Commission, March 18, 2021, No M.9820

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Decision

DANFOSS / EATON HYDRAULICS

COMMISSION DECISION

of 18.3.2021

declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the EEA Agreement

(Case M.9820 – DANFOSS / EATON HYDRAULICS)

(Text with EEA relevance)

(Only the English text is authentic)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area, and in particular Article 57 thereof,

Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings1, and in particular Article 8(2) thereof, 2

Having regard to the Commission's decision of 21 September 2020 to initiate proceedings in this case,

Having given the undertakings concerned the opportunity to make known their views on the objections raised by the Commission,

Having regard to the opinion of the Advisory Committee on Concentrations, Having regard to the final report of the Hearing Officer in this case,

Whereas:

1. INTRODUCTION

(1) On 17 August 2020, the Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation according to which Danfoss A/S (Denmark, hereinafter referred to as ‘Danfoss’ or the ‘Notifying Party’) would acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of Eaton Hydraulics3 (Ireland, hereinafter referred to as ‘Eaton’) by way of purchase of stocks and assets (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Transaction’). Danfoss and Eaton are referred to as the ‘Parties’.

2. THE PARTIES AND THE CONCENTRATION

(2) Danfoss is a global corporation active in the manufacturing of components and engineering technologies for refrigeration, air conditioning, heating, motor control and hydraulics for off-road machinery. Danfoss also provides solutions for renewable energy, for instance solar and wind power, as well as district energy infrastructure for cities. Danfoss is controlled by the Bitten & Mads Clausen's Foundation and maintains 71 factories and has 27 795 employees worldwide.

(3) Eaton is part of a multinational group hereinafter referred to as the ‘Eaton Group’, a global corporation active in the supply of power management solutions for electrical, hydraulics, aerospace, and vehicle applications. Eaton comprises the hydraulics business segment of Eaton (excluding its golf grips and filtration businesses). It is made of two product divisions, (i) Fluid Conveyance and (ii) Power & Motion Controls, which are active in the supply of hydraulic components and systems for industrial and mobile equipment. Eaton is a publicly held Irish corporation.

(4) On 21 January 2020, Danfoss and the Eaton Group entered into a Stock and Asset Purchase Agreement under which Danfoss has agreed to acquire Eaton from the Eaton Group. The agreed purchase price is USD 3 300 million (approximately EUR 3 000 million) in cash.

(5) Post-Transaction, Danfoss will acquire sole control over Eaton. The Transaction therefore constitutes a concentration within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation.

3. UNION DIMENSION

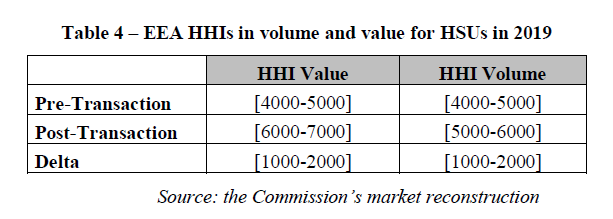

(6) The Parties have a combined aggregate world-wide turnover of more than EUR 5 000 million (In 2019, Danfoss had a world-wide turnover of EUR [...] million and Eaton EUR [...] million). Each of them has a Union-wide turnover in excess of EUR 250 million (In 2019, Danfoss had a Union-wide turnover of EUR [...] million and Eaton of EUR [...] million), while they do not achieve more than two-thirds of their aggregate Union-wide turnover within one and the same Member State.

(7) The Transaction therefore has a Union dimension pursuant to Article 1(2) of the Merger Regulation.

4. THE PROCEDURE

(8) On 17 August 2020, the Notifying Party notified the Transaction to the Commission.

(9) During its initial (Phase I) investigation, the Commission reached out to a large number of competitors and customers (that is distributors and Original Equipment Manufacturers ‘OEMs’) of the Parties requesting information through telephone calls and written requests for information pursuant to Article 11 of the Merger Regulation.

(10) In addition, the Commission sent several written requests for information to the Parties and reviewed internal documents of the Parties submitted at that stage.

(11) On 21 September 2020, based on the initial market investigation, the Commission raised serious doubts as to the compatibility of the Transaction with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement, and adopted a decision to initiate proceedings pursuant to Article 6(1)(c) of the Merger Regulation (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Article 6(1)(c) Decision’).

(12) On 22 September 2020, the Commission provided a set of non-confidential versions of certain key submissions of third parties collected during the initial (Phase I) investigation to the Notifying Party.

(13) On 1 October 2020, the Notifying Party submitted their written comments on the Article 6(1)(c) Decision (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Reply to the Article 6(1)(c) Decision’).

(14) On 6 October 2020, a virtual state-of-play meeting took place between the Commission and the Parties.

(15) On 12 October 2020, following a formal request by the Notifying Party dated 9 October 2020, the Commission extended the time-period pursuant to Article 10(3), first paragraph, of the Merger Regulation set for the adoption of a decision pursuant to Article 8 of the Merger Regulation in relation to the Transaction was extended by ten working days pursuant to Article 10(3), second paragraph, of the same regulation. The Notifying Party asked for the extension in order to allow them to submit additional advocacy papers.

(16) On 21 October 2020, the Notifying Party submitted an advocacy paper on orbital motors (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Orbital Motors Advocacy Paper’).

(17) On 10 November 2020, the Notifying Party submitted an advocacy paper on steering units (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Steering Advocacy Paper’).

(18) During its Phase I and during its in-depth (Phase II) investigation, the Commission sent several requests for information to the Parties pursuant to Article 11(2) of the Merger Regulation, including the request for internal documents of 23 September 2020 addressed to Danfoss and the request for internal documents of 23 September 2020 addressed to Eaton.

(19) In addition to collecting and analysing a substantial amount of information from the Parties (including internal documents and submissions), the Commission collected information through additional telephone calls and written requests for information addressed to the Parties’ competitors and customers pursuant to Article 11(2) of the Merger Regulation during the Phase II investigation.

(20) On 24 November 2020, the Commission informed the Parties of the preliminary results of the Phase II investigation during a virtual state-of-play meeting.

(21) On 25 November 2020, the Commission received a communication from the Notifying Party informing the Commission that it intended to discuss the possible submission of remedies.

(22) On 27 November 2020, the Notifying Party presented to the Commission in a virtual meeting an informal and preliminary commitments concept (the ‘First Commitments Concept’) with a view to rendering the concentration compatible with the internal market.

(23) On 27 November 2020, the Notifying Party requested the Commission to extend the periods provided for under Article 10(3) first subparagraph by 5 working days in order to engage in further remedy discussions. This request was made pursuant to

Article 10(3) second subparagraph, third sentence of the Merger Regulation.

(24) On 27 November 2020, following the request of the Notifying Party, the Commission decided to extend the period for taking a decision pursuant to Article 8 of the Merger Regulation by a total of 5 working days in accordance with Article 10(3) second subparagraph, third sentence of the Merger Regulation.

(25) Following this extension, the Commission informed the Parties during a state of play meeting held on 3 December 2020 that the First Commitment Concept was insufficient to remedy its concerns.

(26) On 8 December 2020, the Commission adopted a Statement of Objections (the ‘SO’), which was notified to the Notifying Party the same day. In the SO, the Commission set out the preliminary view that the Transaction would likely significantly impede effective competition in the internal market, within the meaning of Article 2 of the Merger Regulation, in relation to the supply of hydraulic steering units, electrohydraulic steering valves and orbital motors. That same day, the Notifying Party was granted access to the file.

(27) On 21 December 2020, the Notifying Party presented the Commission with a revised preliminary commitments concept (the ‘Second Commitments Concept’).

(28) On 22 December 2020, the Notifying Party submitted its reply to the SO (the ‘Reply to the SO’).

(29) In a state-of-play meeting on 11 January 2021, the Commission informed the Notifying Party that the Second Commitments Concept was insufficient to remedy its concerns.

(30) On 15 January 2021, the Notifying Party submitted a first form RM followed by a first draft Commitments on 18 January 2021, pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation, in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO (the ‘Commitments of 18 January 2021’).

(31) On 20 January 2021, a state-of-play meeting was held during which the Commission informed the Notifying Party that the Commitments of 18 January 2021 were insufficient to remedy its concerns.

(32) On 20 January 2021, a Letter of Facts setting forth evidence corroborating the objections set out in the SO was sent to the Notifying Party.

(33) On 21 January 2021, the Notifying Party requested the Commission to extend the periods provided for under Article 10(3) first subparagraph by 5 working days in order to engage in further remedy discussions. This request was made pursuant to Article 10(3) second subparagraph, third sentence of the Merger Regulation.

(34) On 28 January 2021, the Notifying Party submitted a revised form RM and revised draft Commitments, pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation, in order to address the competition concerns identified in the SO (the ‘Commitments of 28 January 2021’ and the ‘Form RM of 28 January 2021’).

(35) On 1 February 2021, the Commission launched a market test of the Commitments of 28 January 2021.

(36) On 3 February 2021, the Notifying Party submitted its comments on the Letter of Facts (‘Reply to the Letter of Facts’).

(37) On 8 February 2021, a state-of-play meeting was held in order to inform the Notifying Party of the result of the market test in relation to the Commitments of 28 January 2021.

(38) On 15 February 2021, the Notifying Party submitted revised commitments pursuant to Article 8(2) of the Merger Regulation to address the competition concerns identified in the SO (the ‘Final Commitments’).

(39) On 19 February 2021, the Commission sent a draft Article 8(2) decision to the Advisory Committee with the view of seeking the Committee’s opinion on it.

(40) The meeting of the Advisory Committee took place on 8 March 2021.

5. INTRODUCTION AND COMMON FEATURES OF THE HYDRAULIC SYSTEMS AND COMPONENTS MARKETS

(41) Hydraulic power systems (‘HPS’) are used in machines or in industrial plants for transferring mechanical energy from a certain mechanical energy source (e.g. from a diesel engine) to a certain point of use. The energy from the power source is converted into hydraulic energy through a pump, and back into mechanical energy through a hydraulic cylinder or a hydraulic motor. In this way, the mechanical energy of the diesel engine can be transported from the power source to its final point of use.

(42) HPS find their use in a number of applications, which can broadly be classified as stationary and mobile. Stationary applications include industrial manufacturing plants, oil & gas and chemical plants, while mobile applications concern vehicles that can be driven on-road or off-road. The main customers of hydraulic systems and components for mobile applications are OEMs and distributors, active in the production of (i) agricultural machinery (for example tractors and harvesters) or (ii) construction machinery (for example excavators and lifts). The Notifying Party estimates that in the EEA there are more than 800 OEMs active in agriculture machines, and more than 600 OEMs active in construction machines.4 While large OEMs such as John Deere, Caterpillar or CNH, are served by the Parties directly, smaller OEMs are typically served through distributors. Smaller OEMs are often supplied through distributors due to the more limited volume of purchases. In addition, distributors typically provide to smaller OEMs additional services (for example system integration) which larger OEMs have the capability of undertaking in-house.

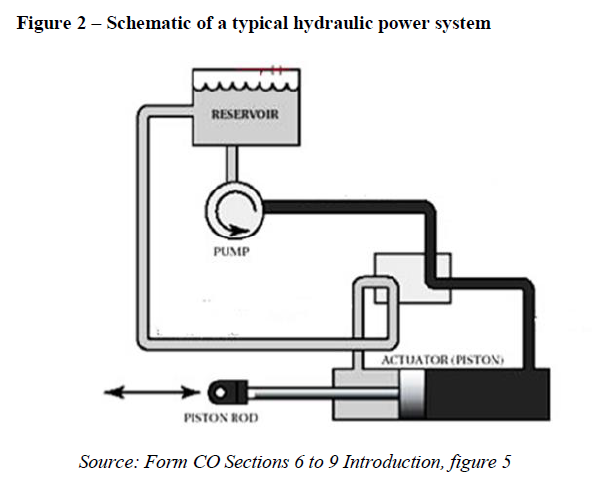

(43) An HPS typically consists of several key components: (i) a pump, (ii) a motor (or

actuator), (iii) a number of valves, (iv) an oil reservoir, and automation and control components (that is software, electronic controllers, etc.); and, in the case of a system used for steering, (vi) a steering unit. The various components are typically connected through the so-called fluid conveyance parts (mainly pipes and hoses). Figure 2 shows the schematic of a typical HPS.

(44) The pump generates a flow, which in turn creates pressure in the hydraulic system. The motor or actuator (in Figure 2 a cylinder or linear motor), converts that pressure into a mechanical force (as in Figure 2) or into a torque (in case of a rotating motion).

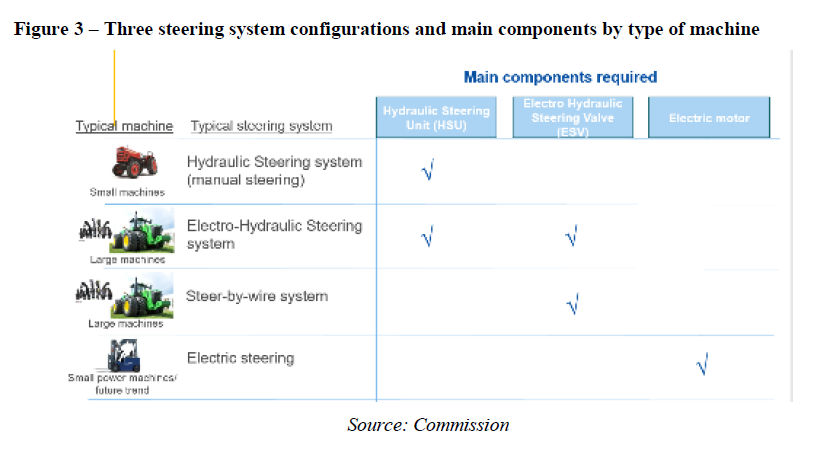

(45) An HPS with steering purposes (also referred to as “steering system”) converts the steering command (e.g., the rotary movement of the steering wheel in the driver’s hand) into the angular turn of the wheels. Over the years, different steering technologies have evolved. As further explained in Sections 6.3.3.1 and 6.3.3.2 and recital (171), hydraulic steering units (‘HSU’) use pressurised hydraulic fluid generated by pumps to move an actuator (cylinder) that moves the wheels. In contrast, in electrohydraulic steering units, which are still hydraulic but electronically controlled, an electrohydraulic steering valve (‘ESV’) converts the hydraulic oil to the cylinders in proportion to the electronic input signal. Electric steering systems convert the power from an electric source (for example electricity coming from a battery) into steering motion through an electric system, which includes an electric motor.

