Commission, January 24, 2018, No 40220

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

Qualcomm (Exclusivity payments)

COMMISSION DECISION of 24.1.2018

relating to proceedings under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article 54 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area

AT.40220 – Qualcomm (Exclusivity payments)

(Text with EEA relevance) (Only the English text is authentic)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union1, Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty,2 and in particular Articles 7(1) and 23(2) thereof,

Having regard to the Commission Decision of 16 July 2015 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given the undertaking concerned the opportunity to make known its views on the objections raised by the Commission pursuant to Article 27(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 and Article 12 of Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 of 7 April 2004 relating to the conduct of proceedings by the Commission pursuant to Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty3,

After consulting the Advisory Committee on Restrictive Practices and Dominant Positions, Having regard to the final report of the Hearing Officer in this case,

Whereas:

1. INTRODUCTION

(1) This Decision establishes that Qualcomm Inc. ("Qualcomm") infringed Article 102 of the Treaty and Article 54 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area ("the EEA Agreement") by granting payments to Apple Inc. ("Apple") on condition that Apple obtain from Qualcomm all of Apple's requirements of baseband chipsets compliant with the Long-Term Evolution ("LTE") standard together with the Global System for Mobile Communications ("GSM") and the Universal Mobile Telecommunications System ("UMTS") standards.

2. THE UNDERTAKINGS CONCERNED

2.1.Qualcomm

(2) Qualcomm is a developer of wireless technology products and services which has its headquarters in San Diego, California (United States of America).

(3) Qualcomm holds essential intellectual property rights ("IPR") in a number of cellular communications standards including the third generation ("3G") UMTS and the fourth generation ("4G") LTE standards and is a supplier of chips and chipsets used in mobile handsets and other devices.

(4) Qualcomm conducts business primarily through its business units Qualcomm CDMA Technologies and Qualcomm Technology Licensing, which are operated by Qualcomm and its direct and indirect subsidiaries.4

2.2. Interested Third Persons

(5) The Commission has heard Apple and Nvidia Corporation ("Nvidia") as interested third persons pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 773/2004.

(6) Apple is a US-based corporation established in 1977 which designs, manufactures and markets mobile communication and media devices, personal computers and portable digital music players, and sells a variety of related software.

(7) Nvidia is a US-based manufacturer of graphics processing units as well as of system- on-a-chip units for the mobile computing sector.

3. PROCEDURE

(8) In August 2014, the Commission started an ex officio investigation into arrangements relating to the purchase and use of Qualcomm's baseband chipsets.

(9) Between 12 August 2014 and 23 July 2015, the Commission sent requests for information pursuant to Articles 18(2) and 18(3) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 to Qualcomm, its customers and its competitors.

(10) On 16 July 2015, the Commission initiated proceedings against Qualcomm with a view to adopting a decision under Chapter III of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003.

(11) On 3 September 2015, the Commission held a State of Play meeting with Qualcomm. The services of the Directorate General of Competition also met with Qualcomm on 29 September 2015.

(12) On 8 December 2015, the Commission issued a statement of objections to Qualcomm ("Statement of Objections"). The Commission reached the preliminary conclusion that, absent any objective justification or efficiency gains, the payments granted by Qualcomm to Apple on condition that Apple obtain from Qualcomm all of its requirements of baseband chipsets compliant with the UMTS and LTE standards constituted an abuse of a dominant position under Article 102 of the Treaty and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement.

(13) On 21 December 2015, the Commission provided Qualcomm with documents saved on an electronic storage device by means of access to the Commission's file in accordance with Article 27(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 and Article 15 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004.

(14) The Commission originally set a time-limit of three months within which Qualcomm could submit a response to the Statement of Objections. At the request of Qualcomm, the Commission extended the time-limit by an additional month. On 15 April 2016, the Hearing Officer, in the light of Qualcomm’s various submissions on access to the Commission's file and on the deadline for Qualcomm’s response, suspended the running of the time period for responding in writing to the Statement of Objections. On 27 May 2016, the Hearing Officer lifted that suspension and granted an additional period for Qualcomm to submit its response, bringing the deadline for that response to 23 June 2016. After another extension request from Qualcomm, the Hearing Officer revised that deadline to 27 June 2016.

(15) On 27 June 2016, Qualcomm submitted its response to the Statement of Objections ("Response to the Statement of Objections"). Qualcomm did not request the opportunity to express its views at an oral hearing pursuant to Article 12(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004.

(16) On 28 June 2016 and again on 30 June 2016, Qualcomm’s lawyers submitted ‘confidential substantive submissions’ on behalf of Qualcomm in relation to certain documents whose confidential versions they had examined in restricted access procedures ordered by the Hearing Officer.

(17) On 27 July 2016, Qualcomm submitted a note entitled ‘The efficiency rationale of the Transition Agreement between Apple and Qualcomm’.

(18) On 15 March 2016 and on 31 March 2016, the Commission informed Apple and Nvidia respectively of the nature and subject matter of the proceedings by providing them with a non-confidential version of the Statement of Objections. Apple made known its views in writing on 2 May 2016. Nvidia made known its views in writing on 31 May 2016.

(19) Between 22 November 2016 and 5 May 2017, the Commission sent requests for information pursuant to Article 18(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 to Qualcomm, its competitors and Apple.

(20) On 19 October 2016, the Commission provided Apple with a non-confidential version of the Response to the Statement of Objections. Apple made known its views in writing on 21 November 2016.

(21) On 10 February 2017, the Commission sent Qualcomm a letter informing it about pre-existing evidence to which Qualcomm already had access but which was not expressly relied upon in the Statement of Objections but which, on further analysis of the Commission's file, could be relevant to support the preliminary conclusion reached in the Statement of Objections. The Commission also informed Qualcomm about additional evidence obtained by the Commission after the adoption of the Statement of Objections ("Letter of Facts").

(22) On 13 February 2017, the Commission granted Qualcomm further access to its file in relation to all documents that the Commission had obtained after the Statement of Objections up to the date of the Letter of Facts.

(23) The Commission originally set a deadline of 3 March 2017 for Qualcomm to submit a response to the Letter of Facts. At the request of Qualcomm, the Commission extended the response period by an additional ten days. After a further extension request of Qualcomm, the Hearing Officer maintained the deadline of 13 March 2017.

(24) On 13 March 2017, Qualcomm submitted its response to the Letter of Facts ("Response to the Letter of Facts").

(25) On 30 June 2017, the services of the Directorate General of Competition met with Qualcomm.

4. QUALCOMM’S CLAIMS OF PROCEDURAL IRREGULARITIES

(26) Qualcomm claims that the Commission has infringed its rights of defence due to a number of procedural irregularities.5

(27) First, Qualcomm claims that the confidentiality redactions applied to certain documents in the Commission's file have been excessive and unwarranted, with the result that Qualcomm has not been granted access to all the documents in the Commission's file that may be relevant for its defence.6

(28) Second, Qualcomm claims that it has had insufficient time to prepare its Response to the Statement of Objections and to the Letter of Facts.7

(29) Third, Qualcomm claims that the Commission should have requested Apple to provide all internal documents comparing different baseband chipset suppliers and leading to the selection of Qualcomm as Apple's chipset supplier between 2011 and 2015.8

(30) For the reasons set out in the following, the Commission considers that Qualcomm's rights of defence have been respected throughout the investigation.

(31) First, the Commission struck an appropriate balance between the proper exercise of Qualcomm’s rights of defence and the right of information providers to protect their business secrets and other confidential information.9

(32) On the one hand, Qualcomm was granted access to non-confidential versions of the documents in the Commission's file. In addition, Qualcomm's advisors were granted further access to entirely unredacted or less redacted versions of certain documents in the context of data room procedures,10 and access to certain documents [Procedural issues].11

(33) On the other hand, the documents to which further access was granted in the context of the data room procedures and [Procedural issues] contained business secrets and other confidential information within the meaning of Article 339 of the Treaty, Article 27(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, and Articles 15(2) and 16(1) of the Commission Regulation (EC) 773/2004.

(34) Second, the period of six months and six days that Qualcomm had to prepare its Response to the Statement of Objections and the period of one month and three days that Qualcomm had to prepare its Response to the Letter of Facts were, in light of the complexity of the case,12 sufficient to allow Qualcomm to exercise its rights of defence.

(35) In the first place, the Statement of Objections was only 77 pages long.

(36) In the second place, the Commission's file containing all the documents that the Commission had obtained prior to the Statement of Objections was not particularly voluminous and consisted mainly of agreements between Qualcomm and third parties.

