EC, November 12, 2008, No 39125

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES

Decision

Carglass

THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES,

Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty1, and in particular Article 7 and Article 23(2) thereof,

Having regard to the Commission decision of 18 April 2007 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given the undertakings concerned the opportunity to make known their views on the objections raised by the Commission pursuant to Article 27(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 and Article 12 of Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 of 7 April 2004 relating to the conduct of proceedings by the Commission pursuant to Articles 81 and 82 of the EC Treaty2,

After consulting the Advisory Committee on Restrictive Practices and Dominant Positions, Having regard to the final report of the hearing officer in this case3,

Whereas:

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Addressees

(1)This Decision concerns arrangements between the following undertakings active in the automotive glass sector in the EEA:

– Asahi Glass Co. Ltd

– AGC Flat Glass Europe SA/NV (formerly Glaverbel SA)

– AGC Automotive Europe SA

– Glaverbel France SA

– Glaverbel Italy S.r.l.

– Splintex France Sarl

– Splintex UK Limited

– AGC Automotive Germany GmbH

– La Compagnie de Saint-Gobain SA

– Saint-Gobain Glass France SA

– Saint-Gobain Sekurit Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG

– Saint-Gobain Sekurit France SA

– Pilkington Group Limited

– Pilkington Automotive Ltd

– Pilkington Automotive Deutschland GmbH

– Pilkington Holding GmbH

– Pilkington Italia Spa

– Soliver NV.

1.2. Summary of the infringement

(2) This Decision arises out of investigations carried out by the Commission in February and March 2005 pursuant to Article 20(4) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 at the premises of the main producers of carglass in the EEA and concerns the automotive glass industry, in particular the supply of automotive glass to car manufacturers and their network of authorised dealers.

(3) The addressees of this Decision participated in a single and continuous infringement of Article 81 of the Treaty and Article 53 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (hereinafter ‘EEA Agreement’). The infringement consisted in concerted allocation of contracts concerning the supply of carglass pieces and/or carsets4 for all major car manufacturers in the EEA, through coordination of pricing policies and supply strategies aimed at maintaining an overall stability of the parties’ position on the market concerned. In this respect, the competitors also monitored the decisions taken during these meetings and contacts and agreed on correcting measures in order to compensate for each other when previously decided allocations of glass pieces proved insufficient in practice to ensure an overall degree of stability in their respective market shares.

(4) The cartel lasted […] from 10 March 1998 to 11 March 2003.

1.3. Value of sales

(5) In 2002, namely the last full business year of the infringement, the value of sales of the product concerned by this Decision to Original Equipment Manufacturers (hereafter "OEM") in the EEA amounted to approximately EUR [2 000-2 500] million.

PART 1: FACTS

2. THE INDUSTRY

2.1. The product

(6) Automotive glass or carglass is made from float glass, that is the basic flat glass product category. In previous merger decisions5 the Commission has defined the flat glass sector at two levels: level 1 corresponds to the production of raw float glass whereas at level 2 most of the raw float glass is subject to further processing. Within level 2 the main distinction is between the sectors of automotive and general trade.

(7) The automotive products consist of different glass parts such as windshields or windscreens, sidelights (windows for front and back door), backlights (rear window), quarter lights (back window next to rear door window), and sunroofs. Abbreviations are used by the carglass suppliers when referring to specific glass parts.6 The products concerned have specific options and are made with different glass techniques such as windscreens with rain sensor, tinted glass or athermic glass; tempered front door sidelights; laminated front door sidelights; tempered rear door sidelights; laminated rear door sidelights; and fixed backlights.7

(8) The glass parts can moreover be tinted in different colour grades as opposed to clear glass. "Privacy" glass, or "dark tail" glass, is a specific category of tinted glass which reduces light and heat transmission inside the car and can be defined as any glass whose light transmission falls below 70%.8 The Saint-Gobain group is market leader with its brand ‘Venus’ available in green and grey with different thicknesses and transmission properties.9 ‘Sundym’, which is Pilkington’s brand, is grey and has a similar range of varieties. Finally, ‘Athergreen’ or ‘Atherman’, which is green, is the AGC brand.

(9) Carglass is a kind of safety glass. This is because it does not shatter into sharp pieces on impact, which could be dangerous to occupants of the vehicle in the event of accident. There are two types of safety glass: laminated glass10 which is mainly used in windscreens, and toughened glass11 (or body glass/tempered glass) which is mainly used in side and rear windows where there is need for extra strength. In addition, carglass manufacturers offer carglass with additional features such as built-in antennas for radio and mobile phones, rain sensors for automatic wiper activation or solar heat reduction.

(10) The Commission has made a further distinction between automotive glass supplied to the OEM both for first assembly into vehicles and for further resale to their authorised repairers as spare parts ( that is to say, the Original Equipment or "OE" channel), on the one hand, and automotive glass for replacement (“ARG”) which is sold directly by carglass producers to the aftermarket on the other hand.12 The aftermarket consists of repairers authorised by the car manufacturers and independent repairers (the so- called "independent after-market", or “IAM”), which concerns auto replacement glass sold to repair chains (such as the […] chain), other carglass wholesalers, repairers, body repair shops and fitters.

(11) Although the production of carglass sold to the aftermarket sometimes takes place at the same production lines as the carglass for the OE channel, the supply and demand characteristics are totally different for the following reasons.13 Firstly, the customers are different and require a different distribution system. While sales to OEM are in large quantities, sales to the IAM are in their majority in small quantities and need a completely different logistic. Secondly, the price for a piece of carglass is considerably higher when sold directly to the replacement market than to OEMs. Thirdly, all three major producers of carglass have separate legal divisions for OEM and IAM. Fourthly, the glass pieces do not carry the logo of the car manufacturers and are, therefore, marketed differently. Lastly, the ARG divisions of the carglass manufacturers also buy from other suppliers and, therefore, have a trading/wholesale function which is not the case for OEM supplying their own network. The three major OE suppliers have well- developed independent aftermarket distribution and wholesale networks in the EEA through dedicated ARG subsidiaries with separate management teams: Autover in the case of Saint-Gobain, Pilkington AGR for Pilkington and AGC Automotive Replacement Glass for Glaverbel.

(12) This Decision relates only to carglass supplied to the OE channel for use in passenger cars and light commercial vehicles (below 3.5 tonnes).

2.2. The market players

2.2.1. Undertakings subject to the present proceedings

2.2.1.1. Saint-Gobain

(13) La Compagnie de Saint-Gobain SA (hereafter "Saint-Gobain") is a French-based listed company and the ultimate parent company of a global group of companies active in the production, processing and distribution of materials (glass, ceramics, plastics, cast iron, etc.). The total consolidated turnover of the group in 2007 was EUR […] million. The Flat Glass Sector is one of five business lines of Saint-Gobain. It brings together Saint- Gobain’s four main flat glass activities, the manufacture of basic flat glass products, the processing and distribution of glass for the building industry, flat glass products for the automotive industry and the production of specialty glass. Saint-Gobain's wholly owned subsidiary dealing with flat glass (including carglass) is called Saint-Gobain Glass France SA which had in 2007 a consolidated turnover of EUR […] million.

(14) Saint-Gobain's carglass activities are grouped under the Saint-Gobain Sekurit (“SGS”)-umbrella, which is part of the Flat Glass Sector led by […].14 SGS is not a legal entity but a business structure within Saint- Gobain. Under the SGS-umbrella there are several national companies such as Saint-Gobain Sekurit Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG in Germany and Saint-Gobain Glass France SA in France.15 For the purposes of this Decision, all the entities belonging to the Saint-Gobain group of companies are collectively referred to as "Saint-Gobain".

(15) During the February and March 2005 inspections, the Commission inspected the premises of the following Saint-Gobain subsidiaries: Saint- Gobain Glass France SA; Saint-Gobain Sekurit France SA; Saint-Gobain Sekurit Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG; and Saint-Gobain Oberland AG.

2.2.1.2. Pilkington

(16) Pilkington Group Limited (formerly Pilkington plc, hereafter "Pilkington") is one of the largest manufacturers of glass and glazing products for building, automotive and related technical markets world-wide. In the pro- forma financial year ended on 31 March 2008 Pilkington generated annual revenues of GBP […] million, that is approximately EUR […] million16. Since 16 June 2006 Pilkington has been a wholly owned subsidiary of the intermediate holding company NSG UK Enterprises Limited, which in turn is wholly owned by the Japan-based company Nippon Sheet Glass Company Ltd.

(17) Pilkington’s carglass business is grouped under the name Pilkington Automotive. For most of the EEA-States, there are national subsidiaries such as Pilkington Automotive Deutschland GmbH and Pilkington Italia SpA, all these subsidiaries being (indirectly) wholly owned by Pilkington. For the purposes of this Decision, all the entities belonging to the Pilkington group are collectively referred to as "Pilkington".

