Commission, June 27, 2017, No 39740

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

Google Search (Shopping)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty1, and in particular Articles 7(1), 23(2) and 24(1) thereof,

Having regard to the Commission Decisions of 30 November 2010 and of 14 July 2016 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given the undertaking concerned the opportunity to make known its views on the objections raised by the Commission pursuant to Article 27(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 and Article 12 of Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 of 7 April 2004 relating to the conduct of proceedings by the Commission pursuant to Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty2,

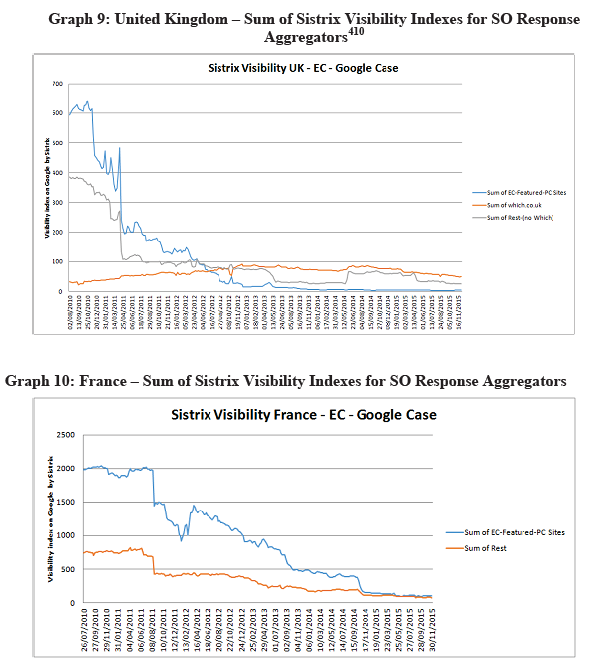

After consulting the Advisory Committee on Restrictive Practices and Dominant Positions, Having regard to the final report of the Hearing Officer in this case,

Whereas:

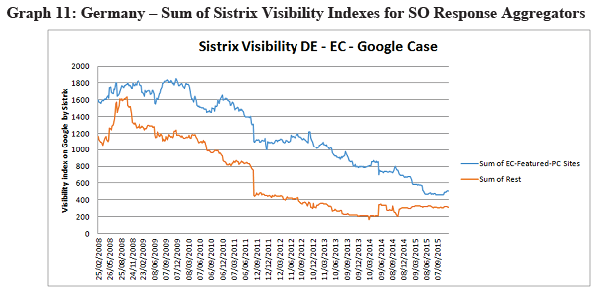

1. INTRODUCTION

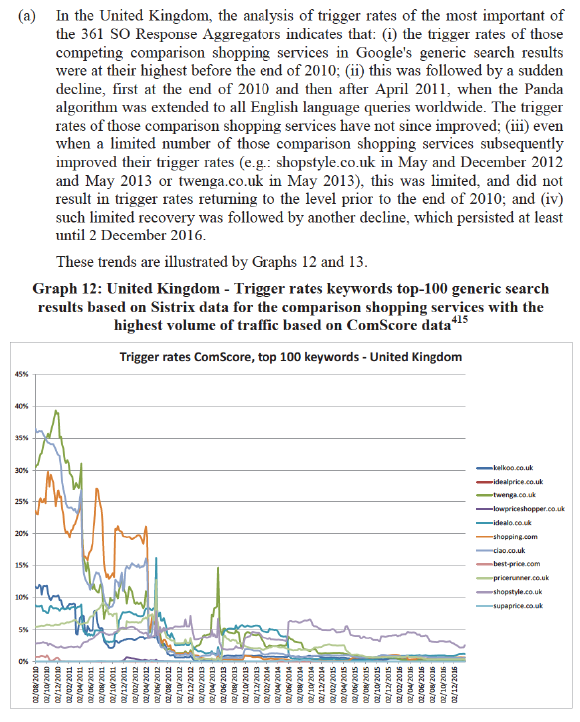

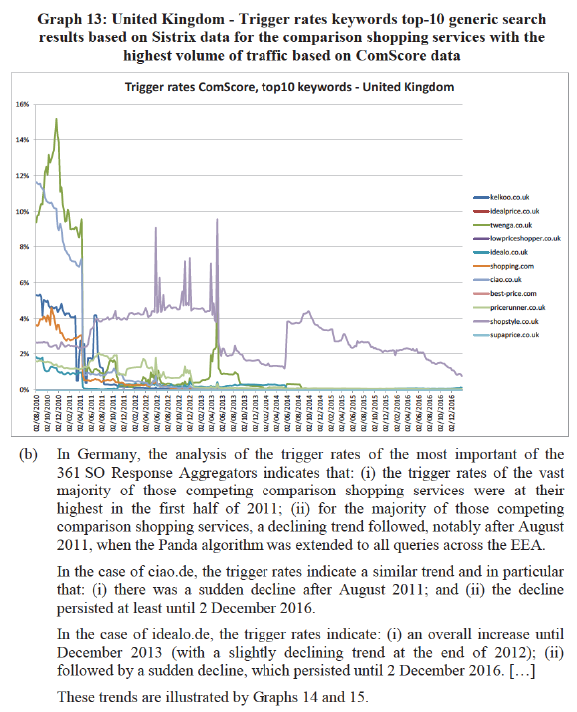

(1) This Decision is addressed to Google Inc. (“Google”) and to Alphabet Inc. (“Alphabet”).

(2) The Decision establishes that the more favourable positioning and display by Google, in its general search results pages, of its own comparison shopping service compared to competing comparison shopping services (the “Conduct”) infringes Article 102 of the Treaty and Article 54 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (“EEA Agreement”).3

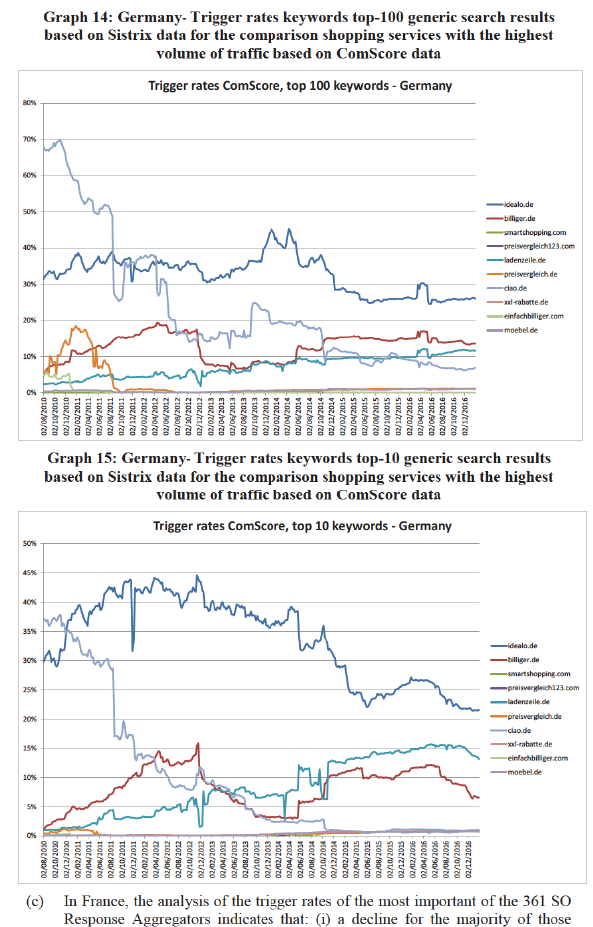

(3) This Decision is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of Google’s business activities. Section 3 summarises the procedure relating to the proceedings in this case to date. Section 4 addresses Google's allegations that the Commission's investigation has suffered from procedural irregularities. Sections 5 to 11 set out the Commission’s conclusions regarding the relevant product and geographic markets, Google's dominant position, Google's abuse of that dominant position, the Commission's jurisdiction, the effect of the abuse on trade between Member States and between Contracting Parties to the EEA Agreement, the duration of the abuse and the addressees of this Decision. Sections 12 to 14 conclude by describing the remedies and periodic penalty payments necessary to bring the infringement to an end and explaining the amount of the fine.

2. GOOGLE'S BUSINESS ACTIVITIES

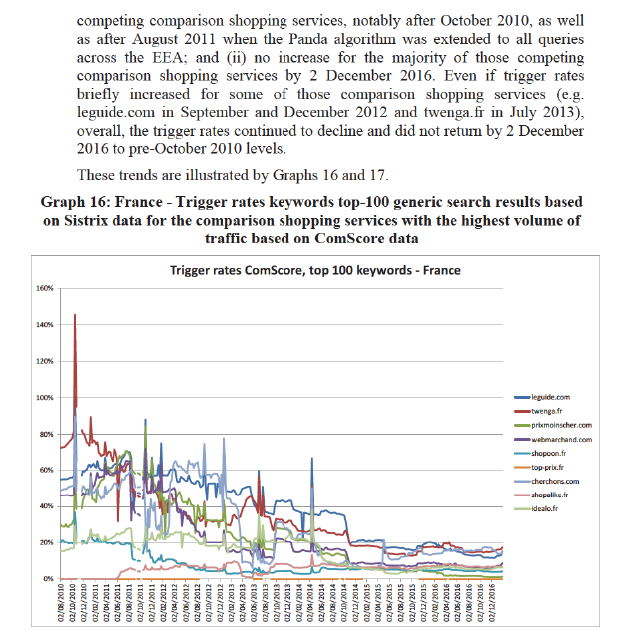

2.1. The undertaking

(4) Google is a multinational technology company based in the United States of America (“the US”), specialising in internet-related services and products that include online advertising technologies, search, cloud computing, software and hardware. It offers various services in the territories of all the Contracting Parties to the EEA Agreement.

(5) In August 2015, Google announced its intention to create a new holding company, Alphabet. The reorganisation was completed on 2 October 2015. Since that date, Google has been a wholly-owned subsidiary of Alphabet, which has continued to be the umbrella company for the internet interests of Alphabet.

(6) According to the consolidated financial statements of Alphabet, its turnover was USD 90 272 million (approximately EUR 81 597 million4) for the year running from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2016.5

2.2. Overview of Google's business activities

(7) Google’s business model is based on the interaction between the online products and services it offers free of charge and its online advertising services from which it generates the main source of its revenue.6

2.2.1. Google Search

(8) Google’s flagship online service is its general search7 engine, Google Search, which is accessible either through Google’s main website in the US (www.google.com), or through localised websites. Google also powers the search functions of certain third party websites.

(9) Google Search allows users to search for information across the internet. Google Search exists for static devices (personal computers and laptops) and for mobile devices (smartphones and tablets). While the user interface may vary depending on the type of device, the underlying technology is essentially the same.

(10) When a user enters a keyword or a string of keywords (a “query”) in Google Search, Google’s general search results pages return different categories of search results, including generic search results8 (as described in section 2.2.2) and specialised search results9 (as described in section 2.2.4). In addition, Google Search may return a third category of results, namely online search advertisements (as described in section 2.2.3).

(11) When a user enters a query, Google’s programmes essentially run two sets of algorithms: generic search algorithms and specialised search algorithms.10

(12) Google’s generic search algorithms are designed to rank pages containing any possible content. Google applies these algorithms to all types of pages, including the web pages of competing specialised search services. By contrast, specialised search algorithms “are specifically optimized for identifying relevant results for a particular type of information”,11 such as news, local businesses or product information.

(13) The results of these two sets of algorithms – the generic search results and the specialised search results – appear together on Google’s general search results pages.

2.2.2. Generic search results

(14) Generic search results typically appear on the left side of Google’s general search results pages in the form of blue links with short excerpts (“snippets”) in order of their “web rank”. Generic search results can link to any page on the internet, including web pages of specialised search services competing with Google's specialised search services.

