Commission, December 16, 2020, No M.9936

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

IMABARI SHIPBUILDING / JFE / IHI / JAPAN MARINE UNITED CORPORATION

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 11 November 2020, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation, by which Imabari Shipbuilding Co., Ltd. (‘Imabari Shipbuilding’, Japan) acquires, within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) and Article 3(4) of the Merger Regulation, joint control of Japan Marine United Corporation (‘JMU’, Japan) together with JFE Holdings Inc (‘JFE’, Japan) and IHI Corporation (‘IHI’, Japan). The proposed acquisition takes place by way of purchase of shares (the ‘Transaction’).3 Imabari Shipbuilding, JFE, IHI and JMU are together referred to as the ‘Notifying Parties’. Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU are together referred to as the ‘Parties’ or as the ‘Merged Entity’.

1. THE PARTIES

(2) Imabari Shipbuilding is active in the development, design, construction, marketing, and repair of a wide range of commercial vessels, including bulk carriers, container ships, car carriers, LNG carriers, tankers and ferries.

(3) JMU is active in the development, design, construction, production and marketing of a wide range of commercial and military vessels, including bulk carriers, container ships, car carriers, LNG carriers, tankers, ferries and offshore support ships. JMU is currently jointly controlled by JFE Holdings Inc. (‘JFE’, Japan) and IHI Corporation (‘IHI’, Japan). Each of JFE and IHI currently holds 49.4% of JMU.

(4) JFE is a holding company with interests in steel, engineering and the trading of raw materials, machinery, electronics, real estate and food.

(5) IHI is a heavy-industry manufacturer with activities in (i) resources, energy and environment; (ii) social infrastructure and offshore facilities; (iii) industrial systems and general-purpose machinery; and (iv) aero engine, space and defence.

2. THE OPERATION AND THE CONCENTRATION

(6) Pursuant to a Capital and Business Alliance Agreement executed on 27 March 2020, Imabari Shipbuilding will acquire 30% of the common shares in JMU. Post-closing the shareholding in JMU will be divided as follows among the three shareholders: JFE (35%), IHI (35%) and Imabari Shipbuilding (30%).

(7) According to the Notifying Parties’ governance arrangements, [Parties’ Arrangements]. However, the Notifying Parties submit that they will hold at least de facto joint control over JMU as a result of the proposed concentration.4

(8) Joint control may be acquired on a de facto basis where ‘strong common interests exist between shareholders to the effect that they would not act against each other in exercising their rights in relation to the joint venture’.5 In the present case, the Shareholders’ Agreement entered into between the Notifying Parties provides for a [Parties’ Arrangements]. Such a system is designed to enable the parent companies to exercise joint control ‘even in the absence of explicit agreements granting veto rights’.6

(9) In addition, de facto joint control may arise as a result of ‘a high degree of mutual dependency as between the parent companies to reach the strategic objectives of the joint venture’, notably ‘when each parent company provides a contribution to the joint venture which is vital for its operation’.7 In the present case, each of JFE and IHI have committed to provide [Financial situation]. This is particularly important in view of [Financial situation]. Conversely, Imabari Shipbuilding will contribute its technical and operational capabilities to JMU, as well as its in-depth knowledge of the shipbuilding industry, whereas JFE and IHI have not been engaged in the shipbuilding business for several years on their own. Hence, in addition to the relevant governance mechanisms, it can be reasonably expected that in practice JMU’s strategic matters will be determined in a cooperative manner among JFE, IHI and Imabari Shipbuilding, in view of the mutual dependence created by their respective contribution to the joint venture.

(10) The particular contribution of Imabari Shipbuilding and the strong common business interests and related dependencies between the Notifying Parties are specifically supported in the present case by the creation of a joint venture (‘the Design and Sales JV’) between Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU, pursuant to a JV agreement dated 27 March 2020. Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU will own 51% and 49% of the Joint Venture’s share capital, respectively. Since Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU will have equal rights regarding the nomination of the representatives in the management bodies including the Board of Directors, which is to decide on the budget, business plan and major investments, they will exercise joint control over the Design and Sales JV.

(11) The Design and Sales JV will carry out the design of commercial ships, negotiate the terms including the ship prices with the customers, sell the ships to the customers and conduct all sales activities as its own business. It will have its own resources as IS and JMU will transfer their respective sales and design departments (including staff) to the Design and sales JV.

(12) The acquisition of a 30% interest in JMU by Imabari Shipbuilding and the creation of the Design and Sales JV are interdependent in such a way that one transaction would not be carried out without the other. They are linked by condition in the Capital and Business Alliance Agreement and therefore form a single concentration. Moreover, according to internal documents, [Transaction structure]. Therefore, the current JMU shareholders appear to be in fact the undertakings concerned on JMU’s side behind the creation of the Design and Sales JV between Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU, within the meaning of paragraph 147 of the CJN.

(13) Consequently, JMU will be jointly controlled by Imabari Shipbuilding, JFE and IHI. JMU is and will continue to be a full-function joint venture within the meaning of Article 3 (4) of the EUMR. The operation thus constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

3. EU DIMENSION

(14) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate worldwide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (Imabari Shipbuilding: EUR [Turnover] million; JMU: EUR [Turnover] million; JFE: EUR 30 872 million; IHI: EUR 11 497 million).8 Two of them have an EU-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Imabari Shipbuilding: EUR [Turnover] million; IHI: EUR [Turnover] million), but they do not achieve more than two-thirds of their aggregate EU-wide turnover within one and the same Member State. Therefore, the notified operation has an EU dimension within the meaning of Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. MARKET CHARACTERISTICS

(15) This transaction pertains to the shipbuilding industry. The size and dimensions of commercial vessels are expressed in a range of different metrics, such as deadweight tonnage (‘DWT’, a measure for how much weight a ship can carry), gross tonnage (‘GT’, a vessel’s total cargo carrying capacity) and compensated gross tonnage (‘CGT’, derived by multiplying the gross tonnage of a ship with a coefficient reflecting the work content of each type and size of ship – therefore also an indicator of the relative output of merchant shipbuilding activity).9 In the present case, CGT represents the most appropriate metric for calculating market shares as it enables a more accurate macro-economic evaluation of shipbuilding workload.

(16) A number of additional metrics are used with respect to certain types of commercial vessels, such as container ships and PCTCs. Container ship capacity is customarily provided by reference to the maximum number of Twenty Feet Equivalent Units (‘TEU’ – a measure for one standard 6.1 meters long container) that a vessel can carry. PCTC capacity is also sometimes presented by reference to car equivalent units (‘CEU’).

(17) In line with previous Commission decisions,10 the relevant time-period to calculate market shares in the present case has been considered to be five years (i.e., 2015- 2019). Market shares over a five-year period allow for a more stable overview of the competitive landscape in view of the lumpy demand characteristic of the industry and the resulting significant fluctuations in yearly market shares. Nonetheless, the Notifying Parties have also provided data on the basis of shorter time periods (three years), in addition to yearly data.

(18) While it would likely be most appropriate to consider market shares by contracting dates (as competition takes place in the market place right before customers place orders for new ships), the Notifying Parties were only able to provide complete market share data by delivery date of ships. This information is based on data from Clarksons Research (‘Clarksons’), a provider of intelligence for global shipping.11 Among other metrics, Clarksons also tracks global ship orders, shipbuilding and fleet sizes. Therefore, for the purposes of this decision, the Commission will rely on 2015-2019 market shares based on ship deliveries. Where available, information based on contracting date will be taken into account in the assessment.

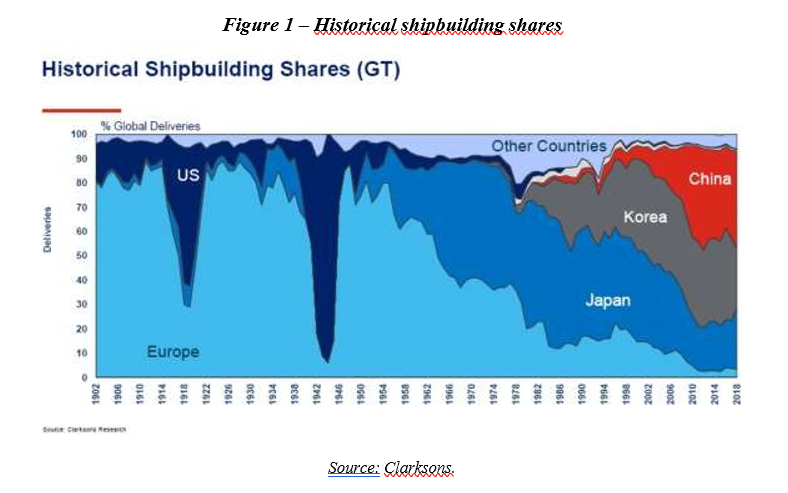

(19) The proposed Transaction takes place in a wider industry context characterised by the leading role of Asian shipbuilders in commercial shipbuilding.12 The Japanese share of global deliveries grew after World War II while Europe’s share declined. Today, the global commercial shipbuilding industry is largely concentrated in three countries: China, Korea and Japan (as shown in Figure 1).