(18) During the February and March 2005 inspections, other than the group holding company Pilkington plc, the Commission inspected the premises of the following Pilkington plc's subsidiaries: Pilkington Automotive Deutschland GmbH; Pilkington Italia SpA and Pilkington Automotive Ltd.

2.2.1.3. Asahi Glass Co Ltd

(19) Asahi Glass Co Ltd. (hereafter “Asahi”) is a Japanese producer of glass, chemicals and electronic components. In 2007 the world-wide turnover of Asahi was approximately EUR 10 426 million. Since 1981 Asahi has owned a majority stake in the Belgian firm Glaverbel SA/NV (hereafter "Glaverbel"), which was [50-60]% in 1997 and increased to [80-90]% in May 2002. Since 15 December 2002 Asahi has owned 100% of Glaverbel.17 On 1 September 2007 Glaverbel changed its name into AGC Flat Glass Europe SA/NV. To clarify, AGC Flat Glass Europe SA/NV is the addressee of this Decision. However, in this Decision it is also referred to by its old name, namely Glaverbel.

(20) Carglass in Europe is produced and distributed by an (indirectly) wholly owned subsidiary of Glaverbel, AGC Automotive Europe SA (hereafter “AGC Automotive”). Prior to 1 January 2004, the name of AGC Automotive was Splintex Europe SA and, prior to January 2002, AS Technology. Until 2001 the automotive glass activities were carried on by another Glaverbel subsidiary, Splintex SA, from which, on 31 May 2001, AS Technology, another Glaverbel subsidiary, acquired the carglass activities. AS Technology changed its name to Splintex Europe SA and Splintex SA was liquidated on 26 January 200218. AGC Automotive Germany GmbH, Splintex UK Limited, Glaverbel France SA, Splintex France Sarl as well as Glaverbel Italy Srl, all subsidiaries of Glaverbel, were also involved in the events described in this Decision. For the purposes of this Decision, the entities mentioned in recital 19 and this recital are collectively referred to as "AGC". In 2007, Glaverbel's total world-wide consolidated turnover amounted to approximately EUR […].

(21) During the February […] 2005 inspections, the Commission inspected the premises of Glaverbel and AGC Automotive.

2.2.1.4. Soliver

(22) Soliver NV (hereafter "Soliver") is a smaller, family-owned Belgian glass manufacturer. Since it does not have in-house flat glass production, it has to buy the raw glass from the integrated companies such as Saint-Gobain. Soliver is active in the sector of automotive and building glass. It has two subsidiaries, which also produce carglass: Soliver Waregem NV in Belgium and Soliver France SA in France. In 2007, the total turnover of Soliver was approximately EUR […] million.

(23) During the February 2005 inspections, the Commission inspected the premises of Soliver in Roeselare.

2.2.2. Other market players

2.2.2.1. Guardian Industries Corp

(24) Guardian Industries is one of the world's largest manufacturers of flat glass and fabricated glass products, headquartered in the United States. Guardian’s wholly owned European subsidiary Guardian Europe S.A.R.L., based in Luxembourg, manufactures and supplies carglass to the EEA car industry.

2.2.2.2. PPG Industries Inc

(25) PPG Industries Inc (hereafter "PPG") is a diversified US-manufacturer that manufactures and supplies among others flat glass and fabricated glass. Total turnover of PPG in 2005 was EUR […] million. PPG sold its entire European automotive glass business to Glaverbel in 1998.19 However, PPG supplies to both OEMs and ARG customers in Europe from its United States and Canadian plants.

2.2.2.3. Other suppliers

(26) Apart from the suppliers mentioned above there are some other suppliers located outside the EEA with very little turnover in the EEA whose combined share is less than 1%. In early 2000, Renault and Fiat started to work with Traykya Cam, a Turkey-based glass supplier, and in 2005 Fuyao Glass entered the EEA market as well.20

2.3. Description of the industry

2.3.1. Supply

(27) The bus and truck sectors and specialised transports sectors apart, the carglass suppliers focus on the light vehicle industry, in particular passenger cars.21 Vehicle manufacturers' needs for their car models are clearly differentiated, as each type of window has specific features both from a technical and design point of view. These requirements for innovative shaping and for technical innovations such as solar heat reduction or rain sensors have favoured large integrated suppliers with a global reach. There are very few global players, among them AGC, Pilkington and Saint-Gobain, which are also by far the three leading suppliers. Other suppliers like Soliver have a rather regional footprint and are often lacking the technical expertise in particular for complex and demanding windshields. While the big three are capable of offering the entire carglass set for all types of vehicles, smaller suppliers often bid for selected parts of the glazing only.

(28) For most of the supplies the carglass manufacturers are called "tier 1" suppliers, that is to say, they deliver directly to the car manufacturers. In some instances, however, they are "tier 2" (sub-supplier) only. Such a situation occurs for instance when carglass is supplied to an encapsulator such as […], or when it is supplied to a manufacturer of sunroofs, such as […] or […]. Whenever the carglass manufacturer acts as a "tier 2" supplier, it is not involved in negotiations about the price of the glass, which occur always between the "tier 1" supplier and the car manufacturer.

2.3.2. Demand

(29) The EEA is the only region where all the world’s major car manufactures have a production facility, including the major Japanese and Korean groups. The demand side is less concentrated than the supply side, although several mergers and alliances have led to an increase in concentration of the demand for carglass. During the period referred to in this Decision the four largest vehicle manufacturers accounted for more than 60% and the six largest for more than 80% of the production of light vehicles in the EEA. The major groups of car manufacturers with European production were negotiating the supply of carglass usually centrally for all own and affiliated brands and are listed by decreasing order of market share: Volkswagen (brands VW, Audi, Skoda, Seat and Bentley), PSA (Peugeot and Citroën), Renault (Renault, Dacia), Ford (Ford, Volvo, Jaguar and Land Rover), General Motors (Opel, Saab, Chevrolet and Vauxhall), Fiat (Fiat, Lancia, Alfa Romeo and Iveco), DaimlerChrysler (Mercedes, Chrysler, Smart and Mitsubishi), BMW and Nissan.22 It has to be noted that GM and Fiat had a joint global purchasing from 2000 until at least 2005 and that Renault and Nissan operated a joint venture during the relevant period.23

(30) Many car models are produced in different versions. These versions are referred to as ‘body type’, for example, the 3-door, 5-door, estate. Almost all car manufacturers have internal code names to be able to distinguish not only car models which have borne the same name for decades such as the BMW series 3 or the Volkswagen Golf, but also to distinguish the various body types of a certain model. These code names usually consist of a capital letter and numbers. Whenever appropriate this Decision refers to both the code name and the name under which a certain model is marketed.

(31) In relation to privacy glass, this category of dark tinted glass is an option frequently included in the request for quotation from car manufacturers. It is important that all the glass of a car is harmonious in appearance (colour and darkness). As a result, car manufacturers will generally select a particular glass type for the privacy glass option.

(32) The basic driver of demand for carglass is the number of vehicles built. However, there is an additional driver, which is the amount of glass used per vehicle. Moreover, due to styling trends, the glazing has become more complex. Although carglass is made from flat glass, it is rarely flat. Instead, most glazing for cars is curved, in particular the windscreen. The glazing can be bent in one direction or even two which makes it a complex piece of carglass. All these factors have contributed to an increasing market value during the period under investigation.

2.3.3. The geographic scope

(33) Carglass can and does travel significant distances. In terms of competitive conditions the OE market is homogenous at EEA level. Car manufacturers have centralised their purchasing decisions at headquarter level and negotiate EEA-wide deals. For example, the Volkswagen group decides on purchasing also for its Spanish subsidiary SEAT. The suppliers of carglass have adapted to this development. Therefore, the OE carglass market is considered to be EEA-wide.

