GC, 2nd chamber, July 14, 2021, No T-648/19

GENERAL COURT

Judgment

Dismisses

PARTIES

Demandeur :

Nike European Operations Netherlands BV, Converse Netherlands BV

Défendeur :

European Commission

COMPOSITION DE LA JURIDICTION

President :

V. Tomljenović (Rapporteur)

Judge :

P. Škvařilová Pelzl, I. Nõmm

Advocate :

R. Martens, D. Colgan

THE GENERAL COURT (Second Chamber),

Background to the dispute

1 On 30 July 2013, the European Commission sent a request for information to the Kingdom of the Netherlands regarding its tax ruling practice.

2 On 24 January 2014, the Commission requested information regarding the advance pricing agreements (‘APAs’) concluded, inter alia, with Nike group companies.

3 The Kingdom of the Netherlands sent the requested information to the Commission on 17 February 2014.

4 On 22 November 2017, the Commission sent a further request for information to the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

5 After having obtained an extension of the deadline for replying to that further request for information, the Kingdom of the Netherlands supplied the requested documents on 22 January 2018.

6 On 26 January 2018, the Commission informed the Kingdom of the Netherlands that information was missing.

7 On 14 February 2018, further documents were sent by the Kingdom of the Netherlands to the Commission.

8 On 5 March 2018, the Commission again informed the Kingdom of the Netherlands that the missing information had not been provided.

9 After the missing information was provided on 19 March 2018, the Commission requested further documents on 14 May 2018, which were provided by the Kingdom of the Netherlands on 12 June and 31 October 2018.

10 On 20 November 2018, a bilateral meeting was held between the Commission and the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the context of the preliminary investigation as to whether the APAs complied with State aid law.

11 At the end of that preliminary investigation, the Commission reached the conclusion that the Kingdom of the Netherlands had granted State aid to two companies of the Nike group that was unlawful and incompatible with the internal market, contrary to Article 107 TFEU.

12 On 10 January 2019, the Commission opened the formal investigation procedure provided for in Article 108(2) TFEU by Decision C(2019) 6 final on State aid SA.51284 (2018/NN) Netherlands – Possible State aid in favour of Nike (‘the contested decision’). By the publication of that decision in the Official Journal of the European Union on 5 July 2019 (OJ 2019 C 226, p. 31), the Commission invited interested parties to submit their comments pursuant to that provision.

The contested decision

Nike group companies

13 In the contested decision, the Commission provisionally concludes that the Kingdom of the Netherlands granted State aid by means of APAs issued by the Netherlands tax administration for the benefit of Nike European Operations Netherlands BV (‘NEON’) in 2006, 2010 and 2015, and of Converse Netherlands BV (‘CN’) in 2010 and 2015 (‘the measures at issue’).

14 The applicants, NEON and CN, are two Netherlands subsidiaries of a Netherlands holding company, Nike Europe Holding BV (‘NEH’). NEH is owned by Nike Inc., which is established in the United States. The applicants have, since 2006 in the case of NEON and since 2010 in the case of CN, operated as the respective distributors of Nike and Converse products in the Europe, Middle East, and Africa (‘EMEA’) region.

Measures at issue

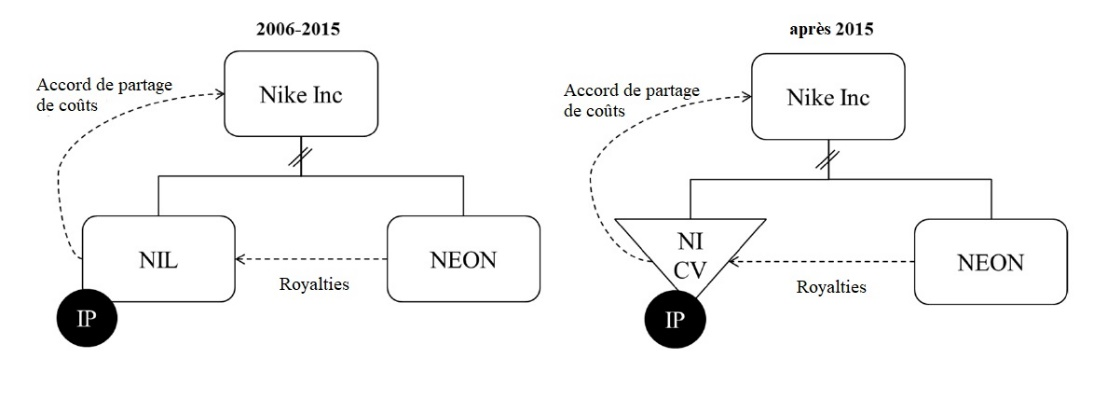

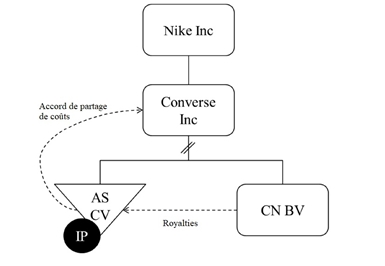

15 As is apparent in particular from paragraphs 38 and 138 of the contested decision, the measures at issue relate to the pricing, for tax purposes, of tax deductible royalties paid by NEON to Nike International Ltd (‘NIL’), then to Nike International CV (‘NI’), and by CN to All Star CV (‘AS’) in return for the grant of licences to use intellectual property (‘IP’) rights related to Nike and Converse products, respectively, in the EMEA region.

16 Those measures validate, for tax purposes, a transfer pricing arrangement, in particular the level of royalties payable by the applicants. In accordance with paragraphs 41 and 49 of the contested decision, the level of annual royalties corresponds, in essence, to the difference between the total revenues and a proportion of the applicants’ operating margin, sufficient, according to the measures at issue, to remunerate their activities. The level of annual royalties can then be used to determine the applicants’ annual taxable revenue in the Netherlands, in that the royalties are deductible, in accordance with the measures at issue, from the applicants’ taxable revenue.

17 So far as NEON’s situation is concerned, the contested decision refers to three APAs.

18 The first APA, dated 29 November 2006, followed on from an agreement between NEON and NIL, dated 1 June 2005, for the exclusive distribution of Nike goods in the EMEA region, together with a licence to use the IP rights related to those goods. Under that agreement, NEON was authorised to manufacture Nike products and to subcontract the manufacture of those products. The royalty payable by NEON to NIL for the exploitation of the IP rights transferred was to correspond to the difference between the operating profit of NEON and 2 to 5% of its total revenues.

19 The second APA, dated 1 October 2010, replaced the first APA and followed on from a request by NEON of 21 May 2010 that was triggered in particular by the modification of part of its activities. According to the contested decision, the licence agreement was amended with effect from 1 June 2008 and two amendments were made concerning the increase of the royalty rate paid by NEON to NIL and an extension of the list of countries in the EMEA region for which NEON was designated as the exclusive licensee for products covered by the IP rights transferred.

20 By that second APA, the Netherlands tax administration confirmed its conclusions of 29 November 2006, focusing on NEON’s routine distribution activities. According to the contested decision, it added that NIL would bear the greatest risk, as legal owner of the IP rights transferred. Last, it expressly favoured the transactional net margin method for determining that NEON’s remuneration complied with the arm’s length principle and concluded, as in the first APA, that the remuneration for NEON’s activities complied with the arm’s length principle if it had obtained an operating margin of 2 to 5% of total revenue.