(46) Figure 3 below shows the three main steering system configurations, the typical types of machines in which they can be installed and the main steering components that are required.

(47) OEMs typically undertake the following steps when selecting suppliers for HPS components: The first step of the procurement process occurs when a machine is in its design phase. It typically starts with an enquiry sent by an OEM (directly or through distributors) to various potential suppliers of a given component. Each supplier designs its technical solution and submits an offer. For each HPS component, a potential supplier is selected, and, on this basis, a prototype is built and tested. Upon a successful test of the prototype, the second step is to finalise supplying conditions, including price, schedules of deliveries, etc. Overall, the selection process is based on a number of criteria such as quality, product specifications, price, delivery time (time-to-market) and delivery performance.

(48) The process of testing a certain HPS component intended to be employed in a certain machine is typically referred to as ‘homologation’ or ‘qualification’ process. In addition to the qualification of individual components, OEMs would typically qualify also its individual suppliers through, for example, financial audits. Typically, only new suppliers are to be qualified by an OEM, and suppliers that already had a commercial relationship with the OEM would typically not go through the supplier homologation process again.

6. PRODUCT MARKET DEFINITION

6.1. Legal Framework of the Commission’s assessment

(49) The Commission’s Market Definition Notice defines a relevant product market as comprising all those products and/or services which are regarded as interchangeable or substitutable by the consumer, by reason of the products’ characteristics, their prices and their intended use.5 In its assessment, the Commission takes into account various factors, including:

(a) competitive constraints

(b) demand substitution

(c) supply substitution

(d) views of customers and competitors.

6.2. Introduction to the product market definition

6.2.1. Components for HPS belong to separate product markets

6.2.1.1. The Notifying Party’s view

(50) The Notifying Party is of the view that the individual HPS components (such as pumps, valves or motors) belong to separate product markets. According to the Notifying Party, this stems from the fact that OEMs typically organise their sourcing processes at individual component level, and request quotations to suppliers for each component. In addition, the Notifying Party notes that none of the Parties offers a complete portfolio of components for HPS (e.g. neither Party produces mobile cylinders, gearboxes, filters, accumulators, clutches, drive shafts and reservoirs),6 and therefore would not be able to offer a full HPS.

6.2.1.2. The Commission’s past practice

(51) The Commission has previously found that mobile hydraulic components constitute separate markets whereby each of the components (including pumps, motors and valves) can be considered as a separate market based on its respective functioning and application.7

6.2.1.3. The Commission’s assessment

(52) On the basis of the evidence gathered during its investigation, and in line with the arguments of the Notifying Party, the Commission finds that each individual HPS component constitutes a separate product market.

(53) First, on the demand side, individual HPS components such as pumps, valves, or motors, are differentiated products which perform a specific function within the system, and which are, typically not substitutable with one another.

(54) In the first place, as explained in recitals 0-(45) above, each component serves a specific purpose and, with few exceptions, cannot be replaced by other products. The pump generates flow, which in turn creates pressure in the hydraulic system. The motor or actuator converts that pressure into mechanical force or torque. A reservoir holds hydraulic fluid. Valves are used to control the flow of hydraulic fluid in the HPS by opening, closing or partially closing the pathway of the hydraulic fluid.

(55) In the second place, the fact that each component serves a different purpose is complemented by the fact that the market investigation suggests that customers appear to have a tendency to procure such components individually. While in some instances customers may choose to procure more than one product as a system from a supplier, components from separate suppliers are often used in combination with each other and integrated in-house by the customer, as evidenced in recital (56) below.

(56) One major competitor of the Parties, who also sells integrated systems, explains that “[a]lthough systems might be engineered with customers, the mobile hydraulics market is predominantly a component business”.8 An OEM further explains: “we want to be able to make our own system and buy from different suppliers”.9 This customer’s preference is in line with procurement practices in the industry. OEMs “typically purchase individual hydraulic components”,10 and send request quotes from suppliers separately for each hydraulic component and choose the supplier who offers the most competitive price for each separate component, as further evidenced in recitals (58)-(59) below. One OEM explains: “We purchase individual components/component groups from and integrate them in our product”.11 Another describes the procurement process as follows: “Technical requirements analysis, identification of the suitable components, comparison of different suppliers and identification of the most cost-effective solution, technical assessment/validation, appointment of the supplier”.12

(57) Second, from a supply side perspective, different competitors are active in the supply of different components.

(58) Competing manufacturers of one HPS component are not necessarily the same competing manufacturers of another HPS component. Neither the Parties nor their competitors supply all components of a complete hydraulic power system (e.g. neither Danfoss nor Eaton produce mobile rated hydraulic cylinders). Some manufacturers in fact supply a limited range of HPS components. Ognibene, for instance, only manufactures steering components, with a focus on cylinders and HSUs.

(59) The fact that different competitors are active on different features of each component suggests that few if any manufacturers are capable of supplying an entire HPS system and therefore these manufacturers would not be able to supply a hypothetical market for HPS as a system, as opposed to individual components. In addition, this is also consistent with the fact that the technical differences explained in recital (45) entail differences in terms of manufacturing processes and equipment, which might prevent a manufacturer to switch its production from one type of HPS components to the other in a timely manner and without incurring additional costs.

(60) Third, market participants contacted in the context of the market investigation broadly confirm that individual HPS components belong to separate product markets.

(61) Although OEMs and distributors may have bought or considered buying bundles of several components or fully integrated systems in the past,13 a large majority14 of the OEMs15 that replied during the market investigation indicated they typically send Requests for Quotations (‘RFQs’) for individual components,16 and only a limited number of OEMs that replied during the market investigation stated that they purchase HPS components from the same manufacturer.17 A significant number of OEMs and distributors have also indicated that they do not expect to purchase bundles of components or fully integrated systems in the next three to five years.18

(62) This market feature has been substantiated by the Parties’ competitors. Although competitors contacted during the market investigation have confirmed that the sale of fully integrated systems or bundles of components can be envisaged with customers and does sometimes occur,19 a majority has indicated that they do not sell fully integrated systems in addition to individual components.20 As explained by one major competitor of the Parties: “Even if a system is designed in the context of a new project and a solution is engineered, the business is predominantly in mobile applications still done at component level.”21

(63) On the basis of the evidence gathered during its investigation, and in line with the arguments of the Notifying Party, the Commission therefore finds that given the lack of demand-side and supply-side substitutability between the different HPS components, each individual HPS component is part of separate product markets.

6.2.2. Components for HPS for mobile and for stationary applications belong to separate product markets

6.2.2.1. The Notifying Party’s view

(64) The Notifying Party distinguishes between industrial (i.e. stationary) and mobile applications.22

(65) According to the Notifying Party, mobile and industrial hydraulic power systems fall into different product markets, due to different performance requirements, cost to manufacture and, ultimately, price. Functionally, mobile hydraulic components are not optimally suited for industrial applications in terms of noise levels, duty cycle (industrial application can require 24-hour operation) and useful life. 23

6.2.2.2. The Commission’s past practice

(66) In cases Bosch/Rexroth, Volvo/Atlas, and Robert Bosch/Hägglunds Drives, 24 the Commission considered separate product markets for mobile and for stationary applications. The Commission found that HPS components for mobile and stationary applications were significantly different in design, size, pressure levels, resilience and life cycle. The expected life cycle and resilience were much higher with regard to HPS components for stationary hydraulics, since they were designed for continuous industrial operation. On the other hand, HPS components for mobile hydraulics were designed for mobile machines and as such weight-optimised and shake-proof. These differences and, consequently, their different function made them generally non-substitutable.

(67) The Commission’s assessment

(68) On the basis of the evidence gathered during its investigation, and in line with the arguments of the Notifying Party, the Commission finds that HPS components for mobile and for stationary applications belong to separate product markets.

(69) First, from a demand-side perspective, HPS components for mobile and for industrial applications are not substitutable.

(70) In the first place, technical requirements and specifications are mostly different between HPS components for industrial and for mobile applications.

(71) As explained by a former director of sales of Eaton “[m]obile applications often run for few hours a day. Industrial run 24/7. This makes for very different requirements”.25 The same document also explains that while HPS for mobile applications are typically designed for being powered by a diesel or a gasoline engine, stationary HPS would typically run on electricity, which also makes the systems, and therefore the embedded components technically different. This is also confirmed by one of the Parties’ main competitors, who explains that due to the differing technical requirements, “components are mostly realised either for the mobile or for the industrial market.”26

(72) In the second place, HPS components for mobile applications are typically customised for a specific machine which is widely sold (and therefore large numbers of those HPS components are supplied), while HPS components for industrial applications are rather based on standard components, and supplied for individual projects.

(73) The same document quoted at recital (71) continues explaining that “[i]n mobile you design for a platform. In industrial it is one-off systems based on standard components”.27 This indicates that OEMs would not be able to substitute HPS components for mobile applications with those for stationary applications, because the latter are typically more “standard”, whereas OEMs need components more tailored to their needs.

(74) Therefore, the Commission considers that HPS components that are designed and manufactured for stationary applications would not meet the requirements of OEMs for mobile applications and are not substitutable with one another.

(75) Second, from a supply-side perspective, HPS components for mobile and for stationary applications present important differences, which prevent a manufacturer from promptly switching its production from one type of HPS components to the other.

(76) Indeed, the technical differences explained in recital (45) entail differences in terms of manufacturing processes and equipment which might prevent a manufacturer to switch its production from one type of HPS components to the other in a timely manner and without incurring additional costs.