(20) In recent years, measures have been adopted to make commercial ships more environmentally friendly. In 2013, the International Maritime Organization (‘IMO’ – a United Nations agency) adopted measures to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases from international shipping. Along with certain intermediary steps, the IMO set the goal to reduce the total annual greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50% by 2050. The shipbuilding industry is therefore increasingly seeking new approaches to reduce emissions (such as design and technical measures, operational measures or the development of alternative fuel technologies such as LNG-powered vessels).

5. MARKET DEFINITION

(21) The Parties’ activities overlap horizontally in commercial shipbuilding, specifically for container ships, bulk carriers, PCTCs and Roll-on roll-off carriers (RORO), LNG carriers, ferries and tankers. Conversely, the horizontal overlap in the repair of commercial ships,13 on the one hand, and vertical relationships between the Parties,14 on the other hand, are extremely limited and do not warrant particular investigation.

5.1.Product market definition

(22) In previous decisions, the Commission identified separate markets in the shipbuilding industry between merchant/commercial/civil ships and naval/military ships. Such a distinction is warranted due to differences in characteristics, performance, use and prices, as well as distinct customer bases, naval vessels being ordered by national governments as opposed to private customers for commercial ships.15 This segmentation was also endorsed by a vast majority of respondents to the market investigation.16

(23) Within commercial ships, the Commission considered further sub-delineations according to the main categories of vessels including: (i) bulk carriers; (ii) container ships; (iii) product carriers17; (iv) chemical and oil tankers; (v) liquefied natural gases (‘LNG’) carriers; (vi) liquefied petroleum gas (‘LPG’) tankers; (vii) roll-on roll-off vessels; (viii) ferries; (ix) cruise ships; and (x) offshore/specialised vessels.18 The Notifying Parties also present the Parties’ activities based on this segmentation (as well as PCTCs).19

(24) A large majority of customers and competitors having responded to the market investigation agreed that this segmentation according to the different cargo profile of commercial ships remains appropriate.20 Accordingly, this Decision relies on such segmentation as the starting point of competitive assessments and focuses on the three areas in which the Parties’ activities result in affected markets (container ships, bulk carriers and PCTCs).

(25) While the Parties’ activities also overlap in RORO carriers, LNG carriers, ferries and tankers, no plausible affected markets arise with respect to these ship types and it therefore can be reasonably excluded that the Transaction could raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market in relation to the construction and supply of these ship types.

(26) RORO carriers: RORO carriers are ships designed to carry wheeled cargo, such as cars, trucks, semi-trailer trucks, trailers, and railroad cars, etc. that are driven on and off the ship on their own wheels. In light of the low combined market shares of the Parties in ROROs overall of [0-5]% (IHS data, 2015-2019, by CGT) and the fact that JMU only built [Number of ships] and Imabari only [Number of ships] RORO vessels in the 2015-2019 timeframe, no plausible affected market arises.

(27) LNG carriers: the Notifying Parties submit that LNG carriers are ships with a standard cargo capacity of 80 000 – 180 000 cubic metres that exclusively transport liquefied natural gases. In light of the low combined market shares of the Parties in LNG carriers overall of [0-5]% (IHS data, 2015-2019, by CGT) and the fact the Imabari Shipbuilding only built [Number of ships] and JMU only [Number of ships] LNG carriers in the 2015-2019 timeframe, no plausible affect market arises.

(28) Ferries: the Commission has considered a distinction between (i) day ferries, (ii) night ferries, and (iii) cruise ferries.21 In ferries overall, the Parties have a combined share of [0-5]% (IHS data, 2015-2019, by CGT). The Parties only produce night ferries. The Notifying Parties submit that considering only night ferries, the combined market share of the Parties would be very unlikely to exceed 20%, given that in the timeframe 2015-2019 JMU only built [Number of ships] and Imabari Shipbuilding only built [Number of ships] night ferries.22

(29) Tankers: the Commission has previously left open whether chemical/oil tankers and product tankers should be considered as forming one single product market noting that there was some demand side substitutability between these two categories of tankers.23 In light of the low combined market shares of the Parties in tankers overall of [0-5]% (IHS data, 2015-2019, by CGT) and the fact that [Number of ships] of Imabari’s [Number of ships] tankers built in the timeframe 2015-2019 had a capacity of 25-54 999 kt, a size category of tankers in which the Parties’ combined share is only [0-5]%, no plausible affected market arises.

5.1.1. Construction and supply of container ships

(30) Container ships are commercial vessels that carry cargo in containers. They are used for the shipping of non-bulk cargo like manufactured goods as the use of containers allows for efficiency in loading and unloading the ship. A container ship’s capacity is measured in TEU, with the capacity of ships ranging from 100 TEU to over 23 000 TEU. Figure 2 below illustrates a Neo-Panamax 12-14 000 TEU container ship.

5.1.1.1. Notifying Parties’ arguments

(31) As the Commission has not in previous decisions distinguished between different sizes and cargo capacities of container ships, the Notifying Parties submit that the relevant market is the market for the construction, production and sale of container ships overall.24

(32) The Notifying Parties state that container ships should not be further segmented, notably according to categories used in Clarksons publications, in part because they submit that there is no common understanding as to how the various ship size categories should be defined.25

(33) The Notifying Parties further submit that from the demand side perspective, the container ship size depends on the number of containers to be transported and the routes and harbours to be serviced. They explain that for example Neo-Panamax container ships are able to pass the New Panama Canal whereas Post-Panamax ships are not able to pass it but have a higher loading capacity. Nevertheless, the Notifying Parties submit that many ship owners order container ships of different sizes, in particular customers that provide the full range of services from intercontinental routes to intra-regional routes. Customers that only service intra-regional routes however only order smaller container ships.26

(34) From a supply side perspective, the Notifying Parties argue that the range of the ship sizes that a manufacturer can built is determined by the physical constraints of its shipyard (such as dock size). In particular, with respect to Asian shipbuilders, which the Parties regard as their significant competitors, the Notifying Parties submit that they are capable to produce the whole range of container ship sizes.27

5.1.1.2. Commission’s assessment

(35) Responses to the market investigation confirm that container ships likely are a type of vessel distinct from other merchant/commercial/civil ships and other cargo vessels in particular.28

(36) Contrary to the submissions made by the Notifying Parties, the results of the market investigation also suggest that it is appropriate to further segment the market for container ships, notably by size.

(A) Market participants have a common understanding of container ship categories

(37) Contrary to the submission by the Notifying Parties, market participants appear to have a common understanding of different container ship categories based on size (delineated by TEU capacity in particular). This holds specifically for categories reported on by industry publication Clarksons Research, namely: Feeder (<3 000 TEU), Intermediate (3-7 999 TEU), Neo-Panamax (8-11 999 TEU), Neo-Panamax (12-14 999 TEU), and Post-Panamax (15 000+ TEU). A majority of customers and competitors expressing their opinion submit that these categories are regularly relied upon in interactions between shipbuilders and customers.29 While one customer states that ‘[t]he size categories seem to be unrelated to the interactions between shipbuilders and customers’,30 another customer explains that these ‘categories refer[…] to the typical classification in the shipping industry when shipbuilders interact with their customers’.31 A further customer agrees and submits that these ‘definitions are very common in the market recognized by most majority of the people involved in the industry’.32 Yet another customer says that ‘[s]ubject to vessel design and trade requirements, proposed category looks reasonable and corresponds to common industry practice’.33 Competitors agree, with one stating that ‘[t]hese categories are usually used in discussions with customers, classification societies, etc.’34 and another one calling them ‘[w]orld standard’.35

(38) Elaborating on which categories of container ships can be considered distinguishable from others due to factors such as price, performance, size and manufacturer/customer base, a customer submits that ‘[a]ll categories of container vessels are distinguishable from each other due to factors such as capacity, price, performance etc.’.36 Another customer states that ‘[s]ize and TEU is the most ideal categorization of container vessels’.37

(39) It therefore appears that the categorisation of container ships according to size categories based on TEU capacity used by Clarksons is widely recognised in the industry and relied upon in exchanges between market participants. In order to establish whether these categories could form the basis for distinct container ship product markets, the extent of supply and demand side substitutability is assessed in the following sections.

(B) No demand side substitutability between different container ship categories

(40) Generally, it appears that customers procure containerships of a specific size for different needs, and in particular for service on specific routes. Utilising other size container ships would in most cases not be cost-efficient for the shipping company.

