Commission, April 14, 2021, No M.10047

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

SCHWARZ GROUP / SUEZ WASTE MANAGEMENT COMPANIES

Subject: Case M.10047 — Schwarz Group/SUEZ Waste Management Companies

Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) in conjunction with Article 6(2) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 19 February 2021, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which SB PreZero GmbH & Co. KG, PreZero International GmbH and SB Dienstleistung KG, all part of the Schwarz group (together ‘Schwarz’, or ‘PreZero’) acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control over a number of companies of SUEZ Groupe S.A.S. (‘SUEZ’) which comprise its recovery and recycling operations in Luxembourg, Germany, the Netherlands and Poland (together the ‘Target’), by way of purchase of shares (the ‘Proposed Transaction’).3 Schwarz is designated hereafter as the ‘Notifying Party’ and together with the Target as the ‘Parties’.4

1. THE PARTIES

(2) Schwarz operates as an integrated service provider in the markets for the collection, sorting, treatment, recycling and disposal of household and commercial waste under its PreZero division. PreZero has sites in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and the United States. Recently, PreZero acquired SUEZ Nordic AB and is now also active in Sweden.5 Schwarz is also active in food retailing in over 30 countries through its retail chains Lidl and Kaufland.

(3) The Target is active in the markets for collection, sorting, treatment, recycling and disposal of household and commercial waste in each of Germany, Poland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

2. THE OPERATION

(4) The Proposed Transaction consists of the acquisition by Schwarz of the entire issued share capital of companies that constitute the Target. Upon completion of the Proposed Transaction, Schwarz will exercise sole control over the Target.6

3. UNION DIMENSION

(5) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (Schwarz: EUR 114 302 million; Target: EUR 1 133 million).7 Each of them has a Union-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (Schwarz: EUR […]; Target: EUR 1 133 million), but each does not achieve more than two-thirds of its aggregate Union-wide turnover within one and the same Member State. The notified operation therefore has a Union dimension.

4. RELEVANT MARKETS

4.1. Introduction

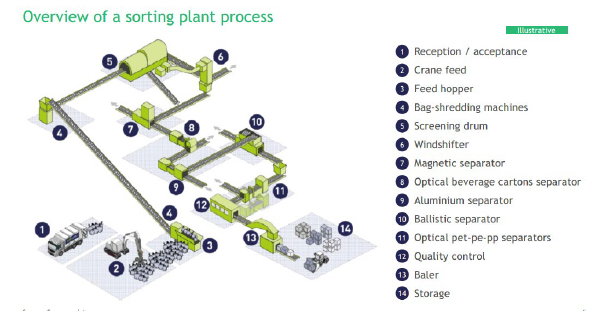

(6) Schwarz and the Target are both vertically integrated throughout the waste management chain.

(7) Waste management and recycling services comprise a number of services with respect to a variety of different types of waste and materials, provided by waste management companies to municipalities, industrial and commercial customers, and households. The Parties are active in the collection, sorting and treatment, recycling and disposal of various types of waste and waste fractions.

(8) The Commission has previously concluded that the supply of waste management services for hazardous waste8 is distinct from that for non-hazardous waste.9

(9) The Notifying Party agrees with this delineation, and submits that for hazardous waste no further segmentation in any manner is required. Concretely, the Proposed Transaction does not result in any overlaps other than for the collection of hazardous waste.10 The Notifying Party submits that customers of waste collection services tend to entrust the collection of all their hazardous waste together, and that from a supply-side perspective the leading waste management companies are all able to collect all types of hazardous waste, and it is easy to adapt or subcontract the collection of certain types of hazardous waste if needed.11

(10) The market investigation results did not lead to any conclusions contradicting this assessment. As regards a possible further segmentation for hazardous waste, it is in any case not necessary to delineate exactly the scope of the relevant product markets, since any such segmentations do not affect the outcome of the competitive assessment of the Proposed Transaction. In particular, the Proposed Transaction does not result in affected markets for hazardous waste under any plausible product market definition.12 For that reason, hazardous waste will not be further discussed in this Decision.

(11) With regard to non-hazardous waste, the Commission has found that separate product markets could be defined for each stage of the waste management process in previous decisions. Concretely, as a first step, the different waste fractions, such as paper and cardboard, lightweight packaging (‘LWP’), glass and residual waste, are collected from households, collection points, factories, offices, industrial sites, shops etc. (collected volumes may be grouped in a transfer station before further treatment). The collected waste is then sorted and/or treated, to recover valuable waste fractions for commercialisation as secondary raw materials (e.g. recycling) or prepare the waste for disposal at incineration plants or landfill sites. As a result, the Commission has in the past defined separate product markets for the collection, sorting and treatment13, commercialisation14 and disposal15 of non-hazardous waste.16

(12) With regard to the collection of non-hazardous waste, the Commission has in previous decisions differentiated between the collection of household waste on the one hand, and industrial and commercial waste on the other.17 Within industrial and commercial waste, the Commission has considered a possible further segmentation between demolition & construction waste, industrial waste, and commercial waste.18

(13) Within household waste, the Commission has found that separate product markets could be defined depending on the type of waste fraction concerned, and has considered a distinction between inter alia paper, paperboard and cardboard (‘PPC’), flat glass, hollow glass and LWP (including different plastics, aluminium, tinplate and various composites).19 This segmentation has been applied across the various stages of the waste management chain.

(14) The Notifying Party agrees with the Commission’s decision-making practice of defining separate relevant product markets for the various stages of the waste management process. It also concurs that a relevant product markets exists for the collection of household waste, separate from the collection of commercial and industrial waste.20 As regards a further segmentation based on waste fractions, the Notifying Party agrees that such a segmentation is appropriate for the collection of waste,21 so that a separate relevant product market exists for the collection of hollow glass, as well as for sorting and treatment, so that a separate relevant product market exists for the sorting of LWP.22

(15) The market investigation confirmed that separate relevant product markets exist for the various stages of the waste management process. Furthermore, the market investigation did not elicit any evidence contradicting the existence of a relevant product market for household waste, separate from industrial and commercial waste. Lastly, as regards the distinction by waste fractions at the different stages of the waste management process, market participants confirmed that separate relevant markets exist at least for each of collection of hollow glass and sorting of LWP.23

(16) Within the framework described above, considering all plausible product markets and the assessment on the plausible geographic markets in Sections 4.2.2 and 4.3.2, the Proposed Transaction only gives rise to horizontally affected markets in relation to the sorting of LWP as a result of the Parties’ overlapping activities in the Netherlands and for the collection of hollow glass as a result of the Parties’ overlapping activities in Germany. As such, this will be the starting point for the Commission’s assessment in this Decision. Furthermore, the Proposed Transaction gives rise to several vertical links (examined in section 5.3), namely (i) between the collection of LWP and the collection of industrial and commercial (‘I&C’) waste24 (both upstream) and the sorting of LWP (downstream), (ii) between the sorting of LWP (upstream) and the commercialisation of LWP (downstream), and (iii) between the collection of I&C waste (upstream) and the retail sale of daily consumer goods25 (downstream).26

4.2. Sorting of LWP

(17) Within the recycling process, the first stage is for LWP to be collected, following which it is brought to an LWP sorting plant where different fractions are recovered, before being commercialized. LWP sorting plants use different techniques (such as optical or magnetic sorting, infrared technology and compressed air) to separate all types of LWP fractions.27 The extracted materials are then compressed into bales, which are sold to recyclers.28

(18) In the Netherlands, there are two alternative ways of collecting and sorting LWP from households: source-separation and post-separation. In a system of source- separation, households separate their waste, disposing of LWP in a distinct bin or bag that is collected separately and then sorted into different LWP fractions at an LWP sorting plant. Post-separation systems require an additional step: households do not separate all their waste but rather dispose of LWP and residual waste in a single bin or bag. Consequently, after collection, the LWP must be separated from the residual waste at a post-separation plant and is then transported to the LWP sorting plant, where it is sorted into different LWP fractions. 29

(19) Finally, the demand for LWP sorting services in the Netherlands emanates from organisations to which producers and importers of packaged products – which are legally responsible for the prevention, collection and recycling of packaging waste – have delegated their responsibilities.30 This ‘extended producer responsibility’ applies to companies that are the first to make packaged products available to the market in the Netherlands and/or who remove the packaging on import.

