Commission, October 16, 2019, No 40608

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

Broadcom

COMMISSION DECISION of 16.10.2019

relating to a proceeding under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 54 of the EEA Agreement and Article 8 of Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty

Case AT.40608 – Broadcom

1. INTRODUCTION

(1) This Decision sets out the European Commission’s (the “Commission”) findings that the conduct of Broadcom Inc. is prima facie breaching Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) and Article 54 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (“EEA Agreement”) and that the likely damage resulting from such infringement is such as to give rise to a situation of urgency justifying the adoption of interim measures pursuant to Article 8 of Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty (“Regulation (EC) No 1/2003”). Broadcom Inc., together with its subsidiaries and, where relevant, its legal predecessor’s subsidiaries, are referred to in this Decision as “Broadcom”.

(2) This Decision is structured as follows:(a) In section 2, the Commission outlines the undertaking concerned by the Decision;(b) In section 3, the Commission describes the procedural steps it followed in these proceedings;(c) In section 4, the Commission describes the products concerned by the Decision, namely Systems-on-a-Chip (“SoCs”) for incorporation into set-top boxes (“STBs”) and/or residential gateways;(d) In section 5, the Commission describes the market dynamics, customers and applications at stake, and in particular the role of SoC suppliers, original equipment manufacturers (“OEMs”) and service providers;(e) In section 6, the Commission describes certain agreements entered into between Broadcom and six OEMs (the “Agreements”);(f) In section 7, the Commission outlines the conditions for adopting interim measures;(g) In section 8, the Commission concludes on the basis of its preliminary factual and legal analysis that Broadcom is prima facie infringing Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement.4 In particular, the Commission concludes that, prima facie, Broadcom is dominant in: (i) SoCs for STBs; (ii) SoCs for fibre residential gateways; and (iii) SoCs for xDSL5 residential gateways. It also concludes that the Agreements contain provisions which prima facie have the object or effect of forcing or inducing customers to obtain all or almost all of their requirements for SoCs for STBs and SoCs for cable, fibre and xDSL residential gateways from Broadcom, in particular by means of (quasi-) exclusivity arrangements or leveraging restrictions. These provisions will hereinafter be referred to as the “exclusivity-inducing provisions”(h) In section 9, the Commission concludes that if Broadcom’s ongoing conduct were allowed to continue, it would likely lead to serious and irreparable damage to competition in the markets for (i) SoCs for STBs; (ii) SoCs for cable residential gateways; (iii) SoCs for fibre residential gateways; and (iv) SoCs for xDSL residential gateways, notably in the form of the potential exit or marginalisation of Broadcom’s competitors from these markets;(i) In section 10, the Commission outlines the interim measures adopted by means of this Decision. In particular, the Commission requires Broadcom: (i) to unilaterally cease to apply with immediate effect the exclusivity-inducing provisions identified in sections 8.5.2.1.A and 8.5.2.1.B below contained in the Agreements concerning [OEM A]’s, [OEM B]’s, [OEM C]’s, [OEM D]’s, [OEM E]’s and [OEM F]’s purchases of SoCs for STBs and SoCs for cable, fibre or xDSL residential gateways (as appropriate) from Broadcom. Broadcom shall, without delay, (a) inform the contracting parties of the Agreements of such disapplication and (b) notify the Commission that it has put this measure into effect, such notification to be accompanied by supporting documentation; and(ii) to refrain from agreeing the same exclusivity-inducing provisions or provisions having an equivalent object or effect as those identified in sections8.5.2.1.A and 8.5.2.1.B below in any future contracts or agreements (written or otherwise) with [OEM A], [OEM B], [OEM C], [OEM D], [OEM E] and [OEM F], and refrain from implementing punishing or retaliatory practices having an equivalent object or effect;(j) In section 11, the Commission explains the reasons why the interim measures are proportionate and take into due account Broadcom’s legitimate interests;(k) In section 12, the Commission explains why it is necessary to foresee periodic penalty payments pursuant to Article 24(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 and Article 5 of Regulation (EC) No 2894/94 of 28 November 1994 concerning arrangements for implementing the Agreement on the European Economic Area (“Regulation (EC) No 2894/94”),6 if Broadcom were to fail to comply with the interim measures;(l) In section 13, the Commission sets out the grounds upon which it has jurisdiction to impose interim measures in this case;(m) In section 14, the Commission indicates the addressee of this Decision; and(n) In section 15, the Commission presents its conclusions.

2. THE UNDERTAKING CONCERNED BY THE DECISION

(3) Broadcom Inc. is the ultimate parent company of a group of companies active in the semiconductor and software solutions space, that is headquartered in San Jose, California, United States. Broadcom has design, product and software development engineering resources in the United States, Asia, Europe and Israel.7 In 2018, Broadcom’s turnover was USD 20.9 billion.8

(4) Broadcom has three main business divisions: semiconductor solutions, infrastructure software and IP licensing.9 Broadcom’s products are used in end products such as enterprise and data centre networking, home connectivity, STBs, broadband access devices (i.e. residential gateways), telecommunication equipment, smartphones and base stations, data centre servers and storage systems, factory automation, power generation and alternative energy systems, and electronic displays.10

(5) Broadcom is the world’s largest designer, developer and provider of integrated circuits for wired communication applications and the worldwide leader in SoC solutions for STBs for video delivery.11

(6) The substantial majority of Broadcom’s semiconductor sales is accounted for by sales to OEMs, or their contract manufacturers and distributors.12

3. PROCEDURE

(7) In the course of 2018, the Commission received market information that Broadcom may be imposing exclusivity or quasi-exclusivity restrictions on its customers for certain types of integrated circuits for incorporation into STBs and residential gateways, amongst others.

(8) Between 24 October 2018 and 27 August 2019, the Commission sent requests for information pursuant to Articles 18(2) and 18(3) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 to Broadcom, its direct and indirect customers and its competitors.

(9) On 21 March 2019 and on 25 June 2019, the Commission met with Broadcom representatives in the context of its preliminary investigation.

(10) On 26 June 2019, the Commission decided to initiate proceedings in the present case within the meaning of Article 2(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004.13 On the same day, the Commission adopted a Statement of Objections (“SO”) addressed to Broadcom outlining the Commission’s preliminary conclusions as regards imposing interim measures pursuant to Article 8 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 relating to specific aspects of Broadcom’s behaviour that was subject to the Commission’s investigation.

(11) On 23 July 2019, Broadcom submitted a response to the SO (“SO Response”), contesting the Commission’s preliminary findings on interim measures.14

(12) On 1 August 2019, the Commission sent Broadcom a letter (“Letter of Facts”) to inform it about evidence that the Comission considered may be relevant to corroborate and support the preliminary conclusions reached in the SO.15

(13) On 20 August 2019, an Oral Hearing took place upon Broadcom’s request (“Oral Hearing”).

(14) On 22 August 2019, Broadcom submitted its comments on the Letter of Facts (“Comments on the Letter of Facts”).16

(15) On 26 August 2019, Broadcom submitted a written response to two of the questions that the Commission had posed during the Oral Hearing.17

(16) On 7 October 2019, an Advisory Committee meeting took place.

(17) On 10 October 2019, the Commission met with Broadcom representatives in order to provide an advance notice as to the possible adoption of this Decision.

4. THE PRODUCTS CONCERNED BY THE DECISION

(18) This Decision concerns certain types of integrated circuits (“ICs”) incorporated into network access equipment that is installed at customer premises (so-called customer premises equipment, “CPE”), namely STBs and residential gateways.

(19) An STB is a hardware device that converts external source signals into video content on television. STBs are used to enable consumers to watch on television the video content transmitted via various technologies, such as cable, satellite and Internet Protocol Television (“IPTV”).

(20) A residential gateway is a hardware device that connects one or more electronic devices to a single Internet access point.18 Residential gateways do so by combining modem functionality (i.e., a component that converts analog signals from service providers into digital signals suitable for computers and vice versa19) with a wireless router (i.e., a centralised network device that allows, manages and secures Internet access for multiple wireless access points).20 Residential gateways allow access to the Internet by means of three main technologies: xDSL, cable and fibre.21

(21) More specifically, the products concerned by this Decision are SoCs, namely chipsets combining electronic circuits of various components in a single unit, which constitute the core IC of an STB or residential gateway.

(22) In STBs, SoCs function as the “brain” of the system. SoCs are the most important component of an STB and often an expensive one.22 SoCs can provide high video security and high privacy protection for STBs, features that are particularly important for OEMs supplying network service providers in EU/EEA and the United States.23

(23) In residential gateways, SoCs also represent the core component of the system, allowing the device to manage connectivity access for other devices.

5. MARKET DYNAMICS, CUSTOMERS AND APPLICATIONS

(24) The manufacturing of SoCs for STBs and residential gateways is concentrated in the hands of a limited number of large players, with other smaller producers accounting for a negligible portion of the supply of these components. The industry is highly cyclical24 and characterised by high barriers to entry and expansion – notably as a result of the substantial initial and ongoing R&D investment required to supply SoCs and the other factors described in section 8.4.4 below.