(37) In the third place, on 21 December 2015, Qualcomm was given access to non- confidential versions of all documents in the Commission's file, except for 21 documents from Apple and 106 documents from […].13

(38) The Commission's conclusion that the time granted to Qualcomm to prepare its Response to the Statement of Objections and Response to the Letter of Facts was sufficient to allow Qualcomm to exercise its rights of defence is not contradicted by the fact that the Commission provided Qualcomm with access to non-confidentialversions of these 21 documents from Apple and 106 documents from […] on 19 February 2016 and on 3 March 2016 respectively. This is because:

(1) In the case of Apple, following a request by Qualcomm on 29 January 2016, the Commission contacted Apple and obtained non-confidential versions of the 21 documents,14 which were provided to Qualcomm on 19 February 2016;15 and

(2) In the case of […], following a request by Qualcomm on 29 January 2016, the Commission contacted […] and obtained non-confidential versions of the 106 documents, which were provided to Qualcomm by email of 3 March 2016.16

(39) In the fourth place, and in any event, any delay in providing access to certain documents was taken into account by the Hearing Officer when a subsequent extension of the time-limit for Qualcomm to respond to the Statement of Objections was granted.17

(40) In the fifth place, the fact that, following Qualcomm's requests, the Commission provided it on an ongoing basis with less redacted non-confidential versions of certain documents is not out of the ordinary in investigations in competition matters.18

(41) In the sixth place, the fact that Qualcomm was notified on the same day of two different Statements of Objections relating to two separate investigations19 was taken into account by the Commission when setting the original time period for Qualcomm to respond to both Statements of Objections.

(42) In the seventh place, it is clear from the Response to the Statement of Objections and the Response to the Letter of Facts that Qualcomm was able to make known its views in an effective manner. In particular, Qualcomm gave a detailed exposition of its views on each essential allegation made by the Commission.20

(43) In the eighth place, the Letter of Facts was only 30 pages long and the Commission's file containing all the documents that the Commission had obtained after the Statement of Objections up to the date of the Letter of Facts was not particularly voluminous. In addition, it consisted mainly of Qualcomm's Response to the Statement of Objections and responses to a Commission request for information regarding production and sales volumes of baseband chipsets.21

(44) Third, the Commission was not required to obtain from Apple all internal documents comparing different baseband chipset suppliers leading to the selection of Qualcomm as Apple's chipset supplier between 2011 and 2015. The Commission has already obtained from Apple a significant amount of internal documents, which, together with the Apple's responses to the requests for information, the Commission considers sufficient for the purposes of its investigation.

5. STANDARDS, STANDARD-SETTING ORGANISATIONS AND STANDARD ESSENTIAL PATENTS

5.1. Standards

(45) Standards ensure compatibility and interoperability between related products. This has many benefits.22 Standards can encourage innovation and lower costs by increasing the volume of manufactured products. Standards can strengthen competition by enabling consumers to switch more easily between products from different manufacturers. Standards may also further the Treaty objective of achieving the integration of national markets through the establishment of an internal market. The European Union has accordingly promoted standardisation as a tool for European competitiveness.23

5.2.Standard-setting organisations

(46) Standard-setting organisations are organisations whose primary activity is to develop and maintain standards by bringing together industry participants to evaluate competing technologies for inclusion in standards.

(47) Standard-setting organisations also seek to ensure that industry participants contribute technology that will create valuable standards and that these standards are widely adopted. The broader the implementation of a standard, the greater the interoperability benefits.

(48) Participants in a standard-setting process can obtain significant benefits if their technology becomes part of a standard. These include potential royalties from licensees, a large base of licensees, increased demand for their products and improved compatibility with other products using the standard.

(49) The European Union and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) have recognised three standard-setting organisations as official European standardisation bodies:24the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN), the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardisation (CENELEC) and the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI).25

5.3.Standard essential patents

(50) Standards frequently make reference to technologies that are protected by patents, especially in industries such as telecommunications. Hundreds or even thousands of patents may relate to a single standard. Thus, when a user of a standard (also known as an "implementer") manufactures standard-compliant products, it cannot avoid the use by its products of technologies that are covered by such patents.

(51) Patents that are essential to a standard are those that cover technology to which a standard makes reference and that implementers of the standard cannot avoid using in standard-compliant products. These patents are known as standard-essential patents (SEPs). SEPs are different from patents that are not essential to a standard. This is because it is generally technically possible for an implementer to design around a non-essential patent in order to comply with a standard. By contrast, an implementer has to use the technology protected by a SEP when manufacturing a standard-compliant product.

(52) The major standard-setting organisations in the field of wireless communications namely ETSI, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers ("IEEE") and the International Telecommunications Union ("ITU") require their members to license their SEPs on (fair,) reasonable and non-discriminatory ("(F)RAND") terms.

6. THE TECHNOLOGY AND PRODUCTS CONCERNED BY THE DECISION

(53) This Decision concerns baseband chipsets that implement and comply with the LTE standard of cellular communication technology.

(54) Cellular communication technology allows communication by means of cellular network, which is a radio network distributed over land through cells, where each cell includes a fixed location transceiver known as a base station. These cells together provide radio coverage over larger geographical areas. Cellular user equipment, such as mobile phones, is therefore able to communicate even if the equipment is moving through those cells during transmission.

(55) In this Decision, the following definitions apply:

(1) "UMTS-compliant chipsets" means baseband chipsets that implement and comply with the UMTS cellular communications standard;

(2) "LTE-compliant chipsets" means baseband chipsets that implement and comply with the LTE cellular communications standard;

(3) "LTE chipsets" means baseband chipsets that comply with all of the following standards: GSM, UMTS and LTE;

(4) "UMTS chipsets" means baseband chipsets that comply with both the GSM and UMTS standards but not with the LTE standard;

(5) "GSM chipsets" means baseband chipsets that comply with the GSM standard but not with the UMTS and LTE standards; and

(6) "Single-mode LTE chipsets" means baseband chipsets that comply only with the LTE standard but not with the GSM and UMTS standards.

6.1. The evolution of cellular communication standards

6.1.1. GSM

(56) GSM is a standard developed by ETSI to describe technologies for second generation ("2G") digital cellular networks. Developed as a replacement for first generation analogue cellular networks, the GSM standard originally described a network optimised for voice telephony. The standard was expanded over time to include packet data transport via General Packet Radio Services ("GPRS") and Enhanced Data rates for GSM Evolution ("EDGE"). Later technology generations build on the principles established by this standard.

(57) In this Decision, references to GSM include GPRS and EDGE.

6.1.2. UMTS

(58) UMTS is a 3G cellular communications standard capable of supporting multimedia services, beyond the capability of 2G systems such as GSM.

(59) The beginning of the UMTS standard-setting process dates back to the early 1990s when the concept of UMTS emerged from European research programmes. ETSI established a technical working group26 in 1992 specifically to investigate the UMTS concept. By January 1998, the decision was made to adopt two alternative technologies, Wideband-Code Division Multiple Access ("W-CDMA") and Time Division -(Synchronous) Code Division Multiple Access ("TD-(S)CDMA"),27 as options for the radio part of the UMTS standard.

(60) In December 1998, following a decision of the ETSI General Assembly, the work on UMTS was moved to a new group which included delegations from the US, South Korea and Japan as full members. It became known as the 3rd Generation Partnership Project or "3GPP". The aim of 3GPP was to create a globally applicable 3G cellular communications standard.

(61) In December 1999, 3GPP completed what was known as "Release 99". This marked the first iteration of the UMTS standard. Release 99 was then transposed by ETSI into formal European standards throughout 2000. In line with the requirements of Decision 128/1999/EC,28 the UMTS standard was implemented in most Member States in the Union during the following years.

(62) 3GPP has further evolved the W-CDMA variant of UMTS in order to provide improved characteristics, including higher data rates. Notable evolutions of W- CDMA include High Speed Packet Access ("HSPA")29, HSPA+30 and Dual Carrier HSPA.31 These evolutions formed part of subsequent 3GPP Releases.

(63) The major breakthroughs in the market evolution of UMTS-compliant baseband chipsets are related to the support of increasingly high data rates of broadband connectivity. Before the development of HSPA technology, UMTS supported data rates up to 0.384Mbps, which was inadequate to support typical broadband applications like full internet browsing and video streaming. HSPA technology (3GPP Release 4 and 3GPP Release 5) enabled data rates up to 3.6Mbps. Subsequent iterations of HSPA+ in 3GPP Releases 7 and 8 increased the data rates even further to 28Mbps and 42Mbps respectively.

