Commission, July 26, 2021, No M.10231

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

PARTIES

Demandeur :

AerCap Holdings N.V.

Défendeur :

GECAS et SES

Dear Sir or Madam,

(1) On 18 June 2021, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration (the “Transaction”) pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which AerCap Holdings N.V. ("AerCap", The Netherlands) acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of the whole of GE Capital Aviation Services ("GECAS", US), belonging to General Electric Company (“GE”, US) and, within the meaning of Articles 3(1)(b) and 3(4) of the Merger Regulation, joint control together with Safran Aircraft Engines (“Safran”, France) over Shannon Engine Support Limited ("SES", Ireland), currently jointly controlled by GE and Safran. The concentration is accomplished by way of purchase of shares and assets.3

1. THE PARTIES

(2) AerCap's primary business is the leasing of commercial aircraft, which it carries out on a worldwide basis. AerCap has its global headquarters in Dublin, Ireland.

(3) GECAS is active in the commercial aircraft leasing and financial industry, offering a broad array of leasing and financing products and services for commercial aircraft, turboprops, aircraft engines, helicopters and materials. GECAS is headquartered in the United States and is currently part of the group ultimately owned by GE.

(4) SES is a subsidiary of CFM International (“CFMI”), a jointly controlled 50/50 full function4 joint venture between GE and Safran. SES is active in aircraft engine leasing.

(5) AerCap, GECAS and SES are hereinafter referred to as the “Parties”.

2. THE OPERATION AND CONCENTRATION

(6) On 9 March 2021, AerCap entered into a Transaction Agreement with GE pursuant to which AerCap will acquire sole control over the GECAS business and joint control over SES, with Safran being the other jointly controlling parent company. Hereinafter, AerCap as it will emerge post-Transaction is referred to as the “Merged Entity”.

(7) As part of the Transaction, GE will also acquire approximately 46% of the Merged Entity’s shareholding and will be entitled to nominate two directors of its Board of Directors (the “Board”)5 and to appoint one of those GE directors to the Nomination and Compensation Committee of the Board.6 However, this stake will not grant GE joint control over AerCap.

(8) This is because under the Shareholders’ Agreement (“SHA”) GE has agreed to a restriction of its ability to vote, such that GE may only vote shares constituting up to 24.9% of the total AerCap shares eligible to vote.7 Taking into account the attendance and voting levels at AerCap's annual general meetings over the last four years, GE would not be highly likely to achieve a majority at the shareholders’ annual general meetings of AerCap.8.

(9) Moreover, under the SHA, GE’s right to nominate two out of the eleven directors of AerCap’s Board (at most) and to have one of those GE directors appointed to the Nomination and Compensation Committee of the Board, will not enable GE to veto any strategic decisions of the Board (e.g. approval of budget, business plan or appointment of senior management).9

(10) As part of the Transaction, AerCap will also acquire joint control over SES.10 SES is currently a subsidiary of CFMI, a jointly controlled 50/50 joint venture between GE and Safran. CFMI is active in the design, manufacture, marketing, maintenance, repair and overhaul (“MRO”) support of aircraft engines. This acquisition is envisaged under two possible scenarios.11 Irrespective of the structure ultimately adopted, AerCap will acquire joint control over SES as a result of the Transaction.

(11) According to the Parties, the rationale for the Transaction is to create a diversified aviation lessor with positions across aircraft, engine and helicopter leasing, and related activities, which will be a strategic partner to customers globally. AerCap expects that the combination with GECAS’ complementary business and the resulting increase in the diversity of the aircraft portfolio will enable the Merged Entity to provide high-quality services benefiting existing and new customers.

(12) In light of the above, the Transaction constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation and of Articles 3(1)(b) and 3(4) of the Merger Regulation respectively, as far as the acquisition of sole control over GECAS and of joint control over SES are concerned.

3. UNION DIMENSION

(13) The undertakings concerned have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (AerCap: EUR 3 789 million, GECAS: EUR 3 460 million, SES: EUR […]).12 Each of at least two of the undertaking concerned has an aggregate Union-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (AerCap: […] million, GECAS: […] million). Not all of the undertaking concerned achieve each more than two-thirds of their aggregate Union-wide turnover within one and the same Member State.

(14) The notified operation therefore has a Union dimension pursuant to Art. 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. ASSESSMENT

4.1. No horizontal concerns with respect to aircraft leasing

4.1.1. Market definition

4.1.1.1. Relevant product market

(15) Aircraft are expensive assets. According to the Parties, the average list price of a narrow body aircraft (i.e. one aisle, 100-200 passengers) is USD 100-110 million while the price of a wide body aircraft (i.e. two isles, 200-400 passengers) is USD 300-320 million.13 Considering the cost involved, airlines often require financial solutions in order to source aircraft. Such solutions may be in the form of loans from creditors, funding from capital markets or different types of leasing.

(16) The Parties argue that aircraft leasing is in essence one type of financial solution for airlines to acquire aircraft and as such belongs to a market that encompasses all types of aircraft financing solutions.14

(17) In previous decisions, the Commission considered two distinct markets for aircraft leasing:15

(a) Wet leasing: by which the aircraft is leased with its crew, maintenance and insurance. These are typically short-term transactions between two airlines.16 The Parties are not active in wet leasing.