2.3.4. Industry figures and shares

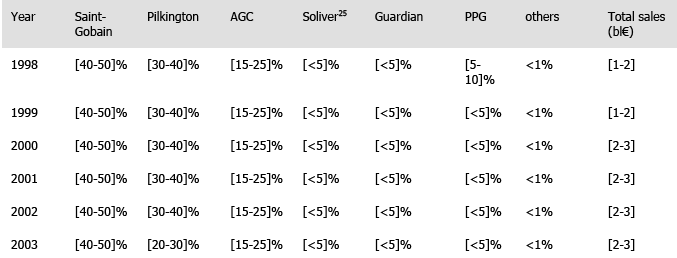

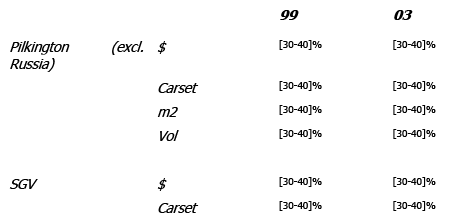

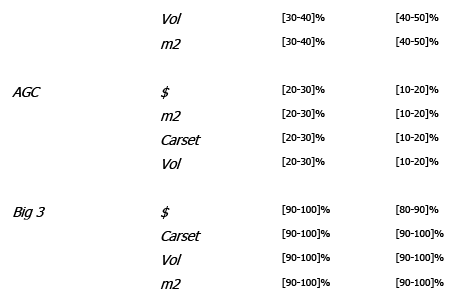

(34) There are only three glass groups with global automotive glazing capability and presence. Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and AGC account for [70-80] of the world’s OE glazing requirements. Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and AGC are also the main suppliers of OE glass parts for new passenger vehicles in the EEA, jointly accounting for more than 90% of all deliveries. Estimated EEA shares of carglass sales for the years 1998 to 2003 for passenger cars and light commercial vehicles (below 3.5 tonnes) in respect to the main OE players are set out in Table 1:24

NB: Source: Commission’s own estimates based on the parties’ replies to the Article 18 letters of 26 January 2006 (answers to question 11 in combination with question 13, see replies p. 14180 (Saint- Gobain), 14453 (Pilkington), 13550 (AGC) , 13104 (Soliver). Note that the significant increase of AGC’s market shares in 1999 is the result of the merger between AGC and PPG’s operations in Europe. Note also that the decrease of Pilkington’s share in 2003 is attributable mainly to a decrease of the relative value of the pound sterling against the euro and does not imply any substantial change in volume terms.

(35) The EEA leader in the carglass sector is Saint-Gobain with a share of sales of between […]% and […]%, followed by Pilkington with a share of between […]% and […]%. AGC had a share of between […]% and […]% in the relevant period. However, there was a structural change in 1998 when Glaverbel acquired the European activities of PPG. Therefore, taking account of this acquisition, it can be seen from Table 1 that shares of sales were remarkably stable during the period with which this Decision is concerned.

2.4. Trade between Member States

(36) Carglass production is concentrated in a certain number of sites located in various European countries. During the reference period the producers sold their products within the EEA directly to end users,that is to say, the car manufacturers, through a network of subsidiaries.

(37) Therefore, during the period 1998 to 2003, there were important trade flows in the EEA and, accordingly, a substantial volume of trade between Member States and the EFTA States which are Contracting Parties to the EEA Agreement as regards carglass.

3. PROCEDURE

3.1. The Commission’s investigation

(38) By letter of 7 October 200326, the Commission received information from a German lawyer, acting on behalf of an unidentified client, that carglass manufacturers had put in place certain agreements and concerted practices with a view to exchanging price and other sensitive information and allocating carglass supplies between each other for certain vehicle manufacturers and car models. Following contacts with the Commission, the informant provided additional information by letter of 10 March 2004.27

(39) On 22 and 23 February 2005, the Commission carried out inspections in Belgium, Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Italy at the premises of Saint-Gobain, Pilkington, AGC and Soliver. On 15 March 2005, the Commission carried out a second round of inspections in France, Germany and the United Kingdom at the premises of Saint-Gobain [and] Pilkington […].

(40) On 26 January 2006, the Commission sent requests for information under Article 18 of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003, hereinafter "Article 18 requests for information", to the following glass manufacturers: AGC, Glaverbel, Guardian, PPG, Pilkington, Saint-Gobain, Soliver as well as to the trade association Groupement européen de producteurs de verre plat, ("GEPVP").28

(41) The companies and GEPVP responded to those requests for information by letters dated 10 February 2006 (Soliver)29, 15 February 2006 (Guardian)30, 17 February 2006 (AGC Automotive and Glaverbel)31, 21 February 2006 (PPG), 24 February 2006 (Pilkington)32, 24 February 2006 (Saint- Gobain)33 and 27 February 2006 (GEPVP)34.

(42) On 7 February 2006, the Commission sent Article 18 requests for information to the following car manufacturers: […].35

(43) The car manufacturers responded to those requests for information by letters dated 24 February 2006 ([…])36, 8 March 2006 ([…])37, 3 March 2006 ([…])38, 24 February 2006 ([…])39, 29 and 30 March 2006 ([…])40, 3 March 2006 ([…])41, 23 February 2006 ([…])42, 13 March 2006 ([…])43, 10 March 2006 ([…])44, 9 March 2006 ([…])45, 4 April 2006 ([…])46, 25 April 2006 ([…])47, 3 March 2006 ([…])48 and 3 March 2006 ([…])49.

(44) On 3 March 2006, the Commission sent an Article 18 request for information to […]. […] responded to this request for information by letter dated 16 March 2006.50

(45) On 7 April 2006, the Commission sent Article 18 requests for information to AGC Automotive, Glaverbel, Pilkington and to two trade associations, the Fédération des chambres syndicales de l'industrie du verre ("FIV") and the Associazione Nazionale degli Industriali del Vetro ("Assovetro").51

(46) The companies and the two associations responded to those requests for information by letters dated 19 May 2006 (AGC Automotive and Glaverbel)52 and 30 May 2006 (Pilkington)53; 26 April 2006 (Assovetro) 54 and 3 May 2006 (FIV)55

(47) On 5 May 2006, the Commission sent an Article 18 request for information to Soliver.56 The company responded by letter dated 23 June 2006.57 The same day an additional Article 18 request for information was sent to Pilkington. This company responded by letter dated 30 May 2006.58

(48) On 8 May 2006, the Commission sent an Article 18 request for information to Saint-Gobain.59 The company responded by letter dated 16 June 2006.60

(49) On 13 September 2006, the Commission sent Article 18 requests for information letters to Saint-Gobain, Pilkington, Glaverbel and Asahi.61 The companies responded by letters dated 22 September 2006 (Pilkington)62, 6 October 2006 (Saint-Gobain)63 and 13 October 2006 (Glaverbel and Asahi)64.

(50) On 3 October 2006, the Commission sent an additional Article 18 request for information to Pilkington.65 The company responded by letter dated 13 October 2006. On 15 and 26 January 2007, the Commission sent Article 18 requests for information to AGC Automotive to which the company responded by letters dated 19 January 2007 and 2 February 2007. On 22 and 23 February 2007 the Commission sent additional questions to AGC Automotive to which it responded by two separate e-mails on 27 February 2007. The Commission moreover sent an Article 18 request for information to Pilkington on 15 January 2007. The company replied by letter dated 19 January 2007. The Commission finally sent additional Article 18 requests for information to Saint-Gobain on 26 and 31 January 2007 to which the company responded by letter dated 2 February 2007.66

(51) On 18 April 2007, the Commission initiated proceedings in this case and adopted a Statement of Objections subsequently notified to the addressees of this Decision.

(52) The addressees were granted access to the Commission’s investigation file by means of a DVD, sent shortly after the Statement of Objections, which contained accessible material in the file. Regarding the oral corporate statements, the parties were given the opportunity to listen to the recordings and to read the transcripts at the Commission’s premises. In the period following the access to file (from end of April to beginning of July 2007), the Commission sent additional documents to which access could be granted, which related to the file labelled 135 and question 9 of […] Article 18 responses. Moreover, the Commission sent by CD-ROM certain documents which had subsequently been revised by Pilkington as well as certain other documents labelled EFL3, SJ2, CC2, and CC3.

(53) The parties having made known in writing their views on the Statement of Objections, all the addressees of this Decision attended the oral hearing, which was held on 24 September 2007. Following the hearing, Pilkington and Soliver sent further submissions to the Hearing Officer both dated 15 October 2007. The Hearing Officer responded by letters to the companies on 22 October 2007 (Pilkington) and on 26 October 2007 (Soliver). The Hearing Officer also forwarded Pilkington's submission to Glaverbel for its comments, if any, on 22 October 2007. Glaverbel chose not to provide any comments. Asahi submitted further observations on its own initiative on 22 November 2007, 20 December 2007, 6 February 2008 and 6 March 2008. Pilkington submitted further observations on its own initiative by letter dated 7 January 2008.

(54) On 21 November 2007 the Commission sent an additional document to Saint-Gobain for comments as it had subsequently been added to the Commission's file. Saint-Gobain provided its comments on this document on 26 November 2007.

(55) The essential elements of the parties' observations to the Statement of Objections are dealt with in the corresponding sections of this Decision as well as in section 4.5 of this Decision.

3.2. The leniency application

(56) Following the first inspections carried out as referred to in recital (39), on 24 February 2005 and on 9 March 2005 respectively, Glaverbel and Asahi Glass Co. Ltd, and their subsidiaries, (hereafter collectively referred to as the "leniency applicant"), submitted an application for immunity or alternatively reduction of fines under the Commission notice on immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases67 (hereafter the "Leniency Notice"), […].

(57)[…].68

(58) On 19 July 2006, the Commission rejected conditional immunity from fines for the application made on 24 February 2005 in relation to OEM on the basis that the application did not meet the conditions set out in point 8(a) or 8(b) of the Leniency Notice.