(25) Chipset suppliers sell their SoCs to OEMs, which assemble them together with other components to manufacture STBs and residential gateways. Many OEMs, such as [OEM A], [OEM D] and [OEM E], typically supply both STBs and residential gateways.

(26) OEMs sell STBs and residential gateways to so-called service providers, i.e. providers of broadcasting and Internet connectivity services such as telecoms operators and cable service providers. Procurement at the level of service providers typically takes place by means of tender processes, also referred to as selection processes.25 In the EEA, tenders typically cover a service provider’s demand for products in multiple EU Member States, or even in both EEA and non-EEA countries.26

(27) The usual length of a product cycle is long, with several years between the order and delivery of ICs. Competitive bid selection processes (“tenders”) are generally organised by service providers roughly every 1.5 to 2 years.27 The tender process itself is typically lengthy and, as a result, requires chipset suppliers to dedicate significant development expenditures and engineering resources to assist OEMs in the tender process in an attempt to have the OEM’s solution incorporating the chipset supplier’s products selected by service providers, thereby obtaining a so-called “design win”. The failure to win a particular tender not only excludes a chipset supplier and OEM from competing for that service provider’s demand until a subsequent tender takes place, but it will typically continue to affect those suppliers for several years after a new tender has been held as “operators may continue to use legacy products for several years”.28 Moreover, failure to win a particular tender may prevent chipset suppliers from winning tenders in subsequent generations of a particular product.29 This can result in lost revenue and can weaken a chipset supplier’s position in future competitive selection processes.30

6. BROADCOM’S AGREEMENTS

(28) This section briefly describes the six OEMs that entered into the Agreements with Broadcom and the scope of each Agreement.31

6.1.Introduction to Broadcom’s Agreements

(29) Broadcom admits to pursuing “a form of partial vertical integration by contract, using a closer, more integrated relationship with key OEMs.”32 Concretely, Broadcom explains, this involves the use of a variety of contractual mechanisms with OEMs falling under what Broadcom describes as its “Strategic Partnership Strategy”.33

(30) According to Broadcom, ”the concept [of the Strategic Partnership Agreements, “SPAs”] was to identify a small handful of strategic OEM partners in which Broadcom would concentrate its bid support efforts. […] Broadcom’s SPA partners would receive distinct, appreciably higher levels of bid support.”34

(31) More in detail, according to Broadcom, so-called “Strategic Partners” may be offered “price concessions, better supply chain lead time, a direct purchasing relationship (OEMs do not have to go through vendors) and other forms of support.”35 Hence, several of the Agreements feature inter alia one or more of the following: (i) “pricingadvantages”;36 (ii) the granting to the OEM of “[e]arly access to Broadcom technology to accelerate OEM development,”37 […]38 […]; and (iii) […]39 […]40 together with Broadcom.

(32) In its presentation of 21 March 2019 to the Commission,41 Broadcom only referred to the existence of three SPAs, which had been entered into with [OEM A], [OEM D] and [OEM E].

(33) In the course of its investigation, however, the Commission became aware of the existence of additional Agreements including exclusivity-inducing provisions.42 These include the Agreements with [OEM B],43 [OEM C]44 and [OEM F].45

(34) In its SO Response, Broadcom referred to these additional Agreements as “Broadcom’s TPA [i.e., Technology Partnership Agreement] partnerships and related agreements” (the “TPAs”).46 Broadcom describes these agreements as “smaller-scale bid support agreements […]. In each case, the OEM in question tends to focus on one or two specific end-product segments, and the OEM approached Broadcom looking for some form of additional bid support in that business.”47

(35) While the terminology presented by Broadcom is not always used consistently across the Agreements described in sections 6.2 to 6.7 below, the Commission considers that all the clauses identified in sections 8.5.2.1.A and 8.5.2.1.B below contain exclusivity- inducing provisions.48

(36) In addition, it should be noted already at this stage that while Broadcom considers the SPAs (and indeed all the Agreements) to be “short term arrangements with OEM“outs”“49 that “[…]”,50 the Commission disagrees with this interpretation. Rather, and for the reasons described in more detail in section 8.5 below, the Commission considers that the Agreements amount prima facie to an abuse of Broadcom’s dominant position.

6.2.[OEM A]

(37) [OEM A] is a […] group, […].51

(38) [OEM A] is an OEM which manufactures and supplies a broad range of CPE, including residential gateways and STBs.52 […].53

(39) In 2017, according to industry benchmarking company IHS Markit (“IHS”), [OEM A] represented [20-30]% of the value of sales of STBs at global level.54 With regard to residential gateways, according to IHS, [OEM A] represented [10-20]% of all global sales, with [40-50]% for cable and [5-10]% for xDSL.55 At present, [OEM A] […] fibre residential gateways.

(40) Broadcom and [OEM A] entered into an agreement in […] 2019 (the [OEM A]- Broadcom Corporate Supply Agreement Addendum Term Sheet, “[OEM A] CSA”)56 for a term of one year, which commenced with effect from […] 2019,57 and covering inter alia SoCs for STBs, SoCs for xDSL residential gateways, SoCs for fibre residential gateways, SoCs for cable residential gateways.58 The [OEM A] CSA is an addendum to an overarching agreement entered into in […] 2008, and replaced aprevious addendum of substantially the same scope, which was entered into in […]2016.59 The geographic scope of the [OEM A] CSA is worldwide.60

6.3.[OEM B]

(41) [OEM B] is a […] company and one […] STB and residential gateway OEMs.61 [OEM B] currently supplies all types of STBs, as well as cable residential gateways.62

(42) In 2017, according to IHS, [OEM B] represented [5-10]% of the value of sales of STBs63 and [0-5]% of the total value of sales of residential gateways at global level (but [0-5]% of sales of cable residential gateways, […]).64

(43) [OEM B] has a […] business relationship with Broadcom going back […].65 In […] 2017, Broadcom and [OEM B] concluded a “Technology Partnership Agreement” (“[OEM B] TPA”)66 for an initial three-year term, with the option of a renewal for a further two years,67 and covering a variety of Broadcom Products - notably SoCs for STBs, SoCs for cable residential gateways, and also additional products falling into the catch-all categorisation “Other Video Ecosystem (including without limitation, any product for which Broadcom has a solution).”68 The geographic scope of the [OEM B] TPA is worldwide.69

6.4. [OEM C]

(44) [OEM C] is a […] OEM that manufactures a variety of network equipment, which it distributes in approximately […] countries.70

(45) In 2017, according to IHS, [OEM C] represented [5-10]% of residential gateways at global level71 (but [10-20]% of fibre residential gateways, […]).72

(46) On […] 2017, Broadcom and [OEM C] concluded a Technology Partnership Agreement (“[OEM C] TPA”)73 for a term of two years, six months74 and covering SoCs for fibre residential gateways.75 The geographic scope of the [OEM C] TPA is worldwide except China.76

6.5.[OEM D]

(47) [OEM D] is a […] OEM that is active in more than […] countries. It is a […] manufacturer of communication terminals, including STBs and residential gateways.77

(48) In 2017, according to IHS, [OEM D] represented [5-10]% of sales of STBs78 and [5- 10]% of sales of residential gateways at global level ([5-10]% of cable, [10-20]% of xDSL and [0-5]% of fibre residential gateways).79

(49) On […] 2017, Broadcom and [OEM D] concluded a “Non-binding Memorandum of Understanding” (“[OEM D] MoU”) for an initial period of two years, tacitly renewable for further periods of one year,80 and covering inter alia SoCs for STBs and SoCs for cable residential gateways, xDSL residential gateways and fibre residential gateways.81 The [OEM D] MoU was amended on […] 2019 by means of an Amendment to Non-Binding Memorandum of Understanding (the “[OEM D] MoU Amendment”).82 The geographic scope of the [OEM D] MoU is worldwide.83

6.6. [OEM E]

(50) [OEM E] is a […] company active in […] countries worldwide. [OEM E] is an OEM which manufactures and supplies a complete portfolio of CPE, including residential gateways and STBs.84

(51) In 2017, according to IHS, [OEM E] represented [10-20]% sales of STBs85 and [5- 10]% sales of residential gateways at global level86 [20-30]% of cable residential gateways, [5-10]% of xDSL residential gateways and [0-5]% of fibre residential gateways).87

(52) On […] 2017, Broadcom and [OEM E] entered into an SPA (“[OEM E] SoC SPA”).88 It is supplementary to an overarching agreement concluded in December 2009.89 The [OEM E] SoC SPA was concluded for an initial three-year term, with an option to renew for a further two years, and covering SoCs for STBs as well as for xDSL and fibre (so-called “telco”) as well as cable residential gateways.90

(53) The geographic scope of the [OEM E] SoC SPA is worldwide.91

6.7.[OEM F]

(54) [OEM F] is a […] OEM that manufactures a variety of network equipment, which it distributes to over 150 markets worldwide.92

(55) In 2017, according to IHS, [OEM F] represented [0-5]% of the total value of sales of residential gateways93 at global level (but [5-10]% of the total value of sales of xDSL residential gateways, […]).94

(56) On […] 2018, Broadcom and [OEM F] concluded a Letter of Intent (the “[OEM F] LoI”)95 for an initial three-year term, renewable “as may be reasonably required”,96 and covering SoCs for xDSL and fibre residential gateways.97 The geographic scope of the [OEM F] LoI includes “[…] North America, Mexico, all the member countries of the European Union, Nordic Countries, Switzerland, Russia, Turkey, Japan, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, UAE, and Saudi Arabia […]”.98

7. CONDITIONS FOR ADOPTING INTERIM MEASURES

(57) It is essential that the Commission’s power to take decisions finding an infringement of Articles 101 or 102 TFEU and requiring that such infringement be brought to an end is exercised in the most effective manner best suited to the circumstances of each given situation.99

(58) Interim measures are conceived to prevent that the Commission’s exercise of the power to make decisions finding that there is an infringement of Articles 101 or 102 TFEU becomes ineffective because of the action of certain undertakings.100

(59) Pursuant to Article 8(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, there are two cumulative conditions to be met for adopting interim measures, namely:(a) the finding of a prima facie infringement of competition rules, and(b) the urgent need for interim measures due to the risk of serious and irreparable damage to competition.

