Commission, December 17, 2020, No M.9660

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

GOOGLE/FITBIT

1. INTRODUCTION

(1) On 15 June 2020, the Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (the “Merger Regulation”) by which Google, LLC (“Google” or the “Notifying Party”, US) intends to acquire sole control of Fitbit, Inc. (“Fitbit”, US) (the “Transaction”).4 Google and Fitbit together are collectively referred to as the ‘Parties’ throughout this Decision. The present decision concludes the examination of the notified Transaction after the serious doubts raised by the Commission by its decision on 4 August 2020 pursuant to Article 6(1)(c) of the Merger Regulation.

(2) This Decision is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the Parties. Section 3 illustrates the Transaction. Section 4 explains the reasons for considering the concentration brought about by the Transaction to have a Union dimension. Section 5 describes the procedure followed in this case. Section 6 describes the investigative steps undertaken by the Commission of the Transaction. Section 7 provides an overview of the concerned market activities of the Parties. Section 8 defines the relevant product and geographic markets. Section 9 sets out the Commission’s competitive assessment of the Transaction. Section 10 contains the Commission’s assessment of the commitments entered into by the Parties. Section 11 contains the Commission’s conclusions; and Section 12 identifies the conditions and obligations attached to this Decision.

2. THE PARTIES

(3) Google is a Delaware limited liability company and is wholly owned by Alphabet Inc. (“Alphabet”). It is a multinational technology company active in the supply of a wide range of products and services including online advertising technology, internet search, cloud computing, software and hardware. Amongst other products and services, Google develops licensable operating systems (“OSs”) for smart mobile devices (Android) and smartwatches (Wear OS) and offers a health and fitness application (“app”). Google derives a significant majority of its revenue from online advertising via its internet search engine. Google also offers IT and information/research services for the healthcare industry.

(4) Fitbit is a Delaware corporation, listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Founded in 2007, Fitbit is a technology company that develops, manufactures and distributes wearable devices, software and services in the health and fitness sector. The large majority of its revenue is derived from the supply of wearable devices, which includes fitness trackers and smartwatches. Fitbit’s software and services offering includes an online dashboard and mobile app developed for use with its wearable devices.

3. THE TRANSACTION

(5) Under the Agreement and Plan of Merger signed by the Parties on 1 November 2019 (the "Agreement"), Google will acquire all of Fitbit’s issued and outstanding common shares for a total value of approximately USD 2.1 billion (approximately EUR 1.8 billion). Following the Transaction, Google will own 100% of Fitbit’s shares. Fitbit’s shareholders approved the Transaction on 13 January 2020.

(6) Therefore, the Transaction consists of an acquisition by Google of sole control over Fitbit within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation and thus constitutes a concentration.

4. UNION DIMENSION

(7) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (Google: EUR 144 580 million; Fitbit 1 282 million)5. Each of the undertakings has an Union-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Google: EUR […] million; Fitbit: […] million), but they do not achieve more than two-thirds of their aggregate Union-wide turnover within one particular Member State.

(8) The Transaction therefore has an Union dimension pursuant to Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

5. PROCEDURE

(9) The Transaction was notified to the Commission on 15 June 2020.

(10) After a preliminary examination of the notification and based on an initial (“Phase I”) market investigation, the Commission raised serious doubts as to the compatibility of the Transaction with the internal market and adopted a decision to initiate proceedings to conduct an in-depth examination (“Phase II”) pursuant to Article 6(1)(c) of the Merger Regulation on 4 August 2020 (the “Article 6(1)(c) Decision”).

(11) The Notifying Party submitted its written comments on the Article 6(1)(c) Decision on 21 August 2020.

(12) On 26 August 2020, a state of play meeting between the Parties and the Commission took place.

(13) On 22 September 2020, the Notifying Party and the Commission agreed on an extension of the time period for the Commission’s investigation by 10 working days under the second subparagraph of Article 10(3) of the Merger Regulation.

(14) On 28 September 2020, the Notifying Party submitted commitments pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation in order to address the competition concerns identified by the Commission. On 29 September 2020, the Commission launched a market test of the commitments submitted by the Notifying Party on 28 September 2020.

(15) The Commission gave the Notifying Party detailed feedback on the outcome of the market test during calls on 9, 13 and 14 October 2020.

(16) On 16 October 2020, the Notifying Party and the Commission agreed on a further extension of the time period for the Commission’s investigation by 5 working days under the second subparagraph of Article 10(3) of the Merger Regulation.

(17) The Commission continued to give feedback on the revised commitments during calls on 20, 21, 27, 29 October 2020 and 3 November 2020.

(18) On 4 November 2020, the Notifying Party submitted revised and final commitments pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation.

(19) On 17 November 2020, the Commission sent a draft of this Decision to the Advisory Committee with the view of seeking the Committee’s opinion. The meeting of the Advisory Committee took place on 1 December 2020 and the Committee issued its positive opinion.

6. THE COMMISSION’S INVESTIGATION

(20) This Decision contains the Commission’s findings on the basis of the investigation it carried out prior to the notification of the Transaction, in the first phase, and in the second phase of the investigation.

(21) Prior to the notification of the Transaction, the Commission sent twelve requests for information (“RFIs”) to the Parties, the responses to which were included in the notification.

(22) During Phase I of the investigation, the Commission sent nine RFIs to the Parties, including requests for internal documents and data, as well as seven data RFIs to third parties. In addition, the Commission sent two RFIs to (i) over 100 online advertising services providers, wearable original equipment manufacturers (“OEMs”)6 and app developers, as well as (ii) over 100 digital healthcare players. In total, the Commission received over 50 replies from third parties during Phase I of the investigation.

(23) During Phase II of the investigation, the Commission sent seventeen RFIs to the Parties. as well as four dedicated RFIs to (i) about 70 online advertising services providers (Google’s competitors in online advertising markets), (ii) about 80 online advertisers and media agencies (Google’s customers in online advertising markets),

(iii) over 50 Android smartphone OEMs7 and wearable OEMs as well as app providers and (iv) almost 50 digital healthcare players. In total, the Commission received over 100 replies from third parties during Phase II.

(24) Throughout the whole market investigation, the Commission also conducted multiple interviews with market participants, such as with online advertisers, wrist- worn wearable OEMs, app developers, digital healthcare players, their respective industry organisations as well as other stakeholders.

(25) The Commission also reviewed internal documents submitted by the Parties in response to RFIs from the Commission. In total, the Parties have provided more than 1 000 000 documents to the Commission (Google around 247 000 and Fitbit around 828 000).

7. INDUSTRY OVERVIEW

(26) This section provides an overview of all sectors that are relevant for the purpose of assessing the Transaction in order to provide context for the relevant market definition and the competitive assessment undertaken in Section 8 and Section 9.

7.1. Wearable devices

7.1.1. Types of devices

(27) Wearable devices encompass devices that are worn in the ear, on the finger, over the eyes, as part of clothing and on the wrist. Since those devices rest on the body, they can be equipped with sensors that allow to record health and body measurements. As technology advances, wearable devices are also incorporating more sophisticated chipsets and antennae, enabling these devices to offer not only Bluetooth and Wi-Fi, but also GPS and cellular8 connectivity.

(28) Within wearable devices, the largest segment are wrist-worn wearable devices. This is a fast-growing category that includes fitness trackers and smartwatches.

(a) Fitness trackers have sensor hardware that allows users to record and monitor various health and activity metrics such as heart rate, daily activity (for example steps taken, distance travelled) and sleep duration. The most advanced models may also include further metrics, such as oxygen saturation.

(b) Smartwatches have larger screens and typically offer more advanced health and fitness features than fitness trackers. They also usually provide additional functionality such as communication and entertainment functions. In particular, this may include the ability to install apps on the smartwatch and to interact with apps on the smartphone, for example to display call/text/calendar notifications on the smartwatch with quick reply options.9 Some smartwatches offer cellular connectivity.

(29) Up to the time of adoption of this Decision, some fitness trackers and smartwatches collect precise geographic position data using built-in GPS, while most wrist-worn devices cannot collect this information independently but rely on the tethered mobile device.

(30) The importance of smartwatches is steadily growing, even though there was also a significant increase in sales of fitness trackers in 2019. In volume terms, the smartwatches segment ([…] million) was twice as big as what the fitness tracker segment ([…] million) was in the EEA in 2019. In value terms, the smartwatches segment (EUR […] million) was ten times larger than what the fitness tracker segment (EUR […] million) was in the EEA in 2019. The market evolution of the segments for smartwatches and fitness trackers between 2016 and 2019 in volume terms in the EEA is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Sale evolution of the smartwatches and fitness trackers in the EEA (2016-2019, shipments)

[Third party data]

Source: IDC.

(31) On the worldwide level, the trend is similar. Nevertheless, in value terms, the smartwatches segment (EUR […] million) was almost eight times larger than what the fitness tracker segment (EUR […] million) was in 2019.

(32) A distinction can be made between basic and full smartwatches. In contrast to full smartwatches, basic smartwatches do not run third-party apps. With respect to the full smartwatches segment, connected smartwatches with cellular connectivity will overtake smartwatches with no cellular activity by [Third party data], as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Sale evolution of the smartwatches with and without cellular connectivity in the world (2018- 2023, shipments)

[Third party data]

Source: IDC, October 2019.

(33) Of the many suppliers of wrist-worn wearable devices, the following are the main players:

(a) Fitbit is a pioneer in wrist-worn wearable devices, launching its first fitness tracker model in 2009. Fitbit introduced its first smartwatch in 2017. Fitbit currently does not yet offer a smartwatch with cellular connectivity.

(b) Apple launched its first smartwatch, called Apple Watch, in April 2015. Since then, the company has consistently been at the forefront of wearable technology, releasing a new device every September with new features. For instance, Apple introduced the category of connected smartwatches with cellular connectivity with its fourth series released in 2018. Apple does not offer fitness trackers.

(c) Samsung has used its considerable experience in consumer electronics to launch a wide range of wearable devices, and currently markets fitness trackers and full smartwatches, some with cellular connectivity.

(d) Huawei offers low-cost fitness trackers and both basic and full smartwatches. It has grown to command significant market shares in recent years. In view of US trade sanctions10, Huawei has stated that it is planning to transition its smartwatches to its internally developed Harmony OS.

(e) Xiaomi became the largest supplier of wrist-worn wearable devices worldwide in 2019, powered by its enormous sales of low-cost fitness trackers. More recently, in November 2019, Xiaomi launched its first smartwatch that runs third-party apps and has cellular connectivity. Xiaomi collaborates with Huami, which also markets its own products under the Amazfit brand.

(f) Garmin supplies both fitness trackers and smartwatches, including connected ones. Unlike Apple, Samsung, Huawei, and Xiaomi, Garmin does not supply smartphones.

(g) Fossil is a fashion-focused watchmaker, which manufactures a wide range of basic and full smartwatches. Besides marketing watches under the Fossil brand, the company also partners with a wide range of fashion houses, including Michael Kors, Diesel, and Emporio Armani.

(34) In addition, there are a number of smaller competitors, such as Mobvoi, Polar, BBK, Suunto and many more.