(b) Dry or operational leasing: by which only the aircraft is leased.17 Around 41% of the total worldwide number of commercial aircraft is on dry leases.18 The Parties overlap in dry leasing.19

(18) The Commission also considered a segmentation of dry leasing according to aircraft size: wide-body (200-400 seats), narrow-body (100-200 seats) and regional aircraft, which can be sub-divided further to aircraft of 30-50 seats and aircraft of 70-90 seats.20

(19) The market investigation in this case suggested that dry leasing may be further segmented according to types of lease.21 Thus, sale and lease back (“SLB”) is a lease by which an airline is selling to a lessor an aircraft it already has in its fleet or an aircraft it has on order from an aircraft manufacturer (“airframer”) and immediately leases it back from the lessor. In the second type of dry leasing, the lessor is the original owner of the aircraft (for example because it ordered it directly from an airframer). This latter type of leasing is referred to as “direct”, “speculative” or “placement” leasing.22

(20) According to market participants, SLB and direct leasing are different services from the demand side. 23 SLB’s serve financial needs of airlines; airlines would rely on SLB leasing when they own the aircraft but are looking for more liquidity or to cut capital expenses. Direct leasing serve operational needs: airlines would rely on direct leasing when they need more aircraft but cannot purchase them themselves, for example because the time to order them directly from airfarmes is too long24 or when they cannot order them directly from the airframers. 25

(21) From the supply side, direct leasing represents higher risk for lessors compared to SLBs because, unlike with SLBs, with direct leasing the lessor bears the risk of finding a lessee for the aircraft.26 In addition, ordering aircraft directly from airframers is highly complicated and requires very specific expertise that only a minority of lessors have.27 While more than 150 lessors are active in SLB, only about 15-20 are regularly active in direct dry leasing.28

(22) Rates to be paid for SLBs and direct leases are also different. While the rate of SLB is primarily based on the price of the aircraft paid by the airline offering it for SLB, the rates of direct leases are based on the balance of demand and supply for the aircraft at the time it is leased.29

(23) In accordance with the Commission practice mentioned above, a further segmentation by type of aircraft should be considered also with respect to the two types of dry leasing. Another possible distinction is between passenger and non- passenger (or cargo) aircraft that serve different demand needs.

(24) Specifically in relation to direct dry leasing, market participants explained that direct leasing of wide body aircraft represent a higher risk to lessors compared to leasing of narrow body aircraft. Wide body aircraft are three times more expensive than narrow body aircraft and demand for them is much smaller than for narrow body aircraft. Consequently, it is more difficult for lessors to find a lessee for wide body aircraft. Another significant difficulty, when the lessor seeks to replace a lessee, is re- branding. When an aircraft changes from one airline to another, it has to be re-fitted in order to comply with the branding of the new airline. Wide body aircraft are more expensive to re-brand not only because they are bigger but also because airlines invest significantly more in branding their premium classes that are usually served by wide body aircraft, an investment that is not typically made in narrow body aircraft. Consequently, out of about 15-20 lessors regularly active in direct dry leasing, only about five to ten are considered to be regularly active in the dry leasing of wide body aircraft.30

(25) On the basis of the above, the Commission concludes that there is a separate market for dry leasing. It can be left open whether the market for dry leasing should be further segmented between type of leasing or type of aircraft, as the Transaction does not raise competition concerns under any plausible market definition.

4.1.1.2. Relevant geographic market

(26) In previous decisions, the Commission considered the geographic scope of the market for aircraft dry leasing to be worldwide.31 The Parties agree with the Commission’s approach.32 The market participants also confirmed this approach in the market investigation in this case.33

4. I. 2. Competitive ossessmeiit

4.1.2.1. Market shares

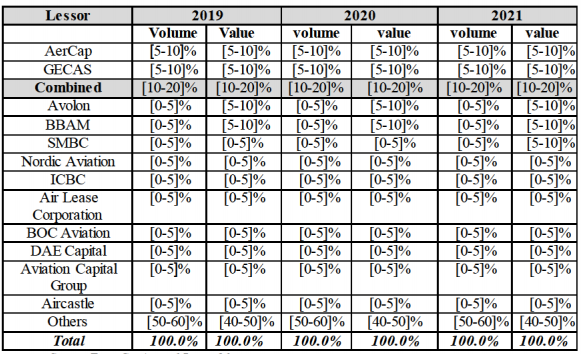

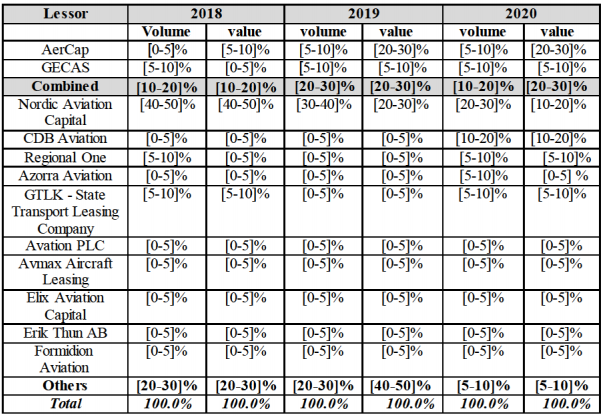

(27) The Parties’ activities overlap in dry leasing. As can be seen in the table below, the Transaction would combine the two largest lessors in the dry leasing sector. Nevertheless, as can be seen in Table 1 below, if an overall market for dry aircraft leasing (all aircraft types combined) is considered, the Parties’ combined market share would remain modest not giving rise to an affected market. As explained further below, the Transaction does not give rise to competition concerns on narrower market definitions either.