(60) According to Article 8(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, a decision ordering interim measures shall apply for a specified period of time and may be renewed in so far as this is necessary and appropriate.

(61) Section 8 below sets out the Commission’s conclusions regarding the prima facie finding of an infringement of EU competition rules by Broadcom. Section 9 below sets out the Commission’s conclusions regarding the urgent need for interim measures due to the risk of serious and irreparable damage to competition.

8.PRIMA FACIE FINDING OF AN INFRINGEMENT OF ARTICLE 102 TFEU AND ARTICLE 54 OF THE EEA AGREEMENT

8.1. Principles

(62) By its very nature, the finding of a prima facie infringement is not based on a full and final appreciation of the facts and law in question,101 but rather on a factual and legal analysis indicating “at first sight” that the undertaking subject to the investigation exceeded the limits allowed to it by the applicable EU competition rules, thus giving rise to serious doubts as to the compatibility of its conduct with those provisions.102 Therefore, the requirement of a prima facie infringement cannot be placed on the same footing as the requirement of certainty that a final decision must satisfy.103 In this vein, the case-law has held that the finding of a prima facie infringement does not correspond to the finding of a “clear and flagrant infringement”,104 nor to the existence of a prima facie violation of the European Union competition rules “as a matter of probability”.105

8.2. Application to this case

(63) On the basis of the preliminary factual and legal analysis in sections 8.3 to 8.6 below, the Commission considers that in this case, prima facie, Broadcom is infringing Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement.

(64) During the Oral Hearing, Broadcom contested the legal test applied by the Commission for finding a prima facie infringement of Article 102 TFEU. In particular, Broadcom claims that there must not be a serious dispute regarding the correctness of the fundamental legal conclusion underpinning the contested decision, essentially meaning that if the subject matter of the interim measures is disputed, interim measures cannot be adopted.106 Broadcom also alleges that the Commission’s reference to an assessment “at first sight” would imply a lowering of the standard for the substantive legal and factual assessment in interim measures cases to whatever is apparent or conceivable “at first sight”.107

(65) Broadcom’s claims are flawed and need to be rejected.

(66) First, Broadcom’s claim that there must not be a serious dispute regarding the correctness of the fundamental legal conclusion underpinning the contested decision cannot be accepted. The Commission is required to establish the existence of a prima facie infringement as described in recital (62) above. It cannot be considered that if the dominant company disputes the existence of an infringement, the Commission is unable to impose interim measures. This interpretation would unduly limit the Commission’s power and result in any dominant company being able to prevent the imposition of interim measures by simply disputing the legal conclusion of the Commission.

(67) Second, the use of the phrase “at first sight” by the Commission does not refer to a standard different from a prima facie assessment nor is it intended to establish such; simply, the phrase “at first sight” is a literal translation of the Latin term “prima facie”, as it is evident from the quoted judgment in case T-23/90 Peugeot v Commission,108 where these two phrases appear to be used interchangeably.

8.3. Market Definition

8.3.1.Principles

(68) The definition of the relevant markets derives from an identification of the relevant competitive constraints in terms of demand-side and supply-side substitutability.

(69) From an economic point of view, for the definition of the relevant market, demand- side substitution constitutes the most immediate and effective disciplinary force on the suppliers of a given product.109 From a demand-side perspective, a relevant product market comprises all those products and/or services which are regarded as interchangeable or substitutable by the consumer, by reason of the products’ characteristics, their prices and their intended use.

(70) However, supply-side substitutability may also be taken into account when defining markets in those situations in which its effects are equivalent to those of demand-side substitution in terms of effectiveness and immediacy. There is supply-side substitution when suppliers are able to switch production to the relevant products and market them in the short term without incurring significant additional costs or risks in response to small and permanent changes in relative prices. When these conditions are met, the additional production that is put on the market will have a disciplinary effect on the competitive behaviour of the companies involved.110

(71) The relevant geographic market comprises an area in which the undertakings concerned are involved in the supply and demand of the relevant products or services, in which area the conditions of competition are similar or sufficiently homogeneous and which can be distinguished from neighbouring areas in which the prevailing conditions of competition are appreciably different.111

(72) The definition of the geographic market does not require the conditions of competition between traders or providers of services to be perfectly homogeneous. It is sufficient that they are similar or sufficiently homogeneous, and accordingly, only those areas in which the conditions of competition are ‘heterogeneous’ may not be considered to constitute a uniform market.112

8.3.2. Relevant Product Market

(73) The Commission’s preliminary factual and legal analysis in this section indicates that there are separate markets for:(a) STB SoCs;(b) SoCs for cable residential gateways;(c) SoCs for fibre residential gateways; and(d) SoCs for xDSL residential gateways.

8.3.2.1Distinction between SoCs, FE chips and WiFi chipsets

(74) The preliminary factual and legal analysis set out in this section indicates that SoCs do not belong to the same product market as other STB and residential gateways components, notably FE chips and WiFi chipsets.113

(75) From a demand-side perspective, the responses to the Commission’s requests for information indicate that there are separate markets for SoCs, FE chips and WiFi chipsets. Respondents, both chip suppliers and customers, have confirmed that these chips have different functions and are not substitutable.114 For example, Intel describes these different categories of chips as “distinct from one another [and that they] do not share a common technological base”115 and MediaTek indicates that “they have different functionalities, which are not interchangeable”.116 While some respondents noted that FE chips or WiFi chipsets may be incorporated into a SoC, they also confirm that these components are complements rather than substitutes.117

(76) From the supply-side, the Commission tested whether SoCs suppliers could switch to FE chips or WiFi chipsets and vice-versa without incurring significant additional investments or risks.

(77) Among chip suppliers, only Broadcom considers that such switching is conceivable. Nonetheless, even Broadcom acknowledges that, for suppliers to switch production, would involve (i) investing “meaningful resources” into chip design R&D; (ii) costs associated with ensuring that the integrated circuit interacts appropriately with other components in the system design; (iii) costs associated with securing services of a third-party foundry; (iv) incremental marketing and selling expenses; and (v) costs associated with securing intellectual property rights for its designs.118

(78) Other chip suppliers unanimously stated that developing SoCs, FE chips and WiFi chipsets requires significantly different expertise, techniques and assets.119 Respondents indicate that several factors would impede supply-side substitution, including (i) investment in engineering design resources; (ii) the acquisition and development of relevant integrated circuit designs; (iii) IP licensing costs and (iv) costs and time associated with certification and validation processes. Chip suppliers indicate that the necessary investments would be “very heavy”120 and that the requirements for switching production would be “virtually identical from a technology development standpoint as those for de novo entry”.121

8.3.2.2. Distinction between STB SoCs and residential gateway SoCs

(79) The preliminary factual and legal analysis set out in this section indicates that STB SoCs and residential gateway SoCs do not belong to the same product market.

(80) The results of the Commission’s investigation indicate that demand-side considerations justify segmenting the relevant market according to SoCs’ end- applications, namely SoCs for STBs and SoCs for residential gateways. In response to the Commission’s requests for information, OEM customers consistently explained that because STBs and residential gateways have different functionalities and the SoC is the main chip determining that functionality, they are not substitutable. As […] explains, “SoCs for residential gateways and SoCs for STBs are different components that enable different functions and features. They are not compatible, either in terms of hardware or software, and cannot be substituted”.122 Examples of differences include the presence of a video and graphics processor123 and HDMI interface124 in SoCs for STBs, neither of which are incorporated into SoC for residential gateways.125

(81) From the supply-side, the vast majority of chipset suppliers also stated that significant additional investments or risks would be required to switch production in a short time frame between SoCs for STBs and for residential gateways. Barriers identified include R&D efforts for technologies not common to both products, different testing environments and the possible need to contract a new foundry.126

8.3.2.3. Distinction between STB SoCs according to technology

(82) The preliminary factual and legal analysis set out in this section indicates that SoCs for STBs of different technologies belong to the same product market, with the exception of SoCs for retail over-the-top STBs (“retail OTT STBs”).