(15) The delivery of generic search results involves three automated processes: crawling, indexing and serving.12 Crawling is the process by which Google discovers new and updated web pages. Indexing is the process by which web pages and their content are catalogued and added to the Google index. Serving is the process by which, when a user enters a query, Google’s programmes check the index for web pages that match the query, determine their relevance to the query and “serve” the results to the user.

(16) To rank generic search results in response to a query, Google uses algorithms. It relies in particular on an algorithm called PageRank, which is “a method for rating Web pages objectively and mechanically, effectively measuring the human interest and attention devoted to them”.13 PageRank essentially measures the importance of a web page based on the number and quality of links to that page, the underlying assumption being that more important websites are likely to receive more links from

other websites. Google applies a variety of adjustment mechanisms to the results of PageRank to improve the relevance of the generic search results on its general search results pages. PageRank and the adjustment mechanisms together determine the rank of a web page in generic search results on Google's general search results pages.

(17) Google does not charge websites ranked in generic search results on its general search results pages and does not accept any payment that would allow websites to rank higher in these results.

2.2.3. Online search advertising results

(18) In response to a user’s query on Google Search, Google’s general search results pages may also return search advertisements drawn from Google’s auction-based online search advertising platform, AdWords (“AdWords results”).

(19) AdWords results are not limited to specific categories of products, services or information. They typically appear on general search results pages above or below generic search results with a label informing users of their nature as advertisements (for example, “Ads”).14 AdWords results can be purchased by any advertiser and are not limited to particular categories of advertisers.

(20) The appearance of AdWords results in response to a user’s query involves two main elements. First, AdWords identifies a pool of relevant search advertisements by matching the keywords on which advertisers have associated their search advertisements with the keywords used in the query. Second, AdWords ranks the relevant search advertisements within the pool based on their “Ad Rank”. The ranking of a search advertisement depends on two factors: the maximum price an advertiser has indicated it is willing to pay for each click on its search advertisement in a second-price auction15 and the quality rating of that search advertisement (known as “Quality Score”). The Quality Score is based among other things on a search advertisement’s predicted click-through rate.16 AdWords results that appear the most visibly on Google’s general search results pages are those with the highest Ad Rank scores.17

(21) When a user clicks on an AdWords result, Google receives remuneration for that click from the advertiser owning the website to which the user is directed (known as the “pay per click” system).

(22) AdWords results allow advertisers to lead interested users entering queries on Google Search to their websites, including in circumstances where these websites would otherwise not rank highly in generic search results on Google's general search results pages. Specialised search services competing with services provided by Google often also purchase AdWords results.

2.2.4. Specialised search results

(23) In response to a user query, Google’s general search results pages may also return specialised search results from Google’s specialised search services. In most instances, specialised search results are displayed with attractive graphical features, such as large scale pictures and dynamic information. Specialised search results in a particular category are positioned within sets referred to by Google as “Universals” or “OneBoxes”.18 They are in most instances positioned above generic search results, or among the first of them.

(24) Google operates several search services that can be described as “specialised” because they group together results for a specific category of products, services or information (for example, “Google Shopping”, “Google Finance”, “Google Flights”, “Google Video”).19 In addition to the results returned in “Universals” or “OneBoxes”, Google's specialised search services can also be accessed through menu-type links displayed at the top of Google's search results pages.

(25) Certain of Google’s specialised search services are based on paid inclusion. Third party websites have to enter into an agreement with Google in order to be listed in the search results of such a specialised search service. In most instances, such an agreement provides for a payment based on a pay per click system. This is the case for instance for Google Shopping (see section 2.2.5).

2.2.5. Google's comparison shopping service

(26) Google’s comparison shopping service is one of Google’s specialised search services. In response to queries, it returns product offers from merchant websites, enabling users to compare them.

(27) Google launched the first version of its comparison shopping service in December 2002 in the US under the brand name “Froogle”. Froogle operated as a standalone website. Merchants did not have to pay to be listed in Froogle as it was monetised by advertisements. Google launched Froogle in the United Kingdom in October 200420 and in Germany in November 2004.21

(28) In April 2007, Google renamed Froogle as “Google Product Search”22 and subsequently launched along the standalone Google Product Search website a dedicated “Universal” or “OneBox” for Google Product Search, referred to as the “Product Universal”. Google did not, however, change the business model of its comparison shopping service: like Froogle, merchants did not have to pay to be listed in Google Product Search as it was monetised by advertisements.

(29) The Product Universal comprised specialised search results from Google Product Search, accompanied by one or several images and additional information such as the price of the relevant items. The results within the Product Universal, including the clickable images, in most cases led the user to the standalone Google Product Search websites. There was also a header link leading to the main website of Google Product Search.

(30) The Product Universal was launched in October 2007 in the US, in January 2008 in the United Kingdom and Germany, in October 2010 in France and in May 2011 in Italy, the Netherlands and Spain.23

(31) In May 2012, Google renamed Google Product Search as “Google Shopping” and revamped the Product Universal which was renamed first “Commercial Unit” and then “Shopping Unit”. At the same time, Google also changed the business model of its comparison shopping service (both the standalone website and the Universal) to a “paid inclusion” model, in which merchants pay Google when their product is clicked on in Google Shopping, to more closely reflect the industry standard.24

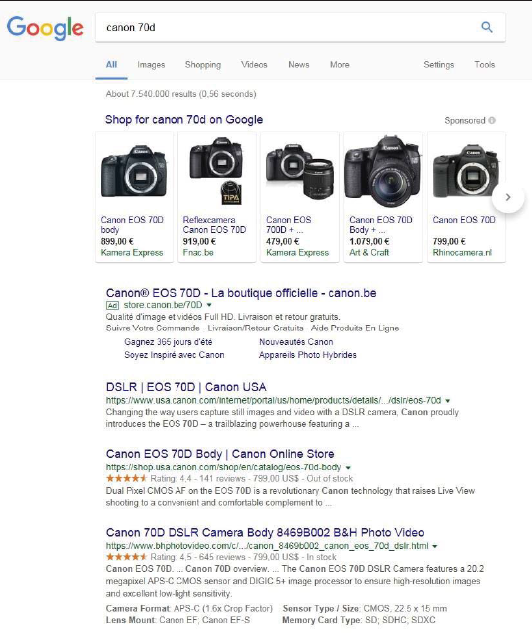

(32) In the same way as the Product Universal comprised specialised search results from Google Product Search, the Shopping Unit comprises specialised search results from Google Shopping, as illustrated by the screenshot below25. Those results are commercially named “Product Listing Ads” – PLAs. Unlike for the Product Universal, however, the results within the Shopping Unit generally lead users directly to the pages of Google's merchant partners on which the user can purchase the relevant item.

(33) The Shopping Unit and the standalone Google Shopping website were first launched in the US in May 2012, with the transition completed by autumn 2012.

(34) Subsequently, the Shopping Unit was launched on Google's domains in the EEA as follows: (i) in February 2013 in the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom; and (ii) in November 2013 in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Poland and Sweden.26 Google also started running a Shopping Unit experiment in Ireland in September 2016.27

(35) As for the standalone Google Shopping website, it was launched (i) in February 2013 in the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom;28 (ii) in September 2016 in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Poland and Sweden; and (iii) in Ireland in January 2017.29

2.2.6. Other Google products and services

(36) Google offers a number of other online products and services free of charge, including an open-source operating system for smartphones and tablets (“Android”), an app store for the Android operating system (“Google Play”), an internet browser (“Google Chrome”), a web-based email account service (“Gmail”), a web mapping service (“Google Maps”), a file storage and editing service offering a suite of office applications (“Google Drive”), an instant messaging and video chat platform (“Google Hangouts”), a set of search tools (“Google Toolbar”) and a video-sharing website (“YouTube”).

(37) Google also sells hardware products such as digital media players (“Chromecast”), laptops (“Chromebooks”), smartphones and tablets (“Google Nexus”).

3. PROCEDURE

(38) The Commission has received a number of complaints against Google pursuant to Article 7(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003. In addition, a number of cases pending before competition authorities of the Member States have been re-allocated to the Commission.

(39) On 3 November 2009, Infederation Ltd. (“Foundem”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. That complaint was replaced by a new version submitted by Foundem on 2 February 2010. On 10 February 2010, the Commission sent Google a non-confidential version of the complaint. On 3 May 2010, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(40) On 22 January 2010, pursuant to Article 12 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, the Bundeskartellamt (Germany) exchanged information with the Commission on a complaint against Google lodged by Ciao GmbH (“Ciao”). Ciao’s complaint was re- allocated to the Commission on 22 January 2010 in accordance with the Commission’s Notice on cooperation within the Network of Competition Authorities.30 On 10 February 2010, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 20 March 2010, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(41) On 2 February 2010, eJustice.fr (“eJustice”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 10 February 2010, the Commission sent Google a non- confidential version of the complaint. On 3 May 2010, Google provided comments on the complaint. On 22 February 2011, eJustice’s parent company 1plusV lodged with the Commission a supplement to eJustice’s complaint and joined eJustice’s complaint. On 1 April 2011, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the supplement to Google. On 16 September 2011, Google provided comments on the supplement.

(42) On 26 October 2010, the Verband freier Telefonbuchverleger (“VfT”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 1 December 2010, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 14 January 2011, Google provided comments on the complaint. On 24 January 2011, VfT submitted a supplement to its complaint.

(43) On 30 November 2010, the Commission initiated proceedings against Google pursuant to Article 2(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 in relation to a number of practices. The initiation of proceedings relieved the competition authorities of the Member States of their competence to apply Articles 101 and 102 of the Treaty to those practices.

(44) As a result, on 14 December 2010, the Bundeskartellamt transferred to the Commission a joint complaint against Google lodged by the Bundesverband Deutscher Zeitungsverleger (“BDZV”) and the Verband Deutscher Zeitschriftenverleger (“VDZ”), and complaints against Google lodged by Euro-Cities AG (“Euro-Cities”) and Hot Maps Medien GmbH (“Hot Maps”). Google had already provided comments on these complaints, except for that lodged by Hot Maps. On 1 April 2011, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of Hot Maps’ complaint to Google. On 16 September 2011, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(45) On 17 January 2011, the Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato (Italy) also transferred to the Commission a complaint against Google lodged by Mr. Sessolo (“nntp.it”). On 13 April 2011, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 17 September 2011, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(46) On 31 January 2011, Elf B.V. (“Elf”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 1 April 2011, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 16 September 2011, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(47) On 31 March 2011, Microsoft Corporation (“Microsoft”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 1 April 2011, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 16 September 2011, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(48) On 27 June 2011, Twenga SA (“Twenga”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695/EU of the President of the European Commission of 13 October 2011 on the function and terms of reference of the hearing officer in certain competition proceedings (“Decision 2011/695”).31 The Hearing Officer approved Twenga’s application on 11 July 2011.

(49) On 19 December 2011, La Asociación de Editores de Diarios Españoles (“AEDE”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 25 January 2012, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 6 March 2012, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(50) On 23 January 2012, Twenga lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 7 February 2012, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 28 February 2012 and 5 March 2012, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(51) On 20 February 2012, Company E, a company wishing to remain anonymous, submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer rejected Company E’s application on 28 February 2012.

(52) On 26 March 2012, Yelp Inc. (“Yelp”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695, in the event that the Commission issued a statement of objections. The Hearing Officer acknowledged on 28 March 2012 that Yelp met the criteria to be heard as an interested third party in the proceedings.

