Commission, July 18, 2018, No 40099

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

Google Android

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,1 Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty,2 and in particular Articles 7, 23(2) and 24(1) thereof,

Having regard to the Commission decisions of 15 April 2015 and 20 April 2016 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given the undertaking concerned the opportunity to make known its views on the objections raised by the Commission pursuant to Article 27(1) of Regulation No 1/2003 and Article 12 of Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 of 7 April 2004 relating to the conduct of proceedings by the Commission pursuant to Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty,3

After consulting the Advisory Committee on Restrictive Practices and Dominant Positions, Having regard to the final report of the hearing officer in this case,

Whereas:

1. INTRODUCTION

(1) This Decision is addressed to Google LLC (formerly Google Inc.) ("Google") and to Alphabet Inc. ("Alphabet").

(2) This Decision establishes that conduct by Google with regard to certain conditions in agreements associated with the use of Google's smart mobile operating system, Android, and certain proprietary mobile applications ("apps") and services constitutes a single and continuous infringement of Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ("TFEU") and Article 54 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area ("EEA Agreement").

(3) This Decision also establishes that Google's conduct constitutes four separate infringements of Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement, each of which is also part of the single and continuous infringement referred to in recital (2).

(4) Google is or has been:

(1) tying the Google Search app with its smart mobile app store, the Play Store;

(2) tying its mobile web browser, Google Chrome, with the Play Store and the Google Search app;

(3) making the licensing of the Play Store and the Google Search app conditional on agreements that contain anti-fragmentation obligations, preventing hardware manufacturers from: (i) selling devices based on modified versions of Android ("Android forks"); (ii) taking actions that may cause or result in the fragmentation of Android; and (iii) distributing a software development kit ("SDK") derived from Android; and

(4) granting revenue share payments to original equipment manufacturers ("OEMs") and mobile network operators ("MNOs") on condition that they pre- install no competing general search service on any device within an agreed portfolio.

(5) This Decision is structured as follows:

(1) Section 2 deals with the undertaking concerned by the Decision;

(2) Section 3 outlines the procedure leading to the adoption of this Decision;

(3) Section 4 addresses Google's allegations that the Commission's investigation suffers from procedural errors;

(4) Section 5 describes the products concerned by this Decision;

(5) Section 6 describes Google's activities in the mobile industry;

(6) Section 7 describes the relevant product markets affected by this Decision;

(7) Section 8 describes the relevant geographic markets affected by this Decision;

(8) Section 9 concludes that Google has a dominant position in the worldwide market (excluding China) for the licensing of smart mobile OSs (Section 9.3), the worldwide market (excluding China) for Android app stores (Section 9.4) and in each national market for general search services in the EEA (Section 9.5);

(9) Section 10 outlines general principles on abuse of dominant position;

(10) Section 11 concludes that Google has abused its dominant position in the worldwide market (excluding China) for Android app stores by tying the Google Search app with its smart mobile app store, the Play Store, and by tying its mobile web browser, Google Chrome, with the Play Store and the Google Search app;

(11) Section 12 concludes that Google has abused its dominant position in the worldwide market (excluding China) for Android app stores and the national markets for general search services by making the licensing of the Play Store and the Google Search app conditional on the anti-fragmentation obligations in the anti-fragmentation agreements;

(12) Section 13 concludes that Google has abused its dominant position in the national markets for general search services by granting portfolio-based revenue share payments conditional on the pre-installation of no competing general search service;

(13) Section 14 concludes that the four infringements of Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement described in Sections 11 to 13 constitute a single and continuous infringement of Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement;

(14) Section 15 concludes that the Commission has jurisdiction to pursue this case;

(15) Section 16 concludes that Google's conduct has an effect on trade between Member States;

(16) Section 17 describes the addressees of this Decision;

(17) Section 18 outlines the remedies imposed by this Decision;

(18) Section 19 describes the periodic penalty payments necessary to compel Google and Alphabet to bring effectively to an end the separate infringements of Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement described in Sections 11 to 13 and the single and continuous infringement of Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement described in Section 14, if they have not already done so;

(19) Section 20 sets out the method for calculating the fine and the amount of the fine imposed; and

(20) Section 21 presents the Commission's conclusions.

2. UNDERTAKING CONCERNED

(6) Google is a multinational technology company specialising in Internet-related services and products that include online advertising technologies, search, cloud computing, software and hardware. It offers various services in the territories of all the Contracting Parties to the EEA Agreement. Google is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Alphabet.

(7) In August 2015, Google announced its intention to create a new holding company, Alphabet. The reorganisation was completed on 2 October 2015. Consequently, Google became a subsidiary of Alphabet on 2 October 2015.

(8) On 30 September 2017, Google converted from an incorporated entity (Google Inc.) to a limited liability company (Google LLC). In addition, a new holding company (XXVI Holdings Inc.) is now the sole shareholder of Google. XXVI Holdings Inc. is itself a wholly owned subsidiary of Alphabet.4

(9) According to the consolidated financial statements of Alphabet,5 its turnover for the fiscal year running from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2017 was USD 110 855 million (approximately EUR 98 127 million).6

3. PROCEDURE

(10) On 25 March 2013, FairSearch lodged a complaint with the Commission against Google. On 13 June 2013, the Commission sent Google a non-confidential version of that complaint. On 23 August 2013, Google provided comments on the same complaint. On 5 December 2014, the Commission sent FairSearch a non-confidential version of Google's comments. On 7 February 2015, FairSearch provided observations on Google's comments.

(11) Between 12 June 2013 and 11 March 2016, the Commission sent requests for information pursuant to Articles 18(2) and 18(3) of Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 ("Regulation (EC) No 1/2003") to Google, its customers, competitors and other parties active in the smart mobile environment.

(12) On 16 June 2014, Aptoide S.A. ("Aptoide") lodged a complaint with the Commission against Google. On 27 June 2014, the Commission sent Google a non-confidential version of that complaint. On 8 August 2014, Google provided comments on the same complaint. On 5 December 2014, the Commission sent Aptoide a non- confidential version of Google's comments. On 30 January 2015, Aptoide provided observations on Google's comments.

(13) On 15 April 2015, the Commission initiated proceedings against Google pursuant to Article 2(1) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 ("Regulation (EC) No 773/2004") in relation to a number of Google's practices.

(14) Also on 15 April 2015, Yandex N.V. ("Yandex") lodged a complaint with the Commission against Google. On 6 May 2015, the Commission sent Google a non- confidential version of that complaint. On 7 August 2015, Google provided comments on the same complaint.

(15) On 1 June 2015, Disconnect Inc. ("Disconnect") lodged a complaint with the Commission against Google. On 22 June 2015, the Commission sent Google a non- confidential version of that complaint. On 7 August 2015, Google provided comments on the same complaint.

(16) On 9 June 2015, 8 July 2015, 30 September 2015 and 14 March 2016, the Commission met with Google. The Commission also held a number of meetings with third parties during the proceedings.

(17) On 19 April 2016, the Commission held a state-of-play meeting with Google.

(18) On 20 April 2016, the Commission initiated proceedings against Alphabet pursuant to Article 2(1) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 and adopted a Statement of Objections addressed to Google and Alphabet.7

(19) On 22 April 2016, after having informed Google, the Commission transferred certain documents in the case file in Case AT.39740 – Google Search to the case file in Case AT.40099.

(20) Following the adoption of the Statement of Objections on 20 April 2016, the Commission granted Google access to its file. To this end, on 3 May 2016, the Commission provided Google with access to part of the case file. Access to the remaining part of the file was granted to Google's external legal and economic advisers subject to twenty-six Non-Disclosure Agreements ("NDAs"), under which such advisers undertook, with Google's agreement, not to reveal to Google any information relating to third parties derived from this part of the file, without the Commission's prior consent. In this context, documents were disclosed to Google's external legal and economic advisors under confidentiality ring arrangements, or access was provided pursuant to five data room procedures, under which Google's external legal and economic advisors accessed the information relating to third parties only at the Commission premises.

(21) Between 21 September 2016 and 2 October 2017, the Commission sent a non- confidential version of the Statement of Objections to seventeen complainants and interested third parties.

(22) Between 21 October 2016 and 16 October 2017, the Commission received comments on the Statements of Objections from eleven complainants and interested third parties.

(23) On 10 November 2016, Google submitted a provisional response to the Statement of Objections. On 23 December 2016 Google submitted a final version of its response to the Statement of Objections (the "Response to the Statement of Objections").

(24) Google did not request the opportunity to develop its arguments at an oral hearing.

(25) On 25 January 2017, Google submitted a letter concerning a decision of the Canadian Competition Bureau and provided a copy of an industry report on trends in the mobile apps sector.

(26) On 6 March 2017, Open Internet Project ("OIP") lodged a complaint against Google. On 15 March 2017, the Commission sent Google a non-confidential version of the complaint. On 14 April 2017, Google provided comments on the complaint.

(27) Between 8 March 2017 and 10 April 2017, the Commission sent further requests for information pursuant to Articles 18(2) and 18(3) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 to Google, its customers, competitors and other parties active in the smart mobile environment, such as app developers and providers of web-based services.

(28) On 31 August 2017, the Commission sent Google a letter (the "First Letter of Facts") informing it about pre-existing evidence to which Google already had access but which was not expressly relied upon in the Statement of Objections but which, on further analysis of the Commission's file, could be relevant to support the preliminary conclusions reached in the Statement of Objections. The Commission also informed Google in the First Letter of Facts about additional evidence obtained by the Commission after the adoption of the Statement of Objections.

(29) Following the adoption of the First Letter of Facts, the Commission granted access to the file to Google. To this end, on 1 September 2017, the Commission provided Google with access to part of the documents added to the case file since 3 May 2016 and access to the remaining part of the documents added to the case file since 3 May 2016 was granted subject to four additional NDAs and two further data room procedures.

(30) On 15 September 2017 Google submitted a letter requesting full records of the Commission's meetings with third parties relating to the investigation.

(31) On 23 October 2017, Google submitted a response to the First Letter of Facts (the "Response to the First Letter of Facts").

(32) On 1 December 2017, Google submitted a letter and term sheet describing changes that it would be ready to implement in the framework of commitments pursuant to Article 9 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003. After assessing Google's letter and term sheet, the Commission informed Google on 12 February 2018 that it intended to continue the procedure under Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003.

(33) On 28 February 2018, the Commission provided Google with minutes of the meetings and calls that the Commission had with third parties concerning the subject matter of the investigation. The Commission also provided Google with new documents that had been added to the Commission file since the issuing of the First Letter of Facts.

(34) On 14 March 2018, Google submitted a letter concerning factual and legal developments since the Statement of Objections. In addition, on 14 March 2018 Google sent a letter requesting that Commission investigate whether FairSearch still has a legitimate interest in Case AT.40099 with a view to: (i) rejecting its complaint; and (ii) discounting submissions made by FairSearch since at least November 2015.

(35) On 27 March 2018, the Commission met with Google.

(36) On 5 April 2018, the Commission sent a request for information pursuant to Article 18(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 to Google, concerning Google's corporate structure, value of sales and turnover during the previous full business year.

(37) On 11 April 2018, the Commission sent Google a letter (the "Second Letter of Facts") informing it about pre-existing evidence to which Google already had access but which was not expressly relied upon in the Statement of Objections or First Letter of Facts but which, on further analysis of the Commission's file, could be relevant to support the preliminary conclusions reached in the Statement of Objections. The Commission also informed Google in the Second Letter of Facts about additional evidence obtained by the Commission after the adoption of the First Letter of Facts.

(38) Following the adoption of the Second Letter of Facts, the Commission granted access to the file to Google. To this end, on 12 April 2018, the Commission provided Google with access to the non-confidential documents in the file added since 1 September 2017. Access to one document was provided subject to an existing NDA.

(39) On 30 April 2018, Google submitted a response to the Commission's request for information.

(40) On 7 May 2018, Google submitted a response to the Second Letter of Facts (the "Response to the Second Letter of Facts"). On the same day, Google also requested the opportunity to develop its arguments at an oral hearing.

(41) On 18 May 2018 the Commission refused Google's request for an oral hearing.

(42) On 11 June 2018, Google submitted a letter entitled "the Commission has failed to assess Google's Android agreements in their relevant economic and legal context".

(43) On 20 June 2018, Google submitted a letter requesting that it be afforded at least 90 days to comply with any remedies that the Commission may impose.