(41) A majority of customers and competitors who expressed an opinion in response to the market investigation consider that shipping companies cannot use various categories of container ships to carry out the same types of services at competitive conditions.38 While one customer submits that ‘[i]nstead of having bigger vessels with less frequency, customer may want more frequent service offered by the fleet of the smaller vessels’,39 another customer in this context explains that ‘[i]n order for a shipping line to design and utilize its network, it must deploy the suitable vessels (in terms of size) on a given trade, corridor or string. Using smaller or larger vessels than set out in the network does generally not make sense for a shipping line, as it would not be cost efficient. Moreover, the deployment of vessels must take into account size restrictions in ports’.40 Another customer states that ‘[u]sually, shipping companies try as much as possible to use the same categories of container ships on the same service. For instance, using a feeder on larger trades will not be competitive enough’.41 Another customer describes the distinct use of different sizes of container ships by stating that ‘[b]igger ship goes back and forth bigger ports in fixed schedule, smaller ships go to smaller ports in a more flexible way’.42 A competitor submits that shipping companies ‘adapt the size of [the] vessel to the route to optimize costs’.43

(42) It therefore appears that different sizes of container ships address different (route) needs of shipping companies. This is further confirmed by a customer stating that it ‘uses different sizes of container vessels for different needs. Such needs will primarily be determined by global customer demand for shipping services, the structure of our global network, and vessel size restrictions etc. in ports’.44 Another customer closely mirrors this assessment and submits that it ‘uses different categories of container ships to address the specific needs of each trade. Different size and categories of vessels are used depending on the trade so as to adapt to the port facility, to the market, and to keep competitiveness’.45 This is further illustrated by another submission by a customer, that states that ‘[f]or example, the feeder size vessel would be placed in intra-Asia route as connecting vessel. On the other hand, the Post-Panamax containerships can only be placed in Far East to Europe trade, not only because of trade volume but also because only terminals along this trade route have the ability to handle the Post-Panamax containership’.46

(43) The circumstance that certain types of container ship categories are used for specific routes by shipping companies appears to be most pronounced with respect to Post- Panamax container ships, which are utilised for East Asia-Europe routes. Post- Panamax ships cannot pass through the Panama Canal and therefore cannot be utilised on routes leading through the Panama Canal. Neo-Panamax container ships appear to be used on a greater number of routes, such as Asia to America, but also Asia to Europe47. Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships are the largest category of container ship that can pass through the Panama Canal. Shipping companies would generally not utilise smaller vessels than those capable to service the largest share of demand on a given route while adhering to the size limitations of ports and canals along the route.

(44) It therefore appears that there is little demand side substitutability between container ships of different sizes.

(C) Limited supply side substitutability between different container ship categories

(45) Based on the responses to the market investigation, it appears that most shipbuilders active in the manufacture and supply of container ships are not active in the manufacture and supply of all size categories of container ships as identified by Clarksons. It further appears that shipbuilders active in certain size categories of container ships could not readily shift into building also other (in particular larger) size categories and customers have reservations with respect to purchasing large ships from shipbuilders without a track record in such ships.

(46) Considering whether shipbuilders active in container ships are typically able to build a wide range of container ship categories, a large majority of customers expressing their opinion does not consider all shipbuilders of container ships able to do so, but only some.48 Also, a majority of competitors expressing their opinion does not consider all shipbuilders of container ships able to build a wide range of container ship categories.49 With respect to their own activities in container ships, a majority of competitors states that they do not build all categories of container ships.50 In this context one competitor states that ‘a 20,000TEU container ship has a length overall of 400 meters and c[a]nnot be built at the dock of [the Company’s] shipyard’.51 Another competitor explains that its ‘shipyard [does not have] know how for large size container vessel[s]’.52 Yet another competitor says that it ‘could build all containerships of all categories mentioned above, but [it] would build specific category of containerships considering facilities and manpower for price competitiveness’.53

(47) Overall, however, the size of a given container ship appears to be the main factor determining whether a shipbuilder active in container ships is capable of building it according to the quality standards expected by customers. Larger container ships require larger docks and related infrastructure, but also different and more elaborate design and engineering capabilities.

(48) A customer explains that ‘to build big containers ships request shipbuilder investing on the building facilities as dock, pier crane and so on. On the other hand, the experiences as design ability, qualified work labor availability also limit some container producer to build big container ships’.54 Another customer states that ‘larger container vessels (+10,000 TEU) require detailed technical design capabilities as well as drydocks of suitable sizes. Some container vessels are built with special features, such as waste heat recovery systems, complex electrical control systems and potentially use of alternative fuels, including LNG – all require experience from the yard for quality installation and economic viability’.55 An additional customer submits that the ability of a shipbuilder to construct a certain category of container ship depends ‘on size and facility of [the] Shipyard [and on] design [and] technology’.56 Another customer says that ‘[a]ny shipbuilder of container ships has a specific equipment/infrastructure, know-how based on the past record, and facilities which enable to produce the specific size most efficiently. The small-scale yard cannot produce the large size physically. Therefore, they basically produce specific size or particular range of container ships’.57

(49) The limited supply side substitutability seems to be especially pronounced with respect to large container ships. Market participants contend that only some players active in the construction of container ships are capable of building large container ships. This appears to be particularly the case for Post-Panamax, and to a lesser extent, for Neo-Panamax container ships. A customer submits that ‘[o]nly a few of big shipbuilders can build 15,000+ TEU type container carrier’.58 Another customer explains that shipbuilders tend to focus either on ships over 10 000 TEU capacity or under 5 000 TEU capacity.59 Yet another customer ‘differentiates shipyard that build small ships (up to 5000teus), shipyards that build medium size, and shipyards that can build Ultra Large Container Ships (ULCS)’.60

(50) Irrespective of the exact size and/or category that distinguishes the large container ships from smaller container ships, there appears to be fewer capable shipbuilders active in large container ships. This is also confirmed in the market shares provided by the Parties. These suggest that at least 22 shipbuilders were active in container ships overall between 2015 and 2019, while only seven were active in the category of Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships. A customer summarises the reason for this by stating: ‘Building mega ship requires high-end production, infrastructure, design capability and large scale capital. [The Company] believes only limited shipbuilders are able to build ultra-large vessels’.61

(51) Market participants also generally describe shipbuilders as not able to shift easily from building only smaller container ships to also building large container ships.62

(52) While one competitor states that ‘[i]f there are enough facilities and manpower, there’s no big barrier for shipbuilders to expand into building larger size containerships’,63 another one describes the ‘[c]apacity of facilities, such as dock size [and] crane capacity’64 as barriers. Another competitor also points to ‘workers’ quality’ as an aspect to be ‘prepared for larger construction works’.65

(53) A majority of customers expressing their opinion submit that they would not order large container ships from a shipbuilder with experience in building smaller container ships.66 A customer explains this by saying that ‘[s]hipyards tend to specialize on certain vessel types/size and therefore [the Company] would not purchase a ULCS from a shipyard specialized in building small container ships’.67 Another customer submits that ‘[t]here is [a] technical and infrastructure gap when the vessel size exceeds certain limit. Therefore, [the Company] will consider whether the technical and infrastructure capability of potential shipbuilders can match its requirement. Yet […] only limited supplier[s] can build mega ships in the market. Therefore, when [the Company] intends to order mega ships, it will only turn to certain suppliers’.68

(54) Based on the above feedback from market participants, it appears that generally supply side substitutability is limited with respect to container ships. While shipbuilders may construct a number of different categories of container ships, most shipbuilders do not build all categories. In particular with respect to larger container ship categories, such Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships, only few shipbuilders are capable to build these ships, and it would not be easy for others to enter the production of these categories.

(D) Conclusion

(55) The results of the market investigation discussed above support the appropriateness of distinguishing between different categories of container ships, based on size – in particular their TEU capacity. While some market participants referred to different dividing lines between container ship segments, the categorisation according to Clarksons is widely used by industry participants. There appears to be virtually no demand side substitutability, while there does appear to be some limited level of supply side substitutability when considering smaller categories of container ships or the intersection between the large Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships and Post- Panamax ships. Nevertheless, when considering large container ships, including Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships, only few shipbuilders are capable of producing them.

(56) In any event, the exact scope of product market definition with respect to container ships can be left open since the Transaction would not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible alternative product market definition and irrespective of whether a separate market is defined according to the Clarksons categorisation for Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships.

5.1.2. Construction and supply of bulk carriers

(57) Bulk carriers are commercial vessels that carry dry bulk cargo, such as iron ore, raw coal, thermal coal, grains, steel or cement. There are various sizes of bulk carriers. Figure 3 below illustrates a Newcastlemax bulk carrier from JMU.

5.1.2.1. Notifying Parties’ arguments

(58) Since the Commission has not distinguished between different sizes and cargo capacities of bulk carriers in previous decisions, the Notifying Parties submit that the relevant market is the overall market for the construction, production and sale of bulk carriers.69

(59) The Notifying Parties submit that bulk carriers should not be further segmented by size or by region or port, namely into Small, (DWT <10 000), Handysize (DWT 10 000 - <40 000), Handymax/Supramax (DWT 40 000 – <65 000), Panamax (DWT 65 000 - <80 000), Capesize (DWT >100 000) or additional categorizations of very large bulk carriers such as Kamsarmax (DWT 80 000 – 90 000), Dunkirkmax (DWT 170 000 – 180 000), Newcastlemax (DWT 180 000 – 190 000) or Setouchmax (DWT 200 000 – 210 000), given that there is no common understanding as to how the various ship size categories should be defined beyond a general understanding.70 Moreover, the Notifying Parties submit that different ship classification societies have different definitions.71

(60) From a supply-side perspective, the Notifying Parties argue that the range of the ship size that a manufacturer can build is determined by the physical constraints of its shipyard. In particular, the Notifying Parties submit that Asian shipbuilders – which they regard as significant competitors – are capable of producing the whole range of bulk carrier sizes.72