4.2.1. Product market definition

(20) As mentioned above in Section 4.1, the Commission has previously considered the existence of separate relevant product markets for each stage of the waste management process on the one hand, and for the various waste fractions on the other, pointing to the existence of a relevant product market for the sorting of LWP.

Notifying Party’s view

(21) In line with the Commission’s decision-making practice, the Notifying Party agrees that a separate relevant product market exists for the sorting of LWP.31

(22) The Notifying Party submits that no further segmentation based on whether a source- separation or post-separation system applies is warranted. Notably, it argues that both source-separated LWP and post-separated LWP are ultimately sorted by an LWP sorting plant, and that the vast majority of LWP sorting plants are able to compete for the sorting of both source-separated LWP and post-separated LWP without a need for technical adjustments. Moreover, it observes that, in addition to separating waste streams, post-separation plants also extract LWP fractions for a portion of the volumes that they handle. Indeed, post-separation plants sell approximately 25% of the extracted LWP fractions directly to recyclers,32 just as LWP sorting plants do with the fractions that they extract. As such, according to the Notifying Party those volumes should be included in the LWP sorting market.33

Commission’s assessment

(23) Firstly, the market investigation has confirmed the existence of a distinct market for the sorting of LWP. Indeed, virtually all market investigation respondents have confirmed that LWP sorting is carried out separately from the sorting of other waste fractions, by different companies and at specific plants that are only able to sort LWP. There is a specific demand for the sorting of LWP, which is subject to distinct tendering and contracting.34

(24) Secondly, as regards a possible distinction based on whether a source-separation or post-separation system applies, a large majority of market investigation respondents confirmed that post-separation plants and LWP sorting plants are operated by different companies, carry out different tasks and correspond to different customer needs. Concretely, the market investigation showed that post-separation and LWP sorting in fact take place at different levels of the waste management value chain, with post-separation being a necessary intermediary step before LWP sorting when no source-separation is being carried out.35 Moreover, the Parties admit that post- separations services are subject to different contracts than LWP sorting.36 Respondents to the market investigation have confirmed that operators of post- separation facilities do not compete for LWP sorting contracts and, vice-versa, LWP sorters do not compete for post-separation contracts.37 As a result, post-separation services do not compete with LWP services. The Commission therefore considers, for the purpose of this Decision, that both source-separated LWP and post-separated LWP volumes should be considered to belong to the LWP sorting market (as ultimately both types of LWP are sorted in the same LWP sorting plants); however, post-separation services form a separate market, upstream of LWP sorting.

(25) As regards the LWP fractions extracted in post-separation plants and sold directly to recyclers, the Commission does not consider that these volumes belong to the LWP sorting market. The mere fact that LWP fractions extracted in post-separation plants might compete with the fractions extracted in LWP sorting plants when it comes to the commercialisation of LWP fractions38 does not provide evidence of the existence of any competitive relationship between post-separation plants and LWP sorting plants in the LWP sorting market. On the contrary, as explained in paragraph (24) above, LWP sorting entities do not compete for post-separation contracts and post- separation plants do not compete for LWP sorting contracts. Therefore, there is no reason to include LWP fractions extracted in post-separation plants in the LWP sorting market.

(26) Thirdly, one respondent to the market investigation observed that, in the Netherlands, household LWP should be distinguished from commercial LWP. This is because the sorting of household LWP falls under the extended producer responsibility scheme, while commercial LWP currently does not.39

(27) In this regard, first, according to the Notifying Party, there are no technical obstacles preventing facilities from sorting both household and commercial LWP, and in any case the current situation will change from 2023, when commercial LWP will also fall under the scope of the extended producer responsibility scheme. At that time, both types of LWP will be dealt with in the same manner. Second, it appears that currently, commercial LWP is primarily incinerated, with only very limited volumes being sorted (6 kt of commercial LWP compared to 455 kt of household LWP). Third, while the Target has sorted approximately […] in 2020, the Notifying Party […].40

(28) For those reasons, the Commission considers that the question whether different markets for the sorting of commercial and household LWP exist can be left open for the purpose of this Decision. Given that the Parties’ activities only overlap for the sorting of household LWP, and as the limited volumes of commercial LWP sorted would make no material difference to the competitive assessment, the Commission will only examine the effects of the Proposed Transaction on the market for the sorting of household LWP.

4.2.2. Geographic market definition

(29) The Commission has not previously examined the sorting of LWP. In Remondis/DSD, which was referred by the Commission to the German competition authority (‘Bundeskartellamt’),41 the Bundeskartellamt considered regional markets for the sorting of LWP in Germany, based on the LWP sorting plants' catchment areas and supply streams, without reaching a conclusion on the precise geographic market definition.42

Notifying Party’s view

(30) Overall, the Notifying Party takes the view that the market for the sorting of LWP generated in the Netherlands is at least national in scope, given that LWP can easily be transported across the Netherlands for sorting as well as cross-border.43 Concretely, currently approximately a third of all Dutch LWP is sorted in Germany. Furthermore, according to the Notifying Party Belgian LWP sorting plants can also compete for the sorting of Dutch LWP.44

(31) The Notifying Party further argues that barriers for LWP sorters located outside of the Netherlands to compete are low. First, as regards transport costs, the Notifying Party explains that, while it does not know the distance LWP currently travels between the point of collection and the LWP sorting plants, the distance between its transfer stations and LWP sorting plants (i.e. excluding the distance between the point of collection and the transfer station which is unknown, thus underestimating the overall travel distance) varies but can viably go up to 300 km or more. Notably, the Notifying Party submits that several of their German LWP sorting plants are sorting or have sorted Dutch LWP in the past. For example, […], and PreZero has in the past sorted Dutch LWP at Porta Westfalica, which is 170 km from the Dutch border.45 The Notifying Party also provided examples of LWP being transported over distances greater than 300 km. Concretely, it submits that PreZero sorts LWP from […] in its German LWP sorting facilities. According to the Notifying Party, this shows that there is no fixed maximum distance for the transport of Dutch LWP for sorting.46

(32) The Notifying Party stresses that in any event, the transport costs are not a determinative factor for obtaining LWP sorting contracts, as ultimately customers consider the total costs of the LWP recycling chain.47 According to the Notifying Party, transport costs for the transfer of the (collected) LWP from the transfer station to the sorting facility accounts in general for significantly less than […]%, and possibly less than […]%, of the total costs of the recycling chain.48 In the Notifying Party’s view, transport costs therefore cannot be considered to impede German LWP sorting facilities in competing for Dutch LWP sorting contracts. In that context, the Notifying Party has, by way of example, provided information on a tender issued by Midwaste/RKN which it won (for quality reasons) in 2019, though for which the second-closest bidder was a German LWP sorter, which was actually able to offer a better price in spite of distance.49

(33) The Notifying Party further argues that transport costs are not determinative given that higher transport costs for sending LWP to Germany can be compensated by lower sorting costs in Germany and by lower transport costs when LWP is subsequently sent to recyclers in Germany. This is in particular relevant as “almost none” of the recycling plants to which sorted Dutch LWP can be sent are located in the Netherlands.50

(34) Second, as regards technical barriers, the Notifying Party submits that there are no technical barriers that could limit the possibilities for non-Dutch LWP sorting plants to sort Dutch LWP. Concretely, the waste fractions making up the LWP sorted in LWP sorting plants are in general similar in both the Netherlands and Germany.51 While the Notifying Party recognizes that the proportion of the different waste fractions in the overall LWP mix differs depending on the country the LWP originates from, it argues that these differences do not have an impact on the ability of German LWP sorters to sort Dutch LWP, as German plants would only have to make minor adjustments to achieve that purpose.52 Furthermore, although Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006 of 14 June 2006 on shipments of waste (the ‘Waste Shipment Regulation’), provides that packaging waste from different areas of origin must not be mixed,53 LWP sorters are able to sort LWP from both countries in the same LWP sorting plant by using a so-called ‘batch operation’ system.54 The Notifying Party estimates that it takes less than one hour to switch between the sorting of Dutch LWP and the sorting of German LWP or vice versa, and the switching does not incur other costs than the loss of revenues flowing from the time required for the switching.55

(35) Third, from a regulatory perspective, German LWP sorting facilities need to obtain an export license to be authorized to import Dutch LWP to Germany, which is to be requested by the exporting company (i.e. the LWP sorter’s customer).56 According to the Notifying Party, all waste management companies are used to and can easily do the required notifications. Moreover, administrative authorities reviewing license applications have no discretion and must accept them provided that the required forms are filled in adequately.