(64) In this Decision and for the purposes of convenience, unless otherwise specified,32 the term UMTS will be used to describe only the W-CDMA variant of the radio interface as well as its evolutions such as HS(D/U)PA, HSPA+ and Dual Carrier HSPA. These technologies are also known as UMTS Frequency Division Duplexing ("UMTS-FDD").33

6.1.3. LTE

(65) LTE is an orthogonal frequency-division multiple access ("OFDMA") technology that increases the capacity and speed of GSM and UMTS by using a different radio interface together with core network improvements. This standard was developed by 3GPP.

(66) LTE is commonly referred to as a 4G standard, although strictly speaking the requirements set for 4G are satisfied only by its later iterations (known as LTE- Advanced or LTE-A).

(67) The maximum downlink data rate supported by LTE increased about 260-fold compared to the first iterations of the UMTS standards (from 0.384 Mbps to 100 Mbps). This facilitates faster browsing experience, file downloads, music and video streaming, etc.

(68) In this Decision, the term LTE will be used to refer to LTE, LTE-A, and further iterations of the LTE technology.

6.1.4. Other cellular and wireless communication standards

(69) In addition to GSM, UMTS and LTE, there are other cellular communication standards such as Code Division Multiple Access ("CDMA"). There are also standards for wireless communication which do not make use of cellular technology, such as Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access ("WiMAX") and Wireless Local Area Network ("WLAN"), also commonly called WiFi.

(70) These standards are standardised by standard-setting organisations like the Third Generation Partnership Project 2 ("3GPP2")34 and the IEEE.

6.2. Baseband chipsets

(71) Baseband chipsets are part of the mobile communications industry, which has experienced high growth over the last two decades.35 An important factor in the growth of the baseband chipset sales has been the steady increase in smartphone adoption.36

6.2.1. Functions

(72) Mobile devices such as smartphones, tablets, portable PCs and e-book readers require mobile broadband37 connectivity to the internet through cellular mobile telecommunication networks ("mobile networks").

(73) The core component providing mobile connectivity in a device is the baseband processor. Its main task is to perform the signal processing functionality according to communication protocols described by cellular communications standards. Baseband processors can be embedded directly in mobile devices, or in external modules such as a USB stick, which is also called a "dongle", and which are in turn plugged into a device.

(74) A baseband processor typically consists of both hardware and software. The hardware consists of an integrated circuit, made of semiconductor material, known as "silicon die", and packaged into a baseband chip using ceramic or plastic material.

(75) In addition to the baseband processor, certain types of mobile devices require an application processor, used for running the operating system and applications (including messaging, internet browsing, imaging and games). This application processor can either be provided as a standalone product, packaged into a separate chip or can be integrated with the baseband processor into the same silicon die and packaged into the same chip.

(76) Based on this distinction, baseband chips can be divided into two categories:

(1) Standalone baseband chips, where no application processor is included; and

(2) Integrated baseband chips, where the baseband processor has been integrated with an application processor, usually onto a single silicon die, and is packaged in the same chip.

(77) Regardless of the presence of an application processor, a baseband processor is typically paired with two additional components to complete its functionality, namely the Radio Frequency (RF) integrated circuit, also known as RF transceiver,38 and the Power Management (PM) integrated circuit.39 All three functionalities (baseband processor, RF transceiver and PM circuitry) are necessary for mobile connectivity and their resulting combination is called a "baseband chipset".40 The three components of baseband chipsets are usually obtained from the same supplier, either as a bundle or separately.41

(78) In this Decision, the term "integrated baseband chipset(s)" or simply "integrated chipset(s)" will be used for chipsets that include an integrated baseband chip. The term "standalone baseband chipset(s)" or "slim modem(s)" will be used for chipsets that include a standalone baseband chip without an application processor.

(79) Baseband chipsets, whether standalone or integrated, implement one or multiple cellular and wireless communications standards, from the same or from different technology families and generations. For example, a baseband chipset might implement only the GSM standard or it might implement a combination of the GSM, UMTS and LTE standards (see in more detail Section 8.2.3).

(80) Baseband chipsets of a given generation tend to be backwards compatible with earlier cellular communication technology of the same technology family. For example, UMTS-compliant chipsets generally provide support for GSM.42 In addition, the vast majority of LTE-compliant chipsets also provide support for UMTS and GSM.43

6.2.2. Customers and applications

(81) Baseband chipsets are typically sold to original equipment manufacturers ("OEMs" – also called "device manufacturers"), which incorporate them into devices that make use of mobile connectivity. OEMs include Apple, HTC Corporation ("HTC"), Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. ("Huawei"), LG Corp ("LG"), Samsung Group ("Samsung") and ZTE Corporation ("ZTE").

(82) OEMs incorporate baseband chipsets in a variety of devices, which can be grouped in two broad categories:

(a) Mobile phones (also called "handsets"), usually further classified into:

(1) Basic phones (phones providing only basic functionality like voice and messaging);

(2) Feature phones (phones providing more advanced functionality, like multimedia applications and internet connectivity); and

(3) Smartphones (phones providing advanced functionality, comparable to the functionality provided by a personal computer).

(b) Mobile broadband devices, which cover devices with mobile connectivity, other than mobile phones, and include in particular:

(1) Tablets with cellular access;44

(2) Data cards with cellular access, typically in the form of USB sticks (also called "dongles");

(3) Wireless routers that rely on cellular networks to act as WiFi hotspots, also called "MiFi" devices; and

(4) Other devices (for example, laptops) using embedded modules with cellular access.

(83) While all of these devices incorporate baseband chipsets, they do not all require the exact same functionalities.

(84) Voice telephony is an important requirement for mobile phones. Mobile phones typically use a number of interoperable technologies in order to provide a seamless voice experience to users. For many European mobile networks, in the period from 25 February 2011 to 16 September 2016 ("the Period Concerned"), this would have meant the capability to use both GSM and UMTS technologies for traditional voice telephony.45

(85) By contrast, the main purpose of cellular access in mobile broadband devices is broadband data connectivity, based on UMTS or LTE technology.46 These devices therefore do not provide traditional voice telephony, also called "circuit switched"47 voice, or do so only exceptionally.

6.2.3. Production process

(86) Baseband chipset suppliers typically design and develop their products themselves.48 The majority, however, do not manufacture (or "fabricate") them in their own facilities.49 Instead, they outsource the "fabrication" to specialised manufacturers called "foundries" which aggregate demand from multiple semiconductor suppliers. The baseband chipset suppliers that outsource the production of chipsets are called "fabless" suppliers.

6.2.4. Main suppliers

(87) Apart from Qualcomm, a number of other suppliers were active in the supply of UMTS- and LTE-compliant baseband chipsets in the Period Concerned.

6.2.4.1. Infineon / Intel

(88) Infineon Technologies AG ("Infineon") is a Germany-based company active in a range of semiconductor solutions.

(89) On 29 August 2010, Intel Corporation ("Intel"), a U.S. multinational, announced the acquisition of the wireless solutions business of Infineon,50 which included its baseband chipsets. The acquisition was completed on 31 January 2011.51 Since then, Intel has taken over and developed the business of Infineon in the baseband chipset space.

(90) Apple incorporated Infineon UMTS-compliant baseband chipsets in its iPhone and iPad devices launched before 2011.52

(91) Starting from the iPhone 7 devices launched on 16 September 2016, Apple started to incorporate also Intel LTE-compliant baseband chipsets in certain of its devices.53

(92) In October 2015, Intel acquired the CDMA business of Via Technologies Inc. ("Via").54 In February 2017, Intel announced its first baseband processor product that integrated Via’s CDMA technology with Intel’s own multi-mode processor technologies.55

6.2.4.2. ST-Ericsson / Ericsson

(93) ST-Ericsson NV ("ST-Ericsson") was a multinational manufacturer of wireless products and semiconductors which had its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland and which was established on 3 February 2009 as a 50/50 joint venture between Telefonaktiebolaget L. M. Ericsson ("Ericsson") and ST Microelectronics N.V. ("ST Microelectronics").56 ST-Ericsson supplied its baseband chipsets to OEMs such as Sony-Ericsson, Nokia57, LG and Samsung.

(94) The ST-Ericsson Joint Venture was dissolved on 2 August 2013,58 with its baseband assets being transferred to Ericsson.

(95) On 18 September 2014, Ericsson announced its intention to cease producing baseband chipsets.59

6.2.4.3. MediaTek

(96) MediaTek Inc. ("MediaTek") is a fabless semiconductor company for wireless communications and digital multimedia solutions headquartered in Taiwan.