(61) The Notifying Parties further submit that, from a demand-side perspective, the choice of a bulk carrier depends on the goods to be transported and the routes and harbours to be serviced.73 In this regard, they explain that Capesize ships are ordered where the intended use does not involve the passage of the Suez and Panama Canals and where the capacity is needed; that larger bulk carriers typically transport iron ore or coal; or that Panamax bulk carriers often carry grain or coal. The Notifying Parties submit that many ship owners order bulk carriers of different sizes and, as a result, that there are no distinctive customer groups for different bulk carrier sizes.74

(62) Lastly, the Notifying Party submits that it is not necessary to regard Newcastlemax and Setouchmax as separate categories as it is widely recognised in the industry that they belong to the same category of Newcastlemax.75

5.1.2.2. Commission’s assessment

(A) Market participants have a common understanding of bulk carrier categories

(63) Clarksons defines different sizes of bulk carriers according to their DWT into: Small (DWT <10 000), Handysize (DWT 10 000 - <40 000), Handymax (DWT 40 000 –<65 000), Panamax (DWT 65 000 – <80 000), Panamax (DWT 80 000 – <100 000)and (vi) Capesize (DWT >100 000).76 Moreover, additional categorisations are used in the industry to refer to the specific regions or ports that bulk carriers may service, such as Kamsarmax (DWT 80 000 – 90 000)77, Dunkirkmax (DWT 170 000 – 180000)78, Newcastlemax (often with a DWT 180 000 – 190 000)79 or Setouchmax (DWT 200 000 – 210 000)80. The Notifying Parties appear to rely in fact on these different categories. In this regard, JMU’s website includes entries for Newcastlemax, Dunkirkmax or Panamax.81

(64) Contrary to the Notifying Parties’ submission, market participants appear to have a common understanding of different bulk carriers’ categories based on (i) size (by DWT); and (ii) specific region or ports.

(65) First, a vast majority of those customers and competitors that responded to the market investigation submitted that the Clarksons size categories by DWT identified in paragraph (63) above are regularly relied upon in interactions between shipbuilders and customers.82 In this regard, some customers expressed that ‘[t]hese categories are normally an important part of the interaction between shipbuilders and shipowners’ or that this ‘category is very common for shipyard industry and all the people in the market’. A competitor also expressed that ‘[t]hese categories are typically used in discussions with ship owners and data providers use the same categories’. A number of market participants considered moreover that these categories are ‘world common in shipping industry’ or a ‘[w]orld standard’. For all, a customer indicated that ‘the distinction Clarksons make is perfectly rational and justifiable on the basis of size and deadweight. The bigger the vessel, the lower the building price per deadweight’.83

(66) A majority of both customers and competitors who responded to the market investigation moreover considered that, within this first general segmentation of size categories by DWT, it is not appropriate to further sub-segment the category for Capesize bulk carriers (DWT >100 000) to assess the relevant competitive dynamics.84

(67) Secondly, a vast majority of those customers that responded to the market investigation submitted that a segmentation by regions or ports into Kamsarmax (DWT 80 000 – 90 000), Dunkirkmax (DWT 170 000 – 180 000), Newcastlemax (DWT 180 000 – 190 000) and Setouchmax (DWT 200 000 – 210 000) are also regularly relied upon in interactions between shipbuilders and customers.85 The responses of competitors were however inconclusive on this point.86

(68) In this regard, a customer submitted that these ‘categories are relied upon to define more precisely the type of bulk carrier to be contracted’.87 Another customer explained that these categories are ‘[r]ather self-evidently [, as] some ports have physical size restrictions which limit what ships can service them’.88 A number of market participants clarified that these categories are not limited to the particular ports of reference, but may also be used in ‘any other ports as far as their size fit to’.89 In this regard, a competitor explained that ‘a bulk carrier named ‘Dunkirkmax’ can and do serve various ports which have a similar size to Dunkirk. In other words, the reference relates to the size rather than a specific geographic region’.90

(69) Based on the above, it therefore appears that market participants do have a common understanding of the various categories of bulk carriers, which are in turn relied upon in exchanges between market participants. In order to establish whether these categories could form the basis for distinct container ship product markets, the extent of supply and demand side substitutability is assessed in the following sections.

(B) Demand-side substitutability between different bulk carrier categories

(70) A majority of those customers and competitors that responded to the market investigation submitted that shipping companies typically use different categories of bulk carriers to carry out the same types of services at competitive conditions.91

(71) In this regard, there appears to be at least in theory some overlaps in the use that shipping companies may make between different adjacent categories of bulk carriers. A customer explained that ‘if the (large) Capesize market is very strong (expensive for cargo owners) then they might decide to break down their cargo into two or more vessels of smaller size (say Panamax or Handymax)’.92 Another customer indicated that ‘Panamax type of tonnage can carry the similar cargo of Cape size’ and that ‘Handymax can do the same as Panamax type’.93 In this same direction, a competitor explained that shipping companies ‘may use larger bulk carriers for international routes and smaller carriers for short-distance routes’, but that ‘adjacent vessel classes are frequently substitutable (e.g. Panamax and Capesize)’.94 A customer however submitted that ‘[v]essel size and specification is crucial to most routes. Some overlapping can happen but depends primarily on whether it is possible and whether the vessel rates can justify it’.95

(72) In practical terms, however, several customers pointed to limitations when asked whether a bulk carrier of any category could be used for any of the bulk transport services that their company provides or whether their company used different categories of bulk carriers to address different needs.96 First, several customers indicated that ‘specific port restrictions in terms of the vessels’ dimensions such as its draft and length’ or the ‘sizing restrictions to dock and offload’ represent an important factor when deciding for a category of bulk carrier. For instance, a customer explained that Handysize and Supramax are self-sufficient, as they have their own cranes on board and can on-load and off-load the cargo by themselves, while Panamax vessels and above are without cargo gear on board and are therefore dependent on the existing equipment of the port of loading and discharge.97 Secondly, commercial viability is another important factor that determines the use of particular types of bulk carriers. In this regard, a customer pointed out that ‘a bulk carrier can theoretically carry almost all bulk commodities, but it might not be economical’, while another one highlighted restrictions ‘due to the commercial viability as the freight can be cheaper by using bigger vessels’. Thirdly, some types of bulk carriers appear to be better suited to transport particular types of dry cargo. In this sense, a customer indicated that ‘iron ore is moved primarily on capesizes, coal on capesizes and panamaxes, grain on panamaxes and handymaxes and so called minor bulks in handysizes (and smaller)’. For all these reasons, a customer explains that while ‘[i]n theory a bulk carrier of any category, subject to physical limitations, may be used for the services [its] company provides’, ‘[i]n reality, the services [it] provides is mainly carried out by one specific vessel type and size’.

(C) Supply-side substitutability between different bulk carrier categories

(73) Several respondents indicated that the size of the dry docks and the equipment restrictions of the shipyards (such as crane capacity) are decisive factors for the size of the bulk carriers that a shipbuilder can construct. While large bulk carriers cannot be constructed in smaller-sized docks, shipbuilders with large docks can construct bulk carriers of smaller sizes. Customers indicated in this sense that ‘[a]s long as the drydock capacity is large enough, the shipyard can build any type of bulk carriers’ and that ‘[f]or those shipyards which can build a Capesize should also be able to build a smaller Handysize’.98 A customer moreover indicated that ‘[b]arriers to entry […] are not great as subcontractors are available in most markets’.99 Moreover, a competitor further indicated that, provided the docks are sufficiently large, ‘the construction method is basically the same for any bulk carrier category’ as ‘[d]ifferent classes of bulk carriers are not distinguishable in terms of the construction process’.100

(74) A majority of those competitors that responded to the market investigation submitted that they do not build bulk carriers of all different categories referred to in paragraph(63) above.101 In this regard, several competitors indicate that this is due to their ‘lack of infrastructure’ or to their ‘corporate strategy’.102

(75) A majority of those customers and competitors that responded to the market investigation nevertheless submitted that some producers of bulk carriers are typically able to build a wide range of bulk carrier categories.103

(D) Conclusion

(76) The results of the market investigation discussed above indicate that it may be appropriate to distinguish between different categories of bulk carriers based on size (by DWT) and on type of port or region. However, the exact categories according to which distinction should be made for the purpose of market definition are not clear.While these categories appear to be widely used by industry participants, there appears to be some level of demand- and supply-side substitutability when considering adjacent categories of bulk carriers.

(77) In any event, since the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible product market definition, it can be left open whether all types of bulk carriers belong to a single product market or whether distinct markets should be identified for various bulk carriers segments (i.e. into (i) Small (DWT <10 000); (ii) Handysize (DWT 10 000 - <40 000); (iii) Handymax (DWT 40 000 – <65 000); (iv) Panamax (DWT 65 000 - <80 000); (v) Panamax (DWT 80 000 - <100 000); and (vi) Capesize (DWT >100 000)) or according to specific ports or regions (i.e. into (i) Kamsarmax (DWT 80 000 – 90 000); (ii) Dunkirkmax (DWT 170 000 – 180 000); (iii) Newcastlemax (DWT 180 000 – 190 000); and (iv) Setouchmax (DWT 200 000 – 210 000). The competitive assessment in Section 7.3 take into consideration all these potential sub- segmentations.