21 In the light of the expiry of the second APA on 31 May 2015, NEON requested the renewal of the APA on 31 March 2015, which resulted in the conclusion of a third APA dated 28 May 2015. According to the contested decision, the new APA reiterated the conclusions of the second APA. The Netherlands tax administration had, however, supplemented its study of NEON’s activities owing, inter alia, to the development of financing-related activities and e-commerce. It thus stated, first, that the remuneration for NEON’s activities complied with the arm’s length principle if it had obtained an operating margin of 2 to 5% of total revenue. Second, as regards e-commerce, the tax administration added that a remuneration of 1 to 5% of total revenue complied with the arm’s length principle.

22 In the contested decision, the Commission also notes that, in 2015, NEON was essentially granted two royalty-free licences by NEH for the use of IP rights in products of Nike and affiliates outside the United States and the EMEA region. Those licences were subsequently granted by NEON to third-party companies against payment of royalties at a rate of 5 to 20% on sales.

23 So far as CN’s situation is concerned, the contested decision refers to two APAs.

24 The first APA, dated 15 February 2010, followed on from a request by CN the purpose of which was to verify that its remuneration complied with the arm’s length principle. According to the contested decision, the report annexed to that APA indicated that CN’s distribution activities could be considered routine as compared to those of AS. AS also bore the greatest risk in the context of the transaction in question. Furthermore, the tax administration favoured the transactional net margin method for the purpose of determining whether the remuneration of CN complied with the arm’s length principle. In that context, it concluded that obtaining an operational margin of 2 to 5% of total revenue was considered to be consistent with that principle. Last, the APA confirmed that CN could deduct from its taxable revenue the royalty paid to AS for the transfer of IP rights.

25 The second APA, dated 7 September 2015, which replaced the first, followed on from a further request by CN. According to the contested decision the Netherlands tax administration considered, just as it did in the first APA, that AS would bear the greatest risk in the context of the transaction at issue. The distribution activities of CN were also described as routine. Apart from an adjustment of the level of CN’s operating margin, the tax administration also applied the transactional net margin method and concluded that CN’s remuneration complied with the arm’s length principle if it had obtained an operating margin of 2 to 5% of the estimated principal revenue.

26 The following two diagrams, taken from the contested decision, illustrate the structures established:

Provisional assessment of the existence of State aid

27 According to the Commission’s provisional assessment in the contested decision, the APAs were imputable to the Netherlands tax administration and, therefore, to the Kingdom of the Netherlands. They also conferred a selective advantage, in that the corporate income tax for which the applicants were liable in the Netherlands was calculated on the basis of an annual level of profit lower than it would have been if those companies’ intra-group transactions had been priced at arm’s length for tax purposes. The amount of royalties owed by the applicants did not correspond to the amount that would have been negotiated under market conditions for a comparable transaction between independent companies.

28 More specifically, as regards, in the first place, the conferral of an advantage, the Commission states, in paragraphs 82 to 137 of the contested decision, that the measures at issue confer an advantage on the applicants in the form of a reduction of their taxable revenue.

29 It recalls that the arm’s length principle aims to reflect the economic realities of transactions between entities of the same group, in such a way as to render them comparable to transactions between independent entities.

30 In order to ensure that that principle is observed, it emphasises in paragraph 85 of the contested decision that it is important, first, to determine precisely the nature and specific features of relations between the group entities concerned and, second, to identify, in the light of the particular circumstances of each case, the appropriate method of calculation for determining whether the transactions at issue have been priced at arm’s length.

31 In the present case, as is apparent from paragraph 87 of the contested decision, the Commission observes that the documents provided by the Netherlands authorities in the course of the preliminary investigation did not enable it to identify precisely the transactions for which an APA had been requested or their added value, which had given it reason to doubt that the transactions at issue complied with the arm’s length principle.

32 According to the contested decision, it is apparent from the information received only that the transactions at issue concerned the payment of royalties by the applicants in return for a licence to use IP rights related to Nike and Converse products and, moreover, that the Netherlands tax authorities’ preferred method of calculation was the net margin method.

33 Principally, the Commission expresses doubts, in paragraph 88 of the contested decision, as to the way in which the net margin method was applied by the Netherlands tax administration in this case. Unlike the latter, the Commission considers that it would have been more appropriate to take into account the financial situation of the companies that granted the licences, NIL and NI, rather than that of the licensee companies, that is to say, the applicants.

34 According to the Commission the net margin method can only be applied, for a particular transaction, to the party responsible for the least complex activities. If a company carries out routine activities, uses conventional assets, assumes limited risks and does not contribute to an essential part of the controlled transaction, such a company will be regarded as the company to whose financial situation the net margin method will be applied.

35 In the present case, the Commission notes, in particular in paragraphs 101, 103, 109, 114, 116, 120 and 122 of the contested decision, that the applicants’ activities cannot be described as routine distribution activities. They seem to assume the greatest risk and to participate actively in the development of products in respect of which IP rights were transferred to them, so that the net margin method should, in the present case, have been applied in the light of the financial situation of the transferring companies. The Commission adds that if the Netherlands tax administration had applied the net margin method by taking the latter companies as a benchmark, it would have arrived at a lower royalty and, as a result, at a higher taxable revenue for the applicants.

36 Such a reading is, according to the Commission, corroborated by the analysis of the 2018 review, sent by the Kingdom of the Netherlands, relating to the payments made in the period 2007‑2017 in connection with the licensing of IP rights to NEON. In paragraph 123 of the contested decision, the Commission states that that review does not contain detailed information about the functions performed by each of the parties to the licence agreement. The Commission also finds, on the basis of that review, that since NIL and NI have no employees, they cannot exercise the strategic direction functions which the report claims they performed for the benefit of NEON.

37 In the alternative, in the light in particular of paragraphs 126 to 131 of the contested decision, the Commission also doubts the relevance of the net margin method. The Netherlands tax administration did not verify that there were, in the present case, comparable transactions between independent entities, which, had that been verified, would have enabled the comparable price method to be used. The documents provided indicate, moreover, that comparable transactions may have existed and that the taxable base of the applicants could have been higher.

38 Likewise, in the absence of comparable transactions between independent undertakings, the Commission makes clear that the profit split method would have been more appropriate than the net margin method, which, again, would have led to an increase in the taxable revenue of the applicants.

39 On the other hand, in paragraph 133 of the contested decision, the Commission takes the view, assuming the net margin method and its application to the applicants to be pertinent, that it was not appropriate to take into account, as a profit level indicator, the operating margin calculated on the basis of the total revenue of those companies.

40 Only the income generated by the licence agreements concerned should have been taken into account, not income generated otherwise. The applicants had received revenue, according to the Commission, derived from the sub-licensing to third parties and other group companies of non-EMEA IP rights. Moreover, taking total revenue into account had led, according to the Commission, to the artificial inflation of the amount of royalties paid by the applicants and, in consequence, to a reduction of their taxable revenue.

41 As regards, in the second place, the selectivity of the measures at issue, besides the presumption of selectivity for individual aid, the Commission shows that the APAs afford the applicants preferential treatment as compared to other companies liable to pay corporate income tax in the Netherlands, whether integrated or not.