(97) It is mainly focussed on the low- and mid-range segments of baseband chipsets and on sales in China.60 It started to produce UMTS-compliant chipsets in 2010 and LTE-compliant chipsets in 2014.61

(98) As of 2015, MediaTek began to offer CDMA processors on the basis of a CDMA technology licence from Via.62

6.2.4.4. Marvell

(99) Marvell Technology Group Ltd. ("Marvell") is a US-based fabless semiconductor supplier. It historically focused on the smartphone market, being the supplier of Blackberry Limited ("Blackberry").63

(100) On 24 September 2015, Marvell announced its intention to cease producing baseband chipsets.64

6.2.4.5. Huawei / HiSilicon

(101) HiSilicon Technologies Co., Ltd. ("HiSilicon") is a China-based fabless semiconductor supplier.65

(102) It is a 100% subsidiary of the Chinese device manufacturer Huawei and produces baseband chipsets […].66

6.2.4.6. Renesas

(103) Renesas Mobile Corporation was a wholly-owned subsidiary of Renesas Electronics Corporation ("Renesas"), headquartered in Japan. It was active in the design and development of platforms for mobile phones and other mobile devices. It mainly supplied Japanese OEMs such as Fujitsu, Sharp, NEC, Sony and Panasonic.67

(104) In 2010, Renesas expanded its activities in baseband chipsets by acquiring the baseband assets of Nokia.68

(105) In 2013, Renesas sold its baseband assets to Broadcom.69

6.2.4.7. Broadcom

(106) Broadcom Corporation ("Broadcom") is a US-based fabless semiconductor company that designs solutions for a broad range of wired and wireless communications markets. The company's customers included smartphone manufacturers like Samsung and Nokia.70

(107) In 2013, Broadcom acquired the baseband assets of Renesas.

(108) In July 2014, Broadcom announced its intention to cease producing baseband chipsets.71 Whilst Broadcom had been active in the supply of UMTS-compliant chipsets, it never supplied any LTE-compliant baseband chipsets.72

6.2.4.8. Samsung / LSI

(109) Samsung Systems LSI ("LSI") is a South Korean-based foundry semiconductor company that designs and manufactures baseband chipsets to be incorporated in mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets.

(110) LSI is a fully-owned subsidiary of Samsung and […].73

6.2.4.9. Nvidia

(111) Nvidia was active in the supply of baseband chipsets following its acquisition in 2012 of Icera Inc. ("Icera"), which was a UK-based manufacturer of baseband chipsets.

(112) In May 2015, Nvidia announced its intention to cease producing baseband chipsets.74

6.2.4.10.Sequans

(113) Sequans Communications S.A. ("Sequans") is a fabless semiconductor company based in France and specialising in the development of single-mode LTE chipset solutions.75 Its customers include Asus, HTC, Huawei and ZTE.76

6.2.4.11.Spreadtrum

(114) Spreadtrum Communications, Inc. ("Spreadtrum") is a fabless semiconductor company that develops mobile chipset platforms for smartphones, feature phones and other consumer electronics products, supporting 2G, 3G and 4G cellular communications standards. It was founded in April 2001 and is headquartered in Shanghai, China.77

(115) It is mainly focused on the low- and mid-range segments of baseband chipsets and on sales in emerging markets such as India, Southeast Asia, Africa and South America.78

7. QUALCOMM'S ACTIVITIES IN RELATION TO BASEBAND CHIPSETS

7.1.Product range

(116) Qualcomm has a broad product portfolio ranging from low- and mid-cost baseband chipsets for the mass market to leading-edge baseband chipsets implementing the latest standards.79 Being active also in the development of application processors, it offers both standalone and integrated chipsets.

(117) Qualcomm markets, or has marketed, its baseband chips (and by extension chipsets) mainly under the following product family names:80

(a) The Mobile Data Modem ("MDM") product family, which includes standalone baseband chips, namely baseband chips that mainly provide baseband processing (connectivity);

(b) The Mobile Station Modem ("MSM") product family, which includes integrated baseband chips, namely chips that provide both application processing and baseband processing (connectivity);

(c) The Qualcomm Single Chip ("QSC") product family, which includes integrated baseband chips. QSC products incorporate the RF and PM functionalities in the same chip, in addition to the baseband and application processors;81 and

(d) The Qualcomm SnapDragon ("QSD") product family, which includes a specific range of integrated chips, featuring a "Snapdragon" application processor. The QSD designation was withdrawn in 2010 and replaced by MSM.

7.2. Qualcomm's participation in the standardisation of cellular communications standards

(118) Qualcomm develops, commercialises and actively supports 3G and 4G cellular communication technologies, including CDMA2000, WCDMA, HSDPA, HSUPA, HSPA+, TD-SCDMA and LTE.

(119) Qualcomm invests large amounts in research and development expenditure. In the fiscal years 2011 to 2014, Qualcomm's investments amounted to USD 3.0 billion USD 3.9 billion, USD 5.0 billion and USD 5.5 billion respectively.82

(120) As explained in Sections 7.2.1 to 7.2.3, Qualcomm played an important role in the development of cellular communications technology standards, and in particular CDMA, UMTS and LTE.

7.2.1. CDMA

(121) In 1986, Qualcomm filed its first patent application in the area of CDMA technology. This patent, together with other patents, would become the basis of CDMA technologies in mobile networks.83

(122) According to Qualcomm, "[o]ther companies had invested vast sums in developing TDMA technologies (including GSM) and argued that CDMA was technically and commercially impossible to develop. Qualcomm developed a complete end-to-end system, including infrastructure and handset equipment, to ensure the early supply of CDMA equipment and to demonstrate that CDMA technology actually worked".84

(123) In 1990, Qualcomm's early funding agreements and licenses with AT&T and Motorola established the framework for subsequent licences. In this way, the CDMA technology was successfully tested. In 1993, one year after Qualcomm's first licence agreement with Nokia, the Telecommunication Industry Association adopted and published the IS-95 CDMA Standard, based on Qualcomm's technology. In the meantime, Qualcomm entered into licence agreements with Matsushita (Panasonic),Samsung, LG, Hyundai and NEC. 85

(124) To date, Qualcomm leads the development of CDMA-based technologies.86 Qualcomm owns a large portfolio of IPR applicable to products that implement any version of CDMA, including patents, patent applications and trade secrets.87 The mobile communications industry generally recognises that a company seeking to develop manufacture and sell products that use CDMA technology will require a patent licence from Qualcomm.88

(125) Until 2015, Qualcomm was one of two suppliers active in the production of CDMA chipsets. The other, Via, did not supply any LTE chipsets during the Period Concerned.89 In 2015, MediaTek began also supplying CDMA chipsets.

7.2.2. UMTS

(126) Qualcomm also had a strong impact on the development of UMTS technology, namely on the WCDMA standard. UMTS is a 3G CDMA-based technology, and Qualcomm owned an extensive IPR portfolio in relation to CDMA.

(127) According to Qualcomm, "WCDMA […] is based on [its] underlying CDMA technology"[…].90 Qualcomm explained that "[a]s second-generation (2G) networks make the transition to advanced wireless systems, the WCDMA (UMTS) market [was] gaining impressive momentum, presenting an additional opportunity for [Qualcomm]. As of November 2006, there were more than 90 million WCDMA subscribers worldwide.[…]"91 Qualcomm stated that "[its] expertise and continued innovation in CDMA technology have brought [it] to a leading position in both CDMA2000 and WCDMA next-generation innovations."92

(128) Moreover, "[l]everaging [its] expertise in CDMA, [Qualcomm has] also developed integrated circuits for manufacturers and wireless operators deploying the WCDMA version of 3G for manufacturers of wireless devices."93 As a result, "[t]he majority of the world’s wireless device and infrastructure manufacturers (more than 125 and including all leading suppliers) have licensed [its] technology for use in WCDMA products."94

7.2.3. LTE

(129) Qualcomm had a significant influence on the development of LTE technology.