(53) On 29 March 2012, Streetmap EU Ltd (“Streetmap”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 12 April 2012, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 23 May 2012, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(54) On 30 March 2012, Expedia Inc. (“Expedia”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 12 April 2012, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 24 May 2012, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(55) In April 2012, Cases 39.768 (Ciao), 39.775 (eJustice/1PlusV), 39.845 (VfT), 39.863 (BDZV&VDZ), 39.866 (Elfvoetbal), 39.867 (Euro-Cities/HotMaps), 39.875 (nntp.it), 39.897 (Microsoft) and 39.975 (Twenga) were merged with Case 39.740 (Foundem). The documents that had been registered in the aforementioned case files were subsequently put into a single file under case number COMP/C-3/39.740 – Google Search. The Commission continued the procedure under case number COMP/C-3/39.740.

(56) On 1 April 2012, Odigeo Group (“Odigeo”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 12 April 2012, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 24 May 2012, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(57) On 2 April 2012, TripAdvisor Inc. (“TripAdvisor”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 12 April 2012, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 24 May 2012, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(58) On 27 June 2012, Nextag Inc. (“Nextag”) and Guenstiger.de GmbH (“Guenstiger”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 2 August 2012, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 8 September 2012, Nextag and Guenstiger submitted a supplement to their complaint. On 22 September 2012, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(59) On 17 July 2012, the Hearing Officer approved an application from MoneySupermarket.com Group PLC (“MoneySupermarket”) to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695.

(60) On 11 January 2013, Visual Meta GmbH (“Visual Meta”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 22 February 2013, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 4 June 2013, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(61) On 30 January 2013, the Initiative for a Competitive Online Marketplace (“ICOMP”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 22 February 2013, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 1 June 2013, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(62) On 6 March 2013, Bureau Européen des Unions des Consommateurs AISBL (“BEUC”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved BEUC’s application on 26 March 2013.

(63) On 13 March 2013, the Commission adopted a Preliminary Assessment addressed to Google under Article 9 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 (“Preliminary Assessment”). In the Preliminary Assessment, the Commission took the view that Google engages in the following business practices that may infringe Article 102 of the Treaty and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement:

– The favourable treatment, within Google’s general search results pages, of links to Google’s own specialised search services as compared to links to competing specialised search services (“first business practice”);

– The copying and use by Google without consent of original content from third party websites in its own specialised search services (“second business practice”);32

– Agreements that de jure or de facto oblige websites owned by third parties (referred to in the industry as “publishers”) to obtain all or most of their online search advertisement requirements from Google (“third business practice”); and

– Contractual restrictions on the management and transferability of online search advertising campaigns across online search advertising platforms (“fourth business practice”).

(64) On 25 March 2013, Organización de Consumidores y Usuarios (“OCU”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved OCU’s application on 8 April 2013. On 23 February 2017, OCU informed the Commission that it no longer wished to be considered as an interested third party on its own, but would only be involved in the case through BEUC.

(65) Google did not agree with the legal analysis in the Preliminary Assessment and contested the assertion that any of the business practices described in it infringe Article 102 of the Treaty and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement. It nevertheless offered three sets of commitments pursuant to Article 9 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 to address the Commission’s competition concerns regarding the four business practices identified in the Preliminary Assessment. The first set of commitments was submitted to the Commission on 3 April 2013, the second set of commitments on 21 October 2013 and the third set of commitments on 31 January 2014.

(66) On 31 March 2014, BEUC lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 2 April 2014, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google.

(67) On 15 April 2014, Open Internet Project (“OIP”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 1 July 2014, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 18 August 2014, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(68) On 16 May 2014, Deutsche Telekom AG (“Deutsche Telekom”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 27 May 2014, Deutsche Telekom submitted further information on the allegations covered by its complaint. On 25 June 2014, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 22 September 2014, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(69) On 2 June 2014, Yelp lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 25 June 2014, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 4 December 2014, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(70) On 24 July 2014, HolidayCheck AG (“HolidayCheck”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 1 September 2014, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 8 November 2014, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(71) Between 27 May 2014 and 11 August 2014, the Commission sent letters pursuant to Article 7(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 (“the Article 7(1) letters”) to all complainants that had lodged a complaint under the relevant proceedings before 27 May 2014.33 The letters outlined the Commission’s preliminary view that the third set of commitments offered by Google on 31 January 2014 could address the Commission’s competition concerns identified in the Preliminary Assessment. The Commission also informed the complainants in the Article 7(1) letters that it intended to reject their complaints, to the extent that they related to the competition concerns identified in the Preliminary Assessment.

(72) 19 complainants submitted written observations in response to the Article 7(1) Letters (“the Article 7(1) replies”).34 Streetmap and nntp.it did not submit written observations to the Article 7(1) letters addressed to them by the Commission within the time-limit set within the letters. Streetmap’s and nntp.it's complaints were therefore deemed to have been withdrawn pursuant to Article 7(3) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004.

(73) Having received and analysed the written observations of the 19 complainants, the Commission considered that it was not in a position to adopt a decision under Article 9 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 making binding Google’s third set of commitments in relation to the four business practices covered by the Preliminary Assessment. The Commission brought this to the attention of Google on 4 September 2014.35

(74) On 26 January 2015, Trivago GmbH (“Trivago”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 16 September 2015, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the complaint to Google.

(75) On 13 April 2015, Company AC, a company that wishes to remain anonymous, submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved Company AC’s application on 21 April 2015. The Hearing Officer also accepted Company AC's request for anonymity.

(76) On 15 April 2015, the Commission reverted to the procedure under Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 in relation to the Conduct36 and adopted a Statement of Objections addressed to Google (“the SO”). In the SO, the Commission reached the provisional conclusion that the Conduct constitutes an abuse of a dominant position and, therefore, infringed Article 102 of the Treaty.

(77) On 15 April 2015, News Corporation (“News Corp”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 7 October 2015, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the complaint to Google.

(78) On 24 April 2015, FairSearch Europe (“FairSearch”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved FairSearch’s application on 8 May 2015.

(79) On 27 April 2015, the Commission granted Google access to file.

(80) On 8 May 2015, SARL Acheter moins cher (“Acheter moins cher”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved Acheter moins cher’s application on 11 May 2015.

(81) On 20 May 2015, S.A. LeGuide.com (“LeGuide”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved LeGuide’s application on 26 May 2015.

(82) On 21 May 2015, Kelkoo SAS (“Kelkoo”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved Kelkoo’s application on 26 May 2015.

(83) On 1 June 2015, Getty Images, Inc. (“Getty”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved Getty’s application on 4 June 2015.

(84) On 10 June 2015, Myriad International Holdings B.V. (“MIH”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved MIH’s application on 18 June 2015.

(85) On 18 June 2015, ICOMP submitted to the Commission a supplement to its complaint of 30 January 2013. On 16 September 2015, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the supplement to Google.

(86) On 2 July 2015, Tradecomet.com Ltd and its parent company Tradecomet LLC (“TradeComet”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 18 September 2015, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 20 November 2015, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(87) On 22 July 2015, the European Technology & Travel Services Association (“ETTSA”) submitted an application to be heard as a third party within the meaning of Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and Article 5 of Decision 2011/695. The Hearing Officer approved ETTSA’s application on 23 July 2015.

(88) On 20 August 2015, VG Media Gesellschaft zur Verwertung der Urheber- und Leistungsschutzrechte von Medienunternehmen mbH (“VG Media”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 13 November 2015, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 22 January 2016, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(89) Between June and September 2015, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the SO to 24 complainants and 10 interested third parties.37 20 complainants and 7 interested third parties submitted written comments on the SO.38

(90) On 27 August 2015, Google submitted its response to the SO (“the SO Response”). Google did not request the opportunity to express its views at an oral hearing pursuant to Article 12(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004.

(91) Between October and November 2015, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the SO Response to 23 complainants and 9 interested third parties.39 14 complainants and 7 interested third parties submitted written comments on the SO Response.40

(92) On 17 April 2016, News Corp lodged an additional complaint against Google with the Commission. On 3 May 2016, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the additional complaint to Google. On 25 July 2016, Google provided comments on News Corp's complaint of 15 April 2015 and additional complaint of 17 April 2016.

(93) On 21 April 2016, Microsoft and Ciao informed the Commission that they were withdrawing the complaints they had lodged against Google.

(94) On 26 April 2016, Getty lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 3 May 2016, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 5 August 2016, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(95) On 4 May 2016, Promt GmbH (“Promt”) lodged a complaint against Google with the Commission. On 14 June 2016, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the complaint to Google. On 10 August 2016, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(96) On 14 July 2016, the Commission initiated proceedings against Alphabet pursuant to Article 2(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and adopted a Supplementary Statement of Objections (“the SSO”) addressed to Google and Alphabet in relation to the Conduct. The SO was annexed to the SSO and was therefore also addressed to Alphabet.

(97) On 27 July 2016, the Commission granted Google and Alphabet access to file.

(98) On 18 August 2016, BDZV and VDZ lodged a supplement to their initial complaints with the Commission. On 16 December 2016, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the supplement to Google and Alphabet.

(99) Between September and October 2016, the Commission sent a non-confidential version of the SSO to 20 complainants and 6 interested third parties.41 9 complainants and 3 interested third parties submitted written comments on the SSO.42

(100) On 3 November 2016, Google and Alphabet submitted their response to the SSO (“the SSO Response”). Google and Alphabet did not request the opportunity to express their views at an oral hearing pursuant to Article 12(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004.

(101) On 28 February 2017, the Commission sent Google and Alphabet a letter of facts (“the LoF”) drawing their attention to pre-existing evidence that was not expressly relied on in the SO and the SSO, but which, on further analysis of the file, could be potentially relevant to support the preliminary conclusion reached in the SO and the SSO. The Commission also informed Google and Alphabet about additional evidence brought to the Commission's attention after the adoption of the SSO that could also be potentially relevant to support the preliminary conclusion reached in the SO and the SSO.

(102) On 1 March 2017, the Commission granted Google and Alphabet access to file.

(103) On 18 April 2017, Google and Alphabet submitted their response to the LoF (“the LoF Response”).43

(104) On 19 May 2017, the Commission sent Google and Alphabet a letter providing updated versions of Tables 37 and Table 64 of the LoF.

(105) On 31 May 2017, Google and Alphabet replied to the Commission's letter of 19 May 2017.

In a submission of 26 June 2017, sent by e-mail from […] to […] at 23:40, Google and Alphabet provided the Commission with additional evidence based on Nielsen user studies allegedly showing "strong competition exercised by merchant platforms in product search and price comparison" essentially on the basis that "For the large majority of product searches, merchant platforms are users' preferred search option and most users start their product searches there." That submission was received after the Advisory Committee on Restrictive Practices and Dominant Positions had given its opinion on the draft Decision in two meetings held on 20 June 2017 and in the morning of 26 June 2017. The Nielsen studies are based on data collected between October and December 2016. The Commission considers it highly unlikely, both given this and Google's general awareness that a Decision pursuant to Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 was a possibility, that Google could not have submitted the studies well in advance of the late evening of 26 June 2017. In accordance with settled case-law, the consultation of the Advisory Committee represents the final stage of the procedure before the adoption of the decision (Joined Cases 100 to 103/80, Musique Diffusion française and others v Commission, EU:C:1983:158, paragraph 35; Joined Cases T-213/01 and T-214/01 Österreichische Postsparkasse and Bank für Arbeit und Wirtschaft v Commission, EU:T:2006:151, paragraph 149). In addition, it follows from Article 11(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 that the undertaking concerned should in principle exercise its right to be heard before the Advisory Committee is consulted.