42 More specifically, in so far as the measures at issue are individual measures, and in accordance with settled case-law, the Commission states, primarily in paragraphs 138 to 140 of the contested decision, that it is in a position provisionally to presume that those measures are selective. The Commission considers that the measures at issue confer a tax advantage on the applicants. It states, moreover, that the measures are individual measures. They validate, directly, the applicants’ taxable revenue and indirectly determine the price of an intra-group transaction to which the applicants are a party. Those measures concern the tax situation of the applicants only and can only be used by them in that context.

43 In paragraph 139 of the contested decision, the Commission also observes that, in relation to tax rulings, the identification of an advantage and the assessment of the selectivity of those measures are closely linked. The identification of an advantage requires verification of the tax treatment of transactions concluded in particular between independent companies. In the present case, the provisional finding of an advantage means that the measures at issue favour the applicants in comparison to independent companies and to companies forming part of a group that make their intra-group transactions subject to the arm’s length principle.

44 In the alternative, in paragraphs 142 to 150 of the contested decision, the Commission notes that the measures at issue confer a selective advantage, in that they derogate from two different reference frameworks.

45 First, in the light of a reference framework that extends to the Netherlands rules on corporate income tax, the Commission concludes that the measures at issue afford the applicants preferential treatment, in so far as, unlike companies subject to corporate income tax, the applicants are taxed on a level of profit that does not reflect market prices. The Commission explains in that respect that integrated and non-integrated companies are in a comparable situation in the light of the objective of the corporate income tax.

46 Second, in the light of a reference framework limited to Article 8b(1) of the Wet op de vennootschapsbelasting (Netherlands Law on corporate income tax, ‘the CIT’), as set out in paragraph 62 of the contested decision and which codifies the arm’s length principle in Netherlands tax law, the measures at issue should still, according to the Commission, be regarded as conferring a selective advantage. Unlike other integrated companies, the applicants enjoy preferential treatment, according to the Commission, in that they remain able to price their intra-group transactions at prices that are not in accordance with the arm’s length principle.

47 Besides the fact that the Kingdom of the Netherlands has not put forward any objective justification in relation to the preferential treatment of the applicants, the Commission thus observes that the State aid appears provisionally, in the absence of prior notification, to be both unlawful and incompatible.

48 In the light of the preliminary assessment of the APAs and in order to investigate further their compatibility with State aid law, the Commission sent a number of requests for information to the Netherlands by means of the contested decision.

Procedure and forms of order sought

49 On 26 September 2019, the applicants brought the present action.

50 On 12 December 2019, the Commission sent the defence to the General Court Registry.

51 On 7 May 2020, the applicants submitted a request, in accordance with Article 106(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, to be heard in an oral hearing, which was held on 25 January 2021.

52 The applicants claim that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

53 The Commission contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicants to pay the costs.

Law

54 Formally, the applicants put forward three pleas in law in support of their action.

55 The first plea alleges breach of Article 107(1) and Article 108(2) TFEU, Article 1(d) and (e) and Article 6 of Council Regulation (EU) 2015/1589 of 13 July 2015 laying down detailed rules for the application of Article 108 TFEU (OJ 2015 L 248, p. 9), Article 41(1) and (2) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (‘the Charter’), and the principles of good administration and equal treatment.

56 The second plea alleges breach of the second paragraph of Article 296 TFEU, Article 41(1) and (2)(c) of the Charter, Article 107(1) and Article 108(2) TFEU, and Article 6(1) of Regulation 2015/1589.

57 By the third plea, the applicants rely on breach of the second paragraph of Article 296 TFEU, Article 41(1) and (2)(c) of the Charter, Article 107(1) and Article 108(2) TFEU, and Article 6(1) of Regulation 2015/1589.

58 Each plea in the action is divided, in essence, into several parts.

59 The first plea is in three parts, alleging, first, an incorrect assessment of the character of the alleged aid; second, an incorrect assessment of the nature of an APA in Netherlands law; and, third, breach of the principles of good administration and equal treatment.

60 The second plea is divided, in essence, into two parts, alleging, first, breach of the obligation to state reasons; and, second, an incorrect assessment of selectivity.

61 The third plea is in three parts, alleging, first, breach of the obligation to state reasons; second, breach of the applicants’ procedural rights; and, third, premature initiation of the formal investigation procedure.

62 It is thus appropriate to consider the merits of all of the pleas advanced in support of the action by first examining the first part of the second and third pleas, alleging breach of the obligation to state reasons.

First part of the second and third pleas, alleging breach of the obligation to state reasons

63 The applicants claim, in the present case, that the contested decision lacks sufficient reasoning in that it fails to mention the relevant issues of fact and law or the reasons for concluding that the measures at issue fulfil the conditions laid down in Article 107(1) TFEU. They submit that the same is also true of the assessment that the measures at issue are selective.

64 First, the Commission merely asserts, rather than demonstrates, that the measures at issue are individual measures, which is contrary to its most recent practice in taking decisions.

65 The fact that the measures at issue concern the applicants’ tax situation and can be used by them to assess their corporate income tax liability is not sufficient for that purpose. Therefore, given the incomplete nature of its analysis, the Commission cannot conveniently resort to the presumption of selectivity for individual measures.

66 The Commission also fails to justify, when seeking in particular to establish that the measures at issue are selective, the failure to take into account the declaratory nature of those measures and the fact that other companies have a company structure similar to the applicants’, including some one hundred companies with similar APAs.

67 Second, the contested decision is based on ambiguous reasoning and contains internal inconsistencies that prevent a proper understanding of the reasons underlying it. Studying selectivity through the prism of three non-complementary but substitutable options emphasises the equivocal nature of the contested decision. Nor does the Commission indicate why it is possible to conclude that the applicants, unlike the other companies in a comparable situation, received preferential treatment.

68 Third, in the applicants’ submission, the contested decision contains no indication that, when the Commission published that decision, it was not in a position to overcome the difficulties encountered, on the basis of the information at its disposal.

69 In that regard, it is apparent from settled case‑law that the statement of reasons required by the second paragraph of Article 296 TFEU must be appropriate to the measure at issue and must disclose in a clear and unequivocal fashion the reasoning followed by the institution which adopted the measure in such a way as to enable the persons concerned to ascertain the reasons for the measure and to enable the court having jurisdiction to exercise its power of review (see judgments of 15 July 2004, Spain v Commission, C‑501/00, EU:C:2004:438, paragraph 73 and the case-law cited, and of 22 January 2013, Salzgitter v Commission, T‑308/00 RENV, EU:T:2013:30, paragraph 112 and the case-law cited).

70 The requirements to be satisfied by the statement of reasons depend on the circumstances of each case, in particular the content of the measure in question, the nature of the reasons given and the interest which the addressees of the measure, or other parties to whom it is of direct and individual concern, may have in obtaining explanations (see judgment of 22 January 2013, Salzgitter v Commission, T‑308/00 RENV, EU:T:2013:30, paragraph 112 and the case-law cited).