(130) Already in 2006, Qualcomm announced that "[a]n optimised OFDMA system [which includes LTE] designed to provide high performance in a mobile environment, including advanced techniques such as MIMO" would have been commercialised as of 2010."95

(131) In 2007, Qualcomm stated that "[it] ha[s] also informed standards bodies that [it] may hold essential intellectual property rights for certain standards that are based on OFDMA technology, e.g. […] LTE."96

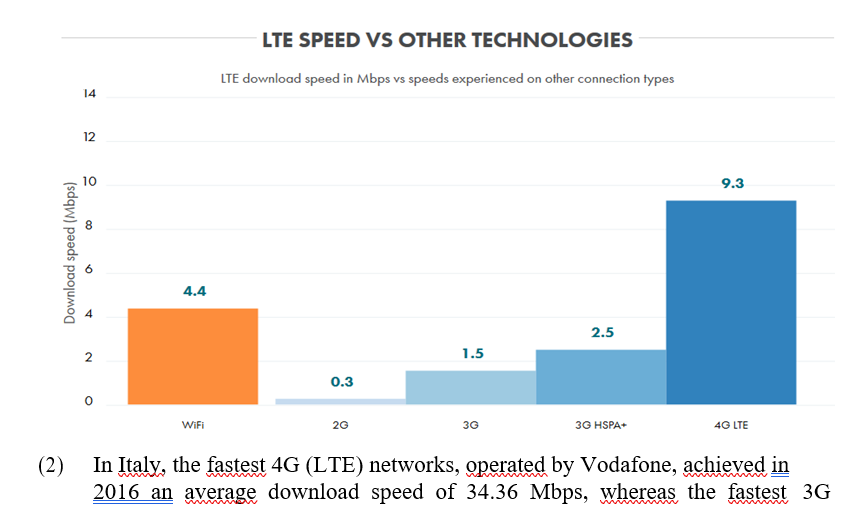

(132) In 2008, Qualcomm outlined that "[its] considerable expertise with OFDMA technology is now focused on the development of Qualcomm’s LTE program and the creation of innovative next generation air interface technologies."97 Still in 2011, Qualcomm declared that "[it] continue[s] to invest significant resources toward the development of technologies and products for voice and data communications, primarily in the wireless industry, including advancements to […] 4G LTE networks wireless baseband chips."98

(133) Still in 2014, Qualcomm continued "to play a significant role in the development of LTE and LTE Advanced, which are the predominant 4G technologies".99

7.3.Qualcomm's patent portfolio

(134) Qualcomm is the largest IPR holder active in the supply of baseband chipsets. As of 6 August 2015, it owned more than 100,000 distinct patents.100 [Qualcomm’s legal and business strategy].101

8. QUALCOMM'S AGREEMENTS WITH APPLE

(135) Apple incorporates baseband chipsets into its "iPhone" smartphones and its "iPad" tablets with cellular connection.

(136) Apple has outsourced all manufacturing processes in relation to iPhones and iPads to third party contract manufacturers.102

(137) Apple gives instructions to its contract manufacturers as to the components that they have to buy for incorporation into Apple end-products.103 These contract manufacturers are also referred to as "authorised purchasers".

(138) Apple has direct contracts with the suppliers of components for iPhones and iPads, but these suppliers ship and sell those components directly to the contract manufacturers for assembly into the finished products.104

(139) As regards the supply of Qualcomm baseband chipsets, on 16 December 2009, Apple concluded a framework agreement with Qualcomm, the Strategic Terms Agreement ("STA"), which amongst other things, contains certain terms and conditions relating to the sale of Qualcomm chipsets to authorised purchasers.105

(140) Pursuant to the STA, Apple and Qualcomm have entered into Statements of Works ("SOWs") setting out the terms and conditions for the supply of Qualcomm baseband chipsets, including the price of those chipsets. Pursuant to the SOWs, Qualcomm ships baseband chipsets directly to Apple’s contract manufacturers for assembly into Apple's iPhones and iPads. While contract manufacturers pay Qualcomm for baseband chipsets, Apple is then reimbursed by Qualcomm under the terms of the STA and each SOW for the difference between the price applicable between the contract manufacturer and Qualcomm, and the price agreed between Apple and Qualcomm.106

(141) In addition, Apple and Qualcomm entered into an agreement (the "Transition Agreement") on 25 February 2011.107 The Transition Agreement was amended on 28 February 2013 by means of a subsequent agreement (“the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement”).

(142) While the Transition Agreement, as amended by the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement (together, the "Agreements"), were scheduled to expire on 31 December 2016, for the purposes of this Decision it is considered that they terminated on 16 September 2016 pursuant to Clause 1.5A of the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement following Apple's launch of iPhone 7 devices incorporating Intel LTE chipsets. The content of the Agreements is outlined further in Sections 8.1 and 8.2.

8.1.The Transition Agreement

(143) The purpose of the Transition Agreement was to set out certain terms and conditions regarding the payment by Qualcomm to Apple of "certain funds related to Apple's transition to using Qualcomm Chipsets in Apple products (the "Transition")".108

(144) The Transition Agreement established three different payment schemes:

(1) the 4-Year Transition Fund;109

(2) the Marketing and Development Fund;110 and

(3) the Variable Incentive Fund.111

(145) Under the 4-Year Transition Fund, "in consideration of Apple's substantial resource investment associated with the Transition", Qualcomm committed to pay Apple USD[200-300] million in two instalments of USD [100-200] million each,112 the first on 31 March 2012 and the second on 31 March 2013.113

(146) If, however, during 2011, the volume of Qualcomm baseband chipsets that implement CDMA, UMTS and/or LTE used in Apple products did not meet a certain threshold, or if, during any quarter of 2012, the volume of UMTS-compliant baseband chipsets did not meet certain thresholds, Qualcomm was entitled to reduce the first or the second instalment of this payment respectively. Further, if during any quarter of 2013 or the first quarter of 2014, the volume of UMTS-compliant baseband chipsets did not meet certain thresholds, Apple would reimburse some of the previously paid 4-Year Transition Fund to Qualcomm.114

(147) Under the Marketing and Development Fund, designed "to contribute to the costs of Apple's marketing efforts", Qualcomm committed to pay USD [100-200] million in six quarterly instalments of USD [20-30] million dollars each. Each instalment was due before the end of each of six consecutive calendar quarters, beginning with the third quarter of 2011.115

(148) If, however, Apple did not launch at least one Apple product with a UMTS carrier that incorporated a Qualcomm baseband chipset by 31 December 2012, Apple would reimburse all payments previously paid pursuant to the Marketing and Development Fund.116

(149) Under the Variable Incentive Fund, "in consideration of Apple's use of Qualcomm Chipsets", Qualcomm committed to pay Apple up to USD [500-600] million in yearly payments of up to USD [100-200] million each, over four consecutive years. The exact value of each yearly payment was calculated by reference to a scale starting at USD [100-200] million to USD [100-200] million, depending on the volume of Qualcomm baseband chipsets incorporated in Apple products in the preceding twelve months. The applicable yearly volume requirements gradually increased over time. The lowest threshold that triggered the payment of USD [100- 200] million increased from [50-100] million units in 2012 to [100-200] million units in 2015, while the highest threshold that triggered the payment of USD [100-200] million increased from [100-200] million units in 2012 to [100-200] million units in 2015.117

(150) For example,118 the annual volume thresholds for 2014 and 2015119 were as follows:120

Table 1: Variable Incentive Fund annual volume thresholds for 2014 and 2015

Payment Amount | Annual Volume |

USD [100,000,000-200,000,000] | ≥ [100-200] million units |

USD [100,000,000-200,000,000] | ≥ [100-200] million and < [100-200] million units |

USD [100,000,000-200,000,000] | ≥ [100-200] million and < [100-200] million units |

USD [0-10,000,000] | < [100-200] million units |

(151) Qualcomm's commitment to make the payments envisaged under each the payment schemes referred to in recital (144) was subject to the conditions set out in Clause 1.5 of the Transition Agreement.121

(152) Clause 1.5 of the Transition Agreement stated: "if after October 1, 2011, Apple sells an Apple product commercially that incorporates a non-Qualcomm cellular baseband modem,122 this Agreement shall automatically terminate and Qualcomm shall not be obligated to make any of the payments that are due and payable after the date of such sale." In addition, if such sales took place in calendar year 2013, Apple would be liable to reimburse within 45 days both of the following:

(1) the second instalment of the Transition Fund; and

(2) the second instalment of the Variable Incentive Fund.123

(153) The provisions of Clause 1.5 were stated not to "apply to continued sales by Apple of any Apple product that incorporates a non-Qualcomm cellular baseband modem which Apple is selling commercially as of October 1, 2011 and minor modifications thereto but not including Major Releases.124"125 Apple could thus continue to sell any legacy products that incorporated Intel baseband chipsets.

8.2. The First Amendment to the Transition Agreement

(154) The First Amendment to the Transition Agreement took effect as of 1 January 2013.