(44) On 21 June 2018, at Google's request, the Commission provided Google with two letters received from third parties.

(45) On 27 June 2018, Google submitted its observations on these letters.

4. GOOGLE'S ALLEGATIONS THAT THE COMMISSION'S INVESTIGATION SUFFERS FROM PROCEDURAL ERRORS

(46) Google claims that the Commission's investigation suffers from a number of procedural errors.

(47) First, the Commission granted access to file in a fragmented, time-consuming and difficult manner that was completed one day before the deadline for the Response to the Statement of Objections. Moreover, the Commission failed to provide Google with direct access to 142 documents.

(48) Second, the Commission has breached Google's rights of defence by not providing it with adequate access to minutes of meeting with third parties.8

(49) Third, the Commission has failed to assess the evidence properly by: (i) relying on documents and data that contradict the Commission's findings, (ii) ignoring exculpatory material that has been added to the file, (iii) misrepresenting and mischaracterising the meaning of documents in the case file, (iv) quoting selectively from the documents, (v) relying on speculation and unsupported conjecture as evidence, and (vi) failing to investigate matters that are central to the Commission's case.9

(50) Fourth, the Commission should discount submissions made by FairSearch since at least November 2015 because they "were made on behalf of an entity whose members had no relevant knowledge of the matters at issue and were motivated solely by a common desire to harm Google".10

(51) For the reasons set out in recitals (52) to (61) the Commission's investigation does not suffer from any of the alleged procedural errors mentioned in recitals (47) to (50).

4.1. The Commission's alleged failure to grant access to the file in a timely and complete manner

(52) For the reasons set out in this Section, the Commission granted access to the file in a timely and complete manner.

(53) First, the Commission struck an appropriate balance between the proper exercise of Google's rights of defence and the right of information providers to protect their business secrets and other confidential information.11

(54) On the one hand, the Commission granted Google access to non-confidential versions of the documents in the Commission's file. The Commission also granted Google's advisors access to entirely unredacted or less redacted versions of documents in the case file subject to thirty NDAs by disclosing documents to Google's advisors subject to confidentiality ring arrangements or pursuant to seven data room procedures.12

(55) On the other hand, the 142 documents mentioned by Google to which the Commission granted Google's advisors access subject to NDAs, contained business secrets and other confidential information within the meaning of Article 339 of the Treaty, Article 27(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, and Articles 15(2) and 16(1) of Regulation (EC) No 773/2004. Access by Google's advisors was in this case a sufficient and proportionate means to ensure the respect of Google's rights of defence.

(56) Second, between 3 May and 26 August 2016, the Commission gave Google, directly or through its advisors, access to confidential or non-confidential versions of the documents on the file. Google therefore had a period of almost four months to prepare its Response to the Statement of Objections, which it submitted on 23 December 2016.

(57) Third, the period of approximately eight months that the Commission granted Google to prepare its Response to the Statement of Objections was, in light of the complexity of the case,13 sufficient to allow Google to exercise its rights of defence. In particular, Google gave a detailed exposition of its views on each essential allegation made by the Commission.14

(58) Fourth, the Commission's conclusion is not affected by Google's claim that the Commission provided it with less redacted non-confidential versions of certain documents between 26 August 2016 and 22 December 2016.

(59) In the first place, prior to 26 August 2016, the Commission had provided Google, directly or through its advisors, with access to confidential or non-confidential versions of all documents on the file. The additional information provided to Google between 26 August and 22 December 2016 was limited.

(60) In the second place, any delay in providing access to certain non-confidential versions of documents was taken into account when granting extensions of the time- limit for Google to respond to the Statement of Objections.

(61) In the third place, the fact that, following Google's requests, the Commission provided it on an ongoing basis with less redacted non-confidential versions of certain documents is not out of the ordinary in investigations in competition matters.15

4.2. The Commission's alleged failure to provide Google with adequate access to minutes of meetings with third parties

(62) For the reasons set out in this Section, the Commission provided Google with adequate access to minutes of meetings with third parties.

(63) First, on 28 February 2018 the Commission provided Google with minutes of the meetings and calls that the Commission had with third parties concerning the subject matter of the investigation. These minutes were obtained by agreement with the third parties concerned.

(64) Second, there are no other documents in the Commission's possession that contain any further account of the meetings concerned.

(65) Third, Google has not brought forward specific arguments as to how and why the alleged failure of the Commission to provide fuller meeting notes has impeded the effective exercise of its rights of defence.

4.3. The Commission's alleged failure to assess the evidence properly

(66) For the reasons set out in this Section, the Commission has properly assessed the evidence in this case.

(67) As a preliminary point, Google's claims are in effect a challenge to the merits of the Commission's assessment of its conduct and are therefore irrelevant to the question of whether the Commission's investigation suffers from a number of procedural errors.

(68) First, in relation to points (i) to (iv) of Google's claim outlined in recital (49), the fact that the Commission does not make use of all the information contained in a submission does not imply that the submission is, in its entirety, of weak probative value. This is because it is normal that some information is irrelevant or that certain information is supported more convincingly by other evidence.16

(69) Second, in relation to point (ii) of Google's claim outlined in recital (49), the Commission has not ignored exculpatory material that has been added to the file. Google has had the opportunity to draw the Commission's attention to allegedly exculpatory evidence in the file and to make arguments based on such allegedly exculpatory evidence.

(70) Third, in relation to points (i) to (v) of Google's claim outlined in recital (49), it is not necessary for every item of evidence adduced by the Commission to be sufficiently precise and consistent to establish every aspect of the separate infringements of Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement described in Sections 11 to 13 and the single and continuous infringement of Article 102 TFEU and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement described in Section 14. It is sufficient that the body of evidence relied on by the Commission, viewed as a whole, meets that requirement.17 In that regard, the Commission may take into account all types of evidence,18 including evidence submitted by market players, parties to the administrative procedure19 and non-technical evidence.20

(71) Fourth, in relation to point (vi) of Google's claim outlined in recital (49), the Commission is not required to reply to all the arguments of an undertaking under investigation or to carry out further investigations, where it considers that its investigation of a case is sufficient.21

4.4. The Commission's alleged obligation to discount FairSearch's submissions since at least November 2015

(72) The Commission considers that there are no grounds for discounting FairSearch's submissions since at least November 2015. This is because, irrespective of whether FairSearch still has an ongoing legitimate interest in Case AT.40099, the Commission is entitled to take into account all types of evidence in its investigations.22

5. PRODUCTS CONCERNED BY THIS DECISION

(73) This Decision concerns the following products:

(1) smart mobile devices;

(2) operating systems for smart mobile devices;

(3) apps;

(4) smart mobile app stores;

(5) application programming interfaces;

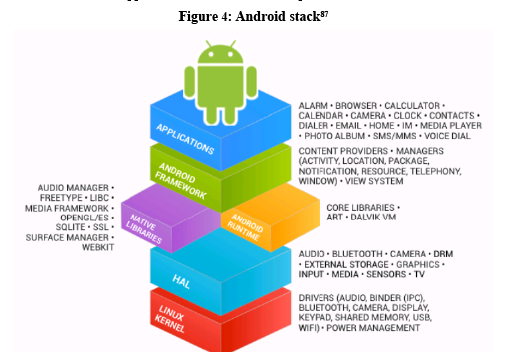

(6) general search services; and

(7) web browsers.

5.1. Smart mobile devices

(74) Smart mobile devices are mobile devices with advanced Internet browsing, multimedia and app capabilities. Smart mobile devices are available in a variety of designs, and with a range of different features and hardware components. There are, broadly speaking, two types of smart mobile devices: smartphones and tablets.23

(75) Smartphones are wireless telephones with advanced Internet browsing and app capabilities. Smartphones incorporate hardware and software features that enable them to fulfil many of the functions traditionally associated with state of the art computing.24 There is no industry standard definition of a smartphone, but rather a spectrum of functionalities.25 Smartphones vary in terms of size, weight, durability, screen size, audio quality, camera size/zoom, web speed, computer processing power, memory, ease-of-use, optical quality, casing quality/design, and additional multimedia offerings.26

(76) Tablets are mobile devices in the spectrum between a smartphone and a personal computer ("PC"). Tablets are generally operated using a touch screen. Tablets are based on similar hardware to advanced touch-screen based smartphones, and provide a rich multimedia experience along with many of the functions of a PC.27

(77) The distinction between smartphones and tablets is not necessarily clear-cut. Devices combining the characteristics of both smartphones and tablets have been launched. These devices have both full voice transmission capabilities and a relatively large screen size, and are commonly called "phablets".28

(78) Smart mobile devices are sold by OEMs either directly to users or to MNOs, who in turn sell them to users under their respective brands.

5.2. Operating systems for smart mobile devices

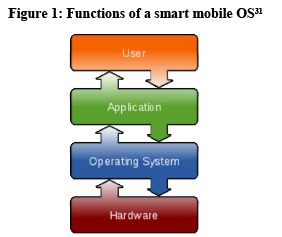

(79) Smart mobile devices need an operating system ("OS") to run on.29 OSs are system software products that control the basic functions of a computer and enable users to make use of such a computer and run software on it.30 OSs that are designed to support the functioning of smart mobile devices and the corresponding apps are hereinafter referred to as "smart mobile OSs".

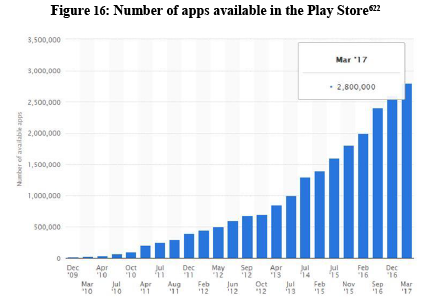

(80) Smart mobile OSs typically provide a graphical user interface ("GUI"), application programming interfaces ("APIs"), and other ancillary functions. These are required for the operation of a smart mobile device and enable new combinations of functions to offer richer usability and innovations.

(81) Apps written for a given smart mobile OS will typically run on a smart mobile device using the same OS, regardless of the manufacturer. Figure 1 shows the functions of the smart mobile OS.

(82) Smart mobile OSs combine the features of a PC OS with touchscreen, cellular, Bluetooth, WiFi, GPS mobile navigation, camera, video camera, speech recognition, voice recorder, music player, near field communication, personal digital assistant ("PDA") and other features. While certain features of a smart mobile device are not dependent upon a technical interface with the smart mobile OS, others require a more substantial technical interface with it. Moreover, certain characteristics such as speed and memory size are at least partially influenced by the quality of the smart mobile OS.32

(83) Smart mobile OSs are developed by vertically integrated OEMs such as Apple Inc. ("Apple") or BlackBerry Limited ("BlackBerry") for captive use in their own smart mobile devices ("non-licensable smart mobile OSs"), or by providers such as Google or Microsoft Corp. ("Microsoft"), which then license their smart mobile OS to OEMs ("licensable smart mobile OSs"). The licensing of a smart mobile OS therefore constitutes an economic activity upstream from the level of sales of smart mobile devices to users.

5.3. Apps

(84) Apps are types of software through which users can access World Wide Web ("web") content and services on their smart mobile devices. Apps can be "standalone" and serve offline tasks (such as games or photography) or incorporate some form of online service (such as geolocation or integration with social networks).33 Apps are optimised for the characteristics of smart mobile devices, as compared with PCs, such as reduced text input, limited screen size or convenience of touch-based interfaces.34

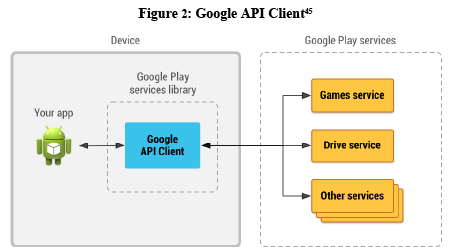

(85) Apps can principally be divided into native and non-native ones. Native apps are apps written in a specific programming language of a given device – for example Java for the Android OS.35 Non-native apps are developed for several smart mobile OSs using a cross-platform SDK.36

5.4. Smart mobile app stores

(86) The development of smart mobile devices has led to the emergence of a new type of software: digital distribution platforms, constituted by online services and related apps that are dedicated to enabling users to download, install and manage a wide range of diverse apps from a single point in the interface of the smartphone.37 These digital distribution platforms are called smart mobile app stores ("app stores").38

(87) The most widely used app stores are specific to a smart mobile OS ("Play Store" for Google Android,39 "App Store" for the OS of Apple, iOS, "Windows Mobile Store" for the OS of Microsoft, Windows Mobile,40 and "BlackBerry World" for the OS of BlackBerry, BlackBerry OS).41

(88) App stores are generally available to users for free. Users only pay to download certain apps or acquire paid content within apps ("in-app purchases"). Developers of revenue-generating apps pay an app store a fixed percentage of their app-related revenues when users pay for the download of apps or make in-app purchases.