(59) On 20 July 2006, the leniency applicant was notified of the rejection of conditional immunity from fines at the Commission’s premises.69 Pursuant to point 26 of the Leniency Notice, the applicant was informed that the Commission intended to apply a reduction of 30 to 50% of the fine which would otherwise have been imposed.

4. DESCRIPTION OF THE EVENTS

4.1. Background

4.1.1. The procurement of carglass by car manufacturers

4.1.1.1. Bidding process - Requests for quotation

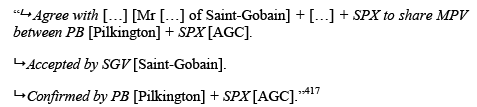

(60) The procurement by car manufacturers of glass parts for a specific car model is carried out through a bidding process. The car manufacturers invite carglass suppliers to quote for the development, production and supply of glass parts for a new model or a new body type of an existing model. As a first step it is customary for the car manufacturer to send out a request for quotation (hereafter “RFQ”) to the carglass suppliers. An RFQ includes drawings, design and technical feasibility specifications, the target prices on a per glass piece basis which the car manufacturer expects to be met as well as estimates of the volume to be produced over the life time of the new vehicle. It also contains other information on the basis of which the glass manufacturer has to make an offer such as the car manufacturer's general terms and conditions as well as requirements in terms of production and logistics flow. Acceptance of these terms and conditions is a pre- condition to the carglass supplier's participation in the RFQ process. The RFQ often includes a table asking for a detailed cost breakdown of the price (in French it reads “décomposition de prix”) quoted for each of the glass parts under tender, including development and tooling costs and also a detailed breakdown of the productivity gains. The detailed cost break- downs which are used by the car manufacturers to justify the price quote more particularly consists of not only the price quote but also all the cost elements in relation to pre-assembly with other components (e.g. antenna, sensors), encapsulation or extrusion, transportation and packaging.70 Price supplements for dark tinted glass requested by the car manufacturer such as Venus, Sundym or Athergreen are also set out in the RFQ.71 The productivity gains are expected to be passed on to the car manufacturer as yearly discounts. The RFQ can be seen as a questionnaire which will show whether the glass producer has the capacity and technology available to submit an offer for the glass piece in question.

(61) The offer documents are normally sent to car manufacturers two to four weeks after the RFQ has been issued.72 They include the price for the development, the tooling costs for the first prototype, the price for prototype pieces, the price per piece during series production as well as productivity gains. The discounts offered on the basis of productivity gains are also referred to as lifetime or "long-life" conditions.73 The costs of the first prototype can also be included in the series price. In the event that all these costs have to be borne by the glassmaker, who also takes full liability for the development of the glazing, the industry speaks of “Full service supply (FSS)”.74 Subsequent negotiations can last between a couple of weeks and 12 months. If the car manufacturer agrees with the proposal submitted by a certain carglass producer, the car manufacturer informs such a producer that it has been retained as the supplier for the part in question by sending a nomination letter.75

(62) There are three nomination possibilities. The simplest way would be to nominate just one carglass supplier for the entire set of glass for the model in question. This is referred to as single sourcing. Alternatively, the car manufacturer splits the car set between two or more glass suppliers by allocating for instance the windscreen to one supplier, the backlight to a second supplier and the sidelights to yet another one. Lastly, it also happens that, in particular for volume car models, the car manufacturer selects two or more suppliers for the same piece referred to as dual or multiple sourcing. In all scenarios the car manufacturer does not commit itself to purchase a certain number of glass pieces but rather to a percentage figure of actual production of the model, that is to say, a contract for 60% of the glazing needs. The choice of single, dual or multi sourcing strategy is based on physical and financial reasons. Firstly, in order to ensure a continuous production and logistics flows, some car manufacturers find it useful to appoint a second supplier, for instance in case there is a shortage of supply (for example because of strike or accident) at the plant of the first supplier. The affected supplier will then inform the car manufacturer of such delays or shortages in the delivery of parts. The car manufacturer will then require the second supplier to increase its output and deliveries in order to step in and avoid any disruption at the assembly lines of the car maker (no contract is entered into between the first supplier and the car manufacturer for the deliveries that the second supplier makes at the request of the first supplier). Secondly, some car manufacturers will work with several suppliers (the case of French car manufacturers) to benefit from the competitive process and to obtain the lowest possible prices.76

(63) The decision for a car manufacturer on whether the basis in the RFQ and in the end for the nomination is individual parts, carsets or subsets depends on their respective component strategies. It can be generally said that it is done on a case-by-case basis whilst taking into account factors such as pricing aspects and technical as well as quality requirements.

(64) Decisive elements for a choice of a supplier are for instance the lowest total of the series price, tooling costs, development costs, prototype costs, packaging charges and cost for quality management and logistics, all parameters calculated over life-time (from start of development to end of series production), as well as compliance with the procurement strategy of the car manufacturer and the technical and quality requirements.77 Other factors that determine the sourcing decision are whether the target price is met and the lowest lifetime amounts for piece, tooling, and development costs to be spent.78 It can generally be concluded that the choice is based on the overall economic assessment through a comparison of the part price, tooling costs and net present value taking into account the productivity proposals from the suppliers. According to Saint-Gobain, the main elements of the offer are price quotes, development costs, savings/discounts on current business, productivity discounts and technical specifications.79

(65) After the selection phase ending with the nomination letter the development phase begins. Development can take between 10 months and three years,80 depending on the complexity of the glazing part. During this phase the initial design and specifications are often modified. Since each glass part is produced on dedicated tools and equipment, specific tools will have to be constructed for a new glass part. The development phase includes the production of prototypes and initial samples.

(66) Once the development phase is completed the mass production and supply phase begins. The volume ordered by the car manufacturer usually includes a certain percentage which is not meant for first assembly of the cars but for replacement. The average duration of a supply agreement depends on the car manufacturer in question.81 In some instances the car manufacturer opts for a lifetime contract for the whole life cycle of the car. These contracts have typically a supply period of 5 to 7 years or longer, while there are also yearly contracts which allow the car manufacturer to renegotiate every year and change supplier if better conditions are offered.82 For example, […] usually engages in contracts for the entire life cycle of the vehicle.83

4.1.1.2. Car manufacturers’ sourcing strategy during production

(67) During the production of a vehicle it is not uncommon that the volume supplied by the nominated glass manufacturer(s) changes to take account of the actual evolution of the sales of the car model concerned or that a new supplier is selected by the car manufacturer either as a second supplier or in replacement of the initial one. In cases of multiple sourcing the car manufacturer may gradually increase the volume purchased from the second supplier of a certain glass piece at the expense of the first supplier, in particular if quality requirements or requested price reductions are not met.84 Know-how and patents are generally not seen as an obstacle to the selection of a second supplier.85 It is possible for any experienced glass producer to reproduce any existing glass piece.86

(68) In the quotation documents there is usually also an item “After sales price”, which is then taken up in the nomination letter.87 Over the life cycle of a car model an additional 5-10% volume of the total OE order is earmarked for replacement.88 The price for those pieces which are not for first assembly but for replacement is normally the same as for first assembly, with the exception of a supplement for the individual packaging and the ensuing different logistics.89 Car manufacturers have developed order systems for replacement glass which are based on the number of cars on the roads and a percentage based on past experience of damages to the glass which allows them to order the right quantity on a regular basis.90 Towards the end of the production of a vehicle the car manufacturer aims at having a sufficient stock of replacement glass for, in the case of […], at least 15 years.91

4.1.2. Licensing, cross supply agreements and other commercial relationships between carglass suppliers

(69) There are a number of commercial relationships between the suppliers of carglass. These relationships concern licensing as well as cross-supply agreements between the major suppliers of carglass. For instance, Saint- Gobain has out-licensed some of its technologies to competitors in essentially three domains: acoustic glazing for noise reduction, extrusion technology to glue the glass directly onto the car and double bending for complex glass shapes.92

(70) Pilkington and Saint-Gobain are joint venture partners for the production of flat glass to be processed into carglass in Italy (Flovetro); another joint venture for the production of flat glass for use in carglass plants exists between Pilkington and Glaverbel in Spain (GlaPilk).93

(71) Apart from these joint ventures there are also cross supplies between the competitors for specific raw glasses, in particular dark tinted glass, and often on a reciprocal basis. For instance, Saint-Gobain has supplied the other major glassmakers with its dark tinted glass ‘Venus’, while Pilkington has supplied the others with its own dark tinted glass ‘Sundym’. According to the glassmakers these cross supplies have often been necessary to meet the specifications requested by the car manufacturer.94 Another reason for these swap arrangements is to enable the glass manufacturer to dedicate a float glass line to either clear or tinted glass and thus avoid the losses due to the transition time from tint to clear.95

(72) On occasion, where the production volumes required for a certain glass part is too low to be commercially attractive, glass manufacturers subcontract the production to other glass suppliers.96