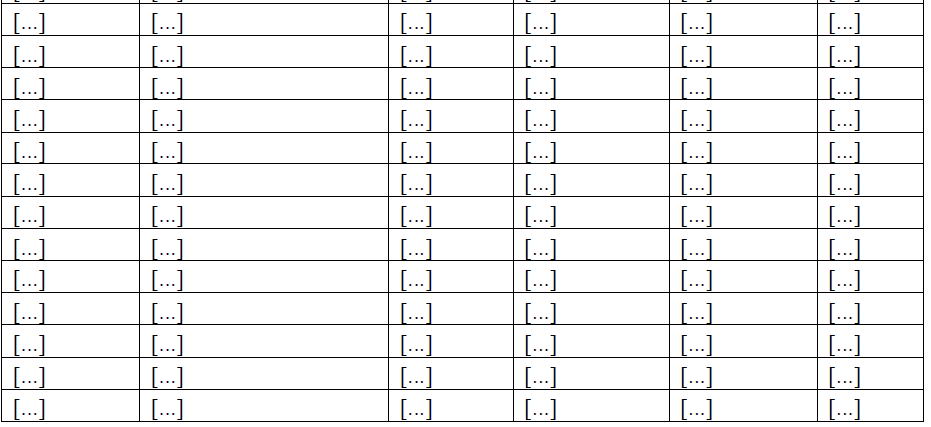

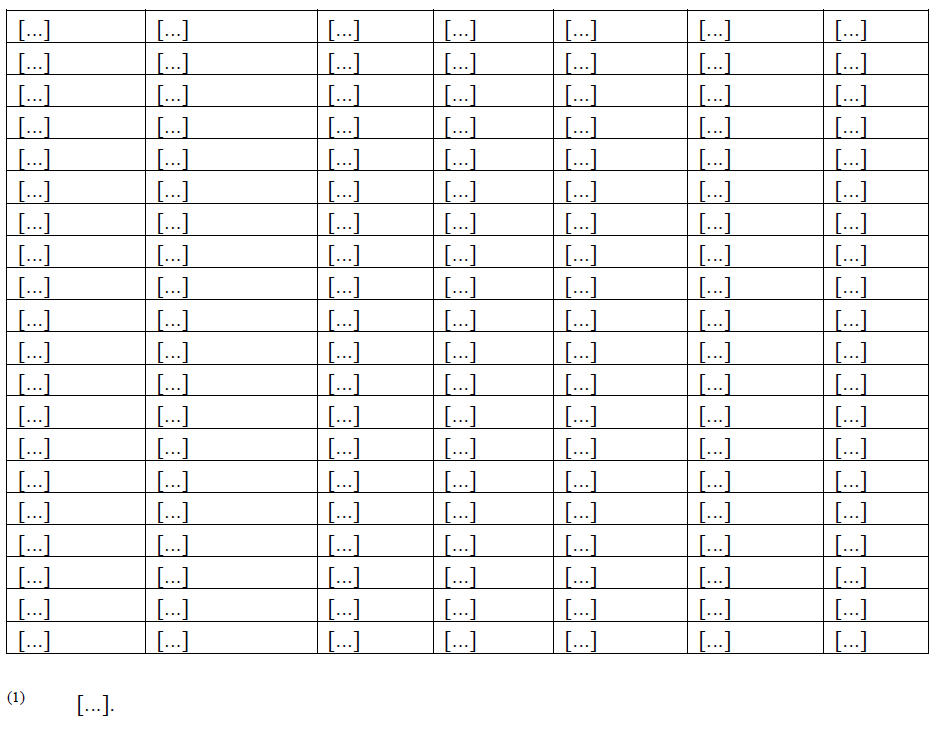

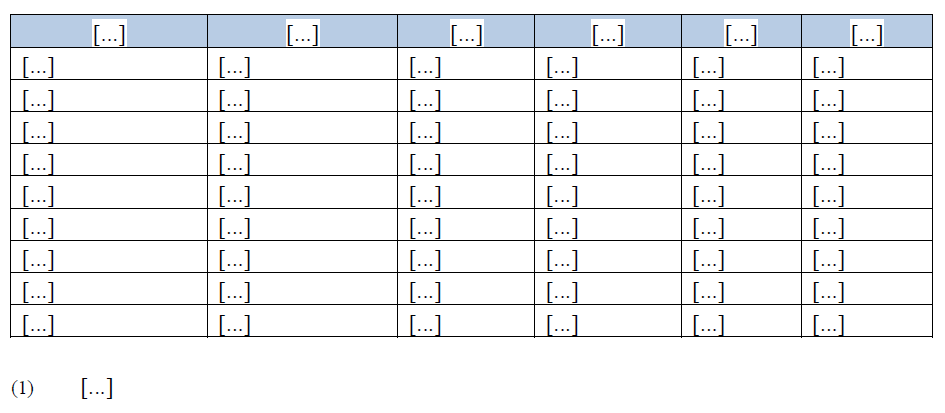

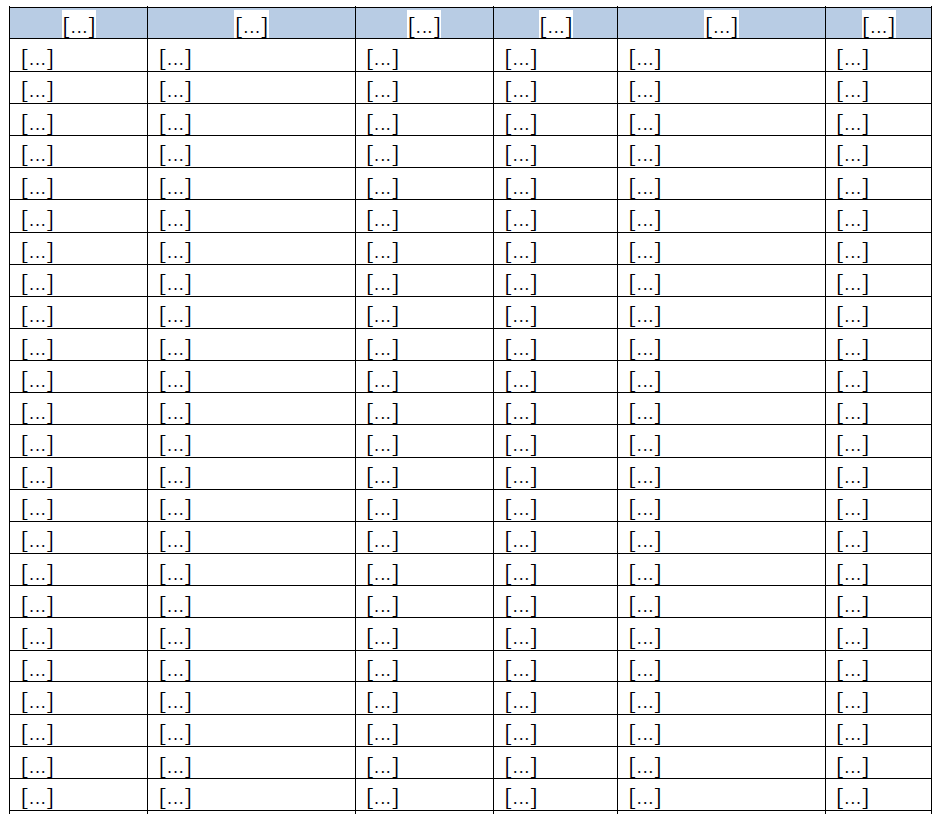

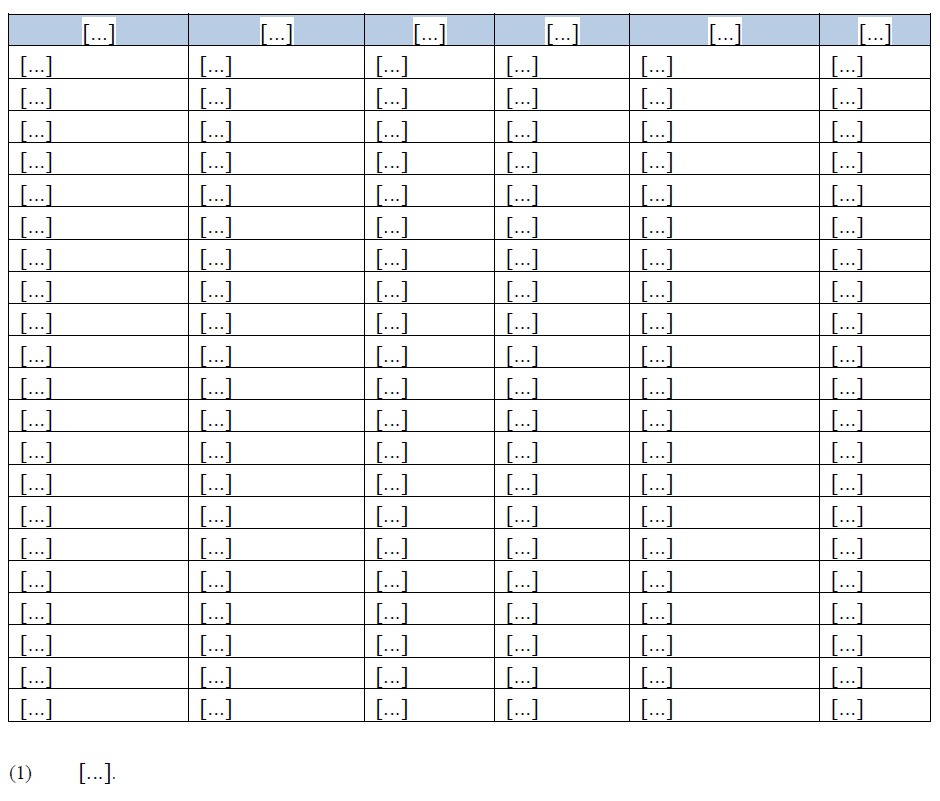

(77) Moreover, an internal document of Eaton, reproduced below as Figure 4, explains that stationary and mobile applications are [content of internal document], which have fundamentally different sales cycles, which entails different business set-ups, business models and organisations.

Figure 4 – Market dynamics of mobile and stationary hydraulic components

[...]

(78) In the third place, the Commission notes that Danfoss entering the markets for stationary applications is part of the Transaction rationale. This suggests that a company active in mobile applications cannot easily enter the market for stationary applications quickly and with limited investment.

(79) On the basis of the evidence gathered during its investigation, and in line with the arguments of the Notifying Party, the Commission therefore finds that HPS components for stationary and for mobile application belong to separate product markets.

6.2.3. Captive production is not part of the relevant markets

6.2.3.1. The Commission’s past practice

(80) The Commission considered the markets for HPS components before. In particular, the Commission considered the market for HPS components in Volvo/Atlas, Bosch/Rexroth and Weichai/Kion.28 The Commission’s precedents however do not analyse whether captive production of HPS components are part of the relevant market.

6.2.3.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(81) The Notifying Party contends that in-house production of HPS components by OEMs is part of the relevant market. In particular, the Notifying Party contends that the ability of OEMs to manufacture hydraulic steering units in-house and to switch from outsourced production to in-house production means that external suppliers compete directly against the OEMs’ in-house production capacities. External suppliers such as Danfoss and Eaton take into account the OEMs’ ability to in-source production when setting their prices. For these reasons, in-house production should be considered as part of the relevant market.29 With regards to ESVs in particular, the Notifying Party claims in the Reply to the SO that ESV suppliers must take into account in-house production when pricing, as OEMs decide whether the ESV business goes to an external supplier or remains in-house and, once an OEM has developed ESV in-house, it can take even more business away from suppliers by marketing its solution to third party OEMs. 30

(82) The Notifying Party further contends that even if the Commission were to consider the merchant market only, the competitive constraint exercised by the OEMs’ in-house production capabilities should be considered in the competitive assessment. 31

6.2.3.3. The Commission’s assessment

(83) On the basis of the evidence gathered during its investigation, and contrary to the arguments of the Notifying Party, the Commission finds that captive production of HPS components is not part of the relevant market.

(84) First, as regard the relevant product markets defined in Sections 6.3, 6.4 and 6.5 below, there is at the most a very marginal in-house production by OEMs which is available to the market and thus influences the competitive conditions.

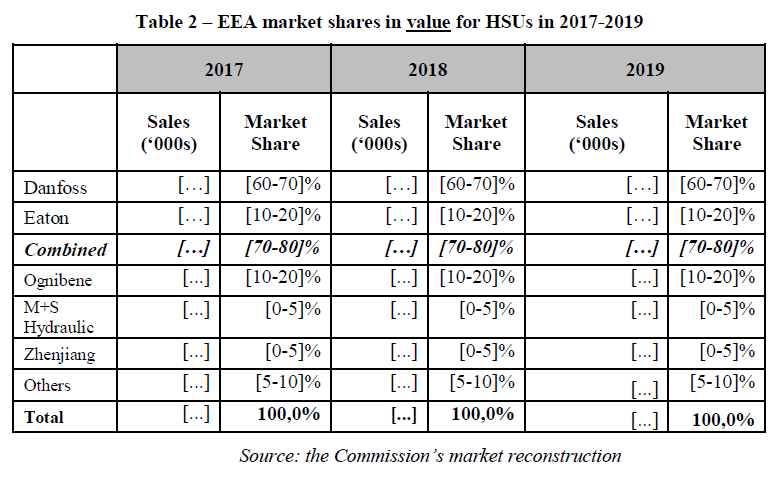

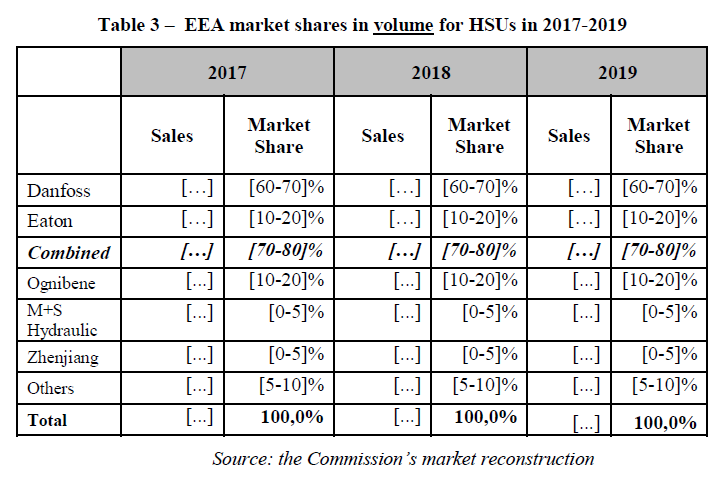

(85) Concerning in-house production of HSUs, all but one OEMs contacted during the market investigation indicated that they currently produce HSUs in-house.32 This is confirmed by the fact that, according to the Notifying Party’s own estimates, the market shares for HSUs in the EEA over the past three years are similar whether in-house production by OEMs is included or excluded. 33 This was confirmed by a competitor of the Parties, which stated “I have been in this market for more than 25years. I have never had any OEM say that they were thinking about developing and manufacturing hydraulic steering units or integrated transmissions.” 34

(86) Concerning orbital motors, the Notifying Party does not claim that any OEM produces orbital motors in-house in the EEA.35

(87) Concerning ESVs, the Notifying Party only identified four OEMs, which would currently produce in-house. However, none of those OEMs appear to be actively selling their components to third parties on the market in any significant way. Indeed, based on the Notifying Party’s own data on past and existing sales opportunities (the ‘Opportunity Data’), none of the four OEMs identified have been considered by other OEMs alongside the Notifying Party for the supply of ESVs over the past 3 years (see Annex I - The Commission’s analysis of the Parties’ opportunity data, hereinafter referred to as ‘Annex I’).

(88) In addition, only a small minority of the Parties’ competitors are aware of (actual or potential) in-house production of ESVs by OEMs. 36

(89) As explained by one OEM, in-house production by OEMs is not a feature of the HPS components markets: “Hydraulic components like steering valves - I think this counts for across all industries - are not since 40 to 50 years produced by OEM's but purchased from suppliers”.37

(90) This view is shared by competitors, one of which, for example, explains that: “OEMs have the design control of their own machines, so they procure what they cannot provide and manufacture internally, for technical or cost reasons mostly. We do not believe that hydraulic suppliers compete against in-house production of their OEM customers. It may have sometimes been the case 10 or 20 years ago.” 38

(91) Second, OEMs that currently purchase the products defined in Sections 6.3, 6.4 and 6.5 below would not consider producing them in-house. OEMs are not interested in producing HPS components in-house, as this is not their core business, and would represent significant investments which would be difficult to recoup even through sales to third parties.

(92) This has been confirmed by a majority of the OEMs which responded to the market investigation. A large majority of OEMs indicated that they do not have enough ability (e.g. know-how, technical skills, IP, etc.) and incentives to start the production in-house in case of a price increase of 5-10%, whether for HSUs,39 ESVs40 or orbital motors.41

(93) The production of HPS components is not the core business of OEMs, which do not have the capabilities and infrastructure to produce them in-house. As explained by one OEM, “our core business is not the in-house production for hydraulic components, we want and we need to buy them”42 Another OEM confirms: “We cannot manufacture such specific hydraulic components ourselves. We have neither the capacity nor the know-how and would have to create a completely new structure for this. This is not a starting point.”43 In fact, several other OEMs have indicated that they “have no interest on in house manufacture”44, or “don't have the manufacturing capabilities and expertise to manufacture hydraulics ourselves.”, 45 nor “the skills and capacity to produce these components ourselves”.46

(94) Consequently, the costs involved in starting the production in-house appears to be an unsurmountable deterrent for OEMs, as “investment are very high to make these components, profitability will be very difficult to be achieved.”47 This is confirmed by another OEM which explains “We are not set up to produce these type of parts and the investment in machines and tools would not make it viable.”48

(95) The fact that OEMs would not have the ability or incentive to start producing HPS components in-house has also been confirmed by competitors contacted during the investigation, a large majority of which indicated that they do not see in-house production by OEMs as becoming a more prominent feature of the market in the next three to five years. 49

(96) Competitors have also confirmed that in-house production is not the OEMs’ core business: “The core competence of the typical OEM´s is the design of a competitive machine and not the development of components or sub-systems which can be purchased from specialized suppliers. Today's machines are so complex that an OEM cannot get involved in the development and production of components and subsystems.” 50

(97) Competitors have also confirmed that consequently, starting producing in-house would require significant and costly investments which would be difficult to recoup. As explained by one competitor: “Steering system are really specific components (with usually a price below 150 EUR for standard steering unit and below 1000 EUR for electronic steering valves) with high manufacturing investment costs. The volumes of each OEM will make almost impossible an acceptable ROI. No critical mass for any of the OEM. ” 51 This is confirmed by several other competitors, according to which “OEM are not showing interest in captive solutions in consideration of the absence of critical mass and limited value of the steering components on total cost for the relevant vehicles.” 52, and “the trend since years is more going to oposite [sic] with a combination of purchase and assembly; the Ratio of In House production is not raising and considered too expensive” 53

(98) Another competitor further explains: “No OEMs have the designs or capability to produce hydraulic steering units. The barriers to entry are extremely high. First, capital spending of several million dollars is required to produce the steering units. The types of equipment are broaching machines, OD and ID grinding machines for gerotor shapes, & flat part grinding machines. Second, there is a very high cost of engineering to develop the steering units. The high cost of engineering is due to the complicated nature of the designs. These complicated devices have an complex rotor sets, fixed clearance with different metals, & high pressure shaft seal designs that are leak free.” 54

(99) Third, OEMs that allegedly manufacture a certain HPS component in-house are not suppliers to other OEMs. Therefore, in the event of a price increase of a certain HPS component, only those OEMs that manufacture it in-house might decide to manufacture more of it and to reduce their purchases from external suppliers. However, as further explained in recital (100) below, the results of the market investigation have shown that such a possibility is not taken into account in commercial negotiations between suppliers and OEMs. The remaining OEMs (which represent the majority of the OEMs) would have not this choice, and would not be able to switch to components manufactured in-house.