5.1.3. Construction and supply of PCTCs

5.1.3.1. Notifying Parties’ arguments

(78) PCTCs are commercial ships designed for shipping cars and trucks only.104 The Parties submit that the relevant market is that for the construction, production and sale of PCTCs. Figure 4 below illustrates a PCTC.

5.1.3.2. Commission’s assessment

(A) Potential sub-segmentations within the market for PCTCs

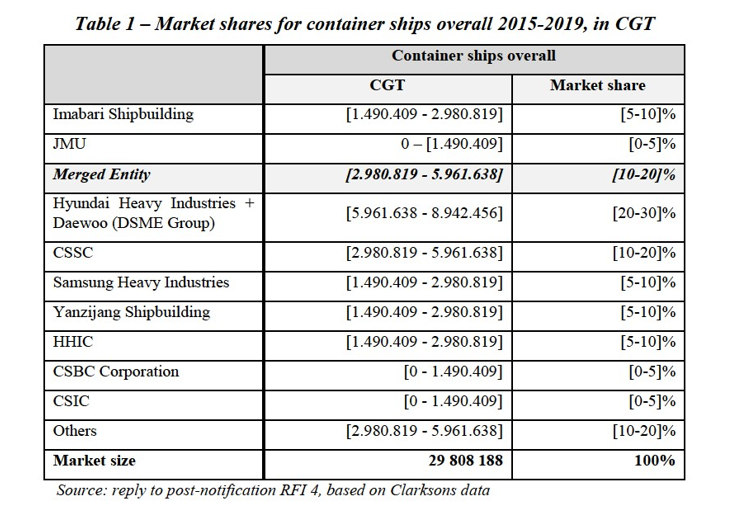

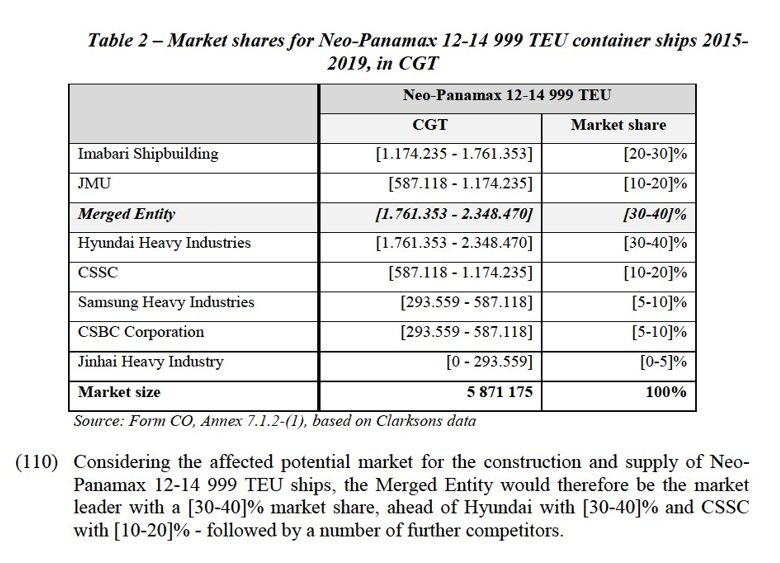

(79) In the course of the market investigation, the Commission has sought to verify whether it would be appropriate to further segment the market for PCTCs, notably in relation to the size of the ships or the number of cars they carry.105

(80) In that regard, while the majority of customers indicated they were unable to answer the question as they are not active in the PCTC segment, responses were mixed among those who expressed an opinion as to whether a distinction according to size would be necessary in relation to PCTCs. In general, respondents indicated that the right size vessel is always chosen and deployed by charterer for each assigned journey in consideration of cargo volume, required frequency, and port characteristics.106 When asked about the potential segmentations for the PCTC market, some respondents suggested a segmentation by number of vehicles (less than 2 000, between 2 000 and 3 999, between 4 000 and 5 999 and above 6 000)107. As regards this potential narrower segmentation, the activities of the Parties only overlap in relation to PCTC with a number of cars above 6 000 units.

(B) Demand-side substitutability between different PCTC categories

(81) A majority of customers that responded to the market investigation and expressed an opinion submitted that shipping companies cannot use different categories of PCTCs to carry out the same type of service at similar competitive conditions. Conversely, a majority of competitors that responded to the market investigation and expressed an opinion said that they can.108

(82) In any event, those customers that expressed an opinion when responding to this specific aspect of the market investigation submitted that, when deciding which type of vessel to operate for a particular service, they take into consideration a large number of aspects such as, cargo volume,109 required frequency,110 route,111 or port characteristics112.

(C) Supply-side substitutability between different PCTC categories

(83) A majority of the customers that expressed an opinion in the market investigation submitted that ‘some’ producers of PCTCs are typically able of building a wide range of PCTC categories, while a majority of competitors indicated that ‘all’ PCTC producers were able to do so.113 Several respondents indicated in this regard that the dockyard size and the equipment and infrastructure are the main constraints to produce PCTCs of different size categories.114 In this regard, one competitor submitted that ‘[p]rocedures and know-how are the same with regardless the size of the vessel. The only limiting requirement is the size of the dry dock’.115

(84) A majority of competitors active in the construction of PCTCs that expressed an opinion in the market investigation submitted that they do not build PCTCs of all sizes.116 In this regard, a competitor indicated that while it ‘could build all PTCTs of all categories […] [it] would build specific category of PCTCs considering facilities and manpower for price competitiveness’.117

(D) Conclusion

(85) The results of the market investigation discussed above indicate that it may be appropriate to distinguish between different categories of PCTCs based on the number of vehicles they can carry.

(86) However, the exact scope of product market definition with respect to PCTCs can be left open since the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market under any plausible alternative product market definition and irrespective of whether all types of PCTCs belong to a single product market or whether different segmentations of PCTCs can be identified for (i) less than 2 000 cars; (ii) between 2 000 and 3 999 cars; (iii) between 4 000 and 5 999 cars; and (iv) above 6 000 cars.

5.2. Geographic market definition

(87) In previous decisions, the Commission defined the relevant geographic market for the construction and sale of commercial ships as worldwide in scope.118 The Notifying Parties agree with this definition and do not propose an alternative.119

(88) A vast majority of the customers and competitors that responded to the market investigation agreed that the relevant geographic market for the assessment of the relevant competitive dynamics in shipbuilding is global in scope.120

(89) In light of these considerations, as well as all evidence available to it, the Commission considers that the markets for the construction and supply of (i) container ships; (ii) bulk carriers; and (iii) PCTCs, including possible segmentations thereof, are worldwide in scope.

6. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT: LEGAL FRAMEWORK

(90) Under paragraphs 2 and 3 of Article 2 of the Merger Regulation, the Commission must assess whether a proposed concentration would significantly impede effective competition in the internal market or in a substantial part of it, in particular through the creation or strengthening of a dominant position. In this respect, a merger may entail horizontal and/or vertical and/or conglomerate effects. For the purposes of the competitive analysis of the Transaction, only horizontal effects may potentially arise.

(91) Horizontal effects arise when the parties to a concentration are actual or potential competitors in one or more of the relevant markets concerned. The Commission appraises horizontal effects in accordance with the guidance set out in the Horizontal Merger Guidelines.121

(92) In horizontal mergers, non-coordinated effects may significantly impede effective competition by eliminating the competitive constraint imposed by each merger party on the other, as a result of which the merged entity would have increased market power, without resorting to coordinated behaviour. In that regard, the Horizontal Merger Guidelines consider not only the direct loss of competition between the merging firms, but also the reduction in competitive pressure on non-merging firms in the same market that could be brought about by the merger.122

(93) The Horizontal Merger Guidelines list a number of factors which may influence whether or not significant non-coordinated effects are likely to result from a merger, such as the large market shares of the merging firms, the fact that the merging firms are close competitors, the limited possibilities for customers to switch suppliers or the fact that the merger would eliminate an important competitive force.123 Furthermore, in accordance with the Horizontal Merger Guidelines, a merger with a potential competitor can also have horizontal anti-competitive effects where the potential competitor constrains the behaviour of firms active in the market.124 Not all these factors need to be present for significant non-coordinated effects to be likely. The list of factors is also not an exhaustive list.

7. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT: HORIZONTAL NON-COORDINATED EFFECTS

(94) The Transaction has been notified to the Commission on 11 November 2020. At the time of notification of the Transaction, another transaction partially affecting the same markets had already been notified to the Commission.

(95) The Commission notes, in that regard, that in assessing the competitive effects of a proposed transaction under the Merger Regulation, it needs to compare the competitive conditions that would result from the notified concentration with those that would have prevailed in the absence of the concentration. As a general rule, the competitive conditions prevailing at the time of notification constitute the relevant framework for evaluating the effects of a transaction. In some circumstances, however, the Commission may take into account future changes to the market that can be reasonably predicted.125

(96) Based on those principles, the principle of equal treatment and the provisions of the Merger Regulation, notably Article 6(1) thereof, the Commission has consistently taken the view126 that, in cases of parallel investigations into concentrations affecting the same relevant markets, the first transaction to be notified (‘the first transaction’) should be assessed on its own merits and on the basis of the market structure prevailing at the time of that notification. The second transaction to be notified (‘the second transaction’) should, conversely, be assessed on the basis of the market structure resulting from the likely implementation of the first transaction.