Table 1 —Parties’ estimates of lessors’ shares of worldwide fleet34 on dry leasing (in volume and value)

Source: Form Co, Annex 6.7 page 26

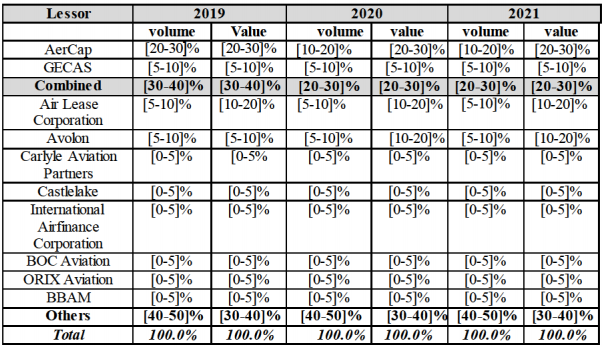

(28) The Transaction does not give rise to affected markets when considering market shares for dry leasing (SLB and direct leasing combined) by aircraft type. When considering separately SLB and direct leasing by aircraft type, the Transaction will not give rise to affected markets, except for direct dry leasing for wide body passenger aircraft.35 However, as can be seen in Table 2, the Parties’ combined market shares are below 40% and have been decreasing each year. The increment represented by the Transaction that is, the share of GECAS in the market, is modest (less than 10%) and a good number of significant lessors will remain in the market post-Transaction

Table 2 —Parties’ estimates of lessors’ shares of worldwide wide body passenger fleet36 on direct dry leasing (in volume and value)

Source: Form Co, Annex 6.7 page 48

(29) The Parties also provided sires on the basis of a narrower delineation on which the Parties overlap, taking into consideration only those direct leases made by the lessors who originally ordered the aircraft with the anframers.37 On the basis of this delineation, three affected market were identified, for each type of aircraft, ie. wide body, narrow body and large regional passenger aircraft.

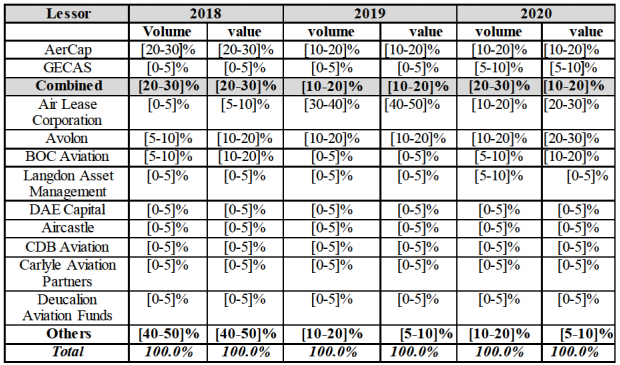

(30) With respect to wide body passenger aircraft on direct dry leasing from the original lessors, as can be seen in Table 3, the Parties’ combined market shares are modest, close and even below 25%, the level below which it may be presumed that concentrations are not liable to impede effective competition38 The increment represented by the Transaction that is, the share of GECAS in the market, is modest (less than 10%) and a good number of significant lessors will remain in the market post-Transaction

Table 3 — Parties’ estimates of original lessors’ shares of annual39 worldwide direct dry leasing of wide body passenger aircraft (in volume and value)

Source: Response to RFI 1, page 9

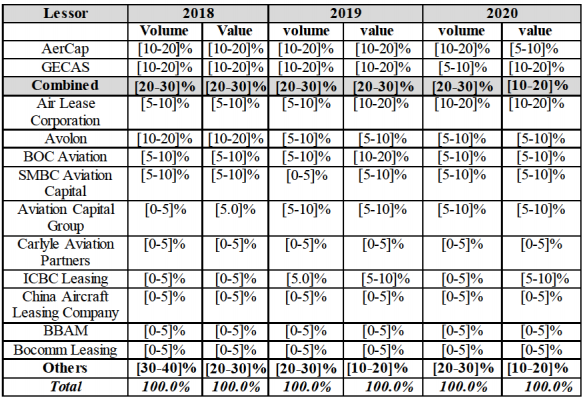

(31) With respect to narrow body passenger aircraft on direct dry leasing from the original lessors, as can be seen in Table 4 below, the Parties’ combined market shares are modest, close to 25%, the level below which concentrations can be presumed not to be Able to liable effective competition. In addition, a good number of significant lessors will remain in the market post-Transaction.

Table 4 — Parties’ estimates of original lessors’ shares of annual worldwide direct dry leasing of narrow body passenger aircraft (in volume and value)

Source: Response to RF'I 1, page 10

(32) With respect to large regional aircraft on direct dry leasing from the original lessors, as can be seen in Table 5, the Parties’ combined market shares are modest, close and even below 25%, the level below which concentrations can be presumed not to be liable to impede effective competition.40 The increment represented by the Transation that is, the share of GECAS in the market, is modest (less tin 10%). A larger lessor than the Parties in this segment, Nordic Aviation Capital, as well as a good number of other significant lessors will remain in the market post-Transaction.