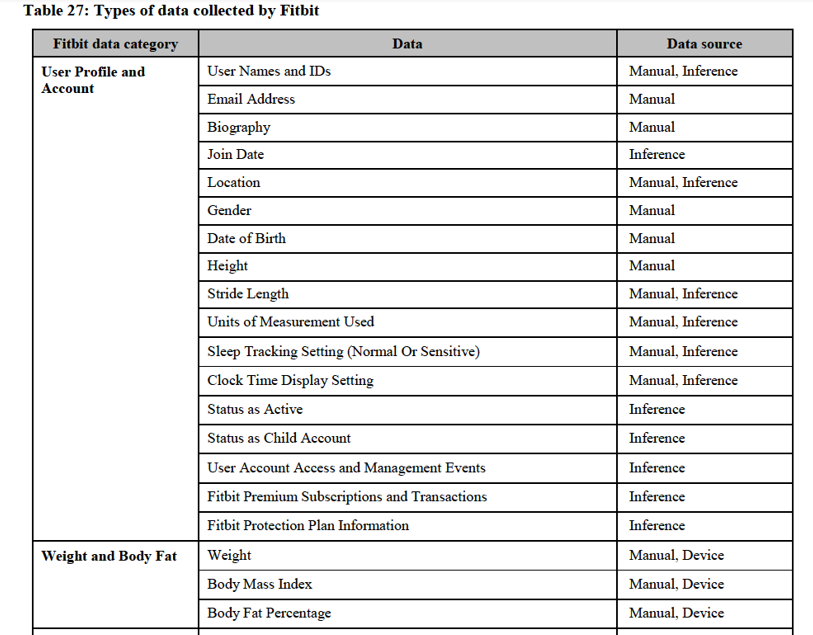

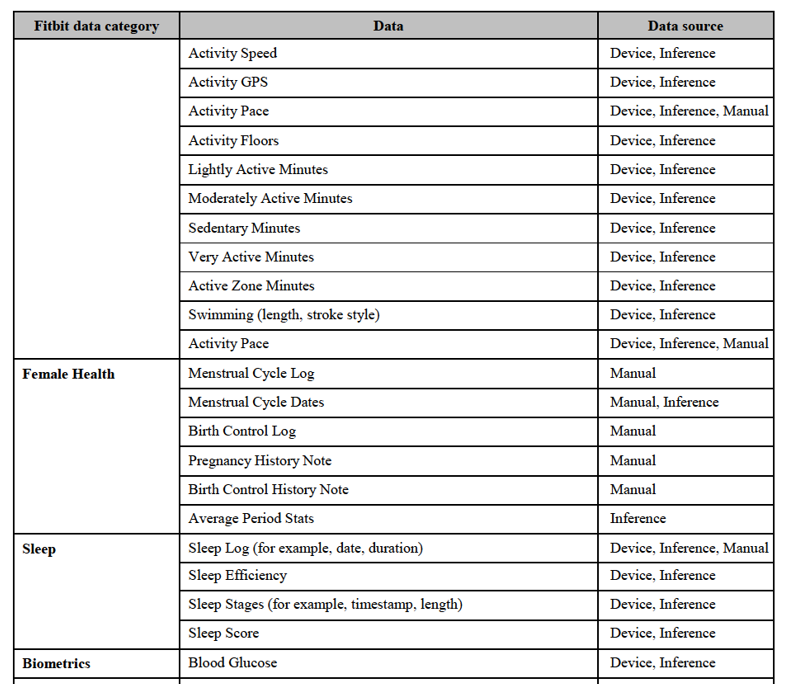

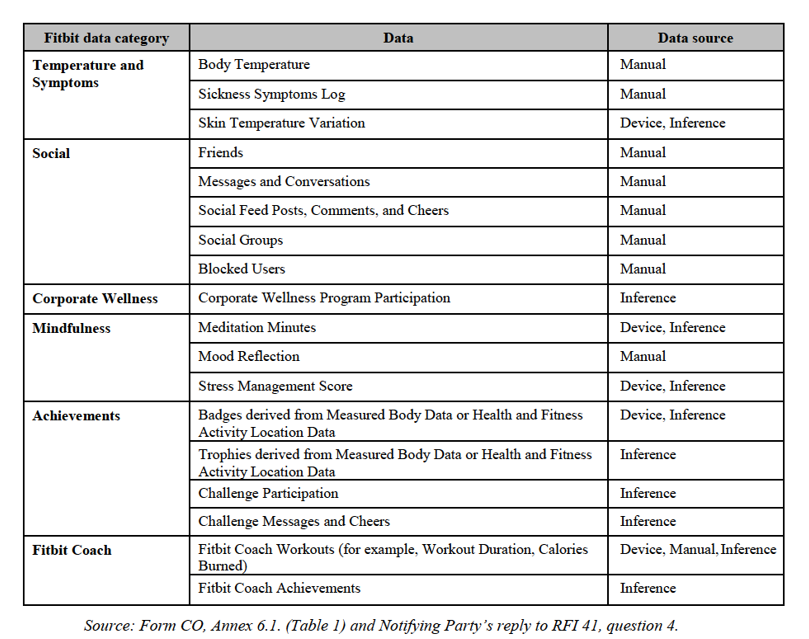

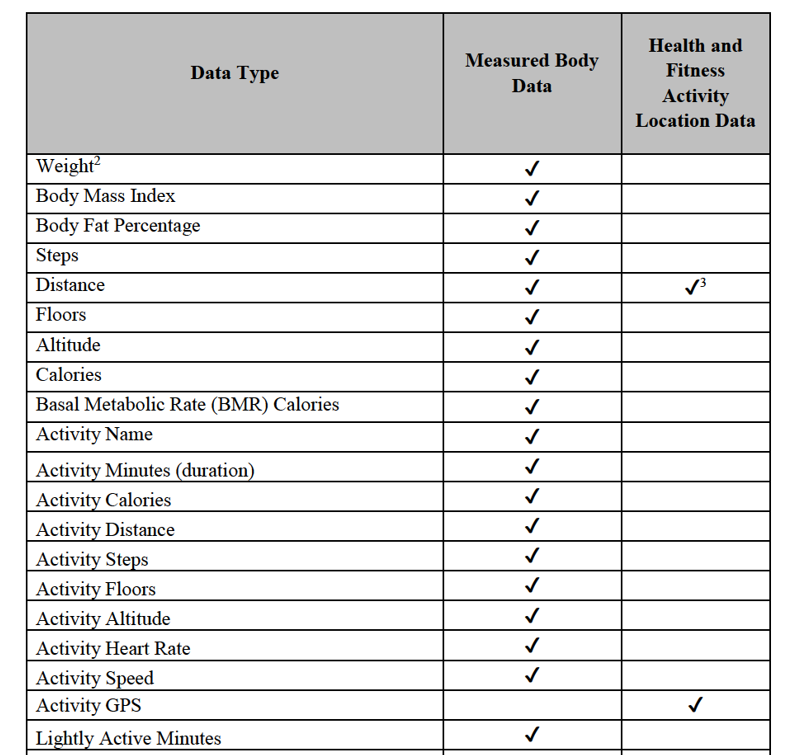

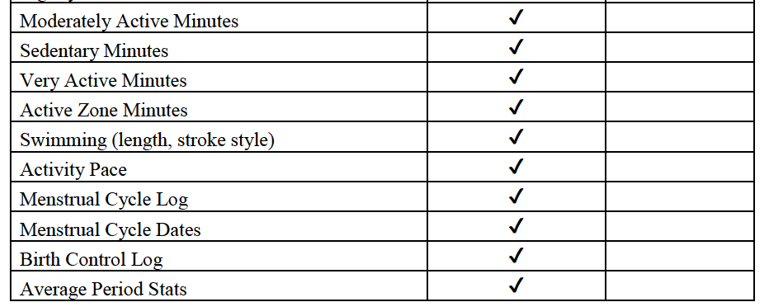

7.1.2. Data generated by wearables

(35) Wearable devices are equipped with sensors that allow recording data relating to certain health and body measurements as well as other types of data, such as location data.

(36) Raw sensor data is either processed on the device itself (for example, accelerometer raw data is processed into “steps” information) or, when an algorithm is too demanding to run on the device, it is transferred to a server for processing (for example, sleep data).

(37) Typical wrist-worn wearable devices can measure certain users’ daily activities and health metrics, such as the number of steps taken, the calories burned, the distance travelled, the floors climbed, and the minutes of activity, as well as the sleep duration and quality and the heart rate.

(38) The sensor data can be automatically combined with location data either from on- board GPS or from location information provided by a tethered mobile device, if geo-localization is activated.

7.1.3.Health and fitness apps

(39) Users of wearable devices typically connect their device to health and fitness apps on a smartphone to review, analyse, store and/or export the data generated by the wearable device.

(40) Besides displaying and processing the data generated from wearable devices, health and fitness apps on smartphones can also display certain simple data types (for example, simple step or activity counts) based on sensors of the smartphone. Health and fitness apps may offer additional features, such as fitness goal suggestions, mindfulness and meditation exercises, general and professional physical training, activity and daily habits tracking, nutrition and weight-loss monitoring and advice, as well as menstrual cycles monitoring.

(41) Suppliers of wrist-worn wearable devices typically offer one or several companion apps, which enable the users to initialize and synchronize their devices with the smartphone, but which also cover the functionalities of a health and fitness app. Users can also opt to use a third-party health and fitness app, which can import the users’ data (with their consent) through an application programming interface (“API”).11

7.2. OSs

(42) OSs are software systems that control the basic functions of computing devices such as servers, PCs, tablets and mobile as well as wearable devices and enable the user to operate the device and run application software on it.12

(43) OSs that are designed to support the functioning of smart mobile devices, i.e. smartphones and tablets, and the corresponding apps are hereinafter referred to as "smart mobile OSs".

(44) Smart mobile OSs typically provide a graphical user interface, APIs, and other ancillary functions, which are required for the operation of a smart mobile device and allow for new combinations of functions to offer greater usability and innovations. Apps written for a given smart mobile OS will typically run on a smart mobile device using the same OS, regardless of the manufacturer.

(45) Smart mobile OSs are developed by vertically integrated OEMs such as Apple for captive use on their own smart mobile devices (“non-licensable smart mobile OSs”), or by providers such as Google (with Android), which license their smart mobile OS to other OEMs (“licensable smart mobile OSs”). The licensing of a smart mobile OS therefore constitutes an economic activity upstream from the level of sales of smart mobile devices to users.

(46) Smart mobile OSs need to interact with the OSs of wearable devices “wearable OSs”.

(47) Similarly to smart mobile OSs, wearable OSs are developed by vertically integrated OEMs such as Apple, Fitbit or Garmin for use on their own wearable device or by providers such as Google (with its Wear OS), which license their wearable OS to OEMs.

7.3. App stores

(48) The development of smart mobile devices has led to the emergence of a new type of software: app stores, i.e., digital distribution platforms, constituted by online services and related apps that are dedicated to enabling users to download, install and manage a wide range of diverse apps from a single point in the interface of the smart mobile device.13

(49) Similarly, there are app stores for wearable devices that enable users to download, install and manage a wide range of diverse apps on their wearable device from a single point in the interface of the smart mobile device.

(50) App stores are generally available to users for free. Users only pay to download certain apps or acquire paid content within apps ("in-app purchases"). Developers of revenue-generating apps typically pay an app store a fixed percentage of their app- related revenues when users pay for the download of apps or make in-app purchases.

7.4. Search engines

(51) Search engines allow users to search for information across the Internet. Typically, based on a search query entered by the user, the search engine provides the user with the most relevant results. Search engines are usually free of charge for the user and are in most cases financed by advertisements that are selected on the basis of the user’s search query (‘search ads’), as explained below in Section 7.5. Most search engines are accessible from a desktop browser, a mobile app or a wearable app.

7.5. Online advertising and ad tech services

(52) There are two types of online ads:

(a) Search ads, which are displayed on the basis of search queries entered by users into internet search engines (that is to say, advertisers can specify the keywords for which they want their ads to be triggered or the queries for which they are most likely to be relevant). Search ads are typically presented next to the search results on the search engine’s own pages or other search results pages.

(b) Non-search or display ads, which can be either contextual ads, displayed according to the content of the page on which they appear, or non-contextual ads. Since no query-keyword is available to trigger display ads, the data collected about the user accessing the pages is relatively more important for the selection of display ads than for the selection of search ads.

(53) The online advertising sector has developed over the past 10 years towards ever increasing automatisation. Digital advertising space (or “inventory”) can be sold at a fixed price through direct deals between the publishers (the “sell side”) and individual advertisers or media agencies (the “buy side”). The matching between the two sides can also be made by intermediaries. The vast majority of digital advertising space is now sold by intermediaries in “programmatic” forms. In programmatic buying, the purchase of a particular piece of advertising inventory is made in an automatized way on the basis of predetermined criteria tailored to or chosen by the relevant advertisers or publishers, including information such as the webpage in which the ad will appear, the ID of the user to whom the ad will be shown, the minimum price at which the publisher is willing to sell the ad space etc.. The majority of programmatic advertising is done via online auctions using real- time-bidding, which is the nearly instantaneous buying and selling of advertising space (the whole process happens in the time it takes for a webpage to load into a user’s web browser).

(54) In this context, the advertising supply chain involves a diversified network of intermediaries that provide technologies and/or data (“ad tech”) to facilitate the programmatic sale and purchase of digital advertising inventory.

(55) The key intermediaries in the ad tech value chain are:

(a) Demand Side Platforms (“DSPs”): (buy-side) platforms that allow advertisers and media agencies to buy advertising inventory from many sources (ad exchanges, ad networks, Supply Side Platforms).

(b) Supply Side Platforms (“SSPs”): (sell-side) platforms that automatise the sale of digital inventory. Their core purpose is to help publishers to sell their inventory. Those platforms allow real-time auctions by connecting to multiple DSPs, collecting bids from them and performing the function of exchanges.

(c) Advertiser ad servers: solutions used by advertisers and media agencies to store the ads, deliver them to publishers, keep track of this activity and assess the impact of their campaigns by tracking conversions.

(d) Publisher ad servers: publishers use ad servers to manage their inventory. Those servers make the final choice of which ad to display, based on the offer received from different SSPs and DSPs and the direct deals agreed between the publisher and advertisers.

(e) Ad exchanges: a digital marketplace where SSPs and DSPs connect. The ad exchange runs the auction and decides the winner, that is to say which bidder (advertiser) wins the impression on the inventory. Ad exchanges used to be separate, but at the time of this Decision SSPs typically incorporate an ad exchange as part of their technology offering.

(f) Ad networks: platforms that integrate most intermediation functions into a single service. They aggregate inventory supply from publishers and match it with advertisers.

(g) Data services suppliers: different players providing advertisers and publishers with tools to collect, store, manage and analyse data.14 The users of such tools can receive the data from multiple sources, including the advertisers themselves or third party licensors.

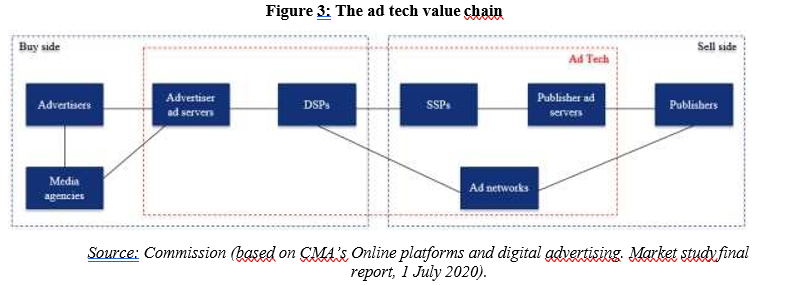

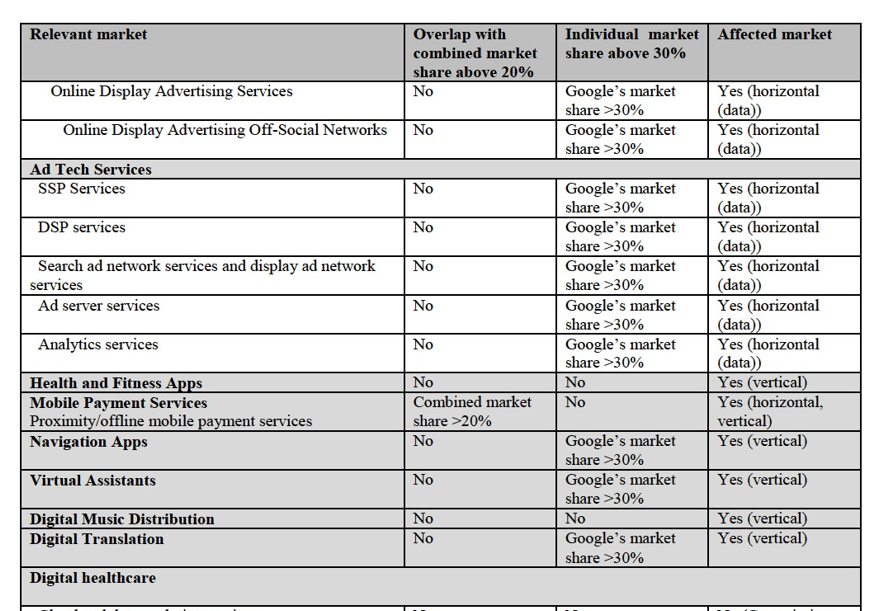

(56) A simplified version of the ad tech value chain is provided in Figure 3 below.