5.5. Application programming interfaces (APIs)

(89) An API is a particular set of rules and specifications that a software program follows in order to access and make use of the services and resources provided by another software program or hardware that also implements that API.

(90) In essence, APIs allow software programs and hardware, or different software programs, to communicate with each other.

(91) In the smart mobile device environment, APIs are important as they allow app developers to integrate "cloud" web services directly in their apps. This allows app developers to offload computationally challenging or data intensive tasks to cloud computers,42 in order not to impact the storage, performance or battery of a smart mobile device.43 Due to the technical limitations of smart mobile devices compared to PCs, cloud services and related APIs have a particularly important role in the smart mobile environment.44

(92) Google offers APIs that allow app developers to integrate within their apps a number of Google's services. Figure 2 shows how the Google API Client provides an interface for connecting to any of the available Google services such as those related to online games ("Google Play Games") and cloud storage ("Google Drive").

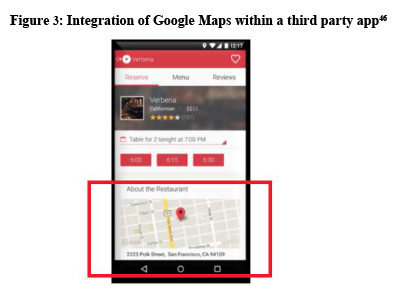

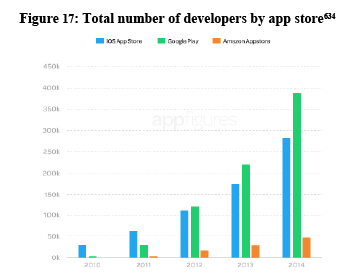

(93) Another example is the integration of Google's mapping, navigation and geolocation service ("Google Maps") within a third party app. This is shown in Figure 3.

5.6. General search services

(94) General search47 services allow users to search for information across the entire Internet. Alternative ways of discovering content include specialised search services, social networks and content sites.

(95) While the user interface of a general search service may vary depending on whether they are accessed via PCs or smart mobile devices, the underlying technology is essentially the same.

(96) General search services are generally provided on the basis of search engines. A search engine is a coordinated set of programmes that normally includes: (i) a spider (also called a "crawler" or a "bot") that goes to every page or representative pages on a web site that wants to be searchable and reads it; (ii) a programme that creates an index (sometimes called a "catalogue") from the pages that have been read; and (iii) a programme that allows users to enter a keyword or a string of keywords ("query"), compares it to the entries in the index, and returns the results which are relevant to the query.

(97) The latter programme is called a search algorithm, which contains processes and formulas that rely on unique signals or "clues" that make it possible to come up with results that are relevant to the query.48

(98) There are three main categories of search algorithms: general search algorithms, specialised search algorithms and search advertisement algorithms. General search algorithms run across all types of pages. Specialised search algorithms are specifically optimised for identifying relevant results for a particular type of information,49 such as news, local businesses or product information. Specialised search algorithms are used for specialised search services,50 which are different from general services for a variety of reasons beyond their nature and technical features.

(99) In addition to the general and specialised search algorithms, a general search service can run a third category of search advertisement algorithms that provides search advertisements matching a user's search query.

(100) A number of different companies offer general search services. Some of them use their own search engine, such as Google, Microsoft (Bing),51 Seznam.cz, a.s. ("Seznam")52 and Orange S.A. ("Orange").53 Others show results of a third party general search engine (often Google or Bing) with which they have an agreement. This is the case for example of Yahoo Inc. ("Yahoo"),54 AOL Inc. ("AOL")55 and InterActiveCorp ("Ask")56, which return results powered by other general search engines.

(101) General search services can be accessed on smart mobile devices via a number of different entry points. For instance, for Android, these include the following:

(1) search widget57 (or Quick Search Bar);

(2) search app;

(3) URL line (also called "Omnibox") in web browser;

(4) search bar in notification area;

(5) search bar on the lock screen;

(6) default home page of browser;

(7) hardware search button;

(8) soft search button;

(9) long-press of the home button;

(10) voice search; and

(11) search bookmark in browser.

5.7. Web browsers

(102) Web browsers are software used by users of client PCs, smart mobile devices and other devices to access and interact with web content hosted on servers that are connected to networks such as the Internet.

(103) Users can access web content through a web browser by typing the relevant Uniform Resource Locator ("URL") into the browser. Alternatively, they can search for specific content via an embedded general search service, either in the same box where the URL can be typed, or in a dedicated "search box".58

(104) In addition, web browsers typically offer a set of additional features. These include the following:

(1) proxy configuration59 (to specify how the web browser accesses web content);

(2) management of plug-ins to handle additional content types (such as Flash or Java programs);

(3) bookmarking (to keep track of useful web page addresses);

(4) HTML60 (Hypertext Markup Language) pre-processing (to filter out unwanted or dangerous content);

(5) cookie management (allowing users to keep control of small text files deposited by many web pages into web browsers in order to enable recognition of previous visitors);

(6) pop-up blocker (to manage web page window behaviour);

(7) tabbed browsing interface (to keep open several web pages at once);

(8) website certificate checker (to ascertain web page credentials and to protect against phishing);61

(9) offline cache (to keep a copy of accessed online content for later offline usage); and

(10) history (of visited locations on the web).

6. GOOGLE'S ACTIVITIES IN THE MOBILE INDUSTRY

6.1. Overview of Google's business activities

(105) Google's business model is based on the interaction between, on the one hand, online products and services it offers free of charge to users and, on the other hand, its online advertising services, from which it derives the majority of its revenues.62

(106) Google's flagship online service for users is its general search service ("Google Search"). When a user enters a query in Google Search, Google's general search results pages return different categories of search results, including generic search results63 and specialised search results.64 In addition, Google Search may return a third category of results, namely online search advertisements drawn from Google's auction-based online search advertising platform, AdWords.

(107) Google offers a number of other products and services free65 of charge to users. In addition to the smart mobile OS, Android, these include for example a web-based app store ("Play Store"), a web browser ("Google Chrome"), a web-based email account service ("Gmail"), a file storage and editing service offering a suite of office apps (Google Drive), an online mapping, navigation and geolocation service (Google Maps), an online video streaming service ("YouTube") and a social networking website ("Google Plus").

(108) A number of these products and services are also search-driven, such as YouTube and Maps, and thus are of importance for the machine learning aspects of Google's general search service. The latest iteration of Google's machine learning technology used in its search services is called "RankBrain".66 RankBrain uses mathematical processes and an advanced understanding of language semantics to gradually learn more about how and why people search and apply those conclusions to future search results.67 It has become an important signal contributing to the result of a general search query.68

(109) Google also collects data via its products and services, such as Chrome, Google Maps, YouTube and Gmail. This ensures that Google receives a steady stream of user information that it can feed back into its search and search advertising business.69

(110) For example, an Android user signed into a Google account and running Google's apps generates a stream of varied signalling information – ranging, for example, from where a user lives, works and commutes to work and which phone numbers on web advertisements it dials.70 The consumer behaviour and device use data that Google collects from smart mobile devices using Android OS, its proprietary applications and APIs for Android includes:71

· contact information (name, address, email address, telephone number);

· account authentication data (username and password);

· demographic information (gender and date of birth);

· information generated by the user through the use of the service (e.g. Gmail messages, user's query including audio, G+ profile, photos, videos and other Google-hosted content);

· credit or debit card details or bank/payment account numbers and associated details (e.g. expiry date/CVV used for Google Payments or identity verification);

· transactional records from app, in-app and content purchases on the Play Store; Identity documents (e.g. government issued identity card/passport/bank statements);

· standard information sent to the web host by the browser software (IP address; URL, including referral terms;

· timestamp;72

· browser attributes, including browser and OS version;

· information about the content served to the user (advertisement, pages visited, etc.);

· interaction data, such as clicks;

· user preferences and other settings;

· location data;

· cookie data;

· device event information including crashes, system activity, hardware settings; Mobile device data (Hardware and OS version);

· unique device identifiers (e.g. International Mobile Equipment Identity, or "IMEI");

· unique advertising identifier, such as the Android Advertising ID;

· mobile network operator;

· battery and volume state;

· telephony log information, such as phone number, calling-party number, forwarding numbers, time and date of calls, SMS routing information and types of calls (used for Google Voice and Hangouts only); and

· device configuration information, such as installed applications, and app usage data.

(111) The ability to collect and combine different valuable user data from its apps and services allows Google to strengthen its ability to present relevant search responses and relevant search advertisements.73

6.2. The shift to mobile and Google's response

(112) Google developed its business model in a PC environment where the web browser was the core entry point to the Internet.

(113) When in the mid-/late 2000s the Internet industry began to shift its focus from PCs to smart mobile devices, Google recognised the opportunities and risks that this shift could bring about for its search-advertising business model.

(114) In terms of opportunities, Google recognised the potential for a significant increase in the use of Google's services74 on smart mobile devices and the collection of valuable user data,75 in particular related to location.76 Smart mobile devices are a particular source of valuable user data, in particular in combination with other user data.77 As Google's CEO, Eric Schmidt, explained: "We are at the point where, between the geolocation capability of the phone and the power of the phone's browser platform, it is possible to deliver personalized information about where you are, what you could do there right now, and so forth—and to deliver such a service at scale."78

(115) In terms of risks, the increase in the number of searches on smart mobile devices provided competing general search services with a chance to increase the numbers of search queries and data gathering. Google's 2007 annual report pointed out: "If we are unable to attract and retain a substantial number of alternative device users to our web search services or if we are slow to develop products and technologies that are more compatible with non-PC communications devices, we will fail to capture a significant share of an increasingly important portion of the market for online services, which could adversely affect our business."79

(116) Another risk was that users would use apps rather than web browsers to access content. Accessing content via apps rather than browsers meant that users would not use Google's general search service to discover content.80

(117) When developing a strategy for responding to the shift to mobile, Google also had to take into account the fact that it was a relatively late entrant in the mobile space and that it was not vertically integrated in the production of smart mobile devices (like Apple).81

6.2.1. Google Search as default on smart mobile devices

(118) One step that Google took was to enter into agreements with OEMs and MNOs whereby Google Search became the default general search service on one or more entry points on their smart mobile devices.

(119) For example, in 2007, Google entered into an agreement with Apple whereby Google Search became the default general search service on all Apple's smart mobile devices since the launch of the iPhone.82 In 2010, Google Search accounted for more than half of the traffic on the iPhone and almost a third of all mobile Internet traffic.83

6.2.2. The development of Android and the Android ecosystem

(120) Another step that Google took was the acquisition and development of the mobile operating system, Android (Section 6.2.2.1).

(121) Google also tried to garner support of a critical mass of OEMs, MNOs and other industry players willing to adapt a new operating system by developing the Android ecosystem, in particular via the Open Handset Alliance ("OHA") (Section 6.2.2.2).84

6.2.2.1. The development of Android

I. Android Open Source Project

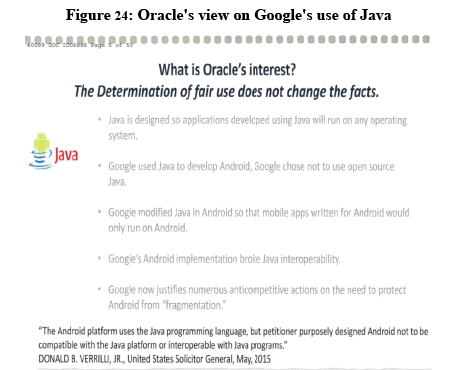

(122) Android85 is an operating system based on the Linux kernel and built on the programming language Java, albeit with important modifications. This has led to the fact that, while app developers could still use the Java language to write apps for Android, their apps would not run on the Java platform.86

(123) Google acquired the original developer of Android, Android, Inc., in 2005.88 It released the first Android version inside Google and the OHA in 2007, with the first commercial Android phones coming out in 2008/9.89

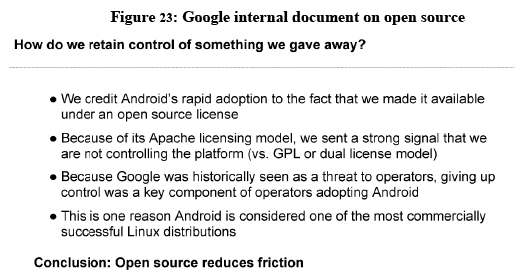

(124) Google makes the source code of Android available for free via the Android Open Source Project ("AOSP")90 and under an open source91 licence ("AOSP licence").92 This means that anybody can access the AOSP source code and create modified versions of it (so-called "Android forks"). These were major selling points to get OEMs and MNOs to join the OHA.93

(125) However, at the same time, Google has an important influence on the key steps of the development of Android.