(97) On 12 November 2019, that is before the notification of the Transaction, Hyundai Heavy Industries Holding (‘HHI’) notified the Commission of its intention to acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation a majority interest in Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering Co., Ltd. (‘DSME’) (Case M.9343).127 The HHI/DSME transaction partially affects the same markets as the Transaction assessed in the present decision, notably as regards container ships.

(98) Therefore, given the circumstances in this case, the Transaction (which is thus ‘the second transaction’) should be assessed taking into account the HHI/DMSE transaction notified on 4 June 2018 (which is ‘the first transaction’). The starting point for the Commission's assessment of the Transaction is therefore a likely market structure where the Parties’ competitors HHI and DMSE would be treated as a single entity.

7.1. Notifying Parties’ arguments

(99) The Notifying Parties submit that the Transaction does not significantly impede effective competition in any shipbuilding markets.128 In particular, the Notifying Parties argue that the Transaction does not eliminate important competitive constraints and does not confer market power to Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU enabling them in particular to increase prices.129

(100) The Notifying Parties submit that the Parties’ combined shares are below 20% in all main ship categories worldwide in the period 2015-2019. In addition, the Notifying Parties submit that there are many competitors remaining in each category. According to the Notifying Parties, their combined market shares only exceed 30% if two sub-categories are considered, namely (i) the bulk carrier sub-category Newcastlemax (DWC 180-190kt); and (ii) the container ship sub-category Neo Panamax (TEU 12-14 999). However, the Notifying Parties submit that these segments do not constitute separate markets.

(101) The Notifying Parties submit that the Parties’ ships are not closer substitutes than the ships of other competitors. In this regard, the Parties argue that the ships of Imabari Shipbuilding, JMU and its competitors are basically similar, with their differences arising from specific customer demands.

(102) The Notifying Parties submit that switching costs are very low and do not play an important role for customers when changing from one shipbuilder to another. Each ship is a single project and when new ships are needed, the customer requests quotes from several shipbuilders, defining the specifications for each project. The customer then compares the prices, performance, and delivery dates offered by each shipbuilder to select the shipbuilder who offers the best deal. Thus, customers can easily switch to another shipbuilder without spending much time or expense. The customers’ fleets usually include ships built by multiple shipyards.

(103) The Notifying Parties state that competitors are able to increase supply if prices increase, as competitors have sufficient capacity. The Notifying Parties explain that shipbuilders generally build various types of vessels and switch between the production of these categories regularly. Once a ship-builder possesses the technology and necessary know-how to build a specific type of ship and there are no physical limitations regarding its yards for the building of ships of certain sizes, it can quite easily adjust its production according to market need.

(104) The Notifying Parties submit that Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU will not be able to hinder expansion by competitors. There are no indications that Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU will be able to or have the incentive to make the expansion of smaller firms and potential competitors more difficult or otherwise restrict the ability of competitors to compete. IS and JMU do not have particular influence on the supply of inputs or distribution possibilities. The shipbuilding markets are also not markets where interoperability between different infrastructures or platforms is important.

(105) Lastly, the Notifying Parties submit that the Transaction will not entail the elimination of an important competitive force. In this regard, the Notifying Parties explain that neither Imabari Shipbuilding nor JMU have more influence on the competitive process than their market shares would suggest. None of both recently entered the market nor are IS and JMU particularly important innovators. All shipbuilding companies are currently conducting research and development on environmentally friendly ships to more or less the same degree.

7.2. Construction and supply of container ships

(106) Both Parties are active in the construction and supply of container ships. While Imabari Shipbuilding is active in a number of categories of containerships, JMU’s activities in recent years have been almost exclusively focused on Neo-Panamax 12- 14 999 TEU ships.

(107) The Notifying Parties submit that in relation to container ships, potential affected markets only arise with respect to the category of Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships and with respect to container ships >7 999 TEU. The latter would however only be affected if considering 2017-2019 market shares ([20-30]% combined share in CGT and [20-30]% combined share in number of ships).

7.2.3. Sufficient alternatives for customers

(113) It appears that post-Transaction, customers will continue to have access to a number of alternative suppliers of container ships, including Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships. Considering the 2015-2019 market shares in Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships, in particular Hyundai Heavy Industries, CSSC, Samsung Heavy Industries and CSBC Corporation will remain as established shipbuilding companies with track records also in constructing large container ships including Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships.

(114) Information on the current order books by shipbuilders submitted by the Notifying Parties and based on Clarksons data further shows that customers are also likely to have access to alternatives in the future.135 The Clarksons data show that JMU currently [...] Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ship under construction. While Imabari Shipbuilding has [...] such container ships on its order books, Hyundai ([...]), Samsung ([...]) and Yangzijiang Shipbuilding ([...]) all have more currently on their order books. It would thus appear that the Merged Entity’s market share based on delivery dates is likely to decrease in coming years.

(115) Customers responding to the market investigation confirm that they would still have access to sufficient alternative shipbuilders to turn to for ordering container ships (including Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships) after the Transaction. Specifically asked whether if faced with a 5-10% price increase by the Merged Entity post- Transaction they would have sufficient alternatives, a large majority of customers expressing their opinion submit that both for container ships overall and for Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 container ships this would be the case.136

(116) This is further confirmed by the circumstance that no responding customer considers that their likely reaction to a 5-10% price increase by the Merged Entity would be to absorb that price increase. A majority of customers providing substantive answers submit that their likely reaction to such a price increase by the Merged Entity would be to switch to another supplier of container ships.137 A customer in this context explains that a ‘5-10% price increase is important and might create an overcost for the shipowner and, in the end, the containership price will not be competitive enough compared to other shipyards’.138 Another customer submits that it is ‘able to find other good container builder in not only Japan but also in Korea/China’.139 Yet another customer ponders ‘why need to place an order with the higher price ? we have Korean/Chinese yards instead’.140 This further confirms that customers have effective access to alternative shipbuilders of container ships.

(117) Customers who in the past may have bought Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships from either of the Parties will in the future likely not face any significant barriers to ordering Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships from a competing shipbuilder instead. The project-driven demand characteristic for the industry means that customers can easily and without any significant costs opt for any of the shipbuilders which responds to a tender for a new Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ship that meet the criteria of the customer (e.g. price, delivery time).

(118) Large majorities of customers and competitors expressing their opinion submit that no new shipbuilders not previously active in container ships have entered since 2015.141

(119) Barriers to entry appear to be particularly pronounced with respect to large container ships, such as Neo-Panamax (including 12-14 999 TEU) and Post-Panamax ships.142 Customers confirm this: a large majority of customers expressing their opinion state that they would not order large container ships from a shipbuilder with experience in building only smaller container ships.143 As described in 5.1.1.2(C), the main limitations hindering certain container shipbuilders to manufacture and supply large container ships, such as Neo-Panamax and Post-Panamax ships, are dock size, experience and know-how.

(120) Fewer barriers however likely exist between large container ship categories. This is evidenced by almost all shipbuilders active in Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships144 also being considered capable to manufacture Post-Panamax ships, at least in the opinion of some customers.145 Additionally, shipbuilders currently active in Post- Panamax ships, but not in Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships, are likely also capable to enter the construction and supply of Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships relatively easily and without the need for any significant investments. The fact that market participants describe a number of shipbuilders as capable to build the largest type of container ships currently available on the market (i.e. the largest versions of Post-Panamax ships), underlines that a number of strong competitors with capabilities for the construction of very large container ships will remain post- Transaction. These competitors would likely also be able to construct the category of container ship below in size to Post-Panamax, i.e. Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU. The shipbuilders listed most often as capable to construct the largest container ships available on the market include CSSC, CSIC, COSCO, Hyundai- Daewoo, Samsung, Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU. Some respondents also deem Hanjin Heavy Industries or Kawasaki Heavy Industries as capable.146 Therefore, a larger number of shipbuilders is likely capable of constructing Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships (and to participate in tenders) than evidenced by the 2015-2019 market shares. These shipbuilders often also have a track record in Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships, but simply have not built any ships of this category over the last five years (as is for example the case for Daewoo and COSCO).147 In case the Merged Entity were to increase its prices for Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships post-Transaction, these shipbuilders may find it economically attractive to (re-)enter the manufacturing of this category of container ships.

(121) Therefore, while barriers are likely significant when considering entry into the construction and supply of container ships overall, as well as when considering a potential diversification of builders of smaller container ships into larger container ships, barriers are less relevant when considering a distinction between different large categories of container ships, e.g. Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU and Post- Panamax ships. This further suggests that customers of Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU ships have access to a number of capable alternative shipbuilders.

(122) Overall, therefore, customers of container ships in general and of Neo-Panamax 12- 14 999 TEU container ships in particular, will continue to have effective access to a number of established alternative shipbuilders post-Transaction.

7.2.4. Overall impact

(123) Large majorities of customers and competitors responding to the market investigation do not expect the Transaction to have a negative effect on price, quality, capacity, the availability of slots at shipyards, and innovation.148

(124) Four customers responding to the market investigation indicate that they have in the past bought Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships from either of the Parties. Neither of them expects a negative development as a consequence of the Transaction with respect to the parameters of price, innovation, quality and availability of slots at shipyards, while only one expects a decrease in capacity.149 It therefore appears that with respect to the affected potential market of Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships, customers with a record of ordering such ships with the Parties do not expect the Transaction to have a negative impact on them or on competition.