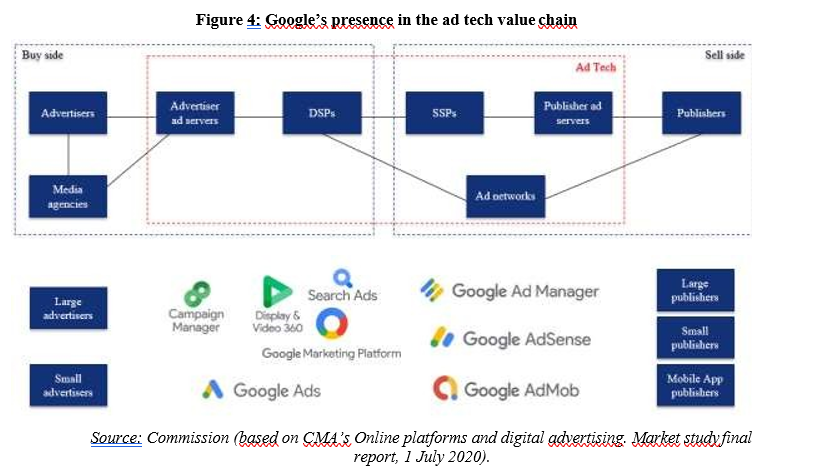

(57) Google supplies online advertising services at all levels of the ad tech value chain. In particular, Google provides:

(a) For advertisers:

– Google advertiser ad server Campaign Manager;

– Google’s DSP: Display&Video 360, which helps (typically large) advertisers to buy ad space on Google’s own non-search ad inventory (for example YouTube), but also on ad exchanges and/or SSPs, so that these ads can be delivered eventually on third party publishers;

– Google’s search campaign management platform SearchAds 360 (equivalent to DSP functions for search ads), which helps (typically large) advertisers to manage their campaigns on Google’s own search engine and third party search engines (Microsoft Ads, Yahoo!, Baidu);

– Google’s alternative platform for buying advertising space, Google Ads (formerly AdWords). Google Ads essentially serves the same purposes as SearchAds 360 and Display&Video 360, but typically for smaller advertisers. Google Ads is a buying interface for advertisers through which they can access both Google’s own surfaces (so called “owned and operated” or “O&O” surfaces) and ad space inventory of third-party publishers. Advertisers can choose different types of campaigns in Google Ads based on their advertising goals.

(b) For publishers:

– Google Ad Manager: an SSP solution for large publishers, which groups Google’s ad server for publishers (previously DoubleClick for Publishers) and its SSP/Ad exchange (previously AdX);

– Google AdSense: an ad network solution for smaller publishers, which delivers Google ads on the websites of publishers;

– Google AdMob: an ad network solution for ads served on mobile apps.

(58) Moreover, as part of the Google Marketing Platform, Google Analytics provides web analytics service that tracks and reports web traffic.15

(59) Google’s presence at the various levels of the value chain is illustrated in the below Figure 4.

7.6. Digital healthcare services

(60) The large penetration of smart digital devices among consumers has significantly increased the amount and level of detail of user data available to the economy. The healthcare sector is one of the sectors benefiting from the streams of data and monetisation, since user data can inform tools for the prevention (or early detection) of serious medical conditions (for example diabetes, obesity, atrial fibrillation, etc.), which contributes to the adoption of healthier lifestyle by users and a decrease of health expenditure. It may also facilitate medical research. The sum of these initiatives is a sector commonly referred to as digital healthcare. Digital healthcare is still a nascent sector, whose development largely depends on the type of data and digital technology available. Both technology companies Google and Fitbit among others and traditional healthcare companies are making progress in order to establish themselves in this new sector.

(61) Digital healthcare is not characterised by a prevailing business model, but the combination of data and technology leads to a variety of business initiatives and monetisation modes. A common feature of all business initiatives is the relevance of user data, widely expected to have a significant impact on healthcare. As they allow establishing connections - and thus extracting additional conclusions - from sets of previously unrelated data, data-based solutions (sometimes referred to as Big Data) will provide new insights for medical research that were impossible to obtain before. It may be possible, for example, to link diseases - such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, depression - to human behaviour, lifestyle or other causes that are characteristic of a given geographic area or group of people.

8. RELEVANT MARKETS

8.1. Introduction

(62) The Parties both supply (i) wearable devices, (ii) an OS for wearable devices, (iii) app stores for wearable devices, (iv) health and fitness apps, and (v) mobile payment apps. The Transaction accordingly may create some horizontal overlaps in those areas. However, the Parties are not always active in the same product markets.16

(63) The Transaction also creates a number of non-horizontal relationships between Fitbit’s activities in the supply of wrist-worn wearable devices (and associated companion apps) and Google’s activities in the supply of (i) online search and display advertising services (including intermediation services), (ii) general search services, (iii) licensable OSs for smart mobile devices, (iv) licensable OSs for smartwatches, (v) Android app stores, and (vi) various apps and services that are or could be offered on wrist-worn wearable devices. In addition, there is a non- horizontal relationship between Fitbit’s apps store for its wearable devices and Google’s supply of various apps for wearable devices.

(64) Finally, both Parties are active in the digital healthcare sector.

(65) In the present Section 8, the Commission assesses the relevant product and geographic market definitions.

8.2. Wearable devices

(66) Both Parties supply wearable devices. While Google supplies earwear and eyewear devices, Fitbit is active in wrist-worn wearable devices, including both fitness trackers and smartwatches. [Google’s product strategy]. [Google’s product strategy].

8.2.1. Product market definition

8.2.1.1. Commission precedents

(67) In Apple/Beats, the Commission examined the possibility of assessing the market for the supply of headphones as separate from other audio equipment, but ultimately decided to leave the product market definition open.17

(68) The Commission has not previously considered the market for wrist-worn wearable devices.

8.2.1.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(69) The Notifying Party considers that the relevant product market should encompass all wrist-worn wearable devices, but exclude other wearable devices such as earwear and eyewear.18

(70) As regards earwear, the Notifying Party explains that their primary function is to play audio. As a result, their smart functions tend to be far more limited than those offered by wrist-worn devices.19 As regards eyewear, the Notifying Party considers that Google’s own product (Google Glass) is a productivity tool for businesses. In particular, Google Glass does not contain any of the sensors necessary to track the health metrics expected by consumers of wrist-worn wearable devices.20 Moreover, the Notifying Party submits that eyewear’s and earwear’s components and underlying technologies are very different from wrist-worn devices.

(71) The Notifying Party considers that there is no reason to further segment wrist-worn wearable devices, as there is a very considerable overlap in the features offered by fitness trackers and smartwatches. According to the Notifying Party, there is a continuous chain of substitution extending from basic fitness trackers through to full smartwatches.21

(72) The Notifying Party does not consider it appropriate to segment wrist-worn wearable devices on the basis of either cellular connectivity or GPS functionality.22 According to the Notifying Party, devices without these features clearly exercise direct and significant pressure on device that do offer these features.

(73) However, the Notifying Party considers that, since the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the product market for wearable devices can be left open.

8.2.1.3. The Commission’s assessment

(74) In line with the Notifying Party's submission and the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers that wrist-worn wearables constitute a separate product market from other types of wearable devices.

(75) From a demand-side perspective, the majority of respondents indicated that users do not consider other wearable devices, in particular connected rings, earwear and eyewear, as substitutes for wrist-worn wearable devices, namely. smartwatches and fitness trackers.23 Respondents explained that the devices specific to different body parts have different functions. Nevertheless, some respondents indicated that connecting rings could offer some but not all functionalities of a fitness tracker.

(76) From a supply-side perspective, only about half of respondents indicated that suppliers of other wearable devices could develop and start offering to consumers wrist-worn wearable devices in the short term and without incurring significant costs through investments.24 Respondents highlighted that the barriers to entry in the supply of smartwatches were particularly high.

(77) As regards the question of whether or not it is necessary to further segment the market for wrist-worn wearable devices, the majority of respondents indicated that users consider smartwatches and fitness trackers as substitutes.25 Nevertheless, respondents also pointed out that smartwatches and fitness trackers offer different functionalities and are marketed at very different price points. Considering the supply-side, a majority of respondents reported that suppliers of fitness trackers could develop and start offering smartwatches (and vice versa) in the short term without incurring significant investment.26

(78) Regarding GPS and cellular connectivity, respondents to the market investigation reported that these functionalities are important factors driving consumers’ choices for wrist-worn wearable devices, albeit cellular connectivity is only relevant for smartwatches as it is not offered on fitness trackers.27 However, since for both GPS and cellular connectivity a substantial share of respondents answered that “it depends on the price”, it appears that devices with and without these features may exercise a direct constraint on each other. As regards other important distinguishing features, respondents to the market investigation highlighted the difference between basic and full smartwatches, the latter also supporting third-party apps. This distinction is not relevant for fitness trackers, which generally do not carry apps.

(79) In light of recitals (74) to (78), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction in this Decision, the Commission considers that the relevant product market is the market for wrist-worn wearable devices. The question whether the supply of wrist-worn wearable devices should be further segmented between (i) fitness trackers and smartwatches, (ii) fitness trackers and smartwatches with and without GPS connectivity, (iii) smartwatches with and without cellular connectivity and (iv) basic and full smartwatches can be left open in this Decision since the Parties do no overlap as regards wrist-worn wearable devices and any further segmentations would thus not change the outcome of the competitive assessment in the present case.

8.2.2. Geographic market definition

8.2.2.1.Commission precedents

(80) The Commission has not previously considered the market for wrist-worn wearable devices.

8.2.2.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(81) Referring to the Commission’s decisional practice with respect to smart mobile devices28, the Notifying Party submits that the geographic market for wrist-worn wearable devices is worldwide or at least EEA-wide.29

(82) However, the Notifying Party considers that, since the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the geographic market for wearable devices can be left open.30

8.2.2.3. The Commission’s assessment

(83) Responses to the to the market investigation suggest that there are no significant differences in customer demand and/or requirements between different EEA countries, however, that there are some significant differences across regions such as the EEA, North America and China.31 From the supply side, it seems that transport costs are rather low and products are manufactured globally and shipped to customers throughout the world. For instance, the 10 largest vendors of wrist-worn wearable devices in the EEA by volume are spread throughout the world: Apple, Garmin, Fossil, and Fitbit are based in the United States; Xiaomi, Huami, and Huawei are based in China; Samsung is based in South Korea; and Suunto and Polar are based in Europe.32 Nevertheless, as can be seen from market shares (see Section 9.1.1), competitive conditions and competitors’ market position can vary significantly by geographic region.

(84) In light of recital (83) , for the purpose of assessing the Transaction in this Decision, the Commission considers that the geographic scope of the relevant product markets for wrist-worn wearable devices identified in recital (79) above is at least EEA-wide if not worldwide.

8.3.OSs

(85) Google maintains and develops the Android ecosystem, which includes an open- source smart mobile OS. Google also maintains and develops its own wearable OS called Wear OS, based on Android OS, which it licenses to OEMs for use on smartwatches [Google’s strategy].

(86) Fitbit owns two OSs which it does not licence to third parties: [Fitbit OS 1], which is used exclusively on Fitbit’s fitness trackers, and [Fitbit OS 2], which is exclusively used on Fitbit’s smartwatches.

(87) For the purpose of the market definition, the Commission has thus examined both (i) OSs for smart mobile devices and (ii) OSs for wrist-worn wearable devices.

8.3.1. Product market definition

8.3.1.1. Commission precedents

(88) In Google/Motorola Mobility, while leaving the exact market definition open, the Commission took the view that OSs for PCs and OSs for smart mobile devices33 belong to separate product markets, given that both such OSs use different hardware and have different performance capacities.34 A similar approach was adopted in Microsoft/Nokia35, Microsoft/Linkedin36 and Apple/Shazam37.

(89) In Apple/Shazam38, the Commission left open whether it is appropriate to consider segmentations by further device type, that is, in addition to OSs for PCs and smart mobile devices, also as regards smart TVs and different types of smart wearable devices. In particular, the evidence on file was inconclusive on whether OSs for smart wearable devices constituted a separate market from OSs for smart mobile devices.

(90) In addition, in Google Android, the Commission concluded in the context of OSs for smart mobile devices that licensable and non-licensable OSs belong to separate product markets.39 This question was left open in previous relevant Commission decisions.