(83) STBs enable consumers to watch on television the video content transmitted by service providers via various technologies, namely cable, satellite, Internet Protocol Television (“IPTV”) and digital terrestrial television (“DTT”). Retail OTT STBs, on the other hand, are dongles or other pieces of hardware that are available for purchase through retail channels and that allow consumers to watch TV content over the Internet without a service provider delivering such content (e.g. Amazon Fire TV or Apple TV STBs).

(84) From the demand-side, in response to the Commission’s requests for information, the majority of OEMs indicated that the same type of SoC can be incorporated into STBs regardless of the underlying technology (cable, IPTV, satellite and DTT) since only the FE chip component would differ.127 This is because the type of technology an SoC is used for is determined by the FE chip incorporated. In theory the same generic SoC chip could be used and the FE chip changed according to the technology. Others also suggest that there are SoCs that include the interface for more than one type of technology. As […] explains, “the same type of SoC can be used for all types of STB platform/technology, as the SoC performs the same base functions in all cases. It is the addition of the FE to the SoC that allows the STB to tune and decode a cable, satellite or DTT signal for video output to a television. The same SoC can also output IP video (IPTV) to a television without the need for a separate FE”.128

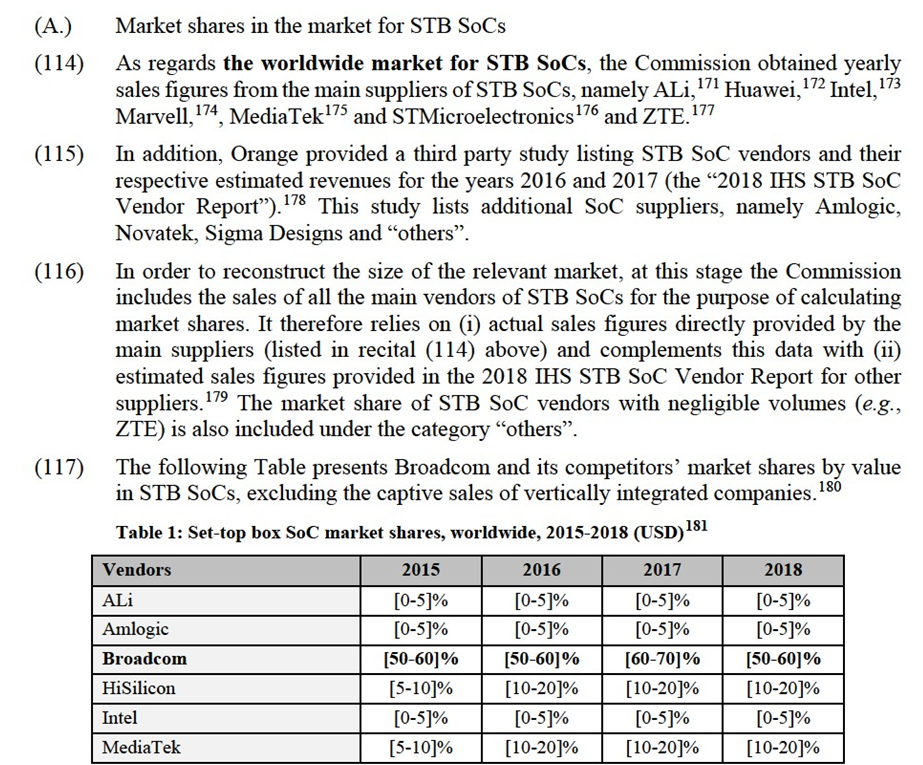

(85) Although these considerations apply to cable, IPTV, satellite and DTT STBs, the results of the Commission’s investigation indicates that the same is not true for SoCs for retail OTT STBs. The majority of OEMs consider that SoCs for retail OTT STBs cannot be used for other STBs.129 […] thus explains that “it can be said (…) that SoCs for STBs can work for OTT whereas the contrary is not true” because retail OTT STB SoCs do not meet the content security and conditional access specifications required of most other types of STBs.130 This view has been confirmed by other OEMs.131

(86) From the supply-side, most STB SoC suppliers consider that they are unable to switch from one technology (cable, IPTV, satellite, DTT) to another without incurring significant investment and risks.132 However, in its submission, STMicroelectronics distinguishes between SoCs that integrate an FE chip and those that do not: “in case the front-end demodulator is integrated inside the SoC, a full development is required(…). In case the FE chips is outside the SoC, no switch will be required (…)”.133 This is consistent with explanations provided by OEMs. Consequently, as indicated in recital (84) above, the key differentiating factor lies in the FE chip component and not in the SoC itself. Accordingly, the results of the Commission’s investigation in relation to STB SoC suppliers also supports the conclusion that STB SoCs, with the exception of retail OTT STB SoCs, belong to the same product market.

(87) As concerns the distinction between SoCs for retail OTT STBs and other types of STBs, suppliers like MaxLinear, STMicroelectronics and MediaTek highlighted significant differences between retail OTT and other STB SoCs.134 MediaTek explained that “[f]rom a product development perspective, they involve different technologies, different optimization, and different cost/performance considerations” and described retail OTT STB SoCs as “typically lack[ing] conditional access security” common to other STB SoCs.135 These views are confirmed by MaxLinear136 and STMicroelectronics, which emphasize the “massive investment” required from a retail OTT SoC supplier to develop STB SoCs.137

8.3.2.4. Distinction between residential gateway SoCs according to technology

(88) The preliminary factual and legal analysis set out in this section indicates that SoCs for residential gateways of different technologies belong to different product markets.

(89) From the demand-side, in response to the Commission’s requests for information, the vast majority of OEMs indicated that different residential gateway SoCs are required depending on the underlying technology of the modem (xDSL, cable, fibre). In particular, OEMs explain that residential gateway SoCs embed features and functionalities (interface, circuitery, safety qualifications, etc.) that are dependent on the different underlying technologies.138 As […] explains, “in practice, SoCs are normally dedicated to their own specific platforms/technologies as the xDSL/DOCSIS/Fibre FE is embedded in the SoC. As a result, it is not possible to use the same SoC for different underlying platforms or technologies”.139 Differences between residential gateway SoCs according to different underlying technologies are not limited to the FE chip. Arcadyan thus indicates that “[t]he front end hardware interface of xDSL/Fiber/Cable is different. The MAC (media access control address) of xDSL/Fiber/Cable is different. As we know, there is no SoC to support xDSL/cable/fiber all-in-one technology in the market”.140

(90) In response to the Commission’s requests for information, chip suppliers unanimously indicated the lack of supply-side substitutability between SoCs for different residential gateway technologies.141

8.3.2.5. Possible further segmentation within STB and residential gateway SoCs

(91) SoCs for STBs and residential gateways are highly differentiated products based on the supplier, device and customers.142 Broadcom thus distinguishes low- from high- end SoCs.

(92) In particular, in relation to STB SoCs, Broadcom indicated that it “focuses on high- end SoCs which provide high video security and high privacy protection for STBs. These security features are particularly important for Original Equipment Manufacturers (“OEMs”) supplying service providers in Europe and the US, […]. The main differences between high-end and low-end chipsets come from quality, features, technical support provided, software, privacy and content security.”143

(93) Other suppliers have confirmed that SoCs, including STB and residential gateway SoCs, are differentitated in performance, features and price.144 The existence of such differences is supported, for example, by the following statements and data submitted in response to the Commission’s requests for information:(a) Broadcom’s statement that: “[…] prices for ICs, and SoCs/FEs for STB in particular, are highly differentiated based on the supplier, device, the IC technology, the customer […]”;145(b) MediaTek’s statement that: “more developed regions (e.g. Western Europe andN. America) generally use higher priced, higher performance SoCs, FE chips, and WiFi modules/chips, whereas less developed regions (e.g. Eastern Europe, Latin America, China) generally use lower priced, lower performance SoCs, FE chips, and WiFi modules/chips. Thus, prices differ because specifications of the end-products are different. For example, as regards STBs, the price between an SoC for a low-end device could be half of the price of an SoC for a high-end device, although it is difficult to generalize across different products and regions”;146(c) Intel’s statement that: “In some regions of the world, particularly South America, China, and Southeast Asia, products147 may be sold for a lower price than in Europe or North America because there is less demand for certain high performing features. The lower-priced products sold in those regions usually have the same die as the higher-priced products sold in other regions but have some higher-end features fused off. The lower-priced products are therefore functionally different from their higher end counterparts”;148 and(d) Data obtained from the main SoC suppliers showing that Broadcom’s and its competitors’ average price per unit differs greatly. For example, […].149

(94) At this stage of the investigation, the Commission does not conclude that high and low-end SoCs form distinct product markets within STB SoCs or within the markets for cable, xDSL or fibre residential gateway SoCs. However, the Commission cannot exclude the possibility that the markets concerned would need to be segmented further so as to take account of the different competitive dynamics within each relevant market. Accordingly, for the purposes of this Decision, the Commission conducts its substantive assessment with respect to Broadcom’s market position and its conduct at the overall market level for SoCs for STBs and SoCs for xDSL, fibre residential gateways while still taking into accont the fact that the high-end part of the market constitutes the principal focus of Broadcom’s activities in each of these markets.