7.2.5. Conclusion

(125) In light of the considerations in this Section 7.2, the Commission concludes that in the potential worldwide market for the construction and supply of container ships, as well as in all possible segments, in particular the Neo-Panamax 12-14 999 TEU container ships, the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market due to horizontal non-coordinated effects. This is because (i) the Parties’ market shares are moderate; (ii) they are not particularly close competitors; (iii) customers have effective access to a number of established alternative shipbuilders; and (iv) a large majority of market participants has indicated that the Transaction would have no negative impact on price, quality, capacity, and innovation.

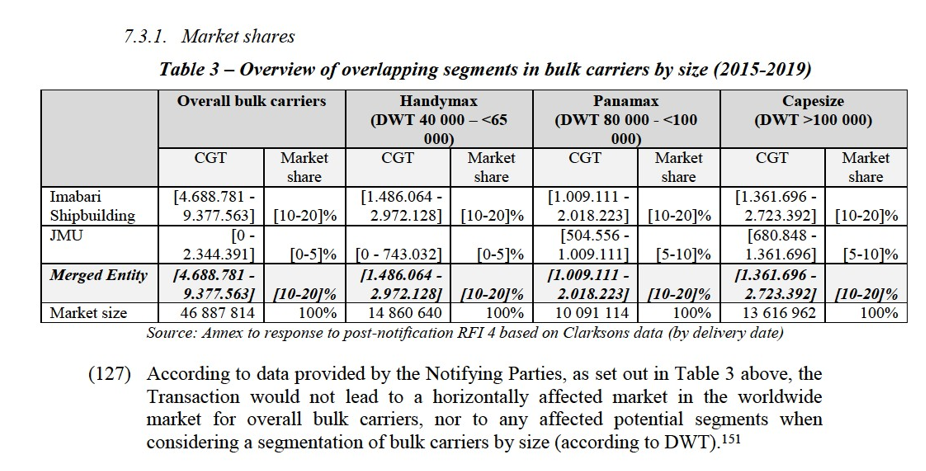

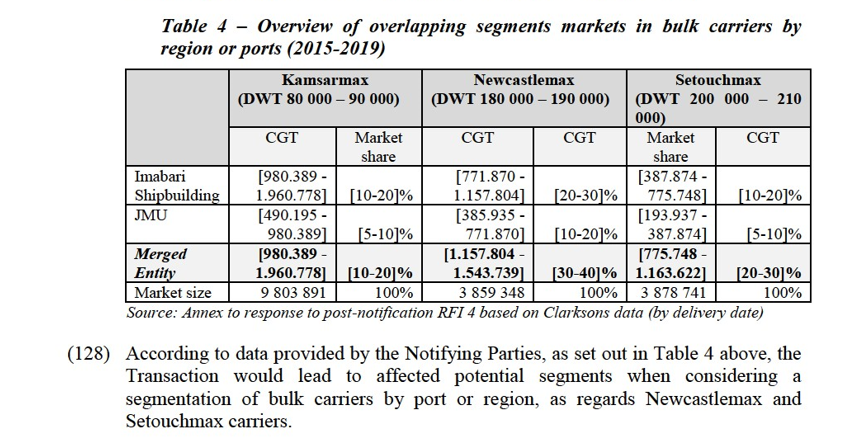

7.3.Construction and supply of bulk carriers

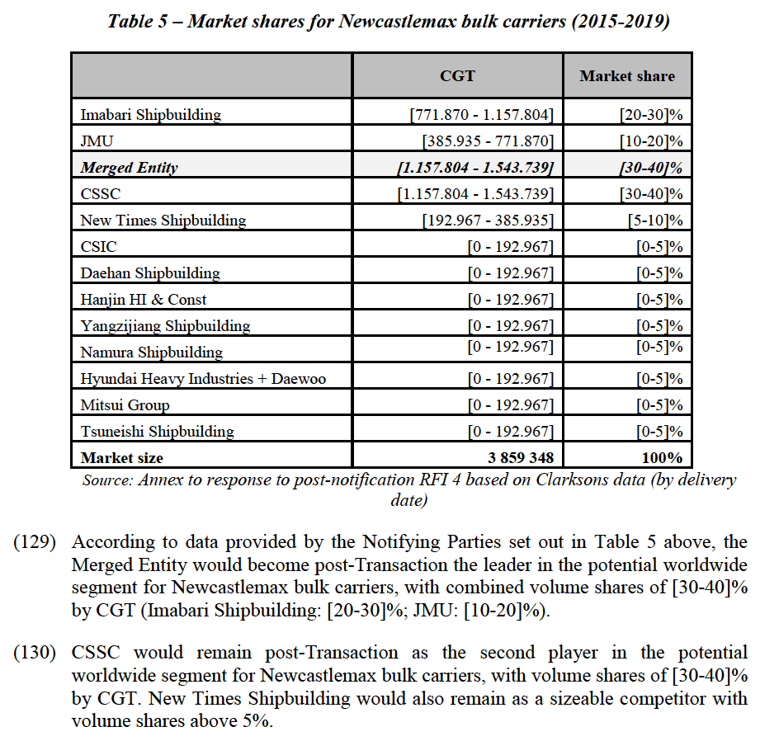

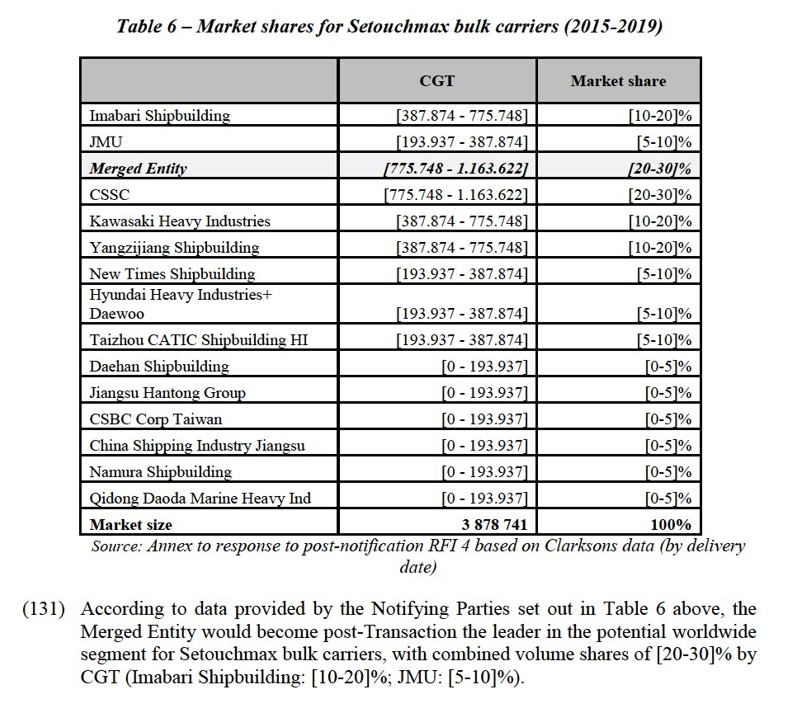

(126) The Transaction gives rise to horizontally affected markets in the overall market for bulk carriers, as well as in several potential sub-segments, namely in Handysize, Handymax, Capesize,150 Newcastlemax and Setouchmax.

Imabari for bulk carriers in terms of quality, innovation and shipyard capabilities.153 The responses from competitors in this regard were inconclusive.154

(134) A clear majority of the customers that responded to the market investigation moreover indicated that Imabari is the overall closest competitor to JMU with respect to bulk carriers, followed by Tsuneishi and Oshima.155 When asked to rank the closest competitors to JMU based on a number of parameters, a clear majority of customers indicated that Imabari is the closest competitor to JMU for bulk carriers in terms of innovation and shipyard capabilities.156 In terms of price and quality, the responses of customers were mixed between those who indicated Imabari and those who indicated Oshima.157 The responses from competitors in this regard were inconclusive.158

7.3.3.Sufficient alternatives for customers

(135) At the outset, it appears that the bulk carriers industry is characterised by certain barriers to entry. In this sense, a majority of those customers and competitors that responded in the market investigation indicated that no shipbuilders not previously active in bulk carriers had entered the supply of bulk carriers since 2015.159 As one customer points out, the general trend instead appears to be ‘to exit the shipbuilding business due to substantial decrease of new vessel ordering’.160 Moreover, a majority of customers also indicated that they would not order large bulk carriers from a shipbuilder with experience in building only smaller bulk carriers.161 Several of these customers submitted in this regard that experience and a track-record in building large bulk carriers are important factors.162