4. GOOGLE'S ALLEGATIONS THAT THE COMMISSION'S INVESTIGATION SUFFERS FROM PROCEDURAL ERRORS

(106) Google alleges that the Commission's investigation suffers from a number of procedural errors. First, the Commission has breached Google's right to a sound administrative process by failing to assess the evidence properly. Second, the Commission has breached Google's rights of defence by failing to explain its preliminary conclusions in the SO and the SSO properly. Third, the Commission has breached Google's rights of defence by not providing Google with adequate access to minutes of meetings with third parties. Fourth, the Commission has breached Google's rights of defence by failing to provide adequate reasons as to why it reverted to the Article 7 procedure in 2014. Fifth, the Commission has breached Google's rights of defence by failing to provide sufficient information regarding the envisaged remedies.

(107) For the reasons set out in recitals (110) to (111), (114) to (117), (120) to (122) and

(125) to (137), the Commission concludes that Google's right to a sound administrative process and its rights of defence have been respected throughout the investigation.

4.1. The Commission's alleged failure to assess the evidence properly

(108) Google claims that the Commission has failed to assess the facts and evidence properly. In particular, the evidence relied upon by the Commission is of lower probative value than the evidence relied upon by Google.44 Google also claims that the Commission has used outdated information for the finding of dominance.

(109) This claim is unfounded.

(110) First, Google's claim is in effect a challenge to the merits of the Commission's assessment of the Conduct and is therefore irrelevant to the question of whether the Commission has complied with Google's right to a sound administrative process.

(111) Second, the Commission's finding of an infringement does not rely “largely on blog posts, news articles, incomplete traffic data, and unverified assertions by complainants”. Rather, the finding is largely based on a body of evidence of high probative value, including traffic data from Google's logs, user surveys, contemporaneous internal Google documents, experimental analyses and responses to requests of information under Article 18(2) and 18(3) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003.

4.2. The Commission's alleged failure to explain its preliminary conclusions properly

(112) Google claims that its rights of defence have been infringed because, in the SSO, the Commission failed to explain how and why additional items of evidence supported the preliminary conclusions expressed in the SO.45 In addition, the SO and the SSO relied on “vague and obscure terminology” such as “extracted from” and “emanation”, without explaining what those words mean or what they relate to.46

(113) Both claims are unfounded.

(114) First, for each additional piece of evidence, the SSO set out the precise conclusion of the SO that it further supported.

(115) Second, it is apparent from Google's submissions that it well understood the terminology relied on by the SO and the SSO and what that terminology related to.

(116) In the first place, Google explained in the SO Response why it considered that “[i]t is wrong to say that product ads shown in Shopping Units are 'extracted […] from Google’s own comparison shopping service'”.47

(117) In the second place, Google devoted three pages of the SSO Response to explaining why it considered that “the Shopping Unit is not an 'emanation' of a Google comparison shopping unit”.48

4.3. The Commission's alleged failure to provide adequate access to minutes of meetings with third parties

(118) Google claims that its rights of defence have been infringed because the minutes of meetings with third parties that have been provided to it “only list the topics discussed, without recording their substance”.49

(119) This claim is unfounded.

(120) First, in competition proceedings, the Commission is under no general duty to establish records of the discussions that it has had with complainants or other parties during the meetings or telephone conversations held with them.50 The Commission is also not required to make all interviews subject to the formal requirements provided for in Article 19(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, read in conjunction with Article 3 of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004.51 The Commission is required to establish adequate documentation of incriminatory or exculpatory information that is of a certain importance and which bears an objective link with the subject-matter of an investigation.52 Such documentation can take the form of a succinct note in the file to which the undertakings concerned have access.53

(121) Second, the Commission has met that obligation in this case by providing Google with succinct notes containing the minutes of the meetings and telephone conversations held between representatives of the Commission and complainants and other third parties in the context of the investigation. Such minutes mention the undertaking(s) attending the meeting or participating in the telephone conversation (save for certain anonymity requests) and the timing and topic(s) covered by the meeting or telephone conversation.

(122) Third, the discussions that the Commission has had with third parties during the meetings or telephone conversations took place at the request of the third parties and were used by those third parties as an opportunity to urge the Commission to take action on the case quickly. This is confirmed by the fact that: (i) this Decision does not rely on any incriminating information provided by third parties during meetings or telephone conversations; and (ii) Google has not identified, on the basis of the timing and topic(s) covered by the meetings or telephone conversations, any potentially exculpatory information of which the Commission should have made an adequate record accessible.

4.4. The Commission's alleged failure to explain adequately why it reverted to the Article 7 procedure

(123) Google claims that the Commission has failed to provide adequate reasons why it reverted to the Article 7 procedure in 2014.54 Google also claims that the Commission failed to provide it with an opportunity to modify the third set of commitments.55

(124) Both claims are unfounded.

(125) First, the Commission is not required to give reasons as to why it reverted to the Article 7 procedure in 2014. Such an argument was already rejected by the Court of Justice in Alrosa, where it held that “the General Court based its reasoning on the incorrect proposition that the Commission was required to give [Alrosa] reasons for rejecting the joint commitments”.56

(126) Second, and in any event, the Commission has provided adequate reasons as to why it reverted to the Article 7 procedure in 2014. These reasons were already referred to in the SSO.57

(127) In the first place, notwithstanding the third set of commitments, other comparison shopping services may have been unable to compete with Google's own comparison shopping service on the merits, because their results would still have been displayed after results from Google's comparison shopping service.

(128) In the second place, if the auction mechanism for the display of results from competing comparison shopping services foreseen by the third set of commitments had been adopted, this might have led to Google receiving the majority of any profits generated by clicks on these results, whereas Google's own comparison shopping service would not have had to incur any cost for the display of its results.

(129) In the third place, in light of the Article 7(1) replies, the Commission had concerns about the effectiveness of the third set of commitments to address the competition concerns […].

(130) Third, the adequacy of the reasons is not called into question by the position outlined in the press material of 5 February 2014 and in the Article 7(1) letters.

(131) In the first place, the position outlined in the press material of 5 February 2014 and the Article 7(1) letters was necessarily preliminary and potentially subject to change.58

(132) In the second place, a letter of Commission Vice President Almunia to Google of 22 July 2014 anticipated the possible need for Google to offer revised commitments in the light of the replies to the Article 7(1) letters.

(133) Fourth, the Commission was not required to provide Google with an opportunity to modify the third set of commitments. Such an argument was also rejected by the Court of Justice in Alrosa, where it held that “the General Court based its reasoning on the incorrect proposition that the Commission was required to suggest to Alrosa that it offer new joint commitments with De Beers”.59

(134) Fifth, and in any event, the Commission did provide Google with an opportunity to modify the third set of commitments.

(135) In the first place, Google was informed on 4 September 2014 of the reasons why the Directorate-General for Competition considered that the third set of commitments was insufficient to address adequately the Commission's concerns.

(136) In the second place, those reasons were further discussed and explained during a meeting on 8 September 2014 and in various follow-up conversations.

(137) In the third place, in its submission of 7 October 2014, Google indicated that it did not intend to offer revised commitments because to do so “would considerably change the nature of the rival link remedy compared to Google’s February 2014 proposal and […] would necessitate a deeper integration of Google and rival search results”.

4.5. The Commission's alleged failure to provide sufficient information regarding the envisaged remedies

(138 Google claims that the Commission has failed to provide it with all the information to enable it to defend itself as to the necessity and proportionality of the envisaged remedies.60

(139) This claim is unfounded.

(140) First, a statement of objections must set out, even briefly, but in sufficiently clear terms, the measures which the Commission intends to take in order to bring an end to an infringement and give the undertaking concerned all the information necessary to enable it properly to defend itself.61 The SO and the SSO provided all the information necessary to enable Google to defend itself properly regarding the envisaged remedies.

(141) In the first place, the SO and the SSO indicated that Google may be required to position and display competing comparison shopping services in the same way as it positions and displays its own comparison shopping service in its general search results pages.62

(142) In the second place, the SO identified three specific ways in which Google may be required to implement such a requirement.63

(143) Second, the positioning and display of competing comparison shopping services in Google's general search results pages had already been extensively discussed during the Article 9 procedure.64

(144) Third, the Commission was not required to specify further “how its requested remedy is meant to work”. It is for Google and Alphabet, and not the Commission, to make a choice between the several possible lawful ways of positioning and displaying competing comparison shopping services in the same way as Google positions and displays its own comparison shopping service in Google's general search results pages, thereby bringing the infringement to an end.65

5. MARKET DEFINITION

5.1. Principles

(145) For the purposes of investigating the possible dominant position of an undertaking on a given product market, the possibilities of competition must be judged in the context of the market comprising the totality of the products or services which, with respect to their characteristics, are particularly suitable for satisfying constant needs and are only to a limited extent interchangeable with other products or services.66

(146) Moreover, since the determination of the relevant market is useful in assessing whether the undertaking concerned is in a position to prevent effective competition from being maintained and to behave to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors and its customers, an examination to that end cannot be limited solely to the objective characteristics of the relevant services, but the competitive conditions and the structure of supply and demand on the market must also be taken into consideration.67

(147) A relevant product market comprises all those products and/or services which are regarded as interchangeable or substitutable by the consumer, by reason of the products' characteristics, their prices and their intended use.68

(148) The relevant geographic market comprises the area in which the undertakings concerned are involved in the supply and demand of products or services, in which the conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous and which can be distinguished from neighbouring areas because the conditions of competition are appreciably different in those areas.69

(149) Undertakings are subject to three main sources of competitive constraints: demand substitutability, supply substitutability and potential competition. From an economic point of view, for the definition of the relevant market, demand substitution constitutes the most immediate and effective disciplinary force on the suppliers of a given product.70

(150) Supply side substitutability may be taken into account in situations in which its effects are equivalent to those of demand substitution in terms of effectiveness and immediacy. There is supply side substitution when suppliers are able to switch production to the relevant products and market them in the short term without incurring significant additional costs or risks in response to small and permanent changes in relative price.71

(151) The distinctness of products or services for the purpose of an analysis under Article 102 of the Treaty has to be assessed by reference to customer demand.72 Factors to be taken into account include the nature and technical features of the products or services concerned, the facts observed on the market, the history of the development of the products or services concerned and also the undertaking’s commercial practice.73

(152) The fact that a product or service is provided free of charge does not prevent the offering of such a service from constituting an economic activity for the purposes of the competition rules of the Treaty.74 This is simply a factor to be taken into account in assessing dominance.

(153) The definition of the relevant market does not require the Commission to follow a rigid hierarchy of different sources of information or types of evidence. Rather, the Commission must make an overall assessment and can take account of a range of tools for the purposes of that assessment.75

5.2. The relevant product markets

(154) The Commission concludes that the relevant product markets for the purpose of this case are the market for general search services (section 5.2.1) and the market for comparison shopping services (section 5.2.2).

5.2.1. The market for general search services

(155) A number of different companies offer general search services. Some of them use their own search technology, such as Google, Microsoft (Bing)76 and Seznam.77 Others show results of a third party general search engine (often Google or Bing) with which they have an agreement. This is the case for instance, for Yahoo78 and America Online79, both of which return Bing generic search results, and Ask80, which returns Google generic search results.

(156) The Commission concludes that the provision of general search services constitutes a distinct product market. First, the provision of general search services constitutes an economic activity (section 5.2.1.1). Second, there is limited demand side substitutability (section 5.2.1.2) and limited supply side substitutability (section 5.2.1.3) between general search services and other online services. Fourth, this conclusion does not change if general search services on static devices versus mobile devices are considered (section 5.2.1.4).

5.2.1.1. The provision of general search services constitutes an economic activity

(157) For the reasons set out below, the provision of general search services constitutes an economic activity.