(36) Moreover, LWP transport is subject to the requirement of a financial guarantee (or equivalent insurance) covering in particular the cost of transport, cost of storage and costs of recovery or disposal. The amount of the bank guarantee is generally based on the volumes transported, though local authorities have discretion in determining the exact amount of such guarantees. According to the Notifying Party, the need to provide a financial guarantee does not constitute a barrier to trade since it can either be easily obtained by a bank or directly provided by the customer.57

Commission’s assessment

(37) As per the Market Definition Notice, the relevant geographic market is defined as ‘the area in which the undertakings concerned are involved in the supply and demand of products or services, in which the conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous and which can be distinguished from neighbouring areas because the conditions of competition are appreciably different in those areas.’58 Determining a relevant (geographic) market is thus a tool to identify the geographic area within which the conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous, and within which companies are able to exert a competitive constraint on the Parties concerned.

4.2.2.1. Demand for LWP sorting is national

(38) The Notifying Party has explained,59 and the market investigation has shown, that demand for the sorting of LWP is national, as the chain for the recycling of LWP is organised at the national level.

(39) European Union Directive 94/62/EC of 20 December 1994 on packaging and packaging waste (‘the Packaging Directive’) requires Member States to take necessary measures to ensure that systems are set up for the collection and recycling of packaging waste. These systems must be open to the participation of economic operators. Member States however have discretion regarding the manner in which they choose to implement this obligation, and schemes implementing the Packaging Directive vary by country in their design and scope.

(40) Under the Dutch ‘extended producer responsibility’ regime, which implements the Packaging Directive,60 producers and importers of packaged products are legally responsible for the prevention, collection and recycling of packaging waste. Such companies, when they are above a certain size, must register with Afvalfonds Verpakkingen (‘Afvalfonds’),61 and pay a fee to Afvalfonds according to the volumes of packaging they place on the market. In exchange, Afvalfonds takes over their responsibility for the recycling of packaging waste. Nedvang BV (‘Nedvang’, formerly ‘VPKT’) is the fully-owned subsidiary of Afvalfonds that ensures the practical implementation of the extended producer responsibility principle, both directly by contracting for the sorting and recycling of packaging waste, and indirectly by compensating other bodies that arrange for sorting and recycling.

(41) Moreover, the composition of LWP to be sorted and the manner in which collection of waste is organised varies from country to country. For instance, Dutch LWP typically has a higher plastic content that LWP originating in Germany, where plastic bottles are partly covered by a deposit scheme and recovered separately.62 These differences have a decisive impact in the sorting process, as explained in Section 4.2.2.2(D).

(42) In short, demand for LWP sorting services is structured nationally, based on national rules governing the legal responsibility for the collection and sorting of LWP. As such, in the following section, the Commission will assess the competitive conditions for the supply of LWP sorting services to customers in the Netherlands, where the Parties’ activities overlap.

4.2.2.2. Supply of sorting services of LWP is impacted by distance, customer preferences, composition of LWP and national regulations

(43) The supply of LWP sorting services to Dutch customers appears to be limited by a number of factors, in particular distance from the plant to collection point, customer preferences, composition of LWP and national regulations, although this does not prevent some facilities located in Germany from also sorting LWP from the Netherlands. Concretely, of the approximately 450kt of Dutch LWP sorted in 2020, around 1/3rd was sorted in plants in Germany located close to the Dutch border (with the farthest plant being situated 150km from the border in driving distance).

(44) In order to identify the area in which the conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous, the Commission will assess the barriers that exist for the sorting of LWP from the Netherlands, as identified by the market investigation. The following factors are relevant for this assessment: first, transport costs significantly limit the distance which LWP can travel to reach an LWP sorting plant. Second, environmental costs are taken into account as customers try to avoid transporting LWP for sorting over long distances to minimize the associated CO2 emissions. Third, beyond transport and environmental costs, LWP sorters broadly report that customers have a preference for keeping waste within the country. Fourth, due to the specific LWP composition and quality requirements, technical adjustments are required for a German (or Belgian) plant to be able to sort also Dutch LWP. Fifth, sending LWP for sorting outside the Netherlands involves more administrative formalities than sorting the LWP within the country.

(A) Travel distance and transport costs

(45) In order to test the Notifying Party’s arguments on the lack of economic barriers for non-Dutch LWP sorters to sort LWP from the Netherlands, the Commission investigated the maximum economically viable travel distance of LWP for sorting and the importance of transport costs.

(46) First, as regards the maximum economically viable distance over which LWP can travel for sorting, the Notifying Party’s views were contradicted by the market investigation. Notably, in the course of the market investigation, a majority of respondents asserted that LWP cannot profitably travel distances in excess of 200 km for sorting. This is because LWP is a very light material with a low mass density, which therefore occupies considerable space. In terms of tonnage this means that only a relatively small amount of LWP can be transported in a truck at a time. Pressing the LWP in bales is not an option because this has a very negative effect on the sorting of the material.63 This places plants in the Netherlands at a competitive advantage compared with plants in Germany.64 German competitors specifically indicated that distance is a ‘critical’ condition to be competitive in the market65 and they confirmed that it becomes uneconomical to transport LWP for sorting beyond 200 km.66 Moreover, one of the larger German sorters was of the view that it would not be competitive in tenders for the sorting of LWP originating from the provinces in the western part of the Netherlands, i.e. those located at around 200 km or more from its plant.67

(47) The Notifying Party points to instances in which LWP has travelled over distances greater than 200 km in order to reach a sorting plant.68 Concretely, the Notifying Party submits that it sorts LWP from […] at its plants in Germany, and that it is aware of several instances of LWP being transported over longer distances in Germany. However, the Notifying Party admits at the same time that […]% of the LWP sorted at the Parties’ own Rotterdam and Zwolle plants likely comes from less than 90 km away.69 Moreover, the mere fact that some LWP volumes are sent or have been sent in the past from […] to Germany by ship for sorting has little bearing on the assessment of competitive conditions for the sorting of LWP from the Netherlands and the transport costs involved in these cases cannot be compared with those for the transport of LWP from the Netherlands, which takes place entirely via truck. For those reasons, the Commission considers that the contrary examples provided by the Notifying Party do not alter the Commission’s finding that 200 km appears to be the maximum economically viable distance over which LWP can competitively travel for sorting, as shown by both the results of the market investigation. If anything, this appears conservative in view of Notifying Party’s own observation of the distance travelled by the bulk of the volumes that they sort, of 90 km.

(48) Second, with regard to transport costs, the Notifying Party argues that they are not a determinative factor for obtaining LWP sorting contracts, as ultimately the costs taken into account are the total costs of the LWP recycling chain. It further considers that higher transport costs for sending LWP to Germany can be compensated by lower sorting costs in Germany and by lower transport costs when LWP is subsequently sent to recyclers in Germany.70 The Notifying Party provides in this context as an example a tender issued by […] under which it was awarded a lot in 2019.71 The Notifying Party claims that it was awarded this tender as a result of qualitative rather than price factors (with price in this tender being the sum of the sorting rate and transport costs). The Notifying Party believes that the second-closest bidder was a German LWP sorter, which was actually able to offer a better price, and concludes from this that neither transport costs nor transport distance are determinative in tenders.

(49) However, the Notifying Party’s argument that the transport costs are not determinative for obtaining LWP sorting contracts is at odds with the tender specifications that it itself has shared, which do consider transport costs as an important assessment factor. Concretely, the Notifying Party has shared a sample of documents showing award criteria for eight tenders for the sorting of Dutch LWP awarded between 2014 and 2019. In six of the eight calls for tenders/contracts for LWP sorting, bidders were specifically asked to indicate the distance over which LWP would travel to reach the LWP sorting plant for the purpose of calculating transport costs, as an element of the price. Consequently, it appears that the cost of transport to the sorting station is a relevant element for customers to assess bids and determine the award of an LWP sorting contract.