8.3.1.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(91) The Notifying Party considers that the relevant product market for wearable OSs is separate from the market for OSs for other smart devices, such as smart mobile devices. That is because (i) wearable devices use very different hardware and have different performance capacities, (ii) the principal smart mobile OS developers, Google and Apple, have each developed a separate OS to run on wearable devices and (iii) apps developed for smart mobile OSs are specific to smart mobile devices and cannot be directly ported to wearable OSs.40

(92) The Notifying Party submits that no further distinction is needed between OSs for fitness trackers and smartwatches.41 While Fitbit has developed separate OSs for fitness trackers and smartwatches and Google’s Wear OS is only used on smartwatches, the Notifying Party considers that the line between OSs for fitness trackers and OSs for smartwatches is increasingly blurred. Moreover, [Fitbit OS 2] which Fitbit employs in its smartwatches is an RTOS42, which is by far the most common type of OS used for fitness trackers (more than 99% of fitness trackers run on RTOSs) and accounts for a significant share of smartwatches. Although development costs of wrist-worn wearable OSs can vary depending on their sophistication, these OSs are all part of the same spectrum of software solutions, without any clear qualitative demarcation between these solutions.

(93) The Notifying Party considers that it is inappropriate to segment the relevant market between licensable and non-licensable OSs.43 According to the Notifying Party, licensable and non-licensable OSs compete to attract users and developers.

(94) However, the Notifying Party considers that, since the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the product markets for OSs for smart mobile and wearable devices can be left open. 44

8.3.1.3. The Commission’s assessment

(95) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication which would suggest that, in defining the relevant product market for OSs, it would be appropriate to depart from its previous practice as to the distinction between OSs for PCs and OSs for smart mobile devices.45

(96) With regard to wearable OSs, in line with the Notifying Party's submission and the results of the market investigation46, the Commission considers that wearables OSs constitute a separate product market from smart mobile OSs. Respondents to the market investigation emphasised that wearable OSs are customised products, which are specifically designed for wearable devices. From a demand-side perspective, it is not possible for an OEM to simply transfer an OS for PCs, smart TVs or smart mobile devices onto wearable devices. While it is possible and common to adapt OSs for smart mobile devices for use on wearable devices (for example iOS, Android OS), this requires a significant level of customisation. From a supply-side perspective, the majority of respondents also indicated that a supplier of an OS for smart mobile device could not develop and start offering in the short term and without undertaking significant investment an OS for wearable devices.47 For the same reasons, and based on the results of the market investigation, the Commission considers that OSs for wrist-worn wearable devices, which are relevant in the context of the Transaction, constitute a separate product market from OSs for non- wrist-worn wearable devices.

(97) As regards the question whether OSs for different types of wrist-worn wearable devices constitute distinct product markets, the evidence in the Commission's file was not conclusive.48

(98) With regard to the distinction between licensable and non-licensable OSs, the respondents to the market investigation acknowledged a degree of competition between licensable and non-licensable OSs at the level of the user of smart mobile and wrist-worn wearable devices, but they did not indicate that licensable and non- licensable OSs can be seen as substitutes from an OEM perspective.49

(99) From the demand-side, OEMs cannot obtain a licence to use a non-licensable OS on their smart mobile or wrist-worn wearable devices. From the supply-side perspective, developers of OSs are unlikely to readily change the status of their OS. For instance, while Apple’s iOS and Fitbit’s proprietary OSs [Fitbit OS 1] and [Fitbit OS 2] have always been non-licensable, Google’s Android OS and Wear OS have always been licensable. The majority of respondents to the market investigation confirmed that suppliers of non-licensable OS are unlikely to start licensing their OS to third-party OEMs, mentioning in particular Apple as example.50 Therefore, the Commission considers that licensable and non-licensable OSs constitute separate product markets due to a lack of demand-side and supply-side substitutability.

(100) In light of recitals (95)-(99), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction, the Commission considers that the relevant product markets are:

(a) The supply of licensable OSs for smart mobile devices; and

(b) The supply of licensable OSs for wrist-worn wearable devices, potentially segmented along the lines of the potential segments of the market for wrist- worn wearable devices listed in recital (79).

8.3.2.Geographic market definition

8.3.2.1. Commission precedents

(101) In its previous decisional practice, the Commission has usually considered the market for OSs for smart mobile devices to be EEA-wide, if not worldwide, but it has ultimately left the exact geographic market definition open51. However, in Google Android, it concluded, in relation to licensable OSs for smart mobile devices that the market is worldwide excluding China.52 This conclusion was based on the fact that barriers to entry are low in most of the regions of the world (for example, there are no trade barriers and limited language-specific demand characteristics), and agreements between OEMs and OS developers are generally worldwide in scope. At the same time, conditions of competition were found to be different in China because Google’s activities in China are limited and there is a number of OEMs that sell devices in China based on modified Android versions which were not recognised by Google as “Android-compatible” and thus could not be successfully marketed outside of China.

(102) The Commission has not previously considered the geographic scope of the market for licensable OSs for wrist-worn wearable devices.

8.3.2.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(103) The Notifying Party submits that the relevant geographic markets are worldwide, as OEMs generally enter into a single worldwide licensing agreement.53

(104) However, the Notifying Party considers that, since the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the geographic markets for OSs for smart mobile and wearable devices can be left open.54

8.3.2.3. The Commission’s assessment

(105) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication which would suggest that, in defining the relevant product market for licensable OSs for smart mobile devices, it would be appropriate to deviate from its previous finding that the market is worldwide excluding China.55

(106) With regard to the market for licensable OSs for wrist-worn wearable devices, responses to the market investigation suggest that there are no significant differences in customer demand and/or requirements between different EEA countries but that there are some significant differences across regions such as the EEA, North America and China.56 From the supply side, similar arguments as for licensable OSs for smart mobile devices hold. OEMs generally enter into a single worldwide licensing agreement with the wearable OS provider. Due to the nature of wearable OSs, factors such as import restrictions, transport costs and technical requirements are not meaningful. Although wearable OEMs may require specific language capabilities for certain regions or countries, these do not constitute a significant obstacle to cross-border supplies.57 Nevertheless, as can be seen from market shares (see Section 9.1.2), competitive conditions and competitors’ market position can vary significantly by geographic region. In particular, conditions of competition were found to be different in China. There are a number of OEMs which sell devices with their OSs only in China.58

(107) In light of recitals (105)-(106), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction, the Commission considers that the geographic scope of the markets for licensable OSs for smart mobile devices is worldwide excluding China, while the geographic scope of the market for licensable OSs for wrist-worn wearable devices is at least EEA- wide, and potentially even worldwide excluding China.

8.4.App stores

(108) Google runs the “Play Store” to distribute apps on its open-source smart mobile OS (Android OS) and its wearable OS (Wear OS).

(109) Fitbit maintains the “Fitbit App Gallery” to distribute apps on its wearable OSs.

(110) For the purpose of assessing the Transaction, the Commission has thus examined both (i) app stores for smart mobile devices and (ii) app stores for wearable devices.

8.4.1. Product market definition

8.4.1.1. Commission precedents

(111) For smart mobile devices, in Google Android, the Commission has defined digital distribution platforms, that is to say “app stores,” as online services and related apps dedicated to enable users to download, install, and manage different apps from a single point in the interface of the smart mobile device.59 The Commission considered app stores to belong to a separate product market from other apps, based on their (i) pre-installation requirement to enable users to download other apps, (ii) specific distribution channel function, and (iii) time and resource demands for development, regardless of a developer’s general experience.60

(112) In Google Android, the Commission also found that Android app stores belong to a distinct product market, because smart mobile device OEMs would need to switch to another licensable OS in order to offer a different app store, but that these OEMs are unlikely to do so, inter alia because (i) users are unlikely to switch to a device with a different OS due to the small spending in app stores, switching costs and the degree of OS loyalty, and (ii) Google Android is currently the smart mobile OS with the largest number of apps and users.61

(113) The Commission concluded that app stores for a given OS platform of smart mobile devices (namely Android app stores) constitute a separate relevant product market.62

(114) The Commission has not previously considered a market for apps stores on wearable devices.

8.4.1.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(115) The Notifying Party considers that the exact scope of the relevant product markets can be left open, as no competition concerns would arise under any plausible market definition.63

(116) In addition, with regard to app stores on wearable devices, the Notifying Party notes that, were the Commission to apply the approach from the Google Android case, there would be no overlap between the Parties’ offering as the Parties’ app stores are platform-specific, namely Google Play is only available on Wear OS devices and the Fitbit App Gallery on Fitbit devices.64

8.4.1.3. The Commission’s assessment

(117) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication which would suggest that, in defining the relevant product market for app stores for smart mobile devices, it would be appropriate to depart from its previous practice.65

(118) In line with the Notifying Party's submission and the results of the market investigation,66 the Commission thus considers that app stores for a given OS platform of smart mobile devices (namely Android app stores) constitute a separate relevant product market from app stores for other OS platforms. The Commission concludes that different app stores for Google Android devices belong to the same product market.

(119) From a demand-side perspective, an OEM can, in principle, choose from a number of different Android app stores for its Google Android devices. Moreover, the majority of respondents to the market investigation indicated that customers consider other Android app stores as an alternative to Google Play, while not considering app stores for other OS platforms.67 Some market respondents however, pointed out, while generally agreeing that other Android app stores could be an alternative to the Play Store, that they have so far only played a limited role.68

(120) Given the multi-sidedness of app stores, it is important to consider also the perspective of app developers. In Google Android the Commission concluded that app developers would be unlikely to switch from developing apps for Google Android devices to developing apps for smart mobile devices with a different smart mobile OS because, in doing so, they would forego access to a large number of users of smart mobile devices.69

(121) With regard to app stores on wearable devices, the Commission considers that similar arguments apply.

(122) Just like on smart mobile devices, the Commission considers app stores on wearable devices to belong to a separate product market from other apps, based on their (i) pre-installation requirement to enable users to download other apps, (ii) specific distribution channel function, and (iii) time and resource demands for development, regardless of a developer’s general experience.

(123) Moreover, the Commission considers that there are separate markets for app stores for a given OS platform of wearable devices. From an end user demand-side perspective, the majority of respondents to the market investigation indicated that customers cannot choose between different app stores for their devices running on Wear OS and Fitbit OSs.70 Google Play is the only app store via which users can download apps onto their Wear OS devices. The Fitbit App Gallery is the only app store via which users can download apps onto their Fitbit devices. From an app developer perspective, Google Play and the Fitbit App Gallery therefore provide access to a different customer group, i.e. to users of Wear OS devices and users of Fitbit devices, respectively.

(124) From a supply side perspective, in line with the Google Android case, the Commission notes that smart mobile device OEMs are unlikely to switch app stores, as they would need to switch to another licensable OS thereby incurring significant costs. The development costs can be substantial, making it unlikely that an OEM would change OS merely due to a degradation of the wearable app store. OEMs are also unlikely to do so because their users would incur costs when switching to a different OS and app store. These switching costs include the need to download and purchase existing apps for the new wearable OS, the need to learn and become familiar with a new interface and the need to transfer data through often inconvenient and imperfect mechanisms.71

(125) In light of recitals (117)-(124), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction in this Decision, the Commission considers that the relevant product markets are:

(a) The supply of app stores for a given OS platform of smart mobile devices (in particular Android app stores);

(b) The supply of app stores for a given OS platform of wrist-worn wearable devices (in particular app stores for Wear OS and Fitbit devices).

8.4.2. Geographic market definition

8.4.2.1.Commission precedents

(126) In Google Android, the Commission concluded that the geographic scope of the market for app stores for a given OS platform of smart mobile devices (for example Android app stores) is worldwide, excluding China.72 This conclusion was based on the fact that (i) there are no trade restrictions, (ii) language differences between different geographic areas do not appear to create obstacles for app store developers, and (iii) OEMs can sell smart mobile devices with the same app stores pre-installed in most regions of the world. At the same time, conditions of competition were found to be different in China because Google’s activities in China are limited and there are a number of OEMs active in China that have successfully developed and commercialised their own app store.

(127) The Commission has not previously considered a market for apps stores on wearable devices.

8.4.2.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(128) The Notifying Party considers that the exact scope of the relevant product markets can be left open, as no competition concerns would arise under any plausible market definition.73

8.4.2.3. The Commission’s assessment

(129) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication which would suggest that, in defining the relevant geographic market for app stores for smart mobile devices, it would be appropriate to deviate from its previous decisional practice for app stores for smart mobile devices of defining a worldwide market excluding China.74

(130) With regard to the market for app stores for wrist-worn wearable devices, responses to the market investigation suggest that there are no significant differences in customer demand and/or requirements between different EEA countries, however, that there are some significant differences across regions such as the EEA, North America and China.75 From the supply side, similar arguments as for app stores for smart mobile devices hold, i.e. (i) there are no trade restrictions, (ii) language differences between different geographic areas does not appear to create obstacles for app store developers, and (iii) OEMs can sell smart mobile devices with the same app stores pre-installed in most regions of the world.76 Nevertheless, competitive conditions and competitors’ market position can vary significantly by geographic region. In particular, conditions of competition were found to be different in China. For instance, on Wear OS devices sold in China, [Google’s licensing strategy]. Therefore, international developers may need to adapt [Google’s licensing strategy].77

(131) In light of recitals (129)-(130), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction, the Commission considers that the geographic scope of the markets for app stores for a given OS platform of smart mobile devices (for example Android app stores) and of wrist-worn wearable devices (for example Wear OS and Fitbit app stores) is worldwide excluding China.

8.5. Search services

(132) Google’s principal activity in online services is the provision of general search services through Google Search, its internet search engine. Google Search is offered to end users free of charge and is financed through online advertising. Users can access Google Search from a mobile or desktop browser, from an Android or iOS mobile app, or from a Wear OS app. While the user interface may vary depending on the type of device, the underlying technology is essentially the same.

(133) Fitbit does not provide search services.

