GC, 5th chamber, March 26, 2025, No T-441/21

GENERAL COURT

Judgment

Annuls

PARTIES

Demandeur :

UBS Group, UBS, Natixis, UniCredit, UniCredit Bank, Nomura International, Nomura Holdings, Bank of America, Bank of America Corporation, Portigon

Défendeur :

European Commission

COMPOSITION DE LA JURIDICTION

President :

S. Papasavvas

Judge :

J. Svenningsen (Rapporteur), C. Mac Eochaidh, J. Martín y Pérez de Nanclares, M. Stancu

Advocate :

I. Ioannidis, C. Riis-Madsen, J. Stratford, E. Neill, J.-J. Lemonnier, L. Ghebali, I. Vandenborre, M. Siragusa, S. Dionnet, G. Rizza, B. Massella Ducci Teri, M. Lesaffre, T. Selwyn Sharpe, I. Antoniou, W. Howard, M. Demetriou, C. Thomas, D. Bailey, D. Gregory, J. Turner KC, D. Liddell, D. Slater, S. Whitfield, M. García, H.‑J. Niemeyer, M. Röhrig, C. Dankerl

JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Fifth Chamber, Extended Composition)

1 By their action in Case T‑441/21, brought under Article 263 TFEU, the applicants UBS Group AG and UBS AG (together, ‘UBS’) seek (i) annulment of Commission Decision C(2021) 3489 final of 20 May 2021 relating to a proceeding under Article 101 TFEU and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement (Case AT.40324 – European Government Bonds) (‘the contested decision’), and (ii) a reduction of the amount of the fine imposed on them in that decision.

2 By its action in Case T‑449/21, brought under Article 263 TFEU, Natixis seeks annulment of the contested decision in so far as that decision concerns it.

3 By their action in Case T‑453/21, brought under Article 263 TFEU, UniCredit SpA and UniCredit Bank AG (together, ‘UniCredit’), seek (i) annulment of the contested decision in so far as it concerns them, and (ii) a reduction of the amount of the fine which has been imposed on them in that decision.

4 By their action in Case T‑455/21, brought under Article 263 TFEU, Nomura International plc and Nomura Holdings, Inc. (together, ‘Nomura’), seek (i) annulment of the contested decision in so far as it concerns them, and (ii) a reduction of the amount of the fine imposed on them in that decision.

5 By their action in Case T‑456/21, brought under Article 263 TFEU, Bank of America N.A. and Bank of America Corporation (together, ‘BofA’) seek annulment of the contested decision in so far as it concerns them.

6 By its action in Case T‑462/21, brought under Article 263 TFEU, Portigon AG, formerly WestLB AG, seeks annulment of the contested decision in so far as that decision concerns it.

I. Background to the dispute

A. The EGB sector

7 The conduct at issue relates to European Government Bonds (‘EGBs’), that is to say, sovereign bonds denominated in euros and issued by the central governments of the Eurozone Member States. EGBs are debt securities allowing European governments to raise cash to fund certain expenditures or certain investments, and in particular to refinance existing debt.

8 A Member State (the issuer) may thus issue a bond to borrow money (the notional amount) from an investor (the holder) for a fixed term which may be short (for example, 2 years) or long (for example, 10 or 30 years) and at a predefined fixed or floating rate of interest. The bondholder receives the interest (the coupon) from the issuer at regular intervals, as well as the repayment of the notional amount at the agreed maturity.

9 EGBs are offered for sale for the first time by, or on behalf of, their issuer on the primary market, and are subsequently traded on the secondary market.

10 The functioning of those markets, described in recitals 3 to 51 of the contested decision, is briefly set out below for the purposes of the present judgment.

1. Issuance on the primary market

11 EGBs are issued by central governments on the primary market. That issue is often delegated to a debt management office, which defines the procedure for issuing those bonds. The latter procedure generally takes the form either of an auction, which is a tendering process, or of a syndication, which is a private placement process involving a more limited group of operators.

12 The bonds may be obtained, in either of the aforementioned forms, only by financial institutions with the status of primary dealers. Those dealers compete on the primary market to acquire EGBs. After acquiring the EGBs, the dealers may keep them or resell them on the secondary market to other financial institutions or investors.

13 In an auction, primary dealers submit a bid.

14 Primary dealers are subject to various obligations. First, they are obliged, to a certain extent, to take part in the auctions and to acquire and place a significant volume of EGBs on the secondary market during a given reference period. Second, they are generally expected to take on a role as market maker on the secondary market by quoting two-way prices – namely bid prices and ask prices – and by trading at those prices generally and continuously rather than transaction by transaction. The debt management offices exert some pressure on the primary dealers by ranking them, in particular on the basis of the volumes of EGBs that they place and of their participation in auctions. A high ranking may bring with it, inter alia, privileged access to syndications and associated derivatives orders.

15 The price at which primary dealers decide to bid at auctions depends on the benchmark price; this is the price at which similar bonds are quoted on the secondary market. If the auction concerns a new tranche (tap) of an existing bond – namely a new supply of EGBs which have previously been issued, with the same original maturity, the same notional amount and the same coupon but sold at the current price – the price information is readily available, since the EGBs concerned are already quoted on the secondary market.

16 Within that framework, the price of the bonds is generally set as a percentage of the notional amount, and that percentage is generally expressed by reference to its first two decimal places only.

17 In that context, bids made on the primary market by primary dealers in respect of those bonds are often made above the prevailing mid-price – or ‘mid’ – of that bond on the secondary market. The mid-price is the mid-point between the prevailing bid and ask prices on the secondary market and is expressed in cents (namely, to two decimal places). The latter two types of prices are those at which traders on the secondary market are ready respectively to buy or sell the relevant EGBs. The bid made by primary dealers therefore involves a spread around the mid-price.

18 When the bidding window is closed, the debt management office of the issuing Member State publishes the auction results and allocates volumes of EGBs to the primary dealers, starting with the highest bidders. The latter bidders generally obtain EGBs for the entirety of the volume that they offered to buy.

19 In practice, the level of the bid made by primary dealers will depend on their assessment of the market conditions and the need to win a significant share of the EGB issue in question. Thus, a given primary dealer could place a bid that is higher than the mid-price – known as overbidding – or place a bid that is closer to the mid-price, which is sometimes called a flat bid. Overbidding could, initially, lead to a financial loss on the EGBs acquired when these were issued (since the primary dealer would not be able to re-sell them at the same price on the secondary market); however, the primary dealer can then expect to be able to offset that loss subsequently, on account of its status (which gives access to syndications and other advantages) and its later trading activity on the secondary market.

20 In a syndication, the debt management office instructs a group of primary dealers (the lead managers) to assist it in placing a new EGB on the market or in tapping an existing EGB. Those lead managers commit to purchasing the bulk of the EGBs issued and to sell them to investors on the secondary market. Syndication is less common than an auction, but it is generally larger in volume and longer in duration. Syndication is often used by the Member States in order to introduce large volumes of new EGBs.

21 Involvement in syndications offers, for primary dealers selected as lead managers, advantages in terms of reputation but also because those lead managers are remunerated by means of underwriting fees. That selection is made on the basis, inter alia, of their ranking, which is based on their results in the auctions in which they have participated (those results being related to the volumes of EGBs acquired and the prices offered to the issuer). Thus, the prospect of being able to participate in syndication is one of the elements driving the competitive bids of those primary dealers at the auctions (see paragraph 19 above).

22 The lead managers assist the debt management offices in pricing EGBs for issuance on the basis of a benchmark bond on the secondary market. To that end, they may receive information from their internal EGB trading desks.

23 The lead managers must, however, maintain strict confidentiality vis-à-vis their internal desks on account of the involvement of the latter in secondary market trading. Thus syndications are, as a matter of principle, the responsibility of a team that is separate from the internal EGB trading desk of the lead manager bank.