(73) Spot commercial relationships also exist as another regularly occurring supply relationship whereby certain carglass parts are sold to competitors on a spot basis. These spot deliveries are agreed among competitors in times of shortages where there is a production problem or a strike. Such arrangements are often referred to as “dépannage”.97

4.1.3. Market share estimates by the market players subject to the proceeding

4.1.3.1. Sources of data on output and sales of vehicles in the EEA used by carglass suppliers

(74) Due to almost perfect transparency as to the actual sales of motor vehicles by each individual car manufacturer, the carglass suppliers are able to calculate their respective market shares within the EEA in a very accurate manner. The carglass suppliers obtain this data from national automotive federations98, international automotive news services99, automotive forecasters (for detailed market and production research)100 and other sources such as motor shows, daily press, automotive reviews and photographic data bases (for example Autovision). Detailed information is obtained on a subscription basis, being purchased from specialised information services. The industry databases (such as J.D. Power) primarily purchased by carglass suppliers provide vehicle production volumes, broken down by model, body type and assembly plant level, and cover both production history and forecast data. These data are regularly checked against other forecasts which the suppliers obtain from other database sources (such as CMS).101

(75) The suppliers moreover receive data from the car manufacturers as follows: statistics on the car manufacturers’ glass-part-demand requirements forecast three months ahead102; statistics on each car manufacturer’s output on a model-by-model basis provided on a monthly basis for the previous month103; medium term demand forecast (around 12 months ahead) showing vehicle build numbers or specific demand forecasts; long term forecasts which include an estimated production for a period of two or three years104; and information as to future demand via RFQs105 and informal dialogue with the car manufacturers in the context of on-going commercial and technical contacts with the car manufacturers in relation to existing and future supply contracts. These sources are generally used by market players to estimate market share to take account of models for which one or another supplier is not supplying glass. In addition, the competitor situation is very transparent because there are few players on the market.106

4.1.3.2. Methods used by carglass suppliers to track market shares

(76) Several documents copied by the Commission at the premises of AGC, Saint-Gobain and Pilkington relate to market share data gathered by the companies' marketing departments and by the key account managers in charge of a particular customer/car account. The information in question is provided by car manufacturers in the context of commercial contacts or on the occasion of physical deliveries of glass parts to the assembly line of the car manufacturer or from publicly available sources such as JD Power (see section 4.1.3.1). In order to track their respective market shares in the industry, the suppliers use two alternative ways, by reference either to the value of sales (in euros) or to the volume (by “carsets”, parts of carsets, square metres or glass pieces). The suppliers have described in the Article 18 responses how they each measured market share estimates for the period in question.

(77) Until 2004, Saint-Gobain used […]107.108

(78) AGC tracks market shares by reference to the value of sales and by volume using parts of carsets as the counting measure. Regarding the value approach, a carset is generally considered to comprise one windscreen, one backlight and six sidelights. The number of the sidelights used varies according to the model, for example 3-door, 5-door and also evolves over time, as models evolve. In order to compile data AGC first uses the JD Power or CSM (from 2003 onwards) reports on car production volumes in order to determine the number of cars produced on a model-by-model basis. AGC counts one carset per car model. The number of glass pieces used in that model and the identity of the supplier would be checked by visiting motor shows, for contracts under supply, as the name of the supplier is always marked on the glass piece. AGC then uses their own average market price per family of parts (per carset, that is the windscreen, sidelights and backlights) per car manufacturer to calculate turnover. As regards AGC’s estimates by reference to volume (by glass piece), the number of pieces for cars under production is known. Total volumes can therefore be calculated by multiplying the total number of cars produced (from LMC/CSM) by the number of pieces per car model. For future vehicles, AGC would generally assume that they would have the same number of pieces as the old model and that contracts would be supplied in the same way.109

(79) Pilkington measures market shares by reference to revenue or value, which entails an estimation of the size of the total market in value (euros) by using as a benchmark its own prices for each glass part that it supplies to car manufacturers.110 However, documents in the Commission’s file show that, in addition to value and contrary to what is stated in Pilkington’s Article 18 response, it also calculated market shares by reference to volume (by carset and by glass piece).111 In this respect, it is furthermore noted that Pilkington used JD Power reports to collect the relevant data, despite its statement to the contrary in its Article 18 response.112

(80) Soliver has not provided any detailed information on how it estimates market shares. It only stated that information is generally received through contacts with car manufacturers.113

(81) In sum, referring to volume, it can be concluded that market share data is tracked as follows for cars in production: the number of parts will be deduced by multiplying the number of cars produced by the number of parts per year (information obtained from customers and from publicly available sources) and, for future car models; the RFQ predicts the yearly production/number of parts per car for cars not yet in production. The conversion of data from glass pieces into square metres is feasible and the contrary is also possible albeit less precise. Theoretically, a conversion from the square metres into glass pieces and value can be done by relying on the average surface of a glass piece and by assigning an average value by square metre.114 Referring to value, own prices are used as a benchmark in order to estimate the size of the total market value.

(82) The three major competitors have in their Article 18 responses provided an explanation of how they generally measure market shares of competing suppliers for existing and future models.

(83) During the period of the infringement Saint-Gobain […].115

(84) AGC measures the turnover of the other suppliers on the basis of the average price per carset. The average selling price of AGC is extrapolated and used as the basis for calculation of the turnover for other competitors.116 A document from the premises of Glaverbel, dated 8 July 1996, illustrates how AGC at the time calculated market shares for competitors by reference to number of pieces produced for a production line.117

(85) Using its own supply value as the starting point, Pilkington gathers details of supply by other suppliers through its […] who know who has been awarded that business which Pilkington has not won.118 This information is, according to Pilkington, based on discussions the […] have with the purchasing or engineering departments at the vehicle manufacturers.119 In addition, Pilkington uses public or third party data sources.120

(86) Tracking on the basis of information provided by car manufacturers or other public or third party data sources apart, the Commission has evidence which illustrates that the three competitors exchanged information about their respective market shares amongst themselves and compared their respective estimates in connection with the on-going coordination for the purposes of allocating of carglass supplies, as will be shown in sections 4.3 and 4.4.121

4.2. Organisation of the cartel

4.2.1. Trilateral, bilateral meetings and other contacts

(87) Pilkington, Saint-Gobain and AGC participated in trilateral meetings which were referred to as “club” meetings.122 These three competitors are sometimes referred to in certain documents in the Commission’s file as the “Big three”,123 a term that will also be used in the following sections of this Decision. The […] normally attended such meetings often accompanied by the […] being used by the participants in the meetings. These meetings were […] organised by telephone and were mostly initiated by Saint- Gobain. These so called “club” meetings had no chairman or secretary and the organisation was a rolling process between the three competitors, Saint- Gobain, Pilkington and AGC.124

(88) The competitors also met bilaterally to discuss ongoing as well as new models to be launched. These bilateral meetings and contacts between Saint-Gobain/Pilkington, AGC/Saint-Gobain and AGC/Pilkington related to issues similar to those discussed during the trilateral meetings, in particular the evaluation and monitoring of market shares, the allocation of carglass supplies to car manufacturers, the exchange of price information as well as other commercially sensitive information and the coordination of their respective pricing and supply strategies. In addition, numerous telephone contacts occurred between the competitors.

(89) Although Soliver was not party to the arrangements prior to November 2001, […].125 The Big three could exploit the fact that Soliver lacked in- house production of the raw material, flat glass, which made it dependent on the three leading suppliers. Saint-Gobain, as Soliver's most important supplier, had a privileged communication channel and was in the end successful in persuading Soliver to adhere to the Big three's common plan.126 According to […] documents in the file, Mr […] and Mr […] of Saint-Gobain regularly met and/or had contacts with Messrs […] of Soliver.127 Soliver supplied products mainly to Fiat and VW. Mr […] and Mr […] of Saint-Gobain were in charge of those […] customers and the purpose of the contacts was mainly to share the supply of carglass parts for the Fiat and VW accounts. Soliver started to participate directly in the unlawful activities as of 19 November 2001 (contacts with AGC). Soliver met bilaterally with Saint-Gobain and AGC until 11 March 2003.128

4.2.2. Location of meetings

(90) The Big three met for trilateral meetings in hotels in various cities (for example, the Brussels Airport Arabella Sheraton hotel, in Niederhausen, near Frankfurt, in Paris at the Regency Hotel, the Charles de Gaulle Airport Hyatt or Sheraton hotels) and once at the Arabella Hotel in Düsseldorf, Germany. The competitors moreover met at the premises of GEPVP, where they sometimes organised meetings on the fringe of the official GEPVP meetings, over lunch. They also met at the Rome Fiumicino Airport hotel and at the premises of the glass association in Rome, the Assovetro. Finally, the competitors met in Paris at the premises of the FIV, the Fédération du verre, and in the apartment of Mr […] of Pilkington in the 16th district in Paris as well as in Mr […] country house in the north of

France.129

(91) The GEPVP, an independent European trade association in the flat glass industry, was founded in 1978.130 GEPVP is made up of 14 companies in 11 Member States, all of which are leading glass producers, including Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and AGC. GEPVP was not involved in the arrangements or in the organisation of any meetings which are referred to in this Decision and which took place on the fringe of the official GEPVP meetings. The members of the GEPVP were normally, from Glaverbel, […], from Pilkington, Mr […] and Mr […] and, from Saint-Gobain, Mr […].131

4.2.3. Frequency of meetings

(92) […]. In March 1998, there was a meeting at which the contacts between the two competitors went beyond the purely technical as they discussed end prices for a carglass piece. From […] spring 1998 to the second half of 2002 there were regular trilateral Club meetings between AGC, Saint- Gobain and Pilkington every few weeks and sometimes more frequently as well as bilateral meetings and other contacts. From January to March 2003, there were bilateral meetings and/or contacts between Saint-Gobain and AGC, and AGC and Soliver.132

4.2.4. Participants

(93) The commercial departments of the suppliers are responsible for handling the RFQs and the subsequent negotiations with the car manufacturers. The persons concerned within Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and AGC are at […] levels: […].133 […].