Table 5 — Parties’ estimates of original lessors’ shares of annual worldwide direct dry leasing of large regional passenger aircraft (in volume and value)

Source: Response to ROI 1, page 13

(33) The current airframers’ order book of new aircraft by lessors provides insight to the position of lessors’ in the coming years in the segment of direct dry leasing from the original lessors. According to the Parties’ estimates, they represent only [10-20] % of the overall current orders (all aircraft types included) of lessors. The Parties’ share is highest with respect to wide body aircraft ([20-30] %) but in that segment it is in fact second to the significantly higher share (attest [30-40]%) of [lessor].41

4.1.2.2. Th market investigation

(34) Aircraft dry leasing markets for all types of aircraft appear competitive. Demand for aircraft dry leasing overall has been growing steadily in recent years42 and the expectations is that the market will continue growing also after the COVID-19 crisis.43 There is a large number (more than 150)44 of lessors and a significant number of recent entries.45 Chinese lessors, in particular some who are part of major financial institutions,46 were growing fast in recent years and gaining market shares.47 Overall, the leasing industry has become more fragmented in past years.48 In fact, since 201349 the number of aircraft in each of the Parties’ fleets has been constantly decreasing (AerCap -22%, GECAS -39%) while the overall aircraft leasing industry was growing.50 Consequently, as also shown by Tables 1 and 2 above, the Parties’ shares have been decreasing in the overall market for dry leasing and in the wide body segment.

(35) Although the Transaction will create the largest lessor worldwide, the market investigation did not provide a clear indication that the Merged Entity would obtain an additional significant advantage over its competitors. While some of the market participants considered that the size of the Merged Entity would give it an advantage over its competitors, others opined that once a certain fleet size is achieved (about 300 aircraft) there is little advantage to additional size and there may even be disadvantages.51 Market participants therefore expect that post-Transaction the Merged Entity would rationalise and decrease its combined fleet as AerCap did after the purchase of ILFC.52

(36) Market participants also point out that there are several strong lessors with sufficiently large fleets that will remain in the market post-Transaction; in addition to the Parties there are at least nine lessors with fleets larger than 300 aircraft across all aircraft types, including wide body aircraft.53 Market participants also did not identify the Parties as closer competitors to each other than other lessors. They noted that at least the other major lessors as close competitors (even if significantly smaller by size).54 Some market participants explained that, in their view, all lessors active in a specific aircraft leasing segment compete with each other55 and would be considered by airlines.56 Indeed, airlines typically work with a large number of lessors.57 Airlines prefer working with several lessors also in order to manage their exposure to them.58

(37) Furthermore, the market investigation was inconclusive as to whether the Merged Entity will obtain post-Transaction a stronger position vis-à-vis the airframers that may give it an advantage compared to other lessors. While some market participants considered that this may be the case, others opined that the Merged Entity would not acquire such advantage because airframers have other large customers and also prefer to manage their exposure to customers.59

(38) In addition, with respect to the market for direct leasing of wide body aircraft specifically, the smaller number of lessors for direct wide aircraft compared to the number of lessors for narrow body aircraft can be primarily explained by the significantly smaller size of the market.60 Nevertheless, in the years 2018-2020 there were seven lessors that, in addition to the Parties, were regularly (that is, every year) active in the market, offering wide body aircraft for direct lease.61 In addition, there are other large lessors that have experience in this market and may re-enter if conditions are favourable.62 Currently for example, four lessors that were not regularly active in this market in the past three years have orders with airframers for wide body aircraft.63 In addition, market participants explained that direct leasing is less important with respect to wide body aircraft. First, wide body aircraft are typically operated by the larger airlines that are able to order directly from the airframers. Second, airframers have more capacity to take orders for wide body aircraft (because demand is lower) and the lag time for delivery is shorter (18-24 months) than for narrow body. Consequently, airlines can order more easily wide body aircraft directly from the airframers and are less dependent on lessors.64

(39) In view of these considerations, the large majority of market participants responding to the market investigation were of the view that the Transaction does not give rise to competition concerns.65

(40) The Commission therefore considers that the Transaction is unlikely to raise serious competition concerns with respect to dry aircraft leasing and all its plausible segments.

4.2. No concerns regarding conglomerate effects: aircraft leasing and engine leasing

(41) Through the Transaction, AerCap will purchase the aircraft engine leasing business of GE, that is, the activities of GECAS and SES in this sector. Engine leasing provides airlines with spare engines. In order to ensure undisrupted operation of their aircraft fleet, airlines have a certain number of spare engines available to replace engines that require MRO services. Engines typically require a first overhaul after approximately 7 to 10 years and, thereafter, every six years on average.66 Airlines may purchase spare engines or lease them from engine lessors. Spare engines represent about 10% of aircraft engines worldwide67 and less than half of spare engines are leased.68

(42) According to the estimates of the Parties, GE’s engine leasing business represents about [20-30]% of leased engines worldwide.69 It has an intra-group focus; the majority of the engines owned by GECAS and all engines owned by SES are GE and CFMI manufactured engines. GECAS and SES also lease back the majority of their engines to GE and CFMI for their product support services.70