2. Trading on the secondary market

24 Unless they decide to hold them until maturity, primary dealers offer EGBs, acquired on the primary market, for sale on the secondary market, in order to trade them either with other banks that may or may not have primary dealer status (known as ‘D2D’ trades), or with other investors (known as ‘D2C’ trades). The EGBs are used for investment or hedging purposes or as a benchmark for determining the price of other assets. Trading takes place ‘over the counter’, namely without a central exchange, electronically or via brokers.

(a) Price formation of EGBs on the secondary market

25 The value of an EGB on the secondary market depends on its yield to maturity – which is expressed as an annual percentage of its notional amount – on the fixed coupon and on the gains or losses from trading the bond. The price at which the EGB is traded varies according to a range of factors, such as changes in the economic environment (for example, the general interest rate evolution in the markets or inflation expectations) or issuer-specific factors (for example, the perceived risk, liquidity, or the availability of newer issues). Thus, there is an inverse relationship between the yield and the price of an EGB: a lower yield is translated in a price increase and a higher yield in a price decrease.

26 In that context, a ‘yield curve’ is often used to represent the expected yield of EGBs depending on their time to maturity. Such a curve thus indirectly reflects the price of EGBs on the financial markets, taking into account investor expectations in terms of inflation developments, interest rates and general risk (economic environment and financial health of the issuer).

(b) Participants on the secondary market

27 As is apparent from recitals 11 and 40 of the contested decision and footnote 10 thereto, primary dealers are generally expected to take on the role of market maker on the secondary market, quoting two-way prices for bonds as described in paragraph 14 above.

28 When banks act on the secondary market, they seek to generate revenue by capturing the difference between the bid price and the ask price. The difference between those two prices is known as the ‘spread’ and constitutes the bank’s revenue on a combined buy and sell transaction.

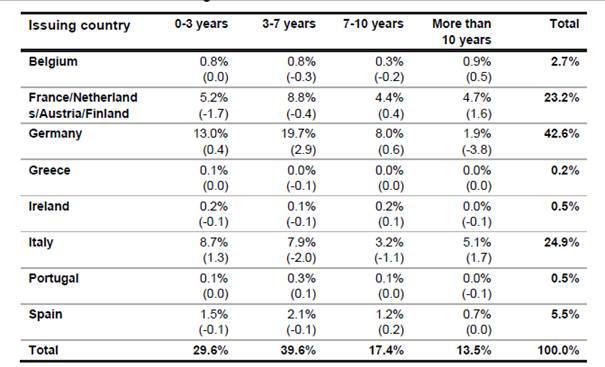

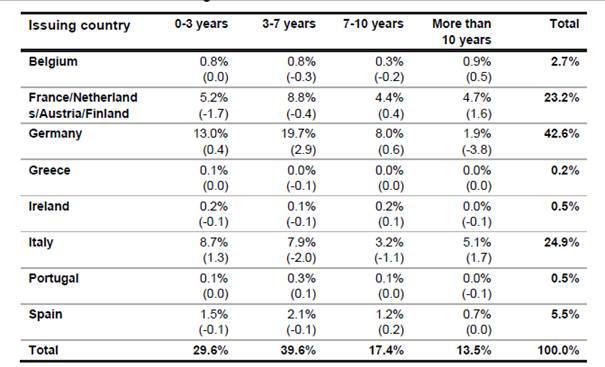

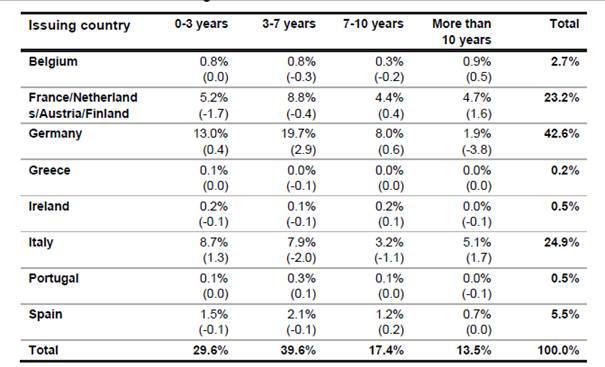

29 In managing their portfolios, traders may adopt long or short trading positions. Where traders take a long position on a bond, they hold or purchase bonds before reselling them, thereby speculating on foreseen gains if the value of the bond rises; in other words, the traders expect the price of bonds to increase, which will increase the value of the bonds that they hold. Where traders take a short position, they sell bonds that they do not own. They will have to purchase them at a later date and are speculating that the price of the bonds will fall, so that they can be bought at a lower price than that at which the traders have sold them.

30 In the same context of portfolio management, traders are also led to engage in hedging, which is intended, in particular, to offset a long position by selling bonds, and a short position by buying bonds.

B. The administrative procedure which gave rise to the contested decision

31 Further to an application of 29 July 2015, on 27 January 2016 the European Commission granted The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc and The Royal Bank of Scotland plc (together, ‘RBS’) – which subsequently became NatWest Group plc and NatWest Markets Plc, respectively (together, ‘NatWest’) – conditional immunity from fines pursuant to point 8(a) of the Commission Notice on Immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases (OJ 2006 C 298, p. 17; ‘the Leniency Notice’).

32 On 29 June and 30 September 2016, UBS and Natixis respectively applied for a reduction of the fine, pursuant to point 23 of the Leniency Notice.

33 On various occasions, in accordance with Article 18(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles [101 and 102 TFEU] (OJ 2003 L 1, p. 1), or with point 12 of the Leniency Notice, the Commission sent requests for information to the addressees of the contested decision and to other banks.

34 On 31 January 2019, the Commission (i) initiated proceedings with a view to adopting a decision pursuant to Chapter III of Regulation No 1/2003, in accordance with Article 2(1) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 773/2004 of 7 April 2004 relating to the conduct of proceedings by the Commission pursuant to Articles [101 and 102 TFEU] (OJ 2004 L 123, p. 18), and (ii) issued a Statement of Objections to, inter alia, UBS, Natixis, UniCredit, Nomura, BofA, Portigon – which had succeeded WestLB – and NatWest (‘the Statement of Objections’). On that occasion, the Commission also informed UBS and Natixis that they were not eligible for immunity from fines, but that they were the second and third banks, respectively, to produce evidence of the suspected infringement and that, a priori, they could be eligible for a reduction of the fines that might be imposed on them, should that event arise.

35 All of the banks to which the Statement of Objections was addressed were granted access to the Commission’s investigation file. In accordance with Article 10(2) of Regulation No 773/2004, all submitted written observations on that statement. Pursuant to Article 12(1) of that regulation, they also presented their arguments at a hearing which took place from 22 to 24 October 2019.

36 On 6 November 2020, the Commission sent each of the banks to which the Statement of Objections had been addressed, and on which fines could potentially be imposed, a letter (the ‘Letter on Fines’) providing further clarification of the fining methodology proposed by that institution in order to determine the proxy for the value of sales (‘the proxy’). That methodology was accompanied by underlying data and the intended amount of the proxy, for each of the addressees concerned, resulting from the application of that methodology. UBS submitted observations in response on 18 December 2020, UniCredit on 24 November 2020 and 8 January 2021, Nomura on 24 November 2020 and 8 January 2021, and Portigon on 15 January 2021.

37 On 12 November 2020, the Commission sent the addressees of the Statement of Objections a letter containing a statement of facts, inviting them to give their views on the factual additions and corrections set out in that statement and relating to elements contained in the Statement of Objections (‘the Letter of Facts’). To that end, those addressees were once again granted access to the Commission’s investigation file. Most of those addressees submitted observations between 8 December 2020 and 8 January 2021.

38 On 20 May 2021, the Commission adopted the contested decision on the basis of Articles 7 and 23 of Regulation No 1/2003.

C. The contested decision

1. The finding of the infringement at issue

39 In the contested decision, the Commission referred to over 380 discussions between the traders of the banks concerned, via persistent chatrooms – namely, essentially, two chatrooms named ‘DBAC’ and ‘CODS & CHIPS’ – and via bilateral communications, by telephone or instant messaging, over a period between 3 January 2007 and 28 March 2012.