(158) First, even though users do not pay a monetary consideration for the use of general search services, they contribute to the monetisation of the service by providing data with each query. In most cases, a user entering a query enters into a contractual relationship with the operator of the general search service. For instance, Google’s Terms of Service provide: “By using our Services, you agree that Google can use such data in accordance with our privacy policies”.81 In accordance with its privacy policies, Google can store and re-use data relative to user queries.82 The terms and conditions of other providers of general search services contain similar provisions.83 The data which users agree to allow a general search engine to store and re-use is of value to the provider of the general search service as it is used to improve the relevance of the search service and to show more relevant advertising.84

(159) Second, offering a service free of charge can be an advantageous commercial strategy, in particular for two-sided platforms such as a general search engine platform that connect distinct but interdependent demands. In two-sided platforms, two distinct user groups interact. At least for one of these users groups, the value obtained from the platform depends on the number of users of the other class. General search services and online search advertising constitute the two sides of a general search engine platform. The level of advertising revenue that a general search engine can obtain is related to the number of users of its general search service: the higher the number of users of a general search service, the more the online search advertising side of the platform will appeal to advertisers.85

(160) Third, even though general search services do not compete on price, there are other parameters of competition between general search services.86 These include the relevance of results, the speed with which results are provided87, the attractiveness of the user interface88 and the depth of indexing of the web.89

5.2.1.2. Limited demand side substitutability with other online services

(161) General search services are not the only means by which users can explore the web. Alternative ways of discovering content include content sites, specialised search services and social networks.

(162) For the reasons set out below, there is, however, limited demand side substitutability between general search services and other online services.

5.2.1.2.1. General search services versus content sites

(163) There is limited substitutability between general search services and content sites.

(164) First, the two types of services serve a different purpose. On the one hand, a general search service primarily seeks to guide users to other sites. As Google indicates on its website: “[O]ur goal is to have people leave our website as quickly as possible”.90 On the other hand, while content sites may contain references to other sites, their primary purpose is to offer directly the information, products or services users are looking for. Well-known examples of content sites include Wikipedia, IMDb,91 and websites of newspapers and magazines such as The New York Times or Nature.92

(165) Second, content sites that offer sophisticated content search functionality on their websites93 are not substitutable for general search services. Such content search functionality remains limited to their own content or content from partners and does not allow users to search for all content over the internet, let alone all information on the web.

5.2.1.2.2. General search services versus specialised search services

(166) There is also limited substitutability between general search services and specialised search services.

(167) First, the nature of specialised search services and general search services is different. Specialised search services do not aim to provide all possible relevant results for queries; instead, they focus on providing specific information or purchasing options in their respective fields of specialisation. A specialised search service will also often cover a content category which is monetisable.94 By contrast, general search services search the entire internet and therefore generally return different, more wide-ranging results. Their services are not limited beforehand to one of several particular content categories.95

(168) Second, there are a number of differences in the technical features of specialised and general search services. In the first place, specialised search services and general search services often rely on different sources of data: the main input for general search services originates from an automated process called “web crawling”96, whereas many specialised search services rely on user input or information supplied by third parties.97 In the second place, specialised search services are usually monetised in a different way; in addition to relying on online search advertising, they generate revenue from, for instance, paid inclusion, service fees or commissions (pay-per-acquisition fees).98

(169) Third, the facts observed in the market, the history of the development of the products concerned and Google’s commercial practice further support the conclusion that specialised search services and general search services are different.

(170) In the first place, a wide variety of specialised search services have been offered on a standalone basis for several years. Examples include services specialised in search for products such as Shopzilla, LeGuide, Idealo, Beslist, Kelkoo and Twenga, in search for local businesses such as Yelp, in search for flights such as Kayak and EasyVoyage, and in search for financial services such as MoneySupermarket or confused.com.99 None of these companies offers a general search service.

(171) In the second place, Google offers and describes its specialised search services as a service distinct from its general search service. Google has a help page on its website which purports to list its different products and services. The page comprises a list of Google products and services. It distinguishes between, on the one hand, “Web Search - Search billions of web pages”, with a link to Google's general search service, and, on the other hand “Specialized Search”, which comprises several different services, including for instance “Google Shopping - Search for stuff to buy”.100

(172) Regarding specifically Google’s comparison shopping service, Google offers that service as a separate standalone service, and describes its functionality and purpose differently to how it describes its general search service. For example, Google Shopping UK, Google’s UK comparison shopping service, is described within Google UK’s general search results pages following a query for “Google Shopping” as “Google's UK price comparison service, with searches by keyword, which can then be broken down by category and ordered by price”. There is also a dedicated information page about Google Shopping, entitled “About Google Shopping”. It describes Google Shopping as a distinct “product discovery experience”: “Google Shopping is a new product discovery experience. The goal is to make it easy for users to research purchases, find information about different products, their features and prices, and then connect with merchants to make their purchase”.101 The page then elaborates on the many search tools that are specific to Google Shopping: “When you do a search within Google Shopping you'll see a variety of filters (like price, size, technical specifications, etc.) on the left side of the page that can help you quickly narrow down to the right product. You can also choose to display items in either a list or grid view by selecting one of these options in the top right hand corner above the results. When viewing certain apparel product detail pages (like dresses, coats and shoes), you'll also see items that are “visually similar” to the item you've selected. These are just a few of the many tools within Google Shopping and we look forward to providing more in the future”.102 By contrast, Google’s general search service is described within Google UK’s general search results pages following a query for “Google” in a more general manner: “The local version of this pre-eminent search engine, offering UK-specific pages as well as world results”.

(173) In the third place, reports of specialised market observers such as Nielsen and comScore distinguish between general search services and other search services.103

(174) Fourth, contrary to what Google claims,104 even though search results provided by a general search service may sometimes overlap with the results provided by a specialised search service, the two types of search services act as complements rather than substitutes.105

(175) In the first place, a general search service is the only online search service on which users can seek potential relevant results from all categories at the same time.

(176) In the second place, specialised search services offer certain search functionalities that do not exist, or not to the same extent, on general search services. For instance, on search services specialised in travel, users may look for hotels with a certain number of stars, or within a certain range of a city, or they may read user reviews of these hotels. These functionalities are unavailable to the same extent on a general search service for the same queries.

(177) In the third place, a substantial number of users reach to specialised search services only after having first entered a query in a general search service.106

5.2.1.2.3. General search services versus social networking sites

(178) There is also limited substitutability between general search services and social networking sites.

(179) First, general search services and social networking sites perform different functions. While general search services help users to find content they are looking for, social networks lead users to content they might be interested in by offering a means for users to connect and interact with people who, for instance, share interests or activities.

(180) Second, while certain social networks offer a general search function on their websites, so that users do not need to leave the sites to perform a general search, none of these sites uses its own general search technology. Instead, they rely on existing third party search services to power these searches. For example, Facebook previously relied on Microsoft’s Bing to provide search results.

(181) Third, the volume of general searches performed on social networks represents only a small share of the total volume of general searches. For example, in 2011, the number of general searches performed via Facebook in Europe107 was equivalent to only 3.2% of the number of general searches performed on Google Search, even though Facebook is by far the largest social network.108 […]109

(182) Fourth, […]110

(183) Fifth, regarding Google's claim that social networking sites are “increasingly active in product search”,111 this can indicate at most that comparison shopping services and social networking sites are substitutable, not that general search services and social networking sites are substitutable. Similarly, regarding Google's claim that “merchants and other business set up pages on social media sites with links to their websites and actively post on these sites”,112 this indicates at most that merchants and other businesses use social media sites as a tool to reach potential customers, not that these social media sites offer a comparison shopping service (as defined in section 5.2.2).

5.2.1.3. Limited supply side substitutability with other online services

(184) Supply side substitutability is also limited.

(185) In order to offer general search services, providers of other online services would need to make significant investments in terms of time and resources, particularly the initial costs associated with the development of algorithms and the costs of crawling and indexing the data. These barriers to entry are described in more detail in section 6.2.2.

5.2.1.4. General search services on static devices versus mobile devices

(186) For the reasons set out in recitals (187) to (189), general search services offered on static devices such as desktop and laptop PCs and on mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets belong to the same relevant product market.

(187) First, general search services are active on both types of devices. Although the user interface is different, the underlying technology is the same.113

(188) Second, general search services on static and mobile devices are offered by the same undertakings.

(189) Third, Google does not contest that general search services offered on static devices and on mobile devices are part of the same relevant product market.

(190) In any event, even if general search services on static devices were to constitute a distinct product market from general search services on mobile devices, this would not alter the Commission’s view as regards dominance (see section 6.2.6).

5.2.2. The market for comparison shopping services

(191) Comparison shopping services are specialised search services that: (i) allow users to search for products and compare their prices and characteristics across the offers of several different online retailers (also referred to as online merchants) and merchant platforms (also referred to as online marketplaces);115 and (ii) provide links that lead (directly or via one or more successive intermediary pages) to the websites of such online retailers or merchant platforms.116

(192) The Commission concludes that the provision of comparison shopping services constitutes a distinct relevant product market. This is because comparison shopping services are not interchangeable with the services offered by: (i) search services specialised in different subject matters (such as flights, hotels, restaurants, or news); (ii) online search advertising platforms; (iii) online retailers; (iv) merchant platforms; and (v) offline comparison shopping tools.

5.2.2.1.Comparison shopping services versus other specialised search services

(193) There is limited substitutability between comparison shopping services and other specialised search services.

(194) From the demand side perspective, each type of service focuses on providing specific information from different sources in its respective field of specialisation.117 Thus, comparison shopping services provide users that are looking for information on a product with a selection of existing commercial offers available on the internet for that product, as well as tools to sort and compare such offers based on various criteria.118 From the perspective of those users, such a service is not substitutable with that offered by search services specialised in different subject matters such as flights,119 hotels, locals (such as restaurants),120 and news.

(195) From the supply side perspective, each specialised search service selects and ranks results through specific criteria that rely on dedicated signals and formulas designed to determine the relevance of a particular information type (e.g. price, product information, merchant rating, product popularity, stock level for comparison shopping services; freshness for news aggregators; proximity to the user for specialised search services focused e.g. on restaurants).121 Moreover, specialised search services mostly select content from a pool of relevant suppliers with whom they have contractual relationships and those suppliers must provide input to databases and other data infrastructure operated by specialised search service providers.122 Each specialised search service therefore needs to develop and maintain a dedicated data infrastructure and structured relationships with relevant suppliers. Comparison shopping services typically employ a commercial workforce whose role is to enter into agreements with online retailers, pursuant to which these retailers send them feeds of their commercial offers. These services are only partially automated and involve commercial relationships with online retailers.123 Likewise, flight search services use proprietary databases of content that are usually updated in real-time to ensure that they provide the most current possible information and have contractual arrangements with the booking websites, which remunerate them either by paying a commission per flight ticket booked or on a cost-per-click basis.124 From the supply side perspective, substitutability is therefore also limited because providers of other specialised search services are not in a position to start providing comparison shopping services in the short term and without incurring significant additional costs.

5.2.2.2. Comparison shopping services versus online search advertising platforms

(196) There is also limited substitutability between comparison shopping services and online search advertising platforms.

(197) From the demand side perspective, while online retailers generally promote their offers through both comparison shopping services and online search advertising platforms, the latter do not provide services that are interchangeable from the perspectives of users and online retailers (and other advertisers).

(198) First, users perceive comparison shopping services as a service to them and navigate

– either directly (albeit to a limited extent) or (mostly) through a general search service (see section 7.2.4.1) – to a comparison shopping website (including Google Shopping) to search for a product and receive specialised search results. By contrast, users do not perceive online search advertising as a service to them and do not enter a query in a general search engine specifically in order to receive search advertising results. Indeed, Google does not offer a standalone service which users can navigate directly to in order to receive search advertising. Online search advertising is therefore not a service that users seek, but rather a compensation for the free service offered by general search engines (similar to the advertising on free-to-air TV).