8.3.3. Relevant Geographic Market

(95) The factual and legal analysis set out in this section indicates that each of the markets for (i) STB SoCs; (ii) cable residential gateway SoCs; (iii) fibre residential gateway SoCs; and (iv) xDSL residential gateway SoCs identified in section 8.3.2 above are worldwide. In particular, there are no differences between these products that would result in a narrower market definition for any of the corresponding product markets.

(96) First, in response to the Commission’s requests for information, OEMs and chip suppliers indicated that there are no barriers to trade and more specifically to importing products into the EEA.150

(97) Second, the vast majority of customers indicate that, despite the existence of some specific difference in standards applicable in certain countries / geographic regions, such geography-specific specifications do not result in appreciable differences in the technical specifications of STB and residential gateway SoCs. As stated for example by Hitron, “There are differences on fre[que]ncy steps and output power level...etc and some further configu[r]ation or [software] customiz[a]tion, but [hardware] wise, in general, the technical specification are very similar”.151

(98) Third, while chip suppliers indicate that there are differences in prices depending on the geographic areas where the end-devices using particular SoCs are sold, these differences are driven by higher specifications or performance required in certain regions, with more expensive high-end SoCs being integrated in end-devices destined for sale in the US and Europe and less expensive low-end SoCs integrated in end- devices destined for sale in South America, China and South East Asia.152 As such, they appear to be the result of differentiated product markets (see recital (93) above) rather than a geographic market narrower than worldwide.

8.4. Dominance

8.4.1.Principles

(99) According to settled case law, dominance is “a position of economic strength enjoyed by an undertaking, which enables it to prevent effective competition being maintained on the relevant market by affording it the power to behave to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, its customers and ultimately of consumers.”153

(100) The existence of a dominant position derives in general from a combination of several factors which, taken separately, are not necessarily determinative.154 One important factor is the existence of very large market shares, which are in themselves, save in exceptional circumstances, evidence of the existence of a dominant position.155 That is the case where an undertaking has a market share of 50% or above.156

(101) Market shares may be calculated both in terms of the volume and value of sales. However, in cases of differentiated products, sales in value and their associated market share will usually be considered to better reflect the relative position and strength of each supplier.157

(102) A decline in market shares which are still very large cannot in itself constitute proof of the absence of a dominant position, particularly when the market shares are still in fact very high at the end of the infringement period.158 In the same vein, whilst the retention of market share may show the existence of a dominant position, a decline in market shares that are still very large cannot in itself constitute proof of the absence of a dominant position.159

(103) Other important factors when assessing dominance are the existence of countervailing buyer power and barriers to entry or expansion, preventing either potential competitors from having access to the market or actual ones from expanding their activities on the market.160 Such barriers may result from a number of factors, including exceptionally large capital investments that competitors would have to match, network externalitiesthat would entail additional cost for attracting new customers, economies of scale from which newcomers to the market cannot derive any immediate benefit and the actual costs of entry incurred in penetrating the market.161

(104) The ability to act independently of competitors, which is a special feature of dominance,162 is related to the level of competitive constraints facing the undertaking in question. It is not required for a finding of dominance that the undertaking in question has eliminated all opportunity for competition on the market.163 However, for dominance to exist, the undertaking concerned must have substantial market power so as to have an appreciable influence on the conditions under which competition will develop.164

8.4.2. Application to this case

(105) The preliminary factual and legal analysis set out in sections 8.4.3 to 8.4.5 below indicates that Broadcom holds a dominant position in the markets for STB SoCs, xDSL residential gateway SoCs and fibre residential gateway SoCs.

8.4.3. Market structure and market shares

8.4.3.1. Introduction

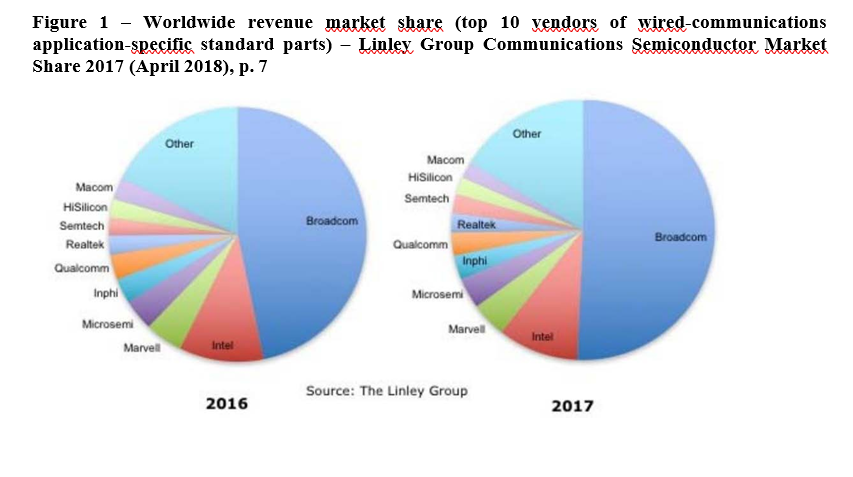

(106) Broadcom is the world’s largest designer, developer and provider of integrated circuits for wired communication applications,165 including SoCs for STBs and residential gateways. As indicated in the graph below, it accounts for roughly half of the whole industry’s global sales.

(107) Broadcom observes that in recent years a large number of chipset suppliers have exited the relevant markets at stake, noting that “[o]ver 35 SoC suppliers have exited the STB or Gateway market over last 20 years due to low [return on investment]”.166 In STB SoCs, Broadcom describes itself as “the only high-end STB SoC supplier left” on the market.167 In respect of residential gateway SoCs, Broadcom states that it faces only one competitor in cable (Intel); for xDSL and fibre, Broadcom states that its main competitors other than Intel are Chinese suppliers (Huawei/HiSilicon and ZTE), who focus on sales in China.168

8.4.3.2. Market shares

(108) Broadcom’s market shares in the markets for STB SoCs, xDSL residential gateway SoCs and fibre residential gateway SoCs are indicative of dominance in these markets.

(109) As part of its market investigation, the Commission asked Broadcom to provide its estimates on market shares for the products concerned. Broadcom only provided market shares based on volume and stated that it was unable to provide market share figures based on value.

(110) In respect of STBs, Broadcom noted that the estimated volumes of global STB shipments significantly differ across third party reports. However, Broadcom considers that one report, the IHS Markit Report (the “IHS Report”“),169 is consistent with its own “impression” of total STB shipments. Consequently, on the basis of the IHS Report, Broadcom estimates its 2018 market share by volume for global STB SoCs to amount to [20-30]%.

(111) In respect of residential gateways, Broadcom also considers that the IHS data is comparatively more reliable than other sources.170 As such, on the basis of the IHS Report, Broadcom estimates its 2018 market share by volume to amount to [40-50]% in fibre gateways and [50-60]% in xDSL gateways.

(112) However, in light of the Commission’s findings in recitals (93) to (94) above, and in particular the elements set out at recital (93), concerning the price differences applicable to SoCs for STBs and residential gateways, and Broadcom’s focus on the high-end (i.e. more expensive) SoCs, the Commission considers that market shares by value provide a better indication of competitive constraints and Broadcom’s market power than market shares by volume.

(113) In light of these considerations, the Commission requested that the main players active in the markets for STB and residential gateway SoCs provide the Commission with their sales data, so as to enable the Commission to calculate the market shares for Broadcom and its competitors by value. The assessment below is based on the information supplied by these players.

and service providers”.188 Broadcom stated that it does not even monitor the behaviour of these players in the market.189 These suppliers only exercise a limited degree of competitive pressure on Broadcom’s dominance, in particular as regards sales of SoCs for incorporation in products sold in the EEA.190

(123) Finally, the fact that Broadcom’s market share appears to have dropped between the years 2017 and 2018 does not alter the Commission’s finding. Third party reports show a decrease in US STB shipments in 2018, a slowing down of the rate of growth of STB sales in Europe and significantly higher growth rates in China and Southeast Asia.191 These market trends contribute to explaining the relative evolution of Broadcom’s sales at global level as it focuses on sales of SoCs to be incorporated in end-products sold in the US and EEA.192

(124) In its SO Response and its Comments on the Letter of Facts, Broadcom claims to be the only company capable of supplying high-end STB SoCs193 and not to be an unavoidable trading partner for the share of demand that other suppliers compete for,i.e. the lower end of the market.194 Moreover, Broadcom maintains that the exit of certain players from the industry occurred before it concluded the targeted SPAs and TPAs.195 Finally, Broadcom submits that there is no basis for disregarding HiSilicon and ZTE only because they focus on China. Broadcom maintains that, if the relevant geographic market is worldwide, China should not be disregarded.196

(125) These claims should be rejected for the following reasons.