40 According to the Commission, those discussions involved exchanges of commercially sensitive information which allowed the banks concerned to be informed about each other’s conduct and strategies, and, in that way, may have allowed them to adjust or otherwise coordinate their conduct and gain competitive advantages when EGBs were issued, placed on the market and traded (see recitals 94 and 95 of the contested decision).

41 In that context, the Commission considered that the overall aim of the collaboration between the traders was to help each other in their operation on the market, by reducing uncertainties regarding the issuing and/or trading of EGBs, with the general purpose of increasing the revenues earned on both the primary and secondary markets and resulting from the participation of the banks concerned in EGB issues and subsequent trading thereof. In doing so, those banks knowingly substituted practical cooperation between them for the risks of the market, to the detriment of other market participants, their customers or debt management offices.

42 According to the Commission, the discussions at issue can, for analytical purposes, be grouped into four categories of conduct which are intertwined and partially overlap (see recitals 93 and 95, together with Section 5.1.3.2 of the contested decision).

43 Those four categories of conduct consist, respectively, in:

– first, attempts to influence the prevailing market price on the secondary market in function of the conduct on the primary market (‘Category 1’);

– second, attempts to coordinate the bidding on the primary market (‘Category 2’);

– third, attempts to coordinate the level of overbidding on the primary market (‘Category 3’);

– fourth, other exchanges of sensitive information, including exchanges relating, in the first place, to pricing elements, positions and/or volumes and strategies for specific counterparties related to individual trades of EGBs on the secondary market (‘Category 4(i)’); in the second place, individual recommendations given to a debt management office (‘Category 4(ii)’) and, in the third place, the timing of pricing of syndicates (‘Category 4(iii)’) (together, ‘Category 4’).

44 As regards the legal classification of the conduct at issue, the Commission found that this formed part of a single and continuous infringement consisting in agreements and/or concerted practices which had as their object the restriction and/or distortion of competition in the EGB sector within the European Economic Area (EEA).

45 In order to arrive at that finding, in the first place, the Commission considered that the conduct at issue constituted a single and continuous infringement having regard, in particular, to the content of the discussions, the methods employed, the systematic nature of some of that conduct and the participants involved. In particular, that conduct formed part of a common plan, since a stable group of individuals was involved in the cartel, the means of communication used were generally the same for the different practices, and the discussions were frequent, took place over the same period and covered the same or overlapping topics (see recitals 412 to 421 of the contested decision).

46 In the second place, the Commission considered that the object of the single and continuous infringement at issue was to restrict and/or distort competition through the sharing of commercially sensitive information between members of a circle of competitors with the aim of coordinating their strategies for acquiring EGBs on the primary market and/or trading those bonds on the secondary market. That conduct was capable of impacting the normal course of pricing components for EGBs (see recital 495 of the contested decision).

47 In the third place, the Commission found that, having regard, in particular, to the fact that the conduct at issue had occurred from trading desks situated in the European Union and EEA, that conduct had been implemented in the EEA and had substantial, immediate and foreseeable effects on competition in the EEA. Accordingly, that conduct was capable of having an appreciable effect on trade between Member States and Contracting Parties to the EEA Agreement, with the result that the Commission had jurisdiction to apply both Article 101 TFEU and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement (see recitals 725 and 726 of the contested decision).

48 In the fourth place, the Commission considered, given, in particular, that the conduct at issue constituted a restriction by object, that none of the conditions under Article 101(3) TFEU and Article 53(3) of the EEA Agreement was satisfied in the present case (see recitals 728 and 731 of the contested decision).

2. The imposition of fines

49 As regards the imposition of a fine on the banks concerned in respect of their participation in the infringement at issue, in the first place, the Commission stated that, pursuant to Article 25 of Regulation No 1/2003, its power to impose a fine was time-barred in so far as concerns BofA and Natixis, on account of the fact that their respective involvement had ended more than five years before the start of the investigation (see recital 778 of the contested decision).

50 Pursuant to the final sentence of Article 7(1) of Regulation No 1/2003, the Commission nevertheless found the infringement at issue against those two banks (see recitals 780 to 784 of the contested decision).

51 In the second place, as regards the other banks concerned – that is, UBS, UniCredit, Nomura, Portigon and NatWest – the Commission stated that it had determined the amount of the fines in accordance with the Guidelines on the method of setting fines imposed pursuant to Article 23(2)(a) of Regulation No 1/2003 (OJ 2006 C 210, p. 2; ‘the Guidelines’) (see recital 807 of the contested decision). However, taking into account the particularities of the financial sector and, in particular, the fact that financial products such as EGBs did not generate sales in the usual sense, the Commission, rather than using a ‘value of sales’ linked to the issue and trading of EGBs, deemed it appropriate to determine a proxy. The latter was based on, first, the notional amount of EGBs traded on the secondary market by the banks concerned over the course of their respective periods of participation in the infringement at issue and, second, the bid-ask spread of 32 representative categories of EGB (see recitals 813 to 832 of the contested decision).

52 As to the remainder, the Commission calculated the amount of the fine for each of the banks referred to in the preceding paragraph by establishing, as is provided in the Guidelines, a basic amount, determined having regard, in particular, to the gravity and duration of the infringement, and by adjusting the basic amount in the light of considerations such as any aggravating or mitigating circumstances, the maximum legal threshold for the fine or rules stemming from the Leniency Notice.

53 In that connection, first, the amount of the fine imposed on Portigon was capped at EUR 0, pursuant to the maximum threshold of 10% of total turnover during the preceding business year (as provided under Article 23(2) of Regulation No 1/2003 and point 32 of the Guidelines), having regard to the fact that that bank was gradually ceasing its activities and that Portigon’s net turnover in 2020 was negative (see recital 893 of the contested decision). Second, pursuant to the Leniency Notice, the Commission granted immunity from fines to NatWest and a reduction of 45% of the amount of the fine imposed on UBS, in respect of their respective cooperation in the investigation (see recitals 895 to 903 of the contested decision).

3. The operative part

54 The operative part of the contested decision reads as follows:

‘Article 1

The following undertakings have infringed Article 101 of the Treaty and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement by participating, during the periods indicated, in a single and continuous infringement regarding EGB covering the entire EEA, which consisted of agreements and/or concerted practices that had the object of restricting and/or distorting competition in the EGB sector:

– [BofA] participated from 29 January 2007 until 6 November 2008, with respect to the CODS & CHIPS chatroom;

– [Natixis] participated from 26 February 2008 until 6 August 2009;

– [NatWest] participated from 4 January 2007 until 28 November 2011 and NatWest Markets NV participated from 17 October 2007 until 28 November 2011;

– [Nomura] participated from 18 January 2011 until 28 November 2011;

– [Portigon] participated from 19 October 2009 until 3 June 2011;

– [UBS] participated from 4 January 2007 until 28 November 2011;

– [UniCredit] participated from 9 September 2011 until 28 November 2011;

Article 2

For the infringement(s) referred to in Article 1, the following fines are imposed:

– [NatWest] and NatWest Markets NV jointly and severally liable: EUR 0

– [Nomura]: EUR 129 573 000

– [Portigon]: EUR 0

– [UBS]: EUR 172 378 000

– [UniCredit]: EUR 69 442 000

…

Article 3

The undertakings listed in Article 1 shall immediately bring to an end the infringements referred to in that Article insofar as they have not already done so.

They shall refrain from repeating any act or conduct described in Article 1, and from any act or conduct having the same or similar object or effect.