(50) As such, it is clear that the correct framework for assessing the transport costs is not the total costs of the LWP recycling chain, as the Notifying Party claims, but rather the costs related to LWP sorting. Considering this, the data available shows that transport costs constitute a significant proportion of the costs of LWP sorting, and do limit how far LWP can be sent for sorting. Concretely, while the Notifying Party estimates that the cost of transporting Dutch LWP to a sorting plant in the Netherlands accounts for […]% of the total costs of the recycling chain (this figure rises to […]% if Dutch LWP is sent to a plant in Germany),72 however, as a proportion of sorting costs (rather than the total cost of the recycling chain), these figures rise to […]% and […]% when the LWP is sorted in plants in the Netherlands and Germany respectively. This indicates not only that transport costs are a significant part of the costs of sorting, but that those costs will increase substantially when LWP is sent to plants located in Germany.

(51) Furthermore, the Notifying Party’s argument in any case does not apply to situations where the entity commercialising the sorted LWP to recyclers is not the customer but the sorting entity itself. Notably, according to the Notifying Party, Nedvang – the main Dutch LWP sorting customer – ‘generally transfers the ownership of the LWP to the sorting plants except for some small volumes, for which it commercializes the sorted LWP itself’.73 Furthermore, the Notifying Party confirmed that for […] of the Target’s large LWP sorting contracts with the main Dutch customers, it is the Target itself (i.e. the LWP sorter, not the customers of the sorting service) that carries out the commercialisation of the sorted LWP.74 In those situations, the customer has an interest in minimising transport cost to the sorting station since it will not bear the costs from the sorting station to the recyclers.

(52) As described at paragraph (33) above, the Notifying Party also argues that transport costs are not determinative given that higher transport costs for sending LWP to Germany can be compensated by lower sorting costs in Germany and by lower transport costs when LWP is subsequently sent to recyclers in Germany. According to the Notifying Party, this is particularly relevant given that almost none of the recycling plants to which sorted LWP is sent are based in the Netherlands.

(53) On this, firstly the Commission notes that even in cases where the customer is responsible for the entire recycling chain, this argument would not apply in cases where the LWP is not recycled in Germany. Contrary to what the Notifying Party implies, this seems to be most of the cases. Concretely, according to the information provided by the Notifying Party, only […]% of the output volumes of the Target’s plant in Rotterdam was recycled in Germany in 2019, whereas […] […]% was recycled in the Netherlands and […]% in other countries. As regards PreZero, […]% of the output of its Zwolle plant in 2020 was recycled in the Netherlands.75 Therefore, in contrast to what the Notifying Party submits, it seems that in the vast majority of situations the entire recycling chain is kept within Dutch borders.

(54) Furthermore, even regarding the proportion of LWP sent to recycling plants in Germany, it is not apparent why for these volumes the lower cost of transporting sorted LWP from a sorting to a recycling plant in Germany would compensate for the higher cost of transporting LWP for sorting from the Netherlands to Germany. Indeed, unsorted LWP is more costly to transport than sorted LWP.76 Sorted LWP has a higher mass density since it has been cleaned up of impurities and, unlike unsorted LWP, can be and in fact is compressed into bales.77 As a result, the transport of sorted LWP is more efficient than the transport of unsorted LWP. In order to minimise costs at every step of the recycling chain, customers therefore seek to limit pre-sorting transport (i.e. where transport costs are proportionately higher).

(55) Finally, the Notifying Party’s view that higher transport costs can be compensated by lower sorting costs (in particular due to lower labour costs) in German plants is inconsistent with the views of market participants, who, as mentioned above in paragraph (46), indicated that they cannot offer competitive sorting services for LWP if it would need to travel further than 200 km. Furthermore, the Notifying Party’s own estimates are that the sorting cost of LWP (i.e. covering only the sorting fees at the facilities and not transport costs) in the Netherlands accounts for […]% of total costs (based on the entire recycling chain, from collection to commercialisation), while the figure for Germany is […]%.78 The difference therefore accounts for […]% of total sorting costs. The Notifying Party also estimates that the difference between the cost of transporting LWP to a sorting plant in the Netherlands and to a sorting plant in Germany is […]% of total costs of the recycling chain (and thus at least in a number of cases greater than the […]% difference in sorting fees). Therefore, even according to the Parties’ own estimates, higher transport costs are not necessarily entirely compensated by lower sorting costs. Moreover, the fact that plants in Germany may have lower labour costs does not change the fact that they are nonetheless rendered less competitive by transport costs.

(B) Environmental costs (CO2 emissions)

(56) The information available, notably calls for tenders and their specifications, shows that next to transport costs, the environmental cost of transport is also a factor taken into account by customers in awarding tenders. Sorters with more distant LWP sorting plants are sometimes penalised, through a correction of the price quoted or through negative points for quality, not only because of higher transport costs but also for environmental reasons related to the increased CO2 emissions associated with longer transport.

(57) Concretely, as mentioned, the Notifying Party has shared a sample of documents showing award criteria for eight tenders for the sorting of Dutch LWP organised between 2014 and 2019. In half of these tenders, bidders were awarded qualitative points for ‘sustainable transport’,79 based on the distance LWP would need to travel to the LWP sorting plant. The application of these qualitative criteria is intended to capture the environmental impact through higher CO2 emissions of transporting LWP over long distances.80

(58) As already mentioned in Section 4.2.2.2(A), besides being penalised under qualitative criteria, the transport distance to the sorting plant is also often reflected in the price score that a bidder is awarded. In six of the eight tenders reviewed, bidders were asked to specify the distance over which LWP would travel to reach the sorting plant for the purpose of calculating transport costs, as an element of the price. Although adjustments to the price are intended to correct for the financial cost of transportation over longer distances (rather than for the higher CO2 emissions from trucks), there is a significant overlap between tenders in which the transport distance is penalised through corrections to the price and those in which it is penalised through a loss of points for quality. In three of the eight tenders examined, a bidder with a plant located in Germany would have been doubly penalised for the distance of the sorting plant from the transhipment station where collected LWP would be gathered: first for the additional transport costs making the price less competitive (as explained in Section 4.2.2.2(A)), and second by losing points for quality linked to ‘sustainable transport’.81 This double penalty has been confirmed in the market investigation: customers expressed that LWP sorting plants should be situated as close as possible to the source of the waste, both because of the cost of transportation and given the need to minimise environmental harm from CO2 emissions in the waste management chain.82 Competitors also confirmed that besides being less competitive on price, bidders located at a greater distance would be allocated negative points in a tender due to high CO2 emission incurred by the transport of the waste, a disadvantage for which a bidder would need to compensate by lowering its price.83

(C) Customer preference for sorting of Dutch LWP in the Netherland

(59) In addition to transport costs and environmental costs which limit the distance over which LWP can travel for sorting, the market investigation also elicited that the sorting of Dutch LWP is impacted by the existence of a preference for sorting Dutch LWP within the Netherlands.

(60) Concretely, all sorters active on the Dutch LWP sorting market that responded to the market investigation considered that there is a political preference for Dutch LWP to be sorted in the Netherlands.84 One sorter explained that this preference is grounded on concerns about the integrity of the overall LWP sorting and recycling chain, and in particular regarding the proportion of collected LWP that is actually sorted and recycled. For that reason, sorting in the Netherlands is viewed more favourably from a political point of view, as it ‘provides better political backup’.85 German sorters active in offering LWP sorting services to customers in the Netherlands also believe that such customers have a preference for sorting to take place in the Netherlands.86

(61) Customers themselves provided mixed views. On the one hand, a number of customers denied the existence of any kind of national preference,87 or explicitly insisted that the distance, and not the specific country in which a sorting plant is located, is the most important factor in selecting a supplier of sorting services.88 On the other hand, several customers confirmed that municipalities on whose behalf they arrange for sorting do prefer LWP to be sorted in the Netherlands or close to the border.89 One respondent explains that this is motivated both by environmental reasons and by a desire to stimulate employment in the country where the waste is generated.90 One customer, which contracts LWP sorting services on behalf of a number of Dutch local authorities, explained that the Dutch government and municipalities expect LWP sorting to be achieved as close to the point where waste is generated as possible, and that they only have recourse to German sorters to the extent that capacity in the Netherlands is short.91 This would seem to be consistent with the (volume) market shares provided by the Notifying Party (see Table 2), which show that the proportion of LWP that customers have sent to be sorted to German plants has declined over the last years as new capacity has been built in the Netherlands.