(199) Second, comparison shopping services and online search advertising platforms are also complementary and not substitutable from the perspective of online retailers and other advertisers.

(200) In the first place, only specific subsets of advertisers (i.e. online retailers and merchant platforms) can bid to be listed in comparison shopping services whereas any advertiser can bid to be listed in online search advertising results.125

(201) In the second place, participation in comparison shopping services involves different conditions than in online search advertising results, including the provision to comparison shopping services of structured data in the form of feeds. For instance, online retailers and merchant platforms wishing to be listed in Google Shopping need to give Google dynamic access to structured information on the products that can be purchased on their websites, including dynamically adjusted information on prices, product descriptions and the number of items available in their stock (see also recital (432)).126

(202) In the third place, comparison shopping services display their results in richer formats than online search advertising results.127

(203) In the fourth place, the results of comparison shopping services are ranked based on different algorithms that take into account different parameters, tailored to the relevant specialised search category (see also recital (429)).128

(204) In the fifth place, unlike for online search advertising platforms, in order to appear in comparison shopping services such as Google Shopping, third party websites bid on products and not on keywords (see also recital (426)).129

(205) In the sixth place, when Google’s own comparison shopping service appears in Google's general search results page, AdWords results may also appear, thus showing that the two services are complementary from Google's perspective.

(206) From the supply side perspective, the functionalities and infrastructures required for the provision of comparison shopping services (see recital (195)) are different from those required for the provision of online search advertising. In particular, the provision of online search advertising services requires a company to invest in the development of a general search engine with a technology allowing users to search for keywords that can be matched with online search advertisements, as well as in a search advertisement technology to match keywords entered by users in their queries with relevant online search advertisements. According to Google, this is “[t]he most significant task that [a company] wishing to provide a search advertising solution might consider undertaking […]”.130

5.2.2.3. Comparison shopping services versus online retailers

(207) There is also limited substitutability between comparison shopping services and online retailers.

(208) From the demand side perspective, comparison shopping search services serve a different purpose than online retailers.

(209) On the one hand, comparison shopping services act as intermediaries between users and online retailers. They allow users to compare offers from different online retailers in order to find the most attractive offer. They also do not offer users the possibility to purchase a product directly on their websites but rather seek to refer users to third-party websites where they can buy the relevant product.131 Indeed, far from being competitors, comparison shopping services consider online retailers as business partners or customers, with which they enter into contractual relationships.132

(210) On the other hand, online retailers do not allow on their websites the possibility to compare their own offers with the offers for the same or similar products on the websites of other online retailers.133 Online retailers also do not seek to refer users to third-party websites; rather, they want users to buy their products without leaving their own websites; accordingly, they also offer after-sale support, including product return functionality.

(211) From the supply side perspective, the provision of comparison shopping services and online retailers requires different functionalities and infrastructures. Comparison shopping services have to retrieve the relevant information in response to each query by analysing the real-time feeds from as many online retailers as possible. By contrast, online retailers host and manage the inventory of their selected manufacturers and provide “check-out” and payment functionalities.

(212) The limited demand side and supply side substitutability between comparison shopping services and online retailers is not called into question by Google's claims that (i) online retailers also offer product search functionalities on their websites; and (ii) many users navigate directly to the websites of online retailers to find products, thereby bypassing comparison shopping services.134