…’

II. Forms of order sought

55 In Case T‑441/21, UBS claims that the Court should:

– principally, annul the contested decision;

– in the alternative, reduce the amount of the fine imposed on it to EUR 51.3 million in accordance with the methodology based on UBS’ ‘net value traded’ methodology; or reduce that amount to EUR 60.6 million in accordance with UBS’ ‘adjusted net value traded’ methodology; or reduce that amount by at least 65% as a consequence of the errors and inaccuracies identified in the Commission’s methodology; and

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

56 In Case T‑449/21, Natixis claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision in so far as it concerns Natixis;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

57 In Case T‑453/21, UniCredit claims that the Court should:

– annul Articles 1 and/or 2 of the contested decision in so far as they concern UniCredit;

– in the alternative, reduce substantially the amount of the fine imposed on it;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

58 In Case T‑455/21, Nomura claims that the Court should:

– annul Article 1, fourth indent, of the contested decision;

– in the alternative, annul Article 2, second indent, of the contested decision;

– in the further alternative, reduce substantially the amount of the fine imposed on Nomura;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

59 In Case T‑456/21, BofA claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision in so far as it concerns BofA;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

60 In Case T‑462/21, Portigon claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision in so far as it concerns Portigon;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

61 In Cases T‑441/21, T‑449/21, T‑453/21, T‑455/21, T‑456/21 and T‑462/21, the Commission contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action in its entirety;

– order the applicants to pay the costs.

III. Law

62 After hearing the parties, the Court has decided to join Cases T‑441/21, T‑449/21, T‑453/21, T‑455/21, T‑456/21 and T‑462/21 for the purposes of the present judgment, in accordance with Article 68(1) of its Rules of Procedure.

A. The applications for the omission of certain data vis-à-vis the public

63 In the course of the proceedings before the Court, UniCredit, Nomura, BofA and the Commission requested, in essence, that certain data be omitted vis-à-vis the public in the present judgment, pursuant to Articles 66 and 66a of the Rules of Procedure.

64 In that regard, UniCredit stated that no information contained in the procedural documents which it filed in connection with its action is secret or confidential and thus should be omitted in the text of the judgment to be delivered, with the exception of the name of its trader and several literal citations from the leniency statements of UBS and RBS.

65 Nomura stated that the names of, and information that might make it possible to identify, the traders involved in the infringement at issue, the experts who have assisted it in connection with its action and in the administrative procedure which led to the contested decision as well as the companies employing those experts, and certain bond issuers should be omitted from the text of the judgment to be delivered.

66 Lastly, BofA stated that (i) the names of, and information that might make it possible to identify, its employees or former employees; (ii) the content of the discussions that took place in the chat rooms, of the leniency statements and of the replies to the Commission’s requests for information; (iii) the source references for the elements referred to in (ii); (iv) quotations from the leniency applicants’ oral statements; (v) strong language or derogatory comments by its traders in relation to third parties; and (vi) references to conduct that took place outside of the infringement period should be omitted from the text of the judgment to be delivered.

67 The Commission also proposed that the names of the traders involved in the conduct complained of be anonymised.

68 In that regard, it should be recalled that, in reconciling the need to make judicial decisions public, on the one hand, and the right to protection of personal data and of business secrets, on the other, the court must seek, in the circumstances of each case, to find a fair balance, having regard also to the public’s right of access, in accordance with the principles set out in Article 15 TFEU, to judicial decisions (see judgment of 27 April 2022, Sieć Badawcza Łukasiewicz – Port Polski Ośrodek Rozwoju Technologii v Commission, T‑4/20, EU:T:2022:242, paragraph 29 and the case-law cited).

69 Furthermore, the confidential treatment of an item of information is not justified in the case, for example, of information which is already public or to which the general public or certain specialist circles have access, information featuring also in other passages or documents in the case file in respect of which the party seeking to preserve the confidential nature of the information in question neglected to make a request to that effect, information which is not sufficiently specific or precise to reveal confidential data, or information which is largely apparent or may be deduced from other information which is legitimately available to the interested parties (see order of 14 March 2022, Bulgarian Energy Holding and Others v Commission, T‑136/19, EU:T:2022:149, paragraph 9 and the case-law cited).

70 In addition, information which was secret or confidential, but which is at least five years old, must, as a rule, on account of the passage of time be considered historical and therefore as having lost its secret or confidential nature unless, exceptionally, the party relying on that nature shows that, despite its age, that information still constitutes an essential element of its commercial position or of that of interested third parties (see judgment of 19 June 2018, Baumeister, C‑15/16, EU:C:2018:464, paragraph 54 and the case-law cited).

71 In the light of the foregoing, the Court has decided, in the present case, as regards the public version of the present judgment, to anonymise only the names of the natural persons referred to in the contested decision and the names of the experts used by the banks concerned as well as of the companies which employ them.

72 First, there is no need to treat as confidential the figures used by the Commission in calculating the amount of the fines imposed on UBS, UniCredit and Nomura, in view of (i) the fact that no application to that effect has been made by those banks; (ii) the fact that all of those figures will be more than 13 years old as at the date of delivery of the present judgment; (iii) the fact that those figures are mainly relative or estimated figures and have already been sent to all the banks concerned, as evidenced by the versions of the contested decision notified to those banks; and (iv) the need to ensure that the reasoning of the present judgment is comprehensible, especially where some banks are claiming that the Commission made errors of calculation, the examination of which naturally requires reference to the figures used by the Commission.

73 Second, there is no reason to redact the content of the discussions at issue, even if they might disclose strong language or derogatory comments by the traders of the banks concerned, particularly in relation to third parties.

74 First of all, as is apparent from the contested decision, those discussions constitute almost all of the evidence on which that decision is based and the messages exchanged in the context of those discussions reveal, according to the Commission, the anticompetitive nature of the conduct of the banks concerned.

75 Next, almost all of the messages contained in the discussions at issue appear in the public version of the contested decision and do not, therefore, warrant any protection. The same applies to the names of the bond issuers which Nomura seeks to have omitted.

76 Lastly, as regards the excerpts from discussions not referred to in the contested decision but which the Court will make use of in the present judgment, their reference is justified by the requirement to provide an intelligible response to the arguments raised by the applicants and, in particular, by BofA.

77 It is also that requirement which substantiates the Court’s finding that there is no need to treat as confidential the excerpts from documents – including the leniency documents – contained in its case file and which it considers necessary to mention when examining the arguments raised by BofA.

78 Third, as regards the references to the sources of the evidence used by the Commission and referred to in the contested decision and the conduct of BofA that is unrelated to the infringement at issue, suffice it to state that they will not be used in the present judgment.

B. The object of the infringement found in the contested decision

79 The pleas raised by several applicants alleging errors in the characterisation of the conduct at issue as a ‘single and continuous infringement’ and an ‘infringement by object’ as well as the Commission’s defences reveal a difference in understanding of the object of the infringement found in the contested decision.

80 On the one hand, certain applicants understand, in essence, that, by Article 1 of the contested decision, the Commission found a single and continuous infringement composed of multiple separate infringements.

81 In that regard, UniCredit suggests, inter alia in its fourth plea, that the Commission found a single and continuous infringement composed of two single and continuous infringements, the first relating to the primary market for EGBs and the second relating to the secondary market for EGBs.

82 Similarly, in maintaining, in the case of Nomura, that the Commission erred in placing certain of the discussions at issue in one or more of the categories referred to in recitals 93, 382 and 496 of the contested decision (second plea) or, in the case of Portigon, that the discussions referred to in Category 4 could not be regarded as having an anticompetitive object, unlike those in Categories 1 to 3 (first part of its fifth plea), those banks suggest that the Commission found a single and continuous infringement itself composed of four single and continuous infringements, which correspond to each of those Categories 1 to 4 and which should therefore be examined separately.

83 On the other hand, the Commission disputes those readings of the contested decision and maintains that the banks concerned participated in one single and continuous infringement; according to the Commission, whether that infringement reveals a sufficient degree of harm to competition should be assessed ‘overall’ in order to determine whether it can be regarded as having an anticompetitive object, and not category by category or even discussion by discussion.

