discussion which took place at the meeting of 7 March 2011, they make clear that LG's board discussed the rates charged to OL, the reconstruction of the Track and OL's future contract with the seaport of Klaipėda. The Chairperson of the Board commented about "competition for the line to Ventspils"200 and that "if Klaipėdos nafta signs then LG carries via Klaipėda".201 The Board decided "to assign the administration of the company to analyse the possibilities to grant Orlen the discounts for the traffic to Klaipėda in return for giving up the reconstruction of the [Track]".202

(106) Those documents illustrate again LG's preoccupation with the link between the reconstruction of the Track, the threat of competition from the Latvian seaports and transport of OL's oil products by LG to Klaipėda.

4.11.7. Annex 33 of the Complaint

(107) In its Complaint, OL claimed that a meeting took place on 16 March 2010 (that is before seized documents LK7 and VJ16 were drafted) between the President of OL's board and the Chairperson of LG's Board who was at the time also the Lithuanian Vice-Minister for Transport and Communications. According to OL the Chairperson of LG's Board "explicitly declared that special tariffs would be conditional on OL transporting its refined oil products destined to seaborne export to Klaipėda the Lithuanian port".203

(108) The language of the internal minutes of the meeting, that were drafted by OL, suggests that the Chairperson of LG's Board made any further rate discounts conditioned on a guarantee from OL with respect to the "volume and the direction of transport" of OL's oil products. The drafter of the minutes added an explanation that this was a reference to the seaport of Klaipėda.204

(109) LG did not deny, or make any comment, on this point although the minutes were provided to LG together with the non-confidential version of the Complaint.LG did however comment on another argument made by OL with respect to those minutes.205 In its Response to the SO, LG only noted that the document also stated: "Response on Rengė route - The reconstruction will be carried out on basis of EU funds. They do not accept the possibility of using OL as substitute investor. He anticipates that the reconstruction will last till 2012." According to LG this is "proof that LG's purpose was to respond to the claims of OL, notably by reconstructing the Track."206 Indeed, the meeting took place few weeks after LG submitted the project proposal of 8 February 2010 to reconstruct the Track (see recital (79)) but in view of LG's actual actions described above, the Commission does not accept that this statement is evidence that LG genuinely intended at any time to rebuild the Track.

4.12. LDZ's entry into the Lithuanian Market

(110) As noted in recital (18), in 2008 LDZ did not have the necessary regulatory authorisations to operate independently in Lithuania. At that time LDZ operated in Lithuania as a sub-contractor of LG and under its supervision. Under such arrangement it was also transporting OL's products on the Short Route to Latvia. When crossing the border, the train came under the sole responsibility of LDZ.

(111) In June 2009, LDZ started the process to obtain the necessary regulatory authorisations in order to operate independently in Lithuania. It made a request to operate on three routes in Lithuania. Two of those routes were for freight trains: from the Latvian border to Radviliškis (20 kilometres south to the Kužiai junction, see map in recital (22)) and the Short Route to Latvia. The third route from the Latvian border to Vilnius, was for passenger trains. However, the final formal application submitted in October 2011 referred only to the Latvian border – Radviliškis route, which runs along a part of the Long Route to Latvia.207 LDZ explained that the application with respect to the Short Route to Latvia was withdrawn because "it was no longer possible to use the route".208

(112) LDZ explained that it did not request a regulatory authorisation to operate independently on the whole territory of Lithuania because its staff and rolling stock are fully employed in Latvia. Consequently it "did not think there was a realistic opportunity to enter the Lithuanian market in other routes".209

(113) The regulatory authorisation for LDZ to operate independently on the Latvian border – Radviliškis route was issued at the beginning of 2012210 but since then LDZ has not provided such services,211 although it does provide traction services in Lithuania as a sub-contractor of LG (and these are the only services it provides in Lithuania).212 LG remains until today the only operator providing independent rail services in Lithuania.213

5. REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

5.1. Union legislation

(114) Since the early 1990s, the Union has adopted several legislative measures aimed at liberalising the European rail industry, notably the three railway legislative packages adopted in the 2000s. Railway infrastructure is considered a natural monopoly and before liberalisation, a single state-owned undertaking managed the railway infrastructure and also provided rail transport services in almost all Member States. New entrants are usually dependent on the historical, vertically integrated, rail operators ("incumbents") for access to upstream railway infrastructure services while at the same time also competing with the incumbents downstream in the provision of rail transport services. The challenge for Union legislation was not only to grant railway undertakings a right to operate in other Member States but also to ensure that they would be able to exercise that right effectively vis-à-vis the incumbents. Union legislation endeavoured therefore to mitigate the conflict of interest inherent in the activities of the incumbents.

5.1.1. Licensing and safety certificates

(115) In its amended version, applicable at the time of the relevant facts in this Decision, Article 3 of Directive 95/18/EEC214 provided that in each Member State the body responsible for issuing licences for railway undertakings should be independent from bodies or undertakings that provide rail transport services. Article 4(5) of that Directive stated that such licences were to be valid throughout the territory of the Union, but its Article 4(4) clarified that such licences did not, in themselves, entitle the holder to access the railway infrastructure.215

(116) Article 10(1) of Directive 2004/49/EC216 provides that, in order to be granted access to the railway infrastructure, a railway undertaking must hold a safety certificate. the safety certificate may cover the whole railway network of a Member State or a defined part of it. The safety certificate is to be issued by a national safety authority that should be independent in its organization, legal structure and decision making from any railway undertaking and infrastructure manager (Article 16(1) of that Directive).

5.1.2. Directive 91/440/EEC217

(117) Article 10 of Directive 91/440/EEC liberalised all types of rail freight services in the Union as of 1 January 2007, granting railway undertakings established in the Union access to the railway infrastructure on equitable conditions for the purpose of operating such services in all Member States. In its amended version applicable at the time of the relevant facts in this Decision, Article 6(1) of Directive 91/440/EEC provided that separate profit and loss accounts and balance sheets must be kept and published for infrastructure management, on the one hand and rail transport services, on the other, and public funds paid to one of those two areas of activity may not be transferred to the other. Article 6(3) of Directive 91/440/EEC required the Member States to ensure that the essential function of determining equitable and non- discriminatory access to infrastructure (licensing, path allocation, infrastructure charging) is entrusted to bodies or firms that do not themselves provide any rail transport services218.

5.1.3. Directive 2001/14/EC219

(118) In its amended version applicable at the time of the relevant facts in this Decision, Article 4(2) of Directive 2001/14/EC provides that where the infrastructure manager is not independent of a railway undertaking, the functions relating to setting infrastructure charges must be performed by a separate and independent body. Article 4(5) of that Directive instructs that the application of the charging scheme must result in equivalent and non-discriminatory charges for different railway undertakings performing services of equivalent nature.

(119) Article 5 of Directive 2001/14/EC and its Annex II set out four categories of service to be supplied to railway undertakings: i) the "minimum access package", to which there is a right of equal access on a non-discriminatory basis to operate trains on the network (Annex II, point 1); ii) "track access to service facilities" (for example stations, terminals and yards) and "supply of services", to which access should be provided in a non-discriminatory manner and requests by railway undertakings may only be rejected if viable alternatives under market conditions existed (Annex II, point 2); iii) "additional services" which are provided in those service facilities (Annex II, point 3.c) and which the infrastructure manager had to provide upon request. Regarding those services, Article 5(3) of Directive 2001/14 did not set a non-discrimination obligation; and iv) "ancillary services" (access to telecommunication network, provision of additional information and technical inspection of rolling stock) which the infrastructure manager is not obliged to provide (Annex II, point 4).