(126) First, the Commission notes that Broadcom’s argument that no other player is capable of supplying high-end STB SoCs appears to be based on an exaggerated and distorted representation of market conditions. This Decision considers an overall STB SoC market for the purposes of the market definition, as shown in Table 1 above. At this level, a number of competitors are active. While the Commission does not dispute that these players currently only exercise a limited constraint on Broadcom’s position, this is not the same as arguing that Broadcom is not facing any competition whatsoever. This is demonstrated by evidence in the file which shows that service providers in the EU have in certain instances considered switching part of their requirements to alternative suppliers (see footnote 190).

(127) In this regard, MediaTek showed that its STB SoCs have been seriously considered or used by service providers active in the EU and the US.197 MediaTek’s capability to satisfy at the very least in certain circumstances EU services providers needs is confirmed by the fact that Sky, […], considers that MediaTek is a “top supplier” together with Broadcom (and HiSilicon).198 Moreover, the SO Response also shows that the boundaries between the high and the low end of the market may not be as defined as submitted by Broadcom, as Broadcom itself defines MediaTek, AMLogic and HiSilicon, and others listed in recital 111 of the SO, as “highly capable low-end” chip suppliers.199

(128) Second, the reasons why certain players might have exited the market recently do not affect the consideration of Broadcom as dominant. The Commission does not allege that market exit was due to Broadcom’s dominance.

(129) Third, Broadcom’s allegations regarding HiSilicon and ZTE are without merit, given that both HiSilicon’s and ZTE’s sales are included in Table 1 at recital (117) above with the market share calculation. Moreover, as explained in footnote 170 to the SO, which is included also in footnote 180 above, it is justified to exclude captive sales of vertically integrated suppliers, namely Huawei and ZTE, given that those sales do not pose a direct competitive constraint on STB SoC suppliers active in the merchant market. Broadcom does not contest that captive sales should be excluded from the market.

(B.) Market shares in the markets for xDSL and fibre residential gateways SoCs

(130) As regards xDSL and fibre residential gateway SoCs, the Commission obtained yearly sales figures from the main suppliers of residential gateway SoCs, namely Huawei,200 Intel,201 MediaTek202 Qualcomm203 and ZTE.204

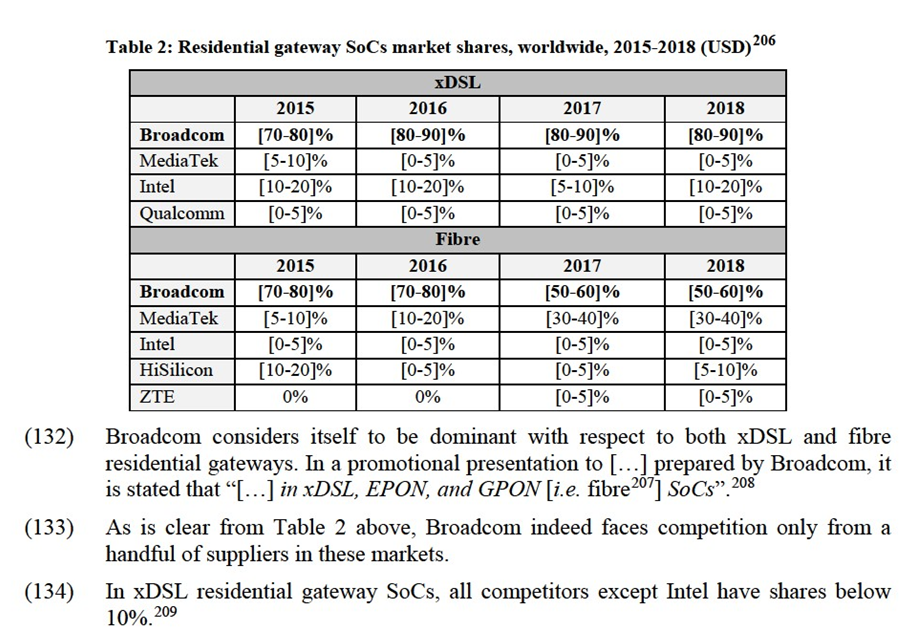

(131) The following Table presents Broadcom’s and its competitors’ market shares in terms of value for these residential gateway SoCs (excluding captive sales).205

SoCs into the EEA in the past 5 years.211 Competition from these players is at best localised and focused on specific areas. In addition, both companies estimate that in 2017 and 2018 none, or only a very limited part of their total production was incorporated in residential gateways sold in the EEA.212

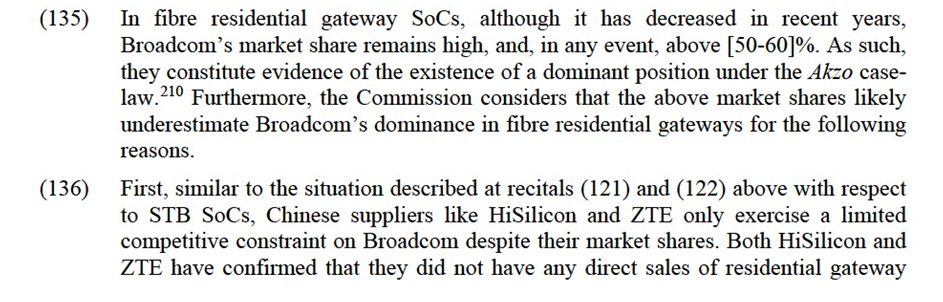

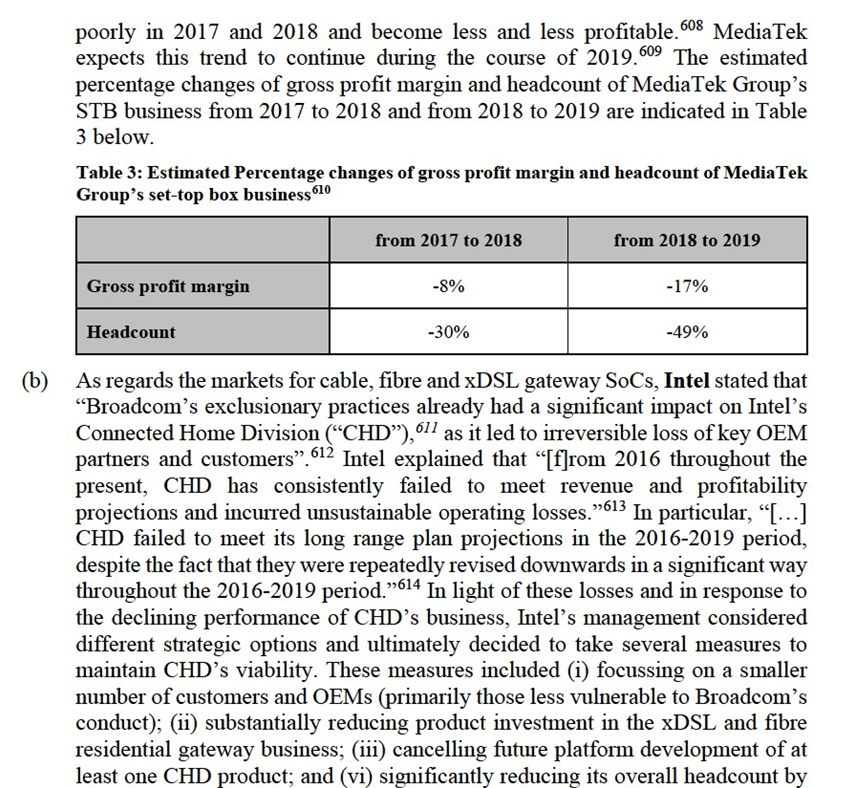

(137) Second, as regards MediaTek, its increase in global sales in recent years is also mostly due to increased sales in China rather than in the EEA. MediaTek’s shipments and sales of fibre residential gateway SoCs have thus continuously increased throughout the 2013-2018 period as demand for fibre residential gateway SoCs grew in China and Asia.213

(138) Furthermore, Intel, which, like Broadcom, focusses its activities on the supply of high- end SoCs, has only a very low market share that has been static in the preceding four years with respect to fibre residential gateway SoCs. This indicates, prima facie, that any loss to Broadcom’s market share in respect of fibre residential gateway SoCs has not been due to an increase in competition with respect to high-end SoCs. Rather, and consistent with this conclusion, the evidence that the Commission has collected at this stage of its investigation indicates that competitors’ market share growth is due to increased sales of low-end SoCs destined for the Chinese market, and, as such, is unlikely to constrain Broadcom’s conduct in respect of high-end SoCs required by European (and US) based OEMs and service providers.

(139) Broadcom disputes the Commission’s findings concerning the market for fibre residential gateway SoCs.