84 It should be noted that the exact determination of the scope and number of infringements found in the contested decision is essential in order to assess the legality of that decision. It is also essential in order to determine the effectiveness of certain arguments raised by the applicants, in particular those alleging errors in the classification of certain forms of conduct in one or other of the categories referred to in recitals 93, 382 and 496 of the contested decision, errors in the characterisation of a single and continuous infringement and in the participation of the banks concerned in the infringement at issue, and errors in the characterisation of the conduct at issue as a ‘restriction by object’.

85 In that regard, the Court of Justice has held that, while a complex of practices may be characterised as a ‘single and continuous infringement’, it cannot be inferred from that that each of those forms of conduct must, in itself and taken in isolation, necessarily be characterised as a separate infringement. That can be the case only if, in the decision concerned, the Commission has chosen to identify and characterise as such each of those forms of conduct and then to provide evidence of the involvement of the undertaking concerned to which they are attributed (see, to that effect, judgment of 16 June 2022, Sony Corporation and Sony Electronics v Commission, C‑697/19 P, EU:C:2022:478, paragraph 67).

86 Moreover, in interpreting the decision concerned, the General Court must take care not to confuse the concept of ‘conduct’ with that of ‘infringement’, otherwise it would err in law (see, to that effect, judgment of 16 June 2022, Sony Corporation and Sony Electronics v Commission, C‑697/19 P, EU:C:2022:478, paragraph 78).

87 In the present case, it is therefore necessary to determine whether, in the contested decision, the Commission found that there was only one single and continuous infringement with an anticompetitive object or, on the contrary and as UniCredit, Nomura and Portigon suggest, that there was a single and continuous infringement, composed of two or four additional, separate and independent single and continuous infringements, each with an anticompetitive object.

88 In that regard, there is no doubt that, in the contested decision, the Commission criticises the banks concerned for their participation in only one single and continuous infringement, and that any other interpretation results from a misreading of the contested decision.

89 First, Article 1 of the contested decision merely finds that the banks concerned ‘have infringed Article 101 of the Treaty and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement by participating, during the periods indicated, in a single and continuous infringement regarding EGB covering the entire EEA, which consisted of agreements and/or concerted practices that had the object of restricting and/or distorting competition in the EGB sector’.

90 Thus, unlike Article 1 of the decision at issue in the case giving rise to the judgment of 16 June 2022, Sony Corporation and Sony Electronics v Commission (C‑697/19 P, EU:C:2022:478), which referred to a single and continuous infringement composed of several separate infringements, Article 1 of the contested decision makes no reference to any other infringement which may correspond to the forms of conduct identified in the four categories of conduct referred to in recitals 93, 382 and 496 of that decision and mentioned in paragraphs 42 and 43 above.

91 Second, that reading of the wording of Article 1 of the contested decision is confirmed by the statement of reasons for that decision, in the light of which its operative part must be interpreted, should the need arise (judgment of 15 May 1997, TWD v Commission, C‑355/95 P, EU:C:1997:241, paragraph 21).

92 First of all, in recitals 424, 469, 484, 737, 781 and 841 of the contested decision, the Commission repeatedly uses the singular to refer to the infringement in which it considers that the banks concerned participated.

93 Next, the structure of the contested decision highlights the fact that the Commission first explained the reasons why approximately 380 discussions formed a single and continuous infringement (Section 5.1.2) and then stated the reasons why that single infringement had an anticompetitive object (Section 5.1.3).

94 Lastly, in recitals 93, 382, 496, 516, 549 and 550 of the contested decision, the Commission expressly stated that the four categories of conduct which it had identified were described for analytical purposes and that they were intertwined and partially overlapping, which precludes conduct coming within one or other of those four categories from also being classified, separately and independently, as infringements of Article 101(1) TFEU.

95 It follows from the foregoing that the complaints based on errors of classification of the conduct at issue in one or other of the four categories of conduct referred to in recitals 93, 382 and 496 of the contested decision, and their consequences for the characterisation of the conduct at issue as a ‘single and continuous infringement’, and as a ‘restriction by object’, or based on errors in the characterisation of one or other of those four categories of conduct as a ‘restriction by object’, are ineffective and must therefore be rejected.

96 However, the arguments put forward by UniCredit, Nomura and Portigon against specific discussions will be taken into consideration subsequently in order to determine whether the Commission was entitled, without making any error, to characterise the discussions at issue, taken as a whole, as a single and continuous infringement with an anticompetitive object.

97 Furthermore, it must be pointed out that, in the contested decision, the Commission criticised the banks concerned for their participation in the discussions analysed in the body of that decision and in the table annexed thereto. That table refers, for certain discussions that took place on the same day, to several timestamped excerpts.

98 However, contrary to what Portigon implicitly submits, such a presentation does not imply that the Commission intended to assess the anticompetitive nature of the discussions at issue on an intraday excerpt basis.

99 It is apparent from both the body of the contested decision and that table that the Commission’s assessment relates to all excerpts from a given day. It is also in that regard that the Commission stated, in response to a question from the Court, that the aim of specifying time slots in the contested decision was to structure the evidence and make the decision more intelligible.

100 Accordingly, when examining Portigon’s claims that the Commission erred in characterising the discussions at issue as a ‘single and continuous infringement’ and as a ‘restriction by object’, the Court will examine the discussions relied on against that bank on a daily basis.

C. The applicants’ claims for annulment

101 As a preliminary point, it should be recalled that a decision adopted on the basis of Article 101 TFEU with respect to several undertakings, although drafted and published in the form of a single decision, must be seen as a set of individual decisions finding that each of the addressees is guilty of the infringement or infringements of which they are accused and imposing on them, where appropriate, a fine (judgment of 16 September 2013, Galp Energía España and Others v Commission, T‑462/07, not published, EU:T:2013:459, paragraph 90).

102 It follows that, by bringing an action for the annulment of such a decision, each addressee thereof may bring an action before the EU judicature only in relation to those aspects of the decision which concern that addressee, whereas aspects concerning other addressees cannot, in principle, form part of the matter to be tried by the EU judicature (see, to that effect, judgment of 15 July 2015, Emesa-Trefilería and Industrias Galycas v Commission, T‑406/10, EU:T:2015:499, paragraph 117).

103 However, that case-law does not deprive all the addressees of such a decision of the possibility of challenging, in their respective actions, all of the facts on which the Commission relied in order to conclude that the conduct at issue had to be characterised as a ‘single and continuous infringement’ or as a ‘restriction by object’, notwithstanding the fact that the addressee challenging that conduct did not take part in it.

104 Consequently, UBS is not entitled to seek the annulment of the contested decision in its entirety. At most, it may seek the annulment of those parts of the operative part of that decision which concern it.

105 The application for annulment of the contested decision made by UBS must therefore be understood as referring solely to the sixth indent of Article 1 and the fourth indent of Article 2 of that decision.

106 In support of their claims for annulment of the contested decision in so far as it concerns them, the applicants put forward various pleas, which overlap to a large extent, and which it is appropriate to examine in the following order:

– the pleas alleging infringement of the rights of the defence and an inadequate statement of reasons relating to the identification of the conduct at issue (the first limb of Nomura’s fifth plea; BofA’s third plea; Portigon’s first plea);

– the pleas alleging errors on the part of the Commission for having held the banks concerned liable for the acts of their employees (the first part of UniCredit’s third plea; the second limb of Nomura’s fourth plea; the second limb of Portigon’s fifth plea);

– the pleas alleging errors in the characterisation of the conduct at issue as a ‘single and continuous infringement’ and as regards the attributability of that infringement to the banks concerned for a certain period (UniCredit’s second plea, the second part of its third plea, part of its fifth plea and its sixth plea; part of Nomura’s first plea, its second and third pleas, the first and third limbs of its fourth plea, the third argument of the first limb and the second, third and fourth limbs of its fifth plea; BofA’s first plea; Portigon’s fourth plea and part of the first limb of its fifth plea);

– the pleas alleging errors in the characterisation of that single and continuous infringement as a ‘restriction by object’, possibly accompanied by a failure to state reasons (UniCredit’s first and third to fifth pleas; Nomura’s first plea and part of its second plea; part of the first limb of Portigon’s fifth plea);

– the pleas based on errors relating to the existence of a legitimate interest on the part of the Commission in making a finding of infringement against the banks which were not fined, possibly accompanied by an infringement of the rights of the defence and an inadequate statement of reasons in that regard (Natixis’s first to third pleas; BofA’s second plea; Portigon’s sixth plea);

– the pleas alleging errors in the amount of the fines imposed on them, as regards the determination of the basic amount of those fines and the individual adjustments made to that basic amount (UBS’s first to fifth pleas; UniCredit’s seventh to tenth pleas; Nomura’s sixth to tenth pleas);

– the plea alleging a failure to observe the principles of unity of the legal order and of consistency (Portigon’s second plea);

– the plea alleging an unlawful failure by the Commission to exercise its discretion (Portigon’s third plea);

– the plea alleging that the Commission exceeded its powers, reversed the burden of proof and breached the principle of the presumption of innocence as a consequence of the wording of Article 3 of the contested decision (Natixis’s fourth plea).