(126) First, Google does most of the development of the source code of the Android platform.94

(127) Second, the governance model of Android is run by Google, which determines the roadmap, decides on features and new releases and tightly controls the compatibility of derivatives. Source code contributions by developers other than Google are verified and approved by people in the AOSP governance structure that are typically Google employees.95 A part of the development of the code is also done privately by Google.96

(128) Third, Google unilaterally decides when the source code of the Android platform is made available. Until October 2016, Google generally worked on the next version of the Android platform and released the source code of the Android platform in tandem with the launch of a flagship device,97 which between 2010 and 2016 was a Google Nexus device developed together with a chosen OEM.98 Google has confirmed that it releases the source code of the Android platform only after it has been developed and the first flagship devices have been launched: "code updates (…) become available shortly after the launch of the newest Android lead device".99 However, Google can delay (and has delayed) the release of the source code further. For example, in March 2011, Google announced that, for the time being, it would not be providing public access to the source code of the then latest version of Android – Honeycomb.100

(129) On 4 October 2016, Google unveiled its Pixel phones as the launch device for Android 7.1 Nougat.101 Google's Pixel phones are no longer developed together with a chosen OEM but rather designed and marketed by Google. Google also declared that it currently has "no plans" to continue to develop Nexus devices together with a chosen OEM.102

(130) Google's important influence on the key steps of the development of Android is confirmed by evidence on the Commission's file. According to a report by the Open Governance Index analysing eight open source projects, "[a]ll in all, Android is the most closed open source project, whilst also the most commercially successful mobile software platform to date."103 In its internal documents, Google states that it "define[s] the standard and shape[s] the [Android] ecosystem".104 [OS provider] indicates that Google holds "the copyright to source code not released under open source licence, and decides when and to whom to disclose the new versions of Android source code".105 Apple states that Google has a "tight control of Android".106 Amazon.com, Inc. ("Amazon") submits that not all versions of Android are made available under an open source licence.107

(131) In this Decision, smart mobile devices that run on any version of Android, including Android forks,108 are referred to as "Android devices". The versions of Android running on these devices are collectively referred to as "Android". In addition, smart mobile devices approved explicitly or tacitly109 by Google as "Android compatible" are referred to as "Google Android devices". The versions of Android running on Google Android devices are collectively referred to as "Google Android". The term Google Android, therefore, excludes Android forks. Lastly, smart mobile devices which in addition to running on Google Android also pre-install the mandatory Google apps as defined in Section 6.3.2 are referred to as "GMS devices".

II. Play Store

(132) Google has offered an app store for Google Android since 2008. An early version of its app store was called Android Market, which in March 2012 was integrated into Google Play and became the Play Store.110

(133) The Play Store is part of Google Mobile Services ("GMS"), the bundle of Google apps and services that Google licenses together.111

(134) Unlike other Google apps, the Play Store is not downloadable and thus needs to be pre-installed by OEMs in order for users to have access to it. While Google does not prohibit the pre-installation of other app stores, developers cannot distribute alternative app stores via the Play Store.112

(135) In order to have access to the Play Store, users need to have a Google Account. A Google Account requires the creation of a Gmail account, unless the user already has a Google Account.113

(136) Apart from allowing users to download apps, the Play Store allows users to rate apps from one to five and is important for other functions, such as payments or the updating of apps.114

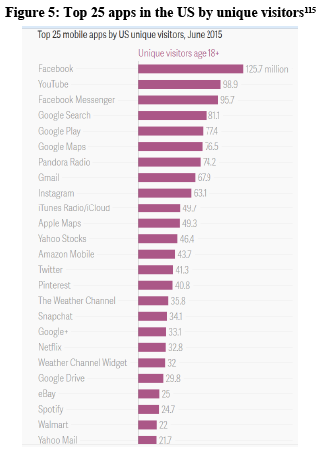

(137) The Play Store is amongst the most widely used apps for smart mobile devices and the only app store in the list of 25 most visited apps in the US in June 2015.

III. Google Play Services

(138) Google Play Services is a Google proprietary software layer that provides background services and APIs for apps integration with Google's proprietary cloud services.

(139) Google Play Services was launched in 2012116 and its main components are the Google Play Services APK and the Google Play Services client library.117

(140) The Google Play Services APK contains the various Google services and runs as a background service in Android. The Google Play Services client library contains the interfaces to the individual Google services and allows Google's proprietary and third party apps to obtain authorisation from users to gain access to these services with their credentials.

(141) Almost all of Google's proprietary apps use Google Play Services.118

(142) The Google Play Services library is also integrated in a large number of third party apps that embed Google's services in their apps for functionalities, such as push notifications, location and maps.119 According to AppBrain, more than 60% of the most downloaded apps in the Play Store use the cloud messaging service of Google through the Google Cloud Messaging library.120 45% of all Android apps also contain the library for AdMob, Google's mobile advertising service.121 Without access to these services, many apps would either crash, or lack important functions.122

(143) While Google Play Services and the Play Store are technically two distinct products, they are closely interlinked in a number of ways.

(144) First, the Play Store and Google Play Services are licensed together as part of the GMS bundle, and Google does not license them separately.

(145) Second, at its launch, Google Play Services was automatically delivered through the Play Store on all Android devices on which the Play Store was installed.123

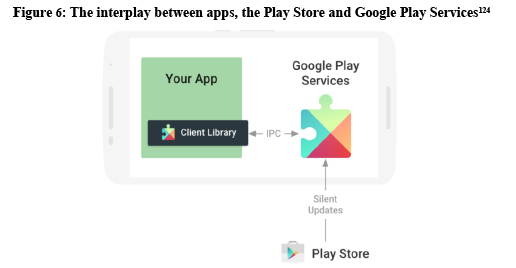

(146) Third, any update to Google Play Services automatically comes through the Play Store, without the need for any action by the user or OEM, as shown in Figure 6.

(147) Fourth, as discussed in Section 9.4.4, a substantial proportion of apps downloaded through the Play Store would not function properly unless Google Play Services is pre-installed on a smart mobile device.

6.2.2.2. Development of the Android ecosystem

(148) In order to compete with established companies in the mobile industry, Android needed the support of other industry players, in particular OEMs, MNOs and app developers.125

(149) Accordingly, in 2007, Google established the Open Handset Alliance ("OHA") and tried to convince other companies to join the alliance.

(150) Among the 34 original founding members of the OHA were a number of important OEMs (e.g. Samsung Electronics ("Samsung"), Motorola, Inc. ("Motorola")), MNOs (e.g. T-Mobile International AG ("T-Mobile"), Telefónica S.A. ("Telefonica")) and other leading technology and mobile industry companies (e.g. Qualcomm Inc. ("Qualcomm"), Intel Corporation ("Intel"), eBay Inc. ("eBay")).126

(151) As the lead developer of the Android platform, Google has implemented a strategy based on different degrees of involvement from OEMs, MNOs and app developers:127

(1) OEMs. Google provides Android for free under the AOSP licence, which allows OEMs to customise their devices to some extent – as long as they still qualified as "compatible" and did not lead to fragmentation as defined by Google.128

(2) MNOs. Google allows MNOs to add apps to devices in order to generate additional revenue in addition to mobile subscription fees. Certain MNOs also receive a share of the revenues that Google achieves with Google Search – subject to exclusivity.129

(3) App developers. Google ensures130 that app developers have incentives to participate in the Android ecosystem as when developers write apps for Android, a positive feedback loop ensues: Android becomes more attractive to users, which in turn, makes Android more attractive to developers. For example, a week after the announcement of the establishment of OHA in 2007, the Android SDK was released to enable developers to create apps for the Android platform131 free of charge, but solely to be used to develop apps that run on Google Android devices.

6.2.2.3. Google's activities at the level of smart mobile devices

(152) As mentioned in Section 6.2.2.1, while Google is active at the level of smart mobile devices with its Nexus and Pixel devices, the majority of smart mobile devices are sold by OEMs that run Android with GMS installed. OEMs compete amongst each other, with Google's Nexus and Pixel devices and with the manufacturers of smart mobile devices powered by different smart mobile OSs.

(153) The extent to which competition at the level of smart mobile devices has an impact on Google is explained in detail in Sections 7.3 and 9.3.4. However, in order to understand properly the impact of such competition on Google, it is important to keep in mind Google's business model. Unlike Apple, whose business model is based on vertical integration and the sale of higher-end smart mobile devices, Google's business model is based first and foremost on increasing the audience for its online services so that it can sell its search advertising.132

(154) This is why Google has, inter alia, entered into an agreement with Apple to become the default general search service for the Safari browser on Apple's smart mobile devices.133 This agreement allows Google to also achieve substantial revenues on Apple devices (see Table 16).

6.3. Google's agreements with members of the Google Android ecosystem

(155) Google has entered into a number of agreements with members of the Google Android ecosystem, in particular:

(1) Anti-fragmentation Agreements ("AFAs");

(2) Mobile Application Distribution Agreements ("MADAs"); and

(3) Revenue share agreements for Google Search.

(156) The relationship between the AOSP licence, AFAs, MADAs and Google's proprietary apps and intellectual property related to Android can be summarised as follows:

(1) The AOSP licence does not grant hardware manufacturers the right to distribute Google's proprietary apps such as Google Search, Google Chrome, the Play Store and Google Play Services. The AOSP licence further does not grant members of the Android ecosystem the right to use the Android logo and other Android related trademarks that Google owns.134

(2) In order to obtain those rights, Google requires hardware manufacturers to enter into a MADA. In order, however, to be eligible to enter into a MADA, Google requires hardware manufacturers first to enter into an AFA.

6.3.1. Anti-Fragmentation Agreements

(157) Pursuant to an AFA, hardware manufacturers commit to the following:

(1) "[COMPANY] will only distribute Products that are either: (i) in the case of hardware, Android Compatible Devices; or (ii) in the case of software, distributed solely on Android Compatible Devices";

(2) "[COMPANY] will not take any actions that may cause or result in the fragmentation of Android"; and

(3) "[COMPANY] shall not distribute a software development kit (SDK) derived from Android or derived from Android Compatible Devices and [OEM] shall not participate in the creation of, or promote in any way, any third party software development kit (SDK) derived from Android, or derived from Android Compatible Devices".135

(158) These clauses of the AFA referred to in recital (157) are hereinafter referred to as the "anti-fragmentation obligations".

(159) The stated objective of the AFAs "is to define a baseline implementation of Android that is compatible with third-party apps written by developers."136 As explained on the Google Android website, "only devices that are 'Android compatible' may participate in the Android ecosystem, including Google Play; devices that don't meet the compatibility requirements exist outside that ecosystem."137

(160) In its internal documents, Google also refers to the fact that AFAs are meant to "Stop […] our partners and competitors from forking Android and going alone".138 In other words, members of the Android ecosystem "didn't just commit to ship Android- compatible devices; they committed to *not* ship incompatible devices".139

(161) In order to build an Android compatible device, hardware manufacturers must comply with the Android Compatibility Definition Document ("CDD") and pass the Compatibility Test Suite ("CTS") (together the "Android compatibility tests").140 The CDD enumerates the software and hardware requirements of a compatible Android device.141 The CTS is an automated testing tool that can be run on a target device or simulator to determine compatibility.142 Both are available via the Android webpage and developed, amended and adopted by Google.143

(162) Only hardware manufacturers that pass the Android compatibility tests can use the "Android" name on hardware, packaging or marketing materials of devices.144 In addition, only those hardware manufacturers can make use of the Android logotype and the Android compatibility trademark.145

(163) The conditions for the Android compatibility tests are determined at Google's sole discretion: "Yandex states that the CDD is "adopted and amended at the sole discretion of Google". This is correct. […] The fact that Google has the last word on how to define compatibility in the CDD, however, does not mean that Android partners cannot update compatibility criteria with incompatibilities and bugs they discover. In fact, since the CDD and CTS are open source, everybody can contribute. Google considers these contributions carefully, many of which concern bug fixes in the CTS or additional tests for CDD requirements or new Android features."146

(164) Google has entered into AFAs with hardware manufacturers active throughout the world, including OEMs, contract manufacturers (also known as original design manufacturers, or "ODMs") and chipset manufacturers.