(43) Other engine manufacturers also have engine leasing arms, for example Rolls Royce and Pratt & Whitney, which, according to the estimates of the Parties, represent [10- 20]% and [10-20]% of leased engines respectively. The Parties estimate that other large engine lessors are Engine Lease Finance ([10-20]%), Willis Lease ([10- 20]%) and Fortress ([5-10]%).71 There is a large number of additional dedicated engine lessors, aircraft/engine mixed lessors and airline/MRO lessors.72

(44) The Parties explained that AerCap does not operate any dedicated aircraft engine leasing business. It has occasionally leased out a negligible number of engines that it has taken off its old aircraft.73 Currently, AerCap has only [0-5] engines on lease in a market estimated by the Parties at around 3 000 engines.74 Consequently, the Transaction does not give rise to horizontal competition concerns in aircraft engine leasing.

(45) Aircraft lessors are typically not (although occasionally could be) customers of engine leasing services.75 The customers of engine leasing services are mostly airlines and providers of aircraft engine maintenance services.76 In view of this, there is also no vertical foreclosure concern. However, a hypothetical concern could be that the Merged Entity, could bundle or tie engine leasing services to aircraft leasing services thus excluding other engine lessors.77 The Parties confirmed that in the past GECAS did not bundle or tie aircraft and engine leasing and the Merged Entity will not be able to do so post-Transaction. The Parties explain that airlines do not lease engines when leasing an aircraft. First, because as explained above, the aircraft would require engine maintenance only after at least six years. Second, airlines typically have a pool of spare engines (owned or leased) that serves their fleet and do not link leases for specific engines with leases for specific aircraft.78

(46) The market investigation did not indicate that the Transaction is likely to give rise to serious concerns of conglomerate effects. While a small number of respondents did mention that the Transaction could strengthen the position of the Merged Entity in engine leasing, others opined that the Transaction would not affect competition in that respect. Overall, the large majority of respondents did not raise possible concerns with respect to engine leasing.79

4.3. No concerns regarding GE’s minority shareholding in AerCap

(47) As a result of the Transaction, there will be a link, via GE’s minority shareholding in AerCap, between GE’s activity in engine manufacturing and the Merged Entity’s activity in aircraft leasing, as well as a link between GE’s activity in engine manufacturing and the Merged Entity’s activity, through GECAS and SES, in engine leasing. However, these links will not give rise to vertical competition concerns.

(48) As illustrated in Section 2 of this Decision, GE will not acquire control over the Merged Entity as a result of the Transaction, in spite of it holding a significant minority shareholding in the Merged Entity post-Transaction. GE’s rationale in the Transaction appears to be linked to the possibility of monetising its participation in the Merged Entity over time. Evidence of this has been found in the Parties’ internal documents,80 where clear reference is made to the prospect for GE of obtaining incremental proceeds by fully exiting over time. Accordingly, as the sector recovers, GE plans to exit the Merged Entity’s shareholding through a public market sell down.81 Some respondents to the market investigation have shown to have the same understanding of the rationale of GE’s participation in AerCap as they have indicated that they expect GE to reduce its participation in AerCap in several years’ time.82

(49) As regards the link between GE’s activity in engine manufacturing and the Merged Entity’s activity in aircraft leasing, the Commission considers it unlikely that the Merged Entity would engage in any input or customer foreclosure strategy.

(50) As regards input foreclosure, even if GE had the ability to foreclose lessors competing with the Merged Entity by withholding supplies of aircraft engines from aircraft airframers, it would lack the incentive to pursue such a strategy, as its interest is to sell as many of its engines as possible. As the Merged Entity would not be able to absorb all the demand for GE-powered aircraft, GE would only stand to lose sales of engines if it were to pursue such a strategy. In line with this, the market investigation has provided no indication that GE’s minority shareholding in the Merged Entity might raise concerns.

(51) Some respondents pointed to the possibility that GE might favour the Merged Entity, by for instance granting greater discounts on GE engines than other lessors.83 However, the majority of the respondents who have expressed a view have raised no concern,84 with some confirming that, as a result of the Transaction, the Merged Entity will have a mixed portfolio of aircraft with different engines.85

(52) As regards customer foreclosure, by lacking control over the Merged Entity, GE would lack the ability of foreclosing competing engine manufacturers by favouring, via the Merged Entity, GE engines through orders placed with airframers. This lack of ability can also be explained by the fact that typically airframers and airlines, not lessors, drive engine purchases’ choices. Airframers decide which engine to certify on an aircraft platform based on their preferences and what they anticipate airlines’ demand for new aircraft will be. If airframers certify more than one engine, then airlines choose which engine they want on their aircraft.86 This was confirmed by the market investigation.87

(53) Moreover, even if it had the ability to favour GE’s engines by placing orders for GE- powered aircraft with airframers, the Merged Entity would lack the incentive to do so. Lessors order aircraft that they expect they will be able to lease to airlines. Their interest is to satisfy airlines’ demand for the combinations of aircraft and engines that airlines desire. The Merged Entity’s interest will therefore be to have a mixed portfolio of aircraft powered by different engines so as to be able to address that demand. Moreover, the Merged Entity’s shareholders other than GE would have no interest in favouring orders for GE-powered aircraft and therefore would not agree to such a strategy. As indicated in the preceding paragraph, the market investigation has provided no indication that GE’s minority shareholding in the Merged Entity might raise concerns. The majority of the respondents who have expressed a view did not raise any concern.88 An industry association has also indicated that it does not expect the Merged Entity to favour GE’s engines.89