1. The objections alleging infringements of the rights of the defence and an inadequate statement of reasons relating to the identification or presentation of the conduct at issue

107 As a preliminary point, it should be noted that Nomura, in the first branche of its fifth plea, BofA, in its third plea, and Portigon, in the first branche of its first plea, object to the presentation of the conduct relied on against them as set out in the Statement of Objections and in the contested decision, claiming infringements of their rights of defence and of the Commission’s obligation to state reasons.

108 While those two objections are raised jointly, they are separate, the first alleging, in essence, deficiencies in the Statement of Objections which deprived those banks of the opportunity to exercise their rights of defence effectively during the administrative procedure which led to the contested decision, and the second alleging a failure to state reasons specific to that contested decision, which deprived the banks concerned of the opportunity to ascertain the reasons for it and the EU judicature of the opportunity to exercise its power of review.

109 Those two objections must therefore be examined in turn.

(a) The objections alleging infringements of Nomura’s, BofA’s and Portigon’s rights of defence

(1) BofA’s objection alleging infringement of its rights of defence owing to the substantial difference between the evidence relied on against it in the Statement of Objections and in the contested decision

110 In the first limb of its third plea, BofA claims that the Commission ‘altered the intrinsic nature’ of the single and continuous infringement alleged against it between the Statement of Objections and the contested decision.

111 In the Statement of Objections, the Commission initially alleged that BofA had participated in the entire single and continuous infringement at issue, relying, principally, on discussions which had taken place in the DBAC chatroom and, to a lesser extent, on those which had taken place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom. To that end, in recitals 596 and 618 to 622 of the Statement of Objections, the Commission relied on the fact that that bank was aware of, or could have reasonably foreseen, the conduct of the other banks participating in the infringement at issue put into effect in the DBAC chatroom or through instant messaging.

112 Then, in the contested decision, it alleged only that BofA had participated in the single and continuous infringement at issue ‘with respect to the CODS & CHIPS chatroom’, after finding, in recital 441 of that decision, that ‘it cannot be concluded with sufficient certainty that [BofA] was aware or ought reasonably to have been aware and was willing to take the risk of the existence and functioning of the DBAC chatroom or other anticompetitive communications’.

113 In order to enable BofA to defend itself, the Commission should have indicated in the Statement of Objections that it intended to find that that bank had participated in the infringement at issue solely by virtue of its participation in the discussions that had taken place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom, that ‘all the various types of conduct that constituted the cartel took place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom during the period of BofA’s involvement’ or that the discussions which took place in the DBAC and CODS & CHIPS chatrooms pursued the same objective.

114 Consequently, the Statement of Objections addressed to BofA did not enable it to understand that the Commission could, in the contested decision, find that it had participated in a single and continuous infringement with respect only to the CODS & CHIPS chatroom, which, moreover, it indicated during the administrative procedure after having been informed on 16 March 2021 that the Commission was no longer claiming that it was aware of the DBAC chatroom.

115 That infringement of its rights of defence is confirmed by the fact that numerous discussions which took place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom and which were referenced only in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections were added to the body of the contested decision, which in itself also constitutes a second infringement of BofA’s rights of defence. Those additions show that, at the stage of the contested decision, the Commission relied on a materially different presentation and analysis of the evidence in order to conclude that the two chatrooms in question pursued the same objective.

116 In that regard, it should be recalled that observance of the rights of the defence requires, in particular, that the statement of objections which the Commission sends to an undertaking on which it envisages imposing a penalty for an infringement of the competition rules contain the essential elements used against it, such as the facts, the characterisation of those facts and the evidence on which the Commission relies, so that the undertaking may submit its arguments effectively in the administrative procedure brought against it (see judgment of 16 June 2022, Sony Corporation and Sony Electronics v Commission, C‑697/19 P, EU:C:2022:478, paragraph 70 and the case-law cited).

117 However, the essential elements on which the Commission relies in the statement of objections may be set out summarily and the final decision is not necessarily required to replicate the statement of objections, since that statement is a preparatory document containing assessments of fact and of law which are purely provisional in nature. Thus, it is permissible to supplement the statement of objections in the light of the parties’ response, whose arguments show that they have actually been able to exercise their rights of defence. The Commission may also, in the light of the administrative procedure, revise or supplement its arguments of fact or law in support of its objections. Consequently, until a final decision has been adopted, the Commission may, in view, in particular, of the written or oral observations of the parties, abandon some or even all of the objections initially made against them and thus alter its position in their favour or decide to add new complaints, provided that it affords the undertakings concerned the opportunity of making known their views in that respect (see judgment of 18 June 2013, ICF v Commission, T‑406/08, EU:T:2013:322, paragraph 118 and the case-law cited).

118 In the present case, the Commission found, in the first indent of Article 1 of the contested decision, that BofA had participated in the infringement at issue, with the material scope of that participation being narrower than that envisaged in the Statement of Objections.

119 The Commission criticised BofA for having participated in that infringement no longer in respect of all the anticompetitive discussions which had taken place in the DBAC and CODS & CHIPS chatrooms and by means of bilateral communications, but only as regards those discussions which had taken place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom.

120 That narrowing of the scope of BofA’s participation in the infringement at issue found in the Statement of Objections compared with that found in the contested decision is favourable to BofA and cannot therefore, in principle, harm its interests (see, to that effect, judgment of 18 June 2013, ICF v Commission, T‑406/08, EU:T:2013:322, paragraph 123 and the case-law cited).

121 However, in the light of BofA’s arguments, it is necessary to examine whether that narrowing of the material scope of BofA’s participation in the infringement at issue led the Commission to find, in the contested decision, that it had participated in an infringement so different from that set out in the Statement of Objections that it should be treated as a new objection on which that bank should have been able to submit its written and oral observations, in order to ensure that its rights of defence were observed.

122 In the first place, it must be pointed out that, in its reply, BofA acknowledges that, by the contested decision, the Commission did not criticise it for participating in ‘a standalone single and continuous infringement based solely on [the discussions that took place in the] CODS & CHIPS [chatroom]’.

123 In the second place, BofA does not dispute that, subject to a marginal reduction in its total duration, the material, geographic and temporal scope of the infringement alleged against all of the banks to which the contested decision was addressed does not differ between the Statement of Objections and that decision.

124 Accordingly, only the material scope of BofA’s participation in the infringement at issue was altered between the Statement of Objections and the contested decision, and not the scope of the infringement as such.

125 In the third place, it must be noted that, both in the Statement of Objections and in the contested decision, the Commission alleged that BofA had participated in a single and continuous infringement.