(136) Information on the current order books of shipbuilders submitted by the Notifying Parties and based on Clarksons data nevertheless indicates that customers are likely to have access to sufficient alternative shipbuilders in the future across all potential sub-segments of bulk carriers.163 In particular for Newcastlemax bulk carriers, the order books show that Imabari has […] vessels of this size under construction, while JMU has […].164 In comparison, CSSC (under Shanghai Waigaoqiao), CSI (under Beihai Shipyard) and Hyundai Heavy Industries + Daewoo have each […] Newcastlemax bulk carriers under construction, while Namura Shipbuilding and Yangzijiang Shipbuilding have […] each.165 In the case of Setouchmax bulk carriers, the order books show that Imabari has […] vessels of this size under construction, while JMU has […]. In comparison, CSSC (under Shangai Waigaoqiao) has […], Jiangsu Hantong has […], COSCO has […], CSIC (under Beihai and Bohai shipyards) has […], and New Times Shipbuilding has […].166

(137) The information derived from the order books of shipbuilders is consistent with the feedback that market participants have expressed in the market investigation. An overwhelming majority of those customers who responded to the market investigation indicated that, in case of a 5-10% price increase by Imabari and JMU after the Transaction, they would have sufficient alternative shipbuilders to turn into for all possible sub-segments of bulk carriers and specifically for small, Handysize, Handymax, Panamax (DWT 65 000 - <80 000), Panamax (DWT 80 000 - <100 000), Capesize, Newcastlemax and Setouchmax.167 In particular, several customers indicated that there would remain sufficient alternative Japanese shipbuilders following the Transaction for all these different categories of bulk carriers.168 In this regard, some customers indicated that ‘[t]here are multiple alternative Japanese shipbuilders for each categories above even after the combination of Imabari and JMU’ or that customers currently ‘have many choice[s] for shipyard, not only Japan, but also other countries’.169 In particular, some respondents indicated that Namura, Oshima, Tsuneishi, Kawasaki or Mitsui have shipyards in Japan that can build bulk carriers from each category.170 Another customer expressed there is no a particular type of bulk carrier that only Japanese shipbuilders are able to build.171 For all, a customer indicated ‘absolutely YES. [N]umerous builders in the same segments’.

(138) This perception of sufficient alternative shipbuilders may also be observed by the fact that a majority of those customers that responded to the market investigation indicated that, in a scenario where the price of bulk carriers would increase by 5- 10%, their likely reaction would be to switch to another supplier.172 In this regard, several customers indicated that they would have alternative shipbuilders from Japan, China or Korea. A customer indicated in this sense that ‘[s]ince there are multiple shipyards, including China, that can build vessel that do not differ significantly in performance, we will select other shipyard with a low price’.173

7.3.4. Overall impact

(139) A large majority of the customers and competitors that responded to the market investigation expect that the Transaction will not change price, quality, capacity, innovation or the availability of slots at shipyards in the bulk carrier industry.174 A number of these respondents also indicated that the Transaction could potentially bring a positive change in these parameters of competition, i.e., a reduction in price and an increase in both quality and capacity,175 as well as innovation.176

7.3.5. Conclusion

(140) In light of the considerations in paragraphs (127) to (139) above, the Commission concludes that in the worldwide market for bulk carriers overall, as well as in the potential sub-segments for Handysize, Handymax, Capesize, Newcastlemax and Setouchmax bulk carriers, the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market or the functioning of the EEA Agreement due to horizontal non-coordinated effects given that (i) the combined entity would only have modest market shares and would continue facing competition from several shipbuilders; (ii) customers have overwhelmingly confirmed that they would have sufficient alternative suppliers for all potential sub-segments of bulk carriers; and

(iii) a large majority of market participants has indicated that the Transaction would have no impact on price, quality or capacity.

7.4.Construction and supply of PCTCs

7.4.1. Market shares

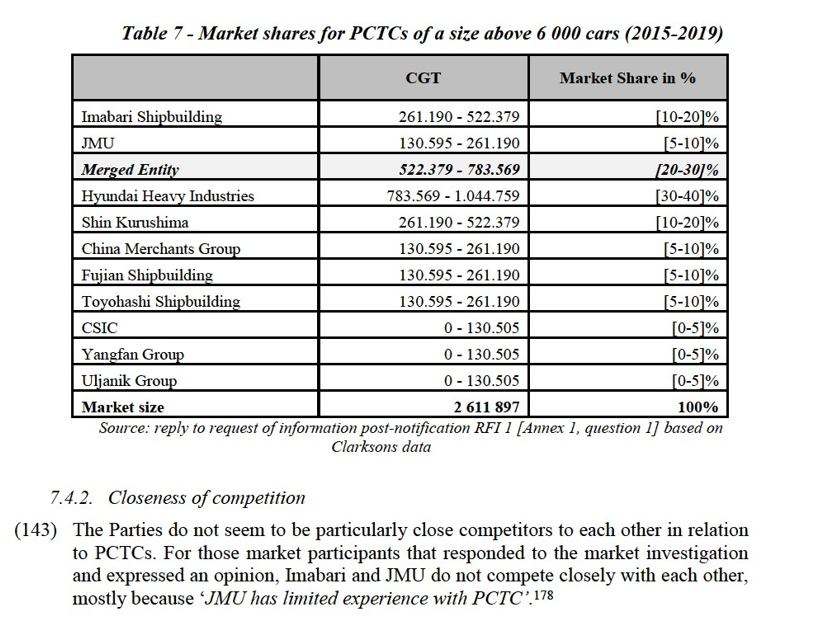

(141) The market for the construction and supply of PCTCs would be affected only if a separate product market for PCTCs above 6 000 cars is considered.

(142) According to data provided by the Notifying Parties, as set out in Table 7 below, the combined share of the Merged Entity in the potential market for PCTCs above 6 000 cars would remain modest at [20-30]% based on number of ships delivered or CGT over the 2015-2019 period.177 Hyundai would remain market leader based on both number of ships and CGT with [30-40]%. The Merged Entity would also continue to face competition by Shin Kurushima ([10-20]% on both number of ships and CGT), China Merchants (between [5-10]% and [10-20]%) and Fujian Shipbuilding ([5- 10]% on both number of ships and CGT).

7.4.4. Overall impact

(146) A large majority of market participants that responded to the market investigation do not expect the Transaction to have a negative effect (in terms of price, innovation, quality, capacity and availability of slots at shipyards) on the market for PCTCs.185 Moreover, the outcome of the market investigation revealed that there will remain at least two other players in Japan active in large PCTCs, including one (Shin Kurushima) that is twice as big as JMU in the construction and supply of PCTC above 6 000 cars.

7.4.5.Conclusion

(147) In light of the considerations in this Section 7.4, the Commission concludes that in the potential worldwide market for the construction and supply of PCTCs, including the possible segment of PCTCs above 6 000 cars, the Transaction does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market due to horizontal non- coordinated effects. This is because (i) the Parties’ market shares are moderate; (ii) they are not particularly close competitors; (iii) customers have effective access to a number of established alternative shipbuilders; and (iv) a large majority of market participants has indicated that the Transaction would have no negative impact on price, quality, capacity and innovation.

8. CONCLUSION

(148) For the above reasons, the European Commission has decided not to oppose the notified operation and to declare it compatible with the internal market and with the EEA Agreement. This decision is adopted in application of Article 6(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation and Article 57 of the EEA Agreement.

1 OJ L 24, 29.1.2004, p. 1 (the ‘Merger Regulation’). With effect from 1 December 2009, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (‘TFEU’) has introduced certain changes, such as the replacement of ‘Community’ by ‘Union’ and ‘common market’ by ‘internal market’. The terminology of the TFEU will be used throughout this decision.

2 OJ L 1, 3.1.1994, p. 3 (the ‘EEA Agreement’).

3 Publication in the Official Journal of the European Union No C 398/15, 23.11.2020, pp. 19 ‒ 20.

4 Letter of the Notifying Parties’ counsel, 16 July 2020.

5 Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice (‘CJN’), paragraph 76.

6 Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice (‘CJN’), paragraph 77.

7 Ibid.

8 Turnover calculated in accordance with Article 5 of the Merger Regulation.

9 The latest CGT system was adopted and promulgated by the OECD Council Working Party on Shipbuilding. It came into force on 1 January 2007. See: https://www.oecd.org/industry/ind/37655301.pdf.

10 See, in particular, Commission decision of 5 May 2008 in case M.4956 – STX/AKER YARDS, paragraph 40.

11 For RORO carriers, LNG carriers, ferries and tankers, the IHS Markit data was provided by the Notifying Parties.

12 Excluding cruise ships in which European shipbuilders have a leading role.

13 Both Parties provide repair and minor conversion services for commercial ships such as hull works (painting of hulls, repair of damaged parts, maintenance of deck equipment, etc.), engine works (maintenance of main/auxiliary engines, propellers, etc.), and electrical and piping works (maintenance of electrical equipment and wiring on board ships, exchange and maintenance of various piping, etc.). Both Parties had limited revenue from ship repair services, in particular with customers outside of Japan. In this regard, JMU generated EUR […] million in fiscal year 2016 (of which only EUR […] with customers outside of Japan) and EUR […] million in fiscal year 2017 (of which only EUR […] with customers outside of Japan), while Imabari Shipbuilding generated EUR […] million in fiscal year 2016 and EUR […] million in fiscal year 2017 and […] with non-Japanese customers (response to RFI 5, question 3). It can therefore be reasonably excluded that the Transaction could raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market in relation to the repair of commercial ships.