(54) With respect to the possible link between GE’s activity in engine manufacturing and the Merged Entity’s activity in engine leasing, the Commission considers an input foreclosure strategy whereby GE would favour the Merged Entity to the detriment of competing engine lessors highly unlikely. First, the Transaction does not bring about any significant change in the market structure. The link between GECAS and GE was pre-existing, and, as a result of the Transaction will be severed as GE will no longer exert control over GECAS, via AerCap. Moreover, as explained above, AerCap has a very limited activity in the engine leasing business. Consequently, the increment brought about by the Transaction will be negligible ([0-5%]). Second, even if GE could in theory decide to exclusively or largely supply the Merged Entity, GE will have no interest and therefore incentive to foreclose engine lessors other than the Merged Entity. The market investigation has shown no signs that pre- Transaction GE engaged in such a foreclosure strategy, nor that the Transaction may raise concerns of this type.

(55) A customer foreclosure strategy is similarly unlikely. First, even if the Merged had the ability to foreclose GE’s competing engine manufacturers by purchasing exclusively or largely GE engines, it would lack any incentive to do so. The Merged Entity’s shareholders other than GE would not agree on such a strategy. It also appears from the market investigation that there are many companies active in the engine leasing market.90 GE’s competitors in the upstream market would therefore have alternative customers in the downstream market to whom to sell their engines. The market investigation has provided no indication that market participants have concerns regarding a possible customer foreclosure strategy.

5. CONCLUSION

(56) For the above reasons, the European Commission has decided not to oppose the notified operation and to declare it compatible with the internal market and with the EEA Agreement. This decision is adopted in application of Article 6(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation and Article 57 of the EEA Agreement.

For the Commission (Signed)

Margrethe VESTAGER

Executive Vice-President

NOTES :

1 OJ L 24, 29.1.2004, p. 1 (the “Merger Regulation”). With effect from 1 December 2009, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) has introduced certain changes, such as the replacement of “Community” by “Union” and “common market” by ‘internal market’. The terminology of the TFEU will be used throughout this decision.

2 OJ L 1, 3.1.1994, p. 3 (the “EEA Agreement”).

3 Publication in the Official Journal of the European Union No C 251, 28.6.2021, p. 28.

4 SES has been operating continuously since its establishment in 1988 with its own resources and assets, staff, and dedicated management. It has its own presence on the market and conducts its relationship with its parents’ companies at arm’s length.

5 So long as GE collectively owns at least 10% of AerCap’s outstanding ordinary shares.

6 So long as GE collectively owns any of AerCap’s outstanding ordinary shares.

7 GE is only permitted to vote the entire stake in minority shareholder protection matters.

8 Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice, recital 59.

9 Each director has the right to cast one vote, all resolutions shall be passed by an absolute majority of the votes cast and the Board can only pass resolutions when a quorum of four directors are present. It follows that the presence of GE directors in the AerCap Board would not be required to reach a quorum, and the two directors designated by GE could not pass any resolutions by themselves.

10 The acquisitions of GECAS and of SES are linked by conditionality. As a result, the two transactions are considered as a single concentration […].

11 Under one scenario, […]. Under the other scenario, […].

12 Turnover calculated in accordance with Article 5 of the Merger Regulation.

13 Form CO, paragraph 6.3.

14 Form CO, paragraph 6.44 et seq.

15 Case M.9287 - CONNECT AIRWAYS / FLYBE, paragraph 214 et seq: COMP M.9062 FORTRESS INVESTMENT GROUP /AIR INVESTM ENTVA LENCIA / JV, paragraphs 44-45.

16 Form CO, paragraph 6.8.

17 This contrasts with other industries where “operational leasing” means a type of lease where the lessor provides other services such as maintenance and insurance. In aircraft leasing it is in wet leasing that the lessor provides such additional services. Form CO, paragraph 6.59 et seq.

18 Form CO, paragraph 6.16.

19 The Parties are also active to a limited extent in “finance leasing” (less than 5% of each Parties’ turnover and assets, Form CO, footnote 28 and paragraphs 6.68, 6.138 et seq). Finance leasing is a type of dry leasing at the end of which the lessee purchases the aircraft. Otherwise, it is like dry leasing (Form CO, paragraph 6.59 et seq.). Industry reports do not distinguish between finance leasing and other dry leasing (Form CO, footnote 3 and 50). In the past, the Commission did not consider a distinction between finance and dry leasing and no indication was provided during the e market investigation that finance leasing should be further distinguished from dry leasing.

20 Case M.9287 CONNECT AIRWAYS / FLYBE, paragraphs 214 et seq: COMP M.9062 FORTRESS INVESTMENT GROUP /AIR INVESTM ENTVA LENCIA / JV, paragraphs 44-45.

21 Form CO, paragraph 6.7 et seq; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 2 [ID328]; minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraphs 2-3 [ID358]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 5 [ID360].

22 Unlike with SLB leasing in which the lessee is known upfront, in direct leasing the lessor buys the aircraft “speculatively” hoping to find “a placement” (i.e., a lessee) for the aircraft.