8.5.1. Product market definition

8.5.1.1. Commission precedents

(134) Two main categories of search services have been considered in previous Commission decisions:

(a) general search services, which search the entire internet and therefore generally return different, more wide-ranging results;

(b) specialised search services, which focus on providing specific information or purchasing options in their respective fields of specialisation, also often covering a content category which is possible to monetise.

(135) In particular, in the Google Shopping and Google Android decisions, the Commission concluded that the provision of general search services constitutes a separate relevant product market.78

(136) The Commission found that general search services on static devices such as desktop and laptop PCs and on mobile devices belong to the same relevant product market due to supply-side substitutability.79

8.5.1.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(137) According to the Notifying Party, the product market for general search services should include the Google Search app on Wear OS devices.80

(138) However, the Notifying Party considers that, since the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the market for general search services can be left open.81

8.5.1.3. The Commission’s assessment

(139) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication that would suggest that it would be appropriate to depart from its previous practice finding a separate product market for the supply of general search services.82

(140) Responses to the to the market investigation indicate that users of search apps for wearable devices consider search apps on smart mobile devices as suitable alternatives83 and providers of software solutions for PCs and smart mobile devices would most likely be able to also offer search apps for wrist-worn arable devices, without incurring in significant investments, as the underlying technology is essentially the same.84

(141) The Commission did not investigate segmentations by further device type, that is the question if general search services on smart TVs, smart speakers or other (i.e. non- wrist-worn) wearable devices are part of the overall market as they are not relevant for the assessment of this Transaction. Fitbit is only active in the supply of wrist- worn wearable devices.

(142) Therefore, for the purpose of assessing the Transaction, the Commission considers that the relevant product market is the one for the supply of general search services.

8.5.2. Geographic market definition

8.5.2.1.Commission precedents

(143) In the Google Shopping and Google Android decisions, the Commission concluded that the market for the provision of general search services is national in scope.85

8.5.2.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(144) The Notifying Party submits that, as the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the market for general search services can be left open.86

8.5.2.3. The Commission’s assessment

(145) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication that would suggest that it would be appropriate to depart from its previous practice in relation to the geographic scope of the market for the supply of general search services.87

(146) Therefore, for the purpose of assessing the Transaction, the Commission considers that the geographic scope of the supply of general search services is national.

8.6. Online advertising services

(147) Google monetizes several of its services through the provision of online advertising space. Search ads make up the majority of Google’s ads business. Fitbit is not active in online advertising.

8.6.1. Product market definition

8.6.1.1. Commission precedents

(148) Four main categories of ads or advertising services have been considered in the Commission’s previous decisions:

(a) offline ads or advertising services, such as on newspapers, television, etc.;

(b) online search ads or advertising services, which are selected on the basis of search queries entered by users into internet search engines and are typically presented next to the search results on the search engine’s own pages or other search results pages;

(c) online non-search or display ads or advertising services on domains other than social networks (in the following “online display advertising off-social networks”), which can be either contextual ads, selected according to the content of the page on which they appear, or non-contextual ads;

(d) online non-search or display ads or advertising services on social networks (in the following “online display advertising on-social networks”).

(149) In previous merger decisions, the Commission considered the market for online advertising to be separate from offline advertising. It also considered possible further segmentations between online search and non-search advertising, between ads on social networks or off social networks, or on the basis of the platform (PC versus mobile), but it ultimately left the market definition open.88 In Google AdSense, the Commission concluded that online search advertising constitutes a separate relevant product market.89

8.6.1.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(150) The Notifying Party submits that, for the purposes of this case, it accepts the Commission’s conclusion in the AdSense decision that there exist separate product markets for online advertising, which can be further segmented into search and non- search advertising. Since the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible product delineation, according to the Notifying Party, the exact scope of the relevant product market can be left open.90

8.6.1.3.The Commission’s assessment

(151) The market investigation confirms that the market for online advertising is separate from offline advertising. The majority of respondents does not consider the market for offline advertising services as an alternative to online search or display advertising.91 A clear majority of respondents also considers that suppliers of offline advertising services could not develop and start offering online search advertising services or online display advertising services in the short term without incurring significant investments.92

(152) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication that would suggest that it would be appropriate to depart from its previous practice of considering online search and non-search advertising as separate markets.93 In the market investigation, several respondents mentioned that online search and non- search advertising complement one another as opposed to providing direct substitutes. In this respect, one respondent explained that “Search and Display each play unique roles in an advertiser's strategy. One defining characteristic about Search is that it is an interaction that is initiated by the end consumer. This is often indicative of consumer interest or intent and can be a powerful lever for driving ‘conversions’. Display advertising also tends to focus on ‘performance’ by balancing investment in ‘prospecting’ and ‘retargeting’ based on person (or device) level targeting. Advertisers can pursue this strategy on social networks or on the open internet”.94 Display and search advertising services appear to be also not substitutable from the supply-side. In particular, supplying online search advertising services requires building a successful search engine, which would be extremely costly and time consuming.95

(153) The Commission has also considered whether a segmentation according to the platform where the ad is delivered, namely desktop or mobile devices, may be appropriate. In particular, it cannot be excluded that building a mobile app or a website, on which the ads may be served or delivered, are very different processes. The question as to the relevance of the segmentation according to the platform where the ad is delivered can be left open, as it would not change the outcome of the competitive assessment in the present case.

(154) As regards online display advertising, the Commission has considered a segmentation between video and non-video advertising and advertising on- and off- social networks. In particular, in relation to the latter distinction, respondents to the market investigation indicated that the technology that powers each of these advertising services are different. Thus, expanding into a new advertising channel requires some investment.96 Also from the demand-side, it appears that all these possible markets/segments may be complementary outlets for ads, which advertisers consider when deciding how to spend their advertising budget. The question as to the relevance of the segmentation between video and non-video advertising and a possible segment of online display advertising off-social networks97 can be left open, as it would not change the outcome of the competitive assessment in the present case.

(155) In light of recitals (151)-(154), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction in this Decision, the Commission considers that the relevant product markets are those for:

(a) the supply of online search advertising services, potentially segmented in the supply of online search advertising services on desktops or on mobile apps;

(b) the supply of online display advertising services, potentially segmented in the supply of online display advertising services on desktops or on mobile apps, in the supply of online display advertising services off-social networks, and/or in the supply of online display video or non-video advertising services.

8.6.2. Geographic market definition

8.6.2.1 Commission precedents

(156) With reference to the geographic scope of the online advertising market and its possible segments, the Commission found in previous cases that they should be defined as national in scope or alongside linguistic borders within the EEA.98 In the Google AdSense decision, the Commission concluded that online search advertising constitutes a separate relevant product market, whose relevant scope is national.99

8.6.2.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(157) The Notifying Party submits that, as the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the geographic market for online search advertising can be left open. The Notifying Party did not provide any view as to the geographic scope of the other possible product markets within the supply of online advertising.100

8.6.2.3. The Commission’s assessment

(158) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication which would suggest that, in defining the relevant geographic market for online advertising (and segments thereof), it would be appropriate to deviate from its previous decisional practice.

(159) The majority of respondents to the market investigation considers that advertisers typically buy advertising space and conduct online advertising campaigns on a national basis. In the market investigation, respondents also stressed the importance of differentiation by language.101

(160) In light of recitals (158)-(159), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction, the Commission considers that the geographic scope of the relevant product markets identified in recital (155) above is national or alongside linguistic borders within the EEA.102

8.7. Ad tech services

(161) As outlined in Section 7.5, Google is not only active in the supply of online advertising services, but also as intermediary across the entire ad tech value chain. Fitbit is not active in this space.

8.7.1. Product market definition

8.7.1.1. Commission precedents

(162) In Google AdSense, the Commission concluded that online advertising intermediation constitutes a relevant product market separate from the direct sale of online ads and that it should be further sub-divided in a market for online search advertising intermediation services and a market for online non-search intermediation services.103 In Google/DoubleClick, the Commission considered a market for online display ad serving technology, which could be further segmented between services for advertisers and publishers.104 In its previous decisions, the Commission has not considered the most recent developments in the ad tech value chain.

8.7.1.2.The Notifying Party’s view

(163) The Notifying Party submits that, for the purposes of this case, it accepts the Commission’s conclusion in the AdSense decision that there exist separate product markets for online advertising intermediation, which can be further segmented into search and non-search advertising intermediation. Since the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible product delineation, according to the Notifying Party, the exact scope of the relevant product market can be left open.105

8.7.1.3. The Commission’s assessment

(164) The Commission notes that the intermediation services analysed in Google AdSense and Google/DoubleClick are likely to correspond to only a part of the ad tech value chain, which has over time evolved, expanded and increased its level of automatisation.

(165) In the market investigation, it was pointed out that various services currently provided in the ad tech value chain, such as DSP, SSP, ad exchange and ad server services, are all based on distinct technologies that pose unique challenges and serve a specific purpose.

(166) The results of the market investigation were inconclusive regarding the exact segmentation of online advertising intermediation services. Nonetheless, the evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication that would suggest that it would be appropriate to depart from its previous practice of considering search and non-search advertising intermediation services as separate markets. Furthermore, in view of the technical differences regarding the serving of search ads106 as opposed to display ads, not all the “ad tech” services seem to be relevant for search advertising. Accordingly, in relation to search ads the Commission has considered a market for intermediation services as in Google AdSense, which coincides with the supply of search ad network services. In relation to display ads, however, the Commission has considered a segmentation between (i) supply of SSP services; (ii) the supply of DSP services; (iii) the supply of ad network services; (iv) the supply of advertiser ad server and (v) the supply of publisher ad server services.

(167) Finally, for the purposes of assessing the Transaction, data services, and in particular data analytics services, are of particular relevance, both for online search and display advertising.

(168) In light of recitals (164)-(167), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction, the Commission considers that the relevant product markets are:

(a) The supply of search ad network services;

(b) The supply of display ads SSP services;

(c) The supply of display ads DSP services;

(d) The supply of display ad network services;

(e) The supply of display ads publisher ad server services;

(f) The supply of display ads advertiser ad server services and

(g) The supply of analytics services.

(169) The question of the relevance of the exact segmentation of advertising intermediation services according to services listed in recital (168) can be left open, as it would not change the outcome of the competitive assessment in the present case.

8.7.2. Geographic market definition

8.7.2.1. Commission precedents

(170) In Google AdSense, the Commission concluded that the market for online search advertising intermediation is EEA-wide in scope.107 In Google/DoubleClick, the Commission considered the market for online display ad serving technology, and segments thereof, as at least EEA-wide in scope.108 In its previous decisions, the Commission has not considered specifically the geographic scope of the other services in the ad tech value chain.

8.7.2.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(171) The Notifying Party submits that, as the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the geographic market for online search advertising intermediation can be left open. The Notifying Party did not provide any view as to the geographic scope of the other possible product markets within the supply of online advertising intermediation.109

8.7.2.3.The Commission’s assessment

(172) The evidence in the Commission's file has not provided any indication which would suggest that, in defining the relevant geographic market for the ad tech services, it would be appropriate to deviate from its previous decisional practice in relation to online search advertising intermediation and ad server services.

(173) In light of recital (172), for the purpose of assessing the Transaction in this Decision, the Commission considers that the geographic scope of the relevant product markets identified in recital (168) above is at least EEA-wide.

8.8. Health and fitness apps

(174) Google develops and maintains the Google Fit mobile app. The Google Fit app enables a user to access their Google Fit data on an Android or iOS smart mobile devices or a Wear OS wearable device.110 Google also offers a Wear OS mobile app that serves as a companion to a Wear OS device and enables a user to sync their Wear OS device and their Android or iOS smart mobile device.

(175) Fitbit provides the Fitbit mobile app that serves as companion app to Fitbit devices and enables users to view the activity tracked by their Fitbit device.111 The app does not pair with non-Fitbit wearable devices but third-party user data can be imported into the Fitbit mobile app. The Fitbit mobile app can be installed on an Android or iOS smart mobile device.112

8.8.1. Product market definition

8.8.1.1. Commission precedents

(176) The Commission has not previously considered a market for health and fitness apps.

(177) In previous Commission decisions, the Commission segmented product markets for apps based on (i) type (for example, productivity apps, communication apps, music recognition apps), and (ii) platform (for example, apps for PCs, smart mobile devices, or gaming consoles).113

8.8.1.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(178) The Notifying Party submits that health and fitness apps are a growing and varied category.114 According to the Notifying Party, health and fitness apps typically fall into four groups based on the aspect of user lifestyle or behaviour that they target: (i) activity and fitness; (ii) sleep; (iii) mental wellbeing; and (iv) nutrition. Some apps are specialised, focusing on one of these four groups; others are generalist, covering all four.

(179) In addition, health and fitness apps differ in whether they serve as companion app to a specific wearable brand. For example, the Fitbit mobile app is designed primarily as a companion to a Fitbit wearable device and enables the user to set up their Fitbit device, synchronize it with their smart mobile device and download apps for use on their Fitbit device. The analogous app for Wear OS devices is Google’s Wear OS mobile app. These apps are essentially extensions of the devices they support and do not compete with each other, since a Fitbit user would have no use for Google’s Wear OS mobile app, and a Wear OS user would have no use for the Fitbit app. In contrast, the Google Fit mobile app does not work as companion app to a specific device but collects data from various sources and users could transfer their Fitbit data to Google Fit.

(180) According to the Notifying Party, the major mobile app stores tend to group all of these apps together under the broad “health and fitness” category, and present them to users as such.

(181) The Notifying Party considers that, since the Transaction does not raise competitive concerns under any plausible market definition, the exact scope of the product market for health and fitness apps can be left open.