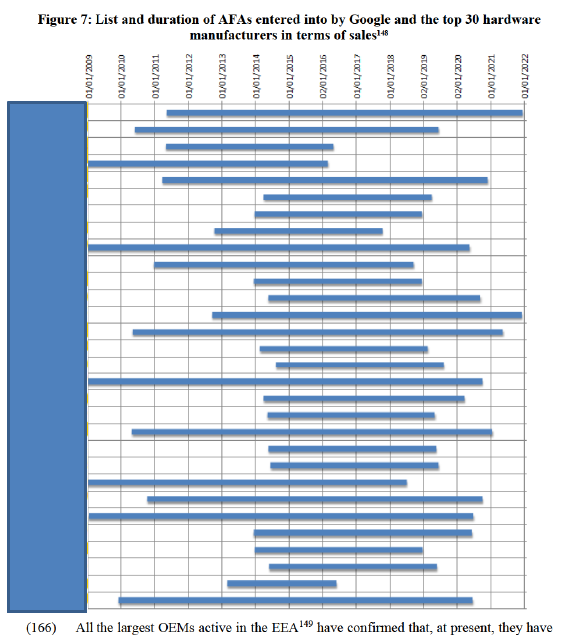

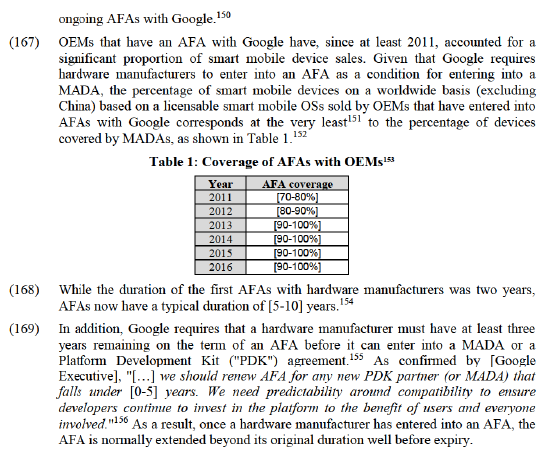

(165) Figure 7 shows the AFAs that Google has entered into since 2009 with the top 30 hardware manufacturers in terms of sales. It also shows the duration of those agreements.147

(170) On 28 March 2017, Google informed the Commission of its intention to notify hardware manufacturers of the option to enter into an "Android Compatibility Commitment" ("ACC") in place of an AFA.157

(171) Contrary to the AFA, the ACC option would permit hardware manufacturers to:

(1) Manufacture incompatible Android devices for a third party that are marketed under a third-party brand;158 and

(2) Supply components to a third party to be incorporated into incompatible Android devices that are marketed under a third-party brand.159

6.3.2. Mobile Application Distribution Agreements

(172) The MADA grants hardware manufacturers a number of rights.

(173) First, hardware manufacturers have the right to pre-install and distribute a number of Google apps on their Google Android devices.160

(174) Second, hardware manufacturers can sublicense the Google apps to MNOs, other distributors and contractors responsible for testing, evaluation and development.161

(175) Third, hardware manufacturers have the right to use Google's trademarks, subject to the Google Mobile Branding Guidelines.162

(176) The MADA also imposes a number of obligations on hardware manufacturers.

(177) First, hardware manufacturers "may not, and may not allow or encourage any third party to: […] (e) take any actions that may cause or result in the fragmentation of Android".163

(178) Second, all devices running Android, including those on which hardware manufacturers do not pre-install Google's apps, must pass the CTS. Hardware manufacturers must also send the CTS report to Google.164

(179) Third, hardware manufacturers must send the final software build of their GMS devices for final approval by Google.165

(180) Fourth, once a hardware manufacturer decides to pre-install one or more Google proprietary apps on its devices, it must pre-install all mandatory Google apps.166

(181) While each MADA lists the mandatory and optional Google apps, there may be variations of such lists at country level, since Google may not make all such apps available to hardware manufacturers for pre-installation in every country at the same time (e.g. due to language differences). The variations at country level of the mandatory and optional apps that are available for pre-installation are reflected in the "Google Product Geo-Availability Chart", with which hardware manufacturers should comply and which "may be updated by Google from time to time".167

(182) The number of mandatory Google apps has increased at least until 2014. For example, while the MADA entered into by [MADA signatory] in 2009 required the pre-installation of twelve Google apps,168 [MADA signatory]’s latest MADA, dated 1 March 2014, required the pre-installation of thirty Google apps.169

(183) Pursuant to each MADA, Google has discretion to change the list of mandatory nGoogle apps that must be pre-installed.170 For example, in June 2015, Google decided that a number of mandatory Google apps (Google+, Google Play Books, Google Play Games, Google Play Newsstand, Google Calendar and Google Contacts) should become optional in relation to all hardware manufacturers that had a MADA in place.171

(184) Fifth, hardware manufacturers must place on the device's default home screen172 the icons which give access to the Google Search app, the Play Store and a folder labelled "Google" ("Google folder") that provides access to a collection of icons for a number of mandatory Google apps.173 Any other pre-installed Google apps should be placed no more than one level below the home screen.174

(185) Sixth, hardware manufacturers are required to "set Google Search as the default search provider for all Web search access points, […]".175 In October 2014, Google began to remove the wording of certain MADAs requiring Google Search to be set as the default general search service.176 However, as of April 2017, there remained a number of MADAs in place with language requiring hardware manufacturers to set Google Search as the default general search service.177

(186) Seventh, hardware manufacturers must ensure that direct access to Google Search is provided by either "(a) long pressing the "Home" button on Devices with physical navigation buttons, or (b) swiping up on either the navigation bar or "Home" button on Devices with soft navigation buttons".178

(187) Eighth, hardware manufacturers must "configure the appropriate Client ID for each Device as provided by Google".179 The "Client ID" is a unique alphanumeric code180 that is incorporated in every GMS device and enables the tracking of usage of Google's apps (e.g. the Google Search app) on the device.

(188) Ninth, the MADA typically foresees that Google may terminate the MADA and stop licensing its apps if the hardware manufacturer breaches any obligation in the MADA relating to device compatibility.181 Such obligations include the obligation not to "take any actions that may cause or result in the fragmentation of Android"182 and the obligation for all devices running Android, including those on which a hardware manufacturer does not pre-install Google's apps, to pass the CTS.183

(189) The first hardware manufacturer with which Google entered into a MADA was [MADA signatory] in March 2009.184 Between March 2009 and April 2017, Google entered into MADAs with at least [200-300] further hardware manufacturers, including major hardware manufacturers such as HTC, Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. ("Huawei"), Lenovo Group Ltd. ("Lenovo"), LG Electronics Inc. ("LG Electronics"), Samsung and Sony Corporation ("Sony").185

(190) The duration of a MADA is typically been between [0-5] years, after which Google and the hardware manufacturers have negotiated a new MADA or an extension.186

(191) Google has sought to ensure consistency across the MADAs signed with hardware manufacturers. [Licensing practice].187 One major set of changes, labelled "GMS 2.0", was implemented as of November 2013.188

6.3.3. Portfolio-based revenue share agreements

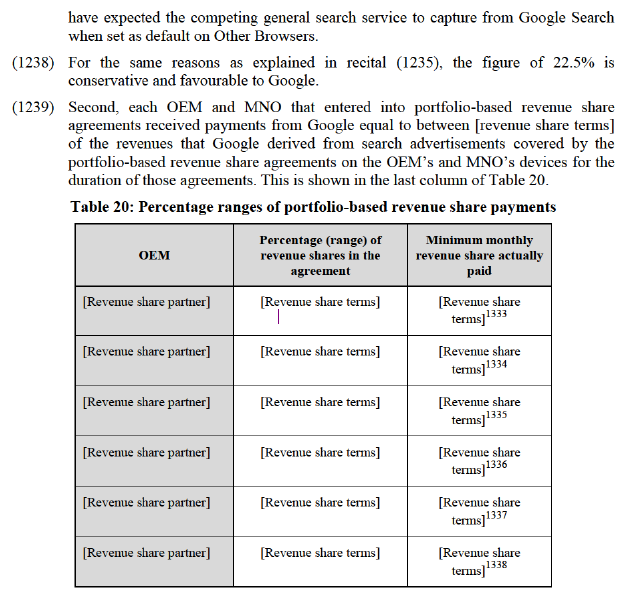

(192) Between 1 May 2010189 and 31 October 2015,190 Google was a party to agreements with at least six OEMs ([revenue share partner], [revenue share partner], [revenue share partner], [revenue share partner], [revenue share partner] and [revenue share partner]) and at least four MNOs ([revenue share partner], [revenue share partner], [revenue share partner] and [revenue share partner]) pursuant to which it shared with them search advertising revenues provided that the OEMs and MNOs did not pre- install any competing general search service on any device within an agreed portfolio ("portfolio-based revenue share agreements"). If an OEM or MNO had pre-installed such a service on any device, it would have foregone the revenue share payments not only for that particular device but also for all the other devices in its portfolio on which another general search service may not have been pre-installed.191

(193) A given device could fall within the scope of […] portfolio-based revenue share agreement with […] an OEM or an MNO. If the OEM that manufactured a device and the MNO that distributed that same device both had portfolio-based revenue share agreements with Google, the OEM and the MNO [explanations concerning revenue share agreements with OEMs and MNOs].192 In practice, the OEM or MNO [explanations concerning revenue share agreements with OEMs and MNOs].193

(194) In this regard, [revenue share partner], stated that: "[explanations concerning revenue share agreements with OEMs and MNOs]".194 Similarly, [revenue share partner] stated that "The [ client ID] specifies to whom Google will pay revenue share. Some of [revenue share partner]'s customers in the EEA, e.g. [revenue share partner], have their own client ID and their own revenue share agreement with Google and will receive revenue share on the Android devices sold".195

(195) Search traffic and revenues generated on OEM and MNO devices were tracked via the Client ID incorporated in every GMS device pursuant to the portfolio-based revenue share agreement.

(196) The geographic scope of the portfolio-based revenue share agreements with OEMs was worldwide. As for MNOs, the portfolio-based revenue share agreements either applied to all the countries of operation of the given MNO or to those countries where the relevant subsidiaries of the MNO opted into a framework agreement negotiated by the mother company through separate accession agreements with Google.

(197) As of March 2013, Google began to gradually replace portfolio-based revenue share agreements in the European Union and the Republic of Korea by agreements pursuant to which the payment of revenue shares by Google was conditional on OEMs and MNOs pre-installing no competing general search service on a given device for which revenue shares were paid ("device-based revenue share agreements").196

(198) For the purposes of this decision, any reference to "pre-install" and "pre-installation" refers not only to the pre-installation of the app of a general search service but also to any other means of making available a general search service to users by OEMs and MNOs immediately after the purchase of a device.

(199) A non-exhaustive list of Google's portfolio-based revenue share agreements with OEMs and MNOs is outlined in the following two Sections.