(100) Contrary to what the Notifying Party indicates in the Reply to the SO, the Commission considers that the threat of switching to or increasing in-house production is not factored into the commercial negotiations between OEMs and suppliers. In fact, a large majority of competitors which replied to the market investigation stated that in-house production, whether actual or potential, is not brought up by OEMs in the context of commercial negotiations.55 A large majority of competitors who manufacture the product also indicated that they do not take into account in-house production by OEMs when setting their prices or strategy, whether for ESVs or HSUs.56

(101) Based on the evidence gathered during its investigation, the Commission therefore considers that in-house production by OEMs is not part of any relevant product market.

6.3. Hydraulic steering units

6.3.1. The Commission’s past practice

(102) The Commission previously examined markets for HPS components, in particular, in Volvo/Atlas and Bosch/Rexroth.57 However, Commission’s previous decisions did either not deal specifically with HSUs or leave the market definition for HSUs open.

6.3.2. The Notifying Party’s view

(103) The Notifying Party is of the view that HSUs constitute a separate product market from other steering components, and other HPS components generally (such as pumps, motors and valves). The Notifying Party also considers HSUs to be in a separate market from components used to achieve electrohydraulic steering such as ESVs.

(104) The Notifying Party however submits that the market for HSUs should also encompass electric steering systems.58 This is for the following main reasons: 59

(a) There is a trend towards electrification of steering, which is increasingly competing with, and affecting the supply of, hydraulic steering units in Europe and the USA.

(b) Electric steering has already replaced hydraulic steering in vehicles such as forklifts and other smaller material handling vehicles, where limited steering force is needed.

(c) If an OEM opts for an electric system at the design phase, the HSUs are “out of the game”.

(d) Although hydraulic steering is still the prevailing technology for heavier vehicles, the Parties expect that electric steering will become an alternative for heavier vehicles as well.

(105) Consequently, the Notifying Party contends that electric steering is increasingly an alternative to HSUs and should be considered as part of the relevant market, or that at a minimum, electric steering exerts a competitive constraint on the Parties, which would have to be considered in the Commission’s competitive assessment.60

6.3.3. The Commission’s assessment

(106) The Commission concludes, based on the examined evidence, that HSUs form a distinct market from other HPS components for the reasons explained in Section 6.2.1.3. The Commission also considers that HSUs should be considered a separate product market from ESVs. Furthermore, the Commission concludes that electric steering does not form part of the market for HSUs.

6.3.3.1. HSUs and ESVs are part of different product markets

(107) The Commission is of the view that HSUs and ESVs are part of separate product markets.

(108) First, HSUs and ESVs are not substitutable from a demand-side perspective.

(109) Technically, they are distinct. HSUs uses pressurised hydraulic fluid generated by pumps to move an actuator (cylinder) that moves the wheels. Electrohydraulic steering, on the other hand, is still hydraulically powered but electronically controlled, for example by a joystick. Electrohydraulic steering can be achieved through an ESV which converts the hydraulic oil to the cylinders in proportion to the electronic input signal.61 The Notifying Party notes that “[c]ompared to Hydraulic Steering, Electrohydraulic Steering is technically more advanced in that it provides steering by a joystick and similar electronic input devices as well as GPS auto-guidance functionality. This improves the ergonomics, the driver comfort, and productivity of the machine.”62

(110) The results of the market investigation also suggest they are distinct. Respondents to the market investigation indicated that there is a limited demand-side substitutability between HSUs and ESV-based electrohydraulic steering. In particular, it appears that OEMs have limited possibility to switch between HSUs and electrohydraulic steering units:

* Switching between HSUs and ESVs appears to be difficult even in the initial design phase when an OEM designs the product for which the steering unit is required. When asked about the effort it takes an OEM to switch from HSUs to ESVs in the development stage of a new product, only one OEM replied that switching was easy, while a large majority stated that switching was either possible but with some costs and/or timely setback or difficult with considerable financial and/or timely setback. 63

* Switching between HSUs and ESVs would be even more difficult at the production phase, where the OEM has already started production based on a chosen design. When asked about the effort it takes an OEM to switch from hydraulic steering units to electrohydraulic steering with an ESV after starting producing a new product: a majority of OEMs stated that switching was difficult for considering financial and/or timely setback, while four even indicated that switching was impossible. 64

(111) This suggests that the two technologies are most likely not interchangeable, and therefore not competing, from a demand-side perspective at the initial design phase. This conclusion can be drawn even more clearly in relation to the production phase. One competitor explains that “[t]he change needs a redesign of the steering system, electrohydraulic steering valves need to be added and integrated into the machines design / dimensions. Therefore requires significant effort / cost and is not possible after SOP.” 65 Yet another competitor further explains that “[s]witching from hydraulic steering units to electrohydraulic steering units will always require a not negligible effort in hardware and software integration within the vehicle. Moreover, the test and the homologation phase will be much more expensive.” 66 Another competitor considers that switching is not possible during the production stage: “This is an architecture change and needs to be defined prior to the start of the program[me].” 67

(112) In addition, there appears to be a considerable difference in price between HSUs and electrohydraulic steering solutions. According to the Notifying Party, the average sales price for an HSU would be EUR [...]; whereas the price of an ESV plus an HSU as a back up would be EUR [...]. In addition a pure ‘Steer-by-Wire’ system which is entirely based on ESVs68 would be about EUR [...]. These price variations point at a lack of substitutability from a customer perspective, and HSUs forming a separate market from electrohydraulic steering.

(113) Second, HSUs and electrohydraulic steering are also not substitutable from a supply-side perspective.

(114) HSUs and electrohydraulic steering units present important technical differences, which prevent a manufacturer to promptly switch its production from one type of steering unit to the other. ESV appear to require considerably distinct technology and know-how as compared to their hydraulic counterparts.

(115) As explained by one competitor: “From hydraulic steering to electro-hydraulic steering is already a significant step in know-how and understanding of developing and producing the products. It takes a lot of time for hydraulics companies to develop similar products.”69

(116) This has been confirmed by the market investigation, during which a large number of competitors have indicated that HSU, electrohydraulic units and fully electric steering require different capabilities from a manufacturing perspective and have limited degree of supply-side substitutability.70

(117) According to one competitor, the solutions entail “different products, functioning and technology”.71

(118) Given the lack of both demand-side and supply-side substitutability between HSUs and electrohydraulic steering systems, the Commission therefore considers that HSUs and electrohydraulic steering systems are not part of the same product market.

6.3.3.2. HSUs and electric steering are part of separate product markets

(119) Based on a review of the available evidence, the Commission considers that electric steering does not form part of the same product market with HSUs.

(120) First, electric steering systems are technically distinct from hydraulic steering systems. In electric steering the power-assist is generated by electric motors, rather than via hydraulic power as is the case for hydraulic steering systems. Electric steering systems eliminate the need for hydraulic components such as an HSU, pumps, hoses and a drive belt connected to the engine. The entire electric system can be packaged on the rack-and-pinion steering gear or in the steering column. 72

(121) Second, from a demand-side perspective, HSUs and electric steering systems are not substitutable.

(122) In the first place, a large majority of the OEMs that responded to the market investigation indicated that substitution of a hydraulic steering system with a fully electric steering system is not a cost-effective option. 73 A number of OEMs explained that electric steering systems have technical, economical and customer acceptance limitations when compared with hydraulic steering systems. 74

(123) One OEM explains: “there is a trend for electrification, which might potentially replace hydraulic systems in the future. However, a complete replacement of hydraulic systems with electric ones can take place only when machines are fully electrical (i.e. when diesel engines are replaced by batteries and electric motors, and the different actuators as linear actuators as hydraulic cylinders will be replaced by fully electrical sub systems). The Company considers that in the mobile sector such a trend will take a long time and is not foreseen to occur on a large scale in the near future. Electrical machines are expected to remain a niche for several years”75

(124) The Notifying Party contends that from a functionality perspective the electric steering product is more comparable with a hydraulic steering system including a HSU, pump, cylinders, valves, hoses and fittings, rather than with the HSU alone, which undermines any attempt at comparing prices of HSUs with those of electric systems. However, the cost of the electric system is prohibitive even if compared to that of the hydraulic system as a whole, which will prevent electric systems from successfully challenging hydraulic solutions at a large scale in the near future.

(125) The estimates put forward by the Notifying Party of an average sales price per unit of EUR [...] for HSU system and between EUR [...] and EUR [...] for electric steering confirm this cost disparity. 76

(126) In addition, results from the market investigation have indicated that the fully electric system is not a cost-effective option, not only because of the sheer price of the system as compared to that of the hydraulic one, but also taking into account switching costs (e.g. development, design, testing).

(127) For example, one large OEM explained that “[u]sually [an] electric steering system is more expensive”,77 and another OEM pointed out that “the change [from hydraulic to electric] would be very deep”. A number of OEMs that replied during the market investigation indicated that technical changes, extensive tests and the related costs are a limiting factor. For example, one OEM explained that “[n]ew system integration and full validation is need , specially critical for machine on road applications”78 and another added that “[t]o make the two different systems interchangeable would require extensive and costly application development”.79 One OEM explained that the changes would require different electronic systems and therefore the technical areas of competence would be different from the current ones.

(128) When asked how much effort it takes an OEM to switch from hydraulic steering units to electric steering at the design phase, a large majority of competitors have either indicated that some costs and timely setback would be involved, or that switching was difficult with considerable financial and/or timely setback. 80 At the production phase, a large majority of competitors responded that switching was difficult with considerable financial and/or timely setback. 81

(129) One large competitor explains: “In case it would be technically feasible the change needs a full redesign of the steering system, therefore requires significant effort / cost and is not possible after SOP.”82 Another competitor further indicates that: “Switching from hydraulic steering units to electric steering units will always require a not negligible effort in hardware and software integration within the vehicle. Also, the test and the homologation phase will be much more expensive.”83

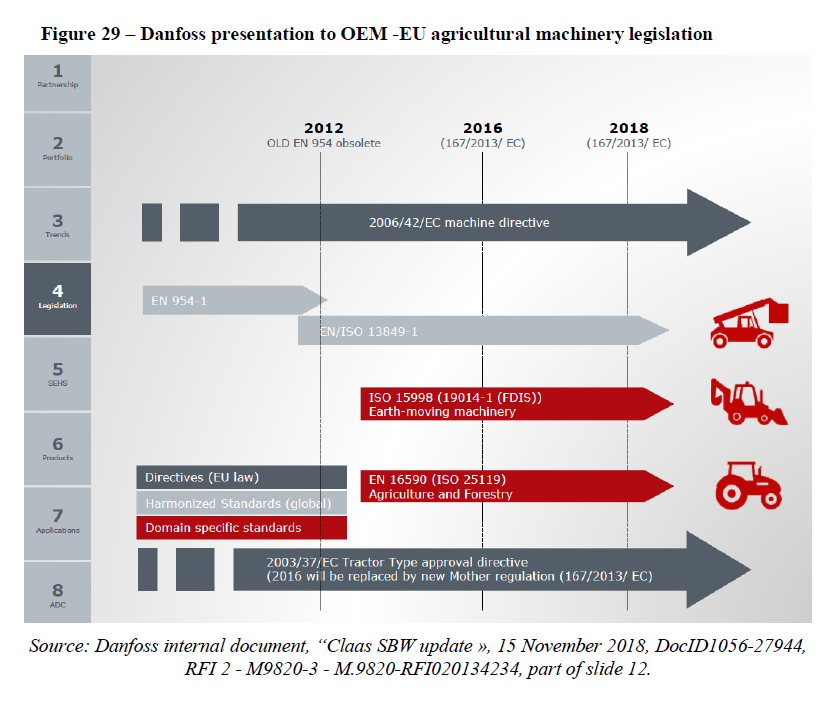

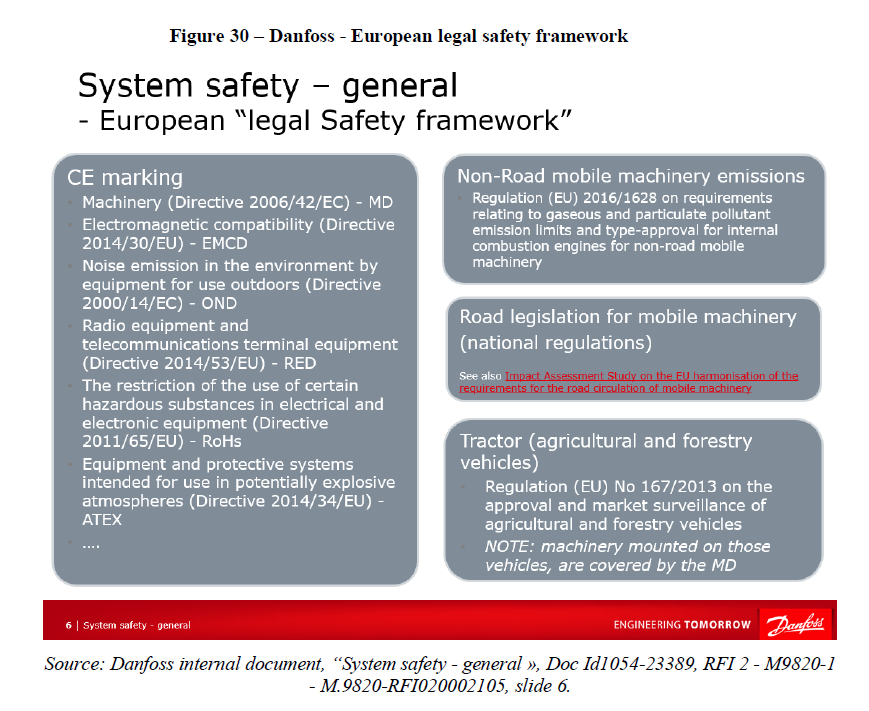

(130) Furthermore, the market investigation has yielded indications that for a non-insignificant number of OEMs, the substitution of a hydraulic steering system with an electric steering system would also entail overcoming regulatory barriers and testing requirements.84 One OEM explained that “from a regulatory point of view, it is not possible to use electric steering on the road because it would not be compliant (NF-1459). From a technical point of view, the torque on the wheels that we have are too large, therefore we must use hydraulic steering systems”.85 Another OEM stated that: “[T]he steering is a safety components and must be fine tune according to machine performances and specifications. In addition long expensive tests must be carried out to validate the steering system. ”86