(62) With regards to the 2019 Midwaste/RKN tender cited by the Notifying Party, the Commission understands that the most important factor in the Notifying Party’s success was its commitment to build a new sorting facility in the Netherlands. It is apparent from the award letter sent to the Notifying Party that under 3 of the 5 qualitative criteria applied in this tender, the decision to build a new plant at Zwolle was a key reason for the score awarded. This award letter states that “the new installation (in the Netherlands) creates clear added value for the circular economy.” The fact that the Notifying Party’s offer may not have been the most competitive in terms of price is unsurprising given that it involved sending LWP to Germany (to Schwarz’s plant in Porta Westfalica) for sorting during a transitional period (2019 and early 2020, incurring higher transport costs in that time) and given also the investments which the Notifying Party was incurring in building the new sorting plant in Zwolle. In any case, the fact that Schwarz decided to build a new plant in Zwolle to sort the Dutch LWP under this contract when it could have continued to sort Dutch LWP from its LWP sorting plant in Germany is indicative of a clear advantage for sorting Dutch LWP in plants closer to the collection point. The Commission therefore considers this tender to be further evidence of the fact that customers have a clear preference for LWP to be sorted in the Netherlands.

(D) Technical barriers

(63) The results of the market investigation also pointed to the existence of technical barriers for non-Dutch LWP sorters to sort Dutch LWP, related to the composition of the LWP mix and to the regulations on traceability of LWP. These barriers imply additional costs that LWP sorting plants located in other Member States must face when also sorting Dutch LWP alongside LWP from their own country. This further limits the possibility of sending Dutch LWP to neighbouring countries for sorting.

(64) First, the differences in the LWP mix between the Netherlands and Germany impact sorting operations. Sorters, in particular those which are able to sort Dutch LWP from plants in Germany, confirmed that the mix of waste fractions composing LWP is different in both countries and needs to be treated separately. Indeed, Dutch LWP tends to contain greater quantities of plastics, while German LWP tends to contain a greater proportion of paper and metallic waste. Because of the different composition of the waste, LWP needs to be sorted in different batches, and some adjustments must be made to the sorting machinery when changing batches from different countries, resulting in lost time (and therefore lost capacity). One sorter in Germany estimated the costs associated with switching between the sorting of Dutch and German LWP to be several thousands of euros per week, while another estimated these costs to be approximately EUR 250 000 per year. Therefore, a German plant that intends to sort also Dutch LWP must change its production process.92

(65) Moreover, Dutch regulatory requirements on the traceability of waste require that Dutch LWP be stored separately from LWP from other countries, both before and after sorting,93 which means that plants that want to sort both German and Dutch LWP need to invest in additional storage.

(66) For those reasons, despite mixed views as to the importance of these factors,94 German sorters that responded to the market investigation agreed that LWP sorting plants in Germany are at a significant disadvantage compared to LWP sorting plants in the Netherlands. A competitor who previously sorted Dutch LWP mentioned: ‘German and Dutch sorting plants are designed differently; have different processes in place to sort the different LWP mixes and attain the different standards. Sorting a different LWP mix would require the rebuilding of a facility. Adapting the plant to be able to receive LWP from another country would require significant investments, depending on the existing technology and size of the plant. Consequently, it is generally impossible for a plant to serve simultaneously Dutch and German customers’95. Another sorter which currently serves the Dutch market indicated that ‘[n]ot all German LWP sorting plants are necessarily able to sort Dutch LWP. Dutch regulations set different quality standards for the LWP sorting output than German authorities, and not all German plants can meet these standards, at least not without incurring additional costs’.96

(67) One respondent active in Germany located less than 20 km from the Dutch border, with prior experience in sorting Dutch LWP, indicated that adapting the sorting plants to sort LWP from different countries is very costly, while sorting LWP from different countries in shifts would also be very difficult, as the adjustments to the sorting lines would take 4-5 hours each time (thereby lowering the plant’s utilization). For these reasons, combined with the need to obtain authorisations for cross-border shipments of waste (discussed below), this respondent considered that it was significantly more difficult for plants in Germany to sort Dutch LWP.97 Other LWP sorters with plants in Germany close to the Dutch border, and which have sorted Dutch LWP in the past, likewise confirmed that sorting LWP from the Netherlands and Germany within the same facility was excessively complex and costly.98

(E) Administrative formalities

(68) Lastly, specific administrative formalities apply to the cross-border transport for LWP sorting. Concretely, sending LWP for sorting outside the Netherlands involves more administrative formalities than sorting the LWP in the country, including the setting up of a financial guarantee. This too limits the possibilities for transporting Dutch LWP cross-border for sorting.

(69) As mentioned above in paragraph (34), the regulation of cross-border transport of waste is harmonized at EU level through the Waste Shipment Regulation. Although these are not considered a serious impediment by German sorters already sorting Dutch LWP, they are seen as an additional obstacle by sorters in Germany and Belgium not currently active for the sorting of Dutch LWP.

(70) Concretely, sorters located in Germany which are active in the sorting of Dutch LWP indicated that they do not consider the costs of satisfying these administrative formalities (i.e. the fees and guarantees) to be very significant, although they also indicated that these costs, combined with the obligation to keep waste from different countries separate, did make it significantly more difficult for them to sort Dutch LWP.99 Among sorting plants close to the Dutch border in Belgium and Germany which do not sort Dutch LWP, a majority indicated that these administrative barriers make it significantly more difficult to sort Dutch LWP.

(71) Large customers of LWP sorting services in the Netherlands held differing views on whether the administrative barriers associated with the cross-border shipment of waste are a significant impediment for plants outside of the Netherlands. One large customer explained that in its view, the administrative obligations that come with notifying cross-border transports of waste, and the cost of the associated fees and guarantees, are not a problem for German LWP sorters for whom the sorting of Dutch LWP is part of their daily business.100 Three other customers however explained that the requirement to comply with the Waste Shipment Regulation places an additional burden on LWP sorting plants located in Germany when it comes to the sorting of Dutch LWP.101

4.2.2.3. Conclusion on geographic market definition

(72) In conclusion, for customers of LWP sorting services in the Netherlands, both supply and demand are national in scope.

(73) Indeed, it results from the above that Dutch LWP can generally only be sorted in an economically viable manner in LWP sorting plants that are relatively close to the transfer station where collected waste is gathered, notably at most approximately 200 km. The Market Definition Notice remarks that in cases like the present one, where the transport of a product incurs significant transport costs, deliveries from a given plant are limited to a certain area around each plant by the impact of transport costs.102 In principle, such an area could constitute the relevant geographic market. However, as the Market Definition Notice explains, if the distribution of plants is such that there are considerable overlaps between the areas around different plants, it is possible that the pricing of those products will be constrained by a chain substitution effect, and lead to the definition of a broader geographic market. Such chain substitution effects would appear to be present in the Netherlands. Given the size of the country, all sorting plants are able to compete for a significant part of national demand, and the radii within which they are able to offer LWP sorting services overlap to a significant extent.

(74) Other factors identified in the market investigation also suggest that the market for the sorting of Dutch LWP is national in scope, notably customer preference, variation in the composition of the LWP between Member States, technical regulations on traceability and other administrative factors.

(75) While these elements limit the ability of plants in other Member States to compete on an equal footing with Dutch plants for the sorting of Dutch LWP, they do not completely prevent them from competing, as illustrated by the fact that certain plants in Germany, located within the economically viable distance, together currently receive approximately one third of the volumes of Dutch LWP for sorting. These plants however should be considered out-of-market constraints, as they face additional costs and obstacles to supply customers in the Netherlands that Dutch plants do not face and, as explained earlier, are generally considered disadvantaged in comparison to them. That plants in other Member States are out-of-market constraints is also demonstrated by the fact that other German and Belgian plants do not sort Dutch LWP, do not submit bids or participate in any tenders for the sorting of Dutch LWP and, when approached by the Commission, these competitors showed to be largely unaware of the conditions (quality standards, administrative requirements) for sorting LWP, despite being in some cases very close to the Dutch border.103

(76) Ultimately, therefore, competitive conditions for the sorting of Dutch LWP are different for LWP sorting plants located in the Netherlands and LWP sorting plants located outside of the Netherlands (even if close to the border).

(77) For these reasons, the Commission considers that conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous only within the territory of the Netherlands, so that the relevant geographic market for the sorting of LWP is national.

4.3. Collection of hollow glass

4.3.1. Product market definition

(78) As mentioned above, in prior decisions, the Commission distinguished separate relevant product markets for each stage of the waste management process and for different waste fractions. In particular, the Commission has identified a separate relevant product market for the collection of hollow glass.104

Notifying Party’s view

(79) The Notifying Party agrees that the collection of hollow glass constitutes a separate relevant product market, though caveats that this is primarily relevant for household waste only, and for Germany.