6.3.3.1. Portfolio-based revenue share agreements with OEMs

(200) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 August 2012.197 The agreement was initially for a period of two years but was later extended to 31 July 2015.198 Pursuant to the agreement, Google agreed to share [revenue share terms]199 of its net ad revenues200 in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it "will not, and will not allow any third party to implement" on any Wi-Fi only tablet GMS devices with a screen size of 7'' or more and that are configured with [revenue share partner]'s Client ID "any application, product or service which is the same as or substantially similar to Google Search Widget or the Google Mobile Search Service (or any part thereof)".201 [Revenue share partner] was, however, entitled to pre-install apps that did not include general search functionality and downloads by users of competing general search services were permitted.202

(201) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 November 2013 for a period of two years until 31 October 2015.203 Google agreed to share [revenue share terms] of its net ad revenues in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it "will not, and will not instruct or encourage any third party to implement" on GMS devices that are configured with [revenue share partner]'s Client ID "any application, product or service which is the same as or substantially similar to the Google Search Widget or the Google Mobile Search Service (or any part thereof)".204 [Revenue share partner] was, however, entitled to pre-install apps whose primary functionality was not general search and downloads by users of competing general search services were permitted.205

(202) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 February 2011 for a period ending on 31 December 2012.206 Google agreed to share [revenue share terms]207 of its net ad revenues in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it "will not, and will not allow any third party to: implement" on Google Android devices "any application, product or service which is the same as or substantially similar to Android Market, Google Phone-top Search or the Google Mobile Search Service (or any part thereof)".208 [Revenue share terms].209

(203) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 January 2013 for a period of one year until 31 December 2013.210 Payments under the agreement were subsequently informally extended until March 2014.211 Google agreed to share [revenue share terms] of its net ad revenues in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it "will not, and will not allow any third party to implement" on Google Android mobile phones, tablets and WiFi-only devices that are configured with [revenue share partner]’s Client ID "any application, product or service which is the same as or substantially similar to Google Search Widget or the Google Mobile Search Service (or any part thereof)".212 [Revenue share partner] was, however, entitled to pre-install apps whose primary functionality was not general search and downloads by users of competing general search services were permitted.213 In addition, the payment of revenue shares was conditioned on [revenue share partner] setting Google Chrome as the default browser on its devices.214

(204) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 January 2011 for a period of two years ending on 31 December 2012.215 Google agreed to pay [revenue share terms]216 of its net ad revenues in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it will not ""pre-install, install, incorporate or otherwise make available" on any Google Android or non-Android devices, excluding […] devices217 that are sold with Google Search, "any application, product, or service which is the same or substantially similar to a Search Client or the Google Search Services".218 [Revenue share partner] also committed not to: (i) pre-install access points to competing general search services; (ii) set the website of a competing general search service as the home page of a pre- installed browser; and (iii) pre-install any app that provides access to a competing general search service. This was a "non-exhaustive list of activities prohibited".219 [Revenue share terms].220

(205) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 October 2011 for a period ending on 30 September 2013.221 Google agreed to share [revenue share terms]222 of its net ad revenues223 in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it "shall not pre-install, install, incorporate or otherwise make available" on any Google Android or non-Android devices that are sold with Google Search "any application, product or service (or links to any of the foregoing) which is the same or substantially similar to a Search Client or the Google Search Services".224 [Revenue share partner] also committed not to: (i) pre- install access points to competing general search services; and (ii) set the website of a competing general search service as the home page of a pre-installed browser. This was a "non-exhaustive list of activities prohibited".225 [Revenue share terms].226

6.3.3.2. Portfolio-based revenue share agreements with MNOs

(206) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 September 2011 until 30 November 2013.227 Google agreed to share [revenue share terms]228 of its app sales revenues made through the Play Store on [revenue share partner]'s devices, and in return for the shares of net ad revenues and app revenues, [revenue share partner] committed that "[n]o widget, pointer, bookmark or application that is substantially similar to Google Search, Google Maps or Android Market may be preloaded on any […]."229 This portfolio-based revenue share agreement applied to all [revenue share partner] subsidiaries in the EEA.230

(207) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 September 2010 for a period of two years until 31 August 2012.231 Google agreed to share [revenue share terms] of its net ad revenues232 in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it "shall not (and shall ensure that Authorised Android OEMs do not and shall use best endeavours to ensure that […] OEMs do not) pre-install, install, incorporate or otherwise make available" on any GMS or Symbian device on which Google Search is pre-installed "any application, product or service (or links to any of the foregoing) which is the same as or substantially similar to the Google Search Client […] or to the Google Search Services".233 The limitation applied only to (links to) applications, products, services that had web search as their primary function.234 The agreement applied to [revenue share partner]'s subsidiaries in [various EEA Member States].235

(208) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 September 2011 for a period of two years, which was subsequently extended for an additional year until 31 August 2014.236 Google agreed to share [revenue share terms] of its net ad revenues achieved by Google on Android smartphones and t]237 afterwards238, in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it "shall not, and shall not allow any [revenue share partner] or any third party […] to pre-install or preload" on any Android device "any Similar Application".239 For the purposes of the agreement, Similar Application is defined as an "application which is the same as or substantially similar to a Google Search Client or the Google Search Services".240 The agreement applied to [revenue share partner]'s subsidiaries in [various EEA Member States].241