(131) Moreover, distributors that replied during the market investigation share the OEMs’ point of view. A large majority of them considers that electric steering and hydraulic steering systems either are not substitutable at all, or that they are substitutable only for certain machines. 87 In particular, one distributor explains that for smaller OEMs, switching to electric steering systems might be even more problematic than for larger OEMs: “[f]ully electronic steering units require electrification in CanBus level, where some of OEM applications are not so sophisticated yet. This would mean increased cost of the machine, whereas [a] standard out-of-the-box hydraulic steering unit is cheaper just to implement [the] hydraulic system. The bigger OEMs has [sic] different capabilities and more sophisticated system architecture already, and with higher quantities unit cost could be closer”.88

(132) In the second place, internal documents of the Parties suggest that they themselves consider that electrification of machines will remain limited in the near future. The documents suggest that this is due to the costs involved from a demand- and a supply-side perspective and technical limitations which mean that not all machines are subject to potential electrification.

(133) For example, a study conducted by Eaton reveals that, due to the high costs of batteries, in the years to come electrification will [...]. Meanwhile, Danfoss’ documents suggest that electric steering is seen as [content of internal document].89 Another Danfoss internal document suggests that electrification is [content of internal document]. In relation to agriculture, it is stated that: “[content of internal document]”; however, “[content of internal document]”. In relation to construction, it is stated that “[content of internal document].”90 This suggests that electrification is not an option for all machines in agriculture and construction.

(134) One competitor also stated that: “It's a topic too cost sensitive. In the near future however, we might see fully electric components for lighter machines.” 91, while another said “Power density is the current limit to alternative steering systems.”, 92 suggesting that the possibility to switch to fully electric systems is impacted by the level of power required.

(135) Third, from a supply-side perspective, HSUs and electric steering systems are not substitutable.

(136) In the first place, HSUs and electric steering systems are based on entirely different technologies, which require different production techniques and capabilities, so that a manufacturer could not readily switch production to electric steering systems in the short term without incurring significant additional costs or risks in response to small and permanent changes in relative price.

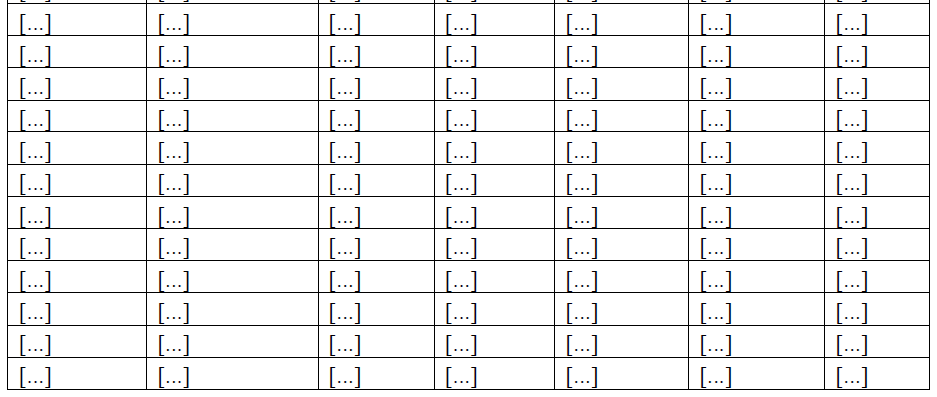

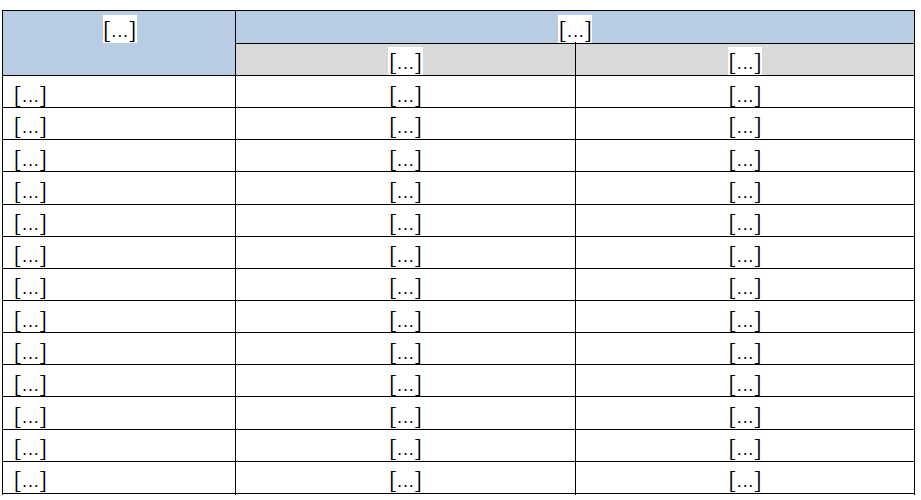

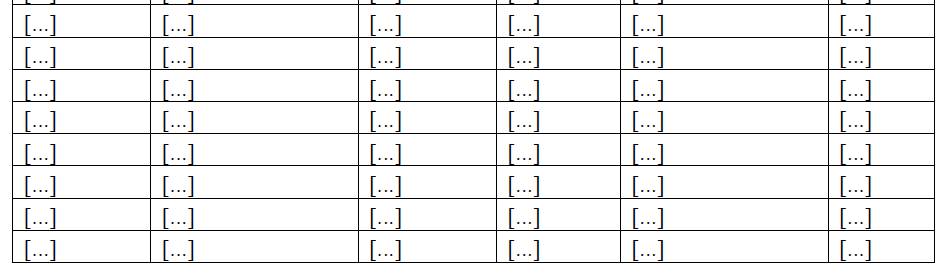

(137) The technical specificities of a fully electric steering system as compared to a hydraulic steering system require significant production modifications. As explained in an internal document of the Parties reproduced in Figure 5 those represent [content of internal document].

Figure 5 – Eaton’s assessment of main challenges for electric systems

[...]

Source: Reply to pre-notification RFI PN 5, Annex A.4_8.

(138) In the second place, the fact that starting producing electric system would represent significant costs and risks is exemplified by the Notifying Party’s own business strategy in this regard.

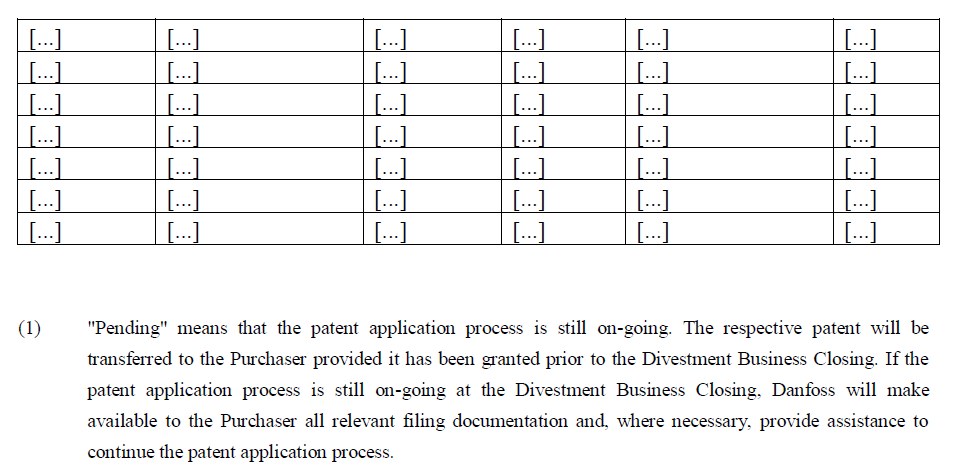

(139) For example, an internal document of the Notifying Party (Figure 6), which is active in the production of HSU, explains that it [content of internal document].

Figure 6 – Eaton’s assessment of main challenges for electric systems

[...]

Source: Reply to post-notification RFI 2, DocID 1058-38361, “M.9820-RFI020181219.pptx”, slide 3.

(140) The Commission concludes that substitution from HSUs to electric steering is difficult and not cost-effective from both a supply and a demand-side perspective. It appears to be particularly challenging for larger applications; however, the conversion from hydraulic to electric appears to be limited even in relation to smaller machinery. The Notifying Party indicates that electrification is already occurring for smaller crane and material handling machines, in particular, forklifts. However, forklifts are just one type of machine and the material handling segment only represents a proportion the overall application segments.93

(141) Given the lack of both demand-side and supply-side substitutability between HSUs and electric steering systems, the Commission therefore considers that HSUs and electric steering systems are not part of the same product market.

6.3.3.3. HSU mobile components for on-road and off-road applications

The Notifying Party’s view

(142) The Notifying Party explains that so-called “on-road” vehicles can refer to trucks (conventional, without a specific work function), buses, and coaches, as well as specialized on-road vehicles with specific work functions such cement mixer trucks.94

(143) The Notifying Party contends that no separate markets should be defined for, on the one hand, HPS components used in those specialized on-road vehicles, which should in fact fall under the off-road category, and, on the other hand, HPS components used in vehicles, which primarily drive off-road, such as tractors, harvesters, road graders, cranes, wheel loaders or excavators.95

The Commission’s past practice

(144) In its decision in Volvo/Atlas,96 the Commission defined separate market for individual mobile hydraulic components. The Commission did not further consider whether a distinction between on-road and off-road applications was warranted within the separate markets for individual mobile hydraulic components.

The Commission’s assessment

(145) Contrary to the Notifying Party’s view, the Commission concludes that HSUs for on-road vehicles with work functions are not part of the same product market as off-road vehicles.

(146) First, the Commission finds that the Parties’ themselves in their ordinary course of business documents only consider the supply of HSUs for the off-road market without HSUs for on-road vehicles.

(147) Second, the Commission finds that there is limited demand-side substitutability. In particular, customers of HSUs for off-road vehicles do not tend to buy HSUs for on-road vehicles with work functions.

(148) Third, the Commission finds that there is limited supply-side substitutability. In particular, HSUs for on-road vehicles with work functions work with completely different technologies compared to HSUs for off-road vehicles.

(149) Fourth, the Commission further found that the market position of suppliers is significantly different in these two categories. In fact, most of the competitors supplying HSUs for on-road vehicles with work functions do not offer those for off-road vehicles and vice versa.

6.3.3.4. The market for HSUs is differentiated

(150) The Commission considers, based on the examined evidence, that the market for HSU is comprised of differentiated products, with distinctions based on end-use, quality and geographic focus.

(151) While the Commission has not found these different features to justify an even narrower product market definition, it preliminarily concludes that such products belong to a single although differentiated product market.

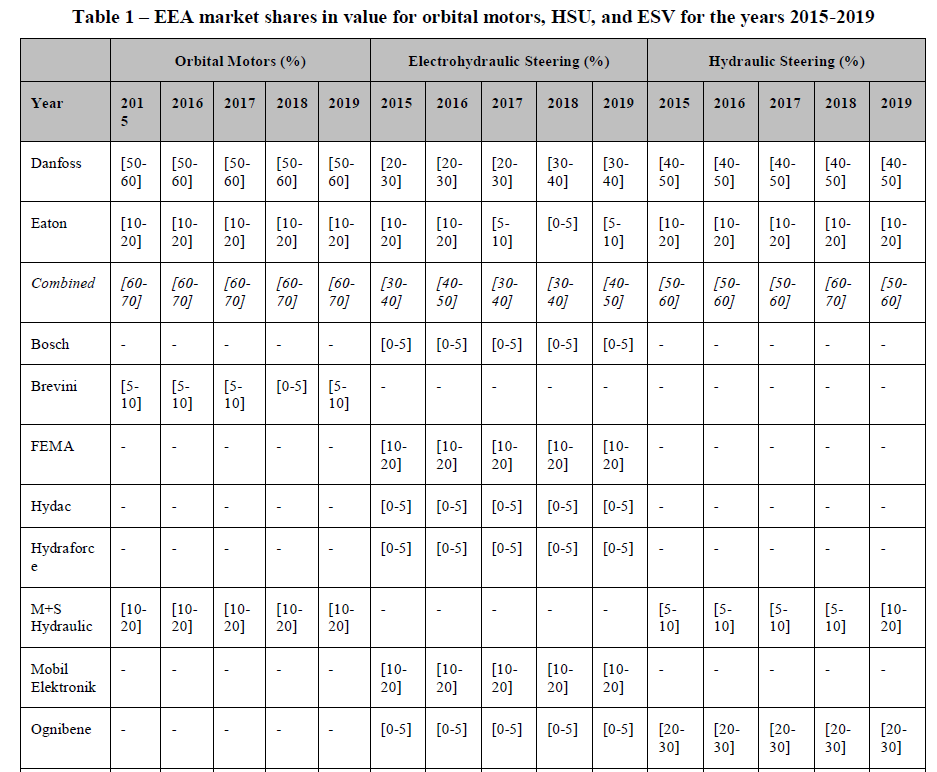

(152) First, a large majority of the OEMs that replied during the market investigation indicated that HSUs for a certain end-use (e.g. for agriculture, for construction or for forestry) can never or only sometimes be substituted with HSUs for another end-use.97 The Parties’ internal documents focus on specific end-applications such as, for example, tractors or wheel loaders. 98

(153) Further, internal documents of the Parties indicate that a certain differentiation in terms of features and overall grade99 of the HSUs (also referred to as “tier”) exists.100

(154) Second, there are some differences in terms of quality between the different HSUs offered by various competitors on the market.