(140) First, Broadcom argues that its market share has been declining over the last years. In this regard, it maintains that the loss of market share is more pronounced than in the British Airways case and that, therefore, it cannot be considered dominant. It also submits a table with market shares calculated by volume to claim that it is not dominant.214

(141) Second, Broadcom submits that its average selling price has […]over the period of infringement. To support this statement, it provides a table comparing the value-based shares against the volume-based shares. Broadcom maintains that its fibre gateway SoCs have […] compared to those of its competitors. 215

(142) Third, Broadcom maintains that the Commission wrongly concluded in the SO that the market shares relied on likely underestimate its dominance in fibre gateways. It also submits that if Chinese suppliers indeed do not compete meaningfully with Broadcom, they are at no risk of being foreclosed. Besides, Broadcom argues that it only faces competition from Intel at the high-end of the market. Broadcom further claims that, bydefining the market so broadly, i.e. including also Asian suppliers, the Commission understated Intel’s market share.216

(143) Fourth, Broadcom dismisses its own power point presentation in which it presents itself as […] and maintains that it does not provide a reliable basis for […].217

(144) Fifth, Broadcom claims that, even if it were to be found dominant in fibre gateway SoCs, there is no infringement because the agreements targeted by the Commission do not target a significant share of demand.218

(145) Broadcom’s allegations are unfounded.

(146) First, as regards the drop in Broadcom’s market share in recent years, according to established case-law, a decline in market shares which are still very large cannot in itself constitute proof of the absence of a dominant position.219 Broadcom’s market shares have been up to [70-80]% and, in any event, consistently above 50% during the entire infringement period. Additionally, it is worth noting that the finding of dominance in British Airways was always based on market shares below 50%, that is of 40% or even less, i.e. a much lower market share than in the present case.220 In any event, as stated in recitals (135) to (138) above, in themselves, the market shares presented in table 2 (recital (131)) likely underestimate Broadcom’s dominance in fibre residential gateways.

(147) With regard to the tables with market shares submitted by Broadcom, given that market shares by value provide a better indication of competitive constraints and Broadcom’s market power than market shares by volume,221 which Broadcom has not sought directly to contest, it is unclear why in this case market shares by volume should be considered as providing a more meaningful indication of Broadcom’s market power than market shares calculated by value.

(148) Second, as regards Broadcom’s claim that its average selling price has […], even on the basis of Broadcom’s own data222, such […] appears to take place mostly between […] and not between 2015 and 2018 (i.e. the time period taken into account by the Commission), when prices […]. In addition, Broadcom provides no evidence showing that it has “[…] compared to its competitors”.

(149) Third, Broadcom’s claims in paragraphs 109 and 110 of the SO Response about the competitive constraint posed by Chinese suppliers and the inclusion of certain players in the market are also unsubstantiated. Contrary to Broadcom’s interpretation, the Commission does not state that Chinese companies do not compete with Broadcom, but rather that they do not exercise on it a strong degree of competitive pressure.

(150) Moreover, as regards the claims submitted by Broadcom concerning Intel and its presence in the high-end, it must be noted that Intel’s market share in fibre gateway SoCs is below 5%, while Broadcom’s is at least [50-60]% or above. If, as submittedby Broadcom, it were to be considered that the only players in the market are Broadcom and Intel, Broadcom would hold a [90-100]% market share, while Intel’s market share would be around [0-10]%.

(151) Fourth, concerning Broadcom’s presentation cited at recital (132) above, contrary to Broadcom’s arguments (see recital (143)), the fact that a company regards itself as holding the #1 market share and being “dominant” is a factor that the Commission may legitimately take into account when assessing that company’s market power.223

(152) Fifth, Broadcom’s arguments in paragraphs 112 and 113 of the SO Response on the lack of infringement in case it were to be found dominant, will be addressed in the abuse section of this Decision.

8.4.4. Barriers to entry

(153) The preliminary factual and legal analysis set out in this section indicates that there are high barriers to entry in the markets for STB SoCs, xDSL gateway SoCs and fibre gateway SoCs.224

(154) First, significant R&D expenditure is necessary to develop a meaningful presence in the industry. For example, Broadcom invests more than EUR […] million per year in R&D for SoCs (as well as FE chips and WiFi chipsets).225 Broadcom has also stated that “semiconductors markets are characterized by customers requiring high levels of investment and uncertain returns”.226 According to Broadcom, these challenges are particularly stringent in STB and residential gateway SoCs due to the markets’ maturity and, in the case of STB SoCs, alleged diminishing demand.227 Broadcom considers that high development costs are the main reason for a number of consolidations and market exits, in particular the exit of STMicroelectronics, Broadcom’s closest competitor in STB SoCs.228

(155) Second, there is a scarcity of specialised engineering and other talented employees in the semiconductor sector, including in SoCs.229 As such, even if a company were committed to investing resources in R&D, it may still find it challenging to find the workforce required to develop SoCs.

(156) Third, respondents noted that gaining access to the IP rights that cover SoCs and other components constitutes a significant barrier to entry and indicated that Broadcom is a significant patent holder.230 Moreover, several market participants have pointed to tactics by Broadcom in the licencing policy to its IP as exacerbating these barriers to entry. Intel explained that it is aware that “Broadcom has threatened bringing patent claims against companies considering entry into the STB silicon market,231 in which Broadcom possess a market share of nearly 100%.”232 MediaTek confirmed that “Broadcom (and its predecessor entity Avago before it) has introduced several litigations against MediaTek and a number of other electronics companies in the US and Europe, including several of MediaTek’s customers” […].233 Broadcom’s own patent ownership and licensing conduct therefore contributes to elevating barriers to entry.

(157) Fourth, respondents indicated that economies of scale are important to profitably start or continue supplying SoCs for STBs and residential gateways. Economies of scale are important, in particular, to be able to spread the material research and development costs associated with developing these products.234 This factor, therefore, reinforces established positions and compounds barriers to entry.

(158) Fifth, respondents indicated that having an established relationship with customers can provide an advantage to existing suppliers.235 Accordingly, new suppliers or suppliers seeking to expand sales with new customers must overcome customers’ preference for incumbent suppliers, making new entry or expansion less likely.

(159) Sixth, the fact that the markets at stake are unlikely to expand significantly in the future236 increases the importance of the barriers to entry above, given that it makes entry relatively less attractive.

(160) In its SO Response, Broadcom recognises some of the industry features included in the description above but claims that the Commission does not recognise the alleged efficiencies brought about by the agreements (see in this regard Section 8.5.2.3).

(161) Broadcom admits that the industry is characterised by high fixed costs and claims that it makes investments when they are underpinned by a degree of certainty about future order volumes.237 According to Broadcom, the high fixed-costs in the industry have led Broadcom and partner OEMs to collaborate in order to reduce them and create a basis for timely delivery of new products. 238

(162) Broadcom further disputes its interference with other market players and maintains that this is not sufficiently substantiated. Moreover, it also maintains that if its IP is essential to compete in its market segment, the incremental effect of its conduct on rivals’ ability to compete would be minimal.239

(163) The Commission notes that Broadcom’s allegations confirm the description of the barriers to entry of the SO and the substantial investment required. Broadcom does not dispute that there are staff shortages in the market, one of the aspects identified as a barrier to entry.

(164) Broadcom’s allegation about the existence of high costs in the industry does not dispute the relevance of economies of scale in the market, but rather attempts to provide a justification to its conduct. Such alleged justification does not alter the finding of dominance and will be assessed as part of the Commission’s analysis of objective justification (see section 8.5.2.3 below).

(165) Finally, Broadcom’s claim that the allegations on access to IP rights are not sufficiently substantiated cannot be accepted. There are several references to comments submitted by different market players in recital (156) of this Decision. As indicated in that same recital, on a prima facie basis, Broadcom is one of the most significant owners of IP rights in the industry and these IP rights (which Broadcom vigorously enforces) operate as a barrier to entry or to expansion.240

8.4.5. Countervailing buyer power

(166) The preliminary factual and legal analysis set out in this section indicates that Broadcom’s customers have insufficient countervailing bargaining power.241

(167) First, the downstream markets are fragmented. For STBs, as indicated in section 6 above, the main four OEMs accounted for approximately half of the global sale revenues at the end of 2017, with significant discrepancies in shares: [OEM A] [20- 30]%, [OEM E] [10-20]%, [OEM B] [5-10]% and [OEM D] [5-10]%. The rest of the market is accounted for by a large number of smaller players. For residential gateways, these four players accounted for approximately two fifths of the market in 2017: [OEM A] [20-30]%, [OEM E] [5-10]%, [OEM B] [0-5]% and [OEM D] [5-10]%. Chinese manufacturers and a large number of small players accounted for the rest of the market.

(168) Second, there are few alternatives to Broadcom in both STB and residential gateway SoCs and Broadcom enjoys significantly broader scale than its competitors. Thecustomers’ ability to exercise commercial pressure on Broadcom when selecting chipset suppliers is therefore limited.