(80) Notably, in Germany only certain waste fractions are collected directly from the households (i.e. PPC, LWP and residual household waste). Hollow glass is collected in containers that are set up in different communal spaces throughout the municipality, under specific collection contracts. This distinction is not relevant for I&C waste, where the different waste fractions are typically not collected separately.105

Commission’s assessment

(81) The market investigation confirmed the existence of a separate relevant product market for the collection of hollow glass. All market investigation respondents, both competitors and customers, indicated that in Germany, the collection of hollow glass is organised separately from the collection of other waste fractions.106 They explain that the collection of hollow glass is organised by so-called ‘dual systems’, which are operators that organise the recycling of packaging waste on behalf of the manufacturers, importers and retailers who, as distributors, are originally responsible for the recycling. This service is provided by the dual systems against payment of a license fee by the distributors. Dual systems thus tender and contract the collection of hollow glass separately. The collection itself is, contrarily to other waste fractions, not done directly at the households, but rather at centralised drop-off points in the collections areas of the municipality.107

(82) In view of the above, the Commission considers, for the purpose of this Decision, a separate relevant product market for the collection of hollow glass.

4.3.2. Geographic market definition

(83) In the past, the Commission has considered for the Netherlands that while the demand for the collection of hollow glass must be regarded as local, collection schemes are set up, financed and operated at national level, and that consequently prices, subsidies and means of collection vary from Member State to Member State. Larger collection companies are active across the country. For those reasons, the Commission considered the market for collection of hollow glass to be national.108 The Commission has not investigated the geographic scope for the collection of hollow glass in Germany. However, the Bundeskartellamt has considered both the national level and a ‘regional level’ comprising of a Landkreise (‘district’) and adjoining districts, ultimately leaving the geographic market definition open.109

Notifying Party’s view

(84) The Notifying Party submits that also for Germany, the collection of hollow glass is national in scope. It argues that in Germany too, large companies operate throughout the country, tenders are organised on a national basis and the regulatory framework is predominantly national in scope. The barriers to entry at regional level are very low; a company only needs to make available bottle banks and collection trucks and potentially hire additional employees in order to start operating in another region. Ultimately, companies collecting hollow glass face their competition at national level.110

Commission’s assessment

(85) The market investigation in the present case supports largely the arguments put forward by the Notifying Party.

(86) The demand for hollow glass collection services in Germany is structured on the basis of individual districts, but following rules set nationally. Contracts typically last three years, and market investigation respondents explained that on an annual basis, around a third of all districts in Germany are allocated to the dual systems, who are responsible for the organisation of the collection of hollow glass. The allocation of districts is random, on the basis of a lottery system which takes into account the volume licensed to each dual system. Dual systems can be allocated districts from all over the country. Dual systems operators then select their hollow glass collector in each of the districts for which they are responsible, by issuing calls for tenders that are open to all hollow glass collectors nationwide. The collection itself is done locally.111

(87) On the supply-side, the market investigation showed that some bigger companies, such as Schwarz, SUEZ, Remondis and Alba, organise their operations in terms of collection schemes, operations and financing nation-wide and are active across the country, while others are only present at the regional or local level. Indeed, whereas some competitors indicated that they have submitted bids and offer collection services across the country, others stated that they have submitted bids and offer services only for certain regions/districts. Customers have also indicated that while some companies submit bids across the country, others’ focus is more regionally or locally.112 As such, bigger companies appear to compete with each other at national level, and in certain regions with more regional or local players too.

(88) Furthermore, the market investigation has revealed that there are price differences across different regions in Germany, though market respondents explained in this regard that this is related mainly to whether it concerns collection in more urban versus in more rural areas, as transport costs differ.113 The legal framework is the same across the country, as it ‘is essentially determined by the Verpackungsgesetz (VerpackG), and in part also by the Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz (KrWG). Both are federal laws that claim national validity.’114 Whereas a local presence is required, barriers to enter a region seem to be rather low: market investigation respondents described that ‘[t]o take on a contract in a new district, a collector needs only trucks, containers and drivers, and a place to park the trucks and to weigh / temporarily store the hollow glass collected (transit warehouse) before it is picked up for transport to the sorting plants’. However, respondents also mentioned that ‘a company is usually less willing to compete in a region in which it does not yet have any infrastructure’. Some market investigation participants added that ‘the regional knowledge in a contractual area due to collection from central depot containers does not have to be too well-founded, as is the case with near-household collection services’ and that ‘[a]s projects are awarded based on the offered price, local reputation does not play a role in winning contracts for the collection of glass.’115

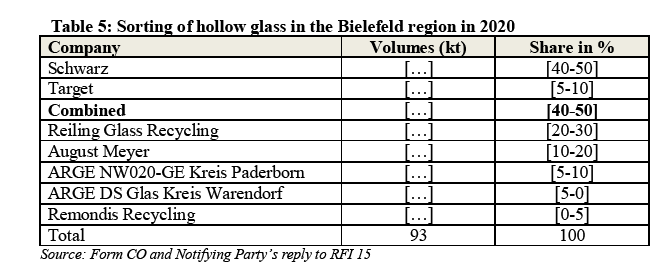

(89) In conclusion, while the market investigation point to the existence of a national market, it also showed the existence of regional or local elements. In any case, for the purpose of this Decision the exact geographic market definition can be left open as it does not affect the outcome of the competitive assessment of the Proposed Transaction with regard to the collection of hollow glass.

(90) As explained below, applying a conservative approach, the Commission will in its competitive assessment consider a smaller than national geographic market, comprising of the Bielefeld district and adjoining districts (the ‘Bielefeld Region’)116, as only under this plausible market definition the Proposed Transaction results in an affected market.

5. COMPETITIVE ASSESSMENT

(91) The Proposed Transaction gives rise to horizontally affected markets in relation to the sorting of LWP in the Netherlands and for the collection of hollow glass if the Bielefeld Region (Germany) is considered.

(92) Furthermore, the Proposed Transaction will give rise to several vertical links, namely (i) between the collection of LWP and the collection of I&C waste117 (both upstream) and the sorting of LWP (downstream), (ii) between the sorting of LWP (upstream) and the commercialisation of LWP (downstream), and (iii) between the collection of I&C waste (upstream) and the retail activities (downstream).118

(93) In addition, on 15 March 2021 the Commission received a submission from the Polish national competition authority UOKiK, putting forth general concerns about the Proposed Transaction due to the fact that ‘[t]he market for waste disposal is highly concentrated and we have spotted some competition problems in the past. Since it is the biggest transaction in this market in Poland in years we needed to express our concerns that it may worsen the situation on a general level.’

(94) However, on the basis of the information submitted by the Notifying Party, the Proposed Transaction would not result in affected markets for waste management services within Poland under any plausible product or geographic market definition. UOKiK’s submission does not contain information supporting another conclusion; in fact, it does not raise merger-specific concerns or even allege the existence of affected markets in Poland.119 Furthermore, UOKiK attached two studies120 to its submission which contain market share estimates, including those of the Parties, which do not rise to the level of affected markets under the meaning of the Form CO.121 Rather, UOKiK’s concern relates to the fact that in spite of the high number of competitors in Poland, many local authorities receive no more than one bid when organising tenders. The Proposed Transaction will not materially worsen this situation due to the Parties’ limited competitive position in Poland (whether at the local, regional, or national level). Finally, the market investigation did not elicit any information that could point to the existence of affected markets for waste management services in Poland, nor did the Commission receive any additional complaints in relation to the Polish market. For that reason, the possible impact of the Proposed Transaction for the Parties’ waste management activities in Poland will not be further discussed in this Decision.

5.1. Horizontal non-coordinated effects – sorting of Dutch LWP

(95) The Proposed Transaction raises concerns in relation to horizontal non-coordinated effects in the sorting of Dutch LWP. The Commission’s concerns result from (i) the Parties and competitors’ position in the relevant market, (ii) the closeness of competition, (iii) the spare capacity in the market, (iv) the structure of demand for the sorting of LWP, and (v) the barriers to entry or expansion.