23 Minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 7 [ID54]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 9 [ID154]; questionnaire to customers, responses to question 4.

24 The process of ordering directly with an airframer takes several years before the aircraft are delivered. The process is shorter when leasing from a lessor that already placed the order or has aircraft available.

25 When ordering directly from airframers, airlines need to make large payments before the aircraft is delivered. Another difficulty is that airframers prefer working with large credible customers and may not accept orders from smaller or less reputable airlines; Minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 7 [ID54]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 9 [ID154]; questionnaire to customers, responses to question 4.

26 Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 2 [ID328]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 5 [ID360]; minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 2 [ID358].

27 Questionnaire to competitors, responses to question 5; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraphs 6 and 14 [ID154]; minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 2 [ID358].

28 Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 6 [ID328]; Minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 9 [ID54]; questionnaire to customers, responses to question 6.

29 Minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 8 [ID54]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 4 [ID328].

30 Minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 2 [ID358]; minutes of a call with an industry association, paragraph 7 [ID360]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 5, [ID360]; minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 5 [ID304]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 6 [ID328]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 11 [ID154]; questionnaire to customers, responses to question 6.

31 Case M.9287 - CONNECT AIRWAYS / FLYBE, paragraph 221: COMP M.9062 FORTRESS INVESTMENT GROUP /AIR INVESTM ENTVA LENCIA / JV, paragraph2 46-48.

32 Form CO, paragraph 6.87 et seq.

33 Questionnaire to competitors, responses to question 7; Questionnaire to customers, responses to questions 7 and 8; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 4 [ID154]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 8 [ID360]; minutes of a call with an industry association, paragraph 8 [ID360]; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 10 [ID54].

34 The table refers to the shares of the current worldwide fleet fumed by lessors.

35 The Parties do not overlap in non-passenger (or carp) aircraft as AerCap has only legible activities in in this segment. leas in out one aircraft in 2019. Form CO, footnote 1.1 and paragraph 6.282 et seq: response to RFI-1. Excluding non-pas sender aircraft firoin the analysis increases the Parties’ combined shares.

36 The table refers to the shares of the current worldwide fleet owned by lessors

37 Lessors countians sell aircraft to other lessors (outs of call coli a les soar, apograph 3 [IDI54]). Those aircraft are not leased out antrorse by the ordering less ores, the new lessors did not carry the risk of the speculate e order and ray not nieces sanity have them elves the expertise to order aucioft directly front the airfmux•is. Arguably. such leases cannot be properly considered as direct leases.

38 Commission guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers, recital 18.

39 The Parties were not able to identify the original direct lessor for the worldwide fleet and provided in Tables 3-5 market shares based on the transactions in each of the years 2018-2020.

40 Commission guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers, recital 18.

41 Form CO, Annex 6.10A.

42 Minutes of call with an airframer, paragraph 8 [ID358]: minutes of call with a lessor. paragraph 10

43 Form CO, 6.36-6.41; minutes of call with an airframer, paragraph 8 [ID358]; minutes of call with a lessor, paragraph 10 [ID332]; questionnaire to competitors, responses to question 14.

44 Form CO, paragraph 6.73; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 5 [ID54]; minutes of a call with an airframer. paragraph 3 [ID358].

45 Form CO, paragraphs 7.11 et seq and 8.43 et seq; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 14 [ID154]; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 11 [ID54]; Minutes of call with an airframer, paragraph 12 [ID358].

46 Among the top-12 lessors worldwide, four belong to the following Chinese banks: Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Bank of China, Bank of communications and China Development Bank. Form CO, page 162 (annex 7).

47 Parties’ internal document, document 5.4.(iii) – 22 – 3Q'20 Operating Review, slide 5; Minutes of call with an airframer, paragraph 8 [ID358]; Minutes of call with a lessor, paragraph 10 [ID332].

48 From CO, page 174 (annex 7.10), paragraph 7.15 et seq; Minutes of call with a lessor, paragraph 13 [ID332]; Minutes of call with an airframer, paragraph 4 [ID304]; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 11 [ID54].

49 In 2013, AerCap purchased from AIG its leasing aircraft company ILFC that was at the time, together with GECAS, one of the two largest aircraft lessors worldwide.

50 From CO, page 174 (annex 7.10), paragraph 7.15 et seq.

51 OEMs and airlines prefer spreading their exposure to lessors and may therefore prefer working less with AerCap post-Transaction. In addition, very large fleets, especially those created as a result of merging two previously independent portfolios, may represent imbalances in exposure to risk (e.g. too many aircraft of the same type or leased to the same customers). Moreover, keeping a large fleet on the books pla ces high burden of depreciation. Minutes of call with an airframer, paragraph 11 [ID358]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraphs 12-13 [ID154]; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 13 [ID54]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 14 [ID332]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 19 [ID332]; minutes of call with an airframer, paragraph 7 [ID304]; minutes of call with engine manufacturer, paragraph 11 [ID315]; questionnaire to customers, response to question 13, 13.2 and 14; questionnaire to competitors, responses to questions 12, 12.2, 15.1 and 15.2.

52 Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 18-19 [ID332]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 9 [ID328]; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 13 [ID 54].

53 […] Form CO, page 174 (annex 7.10). See also minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 13 [ID54].