Saint-Gobain

(94) As regards the organisational internal structure of Saint-Gobain, […]134135136.

Pilkington

(95) As explained in recital (93), the organisational internal structure of Pilkington has consisted since 1996 of […].137 From 1999 to 2002 as well as from 2003 onwards the decision making processes changed whilst […].138

AGC

(96)[…]139140.141

(97) Participants in the meetings and/or contacts were company employees participating on behalf of AGC, Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and Soliver as follows142:

– AGC: Messrs […]143.

– Saint-Gobain: Messrs […]144145146.147

– Pilkington: Messrs […].

– Soliver: Messrs […]148.

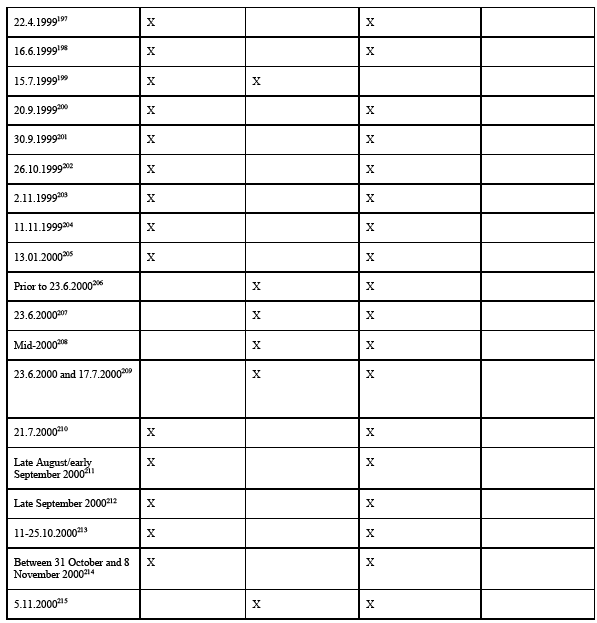

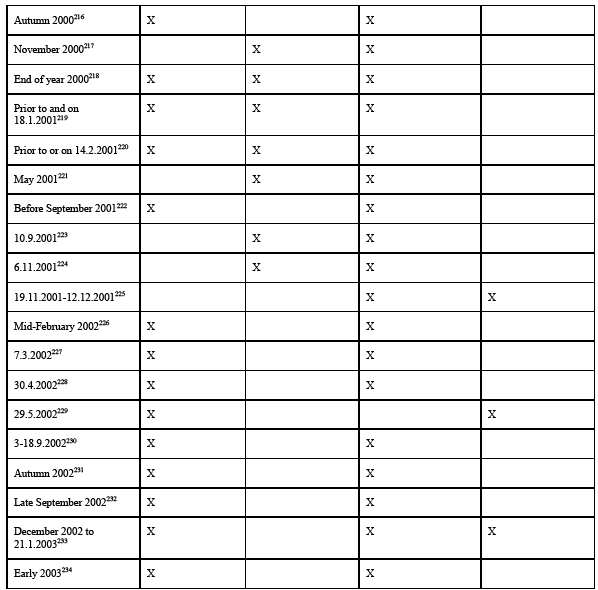

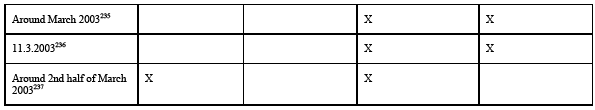

4.2.5. Overview of the meetings and contacts from 1998 to 2003

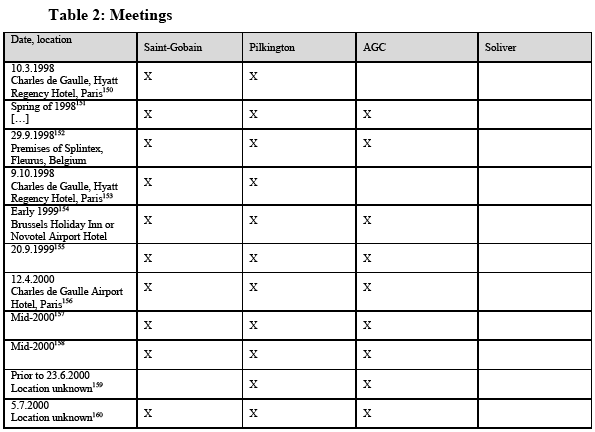

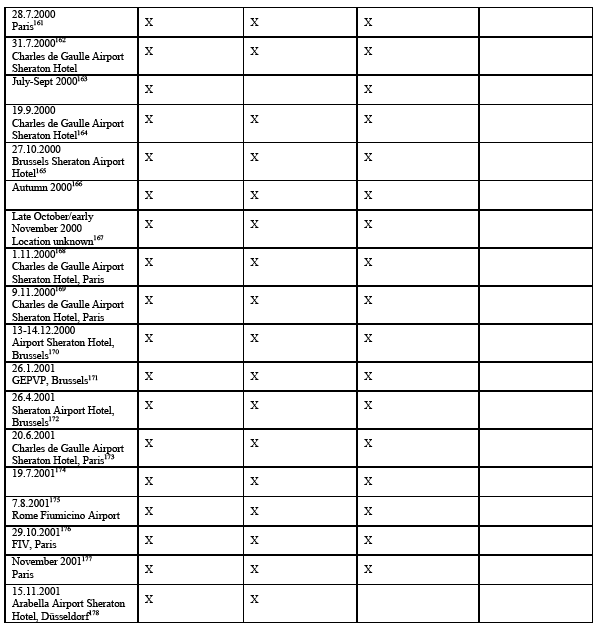

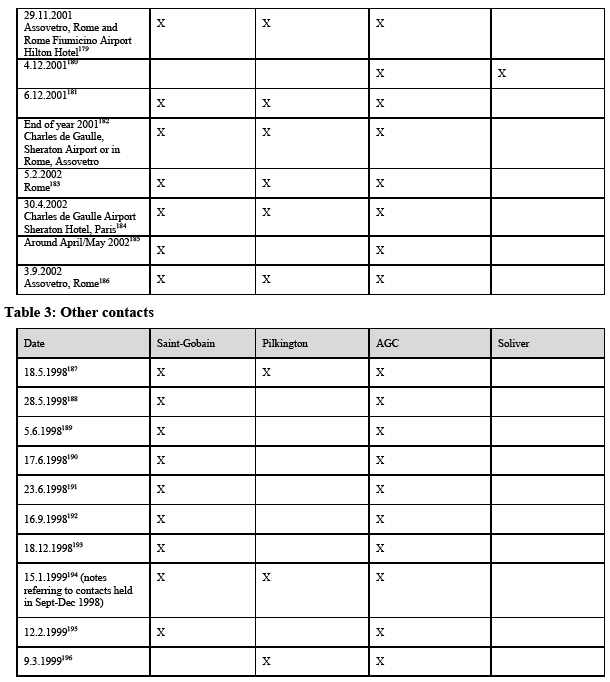

(98) Tables 2 and 3 set out an overview of the meetings and contacts of competitors for which the Commission has evidence of the dates, location and participants. Table 2 contains a list of meetings either trilateral (Saint- Gobain, Pilkington, AGC) or bilateral (Saint-Gobain/Pilkington, Saint- Gobain/AGC, Pilkington/AGC or Soliver/AGC). Table 3 sets out an overview of other contacts (mainly telephone calls, fax transmissions and e-mail correspondence) that occurred between the competitors mostly bilaterally. The participants used either abbreviations or code names when referring to each other at meetings and contacts.149

4.3. Object and functioning of the cartel

(99) The overall plan of the cartel was to allocate supplies of carglass whilst keeping market shares stable. Therefore, the purpose of the meetings and other contacts mentioned in section 4.2.5 was to allocate new and reallocate existing supply contracts for car models among the four participating carglass manufacturers which accounted for more […] of the European sales of carglass. The documents in the Commission’s file, which will be referred to in detail in this section and, more specifically, in section 4.4, show that, in order to allocate these contracts, the glass manufacturers exchanged price and other sensitive information and coordinated their pricing and supply policies, which allowed them to take concerted decisions regarding their response to RFQs issued by car manufacturers and to influence, to a large extent, the choice of the supplier, or in case of multiple sourcing, the suppliers for any given contract or any given carsets or carglass pieces. It was the suppliers’ intention to maintain a certain overall stability of their respective market positions for the purposes of the allocation of carglass pieces to be supplied to car manufacturers. The suppliers therefore closely monitored their market shares individually and jointly in relation to the actual supply as well as the future supply for various models not only per vehicle account but also globally (all vehicle accounts together) and, when necessary, correcting measures made sure that on balance the overall supply situation at the EEA level was in line with the envisaged allocation.