(155) M+S Hydraulic is mainly focused on the steering aftermarket101 and its products are not perceived to be of the same quality or performance levels as those of Danfoss and Eaton.102 Moreover, Danfoss and Eaton also hold important patents, which are not available to other players. 103 Chinese suppliers are not perceived to offer HSUs of the same quality as those of Danfoss or Eaton. This is also demonstrated by the lack of a market presence of companies like Zhenjiang and Sinjin Precision in the EEA to date. A large majority of OEM respondents to the market investigation indicated that they had never purchased HSUs from a Chinese supplier. 104

(156) Third, manufacturers of HSUs do not all have the same geographic strategy. Danfoss and Eaton are larger players with a global presence whereas Ognibene and M+S Hydraulic are smaller and more geographically focused players. 105

(157) As a result, the Commission considers that the market for HSUs is a differentiated market. The Commission will consider the impact of this conclusion in the competitive assessment in Section 8.3.3.1.

6.3.3.5. Conclusion on the product market definition for HSUs

(158) In conclusion, in the light of the considerations in Sections 6.3.3.2 and 6.3.3.3, and taking into account the results of the market investigation and of all the evidence available to it, the Commission considers that there is a market for HSUs for off-road applications separate from on-road and separate from the markets for electrohydraulic steering and electric steering.

(159) The Commission further considers that the market for HSUs is a differentiated market, for the reasons exposed in Section 6.3.3.1, with potential distinctions by end-use, quality and “tiers”.

6.4. Electro-hydraulic steering valves

6.4.1. The Notifying Party’s view

(160) Within electrohydraulic steering, the Notifying Party considers that the definition should include all ways to provide electrohydraulic steering functionality, i.e. integrated solutions, combined solutions, steering valves without safety functionality and ‘pure Steer-by-Wire’ (where the electrohydraulic steering system has no back up hydraulic steering unit). 106 The Notifying Party therefore included in the same market ESVs used in all electrohydraulic steering solutions because all solutions are targeted at achieving the same functionality namely to employ electronically controlled components, which make steering with a joystick or (automatic) GPS-guided steering functions possible.

(161) Further, the Notifying Party considers that electric steering and alternative electrohydraulic steering solutions based on motors such as Ognibene’s solution exerts a competitive constraint on electrohydraulic steering.

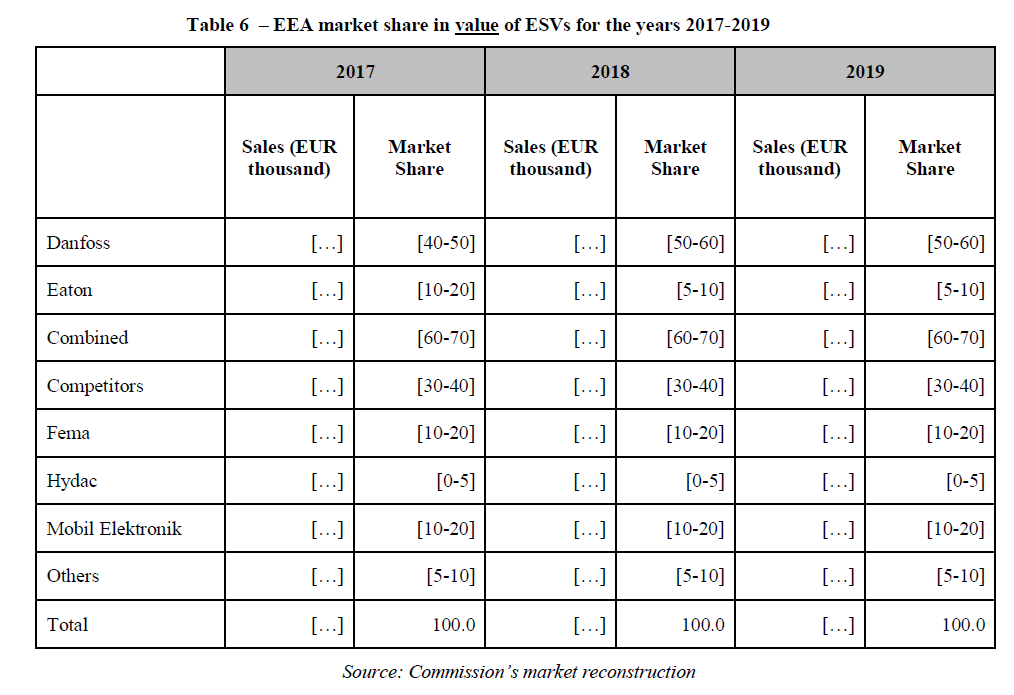

(162) In the Reply to the SO, the Notifying Party further contends that the Commission is wrong to exclude alternative electrohydraulic steering solutions from the market, in particular the solution developed by Ognibene. In particular, the Notifying Party contends that there is no specific demand for ESV-based solutions, and that a customer would consider Ognibene’s solution alongside the one of the Parties. 107

6.4.2. The Commission’s past practice

(163) The Commission previously examined markets for HPS components. In particular, the Commission examined components for HPS in Volvo/Atlas and Bosch/Rexroth.108 However, the Commission’s previous decisions do not deal specifically with ESVs.

6.4.3. The Commission’s assessment

6.4.3.1. ESVs used in all electrohydraulic solutions form part of the same product market

(164) The Commission agrees that ESVs used in all electrohydraulic solutions are part of the same market.

(165) An ESV is most often an essential component for mobile machines using electrohydraulic steering, whereby the steering unit is still hydraulic but electronically controlled, for example by a joystick. The ESV conveys the hydraulic oil to the cylinders in proportion to the electronic input signal.

(166) First, from a demand-side perspective, ESVs can be used in two different types of electrohydraulic steering systems: 109

(a) A steering system design that consists of both an HSU and an ESV. This traditional steering system design is hereinafter referred to as ‘Elect rohydraulic Steering’.

(b) A steering system design that consists only of one or two (redundant system) ESV(s) (i.e., no HSU). This steering system design is hereinafter referred to as ‘Steer-by-Wire’.

(167) The use of ESVs for both Electrohydraulic Steering and Steer-by-Wire was confirmed by customers of ESVs during the market investigation. Indeed, a majority of OEMs which have indicated that they purchase ESVs have indicated that they purchase ESVs both for traditional Electrohydraulic Steering solutions and for Steer-by-Wire solutions.110.

(168) This was also confirmed by internal documents of the Parties. In particular, one document from Eaton indicates that Eaton’s ASV60 ESV can be used for both Electrohydraulic and Steer-by-Wire technologies.

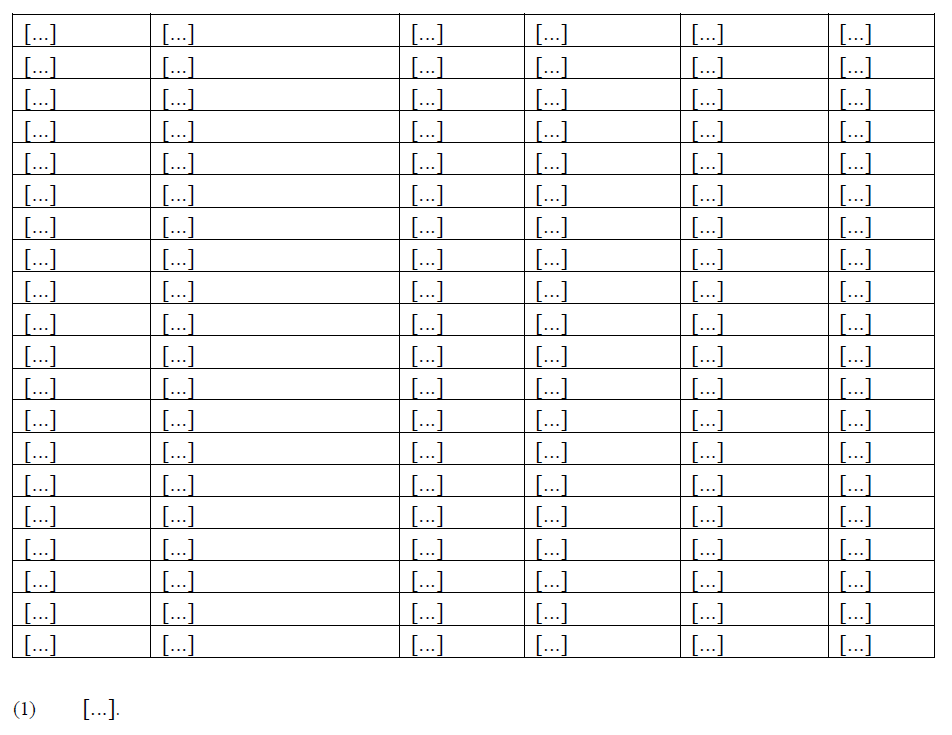

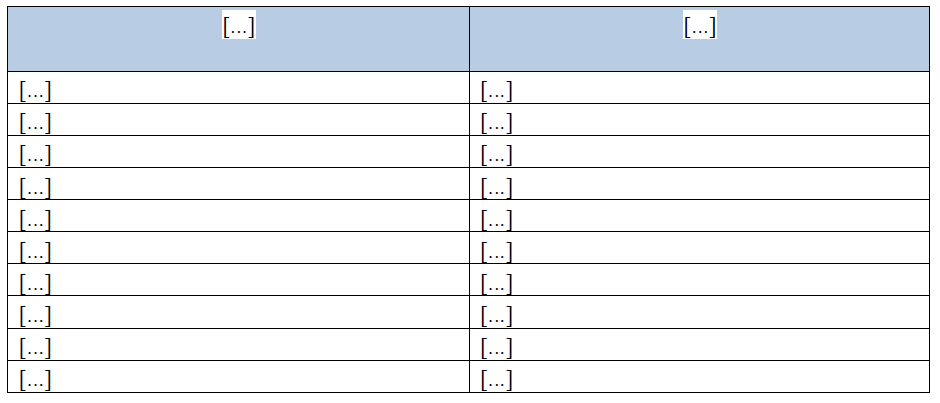

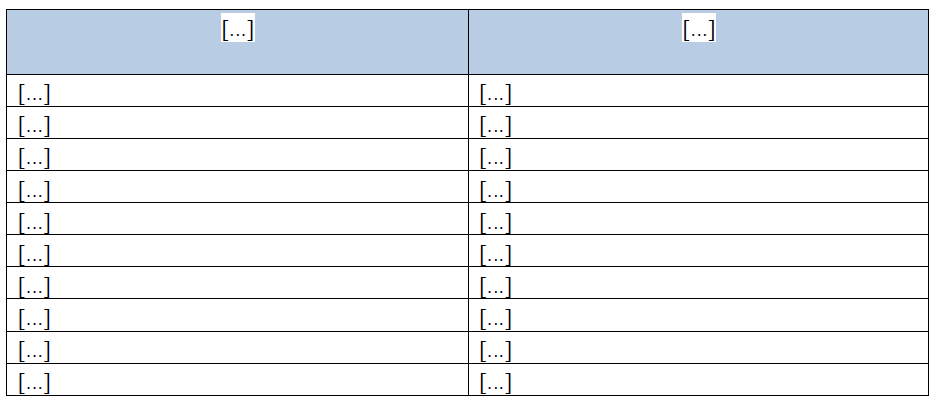

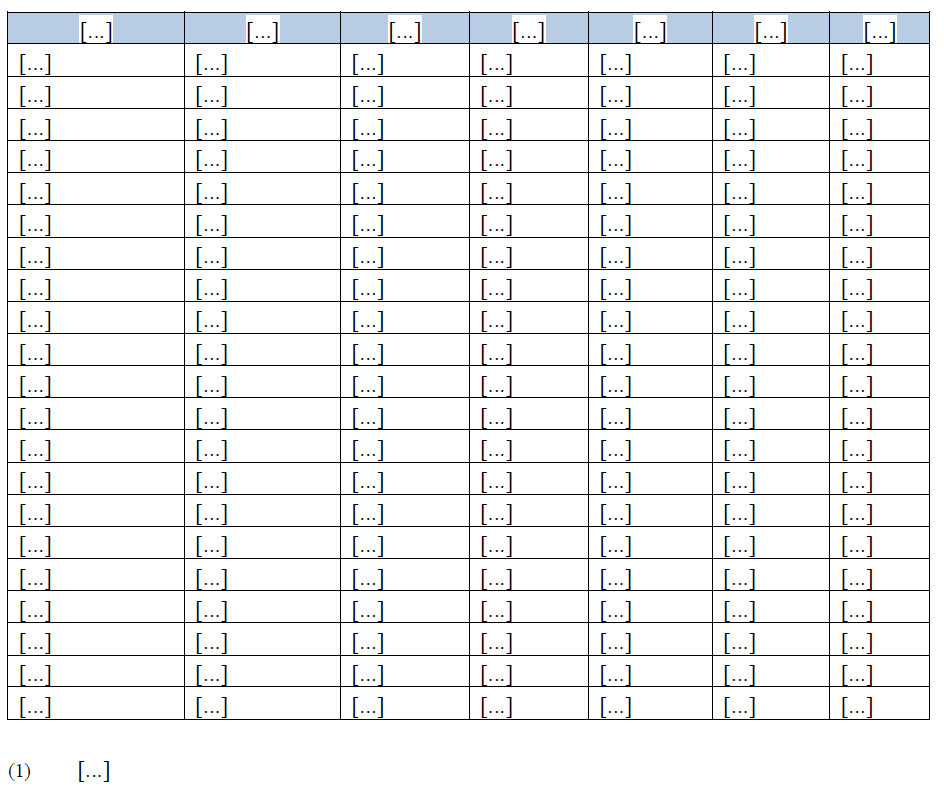

Figure 7 – Eaton ESV can be used in different electrohydraulic steering solutions

[...]