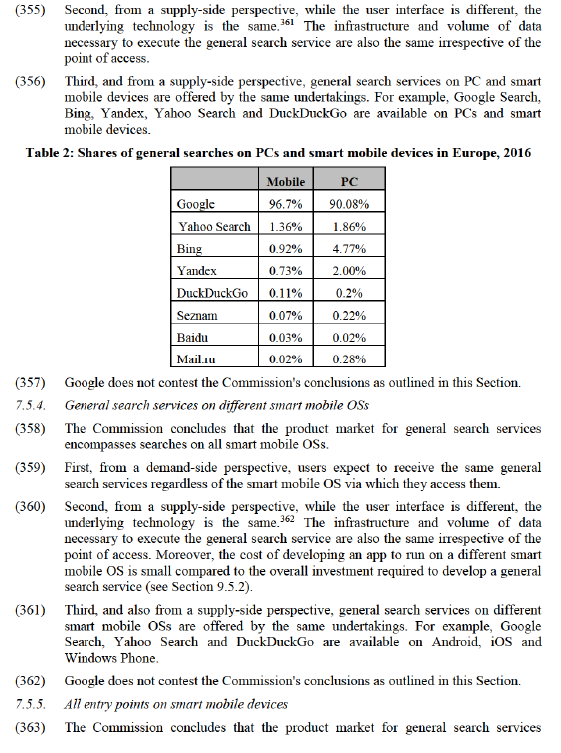

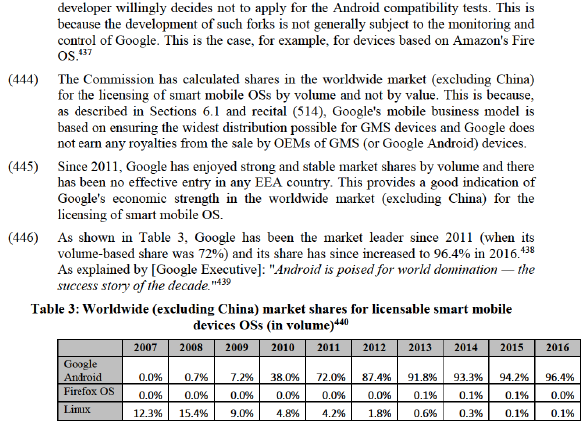

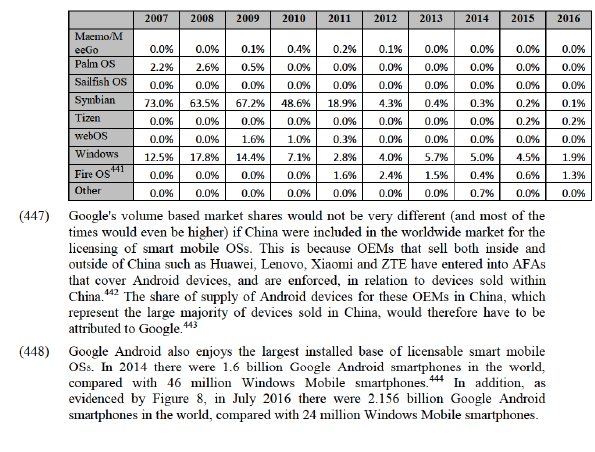

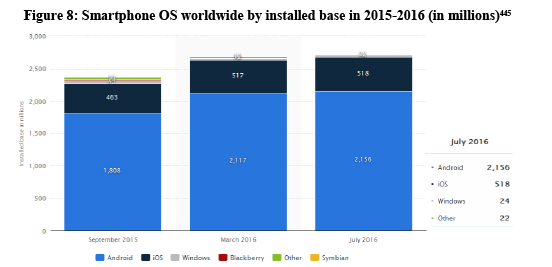

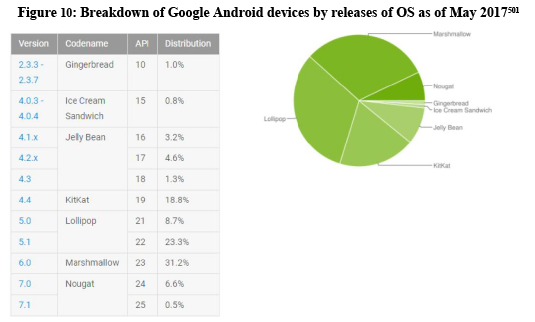

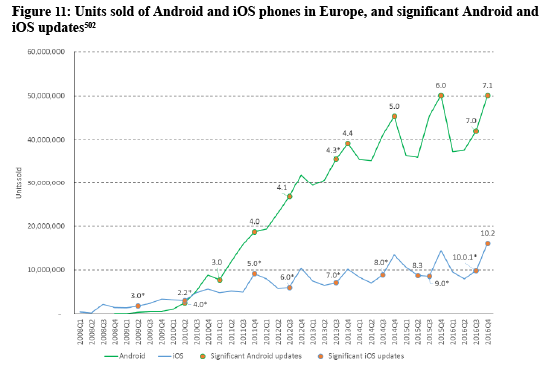

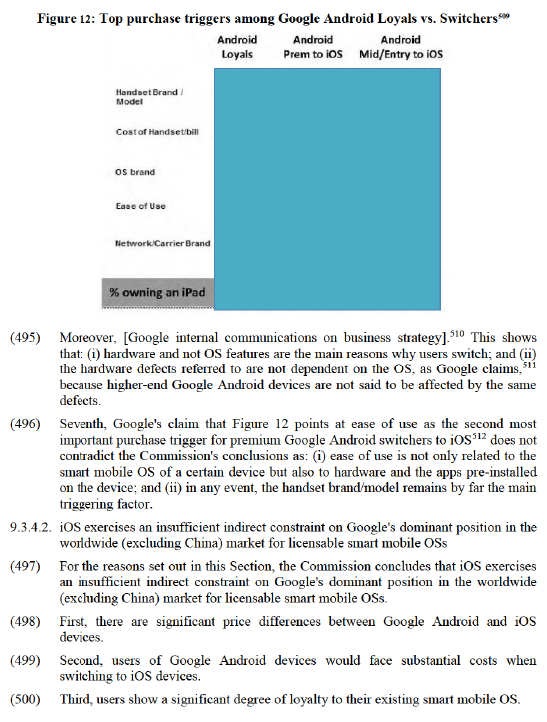

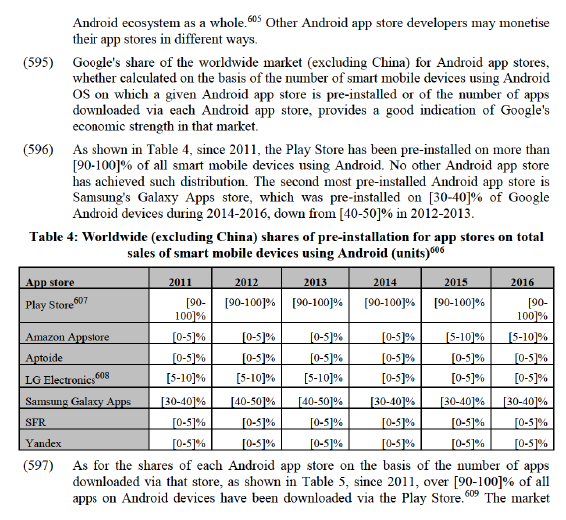

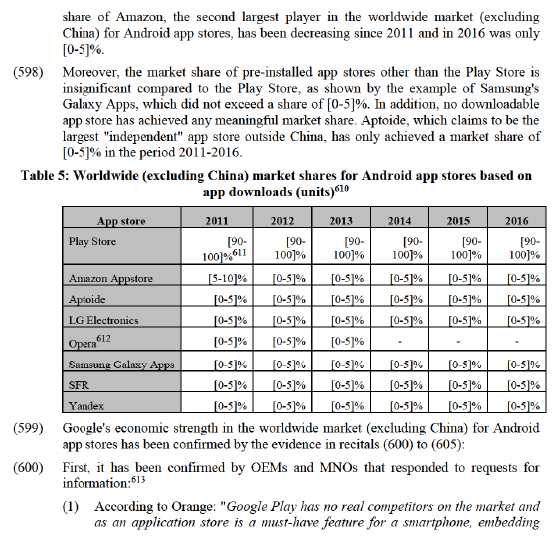

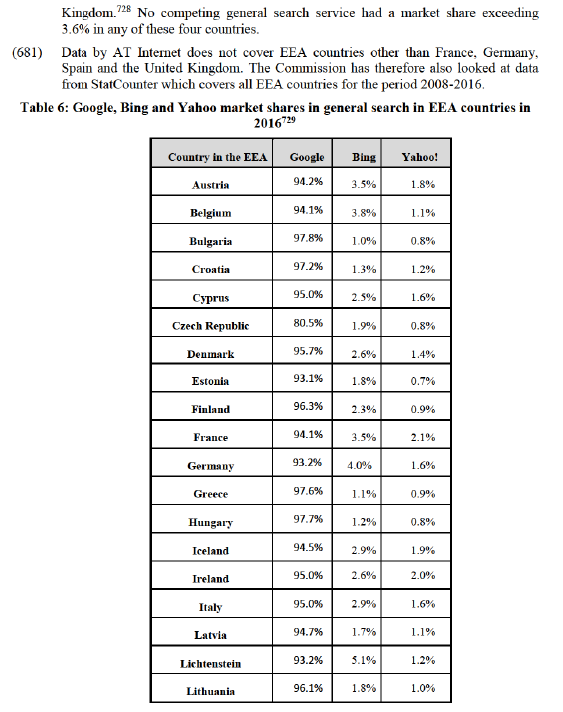

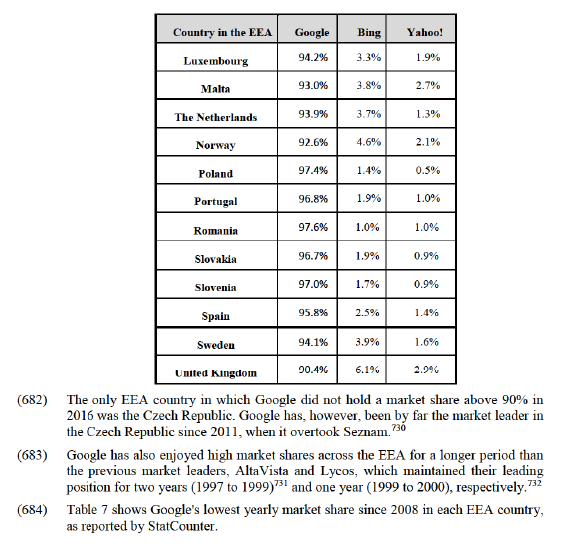

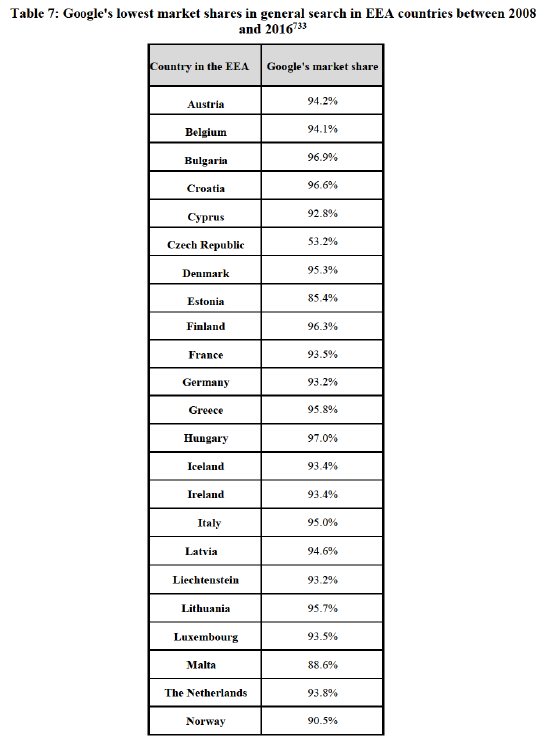

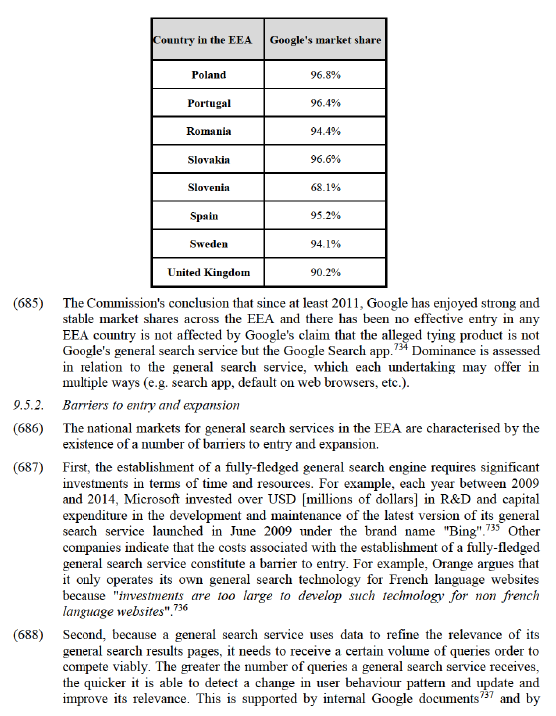

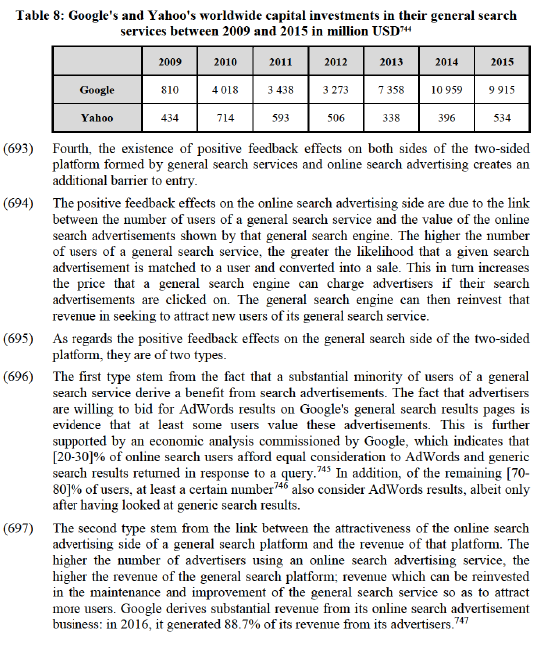

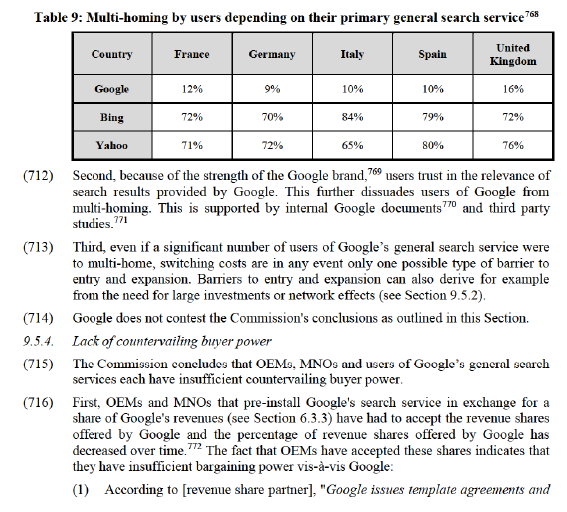

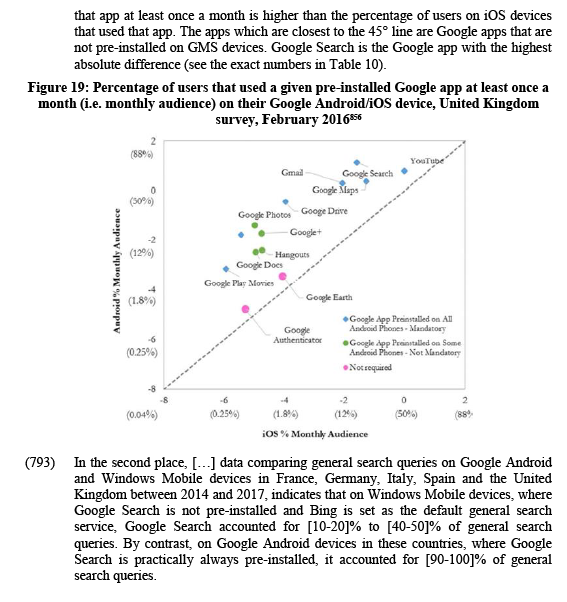

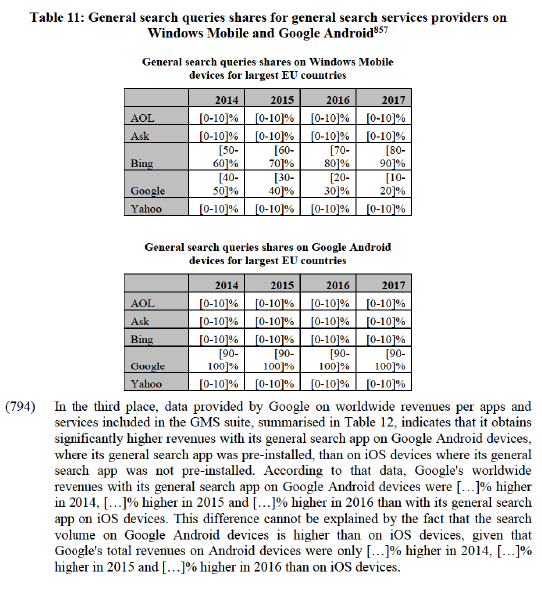

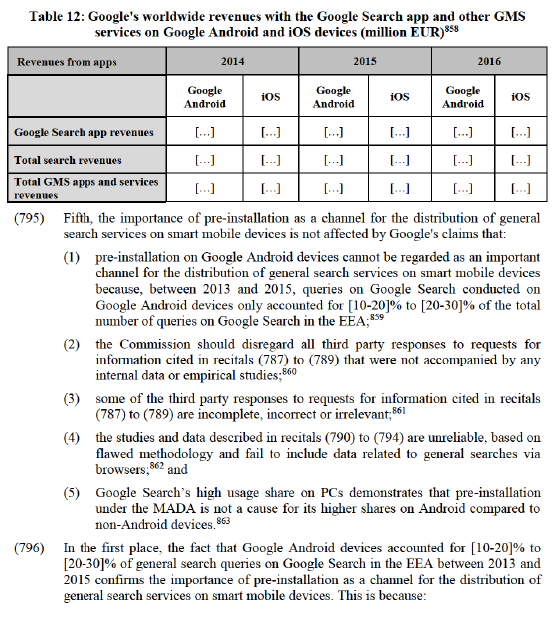

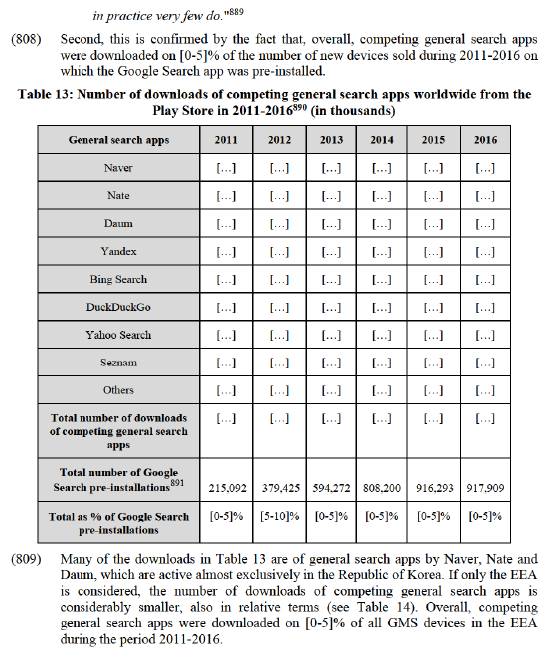

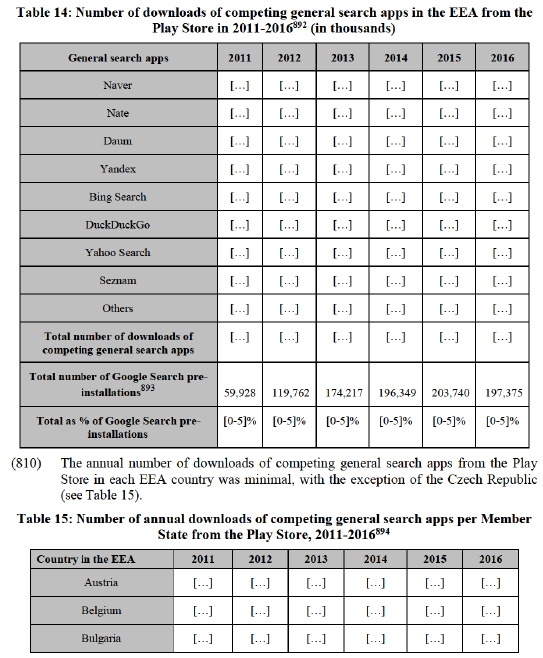

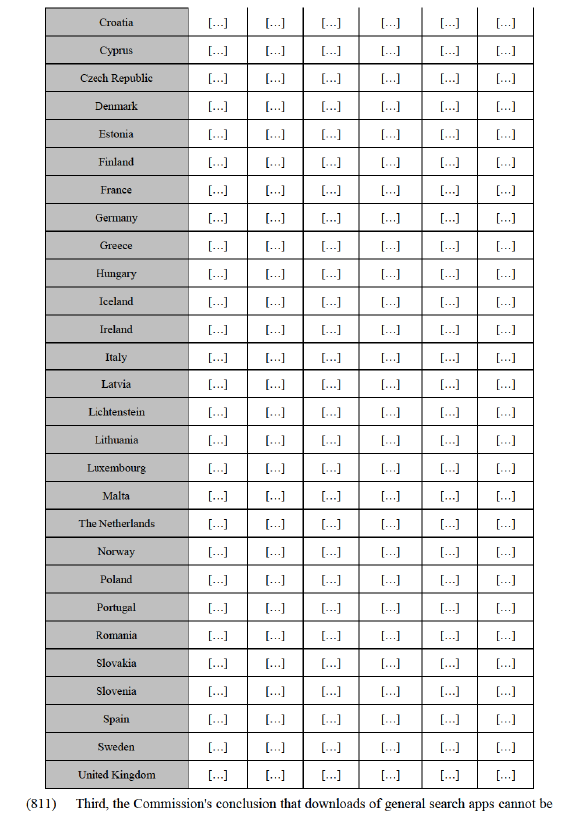

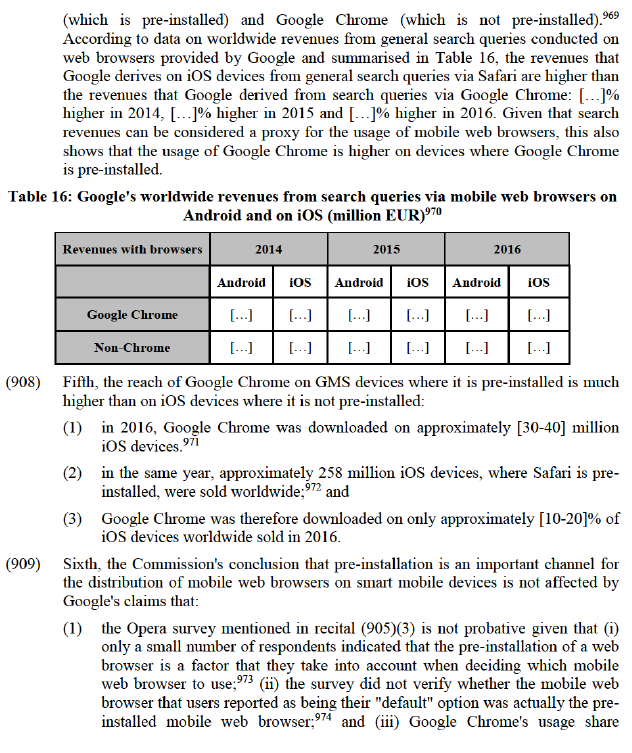

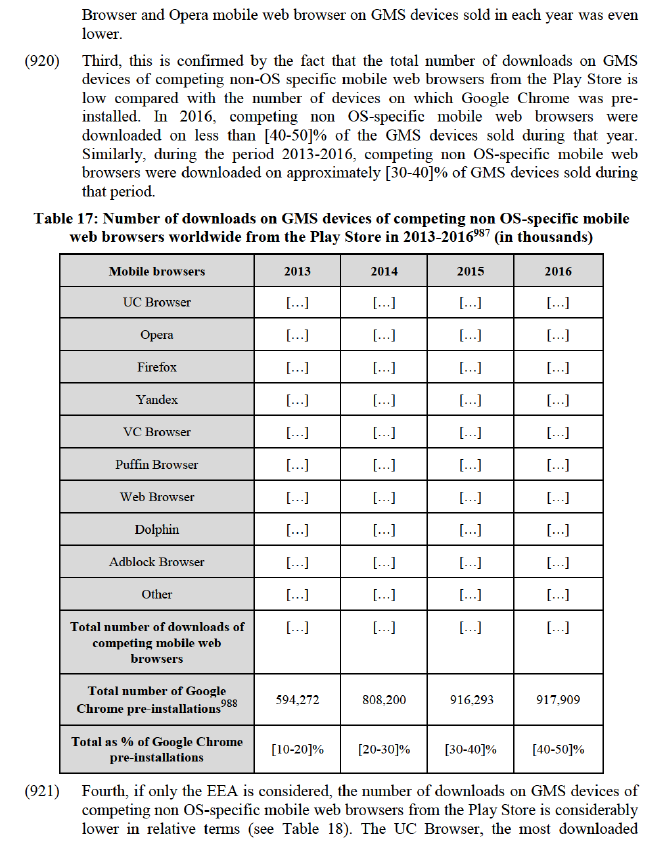