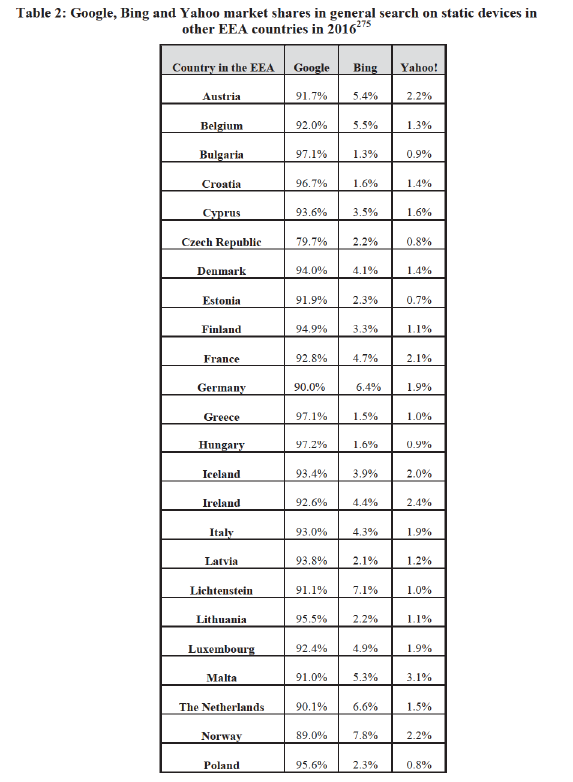

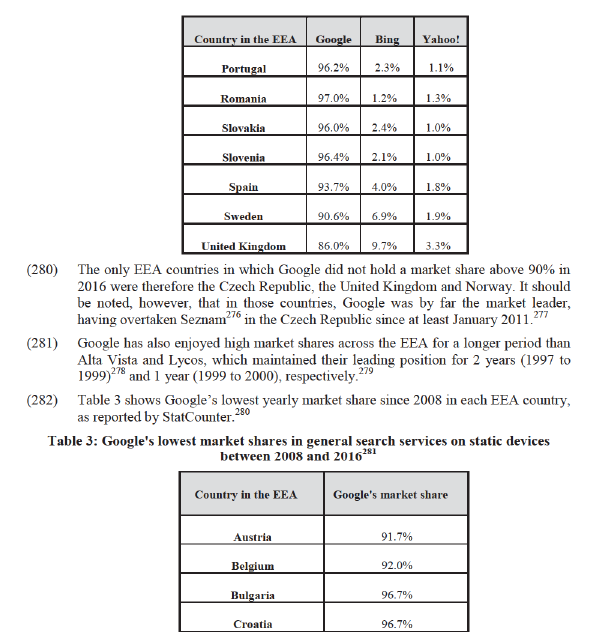

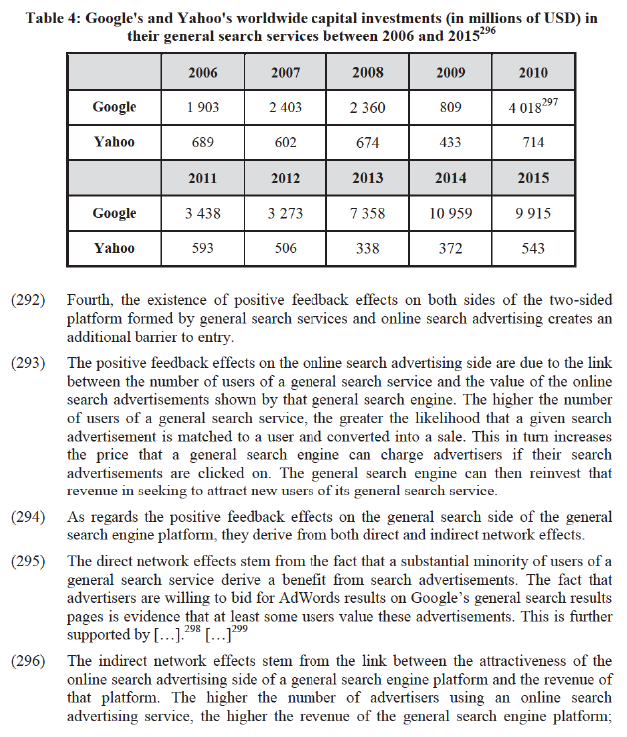

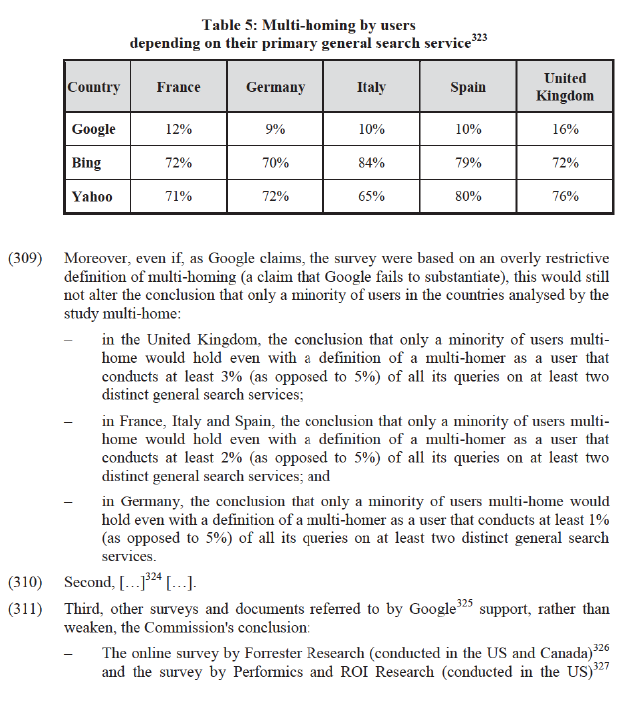

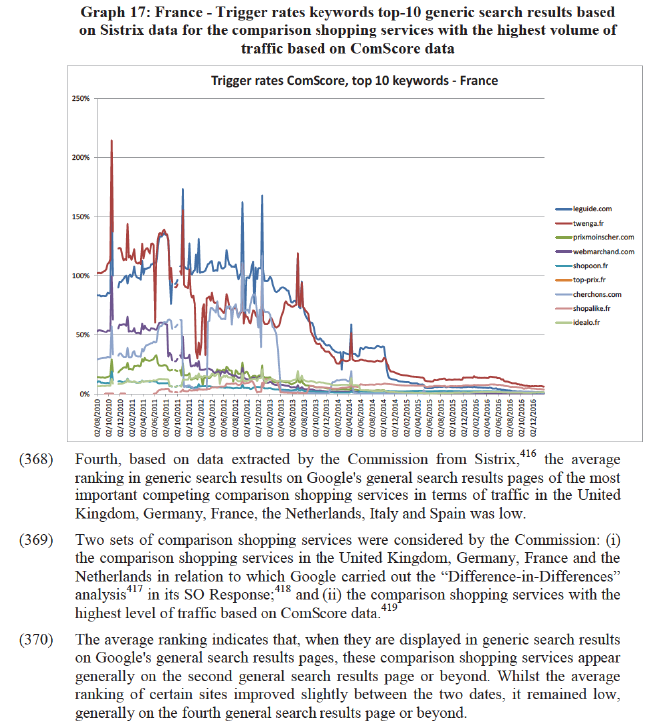

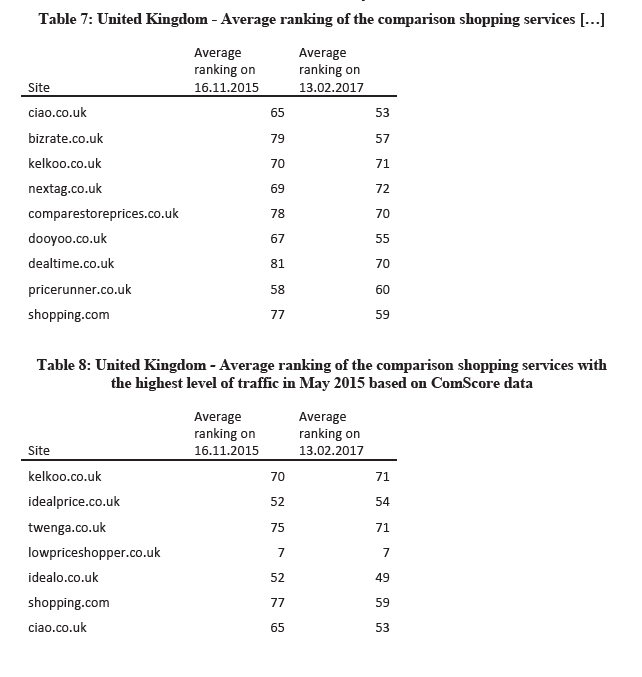

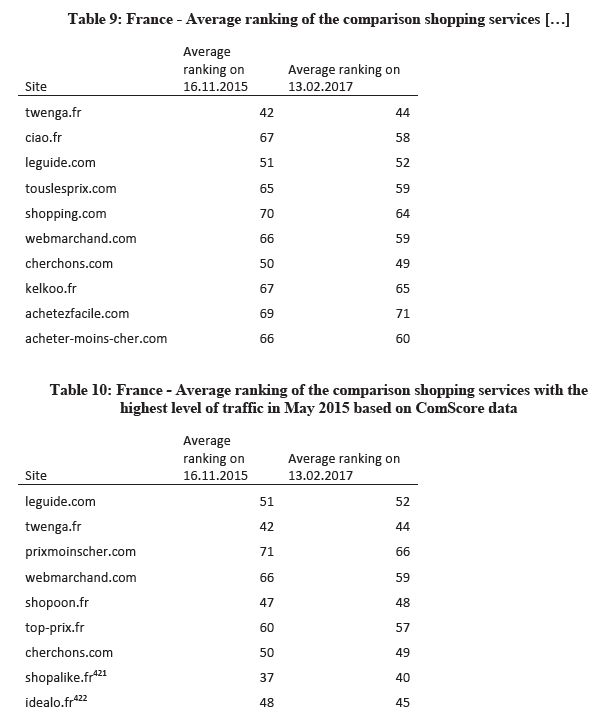

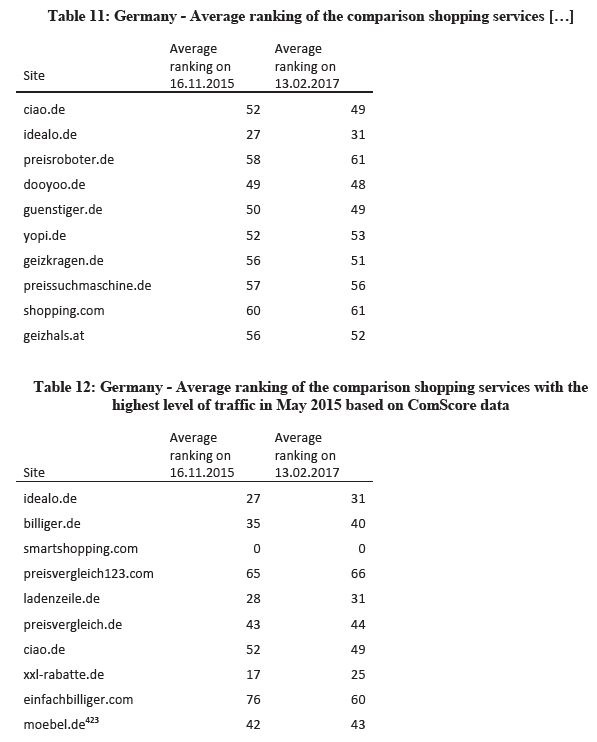

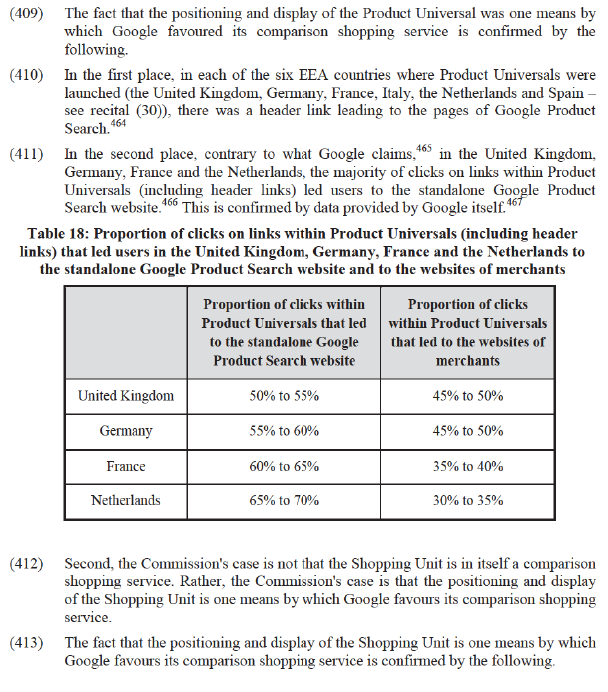

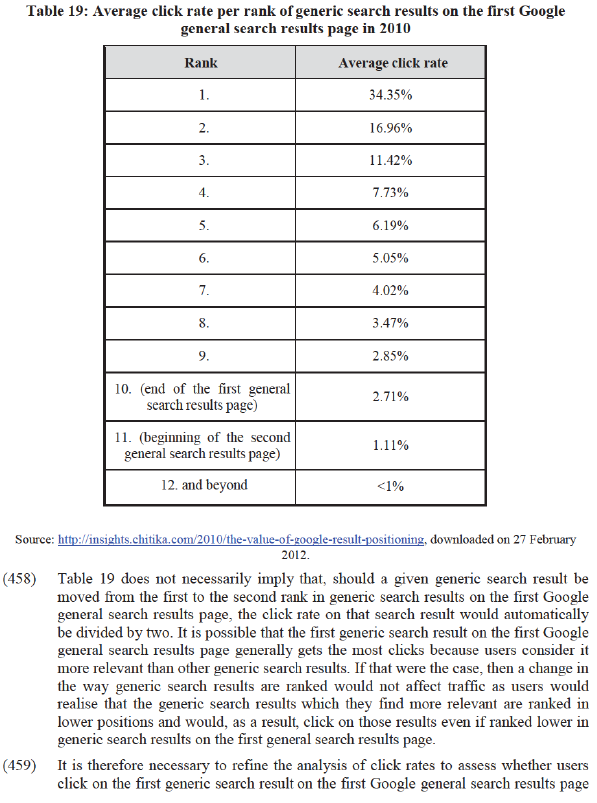

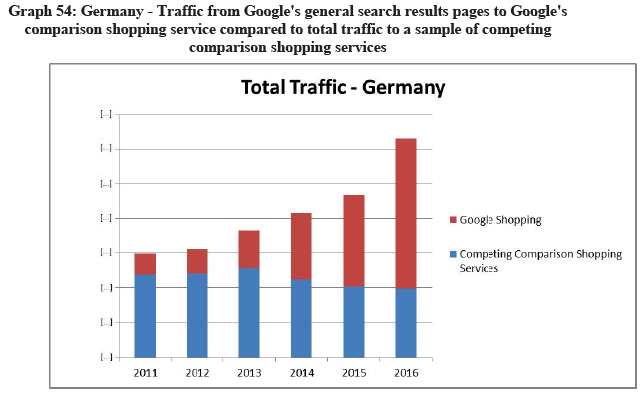

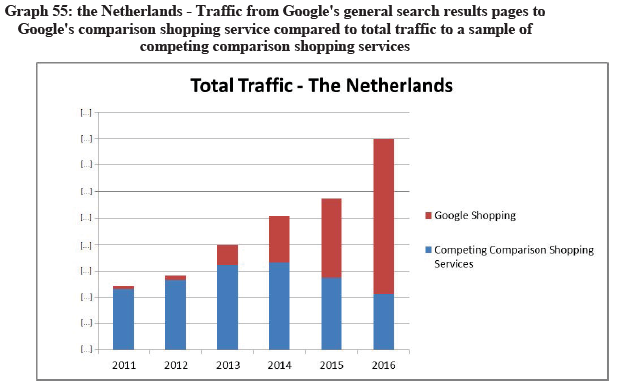

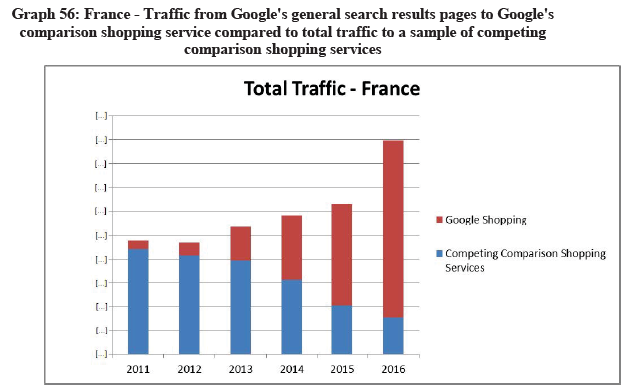

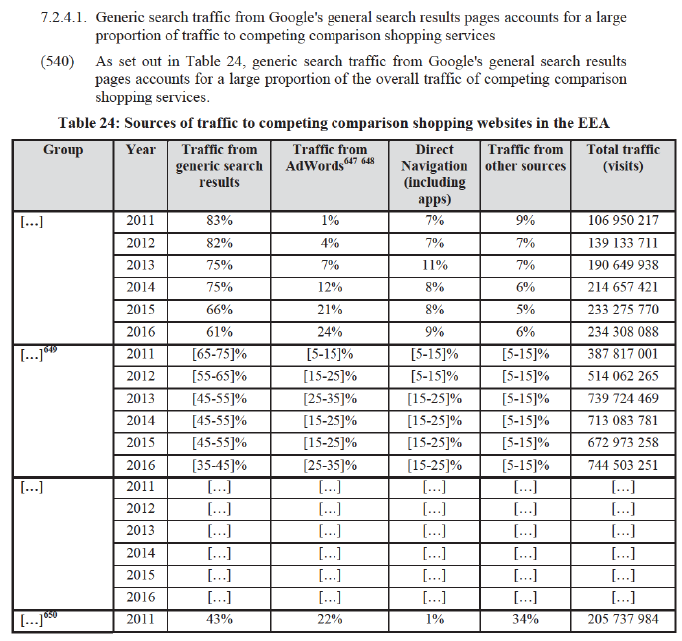

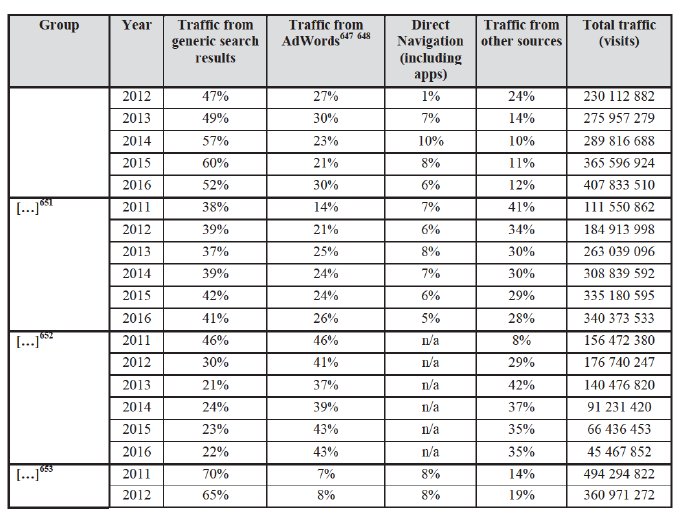