8.8.1.3 The Commission’s assessment

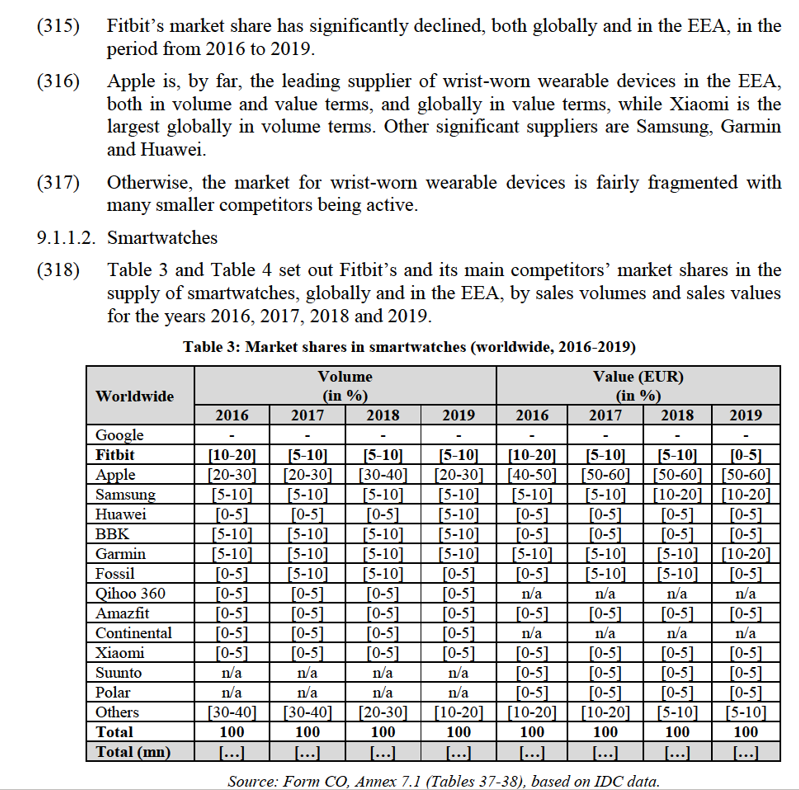

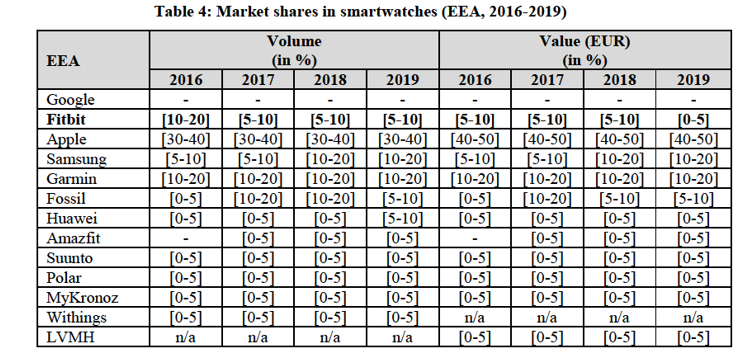

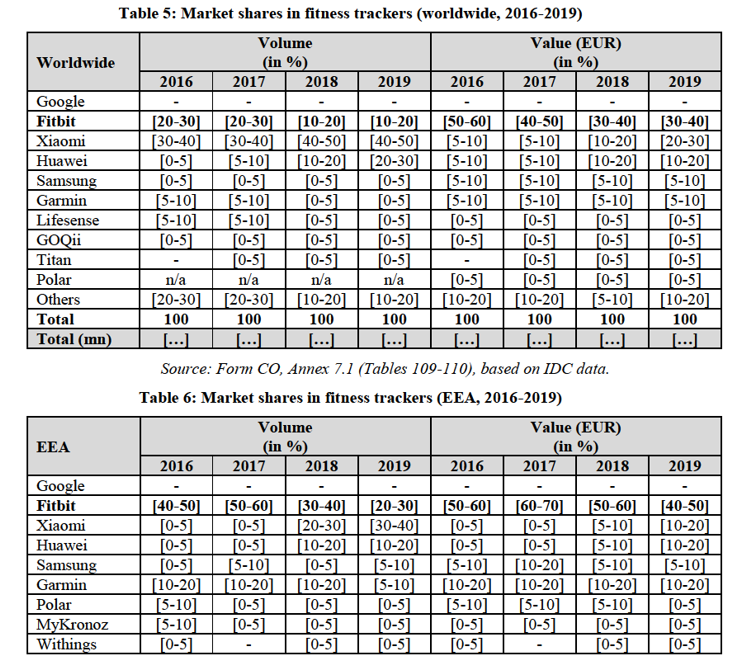

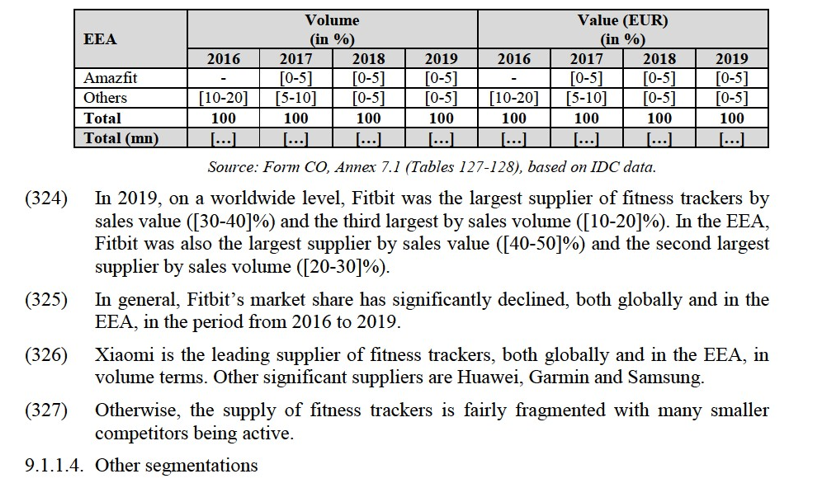

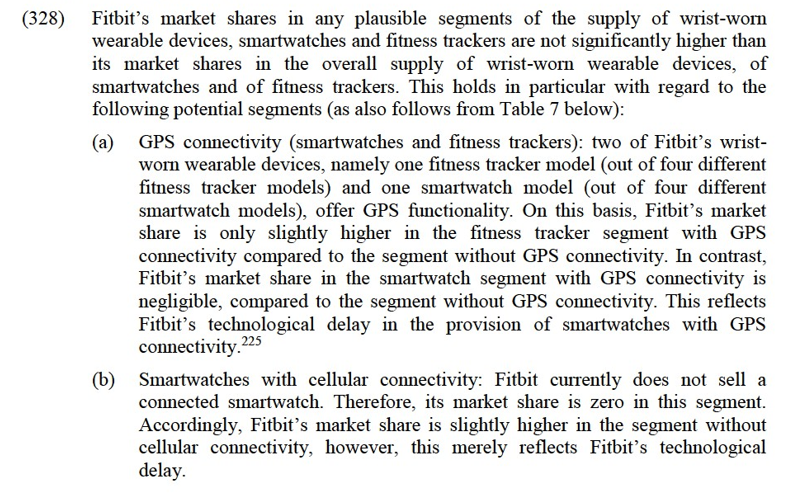

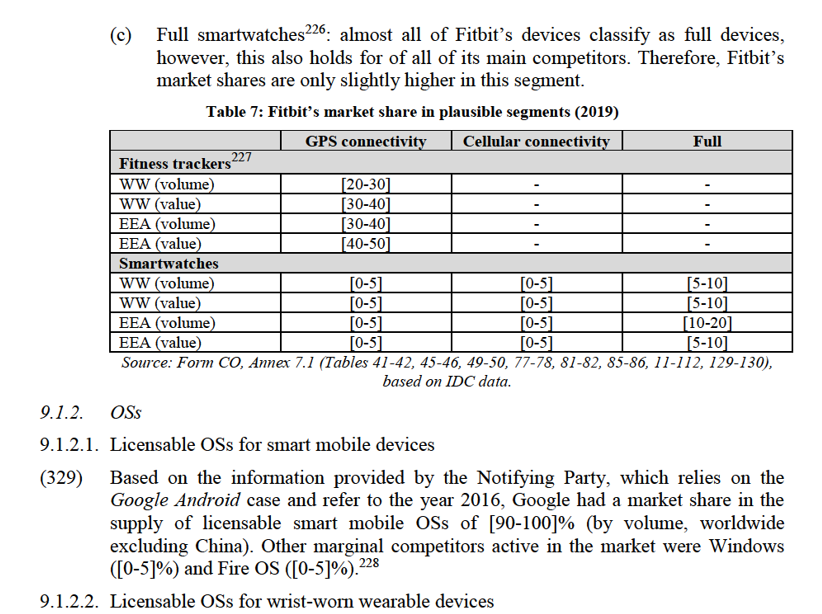

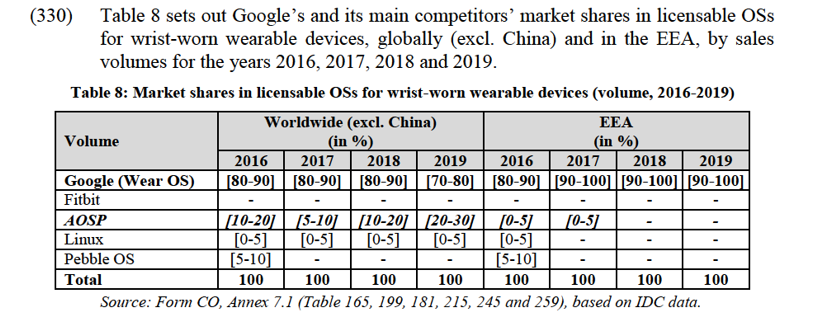

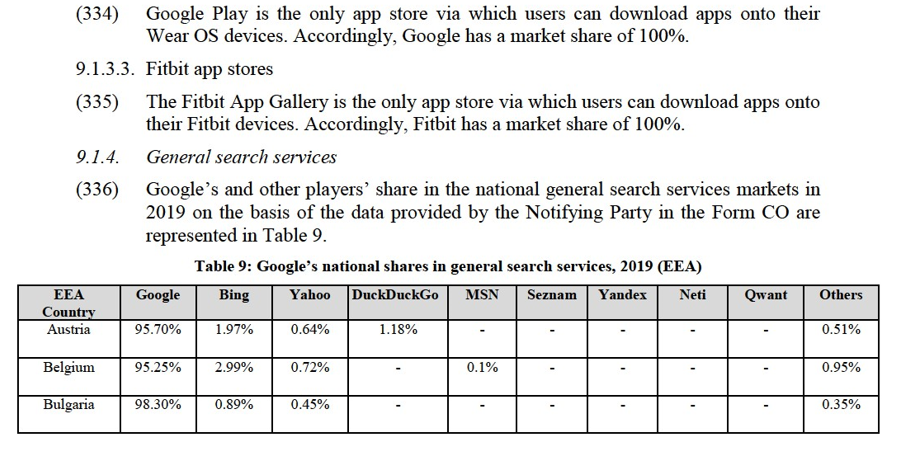

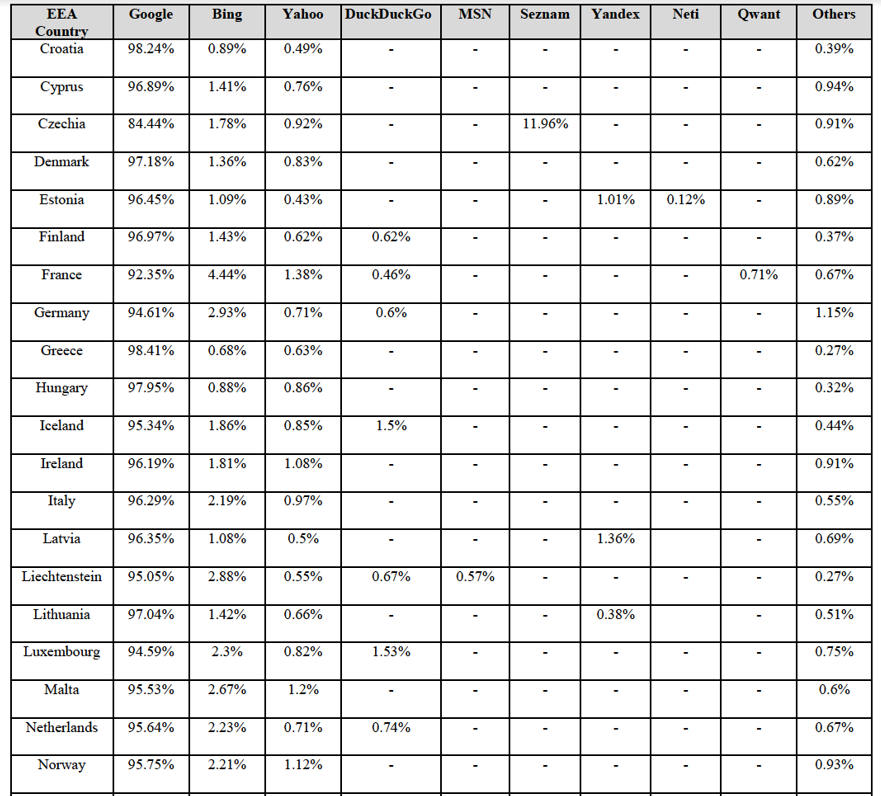

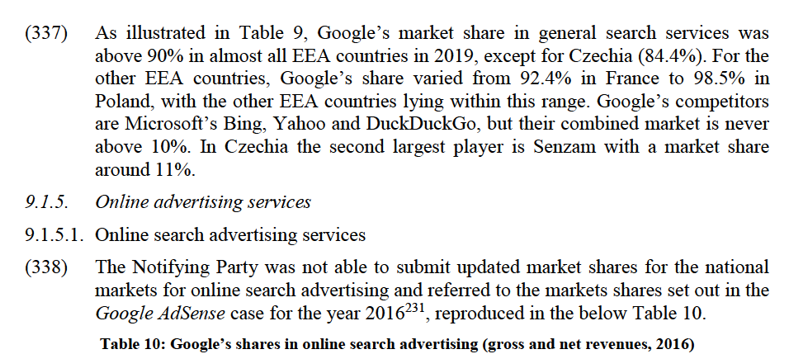

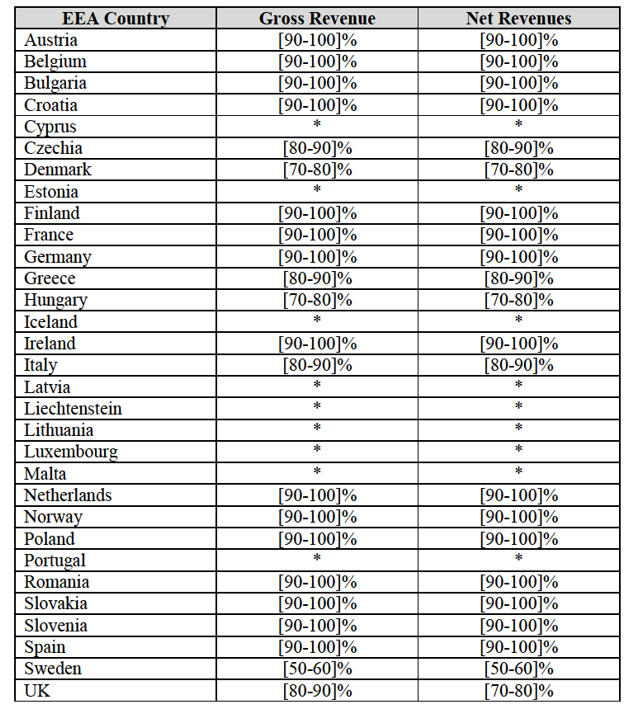

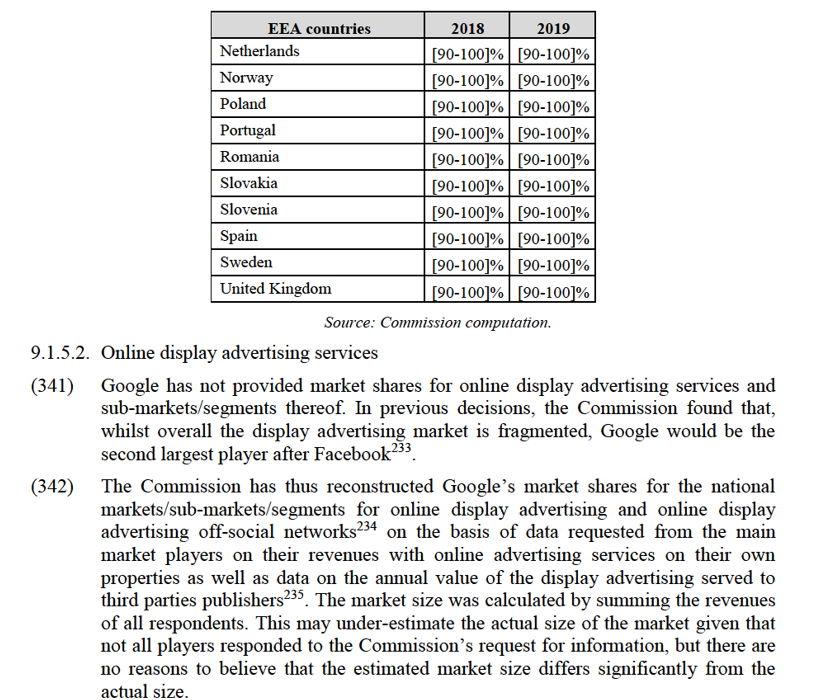