71 It is not necessary for the reasoning to go into all the relevant facts and points of law, since the question whether the statement of reasons meets the requirements of the second paragraph of Article 296 TFEU must be assessed with regard not only to its wording but also to its context and to all the legal rules governing the matter in question (see judgments of 15 July 2004, Spain v Commission, C‑501/00, EU:C:2004:438, paragraph 73 and the case-law cited, and of 22 January 2013, Salzgitter v Commission, T‑308/00 RENV, EU:T:2013:30, paragraph 113 and the case-law cited).

72 It must also be noted that, in the present case, the contested decision is a decision by which the Commission decided to initiate the formal investigation procedure, as provided for in Article 108(2) TFEU. That decision brings to a close the preliminary examination stage. Accordingly, the Commission’s assessment of the measures at issue is not definitive and may evolve during the formal procedure for obtaining additional information from the Kingdom of the Netherlands and any interested parties.

73 In accordance with Article 6(1) of Regulation 2015/1589, the contested decision must simply summarise the relevant issues of fact and law, include a preliminary assessment as to the aid character of the proposed measure and set out the doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market. The decision must give the Member State concerned and other interested parties the opportunity to participate effectively in the formal investigation procedure.

74 For that purpose, it is sufficient for them to be aware of the reasoning which led the Commission provisionally to conclude that the measure at issue might constitute new aid incompatible with the internal market (see, to that effect, judgments of 21 July 2011, Alcoa Trasformazioni v Commission, C‑194/09 P, EU:C:2011:497, paragraph 102, and of 30 April 2002, Government of Gibraltar v Commission, T‑195/01 and T‑207/01, EU:T:2002:111, paragraph 138).

75 First, the applicants cannot complain that the Commission’s reasoning as regards the individual character of the measures at issue was incomplete. The contested decision contains a clear and unequivocal statement of reasons in that respect. It is apparent from paragraphs 38 and 138 of the contested decision that the measures at issue concern the applicants’ tax situation and can be used only by them to assess their corporate income tax liability in the Netherlands.

76 The same assessment applies as regards the absence, in the contested decision, of reasons relating to the possibility of there being an aid scheme from which the measures at issue may be derived.

77 The Commission chose, in the contested decision, provisionally to regard the measures at issue, in the light of paragraphs 38 and 138 of the contested decision, as individual aid, and their selectivity not in the light of the Netherlands tax ruling practice, but, as is clear from the contested decision, either in the light of the Netherlands system of corporate income tax or of Article 8b(1) of the CIT.

78 Nor can the absence of a specific statement of reasons in relation, first, to the failure to take into account allegedly similar APAs issued by the Netherlands tax administration in favour of other companies and multinational groups, and, second, to the allegedly declaratory nature of the APAs in Netherlands law, lead, on the basis of the obligation to state reasons, to the annulment of the contested decision.

79 The statement of reasons for the contested decision is not contradictory in that respect. While the Commission refers in paragraphs 81, 136, 137 and 141 of that decision to an aid scheme, it does not do so for the purpose of defining the measures at issue in such terms but in order to make clear that the demonstration of the selectivity of a measure, according to a three-step review, concerns above all measures that constitute an aid scheme.

80 It must, moreover, be pointed out that the obligation to state reasons is an essential procedural requirement, as distinct from the question whether the reasons given are correct, which goes to the substantive legality of the contested measure (judgment of 22 March 2001, France v Commission, C‑17/99, EU:C:2001:178, paragraph 35). In the present case, the Commission did in fact give reasons for its provisional assessment of the selective nature of the measures at issue. Failing to take similar APAs into account for that purpose is a matter that relates not to the statement of reasons for the contested decision but to the question as to whether its reasons are correct.

81 Consequently, the Commission did not fail to fulfil its obligation to state reasons by failing to set out reasons as to whether or not an aid scheme exists in the present case.

82 Second, contrary to the applicants’ assertion, the statement of reasons for the contested decision, in respect of the examination of the selectivity of the measures at issue, does not contain any internal inconsistency that would prevent a proper understanding of the reasons underlying that decision. Likewise, the Commission satisfied its obligation to state reasons with regard to assessing the comparability of the applicants’ situation with the situations of other undertakings.

83 First, while the Commission did intend to demonstrate the selectivity of the measures at issue in three different ways, the fact remains that those various approaches are substitutable. Each one, according to the Commission, enables the selective nature of the measures at issue to be provisionally demonstrated. It is also apparent from paragraphs 138 and 141 of the contested decision that those three approaches are presented to varying degrees, the first being presented as the primary approach, whereas the second and third are presented on a subsidiary basis.

84 Second, it is apparent from paragraph 149 of the contested decision that the Commission concluded that multinational groups were, like the applicants, in a comparable situation in that their intra-group transactions must be carried out, as a matter of principle, in accordance with the arm’s length principle; therefore a failure to state reasons cannot properly be relied upon in that respect.

85 Third, the contested decision is, it is claimed, vitiated by a failure to state reasons in so far as the Commission did not clearly set out the serious difficulties that justified initiation of the formal investigation procedure pursuant to Article 108(2) TFEU.

86 However, the Commission repeatedly expressed its doubts, in paragraphs 87, 89, 103, 126 or 130 of the contested decision, as to the conformity of the measures at issue with Article 107 TFEU, in particular with regard to the preferred method of calculation for the purposes of determining whether intra-group transactions complied with the arm’s length principle, and, in part 5 of the contested decision, as to the technical complexity of the underlying issues, which could not be properly resolved on the basis of the information provided by the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the course of the preliminary examination.

87 Consequently, the first part of the second and third pleas in law must be rejected as being unfounded.

Second part of the third plea, alleging breach of procedural rights

88 According to the applicants, the lack of clarity in the contested decision and its many deficiencies did not make it possible either to intervene effectively during the formal investigation procedure or to identify clearly the interested parties. The brief statement of reasons in the contested decision limited the ability of those parties to defend their position during the formal investigation procedure, in particular as regards the failure to extend the investigation to include a broader group of potential beneficiaries.

89 First, the argument put forward by the applicants in the present case is based on the erroneous premiss that the contested decision is vitiated by a failure to state reasons.

90 Second, as beneficiaries of the measures at issue and thus as interested parties, the applicants are in a position to send their comments to the Commission during the formal investigation procedure. Accordingly, they do have procedural rights and cannot claim that, in adopting the contested decision, the Commission breached them.

91 Consequently, the second part of the third plea in law must be rejected as being unfounded.

First and second parts of the first plea, alleging manifest errors of assessment

92 In the application, the applicants claim, in essence, that the Commission made manifest errors of assessment, first, by failing to extend the preliminary examination to cover the existence of a possible aid scheme and, second, by mischaracterising the nature of an APA in Netherlands law.

Failure to identify an aid scheme

93 The applicants claim, in essence, that the facts on which the contested decision is based should have led the Commission to investigate as a priority the existence of an aid scheme, within the meaning of Article 1(d) of Regulation 2015/1589.

94 Evidence of such a scheme is provided, first, by the adoption by the Netherlands tax administration of some 98 APAs similar to those of the applicants and, second, the fact that some 700 companies in the Netherlands have a company structure similar to that of the applicants. If the Commission had extended its analysis to include the other APAs instead of arbitrarily focusing on the measures at issue, it would have found that there was no advantage benefiting only the applicants.