Source : DocID 1043-81559 (Filename EAT-215246.pdf)

(169) ESVs in Electrohydraulic Steering and Steer-by-Wire solutions enable the same features. As demonstrated by an internal document from the Notifying Party, both Electrohydraulic Steering and Steer-by-Wire employ electronically controlled components, such as the ESV, which make steering with a joystick or (automatic) GPS-guided steering functions possible. As shown in Figure 8 below, both Electrohydraulic Steering and Steer-by-Wire offer GPS auto-steering interface, joystick steering, and variable steering ratio, as well as better high-speed controllability for on-road vehicles.

Figure 8 – Traditional electrohydraulic steering and steer by wire solution offer common benefits

[...]

Source: DocID 1054-43057 (Filename: M.9820-RFI020003031.pdf)

(170) Second, from a supply-side perspective, manufacturers of ESVs can potentially supply products for both traditional Electrohydraulic Steering and Steer-by-Wire. For example Bosch Rexroth, FEMA, Hydac, MOBIL ELEKTRONIC, and Hydraforce offer ESVs. However, the ESV offered by these suppliers can be, and is, combined with an HSU manufactured by a different supplier (e.g., Danfoss, Eaton, or others). For example, John Deere uses FEMA ESV with a Danfoss HSU on tractors, combines, and sprayers. Similarly, BOMAG GmbH uses a HYDAC ESV together with a Danfoss HSU on its rollers.111

(171) The Commission therefore considers that all ESVs used in any type of electrohydraulic solution are part of the same market.

6.4.3.2. Distinction between ESV and electric steering units

(172) As a preliminary remark, the Commission notes that the Notifying Party does not contend that ESVs and electric steering form part of the same product market, but rather that electric steering exerts a competitive constraint on ESV. 112

(173) First, as explained in Section 6.3.3.2 above, from a demand-side perspective, fully electric solutions are not yet substitutable with other steering solutions such as HSUs or ESVs.

(174) As noted in recital (123) above, one OEM explains: “there is a trend for electrification, which might potentially replace hydraulic systems in the future. However, a complete replacement of hydraulic systems with electric ones can take place only when machines are fully electrical (i.e. when diesel engines are replaced by batteries and electric motors, and the different actuators as linear actuators as hydraulic cylinders will be replaced by fully electrical sub systems). The Company considers that in the mobile sector such a trend will take a long time and is not foreseen to occur on a large scale in the near future. Electrical machines are expected to remain a niche for several years”113

(175) Second, this trend is not yet sufficiently mature in the market as a whole and the only penetration area is limited to smaller, lighter machines. Indeed, corroborated by Danfoss internal correspondence from ordinary course of business, fully electric solutions are only likely to concern smaller vehicles like [...]. For bigger vehicles, i.e. 400-700 volts, fully electric solutions are “currently not a big market need”.114 As summarised by a competitor: “It's a topic too cost sensitive. In the near future however, we might see fully electric components for lighter machines.”115 Another competitor further explains: “I consider electric steering as full electric without any hydraulics. Therefore the applicability to heavy construction machines and agriculture machines needs to be questioned in general due to high load forces, which might require Hydraulic actuators for the final movement of the axle. In case it would be technically feasible the change needs a full redesign of the steering system, therefore requires significant effort / cost and is not possible after SOP. ”116

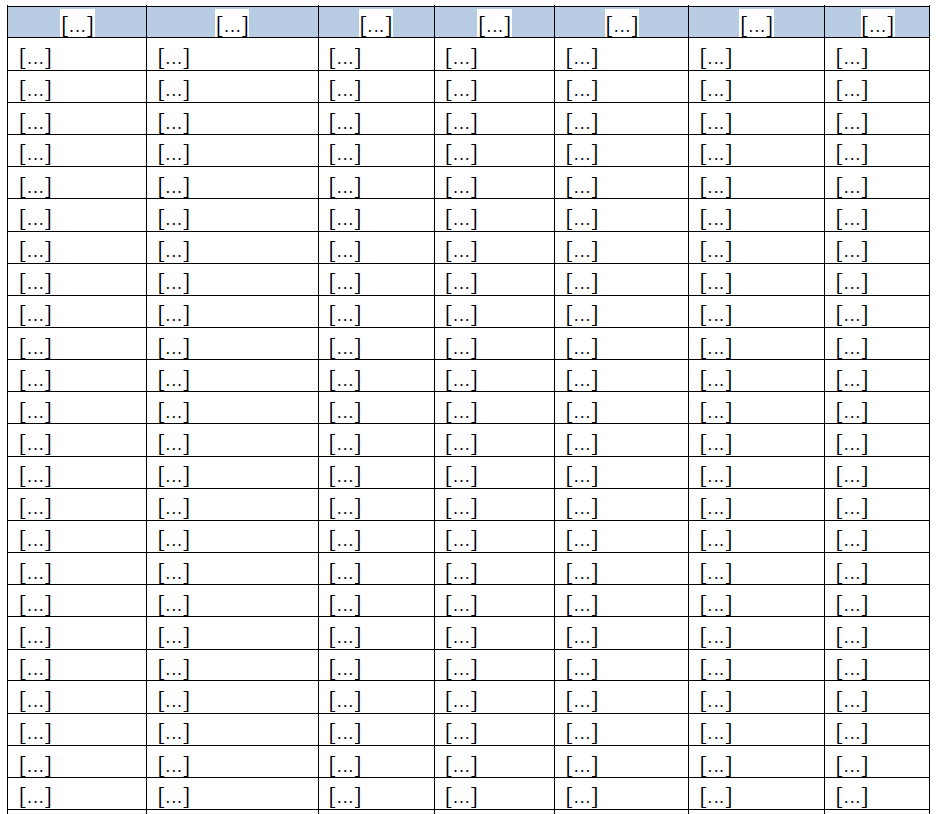

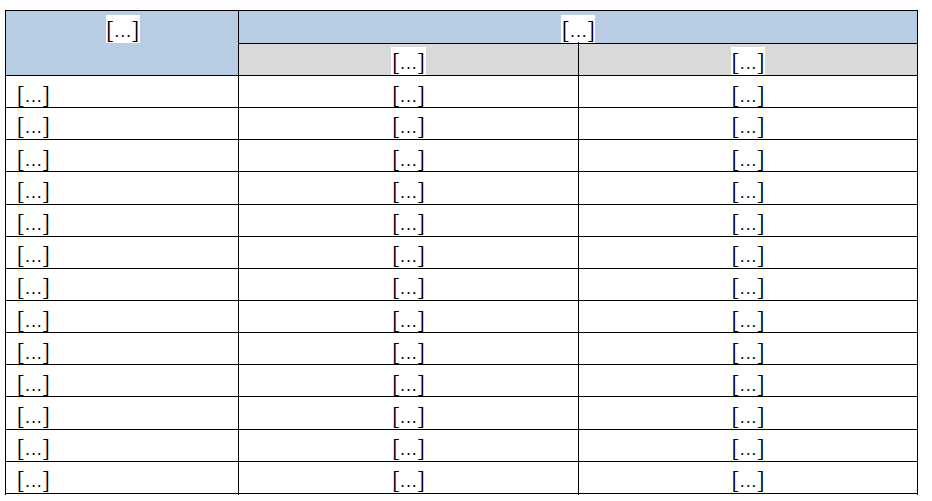

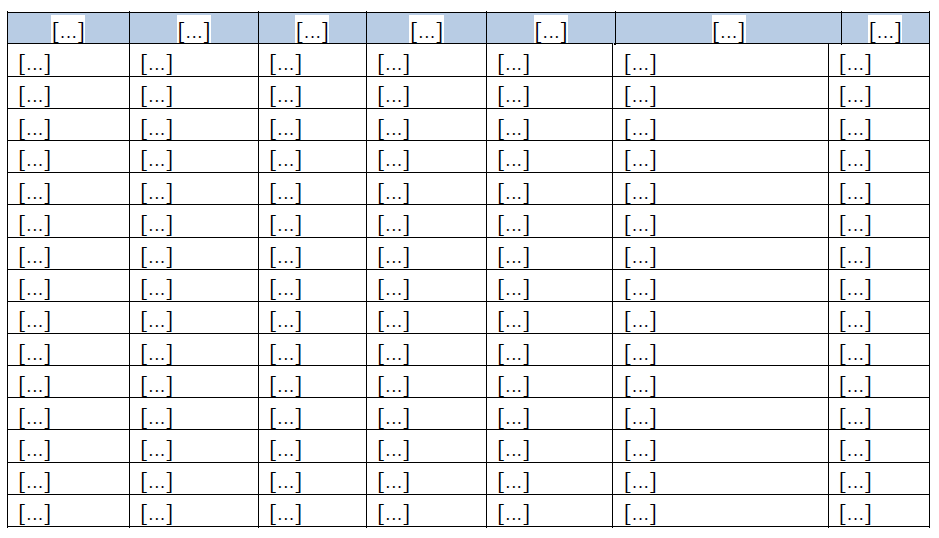

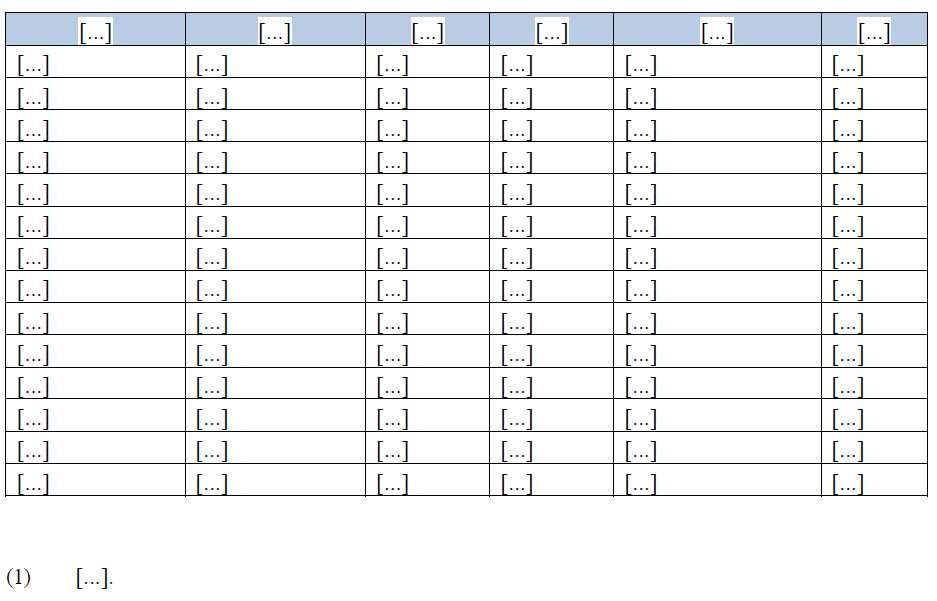

(176) Third, documents from the ordinary course of business, as for example the one shown in Figure 9 below, indicate that ESVs are typically used in larger machines rather than smaller ones.

Figure 9 – Danfoss’ steering range

[...]

Source: Doc Id 1054-43057 (Filename: M.9820-RFI020003031.pdf)

(177) As a result, fully electric solutions are even less likely to be substitutable with ESV than with HSU as fully electric machines have power limitations and weights, which make them unlikely to compete with machines currently using electrohydraulic steering. An internal document from Danfoss explains that tractors and combines [content of internal document - confidential market data].

Figure 10 – Tractors and combines electrification assessment

[...]

Source: DocID 1053-5262 (Filename M.9820-RFI020396280.pdf)

(178) [Content of internal document].

(179) The Commission therefore considers at this stage that fully electric steering solutions do not exert a competitive constraint on ESVs.

6.4.3.3. Distinction between other electrohydraulic steering solutions and the Parties’ solution

(180) The Notifying Party contends that the electrohydraulic solution offered by Ognibene and other solutions based on motors instead of ESVs are part of the same market as ESVs. The Commission finds, on the basis of its investigation, that the evidence does not corroborate this claim. However, Ognibene’s solution may exert some competitive constraint, as further discussed in the competitive assessment Section 6.4.3.3.

(181) First, from a demand-side perspective, Ognibene’s solution indeed differs from a traditional electrohydraulic solution such at the one offered by the Parties. In fact, the elect ro-hydraulic solution developed is named Digital Power Steering (‘DPS’) and includes an electric motor. The Ognibene DPS is placed over the off-highway vehicles traditional steering system, improving manoeuvrability and enabling the use of GPS and auto-guidance driving systems without any additional external steering system.

(182) The DPS is characterised by a brushless motor able to modify the steering wheel torque, providing haptic feedbacks and controlling the HSU as a function of the driving strategy (synthetic boost curves, haptics signals in case of emergency/dangerous conditions, auto-guidance features, ...).

(183) At low vehicle speed, the steering behaviour feels completely effortless; at high vehicle speed a higher “breaking” torque provided by the electric motor increases the system stability. Moreover, the electric motor is able to guarantee the steering wheel’s complete return to zero in both forward and reverse manoeuvres.

(184) Due to the differences in design, this system does not include an ESV. Although it provides a similar end use functionality and could operate as an external constraint to the Parties’ Electrohydraulic Steering, the Commission does not consider that it is substitutable with the Parties’ ESVs. As explained by one competitor: “The electrohydraulic steering valves can be integrated with other technologies (like Ognibene is doing) but they cannot be substituted by now. ” 117 In addition, ESVs is not an alternative for suppliers sourcing on a component-by-component basis, as further explained in recital (690) below.

(185) Second, from a supply-side perspective, Ognibene has developed its own solution differently from a traditional electrohydraulic solution such as the one offered by the Parties precisely because of the high barriers to entry in the ESV market due to the patents owned by Danfoss: “Given the numerous patents own by Danfoss in steering, the company had to develop an alternative design to achieve the same function in a different way. Eaton developed an electro-hydraulic steering conceptually closer to Danfoss approach but also still different to avoid Danfoss patents. ”118

(186) Finally, the Parties’ claim that Ognibene’s DPS and other similar solutions should be considered as forming part of the same market as ESVs is undermined by the fact that the Parties themselves did not provide market shares taking into account Ognibene’s DPS solution.

(187) The Commission therefore considers that the ESV and electrohydraulic solution offered by Ognibene and other solutions based on motors instead of ESVs are not part of the same product market. The extent to which these alternative solutions exert a competitive constraint on ESV will be further examined in the competition assessment in Section 8.4.3.3.