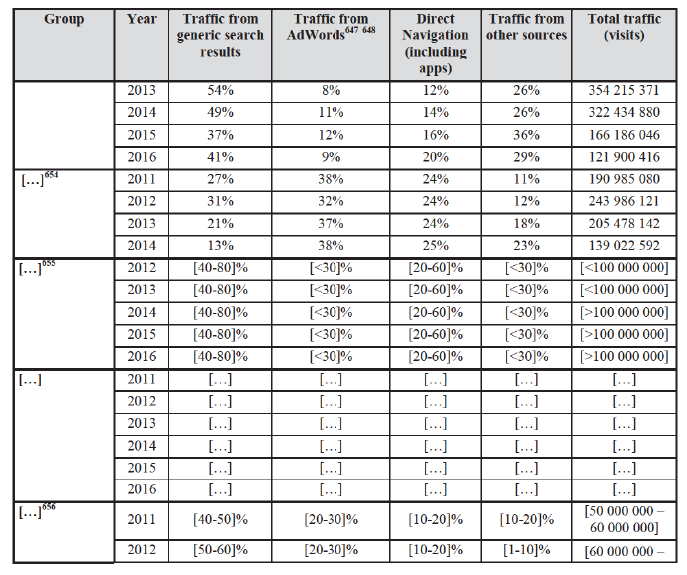

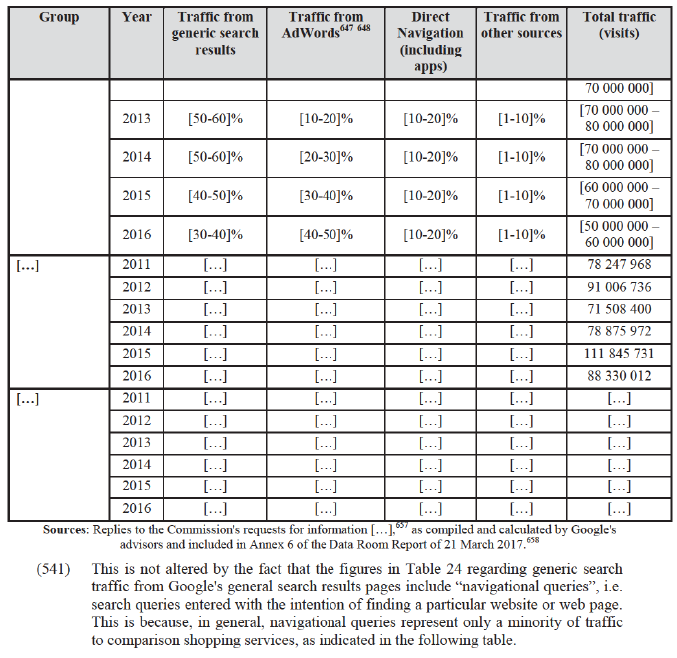

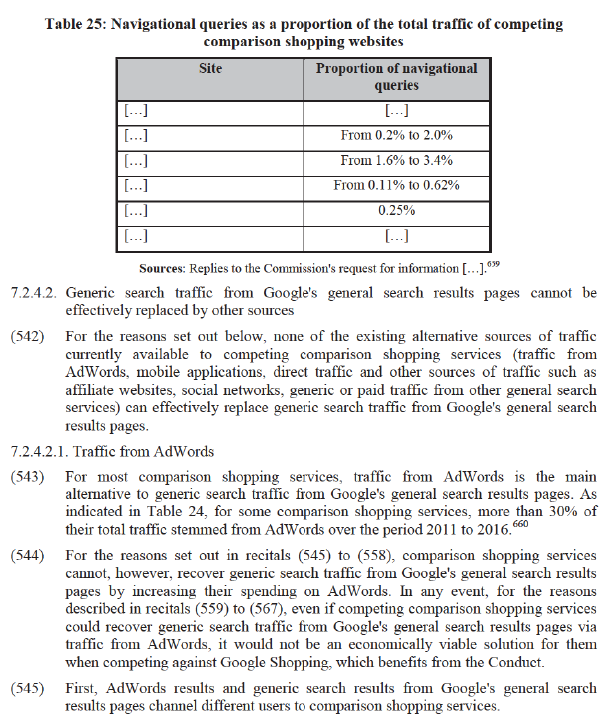

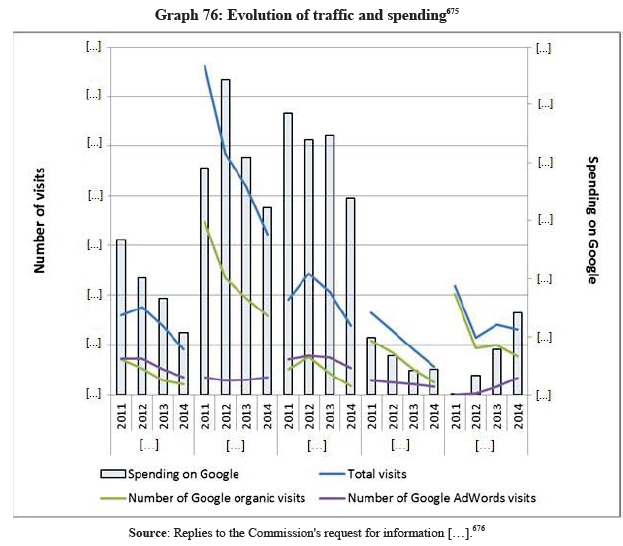

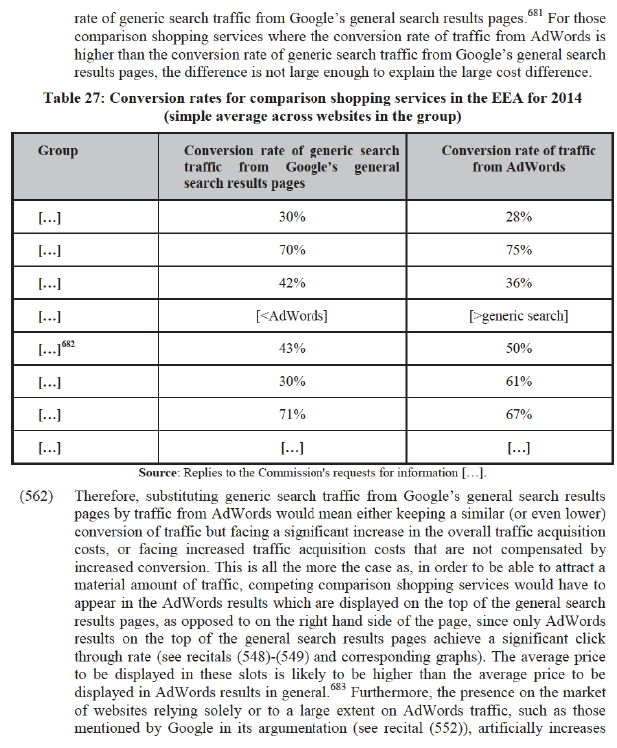

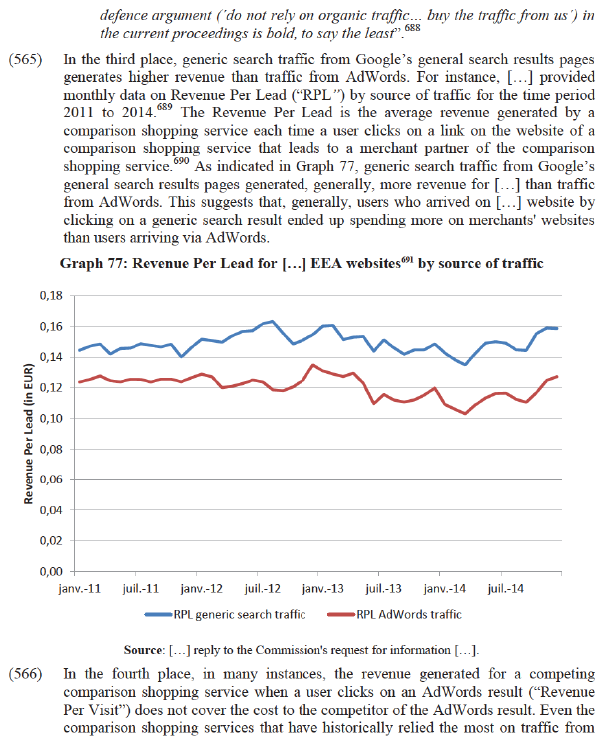

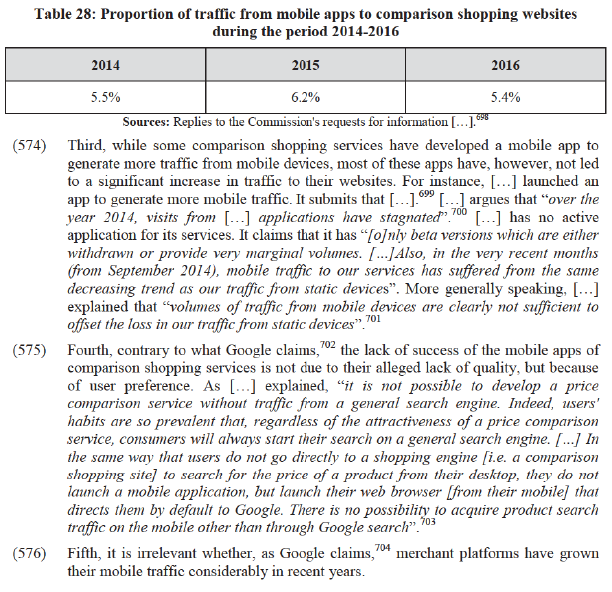

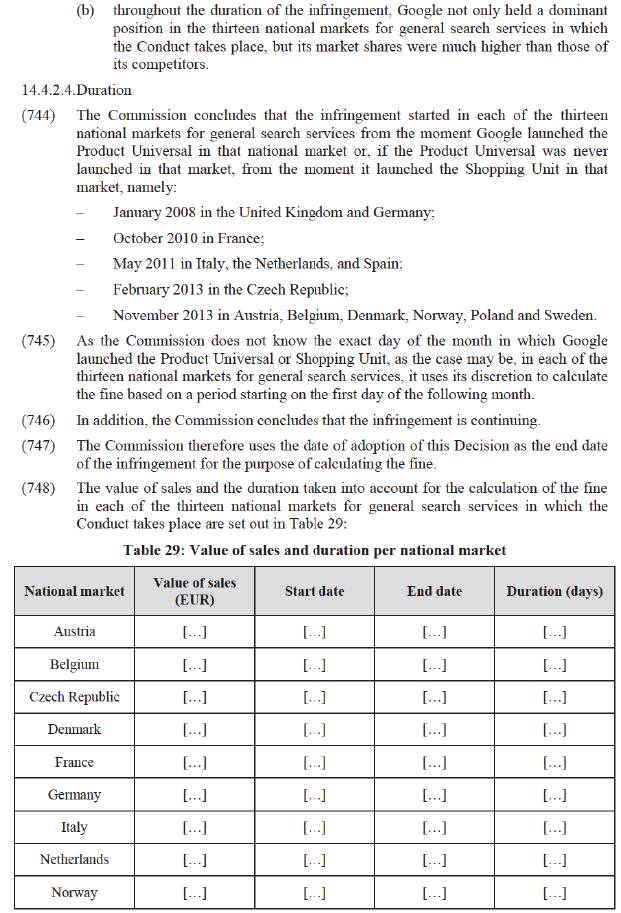

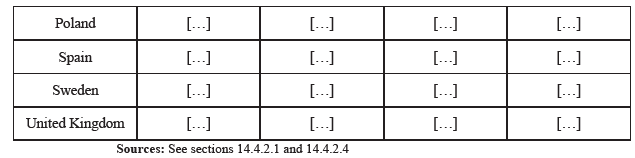

(213) First, the search functionality offered by online retailers is limited to products on their own website(s) and does not offer the possibility to compare the offers on their website with the offers for the same or similar products on the websites of other online retailers.