(155) According to the recitals of the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement, Qualcomm entered into this amendment agreement because it wished "to provide additional marketing incentives to Apple in order to help drive demand for global sales of Apple Phones and Apple Tablets with advanced cellular technologies."126

(156) The First Amendment to the Transition Agreement established two different payment schemes, in addition to the three existing payment schemes referred to in recital (144), namely:

(1) the Marketing Fund;127 and

(2) the Additional Variable Incentive Fund.128

(157) Under the Marketing Fund, for the period 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2016 or upon the earlier termination of the Agreements,129 Qualcomm committed to pay USD [0-5] for each Apple phone sold at a price of at least USD [200-300]130 and USD [0- 5] for each Apple tablet sold at a price of at least USD [100-200] that incorporated a Qualcomm baseband chipset.131 Qualcomm would also pay the same amount for all Apple phones or all Apple tablets if these conditions were not met but if the quarterly average sale price of these devices reached USD [100-200] and USD [100-200] respectively.132 Payments were accounted on a quarterly basis133 but due 45 days after the end of each calendar year.134

(158) Clause 1.3A(c) of the Transition Agreement, as amended by the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement, provided, however, that "if […] Apple or any of its Affiliates [sold] a Non-QC Device [namely device incorporating a baseband chipset other than produced by Qualcomm] commercially (i.e., more than 1000 units)", Apple would be liable to reimburse either:

(1) All Marketing Fund amounts previously paid by Qualcomm in full, if such sales took place in calendar years 2013 or 2014; or

(2) All Marketing Fund amounts paid in the previous 15-month period, if such sales took place in calendar year 2015.135

(159) The provisions of Clause 1.3A(c) did not however apply to any continued sales of the iPhone 4 product that incorporated a non-Qualcomm baseband chipset and its minor modifications.136

(160) Under the Additional Variable Incentive Fund, Qualcomm committed to pay to Apple up to USD [300-400] million in yearly payments of up to USD [100-200]million each, in 2015 and 2016.137 The First Amendment to the Transition Agreement specified that these payments were in addition to any amounts due under the Variable Incentive Fund established by the Transition Agreement.138 The exact value of each yearly payment was calculated by reference to a scale starting at USD [100-200] million to USD [100-200] million, depending on the volume of Qualcomm baseband chipsets incorporated in Apple products in the preceding twelve months.139

(161) The annual volume thresholds for 2015 and 2016 were as follows:140

Table 2: Additional Variable Incentive Fund annual volume thresholds for 2015 and 2016

Payment Amount | Annual Volume |

USD [100,000,000-200,000,000] | ≥ [100-200] million units |

USD [100,000,000-200,000,000] | ≥ [100-200] million and < [100-200] million units |

USD [100,000,000-200,000,000] | ≥ [100-200] million and < [100-200] million units |

USD [0-10,000,000] | < [100-200] million units |

(162) Clause 1.3B(b) provided, however, that "if Apple or any of its Affiliates [sold] a non- QC device commercially (i.e. more than 1000 units)", Apple would be liable to reimburse either:

(1) The Additional Variable Incentive Fund payment of 2015, if such sales took place in calendar year 2015; or

(2) The Additional Variable Incentive Fund payment of 2016, if such sales took place in calendar year 2016. 141

(163) The provisions of Clause 1.3B(b) did not apply to any continued sales of the iPhone

4 product that incorporated a non-Qualcomm baseband chipset and its minor modifications.142

(164) The First Amendment to the Transition Agreement maintained the provisions regarding Apple’s reimbursement of certain funds envisaged in Clause 1.5 of the Transition Agreement (see Clause 5 of the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement). 143

(165) In addition, a new Clause 1.5A was added to the Transition Agreement by the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement, pursuant to which: "if during the Term Apple or any of its Affiliates [sold] a Non-QC Device commercially (i.e., more than 1000 units), this Agreement shall automatically terminate" and Qualcomm would not be required to make any of the payments that were otherwise due and payable after the date of such sale. This would include the payments envisaged by the Transition Agreement and those added by the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement.

(166) The provisions of Clause 1.5A were stated not to "apply to continued sales by Apple of any Apple product that incorporates a non-Qualcomm cellular baseband modem which Apple was selling commercially as of October 1, 2011 and minor modifications thereto but not including Major Releases."144

8.3. Summary of the Transition Agreement and the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement

(167) In summary, the Agreements provided that:

(a) Qualcomm would grant Apple certain payments, which include lump-sum, volume-based and per-device payments (collectively referred to as the "Incentive Payments");

(b) The Incentive Payments were conditional upon Apple obtaining from Qualcomm all of Apple's requirements of baseband chipsets:

(1) In the event that Apple commercially released a product that incorporated a non-Qualcomm baseband chipset, the Agreements would terminate and Qualcomm would not have to make any of the Incentive Payments that were otherwise due and payable after the date of such release (the "Termination Clause");145

(2) In the event that Apple commercially released a product that incorporated a non-Qualcomm baseband chipset between 2013 and 2015, Apple would be obliged to reimburse part of the Incentive Payments previously received from Qualcomm (the "Repayment Mechanism").146

8.4. LTE chipsets obtained by Apple during the Period Concerned

(168) During the period 2011 to 2015, Apple obtained LTE chipsets only from Qualcomm.147 The first Apple device to incorporate a Qualcomm LTE chipset was the third generation iPad which was launched in March 2012.148

(169) In 2016, Apple obtained LTE chipsets from both Qualcomm and Intel. The first Apple device to incorporate an Intel LTE chipset was the iPhone 7 launched on 16 September 2016.149

(170) The LTE chipsets that Apple obtained from Intel in 2016 accounted for between [10- 20] and [20-30]% of Apple's total LTE chipset requirements150 and for less than [50- 60]% of its LTE chipset requirements for the iPhone 7.151

(171) Tables 3 and 4 show the LTE chipsets that Apple obtained from Qualcomm during the period 2011 to 2016 in terms of volume of units and value.

Table 3: LTE chipsets obtained by Apple from Qualcomm throughout the period 2011 to 2016 ('000 Units)

Chipset model | Standards supported152 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015153 | 2016 |

MDM9600/ MDM9610 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | [100- 200] | [10,000- 20,000] | [10-20] | [10-20] | - | - |

MDM9615 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | [50,000- 150,000] | [50,000- 150,000] | [2,500- 3,500] | [100-200] | [10-20] |

MDM9615 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | [50,000- 150,000] | [50,000- 150,000] | [30,000- 100,000] | [20,000- 100,000] |

MDM9625 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | - | [100,000- 200,000]154 | [100,000- 200,000] | [10,000- 20,000] |

MDM9635 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | - | - | [50,000- 150,000] | [50,000- 150,000] |

MDM9625 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | - | - | [20-30] | [20,000- 30,000] |

MDM9645 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | - | - | - | [50,000- 150,000] |

Total |

| [100- 200] | [50,000- 150,000] | [100,000- 200,000] | [200,000- 300,000] | [200,000- 300,000] | [100,000- 200,000] |

Source: Apple155

Table 4: LTE chipsets obtained by Apple from Qualcomm throughout the period 2011 to 2016 ('000 USD)

Chipset model | Standards supported156 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015157 | 2016 |

MDM9600/ MDM9610 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | [4,000- 5,000] | [300,000- 400,000] | [200-300] | [200-300] | - | - |

MDM9615 |

UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | [1,000,000 - 2,000,000] | [1,000,000 - 2,000,000] | [30,000- 40,000] | [2,000- 3,000] | [200-300] |

MDM9615 |

UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | [1,000,000 - 2,000,000] | [1,000,000- 2,000,000] | [500,000- 600,000] | [400,000- 500,000] |

MDM9625 |

UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | - | [1,000,000- 2,000,000] 158 | [2,000,000 - 3,000,000] | [300,000- 400,000] |

MDM9635 |

UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | - | - | [1,000,000 - 2,000,000] | [1,000,000 - 2,000,000] |

MDM9625 | UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | - | - | - | [200,000- 300,000] |

MDM9645 |

UMTS/CDMA/ LTE | - | - | - | - | - | [1,000,000 - 2,000,000] |

Total |

| [4,000- 5,000] | [2,000,000 - 3,000,000] | [3,000,000 - 4,000,000] | [3,000,000- 4,000,000] | [4,000,000 - 5,000,000] | [3,000,000 - 4,000,000] |

Source: Apple159

8.5. Qualcomm's payments to Apple pursuant to the Agreements

(172) Pursuant to the Agreements, Qualcomm paid Apple a total of USD [2-3] billion between 2011 and 2015.160

(173) The Agreements also provided that Qualcomm would make Additional Variable Incentive Fund payments by 15 November 2016 and Additional Marketing Fund payments by 15 February 2017. However, Qualcomm never made such payments because the Agreements terminated on 16 September 2016 pursuant to Clause 1.5A of the First Amendment to the Transition Agreement following Apple's launch of iPhone 7 devices incorporating Intel's LTE chipsets.161

9. MARKET DEFINITION

9.1.Principles

(174) The definition of the relevant market is carried out, in the context of the application of Article 102 of the Treaty and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement, in order to define the boundaries within which it must be assessed whether a given undertaking is able to behave to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors and its customers.162