(120) Article 7 of Directive 2001/14/EC laid down the principles of infrastructure charging. According to Article 7(3) of Directive 2001/14, access to railway infrastructure and service facilities must be charged at the cost that is directly incurred as a result of operating the train service. Charges for services provided at the service facilities are not covered by that Article but, in setting them, account has to be taken of "the competitive situation of rail transport" (Article 7(7)). Charges for additional and ancillary services (points (iii) and (iv) in the previous paragraph) must relate to their cost where they are offered by only one supplier (Article 7(8)).

(121) Article 11 of Directive 2001/14/EC set the principle of the proper performance of the railway infrastructure. According to this Article, infrastructure charging schemes must, through a performance scheme, encourage railway undertakings and the infrastructure manager to minimise disruption and improve the performance of the railway network. It may include penalties for actions which disrupt the operation of the network, compensation for undertakings which suffer from disruption and bonuses that reward better than planned performance.

(122) Article 20(1) of Directive 2001/14/EC provided that "the infrastructure manager shall as far as is possible meet all requests for infrastructure capacity including requests for train paths crossing more than one network, and shall as far as possible take account of all constraints on applicants, including the economic effect on their business." Article 29 of that Directive stated further that "in the event of disturbance to train movements caused by technical failure or accident the infrastructure manager must take all necessary steps to restore the normal situation."

(123) Article 14(1) of Directive 2001/14/EC stated the principle of fair and non- discriminatory allocation of infrastructure capacity.220 Article 14(2) of Directive 2001/14 reiterated the requirement of the independence of the capacity allocation function from any railway undertaking.

(124) Article 30 of Directive 2001/14/EC required Member States to establish a national railway regulatory body independent of any infrastructure manager. The national railway regulatory body is to act as an appeal body against the decisions or conduct of the infrastructure manager, and is to supervise the charges set by the infrastructure manager.

5.1.4. The recast Directive 2012/34/EU 221

(125) Directive 2012/34/EU, which was to be transposed by the Member States by 16 June 2015 without prejudice to the obligations of the Member States relating to the time limits for transposition into national law of the Directives it recasts (namely Directives 91/440/EEC and 2001/14/EC), clarified some of the provisions of the Directives from the "First Railway Package" of 2001 and strengthened in certain respects the separation between infrastructure management and rail transport operations. The list of services to be supplied to the railway undertakings laid down in Annex II was updated. Most notably it was clarified that track access to service facilities also includes the services supplied in those facilities. Where these services are provided by an undertaking that holds a dominant position in the national rail transport services market, they must be provided by an independent body or firm (Article 13(3) of Directive 2012/34/EU). Requests by railway undertakings for access to these services must be answered within a reasonable time limit and may only be refused if there are viable alternatives (Article 13(4) of Directive 2012/34/EU). Additional services (i.e. the third category) are also to be provided in a non-discriminatory manner (Article 13(7) of Directive 2012/34/EU).

(126) Charges imposed for track access within service facilities (second category), which were not regulated in the First Railway Package, are now not to exceed the cost for providing it, plus a reasonable profit (Article 31(7) of Directive 2012/34). Similarly, charges imposed for additional and ancillary railway services offered by one supplier (third and fourth categories) should not exceed their cost, plus a reasonable profit.

5.2. Lithuanian legislation

5.2.1. Ownership of infrastructure

(127) In Lithuania the public railway infrastructure is owned by the state222 and entrusted to LG for management.223 In accordance with Article 15 of the Railway Transport Code,224 the list of railway lines are established in a government resolution for railway lines of national importance225 and an order of the Minister for Transport and Communications for railway lines of regional importance.226 LG manages the public infrastructure through a separate sub-division within the company.227 LG is required to ensure proper and safe maintenance of the public railway infrastructure in Lithuania and, in the event of an accident to take all necessary measures to restore the normal situation.228 Decisions regarding construction, conservation and closure (liquidation) of the public railway infrastructure remain solely at the hands of the state and cannot be taken by LG.229 LG's position is that the Track is not “closed” but rather that traffic is suspended until renovation works will be performed. The Track is still listed in the order of the Minister of Transport and Communications and appears in the Network Statement of LG.

5.2.2. Funding