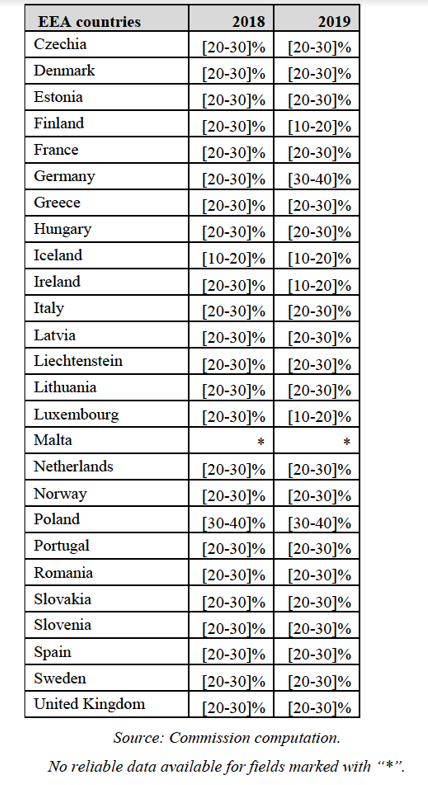

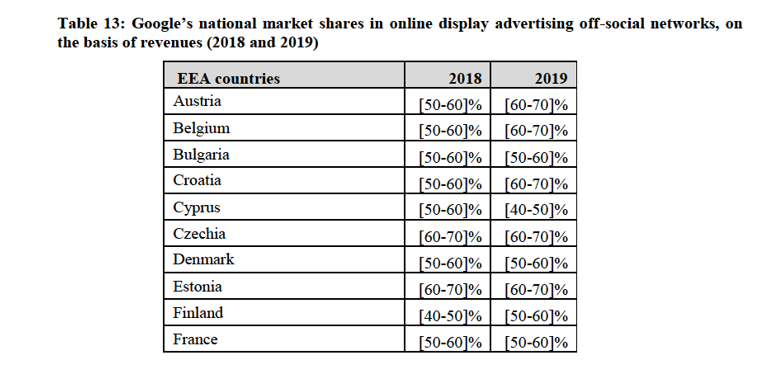

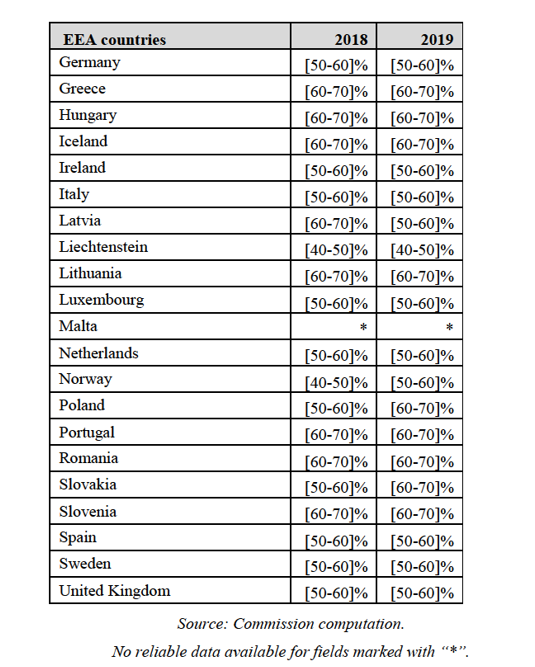

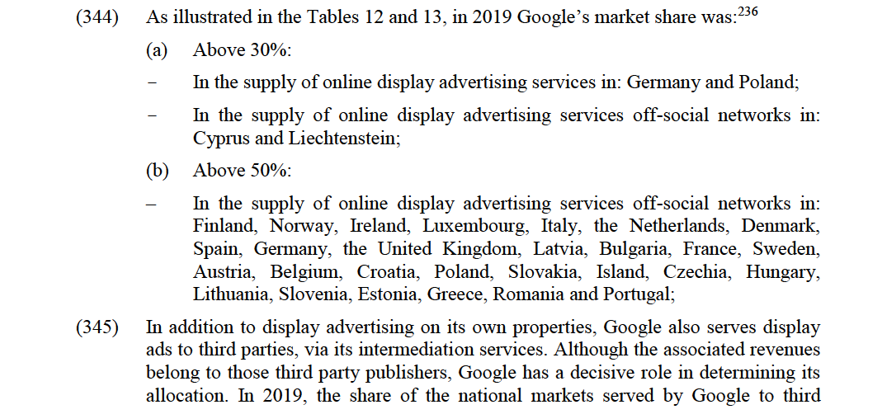

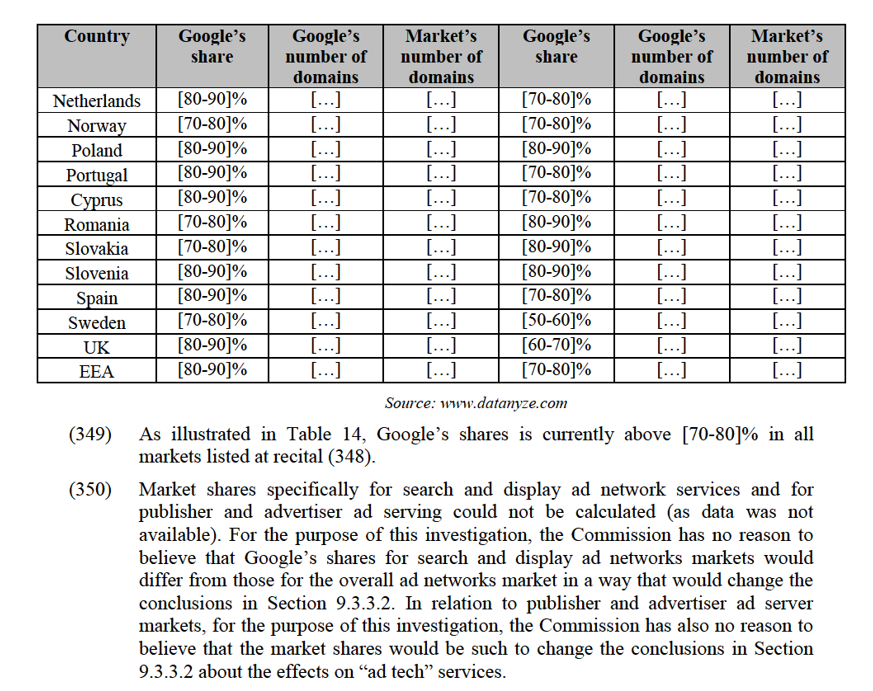

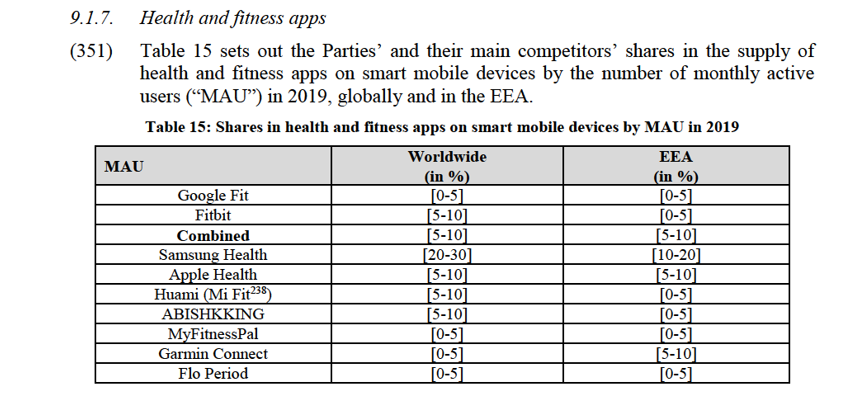

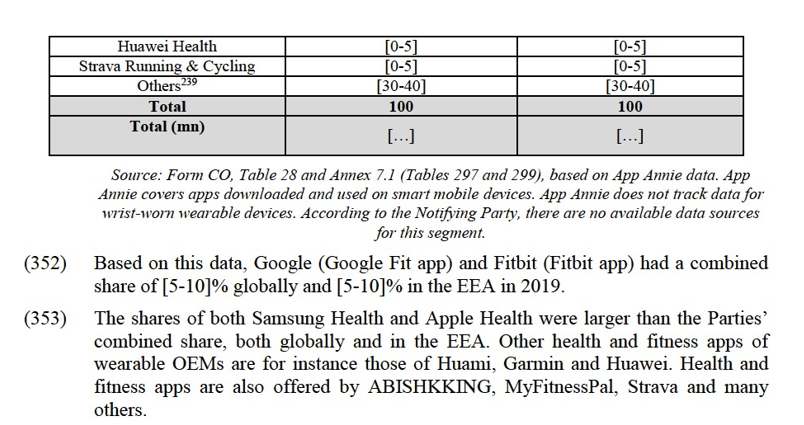

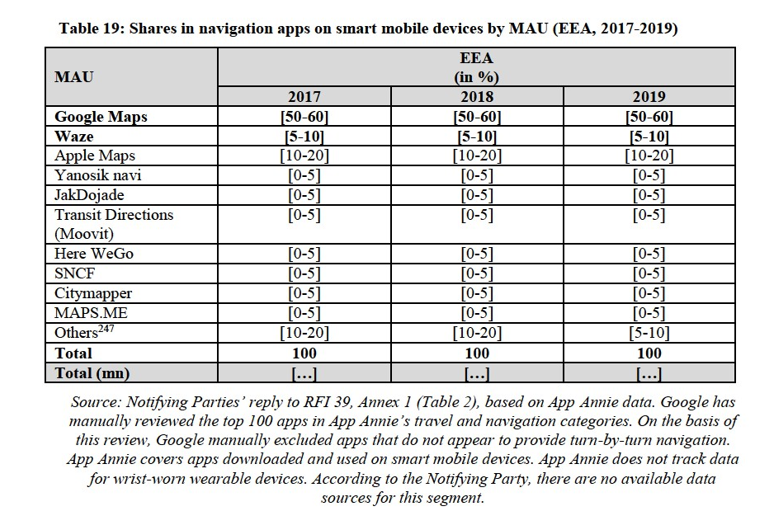

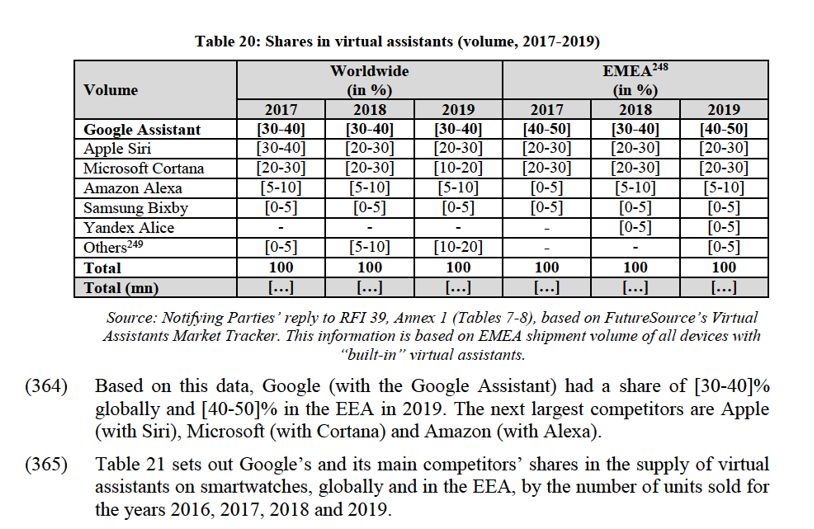

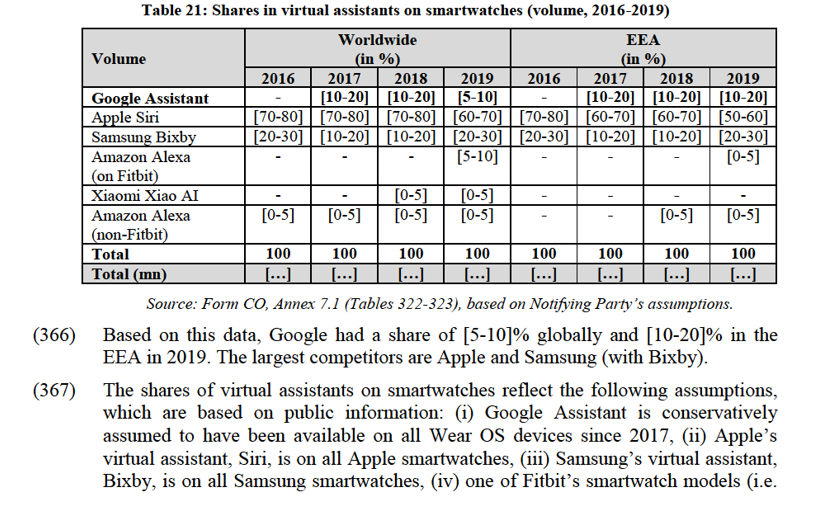

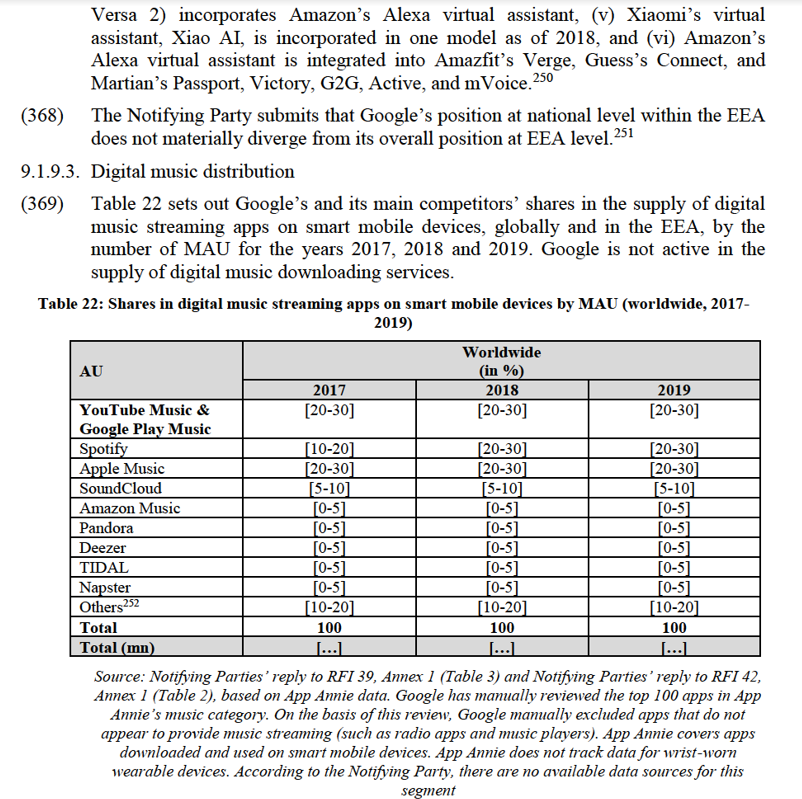

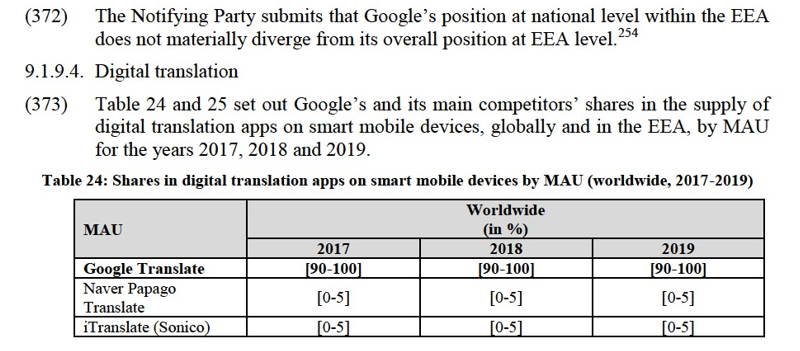

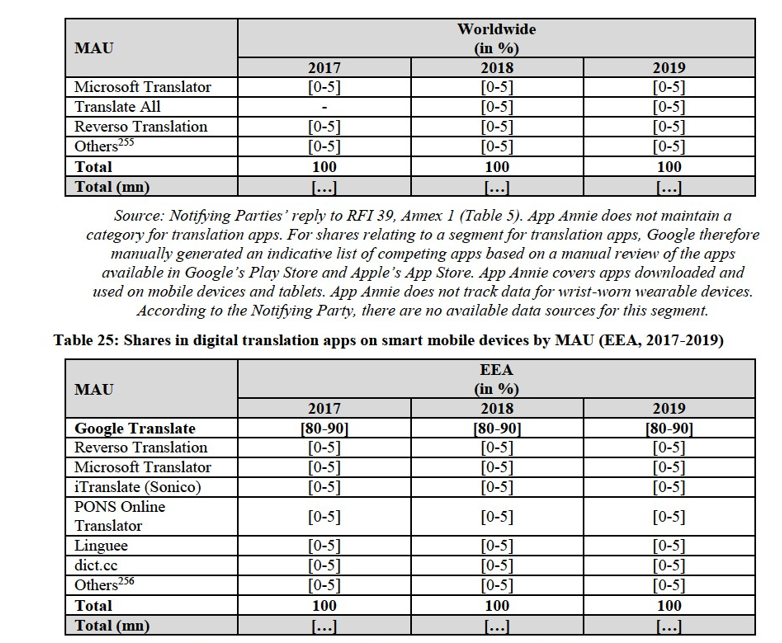

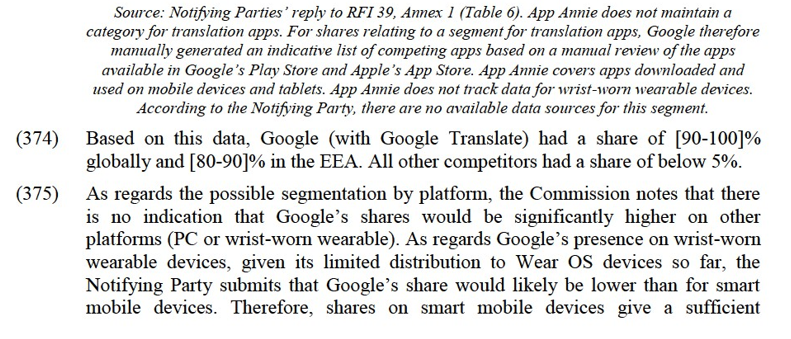