126 First, as the Commission recalled, in essence, in recital 590 of the Statement of Objections, it is settled case-law that an undertaking which has participated in a single and continuous infringement through its own conduct, which meets the definition of ‘agreements’ or ‘concerted practices’ for the purposes of Article 101(1) TFEU and was intended to help bring about the infringement as a whole, may also be liable in respect of the conduct of other undertakings in the context of the same infringement throughout the period of its participation in the infringement. That is the position where it is shown that the undertaking intended, through its own conduct, to contribute to the common objectives pursued by all the participants and that it was aware of the offending conduct planned or put into effect by other undertakings in pursuit of the same objectives or that it could reasonably have foreseen it and was prepared to take the risk (see judgment of 6 December 2012, Commission v Verhuizingen Coppens, C‑441/11 P, EU:C:2012:778, paragraph 42 and the case-law cited; see also, to that effect, judgment of 16 June 2011, Team Relocations and Others v Commission, T‑204/08 and T‑212/08, EU:T:2011:286, paragraphs 36 and 37).

127 Second, as is apparent, first of all, from the Statement of Objections, the Commission indicated that the ‘representative’ discussions referred to in the body of that statement and all of those referenced in Annex 1 thereto had the same general characteristics, set out in recitals 111 to 120 of the Statement of Objections, irrespective of the chatroom in which the banks concerned had participated.

128 Next, the table annexed to the Statement of Objections listing all of the discussions in question showed that the Commission considered that BofA’s trader had participated in discussions that could be classed in all four categories of conduct identified in recital 529 of the Statement of Objections, as the Commission indeed noted in recital 614 of that statement.

129 Lastly, in recitals 114 and 615 of the Statement of Objections, the Commission expressly stated that the traders of the banks concerned had participated ‘in some or all of these activities’ by taking part in the discussions that took place in the CODS & CHIPS ‘and/or’ DBAC chatrooms.

130 It follows from the three preceding paragraphs that the single and continuous infringement set out in the Statement of Objections and alleged against, inter alia, BofA, was essentially linked to the subject matter and content of the discussions between the banks concerned, viewed independently of the chatroom in which the banks concerned participated.

131 Thus, contrary to BofA’s contention, the fact that the banks concerned were connected to the two chatrooms was not a decisive factor in the single and continuous infringement detailed by the Commission in the Statement of Objections.

132 That finding is confirmed by footnote 129 to the Statement of Objections, from which it is clear that, at that stage of the procedure, the Commission considered that only a limited proportion of the 3 583 messages exchanged in the chatrooms in question were anticompetitive.

133 Consequently, by finding in the contested decision that BofA had participated in the infringement at issue only ‘with respect to the CODS & CHIPS chatroom’, the Commission merely reduced the scope of the objections addressed to that bank and set out in the Statement of Objections.

134 Therefore, in the contested decision, the Commission did not find that BofA had participated in an infringement so different from that set out in the Statement of Objections that it should be treated as a new objection on which BofA should have been able to submit its written and oral observations in order to ensure that its rights of defence were observed.

135 For the same reasons, BofA cannot meaningfully claim that, following the Statement of Objections, it was not able to foresee that its participation limited solely to the discussions which took place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom might lead the Commission to find that it participated in the alleged single and continuous infringement.

136 For the same reasons again, BofA’s line of argument set out in paragraph 113 above must also be rejected.

137 Those conclusions are not called into question by BofA’s line of argument, referred to in paragraph 115 above, that numerous discussions which took place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom and which were referenced only in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections were added to the body of the contested decision, which, according to BofA, demonstrates the ‘material’ difference in the Commission’s analysis between the Statement of Objections and the contested decision.

138 As pointed out in paragraph 117 above, the Statement of Objections is a preparatory document, which the Commission may supplement in the final decision, provided that its addressee was able to reasonably deduce from it the conclusions which the Commission intended to draw.

139 In addition, Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections formed an integral part of that statement, as the Commission indeed expressly indicated in recital 125, which reads, first, ‘the contacts mentioned in the chronological overview of this Statement of Objections are non-exhaustive but considered representative for the description of the pattern of conduct in the relevant period’ and, second, ‘a full overview of the selected contacts between competitors that support the preliminary conclusions set out in this Statement of Objections can be found in Annex 1’.

140 BofA does not indicate to what extent the explanations relating to each of the discussions contained in the body of the contested decision and referenced solely in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections differ materially from the preliminary analysis deriving from a combined reading of sections 4 and 5 of the Statement of Objections, the table annexed thereto setting out the categories within which each of the timestamped discussions allegedly came and, where necessary, the Letter of Facts.

141 In the light of the foregoing, the first limb of BofA’s third plea must be rejected as unfounded.

142 Moreover, in so far as BofA relies on an additional infringement of its rights of defence owing to the use in the contested decision of discussions referenced only in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections, as stated in paragraph 115 above, that objection is also raised in the second limb of its third plea and, on that basis, will therefore be examined in paragraphs 143 to 189 below.

(2) The objections raised by Nomura, BofA and Portigon alleging infringement of their rights of defence due to the presentation of the conduct at issue in the Statement of Objections and in the Letter of Facts

143 Nomura, in the first limb of its fifth plea, BofA, in the second limb of its third plea, and Portigon, in its first plea, claim that the Commission infringed their rights of defence due to the presentation of the conduct at issue in the Statement of Objections and in the Letter of Facts.

144 In essence, first of all, that infringement is said to stem from the fact that, in the body of the Statement of Objections, the Commission detailed only a small number of discussions which it considered representative and, as to the remainder, referred to Annex 1 to that statement. BofA thus states that a very significant number of discussions which concerned that bank and were referenced only in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections – namely 29 excerpts from 18 discussions – were explained, for the first time, in the contested decision.

145 Next, that infringement of Nomura’s, BofA’s and Portigon’s rights of defence stems from the fact that, in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections, namely a table headed ‘Selection of relevant contacts’, the Commission merely used the letter ‘Y’ for each discussion to identify the category or categories to which it belonged; those categories were, moreover, insufficiently defined. Furthermore, the difficulty in understanding the forms of conduct referred to in the table in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections was exacerbated where, within a given day, several periods were referred to. By way of example, Portigon refers to the discussion of 5 November 2009 and to ‘six other contacts’. However, since those ‘six other contacts’ have not been clearly identified by Portigon, they cannot be examined by the Court.

146 Lastly, BofA argues that not only should the Commission have indicated the market and the bonds concerned, but should also have provided a detailed explanation of those discussions. Those explanations were made all the more necessary because the language used by the traders was extremely technical and those discussions could be legitimate.

147 Those omissions, taken as a whole, denied Nomura, BofA and Portigon the possibility of readily deducing the conclusions which the Commission intended to draw from all the discussions referred to in the Statement of Objections and, therefore, of effectively making their positions known. In that regard, BofA adds that, had they been able to do so, the outcome of the administrative procedure might have been different.

148 As a preliminary point, first, it should be noted that, in the first part of its fifth plea, Nomura claims, inter alia, that its rights of defence were infringed due to the way in which the Statement of Objections was presented.

149 However, that claim is supported only by paragraphs 112 to 115 of its application and will therefore be examined only in the light of the considerations referred to in those paragraphs.

150 Second, in the second part of its third plea, BofA relies not only on an infringement of its rights of defence but also, and on the same grounds, on a failure to comply with the obligation to state reasons in the Statement of Objections. Since those two objections overlap, they will be examined together.

151 In that regard, it should be noted that, in recital 112 of the Statement of Objections, the Commission stated that ‘the alleged cartel consisted of various actions and/or inactions that were interrelated and largely overlapped’ and that it ‘could potentially be achieved by means such as attempting to drive the price of an EGB bond down in the run up to an auction of further bonds (with the aim of paying less for the issue), attempting to coordinate on bidding levels and thus reduce the chances of overbidding in an auction, and exchanging information on the timing of the pricing of syndicates for new bond issues’.

152 In recitals 113 and 529 of the Statement of Objections, the Commission stated that ‘these interrelated activities [could] be presented in different categories or stages’, namely, first, coordination and attempts to coordinate trading strategies, second, coordination to facilitate the alignment of bidding strategies, third, coordination and attempts to coordinate the level of overbidding, and, fourth, other exchange of forward-looking sensitive information.