6.4.3.4. ESV mobile components for on-road and off-road applications

The Notifying Party’s view

(188) The Notifying Party explains that so-called “on-road” vehicles can refer to trucks (conventional, without a specific work function), buses, and coaches, as well as specialized on-road vehicles with specific work functions such cement mixer trucks.119

(189) The Notifying Party contends that no separate markets should be defined for, on the one hand, HPS components used in those specialized on-road vehicles, which should in fact fall under the off-road category, and, on the other hand, HPS components used in vehicles which primarily drive off-road, such as, for example, tractors, wheel loaders or excavators.120

The Commission’s past practice

(190) In Volvo/Atlas,121 the Commission defined separate market for individual mobile hydraulic components. The Commission did not further consider whether a distinction between on-road and off-road applications was warranted within the separate markets for individual mobile hydraulic components.

The Commission’s assessment

(191) Contrary to the Notifying Party’s view, the Commission preliminarily finds that ESVs for on-road vehicles with work functions are not part of the same product market as off-road vehicles.

(192) First, the Commission finds that the Parties themselves in their ordinary course of business documents only consider the supply of ESVs for the off-road market without considering steering solutions for on-road vehicles.

(193) Second, the Commission finds that there is limited demand-side substitutability. In particular, customers of ESVs for off-road vehicles do not tend to buy ESVs for on-road vehicles with work functions.

(194) Third, the Commission finds that there is limited supply-side substitutability. In particular, ESVs for on-road vehicles with work functions work with completely different technologies compared to ESVs for off-road vehicles.

(195) Fourth, the Commission further found that the market position of suppliers is significantly different in these two categories. In fact, most of the competitors supplying ESVs for on-road vehicles with work functions do not offer those for off-road vehicles and vice versa.

6.4.3.5. The market for ESV is a differentiated market

(196) The Commission considers that the market for ESV is a differentiated market.

(197) As explained in Section 6.4.3.1, ESV can be used in two different types of electrohydraulic steering systems, namely the traditional Electrohydraulic Steering, and in Steer-by-Wire. As explained in recital 0 above, a similar valve is used on both solutions, and both solutions have similar features which make them substitutable from a demand-side perspective.

(198) However, as shown in Figure 8 above, both technologies also present marginal distinctions which set them apart. In particular, Steer-By-Wire solutions offer more design flexibility, eliminate hydraulic noise, and are easier to install. In Steer-by-Wire solutions, the steering column is eliminated, and HPS can be entirely removed from the cab and mounted strategically at another place of the vehicle in order to reduce cab noise and improve operator comfort.

(199) The two technologies also differ in terms of pricing. According to the Notifying Party’s own estimates, the cost of traditional Electrohydraulic Steering is estimated at EUR [...], whereas the price of Steer-By-Wire is estimated at EUR [...], i.e. a [...]% difference. 122

(200) As a result, the Commission considers that the market for ESV is differentiated in relation to the end use of valves either in a traditional Electrohydraulic Steering or in a Steer By Wire, and will consider the impact of this conclusion in the competitive assessment in Section 8.3.3.1.

6.4.3.6. Conclusion on the product market definition for ESVs

(201) In the light of the considerations in Sections 6.4.3.2 to 6.4.3.5 and taking account of the results of the market investigation and of all the evidence available to it, the Commission considers that there is a market for ESVs for off-road applications separate from on-road, differentiated by type of solution in relation to the end use of valves (traditional Electrohydraulic Steering or Steer By Wire), which do not include captive sales, and is separate from the markets for electrohydraulic steering solutions based on motors and electric steering.

6.5. Orbital motors

6.5.1. The Commission’s past practice

(202) The Commission’s previous decisions do not deal specifically with orbital motors, or, more broadly, with hydraulic motors for mobile applications.

(203) In Bosch/Rexroth, consistent with the parties’ view123, the Commission considered that piston pumps, vane pumps and gear pumps for industrial applications are not substitutable and therefore form different product markets.124 However, substitutability of different motor technologies was not assessed.

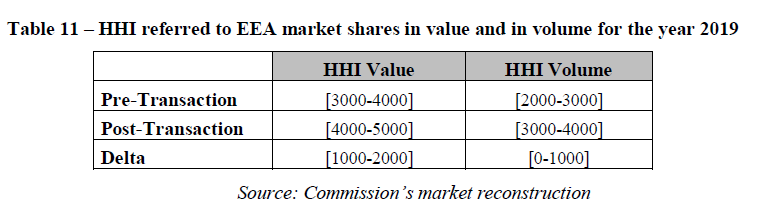

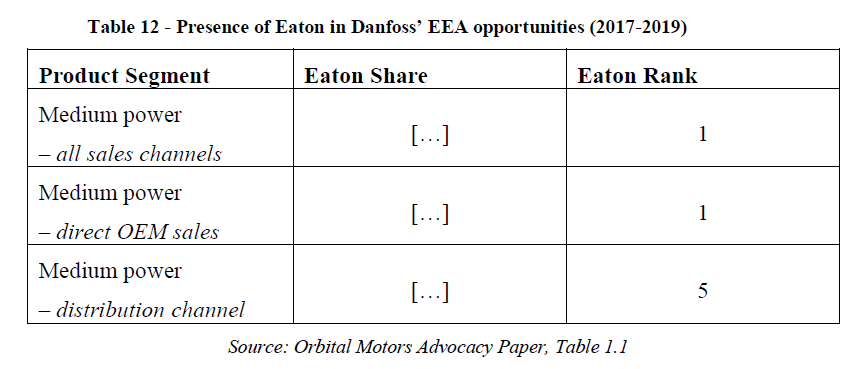

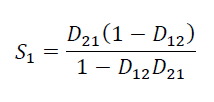

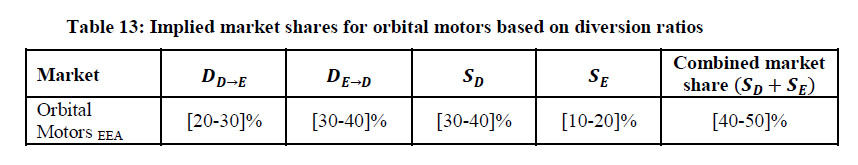

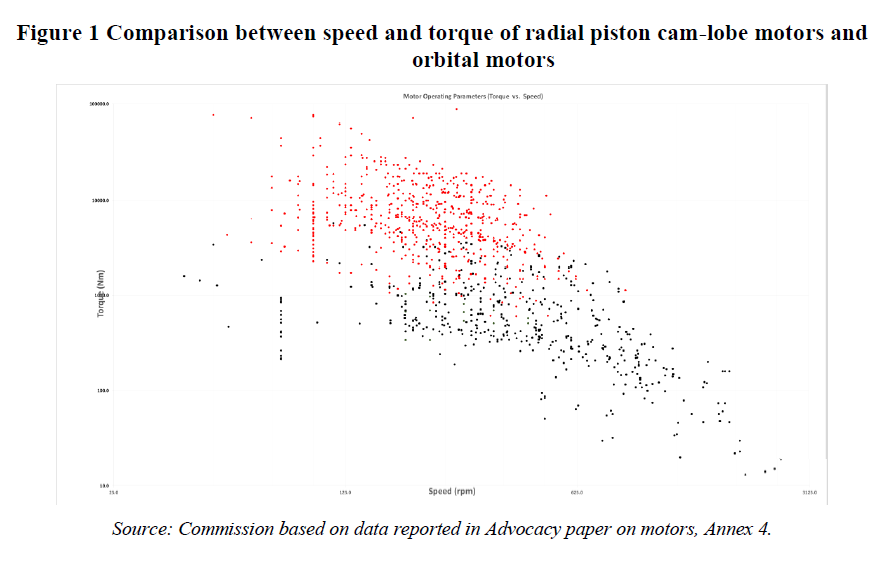

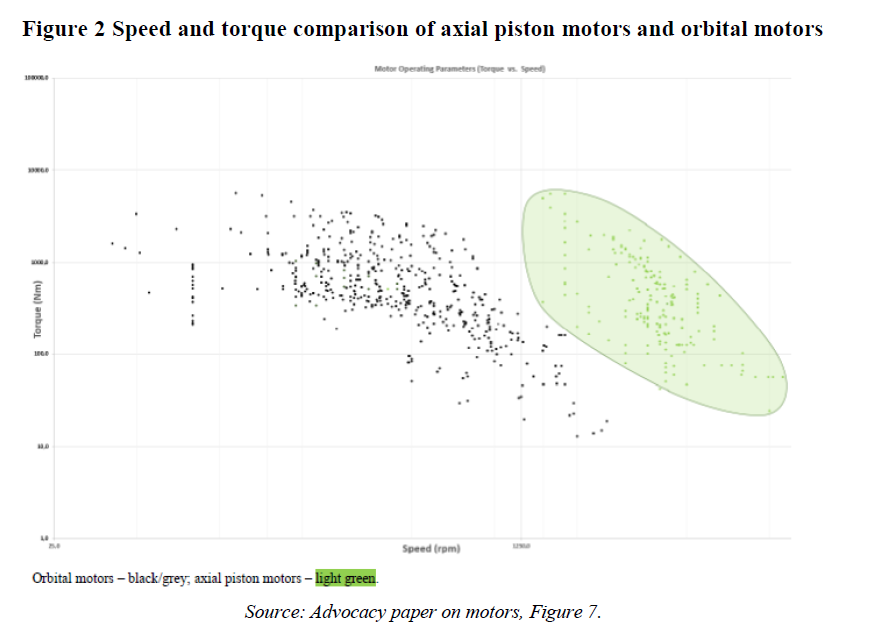

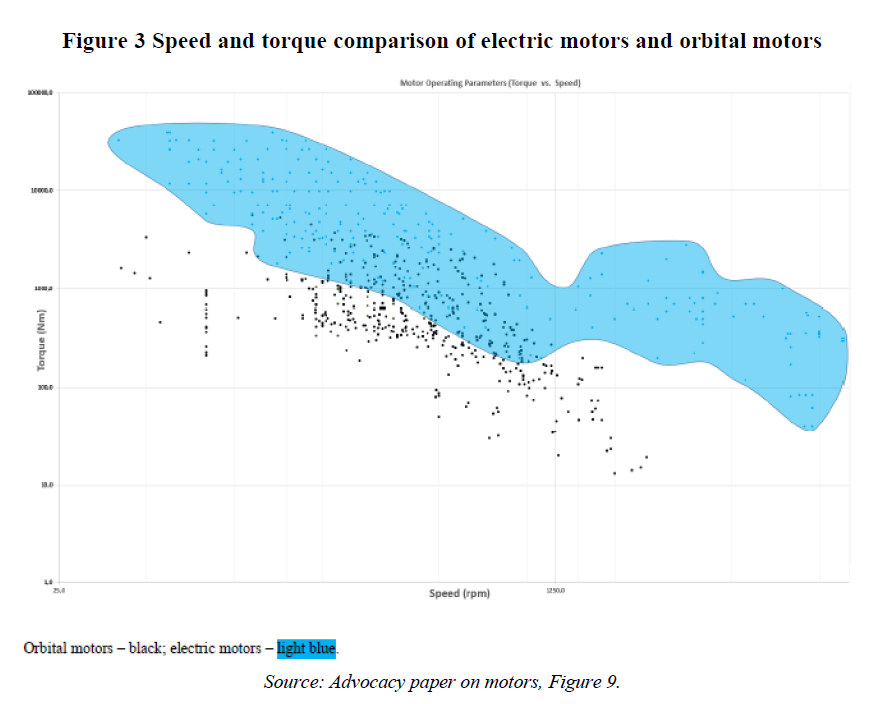

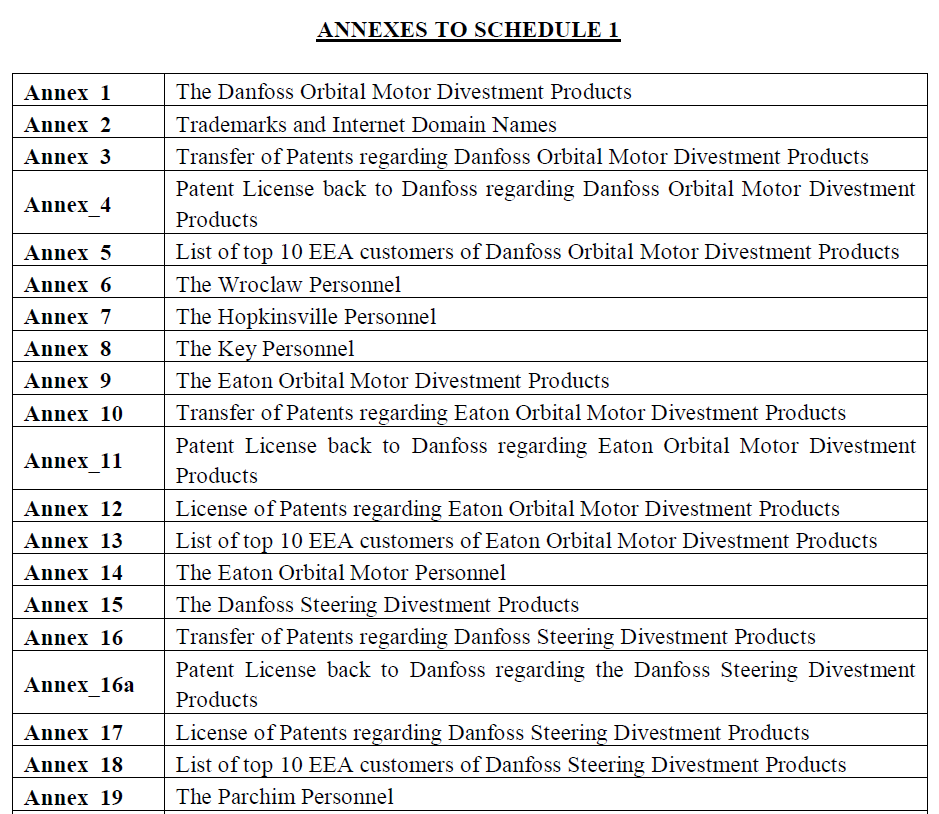

6.5.2. The Notifying Party’s view