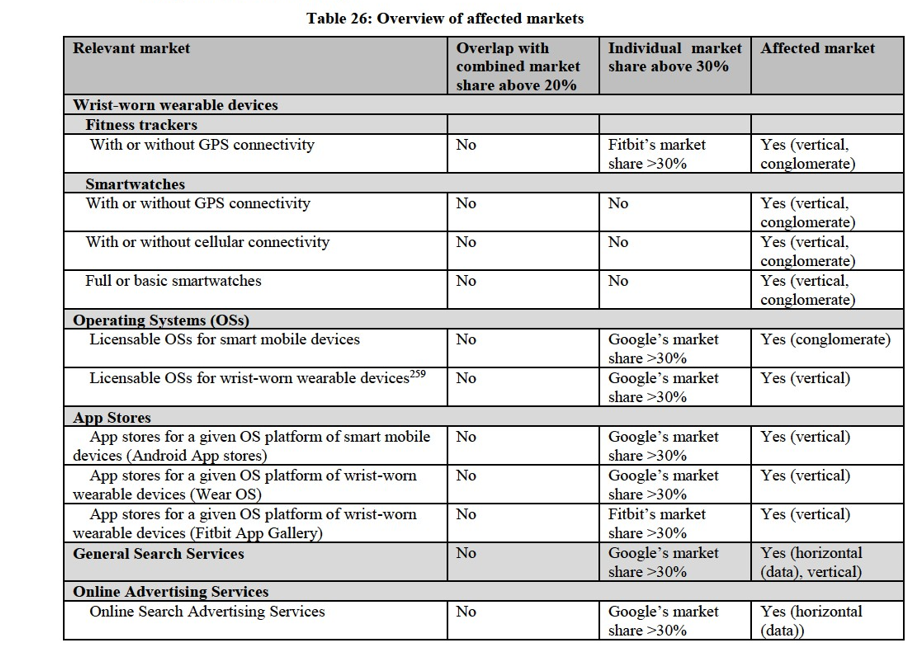

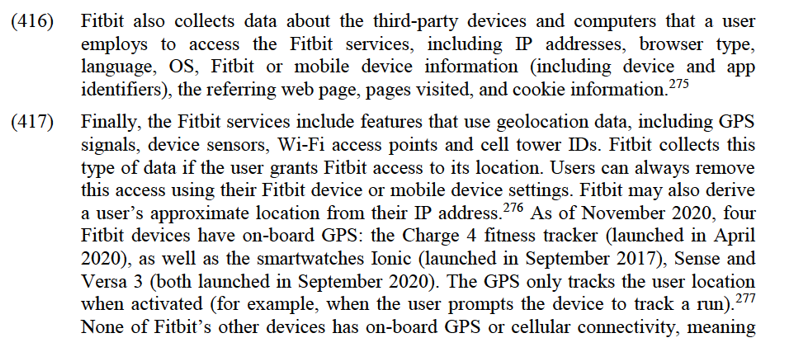

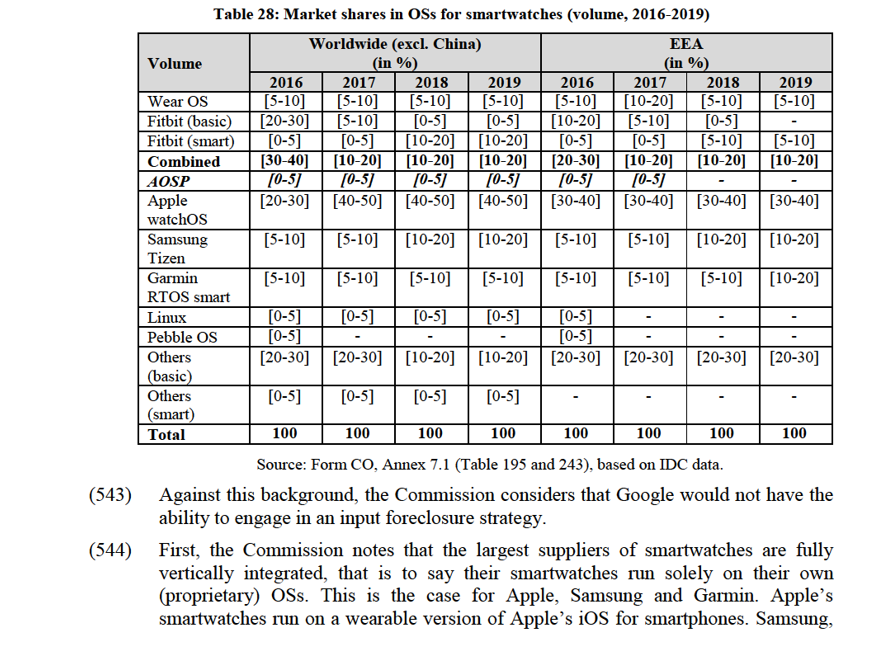

(182) With regard to the exact scope of the market for health and fitness apps, the evidence in the Commission's file is not conclusive. Respondents to the market investigation confirmed that health and fitness apps is a broad category in which there is a wide range of offerings with partially overlapping features.115 The results of the market investigation also highlighted the specific role of companion apps.