5.1.1. Structure of supply: the Parties and competitors’ position in the relevant market.

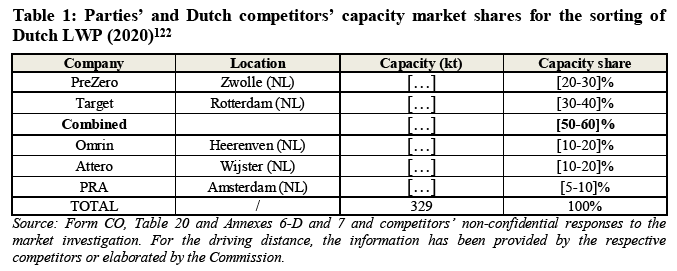

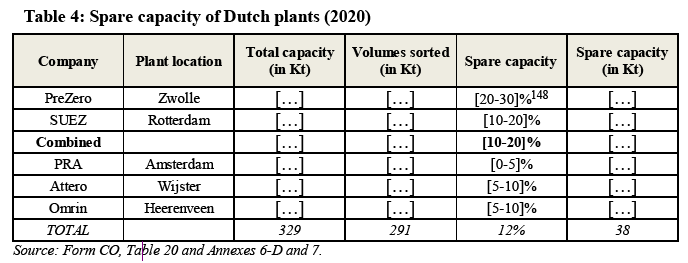

(96) Within the Netherlands there are 5 competitors (each of the Parties, Omrin, Attero and PRA) for the sorting of LWP. Table 1 below shows each sorter’s plant, its capacity, and its capacity market share.

(97) According to the above Table, the Parties would control almost [50-60]% of the capacity in the Netherlands for the sorting of LWP. It should be noted that this figure underestimates the Parties’ position since, as explained in paragraph (111), a significant part ([…] kt, i.e. almost half) of Omrin’s capacity is dedicated to sorting the LWP generated by its own municipalities,123 which means that the portion of its capacity actually available for the merchant market would be significantly lower (around […] kt, instead of the […] kt mentioned in the Table above).

(98) These figures differ from those provided by the Notifying Party, which pointed to a significantly lower combined market share. Notably, the Notifying Party has provided capacity market shares taking into account next to the Dutch LWP sorting plants also the entire capacity of the five German plants that serve the Dutch LWP sorting market.124 On this basis, the Parties’ combined market share in terms of capacity would be [20-30]%. The Commission, however, considers that these shares overestimate the competitive strength of German LWP sorting plants, since most of their capacity is used to serve the German market.125

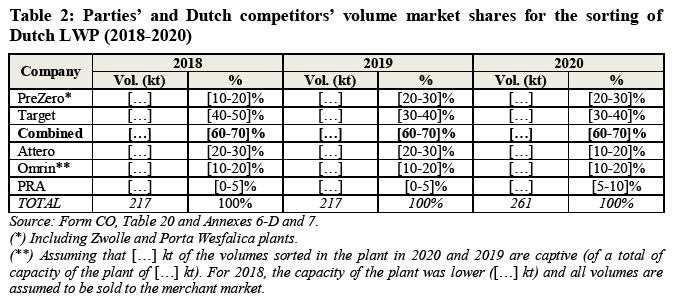

(99) The Commission considers that market shares based on the volumes of Dutch LWP effectively sorted by each market player provide a more accurate picture of the competitive situation in the market. Table 2 below shows for the Parties’ and their competitors’ plants located in the Netherlands the volumes of Dutch LWP sorted by each of them and their market shares for the last three years.

(100) The above Table shows that also in terms of volumes sorted in the Netherlands, the Proposed Transaction consists in the combination of the two largest competitors in the Dutch LWP sorting market. Post-transaction, the Parties’ combined market share considering only the Dutch LWP sorting plants would be [60-70]% in 2020, a percentage which has remained stable over the last three years. This market share would be more than […] points higher than that of its next competitor, Attero ([10-20]%), who would be the only remaining competitor with a market share higher than [10-20]%.

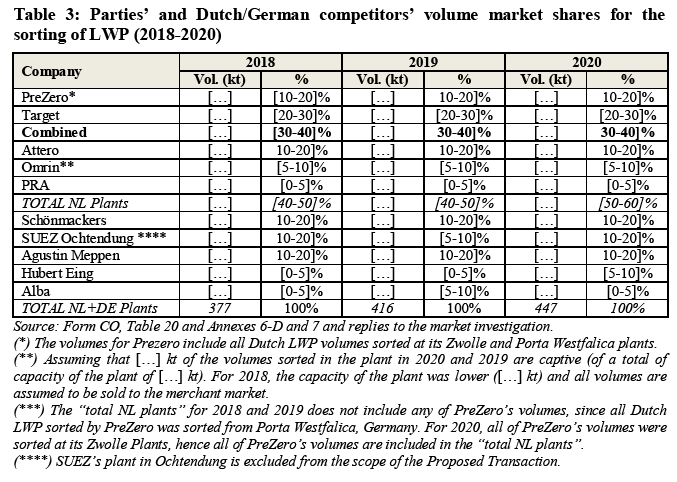

(101) The Notifying Party submits that the volumes of Dutch LWP sorted by plants in Germany should also be taken into account. If these were taken into account in the same manner as the volumes sorted by Dutch plants, the Parties would have a combined market share of [30-40]% in 2020 (see Table 3 below).

(102) Even if the volumes of Dutch LWP sorted by German LWP sorting plants were taken into account, the merged entity would, as the table above indicates, be the clear market leader, with almost three times the size of the next competitor, Schönmackers (who has a market share of [10-20]%, i.e. […] percentage points less). There would be no remaining competitors with a market share higher than [10-20]%.

(103) In conclusion, regardless of whether only competitors located in the Netherlands, or also competitors located in Germany, are taken into account, the Proposed Transaction would combine the two largest competitors in the market and would result in the combined entity becoming the clear market leader, with a considerable lead over any competitor.

(104) As a caveat to the latter scenario (i.e. considering both Dutch and German LWP sorters), the Commission notes that, as explained in detail in Section 5.1.2, German LWP sorting plants cannot be deemed to exercise an equivalent competitive constraint to LWP sorting plants located in the Netherlands. The former are out-of- market players which are more distant competitors to the Parties than other Dutch plants or than the Parties are to each other. Notably, as already mentioned above in Section 4.2.2.2, German LWP sorters face costs and barriers that Dutch customers do not face and customers in the Netherlands have a preference for LWP to be sorted in the country, which places German plants at a competitive disadvantage. Moreover, as explained in Section 5.1.3, the constraint that each player can exert in this market is largely determined by its spare capacity. As such, the volume market shares including Dutch and German LWP sorters underestimates the merged entity’s market power post-transaction.

5.1.2. Closeness of competition Notifying Party’s view

(105) The Notifying Party argues that the Parties do not compete closely, as their activities are largely complementary from a geographic perspective. Notably, given that their LWP sorting facilities are far away from each other, the Notifying Party argues that they do not compete as closely with respect to customers closer to one of the facilities, since in some cases customers may decide to go to the nearest facility.126

Commission’s assessment

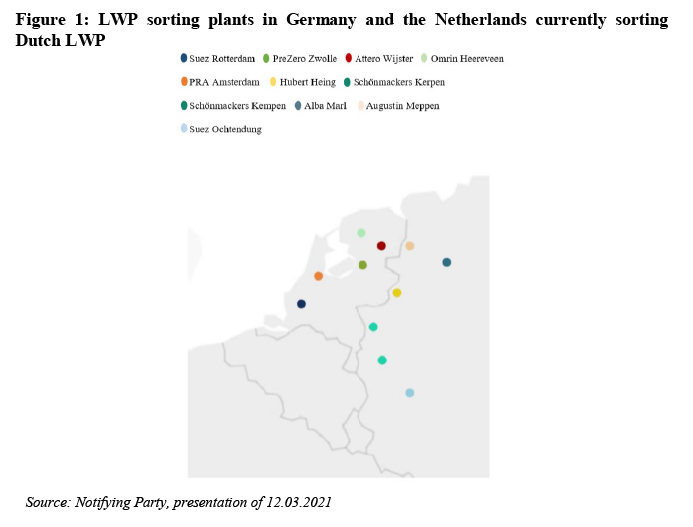

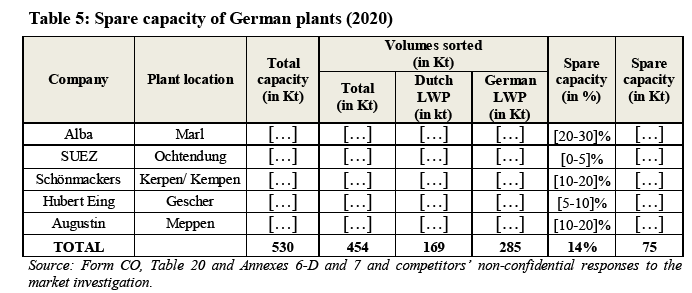

(106) As a preliminary note, the Commission will assess the closeness of competition between those LWP sorters which currently serve the Dutch LWP sorting market. These competitors include five Dutch entities (each of the Parties, Attero, Omrin and PRA), as well as five out-of-market competitors with plants located in Germany close to the Dutch border (SUEZ,127 Augustin, Hubert Eing, Alba and Schönmackers) for the sorting of Dutch LWP.128 Figure 1 below shows the location of all of these plants.