4.3.1. Allocation of customers

(100) The Commission has evidence that, from […] March 1998 until March 2003, AGC (as from May 1998), Saint-Gobain and Pilkington (this latter until September 2002) shared customers by allocating the demand from car manufacturers of carglass parts for new cars and existing cars for which production was ongoing as well as for OE replacement.238 Soliver’s participation can be established as from November 2001 until March 2003. During the period concerned, Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and AGC had a joint leading role on the market, which is reflected by the designation “The Club” which can be found in several documents in the Commission’s possession. As regards Soliver, it had bilateral contacts with both Saint- Gobain and AGC during the period in question relating to allocation of carglass pieces (see section 4.2.5).

(101) In essence, at these meetings and contacts the competitors exchanged information for one or more vehicle accounts or specific carglass pieces and often more than one customer or vehicle account for both existing and future models were discussed. The Commission is able to prove that in at least 15 trilateral meetings, the competitors had discussionscovering various accounts, in particular from 2000 to 2002.239

(102) As will be explained in detail in section 4.4, when the car manufacturers requested the suppliers to quote, the suppliers regularly co-ordinated their replies to RFQs for contracts coming onto the market and discussed who should win these contracts or which glass parts should be won by whom. Each supplier was interested in securing the supply contracts it wanted most and would compromise over contracts it wanted less. Sometimes certain carglass parts or pieces were better for one supplier based on how much free production capacity it had or on low transport costs for instance.240 They moreover coordinated their replies whencar manufacturers put parts out for re-quotation or when car manufacturers re- negotiated the price for certain parts during the life cycle of a vehicle. The suppliers had basically two means to “preselect” the winner: either by not quoting at all, or by quoting higher prices than the agreed winner. The first mechanism required not participating in a bidding process for a supply contract concerning a car set (all carglass pieces for one model) or specific carglass pieces for a particular vehicle depending on the car manufacturer's requests in the RFQ, for instance by claiming that no capacity was available. The competitors also used this mechanism to attempt to preserve an existing dual or multi sourcing for a given piece. In particular, in order to make sure that the car manufacturer would continue to dual source from the competitors concerned, the competitors agreed to inform the car manufacturer that none of them had sufficient capacity to take on 100% of the order so as to keep stable each competitor’s market position (see for instance recitals (188), (189), (244) and (378)).241

(103) The second, more sophisticated mechanism used to allocate supply contracts concerning car sets or specific carglass pieces consisted in letting the “pre-selected” winner set a price in response to specific RFQs, with the other competitors agreeing to quote higher prices. In other words, once the winner was agreed, that competitor would inform the others of its proposed prices either at the same meeting or thereafter, while the other carglass suppliers would agree to make their offers above this price. This mechanism was referred to by the competitors as “covering” each other.242 When car manufacturers changed their suppliers, the aim of the suppliers was to manage these shifts by realigning supplies through further contract reallocation in order to keep stable their existing market positions.243

(104) In order to keep the allocation of contracts as agreed it was also necessary to manage price increases or demands for price decreases which would otherwise lead to a disruption of the envisaged allocation. Carglass manufacturers often have to commit to an annual reduction of the price in line with productivity gains which is an integral part of the offer. Consequently, the main suppliers agreed on productivity related price discounts vis-à-vis certain car manufacturers. One illustrative example is represented by the discussion which took place in 1998 with a view to limiting to […] the additional annual price reduction resulting from productivity gains vis-à-vis Renault, to be applied for the years 1999 and 2000.244

(105) It was also not uncommon that car manufacturers tried to obtain additional price reductions during the production phase of a car model either directly or indirectly by shifting costs to the carglass supplier. For instance, car manufacturers requested their suppliers to apply the principle of Full Service Supply (FSS), also referred to as supply integration principle, which meant the transfer of the liability and cost of the development of glass to the glass suppliers.245 The carglass suppliers attempted to counter- act by coordinating their RFQ responses, such as agreeing on refusing to accept price reductions requested by car manufacturers or by agreeing not to accept additional services requested by car manufacturers without compensation. Lastly, in order not to provoke shifts in supply by the car manufacturers, the carglass suppliers also agreed on price increases vis-à- vis particular vehicle accounts or specific car sets/carglass pieces.246

(106) Furthermore, the three competitors, Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and AGC, coordinated their information disclosure policy to resist demands for price reductions from the car manufacturers. Car manufacturers generally request suppliers to give a full breakdown of their prices for the different components of the windscreens, sidelights and back lights which then form the basis for price reductions. As will be shown in section 4.4, the competitors exchanged information about which pricing elements they would be prepared to reveal to their customers.247 Similarly, they agreed to limit the disclosure of their production costs and other technical information obtained by car manufacturers through audits of suppliers’ facilities which would enable the car manufacturers to put downward pressure on prices.248 This kind of coordination was done in order to better manage the allocation or reallocation of carglass piecesbetween themselves.

(107) With regard to Soliver, it had direct contacts with Saint-Gobain249 and AGC250 from at least 19 November 2001 to 11 March 2003.

(108) Information at the Commission's disposal shows that […].251 […]. There is nevertheless one meeting between Pilkington and Saint-Gobain which relates to an exchange of end prices in connection with roof lights and this meeting therefore forms part of the overall arrangements between the three suppliers as described in section 4.4 (see recitals (122) to (125)). In particular, considering that dark tail/privacy glass (which constitutes a sub- category of tinted glass252), such as Venus, Sundym and Atherman, forms part of an RFQ and moreover was regularly discussed between the competitors at the trilateral and bilateral meetings and during the contacts, this meeting fits into the general arrangements which are described in more detail in section 4.4.

(109) The Commission furthermore notes that, as the privacy glass range of products of Saint-Gobain (Venus), Pilkington (Sundym) as well as of AGC (Atherman) forms part of the RFQ and constitutes a price supplement to be taken into account by the carglass suppliers when submitting their quotes (see also recital (60)), the three competitors included this factor among the other costs (such as tooling and development costs) when allocating or reallocating supply contracts between each other for the different vehicle accounts, in particular during the meetings and contacts that took place in the period 1998 to 2003.

4.3.2. Monitoring with a view to maintaining market shares stable

(110) The three competitors, Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and AGC constantly tracked very closely their respective market shares of the supply to customers. The Commission is aware that market share tracking and the tools used to do it can be perfectly legitimate. However, the three competitors went beyond their own legitimate market share tracking tools described in section 4.1.3.2 by using these tools in order to allocate contracts between themselves253. These mechanisms used to allocate supply contracts as set out in section 4.4 were put in place with a view to ensuring a certain overall stability of the parties’ market shares or, […], achieving a "market share freeze".254 Documents in the Commission's possession illustrate that the competitors indeed intended to keep market shares at least stable for the purposes of achieving balance in the allocation arrangements between them (see for instance recitals (177), (189) and (325)). Monitoring and correcting measures were the necessary complements when actual sales volumes and/or actual contract awards diverted from forecasted monitored market shares and/or agreed allocations/reallocations.

(111) On the basis of the documents in the Commission’s file it can be concluded that the competitors used both volume (by carset and glass piece) and value on the basis of forecasts produced by the competitors which served as a general basis for the exchanges in order to allocate or reallocate carglass parts during their meetings and contacts.255 Besides the global forecasts and more long-term overviews, the Big three used the week to week data provided by the […] to analyse the actual evolution of sales regarding individual car models.

(112) Considering that the RFQs contain the number of cars to be produced256 and taking into account the transparency of the market, the Big three could at their meetings calculate the pieces needed using one of the alternative approaches described in section 4.1.3.2.257 In practical terms the trilateral and bilateral meetings can be described as being similar to commercial negotiations at which each competitor intended to persuade the other of what it should obtain on the basis of the production volume foreseen in the RFQ. These negotiations should be seen in the light of the respective profitability analyses by the Big three. For any loss-making parts, the three competitors respectively either needed to stop producing these glass parts and switch production to more profitable activities or to increase the price of the carglass parts.258 There was therefore understandably a certain amount of compromise as to who would get which contract. The competitors therefore needed to apply certain correcting measures in situations where the initial plans of allocation did not work out in the end, including situations where the sales volume for a given car model deviated from the quantities initially forecasted. In particular, correcting measures were put in place to allow the competitors to compensate each other for losses occurred, thus maintaining the agreed market share stability. As can be seen from table 1 in section 2.3.4, the market shares of the competitors indeed remained stable from 1998 to 2003.