(169) Most OEMs have confirmed having insufficient buyer power to impose their requests on Broadcom. OEMs have indicated that this is the result of a number of factors including Broadcom’s leadership and unique position enabling it to ensure timely technical and engineering support and delivery, the limited number of alternative suppliers available and Broadcom’s established relations with service providers.242 OEMs have indicated that their position in this respect concerns all SoCs and applies both to SoCs for STBs and for residential gateways.243 For example, […] mentioned that “Broadcom has a strong market position with close working relationships with operators and OEMs. Broadcom is often the incumbent and specified by the operators in their RFQs. This often leaves little room to negotiate with Broadcom”.244

(170) Broadcom argues that the SO’s failure to take into account the role of service providers undermines the dominance assessment for all product lines. Broadcom describes service providers as “kingmakers” in the industry and argues that each of them represents a significant source of demand from the perspective of the OEMs and also for the SoCs and their products. It therefore considers that service providers can credibly threaten to delay or reduce orders to obtain better pricing terms.245

(171) Broadcom’s claims are unfounded. The role of Service Providers has been sufficiently assessed throughout the SO and in this Decision.246 In any event, the Commission notes that in stark contrast with market concentration at the level of SoCs, service provider demand at global level is highly fragmented. In the EEA alone, there are a minimum of 120 Internet service providers.247 Even assuming that the largest among those service providers had a certain degree of market power, which Broadcom has failed to demonstrate, there would remain a large number of small to medium-sized service providers, which are not able to counteract the market power of Broadcom. 248

(172) Finally, there are limited alternatives to Broadcom in each of the concerned markets and Broadcom enjoys broader scale than other players. Broadcom is the leading company in all markets concerned with a considerable distance to the other market players. This is evidenced by the tables in recitals (117) and (131), where Broadcom’s edge over its competitors is shown.

8.4.6. Conclusion on dominance

(173) In light of the preliminary factual and legal analysis set out above, the Commission concludes that Broadcom is prima facie dominant in the following worldwide markets:(a) STB SoCs;249(b) SoCs for xDSL residential gateways;250 and(c) SoCs for fibre residential gateways.

8.5. Abuse

8.5.1. Principles

(174) The fact that an undertaking holds a dominant position is not in itself contrary to the competition rules. However, an undertaking enjoying a dominant position is under a special responsibility, irrespective of the causes of that position, not to allow its conduct to impair genuine undistorted competition on the internal market.251

(175) The concept of abuse is an objective concept relating to the behaviour of an undertaking in a dominant position which is such as to influence the structure of a market where, as a result of the very presence of the undertaking in question, the degree of competition is weakened and which, through recourse to methods different from those which condition normal competition in products or services on the basis of the transactions of commercial operators, has the effect of hindering the maintenance of the degree of competition still existing in the market or the growth of that competition.252

(176) For the purposes of establishing an infringement of Article 102 TFEU, it is not necessary to demonstrate that the abuse in question had a concrete effect on the markets concerned. It is sufficient in that respect to demonstrate that the abusive conduct of the undertaking in a dominant position is capable of having such an effect.253

(177) It follows from the nature of the obligations imposed by Article 102 TFEU that, in specific circumstances, undertakings in a dominant position may be deprived of the right to adopt a course of conduct or take measures which are not in themselves abuses and which would even be unobjectionable if adopted or taken by non-dominant undertakings.254 In addition, the strengthening of the position of an undertaking may be an abuse and prohibited under Article 102 TFEU, regardless of the means and procedure by which it is achieved, and even irrespective of any fault.255

(178) Article 102 TFEU is aimed not only at practices which may cause prejudice to consumers or individual competitors directly, but also at those which are detrimental to them through their impact on an effective competition structure.256 This is because the competition rules laid down in the Treaty aim to protect not only the interests of competitors or of consumers, but also the structure of the market and, in so doing, competition as such.257

(179) However, not every exclusionary effect is necessarily detrimental to competition. Competition on the merits may, by definition, lead to the departure from the market or the marginalisation of competitors that are less efficient and so less attractive to consumers from the point of view of, among other things, price, choice, quality or innovation.258

(180) The list of abusive practices contained in Article 102 TFEU does not exhaust the possible methods of abusing a dominant position prohibited by the TFEU.259 For the purposes of this case, the following two sets of principles are particularly relevant.

(181) First, an undertaking which is in a dominant position on a market and ties purchasers– even if it does so at their request – by an obligation or promise on their part to obtain all or most of their requirements exclusively from the said undertaking abuses its dominant position within the meaning of Article 102 TFEU, whether the obligation in question is stipulated without further qualification or whether it is undertaken in consideration of the grant of a rebate. The same applies if the said undertaking, without tying the purchasers by a formal obligation, applies, either under the terms of agreements concluded with these purchasers or unilaterally, a system of exclusivity rebates, that is to say discounts conditional on the customer’s obtaining all or most of its requirements from the undertaking in a dominant position.260

(182) In that context, it should be recalled that an undertaking in a dominant position may not justify the grant of a rebate subject to a quasi-exclusive purchase condition by a customer in a certain segment of a market by the fact that that customer remains free to obtain supplies from competitors in other segments.261 The customers on the foreclosed part of the market should have the opportunity to benefit from whatever degree of competition is possible on the market and competitors should be able to compete on the merits for the entire market and not just for a part of it.262

(183) As regards the threshold for a purchase condition to be qualified as a quasi-exclusivity condition, it is recalled that the percentage of 80% is sufficient to constitute “most” of a company’s requirements but that also lower purchasing obligations have already been found to constitute quasi-exclusivity conditions.263

(184) Second, Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement prohibit not only practices by an undertaking in a dominant position which tend to strengthen that position,264 but also the conduct of an undertaking with a dominant position in a given market that tends to extend that position to a neighbouring but separate market by distorting competition.265 Therefore, the fact that a dominant undertaking’s abusive conduct has its adverse effects on a market distinct from the market where it is dominant does not preclude the application of Article 102 TFEU or Article 54 of the EEA Agreement.266 It is not necessary that the dominance, the abuse and the actual or potential effects of the abuse are all in the same market.

(185) It is open to a dominant undertaking to show that its conduct is objectively necessary or that the potential foreclosure effect that it brings about may be counterbalanced, or outweighed, by advantages in terms of efficiencies that also benefit consumers.267

(186) Although the burden of proof of the existence of circumstances that constitute an infringement of Article 102 TFEU is borne by the Commission, it is for a dominant undertaking to raise any plea of objective justification or efficiency defence and to support it with arguments and evidence.268

8.5.2. Application to this case

(187) For the reasons set out below, the Commission concludes that, prima facie, Broadcom’s conduct breaches Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement, thus giving rise “at first sight” to serious doubts as to its compatibility with those provisions.

8.5.2.1. Legal qualification of Broadcom’s conduct

(188) In the sections that follow, the Commission will present its assessment as regards the reasons why certain provisions included in the Agreements can be considered as amounting to exclusivity-inducing provisions. These exclusivity-inducing provisions can be grouped into two different types of restrictions of competition, namely: (i) exclusivity and quasi-exclusivity arrangements; and (ii) leveraging restrictions. Each of these types of restriction will be discussed in sections 8.5.2.1.A and 8.5.2.1.B below. In Section 8.5.2.1.C below, the Commission addresses Broadcom’s arguments on the legal qualification of the Agreements. The Commission’s conclusions as regards the prima facie legal qualification of Broadcom’s conduct are set out in section 8.5.2.1.D below.

(A.) Exclusivity and quasi-exclusivity arrangements

(189) The Commission considers that all of the Agreements contain exclusivity or quasi- exclusivity arrangements. That is: (i) obligations or promises to obtain products in which Broadcom is dominant exclusively or almost exclusively from Broadcom (“exclusive purchasing arrangements”); or (ii) provisions that make the granting of certain advantages conditional on the customer obtaining products in which Broadcom is dominant exclusively or almost exclusively from Broadcom (“advantages conditional on exclusivity”).

(190) Subsections A.i to A.vi below explain why the Commission considers that certain provisions within each of the Agreements constitute, prima facie, exclusivity or quasi- exclusivity arrangements. Subsection A.vii sets out the Commission’s provisional conclusions as regards these exclusivity and quasi-exclusivity arrangements.

(191) As a preliminary remark, the Commission considers at this stage that the various provisions described in sections A.i. to A.vi. below amount to a system of exclusivity and quasi-exclusivity arrangements, capable of restricting competition (see further section 8.5.2.2 below). As such, it is neither necessary nor practical definitively to categorise each individual provision as either an exclusive purchasing arrangement or a provision granting advantages conditional on exclusivity since many of the Agreements described below establish arrangements that are capable of being considered as both exclusive purchasing arrangements and advantages conditional on exclusivity.269

(A.i.) [OEM A] CSA

(192) Under the [OEM A] CSA, [OEM A] commits to certain arrangements with respect to three product markets in which Broadcom is prima facie dominant: (i) STB SoCs, (ii) xDSL residential gateway SoCs and (iii) fibre residential gateway SoCs.

(193) In particular, [OEM A] commits to purchase from Broadcom [80-100]% of its requirements for three products in which Broadcom is prima facie dominant: (i) SoCs for 4K STBs;270 (ii) SoCs for xDSL residential gateways;271 and (iii) SoCs for fibreresidential gateways.272 This clause therefore amounts to a promise by [OEM A] to obtain exclusively its requirements from Broadcom in the case of SoCs for xDSL and fibre residential gateways and to obtain (at least) almost exclusively its requirements from Broadcom in the case of STB SoCs, given that 4K STBs amounted to [80-100]% of [OEM A]’s sales of STBs in the years 2017-2019.273