95 That conclusion is supported by the purely confirmatory and declaratory nature of the APAs. Tax rulings do not constitute a prerequisite for operating in the Netherlands or for applying the arm’s length principle, but provide confirmation that their beneficiary is operating in accordance with Netherlands tax law.

96 APAs do not, therefore, lead to the application contra legem of Article 8b(1) of the CIT. The applicants are taxed not on the basis of the measures at issue but of Article 8b(1) of the CIT; therefore those measures cannot be described as ‘further implementing measures’ within the meaning of Article 1(d) of Regulation 2015/1589.

97 The applicants add that even if Article 8b(1) of the CIT did not establish an aid scheme de jure, such a scheme could, on the basis of the information available to the Commission during the preliminary examination, be established de facto, in the same way as in Commission Decision C(2015) 563 final of 3 February 2015 on the excess profit tax ruling system in Belgium – Article 185§ 2(b) of the Code des impôts sur les revenus 1992 (Income Tax Code 1992, ‘CIR92’)), initiating the formal investigation procedure provided for in Article 108(2) TFEU, and by the publication of which in the Official Journal of the European Union of 5 June 2015 (OJ 2015 C 188, p. 24) the Commission invited interested parties to submit their comments pursuant to that provision. The Commission was thus, according to the applicants, in a position to identify an aid scheme by analysing a representative sample of APAs.

98 In other words, according to the applicants, the Commission should not have ignored the common use of APAs by numerous other companies in the Netherlands and should have assessed not the measures at issue, but rather whether Article 8b(1) of the CIT, which codifies the arm’s length principle in Netherlands law, should be considered the basis of an aid scheme.

99 It should be noted in that regard that, in order to avoid confusion between the administrative and judicial proceedings, and to preserve the division of powers between the Commission and the Courts of the European Union, any review by the General Court of the legality of a decision to initiate the formal investigation procedure must necessarily be limited. The General Court must in fact avoid giving a final ruling on questions on which the Commission has merely formed a provisional view (judgment of 23 October 2002, Diputación Foral de Guipúzcoa and Others v Commission, T‑269/99, T‑271/99 and T‑272/99, EU:T:2002:258, paragraph 48).

100 Thus, where, in an action against a decision to initiate the formal investigation procedure, the parties challenge the Commission’s assessment of a measure as constituting State aid, review by the General Court is limited to ascertaining whether or not the Commission has made a manifest error of assessment in forming the view that it was unable to resolve all the difficulties on that point during its initial examination of the measure concerned (judgment of 23 October 2002, Diputación Foral de Guipúzcoa and Others v Commission, T‑269/99, T‑271/99 and T‑272/99, EU:T:2002:258, paragraph 49).

101 In the present case, the applicants claim that the Commission made a manifest error of assessment by failing, on the basis of the facts underlying the present case, to investigate as a priority the existence of an aid scheme.

102 As the applicants correctly note, nowhere in the contested decision did the Commission determine whether or not such a scheme exists. The Commission focused, in particular in paragraph 38 of the contested decision, on the measures at issue in so far as they were only addressed to the applicants, without testing the assumption that there was an aid scheme from which those measures might have been derived.

103 That scheme might have arisen either de jure from Article 8b(1) of the CIT or de facto from a set of tax rulings indicating a systematic course of conduct on the part of the Netherlands tax administration. If no legal act establishing an aid scheme is identified, the Commission may rely on a set of circumstances which, taken as a whole, indicate the de facto existence of an aid scheme (see, to that effect, judgment of 13 April 1994, Germany and Pleuger Worthington v Commission (C‑324/90 and C‑342/90, EU:C:1994:129, paragraphs 14 and 15).

104 However, that cannot give rise to any manifest error of assessment. The Commission is entitled to treat a measure as being individual aid without being obliged to verify beforehand and as a matter of priority whether that measure may have been derived from such a scheme (see, by analogy, judgment of 9 June 2011, Comitato ‘Venezia vuole vivere’ and Others v Commission, C‑71/09 P, C‑73/09 P and C‑76/09 P, EU:C:2011:368, paragraph 63).

105 The allegedly declaratory nature of an APA in Netherlands law does not affect that finding. Assuming that declaratory nature is established, it does not, contrary to the applicants’ contention, in any way preclude the Commission from being able to treat an APA as being addressed to a taxpayer, without any examination, including at the end of the preliminary examination, of a possible scheme from which such an APA might be derived.

106 Accordingly, the first part of the first plea in law must be rejected as being unfounded.

The nature of an APA in Netherlands law

107 The applicants maintain, first of all, that the measures at issue are merely declaratory in nature and do not constitute a prerequisite for operating in the Netherlands or for using the arm’s length principle.

108 The applicants go on to explain that an APA cannot result in any special treatment for the addressee since taxes can only be imposed by law, the interpretation of which is the exclusive competence of the Netherlands judiciary. In their submission, if an APA resulted in any change to the tax situation of a taxpayer, it would infringe Netherlands tax law, and therefore, as a matter of principle, an APA must be regarded as not conferring any advantage.

109 Last, the Commission cannot conclude that the applicants have been granted a reduction in corporate income tax liability without first comparing their treatment with that of other companies under Article 8b(1) of the CIT.

110 In that regard, it is necessary to assess the merits of the arguments put forward by the applicants in the light of the case-law cited in paragraphs 99 and 100 above. In the present case, the applicants claim that the Commission erred in its assessment of the nature, in Netherlands law, of an APA, which could not in any event deviate from Netherlands tax law. In other words, the measures at issue cannot, as a matter of principle, be derogating measures and afford the applicants special treatment.

111 First, on the assumption, as the applicants claim, that an APA is declaratory in nature in Netherlands law, such a finding does not, as has been held in paragraphs 101 to 106 above, in any way preclude the Commission from treating an APA as an individual measure, without any examination in the decision initiating the formal investigation procedure of a possible aid scheme from which such an APA might be derived.

112 Second, for the purposes of the annulment of a decision initiating a formal investigation procedure, such an argument cannot be upheld. The assessment of an APA and its nature in Netherlands law raises serious difficulties that warrant a thoroughgoing examination by the Commission.

113 It is apparent, in essence, from the transfer pricing decrees of 2001 and 2013 referred to in paragraphs 63 to 66 of the contested decision that, when issuing an APA, the Netherlands tax administration comments on the method of calculation of transfer pricing which, in its view, will ensure that intra-group transactions will be charged at a price that accords with the arm’s length principle. Identifying the appropriate method as regards the application of the arm’s length principle accordingly requires an analysis of the transaction in question and of the financial situation of the parties to that transaction, which is all the more complex since one method of calculation can, in certain situations, produce better results than another and be more reliable in arriving at an arm’s length price.

114 In that context, and in accordance with the case-law of the General Court in relation to tax rulings, it is not, as a matter of principle, inconceivable that an APA might not be based on a method of calculation that enables a price equivalent to an arm’s length price to be reached (see, to that effect, judgment of 24 September 2019, Netherlands and Others v Commission, T‑760/15 and T‑636/16, EU:T:2019:669, paragraphs 151 to 160).