(113) In the period from 1998 until 2001, Saint-Gobain, Pilkington and AGC allocated (or intended to allocate) supply contracts without a specifically defined methodology as far as market share analysis was concerned. This gave rise to disputes during the allocation discussions as to who would be awarded what. Generally, the aim when allocating or reallocating glass parts for a particular account (and/or sometimes across accounts) was to leave unchanged the market share balance between the three competitors. As set out in section 4.1.3.2, the competitors measured each other’s shares by reference to volume (by reference to car set, car piece, and square metres) or value.259 Soliver adhered to this overall scheme at least as of 19 November 2001. During a meeting between the three major competitors, on 6 December 2001, the Big three refined what reference(s) they should use together (up to this date either a car set calculation (conversion possible into volume) or a value calculation had been used) and attempted to agree on a common methodology for the purposes of allocation and reallocation of carglass supply contracts – namely they decided on a new rule, since the previous one did not make sense anymore – for the allocation of carglass supply contracts up to 2004. The minutes of that meeting contain a table with forecast market shares of the Big three for 2004.260 It can also be concluded that the Big three agreed to refine the monitoring in relation to market share calculations as follows according to the minutes of […] as well as those of […], both of AGC: “3) Actions - to define what the MKT is up to 2004 - Describe clearly what is the reference

- It has no sense anymore to speak countries real issue is customer - to agree upon to discuss to decide a rule on new model up to 2004 - Do we have to consider share on remaining left part of the cake after new entry - Europe is defined as LMC [JD Power]”261.

(114) On the fringe of another GEPVP meeting on 10 July 2002 between the Big three, which can be seen as a follow up to the discussions between the Big three on 6 December 2001, a comparison of the market shares by reference to the alternative methods for calculating market shares (car set, square metres and volume) was made. The following overview covered the period 1999 to 2003 in value and volume (by car set and by glass piece):262

“- customer/customer

- all awarded business

(115) The market situation was monitored by the Big three and compared to what had been forecasted. For example, […], sent an internal email dated on 17 September 2002 to his Account Managers in order to establish the losses suffered by AGC during 2000-2002 and requesting that they inform him of all “business casualties” occurred for that period. The spreadsheet to be filled in by […] and specifies what the competitors “owes” to each other in terms of annual sales turnover.263 According to the e-mail, the commercial director wanted an overview of the situation between the Big three so as to assess the allocation of accounts between competitors, in other words assess what business had been “stolen from one player by another player”264. The Commission considers that this document confirms that a number of arrangements between the Big three to allocate contracts was in fact successful and hence implemented.

(116) As a consequence, the Big three also had a compensation mechanism, in order to correct the “casualties”, which will be further explained in section 4.3.3.

4.3.3. Correcting measures

(117) The allocation of contracts did not always work out in practice, either because the car manufacturer chose a supplier other than the designated one, or because the sales of a given car model was well below the expected volume or for other reasons such as single dual or multi-sourcing strategies applied by the car manufacturers (see section 4.1.1.1). This is the reason why the suppliers monitored each other and envisaged to compensate for these “business casualties” and “losses”. The type of compensation mechanism used by the suppliers in order to try to maintain their respective market shares can be described as follows: In exchange for one party’s failure to obtain part of the business of a certain vehicle account, the other parties would suggest a percentage of the business of another account or vice versa. This could be achieved by re-allocating an upcoming RFQ but also by fine-tuning through shifting the supply of existing models (for cars under production). It can moreover be seen from the documents in the Commission’s possession that proposed solutions were sometimes made during meetings to adjust for losses in order to try to ensure stability of their respective market shares.265 The suppliers adapted themselves to the sourcing strategies of the car manufacturers in the following way: In the case of multi-sourcing, the competitors attempted to agree to reduce the volume of supply of carglass parts to a certain customer for an existing model in favour of whichever of the three cartel participants needed to increase their market shares. In the case of single or dual supply, compensation was awarded on the basis of existing cars of the customers (mainly within the same account but sometimes even across accounts, for instance regarding Renault/Peugeot or Renault/Nissan).266

(118) The mechanism used by the competitors to fine-tune the market share balance is to claim vis-à-vis car manufacturers to have a technical problem or a shortage of raw material which will lead to a disruption of delivery of the contracted glass part (a so called “dépannage”). The supplier informs the car manufacturer that it will have to stop supply in the near future and suggests an alternative supplier. In the case of dual sourcing, this will almost certainly be the second supplier. Therefore, in cases where the second supplier is the one that needs compensation a shift of volumes can be relatively easily managed.267

(119) Examples of such compensations are set out in section 4.4.268 An illustrative example can be found in the notes taken by […] during a trilateral meeting in July 2000 (see recital (237)). As it transpired out that AGC had taken more volume than agreed on the Peugeot 106 and Citroen Saxo Saint-Gobain [X] and Pilkington [Y] claimed compensation as follows: “106/Saxo SPX [Splintex = AGC] has taken ≈ 100K W/S in 2000; X, Y are worried about this and may need compensation”.269 A further example is the new Toyota Avensis which was discussed in June 2000 (see recital (226)). It was agreed that “if new Avensis W/S is no split between SGV [Saint-Gobain] + PB [Pilkington] then SPX should give up something to SGV”.270 In other words AGC should compensate Saint-Gobain for not becoming a supplier of the new Avensis. Another example of compensation is illustrated in the handwritten notes of an AGC employee taken some time before September 2001 referring to a conversation between Saint-Gobain and AGC. The two competitors attempted to compensate each other in relation to the BMW account: “Z to compensate to X ~ 35 K cars”.271

4.4. The operation of the cartel

(120) The evidence used by the Commission in this case consists mainly of documents copied by the Commission during the February and March 2005 inspections […] including contemporaneous documentation in the form of handwritten notes and other corroborating evidence such as travel expenses and telephone records.

(121) For ease of reference, the description of the agreements and/or concerted practices which are the subject of this Decision are presented in distinct sections organised in a chronological order (per year from 1998 to 2003).

4.4.1. Start of the infringement - 1998

(122) As will be shown in this section, it can be demonstrated that […] 10 March 1998 multilateral and bilateral contacts occurred between carglass suppliers which had the object of limiting competition on the EEA carglass market. […].272 […].273 Towards the end of the 1990s Saint-Gobain and Pilkington intended to harmonise the colour and the light transmission of their respective dark tinted glass brands Venus and Sundym in order to facilitate supply to customers and to create opportunities for swaps.274 The Commission has collected evidence showing that Saint-Gobain and Pilkington had a series of meetings during […] 1998 at which they exchanged views on general technical issues and business opportunities for a rationalisation of the production range for dark tinted glass by exchanging sometimes commercially sensitive information on costs of dark tinted float production lines, which had a bearing on end prices. The purpose of these meetings was to harmonise their respective tinted glass product ranges in order to satisfy the demands by car manufacturers who wanted to have a minimum of two suppliers of dark tinted glass instead of one. Moreover, due to high production costs and to the fact that car manufacturers often would select one carglass supplier for the glass pieces including dark tinted glass pieces who then had to purchase the dark tinted float glass needed from its competitor's float production line, Saint-Gobain and Pilkington sought to render as similar as possible their respective brands Venus and Sundym as regards certain key parameters such as light transmission, colour and thickness. The two competitors therefore held these meetings and contacts so as to organise the necessary swapping of products. The intense exchanges of information allowed the two competitors to get well acquainted with its respective production ranges. One example of these contacts is described by a fax dated 8 December 1998 from Mr […] of Pilkington to Mr […] of Saint-Gobain enclosing a fax from Mr […] to Mr […] of Saint-Gobain. In this fax, an exchange of information regarding production of the privacy glass Venus 35 for Opel Astra T3000 estate between Saint-Gobain and Pilkington is described as follows: “[…]/it would seem that S.S.G. reaction to this request will be crucial in determining the future of Venus 35 Grau. If you offer it for the encapsulated q’light, & Opel accept, you will be “locked in” to making it for many years, possibly in small volume. Please advise your decision a.s.a.p.”275 The fax shows a certain degree of understanding, even though it appears that the discussion seemingly involved quite technical or 'policy' issues. However, it is noted that the fax of 8 December 1998 reads: “To […] - Blind copy for your information – please destroy, do not keep on file”, as well as on the cover page, dated 20 January 1999, on which it is written: “[…], for your information. Read and destroy. Please do not keep on file!”276. These comments show at least that Pilkington was aware of the fact that the information contained in the fax was particularly sensitive.