54 In addition to the lessors already noted in footnote 51, market participants also mentioned […]. Questionnaire to customers, responses to questions 10 and 11; questionnaire to competitors, responses to questions 9 and 10.

55 For example, all lessors active in direct leasing of wide body compete against each other.

56 Questionnaire to customers, responses to questions 10 and 11; questionnaire to competitors, responses to questions 9 and 10; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 5 [ID54].

57 The top-20 leasing European airlines (by number of leased aircraft) are working with 5 to 31 lessor (17 lessors on average); Form CO, page 173 (annex 7.6.2). See also questionnaire to customers, responses to question 9.

58 Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 13 [ID154]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 13 [ID328].

59 An airframer explained that because lessors place orders regularly with all airframers, airframers compete less fiercely on lessors’ orders than on airlines’ orders; call with an airframer, paragraphs 11-12 [ID304], questionnaire to customers, question 14.3; questionnaire to competitors, responses to question 15.3.

60 There are about 1 283 wide body aircraft worldwide on direct lease compared to more than 5 732 narrow body aircraft; Form CO, annex 6.7, pages 43 and 44.

61 […]; Form CO, annex 6.8A, page 8.

62 Minutes of call with an airframer, paragraph 13 [ID358].

63 […] Form CO, annex 6.10 A, page 4. Airframers, […] may occasionally assist customers in various ways to finance their orders, including through direct dry leasing; minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 9 [ID358]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 2 [ID304].

64 Minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraphs 13-14 [ID358].

65 Minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraphs 11 and 13 [ID358]; minutes of a call with an industry association, paragraphs 2 and 9 [ID360]; Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 12 [ID332]; minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 7 [ID304]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 13 [ID328]; Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 17 [ID154]; minutes of a call with an airline , paragraph 15 [ID54]; questionnaire to customers, responses to question 17; questionnaire to competitors, responses to questions 17-18.

66 Form CO, paragraph 6.243.

67 Form CO, paragraph 6.244; minutes of call with engine manufacturer, paragraph 9 (ID315).

68 Parties’ internal document, “5.4.(iii) - 28 - 2Q'19 Operating Review Culp overview_Redacted”, page 54. The other engines are owned by the airlines.

69 According to the estimates of the Parties, in 2020 GECAS owned [10-20]% of leased engines worldwide and SES [10-20]%. GECAS also administered for other owners additional [5-10]% of leased engines. Form CO, paragraph 6.271 (table 6.5).

70 Form CO, paragraph 6.250 et seq; Parties’ internal document “5.4.(iii) - 23 - Operating Review” page 44.

71 Form CO, paragraph 6.271 (table 6.5).

72 Parties’ internal document, “5.4.(iii) - 23 - Operating Review”, page 9. Airline/MRO lessors are subsidiaries of airlines that provide in-house and external MRO services; see minutes of call with an engine manufacturer, paragraph 6 [ID315].

73 Form CO, paragraphs 6.239.

74 Form CO, paragraphs 6.256-6.257 and 6.271 (table 6.5).

75 Form CO, paragraph 6.272; call with a lessor, paragraph 12 (ID328).

76 Form CO, paragraphs 6.251, 6.254; call with industry association, paragraph 10 (ID360).

77 The Commission Guidelines on the assessment of non-horizontal mergers, recitals 96-97.

78 Form CO, paragraphs 6.276 et seq and page 146, paragraph 3.5 (annex 6.13); see also minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 14 [ID14].

79 Questionnaire to customers, question 18; questionnaire to competitors, question 19; minutes of a call with an engine manufacturer, paragraph 11 [ID315]; minutes of a call with minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 14 [ID14]; minutes of a call with an industry association, paragraph 10 [ID360]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 12 [ID328].

80 Document 5.4.(i) - 01 - Jameson Approval, slide 31; document 5.4.(ii) - 06 - Executive Session, slide 7; document 5.4.(i) - 05 - Edited Transcript General Electric Co Outlook Conference Call, page 4.

81 Document 5.4.(ii) - 06 - Executive Session, slide 7.

82 Minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 14 [ID54]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 10 [D328]. Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 10 [D328]. See also minutes of a call with an airline, paragraph 14 [ID54].

83 Questionnaire to customers, responses to question 15.

84 Questionnaire to competitors, responses to question 16; questionnaire to customers, responses to question 15. Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 15 [ID154]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 20 [ID332]; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraphs 13-15 [ID54].

85 Minutes of a call with an engine manufacturer, paragraph 11 [ID315]; questionnaire to competitors, response to question 16.

86 Form CO, paragraphs 2.4 and 6.167.

87 Minutes of a call with an engine manufacturer, paragraph 3 [ID315]. A respondent has explained that airlines want and do choose engines as this adds one element of competition and drives down the costs of either the engine or maintenance and that lessors tend to satisfy airlines’ choice; minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 13 [ID304].

88 Questionnaire to competitors, responses to question 16; questionnaire to customers, responses to question 15. Minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 15 [ID154]; minutes of a call with a lessor, paragraph 20 [ID332]; minutes of a call with an airline, paragraphs 13-15 [ID54].

89 Minutes of a call with an airframer, paragraph 12 [ID328]; minutes of a call with an industry association, paragraph 10 [ID360].

90 Minutes of a call with an engine manufacturer, paragraph 9 [ID315].