115 It is thus for the Commission to compare the taxable profit of the beneficiary of the APA in question as a result of the application of that APA with the position, as it would be if the normal tax rules under Netherlands law were applied, of an undertaking in a factually comparable situation, carrying on its activities in conditions of free competition. Against that background, although the APA in question accepted a certain level of pricing for intra-group transactions, it is necessary to check whether that pricing corresponds to prices that would have been charged under market conditions (see, to that effect, judgment of 24 September 2019, Netherlands and Others v Commission, T‑760/15 and T‑636/16, EU:T:2019:669, paragraph 153).

116 Consequently, having regard to the difficulties inherent in such an analysis, the initiation of the formal investigation procedure cannot reasonably be challenged.

117 On the other hand, the applicants maintain that the Commission should have compared their tax treatment with that of other companies in order to check whether they were receiving special treatment.

118 However, the issue in the present case is merely whether the applicants’ corporate income tax burden is reduced as a result of intra-group transactions being priced at a level that does not reflect an arm’s length price. If intra-group transactions are also calculated incorrectly for other companies, that is irrelevant to the conferral of an economic advantage on the applicants.

119 Furthermore, even if the Commission had been obliged, quod non, to open an investigation in respect of other undertakings to whom measures similar to those at issue in the present case apply, it must be borne in mind that the principle of equal treatment must be reconciled with the rule that a person may not rely, in support of his or her claim, on an unlawful act committed in favour of a third party (see, to that effect, judgment of 31 May 2018, Groningen Seaports and Others v Commission, T‑160/16, not published, EU:T:2018:317, paragraphs 115 to 118).

120 Accordingly, the second part of the first plea in law must be rejected as being unfounded.

Second part of the second plea, alleging an incorrect assessment of the selectivity of the measures at issue

121 The applicants complain, first of all, that the Commission made the incorrect principal assumption that the measures at issue were selective. The fact that an APA is issued in favour of a single company does not lead to the conclusion, in the present case, as the Commission contends, that it constitutes individual aid.

122 According to the applicants, such an assessment disregards the nature of an APA in Netherlands law. An APA is intended only to provide companies with certainty on the application of Netherlands tax laws. The issuing of an APA is not required for the application of Article 8b(1) of the CIT. The arm’s length principle applies by virtue of Netherlands tax law and APAs merely confirm compliance with Article 8b(1) of the CIT. The measures at issue are therefore merely illustrative of the general Netherlands practice in that regard.

123 Application of the arm’s length principle does not by any means require an APA to be concluded with the Netherlands tax administration; it is not a further implementing measure within the meaning of Article 1(d) of Regulation 2015/1589.

124 The Commission’s assessment fails to recognise, moreover, the widespread use in the Netherlands of company structures comparable to those of the applicants, and APAs issued by the Netherlands tax administration similar to those issued to the applicants. According to data made public in 2017, some 700 other companies operated in the Netherlands under a company structure comparable to that of the applicants and some 98 other companies obtained tax rulings similar to those of the applicants. Thus, the applicants were operating according to a general scheme that has its basis in Article 8b(1) of the CIT.

125 Next, the applicants contend that the Commission cannot, on the basis of the first subsidiary selectivity alternative, base its reasoning on the assertion that all companies are, as a general rule, subject to corporate income tax on their profits, and assess the selectivity of those measures in relation to all companies liable to pay that tax.

126 That argument might have been relevant if the measure was one that exempted its beneficiary from corporate income tax. Even in a scenario in which the Commission would consider the application of a different tax rate, the reference framework would in any event have to take account of provisions relating to the tax base, the taxable persons, the taxable event and the tax rate. Stating that all companies are subject to corporate income tax on their profits is a truism and does not enable the Commission to demonstrate, in the present case, the selectivity of the measures at issue.

127 Last, under the second subsidiary selectivity alternative, the Commission made a manifest error of assessment in contending that, due to the measures at issue, the applicants received preferential treatment since they were not subject to the arm’s length principle, when that principle is applied widely, independently of any APA. Similarly, the measures at issue cannot derogate from the arm’s length principle, since an APA cannot, as a matter of principle, lead to the application contra legem of Netherlands law.

128 In any event, in the case of either of the subsidiary findings on selectivity in respect of the measures at issue, according to the applicants the Commission has not shown sufficiently in fact and in law that the situations were comparable and that a derogation exists.

129 First of all, it should be recalled that the merits of the arguments put forward by the applicants must be assessed in the light of the case-law cited in paragraphs 99 and 100 above. In the present case, they maintain that the Commission could not make the principal assumption that the measures at issue were selective. That is the case, in their view, in so far as the measures at issue are, in essence, part of the Netherlands tax administration’s general practice in relation to transfer pricing. In other words, the measures at issue cannot be treated as individual measures.

130 In that regard, in the case of individual aid, the identification of the economic advantage is, in principle, sufficient to support the presumption that it is selective. The presumption of selectivity operates independently of the question whether there are operators on the relevant market or markets which are in a comparable factual and legal situation (judgment of 13 December 2017, Greece v Commission, T‑314/15, not published, EU:T:2017:903, paragraph 79).

131 By contrast, when examining an aid scheme, it is necessary to identify whether the measure in question, notwithstanding the finding that it confers an advantage of general application, does so to the exclusive benefit of certain undertakings or certain sectors of activity (judgment of 4 June 2015, Commission v MOL, C‑15/14 P, EU:C:2015:362, paragraph 60).

132 First, the measures at issue are tax rulings concluded between the Netherlands tax administration and the applicants; those rulings are intended only to cover the applicants’ tax situation, not that of other companies, as is clear from paragraphs 38 and 138 of the contested decision. Second, the Commission provisionally found that an economic advantage is conferred on the applicants, the advantage resulting, in essence, from a lowering of its tax base. On the assumption that the applicants intend, in essence, to challenge the finding of an advantage by complaining that the Commission incorrectly assessed the nature of an APA in Netherlands law, it must be stated that the arguments advanced in that regard in the application must be rejected as being unfounded, for the reasons set out in paragraphs 110 to 120 above.

133 Consequently, the conditions giving rise to a presumption as to the selectivity of the measures at issue were satisfied in the present case.

134 The absence of specific reasons, in the contested decision, in relation to the existence or possible non-existence of an aid scheme from which the measures at issue may have been derived does not in any way affect that finding. In the contested decision, the Commission does not test the assumption that there is an aid scheme from which the measures at issue may have been derived, whether that scheme arises de jure from Article 8b(1) of the CIT or de facto from a set of tax rulings indicating a systematic course of action on the part of the Netherlands tax administration.

135 The Commission does, correctly, point out in the defence that the selectivity of an individual measure granted on the basis of a general scheme must be established following a three-step test. According to the Commission, ‘where the Commission seeks to establish that the grant of a tax benefit to an individual taxpayer under a tax scheme is selective, it cannot circumvent the three-step selectivity analysis for schemes by relying on the presumption of selectivity for individual aid measures’.

136 Nevertheless, the position is otherwise, in the Commission’s preliminary examination and in the case of tax rulings, where the existence of a general scheme from which the individual measure identified might be derived is, at the very least, uncertain.

137 In that situation, the fact that the possible existence of an aid scheme from which the individual measure identified might be derived is not ruled out in a decision initiating the formal investigation procedure does not prevent the Commission from provisionally assuming that such a measure is selective. A Member State which might counter that assumption is still in a position to point out, during the formal investigation procedure, that the individual measure identified is derived from an aid scheme and that its selectivity must therefore be demonstrated by the Commission, in the final decision, following a three-step test.