153 The Commission indicated the types of conduct that each of those categories covered.

154 As regards, in particular, Category 4, it stated that that category included ‘the sharing of other sensitive information that actually or potentially allowed the [banks concerned] to directly or indirectly adjust or align their EGB trading activities and, in particular, the sharing of information on (i) individual recommendations given to a debt management office before an upcoming auction on the type, maturity or size of the EGB to be issued; (ii) prices and/or volumes of individual trades of EGB on the secondary market; (iii) strategies for specific counterparties; and (iv) the timing of pricing of syndications’.

155 In Section 4.2 of the Statement of Objections, the Commission presented more than 130 discussions in the form either of tables containing relevant and timestamped excerpts of the discussion concerned or, in a more concise manner, quotations, which are often timestamped and are identified by inverted commas and italics.

156 Moreover, in recital 81 of the Statement of Objections, the Commission stated that ‘the selection presented in Section 4.2, however, [wa]s not exhaustive, but rather constitute[d] a representative sample of the whole body of evidence on which the Commission relie[d], which [wa]s included in Annex 1’ and that ‘Section 4.2 below [wa]s complemented, therefore, by Annex 1, which identifie[d] all of the selected relevant contacts with which the Commission t[ook] issue for the purpose of th[e] … Statement of Objections’.

157 Annex 1 included a table identifying approximately 480 discussions that had taken place between all or some of the banks concerned, including the 130 discussions presented in the body of the Statement of Objections.

158 For each of those 480 discussions, Annex 1 indicated its date, the chatroom in which it had taken place, the time of the relevant ‘non-exhaustive extracts’, the banks which participated in it, its classification in one or more of the categories referred to in recital 113 of the Statement of Objections, the location of any reference to it in the body of that statement, the bank which provided the Commission with the transcript of the discussion and its/their index number in the Commission’s file.

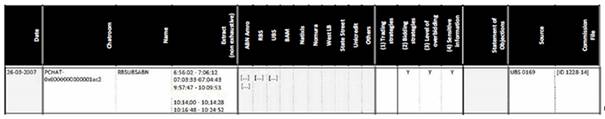

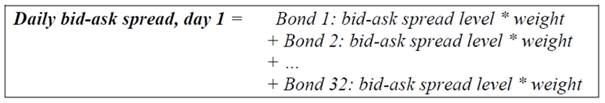

159 That presentation took the following form in English and German:

160 Furthermore, in the Letter of Facts, the Commission rectified certain material errors and, after that letter was communicated, the banks concerned were again able to access the evidence in the Commission’s file and submit their observations in writing.

161 It follows from the foregoing that, as regards the more than 130 discussions set out in the body of the Statement of Objections, a combined reading of Section 4.2 of that statement and the table in Annex 1, which identified the participants in each discussion, the excerpts referred to by the Commission and the nature of the conduct at issue by reference to the categories referred to in recital 113 of that statement, did enable the banks concerned properly to identify that evidence and the use that the Commission was likely to make of it in the contested decision.

162 As regards the approximately 350 discussions referenced only in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections, it should be borne in mind, as already stated in paragraphs 116 and 117 above, that the Statement of Objections is a preparatory document intended to enable its addressees properly to identify the conduct complained of by the Commission and the evidence available to it.

163 That information may be given summarily, provided that the Commission sets forth clearly all the essential facts upon which the Commission is relying at that stage of the procedure (judgment of 7 June 1983, Musique Diffusion française and Others v Commission, 100/80 to 103/80, EU:C:1983:158, paragraph 14).

164 In that regard, it must be noted that, in the present case, it is clear from recital 125 of the Statement of Objections that Annex 1 to that statement constitutes an integral part of it and is to be read in the light of all the recitals set out in the body of the statement.

165 It follows that, in the table in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections, the use of the letter ‘Y’ to indicate the category of conduct into which the Commission intended a discussion should come cannot be regarded as lacking clarity or precision.

166 Since the Commission had identified and detailed, in recitals 113 to 120 of the Statement of Objections, the types of anticompetitive conduct covered by each of the four categories of conduct in question by means of a general definition and examples, the banks concerned were able to understand the type of conduct to which the Commission was referring for each discussion, without the Commission having to provide further explanations as to the unlawful nature of the discussion in question.

167 In that regard, the fact that, in relation to the same discussion on the same day, the Commission was able to identify several excerpts without, however, indicating, for each of those excerpts, the category or categories of conduct to which it belonged, does not call that conclusion into question.

168 In addition to the fact that organising each excerpt into a single category was not necessarily practicable owing to the rapid succession and interweaving of messages that might have different subject matters and therefore come within different categories, the methodology used by the Commission in any event enabled the banks concerned to identify with certainty the excerpts which the Commission considered, at that stage, to be anticompetitive.

169 Moreover, as is apparent, implicitly but necessarily, from the Statement of Objections and in particular from recitals 577 and 578 thereof, the categories of conduct used by the Commission had been defined for analytical purposes and not to identify as many infringements of Article 101 TFEU as there were categories referred to in recital 113 of the Statement of Objections.

170 Therefore, even if the banks concerned themselves had to identify the category referred to by the Commission to which each excerpt from a particular discussion belonged, they remained fully informed that the Commission was likely to use that discussion to demonstrate the existence of a single and continuous infringement with an anticompetitive object comprising all of the discussions placed in those categories.

171 In that regard, in so far as concerns the discussion of 11 June 2007, objected to by BofA, Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections referred to the discussion of that day, dividing it into five excerpts, consisting, as is apparent from that annex read in conjunction with the transcript of that discussion, of approximately 1 minute and 5 messages, less than 4 minutes and 12 messages, approximately 1 minute and 5 messages, approximately 31 minutes and 21 messages and, finally, 9 seconds and 2 messages, respectively, and placing it in Categories 1, 2 and 4. Such a presentation cannot have led BofA to have been unable to identify the messages which, in the Commission’s view, were capable of being anticompetitive. That is the case, for example, with the third excerpt which, in two of its five messages, shows that RBS’s trader wrote ‘where u got mid on bono 37 vs bund?’ and that UBS’s trader replied ‘6.15’.

172 It must also be found that BofA’s objection, referred to in paragraph 144 above and based on the fact that 29 excerpts from 18 discussions were explained, for the first time, in the contested decision, and that of Portigon relating to the discussion of 5 November 2009, referred to in paragraph 145 above, cannot succeed.

173 First, two of the discussions objected to by BofA were analysed in the body of the Statement of Objections by reference to messages exchanged on the same day and included in other excerpts referred to in the table contained in Annex 1 to the Statement of Objections (discussion of 25 July 2007 detailed in recitals 144 and 145 of the Statement of Objections; discussion of 27 March 2008, detailed in recital 200 of that statement).

174 Second, the discussion of 5 November 2009 objected to by Portigon and five of the discussions objected to by BofA (discussion of 5 June 2007, consisting of four excerpts; discussions of 25 and 30 July 2007, consisting of two and three excerpts, respectively; discussion of 11 October 2007, consisting of five excerpts; discussion of 27 March 2008, which took place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom and consists of two excerpts) gave rise, at the time of the Letter of Facts, to detailed explanations, at least with regard to certain categorisations.

175 By way of example, as regards the discussion of 5 November 2009 which took place in the CODS & CHIPS chatroom, referred to in recital 277 of the contested decision and not examined in the body of the Statement of Objections, the ‘Explanations’ column in the Letter of Facts indicates that classifying that discussion in Categories 1 and 3 is justified by the fact that ‘in accordance with [recital] 532 of the [Statement of Objections], it includes an attempt to move the curve ahead of an auction (“why does it seem when we want it flatter all these […]?”’ and by the fact that, ‘in accordance with [recital] 542 of the [Statement of Objections], it also touches upon an attempt to coordinate overbidding levels (“what we thinking of overpaying?”)’.