(175) The concept of the relevant market implies that there can be effective competition between the products or services which form part of it and this presupposes that there is a sufficient degree of interchangeability between all the products or services forming part of the same market in so far as a specific use of such products or services is concerned.163

(176) An examination to that end cannot be limited solely to the objective characteristics of the relevant products and services, but the competitive conditions and the structure of supply and demand on the market must also be taken into consideration.164

(177) The definition of the relevant market does not require the Commission to follow a rigid hierarchy of different sources of information or types of evidence. Rather, the Commission must make an overall assessment and can take account of a range of tools for the purposes of that assessment.165

9.2.Relevant product market

9.2.1. Principles relating to product market definition

(178) The identification of the relevant product market by the Commission derives from the existence of competitive constraints. Undertakings are subject to three main sources of competitive constraints, namely demand-side substitution, supply-side substitution and potential competition. From an economic point of view, for the definition of the relevant market, demand-side substitution constitutes the most immediate and effective disciplinary force on the suppliers of a given product.166

(179) Supply-side substitution may also be taken into account when defining markets in those situations in which its effects are equivalent to those of demand-side substitution in terms of effectiveness and immediacy. There is supply-side substitution when suppliers are able to switch production to the relevant products and market them in the short term without incurring significant additional costs or risks in response to small and permanent changes in relative prices. When these conditions are met, the additional production that is put on the market will have a disciplinary effect on the competitive behaviour of the companies involved.167

(180) Supply-side substitution is, however, not taken into account for the definition of a relevant market each time it would entail the need to adjust significantly existing tangible and intangible assets, additional investments, strategic decisions or time delays.168

9.2.2. Application to this case

(181) The Commission concludes that the relevant product market for the purposes of this Decision (the “LTE chipset market”) covers slim and integrated LTE chipsets but not captive production of such chipsets.

(182) The Commission has reached this conclusion based on the following factors:

(a) GSM chipsets are not substitutable for LTE chipsets (Section 9.2.3.1);

(b) UMTS chipsets are not substitutable for LTE chipsets (Section 9.2.3.2);

(c) Single-mode LTE chipsets are not substitutable for LTE chipsets (Section 9.2.3.3);

(d) Baseband chipsets that comply with certain iterations of the LTE standard are substitutable for baseband chipsets compliant with other iterations of the LTE standard (Section 9.2.4);

(e) Non LTE-compliant baseband chipsets that comply with technologies other than LTE, such as CDMA, TD-SCDMA (UMTS-TDD), WiFi and WiMAX, are not substitutable for LTE chipsets (Sections 9.2.5, 9.2.6 and 9.2.7);

(f) Integrated baseband chipsets are substitutable for standalone baseband chipsets, also known as slim modems (Section 9.2.8); and

(g) Captive production of baseband chipsets does not exert a competitive constraint on merchant market sales of baseband chipsets (Section 9.2.9).

(183) Contrary to Qualcomm's arguments, the Commission could reach these conclusions without having to carry out a SSNIP169 test (Section 9.2.10).

9.2.3. The substitutability of LTE chipsets with GSM chipsets, UMTS chipsets, and single- mode LTE chipsets

(184) This section assesses whether LTE chipsets are substitutable with any of three other types of chipsets, namely:

(1) GSM chipsets (Section 9.2.3.1);

(2) UMTS chipsets (Section 9.2.3.2); and

(3) Single-mode LTE chipsets (Section 9.2.3.3).

9.2.3.1. The substitutability of GSM chipsets and LTE chipsets

(185) During the Period Concerned, GSM chipsets represented a relatively large proportion of worldwide sales of chipsets. For example, in 2014, GSM chipsets represented [30- 40]% of worldwide sales of all chipsets.170

(186) The Commission concludes that GSM chipsets are not substitutable for LTE chipsets. This is for the following reasons.

(187) First, data rates achieved by GSM chipsets are inadequate for data-transfer intensive applications like video streaming. For an operator or mobile OEM wishing to enable these services, GSM chipsets, with a data rate limit of approximately 100 kbps, are not a viable alternative. This is confirmed by several of the baseband chipset customers that responded to requests for information, for example:

(1) According to […]: "[i]n most markets with widespread 3G adoption (including the EEA), neither [mobile network operators, "MNOs"] nor end consumers would be likely to accept devices limited to GSM as alternatives to devices supporting more modern mobile standards. In addition, OEMs (including […]) tend to market the smallest number of devices possible which could serve the majority of the markets in which they are present. Since the majority of the markets are 3G/4G, […]UMTS chipsets are usually the bare minimum."171

(2) According to Apple, “it requires [baseband chipset] suppliers to support multi- mode functionality. (LTE, WCDMA, CDMA, and GSM). Apple would not use a chipset in any of its devices that supports anything less than GSM/UMTS/LTE."172

(188) Second, LTE chipsets are more efficient than GSM chipsets in the use of spectrum for data and voice.173

(189) Third, suppliers of GSM chipsets174 are unable to switch to the supply of LTE or even UMTS chipsets in a short timeframe and without incurring significant additional investments or risks. For example:

(1) According to […]: "GSM chipsets do not allow easy transition to UMTS. Indeed, a number of [baseband chipset] suppliers have attempted unsuccessfully to make this switch - for example, Texas Instruments[175], a [baseband chipset] supplier who has since exited the market, failed to make the switch from GSM to UMTS despite their strength in GSM chipsets".176

(2) According to […]: "In order to switch from supplying GSM chipsets to chipsets supporting GSM/UMTS, a supplier must undertake significant additionalinvestments, because little of the original GSM investment can be leveraged into UMTS development. As much as 80% of the GSM/UMTS chipset is specific to UMTS, including the physical layer of the chipset, as well as the access stratum, which is a functional layer responsible for transporting data over the wireless connection and managing radio resources. Further, the UMTS standard also requires the use of many additional components as compared to GSM hardware. Accordingly, […] estimates the total time needed for such a switch as approximately between three and five years."177

(190) While Qualcomm claims that GSM and LTE chipsets form part of the same market, which would also include chipsets supporting all other cellular and wireless communications standards,178 it has submitted no evidence to support this claim.

9.2.3.2. The substitutability of UMTS chipsets and LTE chipsets

(191) During the Period Concerned, UMTS chipsets represented a relatively large proportion of worldwide sales of chipsets. For example, in 2014, UMTS chipsets represented [30-40]% of worldwide sales of all chipsets.179

(192) The Commission concludes that UMTS chipsets are not substitutable for LTE chipsets. The Commission also concludes that, contrary to Qualcomm's claim, UMTS and LTE chipsets are not part of an overall market for baseband chipsets supporting each of the competing wireless communication standards.

(193) There are two main reasons why UMTS chipsets are not substitutable for LTE chipsets.

(194) First, a majority of those baseband chipset customers that responded to requests for information indicated that they would not find it commercially feasible to switch from LTE chipsets to UMTS chipsets.180 For example:

(1) According to Apple: "[…], consumers expect Apple’s devices to include the most recent technologies. For example, it would not be a commercially viable option for Apple to replace GSM/UMTS/LTE chipsets with chipsets that are only enabled with UMTS and earlier generation standards in its most recent devices. LTE is a requirement for most of the world’s largest carriers and consumers. There is no alternative standard to LTE for devices designed for sale in markets that demand LTE connectivity, which includes all European markets." 181

(2) According to […]: "In most markets that […] operates, the majority of MNOs support (and require) LTE access. Therefore, LTE has generally become a necessary configuration even for low-end smartphones. Thus, in general […] would prefer […]LTE chipsets over […]UMTS. Similarly the MNOs thatpurchase […] devices in the EEA and the United States already require, in many cases, that the […] devices support LTE." 182

(3) According to […]: "[…] customers require UMTS LTE (LTE is a higher speed and results in a better customer experience.)"183

(195) This conclusion is not affected by Qualcomm's claim regarding the alleged bias or lack of clarity of certain replies by baseband chipset customers to two questions in a request for information.184 This is because these questions were sent to sophisticated customers that could be expected to carefully read and interpret the questions put to them and not be misled.185

(196) Second, suppliers of UMTS chipsets are unable to switch to the supply of LTE chipsets in a short timeframe and without incurring significant additional investment or risk. This is because the addition of LTE functionalities to a UMTS chipset entails substantial costs and time. This is confirmed by all those baseband chipset producers that responded to requests for information.186 For example:

(1) According to […]: "There would be new complex software and algorithms, different protocol stack, radio frequencies and reference design. At chip level, switching to a different standard would be a ground-up new chip design to an entirely new block diagram; at least that was the case in the custom segment when we were […]. For those suppliers with the requisite 3G + 4G capability switching would in our view be possible but not in a short timeframe. In the […], embracing a new 3G standard was a new chip development and not possible without […] 3G designs and capabilities. […] would support […] on new standards based chips by adapting to […] requirement specification the MCU, DSP and memory integrated circuitry but […] would provide the 3G wireless capability in the form of logic gates and algorithms for on-chip integration and execution of […] proprietary software for […] RF and reference design validation." 187

(2) According to […]: "With the move to GSM/UMTS/LTE, the number of use cases that must be predicted and tested during the design process again increases exponentially. Therefore, just as the switch from GSM to GSM/UMTS requires significant time and investment as a result of increased complexity, so too does the switch to GSM/UMTS/LTE."188

(3) According to […]: "The development processes for LTE are completely distinct from GSM/UMTS and have to be started from scratch. LTE has entirely different protocols and specifications from those of UMTS and GSM […] b. New testing equipments for the LTE standard will be required. […] c. Thesemiconductor foundries will need to apply new fabrication technologies and processes […] d. Baseband certification/verification processes need to be conducted […]".189

(4) According to […], the cost of switching from UMTS to LTE chipsets amounts to: "At least a billion dollars or more, which includes R&D expenses from 2011-2014, acquisition of companies, investment in employees/engineers, etc".190

(197) Qualcomm claims191 that UMTS chipsets and LTE chipsets are part of the same market, which would also include chipsets supporting all other cellular and wireless communications standards,192 on the basis of the following five main reasons:

(1) LTE is simply an evolution of UMTS, in the same way as UMTS-HSDPA or UMTS-HSUPA, unlike LTE-A which represents the first "true" 4G technology;

(2) The maximum download and upload speeds of UMTS and LTE are similar and indicative of the existence of a chain of substitution between UMTS and LTE chipsets;193

(3) The average prices of UMTS and LTE chipsets are similar and indicative of the existence of a chain of substitution between those chipsets;

(4) LTE and UMTS chipsets were substitutable at least until 2013194 because LTE networks were rolled out slowly in the European Economic Area ("EEA"); and

(5) The Commission has in previous decisions defined a single relevant market for 3G technologies, which according to Qualcomm includes both UMTS and LTE chipsets, as opposed to a market for "true" 4G technologies, which according to Qualcomm includes LTE-A chipsets.

(198) However, none of the five reasons are convincing arguments that UMTS chipsets and LTE chipsets are part of the same market.

(199) First, LTE is not "simply an evolution" of UMTS.

(200) In the first place, UMTS and LTE are based on different technologies. While UMTS and its different iterations (such as HSDPA) are based on W-CDMA, LTE and its different iterations (such as LTE-A) are based on OFDMA.195

(201) In the second place, a majority of those baseband chipsets customers that responded to requests for information confirmed that they would not find it commercially feasible to switch from LTE chipsets to UMTS chipsets in their devices.196

(202) Moreover, while two customers, […]197 and […]198, stated that they would find it commercially feasible to switch from LTE chipsets to UMTS chipsets:

(1) […] based its statement on the alleged novelty of LTE technology, even if LTE had been already launched commercially since December 2009; and

(2) […] indicated that switching would only occur with the acceptance of carriers, which is unlikely given that carriers generally favour and require LTE support.199

(203) In the third place, suppliers of UMTS chipsets cannot switch to the supply of LTE chipsets in a short timeframe and without incurring significant additional investment or risk. This was confirmed by all those suppliers of baseband chipsets that responded to requests for information.200

(204) Second, contrary to Qualcomm's claim, the maximum download and upload speeds of UMTS chipsets and LTE chipsets are not similar and, in any event, do not indicate the existence of a chain of substitution between UMTS and LTE chipsets.

(205) In the first place, a higher maximum download speed is only one of the advantages of LTE. LTE is also a superior technology compared to UMTS in several other respects, including spectrum efficiency, latency and upload speed, as confirmed, for example, by the following companies that responded to requests for information:

(1) […]: "As compared with 3G, 4G/LTE has focused on improving mobile broadband performance (rather than improving voice communication) and is intended to deliver significant increases in mobile broadband data capacity and performance. 4G networks generally offer faster download/upload speeds, web browsing and reduced latency as compared with 3G networks".201

(2) […]: "Most carriers are migrating to LTE because, among other reasons, LTE offers higher capacity, higher data rates and many attractive features for carriers/operators, such as reduced network and equipment costs, and the ability to deploy heterogeneous networks (e.g., employing WiFi and LTE in the same network). This makes the requirement for GSM/UMTS/LTE mandatory on modern devices in order to be commercially viable."202

(206) Regarding the superiority of LTE over UMTS in terms of spectral efficiency, this is confirmed by the following:

(1) A guide written by cellular technology experts and submitted by Qualcomm, which states that: [Third party confidential information].203

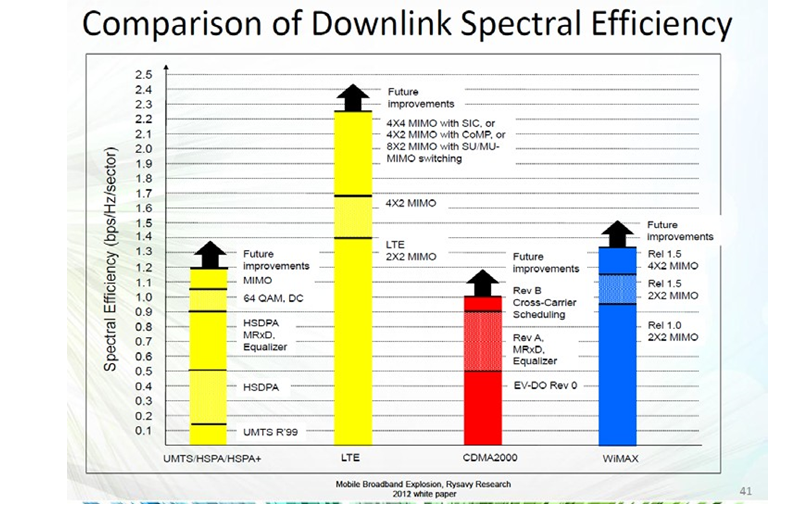

(2) The following extract from a presentation by Rysavy Research entitled "Comparison of Downlink Spectral Efficiency", which compares the spectral efficiency of (inter alia) UMTS and LTE204 and indicates that the downlink spectral efficiency of LTE is significantly superior to UMTS (more than 2.2 bps/Hz/sector compared to 1.2 bps/Hz/sector).

(3) The probative value of this extract is not called into question by Qualcomm's claim that other extracts and quotes in the same presentation205 indicate that the performance of LTE and UMTS is similar. Those extracts and quotes do not provide information about the performance gap between LTE chipsets on the one hand and GSM and UMTS chipsets on the other hand; rather, they simply refer to the fact that GSM and UMTS are expected to co-exist with LTE for a given time period.

(207) Regarding the superiority of LTE over UMTS in terms of latency, this is confirmed by the graph entitled "LTE latency in ms vs latencies experiences on otherconnection types (smaller is better)",206 which compares different cellular and wireless communications standards and indicates that the latency of LTE is approximately half that of UMTS: while the latency of UMTS (3G) and HSPA+ ranges between 172 and 212 ms, the latency of LTE is 98 ms.

(208) The probative value of this graph is not affected by Qualcomm's claim that a study by O'Reilly Media,207 a provider of technology-related training, indicates that the performance of LTE and UMTS networks is similar for the following reasons:208

(1) The substitutability of LTE and UMTS networks is irrelevant to the assessment of the substitutability of LTE and UMTS chipsets. This is because while different networks are needed to support UMTS and LTE technologies, LTE chipsets support both UMTS and LTE technologies;

(2) The study indicates the coexistence of different standards, which is irrelevant for the purposes of substitutability between UMTS and LTE chipsets. This is because, as pointed out in recital (55), LTE chipsets are compliant with both UMTS and LTE technology;

(3) The study makes a clear distinction between LTE (which it refers to as "3.9 G") and previous technologies;209

(4) The study confirms that UMTS and LTE are based on different technologies and architectures;210 and

(5) The study includes the following graph, which confirms the superior performance of LTE compared to HSDPA, at least in terms of upload and download speed.211[Third party confidential information]

(209) Regarding the superiority of LTE over UMTS in terms of upload speed, this is confirmed by the following:

(1) The theoretical maximum upload speed of LTE (up to 50 Mbps) is more than four times higher than that of UMTS (11.5 Mbps212);

(2) The theoretical maximum upload speed of LTE chipsets supplied by Qualcomm (up to 50 Mbps) is more than nine times higher than that of UMTS chipsets supplied by Qualcomm (5.76 Mbps).213