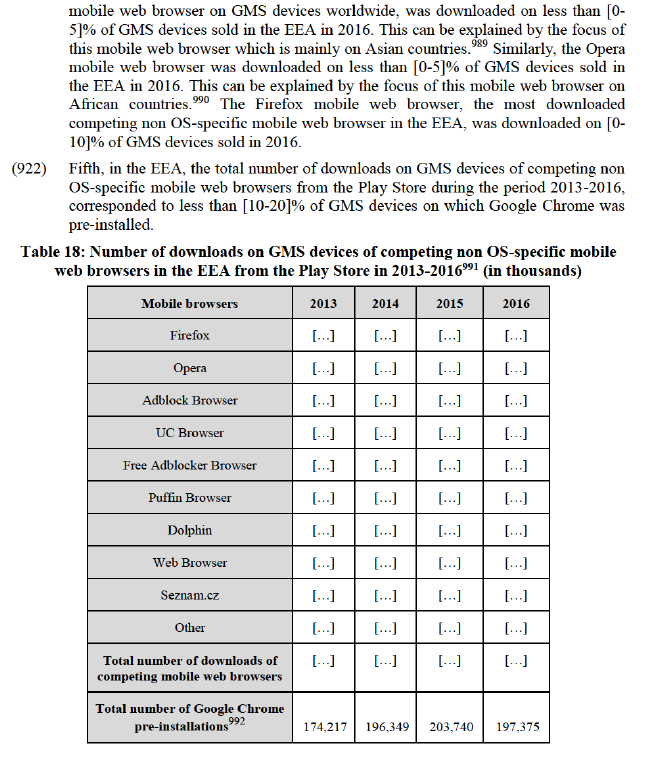

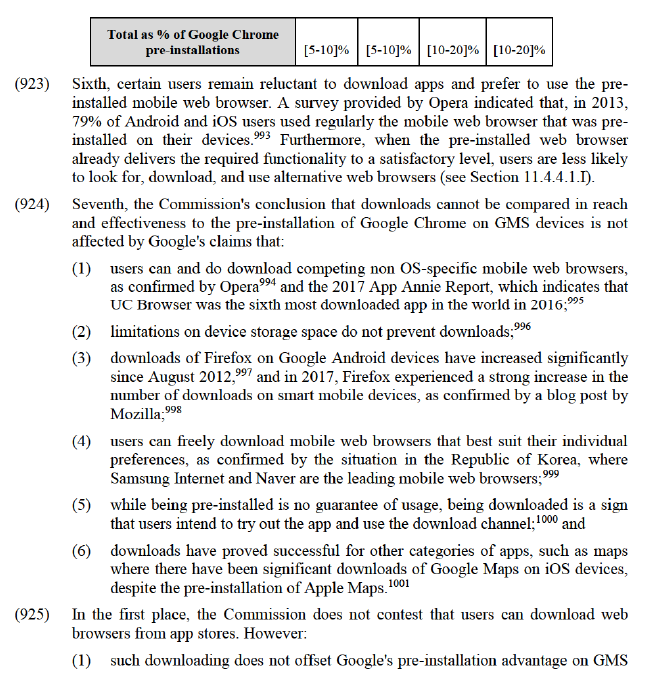

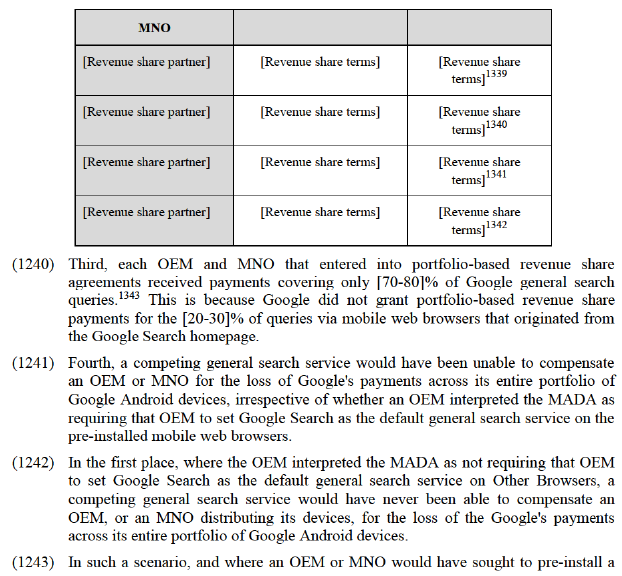

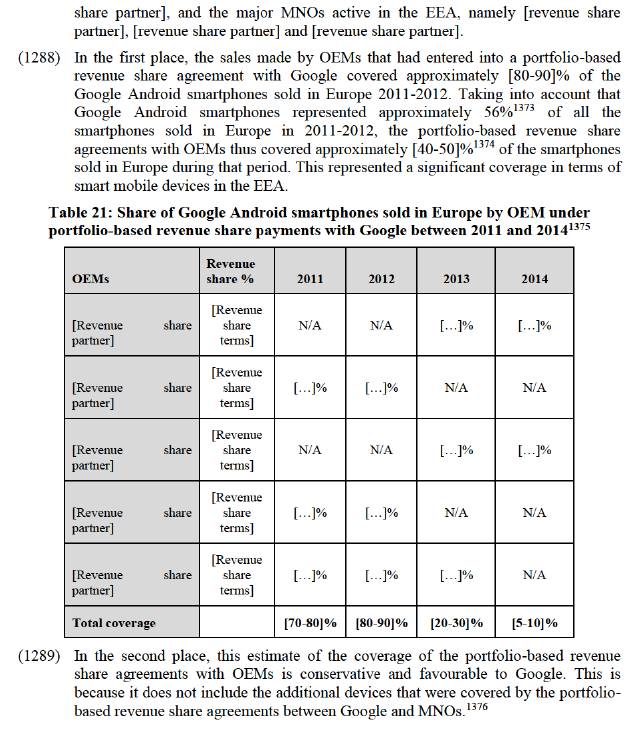

(209) Google and [revenue share partner] entered into a portfolio-based revenue share agreement on 1 May 2010 for a period of three yearablets that bear [revenue share partner]'s Client ID in [revenue share terms] and [revenue share termss.242 Google agreed to share [revenue share terms] of its net ad revenues in return for [revenue share partner] committing that it "shall ensure that […] Google will be the exclusive provider of search and search advertising services presented in response to a Query" on (i) devices on which Google's general search service is pre-installed;243 and (ii) other mobile phones distributed by [revenue share partner] that are "technically capable of running the Google Search Client or Hosted Mobile Search".244 The agreement applied to all [revenue share partner] subsidiaries in the EEA.245