138 Consequently, the Commission was entitled, in the contested decision, to presume, provisionally, that the measures at issue were selective.

139 In so far as, with regard to the selectivity of the measures at issue, the Commission demonstrated selectivity using three lines of reasoning in the contested decision, one primary line of reasoning and the other two subsidiary, and, moreover, the contested decision is well founded inasmuch as the Commission, correctly, provisionally advanced a presumption of selectivity, the applicants’ arguments challenging the provisional assessment of selectivity in the light both of Article 8b(1) of the CIT and of the Netherlands system of corporate income tax must be rejected as being ineffective.

140 Where some of the grounds in a decision on their own provide a sufficient legal basis for the decision, any errors in the other grounds of the decision have no effect on its operative part (judgment of 14 December 2005, General Electric v Commission, T‑210/01, EU:T:2005:456, paragraph 42).

141 Moreover, where the operative part of a Commission decision is based on several pillars of reasoning, each of which would in itself be sufficient to justify that operative part, that decision should, in principle, be annulled only if each of those pillars is vitiated by an illegality. In such a case, an error or other illegality which affects only one of the pillars of reasoning cannot be sufficient to justify annulment of the decision at issue because that error could not have had a decisive effect on the operative part adopted by the Commission (judgment of 14 December 2005, General Electric v Commission, T‑210/01, EU:T:2005:456, paragraph 43).

142 Consequently, the second part of the second plea in law must be rejected as being in part unfounded and in part ineffective.

Third part of the third plea, alleging that the formal investigation procedure was initiated prematurely

143 The applicants complain that the Commission opened the formal investigation procedure prematurely, at a stage where the framework of the investigation had not been sufficiently established and the difficulties encountered could have been overcome on the basis of a detailed preliminary examination.

144 The applicants observe first of all that the Commission, unusually, did not conduct any investigations in the period from 2014 to 2017, which created the assumption that the APAs issued to the applicants did not contravene State aid law. It was not until publication of an investigation by an international consortium of journalists in November 2017 and the ensuing political pressure that the Commission sent several further requests for information to the Netherlands and decided to target the applicants unfairly.

145 The Commission also based its preliminary assessment on an inadequate analysis of the information available.

146 This is evidenced, first, according to the applicants, by the failure to investigate the presence in this case of a potential aid scheme. The Commission should have extended its preliminary examination to include the situation of companies to whom some 98 APAs similar to those of the applicants were addressed, or the situation of some 700 companies that were using a company structure comparable to that of the applicants. Likewise, the Commission failed to take sufficient account of the 2018 review of pricing practised by one of the subsidiaries of the applicants under licence agreements during the period from 2007 to 2017, a review which clearly illustrates that the measures at issue comply with the arm’s length principle.

147 Second, the extensive information requests to the Kingdom of the Netherlands, included in the annex to the contested decision, should instead have been made during the preliminary examination. That conclusion is, according to the applicants, substantiated by the fact that, in the contested decision, the Commission reserved the possibility of contacting third parties in order to obtain certain documents, although, under Article 7 of Regulation 2015/1589, that is possible only if, in the course of the preliminary examination, the documents provided by the Member State concerned are not sufficient.

148 Last, in the applicants’ submission, the contested decision contains no indication that, when the Commission published that decision, it was in a position in which it was unable to overcome all the difficulties involved in the assessment of potential State aid and its compatibility with the internal market. The Commission’s reasoning is not supported by the evidence gathered, nor is it based on legitimate doubts, which should be clearly and substantially apparent from the contested decision.

149 In that regard, it should be recalled that Article 108 TFEU and Regulation 2015/1589 lay down a special procedure for the monitoring of State aid by the Commission.

150 The preliminary examination of the aid, established by Article 108(3) TFEU and by Articles 4 and 5 of Regulation 2015/1589, which is intended to allow the Commission to form an initial view as to whether the State measure in question is in the nature of aid, is followed by the formal investigation procedure referred to in Article 108(2) TFEU and governed by Articles 6 and 7 of Regulation 2015/1589, which is intended to enable the Commission to carry out a thoroughgoing investigation of all the issues of fact and law raised by the measure at issue and to protect the rights of potentially interested third parties (judgments of 21 July 2011, Alcoa Trasformazioni v Commission, C‑194/09 P, EU:C:2011:497, paragraph 57; of 15 March 2001, Prayon-Rupel v Commission, T‑73/98, EU:T:2001:94, paragraph 41; and of 23 October 2002, Diputación Foral de Álava and Others v Commission, T‑346/99 to T‑348/99, EU:T:2002:259, paragraph 41).

151 The Commission is required to initiate the formal investigation procedure if it experiences serious difficulties, on an initial examination, in determining whether the measure under examination constitutes aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU. Article 6 of Regulation 2015/1589 states that the decision to initiate the formal investigation procedure must ‘include a preliminary assessment of the Commission as to the aid character of the proposed measure’.

152 It follows that the classification of a measure as State aid in a decision to initiate the formal investigation procedure is merely provisional. The very aim of initiating that procedure is to enable the Commission to obtain all the views it needs in order to be able to adopt a definitive decision on the point (judgments of 15 March 2001, Prayon-Rupel v Commission, T‑73/98, EU:T:2001:94, paragraph 42, and of 23 October 2002, Diputación Foral de Álava and Others v Commission, T‑346/99 to T‑348/99, EU:T:2002:259, paragraph 43).

153 The Commission’s power to adopt a decision under the rules on State aid without initiating the formal investigation procedure is thus restricted by Article 108 TFEU to measures that raise no serious difficulties. The Commission may not decline to initiate the formal investigation procedure in reliance upon third party interests, considerations of economy of procedure or any other ground of administrative convenience. However, the Commission enjoys a certain margin of discretion in identifying and evaluating the circumstances of the case in order to determine whether or not they present serious difficulties (judgment of 15 March 2001, Prayon-Rupel v Commission, T‑73/98, EU:T:2001:94, paragraphs 44 and 45).

154 In the present case, the applicants claim that the preliminary examination of the measures at issue was inadequate and that any difficulties encountered by the Commission could have been readily resolved in the light of the available information, although they do not thereby formally argue that the preliminary evaluation of the measures at issue should have led the Commission to close the procedure by means of a decision not to raise objections, but complain, in essence, that the Commission’s examination was not extended to cover the possibility of an aid scheme.

155 First, the Commission satisfied its obligation to initiate the formal investigation procedure when there were serious difficulties, and it did so without making manifest errors of assessment, as is apparent from paragraphs 92 to 142 above.

156 Likewise, the Commission repeatedly expressed its doubts, in paragraphs 87, 89, 103, 126 or 130 of the contested decision, as to the conformity of the measures at issue with Article 107 TFEU and, in part 5 of the contested decision, as to the technical complexity of the underlying issues, which could not be properly resolved on the basis of the information provided by the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the course of the preliminary examination.

157 On that point, and contrary to the applicants’ contention, Article 7(1) of Regulation 2015/1589 cannot be interpreted as meaning that information requests to third parties during the formal investigation procedure are possible only on condition that no further request for information is made to the Member State concerned during that procedure. Article 7(1) of Regulation 2015/1589 merely indicates that other sources of information may be sought if the information provided by the Member State concerned in the course of the preliminary examination is not sufficient.