(107) This Section addresses closeness of competition between these competitors by analysing (i) the capacity, location of the plants and business models of the different market players, and (ii) the perceived closeness as per the market investigation.

(A) Capacity, location and business models of LWP sorting plants

(108) The characteristics of the demand for LWP sorting reflect customers’ particular attention to the ability of sorters to meet their requirements, both in terms of capacity and distance to the LWP sorting plant. Furthermore, the different business models in place, in terms of customer focus or type of operations, have an impact on the Parties’ and their competitors’ competitive interactions. The analysis of the capacity, business models and location of the plants of the different players available to sort Dutch LWP suggests that the Parties compete particularly closely.

(109) Concretely, the Parties own the two largest plants in the Netherlands in terms of capacity ([…] kt and […] kt respectively). These plants are respectively located slightly north and south of the most populated area of the country (encompassing the provinces of North Holland, South Holland and Utrecht) and close to the largest cities (Rotterdam, The Hague, Amsterdam).

(110) In contrast, the plants of all the other competitors in the Netherlands have significantly less capacity, are less centrally located (with the exception of a much smaller plant in Amsterdam) and their business models also differ significantly:

(111) Omrin’s plant is the largest facility on the market after the Parties’ plants.129 However, its capacity ([…] kt) is […]% less than PreZero’s and […]% less than SUEZ’s, whereas the difference in capacity between the Parties’ Zwolle and Rotterdam plants is only roughly […]%. Furthermore, Omrin is a public entity, owned by 33 municipalities in the North of the country.130 Omrin focuses its activity in serving municipalities in that area.131 Notably, almost half of the capacity of its sorting plant ([…] kt) is used to sort the LWP generated by its 33 municipalities.132 Therefore, the capacity which Omrin can dedicate to the merchant market – where it competes with the Parties – is limited (around […] kt, i.e. less than […]% of PreZero’s current capacity and less than […]% of SUEZ’s capacity). In addition, Omrin focuses mainly on serving its shareholders in specific regions in the North whereas SUEZ’s plant is geographically close to municipalities in the South of the country due to its location in Rotterdam, and PreZero’s plant at Zwolle is located in the centre of the country at a short distance from the main urban areas.

(112) Attero owns the fourth largest plant in the country, located in the province of Drenthe, also in the north of the country (which, like Omrin makes it a less close competitor). Its capacity ([…] kt), however, is limited when compared to the Parties’ ([…]% less than PreZero’s capacity in its Zwolle plant and almost […] of SUEZ’s Rotterdam capacity).

(113) PRA owns a relatively small plant of […] kt close to Amsterdam. PRA is part of Umincorp, a company originating from a project by the Resources and Recycling Group of Delft University of Technology which has developed the magnetic density separation (‘MDS’) technology, on which the plant is based. This technology allows PRA to achieve a higher recovery rate and an output of higher purity.133 Another specificity of PRA is that it sorts and recycles LWP in the same facility. The plant sorts LWP coming from the post-separation stream, and consequently it does not compete fully with the Parties (which sort both post-separated and source-separated LWP). In the market investigation it has been the only company singled out by customers as having a technology which stands out from the rest.134 One of the main customers has indicated that PRA’s new technology is new and promising but there presents a degree of uncertainty as to its effectiveness.135 Therefore, PRA would not constitute a close competitor to the Parties in view of its specific technology, its ability to combine sorting and recycling activities at its plant, its ability to compete only for part of the LWP and its very limited capacity.

(114) In addition, five competitors in Germany, with plants located close to the Dutch border, sort Dutch LWP (including SUEZ with its plant in Ochtendung). All these competitors combined have significant capacities. Concretely, SUEZ Ochtendung has a capacity of […] kt, Hubert Eing Gescher has […] kt, Augustin Meppen has […] kt, Alba Marl […] kt and Schönmackers Kerpen/Kempen […] kt. However, they sort significantly less volumes of Dutch LWP than the Parties (see Table 3) as most of their capacity is dedicated to German customers. The Commission considers that the competitive constraint exerted by these out-of-market competitors cannot be considered comparable to the constraint that the Parties exert on each other or that Dutch plants exert on the Parties, for the reasons explained below.

(115) First of all, for the reasons explained in Section 4.2.2.2, German competitors are in general at a competitive disadvantage in comparison to Dutch LWP sorting plants. This has been confirmed by all competitors active in the market which responded to the market investigation, which have indicated that there is a political preference for Dutch LWP to be sorted in the Netherlands.136 In general, Dutch customers seem to resort to out-of-market competitors only to the extent that there is not available capacity in local plants. This weaker competition exerted by out-of-market plants is reflected in the evolution of the market shares. Table 3 shows that, as Dutch players have increased capacity in the last three years (PreZero’s and PRA’s new plants, expansion of Omrin’s plant), there has been a decline in the proportion of LWP sorted in German plants (from 53% in 2018 to 42% in 2020),137 despite the fact that the latter have also expanded.138 In other words, the proportion of Dutch LWP sorted in plants located in the Netherlands has increased in two years from 47% to 58%. In the Commission’s view, this is an indication that, when available, Dutch customers turn to local capacity, while German sorters are used to adjust for Dutch capacity constraints and therefore serve the demand not served domestically. This also explains why Schwarz decided to build a sorting plant in Zwolle to sort Dutch LWP when it had capacity to do it in its plant in Germany and why German competitors do not expect an increase in the volumes of Dutch LWP to be sorted by them in the next years.139

(116) Second, the Commission observes that all these plants are significantly more distant to the western area of the country (where the Parties’ plants are located). As already described in Section 4.2.2.2(A), a majority of respondents to the market investigation – and all German competitors – have indicated that the maximum distance within which it is economically viable to transport LWP collected in the Netherlands is 200 km. The Commission notes in this regard that most of the capacity of German competitors is located at more than 200 km from the main cities in Western Netherlands. For example, Alba’s plant in Marl – which is the largest competing German plant in terms of capacity – is located 230 km from Rotterdam (where the Target’s plant is located), 237 km from The Hague, and 215 km from Amsterdam. SUEZ’s Ochtendung plant is more than 330 km from Rotterdam and Amsterdam, and Schönmaker’s plant in Kerpen would be 250 km from Amsterdam and 240 km from Rotterdam. Therefore the fact remains that, regardless of the identified technical administrative barriers and of customer preference, most of the capacity of the German plants cannot compete for the LWP collected in Western Netherlands (the most densely populated part of the country) as intensely as the Parties currently do. In fact, a German competitor pointed out that the contracts awarded by their Dutch customer concerned LWP collected in the Eastern provinces of the country – closer to the German border – and expressly indicated that it would not be capable of competing for the sorting of LWP collected further inland.140

(117) In view of the above, the Commission considers that German competitors are likely to be economically less efficient than the Parties (or other Dutch plants), at least when bidding for contracts for the sorting of LWP in the western part of the country or for contracts where a relevant proportion of the LWP is collected in that area.

(118) Third, besides being economically less competitive, plants located at greater distances from the collection points than the Parties’ plants may also be seen as environmentally less efficient than the local ones. As explained in Sections 4.2.2.2(A) to 4.2.2.2(C), distance is also a relevant factor for customers when assessing the environmental efficiency or transport sustainability of the different offers submitted in a tender. Longer transport distances imply more CO2 emissions and therefore higher long-term environmental costs. Customers accounting for close to half of demand openly admitted this preference, citing reasons linked to sustainability and environmental reasons and, expressly, the need to reduce CO2 emissions and to minimise environmental costs.141