158 That is precisely the case here, in that it is apparent from part 5 of the contested decision that the information provided by the Kingdom of the Netherlands would not have enabled the Commission to proceed further with its analysis of the measures at issue, and therefore that possible requests to third-party sources of information were permitted in the present case and cannot be properly relied upon to establish that the Commission’s preliminary examination was inadequate.

159 Second, in the light of paragraphs 93 to 106 above, the framework of the preliminary investigation has been sufficiently established in fact and in law. The failure to extend the preliminary examination to include identification of a possible aid scheme from which the measures at issue may have been derived cannot be accepted for the purposes of annulment of the contested decision.

160 Irrespective of whether or not the measures at issue are derived from an aid scheme, the Commission remains in a position to focus primarily on measures to implement such a scheme, rather than on the scheme per se, and therefore no deficiency in its preliminary examination can have resulted in this case and in any event.

161 Similarly, the preliminary examination does not require the Commission to conduct a thoroughgoing examination, this being carried out, with regard to measures whose assessment raises serious difficulties, once the formal investigation procedure is initiated.

162 It is, however, apparent from the case-law that where the Member State concerned contends in the course of the preliminary examination that the measures at issue do not constitute aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, the Commission must, before initiating that procedure, undertake a sufficient examination of the question on the basis of the information notified to it at that stage, even if the outcome of that examination is not definitive (judgment of 10 May 2005, Italy v Commission, C‑400/99, EU:C:2005:275, paragraph 48).

163 In the present case, the contested decision contains, according to paragraphs 76 to 162 thereof and on the basis of the documents at the Commission’s disposal, a preliminary, yet substantive, analysis of the measures at issue, notably as regards the complex study of the advantage and selectivity of those measures. To that end, the analysis of the 2018 review, provided by the Kingdom of the Netherlands and relating to the payments made in the period from 2007 to 2017 in connection with the licensing of IP rights to NEON, was taken into account, as is evident from paragraph 123 of that decision.

164 Thus, the Commission satisfied the requirements of the preliminary examination, and therefore the third part of the third plea in law must be rejected as being unfounded.

Third part of the first plea, alleging breach of the principles of good administration and equal treatment

165 The applicants claim that the Commission breached the principles of good administration and equal treatment by choosing arbitrarily to investigate whether the measures at issue complied with State aid law and not extending its analysis to the general scheme on which the measures at issue are based and its potential beneficiaries.

166 They argue that, having failed to take account, in the present case, of the characteristics and nature of the Netherlands corporate taxation system or to conduct any analysis of other APAs, the Commission also failed to consider carefully and impartially all the relevant evidence.

167 In the applicants’ submission, in the same way as it did in Decision C(2015) 563 (final) of 3 February 2015 on the excess profit tax ruling system in Belgium – Article 185§ 2(b) CIR92, initiating the formal investigation procedure provided for by Article 108(2) TFEU, the Commission should have determined whether an aid scheme from which the measures at issue were derived existed under, in particular, Article 8b(1) of the CIT.

168 As regards, in the first place, observance of the principle of good administration, it should be noted that, according to settled case-law, the Commission is required, in the interests of good administration of the fundamental rules of the FEU Treaty relating to State aid, to conduct a diligent and impartial examination of the contested measures, so that it has at its disposal, when adopting the final decision, the most complete and reliable information possible (see judgment of 2 September 2010, Commission v Scott, C‑290/07 P, EU:C:2010:480, paragraph 90 and the case-law cited).

169 In the present case, however, the Commission did not demonstrate partiality and a lack of diligence by not extending its preliminary examination to include identification of a possible aid scheme. There is no rule under the Treaty or Regulation 2015/1589 that requires the Commission to determine as a priority whether an aid scheme exists when considering an individual measure. The object of its review could indeed, therefore, be limited to the measures at issue.

170 What is more, irrespective of the question of the non-extension of the Commission’s examination to cover the possibility of an aid scheme, it must be noted that, for the purposes of adopting the contested decision, the Commission carried out its provisional assessment of the measures at issue in a diligent and impartial manner. It is apparent, in particular, from paragraphs 1 to 7 of the contested decision that the Commission sent numerous information requests to the Kingdom of the Netherlands in order to have sufficient information at its disposal to make a provisional assessment of the existence, in the present case, of State aid. Likewise, the adoption in the present case of the contested decision, which includes a provisional, yet substantive, analysis of the existence of State aid, in particular of the grant of a selective advantage in favour of the applicants, properly enables the applicants to submit their observations in the course of the formal investigation procedure.

171 Consequently, the Commission did not breach the principle of good administration.

172 The same applies to breach of the principle of equal treatment.

173 Compliance with the principle of equal treatment or non-discrimination requires that comparable situations must not be treated differently and that different situations must not be treated in the same way unless such treatment is objectively justified (see judgment of 11 December 2014, Austria v Commission, T‑251/11, EU:T:2014:1060, paragraph 124 and the case-law cited).

174 In the present case, it must be observed that the applicants do not substantiate their argument in relation to breach of the principle of equal treatment and do not precisely identify the companies or multinational groups which they claim are in a situation comparable to their own.

175 However, on the assumption that the applicants are in a situation comparable to other undertakings, the fact that the Commission chose to review, as a priority, only the compliance of the measures at issue with State aid law, without extending its examination to include the possible existence of any aid scheme of which other undertakings might be beneficiaries, does not entail a breach of the principle of equal treatment. The Commission remains free to determine those State measures, whether individual or constituting an aid scheme, which it wishes to examine pursuant to State aid law.

176 The same conclusion must be drawn if it is assumed that the Commission was obliged, quod non, to initiate an investigation in respect of other undertakings benefiting from measures similar to those at issue in the present case. The principle of equal treatment must be reconciled with the rule that a person may not rely, in support of his or her claim, on an unlawful act committed in favour of a third party (see, to that effect, judgment of 31 May 2018, Groningen Seaports and Others v Commission, T‑160/16, not published, EU:T:2018:317, paragraphs 116 to 118).

177 In other words, the argument relating to a breach of the principle of equal treatment cannot succeed in respect of an undertaking concerned by a decision finding, whether provisionally or not, that there is State aid, unless, in the case of another undertaking benefiting from a similar measure, which is in a factually and legally comparable situation, the Commission had, correctly, found there to be no State aid.

178 Furthermore, in addition to the fact that incompatible State aid is prohibited, under Article 107 TFEU, a beneficiary of aid cannot have the right to maintain his or her advantage merely because other undertakings are also liable to benefit; that is so in order to preserve the practical effect of State aid law.

179 Consequently, the third part of the first plea in law must be rejected as being unfounded and, accordingly, the action must be dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

180 Under Article 134(1) of the Rules of Procedure, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicants have been unsuccessful, they must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the form of order sought by the Commission.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Second Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Nike European Operations Netherlands BV and Converse Netherlands BV to pay the costs.

Tomljenović | Škvařilová-Pelzl | Nõmm |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 14 July 2021.

E. Coulon |

| S. Papasavvas |

Registrar |

| President |

* Language of the case: English.